1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed significant challenges for global healthcare systems, placing a particularly heavy burden on vulnerable populations. Cancer patients, whether undergoing active treatment or in remission, represent a high-risk group for severe outcomes from COVID-19 due to a combination of factors, including immune suppression, cancer-related inflammation, and treatment-related toxicities [

1]. Emerging evidence has underscored the heightened risk of infection, hospitalization, and mortality in this population [

2].

Cancer survivors face distinct risks associated with COVID-19. A population-based study from Reggio Emilia, Northern Italy conducted by our group [

3], highlighted the higher cumulative mortality of COVID-19 among cancer survivors compared to the general population. Similarly, Johannesen et al. [

4] conducted a population-based study in Norway, identifying specific risk factors that predispose cancer patients to severe outcomes from COVID-19. Their findings underscored the role of advanced age, comorbidities, and certain cancer types, such as lung cancer and hematologic malignancies, as significant predictors of adverse outcomes.

The risk of adverse COVID-19 outcomes in cancer patients is further modulated by vaccination status, the presence of comorbidities, and the emergence of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants. Studies have demonstrated the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination in reducing the severity of disease and mortality rates across various populations [

5]. However, vaccine responses in cancer patients, particularly those undergoing immunosuppressive therapies, remain suboptimal, raising concerns about their level of protection against the virus [

6].

Patients with cancer who received anticancer treatment within three months before a COVID-19 diagnosis experienced significantly worse outcomes compared to patients without cancer. These outcomes included a higher risk of mortality, intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and hospitalization. However, patients with cancer who had no recent treatment exhibited outcomes similar to or better than the general population, indicating heterogeneity within the cancer patient population. [

7].

Reinfections have emerged as a growing concern, especially with the appearance of immune-evasive variants like Omicron. We [

8] observed that prior infection provided strong protection against reinfection in the pre-Omicron period, but this protection diminished significantly with the emergence of the Omicron BA.1 variant. Our findings showed that hybrid immunity, generated through vaccination and natural infection, offered substantially higher protection against reinfections compared to vaccination or prior infection alone. Furthermore, Omicron BA.1 reinfections were associated with reduced severity compared to primary infections, underscoring the evolving dynamics of reinfection risks in the context of new variants.

Emilia-Romagna, one of the earliest and most severely impacted regions during the pandemic, offers a unique population for assessing these risks. The region's high COVID-19 burden and extensive vaccination campaigns offer valuable insights into the role of vaccines in mitigating risks among cancer patients and survivors. Furthermore, the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants with increased transmissibility and immune escape potential, such as the Delta and Omicron variants, has introduced additional complexities in understanding infection dynamics and vaccine efficacy in this subgroup [9, 10].

Additionally, cancer patients often present with comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, or chronic pulmonary conditions, which independently contribute to worse COVID-19 outcomes [

11]. The interplay between cancer, comorbidities, and COVID-19 creates a multifaceted risk landscape that necessitates population-based studies to disentangle the relative contributions of these factors.

Aim

This study aims to evaluate the risks of COVID-19 infection and severe disease in cancer patients in northern Italy, examining the role of vaccination status, circulating virus variants, comorbidities, and phase of cancer disease, compared with the general population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This population-based cohort study included all residents of the province of Reggio Emilia, Northern Italy, who were alive on 20 February 2020. The province has approximately 538,000 inhabitants. Through linkage with the Reggio Emilia Cancer Registry, individuals were classified according to whether they had a prior diagnosis of cancer between 1996 and 2021. The cohort was followed from 20 February 2020 to 30 September 2022 to identify SARS-CoV-2 infections, reinfections, and COVID-19–related outcomes. Demographic information, including residency status, age, and sex, was retrieved from the Population Registry of the Local Health Authority of Reggio Emilia. The study relied entirely on routinely collected data within institutional surveillance systems.

