1. Introduction

Buried ferromagnetic targets, such as unexploded bombs, mines and artillery shells, pose a severe and multi-dimensional threat to human safety, ecological systems, and economic development due to their long-term latent presence and unpredictable risk of detonation [

1,

2]. Magnetic detection technology, which operates passively, is highly sensitive to ferromagnetic materials and remains unaffected by hydrological conditions. These advantages make it particularly suitable for locating ferromagnetic objects [

3,

4,

5,

6]. To achieve the localization, one or multiple magnetic sensors are deployed, or a magnetic gradient tensor (MGT) system is utilized.

A MTG system is composed of fixed sensor arrays in two or three dimensions, acquiring magnetic field data through row scanning. In [

7], a closed-form solution for location of a magnetic dipole was derived based on measured vector magnetic field and magnetic gradient tensor. A magnetic dipole inversion approach based on the geometric invariants of the MGT was proposed in [

8]. To avoid errors caused by attitude variations, a localization model was constructed utilizing the rotation-invariant property of MGTs in [

9]. In [

10], a second-order MGT system integrated with Euler deconvolution algorithm was presented to estimate the coordinates of a magnetic dipole source. For more accurate target localization, an improved magnetic field tilt angle estimate along with an adaptive fuzzy c-mean clustering algorithm was reported in [

11]. MGT systems can acquire rich magnetic field structural information and possesses strong anti-noise ability, which are conducive to target localization. However, MGT systems are relatively high-cost because of integrating many sensors and usually hard to calibrate. MGTs are commonly used to detect relatively near target, as the spacing of sensor elements should be comparable with the distance to target.

There are many detection methods based on using data from single or multiple magnetic sensors mounted on airborne or ground platforms [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Parameters needing to be estimated usually include target’s position and magnetic moment. Both direct solution approaches and optimization-based algorithms have been developed. Direct methods realize target parameter inversion by constructing and solving linear equations. Based on total field data, a fast linear algorithm was implemented in [

16], while Euler deconvolution methods were employed in [

17,

18]. However, direct methods if involving differential operations or matrix inversions are typically sensitive to noise, potentially causing reduced solution accuracy. In contrast, optimization algorithms estimate parameters by constructing and minimizing an objective function related to the magnetic anomaly field associated with target location and magnetic moment. Commonly used optimization algorithms include the particle swarm optimization algorithm [

19], the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm [

20], the genetic algorithm [

21], and the simulated annealing algorithm [

22]. The choice of optimization algorithm also affects the accuracy of estimated parameters. In addition, the aforementioned direct and optimization methods solve the target’s positions and magnetic moments simultaneously. If the magnetic moments can be eliminated from the linear equations, the position parameters can be more accurately estimated. By using multiple sensors, we can adjust their spacing for detection of targets at different distances to achieve distinguishable magnetic anomaly signals.

In this study, we present an alternative measurement setting and optimization algorithm for localization of buried magnetic targets. In considering the low efficiency and poor stability of row scanning by moving the sensors on uneven ground, we adopt rotating scanning measurement. To reduce the number of unknowns and extract more accurate target’s position, we eliminate the magnetic moments and geomagnetic field from the modeling equations. A joint optimization algorithm is developed to solve the target’s coordinates by combining the quantum particle swarm optimization (QPSO) with the genetic algorithm (GA), named QPSO-GA. It incorporates the advantages of rapid convergence and local refined search of QPSO with the advantages of global exploration and diversity preservation of GA. We will conduct field experiments to demonstrate the feasibility.

The paper is organized as follows,

Section 2 describes the specific details of the magnetic anomaly signal model and QPSO-GA joint algorithm.

Section 3 presents the validation results from the simulation and field experiments. Finally,

Section 4 gives some concluding remarks.

