Submitted:

09 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

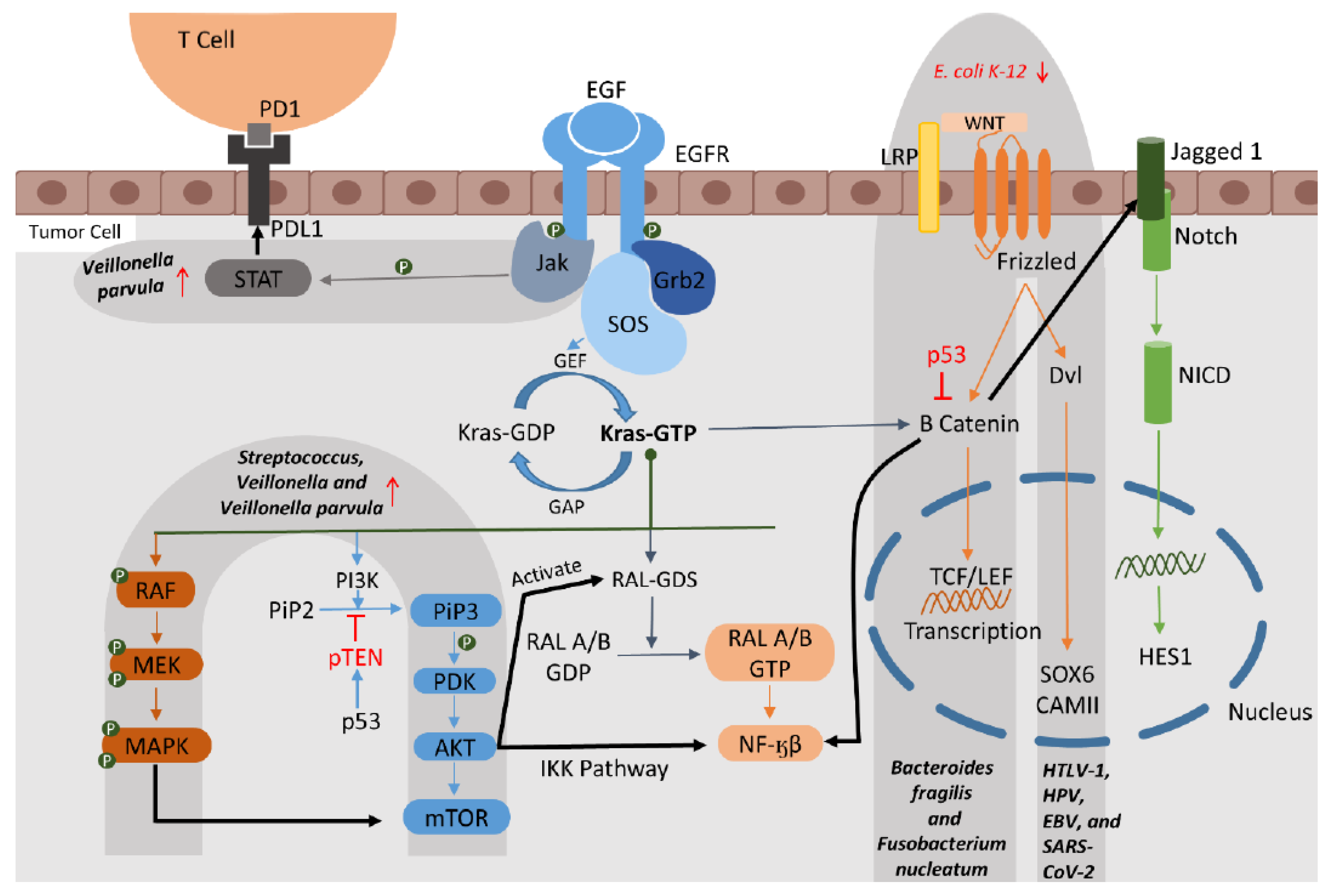

Respiratory tract cancers (RTCs), including lung, laryngeal, nasopharyngeal, and tracheal cancers, are among the most common cancer types. These cancers show difficulties in the case of early diagnosis and treatment monitoring. The microbiome, the community of microbes living in a single area of the body, is associated with cancer and offers potential for developing non-invasive diagnostic tools and probiotic therapies. Microbiome dysbiosis affects both the tumor and the immune microenvironment. The major pathways of RTCs, including EGFR, ALK, KRAS, STAT3, WNT, etc., are affected by the dysbiosis that occurs during cancer progression. Several microbial species have also been associated with treatment outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), chemotherapy, and anti-PD-1 therapy. Microbes such as Alistipes indistinctus, Alistipes shahii, Barnesiella viscericola, Streptococcus salivarius, Parabacteroides, and Faecalibacterium, along with genera like Bifidobacterium, Collinsella, Veillonella, and families/orders like Actinomycetales, Odoribacteraceae, and Selenomonadales, have shown positive associations with overall survival, progression-free survival, and improved treatment responses. Conventional biomarkers for RTCs have greatly improved diagnosis and monitoring. Still, they suffer from limitations such as low sensitivity in early-stage, intrusive sample procedures, and a lack of specificity. In contrast, gut, airway, and oral microbiota have emerged as promising non-invasive biomarkers with established associations to cancer progression, metabolic pathways, immune responses, and treatment monitoring. Moreover, non-invasive sampling methods like stool, sputum, and oral swabs offer improved patient comfort and early detection opportunities. In this mini review, we explore global research on human microbiomes as potential diagnostic or therapeutic biomarkers and their associations with RTCs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Microbiomes and Their Relevance as Biomarkers

2.1. Association of Cancer Pathways and Microbiomes in RTCs

2.1.1. The EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor) Pathway

2.1.2. The KRAS (Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog) Pathway

2.1.3. The MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase) and ERK Pathway

2.1.4. The VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) Pathway

2.1.5. The WNT Pathways

2.2. Association of Transcription Factors (TFs) and Microbiomes in RTC

2.3. Association of Metabolites and Microbiomes in RTC

3. Microbiomes as Diagnostic and Treatment Biomarkers: Recent Empirical Data

4. Emerging Next-Generation Approaches

5. Conclusion

Funding statement

Ethics statement

Data access statement

Conflict of interest

Statement of translational relevance

References

- Dolgushin M, Kornienko V, Pronin I. Lung Cancer (LC). In: Dolgushin M, Kornienko V, Pronin I, editors. Brain Metastases: Advanced Neuroimaging. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 99–141.

- Patel J, Hafzah H. Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Consult: Solid Tumors & Supportive Care. 2023;1:97–104.

- Wahab MRA, Palaniyandi T, Ravi M, viswanathan S, Baskar G, Surendran H, et al. Biomarkers and biosensors for early cancer diagnosis, monitoring and prognosis. Pathology - Research and Practice. 2023;250:154812.

- Neagoe C-X-R, Ionică M, Neagoe OC, Trifa AP. The Influence of Microbiota on Breast Cancer: A Review. Cancers. 2024;16(20):3468.

- Prescott SL. History of medicine: Origin of the term microbiome and why it matters. Human Microbiome Journal. 2017;4:24–5.

- Hora J, Mani I. Metagenomics in the Census of Microbial Diversity. In: Mani I, Singh V, editors. Multi-Omics Analysis of the Human Microbiome: From Technology to Clinical Applications. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2024. p. 89–113.

- Mino-Kenudson M, Schalper K, Cooper W, Dacic S, Hirsch FR, Jain D, et al. Predictive Biomarkers for Immunotherapy in Lung Cancer: Perspective From the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Pathology Committee. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(12):1335–54.

- Qian X, Meng Q-H. Circulating lung cancer biomarkers: From translational research to clinical practice. Tumor Biology. 2024;46(s1):S27–S33.

- Thapa R, Moglad E, Goyal A, Bhat AA, Almalki WH, Kazmi I, et al. Deciphering NF-kappaB pathways in smoking-related lung carcinogenesis. EXCLI journal. 2024;23:991.

- Chen Y, Huang Y, Ding X, Yang Z, He L, Ning M, et al. A Multi-Omics Study of Familial Lung Cancer: Microbiome and Host Gene Expression Patterns. Front Immunol. 2022;13:827953.

- Ding H, Chen Y, Zhao Y, Zhu L, Huang H, Liu C, et al. The clinical significance and function of EGFR mutation in TKI treatments of NSCLC patients. Cancer Biomarkers. 2022;35(1):119–25.

- Liu W, Peng L, Chen L, Wan J, Lou S, Yang T, et al. Skin microbial dysbiosis is a characteristic of systemic drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema-like lesions induced by EGFR inhibitor. Heliyon. 2023;9(11):e21690.

- Stella GM, Scialò F, Bortolotto C, Agustoni F, Sanci V, Saddi J, et al. Pragmatic Expectancy on Microbiota and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Narrative Review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(13).

- Ihle NT, Byers LA, Kim ES, Saintigny P, Lee JJ, Blumenschein GR, et al. Effect of KRAS oncogene substitutions on protein behavior: implications for signaling and clinical outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(3):228–39.

