Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

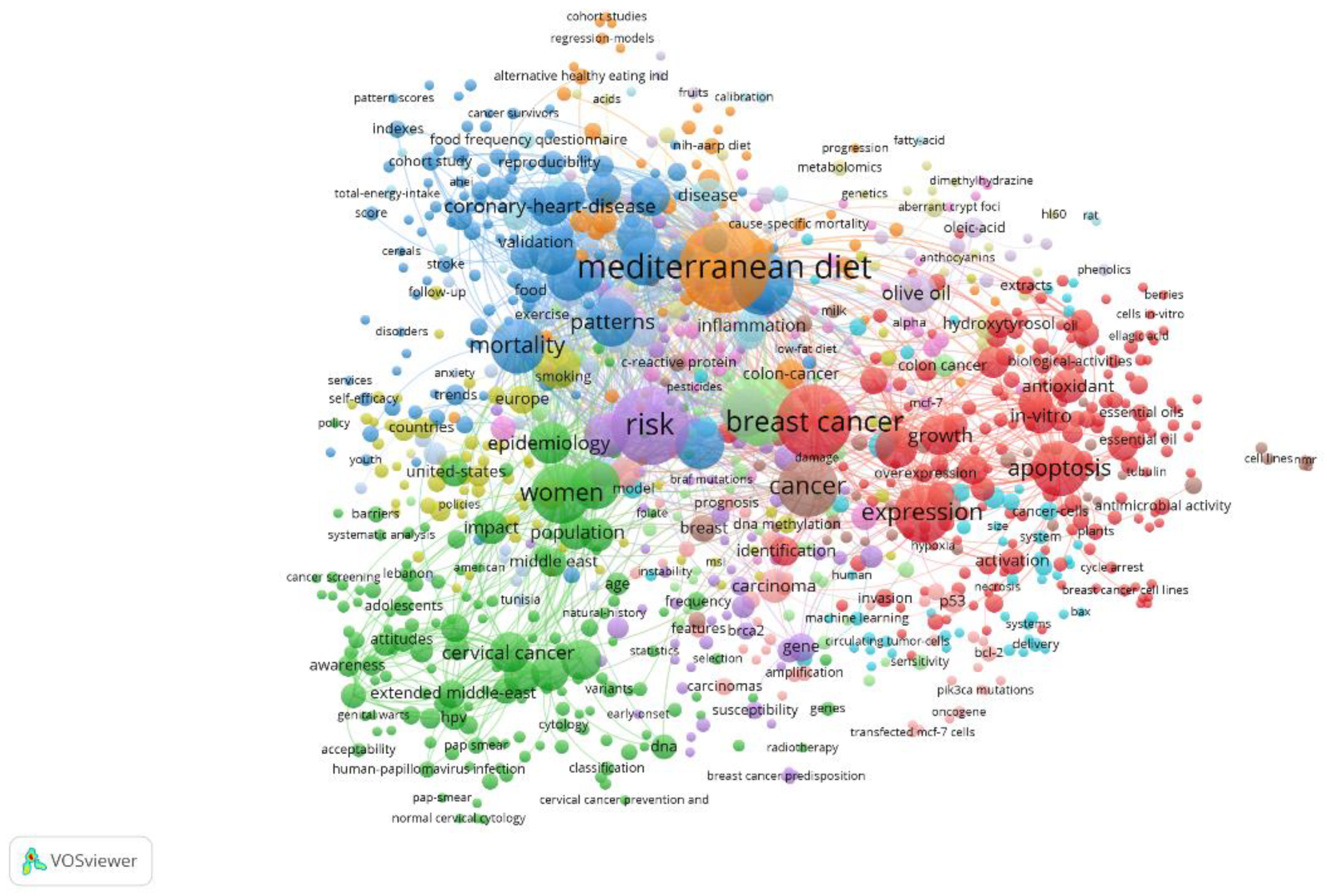

Keywords:

1. Introduction

The Importance of Early Detection and Prevention

2. HPV and Cervical Cancer in the MENA Population

Knowledge Gaps, Vaccine Introduction and Cost-Effectiveness Models

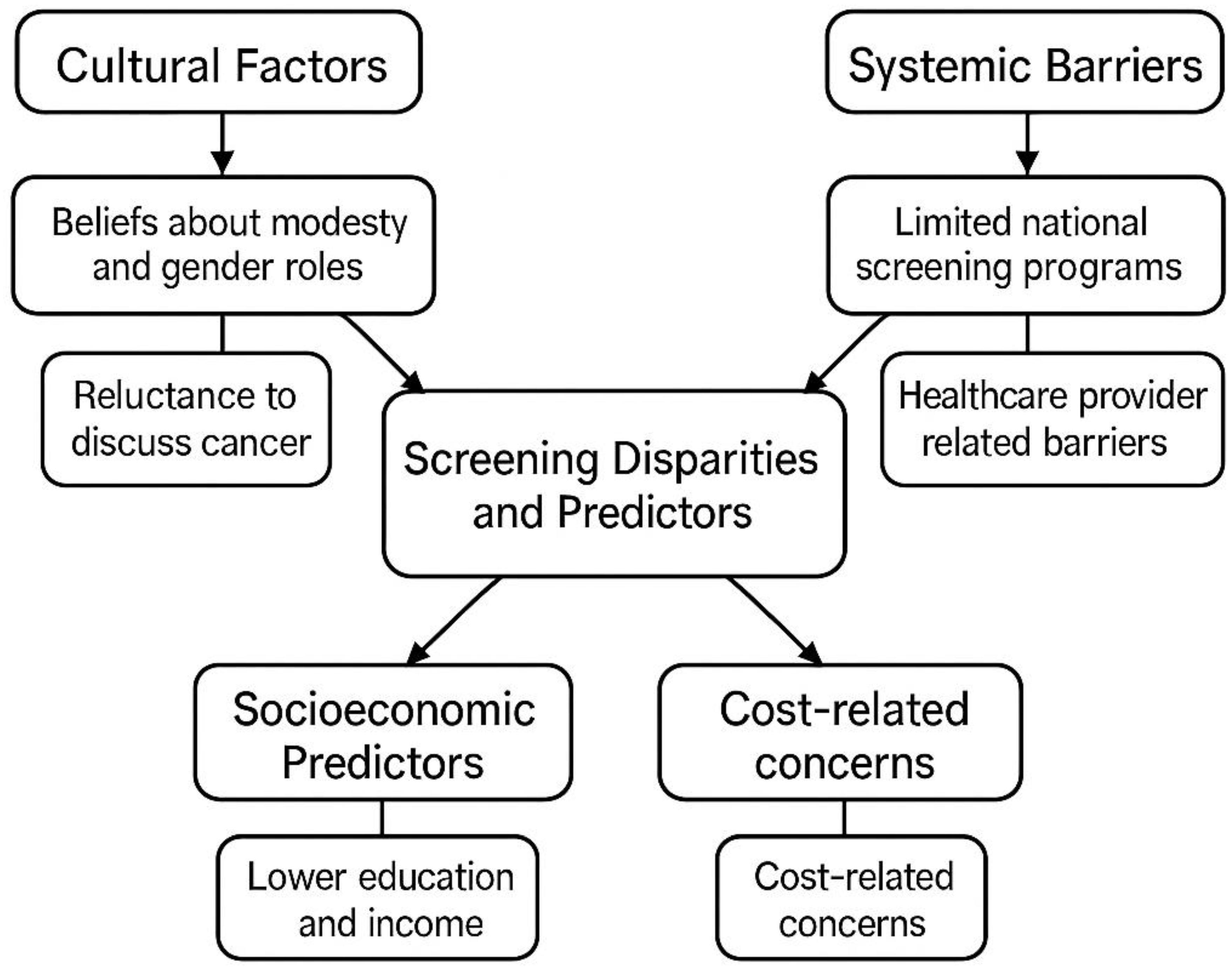

3. Disparities and Indicators in Screening

3.1. Cultural, Socioeconomic, and Systemic Influences

3.1.1. Cultural Elements

3.1.2. Socioeconomic Indicators

3.1.3. Barriers in the System

3.2. Immigrant vs. Native MENA Population

4. Culturally Adapted Interventions

4.1. Case Studies of Tailored Navigation and Education Programs

4.2. Health Literacy and Culturally Sensitive Education

4.3. Patient Navigation and Language Mediation

4.4. Peer Educator and Community-Led Models

4.5. Integration into Primary Care and Support at System Level

5. Challenges in the Implementation of Health Policy

5.1. Infrastructural and Systemic Gaps

5.2. Access to Healthcare and Equal Opportunities

5.3. Political Instability and Competing Health Priorities

6. Possibilities and Future Directions

6.1. AI-Supported Education, Digital Health Literacy and Policy Recommendations

6.2. AI-Powered Outreach and Risk Stratification

6.3. Digital Health Literacy and Mobile Health Interventions

6.4. Suggestions for Policies to Support Fair and Long-Term Growth

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding Information

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Competing Interest

AI Disclosure Statement

References

- Zahwe, M.; Bendahhou, K.; Eser, S.; Mukherji, D.; Fouad, H.; Fadhil, I.; Soerjomataram, I.; Znaor, A. Current and future burden of female breast cancer in the Middle East and North Africa region using estimates from GLOBOCAN 2022. International journal of cancer 2025, 156, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Morgan, E.; Rumgay, H.; Mafra, A.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Gralow, J.R.; Cardoso, F.; Siesling, S.; et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 2022, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, R.C.; Dempsey, A.F.; Patel, D.A.; Dalton, V.K. Cervical cancer prevention through human papillomavirus vaccination: using the “teachable moment” for educational interventions. Obstet Gynecol 2010, 115, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, S.C.; Al Yaquobi, S.; Al Hashmi, A. A Systematic Review of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Factors Influencing HPV Vaccine Acceptance Among Adolescents, Parents, Teachers, and Healthcare Professionals in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region. Cureus 2024, 16, e60293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseddine, A.; Chehade, L.; Al Mahmasani, L.; Charafeddine, M. Colorectal Cancer Screening in the Middle East: What, Why, Who, When, and How? American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting 2023, 43, e390520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balata, G.F.; Azzam, H.N. Synopsis of colorectal cancer: prevalence, symptoms, screening, staging, risk factors, and treatment. The Egyptian Journal of Internal Medicine 2025, 37, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, L.E.; Shulman, L.N. Breast Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Opportunities to Reduce Mortality. The oncologist 2016, 21, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorina, Y.; Elgaddal, N. Patterns of Mammography, Pap Smear, and Colorectal Cancer Screening Services Among Women Aged 45 and Over. Natl Health Stat Report 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chiumento, A.; Hosny, W.; Gaber, E.; Emadeldin, M.; El Barabry, W.; Hamoda, H.M.; Alonge, O. Exploring the acceptability of a WHO school-based mental health program in Egypt: A qualitative study. SSM-Ment. Health 2022, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigüzel, F.I.; Adigüzel, C.; Seyfettinoglu, S.; Hürriyetoglu, S.; Kazgan, H.; Yilmaz, E.S.S.; Yücel, O.; Baser, E. HPV awareness and HPV vaccine acceptance among women who apply to the gynecology outpatient clinics at a tertiary referral hospital in the south Mediterranean region of Turkey. Med. J. Bakirkoy 2016, 12, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Amat, M.; López-Abente, G.; Aragonés, N.; Pollán, M.; Pastor-Barriuso, R.; Pérez-Gómez, B. The end of the decline in cervical cancer mortality in Spain: trends across the period 1981-2012. BMC cancer 2015, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansori, K.; Khazaei, S.; Khosravi Shadmani, F.; Hanis, S.M.; Jenabi, E.; Soheylizad, M.; Sani, M.; Ayubi, E. Global Inequalities in Cervical Cancer Incidence and Mortality. Middle East J. Cancer 2018, 9, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.X.; Zeng, Q.L.; Cai, W.W.; Ruan, W.Q. Trends of cervical cancer at global, regional, and national level: data from the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Bmc Public Health 2021, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, R.M.; Noel, K.; Reed, R.N.; Sibel, J.; Smith, H.J. Health Promotion, Health Protection, and Disease Prevention: Challenges and Opportunities in a Dynamic Landscape. AJPM Focus 2024, 3, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Awadhi, R.; Chehadeh, W.; Jaragh, M.; Al-Shaheen, A.; Sharma, P.; Kapila, K. Distribution of human papillomavirus among women with abnormal cervical cytology in Kuwait. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2013, 41, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddal, B.; Oktay, M.N.; Bostanci, A.; Yenen, M.C. Prevalence and genotype screening of human papillomavirus among women attending a private hospital in Northern Cyprus: an 11-year retrospective study. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dom-Chima, N.; Ajang, Y.A.; Dom-Chima, C.I.; Biswas-Fiss, E.; Aminu, M.; Biswas, S.B. Human papillomavirus spectrum of HPV-infected women in Nigeria: an analysis by next-generation sequencing and type-specific PCR. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, A.A.; Bansal, D.; Acharya, A.; Skariah, S.; Dargham, S.R.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Mohamed-Nady, N.; Amuna, P.; Al-Thani, A.A.J.; Sultan, A.A. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection: Molecular Epidemiology, Genotyping, Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors among Arab Women in Qatar. PloS one 2017, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayash, C.; Raad, N.; Finik, J.; Attia, N.; Nourredine, S.; Aragones, A.; Gany, F. Arab American Mothers’ HPV Vaccination Knowledge and Beliefs. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finan, R.R.; Chemaitelly, H.; Racoubian, E.; Aimagambetova, G.; Almawi, W.Y. Genetic diversity of human papillomavirus (HPV) as specified by the detection method, gender, and year of sampling: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 307, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolet, M.; Laprise, J.-F.; Boily, M.-C.; Franco, E.; Brisson, M. Potential cost-effectiveness of the nonavalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 2014, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, G.D.; Taira, A.V. Cost-effectiveness of a potential vaccine for human papillomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis 2003, 9, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbo, E.L.S.; Hanson, C.; Abunnaja, K.S.S.; van Wees, S.H. Do peer-based education interventions effectively improve vaccination acceptance? a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, A.C.; Balbino, J.E.; Lemgruber, A.; Ruiz, E.M.; Lima, A.O.D.; Mochón, L.G.; Lessa, F. Adoption of the HPV vaccine: a case study of three emerging countries. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2017, 6, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennacef, A.C.; Khodja, A.A.; Abou-Bekr, F.A.; Ndao, T.; Holl, R.; Bencina, G. Costs and Resource Use Among Patients with Cervical Cancer, Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia, and Genital Warts in Algeria. J. Health Econ. Outcome. Res. 2022, 9, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencina, G.; Ugrekhelidze, D.; Shoel, H.; Oliver, E.; Meiwald, A.; Hughes, R.; Eiden, A.; Weston, G. The indirect costs of vaccine-preventable cancer mortality in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). J. Med. Econ. 