2. Positioning Method

2.1. Magnetic Anomaly Signal Model

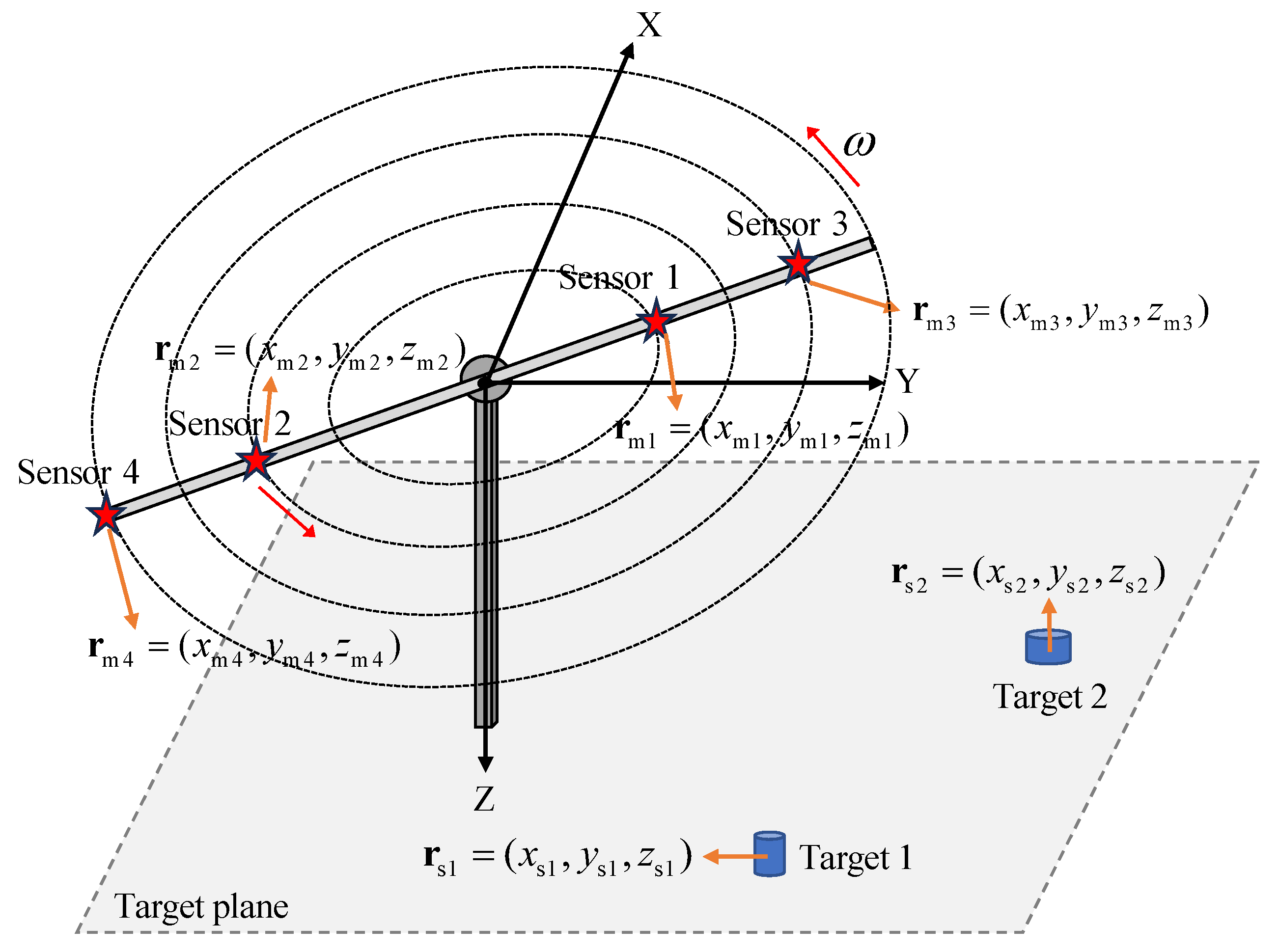

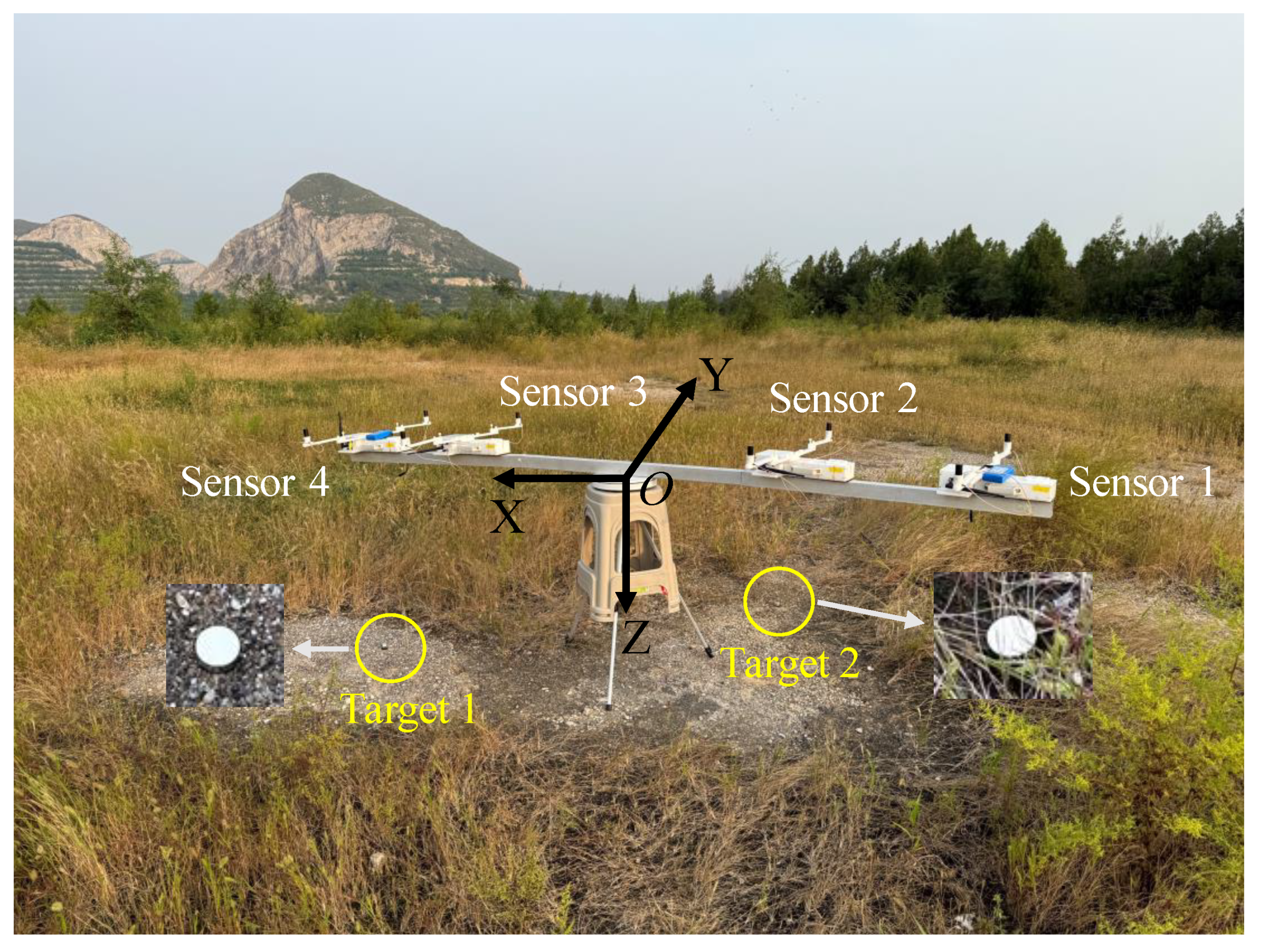

Our measurement setting utilizes an automatic rotating track made of non-magnetic material as the sensor platform. Multiple fluxgate sensors are integrated onto this platform to acquire magnetic field data via a rotating scanning approach.

Figure 1 illustrates four sensors and two targets for localization. A coordinate system is established with the center of the rotating platform as the origin. The x-axis is aligned with geographic north, the y-axis points eastward, and the z-axis is perpendicular downward. If the distance between the sensor and the target exceeds three times the target’s dimensions, the target can be regarded as a magnetic dipole [

23]. Assuming that there are

L sensors, and

Q targets to be detected. The vector magnetic anomaly signal generated by the

jth target at the

nth measurement point is measured by the

ith sensor is

where

H/m is the vacuum permeability,

is the

jth target magnetic moment,

is the distance vector between

jth target and

ith sensor at the

nth measurement point,

is the

nth measurement point coordinate of the

ith sensor, respectively, provided by the GPS module.

is the

jth unknown target coordinate to be solved, and

is the unit dyad.

The scalar magnetic field generated by the magnetic anomaly target can be defined as the projection of the vector magnetic field onto the direction of the geomagnetic field, expressed as

where

is the local geomagnetic field and

is its directional vector with respect to the platform measured by the sensor.

The magnetic anomaly signal sequence measured by

L sensors at the

nth measurement point can be expressed as

where

is the sum of magnetic anomaly signals generated by all targets measured by the

ith sensor.

is an L × 3L block diagonal matrix, where each diagonal block is the 1 × 3 vector

.

In real-world environments, the total magnetic field measured by sensors at the

nth measurement point includes not only magnetic anomaly signals

but also the local geomagnetic field

and the other magnetic noises

. Therefore, the total magnetic field sequence containing all measurement points can be expressed as

Based on the parity of sampling point indices,

is divided into two subsets: the magnetic field measured at odd-indexed points is denoted as

, and that measured at even-indexed points is denoted as

.

where

is the coordinate sequence corresponding to the odd measurement points, and

is corresponding to the even measurement points. To make the anomaly signal and the geomagnetic field comparable in magnitude, we intentionally introduce a reference value

nT, and

, where

is a unit column vector, so (

8) can be written as

where

. Similarly,

Combine (

10) and (

12) to eliminate magnetic moment

and geomagnetic field

to obtain the expression that only includes the target coordinates

2.2. QPSO-GA Joint Algorithm

To solve the target’s coordinates, we propose a QPSO–GA joint algorithm that integrates the strengths of quantum-behaved particle swarm optimization (QPSO) [

