1. Introduction

Cervical cancer is cancer affecting the cervix, an organ that connects the uterus and the vagina in women [

1]. Globally, Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women, with around 660 000 incident cases and fatalities amounting to 350,000 in 2022 and accounts for 22% of all cancers in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [

2,

3,

4] . It is the most common gynecological cancer worldwide with the low- and middle-income countries bearing a disproportionate disease burden as a result of wide inequalities in human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination exposure, socioeconomic factors and access to preventive strategies [

5]. Although cervical cancer is basically preventable through effective interventions, most women seek help late when the disease has reached an advanced stage and irreparable eventually leading to death [

6,

7,

8].

Global analysis from 185 countries found that the highest incidences were in Eastern, Western, and Southern African countries. It further revealed that except for Northern Africa, cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in women in the African region [

9,

10]. According to global mortality statistics, Africa bears the greatest burden, with 24.55% mortality rate [

10] In SSA, incident and mortality rates of cervical cancer is 35 and 22.5 per 100,000 women annually as compared to a lower figure of 6.6 and 2.5 per 100,000 women, respectively, in North America [

11]. In SSA, 66% of cervical cancers are diagnosed at an advanced stage as compared to 25% in the UK, thus giving an insight into the disparity in age standardised relative survival (ASRS) between SSA and high-income countries (HICs) [

12]. The incidence and mortality rates of cervical cancer in South Africa are among the highest in SSA. Of the 117,316 incident cases and 76,745 fatalities recorded within the African region in 2020, 10,702 cases and 5,870 associated deaths were reported from South Africa alone [

13]. In contrast, a total of 4,664 deaths due to female breast cancer were recorded in that same year, making cervical cancer the leading cause of cancer-related death among women in South Africa [

13] A study by the South African Medical Research Council reported cervical cancer as the most common cancer among females in the Eastern Cape, with a prevalence of 35% [

14].

The etiology of cervical cancer is chronic human papillomavirus (HPV). Different types of HPV have been identified including a dozen of them linked with cervical cancer development infection with 70% of cases associated with HPV16 and 18 [

4,

10,

15]. Although HPV infection leads to cervical cancer, other risk factors include HIV infection, oral contraceptives, early sexual escapades, multiple sexual associates, compromised immune system and smoking [

4,

10,

16]. Despite the magnitude of the disease, awareness is generally low globally but a worse situation in LMICs [

16]. Evidence suggests that increased awareness of signs, symptoms and risk factors of cervical cancer leads to increased uptake of cervical screening, early detection and subsequently leading to timely help-seeking behaviour and prevention [

17]. Being asymptomatic in its early stages coupled with a long latent phase, screening is a highly essential preventative measure which detects precancerous cell changes on the cervical lining before progression to invasive cancer, thus reducing the burden of disease [

5,

15]. Although cytology-based pap smear remains the gold standard for screening to identify precursors, other methods include colposcopy and HPV-DNA testing as an alternative screening method is allowed according to the 2017 South African guidelines [

5,

15,

16]. Screening using pap smear 3–5 years with appropriate follow-up can lead to the reduced risk of cervical cancer by 80% [

3,

18].

In 2020, the World Health Organization launched a global initiative aimed at accelerating eradication of cervical cancer. The 2030 targets of 90–70–90 aim that by age 15, 90% of girls would have been vaccinated with HPV vaccine, within ages 35 and 45, 70% of women would have been screened and 90 % of women with precancerous lesions or invasive cancer would have been treated [

4,

5].

Different factors such as awareness of cervical cancer, level of education and cultural and religious beliefs influence women’s uptake of screening programs and services in developing nations. Culture and beliefs influence a person’s knowledge and perception of cancer screening, contributing to low participation in cervical screening programs and a crucial predictor of health-seeking behavior [

3,

6]. Cultural diversity and socio-economic factors are attitudinal barriers to women’s access to cervical screening services [

19]. Attitudes play an important role in formulating health-seeking behavior. A negative attitude is associated with low uptake of screening services for the prevention and treatment of cervical cancer among women in sub-Saharan Africa [

19]. Hence the study sought to assess knowledge, attitudes, and cultural beliefs regarding cervical cancer screening among women attending primary healthcare centers in a rural community in the Eastern Cape.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design, Setting and Population

This was a community-based descriptive cross-sectional study conducted at Lutubeni Clinic, a primary healthcare facility in the rural community of Mqanduli, Oliver Tambo District, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. The clinic serves residents of Lutubeni and neighboring villages, including Mampingeni, Mandqobe, Gomatana, Haji, Khawula, and Mbozisa. The target population included women aged 25 years and older who had resided in Lutubeni for at least one year. The study population comprised female clients who attended the clinic during the data collection period. A convenience sampling technique was employed to recruit eligible participants based on their availability and willingness to participate. Females aged ≥25 year, Residents of Lutubeni for ≥1 year were included in the recruitment while Male, Critically ill participants and individuals unwilling or unable to provide consent were excluded from the study.

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated using the formula: n= Z

2α * p(1-p) / e2. Where

Z = 1.96 for a 95% confidence interval,

p = 0.355 (estimated cervical screening prevalence in South Africa) [

1], and

e = 0.10 (margin of error). The estimated sample was 88 participants; accounting for a 15% non-response rate, the final target was 102 participants.

2.3. Data Collection, Management and Analysis

Data were collected over four weeks (5–26 October 2022) using a validated structured questionnaire comprising five sections: (A) sociodemographic characteristics, (B) reproductive and lifestyle factors, (C) knowledge about cervical cancer and screening, (D) attitudes toward screening, and (E) cultural beliefs. The instrument was developed from previously published studies [

2,

3]translated into isiXhosa, and back-translated into English for accuracy. Data collection was conducted by nine trained medical students from Walter Sisulu University during Community-Based Education and Service (COBES) rotations.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were summarized as means ± standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), depending on data distribution. Categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages. Associations between sociodemographic, knowledge, and attitude variables and screening practice were tested using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Statistically significant variables (p < 0.05) were entered into a multinomial logistic regression model to identify independent predictors of screening practice. Knowledge Scoring: Correct answers received 1 point; incorrect answers received 0. Composite knowledge scores were calculated and categorized using Modified Bloom’s criteria: good (80–100%), moderate (50–79%), and poor (<50%). Attitude Scoring: Attitudes were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale. Total scores were calculated, and participants were dichotomized into positive (<mean score) and negative (≥mean score) attitude categories. Screening Practice: Defined as “good” if participants had ever undergone cervical cancer screening; otherwise, “poor.”

3. Results

A total of 98 women aged 25 years and older participated in the study, yielding a response rate of 96.1%. After excluding three questionnaires due to missing critical data (age and cervical screening status), the final sample comprised 95 participants, which exceeded the minimum required sample size (n = 88). Only marital status had incomplete responses (n = 4 missing).

The results presented below include analyses of participants’ sociodemographic, reproductive, and lifestyle characteristics, along with their knowledge, attitudes, and cultural beliefs regarding cervical cancer and screening. Factors influencing cervical cancer screening practices among women in Lutubeni were also assessed.