- Tsay JJ, Wu BG, Sulaiman I, Gershner K, Schluger R, Li Y, et al. Lower Airway Dysbiosis Affects Lung Cancer Progression. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(2):293–307.

- Roa P, Bremer NV, Foglizzo V, Cocco E. Mutations in the Serine/Threonine Kinase BRAF: Oncogenic Drivers in Solid Tumors. Cancers. 2024;16(6):1215.

- Otálora-Otálora BA, Payán-Gómez C, López-Rivera JJ, Pedroza-Aconcha NB, Aristizábal-Guzmán C, Isaza-Ruget MA, et al. Global transcriptomic network analysis of the crosstalk between microbiota and cancer-related cells in the oral-gut-lung axis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1425388.

- Zheng Y, Fang Z, Xue Y, Zhang J, Zhu J, Gao R, et al. Specific gut microbiome signature predicts the early-stage lung cancer. Gut Microbes. 2020;11(4):1030–42.

- Chen Q, Hou K, Tang M, Ying S, Zhao X, Li G, et al. Screening of potential microbial markers for lung cancer using metagenomic sequencing. Cancer Med. 2023;12(6):7127–39.

- Wang D, Cheng J, Zhang J, Zhou F, He X, Shi Y, et al. The Role of Respiratory Microbiota in Lung Cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(13):3646–58.

- Krishnamurthy N, Kurzrock R. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in cancer: Update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;62:50–60.

- Shen X, Gao C, Li H, Liu C, Wang L, Li Y, et al. Natural compounds: Wnt pathway inhibitors with therapeutic potential in lung cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1250893.

- Wang X, Yang Y, Huycke MM. Commensal-infected macrophages induce dedifferentiation and reprogramming of epithelial cells during colorectal carcinogenesis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(60):102176–90.

- Zhang J, Wang Y, Yuan B, Qin H, Wang Y, Yu H, et al. Identifying key transcription factors and immune infiltration in non-small-cell lung cancer using weighted correlation network and Cox regression analyses. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1112020.

- Khan AQ, Hasan A, Mir SS, Rashid K, Uddin S, Steinhoff M. Exploiting transcription factors to target EMT and cancer stem cells for tumor modulation and therapy. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2024;100:1–16.

- Zhang X, Zhang M, Sun H, Wang X, Wang X, Sheng W, et al. The role of transcription factors in the crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor cells. Journal of Advanced Research. 2025;67:121–32.

- Li WT, Iyangar AS, Reddy R, Chakladar J, Bhargava V, Sakamoto K, et al. The Bladder Microbiome Is Associated with Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Muscle Invasive Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(15).

- Kolisnik T, Sulit AK, Schmeier S, Frizelle F, Purcell R, Smith A, et al. Identifying important microbial and genomic biomarkers for differentiating right- versus left-sided colorectal cancer using random forest models. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):647.

- Wang D, Zhu X, Tang X, Li H, Yizhen X, Chen D. Auxiliary antitumor effects of fungal proteins from Hericium erinaceus by target on the gut microbiota. J Food Sci. 2020;85(6):1872–90.

- Li X, Shang S, Wu M, Song Q, Chen D. Gut microbial metabolites in lung cancer development and immunotherapy: Novel insights into gut-lung axis. Cancer Letters. 2024;598:217096.

- Ma Z, Li L. Identifications of the potential in-silico biomarkers in lung cancer tissue microbiomes. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2024;183:109231.

- Zhao F, An R, Wang L, Shan J, Wang X. Specific Gut Microbiome and Serum Metabolome Changes in Lung Cancer Patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:725284.

- Vernocchi P, Gili T, Conte F, Del Chierico F, Conta G, Miccheli A, et al. Network Analysis of Gut Microbiome and Metabolome to Discover Microbiota-Linked Biomarkers in Patients Affected by Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(22).

- Kaiko GE, Ryu SH, Koues OI, Collins PL, Solnica-Krezel L, Pearce EJ, et al. The Colonic Crypt Protects Stem Cells from Microbiota-Derived Metabolites. Cell. 2016;165(7):1708–20.

- Zhou M, Wang Q, Lu X, Zhang P, Yang R, Chen Y, et al. Exhaled breath and urinary volatile organic compounds (VOCs) for cancer diagnoses, and microbial-related VOC metabolic pathway analysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2024;110(3):1755–69.

- Qian X, Zhang HY, Li QL, Ma GJ, Chen Z, Ji XM, et al. Integrated microbiome, metabolome, and proteome analysis identifies a novel interplay among commensal bacteria, metabolites and candidate targets in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(6):e947.

- Huang J, Liu D, Wang Y, Liu L, Li J, Yuan J, et al. Ginseng polysaccharides alter the gut microbiota and kynurenine/tryptophan ratio, potentiating the antitumour effect of antiprogrammed cell death 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (anti-PD-1/PD-L1) immunotherapy. Gut. 2022;71(4):734–45.

- Zhu Z, Cai J, Hou W, Xu K, Wu X, Song Y, et al. Microbiome and spatially resolved metabolomics analysis reveal the anticancer role of gut Akkermansia muciniphila by crosstalk with intratumoral microbiota and reprogramming tumoral metabolism in mice. Gut Microbes. 2023;15(1):2166700.

- Khan FH, Bhat BA, Sheikh BA, Tariq L, Padmanabhan R, Verma JP, et al. Microbiome dysbiosis and epigenetic modulations in lung cancer: From pathogenesis to therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86(Pt 3):732–42.

- Hagihara M, Kato H, Yamashita M, Shibata Y, Umemura T, Mori T, et al. Lung cancer progression alters lung and gut microbiomes and lipid metabolism. Heliyon. 2024;10(1):e23509.

- Chen S, Gui R, Zhou XH, Zhang JH, Jiang HY, Liu HT, et al. Combined Microbiome and Metabolome Analysis Reveals a Novel Interplay Between Intestinal Flora and Serum Metabolites in Lung Cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:885093.

- Lu X, Xiong L, Zheng X, Yu Q, Xiao Y, Xie Y. Structure of gut microbiota and characteristics of fecal metabolites in patients with lung cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1170326.

- Fang G, Wang S, Chen Q, Luo H, Lian X, Shi D. Time-restricted feeding affects the fecal microbiome metabolome and its diurnal oscillations in lung cancer mice. Neoplasia. 2023;45:100943.

- Liu B, Li Y, Suo L, Zhang W, Cao H, Wang R, et al. Characterizing microbiota and metabolomics analysis to identify candidate biomarkers in lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1058436.

- Zeng J, Yi B, Chang R, Li J, Zhu J, Yu Z, et al. The Causal Effect of Gut Microbiota and Plasma Metabolome on Lung Cancer and the Heterogeneity across Subtypes: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J Pers Med. 2024;14(5).

- Lee PJ, Hung CM, Yang AJ, Hou CY, Chou HW, Chang YC, et al. MS-20 enhances the gut microbiota-associated antitumor effects of anti-PD1 antibody. Gut Microbes. 2024;16(1):2380061.

- Zhou Y, Chen E, Wu X, Hu Y, Ge H, Xu P, et al. Rational lung tissue and animal models for rapid breath tests to determine pneumonia and pathogens. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9(11):5116–26.

- Sun Y, Liu Y, Li J, Tan Y, An T, Zhuo M, et al. Characterization of Lung and Oral Microbiomes in Lung Cancer Patients Using Culturomics and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11(3):e0031423.

- Lu H, Gao NL, Tong F, Wang J, Li H, Zhang R, et al. Alterations of the Human Lung and Gut Microbiomes in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinomas and Distant Metastasis. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9(3):e0080221.

- Zhang C, Wang J, Sun Z, Cao Y, Mu Z, Ji X. Commensal microbiota contributes to predicting the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(8):3005–17.

- Derosa L, Iebba V, Silva CAC, Piccinno G, Wu G, Lordello L, et al. Custom scoring based on ecological topology of gut microbiota associated with cancer immunotherapy outcome. Cell. 2024;187(13):3373–89.e16.

- Kim G, Park C, Yoon YK, Park D, Lee JE, Lee D, et al. Prediction of lung cancer using novel biomarkers based on microbiome profiling of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):1691.

- Liu Y, Liang Y, Li Q, Li Q. Comprehensive analysis of circulating cell-free RNAs in blood for diagnosing non-small cell lung cancer. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:4238–51.

- Liu Q, Zhang W, Pei Y, Tao H, Ma J, Li R, et al. Gut mycobiome as a potential non-invasive tool in early detection of lung adenocarcinoma: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):409.

- Chen H, Ma Y, Xu J, Wang W, Lu H, Quan C, et al. Circulating microbiome DNA as biomarkers for early diagnosis and recurrence of lung cancer. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5(4):101499.

- Jin J, Gan Y, Liu H, Wang Z, Yuan J, Deng T, et al. Diminishing microbiome richness and distinction in the lower respiratory tract of lung cancer patients: A multiple comparative study design with independent validation. Lung Cancer. 2019;136:129–35.

- Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong CPM, Alou MT, Daillère R, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359(6371):91–7.

- Takada K, Buti S, Bersanelli M, Shimokawa M, Takamori S, Matsubara T, et al. Antibiotic-dependent effect of probiotics in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Eur J Cancer. 2022;172:199–208.

- Dora D, Ligeti B, Kovacs T, Revisnyei P, Galffy G, Dulka E, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with Anti-PD1 immunotherapy show distinct microbial signatures and metabolic pathways according to progression-free survival and PD-L1 status. Oncoimmunology. 2023;12(1):2204746.

- Song P, Yang D, Wang H, Cui X, Si X, Zhang X, et al. Relationship between intestinal flora structure and metabolite analysis and immunotherapy efficacy in Chinese NSCLC patients. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11(6):1621–32.

- Kwok B, Wu BG, Kocak IF, Sulaiman I, Schluger R, Li Y, et al. Pleural fluid microbiota as a biomarker for malignancy and prognosis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):2229.

- Ni B, Kong X, Yan Y, Fu B, Zhou F, Xu S. Combined analysis of gut microbiome and serum metabolomics reveals novel biomarkers in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1091825.

- Zheng L, Sun R, Zhu Y, Li Z, She X, Jian X, et al. Lung microbiome alterations in NSCLC patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):11736.

- Otoshi T, Nagano T, Park J, Hosomi K, Yamashita T, Tachihara M, et al. The Gut Microbiome as a Biomarker of Cancer Progression Among Female Never-smokers With Lung Adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2022;42(3):1589–98.

- Zheng X, Sun X, Liu Q, Huang Y, Yuan Y. The Composition Alteration of Respiratory Microbiota in Lung Cancer. Cancer Invest. 2020;38(3):158–68.

- Cameron SJS, Lewis KE, Huws SA, Hegarty MJ, Lewis PD, Pachebat JA, et al. A pilot study using metagenomic sequencing of the sputum microbiome suggests potential bacterial biomarkers for lung cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177062.

- Qiao H, Tan XR, Li H, Li JY, Chen XZ, Li YQ, et al. Association of Intratumoral Microbiota With Prognosis in Patients With Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma From 2 Hospitals in China. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(9):1301–9.

- Yu S, Chen J, Zhao Y, Yan F, Fan Y, Xia X, et al. Oral-microbiome-derived signatures enable non-invasive diagnosis of laryngeal cancers. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):438.

- Lu YT, Hsin CH, Chuang CY, Huang CC, Su MC, Wen WS, et al. Microbial Dysbiosis in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Pilot Study on Biomarker Potential. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2024;53:19160216241304365.

- Dohlman AB, Klug J, Mesko M, Gao IH, Lipkin SM, Shen X, et al. A pan-cancer mycobiome analysis reveals fungal involvement in gastrointestinal and lung tumors. Cell. 2022;185(20):3807–22.e12.

- Zhang Z, Xu D, Fang J, Wang D, Zeng J, Liu X, et al. In Situ Live Imaging of Gut Microbiota. mSphere. 2021;6(5):e0054521.

- Sorlin AM, López-Álvarez M, Biboy J, Gray J, Rabbitt SJ, Rahim JU, et al. Peptidoglycan-Targeted [(18)F]3,3,3-Trifluoro-d-alanine Tracer for Imaging Bacterial Infection. JACS Au. 2024;4(3):1039–47.

- Hu K, Shang J, Xie L, Hanyu M, Zhang Y, Yang Z, et al. PET Imaging of VEGFR with a Novel (64)Cu-Labeled Peptide. ACS Omega. 2020;5(15):8508–14.

- Ordonez AA, Jain SK. Pathogen-Specific Bacterial Imaging in Nuclear Medicine. Semin Nucl Med. 2018;48(2):182–94.

- Wang Y, Zhang C, Lai J, Zhao Y, Lu D, Bao R, et al. Noninvasive PET tracking of post-transplant gut microbiota in living mice. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47(4):991–1002.

| Microbe | Pathways | Transcription_Factors | Metabolites | Cancer_Type | Association_Status |

| Papillomavirus | EGFR, MAPK | SOX4, TCF3, ETV4, and FOXM1 | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Parvimonas | EGFR | N/A | N/A | NSCLC | reported in literature |

| Prevotella | EGFR, MAPK, ERK, PI3K | N/A | Acylcarnitines, Lysophospholipids, Beta-Santalyl Acetate, Xanthines, and Theobromine, nervonic acid/all-trans-retinoic acids, Butyrate, Folate, Propionate, Acetaldehyde, Deoxycholic Acid, and Biotin | LC | reported in literature |

| Mycoplasma | EGFR | N/A | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| E. coli | EGFR, WNT, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Notch, and TGF-beta | SNAI3, KLF4, | Cysteinyl-Valine, 3-Chlorobenzoic acid, and 3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl ethanol | LC | probable association/ reported in literature |

| haemolyticus | EGFR | N/A | N/A | NSCLC | reported in literature |

| S. aureus | EGFR | N/A | Sphingosine, Cyclohexane | LC | reported in literature |

| S. enterica, Corynebacterium sp., Prevotella copri, S. epidermidis, Rhizopus oryzae, Natronolimnobius innermongolicus, Staphylococcus sciuri | EGFR | N/A | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Streptococcus | KRAS, ERK, PI3K | N/A | Butyrate, Folate, Propionate, Acetaldehyde, Deoxycholic Acid, and Biotin | LC | reported in literature |

| Veillonella | KRAS, ERK, IL-17, PI3K, MAPK, and ERK | N/A | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| HTLV-1, HPV, EBV, SARS-CoV-2 | MAPK, non-canonical WNT, IFN, VEGF | SOX4, TCF3, ETV4, and FOXM1 | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Bifidobacterium | MAPK, TNF | N/A | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Wolbachia | MAPK, ERK and PI3K | N/A | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Helicobacter pylori | VEGF | N/A | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | VEGF | N/A | Gln (glutamic acid, succinic acid, and malic acid) and adenosine (AMP, ADP, UMP, GMP, and uric acid) | LC | reported in literature |

| Enterococcus hirae | VEGF | N/A | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Wnt/β-catenin signaling | N/A | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | Wnt/β-catenin signaling | HOXC6 | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Hericium erinaceus (fungus) | N/A | FOXM1 | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | N/A | NF-KB and IL-8 | N/A | LC | reported in literature |

| Synergistes, Megasphaera, Clostridioides, Prevotellaceae, Halocella | N/A | N/A | glycerophospholipids, Acylcarnitines, Lysophospholipids, Beta-Santalyl Acetate, Xanthines, and Theobromine. | LC | reported in literature |

| Erysipelotrichaceae_UCG_003, Clostridium | N/A | N/A | glycerophospholipids | LC | reported in literature |

| Rikenellaceae | N/A | N/A | pentanoic and butyric acids | LC | reported in literature |

| Granulicatella | N/A | N/A | SCFAs (propionic, butyric, acetic, and valeric acids), lysine, and nicotinic acid, | LC | reported in literature |

| Ruminococcus gnavus, Lachnospira, Firmicutes, Fusicatenibacter | N/A | N/A | L-valine, quinic acid, 3-hydroxybenzoic acid,1-methyl hydantoin,3,4-dihydroxydrocinnamic acid, and 3,4-dihydroxy benzene acetic acid | LC | reported in literature |

| Study (Year) | Sample Type | Microbiome Source | Key Taxa Identified | Cancer Type / Stage | Context (Detection/Treatment) | Diagnostic / Prognostic Value | Methods Used | Cohort Size | PMIDs |

| Liu et al. (2019) | Fecal samples | Gut microbiome | Lower abundance in LC: Firmicutes, Actinobacteria. Higher abundance in LC: Proteobacteria, Verrucomicrobia. The ratio of two phyla (Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes) was decreased in lung cancer group 2.14 (CYF), 1.64 (CEA) and 2.18 (NSE) | Lung cancer (grouped by biomarkers: CYFRA21-1, NSE, CEA) | Detection | Alpha diversity: NSE (and CEA) vs healthy control (Shannon -35.99 P=0.0369, -31.16 P=0.0369; Simpson 38.1944, P =0.0272, 33.11364, P =0.0386). J index (39.4028 P=0.0217 and 33.07955 P=0.0437. Beta diversity: (ANOSIM, r = 0.288, P = 0.001) | 16S rRNA gene sequencing, KEGG/COG pathway analysis, alpha/beta diversity metrics | 30 lung cancer patients (divided into 3 groups) and 16 healthy controls. | 31595156 |

| Routy et al. (2018) | Fecal samples(human & mice) | Gut Microbiome | A. municiphila, E. hirae restored antibiotic induced dysbiosis, showed better treatment outcome. Alistipes indistinctus was also efficient in avatar mice to restore ICI efficacy. Ruminococcus spp., Eubacterium spp. also found to be enriched in NSCLC. | Advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and urothelial carcinoma | Treatments/ effects of FMT in ICI activity in mice model | A. muciniphila (p= 0.004) | Metagenomic shotgun sequencing, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), flow cytometry, mouse tumor models | Human: 249 patients (validation cohort of 239). Mouse: Multiple groups (5–12 mice per group). | 29097494 |