24,

25] and genetic algorithm (GA) [

26,

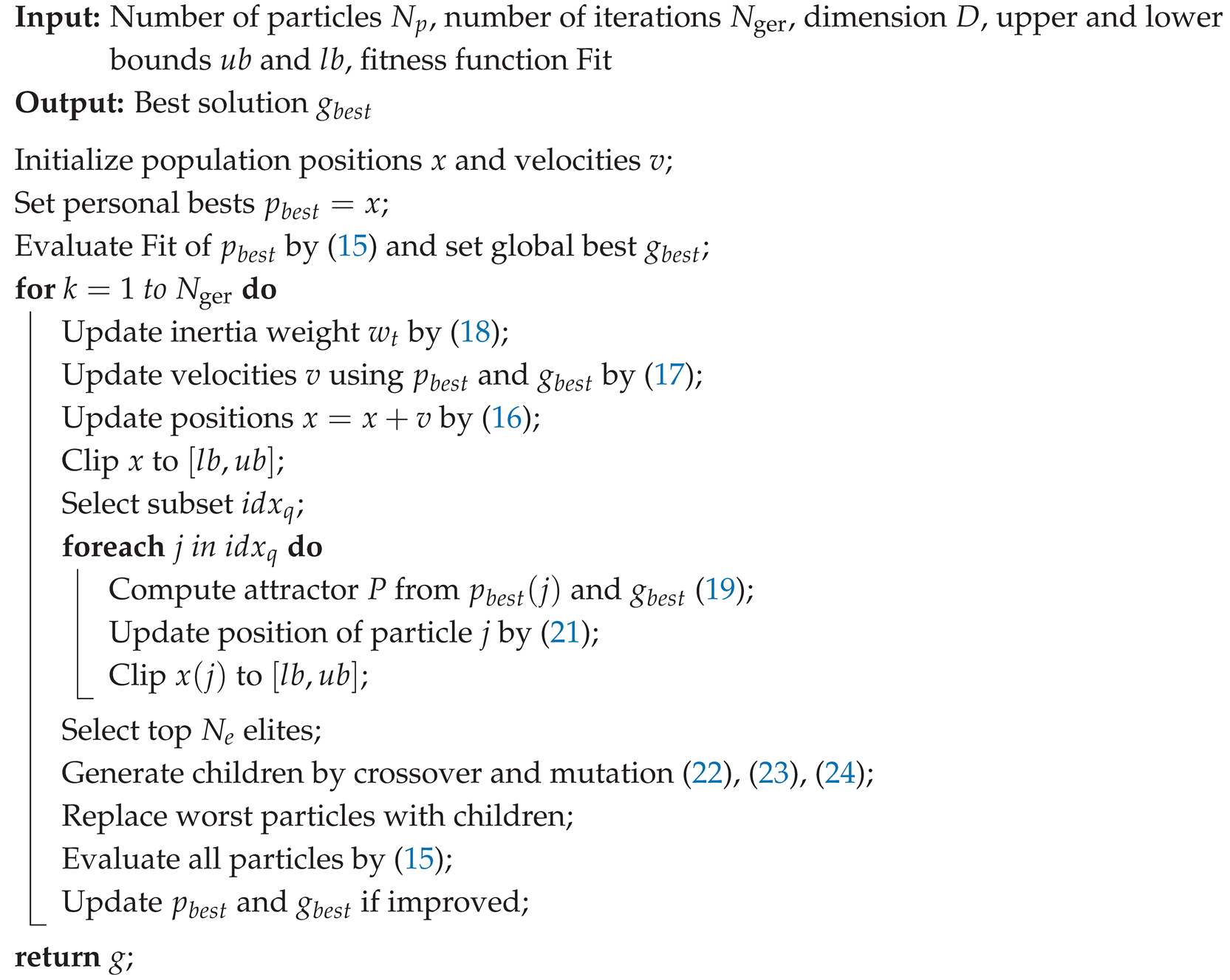

27]. QPSO excels in local refined search and rapid convergence, while GA demonstrates outstanding performance in global exploration and diversity maintenance. In the proposed joint strategy, QPSO is first employed to achieve rapid convergence and local optimization; Subsequently, genetic operators (selection, crossover, and mutation) from GA are introduced to reorganize and optimize the particle swarm, thereby enhancing global search capability and improving the overall solution accuracy. By effectively integrating the core mechanisms of both algorithms, this approach enhances reliability and robustness, outperforming either algorithm alone in convergence speed, global search capability, and convergence accuracy. A detailed description of this algorithm is provided as follows.

1) Fitness Function: In optimization problems, it is necessary to construct a fitness function to evaluate the quality of solutions. According to equation (

13), the residual vector

is defined as the difference between the actual value

and the predicted value

. This residual is used to quantify the prediction error, thereby guiding the optimization process. The optimization algorithm uses the standard deviation (STD) of

as the fitness function, and its expression is as follows

where

N is the is the total number of measurement points in the odd/even sequence. We need to search for the target’s coordinates

within the specified range to minimize the Fit value.

|

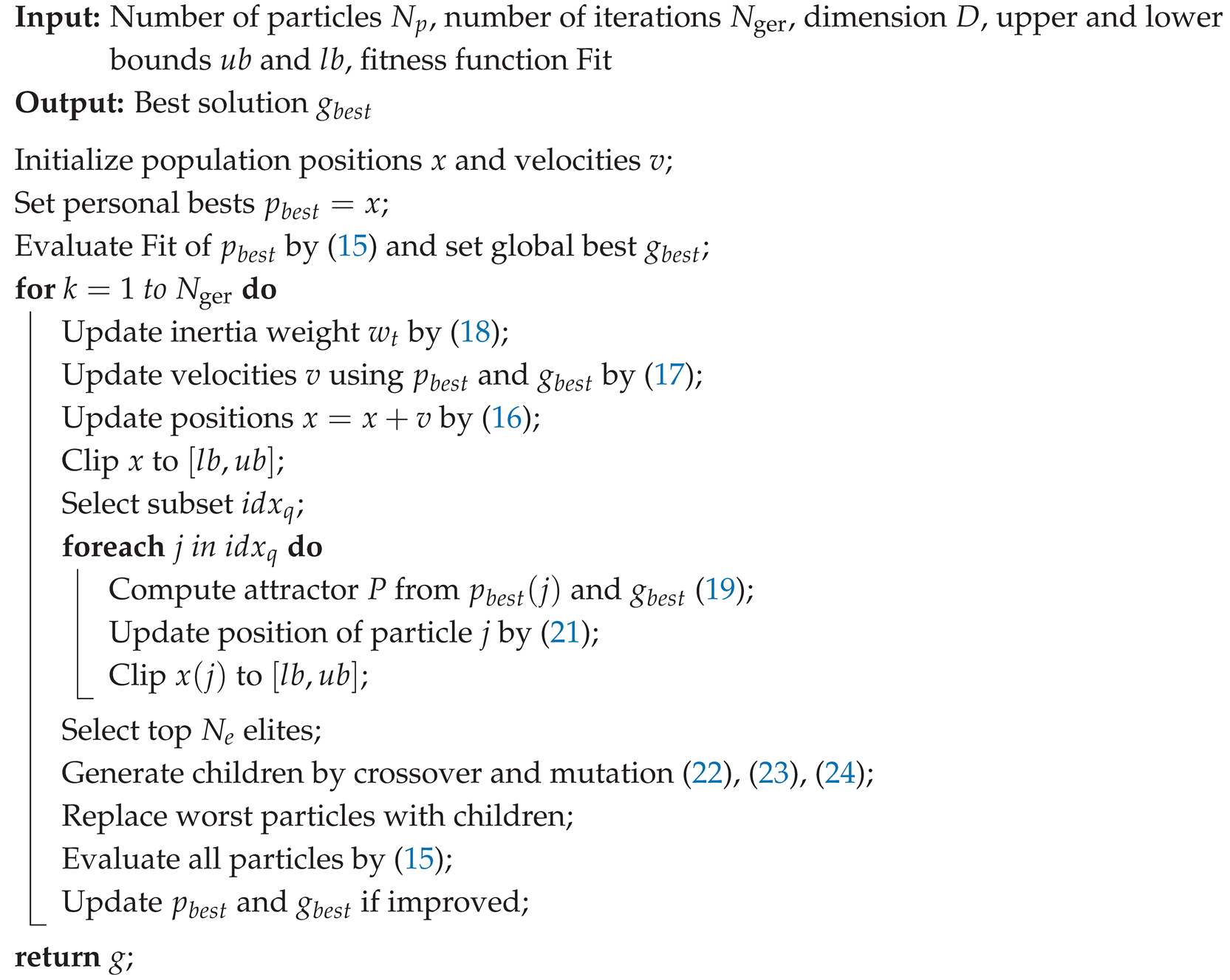

Algorithm 1:QPSO-GA joint algorithm |

|

2) Algorithm Update Strategy: During the iterative process of the joint algorithm, the implementation steps are as follows: in each iteration, particle positions are first updated using the quantum leap operation from QPSO to enable efficient optimization, as described in equations (

16) to (

20). Subsequently, genetic operations from the GA (including selection, crossover, and mutation) are introduced to reorganize and perturb the population, as specified in equations (

22) to (

24). Let

denote the number of particles,

the maximum number of iterations, and

D the dimensionality of the problem (in this paper,

). The variables

and

represent the upper and lower bounds of the search range, respectively. The position of the

ith particle in the

kth generation is denoted as

, and individual best position (

) is denoted as

and population best (

) is

.

Firstly, we employ the parameter update strategy of QPSO. The particle positions are updated by

where

is the velocity of the

ith particle at the

kth generation,

are random vectors,

and

are individual learning factor and group learning factor, respectively, and

is a constant linear descent to balance global or local search

The particle potential well center attractor is then calculated

Quantum leap operation further update location parameters

where

,

has an initial value of 1 and decays generation by generation.

