Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The increasing dependence on online education highlights the need for scalable and efficient assessment tools. Manual grading of structured science questions is time-consuming and subjective, leading to inefficiencies and inconsistencies that compromise assessment fairness and reliability. This research addresses this challenge by developing and testing a new deep learning model for automated generative grading. It employs a hybrid Seq2Seq architecture with BERT and ResNet encoders alongside a GRU decoder to analyze both text and images within questions. The model was carefully evaluated using token-level metrics such as Accuracy, Precision, and F1-Score, along with advanced generative metrics like Corpus BLEU Score and Average BERT Similarity Score. The results reveal a notable contrast: the model achieved a low Corpus BLEU score of 4.34, indicating limited exact syntactic matches with reference answers, but excelled with an Average BERT Similarity of 0.9944, demonstrating strong semantic and contextual understanding. This key finding shows the model's capacity to comprehend the meaning and relevance of marking schemes despite varied wording. The study confirms the model's ability to process and interpret both textual and visual data to generate relevant, meaningful outputs. Overall, this research validates the concept, offering a robust architectural framework and evaluation method for new AI-powered educational tools. The findings reject the null hypothesis, indicating the model significantly improves grading accuracy through enhanced semantic understanding and scalability, providing a promising solution for educators.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Problem

1.2. Statement of the Problem

1.3. Purpose of the Study

1.4. Specific Objectives

- To examine the influence of a deep learning model on the accuracy of automated generative grading for structured science questions.

- To assess the effect of the deep learning model on the efficiency and consistency of the grading process compared to traditional manual methods.

- To develop and validate a robust deep learning framework for automated grading, using quantitative metrics such as Accuracy, Precision, F1-Score, BLEU, and BERT Similarity.

1.5. Research Questions

- How effective is a hybrid deep learning model (BERT + CNN + GRU) at generating marking schemes for structured science questions that include both textual and diagrammatic components?

- What is the correlation between AI-generated marking schemes from the hybrid model and human-made marking schemes in structured science assessments?

1.6. Hypothesis of the study

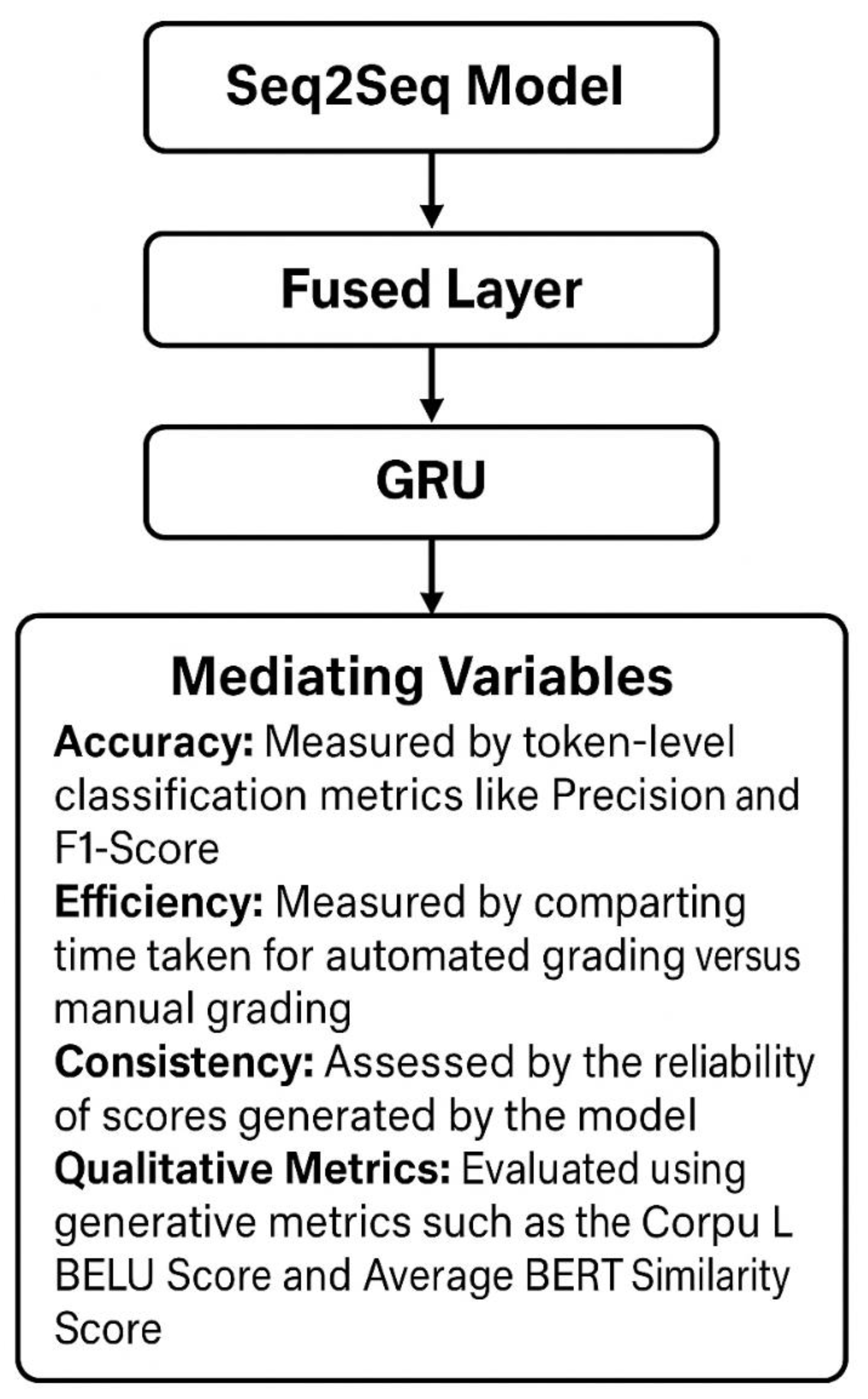

1.7. Conceptual Framework

- Accuracy: Measured by token-level classification metrics like Precision and F1-Score.

- Efficiency: Measured by comparing the time taken for automated grading versus manual grading.