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Population

The study sample comprised 95 women aged 25–68 years (median: 39; IQR: 30–48), with the largest proportion (43.2%) aged 25–35 years. The majority self-identified as Christian (94.7%), while smaller proportions reported African spirituality (3.2%) or Zionist beliefs (2.1%). Most participants were either single (42.1%) or married (41.1%). Educational levels varied, with 42.1% having completed secondary education, and 11.6% possessing diploma or degree qualifications. Unemployment was prevalent (30.5%), alongside notable proportions of housewives (26.3%) and government employees (25.3%). Monthly income was predominantly below 2000 Rands(South Africa currency), (60%), and nearly all respondents (98.9%) identified as heterosexual.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample population.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample population.

| Variable |

Category |

Frequency (n=95) |

Percentage (%) |

| Age groups |

25-35 years |

41 |

43.2 |

| 36-46 years |

25 |

26.3 |

| 47-57 years |

18 |

18.9 |

| 58-68 years |

11 |

11.6 |

|

Median (IQR): 39 (30 – 48) years; Min-Max: 25 – 68 years |

| Religion |

Christianity |

90 |

94.7 |

| African spirituality |

3 |

3.2 |

| Zion |

2 |

2.1 |

| Marital status |

Single |

40 |

42.1 |

| Married |

39 |

41.1 |

| Widowed |

6 |

6.3 |

| Divorced |

3 |

3.2 |

| Cohabitation |

2 |

2.1 |

| Separated |

1 |

1.1 |

| Decline |

4 |

4.2 |

| Education Status |

Secondary school |

40 |

42.1 |

| Diploma |

16 |

16.8 |

| Primary school |

16 |

16.8 |

| No formal education |

12 |

12.6 |

| Diploma/Degree |

8 |

8.4 |

| Degree |

3 |

3.2 |

| Occupation |

Unemployed |

29 |

30.5 |

| House wife |

25 |

26.3 |

| Government |

24 |

25.3 |

| Self-employed |

11 |

11.6 |

| Student |

6 |

6.3 |

| Monthly Income |

R <2000 |

57 |

60.0 |

| R >2000 |

34 |

35.8 |

| Sexual Orientation |

Heterosexual |

94 |

98.9 |

| Homosexual |

1 |

1.1 |

3.2. Reproductive Characteristics of 95 Women Residing in Lutubeni

The reproductive characteristics of 95 women residing in Lutubeni revealed that almost all participants (98.9%) had previously engaged in sexual activity, with the median age at sexual debut being 18 years (IQR: 16–21; range: 10–30 years). Over half (51.6%) reported initiating sexual activity between ages 15 and 18, while 7.4% reported initiation before age 15. A history of casual sexual partnerships was reported by 45.3% of participants, whereas 53.7% reported having only steady partners. Modern contraceptive use was high (78.9%), with a median usage duration of 7 years (IQR: 5–10). The majority (40.0%) had used contraceptives for 5–9 years, 21.1% for ≥10 years, and 16.8% for less than 5 years. Only 2.1% reported a maternal history of cervical cancer. Condom use was reported by 75.8% of participants. A small proportion (12.6%) were current cigarette smokers, and 46.3% reported alcohol consumption.

Table 2.

Reproductive characteristics of 95 women residing in Lutubeni.

Table 2.

Reproductive characteristics of 95 women residing in Lutubeni.

| Variable |

Category |

Frequency (n=95) |

Percentage (%) |

| Ever had Sex |

Yes |

94 |

98.9 |

| No |

1 |

1.1 |

| Age of First Sex (Years) |

15-18 years |

49 |

51.6 |

| >18 years |

37 |

38.9 |

| <15 years |

7 |

7.4 |

| |

Median (IQR):18 (16-21) years; Min-Max: 10-30 years |

| History of Casual Sex |

No |

51 |

53.7 |

| Yes |

43 |

45.3 |

| Never had sex |

1 |

1.1 |

| Use of Contraceptive pills or injection |

Yes |

75 |

78.9 |

| No |

19 |

20.0 |

| Never had sex |

1 |

1.1 |

| Duration of Using Oral Contraceptives |

5-9 years |

38 |

40.0 |

| ≥10 years |

20 |

21.1 |

| <5 years |

16 |

16.8 |

| |

Median (IQR): 7 (5-10) years; Min-Max: 1-20 years) |

| My mother had cervical cancer |

No |

93 |

97.9 |

| Yes |

2 |

2.1 |

| History of Condom |

Yes |

72 |

75.8 |

| No |

22 |

23.2 |

| Never had sex |

1 |

1.1 |

| History of Cigarette Smoking |

No |

83 |

87.4 |

| Yes |

12 |

12.6 |

| History of Alcohol Consumption |

No |

51 |

53.7 |

| Yes |

44 |

46.3 |

3.3. Knowledge Level About Cervical Cancer and Screening Among the Participants.

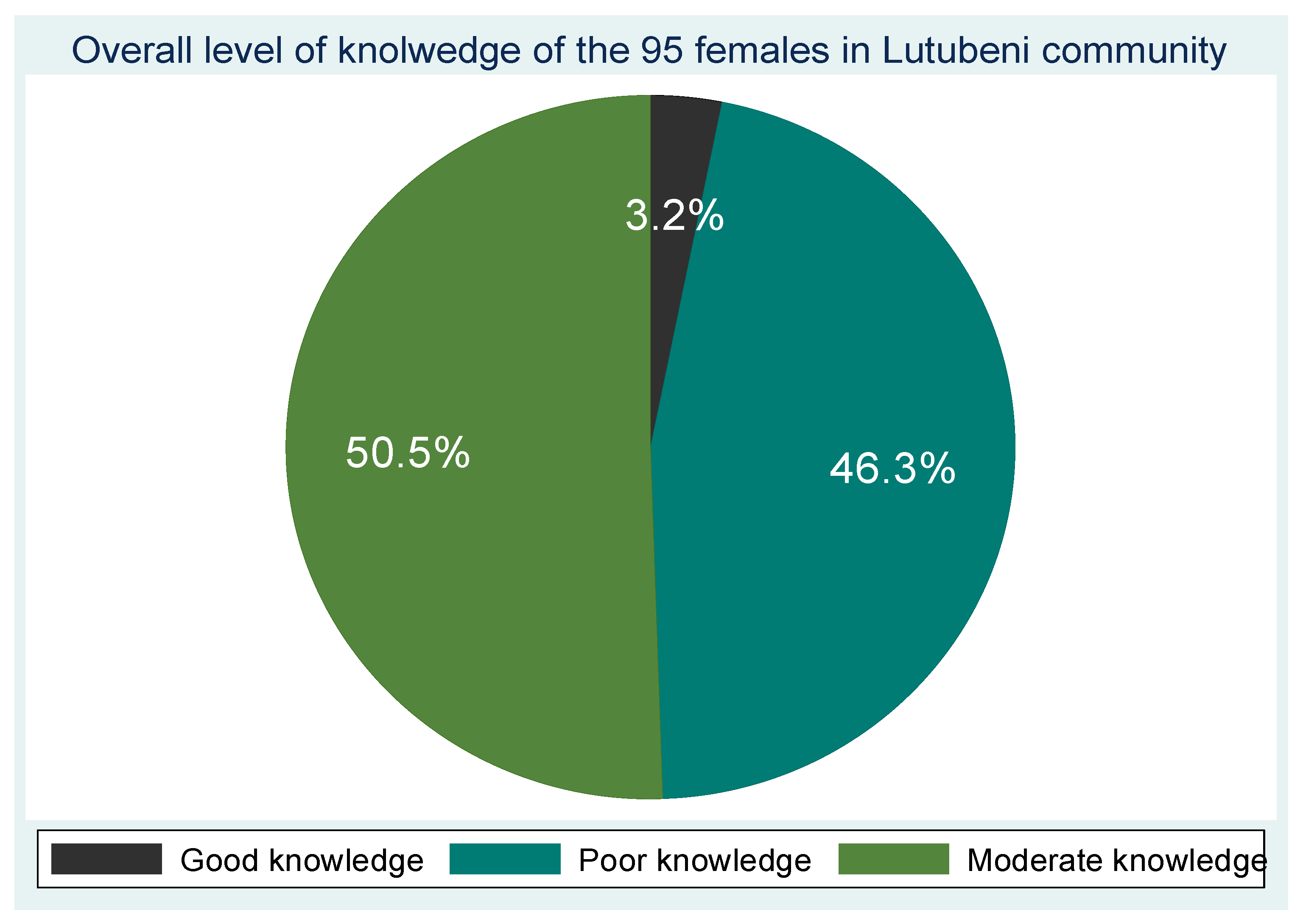

Out of the 95 participants, the majority demonstrated poor knowledge of cervical cancer symptoms (47.4%) and risk factors (61.1%). 24.2% reported good knowledge of symptoms with vaginal bleeding (60%) and foul-smelling vaginal discharge (50.5%) being the most recognized symptoms, while pain during intercourse was less commonly identified (45.3%),47.4% acknowledged multiple sexual partners as a risk, fewer participants recognized associations with HPV infection (24.2%), multiparity (27.4%), early sexual debut (30.5%), long-term oral contraceptive use (31.6%), or cigarette smoking (41.1%). 32.6% reported having no knowledge of any risk factors while 54.7% had poor knowledge and only 40% were aware of HPV vaccination as a preventive measure. Avoidance of multiple sexual partners was (64.2%), early screening (68.4%) was more commonly known preventive strategies and 14.7% reported no knowledge of prevention methods. Awareness of cervical cancer screening was 87.4% demonstrating good knowledge and 90.5% acknowledging the existence of screening programs. Overall, the composite knowledge score revealed that 46.3% of participants had poor knowledge, 50.5% had moderate knowledge, and only 3.2% demonstrated good knowledge regarding cervical cancer and its screening.

