Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

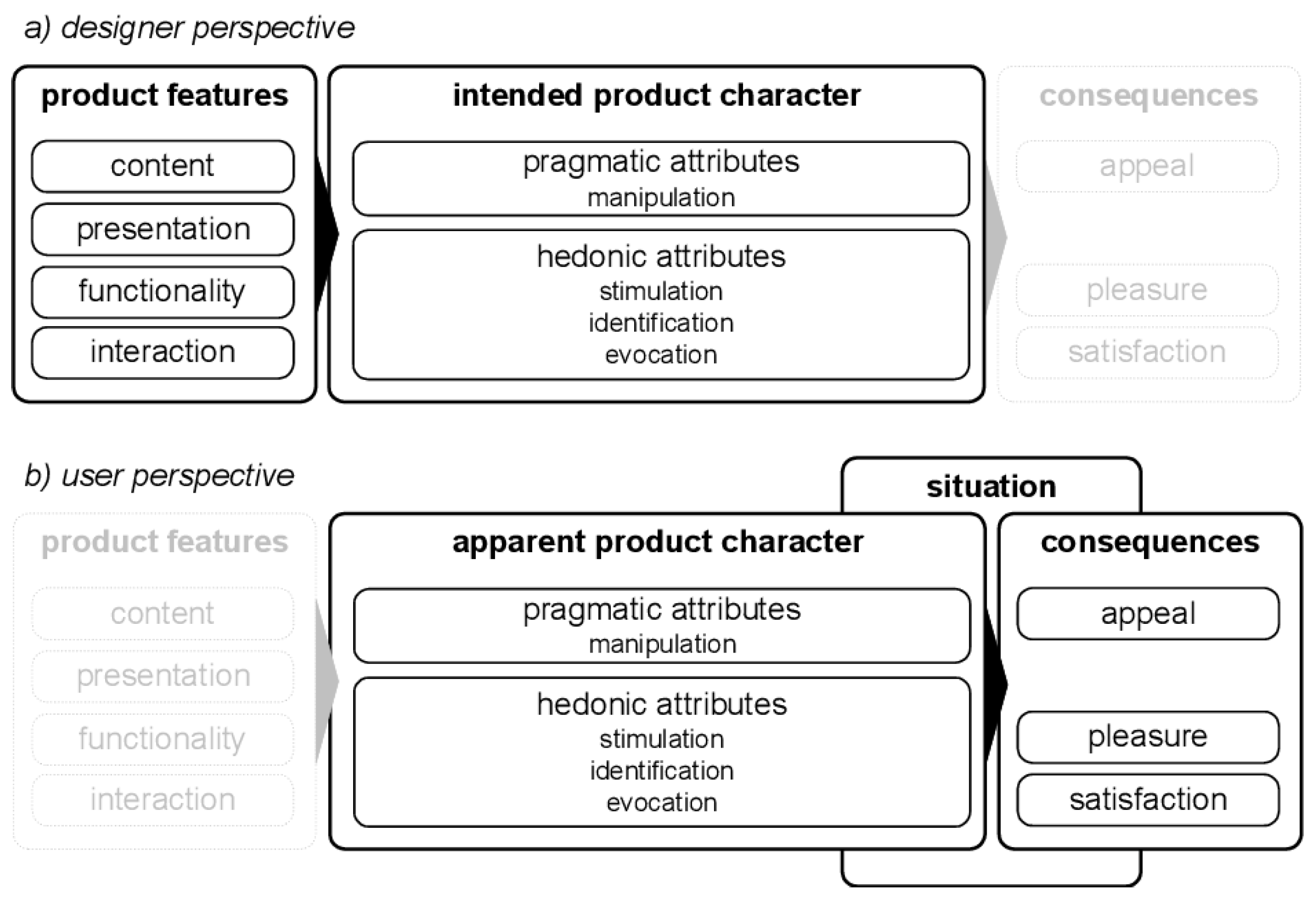

Theoretical Background

1.1.1. Museum Visitor Studies and Meaning Making

1.1.2. Historic Site Interpretation Centers in the Gulf Region

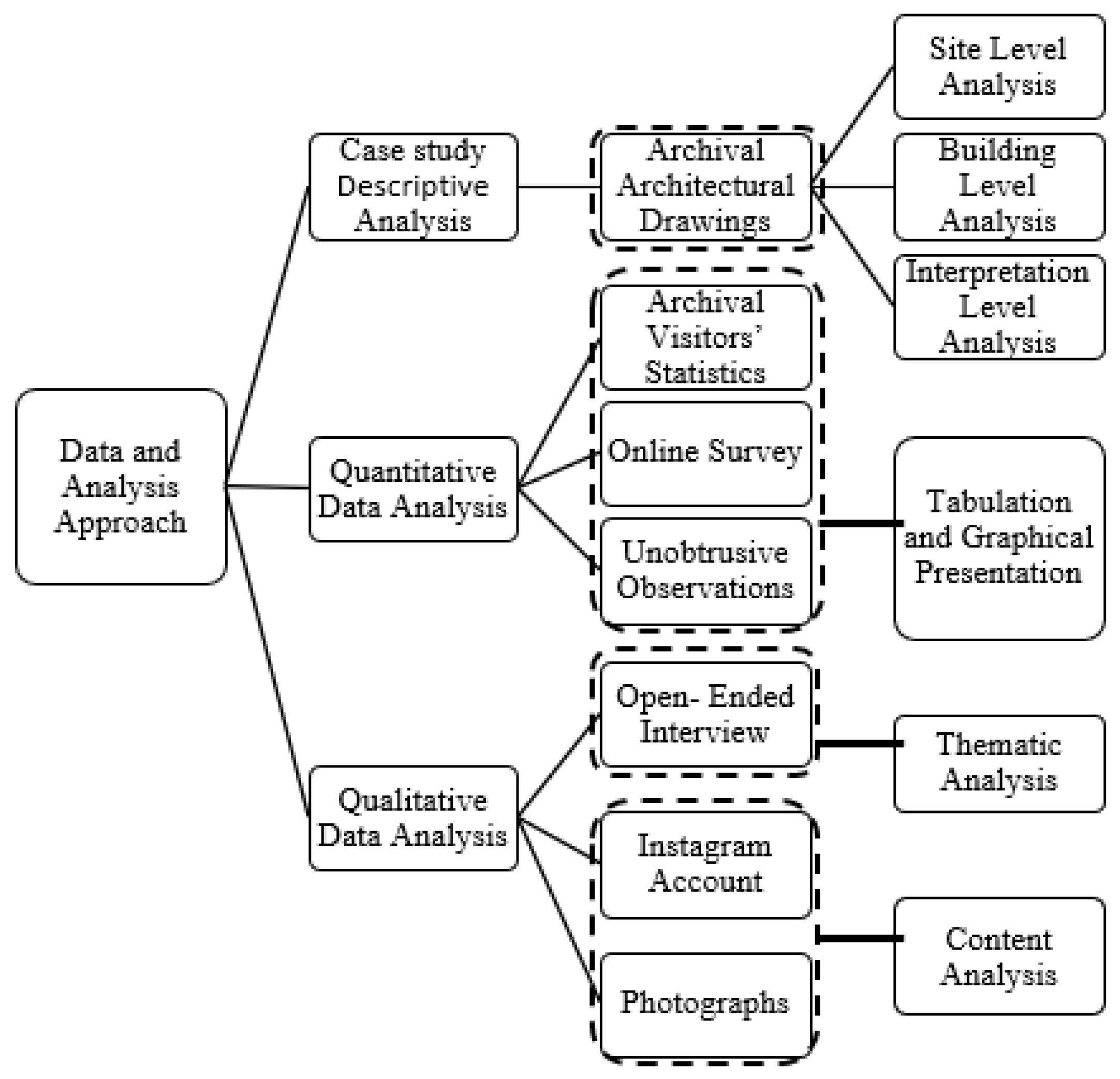

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology and Research Design

2.2. Rationale and Justification of Research Design

2.3. Data Collection Methods and Analysis Procedures

2.3.1. Archival Documents

2.3.2. Online Survey: Design and Pilot Test

2.3.3. Unobtrusive Observation

2.3.4. Semi-Structured Open-Ended Interview Design and Pilot Test

2.3.5. Data Collection Procedure of the Open-Ended Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Visitors’ Records and Experience

