Introduction

Plants interact with a wide range of organisms, from beneficial symbionts to detrimental herbivores. Among beneficial symbionts, arbuscular mycorrhiza (AM) are well known for enhancing plant nutrient uptake and shaping multitrophic interactions. Beyond promoting plant growth through improved nutrient availability, AM also modulate plant responses to herbivory via complex physiological, molecular, and biochemical pathways (Sharma et al., 2017; Tao et al., 2016). These interactions can be broadly grouped into two processes: (i) direct competition, in which AM fungi (AMF) and herbivores compete for plant-derived nutrients and ecological niches, and (ii) indirect effects, including induced systemic resistance, damage compensation, enhanced tolerance, and changes in root exudate profiles (Wieczorek and Bell, 2025).

Among these direct and indirect effects, resource availability plays a critical role in shaping the mycorrhizal communities, plant defense response and herbivore dynamics. For instance, the carbon (C)-for-nutrient exchange between host plants and AM symbionts can be disrupted by herbivores (Magkourilou et al., 2025). The extent to which plant-herbivore interactions modulate AM fungal assembly remains an ongoing debate. As for this, two principal hypotheses have been proposed (Frew et al., 2024). The carbon constraint hypothesis puts forth that reduced C availability caused by herbivory limits plant investment into mycorrhizal symbiosis, thereby altering AM fungal assembly. In contrast, the defense-directed hypothesis proposes that AM fungal community assembly is governed by induced plant defense pathways rather than C limitation alone. These hypotheses underscore the importance of nutrient flow in determining plant defense strategies. Nutrients acquired via AM symbiosis contribute to synthesizing defense compounds, and plants might prioritize resistance-based strategy. Conversely, depending on herbivory load, nutrient allocation can accelerate plant vegetative growth, encouraging plants to adopt tolerance-based strategy. Additionally, the effect of herbivory on plant nutrient distribution varies with feeding mode. Chewing herbivores remove plant tissues thus disrupting nutrient assimilation, while piercing and sucking herbivores extract phloem sap, thereby affecting vascular nutrient transport. Therefore, we anticipate that nutrients are a key factor in mycorrhiza-mediated multitrophic interactions.

To review studies of AG-BG interactions involving plants, herbivores and mycorrhiza, we conducted a literature search in the Web of Science database (July 29, 2025) using three keyword combinations: (1) “belowground” AND “plant” AND “herbivor*” AND “mycorrhiz*”; (2) “aboveground” AND “plant” AND “herbivor*” AND “mycorrhiz*”; and (3) “aboveground” AND “belowground” AND “plant” AND “herbivor*” AND “mycorrhiz*”. These searches yielded 237, 225, and 151 articles, respectively. This indicates that studies explicitly addressing combined AG–BG herbivory in plant–mycorrhizal interactions remain relatively scarce compared to studies focusing on either AG or BG herbivory alone. In the following sections, we highlight three key aspects of nutrient allocation in mycorrhizal-plant-herbivore interactions: (1) belowground herbivory, (2) aboveground herbivory, and (3) whole-plant herbivory.

1. Nutrient Flow in Mycorrhizal-Plant-Belowground Herbivore Interactions

1.1. Mechanisms of AMF-Mediated Nutrient Uptake

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi form widespread symbiotic associations with the roots of more than 80% of terrestrial plant species (Smith and Read, 2010). These associations substantially extend the functional rooting zone and enhance the host's access to soil nutrients. Within the root cortex, AMF develop finely branched arbuscules that act as specialized sites for nutrient exchange (Konvalinková et al., 2017). Fixed C by photosynthesis is delivered as carbohydrates from the host to the fungi which, in return, supply phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), and other essential nutrients to the plants. These mutualistic associations underpin plant nutritional balance and form a key interface for bi-directional resource exchange in the rhizosphere. Through extraradical hyphal networks, AMF extend their nutrient acquisition pathways with which plant roots connect with surrounding soil resources (Smith and Read, 2010). Understanding the mechanisms by which AM regulates nutrient flow is therefore central to disentangling how mycorrhizal symbioses interact with belowground herbivores, and shape plant adaptive strategies in complex soil environments.

1.2. Disturbance of Root Systems by Belowground Herbivores

Belowground herbivores, including root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.), scarab beetle larvae (e.g. white grubs), root maggots, and mole crickets, feed on the subterranean organs of plants and act as significant biotic stressors that directly impair root functioning. These herbivores employ piercing-sucking or chewing means to disrupt root architecture, impair nutrient and water uptake, and ultimately reduce primary productivity. Within mycorrhizal systems, such herbivore-induced root disturbances not only alter host plant physiology but can also destabilize AM colonization, nutrient provisioning, and extraradical hyphal network integrity, thereby compromising the mutualistic balance.

One key mechanism involves the physical disruption of root tissues, which directly interferes with AM colonization. For instance, root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) induce the formation of galls or giant cells (Rutter et al., 2022; Schreiner and Pinkerton, 2008). These anatomical modifications disturb the spatial and biochemical environment for arbuscule formation. In addition to physical barriers, nematode infection alters phytohormone signaling, such as auxin, salicylic acid, and jasmonic acid, which can negatively regulate the establishment of AM-associated signaling pathways (Martínez-Medina et al., 2017). Moreover, the nematode-induced feeding sites also exhibit reinforced cell walls and increased lignin deposition, posing further mechanical hindrances to AM hyphal penetration. The above evidence indicates that nematode infection significantly decreases AM colonization rate and arbuscule abundance (Hol and Cook, 2005). More interestingly, nematode-induced giant cells can act as strong C sinks that divert photoassimilates away from other root zones, effectively competing with AMF for C resources (Bell et al., 2022). This competition may reduce the C allocated to AMF, thereby diminishing fungal vitality and its nutrient delivery.

Belowground herbivores can indirectly modulate AMF activity by reshaping the rhizosphere environment. Their feeding behavior creates entry wounds that stimulate root exudation of secondary metabolites, such as flavonoids and phenolic acids, known to influence AM colonization in both positive and negative ways depending on fungal genotype, plant species, and edaphic context (Lanoue et al., 2010; Piotrowski et al., 2008). In parallel, the excreta of root-feeding herbivores, containing amino acids, organic acids, enzymes, and microbial residues, significantly alter rhizosphere pH, redox potential, nutrient availability and microbial composition. For example, nematode and root-insect frass can promote copiotrophic bacteria and saprotrophic fungi, increasing microbial competition for C and space and thereby suppressing AMF activity (Ourry et al., 2018). Conversely, herbivore inputs may favor PGPR (e.g., Pseudomonas, Bacillus), which can indirectly stimulate AM growth (Barto and Rillig, 2010). The net outcome of herbivore presence on AM function is thus highly context-dependent, governed by herbivore identity, soil nutrient status, and microbial community composition. These findings emphasize the complexity of multitrophic interactions in the rhizosphere and suggest that rhizosphere environment should be considered an important factor in mycorrhizal-plant-belowground herbivore interactions.