Table 3.

Knowledge level about cervical cancer and screening.

Table 3.

Knowledge level about cervical cancer and screening.

Knowledge of Cervical cancer |

Response n (%), n=95 |

| Yes |

|

No |

|

|

Knowledge of symptoms of cervical cancer: Poor knowledge 45 (47.4%), Moderate knowledge 27 (28.4%), Good knowledge 23 (24.2%) |

| Vaginal bleeding |

57 (60%) |

38 (40%) |

| Vaginal foul-smelling discharges |

48 (50.5%) |

47 (47.9%) |

| Pain during sex |

43 (45.35) |

52 (54.7%) |

|

Knowledge related to the risk factor of Cervical cancer: Poor knowledge 58 (61.1%), Moderate knowledge 26 (27.4%), Good knowledge 11 (11.6%) |

| Acquiring HPV |

23 (24.2%) |

72 (75. 8%) |

| Multiple sex partner |

45 (47.4%) |

50 (52.6%) |

| Multi parity |

26 (27.4%) |

69 (72.6%) |

| Early sexual intercourse |

29 (30.5%) |

66 (69.5%) |

| Long-term oral contraceptive use |

30 (31.6%) |

65 (68.4%) |

| Cigarette smoking |

39 (41.1%) |

56 (58.9%) |

| Do not know the risk factors |

31 (32.6%) |

64 (67.4%) |

|

Knowledge related to prevention: Poor knowledge 52 (54.7%), Moderate knowledge 4 (4.2%), Good knowledge 39 (41.1%) |

| Vaccination for HPV |

38 (40%) |

57 (60%) |

| Avoid multiple sex partner |

61 (64.2%) |

34 (35. 8%) |

| Avoid long-term use of oral contraceptives |

40 (42.1%) |

55 (57.9%) |

| Early screening |

65 (68.4%) |

30 (31.6%) |

| No smoking |

44 (46.3%) |

51 (53.7%) |

| Do not know the prevention |

14 (14.7%) |

81 (85.3%) |

|

Knowledge related to the treatment of cervical cancer: Poor knowledge 42 (44.2%), Moderate knowledge 41 (43.2%), Good knowledge 12 (12.6%) |

| Surgery |

68 (71.6%) |

27 (28.4%) |

| Chemotherapy |

57 (60%) |

38 (40%) |

| Radiotherapy |

15 (15. 8%) |

80 (84.2%) |

| Do not know |

20 (21.1%) |

75 (78.9%) |

|

Knowledge of cervical cancer screening: Poor knowledge 8 (8.4%), Moderate knowledge 4 (4.2%), Good knowledge 83 (87.4%) |

| Is there screening for cervical cancer |

86 (90.5%) |

9 (9.5%) |

| Screening service is available at the local clinic |

84 (88.4%) |

11 (11.6%) |

|

Knowledge related to screening interval: Poor knowledge 66 (69.5%), Moderate knowledge 27 (28.4%), Good knowledge 2 (2.1%) |

| Every year |

31 (32.6%) |

64 (67.4%) |

| Every three years |

22 (23.2%) |

73 (76.8%) |

| Every five year |

12 (12.6%) |

83 (87.4%) |

| Do not know |

28 (29.5%) |

67 (70.5%) |

|

Knowledge related to screening eligibility: Poor knowledge 48 (50.5%), Moderate knowledge 28 (29.5%), Good knowledge 19 (20.0%) |

| Women 30 years of age and older |

58 (61.1%) |

37 (38.9%) |

| Prostitute |

47 (45.5%) |

48 (50.5%) |

| Elderly women |

44 (46.3%) |

51 (53.7%) |

| Do not know |

21 (22.1%) |

74 (77.9%) |

| Knowledge related to cervical cancer screening procedures |

| VIA |

1 (1.1%) |

94 (98.9%) |

| PAP smear |

84 (88.4%) |

11 (11.6%) |

| Do not know |

11 (11.6%) |

84 (88.4%) |

| Composite Knowledge score |

| Poor Knowledge |

44 (46.3%) |

| Good knowledge |

3 (3.2%) |

| Moderate knowledge |

48 (50.5%) |

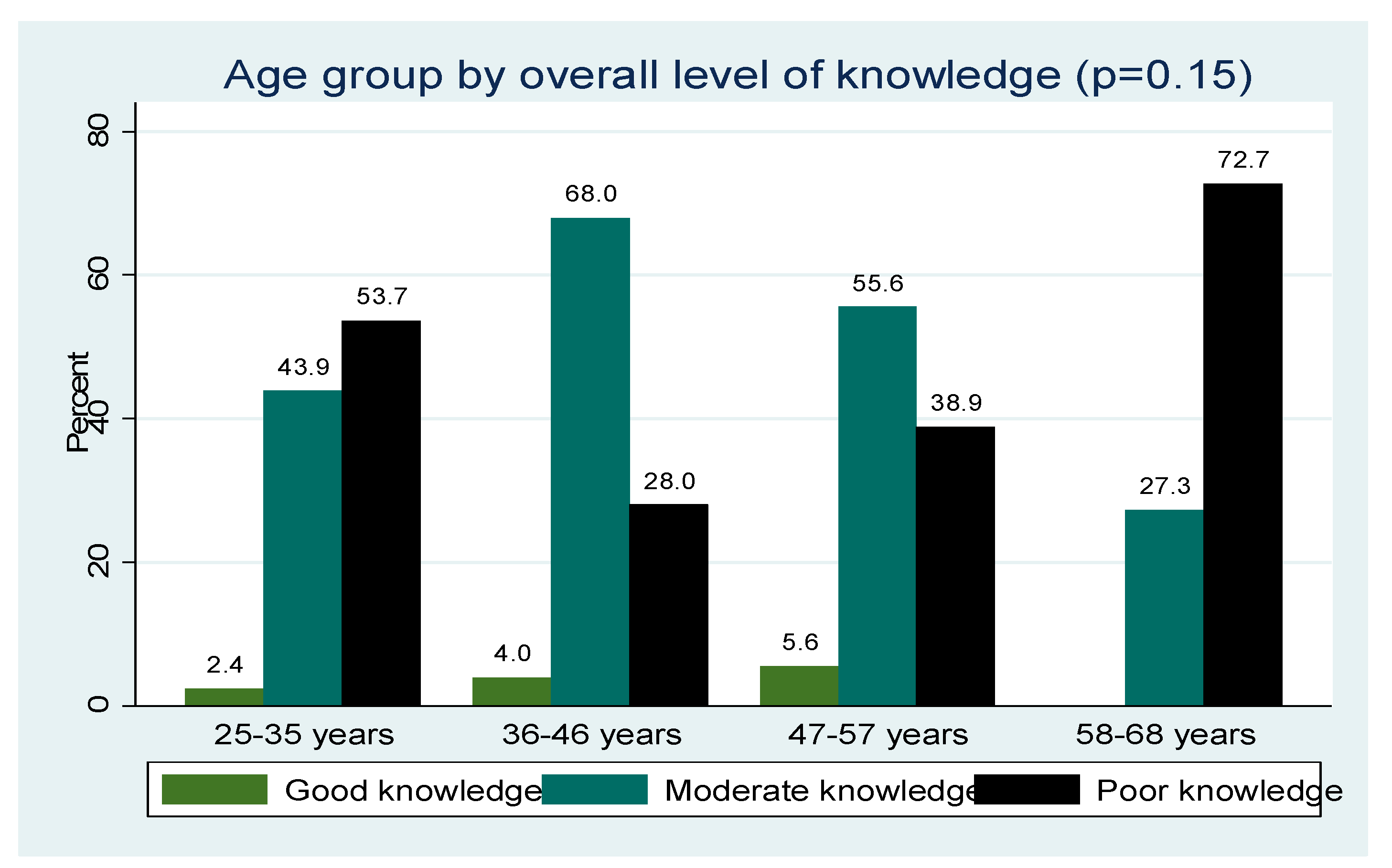

3.4. Overall Knowledge Level and Age Group of the 95 Participants from the Lutubeni Community.

Poor knowledge was highest among participants between 58 years and 68 years, moderate among those of the age group 36 years to 46 years, and good knowledge among the 47 years to 57 years age group.