3.1.1. Visitation Records of Historic Site Interpretation Centers and Historic Sites

3.1.2. Survey Findings: Visitor Perceptions and Suggestions

3.1.3. Observation Findings: Visitor Behaviors On-Site vs. In Centers

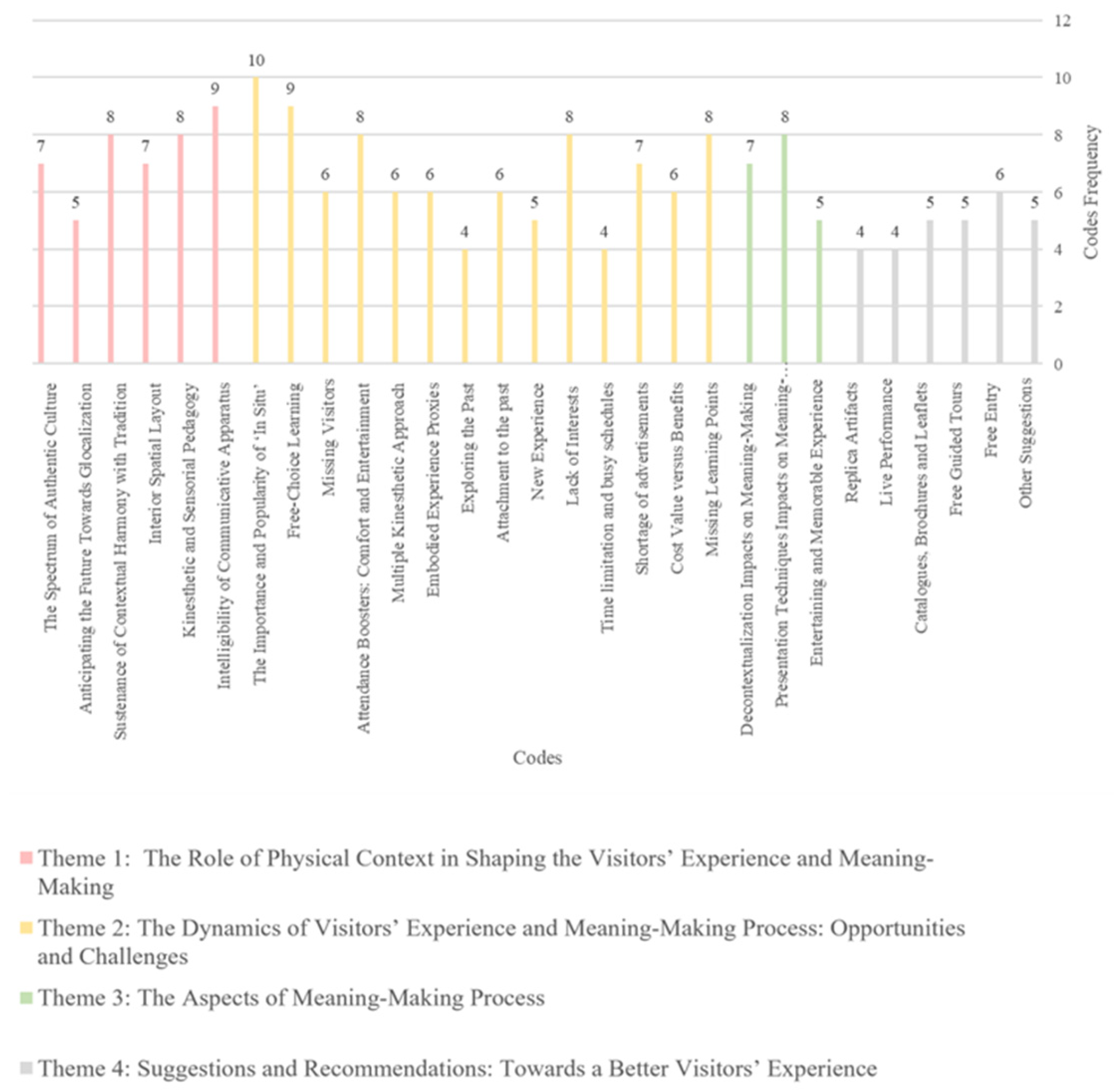

3.2. Data Analysis of Open-Ended Interviews

3.2.1. The Role of Physical Context in Shaping Visitors’ Experience and Meaning-Making

