1. Introduction

The rapid success of transformer-based AI systems presents an evolutionary puzzle in reverse: how can sophisticated cognitive behaviors emerge from relatively simple architectural changes? Current LLMs achieve human-level performance in many cognitive domains through scaled attention mechanisms operating over vast linguistic datasets (Brown et al., 2020; Bubeck et al., 2023). Critically, these systems were not explicitly programmed for the cognitive abilities they display—these abilities emerged from the interaction between architecture and data, consistent with theories of emergent intelligence (Anderson, 1972; Holland, 1998).

This observation suggests a testable hypothesis for human cognitive evolution that builds upon established theories of gene-culture coevolution (Boyd & Richerson, 1985) and the Baldwin effect (Baldwin, 1896; Weber & Depew, 2003): human cognitive superiority emerged from emergent properties arising when increasingly sophisticated neural attention mechanisms began operating over an expanding base of symbolic information (language), facilitated by key genetic innovations that enabled symbolic processing.

Our hypothesis extends recent work on the cultural brain hypothesis (Herrmann et al., 2007; Henrich, 2016) by proposing specific computational mechanisms underlying the language-cognition interface, informed by advances in artificial intelligence architectures. Importantly, we use AI systems as heuristic tools for hypothesis generation rather than claiming direct equivalence between artificial and biological cognitive processes.

2. The Knowledge-As-Cognition Hypothesis

2.1 Language as Crystallized Cognition

Human language, particularly in its written form, represents more than mere information storage—it constitutes crystallized patterns of human thought, consistent with Vygotsky’s theory of language as a psychological tool (Vygotsky, 1978) and modern theories of extended cognition (Clark & Chalmers, 1998). Consider this thought experiment: if an alien civilization downloaded the entire human internet without ever observing humans directly, the billions of words would contain not just facts about our world, but embedded patterns of human reasoning, argumentation, problem-solving strategies, and conceptual associations.

This “cognitive crystallization” operates through two distinct but interconnected mechanisms. First, language preserves structural patterns of reasoning—the logical templates, syntactic frameworks, and inferential architectures that characterize human thought processes. Second, beyond these formal structures, language captures emergent semantic relationships and conceptual mappings that arise from the interaction between structural patterns and world knowledge. These mechanisms work together to embed not merely statistical regularities but functional cognitive strategies within linguistic representations.

This dual-mechanism framework provides a potential explanation for why LLMs trained solely on text can exhibit sophisticated reasoning (Wei et al., 2022): the training data contains both logical structures and semantic patterns that can be extracted through statistical pattern matching, supporting theories of language as a repository of cultural intelligence (Pinker, 1994; Tomasello, 1999). However, we emphasize that the statistical emergence in LLMs differs fundamentally from biological cognitive development, serving here as an analogical framework rather than a direct model.

2.2. The Co-Evolutionary Dynamic

We propose that human cognitive evolution involved a positive feedback loop consistent with gene-culture coevolution theory (Laland et al., 2010) and the Baldwin effect (Dennett, 2003), facilitated by genetic innovations such as FOXP2 and human accelerated regions (HARs) that enabled symbolic processing (Fisher et al., 1998; Pollard et al., 2006):

Genetic changes enabled basic symbolic communication capacity

Early symbolic communication created the first “knowledge base” of shared meanings

Neural mechanisms evolved to process this symbolic information more effectively

Enhanced processing enabled more sophisticated symbolic systems

Richer symbolic systems created evolutionary pressure for better processing mechanisms

This dynamic explains how genetic enablers combined with cultural evolution could yield dramatic cognitive leaps—the real driver was the interaction between genetic capacity for symbolic processing and the emergent properties of scaled symbolic systems, consistent with theories of cognitive niche construction (Sterelny, 2003; Laland & Brown, 2011).

3. Neurobiological Parallels

3.1 Attention Mechanisms in the Brain

The transformer architecture’s core innovation—multi-headed attention (Vaswani et al., 2017)—provides a computational analogy for understanding human language processing. The dynamic connectivity between Wernicke’s area (comprehension) and Broca’s area (production) exhibits selective attention to semantic and syntactic features that functionally resembles attention patterns in transformer models (Friederici, 2011; Hasson et al., 2018).