Figure 1.

Overall knowledge level of the 95 participants from the Lutubeni community.

Figure 1.

Overall knowledge level of the 95 participants from the Lutubeni community.

Figure 2.

Age group by overall level of knowledge.

Figure 2.

Age group by overall level of knowledge.

3.5. Attitude of the Participants Towards Cervical Cancer Screening

Analysis of the participants’ attitudes is presented in

Table 4. From all the participants, more than two-third (67.4% ) strongly agreed that cervical cancer is becoming a problem in south Africa and 38 (40.0%) of them agreed that it is the leading cause of cancer-related death among women in South Africa. The majority agreed that any adult woman can acquire cervical cancer (43.2% ) and that cervical cancer cannot be transmitted from one person to another (46.3% n=44). Most (50.5% ) of them agreed that screening helps in the prevention of cervical cancer and a high proportion (38.9% ) agreed that screening causes harm.

Table 4.

Attitude of the 95 participants from the Lutubeni community towards cervical cancer and screening.

Table 4.

Attitude of the 95 participants from the Lutubeni community towards cervical cancer and screening.

Variables used to measure attitude |

SA |

A |

NADA |

DA |

| n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

| Cervical cancer is a highly prevalent disease among women in South Africa |

64(67.4) |

20(21.1) |

6(6.3) |

5(5.3) |

| Cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death among women in South Africa |