Subsequently, elite crossover and mutation operations of the GA are employed to enhance diversity. The

elite individuals, selected and ranked according to the fitness values of their personal best positions (

), will undergo arithmetic crossover operations in randomly assigned pairs.

where

is a randomly generated weighting vector, and

and

represent two parent generations. Gaussian perturbation is then applied to each dimension of the offspring with mutation probability

where

is the standard deviation of the mutation. The newly generated offspring then replace the worst-performing individuals in the current population

, thereby preserving high-quality solutions while enhancing diversity.

The pseudocode for the joint algorithm is shown in the Algorithm 1. In this study, the dimension D is 3, the number of particles is 500, the number of iterations is 30, is 0.9, is 0.4, and are 0.5, is 0.15, and is 0.05, which are the optimal determination by try-and-error.

3. Experiment Validation

3.1. Simulation Experiments

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted some numerical experiments. In simulation experiments, the rotational measurement plane is defined at

, with the z-axis oriented vertically downward. Each experiment generates 4 full rotation cycles, with 200 measurement points per cycle. The magnetic anomaly signal is simulated using (

4), and Gaussian white noise is added at a specified signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The SNR is defined as

dB, where the S and N are the peak-to-peak values of the signal and noise. The inclination and declination angles of the target vary uniformly within the ranges

and

, respectively, and the magnetic moment magnitude ranges from 5 to 15 A·m

2. The detection region is bounded by

,

, and

. The target coordinates is randomly and uniformly distributed within this area.

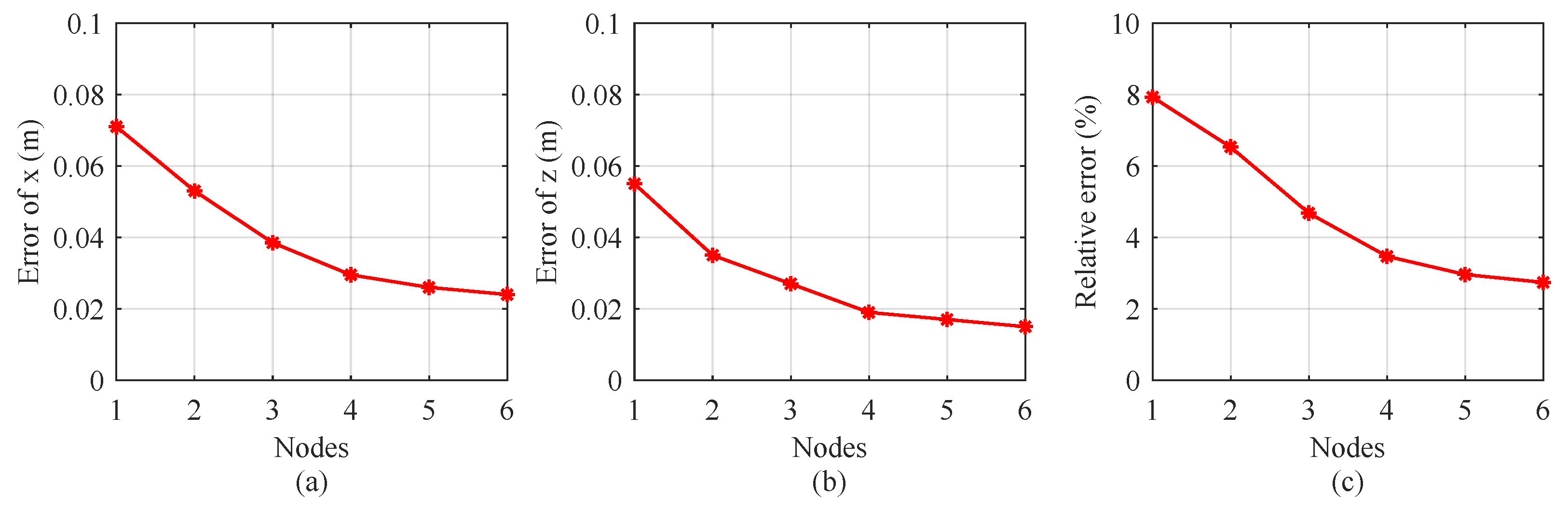

To evaluate the impact of the number of sensor nodes on the localization accuracy of a single target, a series of Monte Carlo simulations were conducted at SNR of 5 dB, as shown in

Figure 2. In the experiment, sensors were uniformly distributed along radial lines extending from the rotation center within a 4 m × 4 m area.

Figure 2 (a) and

Figure 2 (b) present the positioning errors averaged over 1000 trials in the x-direction and z-direction, respectively. Since the error distribution in the y-direction is similar to that in the x-direction, the y-direction error is not displayed.

Figure 2 (c) shows the relative magnetic moment error calculated by inversion based on the positioning results. The results indicate that as the number of sensor nodes increases, both the localization error and the magnetic moment error gradually decrease. With four sensor nodes, the average positioning errors in the x-direction and z-direction are 0.03 m and 0.02 m, respectively, and a relative magnetic moment error of 3.47%. Before the number of nodes reaches four, the errors decrease rapidly; thereafter, the error decreases slowly. Therefore, in a 4 m × 4 m area, using four nodes for localizing the target is most appropriate.