Recent neuroimaging studies support this parallel: Schrimpf et al. (2021) demonstrated that transformer models predict neural responses in language areas with unprecedented accuracy, suggesting convergent computational solutions. Similarly, Goldstein et al. (2022) found that attention patterns in large language models correspond to known neural pathways involved in syntactic and semantic processing.

Testable prediction: Human language areas should show attention-like activation patterns when processing complex linguistic structures, with different neural populations specializing in different linguistic features (syntax, semantics, pragmatics), measurable through high-resolution fMRI and advanced connectivity analysis.

3.2. The Neural-Symbolic Interface

Unlike current AI systems that process discrete tokens, biological systems must bridge continuous neural activity and functionally discrete symbolic representations. Following theories of neural-symbolic integration (Smolensky, 1988; Marcus, 2001; Fodor & Pylyshyn, 1988), we hypothesize that this interface—the capacity to map continuous neural states onto functionally discrete representational categories (such as lexical items or conceptual structures)—was a key evolutionary innovation.

This interface should not be understood as formal symbolic computation in the classical AI sense, but rather as the biological capacity to create functionally discrete, combinatorially structured representations from continuous neural activity (Jackendoff, 2002). Once this neural-symbolic mapping capacity evolved, expanding symbolic complexity could drive cognitive sophistication through cultural rather than genetic evolution, supporting the cultural brain hypothesis (Herrmann et al., 2007).

4. Implications and Predictions

4.1 For Cognitive Evolution

Building on established theories of human cognitive evolution (Dunbar, 1998; Mithen, 2005), our hypothesis predicts a nuanced view of genetic versus cultural contributions:

● Gene-culture interaction: Major cognitive advances required specific genetic enablers (such as FOXP2, HARs) that permitted symbolic processing, which then amplified through cultural evolution (Laland et al., 2010; Somel et al., 2009)

● Cultural acceleration: Once neural-symbolic interfaces evolved, cultural evolution could drive cognitive sophistication faster than genetic evolution, supporting dual inheritance theory (Richerson & Boyd, 2005)

● Critical mass effects: Cognitive abilities should show threshold effects rather than gradual improvements, consistent with phase transition models of cultural evolution (Henrich, 2016)

4.2. For AI Development

Our framework suggests several implications for artificial intelligence development, while acknowledging the fundamental differences between statistical pattern extraction and biological cognition:

● Data quality over quantity: The “cognitive content” of training data may matter more than raw volume, consistent with recent findings on data curation effects (Gadre et al., 2023)

● Architecture efficiency: Modest architectural improvements operating over rich symbolic bases can yield disproportionate cognitive gains

● Emergence predictability: Cognitive abilities should be more predictable from the interaction of architecture and data patterns, supporting scaling law research (Kaplan et al., 2020)

4.3. For Consciousness Studies

While large language models (LLMs) demonstrate impressive symbolic reasoning capabilities, they often lack long-term coherence during autonomous operation. This limitation raises a deeper question: what mechanisms enable humans to maintain cognitive stability over time, especially under uncertainty or cognitive load? Building on prior discussions of symbolic emergence and consciousness, this section explores the hypothesis that conscious access may serve a metacognitive regulatory function—constraining semantic drift and stabilizing reasoning in ways not yet achievable by current AI systems.

This hypothesis maintains a crucial distinction consistent with contemporary philosophy of mind (Chalmers, 1995; Block, 2007): cognitive abilities and consciousness are orthogonal dimensions. AI systems demonstrate that sophisticated pattern-based cognition can exist without subjective experience, suggesting consciousness involves different mechanisms than those driving cognitive sophistication (Chalmers, 2023).

This framework represents what we term “symbolic-only cognition”—sophisticated information processing divorced from sensorimotor experience and phenomenal consciousness. This contrasts with theories of embodied and enactive cognition (Varela et al., 1991; Thompson, 2007) that emphasize the role of bodily experience in shaping cognitive processes. Our hypothesis suggests that while embodied experience may be crucial for phenomenal consciousness and certain forms of understanding, the core mechanisms of symbolic reasoning can operate independently of such embodiment.