| et al. (2021) | Stool samples and serum samples for metabolites | Gut microbiota from fecal matter | Higher in LC: Enterococcus, Veillonella, Megasphaera, Clostridioides. Higher in Healthy Control (HC): Faecalibacterium, Eubacterium, Phascolarctobacterium. | Lung cancer | Detection | Tenericutes (P <0.0001) and Cyanobacteria (P = 0.0183) were significantly moreabundant in HC group, whereas Halanaerobiaeota (P = 0.0202) were in LC group. Actinomyces (P <0.0051), Veillonella (P = 0.0057), Megasphaera (P =0.0149), Enterococcus (P = 0.0183) and Clostridioides (P = 0.0202) were more abundant in LC than HC Glycerophospholipids (LysoPE 18:3 (AUC, 0.908), LysoPC 14:0 (AUC, 0.895), LysoPC 18:3 (AUC, 0.893), AcylGlcADG 66:18; AcylGlcADG (22:6/22:6/22:6) (AUC, 0.906), Acylcarnitine 11:0 (AUC, 0.854) and Hypoxanthine (AUC, 0.769) all at P<0.001. The diagnostic potential of glycerophospholipids for LC was superior to that SCC (AUC, 0.539; P = 0.56), NSE (AUC, 0.536; P = 0.58) and CYFRA21-1 (AUC, 0.592; P = 0.16). | 16S rRNA gene sequencing, LC-MS. | Microbiome: 41 LC patients, 40 healthy controls (HC). Metabolomics: 30 LC patients, 30 HC (final analysis: 27 LC, 29 HC). | 34527604 |

| Vernocchi et al. (2020) | Stool samples | Gut microbiota from fecal samples | Higher in controls: Akkermansia muciniphila (possible probiotic), Rikenellaceae, Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcaceae, Mogibacteriaceae, Clostridiaceae, Dialister, Coriobacteriaceae, Prevotellaceae. Higher in NSCLC patients: Granulicatella (associated with treatment response). Metaboiltes, higher in controls: acids (pentanoic, butyric), aldehydes (benzaldehyde, benzenacetaldehyde, 3-methyl-butanal, 2-butenal), ketones (acetone, 2-heptanone, 2-octanone), terpenes (g-terpinene, 3-carene) and p-cresol. | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | treatment | p ≤ 0.05, Network analysis and WGCNA (Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis). | 16S rRNA gene sequencing (microbiome). GC-MS and NMR spectroscopy (metabolomics). | 11 NSCLC patients (4 non-responders, 7 responders to anti-PD1 therapy). 8 healthy controls (CTRLs). | 33227982 |

| Greathouse et al. (2018) | Lung tumor tissue, non-tumor adjacent tissue, immediate autopsy (ImA) lung tissue, and hospital biopsy (HB) lung tissue. | Lung tissue-associated microbiome, TCGA lung cancer database, and Control lung tissues (Immediate autopsy, Hospital Biopsy). | Acidovorax, Brevundimonas, Comamonas, Tepidimonas, Rhodoferax, Klebsiella, Leptothrix, Polaromon as, Anaerococcus were differentially abundant in SCC vs AD (Student’s t-test; MW P < 0.05) Acidovorax, Klebsiella, Rhodoferax, Comamonas, and Polarmonas) that differentiated SCC from AD were also more abundant in the tumors harboring TP53 mutations Acidovorax, Ruminococcus, Oscillospira, Duganella, Ensifer, Rhizobium were distinguishable in smokers (current or former) vs non-smokers ever (Kruskal–Wallis p value < 0.05). | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), specifically squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma (AD); stages I–IV. | Detection | significant differences in beta diversity between all tissue types (PERMANOVA F = 2.90, p = 0.001), tumor and non-tumor (PERMANOVA F = 2.94, p = 0.001), and adenocarcinoma (AD) versus squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (PERMANOVA F = 2.27, p = 0.005), between tumor and non-tumor (PERMANOVA F = 3.63, p = 0.001) and AD v SCC (PERMANOVA F = 27.19, p = 0.001). | 16S rRNA gene sequencing (Illumina MiSeq). RNA-seq (TCGA data validation). Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) for Acidovorax detection. PacBio sequencing for full-length 16S rDNA. | NCI-MD study: 143 tumor cases, 144 non-tumor adjacent tissues, 33 ImA controls, 16 HB controls. TCGA validation: 1,112 tumor and non-tumor RNA-seq samples. | 30143034 |

| Zheng et al. (2020) | Fecal samples | Gut microbiota | Enriched in cancer: Proteobacteria, Ruminococcus, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Reduced in cancer: Faecalibacterium, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus infantis. 13 OTU-based biomarkers were chosen for cancer detection (AUC=97.6%) | Early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), including adenocarcinoma (ADC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and large cell carcinoma (LCC). Stages 0, I, and II. | Detection | AUC = 97.6% in dicovery (SVM prediction), 76.4% in validation | 16S rRNA sequencing. Support-Vector Machine (SVM) for prediction. PICRUSt for metabolic pathway analysis. | Discovery cohort: 42 patients, 65 controls. Validation cohort: 34 patients, 40 controls. | 32240032 |

| Dohlman et al. (2023) | Tumor tissues, normal tissues, and blood samples | Fungal DNA (mycobiome) from tumor and matched normal tissues | Candida species (e.g., C. albicans, C. tropicalis) in GI cancers. Blastomyces in lung cancer. Malassezia in breast cancer. | GI cancers: Head-neck (HNSC), esophagus (ESCA), stomach (STAD), colon (COAD), rectum (READ). Non-GI cancers: Lung (LUSC), breast (BRCA), brain (LGG). | Detection | Candida (p=0.00423) significantly and uniquely enriched in stomach tumor samples, Blastomyces (p = 0.0088) similarly enriched in lung tumors, and e Cyberlindnera was significantly enriched in normal tissue (p = 0.0000215). | ITS sequencing and culture validation. Random forest classifiers for biomarker identification. | 883 sequencing runs from 767 tumor samples (671 patients). Independent validation cohorts (e.g., 3 CRC samples for ITS sequencing). | 36179671 |

| Leng et al. (2021) | Lung tumor tissues Noncancerous lung tissues (paired with tumors) Sputum samples | Lower respiratory tract | SCC-associated: Acidovorax, Veillonella, Streptococcus AC-associated: Capnocytophaga Others: Helicobacter, Haemophilus, Fusobacterium | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | detection | Acidovorax and Veillonella were further developed as a panel of sputum biomarkers that could diagnose lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) with 80% sensitivity and 89% specificity. The use of Capnocytophaga as a sputum biomarker identified lung adenocarcinoma (AC) with 72% sensitivity and 85% specificity. The use of Acidovorax as a sputum biomarker had 63% sensitivity and 96% specificity for distinguishing between SCC and AC, the two major types of NSCLC | Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for bacterial DNA quantification. Logistic regression for biomarker panel selection. ROC curve analysis for diagnostic accuracy. | Cohort 1: 17 NSCLC patients + 10 cancer-free smokers. Cohort 2 (validation): 69 NSCLC patients + 79 cancer-free smokers. | 33673596 |

| Chen et al. (2022) | Plasma samples | Microbial-derived cell-free RNAs (cfRNAs) from human plasma | Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Torque teno viruses (TTVs), Orthohepadnavirus (e.g., HBV), Mycoplasma, Acholeplasma. | Colorectal, stomach, liver, lung, and esophageal cancers; mostly early-stage | Detection | The average AUROC scores of human cfRNAs on testing sets across 100 bootstrap replicates were approximately 0.9, and microbial cfRNAs quantified by k-mer-based pipeline achieved AUROCs from approximately 0.8 to above 0.9 | SMART-seq-based RNA sequencing, computational pipelines (k-mer and alignment-based), machine learning (random forest). | 300 plasma samples | 35816095 |

| al. (2020) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) | Lung microbiota from BALF | TMT, Capnocytophaga, Sediminibacterium, Gemmiger, Blautia, Oscillospira | Lung cancer; stages I–IV, limited stage, extensive stage | Detection | AUC =84.52% (95% CI: 74.06–94.97%) (the microbiome with clinical tumor markers). To distinguish LC vs benign pulmonary disease, AUC were 79.12% and 78.27%, using ten genera and clinical diagnostic markers. | 16S rRNA sequencing, bioinformatics (QIIME 2, PICRUSt), random forest modeling. | 54 patients (32 lung cancer, 22 benign pulmonary diseases) | 32676331 |

| Qin et al. (2022) | Stool | Gut microbiome |

Decreased in IA and MIA: Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, Roseburia, Subdoligranulum, Anaerotruncus. In MIA: Firmicutes. In AAH/AIS: Acidobacteria. Increased in AAH/AIS: Lachnoclostridium, Parasutterella. In IA: Prevotella, Klebsiella, Eubacterium eligens. In MIA: Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria. |