Herbivory not only alters local root dynamics but also triggers systemic defense responses that reprogram plant resource allocation strategies. Activation of these responses may lead to reduced C investment in AMF, as metabolic priorities shift toward defense compound synthesis. Additionally, herbivore-induced suppression of root exudation, particularly lipids and sugars essential for AM colonization, can compromise fungal adhesion and colonizing efficiency. Molecular studies further reveal that herbivory can downregulate the expression of mycorrhiza-inducible phosphate transporter genes in host roots. For instance, Meloidogyne infection in tomato has been shown to suppress AM-associated P transporter expression, suggesting a functional breakdown in nutrient exchange under biotic stress (Paszkowski et al., 2002). These findings underscore the vulnerability of the mycorrhizal symbiosis to herbivore-induced signaling cascades.

Taken together, belowground herbivores represent critical ecological disruptors that influence the root and AMF interface via three converging pathways: direct physical damage, modulation of the rhizosphere environment, and plant-mediated reprogramming of resource allocation. These impacts are particularly significant in systems where C, N, and P flows are tightly regulated and highly responsive to environmental cues. Hence, herbivores do not merely impose physical damage, but also actively reshape nutrient flow and efficiency of ecosystem service at the root and soil interface.

1.3. Carbon Flow in Mycorrhizal-Plant-Belowground Herbivore Interactions

In tripartite mycorrhizal-plant-belowground herbivore systems, C flow serves as the central driver coordinating symbiosis, plant defense, and microbial competition (Andrino et al., 2021; Parniske, 2008). Photosynthetically fixed CO₂ is converted into organic carbon compounds, a portion of which is secreted into the rhizosphere as exudates or directed to symbiotic partners in the form of “carbon payments”. These flows provide essential energy sources for AMF and other rhizosphere microbes. In AM symbiosis, plants allocate a substantial proportion, typically 10-30%, of their assimilated C to AMF in exchange for P, N, and other limiting nutrients This C-for-nutrient exchange is highly dynamic and under active regulation (Konvalinková et al., 2017). Plants evaluate the nutrient delivery efficiency of AMF partners and adjust C allocation accordingly, following a principle of mutualism stabilization via partner discrimination (Kiers et al., 2011). High-performance AMF strains receive more C, while low-benefit strains are deprived of host investment. Sensitivity to AMF performance varies among plant genotypes and AMF taxa, reflecting plants’ selective C investment strategies in managing their microbial partnerships.

The presence of belowground herbivores imposes multiple constraints on C flow pathways. On the one hand, herbivore-induced root damage stimulates compensatory growth responses in plants, leading to increased C reallocation toward root tissue repair and regrowth (

Figure 1a). This shift may reduce the C available for sustaining AMF networks, thereby compromising their structural integrity and functional efficiency (Bell et al., 2022). On the other, root wounding frequently triggers systemic activation of plant defense metabolism, including the synthesis of flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and volatile organic compounds, all of which require substantial C investment (

Figure 1a). These demands can create hidden resource competition between plant defense pathways and the C needs of AMF (Lanoue et al., 2010). A key advance in understanding this trade-off comes from Magkourilou et al. (2025), who investigated C flow in a potato-AMF-nematode system. Using C tracing approaches, they demonstrated that in AM-colonized roots, C is actively redirected away from regions infected by

Meloidogyne spp. and preferentially allocated to healthy, uninfected root zones (Magkourilou et al., 2025). Ecologically, this mechanism may protect the plant from C investment to damaged tissues but enhance growth and colonization of viable root segments. These findings challenge the classical view of AMF as passive carbon recipients and suggest they may participate in modulating the spatial routing of C flow under biotic stress.

Carbon in the mycorrhizal-plant-herbivore tripartite system functions not only as a physical currency but also as a regulatory signal. Through spatial and quantitative adjustments of C flow, plants dynamically balance symbiotic efficiency, defense priorities, and environmental constraints. AMF, far from being passive C sinks, actively participate in the spatial modulation of C allocation and may contribute to stress mitigation. Meanwhile, belowground herbivores disturb root structures and reprogram plant metabolism, thus interfering with or even reshaping C distribution patterns. Understanding this intricate C network offers new perspectives on rhizosphere adaptability and ecosystem stability.

1.4. Nitrogen Flow in Mycorrhizal-Plant-Belowground Herbivore Interactions

N is a fundamental component of plant macromolecules, including proteins, nucleic acids, and chlorophyll, making it central to plant metabolism. Unlike carbon, N in soil exists in highly heterogeneous forms, including ammonium (NH₄⁺), nitrate (NO₃⁻), and organic N, whose availability, mobility, and reactivity are strongly shaped by biological processes (Govindarajulu et al., 2005; Hodge and Fitter, 2010). Within the mycorrhizal–plant–herbivore system, N cycling extends beyond simple uptake and transport; it involves localized mineralization, microbial competition, and resource reallocation. Generally, belowground herbivores accelerate N release into the soil by physically damaging roots, promoting cellular lysis, and stimulating microbial activity. Root-feeding often liberates N-rich compounds, such as proteins and nucleic acids, which are rapidly mineralized into NH₄⁺ by the rhizosphere microbiota (

Figure 1b) (Bakker et al., 2004; Bonkowski et al., 2009). While this may temporarily benefit plants by generating localized N pulses, it also comes with trade-offs: microbial competition, AMF suppression, and impaired root integrity may offset the nutritional benefits. Under N stress, plants exhibit significant plasticity in N allocation. For instance, nematode infection often redirects N from growth-related processes toward defense-related processes, such as the synthesizing pathogenesis-related proteins or repair of damaged root tissues. These defense-or repair-prioritizing strategies restrict N allocation to mycorrhizal symbiosis, intensifying competition within the root zone (Zhou et al., 2015). Interestingly, moderate herbivore pressure can sometimes enhance plant dependence on AMF. This may occur when plants perceive root damage and consequently increase carbon investment to AMF, thereby improving nutrient uptake efficiency (Kiers et al., 2011). N flow within the mycorrhizal-plant-herbivore triad is multidirectional and extends beyond purely nutritional functions. It represents a highly regulated, context-dependent process governed by multitrophic interactions and adaptive trade-offs. AMF contributes to N cycling via direct uptake and synergistic interactions with microbes; herbivores induce N release but also disrupt symbiotic stability; and plants balance N use among growth, defense, and symbiosis demands. Unraveling this dynamic regulation is crucial for developing N-efficient, ecologically resilient agricultural systems.

1.5. Phosphorus Flow in Mycorrhizal-Plant-Belowground Herbivore Systems

Phosphorus is essential for plant life, functioning in energy metabolism (ATP/ADP), signal transduction (phosphorylation), and nucleic acid synthesis (Helfenstein et al., 2024; Vance et al., 2003). However, in most soils, P exits predominantly in poorly soluble or adsorbed forms, with only low concentrations available in the soil solution (Achat et al., 2016), severely limiting direct plant uptake (Helfenstein et al., 2024). To overcome this constraint, many plants engage in symbiosis with AMF, which is a strategy shaped by long-term evolutionary adaptation to P limitation (Johnson et al., 2010; Martin et al., 2017). AMF hyphae extend several centimeters beyond the root surface, accessing P pools far beyond the depletion zone. Absorbed P is transported along the fungal hyphae as polyphosphates and released into the root cortical cells arbuscular interfaces (

Figure 1c). This exchange involves both fungal phosphate transporters (e.g. GiPT, RiPT) and plant-encoded, mycorrhiza-specific phosphate transporters (e.g. MtPT4, OsPT11) (Harrison et al., 2002; Paszkowski et al., 2002). Under low-P stress, AMF enhance plant P uptake efficiency by up to 80%, acting as the primary gateway for P acquisition in numerous ecosystems (Lambers et al., 2009; Smith and Read, 2010).

