Introduction

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, is an autosomal dominant vascular dysplasia [

1,

2] with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 5,000 individuals [

3,

4]. It is caused by mutations in components of the BMP/ENG/ALK1/Smad4 signaling pathway, which play a key role in angiogenesis [

5]. Clinically, HHT is characterized by telangiectasias affecting the skin and mucosal surfaces, particularly in the nose, oral and gastrointestinal tract, as well as by visceral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) involving the central nervous system, lungs, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. Telangiectasias are structurally fragile, and their frequent rupture leads to typical manifestations such as recurrent epistaxis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and iron deficiency anemia [

6]. AVMs, on the other hand, may result in organ-specific complications, including cerebral hemorrhage, thromboembolic or infectious events secondary to pulmonary AVMs (such as ischemic stroke or brain abscess), and high-output cardiac failure with secondary pulmonary hypertension or portal hypertension, due to hepatic vascular malformations (HVMs) [

2]. The diagnosis of HHT is based on the Curaçao criteria and/or genetic testing [

7,

8].

Current treatment strategies focus on preventing complications related to vascular malformations and reducing nasal and gastrointestinal bleeding, while curative approaches remain unavailable [

2,

9]. Epistaxis is the most common clinical manifestation, affecting up to 95% of patients. Due to its severity and recurrence, it can severely impair quality of life, cause disability, or even become life-threatening [

10,

11]. Hygiene, lubrication or moisturizing represent the first step of treatment of epistaxis in HHT. Although various ablative and surgical interventions (laser, sclerotherapy, electrocoagulation, septodermoplasty, nasal closure etc.) are available, none have demonstrated complete efficacy, tolerability, or broad accessibility [

9,

12,

13]. Pharmacological strategies including anti-angiogenic agents, aimed at reducing abnormal vessel formation, as well as antifibrinolytic therapies that stabilize clots and limit bleeding, represent an attractive and rational approach for more sustained and acceptable management of epistaxis [

9,

14,

15].

Propranolol is a non-selective beta-blocker widely used for cardiovascular conditions and for other indications such as migraine, essential tremor hyperthyroidism and cancer [

16]. Beyond these applications, it exerts well-documented antiangiogenic effects, being the first-line treatment for infantile hemangioma and designated as an orphan drug for other vascular anomalies [

17,

18,

19]. Propranolol-mediated β-adrenergic receptor blockade induces vasoconstriction and reduces hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) nuclear translocation, leading to inhibition of pro-angiogenic target genes, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), endoglin (ENG), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF). In addition, it decreases phosphorylation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK) and proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src (Src) pathways, thereby activating caspases, promoting apoptosis, and ultimately suppressing angiogenesis [

19,

20,

21]. Several small studies with limited quality of evidence have explored the systemic or topical use of propranolol and other beta-blockers for epistaxis in HHT, with encouraging results [

19,

21,

22,

23,

24].

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of propranolol on epistaxis in patients with HHT. Secondary objectives included comparing baseline and 6-month clinical characteristics, assessing adverse events, and describing the dosages used.