- Consistency: Assessed by the reliability of scores generated by the model.

- Qualitative Metrics: Evaluated using generative metrics such as the Corpus BLEU Score and Average BERT Similarity Score.

1.8. Theoretical Framework

1.9. Importance of the Study

1.10. Scope and Limitations of the Study

2. Review of the Literature

3. Methodology

3.1. Experimental Design Approach

3.2. Dataset Collection and Preprocessing

3.2.1. Data Source Selection

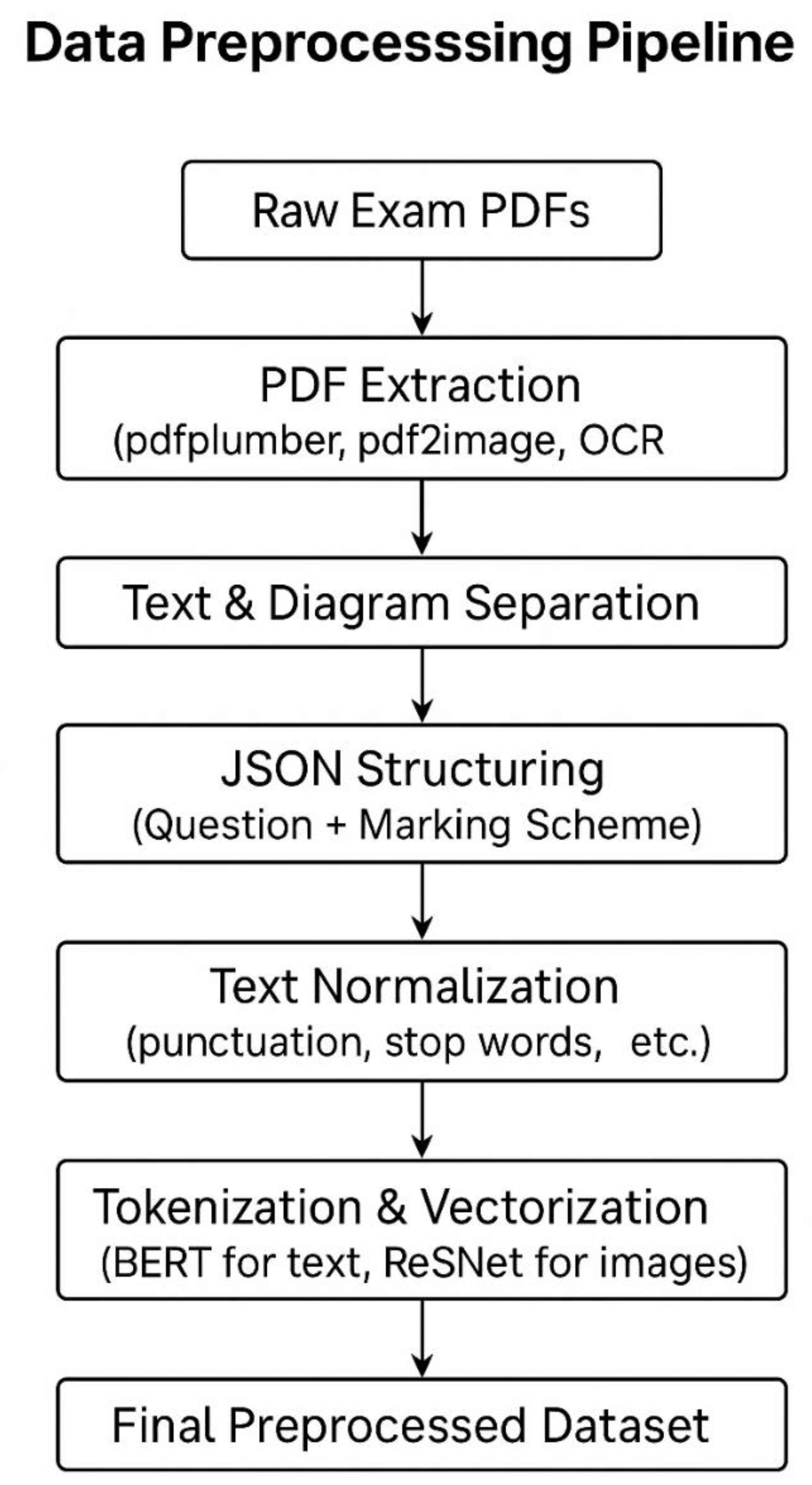

3.2.2. Preprocessing Steps

- Downloading the past papers and their marking schemes to the local storage.

- Matching the downloaded past question papers with their corresponding marking schemes. This involved using the Python programming language, importing the ‘shutil’ and ‘os’ libraries.

- Extracting and processing text and diagrams from the question papers and their marking schemes. The pdfplumber library was used to extract text, and then pdf2image and OCR (Tesseract) (Patel, 2025) were used to extract and process diagrams, as well as identify and read text within the diagrams.

- The extracted content from the question papers and the marking schemes was stored separately as JSON files, with each question or marking scheme having its question parts and any diagrams attached to it. The structure of the JSON file included the exam code title, question number, question part ID, its body, the diagram file details, including the bounding box for each dimension for each diagram, and the page number. The JSON file pairs for the Questions and their corresponding marking schemes were merged into a single JSON file that contained both question details and their corresponding marking scheme details.

- Text normalisation (Kumar, 2024), on the JSON file, was performed, it involved removing punctuation, indented spaces, stop words, and tokenization and vectorization of text and images into numerical representations using BERT and ResNet50 (Sagala & Setiawan, 2025) for text and images, respectively.