However, this highly efficient mutualism is susceptible to disruption by belowground herbivores. By directly damaging root tissues, root-feeding herbivores impair AMF colonization, particularly in arbuscule development, thereby reducing P transfer to the host plants. Nematodes and other endoparasites induce the formation of root galls, aberrant cell proliferation, and altered root morphology, all correlated with reduced AMF infection rates and lower arbuscule abundance (Ishida et al., 2020). In addition to structural damage, herbivores can indirectly compromise AMF functionality by activating plant defense responses that alter root exudate composition and modify cortex permeability (Bonkowski et al., 2009). Damaged roots frequently secrete elevated levels of phenolic compounds and tannins, which are defensive metabolites known to inhibit AMF hyphal extension or downregulate host phosphate transporters expression (

Figure 1c) (Lanoue et al., 2010; Piotrowski et al., 2008). Concurrently, stressed plants may redirect carbon resources toward tissue repair and chemical defense, thereby reducing carbon allocation to AMF and limiting fungal metabolic activity (Bell et al., 2022). This resource reallocation reflects an adaptive trade-off under combined stressors, albeit potentially at the expense of symbiotic efficiency. P acquisition and transfer within the mycorrhizal-plant-herbivore system exhibit both high interdependence and ecological plasticity. AMF serves as the primary facilitators of P uptake, belowground herbivores impose major disruptions, and plants navigate this complexity by dynamically allocating resources among repair, defense, and symbiosis. A deeper understanding of these interactions offers important insights for informing resilient, rhizosphere-based P management strategies in sustainable agroecosystems.

2. Nutrient Flow in Mycorrhizal-Plant-Aboveground Herbivore Interactions

2.1. Mechanisms of Bi-directional Nutrient Flow

AMF are taxa of biotrophic organisms and strictly rely on the host plant resources. These symbioses function through a two-way trade: plants provide carbon to the fungi, while the fungi improve access to soil nutrients including N, P, potassium (K), and sulfur (Wang et al., 2017). On the one hand, improvement in plant nutritional quality can make them more attractive to insect herbivores. On the other, the altered levels of carbohydrates, amino acids (AAs), and/or plant defensive secondary metabolites in plant-mycorrhizal interactions, may directly affect host plant selection and/or reproductive scheme taken by herbivorous insects (Aqueel et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2017). For example, rice colonized by AMF shows increased N and P concentrations in shoots and higher N content in roots, thereby enhancing insect oviposition on them (Cosme et al., 2011). Likewise, mycorrhizal colonization can compromise production of endogenous alkaloids, increasing plant susceptibility to aphids (Cibils-Stewart et al., 2025).

Plants, mycorrhizal symbionts and herbivores are competing for the host’s limited C reserves (Piippo et al., 2011). Unlike belowground herbivores, aboveground herbivores, especially folivores, directly destroy photosynthetic organs which serve as the primary C source for many organisms. This brings a great disturbance to the C allocation and nutrient acquisition between belowground and aboveground communities. In wheat, aphid feeding disturbs the plant–fungus partnership, reducing carbon allocation to the AMF while phosphorus delivery from the fungi remains stable (Charters et al., 2020). In another case, aphids decrease the plant N uptake because of microbial immobilization in the direct pathway, and also probably due to the combined effects of microbial immobilization and C stress in the indirect pathway (Katayama et al., 2014). However, aphid-driven disruption of C-for-nutrient exchange can be relieved by the neighboring plants, so it is worth to investigate the nutrient exchange at community scale (Durant et al., 2023). As for chewing insects, leaf damage has been shown to shift mycorrhiza-mediated Pi pathways in roots, resulting in greater total shoot P content in Medicago plants (Zeng et al., 2022). Similarly, elevated foliar P concentration is shown in two mycorrhizal plants-milkweed and maize, against Danaus plexippus and Spodoptera frugiperda, respectively (Real-Santillán et al., 2019; Tao et al., 2016).

With global change, elevated atmosphere CO

2 influences mycorrhization and plant-soil interactions. From top to bottom, surplus C is converted into sugars, lipids and secondary metabolites, and a considerable portion transferred into the belowground and stored in roots or exudates or mycorrhizal fungi (

Figure 2; Prescott et al., 2020). Aboveground herbivores, remove plant tissues and store part of the excess CO

2, as additional C sinks. From bottom to top, aboveground grazing affects soil nutrient turnover and cycling (Kristensen et al., 2020). Subsequently, the newly released soluble nutrients from soils become available to aboveground tissues, supporting plant regrowth and reproduction. Overall, the nutrient flow between aboveground herbivores and mycorrhizal communities is bi-directionally and mutually regulated via plants.

2.2. Nutrient-mediated Plant Defense Strategy

As mentioned above, carbon-nutrient balance of plants is essential because it determines plants’ palatability and defense response to herbivores over long time periods. Sufficient nutrient provision may alter plant defense strategy, from decreasing allocation to active defensive compounds to increasing investment in plant regrowth and tolerance to herbivory (Coley et al., 1985; Shan et al., 2024). In a different way, improved nutrients status can also promote herbivore and pathogen intrusion in different mycorrhiza-colonized tree monocultures and their mixtures (Ferlian et al., 2021). Conversely, nutrient deficiency can increase the level of plant defense chemicals, thereby enhancing resistance to foliar herbivory (Khan et al., 2016).

AMF-mediated resistance to aboveground herbivores has been largely investigated in many plant species (Fernandez-Conradi et al., 2018; Shafiei et al., 2024; Kebede et al., 2024). However, one study shows that the attractiveness of beans to aphids is positively correlated with AMF, but neither P treatment nor leaf P content affects aphid abundance; the mechanism is rather manipulated by AM colonization-induced plant systemic signaling (Babikova et al., 2014). Similarly, plant nutrient composition has trivial effect on plant defense against Nesidiocoris tenuis, suggesting that changes in nutrient composition by the interaction with plant-beneficial fungi are probably not the primary cause of differences in damage levels (Meesters et al., 2023). In fact, the mycelial network can act as a conduit to transmit diverse signals, including defense enzymes, VOCs, C-and N-based compounds (Yu et al., 2022). Therefore, mycorrhiza-mediated plant defense response can be activated by two aspects, mycorrhizal colonization itself and mycorrhiza-induced nutrient uptake. Here, we mainly discuss the latter based on two types of defense mechanisms – resistance and tolerance.