3. Results

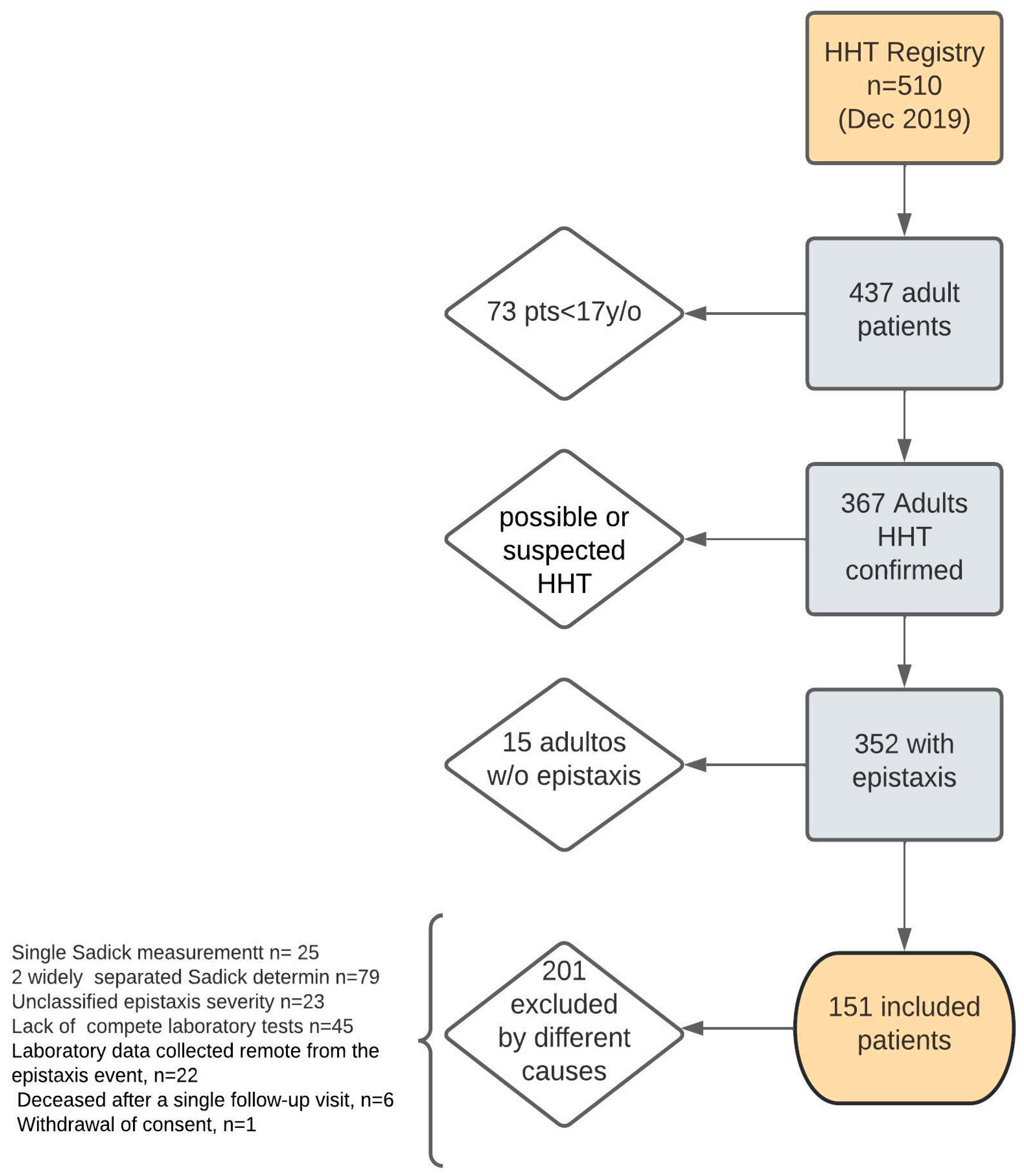

As of December 31, 2019, the Institutional HHT Registry included 510 patients, of whom 151 were eligible and included in this analysis, according to the criteria outlined in

Figure 1.

To evaluate whether the exclusion of 201 patients could have introduced a selection bias (e.g., loss to follow-up, death, or other factors that might compromise the internal validity of the study), we compared the baseline characteristics of excluded versus included patients. Included patients were older and had a higher prevalence of AVMs. No significant differences were observed in bleeding severity as assessed by the Sadick scale. These comparisons are shown in

Table 2.

Among the 151 patients analyzed, 56 (37.1%) were male, and the median age was 50 years (IQR 37–65). Propranolol was prescribed in 44 patients (29.1%), of whom 33 (75%) had an additional clinical indication: migraine in 9 (20.5%), hypertension in 14 (31.8%), and tachyarrhythmias or palpitations in 10 (22.7%). In 11 patients (25%), propranolol was prescribed with the primary intention of treating epistaxis, considered an expert-driven decision without a conventional cardiovascular indication. In this subgroup, the rationale for prescription was based on the anticipated antiangiogenic and vasoconstrictive properties of propranolol, described herein as expert indication for treatment with the intention to control bleeding.

Adverse events were reported in six patients: hypotension in three, sleep disturbances in one, and mood alterations in two. Patients in the propranolol group were older and more frequently received additional pharmacological therapies (other than propranolol), particularly antifibrinolytics.

Table 3 summarizes the baseline characteristics of patients according to propranolol prescription. In terms of nasal lubrication and hygiene, adherence was higher among patients treated with propranolol, who showed better compliance and lower rates of non-adherence. No significant differences were observed between groups regarding the presence of vascular malformations in other organs, surgical procedures, or conditions such as anticoagulant use or additional hemorrhagic disorders unrelated to HHT. Similarly, bleeding severity, as measured by the Sadick scale, was comparable across groups both for individual domains and for the dichotomized evaluation (≥3 vs. <3) of intensity and frequency.

⇒ There were no other bleeding conditions such as hemophilia and other coagulopathies. Nor were there any patients undergoing antiplatelet therapy; ✝Presence of any visceral involvement with vascular malformations (pulmonary and/or hepatic and/or digestive and/or other organs; antiangiogenic treatment other than Bevacizumab; #Hemoglobin value less than 12 mg/dL in women and less than 13 mg/dL in men; ↡Any of the following pharmacological treatments (one or more): bevacizumab, hormonal, antifibrinolytic, antiangiogenic other than bevacizumab; ⇟Total non-compliance with daily nasal lubrication and hygiene measures; n, Absolute frequency; %, Relative frequency in percentage; IQR, interquartile range (P25–P75); SD, standard deviation; HMO, Health Maintenance Organization; CNS, Central Nervous System; RBC, Red Blood Cell.

The study population corresponds to individuals over 50 years of age, who are more likely to undergo endoscopic studies, in order to avoid including patients without indications for endoscopic studies. Therefore, n corresponds to 48 for the non-propranolol group and 32 for the propranolol group.

Results on Propranolol Dosage

Regarding prescribed doses, 35 patients (79%) received low doses (20–60 mg), while 8 patients (18%) received intermediate doses (80–160 mg). No patients received high doses (>240 mg). No significant differences were observed between the groups (p = 0.597).

