1. Introduction

Technology has brought about a revolution in the management of type 1 diabetes (T1D). The adoption of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and insulin pump therapy in the everyday life of children and adolescents with T1D is a real innovation and the most promising choice for optimizing glycemic control in this population [

1,

2].

The mission of CGM is to provide a measurement of interstitial glucose levels not only as a single value but also as a short-term trend, long-term tracking, and daily pattern. In other words, it serves as a real-time (RT) glucose level detector, including not only the most commonly used RT-CGM systems (Dexcom San Diego, CA, Metdronic Northridge, CA) but also the flash CGM system, FreeStyle Libre 2 (Abbott Diabetes Care), after the recent upgrade of its smartphone application, with the only difference remaining the prerequisite of scanning the sensor in order to obtain data [

1,

3]. It becomes evident that the knowledge of glucose levels at every single moment facilitates clinical decisions and makes them more targeted and optimal in avoiding hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia and achieving good metabolic control. A lot of clinical [

4,

5] and real-world studies [

6] as well as systematic reviews and meta-analyses [

7,

8] have clearly proven the beneficial effect of CGM on glycemic control optimization. Targeting further improvement in the context of glycemia and safety, CGM systems incorporated RT alarms, alerts and notifications with the marketing of Guardian (Medtronic) and STS™ (Dexcom) in the mid-2000s [

9].

In parallel, the evolution of insulin pump came to enhance the effect of CGM on metabolic control with hybrid closed loop (HCL) being the most promising entry in diabetes technology, implementing the communication of CGM with insulin pump in clinical practice. There is an increasing number of studies underlining the increase in time in range (TIR) without a concomitant increase in time below range (TBR) among users [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Insulin pump as a stand-alone device is designed to have safety notifications but, as a sensor-augmented or HCL system, its functionality was upgraded with certain alarms intending to warn patients about detected changes in glucose levels or events expected to negatively affect their health status [

15].

Although the whole alarm system keeps a leading role in glucose management, alarm fatigue has been increasingly and inevitably recorded among diabetes technology users. Alarm fatigue is defined as the situation of inappropriate responsiveness to warnings or complete deactivation of them after a period of frequent exposure to false or unnecessary alarms, declining trust in CGM or insulin pump and posing at risk the subsequent utilization of the device. It is an expression of burnout, as receiving a great number of notifications, some of which being proven to be false, may be stressful and exhausting [

16]. An alert is really meaningful, if the user is educated on the significance and utilization of the information provided and responds properly. Otherwise, lack of knowledge predisposes to alarm fatigue.

In this narrative review of the literature published since the early 2000s, we aimed to analyze the phenomenon of alarm fatigue affecting pediatric users of diabetes technology devices and their families. We will focus not only on CGM and insulin pump used independently, but also as part of HCL systems. There is a narrative review [

17] on the benefits of diabetes alarm system but only scarce and scattered data on alarm fatigue, negatively affecting glycemic control, quality of life and sleep of T1D pediatric patients and their parents.

1.1. Types of Alarms

Alarm system can concern CGM, insulin pump or HCL system and can be categorized in the following four groups: 1) CGM threshold that notify when glucose levels cross upwards or downwards a value set by the user, necessitating an action, predictive that are activated before hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia occurs, based on specific algorithms, giving time for preventive measures and others and rate that are released in case of increased velocity of glucose level change, 2) CGM maintenance to ensure proper system operation (calibration, lost sensor, expired sensor, change sensor notification, sensor error, weak signal, low transmitter battery, transmitter failure), 3) HCL system specific (auto mode exit, auto mode sensor integrity failure, basal delivery resumption, maximum suspension, blood glucose required notification, open loop, calibration required for closed loop), 4) insulin pump specific (active temporary basal rate, suspension, low battery, battery out, low reservoir). Similarly, to HCL system, in case of paired use of connected insulin pen and CGM there are notifications for missed or correction dose [

16,

18,

19].

It is useful to understand the difference between an alarm, informing about an immediate issue that needs an urgent action related to medication or diet, and an alert, warning on an upcoming risk situation where a safe action can be taken. Users are notified by sound or vibration with a varying repetition interval and option for delay [

3]. Reliability, validity, timeliness and perceptibility are the prerequisites for an alarm system to be successful [

20].

1.3. Benefits of Diabetes Alarm System in Optimal Glucose Management

The mission of diabetes alarm system is to warn on out-of-range glucose levels and upcoming hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia or notify about technical issues. By informing users about glycemic events before or when they happen, it gives them the opportunity to understand their glucose level daily pattern and take action in order to attain eyglycemia. Alarms serve as an additional valuable tool for optimizing glycemic management, reducing the incidence and severity of acute hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, particularly among users that are not up to date on their glucose profile [

16,

18].

Besides protecting against hypoglycemia, it attains glycemic control, while hyperglycemia alerts have proved to reduce time above range (TAR) and decrease average glucose. The combined result is a decrease in glycemic variability and an in TIR [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Use of these alerts to adjust insulin delivery has the potential to improve glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) [

24].

Indeed, only the adaption of predictive hypoglycemia alert provided additional benefit over traditional low-threshold alerts as TBR <54mg/dl and <70mg/dl and TAR >250mg/dl decreased significantly regardless of the low-threshold alert setting [

25]. Furthermore, in a prospective, observational study involving 47 children and adolescents with T1D, the possibility of optional alarms transitioning from FreeStyle Libre to FreeStyle Libre 2 for 14 days led to increase in TIR and reductions in TAR, number of weekly hypoglycemic events and coefficient of variation [

26].

The introduction of glucose alarms adds to the optimal glucose management and by offering a sense of reassurance and safety [

23,

27,

28]. Parents and young people report protection against hypoglycemic episodes as the primary cause of such feelings [

27], while caregivers of children and adolescents using CGM find alarms useful in understanding the trending direction of glucose levels [

29]. In the school environment, caregivers, teachers or school nurses consider alarm system as a tool that simplifies glycemic management [

24]. Interestingly, in a study, a small number of young people and parents reported that CGM alarms were the best thing about the device [

30]. With the development of HCL system, alarms ensure patients can take the minimal action necessary to maintain the optimal operation of system and manually control their glucose level in the presence of technical issues [

19]. Furthermore, they are particularly useful for overnight management, as interruptions from alarms are fewer due to fewer glycemic events [

31].