3.3. Model Selection and Training

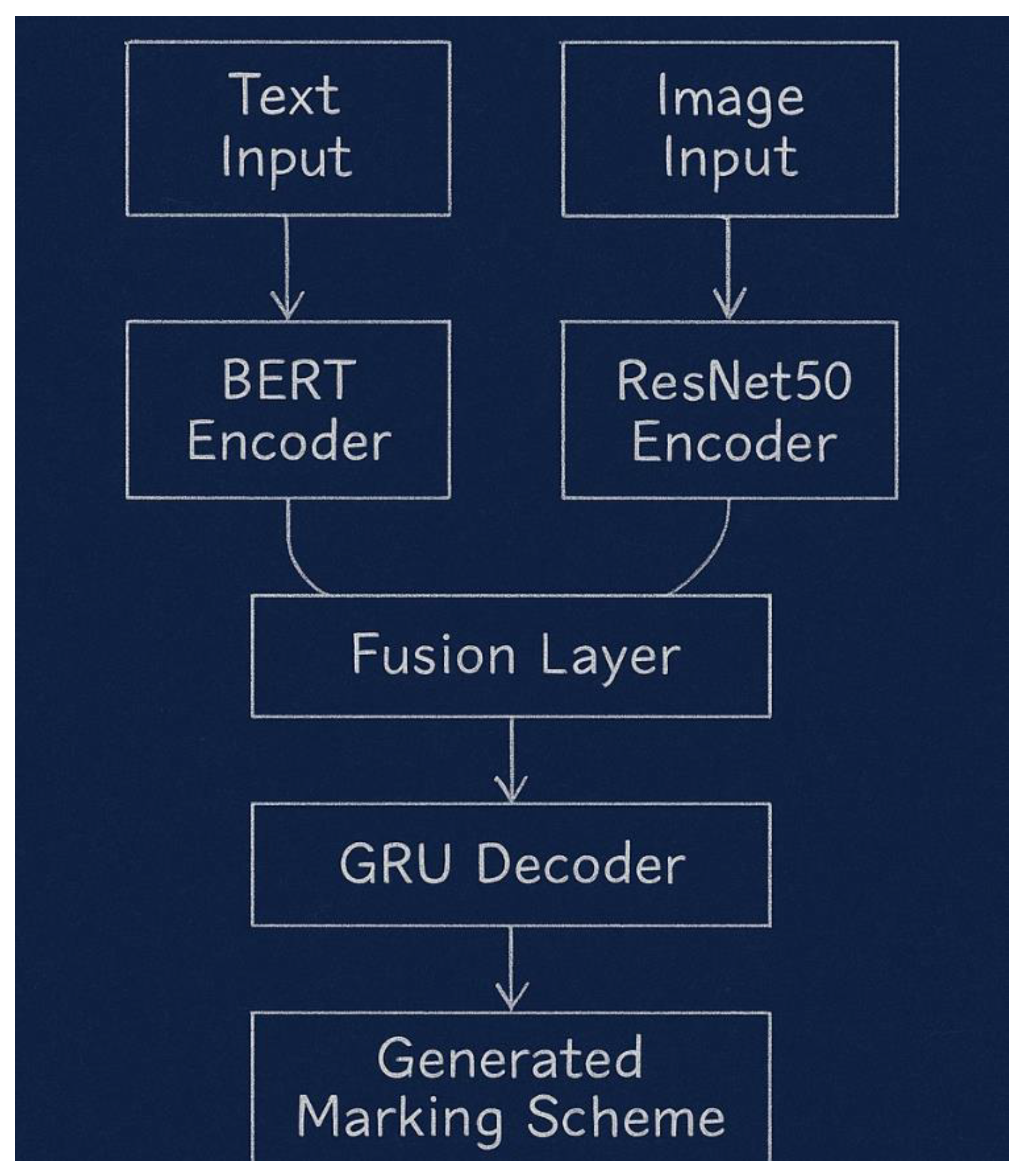

3.3.1. Model Architecture

3.3.2. Training Process

3.4. Model Evaluation

- The Corpus BLEU Score was calculated to measure the n-gram overlap between the model's generated grading schemes and the reference answers. This metric provided insight into the linguistic fluency and closeness of the generated text to the expected output. Additionally, the

- The Average BERT Similarity Score was used to evaluate the semantic similarity between the generated and reference answers, providing a more nuanced understanding of content accuracy that goes beyond simple keyword matching.

- The model's efficiency was measured by comparing the time required for automated grading versus the average time spent on manual grading.

- Consistency was evaluated by assessing the variability of the model's scores across multiple runs on the same dataset, providing a quantitative measure of its reliability.

3.5. Data Analysis and Interpretation

3.6. Development Tools & Frameworks

- The PyTorch library was used for training deep learning models, including a transformer (BERT) for semantic analysis.

- Transformers in the Hugging Face catalogue provided these pre-trained models for natural language understanding and processing, and CNN for computer vision tasks, as well as GRU for text generation.