Results on Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding was assessed in patients aged >50 years, both with and without propranolol treatment. This restriction was applied to minimize selection bias, as after this age patients are more likely to undergo gastrointestinal evaluation either through colorectal cancer screening protocols (which in our center almost always include upper endoscopy) or because GI bleeding due to HHT becomes more frequent beyond this age. Among the 48 patients not treated with propranolol, 9 (18.8%) presented with GI bleeding at 6 months, compared with 8 out of 32 patients (25%) in the propranolol group. At baseline, only 1 patient in the non-propranolol group presented bleeding, whereas in the propranolol group, 2 patients who had no bleeding at baseline developed bleeding during follow-up. No significant differences were observed between groups (p = 0.535).

Hemoglobin and Iron Supplementation

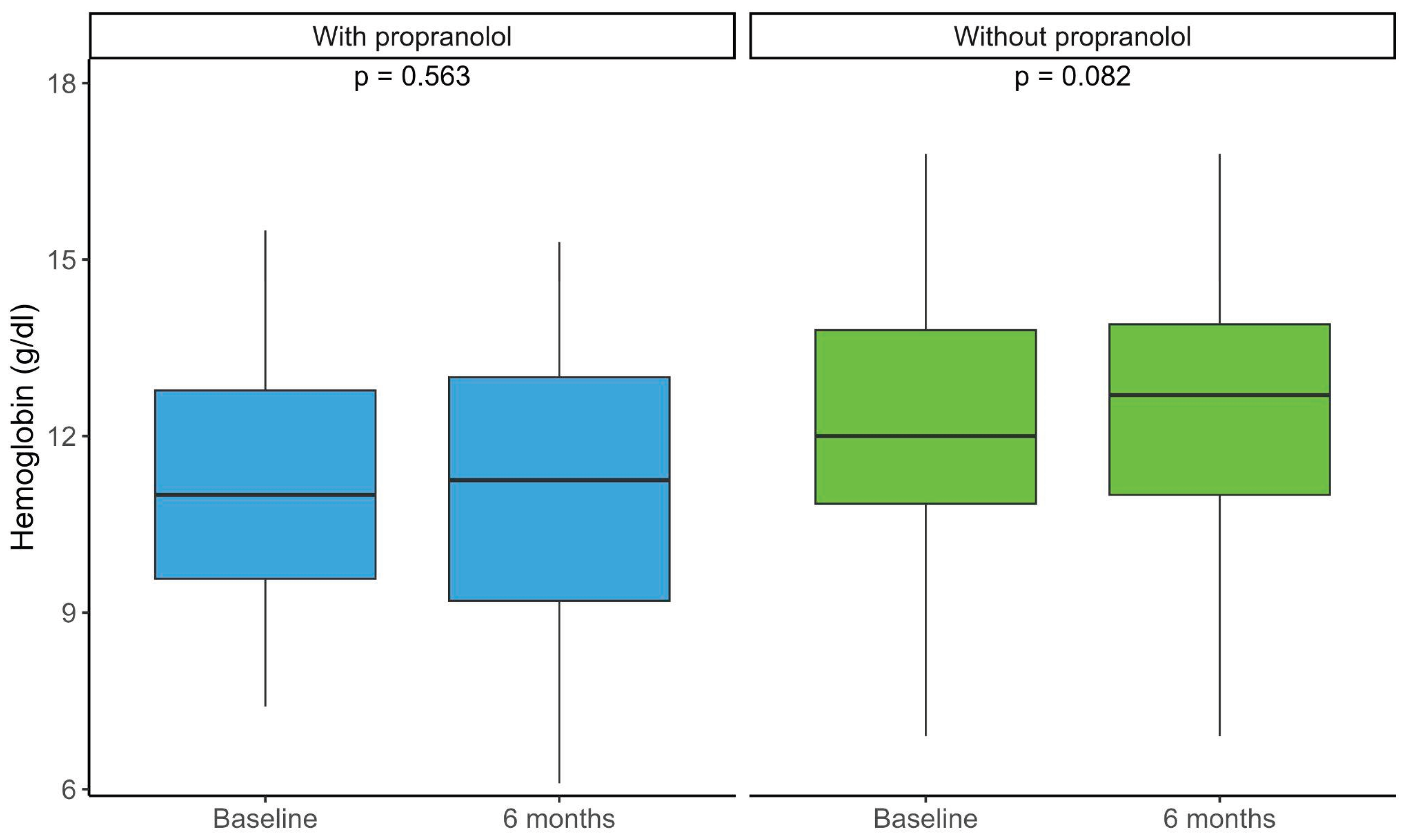

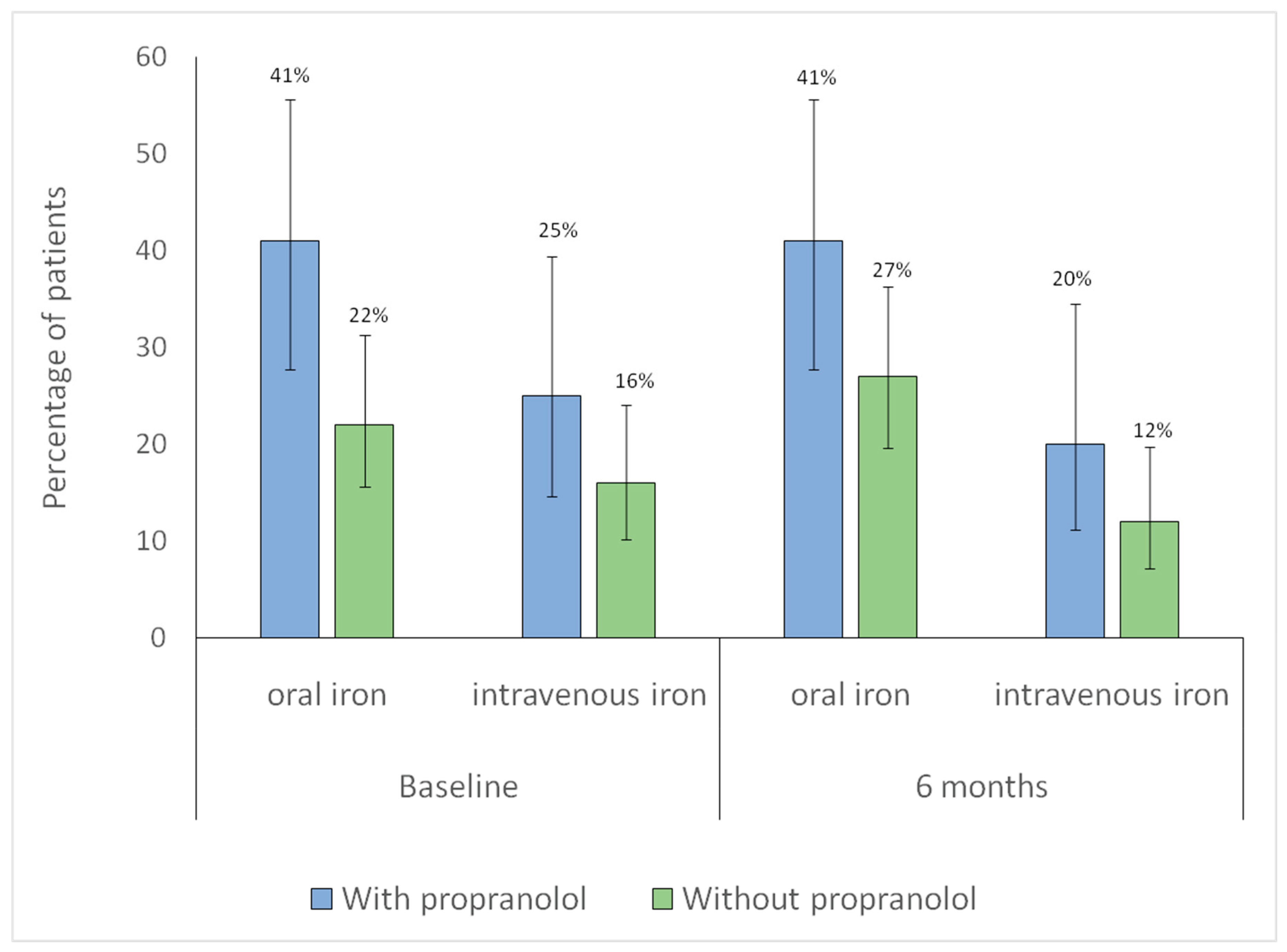

Changes in hemoglobin levels before and after 6 months were assessed in both propranolol-treated and untreated patients. No significant differences were observed between baseline and 6-month values in either group (

Figure 2). Patients treated with propranolol, however, had lower baseline hemoglobin levels, indicating more severe anemia (

Table 2).

Additionally, changes in iron supplementation from baseline to six months were analyzed in both groups. No significant within-group differences were observed over time in intravenous iron use (without propranolol,

p = 0.79; with propranolol,

p = 1.00), indicating stable utilization. Similarly, no significant changes were found in oral iron use (without propranolol,

p = 0.42; with propranolol,

p = 1.00), suggesting consistent oral supplementation throughout follow-up (

Figure 3).