3.2.2. The Dynamics of Visitors’ Experience and Meaning-Making Process: Opportunities and Challenges

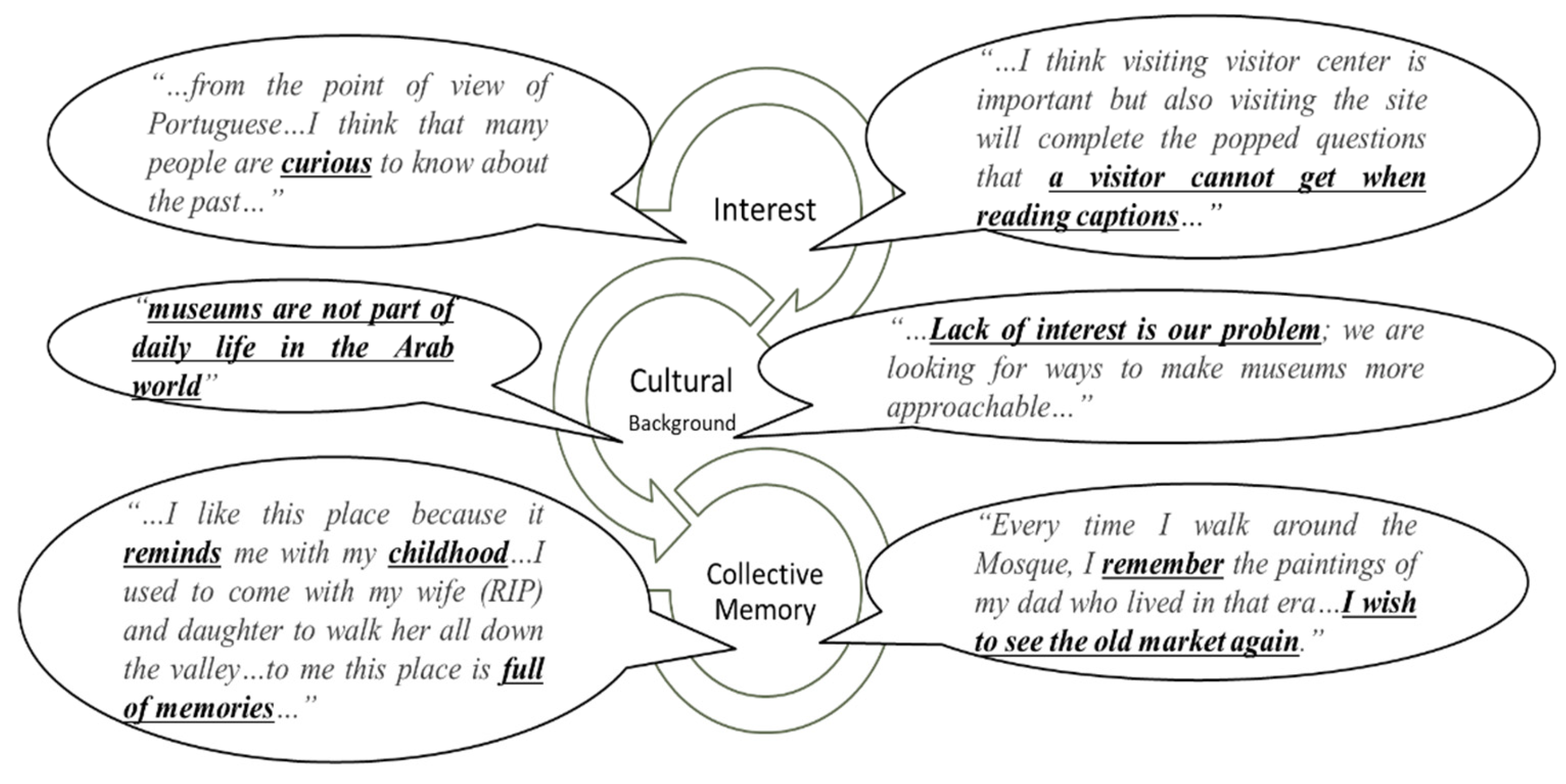

3.2.3. The Aspects of the Meaning-Making Process

3.2.4. Visitors’ Suggestions for Enhancing HSIC Experience

4. Discussion

4.1. Contribution of Historic Site Interpretation Centers to Meaning-Making