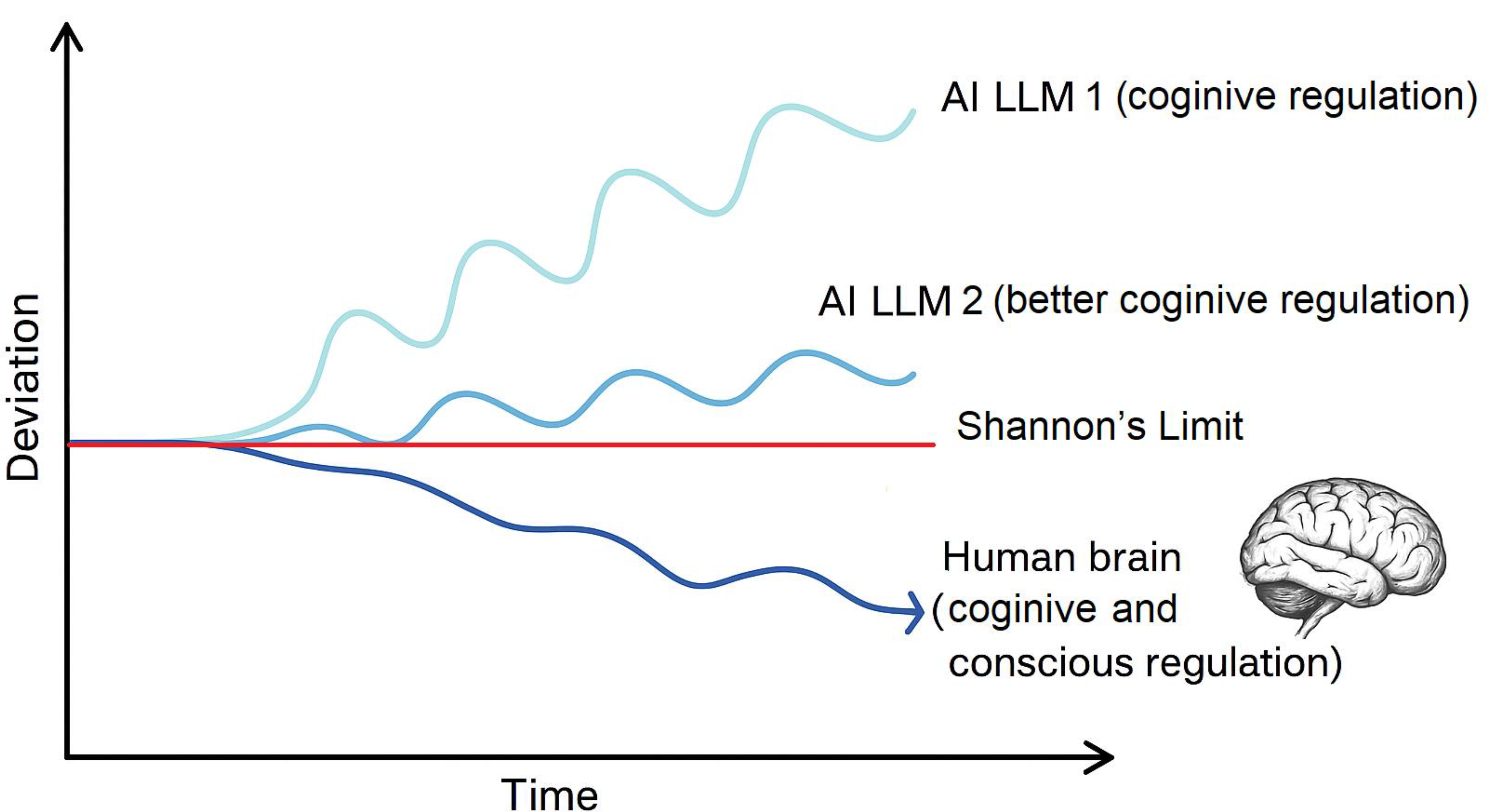

4.4. Cognitive Regulation vs. Conscious Regulation

Large language models (LLMs) often produce coherent outputs in early stages of autonomous reasoning, but tend to drift semantically over time—accumulating inconsistencies and factual errors. This phenomenon, known as cognitive drift, reflects the absence of higher-order regulatory mechanisms. Recent studies have quantified this effect: Li et al. (2024) demonstrated that LLMs exposed to iterative misinformation show rising perplexity and a 1–2% drop in accuracy per cycle, while Zhang et al. (2025) revealed that self-referential chain-of-thought reasoning leads to latent semantic divergence, with smaller models drifting more rapidly. In contrast, human reasoning—measured via verbal protocols—exhibits minimal drift, stabilized through metacognitive correction (Dehaene, 2014).