4. Findings

4.1. Hyperparameter Optimization with Optuna

| Hyperparameter | Optimal Value |

|---|---|

| Learning Rate | 0.000571 |

| Batch Size | 4 |

| Teacher Forcing Ratio | 0.2216 |

| Number of Epochs | 7 |

| Minimized Validation Loss | 1.397 |

4.2. Final Model Performance

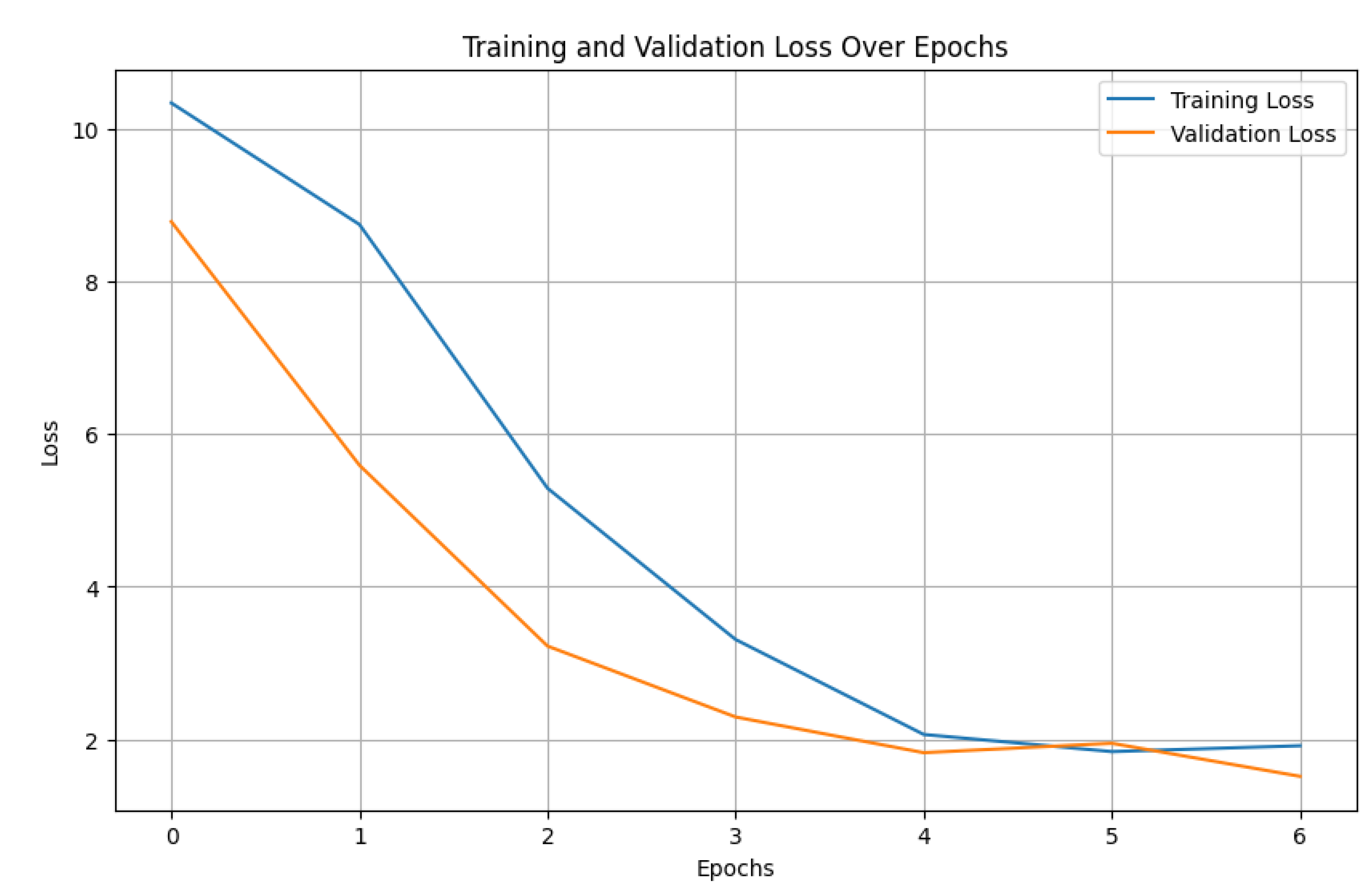

4.2.1. Training and Validation Loss

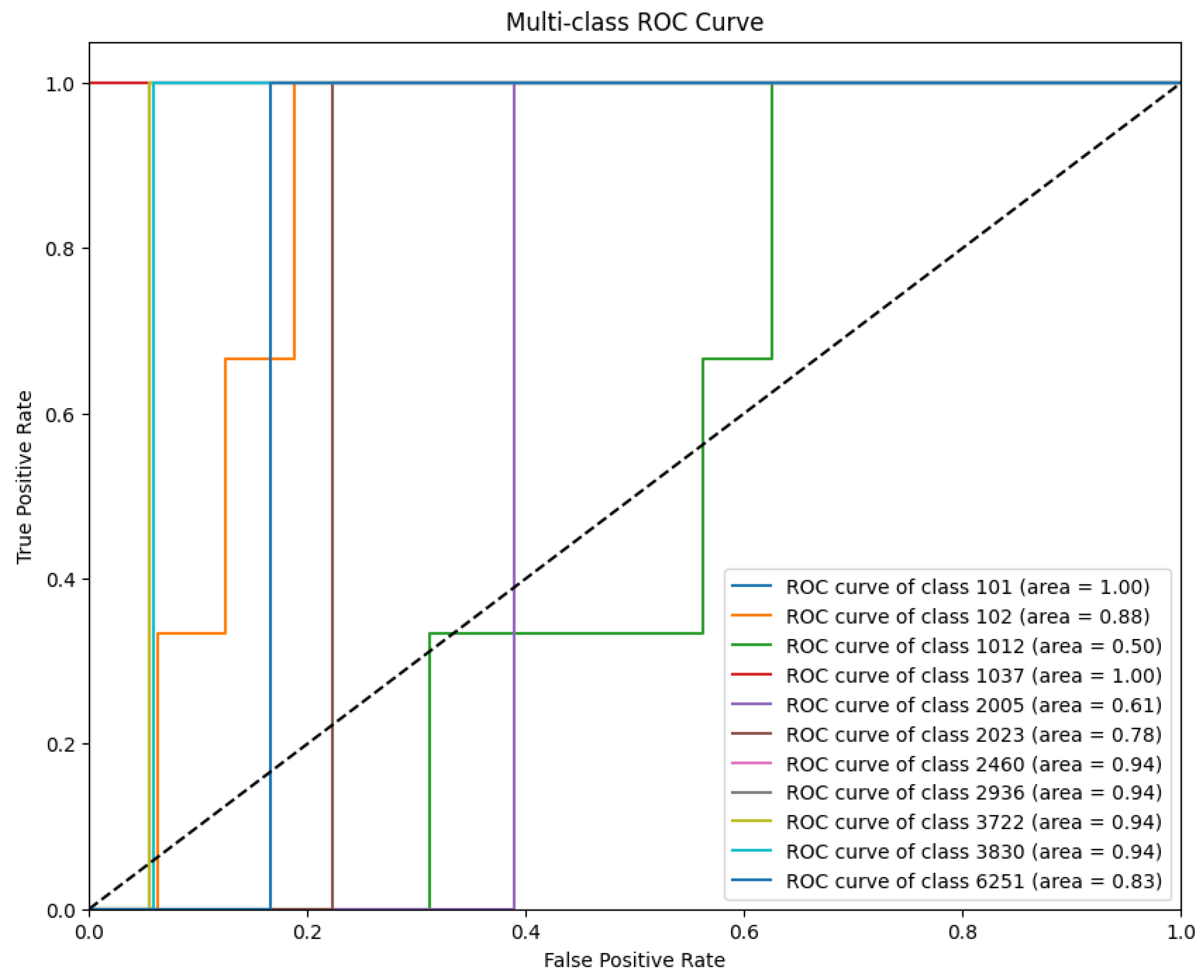

4.2.2. Token-Level Classification Metrics

| Metric | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Predictive Loss | Test Loss | 1.8451 |