Resistance

Resistance refers to a plant defense strategy aiming at avoiding or reducing the scope and severity of herbivore damage. In addition to improving plant access to macronutrients, such as N, P and K, AMF can also enhance the uptake of silicon (Si) and thus augment Si-based resistance to herbivores (Frew et al., 2017). According to the C–nutrient balance hypothesis, plants grown with limited nutrients tend to invest in carbon-based defenses, whereas under nutrient enrichment nitrogen-containing defenses become more prominent (Bryant et al. 1983). Thus, across different nutrient conditions, the cost-benefit trade-off between N- and C-based defensive compounds shifts, leading to an optimized allocation strategy under one condition but suboptimal under another (Burghardt, 2016). These shifts indicate that C-nutrient balance can directly affect the biosynthesis of plant secondary metabolites. Furtherly, increasing the abundance of AMF inoculum can affect the expression of plant nutrition and resistance traits, as a result, increasing the performance of a specialist insect herbivore (Vannette and Hunter, 2013). Differences in AMF community composition also influence chemical resistance: plants associated with diverse fungal partners often accumulate more phenolics in their leaves than those linked with only one species (Frew et al., 2022; Frew and Wilson, 2021).

Tolerance

Tolerance refers to mechanisms that help plants minimize fitness losses after herbivore damage has already occurred. A recent meta-analysis shows that microbial inoculants largely reduce the cost of herbivory via plant growth promotion, with overcompensation and compensation together accounting for approximately one-quarter of observations of microbial-mediated tolerance (Tronson and Enders, 2025). The tolerance and chemical defense mechanisms induced by AMF are strongly linked with plant nutrient status, biomass allocation and growth rate (Tao et al., 2016). Likewise, induced tolerance against root herbivore attack is provided by Trichoderma harzianum with which plants maintain a robust and functional root system as evidenced by the increased uptake of copper (Cu), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), and K (Contreras-Cornejo et al., 2021). Although AMF-mediated tolerance to herbivory has been reported, there is less known about how the metabolic mechanism of nutrient elements acts in plant tolerance to herbivory. Overall, integrating nutrient metabolism into the study of mycorrhizal-plant-herbivore interactions would greatly enhance our understanding of nutrient-mediated defense mechanisms.

2.3. The Impact of Aboveground Herbivory on Belowground Communities

The plants allocate downwards C and mineral resources to root exudates, roots, mycorrhizae, and the belowground system, including herbivores. Here, we will discuss these belowground C sinks (

Figure 2).

First, aboveground herbivores can either suppress, stimulate, or leave unchanged the degree of root colonization by AMF, depending on context. For example, aphid feeding has been shown to decrease the level of AM colonization (Babikova et al., 2014), perhaps by the limitation of C allocation in plants (Barto and Rillig, 2010). However, in other studies, herbivory by aphids can increase AM colonization of Asclepias incarnata roots (Meier and Hunter, 2018). Overall, the effect of aboveground herbivory on AM colonization appears to be plant species-specific (Gange et al., 2002; Meier and Hunter, 2018). This may result from the varying ability of different plant species to regulate C allocation to AMF (Grman, 2012). Importantly, an increase in root colonization does not imply improved uptake of nutrients (Elliott et al., 2021). Perhaps, it may trigger other shifts in the rhizosphere. For example, foliar herbivores enhance AM colonization by increasing lipids level in root exudates and meanwhile reduce root biomass (Xing et al., 2024a), and this might be due to alteration in root flavonoid composition (Xing et al., 2024b).

Second, researchers have proposed two opposing views on how herbivory influences ecosystem processes: one emphasizes reduced nutrient cycling, while the other highlights its potential to accelerate nutrient turnover (Belovsky and Slade, 2000). On one side, herbivory can decrease nutrient cycling and plant abundance. When leaf-feeding insects reduce the flow of carbon belowground, AM symbiosis may be weakened, limiting the fungi’s contribution to phosphorus uptake (Frew, 2021). On the other side, herbivory facilitates nutrient cycling and leads to a higher plant abundance. Recent studies show that herbivory indeed contributes to the nutrient exchange between mycorrhizal plants and their substrates (Bell et al., 2022; Zeng et al., 2022). On a large scale, aboveground herbivory may decrease plant C allocation to the belowground, thereby altering associated mycorrhizal communities that could stimulate soil C and N turnover (Frew et al., 2024; Kristensen et al., 2020).

Notably, environment factors cannot be ignored when evaluating the impacts of aboveground herbivory on belowground communities. For instance, salinity and light, and the composition of AM fungal communities might fine-tune the dynamics of nutrient exchange in AMF-plant–herbivore interactions (Ba et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2023). Also, the availability of soil water and nutrients control the impact of AMF on plant growth and herbivore infestation (Wang et al., 2023). Additionally, mycorrhizal source would exert an effect on mycorrhizal growth response and mycorrhiza-induced resistance (Delavaux et al., 2025).

Overall, to cope with resource shortage and herbivory, both mycorrhizal associations and herbivory can shape the pattern of plant C allocation. Finally, the updated C partitioning strategy between aboveground and belowground alters the relationship of the source and sink to compensate for the removal of the aboveground tissue.

3. Nutrient Flow in Mycorrhizal-Plant-Above-and Below-ground Herbivore Interactions

3.1. Mechanisms in Mycorrhizal-Plant-Above-and Below-ground Herbivore Interactions

In natural systems, plants are confronted with the AG and BG attackers at the same time, or one type of herbivores arrive before the other, competing for the limited plant resources (

Figure 3). The impact of simultaneous AG and BG herbivory on plant-mycorrhizal interaction dynamics has been less studied. So how AMF mediate herbivore-induced plant defense and nutrient allocation is relatively less known when combining with AG and BG antagonists. Indirect interactions between AMF and herbivores may bring a community-wide reaction by altering plant physiological status and functional traits in both AG and BG compartments. In turn, AG and BG herbivores exert a certain effect on plant-mycorrhizal interactions. By changing the nutritional status of leaves, foliar feeders can affect not only the physiology of individual plants but also community composition (Gange and Brown, 2002; Hamilton III and Frank, 2001). These shifts cascade belowground, influencing soil resources and associated organisms (Gange and Brown, 2002; Hamilton III and Frank, 2001). However, the net outcome of AG-BG herbivory is not always straightforward or detectable. In one case, aboveground herbivory mitigates plant-belowground interactions but not influences plant-mycorrhizal interactions (Zhao et al., 2024).

In fact, AG and BG herbivory is intricately interacting with other symbioses, such as AM associations, through their shared host plants. As reported, AM symbiosis has been identified as a key mechanism supporting the dominance of C4 grasses in the grass communities, while combined foliar and root herbivory limits their dominance, finally facilitating plant diversity (Duell et al., 2025). This might be because the negative impact of AG and BG herbivory can generate a pattern of increased plant species diversity through competitive release of dominant species. Indeed, the underlying mechanisms are complex. It is supposed that the presence of AMF provides grazing tolerance to highly mycotrophic C4 grasses, likely facilitating regrowth after defoliation, whereas non-mycorrhizal grasses suffer from great damage and recover difficultly (Duell et al., 2025).