We hypothesize that conscious access serves as a regulatory integrator, enabling humans to detect and correct semantic instability. This regulation likely involves confidence monitoring, inhibitory control over implausible continuations, and cross-modal verification through imagery, memory, and sensorimotor feedback. Such mechanisms constrain drift and preserve coherence across extended reasoning episodes.

This view aligns with Friston’s free-energy principle, which posits that biological systems minimize surprise by continuously updating internal models to reduce prediction error (Friston, 2010). We predict that during chain-of-thought reasoning, fMRI activation in the frontoparietal network should correlate with reduced semantic drift (quantified via embedding distance) in humans, but not in LLM simulations lacking conscious regulation.

This distinction suggests that while symbolic cognition can emerge from scaled pattern extraction, stable autonomous cognition may require regulatory mechanisms beyond current computational architectures—potentially involving conscious integration and error correction unavailable to present-day AI systems (see

Figure 1 for comparative trajectories).

Shannon’s Limit and possible Fundamental Asymmetry: Despite architectural advances, a fundamental ceiling remains. According to Shannon’s information theory, no artificial system can extract more information than is present in its input—regardless of processing sophistication (Shannon, 1948). It is possible that this limitation remains valid for AI systems, especially if they are to work autonomously for a long time without errors and hallucinations. While they may reduce hallucinations and improve coherence, they may not be able to generate truly new knowledge beyond their training corpus.

Empirical studies reinforce this possible constraint. Li et al. (2024) showed that LLMs exposed to iterative misinformation exhibit rising perplexity and compounding errors, while Zhang et al. (2025) quantified semantic drift in self-referential reasoning chains, with smaller models diverging more rapidly. These findings illustrate that statistical cognition alone cannot sustain long-term coherence under uncertainty.

In contrast, human cognition appears to deviate from this ceiling—not through greater data volume, but via conscious integration. Consciousness may serve as a metacognitive regulator, enabling insight beyond statistical recombination by stabilizing thought and constraining drift. For a deeper exploration of Shannon’s Data Processing Inequality and its implications for generative model training, see Straňák (2025).

The following

Table 1 summarizes the regulatory mechanisms and drift patterns observed in basic and advanced LLMs compared to human cognition. It complements

Figure 1 by highlighting the structural differences underlying cognitive stability across systems.

5. Testable Hypotheses

Our framework generates several empirically testable predictions:

1. Linguistic archaeology: Human cognitive capabilities should correlate with the complexity of available symbolic systems across cultures and historical periods, testable through cross-cultural cognitive assessment and historical linguistic analysis

2. Neural attention: Language processing should show measurable attention-like mechanisms comparable to transformer architectures, testable through advanced neuroimaging and computational modeling

3. Developmental prediction: Children’s cognitive development should correlate with their mastery of increasingly complex symbolic systems, controlling for general neural maturation

4. Cross-species comparison: Species with richer symbolic communication systems should show enhanced cognitive flexibility, testable through comparative cognition research

5. Genetic markers: Populations with different versions of language-related genes (FOXP2 variants, HAR differences) should show predictable differences in symbolic processing efficiency

Table 2 presents the core hypotheses and corresponding methods derived from the knowledge-as-cognition framework, complementing the preceding list.

6. Discussion and Limitations

6.1. AI-Biology Analogies: Limitations and Utility

We acknowledge fundamental limitations in drawing analogies between artificial and biological systems. LLM “emergence” represents statistical pattern extraction from training data, fundamentally different from biological evolution and development. These systems lack the sensorimotor grounding, social interaction, and developmental plasticity that characterize human cognition (Bender & Koller, 2020; Marcus, 2022).