2.2. Data Sources

Data were obtained through record linkage of several administrative and clinical databases using the unique personal fiscal identification code. The Reggio Emilia Cancer Registry provided information on all incident malignant tumors diagnosed since 1996, including the date of diagnosis and tumor characteristics, classified according to international rules for multiple primary cancers. The registry operates with population-based completeness and standardized quality control procedures. Detailed methods used for the construction and validation of the cancer cohort are available in Mangone et al. [

3].

The COVID-19 Surveillance Registry, coordinated by the Italian National Institute of Health, included all microbiologically confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections detected in the province between February 2020 and September 2022. The same infrastructure was used to identify reinfections, defined as new positive tests occurring more than 90 days after a previous infection. The procedures for data collection, record linkage, and the definitions of infections and reinfections have been described in detail by Vicentini et al. [

8].

The Vaccination Registry provided information on the date and type of each COVID-19 vaccine dose administered since the beginning of the national vaccination campaign in December 2020. The integration of these registries formed a comprehensive population-based surveillance system for infection, reinfection, and vaccination in Reggio Emilia, following the methodology described by Vicentini et al. [

8].

Comorbidities, hospitalizations, and deaths were retrieved from hospital discharge records, the diabetes registry, and the mortality database of the Local Health Authority, and summarized using the Charlson Comorbidity Index. During the study period, testing policies in Italy evolved from the exclusive use of RT-PCR assays to include third-generation antigen tests and, later, self-administered rapid tests that could be uploaded to an online platform for official confirmation.

2.3. Exposure Definition

The exposure was a diagnosis of cancer, considered a time-dependent variable. Cancer patients were classified as exposed starting from the date of cancer diagnosis, while individuals without cancer contributed person-time to the unexposed group until a cancer diagnosis occurred, if ever. Cancer patients were further categorized according to time since diagnosis, which served as a proxy for disease phase and treatment status.

Those diagnosed less than two years earlier, who have the highest probability of being in the active therapy phase or in early follow-up.

Those diagnosed between two and five years earlier, who are patients probably still under oncologic surveillance but receiving no treatment or low-intensity treatments.

Patients diagnosed more than five years before, who are cancer survivors with the highest probability of being cured.

This time-dependent variable was used to evaluate of how cancer status influenced infection and severity risks throughout the observation period.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was a laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection recorded in the COVID-19 Surveillance Registry. Reinfections were defined as new positive tests occurring more than 90 days after the first infection, in accordance with national and European guidelines. Secondary outcome was severe COVID-19, given the infection, defined as hospitalization within 28 days or death within 90 days following diagnosis.

2.5. Follow-Up

Follow-up began on 20 February 2020 and ended at the first occurrence of infection, death, or 30 September 2022. For reinfections, follow-up started 90 days after the first positive test and continued until reinfection, death, or the end of the study period. Hospitalizations were attributed to COVID-19 if they occurred from three days before up to 28 days after diagnosis, while deaths were considered COVID-19–related if they occurred within 90 days and met the official criteria for COVID-19 as the underlying cause of death. COVID-19-related hospitalisations were included if occurred up to 28 October 2022, while COVID-19-related deaths up to 31 December2022. Analyses were divided into two periods: the pre-Omicron period (ending on 20 December 2021) and the Omicron period (beginning on 1 January 2022), excluding the transitional days between these dates. Covariates included sex, age, vaccination history, and comorbidities as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index. Age, vaccination, and prior infection were treated as time-dependent variables, updated daily during follow-up. All other covariates were assessed at baseline, corresponding to 1 January 2020.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed to summarize the baseline characteristics of the study cohort, including sex, age, vaccination status, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), as well as the occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 infections over time, expressed in person-days. For the cancer population, SARS-CoV-2 infections were also reported according to the number of years since diagnosis (<2, 2-5, and >5 years).

Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR), with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), for SARS-CoV-2 infection for the population with cancer, adjusting for sex, age, CCI, and vaccination history, using calendar time as time axis. Hazard ratios, with 95% CIs, for SARS-CoV-2 infection were also estimated by age group (0–34, 35–64, 65–79, and ≥80 years), immunisation status, and years since cancer diagnosis.