The classical ‘plus-minus’ model proposes that root herbivory increases the performance of foliar feeders, whereas foliar herbivory suppresses the growth of root feeders (Masters et al., 1993). In certain cases, mutualists can mitigate the negative impact of plant enemies such as herbivores (Morris et al., 2007). Thus, this plus-minus model should be modified because foliar feeding by insects may result in increased performance of root feeder due to mycorrhizal symbionts. Therefore, cultivating mutualists is an approach to counteract the negative effects of plant damage and increase yields. However, this action will only be meaningful if damage level is not too severe. Therefore, the strength of interactions between plants and community members might influence other community interactions and ultimately determine plant performance (Barber et al., 2012).

Meanwhile, there are other factors affecting the mechanism of multitrophic interactions. For instance, genetically variant plants (native and alien species) vary in how they affect AG and BG herbivore performances and their interactions, suggesting divergent selection on plant defenses plays a key role in mediating AG and BG herbivore interactions (Li et al., 2016).

3.2. Primary and Secondary Metabolites in Multitrophic Interactions

Herbivores from AG and BG can impact the cross-compartment movement of primary and secondary metabolites through systemic tissues (

Figure 3). AG herbivory has been shown to facilitate the development of BG parasitic nematode through modified root carbohydrates in

Nicotiana spp. (Machado et al., 2018). Some nematodes can reduce the synthesis of nicotine in roots, which lowers chemical defenses and indirectly benefits aboveground herbivores (Kaplan et al., 2008a,b). In addition to producing secondary metabolites

in vivo, plants can also release volatile compounds following BG herbivory, and these systemic plant volatile emissions can resist subsequent AG herbivores on the neighbouring plants (Thompson et al., 2024).

The tripartite interactions with dual types of herbivores can also lead to multiple systemic alterations of primary and secondary metabolites in AG and BG compartments simultaneously. For example, the resistance to conspecific foliar feeders stimulated by tuber feeders could be linked to the induction of glycoalkaloid-based secondary metabolites, while facilitation of conspecific tuber feeders induced by tuber herbivory and AMF are more likely mediated by shifts in primary metabolite profiles, including changes in C, N, soluble protein, soluble sugar and starch (Wang et al., 2023). Similarly, AG and BG herbivores influence the composition of pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs), plant-fungus interactions and plant-soil feedback (Bezemer et al., 2013), thereby altering the performance of late-growing plants via legacy effects (Kostenko et al., 2012).

A common plant response to herbivory is resource sequestration, where nutrients are redirected away from damaged organs into intact tissues, sometimes within a short period (Orians et al., 2011). Importantly, AG herbivore-induced resource sequestration can indirectly affect BG herbivores. The effects may be positive when roots serve as sinks for photosynthates, enhancing their nutrient supply for herbivores. Conversely, they may be negative if sequestration leads to the accumulation of defensive compounds in roots, thereby reducing their quality as a food source for root herbivores (Biere and Goverse, 2016). As an example of negative effects, root herbivory can trigger higher concentrations of defensive compounds in leaves, which in turn diminishes the performance of shoot feeders (Van Dam et al., 2005).

3.3. Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Flow

Plant N has been largely studied in previous research of multitrophic interactions. Meanwhile, Tissue P concentration as a factor can also mediate AG-BG herbivore interactions (Johnson et al., 2013). Moreover, the compositional increases in essential AAs that arise from root herbivory, rather than the quantity of total AAs, underpin the positive effects on AG phloem-feeding herbivores (Johnson et al., 2013). As mentioned in sections 1 and 2, AM symbiosis is intimately linked to the uptake and movement of those nutrients. This implies that plant nutrient acquisition and allocation are highly susceptible to many biotic factors.

Upon herbivory, plants allocate C and N towards damaged tissues to support compensatory growth or the biosynthesis of defensive compounds for survival and reproduction. However, production of defensive compounds is costly in terms of the same resources required for plant regrowth. Thus, when the costs of resistance outweigh the costs of tissue loss by herbivory, plants may employ the tolerance tactic to cope with herbivory stress. For example, plants exposed to Spodoptera exigua and nematodes show elevated N concentrations in shoot and root tissues, which indicates the needs of additional N from the soil to meet the increased demand of N, either for compensatory growth or biosynthesis of N-based defensive compounds (Kafle et al., 2017). This might imply that the direction of nutrient flow determines the trade-off of growth and defense.

Moreover, AG-BG interactions change plant nutritional quality asymmetrically. Because BG herbivores consume root tissues, directly reducing the plant´s ability to take up water and nutrients. This effect propagates to AG compartments via the plant, resulting in changes of the nutritional quality of AG plant tissues, including changes in water content or concentration of free AAs and soluble sugars. Nutritional imbalances between shoots and roots may partly reflect the fact that roots are sometimes attacked earlier than leaves, setting off changes before AG herbivores arrive (Bezemer and Van Dam, 2005).

3.4. It Matters Who Comes First and How about the Amount and the Intensity of Damage

It matters who comes first

The interactions between herbivores and AMF sometimes occur simultaneously on a host plant, altering plant morphological and biochemical traits and thereby not only affecting each other’s performance, but also the subsequent AG or BG herbivores.

First, identity and feeding modes of the herbivores are critical to the outcome of multiple interactions. The consequences of AG herbivory for the plants can be altered by the subsequent BG herbivory. For instance, plants infested by aphids show compensatory growth when challenged by nematodes subsequently; however, the growth pattern of which is not obviously changed when the plants only host aphids. In contrast, plants fed by S. exigua do not present such compensatory growth even also challenged by nematodes (Kafle et al., 2017).

Johnson et al. (2012) showed through meta-analysis that the timing of herbivore arrival is crucial, with AG and BG feeders exerting different kinds of priority effects. It suggests that mechanisms of AG-BG interactions intrinsically vary determined by the direction and strength of the interaction, as well as by the herbivore species (Huang et al., 2017, 2014; Johnson et al., 2012). Moreover, Changes of PAs content in the soil biota induced by AG and BG herbivores greatly influence the biomass and aboveground multitrophic interactions of succeeding plants (Kostenko et al., 2012). Therefore, when AG and BG herbivores feed on the plants in an irregular time order, it might produce diversified legacy effects. In conclusion, the sequence of AG and BG herbivory is important in AG-BG interactions and that knowledge on the timing of exposure is essential to predict outcomes of interactions (Wang et al., 2014).

The amount and the intensity of damage matter

The severity of tissue loss influences whether plants rely more on tolerance or resistance to withstand herbivory. At the very early stage of herbivore attack, plants might invest more energy into tolerance than resistance as the nutrient acquisition via AM symbiosis show more robust when the C supply to AMF is sufficient and leaf tissues are not severely destroyed at this stage (Zeng et al., 2022). However, in another study, damage treatment, mimicking the natural timing of feeding in the system, may occur so early in the plants´ development that the tissue loss is more than the plants could tolerate (Barber et al., 2012). Therefore, the damage level by herbivores is essential in the tripartite interactions.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Nutrient exchange supports the intricated interplay network between AMF, plants, and herbivores across compartments. Among this network, AMF play a critical role in the tradeoff of plant growth and defense, either interacting with AG or BG herbivores, by modulating carbon allocation and nutrient acquisition. Outcomes of AG-BG interactions are highly context-specific, shaped by the type of herbivore, timing and severity of feeding, the host plant, and environmental conditions. A prediction of the outcomes is crucial for ecosystem functioning, particularly under scenarios of global change. Future work could integrate metabolomic and isotopic tracing approaches to disentangle the mechanisms of nutrient flow in the multitrophic interactions at community level.