2024, 27, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Abraham, A.; Maisonneuve, P.; Jithesh, A.; Chaabna, K.; al Janahi, R.; Sarker, S.; Hussain, A.; Rao, S.; Lowenfels, A.B.; et al. HPV infection and vaccination: a cross-sectional study of knowledge, perception, and attitude to vaccine uptake among university students in Qatar. Bmc Public Health 2024, 24, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.; Al Eid, M.M.A.; Mohamed, M.A.; Aladwani, A.J.; El Amin, N. Human papillomavirus vaccination and Pap test uptake, awareness, and barriers among young adults in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: A comparative cross-sectional survey. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierz, A.J.; Randall, T.C.; Castle, P.E.; Adedimeji, A.; Ingabire, C.; Kubwimana, G.; Uwinkindi, F.; Hagenimana, M.; Businge, L.; Musabyimana, F.; et al. A scoping review: Facilitators and barriers of cervical cancer screening and early diagnosis of breast cancer in Sub-Saharan African health settings. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2020, 33, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsah, Y.R.; Kaneko, N. Barriers to cervical cancer screening faced by immigrant Muslim women: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Sharma, M.; O’Shea, M.; Sweet, S.; Diaz, M.; Sancho-Garnier, H.; Seoud, M. Model-Based Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Cervical Cancer Prevention in the Extended Middle East and North Africa (EMENA). Vaccine 2013, 31, G65–G77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, N.V.; Schumacher, A.E.; Aali, A.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbasgholizadeh, R.; Abbasian, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; et al. Global fertility in 204 countries and territories, 1950-2021, with forecasts to 2100: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2057–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf, S.M.; Ahmed, S.; Mulvey, M.; Bennett, M.I. Attitudes, Knowledge, and Perceived Barriers Towards Cancer Pain Management Among Healthcare Professionals in Libya: a National Multicenter Survey. J Cancer Educ 2023, 38, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soled, D. Language and Cultural Discordance: Barriers to Improved Patient Care and Understanding. J Patient Exp 2020, 7, 830–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamou, C.; Rodrigue-Moulinie, C.; Rahmani, S.; de Jesus, M. Optimizing cancer screening rates in populations with low literacy in France: Results of a mixed-methods cancer educational intervention study. Cancer Research, Statistics, and Treatment 2023, 6, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de jesus, M.; Rodrigue, C.; Rahmani, S.; Balamou, C. Addressing Cancer Screening Inequities by Promoting Cancer Prevention Knowledge, Awareness, Self-Efficacy, and Screening Uptake Among Low-Income and Illiterate Immigrant Women in France. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Gama, A.; Fronteira, I.; Marques, P.; Dias, S. Knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer and screening among migrant women: a qualitative study in Portugal. BMJ open 2024, 14, e082538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdiui, N.; Stein, M.L.; van Steenbergen, J.; Crutzen, R.; Bouman, M.; Khan, A.; Çetin, M.N.; Timen, A.; van den Muijsenbergh, M. Evaluation of a Web-Based Culturally Sensitive Educational Video to Facilitate Informed Cervical Cancer Screening Decisions Among Turkish- and Moroccan-Dutch Women Aged 30 to 60 Years: Randomized Intervention Study. Journal of medical Internet research 2022, 24, e35962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comparetto, C.; Epifani, C.; Manca, M.C.; Lachheb, A.; Bravi, S.; Cipriani, F.; Bellomo, F.; Olivieri, S.; Fiaschi, C.; Marco, L.; et al. Uptake of cervical cancer screening among the migrant population of Prato Province, Italy. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2016, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travier, N.; Vidal, C.; Garcia, M.; Benito, L.; Medina, P.; Moreno, V. Communication Channels Used by Women to Contact a Population-Based Breast Cancer Screening Program in Catalonia, Spain. J Med Syst 2019, 43, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo-Rodrigues, I.; Jiménez-García, R.