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) subtypes: Atypical Adenomatous Hyperplasia/Adenocarcinoma in situ (AAH/AIS), Minimally Invasive Adenocarcinoma (MIA), and Invasive Adenocarcinoma (IA). | Detection | The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in the HP group was 1.88, while in the lung cancer group, the ratio was 1.12 (AAH/AIS), 0.48 (MIA), and 0.95 (IA), respectively. | 16S rRNA gene sequencing, alpha/beta diversity analysis, LEfSe, KEGG, and COG pathway analysis. | 89 participants (28 healthy, 61 lung cancer patients) | 35774470 |

| Peters et al. (2022) | Tumor and distant normal lung tissue samples, peripheral blood buffy coat | Lung microbiome | Worse RFS: Clostridia, Clostridiales, Bacteroidia, Bacteroidales. Better RFS: Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Burkholderiales, Neisseriales. Worse DFS: Actinomycetales and Pseudomonadales | Stage II non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Detection | Area under the time-dependent ROC curve for microbiome model was >0.8 on average for 12 to 96 months. For microbiome and gene model, slightly more higher AUC. | 16S rRNA sequencing, nanoString® gene expression analysis, Cox regression, time-dependent ROC curves | 46 stage II NSCLC patients (39 tumor samples, 41 normal lung samples) | 36303210 |

| Ni et al. (2023) | Stool and serum samples | Gut microbiota | Enriched in NSCLC: Agathobacter, Blautia, Clostridium, Cetobacterium Reduced in NSCLC: Prevotella, Lachnospira, Catenibacterium, Desulfobacterota, Oxalobacter | Early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Detection | Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe), LAD score ≥ 3 | 16S rRNA gene sequencing (microbiome). LC-MS/MS metabolomics (serum). LEfSe, PLS-DA, and Spearman correlation analysis. | 78 stool samples (43 early-stage NSCLC patients, 35 healthy controls), 63 serum samples (35 NSCLC and 28 healthy) | 36743312 |

| Chen et al. (2023) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) | Lung microbiome |

Prevotella, Klebsiella, Mycobacterium, Gordonia, Sphingobium, Achromobacter, Pedobacter, Xanthomonas. five genera were considered as potential markers for identification of lung cancer, including Klebsiella, Mycobacterium, Pedobacter, Prevotella, and Xanthomonas with threshold value of MDA>5 or MDG>2 0.837 |

Lung cancer | Detection | (p<0.05, LDA>3), The diagnostic performances of all genus classifier (receiver operating curve [AUC = 0.847]), five genus classifier (AUC = 0.898), five genus classifier + CEA (AUC = 0.837), five genus classifier+CYF21-1 (AUC = 0.898), and five genus classifier+NSE+CYF21-1 (AUC = 0.878) were similar. However, compared with the above classifiers, five genus classifier+NSE (AUC = 0.959) displayed superior diagnostic performances with 85.7% of specificity, 100% of sensitivity, and cut-off value of 0.386. | Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS), LEfSe, Metastat, Random Forest analysis, ROC curve evaluation. | 90 BALF samples (30 Negative Control samples, 31 benign samples, and 29 malignant samples) | 36480163 |

| Liu et al. (2022) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and lung tissue flushing solutions. | Lung microbiota from BALF samples |

3 metabolites and 9 species with significantly differences, might be potential diagnostic markers associated with LC Streptococcus, Prevotella, Veillonella, Haemophilus, Fusobacterium, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Oscillospirales, Christensenellaceae. |

Lung cancer (non-small cell lung cancer, NSCLC) | Detection | ROC based on the combination of three metabolites (AUC > 0.91). ROC for the combination of 9 species screened by LASSO (AUC>0.88) | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, metagenomics, metabolomics (LC-MS/MS), ROC analysis, LEfSe, LASSO. | 43 patients (30 lung cancer, 13 non-lung cancer controls) | 36457513 |

| Zheng et al. (2021) | Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid by bronchoscopy and lobectomy | Lung microbiota | Streptococcus, Enterobacter, Mycobacterium, Lactobacillus rossiae, Bacteroides pyogenes, Paenibacillus odorifer, Pseudomonas entomophila, Chaetomium globosum. | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); stages I–IV included | Detection | Distance based RDA revealed a higher correlation between microbial community composition (response variables) and explanatory variable sampling method (R2=0.061, p=0.003). This suggests the need of standardized sampling methods. | Shotgun metagenomic sequencing, NMDS, PCoA, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. | 47 samples (15 non-cancer controls, and 32 NSCLC patients) (25 were form Bronchoscopy, 22 from lobectomy) | 34083661 |

| Zhao et al. (2021) | Stool samples | Gut microbiome | Enriched in responders: Streptococcus mutans, Enterococcus casseliflavus, Acidobacteria and Granulicella. Enriched in nonresponders: Leuconostoc lactis, Eubacterium siraeum, Streptococcus oligofermentans, Megasphaera micronuciformis, and Eubacterium siraeum | Locally advanced and advanced lung cancer (NSCLC and SCLC) | Treatment | p values < 0.05 | Metagenomic sequencing, statistical analysis (Wilcoxon rank-sum, Spearman correlation), unsupervised clustering. | 64 patients (33 responders, 31 nonresponders) | 33111503 |

| Kim et al. (2024) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) | Lung microbiome |

Enriched in lung cancer: SAR202 clade (Chloroflexi), Firmicutes, Streptococcus. Enriched in benign diseases: Bacteroidota, Prevotella_7. |

Lung cancer stages III and IV | Detection | benign lung disease vs LC (micro AUC=0.98, macro AUC=0.99). pneumonia vs lung cancer (micro AUC=0.94, macro AUC=0.98). | 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomic analysis, random forest prediction model | 48 patients (24 lung cancer, 24 benign lung diseases) | 38242941 |

| Hakozaki et al. (2020) | Fecal samples | Gut microbiome | Enriched in longer survival cohort and not having ATB: Ruminococcaceae UCG 13, Agathobacter, Lachnospiraceae UCG 001. Enriched in cohort received ATB: Hungatella. Enriched in cohort with non-severe irAE: Lactobacillaceae and Raoultella Enriched in severe irAE: Agathobacter | Advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), stages III and IV, treatment with or without ATB | Treatments | p values < 0.05 | 16S rRNA sequencing, alpha/beta diversity analysis, LEfSe, DESeq2, random forest model. | 70 patients (16 with prior antibiotics, 54 without) | 32847937 |

| Otoshi et al. (2022) | Fecal samples and blood samples | Gut microbiome |

positive/negative correlation to tumour: Faecalibacterium, Fusicatenibacter, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium. Lower abundance in EGFR mutation-negative patients: Blautia. |

Lung adenocarcinoma in female never-smokers; analyzed by TNM stage, T category, and tumor size. | Detection | R>= 0.5, and P <0.05 means positive significant correlation. R< 0.5, and P <0.05 means negative significant correlation |

16S rRNA gene sequencing, PCoA, Bray-Curtis distance, correlation analysis | 37 patients | 35220256 |

| Liu et al. (2023) | Blood samples (plasma) for cfRNA analysis | Microbial-derived cfRNAs from plasma (bacteria and viruses) | difference in proportion, Bacterial genera (e.g., Klebsiella Cutibacterium, Priestia and Halomonas.) and viral genera (e.g., Gorganvirus, Orthobunyavirus, Orthohantavirus and Betabaculovirus) | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), primarily early-stage | Detection | For VIP cutoff >1.8, In cross-validation test, AUC of RF= 0.907, AUC of LR= 0.885 In independent test, AUC of RF=0.703, AUC of LR=0.938 | cfRNA-Seq, machine learning (random forest, logistic regression), immune repertoire analysis (TRUST4), microbiome profiling (Kraken2) | TP cohort: 35 NSCLC, 46 normal. SU cohort: 6 NSCLC, 6 normal. Inhouse cohort: 10 normal. Total: 41 NSCLC, 62 normal samples. | 37692082 |

| Zhou et al. (2023) | Blood samples | Circulating microbial DNA (cmDNA) from peripheral blood. | 14 OS-related microbes, as prognostic risk factors (e.g., Candidatus_Babela, Methanotorris, Anaeromusa, etc.) and as prognosis favorable factors (e.g., Kozakia, Andromedalikevirus, Desulfuromonas, etc.). | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), all stages. | treatment outcome | ROC based on MAPS, OS AUC, 1 year=0.890, 3 years=0.920, 5 years=0.878 ROC based on nomogram without MAPS, OS AUC, 1 year=0.887, 3 years=0.745, 5 years=0.791 ROC based on nomogram with MAPS, OS AUC, 1 year=0.964, 3 years=0.850, 5 years=0.818 | Cox regression, Kaplan-Meier, GSEA, immune infiltration analysis, drug sensitivity prediction (TIDE, oncoPredict). | 109 NSCLC patients from TCGA | 37950236 |

| Chen et al. (2022) | Stool and serum samples | Gut microbiome | The key species were Roseburia (LDA score 4.22, p = 0.012), Lachnospira (LDA score 4.21, p = 0.001),Anaerostipes(LDA score 3.83, p = 0.007), and Lachnoclostridium (LDA score 3.60, p = 0.042)inHC; Lactobacillusin ESLC (LDA score 3.89, p= 0.029); and Escherichia_Shigella in NESLC (LDA score 4.53, p = 0.010). | Lung cancer | Detection | LDA>3.5, p<0.05 | 16S rRNA sequencing, LC/MS Non-Targeted Metabolomics | 30 lung cancer patients and 15 healthy individuals | 35586253 |

| Sun et al. (2023) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and saliva (oral) samples | Lung and oral microbiomes from lung cancer patients. |

