3. Discussion

The history of partial knee arthroplasty begins long before the consolidation of the modern design of unicompartmental prostheses. As early as the beginning of the 20th century, the desire to relieve joint pain without resorting to arthrodesis led pioneering surgeons to experiment with interpositional solutions. Among the first materials used were biological tissues, such as fascia lata, synovial bursae, or joint capsule, and later, artificial elements like glass, Bakelite, and acrylic were tested.

However, it was not until the emergence of biocompatible metal alloys—particularly vitallium (a cobalt-chromium alloy)—that a decisive step was taken toward the development of structured and durable implants. This material, initially used in dentistry, offered superior wear resistance and acceptable biological tolerance, which sparked the interest of the early developers of permanent joint prostheses.

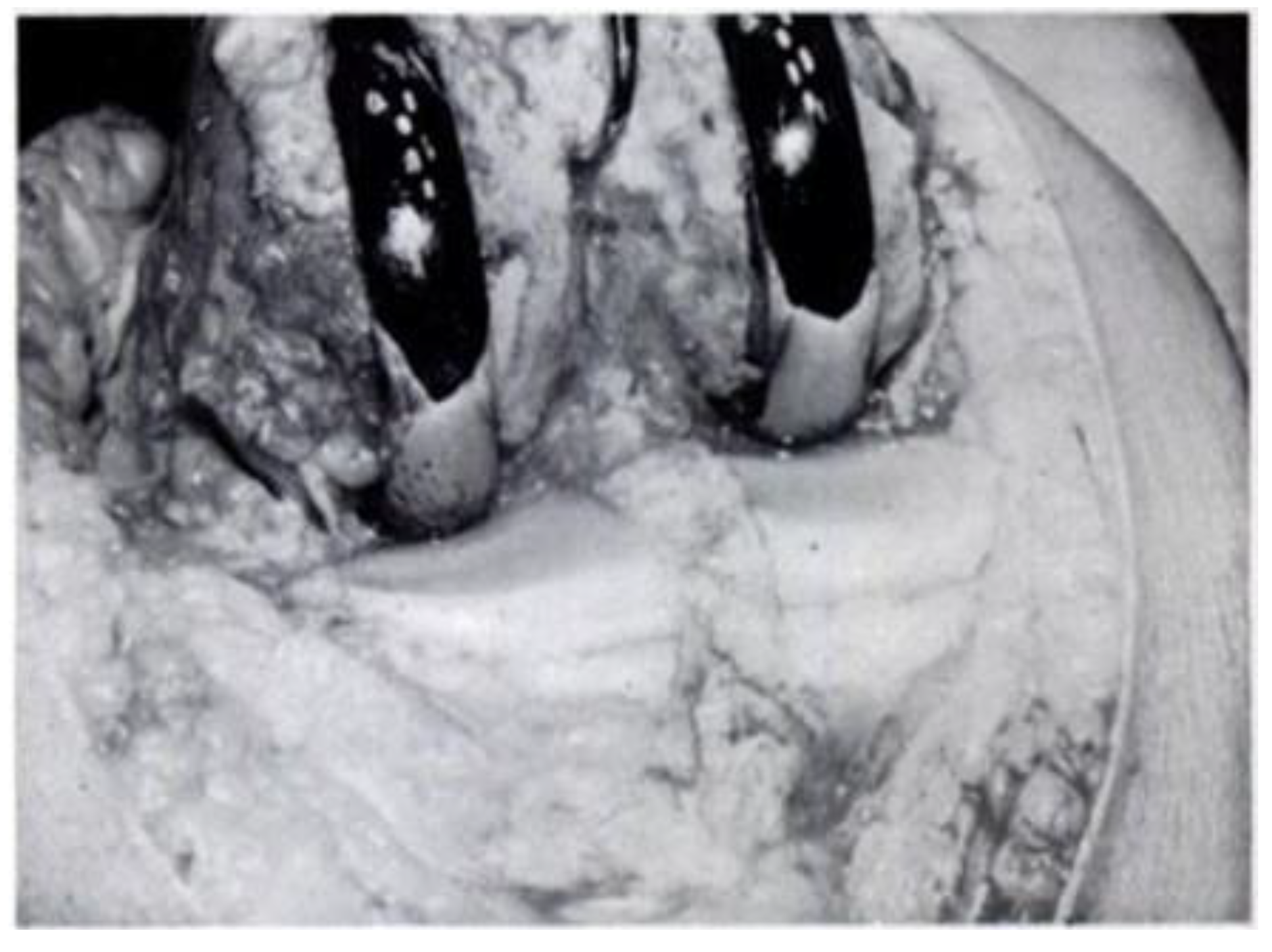

Partial knee joint replacement seemed to start in the 1940s with the contributions of Prof. Willis T. Campbell, a well-known American orthopaedic surgeon from Memphis, Tennessee. Prof. Campbell developed a metallic knee implant in an attempt to replicate the excellent early outcomes obtained by Smith-Petersen with his metallic hip implants (15). Inspired by the work done by Smith-Petersen, who used Vitallium for his hip implants, Prof. Campbell developed a Vitallium interposition knee implant that was fixed to the distal femur in an attempt to resurface the damaged cartilage of this area (

Figure 3). Unfortunately, the early results obtained by Prof. Campbell with his interposition Vitallium arthroplasty were very disappointing (15).