30(31.6) |

38(40.0) |

14(14.7) |

13(13.7) |

| Any adult woman including you can acquire cervical cancer |

35(36.8) |

41(43.2) |

16(16.8) |

3(3.2) |

| Cervical cancer cannot be transmitted from one person to another |

26(27.4) |

44(46.3) |

13(13.7) |

12(12.6) |

| Screening helps in the prevention of cervical cancer |

29(30.5) |

48(50.5) |

12(12.6) |

6(6.3) |

| Screening causes no harm to the client |

30(31.6) |

37(38.9) |

17(17.9) |

11(11.6) |

| |

|

|

|

|

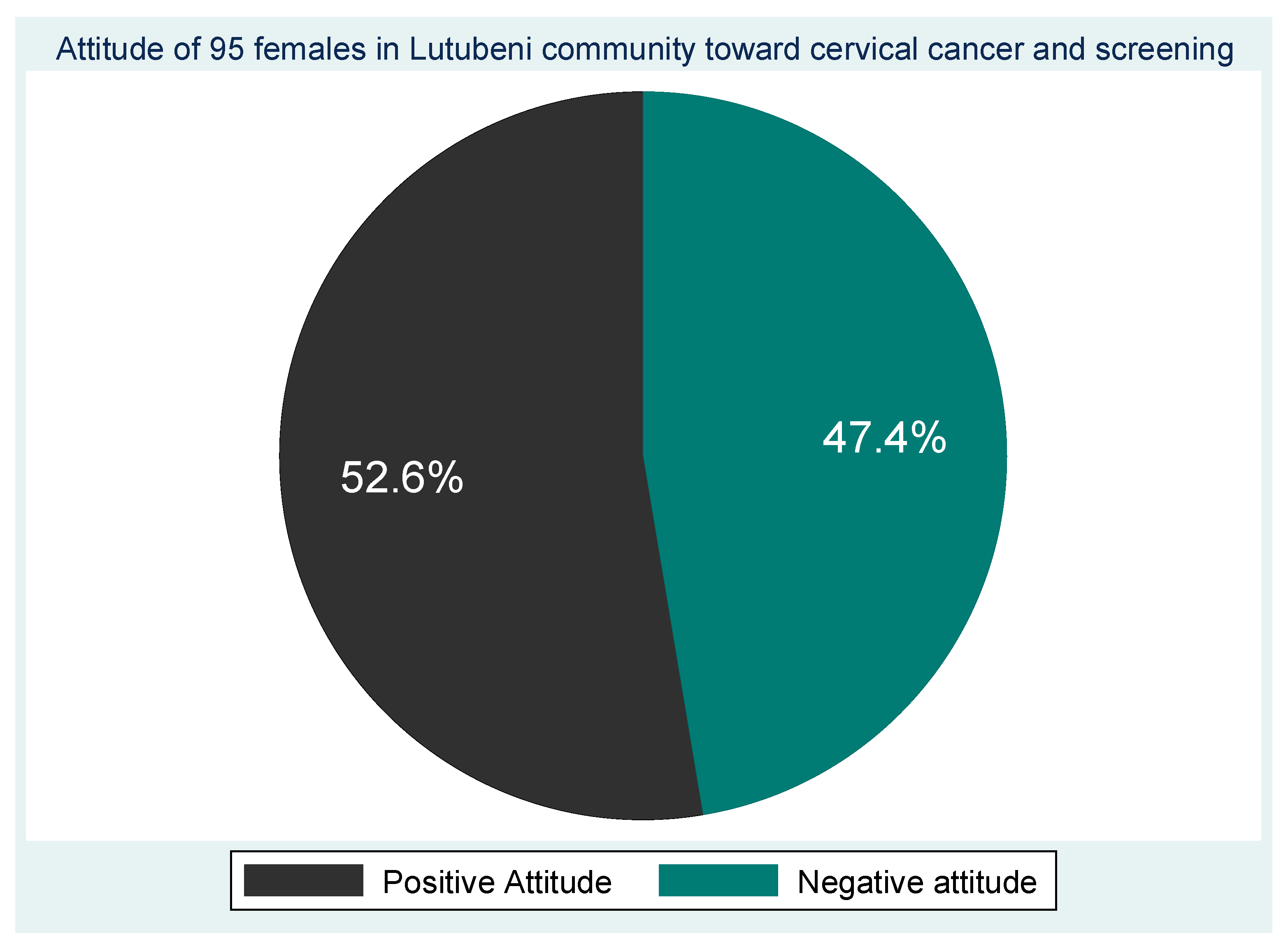

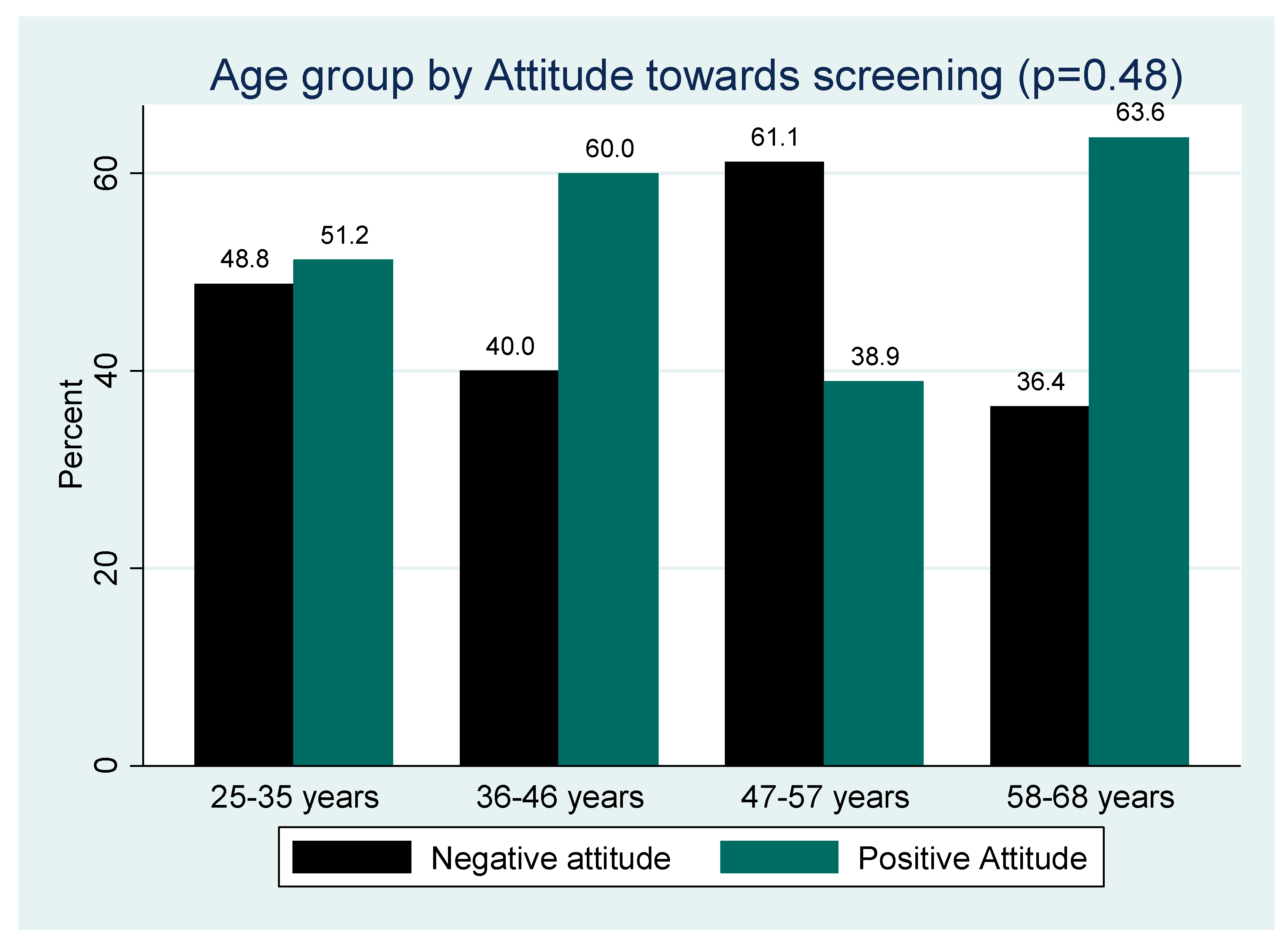

3.5. Overall Attitudes Scores and Age by Attitudes of Participants

The results of the overall attitude score show that slightly more than half (52.6% n=50) of the participants had a positive attitude towards cervical cancer and screening and almost half (47.4% n=45) had a negative attitude (

Figure 3).

Figure 4 shows Positive attitude was highest among the elderly (58-68 years) while negative was highest among the 47 years to 57 years age group (

Figure 4). The differences in proportion of positive and negative attitude across the different age groups was statistically significant (p=0.48).

Figure 3.

Attitude of the participants towards cervical cancer and screening.

Figure 3.

Attitude of the participants towards cervical cancer and screening.

Figure 4.

Age group by Attitude toward cervical cancer and screening.

Figure 4.

Age group by Attitude toward cervical cancer and screening.

3.6. Cultural Views Regarding Cervical Cancer Among Study Participants

Study participants with Cultural views regarding cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening that these aspects were false (

Table 5).

Table 5.

Cultural views regarding cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening.

Table 5.

Cultural views regarding cervical cancer and cervical cancer screening.

| Variable |

True n (%) |

False n (%) |

| Sexual Organs are not a topic for discussion |

84 (88.4) |

11 (11.6) |

| Diagnosis with Cervical Cancer is Associated with Death |

28 (29.5) |

67 (70.5) |

| Diagnosis with Cervical Cancer means you are having Multiple Sexual Partners |

16 (16.8) |

79 (83.2) |

| Diagnosis with Cervical Cancer means you are Promiscuous |

18 (18.9) |

77 (81.1) |

| Fear of Cervical Cancer |

21 (22.1) |

74 (77.9) |

| Cervical Cancer is Perceived to be caused by Indecent Behaviour |

31 (32.6) |

64 (67.4) |

| Need approval from Partner for Cervical Cancer Screening |

11 (11.6) |

84 (88.4) |

| Cultural Views around Cervical Cancer Screening influence my decision to screen |

7 (7.4) |

88 (92.6) |

| Traditional Medicines are the primary healthcare-seeking option |

11 (11.6) |

84 (88.4) |

| Views around Cervical Cancer Screening are the primary reason why I have never been screened for Cervical Cancer |

4 (4.2) |

91 (95.8) |

| One’s sexual organs are private and not supposed to be exposed or touched |

91.6) |

8 (8.4) |

3.7. Cervical Screening Practice and Cervical Screening Experiences of the Participants

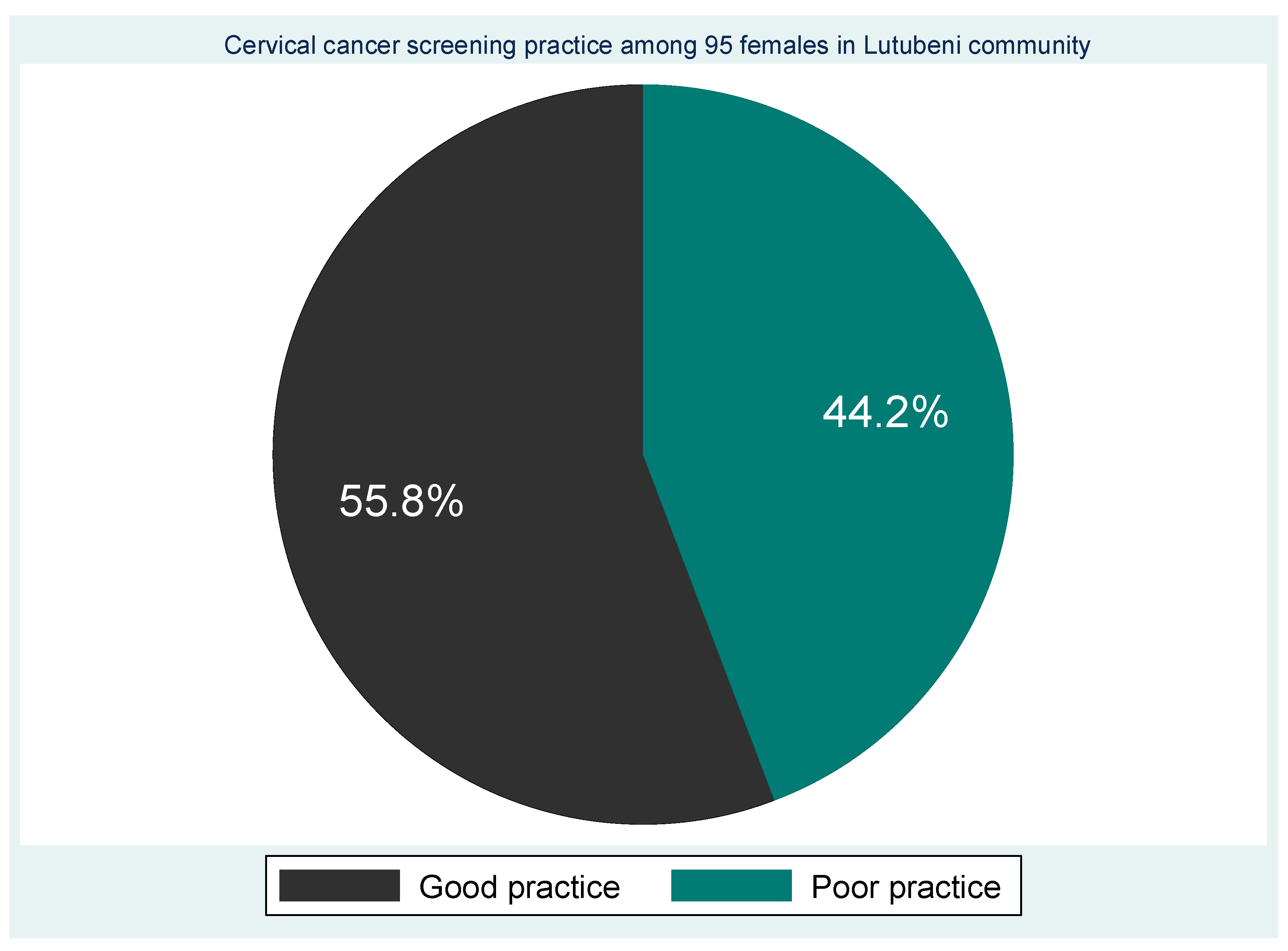

The majority (55.8% ) had screened for cervical cancer and 42 (44.2%) had never screened for cervical cancer (

Table 5). Those who had screened one time (43.2% ) . A high proportion (33.7% ) of them had been screened in the clinic and 39 (44.1%) were screened at the initiation of a health professional, (13.7%) were self-initiated and the rest (1.1% ) was initiated by a friend. Eighty-eight (92.6% n=88) participants had screened for other reproductive issues such as HIV and STI. Based on screening experiences the 55.8 percent were labelled as having good screening practice and 44.2% as poor screening practice (

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cervical screening experiences of the participants.