1.3. Disadvantages of Diabetes Alarm System

One of the main problems is alarm fatigue, which occurs by too many and maybe false notifications that reduce the responsiveness of users to them. Another challenge is the embarrassment caused by notifications at inappropriate time that produce a sense of loss of privacy [

3]. In addition, some people overreact to hypo- or hyperglycemia alerts, ingesting too many carbohydrates or administering correction insulin bolus too soon after a meal, respectively, which threatens optimal glycemic control [

32].

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted on the PubMed/Medline database to identify relevant studies on the phenomenon of alarm fatigue in T1D children and adolescents and their parents and caregivers using one or more diabetes technology devices; CGM, insulin pump or HCL system. The literature search referred to manuscripts published between 1 January 2000 and 30 September 2025 using the following terms: “alarm fatigue”, “alarm frustration”, “alarm distress”, “device fatigue”, “technology fatigue”, “alert fatigue”, “notification fatigue”, “diabetes”, “glucose”, “CGM”, “insulin pump”, “HCL”. The titles and abstracts of the retrieved manuscripts were scanned for relevance. Articles not published in English were excluded.

3. Results

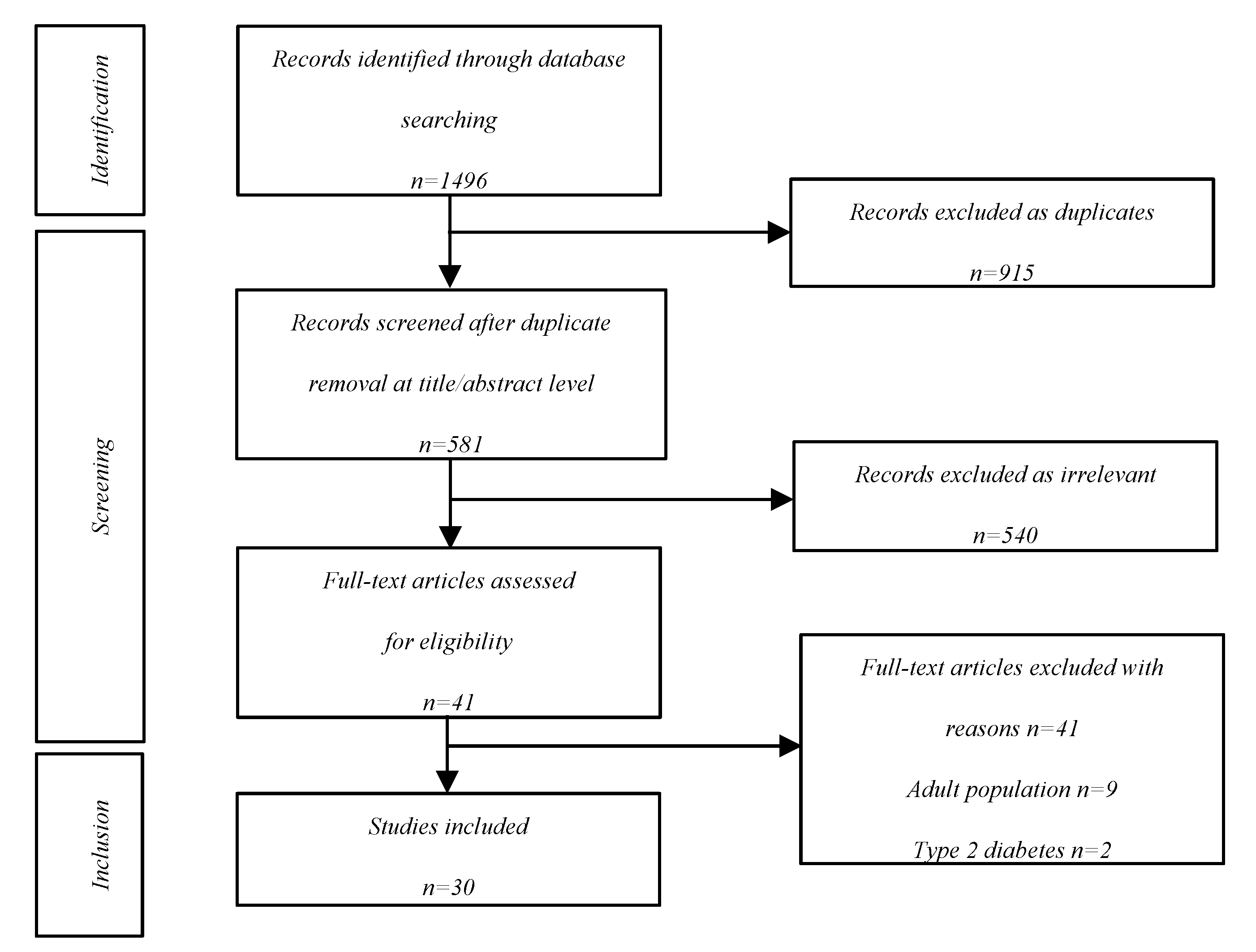

The initial literature search identified 1496 records, of which 915 were excluded as duplicates. Among the 581 reports that were retrieved, 540 were excluded and 11 for reasons presented in detail in the screening flowchart. In the end, 30 articles were included in this narrative review (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Definition

As it was previously mentioned, alarm fatigue is the situation of reduced or absent responsiveness due to frequent false or unnecessary alarms, declining trust and long-term utilization of diabetes device [

16]. The concept of alarm fatigue can also include alarm embarrassment, an issue particularly affecting adolescents. It describes the negative feeling of loss of privacy experienced when users become the centre of attention due to many alarms and may also compromise further wearing a diabetes device. It is a kind of stigma produced when alerts go off in school or social events [

3]. Furthermore, too many alarms may produce disappointment, especially for those users with sub-optimal self-management behaviors and/or a high HbA1c, as they remind them of diabetes and imply personal failure to achieve optimal blood glucose control [

27]. In other words, there is a cycle of frustration, disappointment and embarrassment, leading to reduced adherence and maybe to discontinuation [

28,

33]. It becomes evident that he potential of development of alarm fatigue an compromise CGM benefits [

34,

35].

