Submitted:

09 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We propose an enhanced Wi-Fi indoor positioning system that jointly utilizes RSS and RTT measurements. This hybrid approach exploits the complementary advantages of signal strength–based and time-of-flight–based ranging to achieve robust sub-meter accuracy across diverse environments, including LOS, NLOS, and mixed conditions.

- We introduce a computationally efficient GTCN that explicitly models spatial dependencies among APs using graph convolutions with inverse-distance edge weighting, while concurrently capturing causal temporal correlations between consecutive signal scans through dilated TCNs. This unified design enhances both spatial consistency and temporal robustness while remaining suitable for real-time embedded deployment.

- We systematically investigate the impact of AP density under both LOS and NLOS conditions to assess the scalability and robustness of the proposed model. This analysis highlights the adaptability of the proposed hybrid GTCN model under both sparse and dense AP deployments.

2. Related Work

3. System Model and Proposed Methodology

3.1. Preliminaries and Problem Formulation

3.1.1. Signal Modeling and Objective

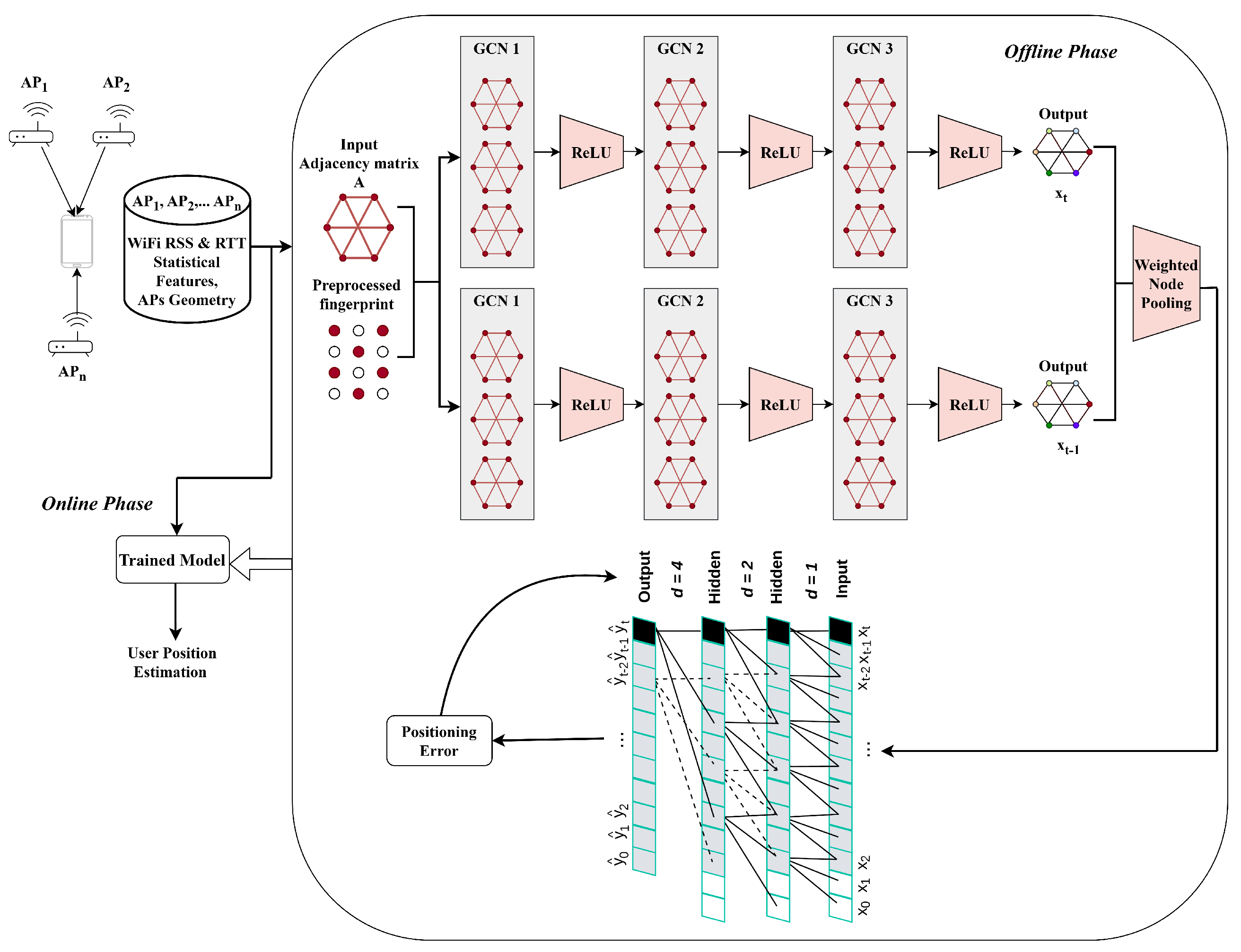

3.2. Proposed Indoor Positioning Method

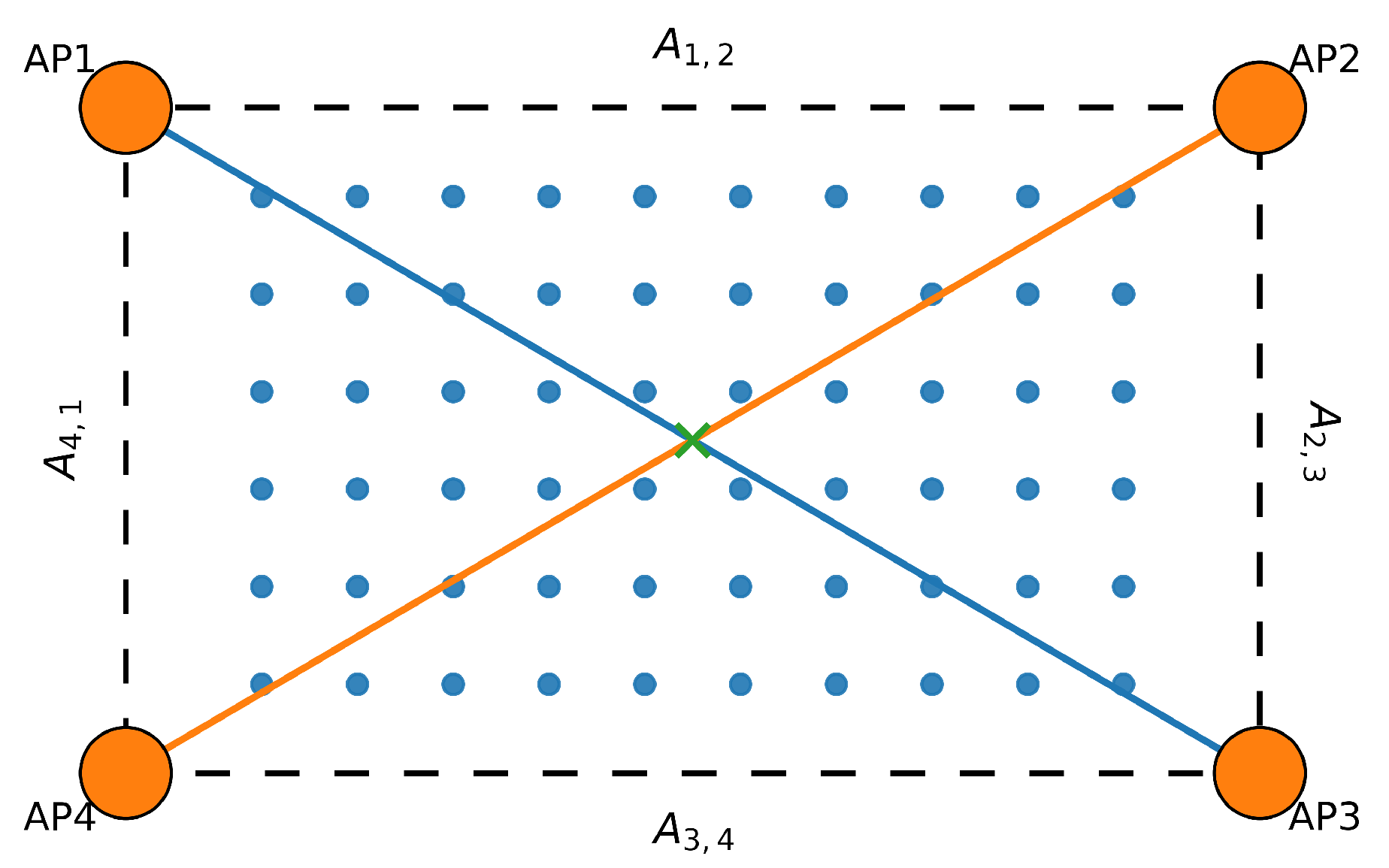

3.2.1. GCN: Spatial Correlation Modeling

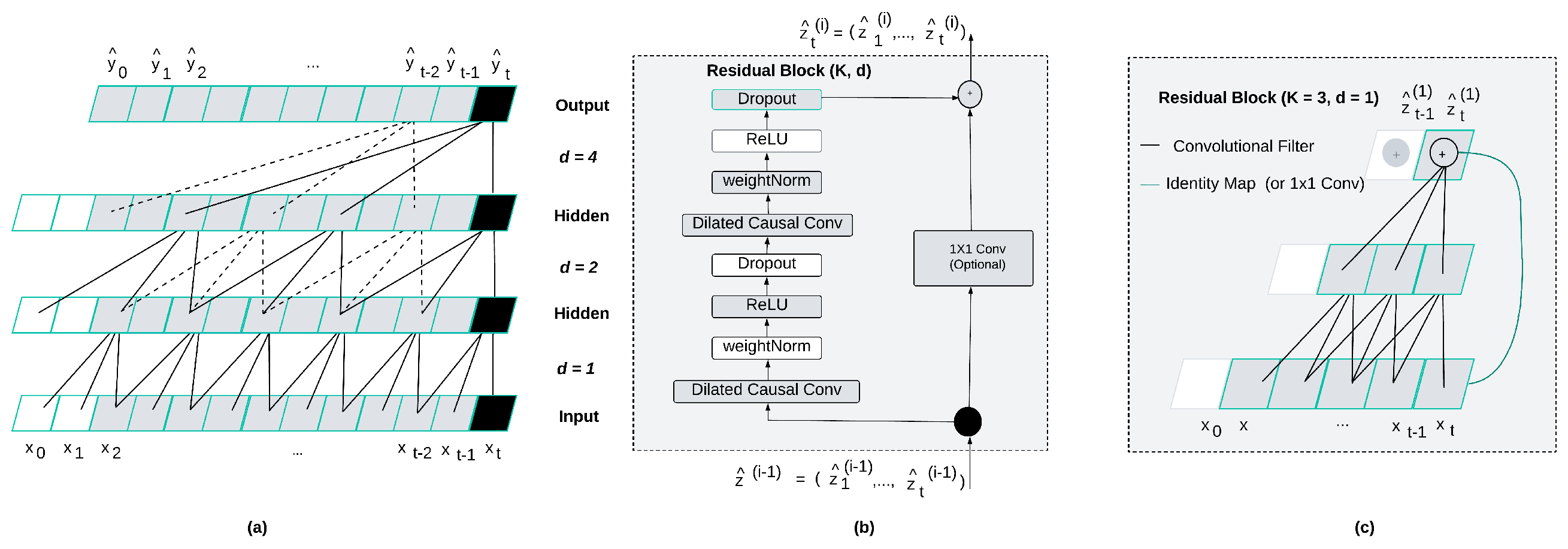

3.2.2. TCN: Causal Sequence Modeling

3.2.3. Hybrid GTCN Model

| Algorithm 1: Proposed hybrid GTCN-Based Wi-Fi Indoor Positioning Method |

|

Input: Raw Wi-Fi RSS and RTT fingerprint sequences; optional AP coordinates

Output: Estimated positions

1 Initialization: Initialize model parameters.

2 Offline Phase:

Online Phase:

|

4. Experimental Dataset and Results

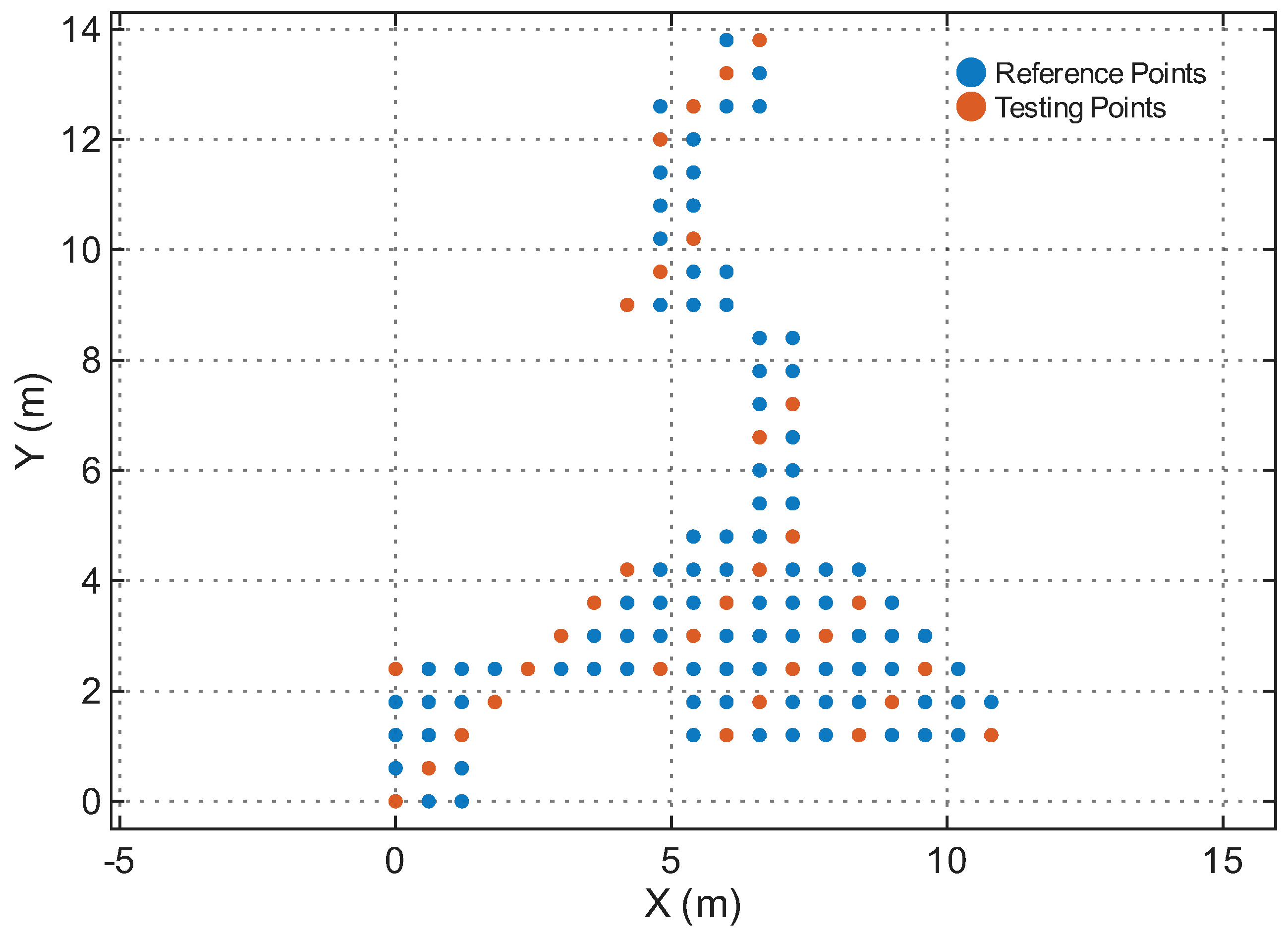

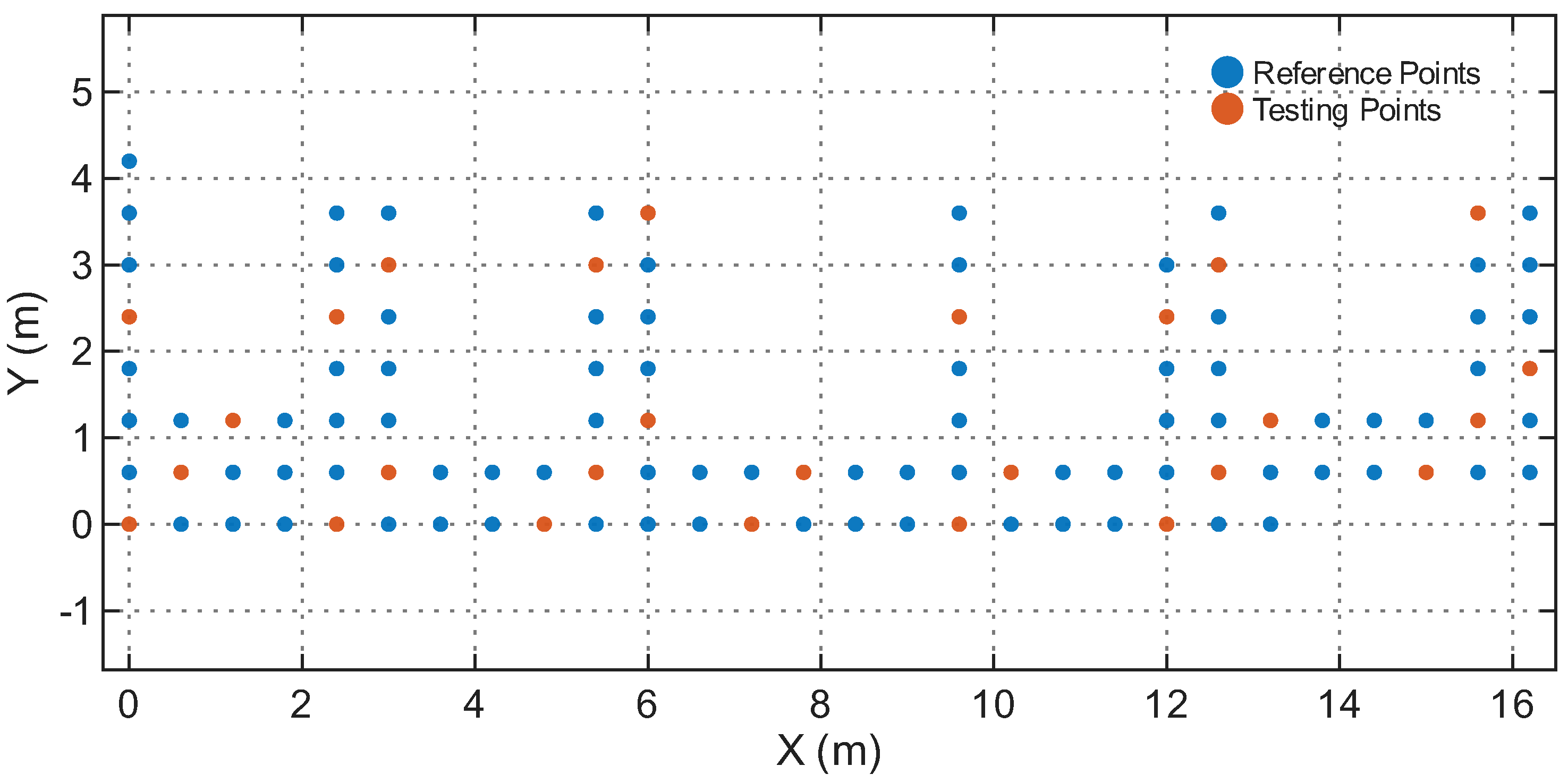

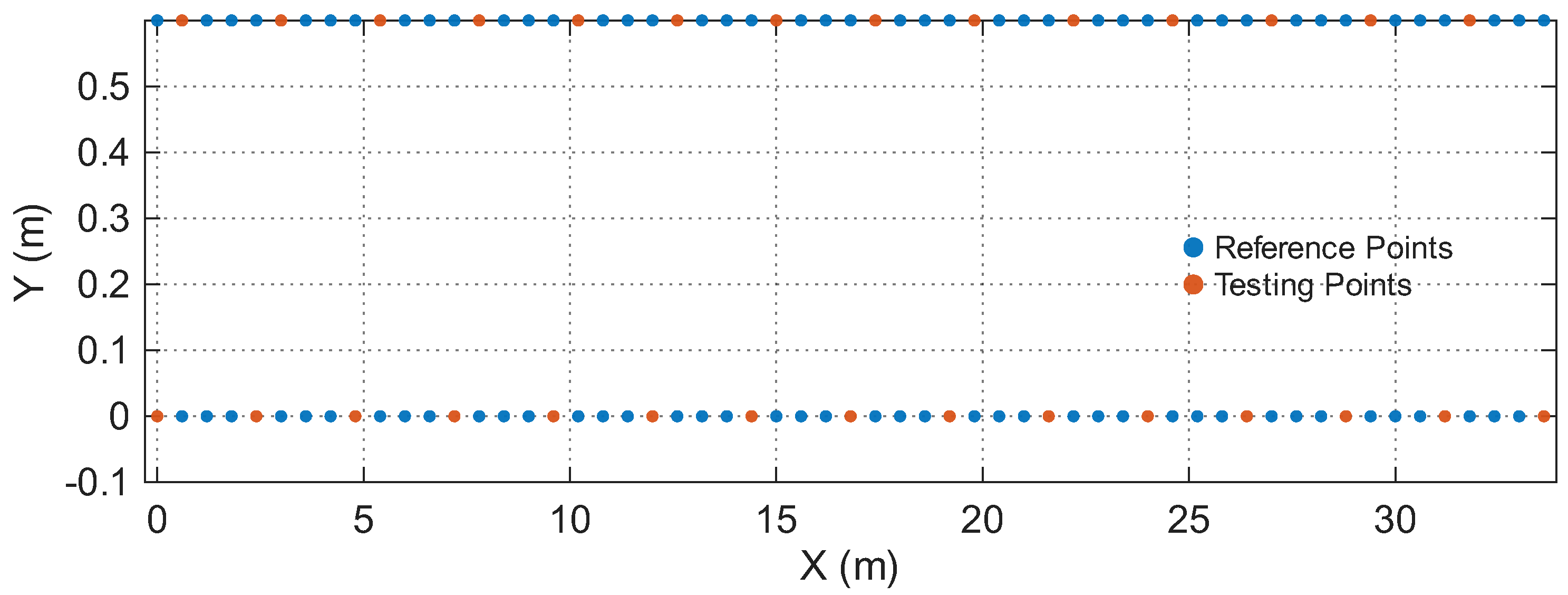

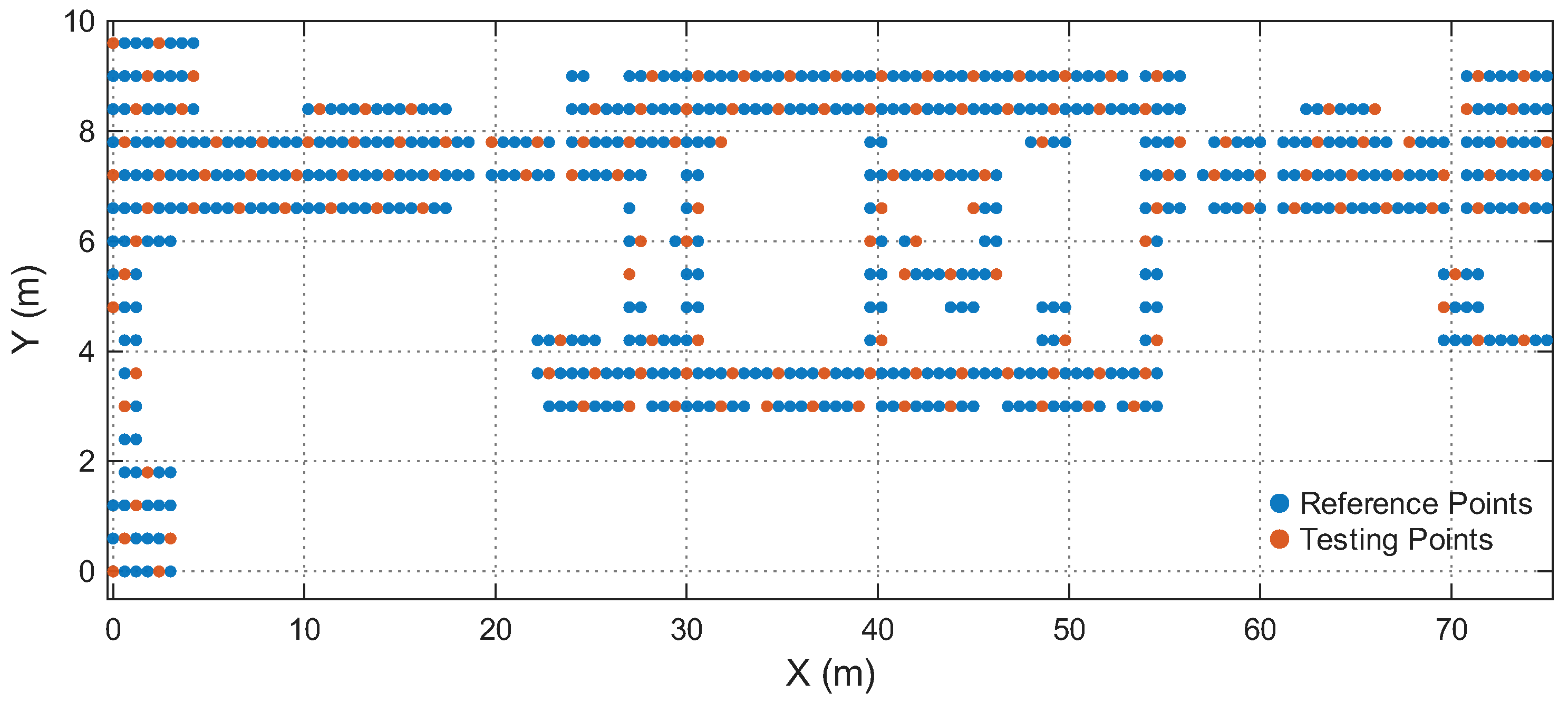

4.1. Data Collection and Testbeds

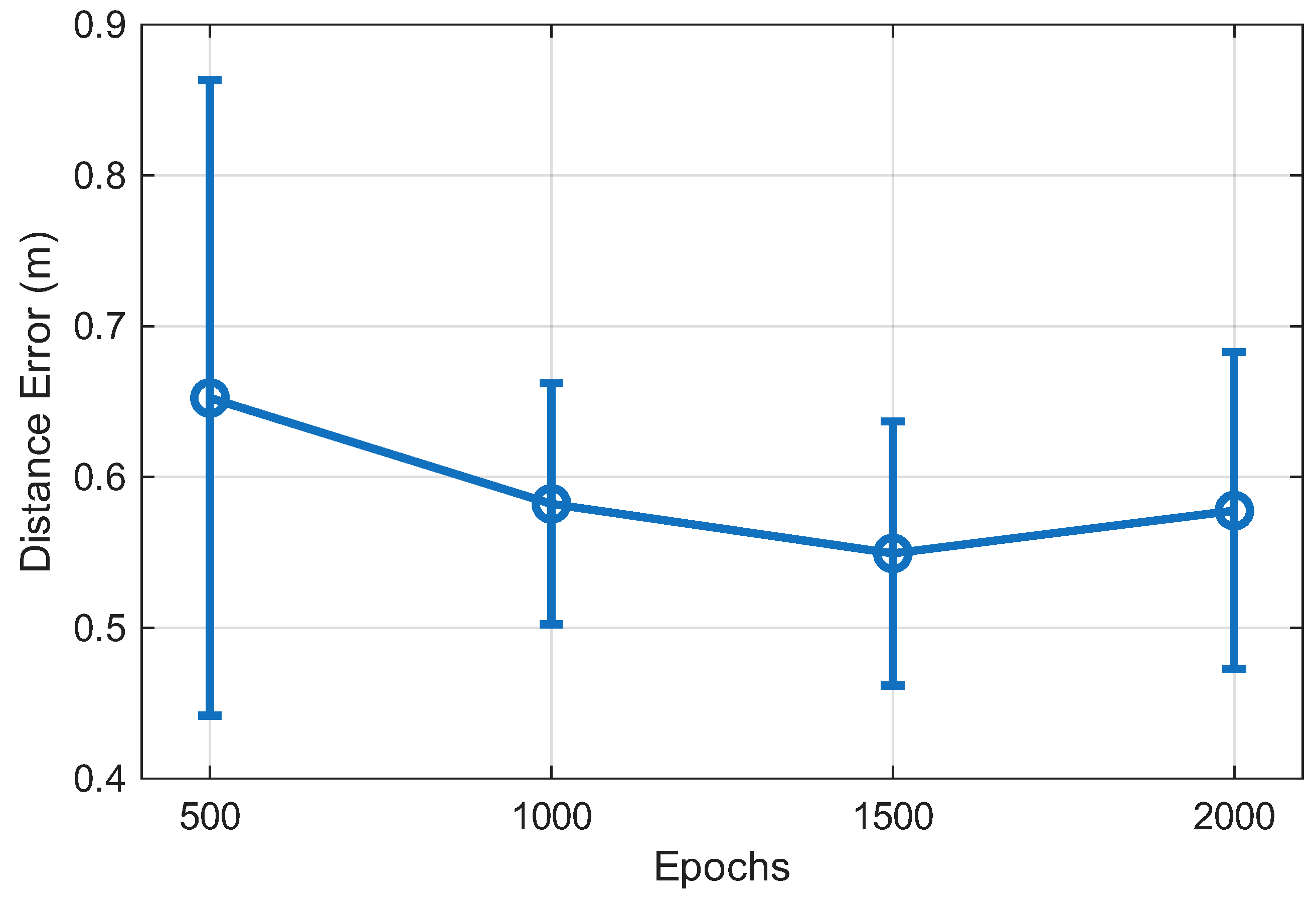

4.2. Model Parameters

4.3. Positioning Performance

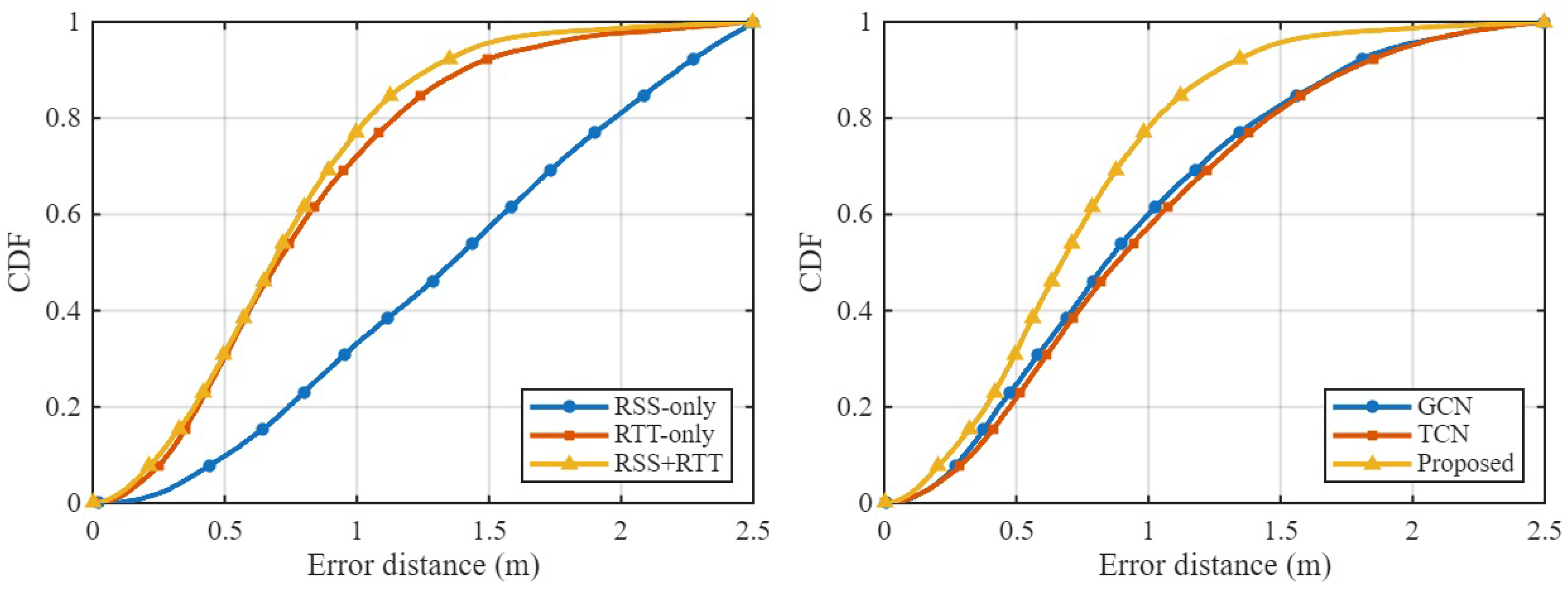

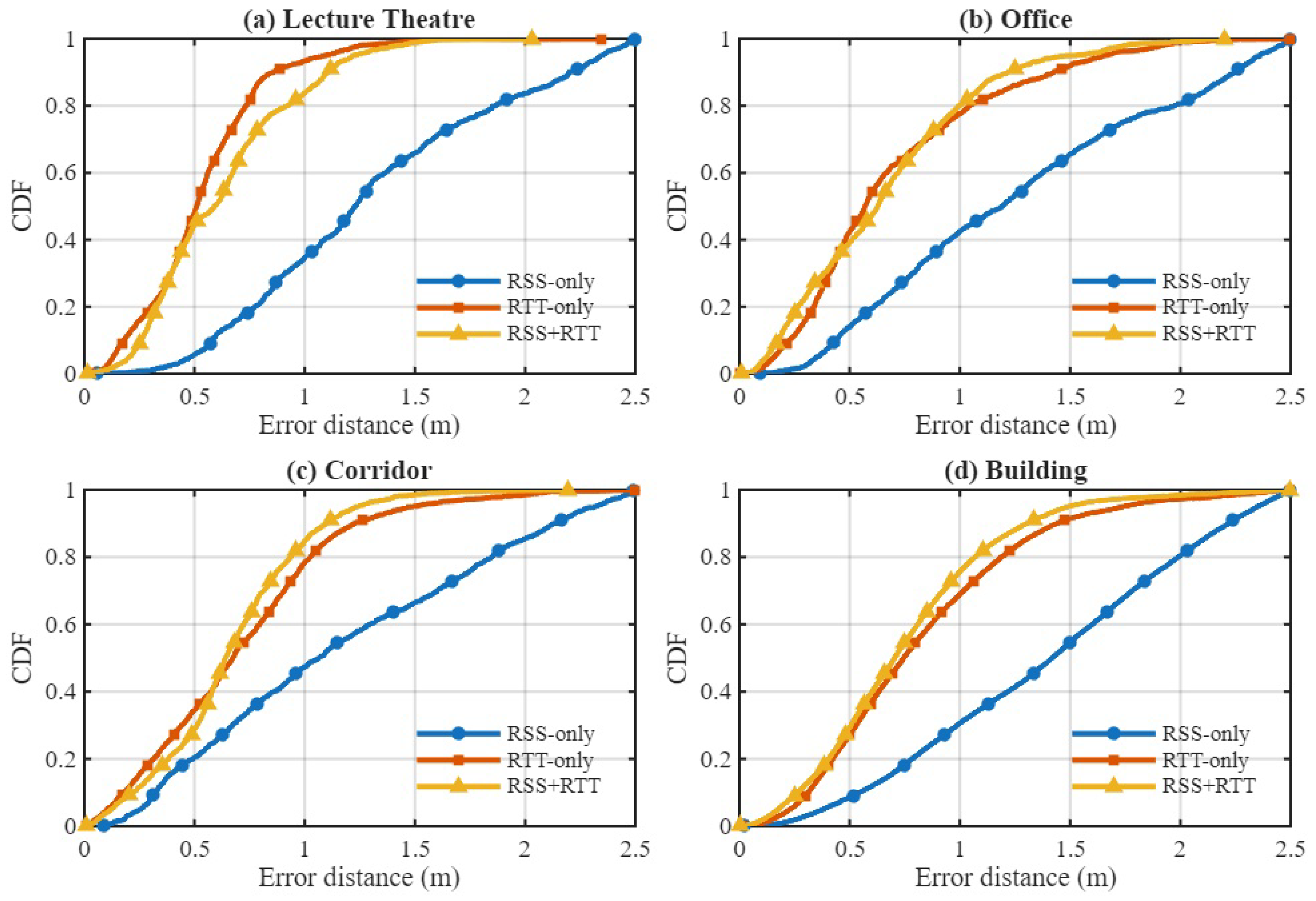

4.3.1. Comparison of RSS, RTT, and Hybrid RSS–RTT

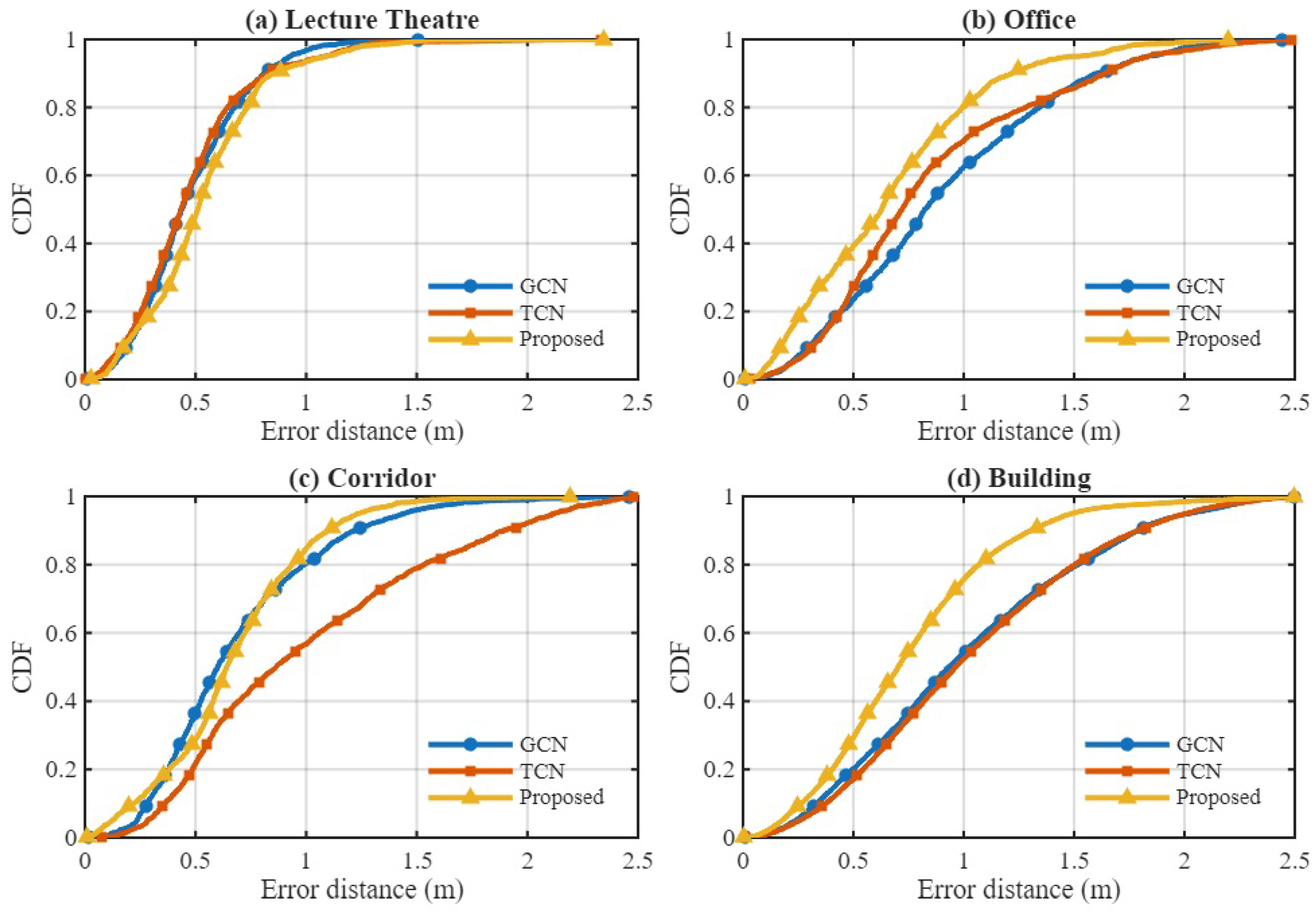

4.3.2. Comparison of GCN, TCN, and Hybrid GTCN Model

| Environment | Model | Feature Mode | RMSE (m) | Epochs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lecture Theatre | GCN | RTT | 0.426 | 1500 |

| Lecture Theatre | TCN | RTT | 0.410 | 1500 |