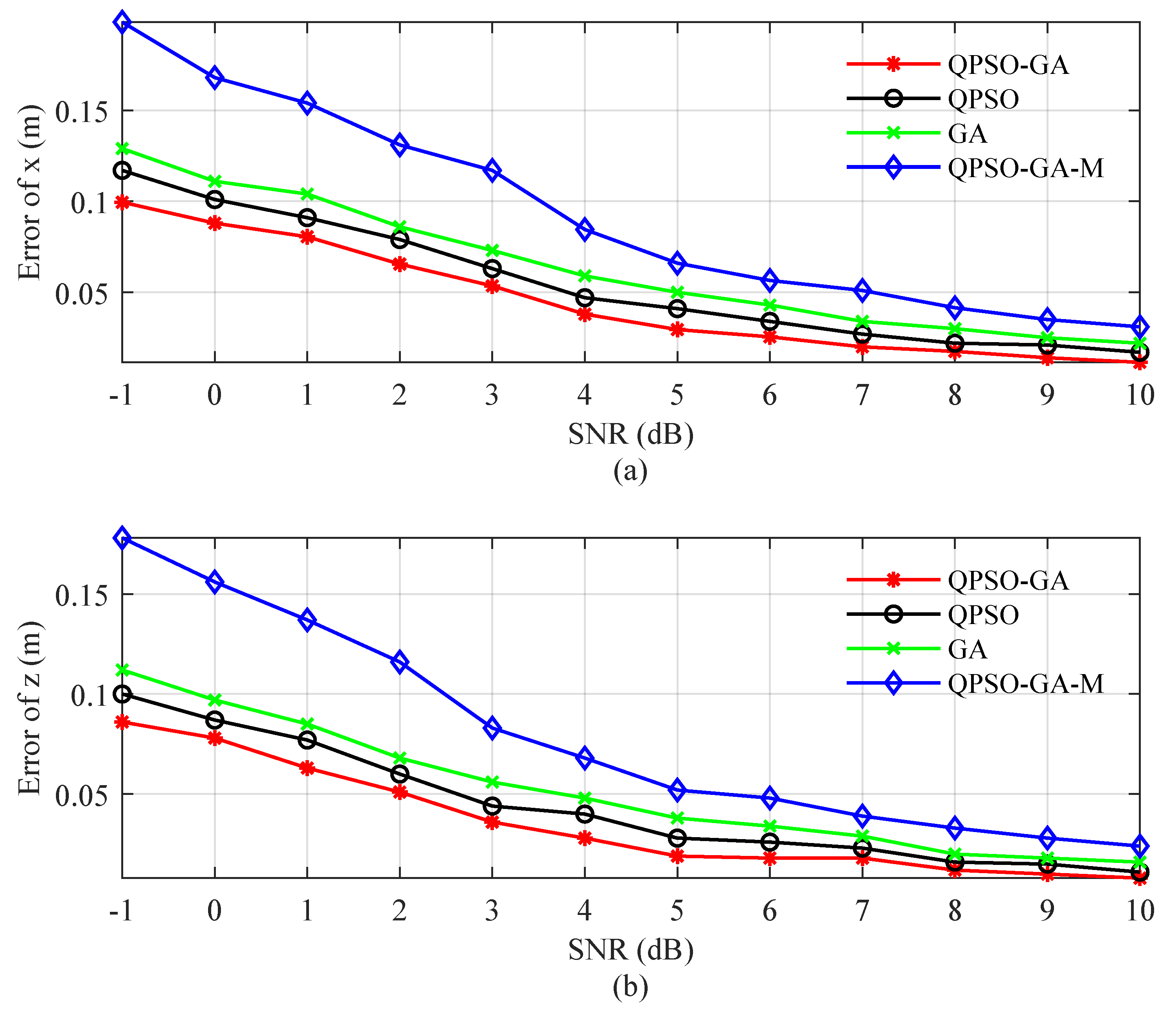

In

Figure 3, we performed 1000 Monte Carlo simulations at each SNR to compare the performance of our algorithm with other algorithms. The algorithms used for comparison are: the quantum particle swarm optimization (QPSO) and the genetic algorithm (GA), both of which estimate target coordinates with the proposed fitness function. Additionally, without eliminating magnetic moments, a variant of the QPSO-GA algorithm, denoted as QPSO-GA-M, is applied to simultaneously estimate both the target coordinates and magnetic moments. In this setup, four sensors are used to detect a single target, positioned at distances of 0.5 m, 1 m, 1.5 m, and 2 m from the center of rotation, respectively. The average positioning errors in the x-direction and z-direction are shown in

Figure 3(a) and

Figure 3(b). Experimental results show that the proposed algorithm achieves the smallest estimation error among all comparison methods, particularly at low SNRs. Compared to the QPSO-GA-M algorithm, the proposed method significantly reduces errors, demonstrating the benefit of reducing the number of unknowns by eliminating the magnetic moment. Furthermore, across all SNR levels, the proposed algorithm consistently outperforms both QPSO and GA algorithms, confirming its effective integration of the strengths of both algorithms to achieve higher estimation accuracy and stronger robustness.

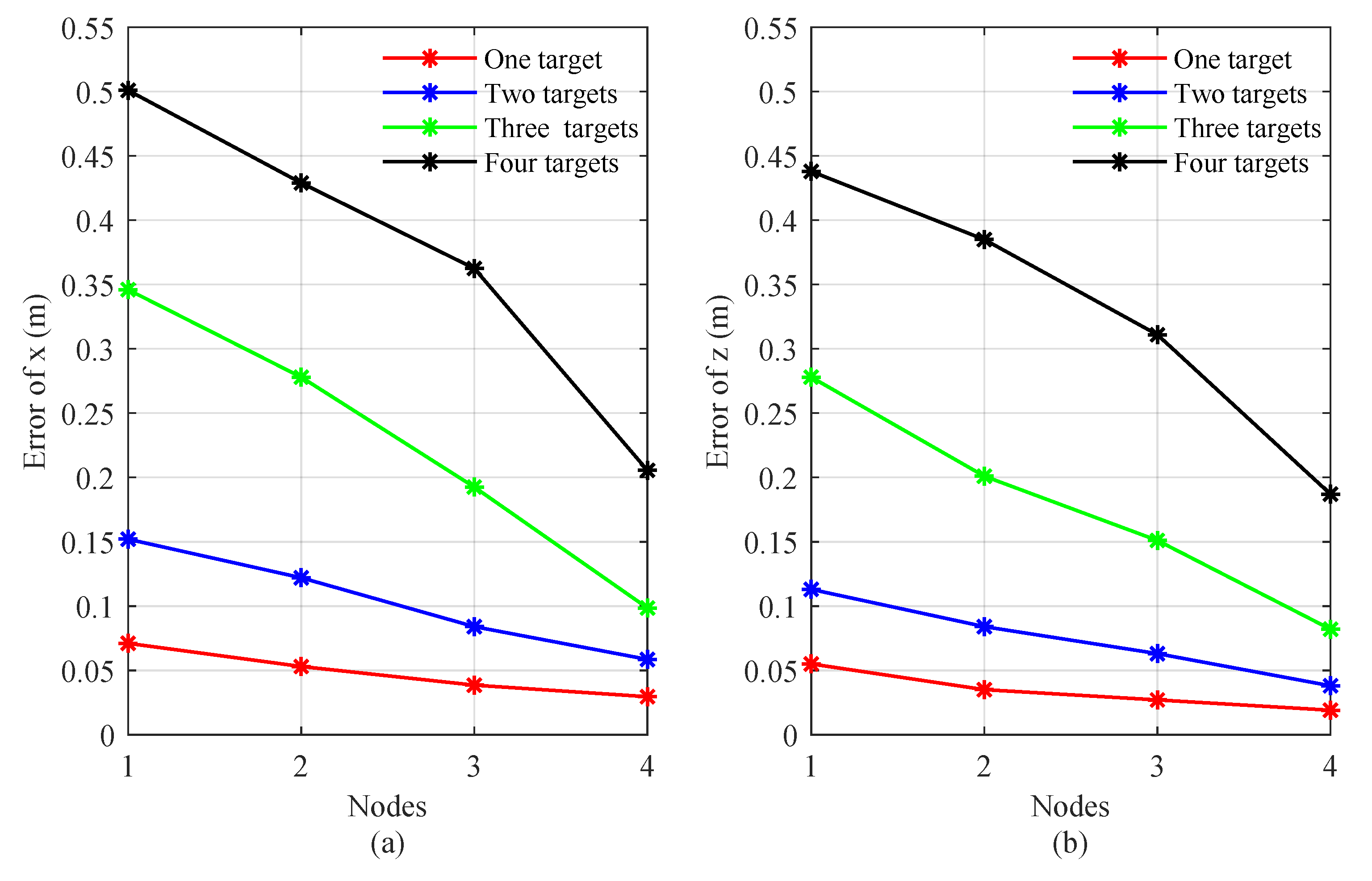

In multi-target localization tasks, the number of sensors and targets are both critical factors influencing localization accuracy. To systematically investigate the relationship between these factors, we designed a simulation experiment as shown in

Figure 4, which includes multiple configuration schemes, such as one sensor detecting one to four targets, two sensors detecting one to four targets, and so forth. For each sensor-target configuration, 1000 Monte Carlo experiments were conducted.

Figure 4(a) and

Figure 4(b) present the average localization errors in the x- and z-directions, respectively. The results indicate that when the number of sensors is fixed, the localization error increases with the number of targets; conversely, when the number of targets is fixed, the error decreases as the number of sensors increases. Overall, higher localization accuracy is achieved when the number of sensors exceeds the number of targets. To ensure optimal performance, it is recommended to use at least two more sensors than the number of targets.