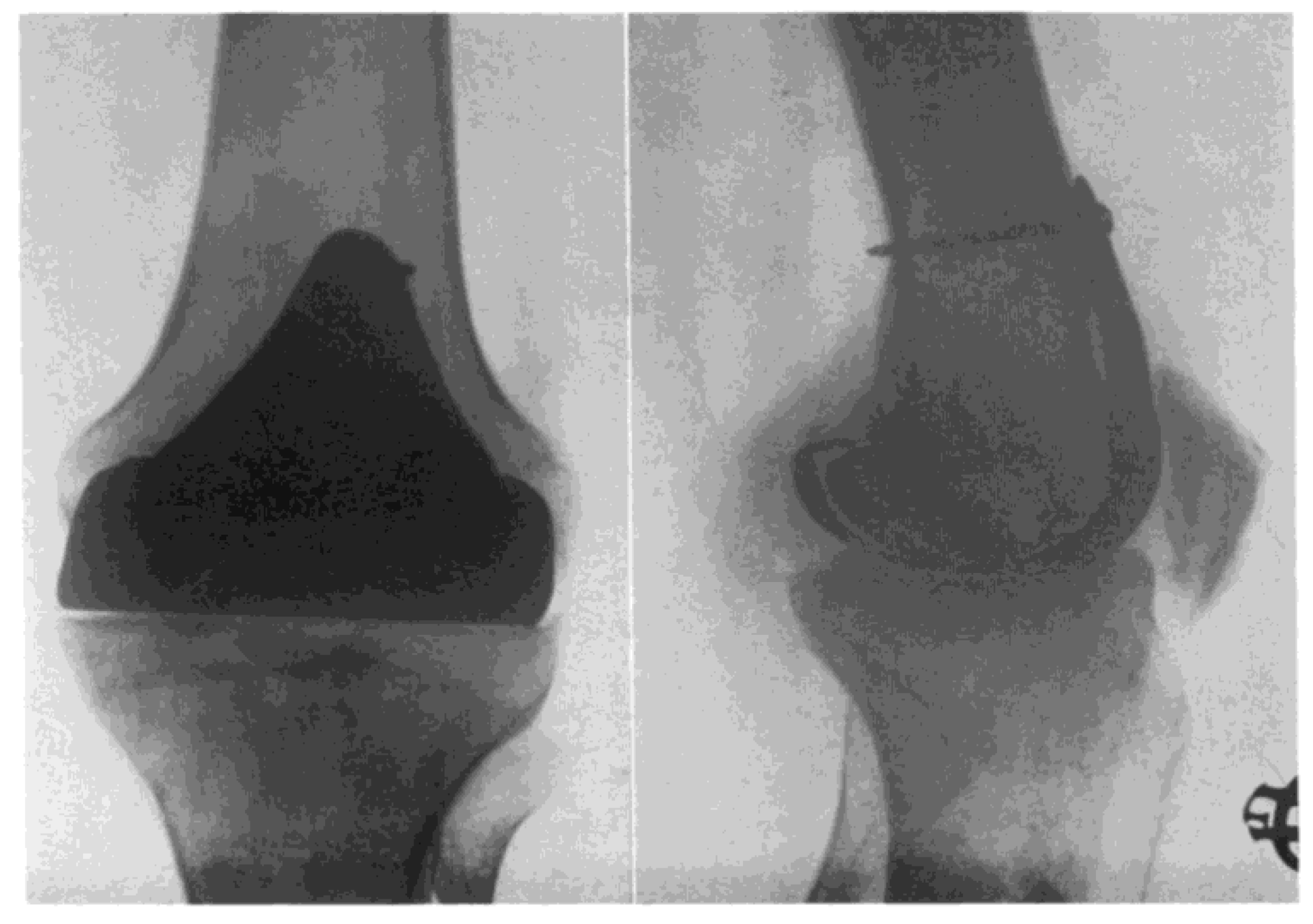

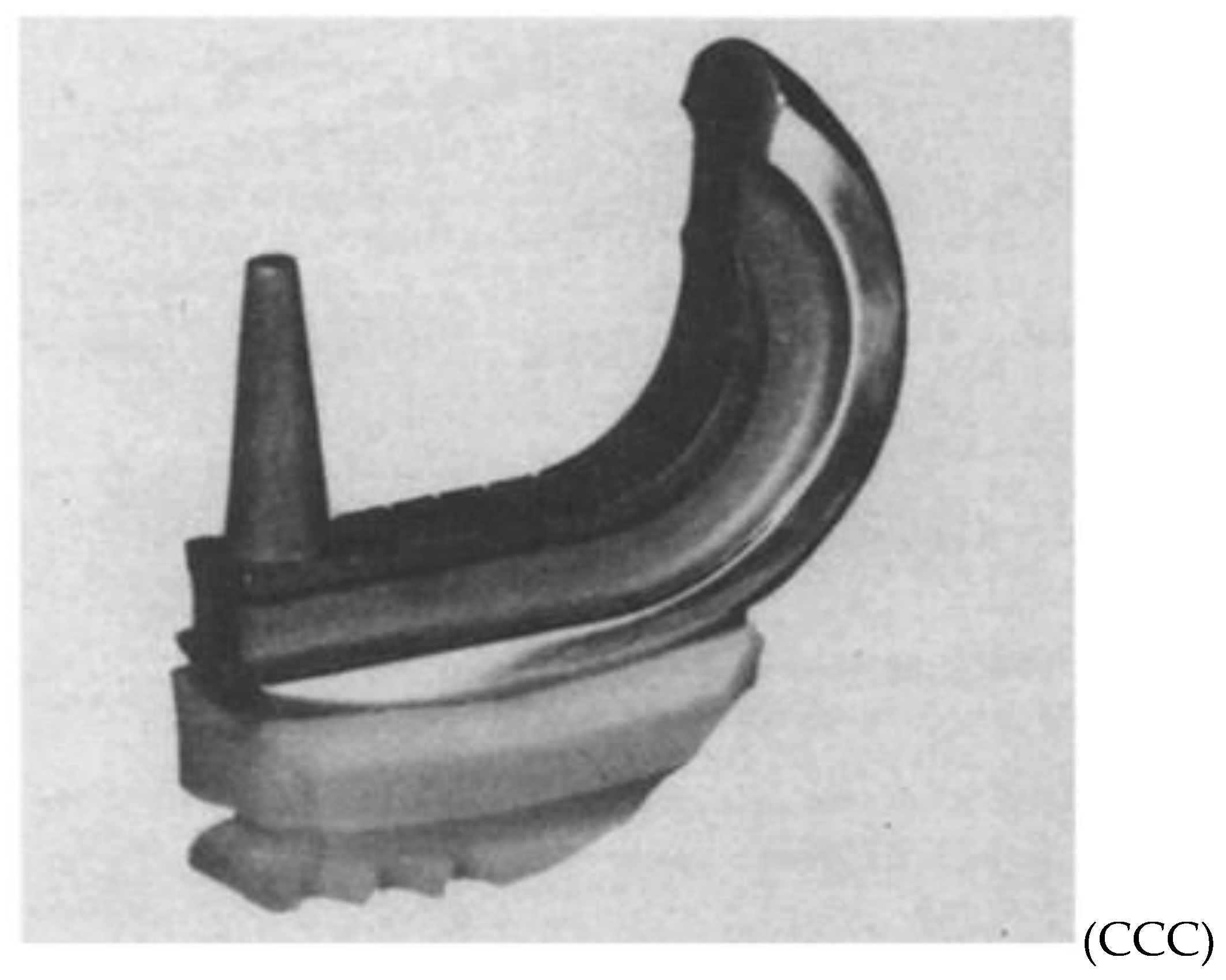

Duncan Clark McKeever, another American orthopaedic surgeon from Valley Falls, Kansas, could be credited as the one who developed the very first metallic tibial plateau unicompartmental replacement in 1952 when he introduced his Vitallium tibial plateau replacement (16) (

Figure 4). Although Duncan McKeever’s early results were promising, he could not continue his work as he tragically died in a car accident soon after operating on his 40th patient (16).

In 1954, D. L. McIntosh from Toronto, Canada, developed his own unicompartmental tibial plateau replacement which resembled the one used by Duncan McKeever (17). However, McIntosh was not inspired by him but by the work done by Dr. Sven Kiar and Dr. Kund Jansen from Copenhagen, Denmark. The Scandinavian surgeons had previously developed an acrylic replacement of the entire upper end of the tibia that was available for use in McIntosh’s institution. In 1954, during a knee intervention, McIntosh cut this acrylic prosthesis into two pieces and used one half to perform a medial unicompartmental knee interposition arthroplasty (17). The relatively good outcome obtained with this technique pushed McIntosh into the search for better materials for his partial interposition arthroplasty, which ended up with the development of his own Vitallium unicompartmental tibial plateau replacement (17) (

Figure 5).

Around the same period, many orthopaedic surgeons like Platt, De Palma, and Townley developed their own tibial plateau interposition implants. Unfortunately, all these early metallic interposition models showed suboptimal functionality, and the mid- to long-term results were not very encouraging (18,19).

Despite the limited clinical survival of these designs, the contributions from this stage were fundamental. On one hand, they established the first concepts of partial joint replacement based on the principle of preserving functional native structures; on the other hand, they paved the way for future generations of designers, who would revisit these ideas with improved indication criteria, planning tools, and greater surgical precision.

Thus, the "visionaries" of the 1940s and 1950s marked the beginning of a path that, although initially plagued by difficulties and modest clinical outcomes, laid the foundation upon which the modern partial knee prosthesis would be built.

At the beginning of the 1960s, joint reconstruction was undergoing a true conceptual revolution. The failures of metallic interposition implants in previous decades had generated some scepticism but had also provided valuable lessons on biomechanics, joint stability, and prosthetic fixation. At the same time, the advances led by Sir John Charnley in total hip arthroplasty—based on his principle of "low friction cemented arthroplasty"—established a new paradigm for the design of durable and functional prostheses, influencing a new generation of orthopaedic surgeons in Europe and North America.

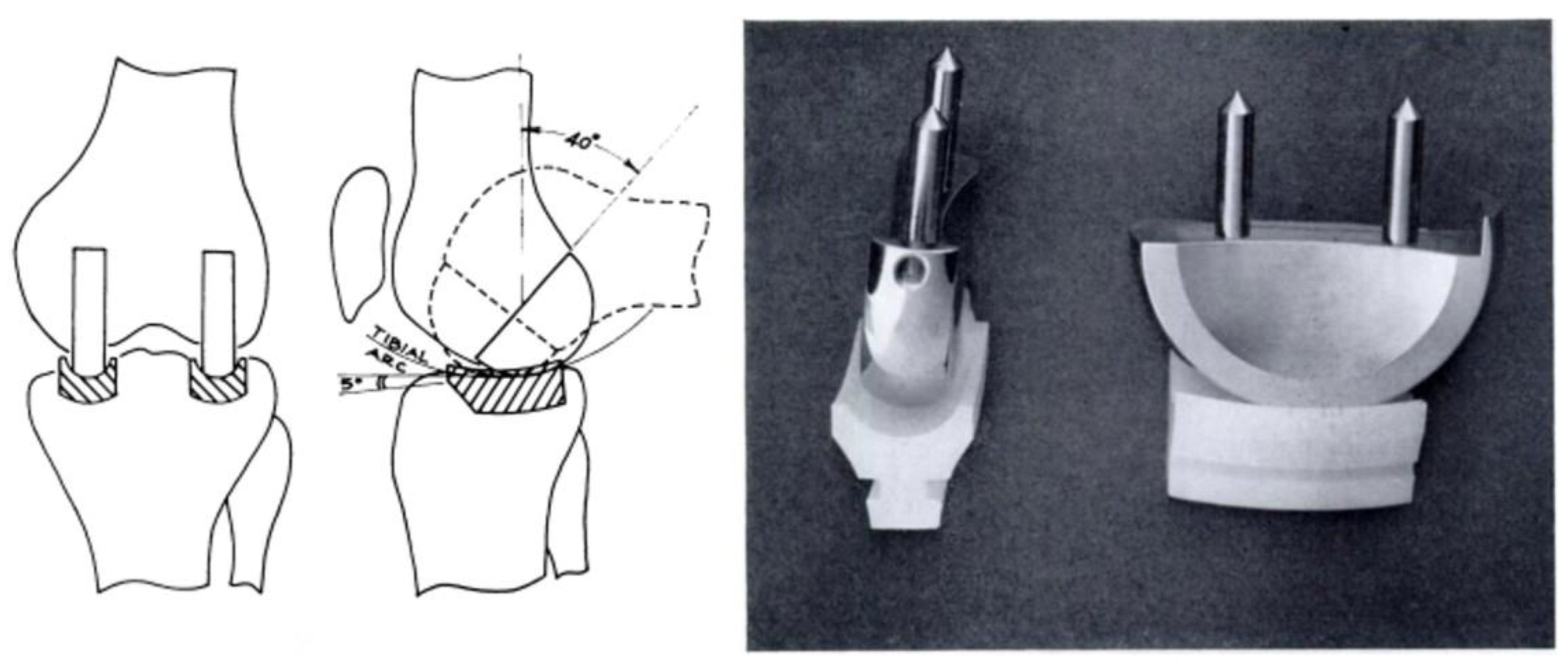

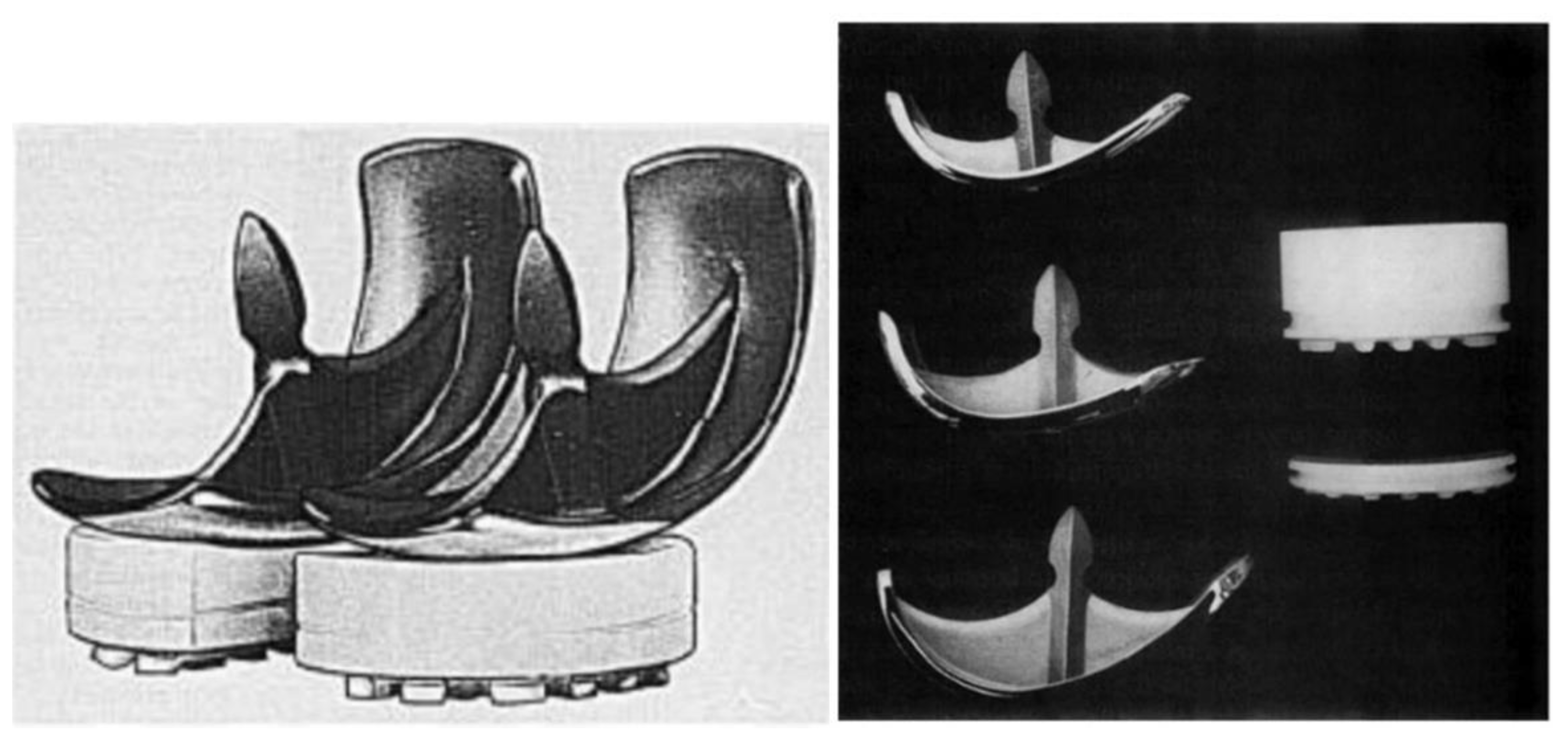

It was not until 1967 that a young surgeon from Manitoba, Canada, called Frank H. Gunston, who was on a travelling fellowship at the Wrightington Hospital, Lancashire, England, to learn from Sir John Charnley, developed the very first "cemented low-friction metal-on-plastic" knee replacement system in the world (20) (

Figure 6). Although Sir John Charnley did not collaborate directly in this knee design, Frank Gunston was inspired by the principles of the "cemented low-friction hip" developed by Charnley.