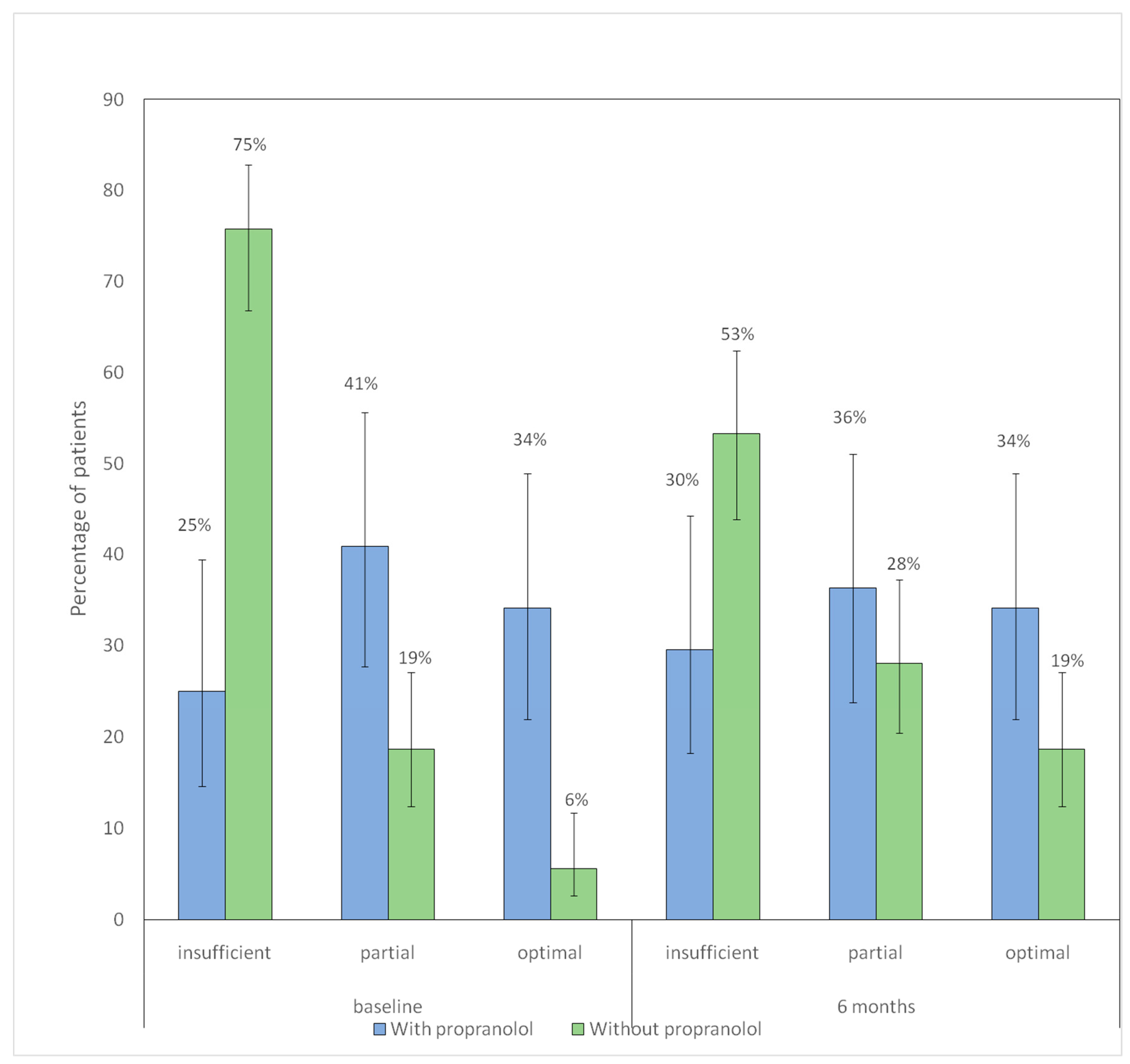

Nasal Care and Lubrication/Moisturizing

In the non-propranolol group, the distribution of adherence categories changed significantly between baseline and 6 months p < 0.001), showing a decrease in the proportion of patients with insufficient adherence and an increase in those with partial and optimal adherence. In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the propranolol group (p = 0.777).

Figure 4 shows distribution of hygienic–dietary adherence categories at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment.

