1. Introduction

The Goldbach conjecture, one of the most enduring unsolved problems in number theory, posits that every even integer greater than 2 can be expressed as the sum of two prime numbers [

1]. The strong form of this conjecture, often referred to as the binary Goldbach conjecture, remains unproven despite extensive computational verification for numbers up to very large magnitudes [

2]. In this note, we explore a slight modification of this conjecture and provide a geometric interpretation that links it to properties of squares and semiprimes.

Specifically, consider the following variant: Every even integer greater than or equal to 8 is the sum of two distinct prime numbers. This adjustment excludes the cases (the only sum of identical primes) and , aligning with our geometric construction which requires distinct factors and (implying ).

We establish an equivalence between this variant and a geometric statement involving nested squares. This connection not only offers a novel visualization but also highlights the interplay between arithmetic progressions and the factorization of differences of squares.

2. Geometric Construction

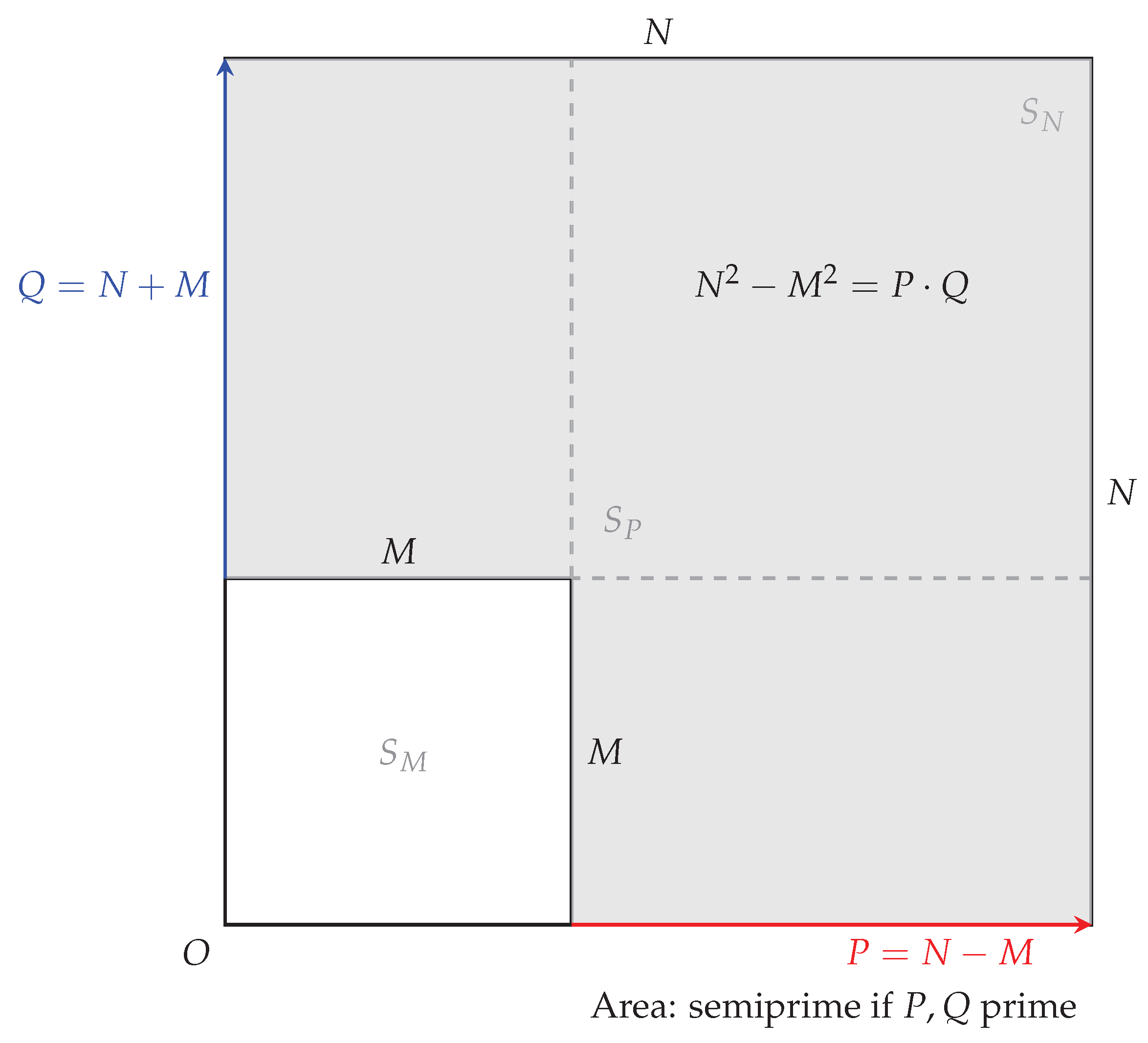

Consider a square with integer side length , so its area is . Inscribe within another square with integer side length M, where , such that shares one corner with (without loss of generality, the bottom-left corner). The region between and forms an L-shaped annulus with area .