| Lecture Theatre | Proposed | RTT | 0.449 | 1500 |

| Office | GCN | RTT | 0.622 | 1500 |

| Office | TCN | RTT | 0.704 | 1500 |

| Office | Proposed | Both | 0.560 | 1500 |

| Corridor | GCN | RTT | 0.586 | 1500 |

| Corridor | TCN | RTT | 0.773 | 1500 |

| Corridor | Proposed | Both | 0.529 | 1500 |

| Building | GCN | RTT | 0.877 | 1500 |

| Building | TCN | RTT | 0.757 | 1500 |

| Building | Proposed | Both | 0.660 | 1500 |

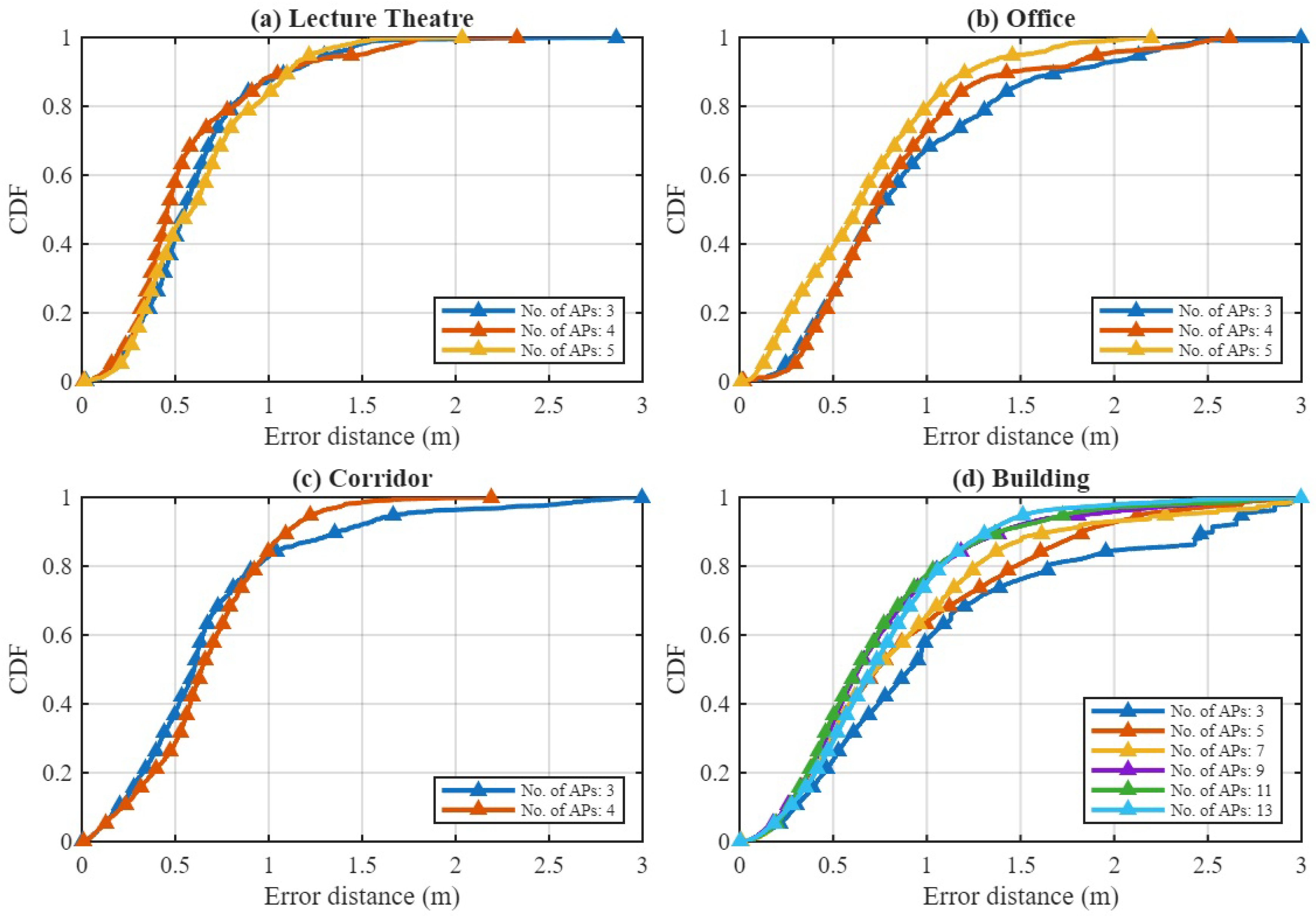

4.3.3. Impact of Number of APs

4.3.4. Model Complexity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Enge, P.K. The Global Positioning System: Signals, measurements, and performance. International Journal of Wireless Information Networks 1994, 1, 83–105. [CrossRef]

