1. Cotton as a Dual-Purpose Crop

Cotton (

Gossypium hirsutum) has evolved as a dual-purpose crop because its seeds are not only economically valuable as a high-quality fiber crop, but also nutritionally valuable as a seed source of proteins. Cottonseed is a byproduct of lint production, accounting for approximately 60 percent of seed cotton, and is an excellent source of oil, protein, and energy [

1]. Cottonseed oil is one of the five most widely used vegetable oils in the world, with demand in both food and industrial markets [

2]. Due to its high protein content (~23%) and 16-24% oil content, cottonseed is also used as animal feed [

3]. This dual purpose strengthens the value chain of the crop, making cotton a significant part of the textile and oilseed industries. Nevertheless, seed quality and fiber are the primary focus of breeding programs. They have been, and continue to be, in positions where the seed traits have suffered from genetic deterioration [

4]. During the adoption of global agriculture towards resource efficiency and sustainability, dual-purpose crops like cotton have become a strategic choice to maximize hectare returns, provide farmers with alternative forms of income, and also address the existing and growing demand for plant-based oils and proteins [

5].

In recent years, cottonseed oil has gained popularity due to shifting global interests in sustainable farming, alternative sources of protein and oils, and resilient agricultural systems in response to climate fluctuations [

6]. As the world's population grows and viable land becomes scarce, one way to intensify agricultural production is to maximize the non-fiber value of fiber crops, such as cotton. Cottonseed oil is valued for its high levels of oxidation stability, balanced proportions of fatty acids (including palmitic, oleic, and linoleic acids), and suitability for use as food, industrial, and biofuel oil [

7]. Moreover, rising consumer demand for non-genetically modified organism and vegetable oils has established cottonseed oil as a viable alternative to soybean oil and palm oil, especially in regions with significant cotton cultivation [

8]. The integration of oil production into the process of growing cotton not only enhances the food security but also enhances the value of the crop, which can also raise the profit levels of both small landholders and commercial farmers. This renewed importance has sparked the need to know what genetic phenomena predispose the accumulation of oil within the plant, and how this duality within the home can be genetically optimized in the present breeding programs.

Despite its economic and agronomic potential, efforts to maximize the composition and content of cottonseed oil have faced significant challenges since the complex genetic makeup of the cotton genome presents a difficult challenge to overcome [

6,

9]. An important concern is that an inverse relationship has often been observed between seed oil content and the agronomic traits of cultivars, including lint yield and fiber quality. The primary reason for this trade-off is competition over assimilates available during boll development, whereby carbon and energy resources are primarily focused on fibre acquisition rather than oil synthesis in the seed [

10,

11]. Additionally, several quantitative trait loci (QTL) and transcriptional factors that stimulate oil biosynthesis, such as

GhWRI1 and

GhLEC1, have demonstrated pleiotropy, inadvertently influencing fiber traits or seed formation [

12]. Interweaving of genes and areas relating to oil with other agricultural characteristics makes it difficult to isolate the impact of their respective factors. Usual breeding approaches, which often use phenotypic selection based on lint traits, have inadvertently limited progress made on the genetic level in the traits of seed oils. Therefore, cotton breeding programs have shown little development in producing genotypes with high oil content and combining them with good agronomic characteristics, which has been the practical necessity of detailed breeding designs that will overcome these natural genetic trade-offs. Multi-trait genomic selection, CRISPR-based uncoupling of antagonistic loci, and the use of wild and exotic germplasm are some of the available solutions to the problem of linkage drag. This paper presents an integrative evaluation of the boundaries and opportunities in oil–agronomic trait modification and outlines a conceptual breeding framework for developing dual-purpose cotton ideotypes that enhance both fiber yield and oil content while maintaining sustainability and climate resilience.

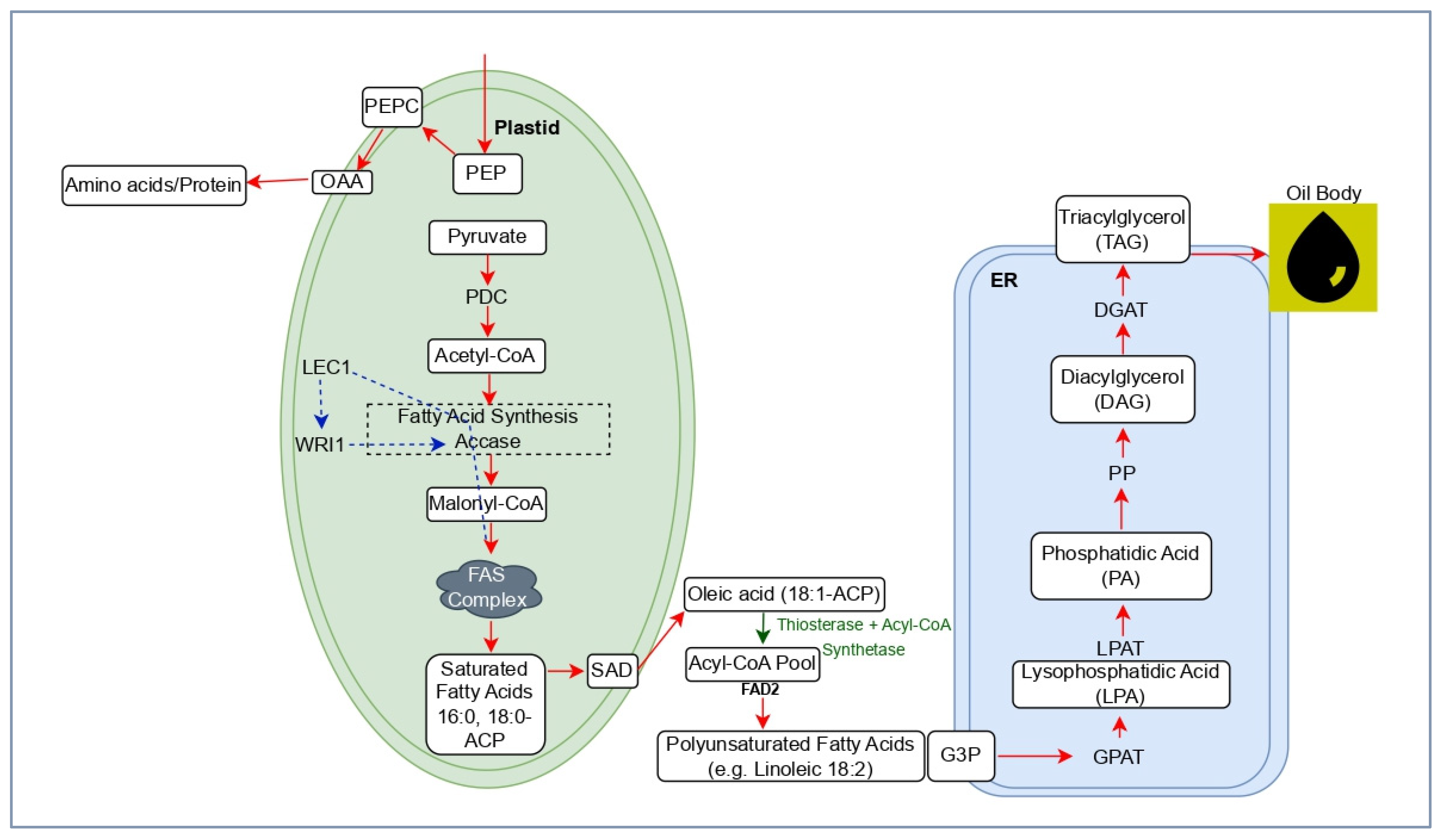

2. Overview of Cottonseed Oil Biosynthesis

Biosynthesis of cottonseed oil begins in the plastids of developing seed cells and ends in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) due to a synchronized process that involves the synthesis of fatty acids, their desaturation, and the assembly of triacylglycerol (TAG) [

13] (

Figure 1) . In cottonseed, the Kennedy pathway is the main pathway for TAG chain synthesis, involving the use of glycerol-3-phosphate to assemble fatty acids into TAGs, which are the primary form of seed oil storage [

14,

15]. The process starts with the production of acetyl-CoA in the plastids, which is converted to malonyl-CoA by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase). The fatty acid synthesis (FAS) complex uses palmitic and stearic acids to elongate the fatty acid chains. These saturated fatty acids are exported from the plastids into the cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum, where they are combined with glycerol backbones through enzymes of the Kennedy pathway [

16]. The final step involves the enzyme diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT), which converts diacylglycerol (DAG) into TAG that forms seed oil bodies [

8] (

Figure 1). The conversion of stearic acid to oleic and other fatty acids is catalyzed by stearoyl-ACP desaturase (SAD) and fatty acid desaturase 2 (FAD2), resulting in cottonseed oil composed of approximately 25 percent palmitic acid, 18 percent oleic acid, and 55 percent linoleic acid. Modifying desaturase activity, particularly FAD2, enhances oxidative stability and the viability of the oil, thereby improving its nutritional quality [

17].