4.2. Predisposing Factors

The high frequency of alarms increases the potential of fatigue [

16,

19]. It is not known how CGM alarm settings are associated with the number of alarms, and whether the alarm numbers alter patients’ responses and, as a result, is associated with alarm fatigue [

23]. The quantity of alarms may depend on a number of factors, including how often glucose is desirable to be checked, the glucose variability, the awareness of hypoglycemia and the level of low threshold alarm, considering that the higher the alarm is set, the more alarms occur [

16,

23].

The average number of CGM alarms notifying CGM pediatric users and their parents or caregivers is not known. Interdependently of it, a CGM user may perform from 15 to 48 glucose level checks a day [

36], with the upper limit being approached in children due to the frequent and great fluctuations in blood glucose and the difficulty to recognize or report symptoms of hypo- or hyperglycaemia [

37].

It is not only the high frequency but also the sub-optimal accuracy of alerts that predispose to alarm fatigue and cause reduced adherence. Many alarms sound when glucose is already out of range and some of them may be false or unnecessary [

16,

19]. Users feel overwhelmed and fatigued with the constant interruptions and tend to become unresponsive. As a result, alarms lose their urgent character [

16,

18].

It seems that alarm fatigue is caused by an imbalance between sensitivity and specificity of CGM systems, as there are a inverse relationship between sensitivity and specificity [

38,

39]. Nowadays, some clinicians choose to counsel CGM users to set extremely low or high values as hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia alarm thresholds, respectively, in order to minimize early “nuisance alarms” [

40,

41]. On the other hand, there are clinicians that educate patients to choose a rather high hypoglycemia threshold as useful to detect and predict more hypoglycemic events [

41,

42,

43]. The first approach favors specificity at the expense of sensitivity, while the second one promotes alarm fatigue, as by increasing sensitivity, more alarms may be false.Such phenomena question the accuracy and credibility of CGM and makes patients less reactive to alarms and less willing to retain them activated or even continue to use CGM [

44]. In the same context, a too low threshold for hyperglycemia intending to improve glycemic control, increases the risk of alarm fatigue [

20]. However, retrospective studies of TITR do not support concerns that its use in clinical practice may contribute to alarm fatigue [

45]. Scheinker et al [

46] found that hypothetical TITR alarms would trigger between 22% and 41% more frequently than TIR alarms. However, use of robust TITR alarms, set to trigger on the basis of three consecutive readings below the threshold followed by three consecutive readings above the threshold, mitigated the increase in alarm frequency.

However, decoding CGM alarms is not a choice of black or white. The discrepancy between a low threshold alarm intending to prevent hypoglycaemia even more when glucose is descending, and those requiring treatment produces inconvenience and may be a cause of alarm fatigue, as there is a need for SMBG tests to confirm them [

24].

Another frequent cause of nuisance hypoglycemia alarms predisposing to alarm fatigue is compression artifacts caused by decrease in glucose concentration in the interstitial fluid near the sensor tip when the CGM system user sleeps on the CGM sensor [

47].

4.3. Frequency

Alarm fatigue is rather frequent. In an anonymous survey among parents and caregivers of children with T1D using CGM, approximately 25% admitted that they remained unresponsive when the CGM alarms went off repeatedly with potential poor outcomes for their children [

37]. Among 85 children and adolescents between 5 and 18 years old being followed for T1D, alarm fatigue was found to be the main reason for discontinuing CGM [

48] or one of the reasons [

49,

50]. Even adolescent HCL users reported frustration around the number of alarms and notifications associated with the system [

51]. “Alarms” was reported by 40% of pediatric HCL users as the third most common theme and recorded as a cause of HCL discontinuation [

52]. If patients feel the increased mental burden of responding to frequent notifications and alarms is too much, it could be a barrier to adoption of this new technology [

53,

54]. In a study, among CGM ex-users, 26% reported too many alarms. It is a matter of trust to the device to reassure continuing utilization [

55]. Some patients reported anxiety in response to the notifications and occasionally disabled the hyperglycemia alarms to avoid discomfort from constant alerts [

56].

4.4. Quality of Life

Some T1D patients believe that alarms may disrupt their daily life. About 40% of parents and caregivers of children with T1D using CGM reported CGM device as a source of nervousness for them [

37]. Interference in daily life was recorded among 38% of pediatric CGM users [

57]. Alarms being released at inconvenient times draw attention to young users, producing embarrassment [

58]

There are also many negative comments about alarms being annoying as well as a life “living by alarms” [

29]. Furthermore, they may promote a perception that CGM users lead a life dominated and dictated by their diabetes and act as reminders of their continuing struggle to cope with diabetes and achieve optimal glycemic control [

27]. Alarms may produce unwelcomed distractions at school; with various children, reportedly switching alarms off in school due to concerns about drawing attention to themselves and distracting peers [

24].

However, alarm fatigue is not a one way for CGM users. In a study, sensor-wearing was numerically higher in the CGM with alarms group vs. CGM without alarms, and there was no significant difference between the two CGM groups with regard to quality-of-life measurements [

59].

4.5. Quality of Sleep

Alarm fatigue can be expressed as night-time sleep disruption not only for T1D children and adolescents but also for their families [

26,

27,

60,

61]. The transition from finger prick glucose test to CGM did not protect T1D children and adolescents and their families from waking up multiple times during the night for CGM alarms. It is not only the fear of hypoglycemia but also caution about correction boluses overnight that disturbs sleep [

37].

However, nocturnal hypoglycemia deserves special attention due to the urgency of handling with it, as it is reasonable for diabetes technology device users and their parents to be less willing to respond to alarms during night and, as a result, more vulnerable to alarm fatigue. Parents and caregivers can be awakened many times during the night to administer insulin or provide carbohydrates for repetitive high or low glucose levels, respectively. Utilizing the 0–3 scale for the seven subscales of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, with 0 being the best and 3 being the worst, over 50% of parents and caregivers of children with T1D using CGM scored a 2 or 3 on the sleep disturbance subscale. About 70% of them scaled their sleep quality as fairly bad or very bad. It is interesting that 30% of caregivers worried they would incorrectly set alarm limits on the CGM device at night [

37]. In a qualitative study, caregivers of minors with T1D reported waking frequently to check CGM, while several ones confessed that they additionally set clock alarms to make sure that their child’s glucose was in range, despite having a CGM system, revealing a deficiency of trust on CGM alarms, not fulfilling their mission [

62].