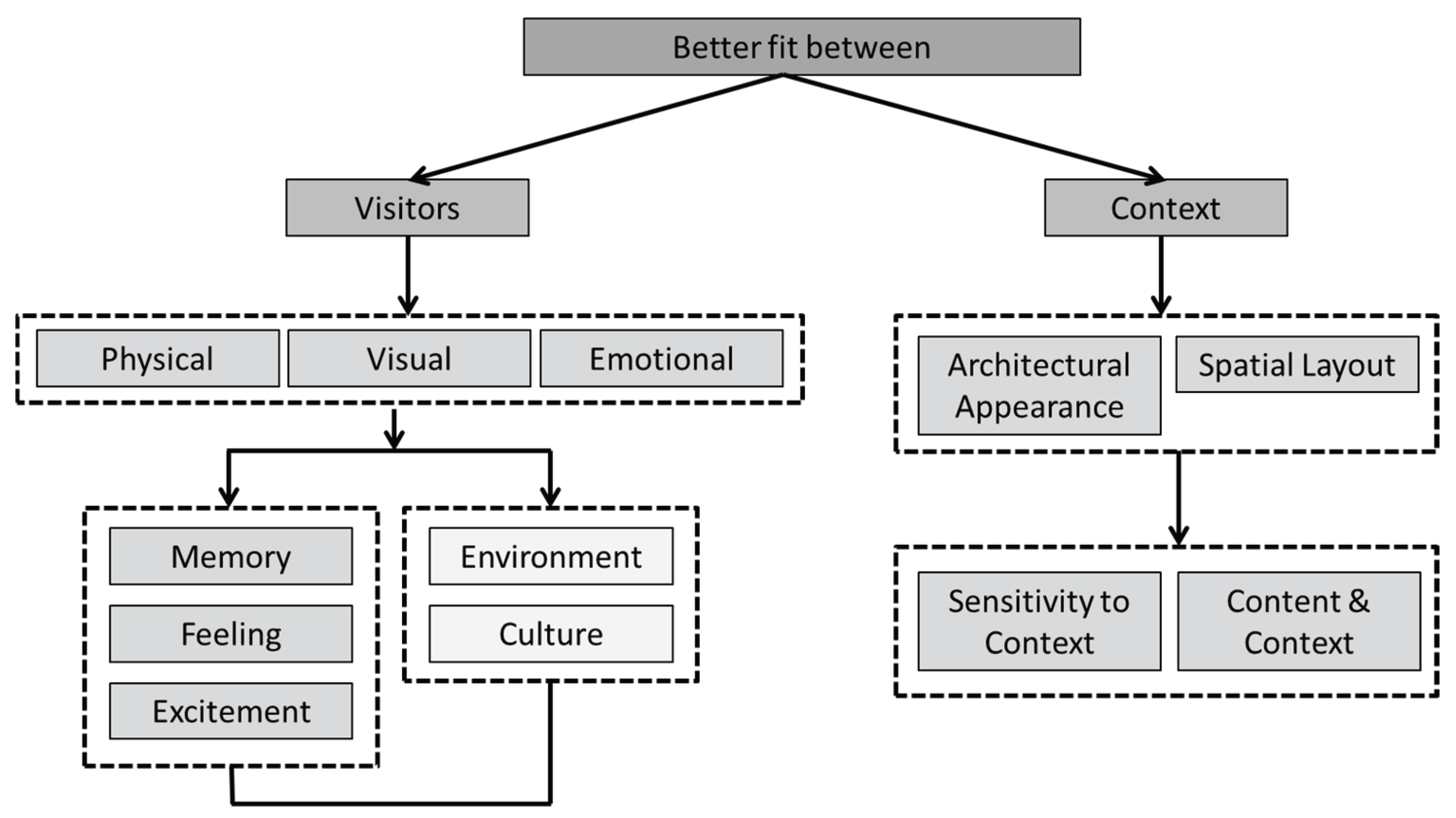

4.2. A Produced Model for Meaning Making and Visitor Experience at HSICs (VE-HSIC)

- Design HSICs with strong visual and narrative connect with their original sites, like using vantage points, sightlines to ruins, or incorporating local materials, to prevent decontextualization.