To assess the risk of severe disease or death, given the SARS-CoV-2 infecion, multivariable logistic regression models were applied to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for individuals with cancer compared with those without cancer, adjusting for age, sex, vaccination history, and CCI. Stratified analyses by age group (0–34, 35–64, 65–79, and ≥80 years), immunisation status, and years since cancer diagnosis are reported.

Infections occurring before August 31, 2020, were excluded from the analysis on disease severity since most cases of COVID-19 during the first wave were diagnosed within hospital settings in people with moderate-to-severe symptoms, resulting in a strong underestimation of mild and asymptomatic cases in the denominator.

All analyses were stratified by the pre-Omicron and Omicron pandemic periods.

STATA v. 18.0 was used for all analyses (StataCorp LLC).

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

The study included 538,516 residents of the Reggio Emilia province, among whom 33,307 (6.2%) had a cancer diagnosis between 1996 and 2021. As shown in

Table 1, cancer patients accounted for 9,135 SARS-CoV-2 infections compared with 181,713 infections among individuals without cancer. The majority of infections occurred during the Omicron phase (January–September 2022). During the pre-Omicron phase (February 2020–December 2021), there were 2,591 infections among cancer patients compared with 52,315 among non-cancer individuals. During the Omicron phase, infections increased substantially in both groups (6,544 vs. 129,398, respectively), consistent with greater viral transmissibility and new testing modalities like self-tests and antigen swabs.

Cancer patients were predominantly female (54%) and aged ≥ 65 years (64%), reflecting the demographic structure of the cancer survivor population. They also showed a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), despite cancer was not included in the computation of the CCI score for this study. (

Suppl Table S1)

As reported in

Table 2, the hazard ratio (HR) for SARS-CoV-2 infection was 1.00 (95% CI 0.96–1.05) during the pre-Omicron period and 1.08 (95% CI 1.05–1.11) during the Omicron period. Infection risk was slightly higher among cancer patients with a diignosis in theprevious two years (pre-Omicron HR 1.37, 95% CI 1.25–1.50; Omicron HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.28–1.44), while those with a diagnosis than five years earlier had risks comparable to the general population.