Numerous essential enzymes and transcriptional regulators coordinate the movement of carbon in the cottonseed oil biosynthetic pathway. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase) initiates plastidial fatty acid production by converting acetyl-CoA into malonyl-CoA, acting as a rate-limiting factor that affects overall oil output [

18]. Within the endoplasmic reticulum, FAD2 converts oleic acid into linoleic acid, which influences oil quality and stability; specifically, downregulating FAD2 has been shown to increase oleic acid levels [

19]. The final, decisive stage of TAG synthesis is driven by DGAT, whose higher expression in cotton correlates with increased oil storage [

8] (

Figure 1). At the transcript level, Leafy Cotyledon1 (LEC1) is a critical developmental regulator that initiates seed development processes, including the activation of wrinkled1 (WRI1), a major transcription factor that enhances glycolytic enzyme activity and regulates fatty acid biosynthesis genes [

20]. Collectively, these enzymatic and regulatory components form an integrated network that controls the quantity and composition of cottonseed oil and provides multiple genetic targets to improve yield and quality.

Cottonseed oil is biosynthetically regulated during development and follows the embryo's maturation. TAG accumulation typically begins at 15 Days Post Anthesis (DPA), peaks at 25- 35 DPA, corresponding to the late globular to the cotyledon phases of embryo development [

21]. This step is characterized by the shifting of metabolism to the compound accumulation at the expense of cell growth as carbon components of photosynthesis are channeled to the biosynthetic mechanism of fatty acids and oils. The time course studies of transcriptome in upland cotton suggests that

WRI1, LEC1, FUS3, and ABI3 reveal the expression profiles that peak at the time of late and mid seed development and are consistent with their role in regulating storage-related gene activation [

22,

23]. In addition, the use of sugar signaling and hormonal cues (i.e., abscisic acid (ABA) signals) in controlling the regulation of oil biosynthesis genes during this growth stage is vital [

24]. It has been linked that the temporal control mechanisms of oil synthesis, vital genes, involve epigenetic regulation such as histone acetylation and DNA methylation [

25]. The developmental and environmental responsive seed-specific promoters and cis-regulatory elements provide a means by which oil characteristics may be altered very specifically. Also, gene expression timing is of paramount importance in cotton because the coinciding processes of fiber maturation and seed growth pose unique constraints when it comes to source and sink optimization and trait uncoupling as a part of any breeding programme [

3,

26].

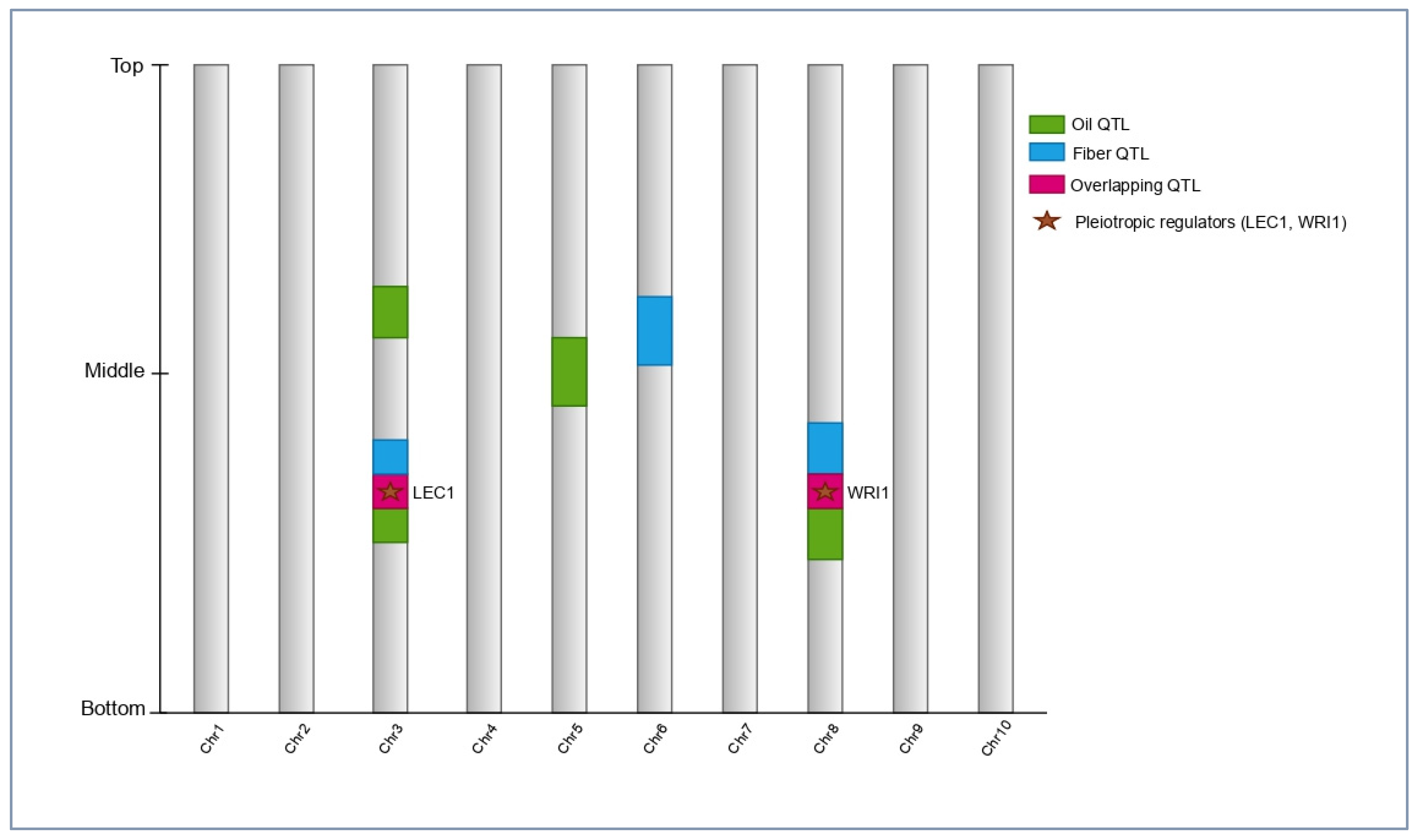

3. Genetic Architecture of Oil and Agronomic Traits

Cottonseed oil content in upland cotton (

Gossypium hirsutum) is a typical quantitative trait controlled by many genes, each contributing small- and moderate-effect, and influenced by lipid-pathway genes along with the source-sink acts of the plant. Recent linkage mapping, genome-wide association studies, and systems analyses point to a scenario where oil genes are often proximate, or overlapping, with genes affecting seed size, lint yield, and fiber quality, so that a correlated selection response is the norm rather than an exception [

27,

28] (

Figure 2). Many QTLs of seed oil content (SOC) have been identified across bi-parental populations and diversity panels, some of which are consistent across environments, and others having strong G x E interactions. For example, a 140-line RIL population grown in multi-environments identified novel SOC QTL and narrowed down relevant intervals, with recessive inheritance of some and diverse oil-soluble fractions [

27].

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) of Cotton SNP63K/80K arrays has localized SOC with dozens of SNPs widely distributed throughout the A and D sub genomes; many coincide with lipid-pathway candidates (e.g., acyltransferases, desaturases), supporting a common genetic background between oil accumulation and seed development [

29,

30]. Linkage studies have also reported major-effect loci (e.g., qOil-3), which indicates that despite the polygenicity of SOC, larger-effect QTL can be identified to assist in marker-assisted introgression [

31]. Meta- and integrative mapping allows us to identify two useful categories of regions: (i) regions nearly identical that influence both SOC and yield/oil traits (facilitation or antagonism), and (ii) H/R regions that reflect both clean opportunities to enhance oil without lint cost and clean opportunities to increase lint without oil cost. Network-based approaches, such as Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), have begun to prioritize candidates within these regions, for example, a glycosyl-hydrolase (

GhHSD1) related to oil-accumulation networks, demonstrating how network context can be used to distinguish between shared and trait-specific nodes [

28] (

Table 1).