Predominant phyla: Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria. Genera: Streptococcus, Veillonella, Prevotella, Pseudomonas. Species: Prevotella oralis, Gemella sanguinis, Streptococcus intermedius. |

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC: adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma) and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). | Detection | The study collected three samples from the same cancer patients, cancerous (C) and healthy (H) sites of the lung, and the oral (O) cavity. No significant difference of diversity between C and H. Shannon index (P = 0.527) and Chao1 index (P = 0.428), e Bray-Curtis distances (P = 0.39). | Culturomics (bacterial culture) and 16S rRNA gene sequencing | 25 patients with unilateral lobar masses (23 with lung cancer, 2 non-cancer controls) | 37092999 |

| Haberman et al. (2023) | Stool | Gut microbiome | Decreased in lung cancer: Clostridiales, Lachnospiraceae, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Increased in lung cancer: Ruminococcus torques. Predictive of durable clinical benefit (DCB): Akkermansia muciniphila, Alistipes onderdonkii, Ruminococcus. | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma) and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC); stages IIB–IV | Detection | AUC = 0.74 | 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, Random Forest modeling, PERMANOVA, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. | 75 lung cancer patients and 31 healthy controls. | 36737654 |

| Jin et al. (2019) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) | Lower respiratory tract (LRT) microbiome | Decreased in lung cancer: Prevotella, Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria. Unique to lung cancer: Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Enriched in lung disease: Acidovorax spp. 11 biomarker bacteria: Prevotella melaninogenica, Streptococcus sp. I-P16, Corynebacterium urealyticum, Acidovorax sp. KKS102, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus sanguinis, H. influenzae, Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae, Bacteroides salanitronis, Campylobacter concisus, and B. japonicum | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma), small cell lung cancer (SCLC); stages I–IV. | Detection | AUC = 0.882 in training set, 0.796 in independent validation set | Metagenomics sequencing, Random Forest modeling, PCoA, PERMANOVA | Discovery set: 150 (91 lung cancer, 29 nonmalignant, 30 healthy). Validation set: 85. | 31494531 |

| Yang et al. (2018) | Saliva samples from non-smoking female lung cancer patients and healthy controls. | Salivary microbiome | Higher in cancer patients: Sphingomonas, Blastomonas. Higher in controls: Acinetobacter, Streptococcus. | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Detection | (ANOSIM, r = 0.454, P < 0.001, unweighted UniFrac; r = 0.113, P < 0.01, weighted UniFrac). | 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Statistical analyses (LEfSe, PCoA, Spearman’s correlation). PICRUSt for functional prediction. | 247 participants (75 non-smoking lung cancer female patients, 172 healthy controls). | 30524957 |

| Roy et al. (2022) | Saliva samples from lung adenocarcinoma (LAC) patients and healthy controls | Salivary microbiome | Elevated in LAC: Rothia mucilaginosa, Veillonella dispar, Prevotella melaninogenica, Prevotella pallens, Prevotella copri, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Neisseria bacilliformis, Aggregatibacter segnis. | Lung adenocarcinoma (LAC), stages included IV and T3N0M0/T4N2M1 | Detection | Pilot Study: did not provide any diagnostic/prognostic value | 16S rRNA gene sequencing (V3-V4 region). Illumina MiSeq platform. QIIME for analysis, PICRUSt for functional prediction | 10 participants (5 LAC patients, 5 healthy controls) | 35074976 |

| Lee et al. (2016) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) | Lower respiratory tract microbiota | Phyla increased in LC: Firmicutes, TM7. Genera increased in LC: Veillonella, Megasphaera (potential biomarkers). | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Stages included I–IV (advanced stages predominant). | Detection | AUC =0.888, p=0.002 | 16S rRNA sequencing (V1–V3 regions), Illumina HiSeq 2500. Statistical analysis (ROC curves, UniFrac, PCoA). | 28 participants (20 lung cancer, 8 benign lesions) | 27987594 |

| Wang et al. (2022) | Stool and blood samples | Gut microbiome | Bacteroides, Pseudomonas, Ruminococcus gnavus group | Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), stages I-IV | Detection | AUC= 0.852 (for 16S-rRNA sequencing) and 0.841 (for metagenomics) | 16s-rRNA sequencing, metagenomics, metabolomics, logistic regression. | 100 participants (60 LUAD patients, 40 healthy controls) | 35592677 |

| Sarkar et al. (2023) | Fecal (stool) samples and peripheral blood samples | Gut microbiome |

Responders: Decreased: Odoribacter, Gordonibacter, Candidatus Stoquefichus, Escherichia-Shigella, Collinsella; increased: Clostridium sensu stricto 1. Non-responders: Increased: Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Streptococcus, Escherichia-Shigella; decreased: Akkerm |

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), stages IIIA–IV | Detection | P<0.05 | 16S rRNA sequencing, flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry ders, 1 male, 4 female) | 5 patients (3 responders, 2 non-respon | 37350807 |

| Luan et al. (2024) | Fecal samples | Gut microbiome | Subdoligranulum, Romboutsia, Blautia, Bacteroides, Fusicatenibacter Biomakers: 2 bacteria (Subdoligranulum, and Romboutsia), 4 metabolites (Stearoylethanolamide, Serylthreonine, Xestoaminol C and Farnesyl acetone) | Lung cancer stages I–IV | Detection | AUC = 0.9 | 16S rRNA gene sequencing, LC-MS metabolomics, PLS-DA, ROC analysis | 55 LC patients and 28 benign pulmonary nodules patients | 38166904 |

| Seixas et al. (2021) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) | Lung microbiome | Streptococcus, Prevotella are associated with LC, Haemophilus with COPD, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus with ILD. | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), adenocarcinoma (ADC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) | Detection | p<0.05 | 16S rRNA gene sequencing, bioinformatics analysis (DADA2, DESeq2), alpha/beta diversity metrics | 106 BALF samples (49 LC, 40 non-LC, 17 comorbidity-controlled: 8 LC*, 7 COPD, 10 ILD) | 34294826 |

| Lu et al. (2021) | Fecal and sputum samples | Gut and lung microbiota | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus, Streptococcus, Actinomyces, Faecalibacterium | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), stages I–IV | Detection | AUC = 0.896 | 16S rRNA sequencing, machine learning (random forest), LEfSe analysis, PICRUSt2 for functional prediction | 121 participants (87 NSCLC patients, 34 healthy controls) | 34787462 |

| Kwok et al. (2023) | Malignant pleural effusions (MPE), Pleural fluid, background sample s (sterile surgical equipment swabs, reagent controls), skin swabs | Pleural fluid microbiota from malignant and non-malignant effusions. | MPE-lung and mesothelioma: increase of Rickettsiella, Ruminococcus, Enterococcus and Lactobacillales MPE-other: increase of Methylobacterium Benign: increase of Prevotella and Bacillus Paramalignant: increase of Deinococcus Mortality in MPE-lung: increase of Methylobacterium, Blattabacterium, and Deinococcus | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), mesothelioma, other metastatic cancers (e.g., gastrointestinal) | Detection | p<0.05, for mortality, MPE-lung (AUC range: 0.59 to 0.66) MPE-other (AUC range: 0.66 to 0.94) Mesothelioma (AUC range: 0.5 to 0.81) | 16S rRNA sequencing, ddPCR, LEfSe, random forest classifiers, DMM modeling | 165 subjects (pleural fluid samples), plus 58 background and 21 skin samples | 36755121 |

| Dora et al. (2023) | Stool samples | Gut microbiota from advanced-stage NSCLC patients treated with anti-PD1 immunotherapy | Alistipes shahii, Alistipes finegoldii, Barnesiella viscericola (associated with long progession free survival, PFS); Streptococcus salivarius, Streptococcus vestibularis, Bifidobacterium breve (associated with short PFS) | Advanced-stage NSCLC (stage IIIB/IV), including adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and NSCLC-NOS | Detection | taxonomic profile is best suited for PFS (AUC=0.74), pathway profile predicts better the PD-L1 phenotype of patients (AUC=0.87) | Shotgun metagenomic sequencing, Lasso/Cox regression, Random Forest machine learning, PERMANOVA, UMAP visualization. | Discovery cohort (n=62), Validation cohort (n=60) | 37197440 |