3.2. Field Experiments

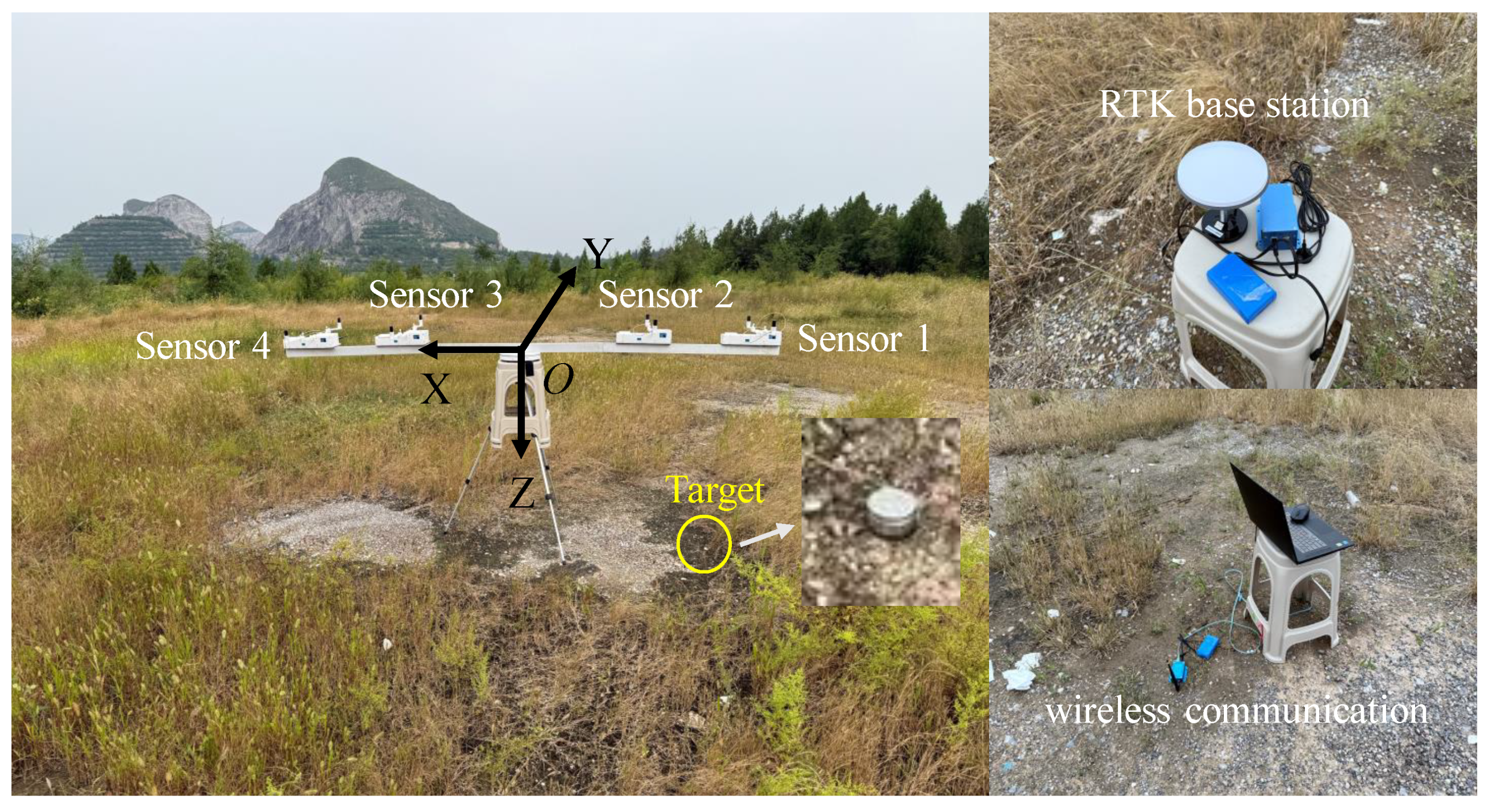

The field experiment was carried out in the suburbs of Beijing, selected for its minimal environmental electromagnetic interference, as shown in

Figure 5. The measurement platform consists of four core components: an automatically rotating non-magnetic track, four Bartington Mag649FLL fluxgate sensors, a Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) base station, and a wireless communication module. The sensors were mounted on the track to collect three-axis magnetic field data, attitude angles, and GPS positioning information. The RTK base station provided high-precision reference coordinates to enhance the positioning accuracy of the sensor nodes, while the wireless communication module facilitated data transmission and command distribution between the host computer and the sensors. During rotation, the magnetic field data and GPS information collected by the sensors at different positions were transmitted in real-time to the host computer, ensuring data synchronization and integrity.

Firstly, we performed an experiment for localizing a single target. The experimental setup is illustrated in

Figure 5. The target was a circular iron block with a diameter of approximately 5 cm, placed directly on a flat ground surface for ease of placement and positioning. A coordinate system was established with the rotation center as the origin

O: the x-axis aligned with geographic north, the y-axis pointing east, and the z-axis is perpendicular downward, with the rotational measurement plane corresponding to

. The measurement area was set to

,

, and

. The target was located at coordinates (-1.1, 0, 0.85) m. Magnetic field data were collected through six rotations to support subsequent localization analysis.