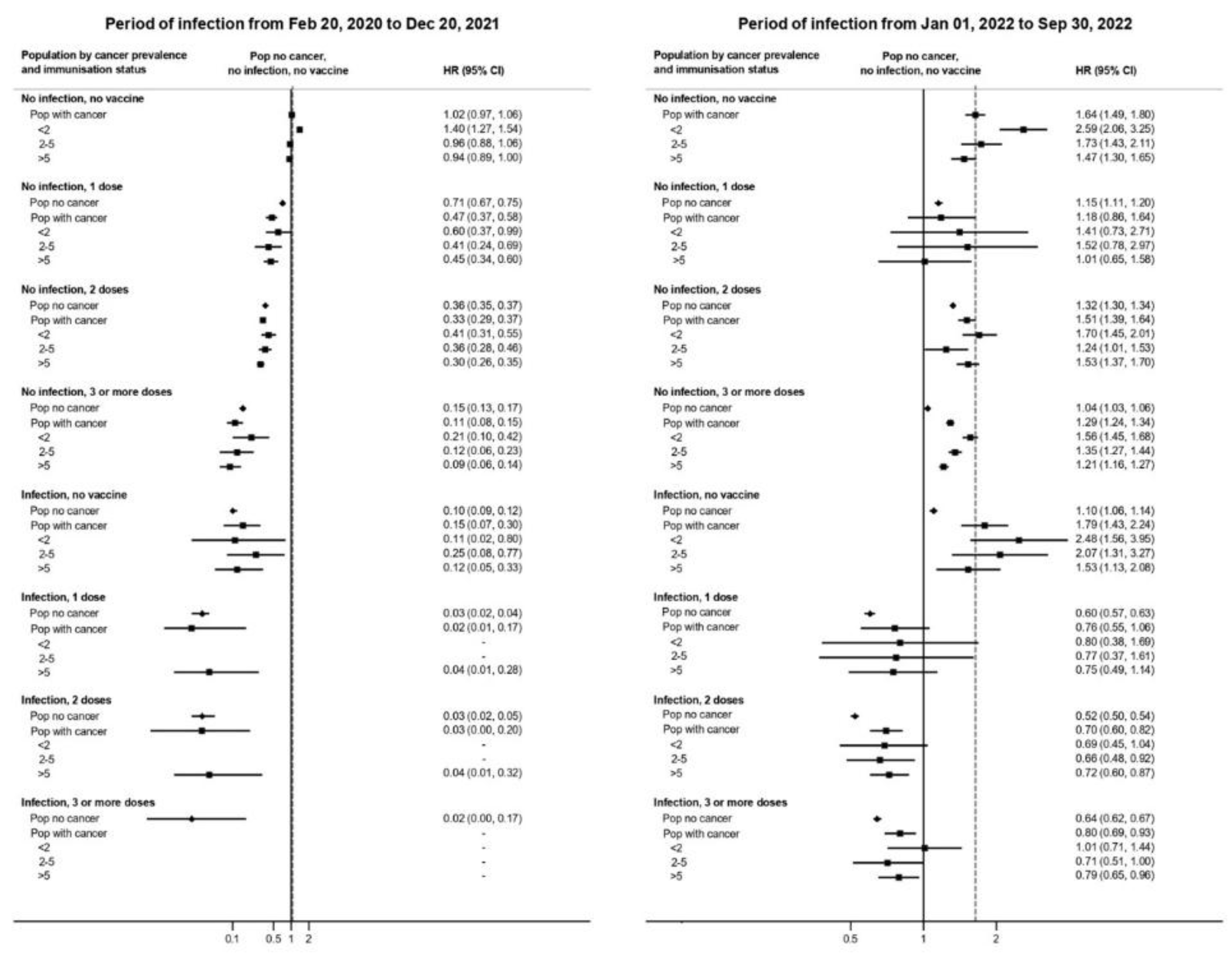

As illustrated in

Figure 1and

Suppl Table S2, vaccination strongly reduced infection risk in both cancer and non-cancer groups. In the pre-Omicron phase, individuals who received three vaccine doses had a 92% risk reduction (HR 0.08, 95% CI 0.05–0.12), while prior infection conferred an 80% reduction (HR 0.20, 95% CI 0.10–0.31). The strongest protection was observed among individuals with hybrid immunity (prior infection + two vaccine doses), who exhibited a 97% risk reduction (HR 0.03, 95% CI 0.00–0.21).

Table 3 shows that cancer patients had greater odds of hospitalization or death compared with the general population, once infected by SARS-CoV-2. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) for severe outcomes was 1.33 (95% CI 1.20–1.48) in the pre-Omicron period and 1.67 (95% CI 1.48–1.90) during Omicron. The excess risk was most pronounced in patients diagnosed < 2 years prior (OR 1.94 pre-Omicron; 3.38 Omicron), while those with diagnosis more than 5 years earlier exhibited smaller excesses (OR 1.19 and 1.37, respectively).