The primary limitation of pleiotropy is that a single gene can code for only one trait. Regulators of seed development/seed maturation (the LAFL module: LEC1/LEC2/FUS3, plus ABI3) and the master regulator of lipid metabolism, WRI1, together coordinate not only glucose as a carbon distribution resource but also seed morphology and composition. Their activity can be used to explain the correlated change in oil, protein, and seed size noticed in the mapping populations [

38,

39]. There is now converging evidence for cotton-specific functional roles: seed-specific expression of a cotton

AtWRI1 transgene, in

G. hirsutum, increased seed oil content, reinforcing WRI1 as a point of leverage in pleiotropic networks [

40]. Historical emphasis on lint yield may have exacerbated the biased correlations at the population level by selection and reduced diversity, making favorable alleles under fiber more rare in elite genetic backgrounds and giving linkage drag at the fiber-improvement loci greater practical importance [

8,

41].

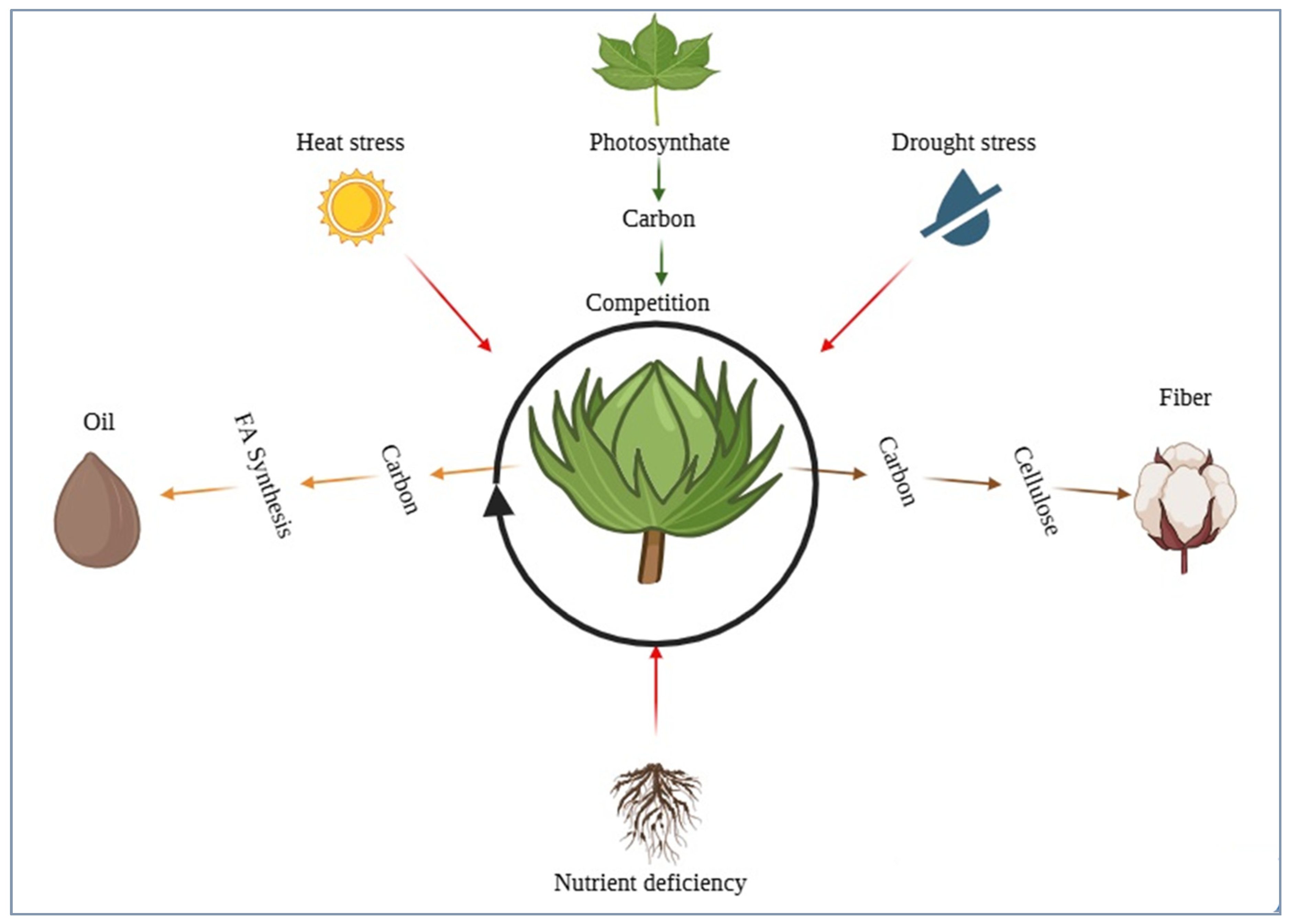

4. Trait Interactions: Phenotypic and Genetic Correlations

The relationships between traits that determine cottonseed oil content (SOC) arise both through genetic and whole-plant source-sink physiology during boll and seed filling. Correlations among SOC, lint yield, seed weight, and seed protein in cross-mapping panels and breeding populations are influenced by background and environment and vary in sign and magnitude, indicating polygenic control and G x E. However, there are several stable patterns.

4.1. Oil vs. Lint Yield

It has long been expected that there is competition between developing fibers and seeds for assimilates. Physiologically, as the boll load increases, assimilate supply gets tightened and there occurs a change in the relative balance between the source strength (photosynthesis) of the plant and the competing sinks (fibers, embryos) [

42,

43] (

Figure 3). Empirically, a negative correlation between SOC and lint yield does not always apply (

Table 2). In a multiple-environment selection experiment, both lint and seed yields have had relatively little or unimportant correlations with oil, and certainly not the strict genetic antagonisms that may be expected; hence, at least in carefully selected environments and germplasm, increases in both yields are quite possible [

44].

Concurrently, other germplasm surveys and path-analyses have found negative associations between seed cotton yield and SOC, which is in line with competitive interactions in certain genetic backgrounds or management systems. The differences highlight the role of environment, boll load, and canopy photosynthesis in defining realized correlations [

45,

46]. Breeding schemes can prevent a universal reduction in lint by targeting SOC loci that are unrelated to Yield-TQTLs and by controlling source-sink during selection nurseries (e.g., stress mitigation, optimal fruit-fruiting) [

43].

4.2. Oil vs. Seed Weight and Protein

The dominance of embryo reserves makes SOC frequently correlated with seed size and seed index, but frequently negatively with seed protein, which reflects biochemical storage pathways of carbon vs. nitrogen. A synthesis chapter on cottonseed oil genetics reports negative oil-protein correlations and associations with yield components (seed cotton yield, lint %, seeds/boll), illustrating how storage networks compensate for reproductive allocation [

52]. Large-scale GWAS (n = 500 accessions; eight environments) yielded extremely high broad-sense heritability of SOC (H² = 80.97) and consistent marker-derived genotype ranks, suggesting that although correlation is inevitable, SOC could be selected selectively, and perhaps independently of seed weight/protein, when marker data are available [

53].

Comparative omics during seed filling indicates that carbon partitioning pathways (glycolysis, fatty acid/TAG assembly) co-vary with oil accumulation, whereas shifts towards phenylpropanoid/secondary metabolism can antagonise oil deposition- an indication of the mechanism behind observed trade-offs with other seed constituents [

34,

54]. Whether direct index selection on SOC and seed size can be effectively conducted is an open question because, as noted, antagonism between oil and protein can be the limiting factor, and perhaps more editing or selective editing/regulation of master nodes to favor TAG production without also reducing amino acid/N assimilation is necessary [

34].