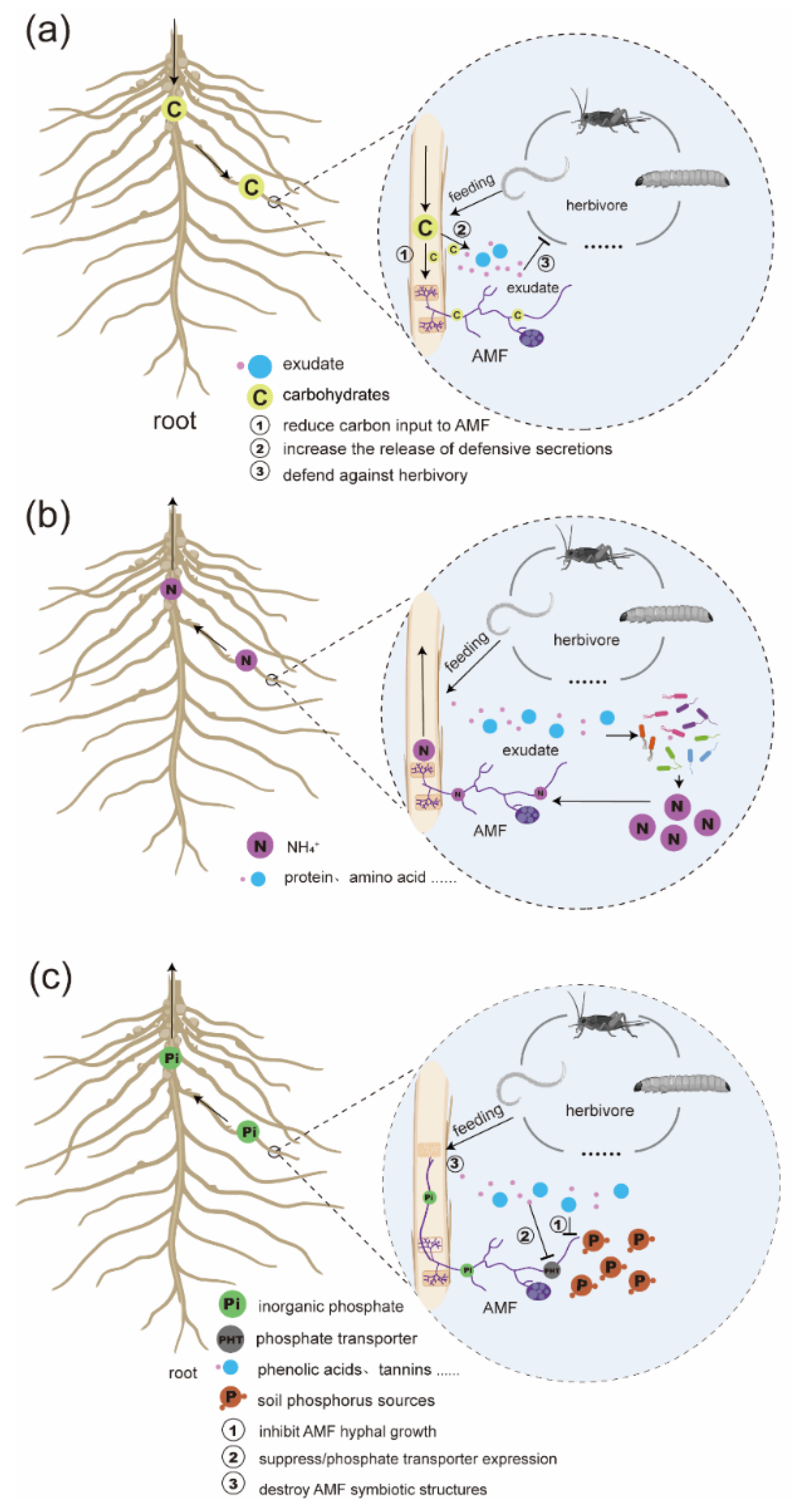

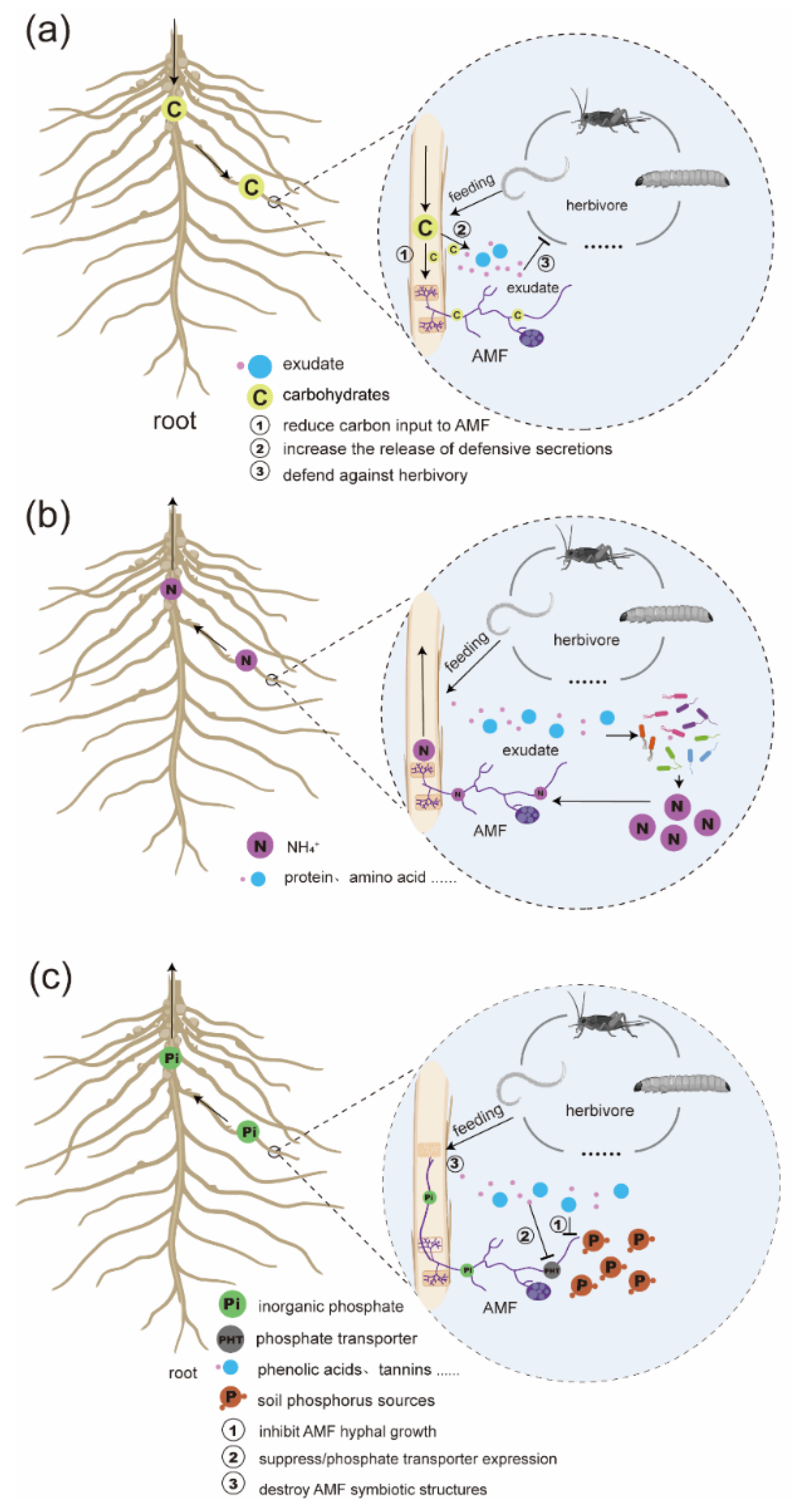

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of AMF-mediated nutrient (C, N, and P) flow mechanisms under root herbivore interference. (a) C flow mechanism: Plants fix CO₂ through photosynthesis and transport photoassimilates to the roots to support symbiosis with AMF. The fungal hyphae receive plant-derived C and establish an extensive extraradical network, facilitating reciprocal C-nutrient exchange. Herbivore-induced root damage increases the plant’s demand for compensatory root growth, thereby reallocating more C to the root system. This physiological shift may reduce C supply to AMF, compromising the stability and function of the mycorrhizal network. Additionally, root injury often triggers enhanced secondary metabolism, such as increased synthesis of flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and volatiles, all of which require C investment and may compete with AMF for limited C resources. (b) N flow mechanism: AMF absorb ammonium (NH₄⁺), nitrate (NO₃⁻), and some organic nitrogen compounds via their extraradical hyphae and deliver them to the host plant. Herbivore feeding causes cell lysis in root tissues, releasing N-rich compounds such as proteins and nucleic acids, which are rapidly decomposed by rhizosphere microbes into available NH₄⁺, forming a short-term N pulse for plant uptake. (c) P flow mechanism: AMF establish efficient P uptake channels in the rhizosphere by acquiring phosphate from beyond the root depletion zone and transferring it through arbuscules to plant cortical cells. Root damage enhances the secretion of defensive metabolites (e.g., phenolic acids and tannins), some of which may inhibit AMF hyphal growth or suppress the expression of plant phosphate transporters, thereby negatively affecting P transfer efficiency.