- Add some interactive elements to exhibits to make them more appealing to casual tourists and heritage enthusiasts, helping to boost their engagement and enjoyment.

- Incorporate local cultural elements like art, language, and stories, along with climate-sensitive features such as shaded outdoor areas. This approach, inspired by critical regionalism, helps create a more comfortable and meaningful experience for visitors.

- Balance “in situ” authenticity with “in context” interpretation by creating on-site experiences (living history, guided tours) that complement indoor exhibitions.

- This study examined four sites in Bahrain and may not cover all HSIC configurations, especially newer ones. Visitor responses mainly came from those interested in heritage, possibly biasing results toward more engaged visitors.

- Although the VE-HSIC model is based on local case studies, more research is needed to determine its applicability in other cultural or national settings. Future studies could apply this model in different regions or with larger sample sizes.

- Data were collected in 2018–2019; visitor behavior may change over time or due to external factors (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on museum visitation), which were not captured here.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSIC | Historic Site Interpretation Centers |

| UX | User Experience |

| UCD | User-Centered Design |

| VE-HSIC | Visitor Engagement Model at Historic Site Interpretation Centers |

References

- Falk, J. Museum audiences: A visitor-centered perspective. Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure 2016, 39, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tong, Y.; Zeng, H. Driving tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour through heritage interpretation messages. npj Heritage Science 2025, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E.; Smith, M.P.; Wilson, P.F.; Stott, J.; Williams, M.A. Creating Meaningful Museums: A Model for Museum Exhibition User Experience. Visitor Studies 2023, 26, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biln, J.; El Amrousi, M. Dubai's Museum Types: A Structural Analytic. Museum Worlds 2014, 2, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. Objects of Ethnography. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, Lavine, I.K.a.S.D., Ed. Smithsonian Institution Press.: Washington DC., 1991; pp. 386–443.

- Grant, R.; King, E.; Hubbard, E.-M.; Young, M.S. Think Human: exploring the exhibition of ergonomics to enhance education and engagement: establishing the CIEHF 75th anniversary exhibition. Ergonomics 2025, 68, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Conceptualizing the Visitor Experience: A Review of Literature and Development of a Multifaceted Model. Visitor Studies 2016, 19, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilden, F. Interpreting our heritage, Rev. ed. ed.; U. of North Carolina Pr.: [S.l.], 1967.

- Norman, D.A. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition.

- Law, E.L.-C.; Vermeeren, A.P.O.S.; Bevan, N. USER EXPERIENCE WHITE PAPER Bringing clarity to the concept of user experience.

- Hassenzahl, M. User experience (UX): towards an experiential perspective on product quality. In Proceedings of Interaction Homme-Machine.

- Hassenzahl, M. MARC HASSENZAHL CHAPTER 3 The Thing and I: Understanding the Relationship Between User and Product.

- Skydsgaard, M.A.; Møller Andersen, H.; King, H. Designing museum exhibits that facilitate visitor reflection and discussion. Museum Management and Curatorship 2016, 31, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H. Contextualizing Falk's Identity-Related Visitor Motivation Model. Visitor Studies 2011, 14, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.; Dierking, D.; Semmel, M. The Museum Experience Revisited; Taylor and Francis: Walnut Creek, UNITED STATES, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, L.H. Visitor Meaning-Making in Museums for a New Age. Curator: The Museum Journal 1995, 38, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhill, E.H. Changing Values in the Art Museum: rethinking communication and learning. International Journal of Heritage Studies 2000, 6, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, U. A theory of semiotics; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, Ind, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grondin, J. The hermeneutical circle. In The Blackwell Companion to Hermeneutics, First ed.; Keane, N., Lawn, C., Eds. Blackwell: Oxford, 2017. pp. 299–305. Available online: https://assets.thalia.media/doc/64/33/643313fb-895b-4811-b00a-37f8394ecf0b.pdf.

- Smith, L.; Wetherell, M.; Campbell, G. Emotion, affective practices and the past in the presentEmotion, Affective Practices, and the Past in the Present; 2018.