4.3. Fiber Traits vs. Seed Traits

Fiber initiation and elongation take place on the seed epidermis, which precedes embryo reserve accumulation. Reviews of cotton source-sink physiology highlight that when boll load is high, assimilate competition escalates; any environmental stress (heat, drought) decreases source strength, augmenting trade-offs between fiber growth and seed filling [

42,

43] (

Figure 3). On the genetic side, fiber-quality GWAS on multi-environment trials reveal plentiful loci with small effect and extensive G x E, which recapitulate SOC architecture. Co-localization of QTL fiber traits, seed size, and SOC contributes to understanding how favorable responses to these traits may be correlated but antagonistic in other haplotypes [

55]. Additional network-directed analysis indicates that there can be modules associated with lipid metabolism that are independent of (or partly overlap with) fiber-development modules; finding non-overlapping loci that are evolving under selection due to fiber-enhancement efforts thus has the potential to decrease genetic drag on regions that are under selection by fiber-improvement strategies.

A combination of physiological and genomic intervention would seem to be suitable to mitigating fiber to seed trade-offs. The goals of physiological management should be to maintain source strength through enhancement of photosynthetic capacity, adequate efficiency of nutrient and water use and reduction of effects of environmental stress. At the same time, genomic studies should aim at better prediction of SOC-related loci and regulatory modules to separate fiber elongation and seed reserve deposition. This kind of physiology-genomics integration would improve the assimilate availability, but the genetic factors could be fine-tuned selectively, and the resultant balance between fiber quality improvement, seed development and yield stability could be achieved.

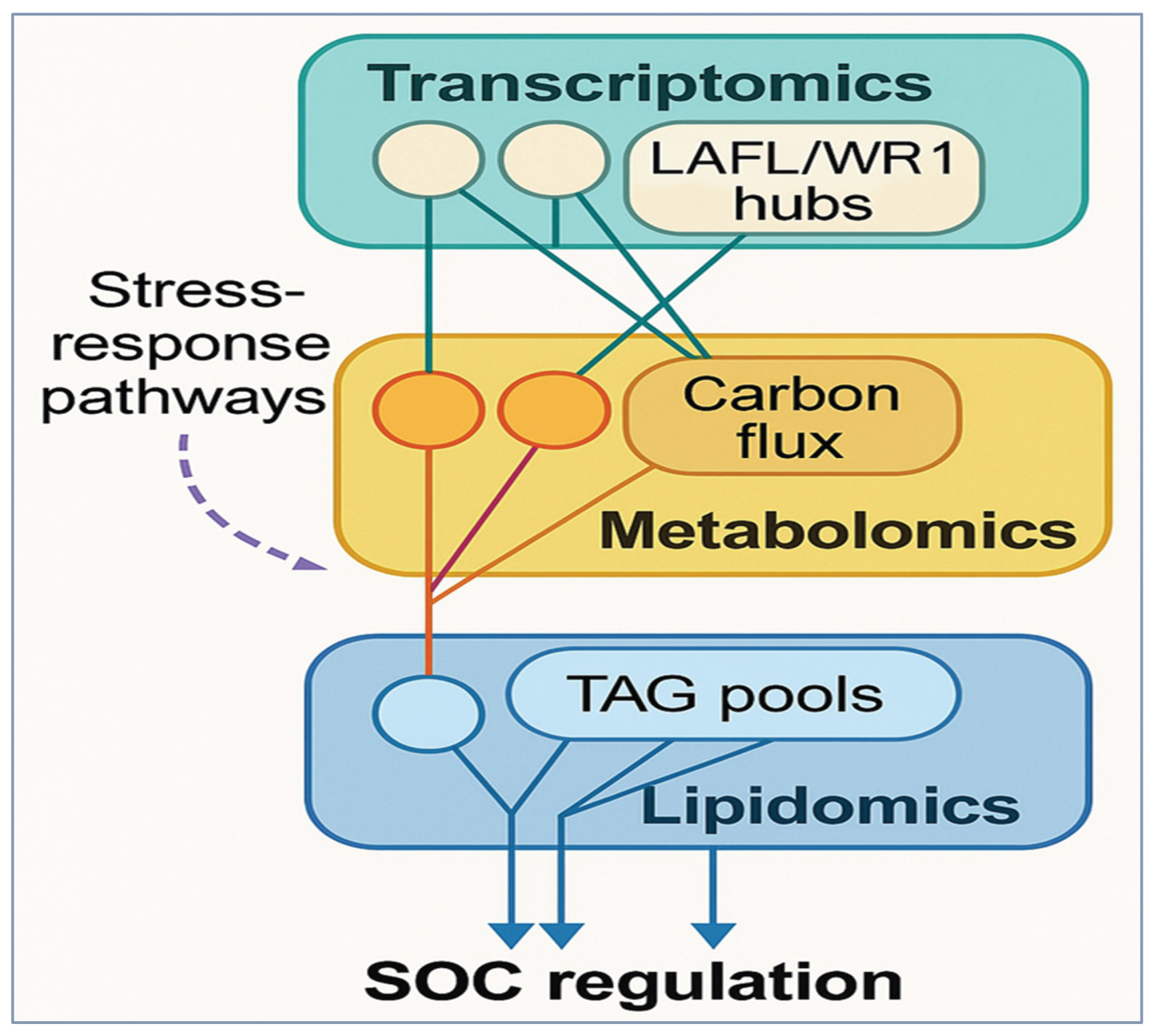

5. Molecular Insights from Omics

The breakthrough in high-throughput omics, including transcriptomics, co-expression networks, metabolomics, and lipidomics, among others, has significantly enhanced our understanding of the molecular network that regulates cottonseed oil content (SOC) and interacts with major agronomic traits. The similarities and differences in the approaches demonstrate that regulatory networks, biochemical pathways, and carbon flux dynamics all interact to define SOC and the tradeoffs associated with fiber and seed traits. Transcriptomic profiling has emphasized the key role of seed maturation regulators in the process of oil biosynthesis. During mid-to-late embryogenesis, the LAFL transcription factor complex (LEC1, ABI3, and FUS3) is strongly induced, which correlates with the peak period of TAG deposition and integrates both TAG and protein synthesis [

33] (

Figure 4). WRI1 (WRINKLED1) stands out as a key control factor: the seed-specific expression of

AtWRI1 in

Gossypium hirsutum resulted in an impressive ~35 percent increase in seed oil, accompanied by a fourfold increase in oil body quantities [

40]. A genome-wide search in cotton identified 22 WRI-like genes, whereas in vivo characterization of one of them,

GhWRI1a, demonstrated that it can confer increased oil synthesis in heterologous model plants, confirming its conserved gene regulatory role [

33].

Candidate gene identification has further benefited from co-expression network analyses, especially WGCNA. An integration of QTL analysis and network data identified

GhHSD1, a glycosyl hydrolase, as a novel regulator of oil biosynthesis. Transgenic

Arabidopsis, when overexpressed, showed an increased seed oil content, indicating that

GhHSD1 indeed has a functional role in oil biosynthesis [

28]. These modules tend to overlap with hormone-signaling pathways (e.g., ABA, auxin), thereby imposing a layered regulation that combines developmental cues with metabolic regulation [

34,

56]. In addition, genome-based studies indicate that cotton has clusters of genes involved in lipid metabolism, such as desaturases and acyl-CoA synthetases, which are also preferentially expressed in seeds, suggesting co-regulation that supports the requirements of fiber elongation and oil storage [

28].

Metabolomic and lipidomic methodologies can be used as complementary biochemical validation. Comparative studies of high- and low-oil accessions of cotton reveal that high-oil genotypes have higher pools of glycolytic intermediates and fatty acyl-CoAs, and low-oil lines channel carbon toward secondary metabolism, particularly phenylpropanoids and flavonoids [

34]. Lipidomic profiling reveals strong intraspecific variation in TAG composition, especially in the oleic-to-linoleic ratio related to variation of the FAD2 locus. In upland cotton, knockout of

GhFAD2-1A/D with CRISPR/Cas9 significantly increased oleic acid content (approximately 75-77 percent) and decreased linoleic acid without adverse impacts on fiber quality or seed germination [

8,

32,

57]. Studies involving isotope labeling further indicate that conversion of sucrose to hexose is a key metabolic bottleneck that determines whether assimilates are channeled into fiber extension or oil production- providing insights into the physiology underpinning trait trade-offs [

54].