- Rusli, M.E.; Ali, M.; Jamil, N.; Din, M.M. An Improved Indoor Positioning Algorithm Based on RSSI-Trilateration Technique for Internet of Things (IOT). In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering (ICCCE), 2016, pp. 72–77. [CrossRef]

- Fedosova, I.; Pronina, O.; Piatykop, O. Exploring Wi-Fi-based Indoor Positioning Techniques for Mobile App. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Information and Telecommunication Technologies and Radio Electronics (UkrMiCo), 2021, pp. 109–114. [CrossRef]

- Tarrío, P.; Bernardos, A.M.; Casar, J.R. Weighted Least Squares Techniques for Improved Received Signal Strength Based Localization. Sensors 2011, 11, 8569–8592. [CrossRef]

- Bahl, P.; Padmanabhan, V. RADAR: an in-building RF-based user location and tracking system. In Proceedings of the Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM 2000. Conference on Computer Communications. Nineteenth Annual Joint Conference of the IEEE Computer and Communications Societies (Cat. No.00CH37064), 2000, Vol. 2, pp. 775–784 vol.2. [CrossRef]

- Numan, P.E.; Park, H.; Laoudias, C.; Horsmanheimo, S.; Kim, S. DNN-based Indoor Fingerprinting Localization with WiFi FTM. In Proceedings of the 2022 23rd IEEE International Conference on Mobile Data Management (MDM), 2022, pp. 367–371. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Park, J.; Cui, S.; Dong, J.; Rana, L.; Hwang, J. An Indoor Positioning Method Using High Probability RSSI. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS), 2024, pp. 483–488. [CrossRef]