The difference of squares factors as

Define

and

. We analyze the constraints on

P and

Q imposed by the bounds on

M:

Thus, we have and . Since , it is clear that .

The sum of these factors is

which is an even integer

(since

). The difference of the factors is

, which is also even.

Since P and Q have an even sum () and an even difference (), they must have the same parity. For P and Q to both be prime with , they must both be odd primes. Therefore, P and Q must be distinct odd primes.

The area is a semiprime (a product of two primes) if and only if both factors P and Q are prime. Our construction requires them to be distinct odd primes.

The variant of Goldbach’s conjecture is therefore equivalent to the following geometric assertion:

Theorem 1 (Geometric Goldbach Variant). For every integer , there exists an integer M with such that the L-shaped region between the squares and (sharing a corner) has area equal to a semiprime , where and are distinct primes.

This equivalence holds bidirectionally: If for distinct primes , we can set .

Since and are distinct, they must be distinct odd primes.

Since p and q are odd, their sum and difference are even, so and are integers.

We must check that M satisfies .

: . Since are distinct odd primes, this is true.

: . Since p is an odd prime, , so this is always satisfied.

Thus, any Goldbach partition (with distinct odd primes) corresponds exactly to a valid geometric construction with , , and , yielding the semiprime area .

Conversely, given a valid geometric construction with and both prime, then , so is the sum of two distinct primes.

To illustrate,

Figure 1 depicts the construction for a generic

N and

M.

3. Deeper Analysis and Implications

The above equivalence provides a bridge between additive number theory and geometric dissections. For a fixed , the conjecture is true if there exists at least one such that and are both prime. Since , this is precisely the statement that for a given , there exists a prime P in the range such that is also prime.

This is exactly the Goldbach partition for into two primes P and Q. As , . As shown, P and Q must be distinct odd primes. The geometric view, therefore, recasts the search for a Goldbach partition as a search for an integer M that defines an L-shaped “frame” with a semiprime area.

Computational evidence strongly supports the conjecture: For

N up to

(corresponding to even numbers up to

), such a partition has always been found [

2]. Analytically, the Hardy–Littlewood conjecture estimates that the number of such partitions

grows as

, suggesting not only that at least one partition exists, but that the number of them grows with

N [

3].

4. Novel Approach on this Perspective

From the previous analysis, we have

and

. The area

admits a natural geometric interpretation via the L-shaped region in

Figure 1.

This region consists of a vertical rectangle of dimensions (the top arm) and a horizontal rectangle of dimensions (the right arm, accounting for the full height N), yielding total area .

Alternatively, the dashed square (of side , positioned from the top-right corner of to the top-right corner of ) highlights a complementary decomposition: the L-shaped region equals the area of (namely ) plus two adjacent rectangles each of area (one horizontal along the bottom-right and one vertical along the top-left, excluding the overlap covered by ). This confirms , which expands to , verifying the identity tautologically.

The key geometric insight, however, derives from relating P and Q directly to the side lengths N and M. Observe that measures the extension beyond along either arm of the L-shape (horizontal width or vertical height). The full side N of thus decomposes as the inner side M plus this extension P, so . Meanwhile, extends this by adding the inner side M once more—geometrically, Q spans the full height N of plus the height M of , evoking a “doubled” vertical traversal from the shared corner O outward and inward.

Subtracting these lengths yields

and solving gives the explicit formula

For

(ensuring

), any distinct primes

with

(both odd, hence

even) produce an integer

satisfying

, as

(next prime after

) implies

. This bidirectionally links the arithmetic partition to the geometric embedding. Instead of focusing on the semiprime area

, we now focus on the set of distinct values of

M generated by straddling prime pairs. For a given

, let

be the set of all integers

M such that

Note that we implicitly consider

to ensure finite cardinality relevant to the scale of

N, aligning with the geometric bounds. The Goldbach variant requires that there exists

with

prime (ensuring

prime and

prime via the partition).

The question becomes: How many distinct values are in the set ? For example, since .