It is important to highlight that before becoming a medical doctor, Frank Gunston qualified as an electrical engineer and worked in this field for a few years. It was expected, then, that his academic background and deep knowledge of biomechanics influenced him in the development of this first knee implant (21). Frank Gunston named his invention "The Polycentric Knee Arthroplasty," which consisted of two metallic semicircular runners inserted into slots of the femoral condyles, articulated with two polyethylene partially constrained tracks cemented into slots in the tibial plateaus—a very innovative concept for the time (20) (

Figure 6).

Although the early outcomes of his implant were not bad in terms of pain relief, Gunston's attempts to guide the knee in its movements with the use of a semi-constrained tibial plateau implant resulted in suboptimal functionality and a high rate of complications. It is also important to highlight that all the early designs of condylar replacements were developed to treat both bicompartmental and unicompartmental diseases.

In any case, Gunston was a true pioneer and could have patented his low-friction knee system but selflessly chose to make it available to everyone interested, including other European and American orthopaedic surgeons. He laid the foundation and opened the door for the development of more modern unicompartmental knee replacement systems (21).

This brings us to Dr. E. Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. H.W. Buchholz—often referred to as the “German Charnley.” Dr. Engelbrecht was a German orthopaedic surgeon working at St. Georg General Hospital in Hamburg, Germany, under the direction of his boss, Prof. Dr. Buchholz.

Similarly to Gunston, Engelbrecht was inspired by Sir John Charnley's work with his “cemented low-friction hip system.” After being exposed to the issues encountered by Frank Gunston with his polycentric knee, Engelbrecht, with the support of his boss Prof. Dr. Buchholz and the German company Waldemar Link, decided to develop a more biomechanical implant in 1967 (22). This led to the development of the very first cemented low-friction unicompartmental knee implant in the world that actually worked well—both in terms of pain relief and functionality.

They called their implant the Sledge Prosthesis (from the German word

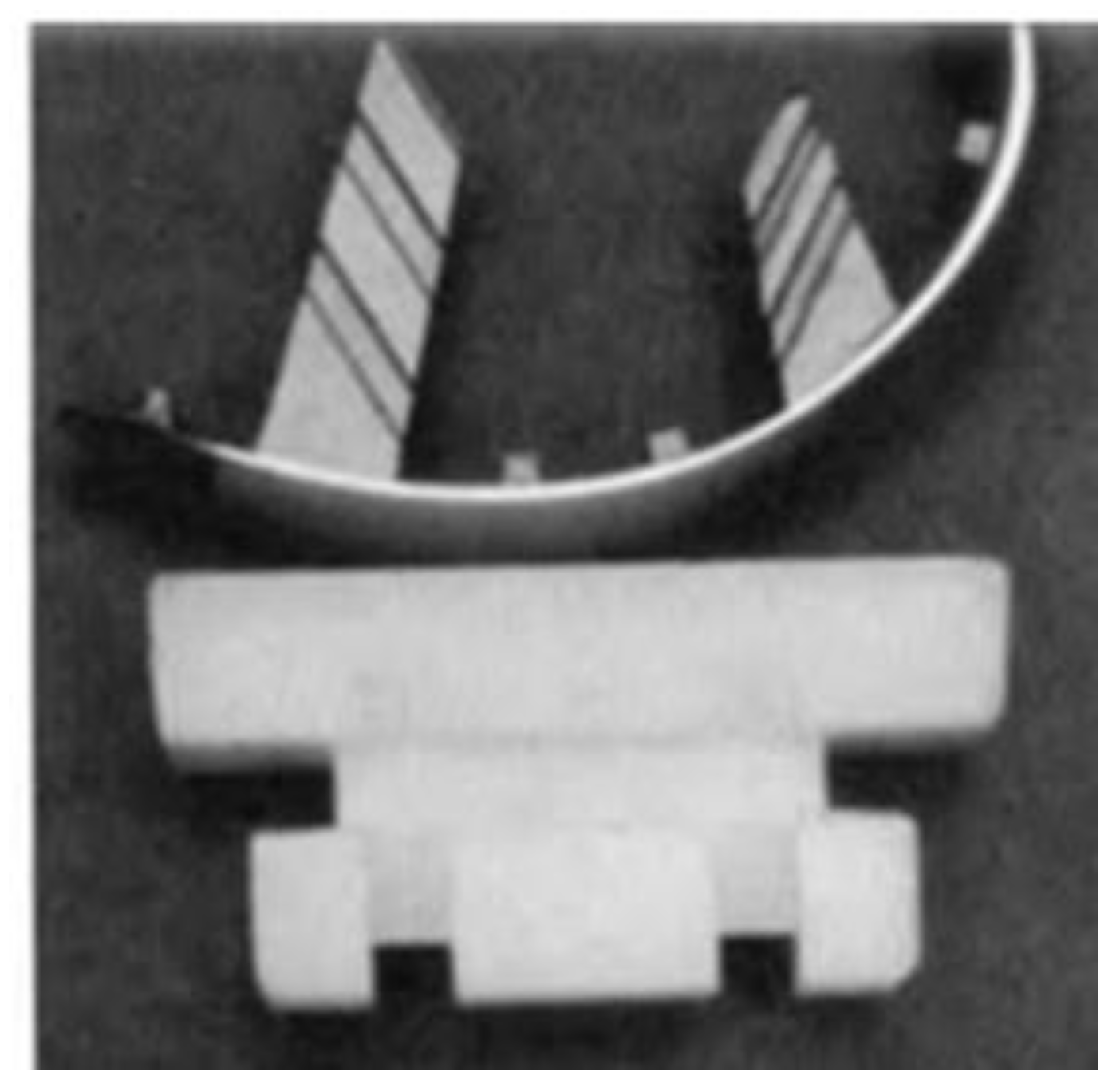

Schlitten) for its resemblance to an old German sled. The first generation of the Sledge was named the Model St. Georg, as it was implanted at the St. Georg General Hospital, Hamburg, in 1969 (

Figure 7).

The philosophy behind the Sledge implant was very simple: a cemented round metallic resurfacing femoral implant articulating freely with a flat plastic cemented tibial component, relying entirely on the patient’s anatomy for stability (22).

With the Sledge prosthesis, Dr. Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz introduced the so-called "round-on-flat principle", which became the basis for most UKRs yet to come. The early results were very encouraging, and they published their first paper in German in 1971, showing a very high degree of patient satisfaction with a survival rate of 97% after two years of follow-up in a series that included 40 patients.

This was an outstanding result, especially considering that surgical indications at the time were very broad and included bicompartmental replacements for bicompartmental disease, advanced OA in patients with rheumatic disease and severe deformities, as well as severe tibial plateau fractures (22).

At the beginning of the 1970s, interest in developing a functional, reproducible, and accessible UKRs began to spread among various orthopedic schools around the world. The conceptual legacy of Gunston and Engelbrecht, along with the influence of Charnley’s total hip arthroplasty, served as a foundation for multiple surgeons to develop their own designs, adapted to their technical and philosophical contexts. This phase, less experimental and more pragmatic, aimed for surgical reproducibility, commercial availability, and sustainable clinical outcomes.

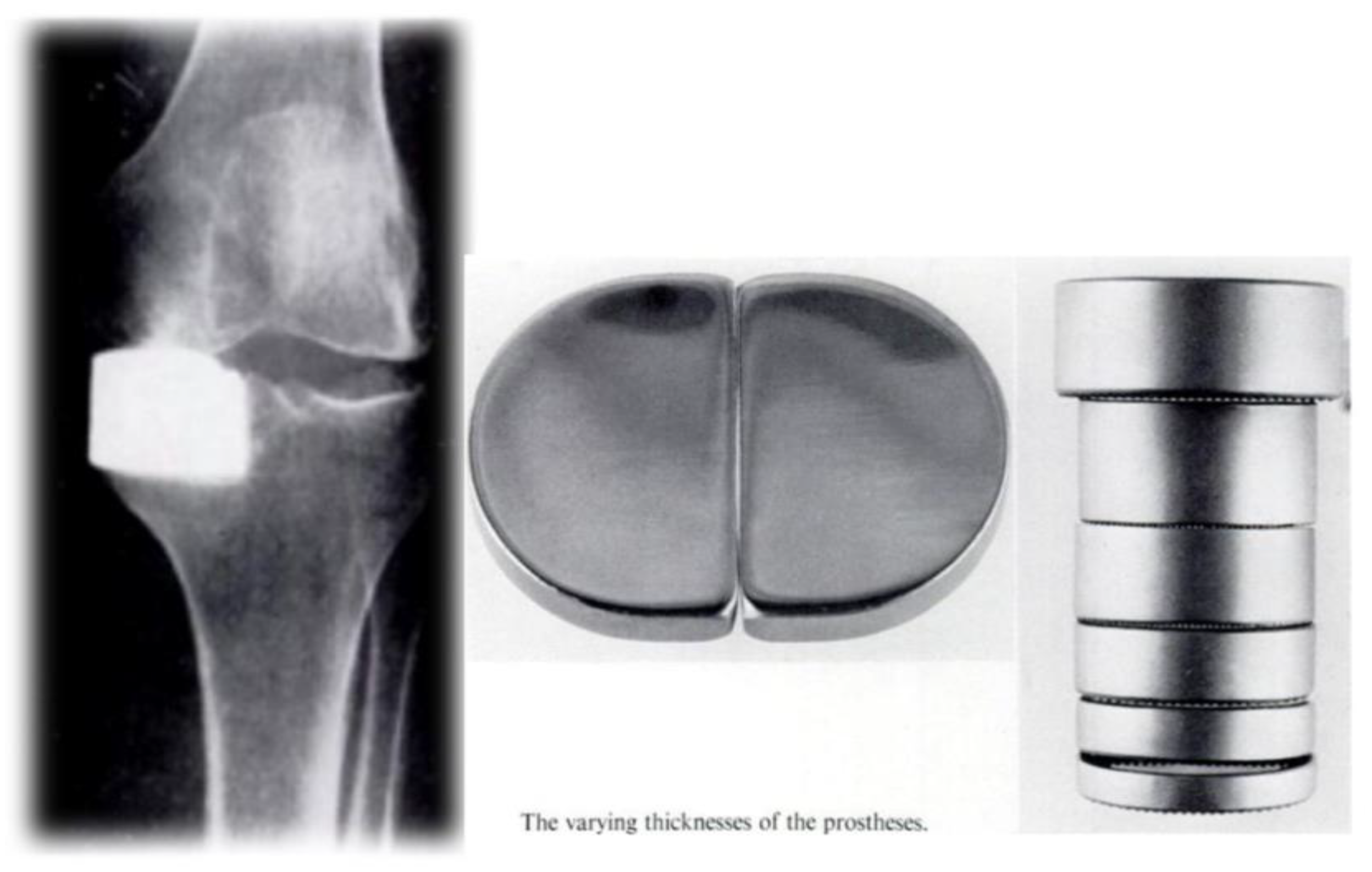

At Wrightington Hospital in England, Sir John Charnley collaborated with the Thackray Company from Leeds to develop his own UKR prosthesis in the early 1970s (23). The prosthesis was called Charnley's “Load Angle Inlay Knee Prosthesis.” With this implant, he introduced the concept of “reverse materials,” employing polyethylene runners in the femur that conformed to the curvature of the femoral condyle, and a flat metallic tibial component at the upper end of the tibia. All components were bonded to the bone using cement (23) (

Figure 8).