- Frankenberg, S.R. Regional/Site Museums. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, Smith, C., Ed. Springer New York: New York, NY, 2014. 6261–6264. [CrossRef]

- Recuero, N.; Gomez, J.; Blasco, M.F.; Figueiredo, J. Perceived relationship investment as a driver of loyalty: The case of Conimbriga Monographic Museum. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2019, 11, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, J. Museum Exhibition Space Analysis Based on Tracing Behavior Observation. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2013, 477-478, 1140–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F. Museum architecture as spatial storytelling of historical time: Manifesting a primary example of Jewish space in Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum. Frontiers of Architectural Research 2017, 6, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehari, A.G.; Asmeret, G.M.; Peter, R.S.; Bertram, B.M. Knowledge about archaeological field schools in Africa: the Tanzanian experience. Azania 2014, 49, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, B.I.; Osman, K.A. Toward a new vision to design a museum in historical places. HBRC Journal 2018, 14, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibiger, T. Global Display-Local Dismay. Debating 'Globalized Heritage' in Bahrain. History & Anthropology 2011, 22, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, R. The contextual linkage: visual metaphors and analogies in recent Gulf museums’ architecture. The Journal of Architecture 2022, 27, 372–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, A. Tour guides and heritage interpretation: guides’ interpretation of the past at the archaeological site of Jarash, Jordan. Journal of Heritage Tourism 2017, 13, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, A. The Site of Pella in Jordan: A Case Study for Developing Interpretive Strategies in an Archaeological Heritage Attraction. Near Eastern Archaeology 2018, 81, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saffar, M.; Tabet, A. Visitors Voice in Historic Sites Interpretation Centres in Bahrain. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 603, 052006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khalifa, H.E.; Jiwane, A.V. Visitors’ Interactions with the Exhibits and Behaviors in Museum Spaces: Insights from the National Museum of Bahrain. Buildings 2025. [Google Scholar]

- French, B.M. The Semiotics of Collective Memories. Annual Review of Anthropology 2012, 41, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, K.F.; Weiner, F.H. Collective Memory and the Museum. In Images, Representations and Heritage: Moving beyond Modern Approaches to Archaeology, Russell, I., Ed. Springer US: Boston, MA, 2006. 221–245. [CrossRef]

- Ansbacher, T. Making Sense of Experience: A Model for Meaning-Making. In Exhibitionist, Spring 2013, National Association for Museum Exhibition: American Alliance of Museums, 2013; pp 16-19.

- Creswell. Convergent Parallel Mixed Methods Design. In Research design : qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, Fourth edition, International student edition. ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, 2014; pp. 269–273.

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Research Design and Management. In Qualitative data analysis : a methods sourcebook, SAGE: Thousand Oaks, 2014; pp. 17–53.

- Hesse-Biber, S. Qualitative Approaches to Mixed Methods Practice. Qualitative Inquiry 2010, 16, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case study research: design and methods, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, Calif, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carter; Bryant-Lukosius, R. ; DiCenso, R.; Neville, J. The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research. Oncology Nursing Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell. Qualitative Methods. In Research design : qualitative, quantitative & mixed methods approaches, SAGE Publications Ltd.: The United States of America, 2014; pp. 231–262.

- Langmead, A.; Byers, D.; Morton, C. Curatorial Practice as Production of Visual and Spatial Knowledge: Panelists Respond. Contemporaneity 2015, 4, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L. Naturalistic and ethnographic research. In Research methods in education, 6th Edition ed.; Edition, t., Ed. Routledge: Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007; pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Graefe, A.; Mowen, A.; Covelli, E.; Trauntvein, N. Recreation Participation and Conservation Attitudes: Differences Between Mail and Online Respondents in a Mixed-Mode Survey. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 2011, 16, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R.; Sommer, B.B. A practical guide to behavioral research: tools and techniques; Oxford University Press: 2002.

- Bitgood, S. Attention and value : keys to understanding museum visitors. Left Coast Press, Inc.: Walnut Creek, California, 2013.

- Brida, J.G.; Meleddu, M.; Pulina, M. Understanding museum visitors' experience: a comparative study. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 2016, 6, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.R.; Burnett, D.O.; Kendrick, O.W.; Macrina, D.M.; Snyder, S.W.; Roy, J.P.L.; Stephens, B.C. Developing Valid and Reliable Online Survey Instruments Using Commercial Software Programs. Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet 2009, 13, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, D.K.; Paterson, S. A comparison of data collection methods: Mail versus online surveys. Journal of Leisure Research 2018, 49, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L. Questionnaires: Piloting the Questionnaire. In Research methods in education, 4th ed. ed.; Routhledge: London ;, 1994; pp. 341–342.