| Gomes et al. (2019) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), tumor tissue RNAseq reads | Lung microbiota | Proteobacteria (dominant), Enterobacteriaceae (linked to worse SCC survival) Associated with ADC: Acinetobacter, Propionibacterium, Phenylobacterium, Brevundimonas and Staphylococcus Associated with SCC: Enterobacter, Serratia, Kluyvera, Morganella, Achromobacter, Capnocytophaga and Klebsiella | NSCLC subtypes—adenocarcinoma (ADC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) | Detection | p<0.05 | 16S rRNA sequencing (pooled), RNAseq unmapped read analysis, LEfSe, PCoA, survival analysis | 103 BALF samples (49 LC, 54 controls) + 1009 TCGA cases (509 ADC, 500 SCC) | 31492894 |

| Zhou et al. (2023) | Saliva, cancerous tissue (CT), paracancerous tissue (PT) | Oral (saliva) and lung (CT, PT) | Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes (dominant phyla); Promicromonosporacea, Chloroflexi (enriched in CT); Enterococcaceae, Enterococcus (enriched in PT) | Lung adenocarcinoma (stages I–III) | Detection | AUC = 0.74 | 16S rRNA sequencing, QIIME, PICRUSt, LEfSe, ROC analysis | 43 patients | 37641037 |

| Takada et al. (2022) | Clinical data from NSCLC patients (no physical samples like tissue or saliva) | Gut microbiome | Probiotics analyzed: Clostridium butyricum, Bifidobacterium, antibiotic-resistant lactic acid bacteria | Advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), all stages (treatment lines varied) | Treatment | C-index 0.57–0.62, p<0.05 | Retrospective analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival, Cox regression, drug score validation. | 293 patients | 35780526 |

| Han et al. (2019) | Metagenomic sequencing data | Gut microbiome | Akkermansia muciniphila, Eggerthella lenta, Bifidobacterium | Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) | Detection | AUCs: 0.83–0.96 for liver cirrhosis; 0.81–0.91 for NSCLC/RCC immunotherapy response | Subtractive assembly (CoSA), machine learning (SVM, Random Forest), read mapping (Bowtie 2) | microbiome datasets: 93 (T2D), 181 (cirrhosis), 65 (NSCLC), 62 (RCC) | 30864326 |

| Liu et al. (2023) | fecal sample | gut mycobiome | Increased in LUAD: Basidiomycota, Saccharomyces, Aspergillus, and Apiotrichum Decreased: Ascomycota, Candida | Early stage lung adenocarcinoma | Detection | AUC: 0.935, AUC of validation cohorts: 0.9538 (Beijing), 0.9628 (Suzhou), and 0.8833 (Hainan) | ITS2 sequencing, OTU clustering, Feature selection (Boruta algorithm), Supervised ML (Random Forest, SVM, NB, LR, KNN), Diversity analysis | 299 participants, (181 LUAD and 118 HCs). Validation cohort, Internal (Beijing, n=44 LUAD, 26 HC) and external (Suzhou, n=17 LUAD, 19 HC, and Hainan, n=15 LUAD, 12 HC), and discovery cohort (Beijing, n=105 LUAD, 61 HC). | 37904139 |

| Zhang et al. (2021) | Stool samples (gut microbiota) and paired sputum samples (respiratory microbiota) | Gut and respiratory microbiota from metastatic NSCLC patients treated with anti-PD1 immunotherapy | Enriched in responders: Desulfovibrio, Actinomycetales, Bifidobacterium, | Metastatic NSCLC (stage IV) | Treatment | individual AUC (p<0.05) for gut microbiome range: 0.67-0.78 for respiratory microbiome: 0.67-0.77 | 16S rRNA sequencing, LEfSe, PCoA, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, Spearman correlation | 75 patients (25 responders, 50 non-responders), 75 stool and 57 sputum samples | 34028936 |

| Song et al. (2020) | Stool samples | Gut | Parabacteroides, Methanobrevibacter (PFS ≥6 months); Veillonella, Selenomonadales, Negativicutes (PFS <6 months) | Advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), stages IIIB–IV | treatment | p<0.05 | Metagenomic shotgun sequencing (Illumina HiSeq), bioinformatics analysis (α/β-diversity, LEfSe, KEGG pathways). | 63 patients | 32329229 |

| Jiang et al. (2024) | Fecal samples | Gut microbiota | Faecalibacterium, Bifidobacterium, Butyricicoccus, Klebsiella, Streptococcus, Blautia, Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), early stage (I–III) and brain metastasis (stage IV) | Detection | AUC=0.884 | 16S rRNA sequencing, gas chromatography for SCFAs, bioinformatics analysis (LEfSe, PICRUSt) | 115 participants (35 healthy, 40 early-stage NSCLC, 40 brain metastasis) | 38304459 |

| Derosa et al. (2024) | Fecal samples | Gut microbiota | SIG1 (37 species, e.g., Enterocloster, Streptococcaceae). SIG2 (45 species, e.g., Lachnospiraceae, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii) Finally 21 species were used in the qPCR-TOPOSCORE including A. muciniphilia, Blautia wexlerae, F. prausnitzii | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Urothelial cancer (UC). Melanoma and colorectal cancer (validation) | treatment | AUC=0.6 in NSCLC cohort (discovery+validation, n=499) | Shotgun metagenomics. qPCR-based assay. Co-abundance network analysis. | 920 cancer patients (NSCLC, RCC, UC) + healthy volunteers | 38906102 |

| Otálora-Otálora et al. (2024) | Transcriptomic datasets from lung, colon, and gastric cancer tissues and normal tissues. | Oral-gut-lung axis microbiota, including viruses (HTLV-1, HPV, EBV, SARS-CoV-2) and bacteria (e.g., Helicobacter pylori) | HTLV-1, HPV, EBV, SARS-CoV-2, Helicobacter pylori, Entamoeba histolytica, Salmonella enterica | Lung cancer (NSCLC, SCLC), colon cancer, gastric cancer (intestinal/diffuse types) | Detection/treatment | No diagnostic or prognostic values were reported | Bioinformatic pipeline using R libraries (Limma, DESeq2), DAVID, RTN, CoRegNet, and gene network analysis | 25 datasets (10 lung, 10 gastric, 5 colon cancer datasets) | 39228892 |

| Zeng et al. (2024) | GWAS summary data, plasma metabolites, gut microbiota data. | gut microbiota and plasma metabolome | Bacteroidia, Bifidobacteriaceae, Streptococcus, Slackia, RuminococcaceaeUCG005 causal effect on LC ( 13 taxa and 15 plasma metabolites), LUAD (8 taxa and 14 metabolites), SCC (4 taxa and 10 metabolites), SCLC (7 taxa and 16 metabolites) | Lung cancer subtypes: LUAD, SCC, SCLC | detection | p<0.05, Odd ratios | Mendelian Randomization (IVW, Wald ratio), sensitivity tests, enrichment/mediation analysis | 18,000 individuals (GM), 7,824 europeans (metabolites), LC meta-analysis | 38793035 |

| Wang et al. (2024) | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) | Lower respiratory tract microbiome | LC: Lactobacillus acidophilus, Streptococcus mitis Lung infection group: Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Corynebacterium, Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Veillonella, Neisseria, Acinetobacter, and Klebsiella others group: Actinomyces, Prevotella, Fusobacterium, Leptotrichia, Corynebacterium, and Rothia | Lung adenocarcinoma (n=16), squamous cell carcinoma (n=4), small cell carcinoma (n=1); stages I–IV | Detection | AUC=0.985, accuracy = 98.46%, sensitivity= 95.24%, and specificity = 100.00%; P< 0.001) | Metagenomic NGS, qPCR, multivariate logistic regression | 158 patients with diffuse lung parenchymal lesions. | 39185086 |

| Feng et al. (2024) | Human feces | Gut microbiota | Akkermansia muciniphila, Lachnospiraceae bacterium NSJ-38, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Acutalibacter timonensis, and Lachnospiraceae bacterium COE1 | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), stages IIIB and IV (human); murine Lewis lung carcinoma model | Detection | p<0.05 | Shotgun metagenomics, flow cytometry, statistical analysis (R packages) | 9 healthy humans, 12 NSCLC patients, 24 mice (12 LCM, 12 HCM) | 38612577 |

| Ren et al. (2024) | Saliva samples from pulmonary nodule (PN) patients and healthy controls (HCs) | Oral microbiota | Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus, Haemophilus | Pulmonary nodules (PNs), early-stage precursors for lung cancer (no specific cancer stage) | Detection | AUC=0.80, p<0.05 | 16S rRNA sequencing, random forest model, KEGG/COG analysis, Wilcoxon/LEfSe tests | 173 PN patients + 40 HCs = 213 total | 38643115 |

| Chen et al. (2025) | Fecal samples | Gut microbiota | 4 genera used for the model: Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Prevotella, Flavonifractor | Lung Adenocarcinoma | Detection | LUAD with QP Syndrome, AUC=0.989 (16S-rRNA), 1.00 (metagenomics) | 16s-rRNA sequencing, LEfSe, logistic regression, metagenomics | 110 participants (30 healthy, 80 LUAD) | 38847243 |