Figure 5.

Cervical screening experiences of the participants.

Table 6.

Cervical screening Practice of the participants.

Table 6.

Cervical screening Practice of the participants.

| Variable |

Category |

Frequency (n=95) |

Percent (%) |

| Have you ever been screened for cervical cancer |

Yes |

53 |

55.8 |

| No |

42 |

44.2 |

| Where did you screen |

Never screened |

42 |

44.2 |

| Clinic |

32 |

33.7 |

| Hospital |

20 |

21.1 |

| Others |

1 |

1.1 |

| How many times did you screen |

Once |

41 |

43.2 |

| Twice |

8 |

8.4 |

| Thrice |

2 |

2.1 |

| Four times |

1 |

1.1 |

| Five times |

1 |

1.1 |

| When was the last time you screened |

Last year |

28 |

29.4 |

| > 3 years |

12 |

12.6 |

| Within the past 3 years |

9 |

9.5 |

| <3 years |

4 |

4.2 |

| Who initiated you to be screened |

Health professional |

39 |

41.1 |

| Self -initiated |

13 |

13.7 |

| Others |

1 |

1.1 |

| Have you ever made use of reproductive health services like HIV or STI testing |

Yes |

88 |

92.6 |

| No |

7 |

7.4 |

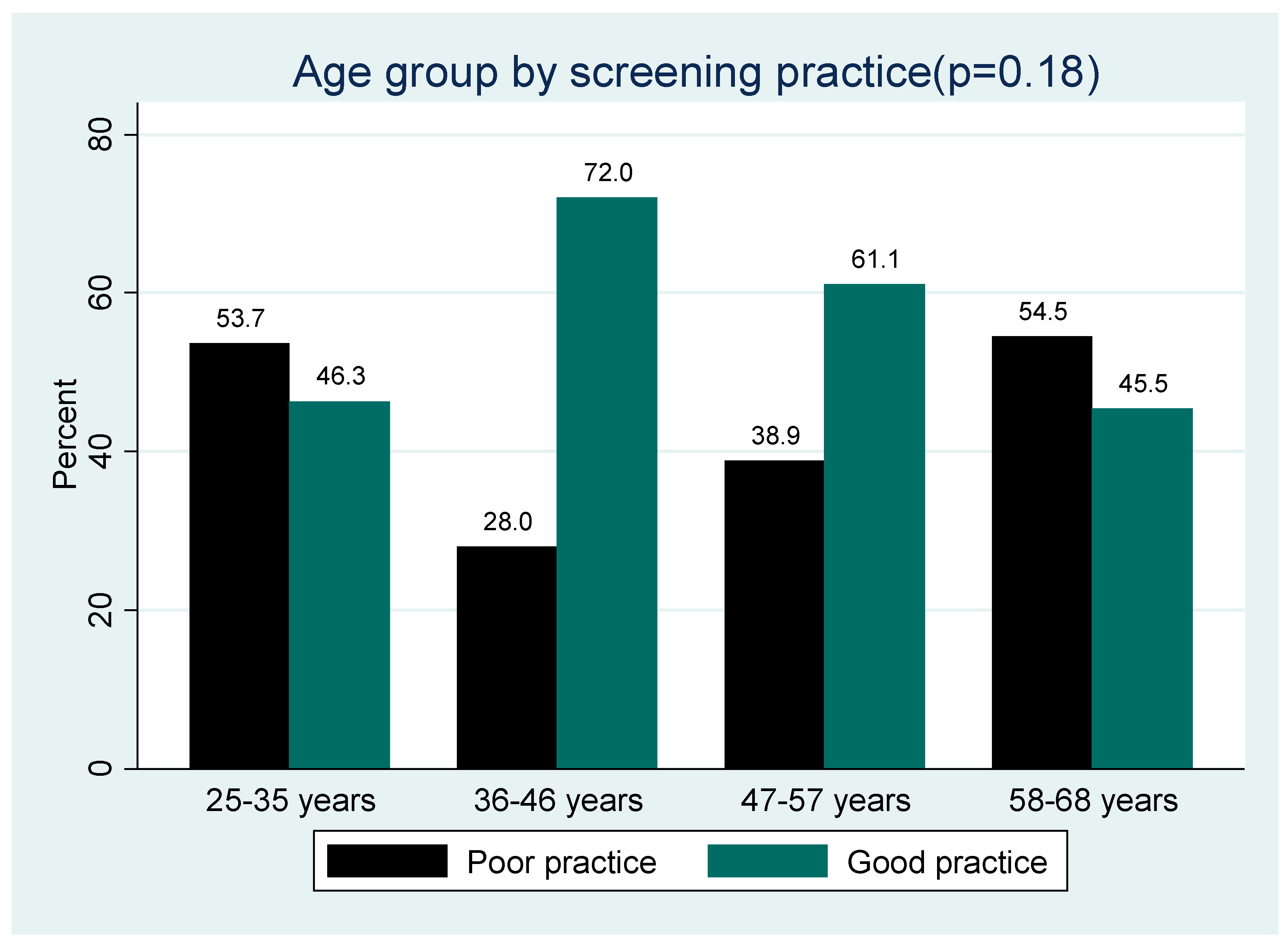

3.7. Age group by Cervical Cancer Screening Practice

The proportion of participants who screened for cervical cancer across the different age groups (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) was not statistically significantly different (p>0.05), although good practice was highest among the middle age group (36-46 years) and poor practice among the elderly (58-68 years).

Figure 6.

Age group by Cervical cancer screening practice.

Figure 6.

Age group by Cervical cancer screening practice.

3.8. Factors Associated with Practice Towards Cervical Cancer Screening

Bivariate analysis revealed that educational attainment, knowledge of cervical cancer symptoms, risk factors, prevention, treatment, screening availability, screening procedures, composite knowledge, and attitude towards screening were all significantly associated with cervical cancer screening practices (

Table 7). Participants with a diploma or degree were significantly more likely to exhibit good screening practices (87.5%;

p = 0.047). Good practice was also significantly associated with adequate knowledge of cervical cancer symptoms (69.6%;

p = 0.040), risk factors (90.9%;

p < 0.0001), treatment (91.7%;

p < 0.001), screening procedures (100%;

p = 0.002), and composite knowledge (100%;

p < 0.0001).

Conversely, poor screening practice was significantly associated with poor knowledge of screening availability (100%; p < 0.0001) and negative attitudes towards cervical cancer screening (82.9%; p < 0.0001).

Table 7.

Factors associated with practice towards cervical cancer screening.

Table 7.

Factors associated with practice towards cervical cancer screening.