In another study, disrupted sleep was commonly reported with 73% of parents/caregivers reporting waking because of diabetes technology. Of these, 54% of parents/caregivers reported waking at least 4 times a week and one of the main reasons reported was CGM alarms (38% parents/caregivers). About 10% of parents/caregivers reported false alarms occurring more than once a week. However, participants graded the impact of diabetes technology for their child as generally positive [

47].

Overnight awaking due to CGM alerts and notifications was also reported in two other studies, performing qualitative narrative analysis of CGM and evaluating its impact on parental sleep [

29,

63].

In a study of T1D children and adolescents while sleeping, awaking was more possible with increased age, at first alarm or with multiple alarms associated with a single hypo- or hyperglycemic episode. A great number of false alarms was detected [

62]. Overnight alarm fatigue preserves the vicious cycle of unresponsiveness as patients with hypoglycaemia react only to 29% of alarms [

29], while parents only wake to 37% of them [

64].

Even insulin pump and HCL system users may suffer of alarm fatigue. Even, with closed loop systems, T1D patients experience nocturnal hypoglycemia 25% of the time [

60]. Waking up due to alarms was reported as frustrating for sensor-augmented pump therapy users, because it was frequently unclear why they went off [

58]. In regards to HCL, the causes of nocturnal alarms were evenly distributed among the four different types of alarms. During the first 2 weeks after initiation of HCL mode, the mean number of nocturnal alarms increased significantly, followed by a steady decline in HCL mode and sensor use. Nocturnal alarms may be a contributing factor to the decline in system use, as has been described previously [

18].

4.6. Management

4.6.1. General Principles

In order to face successfully the phenomenon of alarm fatigue, alarms should be designed in a way that they fulfill their mission, to reliably detect and warn for upcoming events that require action [

66], in the most user-friendly way. In other words, increasing accuracy and reliability is translated to less alarm fatigue and greater safety and more trust to the device. Their adjustment must achieve a balance between safety and quality of life, avoiding unnecessary notifications that can generate alarm fatigue [

16].

4.6.2. Alarm Deactivation

The option to turn off alarms, has the potential to reduce alarm fatigue among users who are more prone to experience annoyance at the expense of treatment satisfaction and adherence [

3]. The flexibility to turn off the alarms when needed and eliminate disruptions at inappropriate times were recorded as the two greatest benefits of optional alarms, offering a sense of control, freedom and strength [

28]. Some CGM users select deactivating all alarms overnight and keeping only for hypoglycemia as a solution to cope with alarm fatigue [

56].

4.6.3. Development of Algorithms

The development of algorithms may serve in this context [

16], for learning individual glucose profiles and providing earlier and more accurate prediction of glucose levels, focused on hypoglycemia [

67,

68]. Maximizing model performance for glucose risk prediction and management is crucial to reduce the burden of alarm fatigue on CGM users [

68,

71]. There is need to develop more accurate and reliable CGM systems. Even the compression artifacts should be eliminated [

47,

71].

4.6.4. Selection of Settings

Furthermore, there is a need for efforts to make some alarms and alerts more discreet like a mobile text notification in order to eliminate social and emotional embarrassment. To this context, vibrating alarms possess an advantage compared with audible alarms, as they become aware even in noisy environment and they produce less embarrassment. Different kinds of alarms should be distinctive for easier and quicker recognition of the nature and severity of the problem with gradual escalation in case they remain unresponsive in order to increase the possibility of reaction [

16]. However, during the night, it is important for the children or adolescents and their parents/caregivers to be aware of the alarms, as many of the alarms are not heard at night by them who oversee their treatment [

29,

70]. Sharing alarms with parents may reduce some of the load of responsiveness undertaken by the users and systems have developed to support that need [

70]. Furthermore, selection of rather necessary hypo- and hyperglycemia threshold alarms over rate of change alerts may be an attempt to prevent alert fatigue or to limit the number of alert disturbances both in the classroom and overnight [

24].

4.6.5. Threshold Levels

It is important for alarms to overcome the role of automated reminders and be connected with real-life circumstances promoting targeted and supportive interventions. CGM is something more than a “hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia detector”. It is a monitoring device that has the ability not only to detect but also to avoid hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. There are periods of time when an “alarm not necessitating treatment” may be valuable such as in severe hypoglycemia unawareness [

24]. On the other hand, in periods of fatigue, customization of alarms to provide meaningful support in the form of notifications is recommended. Health professionals should help patients and their families handle with any difficulty associated to alarm fatigue in order to overcome any resistance to use and take advantage of them or avoid their deactivation or diabetes technology rejection [

3]. At last, it is a matter of choice between risk and nuisance when the scale moves towards timeliness of excursion detection or false alarm, respectively [

39].

Therefore, it is essential to individualize the activation threshold for each person, ensuring a balance between effectiveness and quality of life. Patient-centered alarm configuration in daily life includes even varying alarm settings according to time of day or special situations such as the physical activity or sick days [

16] and adjusting them according to course of glycemic control [

24]. At first, it is rather recommended to set extremely low and high hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia alarm thresholds, respectively, to eliminate false alarms in favors of effective long-term use. Setting higher hypoglycemic thresholds predisposes to alarm fatigue phenomenon, not necessarily improving glycemic control as alarms are ignored and no action is undertaken. The option to delay the hyperglycemia alert has been shown in some studies to reduce the incidence of hypoglycemia due to overcorrection, by avoiding unnecessary insulin administration [Oriot]. As glucose control improves with concomitant reduction of TBR, a more aggressive level of 60 and 140 mg/dl for hypo- and hyperglycemia threshold, could be selected, respectively. On the other hand, in a patient without an optimal glycemic control such alarm settings would be out of scope and rather bothering [

24]. Furthermore, the discrimination of hypo- and hyperglycemia in regards to the urgency of treatment, is in favor of a delay in the alarm release in the second situation.