| Tesolato et al. (2024) | Fecal samples | Gut microbiota | CRC: Parvimonas, Gemella, Eisenbergiella, Peptostreptococcus, Lactobacillus, Salmonella, Fusobacterium. NSCLC: DTU089, Ruminococcaceae Incertae Sedis | Colorectal Cancer (CRC) and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC); stages I–IV | Detection | AUC=0.840 (CRC), AUC=0.747 (NSCLC) | 16S rRNA sequencing, QIIME2, LEfSe, logistic regression, ROC analysis | 77 participants (38 CRC, 19 NSCLC, 20 controls) | 38540316 |

| Zeng et al. (2024) | Saliva samples | Salivary microbiota | Top 6 species: Fusobacterium, Solobacterium, Actinomyces, Porphyromonas, Atopobium, Peptostreptococcus | Persistent pulmonary nodules | Detection | AUC=0.877 (all microbial species), 0.872 (Top 6 microbial species) | 16S rRNA sequencing, machine learning (LightGBM), PICRUSt2 | 483 participants (141 healthy, 342 pPN) | 39609902 |

| Mao et al. (2025) | Cancerous and adjacent normal tissues | Intratumoral microbiota from NSCLC and normal lung tissues | 11 HAM genera in tumour (Anaerovorax, Marivivens, Donghicola, Lachnospira, Dubosiella, Lactobacillus, Methylobacterium, Akkermansia, Paenibacillus, Aerococcus and Cloacibacterium) and 1 HAM genera in normal tissue (Campylobacter) Peptococcus; protective (9 genera) and harmful (3 genera) microbial clusters For survival (OS and PFS) prognostic model: Xanthobacter, Pantoea, Oscillospira, Hydrogenispora, Peptococcus and Glycomyces | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), subtypes LUAD and LUSC, stages II–IV | Detection/treatment | AUC=0.862 (NSCLC diagnostic model, 5 genera), p<0.05 AUC= 0.9916 (1 yr), 1.0000 (3 yrs) and 0.9649 (5 yrs) (Survival prognostic model), p<0.05 | 16S rRNA sequencing, transcriptome sequencing, Cox regression, LASSO, Mendelian randomization | 30 NSCLC patients | 39754314 |

| Su et al. (2024) |

Tumor tissues from LUAD patients | Intratumoral microbiota from LUAD tumor tissues (TCGA RNA-seq data) | Pseudoalteromonas, Luteibacter, Caldicellulosiruptor, Loktanella, Serratia | Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD); stages I (early) vs. II–IV (advanced) | Detection | AUC = 0.70 | RNA-seq, DESeq2, random forest, co-abundance networks, GO enrichment | 491 patients (267 early, 224 advanced) | 38721596 |

| Dora et al. (2024) | Fecal samples | Gut microbiome | Actinomycetota, Euryarchaeota, Bacillota, Bifidobacterium, Collinsella | Advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; stage IIIB/IV) | treatment | AUC= 0.878 and Accuracy= 78.1% (RF model, long vs short PFS) AUC= 0.85 and accuracy= 75.6% (SVM model) AUC= 0.84 and Accuracy= 75% (GBDT, XGBoost model) combined risk score (AUC=0.89) | Metatranscriptomics, de novo assembly (Trinity), DESeq2, machine learning (RF, SVM, XGBoost) | 29 NSCLC patients undergoing ICI therapy | 39563352 |

| Yang et al. (2025) | Tumor tissues (from TCGA and GEO datasets) | Lung microbiome | 18 genera including Azotobacter, Buchnera, Corynebacterium, Delftia, Mycoplasma, etc. | Lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) | detection | AUC= 0.690 (1 yr), 0.736 (3 yrs) and 0.771 (5 yrs) (Survival prognostic model), p<0.05 AUC= 0.549 (1 yr), 0.63 (3 yrs) and 0.67 (5 yrs) (mRNA prognostic signatures) | LASSO, Cox regression, XGBoost, RNA-Seq, external validation | 470 patients (TCGA training cohort) | 39915534 |

| Vicente-Valor et al. (2025) | Tumor and non-tumor tissues, fecal samples | Colorectal tissues (CRC), lung tissues (NSCLC), feces | Fusobacterium (CRC); Cryobacterium, Tepidicella, Geodermatophilus, Nakamurella (NSCLC) | Colorectal Cancer (CRC) and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC); stages I-IV | Detection | p<0.05, although results did not show much significant results for NSCLC | 16S rDNA metagenomic sequencing, QIIME2, STATA IC16, LEfSe, PICRUSt2 | 38 CRC, 19 NSCLC patients | 39859429 |

| Qian et al. (2022) | Fecal samples, serum samples, NSCLC tumor tissues, adjacent non-cancerous tissues, mouse tissues, blood samples | Gut microbiota | Prevotella, Gemmiger, Roseburia (upregulated); Prevotella copri (used as intervention) | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC); early-stage and tumor tissues (stages unspecified) | Detection/treatment | p<0.05 | 16S rRNA sequencing, LC-MS metabolomics/proteomics, FMT in mice, bioinformatics (PICRUSt, LEfSe) | 55 NSCLC patients, 15 healthy controls (human); 40 NSCLC tissue pairs; mice groups (n=5-6) | 35735103 |

| Lu et al. (2023) | Stool samples | Gut microbiome | Abundance in HC: Firmicutes, Clostridia, Bacteroidaceae, Bacteroides, Lachnospira LC: Ruminococcus gnavus SCC: Proteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Enterobacteriaceae ADC: Fusicatenibacter, Roseburia | Lung cancer (non-small cell carcinoma: adenocarcinoma [ADC] and squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]), stages I–IV | Detection | p<0.05 | 16S rRNA sequencing, GC/LC-MS metabolomics | 81 participants (52 LC, 29 HC) | 37577375 |

| Cameron et al. (2017) | Sputum samples | Respiratory tract (upper bronchial tract/lungs) | Granulicatella adiacens, Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus intermedius, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter junii, Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) subtypes: squamous cell, adenocarcinoma, large cell carcinoma; stages unspecified | Detection | R2 value, p<0.05 | Metagenomic sequencing, 16S rRNA qPCR, MG-RAST analysis | 10 participants (4 LC+, 6 LC−), pilot study | 28542458 |

| Yu et al. (2023) | Oral rinse samples and tumor/control laryngeal tissue samples | Oral microbiota (from rinse), laryngeal microbiota (from tissue) | Fusobacterium, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Flavobacterium, Mycoplasma in tumor tissues, Saccharopolyspora, Actinobacillus in oral rinse of LSCC patients, Ralstonia, Streptococcus, Rothia, Lactobacillus in tumor tissues | Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC), early to advanced stages (clinical detail available but not staged by AJCC) | Detection | AUC = 0.857 in test set (oral rinse), 0.864 training | 16S rRNA gene sequencing (V3–V4), Bioinformatics with QIIME, Wilcoxon test, PERMANOVA, PCoA, Random forest classifier, 10-fold cross-validation, ROC curve analysis | 153 totals (77 LSCC patients, 76 vocal polypcontrols) | 37408030 |

| Qiao et al. (2022) | Tumor biopsy samples | Intratumoral microbiota | Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, Prevotella, Porphyromonas (higher in relapsed tumors) | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) | Treatment | HR (DFS): 2.90 (training), 3.32 (internal), 2.24 (external) | 16S rRNA sequencing, qPCR for bacterial load quantification, FISH & IHC for validation, SNV-based strain origin tracing, Host transcriptomics (RNA-seq), Survival analysis (Kaplan-Meier, Cox models), Pathway enrichment (GSEA) | 802 total patients: - 241 (training, fresh frozen) - 233 (internal validation) - 232 (external validation) - 96 discovery (relapse/no relapse) - 20 additional patients (multi-omics profiling) | 35834269 |

| Zhong et al. (2022) | tissue samples | Intratissue microbiome (NPC tumor and chronic nasopharyngitis tissues) | Epulopiscium, Terrisporobacter, and Turicibacter | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) | Detection/ Treatment | AUC= 0.842 for differentiating NPC from chronic nasopharyngitis AUC= 0.956 for diagnosis of R from NR for NPC treatments | 16S rRNA gene sequencing, bioinformatics analysis (alpha/beta diversity, LEfSe), immunohistochemistry, and statistical modeling (ROC, Cox regression) | 64 participants (50 NPC patients and 14 controls) | 35677160 |

| Lu et al. (2024) | Nasopharyngeal and middle meatus swabs | Commensal microbiota (nasopharynx and middle meatus) | Pseudomonas, Cutibacterium, Finegoldia, Paracoccus | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) / Stages I–IV | Detection | AUC = 0.86 (NPC vs nNPC groups) | 16S rRNA sequencing, Machine learning (RFECV, XGBoost), PICRUSt2, DESeq2 | 25 participants (10 NPC, 15 non-NPC) | 39704233 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).