Associate factors |

Cervical cancer screening practice |

X2 p-value |

| Poor practice (N=42) |

Good practice (N=53) |

| Educational status |

|

|

0.047* |

| Degree |

1 (33.3) |

2 (66.7) |

|

| Diploma |

3 (18.8) |

13 (81.2) |

|

| Diploma/Degree |

1 (12.5) |

7 (87.5) |

|

| No formal education |

7 (58.3) |

5 (41.7) |

|

| Primary school |

9 (56.2) |

7 (43.8) |

|

| Secondary |

21 (52.5) |

19 (47.5) |

|

| Knowledge of symptoms of cervical cancer |

|

|

0.04 |

| Good |

7 (30.4) |

16 (69.6) |

|

| Moderate |

9 (33.3) |

18 (66.7) |

|

| Poor |

26 (57.8) |

19 (42.2) |

|

| Knowledge related to the risk factor of Cervical cancer |

|

|

<0.0001* |

| Good |

1 (9.1) |

10 (90.9) |

|

| Moderate |

5 (19.2) |

21 (80.8) |

|

| Poor |

36 (62.1) |

22 (37.9) |

|

| Knowledge related to prevention |

|

|

<0.0001* |

| Good |

4 (10.3) |

35 (89.7) |

|

| Moderate |

2 (50.0) |

2 (50.0) |

|

| Poor |

36 (69.2) |

16 (30.8) |

|

| Knowledge related to the treatment of cervical cancer |

|

|

0.001 |

| Good |

1 (8.3) |

11 (91.7) |

|

| Moderate |

14 (34.1) |

27 (65.9) |

|

| Poor |

27 (64.3) |

15 (35.7) |

|

| Knowledge of screening availability |

|

|

<0.0001* |

| Good |

31 (37.3) |

52 (62.7) |

|

| Moderate |

3 (75.0) |

1 (25.0) |

|

| Poor |

8 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

| Knowledge related to Cervical screening procedure |

|

|

0.002* |

| Good |

0 (0.0) |

1 (100.0) |

|

| Moderate |

32 (38.6) |

51 (61.4) |

|

| Poor |

10 (90.9) |

1 (9.1) |

|

| Composite Knowledge |

|

|

<0.0001* |

| Good |

0 (0.0) |

3 (100.0) |

|

| Moderate |

11 (22.9) |

37 (77.1) |

|

| Poor |

31 (70.5) |

13 (29.5) |

|

| Attitude towards cervical cancer and screening |

|

|

<0.0001 |

| Negative attitude |

29 (82.9) |

6 (17.1) |

|

| Positive Attitude |

13 (21.7) |

47 (78.3) |

|

3.9. Independent Factors Associated with Poor Practice

The multinomial logistic regression analysis identified three independent predictors of poor cervical cancer screening practice: having a diploma, good knowledge of prevention, and a negative attitude towards screening (

Table 8). Surprisingly, participants with a diploma or good preventive knowledge were less likely to undergo screening. Notably, participants with a negative attitude were significantly more likely to forgo screening (OR = 36.22;

p = 0.005).

Table 8.

Independent factors associated with poor practice.

Table 8.

Independent factors associated with poor practice.

| Independent factors of poor practice |

B |

p-value |

OR (95% CI) |

| Poor screening practice Versus good screening practice |

Held a Diploma |

-3.278 |

0.042 |

0.04 (0.002-0.894) |

| Good knowledge related to Prevention |

-3.905 |

0.012 |

0.02 (0.001-0.424) |

| Negative attitude towards cervical cancer and screening |

3.590 |

0.005 |

36.22 (2.9-453.6) |

|

Model:X2 = 85.3; Nagelkerke R2 =79.3%; p<0.0001.B=Regression coefficient, OR = Odd Ratio

|

4. Discussion

This study explored the knowledge, attitudes, cultural beliefs, and cervical cancer screening practices among women in a rural South African setting, revealing a complex interplay of awareness, education, cultural norms, and behavioral factors influencing screening uptake. Despite relatively high awareness (87.4%) about cervical cancer and its screening services, only slightly more than half (55.8%) of participants had ever undergone screening. These findings are consistent with studies conducted in similar settings, where awareness does not necessarily translate into action, largely due to cultural and psychosocial barriers [

20,

21,

22]. The knowledge assessment revealed that only 3.2% of respondents demonstrated good composite knowledge of cervical cancer, aligning with other research from sub-Saharan Africa that underscores persistent knowledge gaps despite public health campaigns [

16,

23,

24]. While symptoms like vaginal bleeding and foul-smelling discharges were widely recognized, deeper understanding of risk factors particularly HPV infection was limited. This may reflect deficiencies in community targeted educational strategies and the lack of integration between HPV vaccination programs and cervical cancer awareness [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Our study further established that cultural beliefs particularly the taboo surrounding discussions about sexual and reproductive health remained pervasive, with 88.4% of participants agreeing that sexual organs are not topics for open conversation. These sociocultural constraints reflect broader findings from Zimbabwe and Namibia, where patriarchal norms, stigma, and misinformation hinder access to preventive services [

29,

30,

31,

32]. The role of education in influencing screening behavior was notable. Women with diploma or higher qualifications were more likely to have undergone screening. However, paradoxically, multinomial logistic regression revealed that holding a diploma was an independent predictor of poor screening practice. This may be due to the small sample size of diploma holders and potential confounding factors such as employment type or health service accessibility. Attitudes toward screening were strongly predictive of behavior. Participants with negative attitudes were over 36 times more likely to forgo screening (OR = 36.22; p = 0.005). This finding aligns with recent studies emphasizing that perception and trust in healthcare systems, fear of pain or diagnosis, and fatalistic beliefs significantly deter women from utilizing preventive services [

33,

34,

35]. Despite the availability of free cervical screening services in South Africa, structural and behavioral barriers persist. Poor knowledge of screening intervals and eligibility criteria further contributes to inconsistent or delayed uptake. Notably, the WHO’s 90-70-90 strategy for cervical cancer elimination by 2030 emphasizes the need for 70% of women to be screened by age 35 and again by 45; however, achieving these targets will be difficult without concerted community-based health education and structural reforms [

36,

37,

38,

39].

4.1. Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, the use of a convenience sampling method limits the generalizability of the findings to other rural settings. Second, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce recall and social desirability biases, especially in sensitive topics such as sexual history and health service utilization. Third, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. Lastly, the small sample size and the limited representation of certain educational and age subgroups may affect the robustness of multivariate associations.

4.2. Future Research

Future studies should adopt a longitudinal design to assess changes in knowledge and behavior over time and examine the impact of targeted interventions. Qualitative studies exploring personal, familial, and community-level barriers would offer richer insights into the socio-cultural dynamics affecting screening uptake. Furthermore, investigations into the role of male partners and community leaders in influencing women’s health-seeking behaviors could inform more inclusive and culturally sensitive educational strategies. Lastly, evaluating the effectiveness of mobile health interventions (e.g., SMS reminders or telehealth education) in rural settings could offer scalable solutions to address barriers identified in this study.

5. Conclusions

Although awareness of cervical cancer screening was relatively high among women in the Lutubeni community, overall knowledge remained poor, and nearly half of the participants had never undergone screening. Cultural taboos, negative attitudes, and gaps in knowledge continue to hinder optimal utilization of screening services. These findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive, culturally appropriate health education programs that go beyond awareness to address deep-seated beliefs, misinformation, and attitudinal barriers. Improving cervical cancer screening rates in rural South Africa will require a multifaceted approach that incorporates education, community engagement, and healthcare system strengthening in alignment with global cervical cancer elimination goals.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, O.O.A and M.K.N , methodology O.O.A and M.K.N and M.C.H; software, M.K.N.; validation, O.O.A,M.C.H and M.C.H.; formal analysis M.K.N.; investigation O.O.A,M.C.H and M.KN.; resources, M.K.N; data curation, M.K.H writing—original draft preparation, O.O.A and M.C.H ; writing—review and editing, O.O.A ,M.C.H and M.K.N .; visualization, O.O.A,M.C.H and M.K.N.; supervision, M.K.N..; project administration, M.K.N..; funding acquisition, M.K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY HEALTH SCIENCES RESEARCH ETHICS COMMITTEE (protocol code 086/2022 and date of approval 12/09/2024) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reason.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to the Operational Manager of Lutubeni Clinic for her support and assistance in the data collection exercise. We would also like to thank the nurses and all the staff of the clinic for their support. Many thanks to the trained research assistants who assisted with data collection. The community members of Lutubeni community are appreciated for participating in our research. This study was conducted as part of the Community-Based Education and Service (COBES) programme for MBChB level three students at Walter Sisulu University. We gratefully acknowledge the Department of Facilities and Transport for logistical support, the Directorate of Community Engagement and Internationalisation for coordinating with the Department of Health, as well as the Dean’s Office of the Faculty of Health Sciences and the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology for their administrative and academic support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SSA |