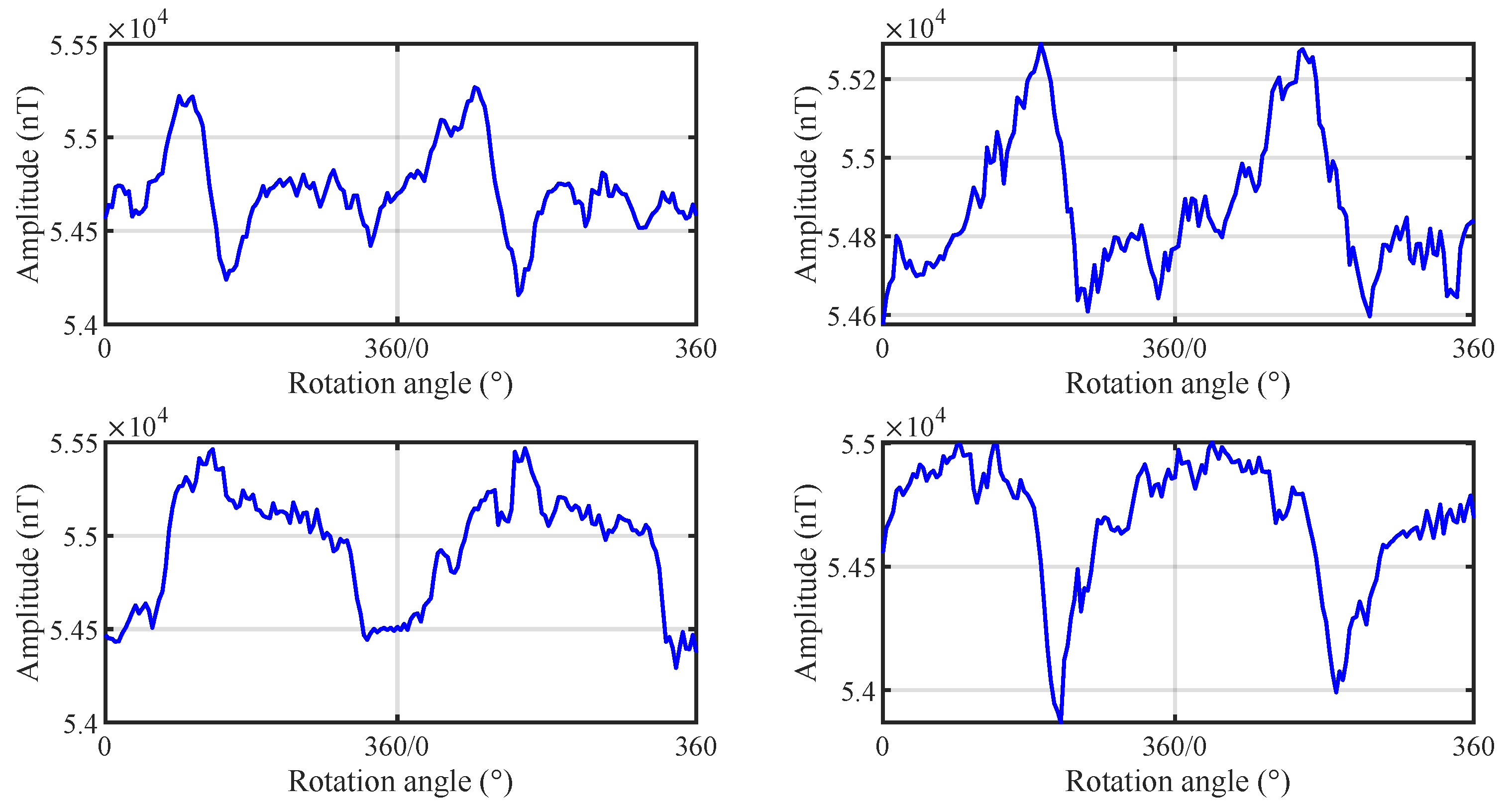

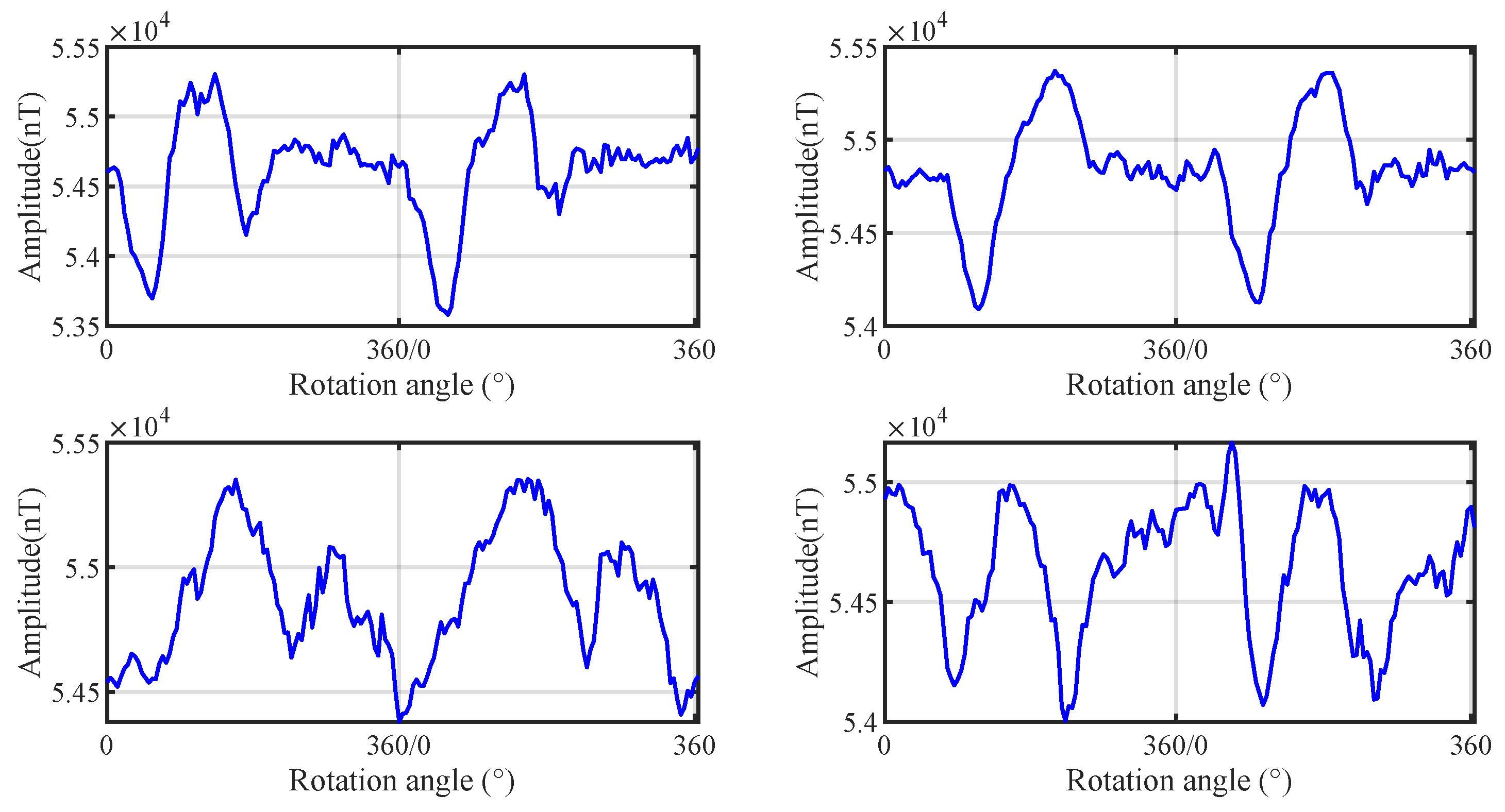

Figure 6 shows a segment of the total magnetic field measured by four sensor nodes in the single-target localization experiment, containing two complete cycles. The measured magnetic field exhibits distinct periodic variations with relatively clear anomaly signals.

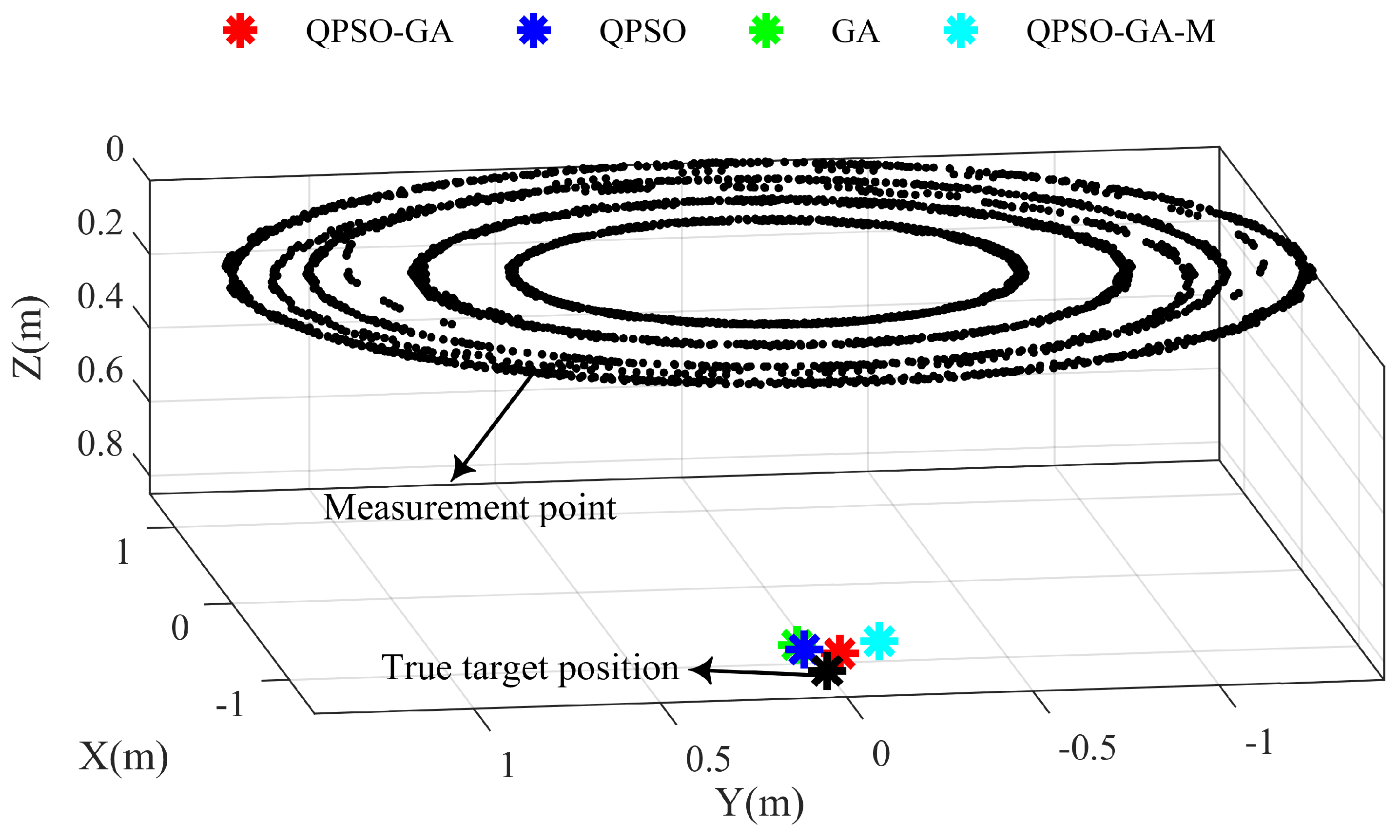

Figure 7 illustrates the estimated target positions obtained by different algorithms. It can be observed that the coordinates estimated by the proposed algorithm are closest to the true target position compared to other algorithms. The corresponding localization errors are summarized in

Table 1. Our algorithm achieves localization errors of less than 0.06 m in the x-, y-, and z-directions, outperforming the other compared algorithms and highlighting the effectiveness and advantage of the joint algorithm in real-world detection. Furthermore, the target magnetic moment obtained through inversion is 10.519 A·m

2, and its relative error can be evaluated with reference to the error statistics of magnetic moment estimation from the simulation experiments.