Collectively, these combined omics data present the regulation of SOC as a systems-level process. In one example, a GWAS of more than 500 accessions across multiple environments revealed extremely high heritability of SOC (H² = 0.966), yet significant portions of the variation were driven by transcriptional divergence at metabolic hubs [

53]. Further, the modules of lipid biosynthesis are often found to overlap with stress-response mechanisms, explaining why SOC incur abiotic stresses [

34] (

Figure 4). In short, omics technologies come together on a story that master regulators such as WRI1 and LAFL factors integrate seed development and oil biosynthesis, co-expression networks indicate the interplay with hormonal and developmental signaling, and resource allocation and variability in composition are elucidated by metabolomics/lipidomics. This set of layers characterizes SOC as an emergent property of networked regulation and provides a fertile foundation for applying systems biology approaches to simultaneously enhance seed oil content and fiber yield in cotton.

6. Breeding Challenges and Trade-Offs

Advances in fiber yield and quality have routinely outpaced advances in cottonseed oil content and quality due to a combination of biological, technical, and institutional obstacles. The renewed optimism offered by advances in molecular tools and underlying genomic resources notwithstanding, seed oil traits and their interaction with fiber-related traits are complex and put genetic enhancement under particular strain.

6.1. Genetic Bottlenecks and Limited Diversity

Among the most urgent limitations is the existence of a small genetic base of upland cotton

(Gossypium hirsutum). Historically, modern breeding programs have focused on fiber yield, lint percentage, and staple length at the expense of seed-related traits. This knowledge prioritization has resulted in allelic diversity being low in oil-related loci, which has constrained the capability of breeders to utilise natural variation [

8]. Although wild species of cotton, such as

G. barbadense, G. arboreum, and G. herbaceum, have higher seed oil content and other more desirable qualities, including fatty acid compositions, these attributes are limited by reproductive barriers and linkage drag. In

G. barbadense, transferring of high-oil alleles is frequently associated with the co-introduction of undesirable fiber or other agronomic traits that preclude their use in commercial breeding [

52].

6.2. Antagonistic Trait Correlations

The greatest challenge has been the negative relationships between seed traits of interest and important agronomic or seed quality traits. An example of this is the inverse relationship between oil and protein concentration in cottonseed, as they compete for access to the carbon and nitrogen supply during the seed-filling period [

30]. Similarly, an increase in lint percentage, one of the principal determinants of fiber profitability, is associated with reduced seed index (seed size/weight), which subsequently compromises oil yield/hectare [

58]. These tradeoffs are not absolute, but are due to more complex pleiotropic interactions as well as to linkage relationships. In recent studies of QTL in multi-parent advanced generation inter-cross (MAGIC) populations, it has been confirmed that there exist some alleles that both positively and negatively affect lint yield and oil content simultaneously [

59]. Therefore, it is one of the breeding challenges to decouple these correlations.

6.3. Phenotyping Limitations

Cottonseed oil content cannot be observed or estimated easily or visually factor and must be quantified using destructive sampling and chemical methods. Conventional systems, e.g., Soxhlet and gas chromatography, are precise but time-consuming, labour-intensive, and cumbersome in massive screening efforts in the primary half-breed generation. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has been proposed as a fast and non-destructive alternative, but its use remains limited to date, with calibration across genotypes and environments being required [

48]. This bottleneck of phenotyping has led to a situation where oil properties are rarely included in the majority of breeding pipelines, which have only served to marginalise the property further. Consequently, breeders seldom record the seed oil dynamics on the same selection trials that they are noting fiber traits.

6.4. Genotype × Environment Interactions

The characteristics of cottonseed oil exhibit a high level of genotype-by-environment (G x E) interactions, which makes stable advancements challenging. Increased temperature, adequate water availability, and soil fertility affect the content and composition of oil and fatty acids in the seeds during development. To illustrate, high temperatures at the time of boll filling may promote the formation of greater amounts of saturated fatty acids, thus reducing nutritional value [

60]. Multi-environment trials indicate that high oil content under the controlled conditions may exhibit inconsistent performance in the field. This lack of stability makes breeding difficult, as it involves improving both the mean performance and stability of the trait across a variety of environments simultaneously.

6.5. Institutional and Breeding Priorities

Lint productivity remains a priority for institutions with oil characteristics, with oil production as a secondary or tertiary trait. Cotton breeding is often sponsored and/or measured in terms of fiber yield increment, rather than seed quality improvement. Such a structural bias reveals why significant genetic and genomic resources for oil biosynthesis have not been fully converted into breeding outcomes [

61]. The degree to which progress is slow due to a lack of targeted funding and integration of oil content in breeding objectives will continue to leave the dual-purpose of cotton as both a fiber and oilseed crop unexploited.

7. Strategies to Bridge the Divide

The delivery of cotton ideotypes that combine high-quality fiber with improved seed oil requires the combination of strategies that will (i) address antagonistic correlations, (ii) expand the exploitable genetic base, and (iii) speed up selection in the real-world settings. We summarize below the progress in multi-trait genomics, pre-breeding using exotic/wild germplasm, precise genome editing, and systems-level design, as well as practical observations on how these can be applied in breeding programs.

7.1. Multi-Trait QTL Dissection and Genomic Prediction

Multi-trait QTL mapping helps distinguish pleiotropy and tight linkage, and determines when oil and fiber loci can be separated by recombination and when regulatory edits are necessary. Multi-environment GWAS of SOC has identified QTLs at several chromosomes (e.g., A- and D-subgenomes), which offer selection marks and a framework to fine-map and then validate a candidate [

28]. Recent quantitative-genomics studies further quantify the extent to which selection on lint percent, seed index, lint yield, and SOC co-moves are inverse (generally, weak to moderate) correlations that can still be surmounted using index-based or multi-trait models [

37].

Genomic selection (GS) is particularly appealing to SOC since it minimizes reliance on the destructive phenotyping and facilitates multi-trait prediction at G x E. Public breeding program reviews describe operational pipelines (training population design, cross-validation under target environments, retraining cadence), and claim that GS could expedite cotton gains and still incorporate pre-breeding diversity [

36]. With decreasing costs of genotyping and training resources that span across the environment, breeders can apply multi-trait, multi-environment (MT-ME) models to trade off the accuracy of SOC versus fiber quality and yield stability.

7.2. Widening the Genetic Base: Pangenomes and Pre-Breeding Resources

The recent assemblies of the pangenome and multiple references demonstrate that the upland cotton gene pool includes significant structural variation and presence/absence variants that are not seen by single references- variation that overlaps with domestication sweeps, introgressions, and agronomic loci [

62,

63]. A recent pangenome-scale study highlights the fact that graph-based representations can be more useful for estimating the allelic diversity underlying yield and fiber characteristics, which are manifestly SOC discoverable and deployable resources [

64].

The translation of this variety into elite backgrounds is based on pre-breeding populations. Chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) provide near-isogenic windows to identify small-effect QTL between seed and fiber traits and uncouple linkages; inter- and interspecific CSSLs and novo sets based on G

. tomentosum indicate results of tractable introgressions on seed-related traits [

65,

66]. Nested association mapping (NAM) is a complement to CSSLs, combining GWAS-like resolution with family-based power in complex traits, providing a path to the decomposition of SOC-related variation and estimation of pleiotropic load [

67,

68]. Collectively, pangenomic discovery + CSSL/NAM validation shorten the route between locus and breeder-ready haplotypes, including ones that breed more as oils rise and less fiber is present.

7.3. Precision Genome Editing to Break Unfavorable Linkages

CRISPR/Cas provides specific modifications that increase the production of oil quantity and quality with minimal collateral implications on fiber. Knockout of

GhFAD2-1A/D in allotetraploid cotton resulted in non-transgenic, high-oleic lines (~75-77% oleic acid) with consistent agronomic performance, and the example of a clean pathway to enhance oxidative stability of cottonseed oil [

32]. The oil profiles and protein trade-offs are also regulated by the natural or artificial alleles of FAD2, and it provides an allelic series to compose customized compositions [

69]. Parallel seed-specific up-regulation of WRI1 (or editing of its cis-regulatory motifs) boosts flux through glycolysis and fatty acid biosynthesis (recent seed-targeted expression of

AtWRI1 in cotton boosts SOC, supporting WRI1 as a lever without apparent fiber penalty) [

40]. In the future, pathway flux can be tuned only in seeds with regulatory (promoter/enhancer) editing, base/prime editing, and multiplexed edits (e.g., stacking WRI1, DGAT, and acyl-editing enzymes), and without pleiotropic effects on fibers. Theoretical and experimental research in the field of plant metabolic engineering provides these approaches to oil crops and is becoming more malleable to cotton [

63].