An alarm threshold of 75 mg/dL was the optimal cutoff for hypoglycemia alarms in order to achieve a TBR < 1% as it offered the essential time for CGM users to react and overcame the obstacle of the deficits in the counter-regulatory mechanisms of euglycemia restoration and kept false positive rate at a low level. In the majority of cases, a hypoglycemic alarm threshold at around 70 mg/dl, reduces TBR > 50% [Lin]. The alarm threshold should be adjusted according to age, medical history and hypoglycemia awareness as well as the frequency of hypoglycemic events during certain periods [

71].

Hyperglycemia alerts are rather helpful in young children with greater risk of diabetic ketoacidosis, for insulin pump users and for patients with good glycemic control who want to further ameliorate glycemic parameters [

71]. An alarm threshold of 170 mg/dL was the optimal cutoff for hyperglycemia alarms in order to achieve a TAR < 5% and HbA1c ≤ 7%. Gradually lowering hyperglycemia alarm thresholds leads to greater numbers of alarms predisposing to alarm fatigue. Thus, this practice could be considered to be adapted in daily life of CGM users who need to further optimize HbA1c or reduce TAR, without increasing TBR, but until the level there is no further improvement in glycemic control. Then, under the risk of alarm fatigue alarm adjustments should stay stable or even get a bit loosened [

23].

4.6.6. Personalized Approach

There is a need for substantial personalized training aiming to strengthen patient confidence, reduce disease-related anxiety and encourage active participation in daily self-care. Clear communication reduces anxiety, facilitates learning, and promotes greater adherence to treatment. It is important to optimize alarm settings with respect to each user’s preferences regarding frequency, timing, and content of notifications [

56], in order to improve user engagement and long-term adherence [

72,

73]. For HCL users there is a need for re-education in the timing of sensor calibrations, reacting to system alerts and setting alerts to reduce the number of nuisance alarms [

74]. Identifying the source of alarms, especially nocturnal ones, on an individual basis, is essential in order to make the appropriate clinical interventions that can alleviate the recurrence of specific alarms for each person [

18]. It is essential to configure only the alerts necessary for decision-making and adjust them to each person. This can be mitigated by adjusting thresholds according to time, activating vibration mode, or temporarily disabling some alerts. Diabetes education is key for the user to know how to act in response to each alert and avoid unnecessary corrections.

4.6.7. Recommendations

There are specific recommendations regarding CGM glucose alarms for individuals who are new to CGM. The procession of adaption in daily life passes through education on alarms, psychological support to handle related symptoms and concerns, regular review of glucose data, gradual approach to set up alarms starting with the most important, sharing data with parents/caregivers [

17].

For, T1D patients resistant to use CGM alarms, Miller et al. [

3] published a five-step practical approach. After uncovering patients’ anxieties, health professionals should discuss how the upcoming change could meet their needs. It is important to analyze the benefits of CGM, how they can integrate it into their lives and use optional alarms/alerts. For those patients, the best way is to make them experience in their daily life how alarms have the ability to eliminate anxiety and improve quality of life. This opportunity may be given gradually, choosing to turn on and adjust alarms properly without pressure and deactivate them at any time. Patients should be encouraged to review their glucose reports and daily graphs in order to identify trends, when and why they occur and how to prevent hypo- or hyperglycemic events. This is the critical point to offer the alternative of alarms, if they can understand the significance of potential warning on upcoming glycemic events to take action. In case the patient chooses to use alarms, counselling on effective utilization according to their needs is suggested. By analyzing their glucose pattern, glucose thresholds are properly set and alarms are appropriately activated.

5. Conclusions

In summary, with the utilization of technology for optimal glucose management in T1D, the phenomenon of alarm fatigue has raised in parallel. It substitutes a situation of inappropriate response to a high frequency of alarms even more when some of them are proved to be false. Unfortunately, it is not limited only in pediatric patients but it also affects their parents/caregivers. A cycle of frustration, disappointment and embarrassment is provoked and maintained, leading to reduced adherence and maybe to discontinuation of diabetes technology devices. As alarms are a valuable tool of CGM, insulin pump and HCL system with undoubted benefits on optimal glycemic management, it is essential to find the way to reinforce their incorporation in everyday life of children and adolescents with T1D. There is a need for individualized approach including education on alarms, psychological support, regular review of glucose data, gradual adoption of personalized alarms and sharing of the load of handling with parents/caregivers. This should be a life long process. Furthermore, efforts should be made to the direction of improved accuracy and development of friendly-user settings and algorithms to further increase users’ trust on diabetes alarm system. Only then, optimal and long-term utilization of alarms could ensure the best possible glycemic control for every patient without compromising quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and A.G.T.; methodology, S.G, A.G.T..; software, S.G., E.P.K., V.R.T.; investigation, S.G., E.P.K., V.R.T. T.P., S.N., A.G.T.; resources, S.G., E.P.K., V.R.T. T.P., S.N., A.G.T.; data curation, S.G., E.P.K., V.R.T. T.P., S.N., A.G.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G., E.P.K., V.R.T. T.P., S.N., A.G.T.; writing—review and editing, S.G., E.P.K., V.R.T. T.P., S.N., A.G.T.; supervision, A.G.T.; project administration, A.G.T.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CGM |