Subsequently, we carried out an experiment for localization of two targets.

Figure 8 shows the experimental scene, where the coordinates of the two targets are (1.0, -0.2, 0.85) m and (-0.55, 0.85, 0.85) m, respectively.

Figure 9 displays a segment of the measured total magnetic field, containing two cycles. Compared to the single-target case, the magnetic field within each cycle exhibits multiple superimposed peak characteristics.

Figure 10 presents the corresponding localization results, indicating that the estimated positions are close to the true target positions. The localization errors for the two targets are summarized in

Table 2. In the 4 m × 4 m measurement area, the average localization errors in the x-, y-, and z-directions are all less than 10 centimeters, demonstrating that the proposed algorithm can accurately estimate target positions in practical multi-target localization tasks. Compared to the single-target localization case, the error increases slightly, primarily due to the increased number of unknown parameters to be estimated.

4. Concluding Remarks

This paper proposes an alternative scheme for locating buried magnetic targets based on a rotating magnetic sensor array and a joint optimization algorithm. Given the instability and inefficiency of row scanning mode on rugged terrain, we adopt a rotating scanning measurement approach. To reduce the number of unknown parameters and improve positioning accuracy, the magnetic moment and the geomagnetic field are eliminated during the modeling process. To further enhance the accuracy of target position estimation, we integrate the Quantum Particle Swarm Optimization (QPSO) algorithm with the Genetic Algorithm (GA), proposing a joint optimization algorithm named QPSO-GA. This algorithm combines the fast convergence and local refinement capabilities of QPSO with the global exploration and population diversity advantages of GA. Simulations and field experiments were conducted to comprehensively evaluate the localization performance of the proposed scheme. The results demonstrate that within a 4 m × 4 m measurement area, the proposed measurement setting and algorithm achieve an average localization error of less than 10 centimeters in multi-sensor, multi-target scenarios, meeting general application requirements. Furthermore, the measurement setting can be deployed on low-magnetic unmanned platforms, making it suitable for large-scale rapid scanning and mapping tasks. For high-precision detection of small targets, replacing fluxgate sensors with optical pump magnetometers can further enhance measurement accuracy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.X.; methodology, Z.Y.; software, Z.Y.; validation, Z.Y. and X.L.; formal analysis, Z.Y. and X.L.; investigation, Z.Y. and X.L.; experiment data, X.L. and C.D.; writing-original draft preparation, Z.Y.; writing-review and editing, M.X.; supervision, M.X.; funding acquisition, M.X. and C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grants No. 62231001, No. 62101010, and No. 61531001.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Owen, M.; McNamara, A.; Panchal, J. The risk of unexploded ordnance on construction sites in London, UK. Environmental Geotechnics. 2021, 8, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Bigl, S.; Packer, B. Condition of in situ unexploded ordnance. Science of The Total Environment. 2015, 505, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Miao, P.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, E. A brief review of magnetic anomaly detection. Measurement Science and Technology. 2021, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Liu, Z.; Hu, X. Theories, applications, and expectations for magnetic anomaly detection technology: a review. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2023, 23, 17868–17882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Feng, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhu, W.; Fang, G. An innovative magnetic anomaly detection algorithm based on signal modulation. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 2020, 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, J.; Du, C.; Peng, X.; Guo, H. An unmanned aerial vehicle magnetic detection system for archaeological exploration. Electromagnetic Science. 2025, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, H.; Wei, Z.; Xie, Y. A closed-form formula for magnetic dipole localization by measurement of its magnetic field vector and magnetic gradient tensor. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 2020, 499, 166274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, H.; Ma, T.; Pei, D.; Sun, H. A novel magnetic dipole inversion method based on tensor geometric invariants. AIP Advances. 2020, 10, 045131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Li, F.; Liu, W. A new magnetic target localization method based on two-point magnetic gradient tensor. Remote Sensing. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Ge, J.; Dong, H.; Liu, Z. Quantitative analysis of the measurable areas of differential magnetic gradient tensor systems for unexploded ordnance detection. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2021, 21, 5952–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Shi, Z.; Fan, H. Multi-target magnetic positioning using SAFCM clustering and invariants-improved tilt angle. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing. 2022, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, W.E.; Gamey, T.J.; Bell, D.T.; Beard, L.P.; Sheehan, J.R.; Norton, J.; Holladay, J.S.; Lee, J.L.C. Historical development and performance of airborne magnetic and electromagnetic systems for mapping and detection of unexploded ordnance. Journal of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics. 2012, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Xia, M.; Huang, S.; Xu, Z.; Peng, X.; Guo, H. Detection of a moving magnetic dipole target using multiple scalar magnetometers. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters. 2017, 14, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassot, G.; Blanpain, R.; Flament, B.; Jauffret, C. Process for determining the position of a moving object using magnetic gradientmetric measurements. U.S. Patent 6,539,327, 25, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Tang, J.; Ren, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhou, C.; Xiao, X.; Zhao, T. Multiple underwater objects localization with magnetic gradiometry. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2019, 16, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Kang, X.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, C.; Kang, C. A fast linear algorithm for magnetic dipole localization using total magnetic field gradient. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2018, 18, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, F.F.; Barbosa, V.C. Reliable Euler deconvolution estimates throughout the vertical derivatives of the total-field anomaly. Computers & Geosciences. 2020, 138, 104436. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K.; Li, Y.; Nabighian, M. Automatic detection of UXO magnetic anomalies using extended Euler deconvolution. GEOPHYSICS. 2010, 75, G13–G20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Wang, S.; Dong, H.; Liu, H.; Zhou, D.; Wu, S.; Luo, W.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, H. Real-time detection of moving magnetic target using distributed scalar sensor based on hybrid algorithm of particle swarm optimization and Gauss–Newton method. IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 10717–10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, R.; Geron, N.; Weiss, E.; Ram-Cohen, T. Ferromagnetic mass localization in check point configuration using a levenberg marquardt algorithm. Sensors 2009, 9, 8852–8862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimi, R.; Weiss, E.; Ram-Cohen, T.; Geron, N.; Yogev, I. A dedicated genetic algorithm for localization of moving magnetic objects. Sensors 2015, 15, 23788–23804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheinker, A.; Lerner, B.; Salomonski, N.; Ginzburg, B.; Frumkis, L.; Kaplan, B.Z. Localization and magnetic moment estimation of a ferromagnetic target by simulated annealing. Measurement Science and Technology 2007, 18, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarotskii, V.A. Optimum detection of magnetic dipoles. Measurement techniques. 1992, 35, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Kaur, B.; Agarwal, P. Quantum inspired particle swarm optimization with guided exploration for function optimization. Applied Soft Computing. 2021, 102, 107122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.L.; Yang, S.; Ni, G.; Huang, J. A quantum-based particle swarm optimization algorithm applied to inverse problems. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 2013, 49, 2069–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Cannings, C.; Sheehan, N. An evaluation of the application of the genetic algorithm to the problem of ordering genetic loci on human chromosomes using radiation hybrid data. Mathematical Medicine and Biology: A Journal of the IMA. 1997, 14, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K.; Narasimha Murty, M. Genetic K-means algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics). 1999, 29, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).