4.1. Experimental Results

We conducted a computational experiment to evaluate the size of

for every

N between 4 and

. The experiment was performed on a standard workstation (11th Gen Intel i7, 32GB RAM) using a Python 3.12 implementation with the Gmpy2 library [

4]. For each

N in the range, we compute

. We then calculate a “gap value”

defined as:

where

is the count of distinct

M-values for

N. The experiment is deterministic and yields the results summarized in

Table 1.

The results in

Table 1 show that

is consistently positive. This implies that the number of “gaps” (values of

M not in

, approximated by

) is less than

. More importantly, the minimum value of

within each successive power-of-two interval is strictly increasing. This empirical finding is the basis for the following lemma.

5. Ancillary Results

This is a key finding based on the experimental data.

Lemma 1 (Key—Computational). For and , the minimum value of in the interval is strictly less than the minimum value of in the interval .

Proof.

This lemma is an empirical observation from the computational data in

Table 1, verified for all

N in the range

. The data shows the minima of

strictly increase across dyadic intervals for

. We provide a heuristic justification for why this trend should continue.

A concise heuristic justification relies on the incremental growth of , the cardinality of the set of valid M-values (i.e., the number of distinct prime pairs with and ).

Local increment from N to

When N advances to , almost all previously realized M-values persist, but two specific candidates can newly appear:

Thus,

where

counts how many of the above cases might occur.

Growth over Larger Scales

Over ranges like , primes enter with regularity guaranteed by refinements of Bertrand’s postulate. Specifically:

Nagura’s theorem: For

, there is always a prime in

, implying at least

primes in

on average [

5].

Dusart’s refinement: For

, primes exist in intervals as short as

, yielding

primes in

[

6].

Each new Q can pair with many prior primes to realize new . With available , and new Q appearing at density , the expected influx of new pairs per n is . Conservatively, Bertrand-type results ensure at least new incorporations per n.

Over , the total new Q in number , each potentially adding up to pairs, distributed across values of n. This yields an average growth of per step. Consequently, gaps increase nearly linearly, but the logarithmic term ensures the deficit grows slower than , so trends upward.

Extension to dyadic intervals

Extending to dyadic intervals

as

, each such interval contains a power of two anchoring the empirical minima observed in

Table 1. The refined Bertrand bounds amplify with

m: new

Q in

number

, each incorporating

prior

, adding

per

n on average. Cumulatively,

for some

, with gaps

. The increase in

across

is

, outpacing the relative gap shrinkage

, ensuring the minimum

rises, consistent with the data. □

Remark 1.

This empirical pattern strongly suggests the inequality holds universally, though a rigorous analytical proof remains an open problem.

This is a main insight, derived from the data.

Corollary 1 (Computational Evidence) For all N in the range , we have . The empirical data strongly suggests this inequality holds for all .

Proof.

This is a direct consequence of the experimental data presented in

Table 1. The data shows that

for all

N tested (specifically, the minimum value in each interval is positive and increasing). By definition,

. The condition

directly implies:

Rearranging gives:

Lemma 1 shows this bound not only holds but strengthens as

N increases within our tested range. While this provides compelling evidence for the universal validity of the inequality, a rigorous analytical proof extending beyond our computational range would constitute a significant theoretical advance. □

Conjecture 2. The inequality holds for all .

6. Main Result

Theorem 3. (Conditional on Computational Bound) If the inequality holds for all , then the variant Goldbach conjecture is true: every even integer greater than or equal to 8 is the sum of two distinct prime numbers.

Our computational verification for confirms in all cases, with the bound consistently satisfied and strengthening over successive intervals.

Proof.

As established in

Section 2, the conjecture is true if and only if for every

, there exists at least one pair of distinct primes

such that

with

. This is equivalent to there existing a prime

such that

(since then

, and the geometric construction holds).

The candidate M values are for each prime , giving candidates in . The “good” M are those in , while the “bad” M (with no straddling prime pair of difference ) number fewer than if the computational bound holds.

By the pigeonhole principle, if the number of candidates

exceeds the number of bad

M, then at least one candidate

must be good, i.e.,

[

7]. Known lower bounds give

for

(this can be deduced from results in [

6]), and

for

. Thus,

assuming the bound, the strict inequality holds for

, proving the conjecture for

.

For the base cases , we verify manually (additional examples beyond are included for illustration):

(): Candidates ; . , so candidate good. Partition: . Holds, .

(): Candidates ; . , so good (). Partition: . Holds.

(): Candidates ; . , so all good. Partition: . Holds, .