continuous glucose monitoring |

| HbA1C |

glycated hemoglobin |

| HCL |

hybrid closed loop |

| TAR |

time above range |

| TBR |

time below range |

| TIR |

time in tight range |

| TITR |

time in range |

| T1D |

type 1 diabetes |

References

- Biester. ; T.; Berget.; C.; Boughton.; C.; Cudizio.; L.; Ekhlaspour.; L.; Hilliard.; M.; Reddy.; L.; Sap Ngo Um.; S.; Schoelwer.; M.; Sherr.; J.; et al. International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2024: Diabetes Technologies - Insulin Delivery. Horm Res Paediatr 2024, 97, 636–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauschmann. ; M.; Cardona-Hernandez.; R.; DeSalvo.; D.; Hood.; K.; Laptev.; D.; Lindholm Olinder.; A.; Wheeler.; B.; Smart.; C. International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2024 Diabetes Technologies: Glucose Monitoring. Horm Res Paediatr 2025, 97, 615–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller. ; E.; Midyett.; L. Just Because You Can.; Doesn’t Mean You Should…Now. A Practical Approach to Counseling Persons with Diabetes on Use of Optional CGM Alarms. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021, 23, S66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelino. ; T.; Phillip.; M.; Bratina.; N.; Nimri.; R.; Oskarsson.; P.; Bolinder.; J. Effect of Continuous Glucose Monitoring on Hypoglycemia in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Laboudi. ; A.; Godsland.; I.; Johnston.; D.; Oliver.; N. Measures of Glycemic Variability in Type 1 Diabetes and the Effect of Real-Time Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016, 18, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, EE.; Abraham, MB.; Smith, GJ.; Mountain, JA.; Jones, TW.; Davis, EA. Continuous Glucose Monitoring Improves Glycemic Outcomes in Children With Type 1 Diabetes: Real-World Data From a Population-Based Clinic. Diabetes Care. [CrossRef]

- Maiorino, MI.; Signoriello, S.; Maio, A.; Chiodini, P.; Bellastella, G.; Scappaticcio, L.; Longo, M.; Giugliano, D.; Esposito, K. Effects of Continuous Glucose Monitoring on Metrics of Glycemic Control in Diabetes: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicembrini, I.; Cosentino, C.; Monami, M.; Mannucci, E.; Pala, L. Effects of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Diabetol 2021, 58, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howsmon, D.; Bequette, BW. Hypo- and Hyperglycemic Alarms: Devices and Algorithms. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015, 9, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Boom, L.; Auzanneau, M.; Woelfle, J.; Sindichakis, M.; Herbst, A.; Meraner, D.; Hake, K.; Klinkert, C.; Gohlke, B.; Holl, RW. Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Pump Therapy Sensor Augmented Pump or Automated Insulin Delivery in Different Age Groups (0.5 to <26 Years) With Type 1 Diabetes From 2018 to 2021: Analysis of the German/Austrian/Swiss/Luxemburg Diabetes Prospective Follow-up Database Registry. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2024, 18, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, JL.; Hermann, JM.; Campbell, F.; Foster, NC.; Hofer, SE.; Allgrove, J.; Maahs, DM.; Kapellen, TM.; Holman, N.; Tamborlane, WV.; Holl, RW.; Beck, RW.; Warner JT; T1D Exchange Clinic Network. ; the DPV Initiative.; and the National Paediatric Diabetes Audit and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health registries. Use of insulin pump therapy in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes and its impact on metabolic control: comparison of results from three large.; transatlantic paediatric registries. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pańkowska, E.; Błazik, M.; Dziechciarz, P.; Szypowska, A.; Szajewska, H. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion vs. multiple daily injections in children with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Pediatr Diabetes 2009, 10, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickup, JC.; Sutton, AJ. Severe hypoglycaemia and glycaemic control in Type 1 diabetes: meta-analysis of multiple daily insulin injections compared with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. Diabet Med 2008, 25, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, MB.; de Bock, M.; Smith, GJ.; Dart, J.; Fairchild, JM.; King, BR.; Ambler, GR.; Cameron, FJ.; McAuley, SA.; Keech, AC.; Jenkins, A.; Davis, EA.; O'Neal, DN.; Jones TW; Australian Juvenile Diabetes Research Fund Closed-Loop Research group. Effect of a Hybrid Closed-Loop System on Glycemic and Psychosocial Outcomes in Children and Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr 2021, 175, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estock, JL.; Codario, RA.; Zupa, MF.; Keddem, S.; Rodriguez, KL. Insulin Pump Alarms During Adverse Events: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2025, 19, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivers, JP.; Mackowiak, L.; Anhalt, H.; Zisser, H. "Turn it off!": diabetes device alarm fatigue considerations for the present and the future. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2013, 7, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakauer, M.; Travassos, S.; Rodacki, M.; Gabbay MAL. ; Vianna AGD.; Scharf M.; Lamounier RN.; Franco DR.; Araújo LR.; Calliari LE. Glucose alarms approach with flash glucose monitoring system: a narrative review of clinical benefits. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2025, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobry, EC.; Vigers, T.; Berget, C.; Messer, LH.; Wadwa, RP.; Pyle, L.; Forlenza, GP. Frequency and Causes of Nocturnal Alarms in Youth and Young Adults With Type 1 Diabetes Using a First-Generation Hybrid Closed-Loop System. Diabetes Spectr 2024, 37, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howsmon, D.; Bequette, BW. Hypo- and Hyperglycemic Alarms: Devices and Algorithms. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015, 9, 1126–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estock, JL.; Codario, RA.; Zupa, MF.; Keddem, S.; Rodriguez, KL. Insulin Pump Alarms During Adverse Events: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2025, 19, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pleus, S.; Eichenlaub, M.; Waldenmaier, D.; Freckmann, G. A Critical Discussion of Alert Evaluations in the Context of Continuous Glucose Monitoring System Performance. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2024, 18, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marigliano, M.; Piona, C.; Mancioppi, V.; Morotti, E.; Morandi, A.; Maffeis, C. Glucose sensor with predictive alarm for hypoglycaemia: Improved glycaemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2024, 26, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, YK.; Groat, D.; Chan, O.; Hung, M.; Sharma, A.; Varner, MW.; Gouripeddi, R.; Facelli, JC.; Fisher, SJ. Alarm settings of continuous glucose monitoring systems and associations to glucose outcomes in type 1 diabetes. J Endocr Soc 2019, 4, bvz005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erie, C.; Van Name, MA.; Weyman, K.; Weinzimer, SA.; Finnegan, J.; Sikes, K.; Tamborlane, WV.; Sherr, JL. Schooling diabetes: Use of continuous glucose monitoring and remote monitors in the home and school settings. Pediatr Diabetes 2018, 19, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhr, S.; Derdzinski, M.; Welsh, JB.; Parker, AS.; Walker, T.; Price, DA. Real-World Hypoglycemia Avoidance with a Continuous Glucose Monitoring System's Predictive Low Glucose Alert. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019, 21, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, R.; Scotton, C.; Leonardi, L.; Cauvin, V.; Maines, E.; Angriman, M.; Pertile, R.; Valent, F.; Soffiati, M.; Faraguna, U. Impact of intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring with alarms on sleep and metabolic outcomes in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 2022, 59, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, J.; Blackburn, M.; Allen, J.; Campbell, F.; Elleri, D.; Leelarathna, L.; Rankin, D.; Tauschmann, M.; Thabit, H.; Hovorka, R. Patients' and caregivers' experiences of using continuous glucose monitoring to support diabetes self-management: qualitative study. BMC Endocr Disord 2018, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varughese, B.; Silvey, M.; Harper, G.; Rajkovic, I.; Hoffmann, P. The Value of Optional Alarms in Continuous Glucose Monitoring Devices: A Survey on Patients and their Physicians. Diabetes Stoffw Herz 2021, 30, 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Pickup, JC.; Holloway, MF.; Samsi, K. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes: A qualitative framework analysis of patient narratives. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, M.; Laffel, L.; Cheng, J.; Beck, R.; Coffey, J.; Huang, E.; Kollman, C.; Lawrence, J.; Lee, J.; Ruedy, K.; Tamborlane, W.; Wysocki, T.; Xing D; Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Satisfaction with continuous glucose monitoring in adults and youths with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2011, 28, 1118–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturralde, E.; Tanenbaum, ML.; Hanes, SJ.; Suttiratana, SC.; Ambrosino, JM.; Ly, TT.; Maahs, DM.; Naranjo, D.; Walders-Abramson, N.; Weinzimer, SA.; Buckingham, BA.; Hood, KK. Expectations and Attitudes of Individuals With Type 1 Diabetes After Using a Hybrid Closed Loop System. Diabetes Educ 2017, 43, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, B.; Gross, K.; Rikalo, N.; Schwartz, S.; Wahl, T.; Page, C.; Gross, T.; Mastrototaro, J. Alarms based on real-time sensor glucose values alert patients to hypo- and hyperglycemia: the guardian continuous monitoring system. Diabetes Technol Ther 2004, 6, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anhalt, H. Limitations of Continuous Glucose Monitor Usage. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016, 18, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard-Kelly, KD.; Martínez-Brocca, MA.; Glatzer, T.; Oliver, N. Identifying the deficiencies of currently available CGM to improve uptake and benefit. Diabet Med 2024, 41, e15338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruttomesso, D.; Laviola, L.; Avogaro, A.; Bonora, E.; Del Prato, S.; Frontoni, S.; Orsi, E.; Rabbone, I.; Sesti, G. ; Purrello F; of the Italian Diabetes Society (SID). The use of real time continuous glucose monitoring or flash glucose monitoring in the management of diabetes: A consensus view of Italian diabetes experts using the Delphi method. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2019, 29, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleppo, G. Approaches for successful outcomes with continuous glucose monitoring. In: Role of continuous glucose monitoring in diabetes treatment. American Diabetes Association, 2018.