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of AMF-mediated nutrient (C, N, and P) flow mechanisms under root herbivore interference. (a) C flow mechanism: Plants fix CO₂ through photosynthesis and transport photoassimilates to the roots to support symbiosis with AMF. The fungal hyphae receive plant-derived C and establish an extensive extraradical network, facilitating reciprocal C-nutrient exchange. Herbivore-induced root damage increases the plant’s demand for compensatory root growth, thereby reallocating more C to the root system. This physiological shift may reduce C supply to AMF, compromising the stability and function of the mycorrhizal network. Additionally, root injury often triggers enhanced secondary metabolism, such as increased synthesis of flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and volatiles, all of which require C investment and may compete with AMF for limited C resources. (b) N flow mechanism: AMF absorb ammonium (NH₄⁺), nitrate (NO₃⁻), and some organic nitrogen compounds via their extraradical hyphae and deliver them to the host plant. Herbivore feeding causes cell lysis in root tissues, releasing N-rich compounds such as proteins and nucleic acids, which are rapidly decomposed by rhizosphere microbes into available NH₄⁺, forming a short-term N pulse for plant uptake. (c) P flow mechanism: AMF establish efficient P uptake channels in the rhizosphere by acquiring phosphate from beyond the root depletion zone and transferring it through arbuscules to plant cortical cells. Root damage enhances the secretion of defensive metabolites (e.g., phenolic acids and tannins), some of which may inhibit AMF hyphal growth or suppress the expression of plant phosphate transporters, thereby negatively affecting P transfer efficiency.