- Si, M.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Sun, M.; Cao, H. A Wi-Fi FTM-Based Indoor Positioning Method with LOS/NLOS Identification. Applied Sciences 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Hashem, O.; Youssef, M.; Harras, K.A. WiNar: RTT-based Sub-meter Indoor Localization using Commercial Devices. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications (PerCom), 2020, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, R.; Chen, L.; Xu, S.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, H. Precise 3-D Indoor Localization Based on Wi-Fi FTM and Built-In Sensors. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 11753–11765. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Bi, J.; Xu, S.; Si, M.; Qi, H. Indoor Positioning Method Using WiFi RTT Based on LOS Identification and Range Calibration. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Si, M.; Wang, Y.; Seow, C.K.; Cao, H.; Liu, H.; Huang, L. An Adaptive Weighted Wi-Fi FTM-Based Positioning Method in an NLOS Environment. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 472–480. [CrossRef]

- Cypriani, M.; Lassabe, F.; Canalda, P.; Spies, F. Open Wireless Positioning System: A Wi-Fi-Based Indoor Positioning System. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 70th Vehicular Technology Conference Fall, 2009, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Darabi, H.; Banerjee, P.; Liu, J. Survey of Wireless Indoor Positioning Techniques and Systems. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2007, 37, 1067–1080. [CrossRef]

- Zafari, F.; Gkelias, A.; Leung, K.K. A Survey of Indoor Localization Systems and Technologies. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2019, 21, 2568–2599. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.C.; Wang, C.H.; Hsieh, C.H.; Chiou, Y.S.; Cheng, T.P. Cost-Effective Fitting Model for Indoor Positioning Systems Based on Bluetooth Low Energy. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Khyam, M.O.; Noor-A-Rahim, M.; Li, X.; Ritz, C.; Guan, Y.L.; Ge, S.S. Design of Chirp Waveforms for Multiple-Access Ultrasonic Indoor Positioning. IEEE Sensors Journal 2018, 18, 6375–6390. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, L.T.; Chen, M.; Zhao, S.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Y. Real-Time Locating Systems Using Active RFID for Internet of Things. IEEE Systems Journal 2016, 10, 1226–1235. [CrossRef]

- Werner, M.; Kessel, M.; Marouane, C. Indoor positioning using smartphone camera. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation, 2011, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Uradzinski, M.; Guo, H.; Liu, X.; Yu, M. Advanced Indoor Positioning Using Zigbee Wireless Technology. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2017, 97, 6509–6518. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Park, J. A Novel Fingerprint Localization Algorithm Based on Modified Channel State Information Using Kalman Filter. Journal of Electrical Engineering and Technology 2020, 15, 1811–1819. Publisher Copyright: © 2020, The Korean Institute of Electrical Engineers., . [CrossRef]

- Brunato, M.; Battiti, R. Statistical learning theory for location fingerprinting in wireless LANs. Computer Networks 2005, 47, 825–845. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Dong, J.B.; Hwang, J.G.; Rana, L.; Park, J.G. Indoor Positioning Method Based on CGAN using Modified Fingerprint DB with IEEE 802.11 RSSI Measurements. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Symposium of the Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences (KICS), Jeju, South Korea, June 2024; pp. 131–132.

- Cui, S.; Dong, J.; Hwang, J.G.; Rana, L.; Li, J.; Park, J.G. An enhanced WiFi indoor positioning method based on SNGAN. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2023), 2023, pp. 1684–1692.

- Li, J.; Dong, J.; Hwang, J.G.; Rana, L.; Ryu, H.; Park, J.G. Deep Learning-Based Wi-Fi Signal Fingerprinting Indoor Positioning Technology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 37th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2024), Baltimore, Maryland, USA, September 2024; pp. 1354–1362. [CrossRef]

- Maranò, S.; Gifford, W.M.; Wymeersch, H.; Win, M.Z. NLOS identification and mitigation for localization based on UWB experimental data. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 2010, 28, 1026–1035. [CrossRef]

- Rana, L.; Dong, J.; Cui, S.; Li, J.; Hwang, J.; Park, J. Indoor Positioning using DNN and RF Method Fingerprinting-based on Calibrated Wi-Fi RTT. In Proceedings of the 2023 13th International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), 2023, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chan, S.H.G. Wi-Fi Fingerprint-Based Indoor Positioning: Recent Advances and Comparisons. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2016, 18, 466–490. [CrossRef]

- IEEE Standard for Information Technology–Telecommunications and Information Exchange between Systems Local and Metropolitan Area Networks–Specific Requirements Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications Amendment 2: Enhanced Throughput for Operation in License-exempt Bands above 45 GHz. IEEE Std 802.11ay-2021 (Amendment to IEEE Std 802.11-2020 as amendment by IEEE Std 802.11ax-2021) 2021, pp. 1–768. [CrossRef]

- Segev, J.; Berger, C. Next Generation Wi-Fi Positioning: An Overview of IEEE 802.11az. https://www.computer.org/csdl/video-library/video/1UXPYs1JCrS, 2025. Accessed on April 24, 2025.

- Rana, L.; Park, J.G. An Enhanced Indoor Positioning Method Based on RTT and RSS Measurements Under LOS/NLOS Environment. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 31417–31430. [CrossRef]

- IEEE Standard for Information Technology–Telecommunications and Information Exchange between Systems - Local and Metropolitan Area Networks–Specific Requirements - Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications. IEEE Std 802.11-2020 (Revision of IEEE Std 802.11-2016) 2021, pp. 1–4379. [CrossRef]

- Shoudha, S.N.; Helwa, S.; Van Marter, J.P.; Torlak, M.; Al-Dhahir, N. WiFi 5GHz CSI-Based Single-AP Localization With Centimeter-Level Median Error. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 112470–112482. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.G.; Dong, J.; Rana, L.; Li, J.L.; Park, J.G. An Enhanced Access Points Placement Method for Indoor Positioning Using PPO. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Symposium of the Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences (KICS), Jeju, South Korea, June 2024.

- Liu, X.; Wu, R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, T. Graph Temporal Convolutional Network-Based WiFi Indoor Localization Using Fine-Grained CSI Fingerprint. IEEE Sensors Journal 2025, 25, 9019–9033. [CrossRef]

- Jurdi, R.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Loong Ng, B.; Dawar, N.; Zhang, C.; Han, J.K.H. WhereArtThou: A WiFi-RTT-Based Indoor Positioning System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 41084–41101. [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Rana, L.; Li, J.; Hwang, J.; Park, J. Indoor Positioning Using Wi-Fi RTT Based on Stacked Ensemble Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS), 2024, pp. 1021–1026. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Bi, J.; Xu, S.; Si, M.; Qi, H. Indoor Positioning Method Using WiFi RTT Based on LOS Identification and Range Calibration. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Bi, J.; Xu, S.; Qi, H.; Si, M.; Yao, G. WiFi RTT Indoor Positioning Method Based on Gaussian Process Regression for Harsh Environments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 215777–215786. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Bi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, G.; Feng, Y.; Si, M. LOS compensation and trusted NLOS recognition assisted WiFi RTT indoor positioning algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 243, 122867. [CrossRef]

- Park, K.M.; Lee, B.h.; Lee, E.; Kim, S.C.; Choi, J. GPS-Aided Automatic Site Survey Method for WiFi RTT-Based Positioning. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 13120–13129. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Chen, R.; Ye, F.; Peng, X.; Liu, Z.; Pan, Y. Indoor Smartphone Localization: A Hybrid WiFi RTT-RSS Ranging Approach. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 176767–176781. [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Rana, L.; Cui, S.; Li, J.; Hwang, J.; Park, J. Investigation on Indoor Positioning by Improved RTT-RSS Fusion Ranging Method. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Electronics and Communication Engineering (ICECE), 2023, pp. 49–53. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Díaz, N.; Zola, E.; Martin-Escalona, I. Assessing the Impact of Coupling RTT and RSSI Measurements in Fingerprinting Wi-Fi Indoor Positioning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Int’l ACM Conference on Modeling Analysis and Simulation of Wireless and Mobile Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2023; MSWiM ’23, p. 19–26. [CrossRef]