- Kaylor, MB. ; Morrow L Alarm fatigue and sleep deprivation in carers of children using continuous glucose monitors. Diabetes Care for Children & Young People DCCYP 2022, 11, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Bewick, V.; Cheek, L.; Ball, J. Statistics review 13: receiver operating characteristic curves. Crit Care 2004, 8, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, A.; Mahalingam, A.; Brauker, J. Methods of evaluating the utility of continuous glucose monitor alerts. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010, 4, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ives, B.; Sikes, K.; Urban, A.; Stephenson, K.; Tamborlane, WV. Practical aspects of real-time continuous glucose monitors: the experience of the Yale Children's Diabetes Program. Diabetes Educ 2010, 36, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, IB. Clinical review: Realistic expectations and practical use of continuous glucose monitoring for the endocrinologist. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009, 94, 2232–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinzimer, SA. Analysis: high-tech diabetes technology and the myth of clinical "plug and play". J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010, 4, 1465–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McGarraugh, G. Alarm characterization for continuous glucose monitors used as adjuncts to self-monitoring of blood glucose. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010, 4, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliss, JP.; Dunn, MC. Behavioural implications of alarm mistrust as a function of task workload. Ergonomics 2000, 43, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, V.; Pettus, JH. Time in Tight Range for Patients With Type 1 Diabetes: The Time Is Now.; or Is It Too Soon? Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 782–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheinker, D.; Maahs, DM. Time in Tight Range for Patients With Type 1 Diabetes: Examining the Potential for Increased Alarm Fatigue. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, e1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulzer, B.; Freckmann, G.; Ziegler, R.; Schnell, O.; Glatzer, T.; Heinemann, L. Nocturnal Hypoglycemia in the Era of Continuous Glucose Monitoring. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2024, 18, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfel, A.; Liberman, A.; Yackobovitch-Gavan, M.; Phillip, M.; Nimri, R. Executive Functions and Adherence to Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2020, 22, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, K.; Crabtree, V.; Adolfsson, P.; Davies, M.; Kerr, D.; Kraus, A.; Gianferante, D.; Bevilacqua, E.; Serbedzija, G. Impact of Type 1 Diabetes Technology on Family Members/Significant Others of People With Diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2016, 10, 824–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, P.; Amiel, SA. Hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes: technological treatments.; their limitations and the place of psychology. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Fried, L.; Dart, J.; de Bock, M.; Fairchild, J.; King, B.; Ambler, GR.; Cameron, F.; McAuley, SA.; Keech, AC.; Jenkins, A.; O Neal, DN.; Davis, EA.; Jones, TW.; Abraham MB; Australian JDRF Closed Loop Research group. Hybrid closed-loop therapy with a first-generation system increases confidence and independence in diabetes management in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2022, 39, e14907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, LH.; Berget, C.; Vigers, T.; Pyle, L.; Geno, C.; Wadwa, RP.; Driscoll, KA.; Forlenza, GP. Real world hybrid closed-loop discontinuation: Predictors and perceptions of youth discontinuing the 670G system in the first 6 months. Pediatr Diabetes 2020, 21, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grando, MA.; Bayuk, M.; Karway, G.; Corrette, K.; Groat, D.; Cook, CB.; Thompson, B. Patient Perception and Satisfaction With Insulin Pump System: Pilot User Experience Survey. J Diabetes Sci Technol, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, MA.; Roberts, A.; Smith, GJ.; Abraham, MB.; Davis, EA.; Jones, TW. The Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring With Remote Monitoring Improves Psychosocial Measures in Parents of Children With Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2641–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, WH.; Hessler, D. Perceived accuracy in continuous glucose monitoring: understanding the impact on patients. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015, 9, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Rodriguez, A.; Fernández-Conde, A.; Leirós-Rodríguez, R.; Opazo ÁT. ; Martinez-Blanco N. The Experience of Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus with the Use of Glucose Monitoring Systems: A Qualitative Study. Nurs Rep 2025, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cemeroglu, AP.; Stone, R.; Kleis, L.; Racine, MS.; Postellon, DC.; Wood, MA. Use of a real-time continuous glucose monitoring system in children and young adults on insulin pump therapy: patients' and caregivers' perception of benefit. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010, 11, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashotte, J.; Tousignant, K.; Richardson, C.; Fothergill-Bourbonnais, F.; Nakhla, MM.; Olivier, P.; Lawson, ML. Living with sensor-augmented pump therapy in type 1 diabetes: adolescents' and parents' search for harmony. Can J Diabetes 2014, 38, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New, JP.; Ajjan, R.; Pfeiffer, AF.; Freckmann, G. Continuous glucose monitoring in people with diabetes: the randomized controlled Glucose Level Awareness in Diabetes Study (GLADIS). Diabet Med 2015, 32, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuBose, SN.; Bauza, C.; Verdejo, A.; Beck, RW.; Bergenstal, RM.; Sherr J; HYCLO Study Group. Real-World.; Patient-Reported and Clinic Data from Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes Using the MiniMed 670G Hybrid Closed-Loop System. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021, 23, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzon, A.; McDonough, R.; Meltzer, LJ.; Patton, SR. Sleep and type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents: Proposed theoretical model and clinical implications. Pediatr Diabetes 2019, 20, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, DM.; Calhoun, PM.; Maahs, DM.; Chase, HP.; Messer, L.; Buckingham, BA.; Aye, T.; Clinton, PK.; Hramiak, I.; Kollman, C.; Beck RW; In Home Closed Loop Study Group. Factors associated with nocturnal hypoglycemia in at-risk adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2015, 17, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispham, JA.; Hughes, AS.; Fan, L.; Perez-Nieves, M.; McAuliffe-Fogarty, AH. "I've Had an Alarm Set for 3:00 a.m. for Decades": The Impact of Type 1 Diabetes on Sleep. Clin Diabetes 2021, 39, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, Z.; Rachmiel, M.; Pinhas-Hamiel, O.; Boaz, M.; Bar-Dayan, Y.; Wainstein, J.; Tauman, R. Parental sleep quality and continuous glucose monitoring system use in children with type 1 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 2014, 51, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckingham, B.; Block, J.; Burdick, J.; Kalajian, A.; Kollman, C.; Choy, M.; Wilson, DM. ; Chase P; Diabetes Research in Children Network. Response to nocturnal alarms using a real-time glucose sensor. Diabetes Technol Ther. [CrossRef]