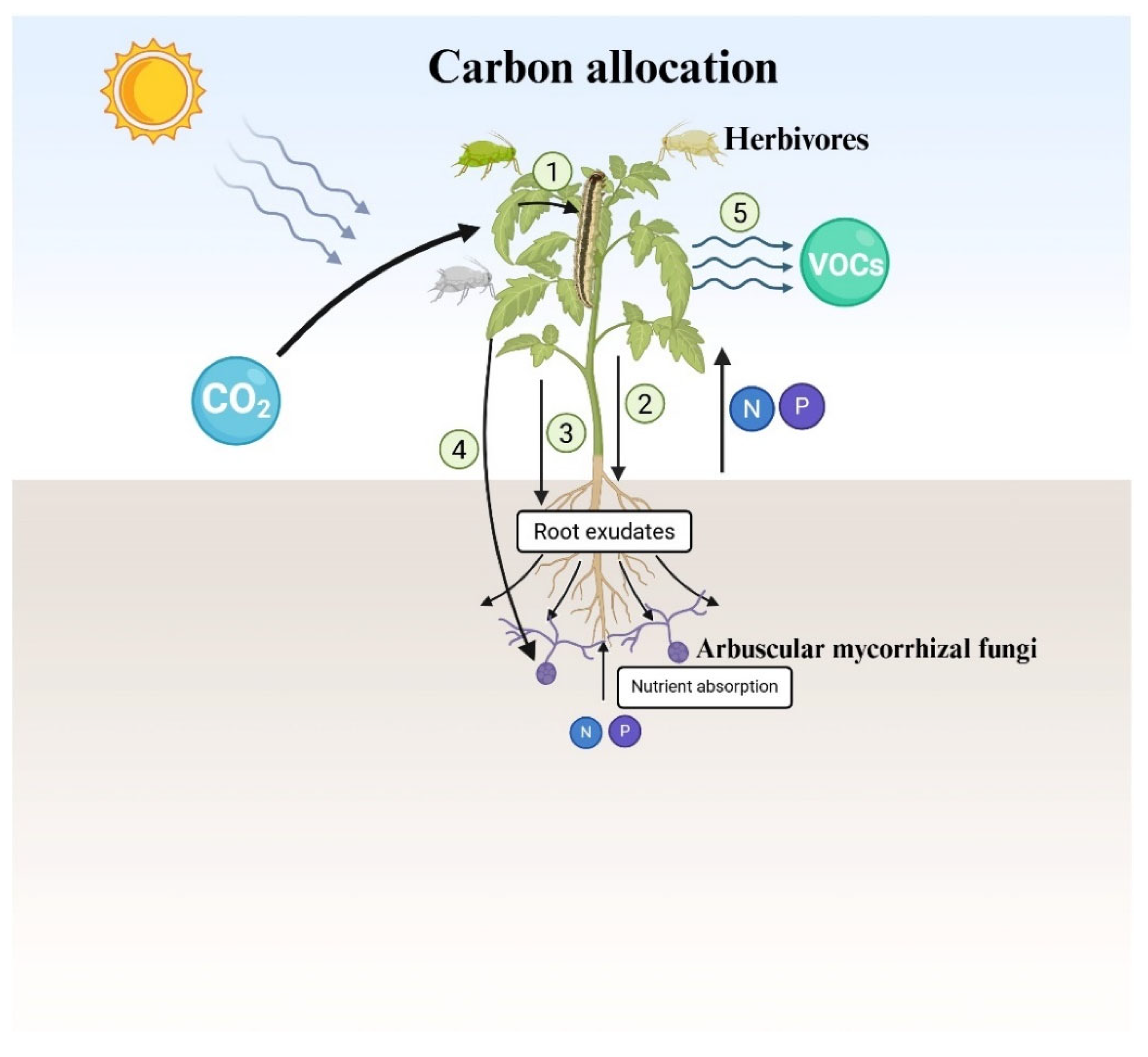

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of carbon allocation under attack by aboveground herbivores. From top to bottom, CO2 is assimilated by plants via photosynthesis reaction and then converted into plant-available C for other organisms, presented by sugars, lipids, amino acids, and secondary metabolites. A considerable portion of this carbon is transferred into herbivores and then downwards into the BG and stored in roots, root exudates, mycorrhizal fungi or released as volatile organic compounds (VOCs), as indicated with a series of numbers, respectively. Meanwhile, from bottom to up, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi supply nutrients such as N and P to the plants for their growth.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of carbon allocation under attack by aboveground herbivores. From top to bottom, CO2 is assimilated by plants via photosynthesis reaction and then converted into plant-available C for other organisms, presented by sugars, lipids, amino acids, and secondary metabolites. A considerable portion of this carbon is transferred into herbivores and then downwards into the BG and stored in roots, root exudates, mycorrhizal fungi or released as volatile organic compounds (VOCs), as indicated with a series of numbers, respectively. Meanwhile, from bottom to up, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi supply nutrients such as N and P to the plants for their growth.

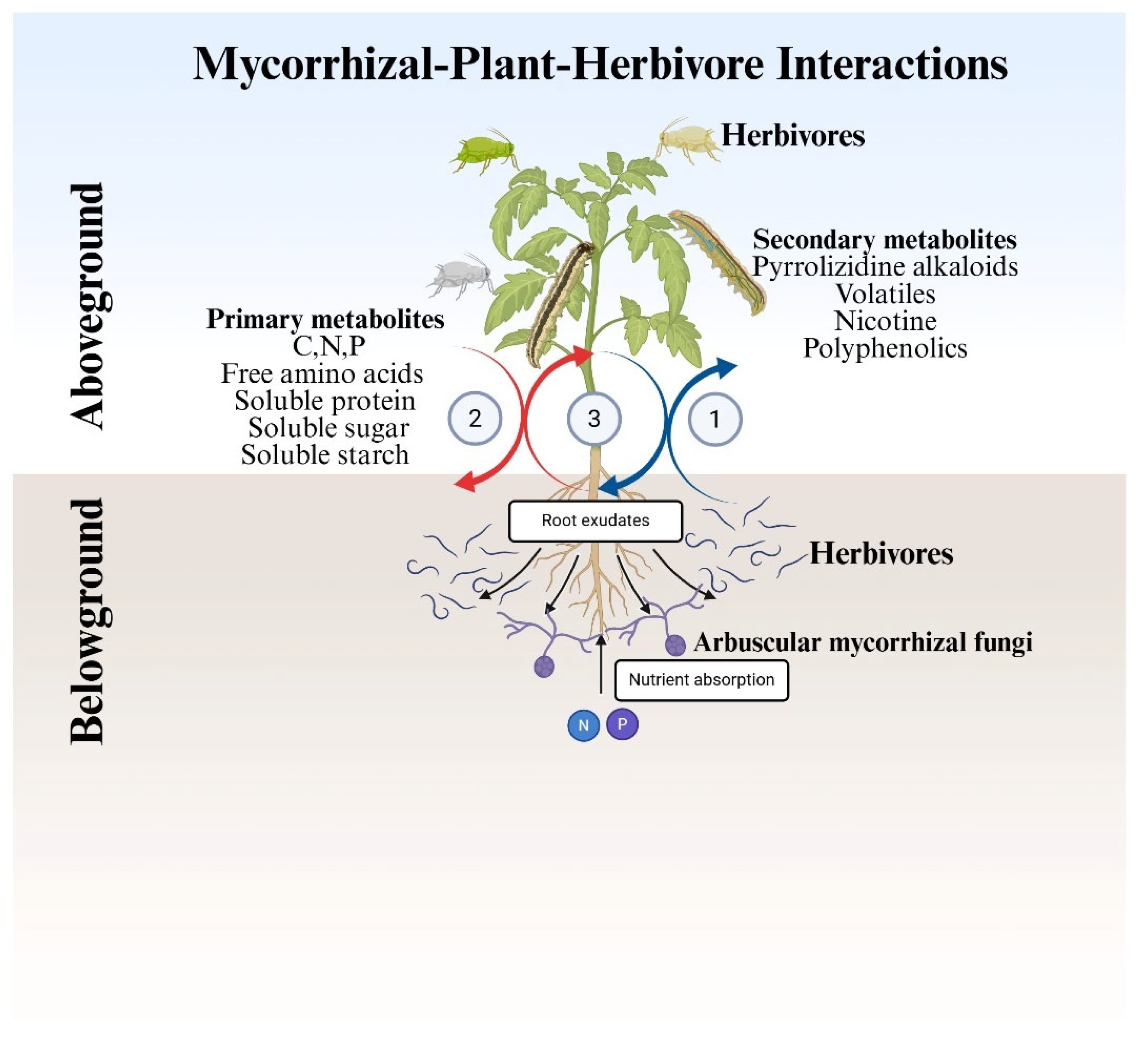

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of AMF-mediated nutrient (C, N, and P) allocation mechanisms under attack by combined aboveground and belowground herbivores. Pathway 1 indicates plant response to BG herbivores. Pathway 2 indicates plant response to AG herbivores. Pathway 3 indicates the whole plant responding to AG and BG dual herbivores. Across these interactions, primary and secondary metabolites, as well as root exudates, are induced by multiple biotic factors, while AMF-associated plants take up nutrients from the soil pool.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of AMF-mediated nutrient (C, N, and P) allocation mechanisms under attack by combined aboveground and belowground herbivores. Pathway 1 indicates plant response to BG herbivores. Pathway 2 indicates plant response to AG herbivores. Pathway 3 indicates the whole plant responding to AG and BG dual herbivores. Across these interactions, primary and secondary metabolites, as well as root exudates, are induced by multiple biotic factors, while AMF-associated plants take up nutrients from the soil pool.