7.4. Integrating Exotic/Wild Alleles

Individual wild and exotic Gossypium accessions possess greater SOC and new fatty-acid profiles but are associated with linkage drag and incompatibilities. Reviews and case studies have demonstrated that a stepwise method, (i) QTL discovery in interspecific populations, (ii) validation using CSSLs/NAM, (iii) haplotype-based selection in backcross schemes, and (iv) surgical CRISPR fixes to eliminate residual drag, can provide breeder-ready haplotypes at a rate superior to classical backcrossing by itself [

8,

65]. Multi-reference genomes of high quality now assist in the identification of structural variants that are transmitted by wild donors, enabling selection against deleterious blocks and retention of desirable SOC alleles [

70].

7.5. Systems Biology and Source–Sink Optimization

Since SOC competes with lint for assimilates, systems models that couple transcriptional control, metabolite pools, and carbon flux are necessary to design edits and selection indices that do not compromise fiber performance. Classical and modern syntheses of source-sink dynamics in cotton define the locations of transport, partitioning, and hormonal control; by combining these with SOC networks (e.g., WRI1/LAFL hubs), direct interventions can be made to reestablish balance in allocation during boll filling [

43,

71]. Field-based physiology affirms that within-canopy light and water regimes influence carbon partitioning--a lesson to keep in mind that genetic solutions should be accompanied by agronomy to achieve SOC benefits [

72]. Multi-omics meta-analyses on cotton germplasm reveal that high-oil phenotypes increase the expression duration and amplitude of oil-gene expression. This lever can be achieved through promoter editing or transactivation in seed tissue [

73].

7.6. Breeding Pipelines: Phenotyping, Indices, and G×E

The application of G×E implies phenotyping at scale and selection to enable deployment. In modern quantitative models, emphasis is put on constructing multi-trait selection indices where lint, seed, and oil yields are explicitly weighted; recent field analysis quantifies the trade-off magnitudes (e.g., lint percent/ seed index; lint or lint percent/ SOC) and offers templates to optimize indices in line with end-use economics [

37]. Multi-environment QTL of ultra-high oil lines on the discovery side demonstrate that stable SOC loci can be revealed through replicated field tests coupled with dense markers [

27]. With the implementation of GS, population refresh and environmental covariates are the focus of the guidance at the program level, including cost-effective genotyping, which is essential for SOC because destructive phenotyping is the bottleneck [

36].

8. Future Directions

The dual-purpose improvement of upland cotton, balancing the productivity of the fiber with that of seed oil, requires future-oriented strategies that transcend the present genomic and breeding innovations. A combination of multi-omics datasets, machine learning methods, climate-resilient breeding pipelines, and innovations in synthetic biology is likely to accelerate the development of cotton ideotypes suited for the 21st century.

8.1. Integrating Multi-Omics and Machine Learning

The generation of large datasets obtained through genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics presents an unprecedented possibility to comprehend the interactions of many traits in cotton. The difficulty is, however, to bring these heterogeneous layers of data into actionable knowledge. Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are finding wide use in plant science to discover concealed patterns, forecast gene-trait correlations, and precision breeding. ML-based predictive models are under development in cotton to predict oil composition, seed quality, and yield stability, combining SNP variation with expression and metabolite information. For example, deep learning models have already been able to increase the accuracy of genomic prediction of seed traits in other oilseed crop varieties, and such methods are under development to apply to cotton. Combining multi-omics + ML pipelines in the near future will allow breeders to prioritize candidate genes, simulate regulatory networks, and construct an optimal selection strategy to increase two traits.

8.2. Climate-Smart Dual-Trait Breeding Pipelines

Climate change is a significant threat to cotton production, and increasing temperatures, drought, and salinity stress affect fiber production and oil accumulation. Therefore, climate-smart breeding should become a fundamental part of cotton improvement. The next generation pipelines will be built to incorporate phenomics platforms, crop models, and genomic selection under multi-environment tests to select the genotypes with balanced fiber and oil productivity when under stress. It has already been established that heat and water stress influence carbon partitioning of lint and seed oil, so ideotypes of adaptation to climate will require regulation of sources and sinks optimally. Moreover, high-throughput phenotyping can be used in conjunction with speed breeding and doubled haploids to accelerate the generation turnover, allowing dual-purpose cultivars to be delivered faster to meet the changing climate.

8.3. Synthetic Biology for Oil Trait Enhancement

Synthetic biology is a revolutionary edge to cottonseed oil enhancement. Synthetic biology enables the rewiring of lipid biosynthesis by engineering metabolic pathways to enhance oil accumulation, alter fatty acid composition, and lower anti-nutritional compounds, including gossypol. To illustrate this, synthetic promoters and CRISPR-based transcriptional activators have been implemented in model plants to enhance TAG biosynthesis without causing harmful growth impacts. The same strategies could be applied to cotton to selectively regulate the deposition of oil in seeds by using regulators such as WRI1, DGAT, and LEC1. Moreover, developments in plastid engineering could permit more effective redirection of the carbon flux to oil accumulation, potentially decoupling oil enhancement and fiber yield limitations. Synthetic biology could also enable the design of cotton as a biofactory to produce specialty oils of nutraceutical fatty acids, extending the economic usefulness of the crop beyond the textile and standard vegetable oil markets.

9. Conclusion

Cotton

(Gossypium hirsutum L.), which has long been considered the most significant fiber crop in the world, is now being actively considered as a dual-purpose species with huge potential to play a role in global edible oil and protein production. Nevertheless, the enhancement of cottonseed oil content and quality has been limited by the historical focus on fiber yield and quality, as well as by genetic, physiological, and breeding trade-offs. This review identifies the multifaceted genetic basis of cottonseed oil characters, regulated by polygenic interactions and compounded by pleiotropy and linkage drag with loci related to fibre. The existence of trade-offs (oil vs. lint yield or oil vs. protein content) is validated by phenotypic and genetic correlation, and is to a large extent due to underlying source-sink interaction. Transcriptomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics have identified several central regulatory nodes, such as WRI1, ABI3, and LEC1, that coordinate seed metabolism and carbon partitioning, and are potential molecular therapeutic targets for genetic engineering [

74]. Although these progress improvements have been achieved, there are still challenges, such as the limited genetic foundation of elite cultivars, selection pressures that interfere with simultaneous seed and fiber improvement, a deficiency in high-throughput phenotyping systems, and the added pressure of climate change on source-sink relationships.

Going forward, integrative approaches including multi-trait QTL mapping and genomic selection, the introduction of desirable alleles into the germplasm of the wild Gossypium, the use of CRISPR/Cas9 and synthetic biology to uncouple negative interactions and systems biology modeling enabled by machine learning can promise to overcome these limitations. The realization of this potential will entail policy support that makes cotton a dual-purpose crop, as well as investment in advanced infrastructures for omics and phenotyping, an international germplasm exchange, and capacity building in cotton-growing regions. Finally, the creation of climate-smart, dual-purpose cotton ideotypes that allow for the generation of high-quality fiber with increased nutritional and protein concentrations will make cotton a truly multipurpose commodity, enhancing its economic and nutritional value, as well as aligning its production with the global population's food security and sustainability objectives.

Funding

This research was supported by the Biological Breeding-Major Projects in National Science and Technology (2023ZD04038), the Key Research and Development Program of Xinjiang (2024B02001-1), and Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Author Contributions

Writing original draft, IMA; Conceptualization of the manuscript, YZ and IMA; Formal analysis, JP; funding acquisition, YZ; Visualization, KKF; Writing -review & editing, YZ, SZ, and ZA; Validation, SF; Supervision, JY and YL; Review, WC and MIA. All authors contributed in the critical follow up of the work, read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely grateful to all the teachers and students in our research team for their valuable contributions in one way or the other during the course of this review work. We are thankful to Dr. Aminu Inuwa Darma (Institute of Environmental Science, GSCAAS, China) and Muhammad Aameer Khan (Institute of Crop Science, GSCAAS, China) for proof reading, insightful comments on the manuscript, and helpful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no any known conflicts interest.