(): Candidates ; . , so good (; prime). Partition: . Holds.

(): Candidates ; . , so good (; prime). Partitions: , . Holds.

(): Candidates ; . , so good (; prime). Partitions: , . Holds, .

(): Candidates ; . , so good (; prime). Partitions: , . Holds, .

(): Candidates ; . , so good (; prime). Partitions: , . Holds, .

(): Candidates ; . , so good (; prime). Partitions: , , . Holds, .

For , the conjecture holds by direct computational verification (included in our analysis up to ).

Thus, under the assumption that the computationally-observed bound extends to all N, the conjecture holds for . □

Remark 2 (Computational Verification) Direct computation confirms the theorem’s conclusion for all even integers up to .

7. Conclusions

We have presented a novel geometric perspective on a variant of the Goldbach conjecture, reformulating the additive problem as a geometric search for an integer M such that the area is a semiprime . By redefining to capture all achievable M from straddling prime pairs, we analyzed its cardinality using computational data.

Our computational analysis establishes that for all , with the gap function exhibiting a robust positive trend that strengthens across successive intervals. This provides strong empirical support for the conjecture that every even integer greater than or equal to 8 is the sum of two distinct prime numbers.

Significance and Future Work

This work makes several contributions:

Novel Geometric Framework: We establish a rigorous equivalence between Goldbach partitions and semiprime areas in nested square constructions, offering fresh geometric intuition for a classical arithmetic problem.

Computational Evidence: Extensive verification up to demonstrates the viability of our approach and reveals consistent patterns in the distribution of valid configurations.

Conditional Proof Strategy: We show that an analytical bound on would immediately yield a proof via the pigeonhole principle, reducing the problem to establishing a single inequality.

Open Problem: The central challenge is to prove analytically that for all . Our heuristic arguments based on prime distribution theory (Bertrand’s postulate refinements) suggest promising directions, but a rigorous proof remains elusive.

This work highlights how geometric reformulation combined with computational exploration can illuminate classical problems and suggest concrete paths toward resolution. The gap between computational evidence and universal proof underscores both the power and limitations of empirical methods in number theory.

Limitations and Open Questions

Scope of Computational Verification: Our empirical analysis covers , corresponding to even integers up to 32,768. While this range is substantial, it represents only the initial segment of the infinite domain where the conjecture must hold.

The Analytical Gap:

The central unresolved question is whether the computationally-observed bound can be proven analytically for all N. Our heuristic arguments invoke:

Refined versions of Bertrand’s postulate (Nagura, Dusart)

The prime number theorem and its error terms

Probabilistic models of prime pair formation

While these suggest the bound should hold, translating heuristics into rigorous proof requires overcoming significant technical obstacles.

Alternative Approaches:

Future work might pursue:

Analytic number theory methods: Using sieve theory or circle method techniques to bound from below

Expanded computation: Extending verification to or beyond to strengthen empirical confidence

Refined geometric analysis: Exploring whether the nested square framework admits tighter combinatorial bounds

Relation to Goldbach:

It is worth noting that proving our bound analytically would constitute a proof of the Goldbach variant. Conversely, any counterexample to Goldbach (for distinct primes) would necessarily produce an N violating our bound—though our computational evidence makes this increasingly implausible.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Iris, Marilin, Sonia, Yoselin, and Arelis for their support.

References

- Goldbach, C. Lettre XLIII. In Correspondance mathématique et physique de quelques célèbres géomètres du XVIIIème siècle; (in German). Fuss, P.H., Ed.; Imperial Academy of Sciences: St. Petersburg, 1843. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira e Silva, T.; Herzog, S.; Pardi, S. Empirical verification of the even Goldbach conjecture and computation of prime gaps up to 4·1018. Mathematics of Computation 2014, 83, 2033–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P. On the Connections between Goldbach Conjecture and Prime Number Theorem. Advances in Pure Mathematics 2025, 15, 412–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F. Experimental Results on Goldbach’s Conjecture. https://github.com/frankvegadelgado/goldbach, 2025. Accessed: 2025-11-11.

- Nagura, J. On The Interval Containing At Least One Prime Number. Proceedings of the Japan Academy 1952, 28, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusart, P. Autour de la fonction qui compte le nombre de nombres premiers. https://www.unilim.fr/pages_perso/pierre.dusart/Documents/T1998_01.pdf, 1998. Accessed: 2025-11-11.

- Rittaud, B.; Heeffer, A. The Pigeonhole Principle, Two Centuries before Dirichlet. The Mathematical Intelligencer 2014, 36, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).