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Carrasco-Garrido, P.; Jiménez-Trujillo, I.; López de Andrés, A. Social disparities in access to breast and cervical cancer screening by women living in Spain. Public Health 2015, 129, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piana, A.; Sotgiu, G.; Castiglia, P.; Pischedda, S.; Cocuzza, C.; Capobianco, G.; Marras, V.; Dessole, S.; Muresu, E. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus infection in women from North Sardinia, Italy. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sande, C.M.; Yang, G.; Mohamed, A.; Legendre, B.L.; Pion, D.; Ferro, S.L.; Grimm, K.; Elenitoba-Johnson, K.S.J. High-resolution melting assay for rapid, simultaneous detection of JAK2, MPL and CALR variants. Journal of clinical pathology 2024, 77, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, M.A.; Lamouroux, A.; Redmond, N.M.; Rotily, M.; Bourmaud, A.; Schott, A.M.; Auger-Aubin, I.; Frachon, A.; Exbrayat, C.; Balamou, C.; et al. Impact of a health literacy intervention combining general practitioner training and a consumer facing intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening in underserved areas: protocol for a multicentric cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kale, S.; Hirani, S.; Vardhan, S.; Mishra, A.; Ghode, D.B.; Prasad, R.; Wanjari, M. Addressing Cancer Disparities Through Community Engagement: Lessons and Best Practices. Cureus 2023, 15, e43445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priaulx, J.; Turnbull, E.; Heijnsdijk, E.; Csanadi, M.; Senore, C.; Koning, H.; McKee, M. The influence of health systems on breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening: an overview of systematic reviews using health systems and implementation research frameworks. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 2019, 25, 135581961984231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, L.; Ahmed, H.; Hamze, M.; Ali, A.A.; Alahdab, F.; Marzouk, M.; Sullivan, R.; Abbara, A. Cancer and Syria in conflict: a systematic review. BMC cancer 2024, 24, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, M.N.; Hefnawy, A.; Azzam, H.; Reisha, O.; Hamdy, O. Knowledge and attitude among Egyptian medical students regarding the role of human papillomavirus vaccine in prevention of oropharyngeal cancer: a questionnaire-based observational study. Scientific reports 2025, 15, 3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaafar, I.; Atallah, D.; Mirza, F.; Abu Musa, A.; El-Kak, F.; Seoud, M. Determinants of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine recommendation among Middle Eastern and Lebanese Healthcare Providers. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 2022, 17, 101092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, H.M.; Rahman, H.A.; Naing, L.; Malik, O.A. Artificial intelligence utilization in cancer screening program across ASEAN: a scoping review. BMC cancer 2025, 25, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisemann, N.; Bunk, S.; Mukama, T.; Baltus, H.; Elsner, S.A.; Gomille, T.; Hecht, G.; Heywang-Köbrunner, S.; Rathmann, R.; Siegmann-Luz, K.; et al. Nationwide real-world implementation of AI for cancer detection in population-based mammography screening. Nature medicine 2025, 31, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.R.; Egemen, D.; Befano, B.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Jeronimo, J.; Desai, K.; Teran, C.; Alfaro, K.; Fokom-Domgue, J.; Charoenkwan, K.; et al. Assessing generalizability of an AI-based visual test for cervical cancer screening. PLOS Digital Health 2024, 3, e0000364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adapa, K.; Gupta, A.; Singh, S.; Kaur, H.; Trikha, A.; Sharma, A.; Rahul, K. A real world evaluation of an innovative artificial intelligence tool for population-level breast cancer screening. NPJ digital medicine 2025, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).