| Token-Level Metrics | Accuracy | 0.2632 |

| Macro-Averaged Precision | 0.1515 | |

| Macro-Averaged F1-Score | 0.1818 | |

| Generative Quality Metrics | Corpus BLEU Score | 4.34 |

| Average BERT Similarity Score | 0.9944 |

4.2.3. Advanced Generative Metrics

4.3. Inference and Generative Capability

5. Discussion, Conclusion, and Recommendations

5.1. Discussion

5.1.1. Interpretation of Hyperparameter Optimization

5.1.2. Analysis of Quantitative Performance Metrics

5.1.3. The Dichotomy of BLEU and BERT Similarity Scores

- Understand the Multimodal Input: It correctly interprets the requirements of the question from both its textual and visual components.

- Reason about the Content: It performs the necessary reasoning to determine the correct criteria for marking.

- Generate a Semantically Correct Output: It articulates these criteria in a way that is meaningfully equivalent to the official marking scheme.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

5.2.1. Dataset Limitations

5.2.2. Model Architecture Limitations

5.2.3. Inference and Evaluation Limitations

5.3. Conclusions

5.4. Implications and Recommendations for Future Work

5.4.1. Theoretical Implications

5.4.2. Practical Implications for Education

5.4.3. Recommendations for Future Work

Appendix

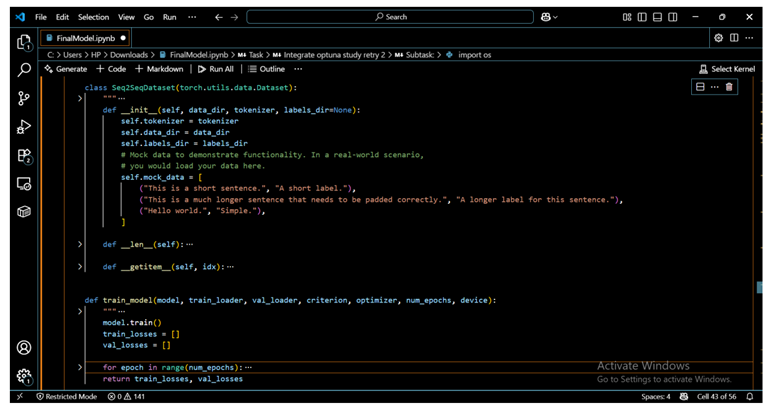

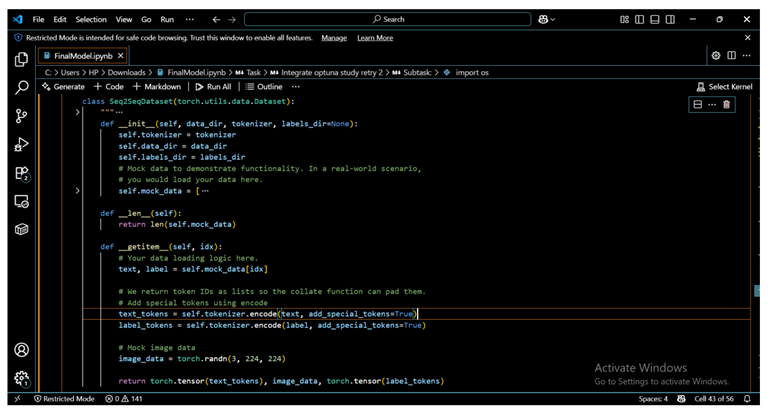

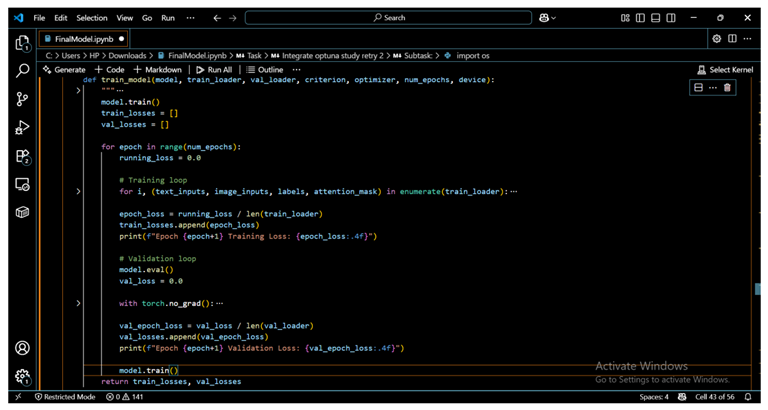

Appendix A: Core Python Source Code

A.1 Multimodal Sequence-to-Sequence Model (Seq2SeqModel)

A.2 2. Custom Dataset and Collation Function (Seq2SeqDataset, pad_sequence_custom).

A.3 3. 3. Training and Evaluation Functions.

Appendix B: Sample Data Structure

JSON

Appendix C: List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| BLEU | Bilingual Evaluation Understudy |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| RNNs | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| Seq2Seq | Sequence-to-Sequence |

References

- Abrahams, L., De Fruyt, F., & Hartsuiker, R. J. (2018). Syntactic chameleons: Are there individual differences in syntactic mimicry and its possible prosocial effects? Acta Psychologica, 191, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, J. (2024). Blooms taxonomy. Structural Optimization.