References

- Gunstone F. Vegetable oils in food technology: composition, properties and uses: John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

- Zubai̇r, M.F.; Ibrahi̇m, O.S.; Atolani̇, O.; Hamid, A.A.; Atolani̇, A. Chemical Composition and Nutritional Characterization of Cotton Seed as Potential Feed Supplement. J. Turk. Chem. Soc. Sect. A: Chem. 2021, 8, 977–982. [CrossRef]

- Constable G, Llewellyn D, Walford SA, Clement JD. Cotton breeding for fiber quality improvement. Industrial crops: Breeding for bioenergy and bioproducts: Springer; 2014. p. 191-232.

- Rathore, K.S.; Pandeya, D.; Campbell, L.M.; Wedegaertner, T.C.; Puckhaber, L.; Stipanovic, R.D.; Thenell, J.S.; Hague, S.; Hake, K. Ultra-Low Gossypol Cottonseed: Selective Gene Silencing Opens Up a Vast Resource of Plant-Based Protein to Improve Human Nutrition. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2020, 39, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Younas AY, Parveen A, Waqar S. Versatile Applications, Challenges, and Future Prospects of Cottonseed Oil. BinBee–Arı ve Doğal Ürünler Dergisi. 2025;5(1):24-33.

- Riaz, T.; Iqbal, M.W.; Mahmood, S.; Yasmin, I.; Leghari, A.A.; Rehman, A.; Mushtaq, A.; Ali, K.; Azam, M.; Bilal, M. Cottonseed oil: A review of extraction techniques, physicochemical, functional, and nutritional properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 63, 1219–1237. [CrossRef]

- Blair R, Regenstein JM. Oilseed crops. Genetic Modification and Food Quality: A Down to Earth Analysis. 2015.

- Wu, M.; Pei, W.; Wedegaertner, T.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J. Genetics, Breeding and Genetic Engineering to Improve Cottonseed Oil and Protein: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 864850. [CrossRef]

- Wittkop, B.; Snowdon, R.J.; Friedt, W. Status and perspectives of breeding for enhanced yield and quality of oilseed crops for Europe. Euphytica 2009, 170, 131. [CrossRef]

- Amer, E.A.; El-Hoseiny, H.A.; Hassan, S.S. Seed Oil Content, Yield and Fiber Quality Traits in Some Egyptian Cotton Genotypes. J. Plant Prod. 2020, 11, 1469–1467. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gong, W.; Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Liu, A.; Ge, Q.; Pan, J.; Fan, S.; et al. Identification and analysis of oil candidate genes reveals the molecular basis of cottonseed oil accumulation in Gossypium hirsutum L.. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 135, 449–460. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gong, W.; Li, J.; Shi, Y.; Liu, A.; Ge, Q.; Pan, J.; Fan, S.; et al. Identification and analysis of oil candidate genes reveals the molecular basis of cottonseed oil accumulation in Gossypium hirsutum L.. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 135, 449–460. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Llewellyn DJ, Singh SP, Green AG. Cotton seed development: opportunities to add value to a byproduct of fiber production. Flowering and fruiting in cotton. 2012:131-62.

- Voelker, T.; Kinney, A.J. VARIATIONS IN THE BIOSYNTHESIS OF SEED-STORAGE LIPIDS. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2001, 52, 335–361. [CrossRef]

- Cotton KL. Genetic and biochemical analysis of essential enzymes in triacylglycerol synthesis in Arabidopsis: Washington State University; 2015.

- Shamsi, I.H.; Shamsi, B.H.; Jiang, L. Biochemistry of fatty acids. Technological Innovations in Major World Oil Crops, Volume 2: Perspectives: Springer; 2011. p. 123-50.

- Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Jin, S.; Zhang, X. Metabolic engineering of cottonseed oil biosynthesis pathway via RNA interference. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33342. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Singh, S.; Chapman, K.; Green, A. Bridging traditional and molecular genetics in modifying cottonseed oil. Genetics and genomics of cotton: Springer; 2009. p. 353-82.

- Zhao, S.; Sun, J.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, C.; Pan, J.; Hou, L.; Tian, R.; Wang, X. Insights into the Novel FAD2 Gene Regulating Oleic Acid Accumulation in Peanut Seeds with Different Maturity. Genes 2022, 13, 2076. [CrossRef]

- Baud, S.; Mendoza, M.S.; To, A.; Harscoët, E.; Lepiniec, L.; Dubreucq, B. WRINKLED1 specifies the regulatory action of LEAFY COTYLEDON2 towards fatty acid metabolism during seed maturation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007, 50, 825–838. [CrossRef]

- Aulakh KS. Transcriptomic and lipidomic profiling in developing seeds of two Brassicaceae species to identify key regulators associated with storage oil synthesis: Kansas State University; 2018.

- Verdier, J.; Thompson, R.D. Transcriptional Regulation of Storage Protein Synthesis During Dicotyledon Seed Filling. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 1263–1271. [CrossRef]

- Van Wuytswinkel O. Combined networks regulating seed maturation. Trends in Plant Science. 2007.

- Wang, N.; Tao, B.; Mai, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, R.; Chen, R.; Zhao, L.; Wen, J.; Yi, B.; Tu, J.; et al. Kinase CIPK9 integrates glucose and abscisic acid signaling to regulate seed oil metabolism in rapeseed. Plant Physiol. 2022, 191, 1836–1856. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Di Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.-Z.; Xu, W.; Liu, A. Epigenetic regulation of seed-specific gene expression by DNA methylation valleys in castor bean. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 57. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kong, Q.; Lim, A.R.; Lu, S.; Zhao, H.; Guo, L.; Yuan, L.; Ma, W. Transcriptional regulation of oil biosynthesis in seed plants: Current understanding, applications, and perspectives. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100328. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, M.; Shahzad, K.; Zhang, X.; Guo, L.; Qi, T.; Tang, H.; Shi, L.; Qiao, X.; et al. Integrated multiple environmental tests and QTL mapping uncover novel candidate genes for seed oil content in upland cotton. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 220. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Jia, B.; Bian, Y.; Pei, W.; Song, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Feng, P.; et al. Genomic and co-expression network analyses reveal candidate genes for oil accumulation based on an introgression population in Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Ma, J.; Song, J.; Jia, B.; Yang, S.; Wu, L.; Huang, L.; Pei, W.; Wang, L.; Yu, J.; et al. Genome wide association study identifies candidate genes related to fatty acid components in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 183. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Xing, H.; Wang, Q.; Saeed, M.; Tao, J.; Feng, W.; Zhang, G.; Song, X.-L.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Candidate Genes Related to Seed Oil Composition and Protein Content in Gossypium hirsutum L.. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1359. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Mei, L.; Quampah, A.; He, Q.; Zhang, B.; Sun, W.; Zhang, X.; Shi, C.; Zhu, S. qOil-3, a major QTL identification for oil content in cottonseed across genomes and its candidate gene analysis. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 145. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fu, M.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jin, S. High-oleic acid content, nontransgenic allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) generated by knockout of GhFAD2 genes with CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 19, 424–426. [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.; Pei, W.; Wu, M.; Geng, Y.; Wang, N.; Liu, G.; Ma, J.; Li, D.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Genome-Scale Analysis of the WRI-Like Family in Gossypium and Functional Characterization of GhWRI1a Controlling Triacylglycerol Content. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1516. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Han, X.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Song, J.; Yu, H.; Liu, R.; Yang, L.; et al. Oil candidate genes in seeds of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) and functional validation of GhPXN1. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2023, 16, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jia, B.; Pei, W.; Wang, L.; Ma, J.; Wu, M.; Song, J.; Yang, S.; Xin, Y.; Huang, L.; et al. Quantitative Trait Locus Analysis and Identification of Candidate Genes Affecting Seed Size and Shape in an Interspecific Backcross Inbred Line Population of Gossypium hirsutum × Gossypium barbadense. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 837984. [CrossRef]

- Billings GT, Jones MA, Rustgi S, Bridges Jr WC, Holland JB, Hulse-Kemp AM, et al. Outlook for implementation of genomics-based selection in public cotton breeding programs. Plants. 2022;11(11):1446.