Although Charnley’s knee prosthesis design was innovative, the early results were disappointing, and the implant was later abandoned. A report published by R.J. Minns and K. Hardinge in 1983 on Charnley’s implanted prostheses documented multiple failures, including several problems due to polyethylene wear and deformation, and some cases of tibial component loosening (24).

In 1971, at the Manchester Royal Infirmary in England, Mr. N.E. Shaw and R.K. Chatterjee developed their own UKR prosthesis called “The Manchester Prosthesis” (25). Its design was very similar to the one developed by Frank Gunston at Wrightington. However, the Manchester prosthesis featured a modification: the partially constrained element of the tibial component was changed to an unconstrained flat design, similar to that previously used in the Sledge Model St. Georg by E. Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz (25) (

Figure 9). Although the early results with this prosthesis were very good, the reasons for its later abandonment remain unclear.

At the same time, with the aim of improving the results of Gunston’s Polycentric Knee, M.E. Cavendish and J.T.M. Wright from the Liverpool Orthopaedic School developed their own UKR prosthesis in 1972. They called the implant “The Liverpool Knee Joint System,” which was a modification of Gunston’s design (26) (

Figure 10). Although the early results with this prosthesis also appeared promising, the Liverpool Knee System was later abandoned.

While the specific reasons for abandoning both the Manchester and Liverpool UKR implants are unclear, the authors of this review suggest that the wide indications for surgery at the time may have led to inconsistent outcomes, particularly in the hands of less experienced surgeons.

In 1973, an American orthopaedic surgeon from Santa Monica, California, named Leonard Marmor, developed his own UKR prosthesis with significant support from the Richards Manufacturing Corporation (which later became part of Smith & Nephew) (27). Although his publications do not clearly identify the inspiration for his design, it is likely he drew from Frank Gunston’s work.

After reviewing Marmor’s publications, it becomes evident that he followed the same principles described earlier by E. Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz in 1967: a round metallic femoral implant articulating freely with a flat plastic tibial component. Marmor named his implant the “Marmor Prosthesis” and published his first report in 1973 (27) (

Figure 11). The report included results from a series of 32 patients with a follow-up of only 1 to 4 months. The very early results were encouraging, and like the first series by Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz, Marmor included cases of bicompartmental replacement in patients with rheumatic disease and severe deformities (27).

In 1974, Philippe Cartier, a French orthopaedic surgeon newly appointed as a consultant in Rouen, France, was tasked with developing a knee arthroplasty unit at his hospital. A few months prior, while still working in Paris, he had seen a video of the Marmor prosthesis. Cartier then decided to travel to the United States to meet Marmor and learn the principles of the implant directly from him.

Soon after his return to France, Cartier implanted the first Marmor prosthesis in Europe, at his small hospital in Rouen (28). Thanks to his good results, he later expanded the use of the Marmor prosthesis throughout France, and surgeons in neighboring European countries followed his example. Years later, Henri Dejour and Deschamps from the Lyon Orthopaedic School adopted some of Cartier’s principles, leading to the development of one of the most successful French UKR prostheses: the Tournier Prosthesis, which remains successful today (28).

The 1970s witnessed the definitive transition from experimentation to the consolidation of UKRs. While the 1960s represented the birth of basic biomechanical principles—such as the concept of low friction, cemented fixation, and the round-on-flat philosophy—the end of the decade marked the beginning of large-scale clinical validation.

This period was characterized by greater rigor in data collection, the publication of series with systematic follow-up, and the progressive improvement of original designs. Surgeons like Engelbrecht, Buchholz, and Marmor were not only implanting prostheses; they were documenting, evaluating, refining, and proposing a new way of understanding partial arthroplasty. It was at this point that the role of the surgeon evolved from purely technical to truly scientific: the “man of science” who measures, compares, and argues.

This approach marked a qualitative shift in the evolution of PKRs, as it laid the groundwork for what would later become major national registries, survival studies, and multicenter analyses. And it was precisely at that moment that the pioneers became benchmarks.

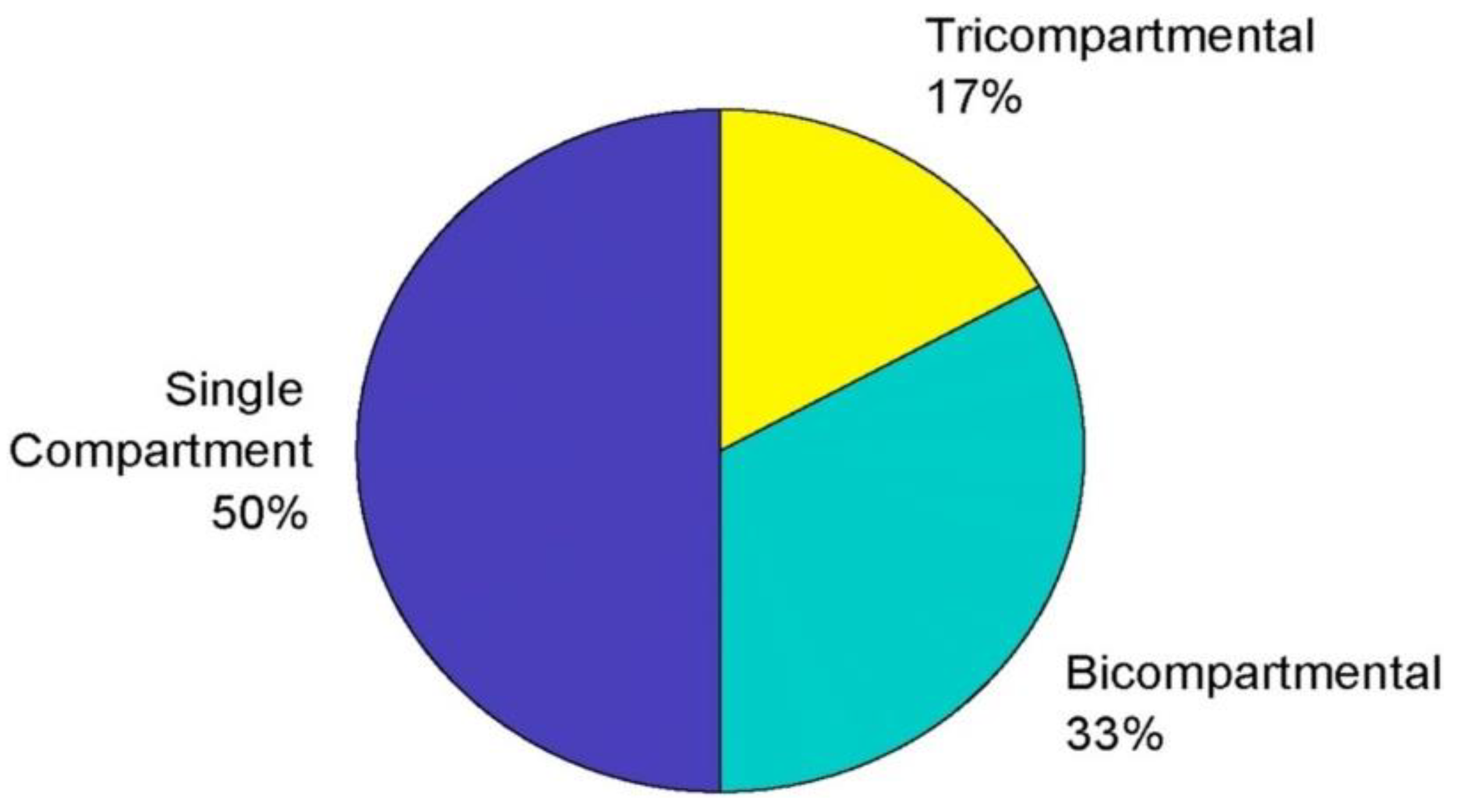

In 1976, Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz published what is believed to be the first large series of UKR implants in English. They reported the outcomes of 450 UKR Sledge Model St. Georg prostheses implanted in 294 patients, including 177 medial UKRs, 66 lateral UKRs, and 207 simultaneous bicompartmental UKRs, showing a survival rate of 87% after four years of follow-up and very high patient satisfaction (30). These results are impressive considering that one-third of the prostheses were implanted in patients with advanced rheumatic disease with severe deformity.