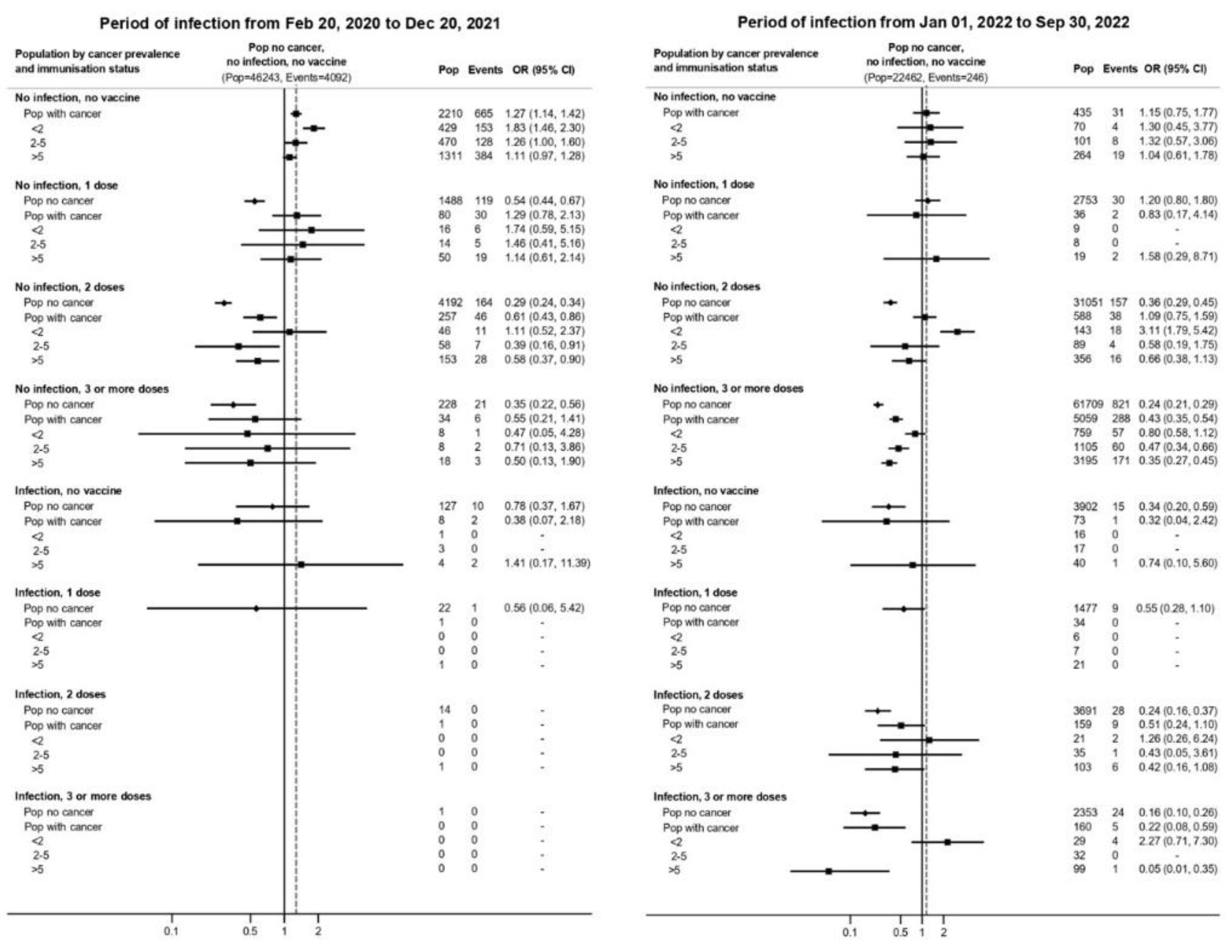

In the pre-Omicron period, vaccination conferred strong protection against severe disease and death in both populations (

Figure 2 and

Suppl Table S3). Among patients who received three or more doses, the odds of hospitalization or death were 60–80% lower than among unvaccinated individuals (ORs ranging from 0.2 to 0.4).

Overall, the absolute risk of severe COVID-19 declined sharply after December 2021, reflecting the lower virulence of circulating variants and extensive vaccine coverage.

Although the Omicron period was associated with partial immune escape, with reduced or null protection vs. infection, vaccine effectiveness against severe outcomes remained substantial, similarly in the general population and in cancer patients. The combination of vaccination and prior infection conferred the highest level of protection, particularly during the Omicron period.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

In this population-based study from northern Italy, cancer patients showed a modest excess risk of infection and a persistently higher risk of severe outcomes compared to the general population. The increase in risk is particularly appreciable during the first two years after diagnosis. The excess of risk compared to the general population decreases with increasing age and with time since diagnosis.