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Moncuquet, P.; Wilson, I.; Llewellyn, D.; Stiller, W.; Liu, S. Quantitative genomics-enabled selection for simultaneous improvement of lint yield and seed traits in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Yang, Y.; Guo, L.; Yuan, L.; Ma, W. Molecular Basis of Plant Oil Biosynthesis: Insights Gained From Studying the WRINKLED1 Transcription Factor. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 24. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Peng, Y.; Yin, S.; Zhao, H.; Zong, Z.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, W.; Guo, L. Transcriptional regulation of transcription factor genes WRI1 and LAFL during Brassica napus seed development. Plant Physiol. 2024, 197. [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.; Imran, M.; Rehman, T.; Intisar, A.; Lindsey, K.; Sarwar, G.; Qaisar, U. Seed-specific expression of AtWRI1 enhanced the yield of cotton seed oil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Dowd, M.K.; Pelitire, S.M.; Delhom, C.D. Seed-Fiber Ratio, Seed Index, And Seed Tissue and Compositional Properties Of Current Cotton Cultivars. J. Cotton Sci. 2018, 22, 60–74. [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew WT. Photosynthesis and carbon partitioning/source-sink relationships. FLOWERING AND FRUITING. 2012;25.

- Qin, A.; Aluko, O.O.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Hu, M.; Guan, L.; Sun, X. Improved cotton yield: Can we achieve this goal by regulating the coordination of source and sink?. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1136636. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Campbell, B.T.; Bechere, E.; Dever, J.K.; Zhang, J.; Jones, A.S.; Raper, T.B.; Hague, S.; Smith, W.; Myers, G.O.; et al. Genotypic and environmental effects on cottonseed oil, nitrogen, and gossypol contents in 18 years of regional high quality tests. Euphytica 2015, 206, 815–824. [CrossRef]

- Awais, H.M.; Arshad, S.F.; Nazeer, W.; Usman, M.; Tipu, A.L.K.; Ali, M.; Saleem, A.; Arshad, H.J.; Rukh, A.S. Correlation, Regression Analysis of Seed Oil Contents in Relation to Morphological Characters in Cotton. J. Bioresour. Manag. 2021, 8, 20–26. [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar K, Ravikesavan R. Genetic studies of correlation and path coefficient analysis for seed oil, yield and fibre quality traits in cotton (G. hirsutum L.). 2010.

- Mert, M.; Akişcan, Y.; Gençer, O. Genotypic and phenotypic relationships of lint yield, fibre properties and seed content in a cross of two cotton genotypes. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B — Soil Plant Sci. 2005, 55, 76–80. [CrossRef]

- Eldessouky, S.E.I.; El-Fesheikawy, A.B.A.; Baker, K.M.A. Genetic variability and association between oil and economic traits for some new Egyptian cotton genotypes. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Horn, P.J.; Neogi, P.; Tombokan, X.; Ghosh, S.; Campbell, B.T.; Chapman, K.D. Simultaneous Quantification of Oil and Protein in Cottonseed by Low-Field Time-Domain Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 1521–1529. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.; Chapman, K.; Sturtevant, D.; Kennedy, C.; Horn, P.; Chee, P.; Lubbers, E.; Meredith, W.; Johnson, J.; Fraser, D.; et al. Genetic Analysis of Cottonseed Protein and Oil in a Diverse Cotton Germplasm. Crop. Sci. 2016, 56, 2457–2464. [CrossRef]

- Pahlavani M, Miri A, Kazemi G. Response of oil and protein content to seed size in cotton. 2008.

- Patel J, Lubbers E, Kothari N, Koebernick J, Chee P. Genetics and genomics of cottonseed oil. Oil crop genomics: Springer; 2021. p. 53-74.

- Zhao, W.; Kong, X.; Yang, Y.; Nie, X.; Lin, Z. Association mapping seed kernel oil content in upland cotton using genome-wide SSRs and SNPs. Mol. Breed. 2019, 39, 105. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wu, Y.; Fu, S.; Huang, L.; Peng, J.; Kuang, M. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis reveals drivers of protein and oil variation in cottonseed. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2025, 11, 100270. [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhu, G.; Song, X.; Xu, H.; Li, W.; Ning, X.; Chen, Q.; Guo, W. Genome-wide association analysis reveals loci and candidate genes involved in fiber quality traits in sea island cotton (Gossypium barbadense). BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Tian, D.; Li, Y.; Aminu, I.M.; Tabusam, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, S. Characterization, Evolution, Expression and Functional Divergence of the DMP Gene Family in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10435. [CrossRef]

- Sheri, V.; Mohan, H.; Jogam, P.; Alok, A.; Rohela, G.K.; Zhang, B. CRISPR/Cas genome editing for cotton precision breeding: mechanisms, advances, and prospects. J. Cotton Res. 2025, 8, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Maeda AB, Dever JK, Maeda MM, Kelly CM. Breeding, genetics, and genomics cotton seed size-what is the" fuzz" all about? 2023.

- Shrestha A. Utilizing the potential of landraces as novel sources of genetic variation for the agronomic improvement of upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) 2025.

- Gong, J.; Kong, D.; Liu, C.; Li, P.; Liu, P.; Xiao, X.; Liu, R.; Lu, Q.; Shang, H.; Shi, Y.; et al. Multi-environment Evaluations Across Ecological Regions Reveal That the Kernel Oil Content of Cottonseed Is Equally Determined by Genotype and Environment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 2529–2544. [CrossRef]

- Kangben F, Parris S, Etukuri SP, Bridges W, Olvey J, Olvey M, et al., editors. Improving Oil Content for Upland Cotton Growers: New Molecular Tools and Germplasm. ASA, CSSA, SSSA International Annual Meeting; 2024: ASA-CSSA-SSSA.

- Li, J.; Yuan, D.; Wang, P.; Wang, Q.; Sun, M.; Liu, Z.; Si, H.; Xu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, B.; et al. Cotton pan-genome retrieves the lost sequences and genes during domestication and selection. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Ke, H.; Chen, B.; Liu, Z.; et al. High-quality genome assembly and resequencing of modern cotton cultivars provide resources for crop improvement. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1385–1391. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Xie, P.; Xu, Z.; Tang, J.; Hui, L.; Gu, J.; Gu, X.; Jiang, S.; Rong, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Pangenome analysis reveals yield- and fiber-related diversity and interspecific gene flow in Gossypium barbadense L.. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; You, C.; Nie, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Lin, Z. Genetic dissection of an allotetraploid interspecific CSSLs guides interspecific genetics and breeding in cotton. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wu, T.; Yang, Q.; Bai, Y.; et al. Mapping QTL for fiber- and seed-related traits in Gossypium tomentosum CSSLs with G. hirsutum background. J. Integr. Agric. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bu, S.; Wu, W.; Zhang, Y.-M. A Multi-Locus Association Model Framework for Nested Association Mapping With Discriminating QTL Effects in Various Subpopulations. Front. Genet. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Sallam, A.H.; Manan, F.; Bajgain, P.; Martin, M.; Szinyei, T.; Conley, E.; Brown-Guedira, G.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Anderson, J.A.; Steffenson, B.J. Genetic architecture of agronomic and quality traits in a nested association mapping population of spring wheat. Plant Genome 2020, 13, e20051. [CrossRef]

- Shockey, J.; Gilbert, M.K.; Thyssen, G.N. A mutant cotton fatty acid desaturase 2-1d allele causes protein mistargeting and altered seed oil composition. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Sreedasyam A, Lovell JT, Mamidi S, Khanal S, Jenkins JW, Plott C, et al. Genome resources for three modern cotton lines guide future breeding efforts. Nature Plants. 2024;10(6):1039-51.

- Chang, T.-G.; Zhu, X.-G. Source–sink interaction: a century old concept under the light of modern molecular systems biology. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 4417–4431. [CrossRef]

- Pabuayon, I.L.B.; Bicaldo, J.J.B.; Ritchie, G.L. Within-canopy carbon partitioning to cotton leaves in response to irrigation. Crop. Sci. 2024, 65. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Le, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Lin, Z. A global survey of the gene network and key genes for oil accumulation in cultivated tetraploid cottons. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 19, 1170–1182. [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Ma, X.; Xu, K.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Luo, L. Temporal transcriptomic differences between tolerant and susceptible genotypes contribute to rice drought tolerance. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 1–18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).