- Musante, K.; DeWalt, B.R. Designing Research with Participant Observation. In Participant Observation. In Participant Observation : A Guide for Fieldworkers, 2nd ed.; AltaMira Press: Blue Ridge Summit, UNITED STATES, 2010; pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Analyzing Interviews. In Doing Interviews, Flick, U., Ed. SAGE: London, 2007. 101–119. [CrossRef]

- DiCicco-Bloom, B.; Crabtree, B.F. The qualitative research interview. Medical Education 2006, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J.; Leavy, P.; Beretvas, N. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research; Oxford University Press USA - OSO: Cary, UNITED STATES, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Falco, F.; Vassos, S. Museum Experience Design: A Modern Storytelling Methodology. The Design Journal 2017, 20, S3975–S3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexner, J.L. Archaeology and Ethnographic Collections: Disentangling Provenance, Provenience, and Context in Vanuatu Assemblages. Museum Worlds 2016, 4, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani Dastgerdi, A.; De Luca, G. Specifying the Significance of Historic Sites in Heritage Planning. Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage 2019, 18, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricœur, P. Metaphor and Symbol. In Interpretation theory : discourse and the surplus of meaning, Texas Christian University Press: Fort Worth, 1976; p. 107 (p.155).

- Barry, M.M.; Robert, C.R. On making meanings: Curators, social assembly, and mashups. Strategic Organization 2015, 13, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.A. Managing Heritage Site Interpretation for Older Adult Visitors. Symphonya 2016, 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis, K. A visit to the Acropolis Museum. In Museum History, Arvanitakis, K., Ed. YouTube, 2010; p www.theacropolismuseum.gr.

- Caskey, M. Perceptions of the New Acropolis Museums. In American Journal of Archaeology Online Museum Review, Archaeological Institute of America: America, 2011; p 10.

- Lending, M. Negotiating absence: Bernard Tschumi’s new Acropolis Museum in Athens. The Journal of Architecture 2018, 23, 797–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jashari-Kajtazi, T.; Jakupi, A. Interpretation of architectural identity through landmark architecture: The case of Prishtina, Kosovo from the 1970s to the 1980s. Frontiers of Architectural Research 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, A.; Coyne, R. Interpretation in architecture: Design as a way of thinking Routledge: USA and Canada, 2006; pp. 332.

- Rémi, M.; Séverine, M.; Mathilde, P. Museums, consumers, and on-site experiences. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 2010, 28, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaughey, D.R. Ricoeur's Metaphor and Narrative Theories as a Foundation for a Theory of Symbol. Religious Studies 1988, 24, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M.; Bröcker-Oltmanns, K. Ontologie: (Hermeneutik der Faktizität); V. Klostermann: 1995.

- Frampton, K. Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance. In The anti-aesthetic: essays on postmodern culture, Foster, H., Ed. New Press: New York, 1998; pp. 17–34.

- Patteeuw, V.r. and L.a.‐C. Szacka. Critical Regionalism for our time. The Architectural Review 2019 10 July 2020]; 1st Edition:[92].

| Site Name | Site Typology | Interpretation Mode | Notable Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case Study #1 Al Khamis Mosque Visitor Center |

Religious heritage | In situ | Interpretation via a glass floor over ruins |

| Case Study #2 Qal’at Al Bahrain Site Museum |

UNESCO site | In situ + In context | Major archaeological fort with panoramic museum view |

| Case Study #3 Shaikh Salman bin Ahmed Al Fateh Fort (Riffa Fort) |

Restored fort | In context | Dual-function cultural center with scenic terrace |

| Case Study #4 Bu Maher Fort Visitor Center |

Reconstructed fort | In situ + water-based link | Linked by boat shuttle to Pearling Trail |

| Method | Qal’at Al Bahrain | Riffa Fort | Bu Maher Fort | Al Khamis Mosque |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveys (n = 113 total) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Interviews (n = 22) |

7 participants | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| Observation (50+ hours) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Archival Analysis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).