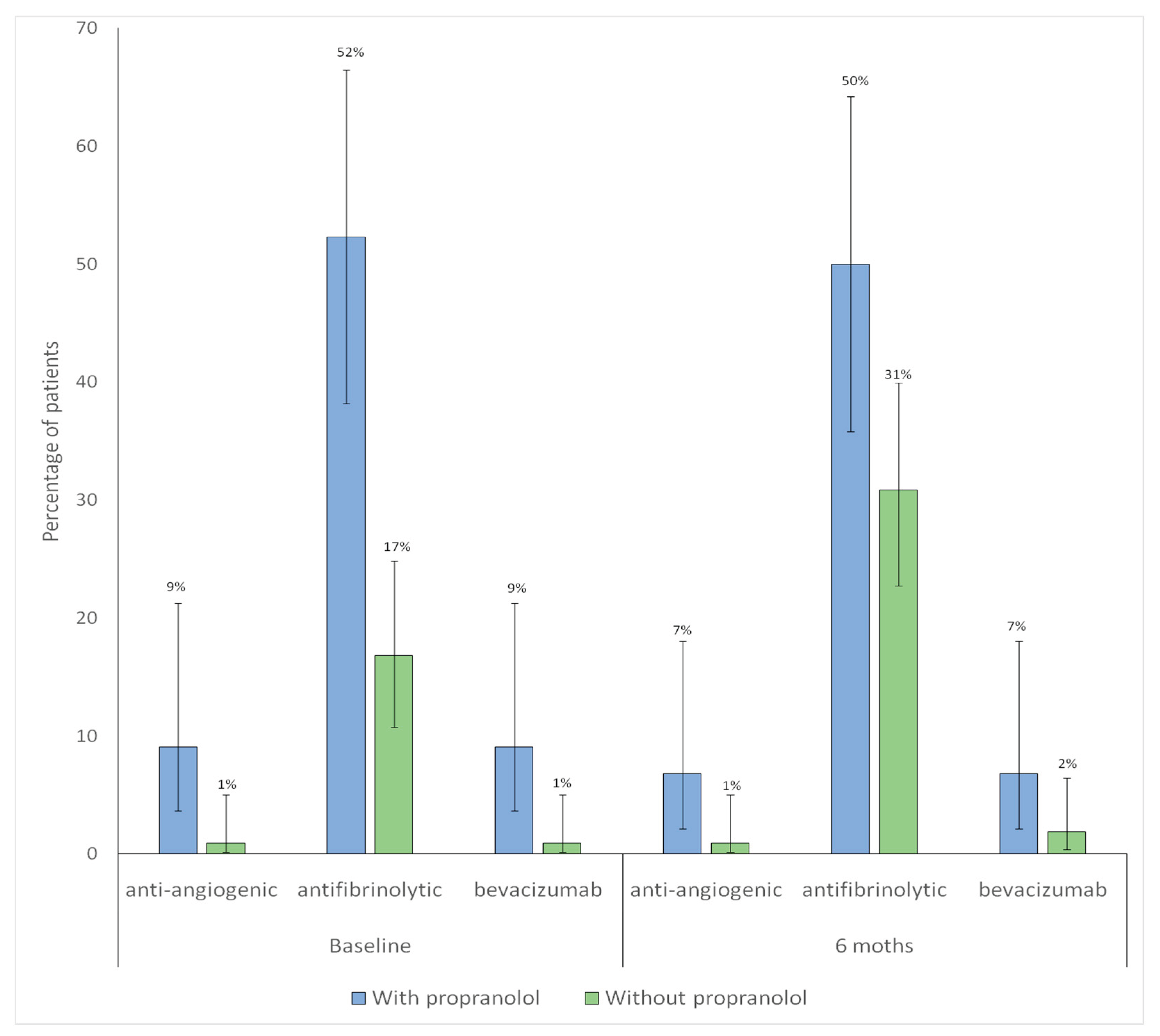

Pharmacological Treatments Other Than Propranolol

The proportion of patients receiving anti-angiogenic therapy remained unchanged between baseline and 6-month follow-up. With no significant differences in either group (without p = 1.00; with propranolol p = 1.00). A significant increase in antifibrinolytic use was observed among patients without propranolol (p = 0.007), whereas no significant change was detected in those treated with propranolol (p = 1.00)

The proportion of patients receiving bevacizumab therapy remained unchanged between baseline and 6-month follow-up. With no significant differences in either group (without propranolol p = 1.00; with propranolol p = 1.00).

Figure 5 shows distribution of pharmacological treatments other than propranolol at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment.