Critics argue that our approach conflates statistical regularities with genuine cognitive mechanisms. Berwick & Chomsky (2016) contend that language acquisition relies on innate syntactic principles rather than cultural emergence from statistical patterns. Similarly, Hassabis et al. (2017) demonstrate that current LLMs lack robust compositional generalization—the ability to systematically combine familiar elements in novel ways—which may be fundamental to human cognition. These critiques highlight the need for careful distinction between surface-level behavioral similarities and underlying computational mechanisms.

However, AI systems serve as valuable heuristic tools for generating hypotheses about biological cognition. The computational success of attention mechanisms in processing linguistic data suggests that similar principles might underlie biological language processing, even if implemented through entirely different mechanisms. We emphasize that our framework uses AI insights for hypothesis generation rather than claiming direct mechanistic equivalence.

6.2. The Role of Embodiment

Our focus on symbolic processing should not be interpreted as dismissing the importance of embodied cognition (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999; Barsalou, 2008). Rather, we propose a division of cognitive labor: embodied experience may be crucial for phenomenal consciousness, qualia, and certain forms of conceptual grounding, while symbolic processing mechanisms can operate relatively independently to enable sophisticated reasoning and problem-solving.

This division helps explain how AI systems can achieve impressive cognitive performance in symbolic domains while lacking the kind of understanding that emerges from embodied experience. It also suggests that human cognitive superiority may result from the integration of both embodied and symbolic processing systems.

6.3. Genetic Contributions and Cultural Evolution

Our emphasis on cultural acceleration should not minimize the importance of genetic innovations in human cognitive evolution. Rather, we propose that key genetic changes (such as those affecting FOXP2, microcephalin, and ASPM genes) created the neural prerequisites for symbolic processing, which then enabled rapid cultural-cognitive coevolution (Evans et al., 2005; Mekel-Bobrov et al., 2005).

This perspective reconciles genetic and cultural approaches to human cognitive evolution: genetic changes were necessary but not sufficient for human cognitive superiority. The crucial innovation was the capacity for neural-symbolic mapping, which then allowed cultural evolution to drive cognitive sophistication at unprecedented speeds.

6.4. Future Directions

Future research should focus on: (1) developing more precise computational models of neural-symbolic interfaces in biological systems, (2) testing our predictions through cross-cultural and developmental studies, (3) investigating the genetic basis of symbolic processing capacity, and (4) exploring the implications for AI safety and alignment as these systems become more cognitively sophisticated while remaining fundamentally different from biological intelligence.

7. Conclusion

The emergence of sophisticated cognition in AI systems suggests that human cognitive evolution may have followed a similar pattern: genetic innovations enabling symbolic processing, amplified by rich cultural substrates. This hypothesis repositions language from a mere communication tool to a crystallized substrate of cognition—capable of sustaining emergent reasoning in both biological and artificial systems.

Yet a fundamental asymmetry remains. While artificial systems can approach the informational ceiling defined by Shannon’s limit, they cannot exceed it. Their cognition is bounded by input; novelty is statistical, not fundamental. In contrast, human cognition exhibits a paradoxical deviation from this ceiling—enabled not by data volume, but by conscious regulation. Consciousness may serve as a metacognitive integrator, stabilizing thought, constraining drift, and enabling insight beyond the sum of inputs.

This distinction reframes the architecture of intelligence. Symbolic reasoning can emerge from scaled pattern extraction, but autonomous cognition—coherent, adaptive, and creative—may require conscious integration. Whether artificial systems can ever cross this threshold remains uncertain. But recognizing the boundary between symbolic-only cognition processing and embodied conscious experience may be key to understanding both human cognitive evolution and the future trajectory of artificial intelligence.

This work offers a roadmap for evolutionary cognitive science in the age of AI: using artificial systems to generate testable biological hypotheses, while respecting the fundamental differences in their implementation.

8. Take-Home messages

Language as crystallized cognition Human language encodes not just information, but structured patterns of reasoning—making it a substrate for emergent cognition in both biological and artificial systems.

Co-evolutionary dynamic Human cognitive superiority likely emerged through feedback between genetic enablers of symbolic processing and culturally expanding symbolic systems.

AI as heuristic, not equivalent Large language models exhibit emergent cognition via statistical pattern extraction, but lack the embodied and conscious dimensions that characterize human intelligence.