- Rizk, H.; Elmogy, A.; Yamaguchi, H. A Robust and Accurate Indoor Localization Using Learning-Based Fusion of Wi-Fi RTT and RSSI. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Nguyen, K.A.; Luo, Z. A Wi-Fi RSS-RTT Indoor Positioning Model Based on Dynamic Model Switching Algorithm. IEEE Journal of Indoor and Seamless Positioning and Navigation 2024, 2, 151–165. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Arslan, T.; Yang, Y. Real-Time NLOS/LOS Identification for Smartphone-Based Indoor Positioning Systems Using WiFi RTT and RSS. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 5199–5209. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Chen, R.; Ye, F.; Liu, Z.; Xu, S.; Huang, L.; Li, Z.; Qian, L. A Robust Integration Platform of Wi-Fi RTT, RSS Signal, and MEMS-IMU for Locating Commercial Smartphone Indoors. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 16322–16331. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Chen, R.; Niu, X.; Yan, K.; Xu, S.; Chen, L. Factor Graph Framework for Smartphone Indoor Localization: Integrating Data-Driven PDR and Wi-Fi RTT/RSS Ranging. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 12346–12354. [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Ko, S.W.; Kim, S. Toward Cooperative Localization With Implicit Connectivity: Graph Neural Network Approach. IEEE Wireless Communications Letters 2025, 14, 3184–3188. [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, G.; Li, Z. Smartphone-Based WiFi RTT/RSS/PDR/Map Indoor Positioning System Using Particle Filter. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2025, 74, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Yu, S.M.; Kim, S.L.; Ko, S.W. WiFi Positioning with Mobility-Induced Graphs. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring), 2024, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Jin, D.; Lin, Z.; Yin, F. Graph Neural Network for Large-Scale Network Localization. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021 - 2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2021, pp. 5250–5254. [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Meyer, F. Neural Enhanced Belief Propagation for Cooperative Localization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Statistical Signal Processing Workshop (SSP), 2021, pp. 326–330. [CrossRef]

- Bilge, A.; Ergen, E.; Soner, B.; Çöleri, S. Scalable Wi-Fi RSS-Based Indoor Localization via Automatic Vision-Assisted Calibration. 09 2025, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Al-qaness, M.; Dahou, A.; Trouba, N.; Elsayed Abd Elaziz, M.; Helmi, A. TCN-Inception: Temporal Convolutional Network and Inception modules for sensor-based Human Activity Recognition. Future Generation Computer Systems 2024. [CrossRef]

- Khor, C.; Ahmad, N. BLE-based Indoor Localization with Temporal Convolutional Network. Journal of Engineering Research 2025. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, T.; Yu, J.; Ding, X.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, Y. A Lightweight Mobile Temporal Convolution Network for Multi-Location Human Activity Recognition based on Wi-Fi. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC Workshops), 2021, pp. 143–148. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Hu, F.; Li, Y. Wi-ATCN: Attentional Temporal Convolutional Network for Human Action Prediction Using WiFi Channel State Information. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2022, 16, 804–816. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Liu, Y.T.; Chen, Y.W.; Shih, T.K. WiFi-TCN: Temporal Convolution for Human Interaction Recognition Based on WiFi Signal. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 126970–126982. [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.J. Robust Estimation of a Location Parameter. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1964, 35, 73–101. [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. arXiv:1803.01271 2018.

- Zhang, H.; Hu, B.; Xu, S.; Chen, B.; Li, M.; Jiang, B. Feature Fusion Using Stacked Denoising Auto-Encoder and GBDT for Wi-Fi Fingerprint-Based Indoor Positioning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 114741–114751. [CrossRef]

- JunLin, G.; Xin, Z.; HuaDeng, W.; Lan, Y. WiFi fingerprint positioning method based on fusion of autoencoder and stacking mode. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Culture-oriented Science & Technology (ICCST), 2020, pp. 356–361. [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Chowdhury, C.; Kundu, M.; Ghosh, D.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Novel weighted ensemble classifier for smartphone based indoor localization. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 164, 113758. [CrossRef]

| Environment | Area (m2) | LOS Type | RPs/TPs (Train/Test) | Samples (Train/Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lecture Theatre | LOS | 88 / 32 | 5280 / 1920 | |

| Office | Mixed | 81 / 27 | 4860 / 1620 | |

| Corridor | NLOS | 85 / 29 | 5100 / 1740 | |

| Building Floor | Mixed | 483 / 159 | 57960 / 19080 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Learning rate | |

| Batch size | 64 |

| Training epochs | 1500 |

| GCN layers | 3 |

| TCN blocks (causal) | 3 |

| Convolution kernel size | 3 |

| Dilation rates | (1, 2, 4, 8) |

| Hidden dimension | 64 |

| Dropout rate | 0.05 |

| Weight decay | |

| Huber loss parameter | 1.0 |

| Loss weights | (1.0, 0.5) |

| Method | Lecture Theatre | Office | Corridor | Building |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JMT-SDAE [63] | 0.716 | 0.857 | 0.705 | 1.032 |

| RS-stacking [64] | 0.724 | 0.824 | 0.672 | 0.967 |

| NWEC [65] | 0.663 | 0.781 | 0.599 | 0.965 |

| RSS–RTT Fingerprinting [46] | 0.612 | 0.729 | 0.612 | 0.989 |

| RTT Fingerprinting [46] | 0.559 | 0.718 | 0.704 | 0.988 |

| RSS Fingerprinting [46] | 2.356 | 1.423 | 1.315 | 1.730 |

| Trilateration [46] | 1.176 | 1.073 | 412.257* | 7.503 |

| Dynamic Model [46] | 0.570 | 0.698 | 0.569 | 0.950 |

| Proposed (RSS-only) | 2.170 | 1.203 | 1.230 | 1.579 |

| Proposed (RTT-only) | 0.449 | 0.649 | 0.663 | 0.731 |

| Proposed (Both) | 0.501 | 0.560 | 0.529 | 0.660 |

| # APs | RSS-only | RTT-only | RSS+RTT |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2.337 | 1.929 | 1.364 |

| 4 | 2.542 | 0.436 | 0.480 |

| 5 | 2.170 | 0.449 | 0.501 |

| # APs | RSS-only | RTT-only | RSS+RTT |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1.612 | 0.701 | 0.829 |

| 4 | 1.417 | 0.713 | 0.687 |

| 5 | 1.203 | 0.649 | 0.560 |

| # APs | RSS-only | RTT-only | RSS+RTT |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1.749 | 0.553 | 0.631 |

| 4 | 1.230 | 0.663 | 0.529 |

| # APs | RSS-only | RTT-only | RSS+RTT |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 9.693 | 9.687 | 9.716 |

| 5 | 3.082 | 2.393 | 2.376 |

| 7 | 2.258 | 1.644 | 1.586 |

| 9 | 1.689 | 0.951 | 0.803 |

| 11 | 1.538 | 0.825 | 0.725 |

| 13 | 1.579 | 0.731 | 0.660 |

| Environment | Model | Feature mode | #Params | FLOPs (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building | GCN | RSS+RTT | 21,102 | 53.18 |

| Building | TCN | RTT-only | 81,006 | 26.67 |

| Building | Proposed GTCN | RSS+RTT | 93,934 | 67.01 |

| Corridor | GCN | RTT-only | 19,221 | 7.72 |

| Corridor | TCN | RTT-only | 80,853 | 11.58 |

| Corridor | Proposed GTCN | RSS+RTT | 93,781 | 17.78 |

| Lecture Theatre | GCN | RTT-only | 19,230 | 9.52 |

| Lecture Theatre | TCN | RTT-only | 80,862 | 11.83 |

| Lecture Theatre | Proposed GTCN | RTT-only | 90,910 | 17.86 |

| Office | GCN | RTT-only | 19,230 | 9.52 |

| Office | TCN | RTT-only | 80,862 | 11.83 |

| Office | Proposed GTCN | RSS+RTT | 93,790 | 19.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).