- Mumaw, RJ.; Roth, EM.; Patterson, ES. Lessons from the Glass Cockpit: Innovation in Alarm Systems to Support Cognitive Work. Biomed Instrum Technol 2021, 55, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouri, O.; Cigler, M.; Vettoretti, M.; Mader, JK.; Choudhary, P.; Renard E; HYPO-RESOLVE Consortium. Hypoglycaemia detection and prediction techniques: A systematic review on the latest developments. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2021, 37, e3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, C.; Guy, MJ.; Kumaran, A.; O'Kane, AA.; Ayobi, A.; Chapman, A.; Marshall, P.; Boniface, M. Explainable Machine Learning for Real-Time Hypoglycemia and Hyperglycemia Prediction and Personalized Control Recommendations. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2024, 18, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, KD.; Wysocki, T.; Ully, V.; Mader, JK.; Pieber, TR.; Thabit, H.; Tauschmann, M.; Leelarathna, L.; Hartnell, S.; Acerini, CL.; Wilinska, ME.; Dellweg, S.; Benesch, C.; Arnolds, S.; Holzer, M.; Kojzar, H.; Campbell, F.; Yong, J.; Pichierri, J.; Hindmarsh, P.; Heinemann, L.; Evans, ML.; Hovorka, R. Closing the Loop in Adults.; Children and Adolescents With Suboptimally Controlled Type 1 Diabetes Under Free Living Conditions: A Psychosocial Substudy. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2017, 11, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, E. Analysis of a remote system to closely monitor glycemia and insulin pump delivery--is this the beginning of a wireless transformation in diabetes management? J Diabetes Sci Technol 2013, 7, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriot, P.; Klipper dit Kurz, N.; Ponchon, M.; Weber, E.; Colin, IM.; Philips, JC. Benefits and limitations of hypo/hyperglycemic alarms associated with continuous glucose monitoring in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Epidemiol Manag 2023, 9, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidargaddi, N.; Almirall, D.; Murphy, S.; Nahum-Shani, I.; Kovalcik, M.; Pituch, T.; Maaieh, H.; Strecher, V. To Prompt or Not to Prompt? A Microrandomized Trial of Time-Varying Push Notifications to Increase Proximal Engagement With a Mobile Health App. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e10123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretolesi, D.; Motnikar, L.; Till, B.; Uhl, J. Notifying Users: Customisation Preferences for Notifications in Health and Well-being Applications. In: Meschtscherjakov.; A..; Midden.; C..; Ham.; J. (eds) Persuasive Technology. PERSUASIVE 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science.; vol 13832. Springer.; Cham. [CrossRef]

- Messer, LH.; Forlenza, GP.; Sherr, JL.; Wadwa, RP.; Buckingham, BA.; Weinzimer, SA.; Maahs, DM.; Slover, RH. Optimizing Hybrid Closed-Loop Therapy in Adolescents and Emerging Adults Using the MiniMed 670G System. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).