- Aqlan, F., & Nwokeji, J. (2018). Big Data ETL Implementation Approaches: A Systematic Literature Review. [CrossRef]

- Assoudi, H. (2024). Model Fine-Tuning. In H. Assoudi (Ed.), Natural Language Processing on Oracle Cloud Infrastructure: Building Transformer-Based NLP Solutions Using Oracle AI and Hugging Face (pp. 249–319). Apress. [CrossRef]

- Bai, X., & Yang, L. (2025). Research on the influencing factors of generative artificial intelligence usage intent in post-secondary education: An empirical analysis based on the AIDUA extended model. Frontiers in Psychology, 16. [CrossRef]

- Balandina, A. N., Gruzdev, B. V., Savelev, N. A., Budakyan, Y. S., Kisil, S. I., Bogdanov, A. R., & Grachev, E. A. (2024). A Transformer Architecture for Risk Analysis of Group Effects of Food Nutrients. Moscow University Physics Bulletin, 79(2), S828–S843. [CrossRef]

- Bato, B., & Pomperada, J. (2025). Automated grading system with student performance analytics. Technium: Romanian Journal of Applied Sciences and Technology, 30, 58–75. [CrossRef]

- Berge, K. L., Skar ,Gustaf B., Matre ,Synnøve, Solheim ,Randi, Evensen ,Lars S., Otnes ,Hildegunn, & and Thygesen, R. (2019). Introducing teachers to new semiotic tools for writing instruction and writing assessment: Consequences for students’ writing proficiency. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 26(1), 6–25. [CrossRef]

- Bonthu, S., Rama Sree, S., & Krishna Prasad, M. H. M. (2021). Automated Short Answer Grading Using Deep Learning: A Survey. In A. Holzinger, P. Kieseberg, A. M. Tjoa, & E. Weippl (Eds.), Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction (pp. 61–78). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Borisovsky, P., Dolgui, A., & Eremeev, A. (2009). Genetic algorithms for a supply management problem: MIP-recombination vs greedy decoder. European Journal of Operational Research, 195(3), 770–779. [CrossRef]

- Brindha, R., Pongiannan, R. K., Bharath, A., & Sanjeevi, V. K. S. M. (2025). Introduction to Multimodal Generative AI. In A. Singh & K. K. Singh (Eds.), Multimodal Generative AI (pp. 1–36). Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Brookhart, S. M. (2011). Educational Assessment Knowledge and Skills for Teachers. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 30(1), 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Burrows, S., Gurevych, I., & Stein, B. (2015). The Eras and Trends of Automatic Short Answer Grading. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 25(1), 60–117. [CrossRef]

- Camus, L., & Filighera, A. (2020). Investigating Transformers for Automatic Short Answer Grading. In I. I. Bittencourt, M. Cukurova, K. Muldner, R. Luckin, & E. Millán (Eds.), Artificial Intelligence in Education (pp. 43–48). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Carbonel, H., Belardi, A., Ross, J., & Jullien, J.-M. (2025). Integrity and Motivation in Remote Assessment. Online Learning, 29. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Wang, T., Zhou, J., Song, Z., Gao, X., & Zhang, X. (2025). Evaluating and mitigating bias in AI-based medical text generation. Nature Computational Science, 5(5), 388–396. [CrossRef]

- Davoodijam, E., & Alambardar Meybodi, M. (2024). Evaluation metrics on text summarization: Comprehensive survey. Knowledge and Information Systems, 66(12), 7717–7738. [CrossRef]

- Daw, M. (2022). (PDF) Mark distribution is affected by the type of assignment but not by features of the marking scheme in a biomedical sciences department of a UK university. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364643041_Mark_distribution_is_affected_by_the_type_of_assignment_but_not_by_features_of_the_marking_scheme_in_a_biomedical_sciences_department_of_a_UK_university.

- Dutta, N., Sobel, R. S., Stivers, A., & Lienhard, T. (2025). Opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship: Do linguistic structures matter? Small Business Economics, 64(4), 1981–2012. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, C. (2019). A Study of Selected-Response Type Assessment (MCQ) and Essay Type Assessment Methods for Engineering Students. Journal of Engineering Education Transformations, 91–95. https://journaleet.in/index.php/jeet/article/view/1566.

- Dzikovska, M., Nielsen, R., Brew, C., Leacock, C., Giampiccolo, D., Bentivogli, L., Clark, P., Dagan, I., & Dang, H. T. (2013). SemEval-2013 Task 7: The Joint Student Response Analysis and 8th Recognizing Textual Entailment Challenge. In S. Manandhar & D. Yuret (Eds.), Second Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics (*SEM), Volume 2: Proceedings of the Seventh International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval 2013) (pp. 263–274). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/S13-2045/.

- Ekakristi, A. S., Wicaksono, A. F., & Mahendra, R. (2025). Intermediate-task transfer learning for Indonesian NLP tasks. Natural Language Processing Journal, 12, 100161. [CrossRef]

- Ekwaro-Osire, H., Ponugupati, S. L., Al Noman, A., Bode, D., & Thoben, K.-D. (2025). Data augmentation for numerical data from manufacturing processes: An overview of techniques and assessment of when which techniques work. Industrial Artificial Intelligence, 3(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Flandoli, F., & Rehmeier, M. (2024). Remarks on Regularization by Noise, Convex Integration and Spontaneous Stochasticity. Milan Journal of Mathematics, 92(2), 349–370. [CrossRef]

- Geetha, S., Elakiya, E., Kanmani, R. S., & Das, M. K. (2025). High performance fake review detection using pretrained DeBERTa optimized with Monarch Butterfly paradigm. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 7445. [CrossRef]

- George, A. S., Baskar, D., & Balaji Srikaanth, P. (2024). The Erosion of Cognitive Skills in the Technological Age: How Reliance on Technology Impacts Critical Thinking, Problem-Solving, and Creativity. 02, 147–163. [CrossRef]

- Gundu, T. (2024, April 10). (PDF) Strategies for e-Assessments in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389194917_Strategies_for_e-Assessments_in_the_Era_of_Generative_Artificial_Intelligence#fullTextFileContent.

- HACHE MARLIERE, M. A., DESPRADEL PEREZ, L. C., BIAVATI, L., & GULANI, P. (2024). BEYOND ROTE MEMORIZATION: TEACHING MECHANICAL VENTILATION THROUGH WAVEFORM ANALYSIS. CHEST 2024 Annual Meeting Abstracts, 166(4, Supplement), A3863. [CrossRef]

- Hardison, H. (2022). How Teachers Spend Their Time: A Breakdown. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/how-teachers-spend-their-time-a-breakdown/2022/04.