Cognition vs. consciousness Cognition can be computationally realized; consciousness may serve a distinct regulatory function—stabilizing thought, constraining drift, and enabling insight beyond input.

Open frontier The path to fully autonomous general AI remains uncertain. Understanding the interplay between symbolic reasoning and conscious regulation is crucial for both evolutionary biology and AI development.

Funding

This research received no external funding. It was undertaken solely due to the author’s personal interest and initiative.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. This manuscript presents a theoretical reflection and does not include empirical datasets.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that no competing interests exist.

References

- Anderson, P. W. (1972). More is different. Science, 177(4047), 393–396. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.177.4047.393.

- Baldwin, J. M. (1896). A new factor in evolution. The American Naturalist, 30(354), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1086/276408.

- Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617–645. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639.

- Bender, E. M., & Koller, A. (2020). Climbing towards NLU: On meaning, form, and understanding in the age of data. Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 5185–5198. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.463.

- Berwick, R. C., & Chomsky, N. (2016). Why only us: Language and evolution. MIT Press.

- Block, N. (2007). Consciousness, accessibility, and the mesh between psychology and neuroscience. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30(5–6), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X07002786.

- Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (1985). Culture and the evolutionary process. University of Chicago Press.

- Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J. D., Dhariwal, P., … Amodei, D. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 1877–1901.

- Bubeck, S., Chandrasekaran, V., Eldan, R., Gehrke, J., Horvitz, E., Kamar, E., … Zhang, Y. (2023). Sparks of artificial general intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.12712. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.12712.

- Chalmers, D. J. (1995). Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2(3), 200–219.

- Chalmers, D. J. (1996). The conscious mind: In search of a fundamental theory. Oxford University Press.

- Chalmers, D. J. (2023, October 16). Minds of machines: The great AI consciousness conundrum. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/10/16/1081149/ai-consciousness-conundrum/.

- Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/58.1.7.

- Dehaene, S. (2002). The cognitive neuroscience of consciousness. MIT Press.

- Dehaene, S. (2014). Consciousness and the brain: Deciphering how the brain codes our thoughts. Viking Press.

- Dennett, D. C. (2003). The Baldwin effect: A crane, not a skyhook. In B. H. Weber & D. J. Depew (Eds.), Evolution and learning: The Baldwin effect reconsidered (pp. 60–79). MIT Press.

- Dunbar, R. I. M. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology, 6(5), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:5<178::AID-EVAN5>3.0.CO;2-8.

- Evans, P. D., Gilbert, S. L., Mekel-Bobrov, N., Vallender, E. J., Anderson, J. R., Vaez-Azizi, L. M., … Lahn, B. T. (2005). Microcephalin, a gene regulating brain size, continues to evolve adaptively in humans. Science, 309(5741), 1717–1720. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1113722.

- Fastowski, A., et al. (2024). Understanding knowledge drift in LLMs through misinformation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.07085. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.07085.

- Fisher, S. E., Vargha-Khadem, F., Watkins, K. E., Monaco, A. P., & Pembrey, M. E. (1998). Localisation of a gene implicated in a severe speech and language disorder. Nature Genetics, 18(2), 168–170. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng0298-168.

- Fodor, J. A., & Pylyshyn, Z. W. (1988). Connectionism and cognitive architecture: A critical analysis. Cognition, 28(1–2), 3–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(88)90007-7.

- Friederici, A. D. (2011). The brain basis of language processing: From structure to function. Physiological Reviews, 91(4), 1357–1392. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00006.2011.

- Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787.

- Gadre, S. Y., Ilharco, G., Frankle, J., Shanahan, M., Xie, S. M., Kusupati, A., … Schmidt, L. (2023). DataComp: In search of the next generation of multimodal datasets. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.14108.

- Goldstein, A., Zada, Z., Buchnik, E., Schain, M., Price, A., Aubrey, B., … Hasson, U. (2022). Shared computational principles for language processing in humans and deep language models. Nature Neuroscience, 25(3), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-022-01026-4.

- Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D., Summerfield, C., & Botvinick, M. (2017). Neuroscience-inspired artificial intelligence. Neuron, 95(2), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.011.