The protective role of vaccination was strikingly consistent across cancer and non-cancer groups. With a strong protection of 2 doses in the pre-omicron period for all, while in the omicron period the protection of the three doses schedule wained and only a mix of natural and vaccine immunization was protective vs. infection. On the other hand, vaccination with three doses gave protection vs. severe disease also in the Omicron period.

Despite a similar protection, some differences between cancer and general population were appreciable. Vaccine efficacy was always lower in in people with a recent cancer diagnosis, i.e. those more likely in the treatment phase. On the contrary, cancer patients who received the diagnosis more than 5 years earlier had even a larger protection in the omicron period than the general population, suggesting that, in this group, vaccination was probably associated with protective behaviours that further reduced the protection against infections.

4.2. Comparison with Previous Literature

Our findings are consistent with the multicenter cohort investigated by Kuderer et al. and Yang et al. [1, 2], who reported increased hospitalization and mortality among cancer patients, especially those receiving active treatment. Similar trends were observed in Johannesen et al. and Chavez-MacGregor et al. [4, 7], emphasizing that the burden of comorbidities and immunosuppressive therapy are central drivers of poor prognosis. The present analysis extends these findings into the Omicron phase, showing that while absolute mortality decreased, the relative risk gap between cancer and non-cancer patients persisted or even increased.

In our population, the relative increase in risk of severe disease of cancer decreases with age. This is consistent with previous studies investigating the role of comorbidities in increasing the risk of death in COVID-19 patients [

12]. The reduction is not necessarily appreciable in terms of risk difference; in fact, the absolute risk sharply increases with age, therefore a smaller relative risk could correspond to a larger increase in risk difference.

The protective role of vaccination was strikingly consistent across cancer and non-cancer groups, corroborating evidence from Shroff et al. and Andrews et al. [6, 10]. These results are consistent with other observations showing strong mRNA vaccine efficacy even in immunocompromised hosts. Nevertheless, we observed a reduced effect of any kind of immunization, vaccine-induced, natural, and hybrid, in cancer patients with recent diagnosis. The reduced efficacy for the infection could be confounded by the higher probability of testing in this group, which had frequent access to healthcare facilities. Furthermore, in the omicron period, the general population was mostly tested with antigenic tests that were less sensitive, particularly in the late period of infection, while cancer patients were still tested often with PCR tests, thus increasing the difference in the probability of detecting the infection. Other studies found a reduced efficacy in some subpopulations of cancer patients undergoing specific therapies [13-21].

The reduction in protective effect vs. severe disease cannot be explained by these biases in the probability and modality of tesing. An explanation could be a misclassification of the cause of hospitalization or death in these patients, creating a background noise of outcomes, attributed to COVID-19 but not caused by COVID-19, which necessarily reduces the measured efficacy, particularly in those patients having frequent hospitalizations due to other conditions, as cancer patients. This phenomenon was particularly strong during the omicron period, when COVID-19 was less severe and when the proportion of misclassification was necessarily higher. Nevertheless, in the omicron period, we observed a small, if any, excess of severe COVID-19 for patients with recent diagnosis of cancer, compared with the general population, among the non-vaccinated, suggesting that this bias is present but not too large.

Despite the reassuring protection conferred by vaccination, patients under active therapy remain highly vulnerable, especially during waves driven by immune-evasive variants. Tailored preventive strategies, including priority access to booster doses, monoclonal prophylaxis, and reinforced infection control, remain essential for this subgroup.