- Hosseini, S. M., Ebrahimi, A., Mosavi, M. R., & Shahhoseini, H. Sh. (2025). A novel hybrid CNN-CBAM-GRU method for intrusion detection in modern networks. Results in Engineering, 28, 107103. [CrossRef]

- Huffcutt, A. I., & Murphy, S. A. (2023). Structured interviews: Moving beyond mean validity…. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(3), 344–348. [CrossRef]

- IGCSE. (2025). Cambridge IGCSE - 14-16 Year Olds International Qualification. https://www.cambridgeinternational.org/programmes-and-qualifications/cambridge-upper-secondary/cambridge-igcse/.

- Imran, M., & Almusharraf, N. (2024). Google Gemini as a next generation AI educational tool: A review of emerging educational technology. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), 22. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A., Singh, A., & Doherey, A. (2025). Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease using XGBoost with OPTUNA. SN Computer Science, 6(5), 421. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., & He, Y. (2025). Construction and Evaluation of Context Aware Machine Translation System. Procedia Computer Science, 261, 529–537. [CrossRef]

- Kalaš, F. (2025). Evaluation of Artificial Intelligence Translation. In V. Kučiš & N. K. Vid (Eds.), Dynamics of Translation Studies / Potenziale der Translationswissenschaft: Digitization, Training, and Evaluation / Digitalisierung, Ausbildung und Qualitätssicherung (pp. 13–25). Frank & Timme GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Kampen, M. (2024, July 23). 6 Types of Assessment (and How to Use Them). https://www.prodigygame.com/main-en/blog/types-of-assessment/.

- Kang & Atul. (2024, January 20). BLEU Score – Bilingual Evaluation Understudy. TheAILearner. https://theailearner.com/2024/01/20/bleu-score-bilingual-evaluation-understudy/.

- Kara, S. (2025). Investigation of the Reflections of Prospective Science Teachers Preferred Assessment and Evaluation Approaches on Lesson Plans. Ahmet Keleşoğlu Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. (2024). Text Normalization (pp. 133–145). [CrossRef]

- Ławryńczuk, M., & Zarzycki, K. (2025). LSTM and GRU type recurrent neural networks in model predictive control: A Review. Neurocomputing, 632, 129712. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y., Yu, T., & Lin, Z. (2025). FTN-ResNet50: Flexible transformer network model with ResNet50 for road crack detection. Evolving Systems, 16(2), 51. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Zheng, Y., Du, Z., Ding, M., Qian, Y., Yang, Z., & Tang, J. (2024). GPT understands, too. AI Open, 5, 208–215. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Ott, M., Goyal, N., Du, J., Joshi, M., Chen, D., Levy, O., Lewis, M., Zettlemoyer, L., & Stoyanov, V. (2019). RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach (No. arXiv:1907.11692). arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Dong, F., Liu, C., Deng, X., Yang, T., Zhao, Y., Li, J., Cui, B., & Zhang, G. (2024). WavingSketch: An unbiased and generic sketch for finding top-k items in data streams. The VLDB Journal, 33(5), 1697–1722. [CrossRef]

- Luo, D., Liu, M., Yu, R., Liu, Y., Jiang, W., Fan, Q., Kuang, N., Gao, Q., Yin, T., & Zheng, Z. (2025). Evaluating the performance of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o in the Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 14119. [CrossRef]

- Mohler, M., Bunescu, R., & Mihalcea, R. (2011). Learning to Grade Short Answer Questions using Semantic Similarity Measures and Dependency Graph Alignments. In D. Lin, Y. Matsumoto, & R. Mihalcea (Eds.), Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (pp. 752–762). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/P11-1076/.

- Mueller, J., & Thyagarajan, A. (2016). Siamese Recurrent Architectures for Learning Sentence Similarity. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 30(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Muraina, I., Adesanya, O., & Abam, S. (2023). DATA ANALYTICS EVALUATION METRICS ESSENTIALS: MEASURING MODEL PERFORMANCE IN CLASSIFICATION AND REGRESSION.

- Nariman, G. S., & Hamarashid, H. K. (2025). Communication overhead reduction in federated learning: A review. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics, 19(2), 185–216. [CrossRef]

- Nasri, M., & Ramezani, M. (2025). Web analytics of Iranian public universities based on technical features extracted from web analytics tools.

- Otten, N. V. (2023, October 12). Teacher Forcing In Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): An Advanced Concept Made Simple. Spot Intelligence. https://spotintelligence.com/2023/10/12/teacher-forcing-in-recurrent-neural-networks-rnns-an-advanced-concept-made-simple/.

- Otten, N. V. (2024, February 19). Learning Rate In Machine Learning And Deep Learning Made Simple. Spot Intelligence. https://spotintelligence.com/2024/02/19/learning-rate-machine-learning/.

- Papageorgiou, V. E. (2025). Boosting epidemic forecasting performance with enhanced RNN-type models. Operational Research, 25(3), 77. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D. (2025). Comparing Traditional OCR with Generative AI-Assisted OCR: Advancements and Applications. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 14, 347–351. [CrossRef]

- Peng, W., Wang, Y., & Wu, M. (2024). Enhanced matrix inference with Seq2seq models via diagonal sorting. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 883. [CrossRef]

- Phellas, C. N., Bloch, A., & Seale, C. (n.d.). STRUCTURED METHODS: INTERVIEWS, QUESTIONNAIRES AND OBSERVATION. DOING RESEARCH.