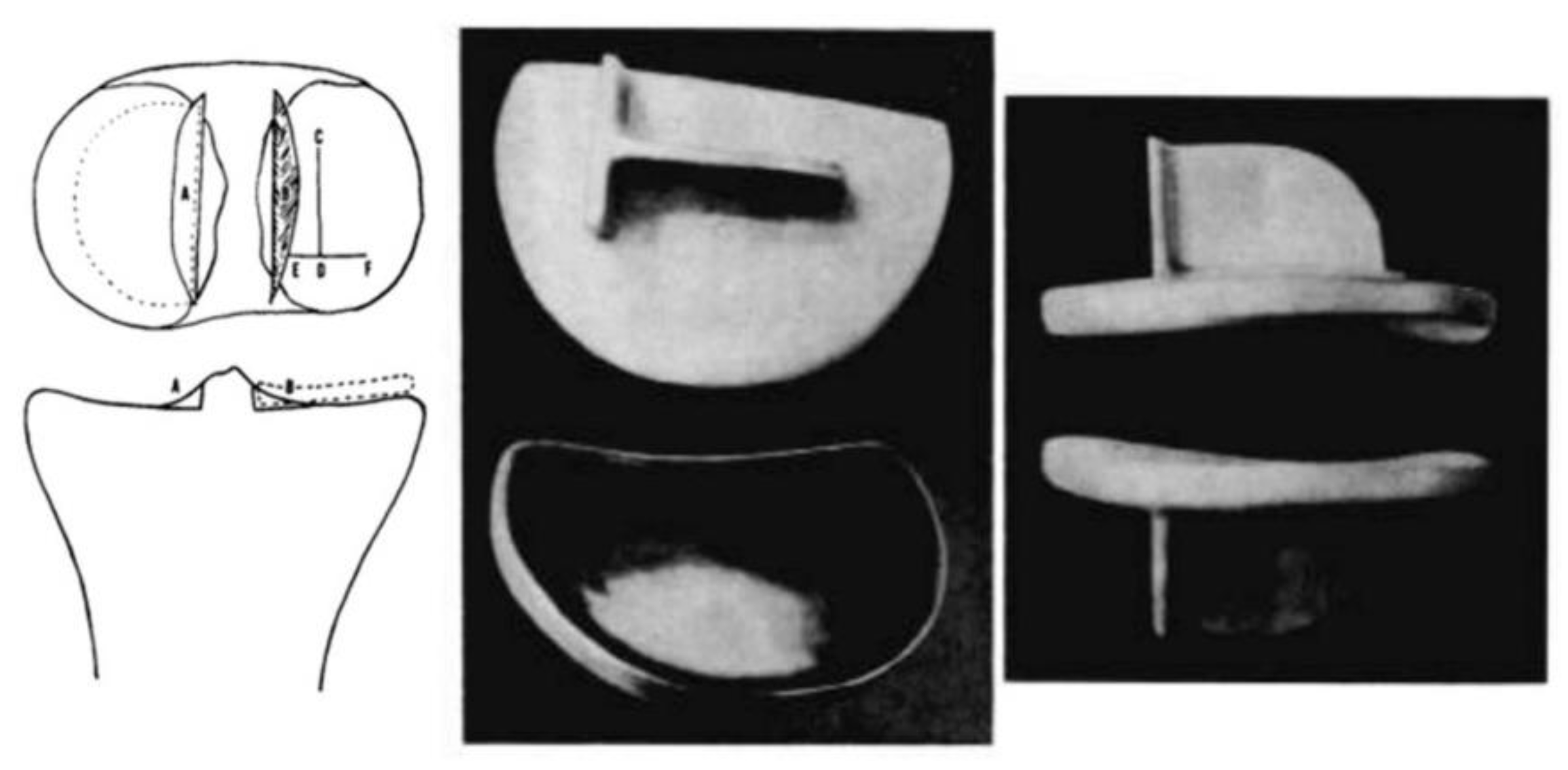

After analyzing these results and performing revisions, Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz modified the tibial polyethylene component, resulting in a more anatomical tibial implant in 1976 (30) (

Figure 12).

Four years later, in 1979, Leonard Marmor published the first large series of his Marmor prosthesis in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – American Volume. He reported on 56 UKRs with a survival rate of 91% at four years of follow-up, again showing very good patient satisfaction (31). While his series was not as extensive as that of Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz, the results were very encouraging.

By then, with the support of the Richards Manufacturing Corporation, Leonard Marmor and his prosthesis were gaining popularity in North America, and he has often been referred to as “the father of modern UKR.” However, the authors of this manuscript believe that E. Engelbrecht, Prof. Dr. Buchholz, and Frank Gunston are equally deserving of this title.

The Marmor prosthesis followed the principles of Gunston’s Polycentric Knee and Engelbrecht and Buchholz’s Sledge Model St. Georg prosthesis: a cemented round-on-flat implant, a concept that served as the foundation for the vast majority of UKRs to come, introduced by Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz in 1967.

It is also important to highlight that the early contributions of Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz did not receive the international recognition they deserved. This was partly because Prof. Buchholz, known as “the German Charnley,” was a general surgeon with a broad practice including orthopaedic pathology, and he was not fluent in English (32). Their first publication was only available in German, which limited its international exposure, particularly in North America.

Beyond the Sledge prosthesis, Prof. Dr. Buchholz developed many innovative orthopaedic implants, and he was the first to propose adding antibiotics to cement during hip and knee arthroplasties (33). He also introduced one-stage revision surgery and early debridement with retention of implants for infected joint replacements (34).

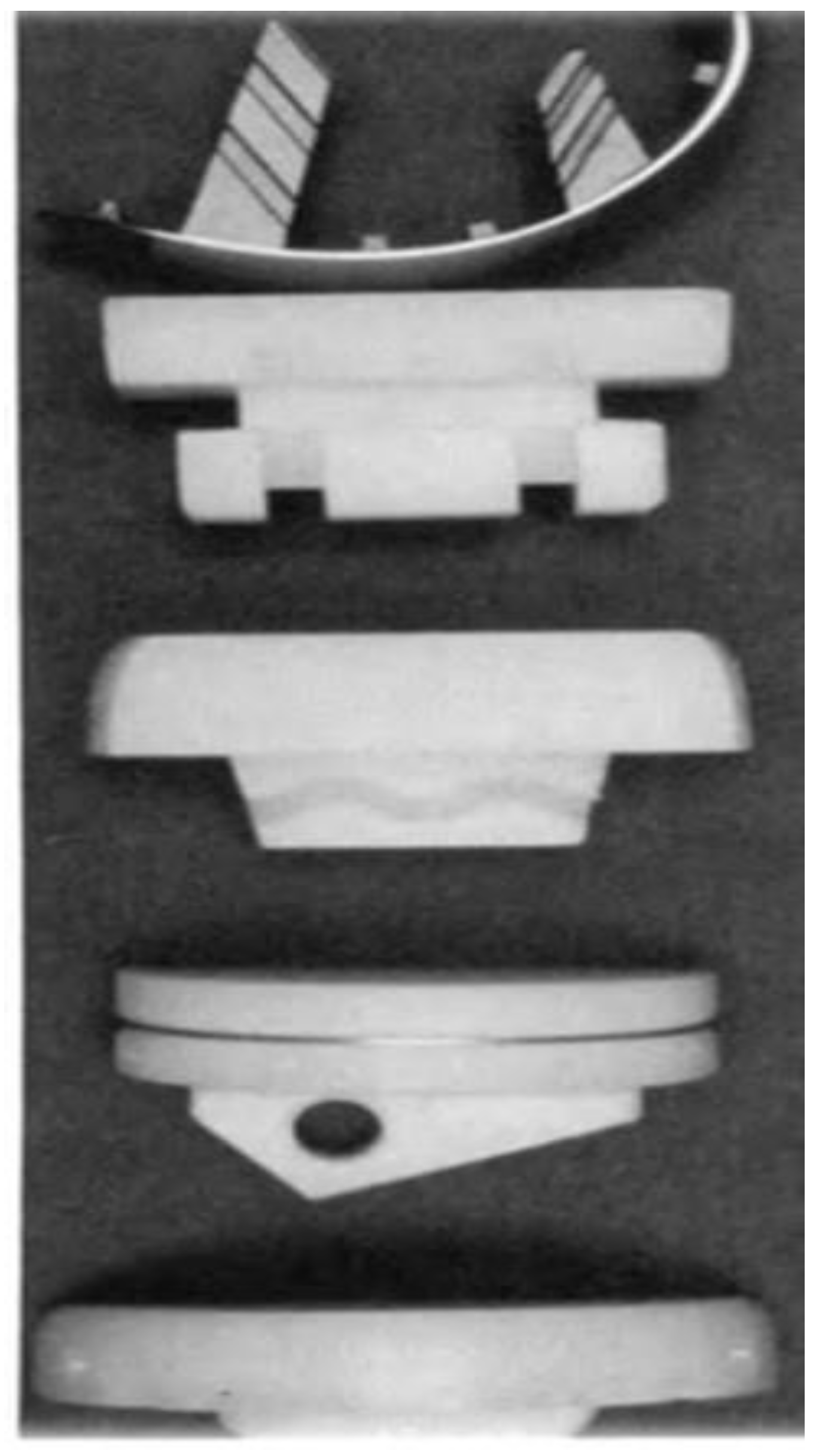

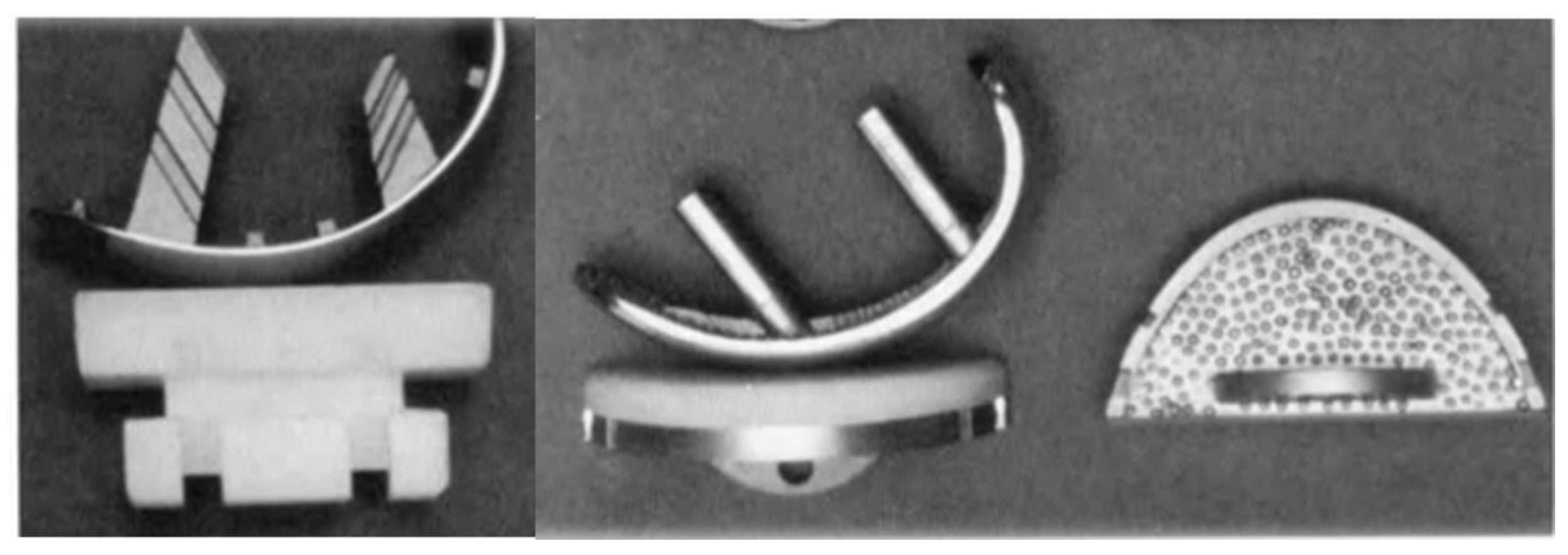

In 1981, at the newly opened ENDO-Klinik Hamburg—a clinic exclusively dedicated to arthroplasty founded by Prof. Dr. Buchholz—the Sledge prosthesis underwent further modifications, particularly to its femoral component (

Figure 13). The original keel fixation system was replaced with a peg-based fixation system, and a metal-back version of the tibial component was also introduced. This second generation of the Sledge prosthesis was named the Sledge Model ENDO, also known as the Link Sled or ENDO-Link UKR.

This would be the final modification of the Sledge prosthesis, which remains unchanged to this day. The sagittal shape of the femoral component has stayed the same since it was originally derived from multiple sagittal cross-sections of the femoral condyles. The transverse curvature resembles an arch with an original 18 mm radius. For the Sledge Model ENDO (Link Sled), the radius was enlarged, as increased varus deformity and high loads could otherwise cause excessive material pressure and higher wear of the polyethylene. This design change achieved a 20% reduction in wear (35).