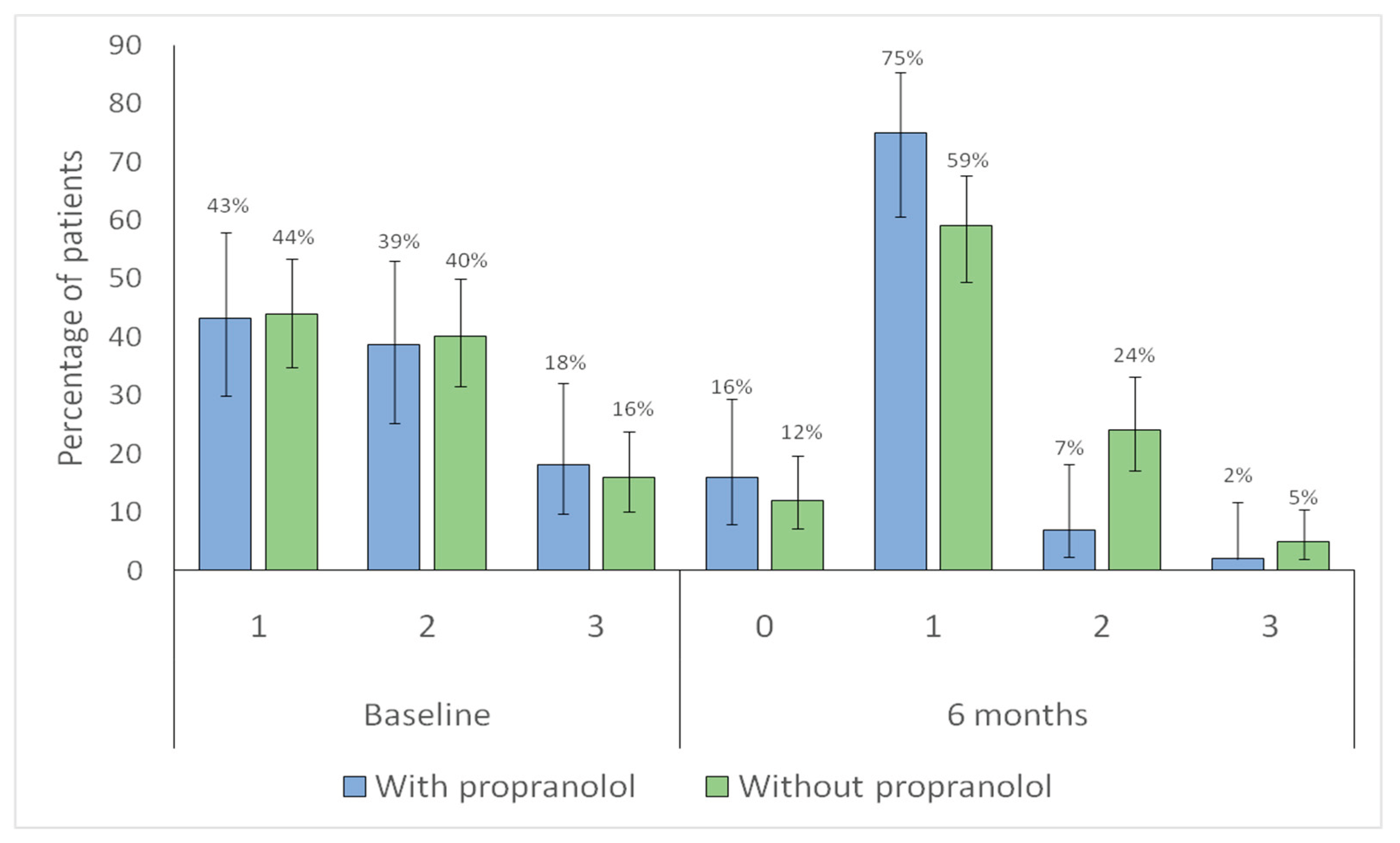

Association Between Propranolol Use and Improvement in Epistaxis

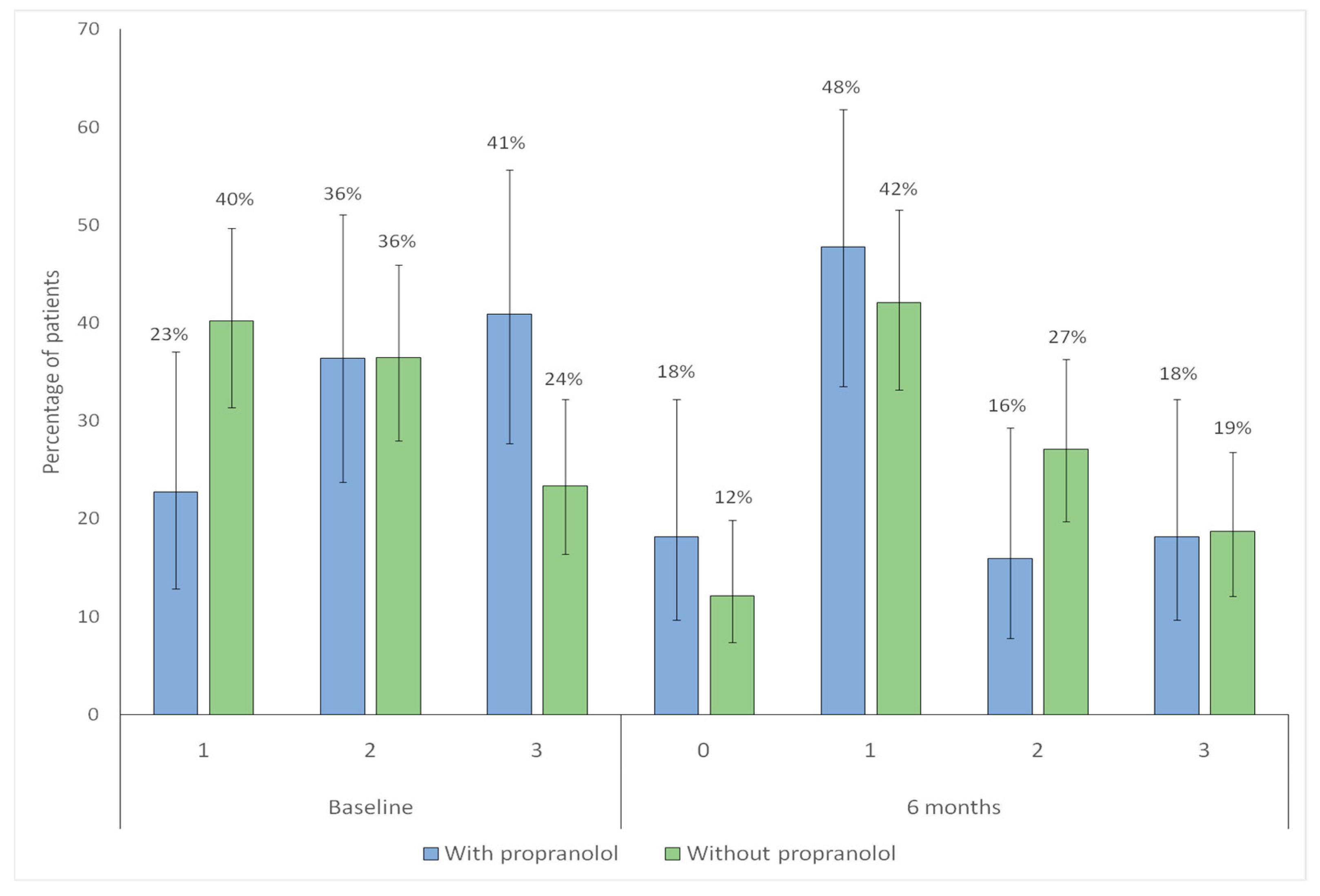

Both groups showed a significant shift toward lower category Sadick intensity scores at follow-up (with propranolol

p < 0.001; without propranolol

p < 0.001), indicating overall improvement (

Figure 6).