Sub Saharan Africa |

| OR |

Odd Ratio |

| COBES |

Community-Based Education and Service |

| LMIC |

Low- Middle Income Country |

References

- Mengesha, A.; Messele, A.; Beletew, B. Knowledge and attitude towards cervical cancer among reproductive age group women in Gondar town, North West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Cervical Cancer 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Gutusa, F.; Roets, L. Early cervical cancer screening: The influence of culture and religion. Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med. 2023, 15, a3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Duan, H.; Feng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lyu, Z. Global burden of cervical cancer: current estimates, temporal trend and future projections based on the GLOBOCAN 2022. J Nat Cancer Center 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Wagar, M.K.; Hsu, H.C.; Hoegl, J.; Valzacchi, G.M.R.; Fernandes, A.; Cucinella, G.; Aker, S.S.; Jayraj, A.S.; Mauro, J.; Pareja, R. Cervical cancer: a new era. Int J Gynecological Cancer 2024, 34, 1946–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutambara, J.; Mutandwa, P.; Mahapa, M.; Chirasha, V.; Nkiwane, S.; Shangahaidonhi, T. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of cervical cancer screening among women who attend traditional churches in Zimbabwe. J Cancer Res. Pract 2017, 4, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Uchendu, I.; Hewitt-Taylor, J.; Turner-Wilson, A.; Nwakasi, C. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about cervical cancer, and the uptake of cervical cancer screening in Nigeria: An integrative review. Scientific Afr 2021, 14, e01013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Yin, A.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Tang, L.; Kong, B. Global landscape of cervical cancer incidence and mortality in 2022 and predictions to 2030: The urgent need to address inequalities in cervical cancer. Int J Cancer 2025, 157, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbyn, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Bruni, L.; de Sanjosé, S.; Saraiya, M.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2020, 8, e191–e203.e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, J.; Constant, D.; Mwaka, A.D.; Scott, S.E.; Walter, F.M. Anticipated help seeking behaviour and barriers to seeking care for possible breast and cervical cancer symptoms in Uganda and South Africa. eCancer Med Sci 2021, 15, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussia, B.; Shewangizaw, M.; Abebe, S.; Alemu, H.; Simon, T. Health care seeking behaviour towards cervical cancer screening among women aged 30–49 years in Arbaminch town, Southern Ethiopia, 2023. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtu, Y.; Yohannes, S.; Laelago, T. Health seeking behavior and its determinants for cervical cancer among women of childbearing age in Hossana Town, Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia: community based cross sectional study. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon: Int Agency for Res Cancer, 2020; 20182020. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaliba, T.M.; Sithole, N.; Ncinitwa, A. Cancer incidence in selected municipalities of the Eastern Cape Province, 2013–2017. Eastern Cape Cancer Registry Technical Report. 2020 South African Medical Research Council.

- Jassim, G.; Obeid, A.; Al Nasheet, H.A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding cervical cancer and screening among women visiting primary health care Centres in Bahrain. BMC Public health 2018, 18, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitha, W.; Sibulawa, S.; Funani, I.; Swartbooi, B.; Maake, K.; Hellebo, A.; Hongoro, D.; Mnyaka, O.R.; Ngcobo, Z.; Zungu, C.M.; Sithole, N. A cross-sectional study of knowledge, attitudes, barriers and practices of cervical cancer screening among nurses in selected hospitals in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. BMC Women's Health 2023, 23, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwaka, A.D.; Orach, C.G.; Were, E.M.; Lyratzopoulos, G.; Wabinga, H.; Roland, M. Awareness of cervical cancer risk factors and symptoms: cross-sectional community survey in post-conflict northern Uganda. Health Expectations 2016, 19, 854–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapera, R.; Manyala, E.; Erick, P.; Maswabi, T.M.; Tumoyagae, T.; Letsholo, B.; Mbongwe, B. Knowledge and attitudes towards cervical cancer screening amongst University of Botswana female students. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prevention: APJCP 2017, 18, 2445. [Google Scholar]

- Anyolo, E.; Amakali, K.; Amukugo, H.J. Attitudes of women towards screening, prevention and treatment of cervical cancer in Namibia. Health SA Gesondheid 2024, 29, a2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aredo, M.A.; Sendo, E.G.; Deressa, J.T. Knowledge of Cervical Cancer Screening and Associated Factors among Women Attending Maternal Health Services at Aira Hospital, West Wollega, Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 205031212110470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, E.A.; Appiah, S.; Gaogli, J.E.; Oti-Boadi, E. Knowledge on Cervical Cancer Screening and Vaccination among Females at Oyibi Community. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaluka, J.H.M. Utilization of Cervical Cancer Screening Services among Women Aged 30–49 Years in Kitui County, Kenya. Doctoral Dissertation, Kenyatta University.

- Ncane, Z.; Faleni, M.; Pulido-Estrada, G.; Apalata, T.R.; Mabunda, S.A.; Chitha, W.; Nomatshila, S.C. Knowledge on Cervical Cancer Services and Associated Risk Factors by Health Workers in the Eastern Cape Province. Healthcare 2023, 11, 325–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiiti, T.A.; Bogers, J.; Lebelo, R.L. Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer among Women Attending Gynecology Clinics in Pretoria, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Narayan, N.; Sinha, R.; Sinha, P.; Sinha, V.P.; Upadhye, J.J. Awareness about Cervical Cancer Risk Factors and Symptoms. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 7, 4987–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, D.B.; Koffi, S.V.; Nsahlai, C.J.; Adjoby, R.; Gbary, E.; N’guessan, K.; Boni, S. Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviors of Clients Regarding Cervical Cancer Screening at Gynecology Consultations of the University Hospital of Cocody. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 2023, 73 (Suppl 1), 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekle, T.; Wolka, E.; Nega, B.; Kumma, W.P.; Koyira, M.M. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards Cervical Cancer Screening among Women and Associated Factors in Hospitals of Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ken-Amoah, S.; Blay Mensah, L.B.; Eliason, S.; Anane-Fenin, B.; Agbeno, E.K.; Essuman, M.A.; Essien-Baidoo, S. Poor Knowledge and Awareness of Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer among Adult Females in Rural Ghana. Front. Trop. Dis. 2022, 3, 971266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantula, F.; Toefy, Y.; Sewram, V. Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening in Africa: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthali, A.C.; Ngwira, B.M.; Taulo, F. Exploring Barriers to the Delivery of Cervical Cancer Screening and Early Treatment Services in Malawi: Some Views from Service Providers. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2015, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzobo, M.; Dzinamarira, T. Effective Cervical Cancer Prevention in Sub-Saharan Africa Needs the Inclusion of Men as Key Stakeholders. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1509685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzobo, M.; Dzinamarira, T.; Jaya, Z.; Kgarosi, K.; Mashamba-Thompson, T. Experiences and Perspectives Regarding Human Papillomavirus Self-Sampling in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Evidence. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnazi, H.; Ahmadi-Livani, M.; Pahlavanzadeh, B.; Rajabi, A.; Hamrah, M.S.; Charkazi, A. Assessing Preventive Health Behaviors from COVID-19: A Cross Sectional Study with Health Belief Model in Golestan Province, Northern of Iran. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinath, A.; van Merode, F.; Rao, S.V.; Pavlova, M. Barriers to Cervical Cancer and Breast Cancer Screening Uptake in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Health Policy Plan 2023, 38, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajimakin, O. Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistie, B.A.; Melese, M.; Gebiru, A.M.; Getnet, M.; Getahun, A.B.; Tassew, W.C.; Bitew, D.A. Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening and Its Determinants in Africa: Umbrella Review. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0328103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Chen, M.; Ren, W.; Bao, Y.; Qiao, Y. Knowledge, Willingness, Uptake and Barriers of Cervical Cancer Screening Services among Chinese Adult Females: A National Cross-Sectional Survey Based on a Large E-Commerce Platform. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, J. Impact of the WHO’s 90-70-90 Strategy on HPV-Related Cervical Cancer Control: A Mathematical Model Evaluation in China. arXiv 2506, arXiv:arXiv:2506.06405. [Google Scholar]

- Harder, M.T.; Mokete, M.; Chammartin, F.; Lerotholi, M.; Motaboli, L.; Kopo, M.; Belus, J.M. Cervical Cancer Screening Delay and Associated Factors among Women with HIV in Lesotho: A Mixed-Methods Study. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).