Notably, the benefit of hybrid immunity observed here parallels results by Vicentini et al. [

8] in the same population, highlighting that vaccination following natural infection provided the most durable protection against reinfection and severe disease in cancer patients also.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study showed that while COVID-19 vaccines substantially reduced infection and severe outcomes in both cancer and non-cancer populations, cancer patients, particularly those recently diagnosed, continued to face highest risks. Hybrid immunity offered the greatest protectionin both populations. During the Omicron phase, while risk of infection increased, the risk of severe disease declined, reflecting combined effects of vaccination, prior exposure, and variant attenuation, but the severity reduction was less pronounced for cancer patients.

Although vaccine efficacy was broadly similar between cancer and non-cancer groups or slightly less effective in cancer patients, the higher baseline risk of severe disease makes vaccination particularly important in this population. These findings underscore the importance of maintaining targeted vaccination policies, prioritizing boosters, and sustaining active surveillance for individuals with recent or ongoing cancer therapy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Table S1: . Cohort characteristics overall and by history of cancer, Reggio Emilia province, Italy; Table S2: Risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection by cancer prevalence and immunisation status adjusted for sex, age and Charlson Comorbidity Index in the pre-Omicron and Omicron BA.1 periods, Reggio Emilia province, Italy, 20 February 2020–30 September 2022.; Table S3: Risk of severe disease and death from COVID-19 by cancer prevalence and immunisation status adjusted for sex, age and Charlson Comorbidity Index in the pre-Omicron and Omicron BA.1 periods, Reggio Emilia province, Italy, 20 February 2020–30 September 2022.

Author Contributions

M.V., F.V., P.M., L.M., and P.G.R. contributed to the study’s conceptualization and design. M.V., F.V., and S.M. retrieved the initial references for the background section. All members of the working group conducted contact-tracing activities and collected data within the National COVID-19 Surveillance system. P.M. carried out data quality control, managed dataset linkage, and performed the statistical analyses. S.M. and A.Z. conducted laboratory and clinical activities, reviewed and refined key content in the manuscript. L.M., S.M. and P.M. worked on manuscript editing. P.G.R., F.V., S.M., P.M., A.Z., M.V., E.B., and L.M. contributed to the final discussion and formulation of conclusions. P.G.R. supervised the study and ensured data integrity. All authors participated in discussing and interpreting the results and have read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript..

Funding

This study has been partially funded by the Italian Ministry of Health Programma Ricerca Corrente 2026.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Area Vasta Emilia Nord Ethics Committee (no. 2020/0045199). The Ethics Committee authorized the use of patient data, even in the absence of consent, if all reasonable efforts had been made to contact that patient.

Informed Consent Statement

The Ethics Committee authorized the use of patient data, even in the absence of consent, if all reasonable efforts had been made to contact that patient.

Data Availability Statement

data can be requested to the authors after an approval of a protocol of analysis by the Area Vasta Emilia Nord Ethics Committee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

References

- Kuderer, N.M.; Choueiri, T.K.; Shah, D.P.; Shyr, Y.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Rivera, D.R.; Shete, S.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Desai, A.; de Lima Lopes, G., Jr.; et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Sheng, Y.; Huang, C.; Jin, Y.; Xiong, N.; Jiang, K.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Dong, Y.; et al. Clinical characteristics, outcomes, and risk factors for mortality in patients with cancer and COVID-19 in Hubei, China: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangone, L.; Gioia, F.; Mancuso, P.; Bisceglia, I.; Ottone, M.; Vicentini, M.; Pinto, C.; Rossi, P.G. Cumulative COVID-19 incidence, mortality and prognosis in cancer survivors: A population-based study in Reggio Emilia, Northern Italy. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesen, T.B.; Smeland, S.; Aaserud, S.; Buanes, E.A.; Skog, A.; Ursin, G.; Helland, Å. COVID-19 in Cancer Patients, Risk Factors for Disease and Adverse Outcome, a Population-Based Study From Norway. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 652535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shroff, R. T. , Chalasani, P., Wei, R., Pennington, D., Quigley, M. M., Zhong, H., Gage, D., Anderson, A., Kelly, D., Licitra, E. J., Verma, S., Christie, A., Vaidya, R., and Maron, S. B. "Immune responses to two-dose SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in patients with solid tumors on active immunosuppressive therapy." JAMA Oncol 2021; 7: 548–550.

- Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Lei, X.; Zhao, H.; Scheet, P.; Giordano, S.H. Evaluation of COVID-19 Mortality and Adverse Outcomes in US Patients With or Without Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 8, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicentini, M.; Venturelli, F.; Mancuso, P.; Bisaccia, E.; Zerbini, A.; Massari, M.; Cossarizza, A.; De Biasi, S.; Pezzotti, P.; Bedeschi, E.; et al. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection by vaccination status, predominant variant and time from prior infection: a cohort study, Reggio Emilia province, Italy, February 2020 to February 2022. Eurosurveillance 2023, 28, 2200494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y. , Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Tan, W., Pan, C., Cai, X., Xu, J., Qiu, X., Yan, Y., and Tan, C. "The N501Y spike substitution enhances SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission." Nature, 2021; 593: 295–299.

- Andrews, N.; Stowe, J.; Kirsebom, F.; Toffa, S.; Rickeard, T.; Gallagher, E.; Gower, C.; Kall, M.; Groves, N.; O’connell, A.-M.; et al. Covid-19 Vaccine Effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) Variant. New Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1532–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. (2020). Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 28;395(10229):1054-1062. [CrossRef]

- Ferroni, E.; Rossi, P.G.; Alegiani, S.S.; Trifirò, G.; Pitter, G.; Leoni, O.; Cereda, D.; Marino, M.; Pellizzari, M.; Fabiani, M.; et al. Survival of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Northern Italy: A Population-Based Cohort Study by the ITA-COVID-19 Network. Clin. Epidemiology 2020, ume 12, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangone, L.; Rossi, P.G.; Taborelli, M.; Toffolutti, F.; Mancuso, P.; Maso, L.D.; Gobbato, M.; Clagnan, E.; Del Zotto, S.; Ottone, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Vaccination and Risk of Death in People with An Oncological Disease in Northeast Italy. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, M.; Bohlke, K.; Baptiste, D.M.; Dunleavy, K.; Fueger, A.; Jones, L.; Kelkar, A.H.; Law, L.Y.; LeFebvre, K.B.; Ljungman, P.; et al. Vaccination of Adults With Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1699–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.; Wei, Z.; Wu, X. Impaired serological response to COVID-19 vaccination following anticancer therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med Virol. 2022, 94, 4860–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K. Predictors of poor serologic response to COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 172, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, V.G.; Teh, B.W. COVID-19 Vaccination in Patients With Cancer and Patients Receiving HSCT or CAR-T Therapy: Immune Response, Real-World Effectiveness, and Implications for the Future. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228, S55–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monin, L.; Laing, A.G.; Muñoz-Ruiz, M.; McKenzie, D.R.; del Molino del Barrio, I.; Alaguthurai, T.; Domingo-Vila, C.; Hayday, T.S.; Graham, C.; Seow, J.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: Interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, A.; Casado, J.L.; Longo, F.; Serrano, J.J.; Saavedra, C.; Velasco, H.; Martin, A.; Chamorro, J.; Rosero, D.; Fernández, M.; et al. Limited T cell response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine among patients with cancer receiving different cancer treatments. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 166, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasri, M.; Bshesh, K.; Khan, W.; Mushannen, M.; Salameh, M.A.; Shafiq, A.; Vattoth, A.L.; Elkassas, N.; Zakaria, D. Cancer Patients and the COVID-19 Vaccines: Considerations and Challenges. Cancers 2022, 14, 5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosting, S.F.; Van der Veldt, A.A.M.; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H.; Fehrmann, R.S.N.; van Binnendijk, R.S.; Dingemans, A.-M.C.; Smit, E.F.; Hiltermann, T.J.N.; Hartog, G.D.; Jalving, M.; et al. mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccination in patients receiving chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or chemoimmunotherapy for solid tumours: a prospective, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).