It is also noteworthy that in the early 1980s, there were only two orthopaedic institutions in the world exclusively dedicated to arthroplasty: Sir John Charnley’s Centre for Joint Replacement at Wrightington Hospital, UK, and Prof. Dr. Buchholz’s ENDO-Klinik Hamburg, Germany. It is no coincidence that two of the greatest minds in orthopaedics—Sir John Charnley and Prof. Dr. Buchholz—conducted their work in these landmark institutions (309).

Leonard Marmor deserves tremendous recognition for championing this philosophy and is credited with introducing and expanding the use of UKR implants in North America during its early years. Likewise, Philippe Cartier from France and John Newman from the UK also deserve credit as early advocates of the UKR philosophy, especially during the difficult period when “The Rebels” began their crusade against UKRs.

The early years of the 1980s marked the beginning of a critical phase in the evolution of UKRs, characterized by both commercial growth and a growing polarization within the orthopaedic community.

The early 1980s were a time when many modular metal-back implants from different companies were made available as an alternative to the Sledge and Marmor prostheses. It was also the time when the Oxford mobile-bearing knee UKR system was designed by John Goodfellow and John O’Connor (36). But as in any other field of industry, when a new technology becomes popular and many companies start developing their own implants, critical voices will arise.

The poor results that popular surgeons in America, such as John Insall, David Laskin, and Paolo Aglietti, obtained from UKRs—combined with the legal dispute between Leonard Marmor and the Richards Manufacturing Company over the patent of the Marmor prosthesis—reduced the popularity of UKR in the early 1980s. Furthermore, in North America, where the modern Total Knee Replacement (TKR) was developed by John Insall, TKR became the gold standard for treating knee osteoarthritis (28, 37).

According to Phillippe Cartier from France, Insall, Laskin, and Aglietti called UKR surgery “Hocus-Pocus” and advised the orthopaedic community to avoid this implant and use his recently developed total condylar knee (TKR) instead—even in cases where unicompartmental disease was present (28).

At a time when the indications and surgical technique for UKRs were not entirely clear—and many companies had started developing their own UKRs, with some showing very low standards of quality—the position taken by John Insall and the American Orthopaedic School against the use of UKRs almost led to the death of the UKR philosophy. During the 1980s, more and more orthopaedic surgeons preferred to use the modern TKR developed by Insall rather than the more “challenging” UKRs.

As the 1980s progressed, UKRs found themselves at a crossroads. Although the initial enthusiasm of the 1970s had been overshadowed by fierce criticism from certain North American authorities, a small group of European surgeons persisted in their use, perfecting the indications and refining the surgical technique.

This period was not marked by major industrial developments or spectacular product launches, but rather by the quiet and steady work of clinicians who, guided by their outcomes, chose to swim against the tide. These were the years of resistance—of individual effort sustained by conviction, of systematic study, and meticulous publication. For this reason, the era can be described as that of the "Sole Soldiers": surgeons who kept the philosophy of UKRs alive even when the orthopedic community seemed to have shifted overwhelmingly toward total knee arthroplasty.

During the 1980s, only a few European surgeons continued using UKRs: E. Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz in Germany, Philippe Cartier in France, the Bristol and Oxford Knee School in the UK, and the Swedish and Danish Schools of Orthopaedics. Thanks to the resilience of these few surgeons—especially Philippe Cartier from France, E. Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz from Germany, as well as John Newman from the UK—the indications and surgical techniques for UKRs were redefined. The long-term outcomes significantly improved, attracting more and more surgeons again to the field of UKRs.

Special credit needs to be awarded as well to John Goodfellow, John O’Connor, and the entire Oxford Knee Orthopaedic School for the development and expansion of their own UKR mobile-bearing philosophy. This philosophy, although different from the one followed by fixed-bearing supporters, has also contributed tremendously to the expansion of the UKR philosophy as a whole.

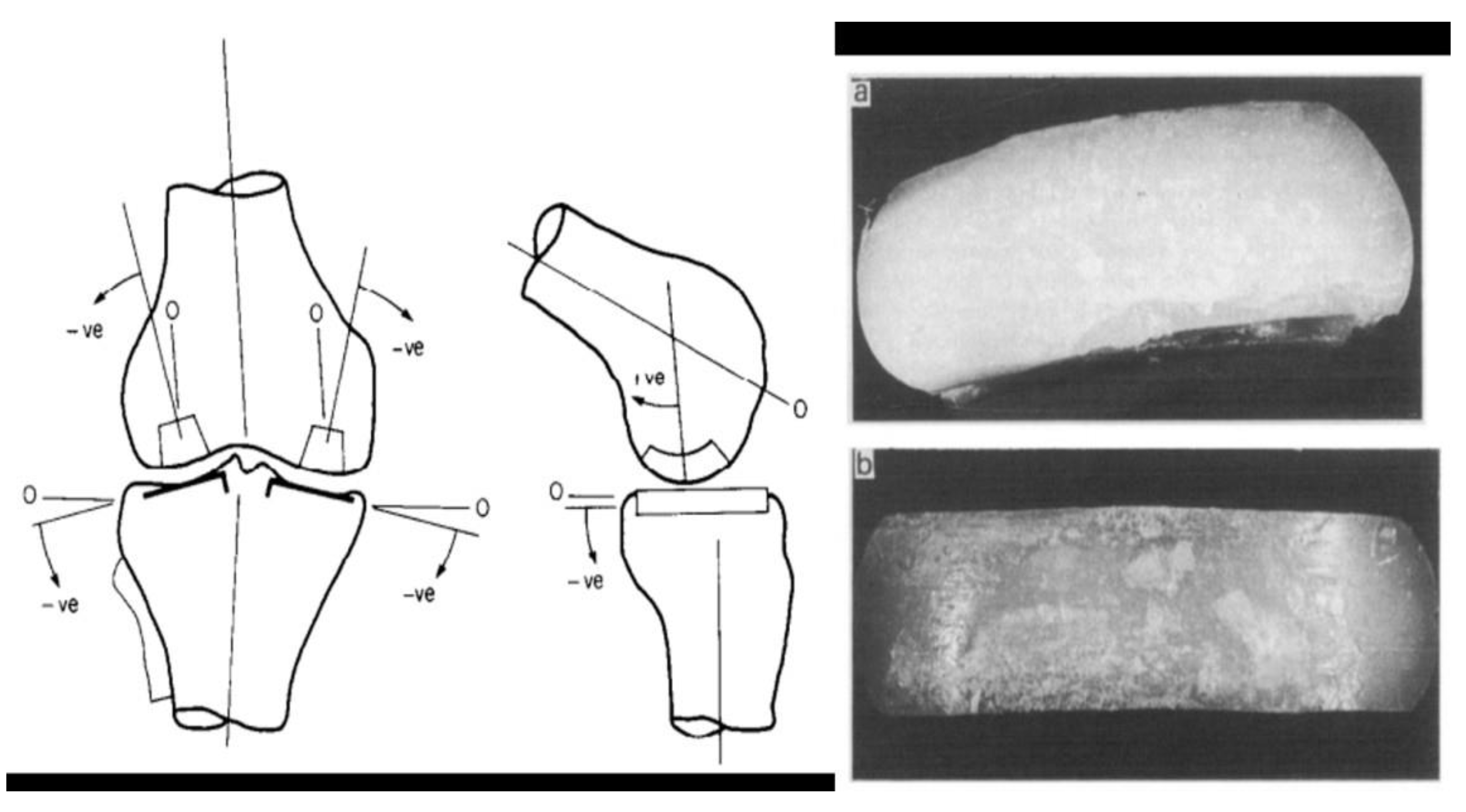

The late 1980s and early 1990s were characterized by the emergence of many high-quality publications supporting the utilization of both mobile and fixed-bearing UKRs. In 1987, E. Engelbrecht and his group published the results of 1,205 all-poly Sledge Model St. Georg implants with a 10-year survival rate of 86.8% (35). These are outstanding results, considering that this was obtained with the first generation of Sledge (the Model St. Georg) and with indications that at the time were still very broad. However, after a deeper analysis of their results, they ended up redefining their indications, advising the utilization of UKRs only in patients with unicompartmental disease and excluding patients with rheumatic disease and severe deformity (35).

It is common in the field of orthopaedics to see that the excellent results obtained and published by surgeons with implants they have developed are very difficult to replicate in the hands of non-developer surgeons—the so-called “developer’s publication bias.” It is very interesting to note that this phenomenon was not seen with the Marmor prosthesis or with the Sledge Model St. Georg prosthesis. This notion was supported by publications of non-developers like Olsen from Kolding, Denmark, who in 1986 published a series of 66 all-poly tibia UKRs with a 91% survival rate at six years of follow-up using the first generation of Sledge prosthesis: The Sledge Model St. Georg (38). Furthermore, Niel Christiansen from Sweden implanted 576 first-generation Sledge Model St. Georg devices, obtaining an outstanding 95.6% survival rate at nine years of follow-up, and published his results in the Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research journal in 1991 (39).

In 1996, Philippe Cartier published his ten-year follow-up with the use of the Marmor prosthesis. By then, Cartier had already redefined his indications and surgical technique. His series included 60 implants in 55 patients, with a survival rate of 93% at a minimum follow-up period of 10 years (40). One of the most important contributions of Cartier’s publications to the orthopaedic community was to highlight the importance of slight under-correction when performing UKRs in the context of a varus deformity and the importance of using an appropriate polyethylene thickness (40).

In 1997, Suhail Ansari from the Baylor University Medical Centre, Texas, USA, together with Mr. John Newman and Christopher E. Ackroyd from the Bristol Orthopaedic School, England, published their results with the utilization of the first-generation all-poly tibia Sledge Model St. Georg. Their series included 451 UKRs with an 87% survival rate at ten years of follow-up. A very encouraging result for non-developers using a first-generation implant (41).

With the turn of the millennium, UKRs began to regain prestige after years of stigmatization. Long-term follow-up publications from Europe, validation by non-developer surgeons, and improved surgical accuracy thanks to new guides and instrumentation were redefining the landscape. However, in parallel, a new controversy was emerging.

Unlike the ideological rejection of the 1980s, this time the doubts arose from a biomechanical standpoint. The first observations came from the United States and focused on a specific component: the all-polyethylene tibial implant. Interestingly, the most solid clinical evidence up to that point came precisely from prostheses with this design, such as the Marmor or the St. Georg Sledge. Nevertheless, a series of studies with notable methodological limitations managed to establish an adverse narrative, initiating what could be considered a poorly substantiated scientific crusade with significant international impact. In particular, concerns originally related to total knee replacements (TKRs) were extrapolated to UKRs, casting doubt on the use of all-poly tibial components despite robust evidence supporting their effectiveness.

In 2007, T.J. Aleto and his group from Indiana, USA, published an article entitled “Early failure of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty leading to revision” (42). After studying the causes of UKR revisions—25 of which were implanted in different institutions where the type of implant was not specified—they found that 15 of them failed due to medial tibial plateau collapse, of which 13 were all-poly tibia UKRs. They concluded that all-poly tibia UKR implants were the cause of the tibial plateau collapse (42). However, there are issues with this conclusion. First, it is important to highlight that all the all-poly implants were implanted with degrees of slope, and in addition to this, the authors did not specify what type or brand of implant was originally implanted (42). Despite its lack of scientific rigor, this article produced an earthquake-like effect on a small group of surgeons and scientists—a group that started a crusade against the all-poly philosophy in UKRs.