- Hasson, U., Egidi, G., Marelli, M., & Willems, R. M. (2018). Grounding the neurobiology of language in first principles. Cognition, 180, 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.018.

- Henrich, J. (2016). The secret of our success: How culture is driving human evolution, domesticating our species, and making us smarter. Princeton University Press.

- Herrmann, E., Call, J., Hernández-Lloreda, M. V., Hare, B., & Tomasello, M. (2007). Humans have evolved specialized skills of social cognition: The cultural intelligence hypothesis. Science, 317(5843), 1360–1366. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1146282.

- Holland, J. H. (1998). Emergence: From chaos to order. Perseus Publishing.

- Jackendoff, R. (2002). Foundations of language: Brain, meaning, grammar, evolution. Oxford University Press.

- Kaplan, J., McCandlish, S., Henighan, T., Brown, T. B., Chess, B., Child, R., … Amodei, D. (2020). Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. University of Chicago Press.

- Laland, K. N., & Brown, G. R. (2011). Sense and nonsense: Evolutionary perspectives on human behaviour. Oxford University Press.

- Laland, K. N., Odling-Smee, J., & Myles, S. (2010). How culture shaped the human genome: Bringing genetics and the human sciences together. Nature Reviews Genetics, 11(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2734.

- Lu, W., & Friston, K. (2024). Bayesian brain computing and the free-energy principle. National Science Review, 11(5), nwae025. https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwae025.

- Marcus, G. F. (2001). The algebraic mind: Integrating connectionism and cognitive science. MIT Press.

- Marcus, G. F. (2022). Deep learning: A critical appraisal. Communications of the ACM, 65(1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1145/3448250.

- Mekel-Bobrov, N., Gilbert, S. L., Evans, P. D., Vallender, E. J., Anderson, J. R., Hudson, R. R., … Lahn, B. T. (2005). Ongoing adaptive evolution of ASPM, a brain size determinant in Homo sapiens. Science, 309(5741), 1720–1722. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1116815.

- Mithen, S. (2005). The singing Neanderthals: The origins of music, language, mind, and body. Harvard University Press.

- Pinker, S. (1994). The language instinct: How the mind creates language. William Morrow and Company.

- Pollard, K. S., Salama, S. R., Lambert, N., Lambot, M. A., Coppens, S., Pedersen, J. S., … Haussler, D. (2006). An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans. Nature, 443(7108), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05113.

- Richerson, P. J., & Boyd, R. (2005). Not by genes alone: How culture transformed human evolution. University of Chicago Press.

- Schrimpf, M., Blank, I. A., Tuckute, G., Kauf, C., Hosseini, E. A., Kanwisher, N., … Fedorenko, E. (2021). The neural architecture of language: Integrative modeling converges on predictive processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(45), e2105646118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2105646118.

- Smolensky, P. (1988). On the proper treatment of connectionism. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 11(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00052432.

- Somel, M., Liu, X., Tang, L., Yan, Z., Hu, H., Guo, S., … Khaitovich, P. (2009). MicroRNA-driven developmental remodeling in the brain distinguishes humans from other primates. PLoS Biology, 7(12), e1000271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000271.

- Straňák, P. (2025). Lossy Loops: Shannon’s DPI and Information Decay in Generative Model Training. Preprints. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202507.2260.v1.

- Sterelny, K. (2003). Thought in a hostile world: The evolution of human cognition. Blackwell Publishing.

- Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in life: Biology, phenomenology, and the sciences of mind. Harvard University Press.

- Tomasello, M. (1999). The cultural origins of human cognition. Harvard University Press.

- Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. MIT Press.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., … Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30, 5998–6008.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Weber, B. H., & Depew, D. J. (Eds.). (2003). Evolution and learning: The Baldwin effect reconsidered. MIT Press.

- Weatherstone, C. et al. (2025). Quantifying latent semantic drift in large language models through self-referential inference chains. ResearchGate Preprint. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.21584.62729.

- Wei, J., Tay, Y., Bommasani, R., Raffel, C., Zoph, B., Borgeaud, S., ... & Fedus, W. (2022). Emergent abilities of large language models. Transactions on Machine Learning Research. https://doi.org/10.1162/tmlr_a_00109.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).