- Powers, A. (2025). Moral overfitting. Philosophical Studies. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, O., & Kumar, R. (2024). A unified generalization enabled ML architecture for manipulated multi-modal social media. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 83(8), 22749–22771. [CrossRef]

- Rabonato, R., & Berton, L. (2024). A systematic review of fairness in machine learning. AI and Ethics, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J., Sadaf, A., & Ertmer, P. (2012). Relationship between question prompts and critical thinking in online discussions. In Educational Communities of Inquiry: Theoretical Framework, Research and Practice (pp. 197–222). [CrossRef]

- Rincon-Flores, E. G., Castano, L., Guerrero Solis, S. L., Olmos Lopez, O., Rodríguez Hernández, C. F., Castillo Lara, L. A., & Aldape Valdés, L. P. (2024). Improving the learning-teaching process through adaptive learning strategy. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), 27. [CrossRef]

- Sagala, L., & Setiawan, A. (2025). Classification of Diabetic Retinopathy Using ResNet50. JAREE (Journal on Advanced Research in Electrical Engineering), 9. [CrossRef]

- Setthawong, P., & Setthawong, R. (2022). Mproved Grading Approval Process with Rule Based Grade Distribution System (No. 11). ICIC International 学会. [CrossRef]

- Shen, G., Tan, Q., Zhang, H., Zeng, P., & Xu, J. (2018). Deep Learning with Gated Recurrent Unit Networks for Financial Sequence Predictions. Procedia Computer Science, 131, 895–903. [CrossRef]

- Shi, C., Liu, W., Meng, J., Li, Z., & Liu, J. (2026). Global Cross Attention Transformer for Image Super-Resolution. In L. Jin & L. Wang (Eds.), Advances in Neural Networks – ISNN 2025 (pp. 161–171). Springer Nature Singapore.

- Shih, S.-Y., Sun, F.-K., & Lee, H. (2019). Temporal pattern attention for multivariate time series forecasting. Machine Learning, 108(8), 1421–1441. [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, M., Shibata, K., & Wagatsuma, H. (2024). Conditional checkpoint selection strategy based on sentence structures for text to triple translation using BiLSTM encoder–decoder model. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics. [CrossRef]

- Shunmuga Priya, M. C., Karthika Renuka, D., & Ashok Kumar, L. (2025). Robust Multi-Dialect End-to-End ASR Model Jointly with Beam Search Threshold Pruning and LLM. SN Computer Science, 6(4), 323. [CrossRef]

- Stokking, K., Schaaf, M., Jaspers, J., & Erkens, G. (2004). Teachers’ assessment of students’ research skills. British Educational Research Journal, 30(1), 93–116. [CrossRef]

- sundaresh, angu. (2025, February 1). Top-k and Top-p (Nucleus) Sampling: Understanding the Differences. Medium. https://medium.com/@kangusundaresh/top-k-and-top-p-nucleus-sampling-understanding-the-differences-1aa06eecdc48.

- Suto, I., Williamson, J., Ireland, J., & Macinska, S. (2021). On reducing errors in assessment instruments. Research Papers in Education, 38, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- The F.A.C.T.S. About Grading. (n.d.). CENTER FOR THE PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION OF TEACHERS. Retrieved September 21, 2025, from http://cpet.tc.columbia.edu/8/post/2023/02/the-facts-about-grading.html.

- Tomas, C., Borg, M., & McNeil, J. (2015). E-assessment: Institutional development strategies and the assessment life cycle. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), 588–596. [CrossRef]

- Veronica Romero, Alejandro Hector Toselli, & Enrique Vidal. (2012). Multimodal Interactive Handwritten Text Transcription. World Scientific Publishing Company. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uel/detail.action?docID=1019616.

- Wakjira, Y., Kurukkal, N. S., & Lemu, H. G. (2024). Reverse engineering in medical application: Literature review, proof of concept and future perspectives. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 23621. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Wu, F., Liu, X., Cao, J., Ma, M., & Qu, Z. (2025). Relationship extraction between entities with long distance dependencies and noise based on semantic and syntactic features. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 15750. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F., & Fink, G. A. (2024). Self-training for handwritten word recognition and retrieval. International Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition (IJDAR), 27(3), 225–244. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-X., Du, K., Wang, X.-J., & Min, F. (2024). Misclassification-guided loss under the weighted cross-entropy loss framework. Knowledge and Information Systems, 66(8), 4685–4720. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z., Ning, X., & Duritan, M. J. M. (2025). BERT-SVM: A hybrid BERT and SVM method for semantic similarity matching evaluation of paired short texts in English teaching. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 126, 231–246. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D., Chen, W., Peng, W., Zhang, C., Xu, T., Zhao, X., Wu, X., Zheng, Y., Wang, Y., & Chen, E. (2024). Large language models for generative information extraction: A survey. Frontiers of Computer Science, 18(6), 186357. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Li, Y., Ma, L., Li, C., Dong, Y., Yuan, X., & Liu, H. (2025). Autonomous embodied navigation task generation from natural language dialogues. Science China Information Sciences, 68(5), 150208. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q., Wang, L., Liu, H., & Liu, N. (2022). LayoutLM-Critic: Multimodal Language Model for Text Error Correction of Optical Character Recognition. In S. Yang & H. Lu (Eds.), Artificial Intelligence and Robotics (pp. 136–146). Springer Nature Singapore.

- Yang, K., Zhang, W., Li, P., Liang, J., Peng, T., Chen, J., Li, L., Hu, X., & Liu, J. (2025). ViT-BF: vision transformer with border-aware features for visual tracking. The Visual Computer, 41(9), 6631–6644. [CrossRef]

- Ye, J., Dobson, S., & McKeever, S. (2012). Situation identification techniques in pervasive computing: A review. Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 8(1), 36–66. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q., Proctor, C. P., Ryu, E., & Silverman, R. D. (2024). Relationships between linguistic knowledge, linguistic awareness, and argumentative writing among upper elementary bilingual students. Reading and Writing. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X., Long, H., Gou, F., & Wu, J. (2024). A semantic fidelity interpretable-assisted decision model for lung nodule classification. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 19(4), 625–633. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Yu, D., Aziz, K., Su, F., Zhang, Q., Li, F., & Ji, D. (2024). Generative Sentiment Analysis via Latent Category Distribution and Constrained Decoding. In M. Wand, K. Malinovská, J. Schmidhuber, & I. V. Tetko (Eds.), Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning – ICANN 2024 (pp. 209–223). Springer Nature Switzerland.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).