In 2009, Cesar L. Saenz and his group from Baltimore, USA, conducted a study of 144 all-poly tibia UKRs (EIUS from Stryker) and found a concerning 11% revision rate at three years of follow-up with the use of this prosthesis (43). Like Aleto, Saenz blamed the all-poly tibia as the cause of these early failures, although the EIUS implant from Stryker was already underperforming in some National Joint Registries (44), and, therefore, it was likely that the implant design itself was the problem, not the all-poly tibia philosophy. This was later confirmed when the implant was recalled a few years later by the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) (45).

Although lacking scientific rigor, the previous papers (Aleto et al. and Saenz et al.) served as a basis for Scott R. Small and his group from Mooresville, Indiana, USA, to develop and publish a biomechanical study comparing all-poly tibia implants vs. metal-back tibia implants in 2011 (46). In their study, Scott et al. implanted 12 cemented UKRs into 12 composite tibias. Six of them were fixed-bearing all-poly tibia Repicci II UKRs, and six of them were metal-back mobile-bearing Oxford UKRs (46). Their study concluded that “all-polyethylene tibial components exhibited significantly higher strain measurements in each femoral position in composite tibia models compared to the metal-back ones.” Although this study was well done from a methodological point of view, the big downsides of this study were the very small number of UKRs implanted and the fact that the composite tibia does not behave in the same way as human bone (46).

One year later, in 2012, C.H. Scott and his group from Edinburgh, including R. Nutton and Raj Bhattacharya, published a clinical study comparing two cohorts of UKRs: a fixed-bearing all-poly tibia UKR implant vs. a mobile-bearing metal-back UKR implant (47). The implant chosen for the all-poly group was the Preservation UKR from DePuy (Johnson & Johnson), and the implant for the mobile-bearing group was the Oxford UKR. A total of 94 cemented all-poly UKRs (Preservation) and cemented mobile-bearing Oxford UKRs were analysed with a follow-up period between 2 and 7 years (47). In their well-presented cohort study, they found that the all-poly implant, the DePuy Preservation UKR, presented an unacceptably high rate of early failures when compared to the better-performing Oxford UKR. They concluded that the all-poly tibia was to blame for these early failures, but it seems that they repeated the same mistake Saenz had done in the past. Like Saenz, they used an implant that was already underperforming in some joint registries and had already been recalled in 2007, five years before the date of the publication of their study (48, 49).

Prof. Vaisian, a French hand surgeon, said:

“Everything has already been told, everything has already been written, but since we do not have enough time to read everything we can go on publishing.” (28)And they went on publishing.

In 2013, R. Scott and R. Nutton developed and published a new biomechanical study comparing cemented all-poly tibia implants vs. cemented metal-back tibia implants in a composite tibia model (50). They concluded that all-polyethylene medial UKR implants are associated with significantly more cancellous bone damage than metal-backed implants, even at low loads in their experimental system. The downsides of this study were similar to the study published a few years earlier by Scott R. Small et al: a very small number of UKRs implanted and the fact that a composite tibia does not behave in the same way as human bone (46, 50).

In 2018, Scott and Nutton presented a study with ten years of follow-up using the same cohort of patients and implants used for their 2012 study. They came to the same conclusion: an unacceptable early revision rate of all-poly tibia UKR when compared to a metal-back UKR implant (51). However, they made the same methodological mistakes they made in 2012, as the cohort used was the same. They used the same cemented all-poly UKRs Preservation from DePuy (Johnson & Johnson) cohort for comparison, an implant that was already underperforming in many registries and had already been recalled in 2007, 11 years before the date of the publication of their study (48, 49, 51).

In 2018, the same authors developed and published a further biomechanical study comparing cemented all-poly tibia implants vs. cemented metal-back tibia implants in a composite tibia model (52). In this new study, they implanted ten cemented UKRs into composite tibias. The implant chosen for the all-poly tibia implant was the Sigma Partial from DePuy, and they concluded that the all-poly tibia components displayed greater volumes of pathologically overstrained cancellous bone than the metal-back implants of the same geometry. They further concluded that the increasing thickness of the polyethylene component does not overcome these pathological forces and comes at the cost of greater bone resection (52). The downsides of this study were similar to the study published a few years earlier by the same authors: a very small number of UKRs implanted and the fact that composite tibia does not behave in the same way that human bone does.

Following the wave of biomechanical studies using composite tibias and clinically questionable analyses that challenged the performance of solid polyethylene tibial components (all-polyethylene), several European groups — and some North American ones — began publishing high-quality clinical evidence supporting the use of all-poly tibial UKRs with long-term results.

These publications, featuring large series, extended follow-up periods, and well-defined comparative methodologies, not only countered the earlier criticisms but also laid the foundation for the contemporary evidence supporting the all-poly philosophy in UKRs. The methodological rigor, transparency of data, and replicability of outcomes in independent centers restored this design’s status as a valid and effective option — particularly in experienced hands and with well-selected surgical indications.

In 2008, John Newman, R.V. Pydisetty, and C. Ackroyd from Bristol, England published a 15-year follow-up cohort study comparing a cemented fixed-bearing all-poly tibia implant versus a cruciate-retaining modular TKR implant. The implant of choice for the UKR group was the first-generation all-poly tibia Sledge Model St Georg, and 52 UKRs were implanted. At 15 years of follow-up, the survival rate for the UKR group was 89.9% versus 78.7% for the TKR group (Kinematic Modular TKR–Howmedica, Rutherford, New Jersey). The median Bristol knee score of the UKR group was 91.1 at five years and 92 at 15 years, suggesting little functional deterioration in either the prosthesis or the remainder of the joint. Furthermore, they concluded that:

“In a randomized group of patients with unicompartmental disease, the results for UKR are as good as those for TKR and show no greater tendency to fail for at least 15 years.” (53)

In 2009, Sebastian Lustig together with Phillip Neyret and the Lyon Orthopaedic Group from France published a ten-year follow-up study with the use of a cemented fixed-bearing all-poly tibia UKR. The implant of choice was the HLS-type Evolution from Tornier. 172 all-poly tibia UKRs were implanted, showing an outstanding survival rate of 95.6% at ten years of follow-up. The rate of satisfied or very satisfied patients was 97.2%. After a deep analysis of their results, they concluded that:

“The option of an all-polyethylene tibial implant, with minimal bone cuts, makes excellent long-term results possible.” (54)

In 2011, Phillipe Cartier from France, Thomas J. Heyse from Germany, and Geert Peerman from Belgium published a cohort study comparing the 15-year follow-up results of a cemented all-poly tibia UKR versus the metal-back cemented and uncemented versions of the same prosthesis. The implant of choice for this study was the Genesis Unicondylar–Accuris system from Smith & Nephew. In total, 223 UKRs were implanted, with a survival rate for the all-poly tibia version of the implant of 93.3% at 15 years of follow-up versus 90.4% for the uncemented metal-back version and 82.5% for the cemented metal-back version of the same implant. After a deep analysis of their results, they concluded that:

In 2015, Francesco Zambianchi, together with Fabio Catani and his group from Italy, published a five-year follow-up cohort study comparing the results of an all-poly tibia UKR implant vs. a metal-back UKR implant, also dividing the groups between low- and high-volume surgeons (cut-off number: 50 UKRs per year) (56). In total, 145 UKRs were implanted, with a survival rate of 93.1% for both all-poly and metal-back implants at five years follow-up in the high-volume surgeon group. After a deep analysis of their results, they came out with the following revealing conclusions:

“If implants by low-experienced surgeons are excluded, all-poly and metal-back UKRs showed good overall clinical and functional outcomes with similar revision rates.”

“These data underline the role of the surgeon and his experience over prosthetic designs, models, and geometry of fixation.”

The value of experience and a minimum number of UKR surgeries performed per year were highlighted in this study—a concept that is well-accepted nowadays and is supported by the data of many Joint National Registries (57). Further conclusions of this study were that malalignment, and not implant design, impairs outcomes. Furthermore, they stated that:

In 2016, Nael Hawi, Mustafa Citak, and their group from the ENDO-Klinik Hamburg, Germany, presented the eight-year follow-up results of the second generation of the Sledge: The Model ENDO (also known as the Link Sled) (58). One hundred all-poly tibia Link Sled UKR prostheses were implanted, showing an excellent survival rate of 95.4% at eight years follow-up. The results in terms of PROMS were also very encouraging. They published that:

After a deep analysis of their results, they concluded that:

“In summary, an all-polyethylene tibial component has equivalent survivorship to modular metal-back designs and that implant selection does not seem to have a great influence on the outcome, but rather the success depends on appropriate indications and surgical technique.” (58)

In 2020, D. De Bruce together with John Newman published the ten-year follow-up results of the all-poly tibia Uniglide UKR from Smith & Nephew. The Uniglide UKR was implanted in 214 patients and showed a good survival rate of 89.1% at ten years of follow-up (59).

In 2021, Merrill Lee, together with Sen Jen Yeo and his group from Singapore, found no difference in a cohort study comparing the 10-year results of an all-poly tibia UKR implant vs. the metal-back version of the same implant (60). The implant chosen for the cohort study was the Miller-Galante UKR from Zimmer. In total, 146 UKRs were implanted, with a survival rate of 92.3% for the all-poly tibia version and 91.1% for the metal-back version. In addition, a deep analysis of their results showed:

In 2021, Fabio Catani and his group from Italy published a new study to assess the midterm results of an all-poly tibia UKR implant. They implanted 142 Journey UKRs from Smith & Nephew, with a survival rate of 96.5% at five years of follow-up (61). Although some may argue that a mid-term follow-up of five years is not long enough to properly assess an implant, the authors of this review would respectfully disagree, as the main concern of the group against the utilization of all-poly tibia UKRs was the unacceptably high rates of early failures.

In 2021, Andrew Porteous from Bristol published the results of an all-poly tibia implant, the “St Georg Sled” (62). They analyzed 496 UKRs implanted in their institution between 1974 and 1994. According to their publication, the prostheses implanted were all the cemented all-poly tibia “St Georg Sled”, showing a survival rate of 86% at 10 years of follow-up and 75% at 20 years. These results are not bad for a first-generation implant, the Sledge model St Georg, which was designed in 1967 by E. Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz.

However, when reviewing this paper, some methodological concerns arise. First, although one could argue that the term Sled could be used as equivalent to the term Sledge, the term Sled is mainly used for the second generation of the Sledge: the Model ENDO or Link Sled. With very few exceptions, almost every article found in the literature uses the term Sledge Model St Georg or St Georg alone when referring to this implant (the 1967 model), including studies carried out in the same institution by Mr. John Newman.

Although naming the implant the

St Georg Sled could be seen as not entirely wrong from the lexical point of view, it may be misleading for the reasons previously explained. On page 2 of this article (Porteous et al.), we can see Fig. 1, which shows a photo of the St Georg Sled prosthesis (

Figure 14). The problem here is that the photo does not show the Sledge Model St Georg; it shows the second generation of the Sledge: the Sledge Model ENDO or Link Sled, wrongly named

St Georg Sled in the label of Fig. 1. This photo has nothing to do with the St Georg UKR prosthesis, even if we choose to call it

Sled instead of

Sledge.

Unfortunately, the report also states:

“A limitation is the change in femoral component design from a keel to peg-based fixation during the latter years of the study… but unfortunately, due to the historical nature of the cohort, we were not able to determine which patients had which design, and therefore included all in the cohort and reported the results transparently.” (62)

Furthermore, the authors of this study did not mention that an important change in the second generation of the Sledge—the Sledge Model ENDO or Link Sled—was a change in the radius of the transverse arch of the femoral runner, as well as the change from a keel to peg-based fixation, both reported in other literature.

Although the Sledge Model St Georg and the Sledge Model ENDO (Link Sled) share the same biomechanical principles stated by Engelbrecht and Prof. Dr. Buchholz in 1967, they are not the same implant and therefore cannot be mixed in the same cohort. In addition to the above, they have themselves stated that “they were not able to determine which patients had which design, and therefore included all in the cohort” (62). This is difficult to justify from a scientific study design perspective.

Although we have some issue with this study design, we could say that the results of this study can be referred to as the first generation of Sledge: the Model St Georg. For patients over the age of 65 years at the time of the index procedure, 93% of them died with a functioning prosthesis in situ, although we will never know which prosthesis was the one implanted in any of those patients: The Sledge Model St Georg or The Sledge Model ENDO (Link Sled).

Throughout the historical evolution of UKRs, the development of metal-back tibial components has played a fundamental role. While solid polyethylene (all-poly) tibial implants became popular in the early generations, advancements in orthopedic technology and evolving biomechanical demands led to the exploration of more versatile configurations. This gave rise to modular metal-back designs, featuring a metallic baseplate that allows for a wider range of combinations, more precise adaptation, and, in some cases, easier revision options. These designs, available in both fixed-bearing and mobile-bearing configurations, have been progressively optimized since the late 1970s and today represent one of the main surgical options in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty.

The concept of a modular metal-backed tibial component in UKRs can be traced back to the pioneering work of John Goodfellow and John O’Connor, who began developing the Oxford Knee in 1976. While the device was not implanted clinically as a true unicondylar prosthesis until 1982, their research laid the biomechanical and philosophical foundations for what would become the first UKR system to incorporate a metal-backed tibial baseplate and a mobile polyethylene bearing (63).

In the early 1980s, several fixed-bearing UKRs with metal-backed tibial components were introduced, reflecting a shift toward greater modularity and implant durability. These included the modular version of the Marmor Condylar Knee in the United States, the St. Georg Sled in Germany, the Lotus Unicondylar Knee developed by the Guepar Consortium in France, and the Lund Prosthesis in Sweden (35, 64). Prior to this period, UKR designs were predominantly all-polyethylene and cemented, with no widely used metal-back tibial components during the 1970s

Although the initial results with the use of metal-back implants were also very good (especially considering the wide indications used at the time), the crusade against the UKR philosophy initiated by Insall, Aglietti, and Laskin equally affected both metal-back and all-poly tibia implants (28). This campaign almost meant the death of the UKR philosophy, but as already stated in the all-poly section of this manuscript, many European surgeons continued with the utilization and development of good UKR implants, including E. Engelbrecht, Prof. Buchholz, Richard Marmor, Philippe Cartier, John Newman, as well as Mr. John Goodfellow and Mr. John O'Connor.

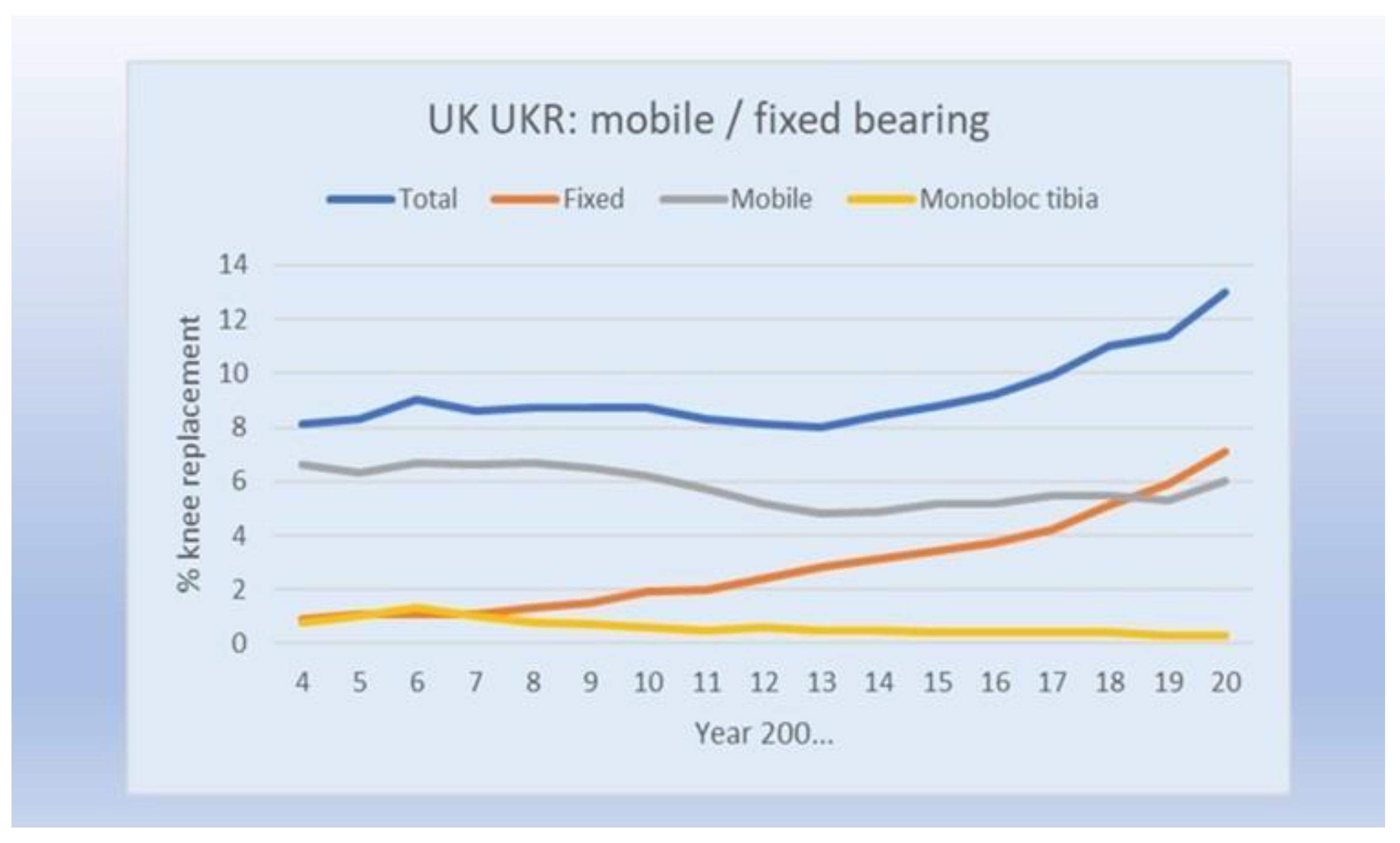

Many good-quality papers have been published since the late 1980s in support of the use of metal-back tibia UKRs, both mobile- and fixed-bearing implants. Since then—and contrary to what happened with the all-poly tibia implants—the metal-back UKR philosophy has never been questioned and remains the most frequently implanted UKR in many parts of the world (

Figure 2).

For those interested in the results of mobile-bearing metal-back implants, we invite them to explore the numerous papers available in the scientific literature on this topic. In this review, however, we are addressing only the fixed-bearing UKRs and will refer to them only from now on.

There have been plenty of good papers published showing the very good long-term survival and outcomes with the use of fixed-bearing metal-back tibia UKR implants.

Because the validity of metal-back fixed-bearing tibia UKR was never under scrutiny, we will share just the most recent good-quality papers on this topic:

In 2016, Jean-Noël Argenson and colleagues from Marseille, France, including Sébastien Parratte and Mathieu Ollivier, reported the 16-year survival rate of a fixed-bearing metal-back UKR implant, the Miller-Galante UKR from Zimmer, showing an excellent survival rate of 91.6% at 16 years (65).

In 2018, Philip Winnock de Grave and colleagues from Belgium analyzed the 10-year survival rate of the fixed-bearing metal-back ZUK prosthesis from the Lima Company. After analyzing 460 consecutive UKRs implanted in their institution, they found a survival rate of 94.2% at 10 years for this metal-back implant and very good patient satisfaction (66).

In 2020, Nick London and colleagues from Harrogate, UK, published their 10-year survival rate of a fixed-bearing UKR implant, the Miller-Galante UKR from Zimmer. After analyzing 91 consecutive medial fixed-bearing metal-back tibia UKRs performed in their institution in patients under the age of 60, they found a survival rate of 92.9% at 10 years of follow-up and very good patient satisfaction, with a mean OKS of 38.4 at 10 years (67).

In 2021, Kannan A. et al. published a multicentre study that analyzed the 15-year survival rate of different UKR implants included in the Australian National Joint Registry between September 1999 and December 2018 (68). They looked at different designs, including fixed-bearing all-poly tibia implants, fixed-bearing metal-back implants, and mobile-bearing metal-back implants. After analyzing 50,380 UKRs, they found that the implants with better survivorship were the fixed-bearing metal-back implants, with a survivorship at 15 years of 84%, compared to 77% for metal-back mobile-bearing implants and 73% for fixed-bearing all-poly implants.

Although this difference was statistically significant, registry studies have the downside of not taking into consideration the surgical volume performed by each surgeon or institution. It is currently accepted that UKR is a volume-dependent surgery, and therefore, the number of UKRs implanted per center or surgeon should have been taken into account for the results of this study to be properly analyzed.

Furthermore, the survivorship shown in this study for all types of UKR implants is far lower than what can be seen in high-volume centers (38–40, 53–61, 65–69). The results of this study further support the notion of UKRs being volume-dependent surgeries.

In 2021, Graham S. Goh and colleagues from Singapore published a study comparing the 10-year survival rate between men and women undergoing a metal-back tibia fixed-bearing UKR implant. Their study showed a 96% survivorship in both groups after analyzing 128 metal-back fixed-bearing UKRs at 10 years of follow-up (69).

Finally, in 2022, Francesco Benazzo and his group from Italy published the 15-year survivorship of a fixed-bearing metal-back UKR implanted in their institution. They analyzed metal-back UKRs implanted in two high-volume UKR centers. When revisions for infection were excluded, the survivorship of this fixed-bearing metal-back UKR was 90.3% at 15 years (70).

All the above papers are just a small selection of the many articles found in the literature supporting the use of metal-back tibia UKRs. However, it is important to highlight that these results are not different from those found when a fixed-bearing all-poly implant is chosen (38–40, 53–61).