Significant changes were observed in both groups in Sadick sore frequency (with propranolol p = 0.001; without propranolol p = 0.002), indicating a shift toward lower frequency scores consistent with clinical improvement (

Figure 7).

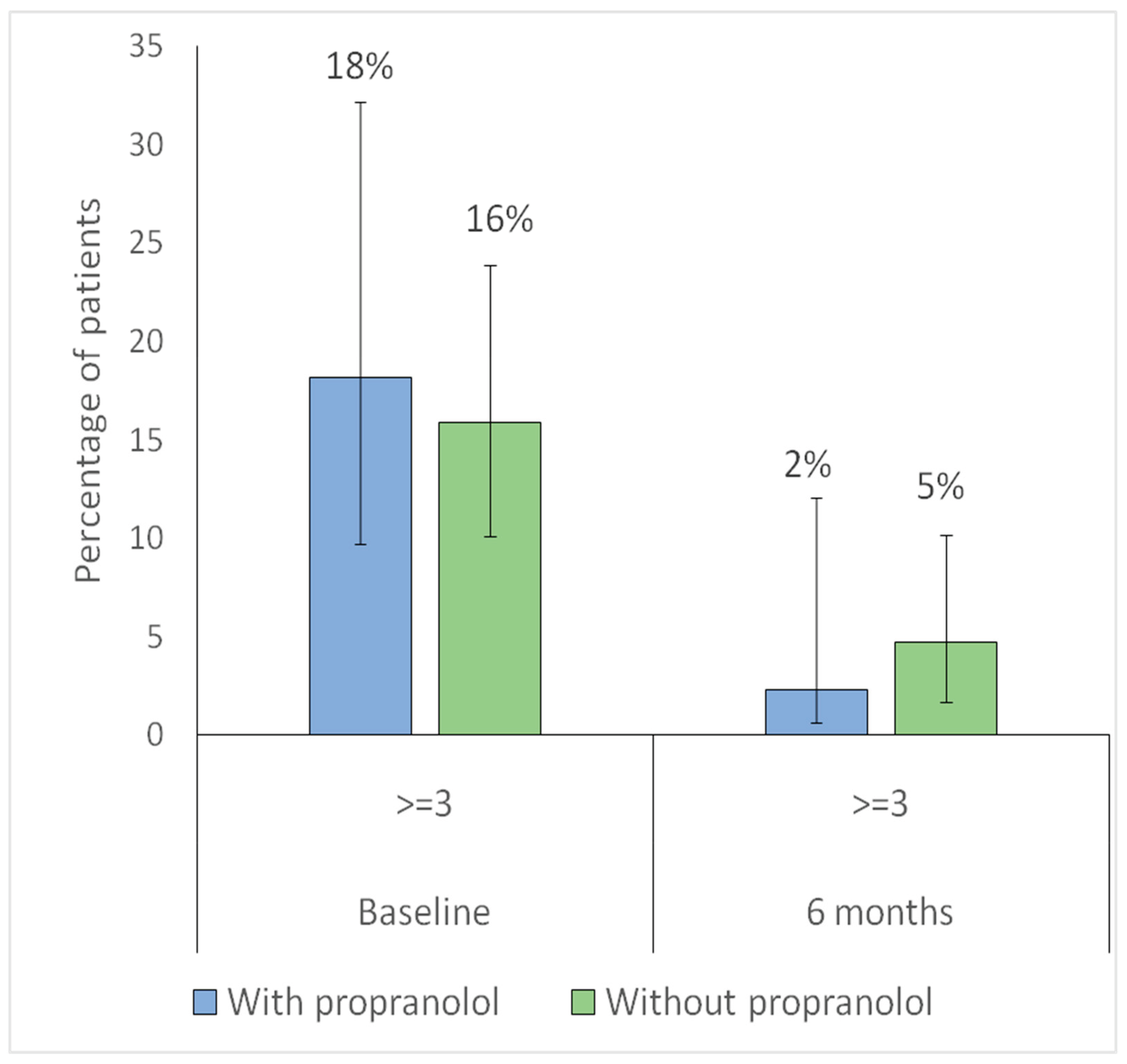

For further analysis, the Sadick scale was dichotomized into <3 (milder cases) versus ≥3 (severe bleeding). Regarding intensity, the proportion of patients with Sadick intensity ≥ 3 significantly decreased in both groups (with propranolol p = 0.023; without propranolol p = 0.014), indicating a reduction in the proportion of patients with higher-intensity epistaxis at 6 months (

Figure 8).

Regarding frequency, the proportion of patients with Sadick frequency ≥ 3 significantly decreased in the propranolol group (p = 0.044), while no significant change was observed in the non-propranolol group (p = 0.44), indicating a reduction in high-frequency epistaxis only among treated patients (

Figure 9).

Adjustment for Indication Bias

To account for potential indication bias, IPTW based on the propensity score was applied.

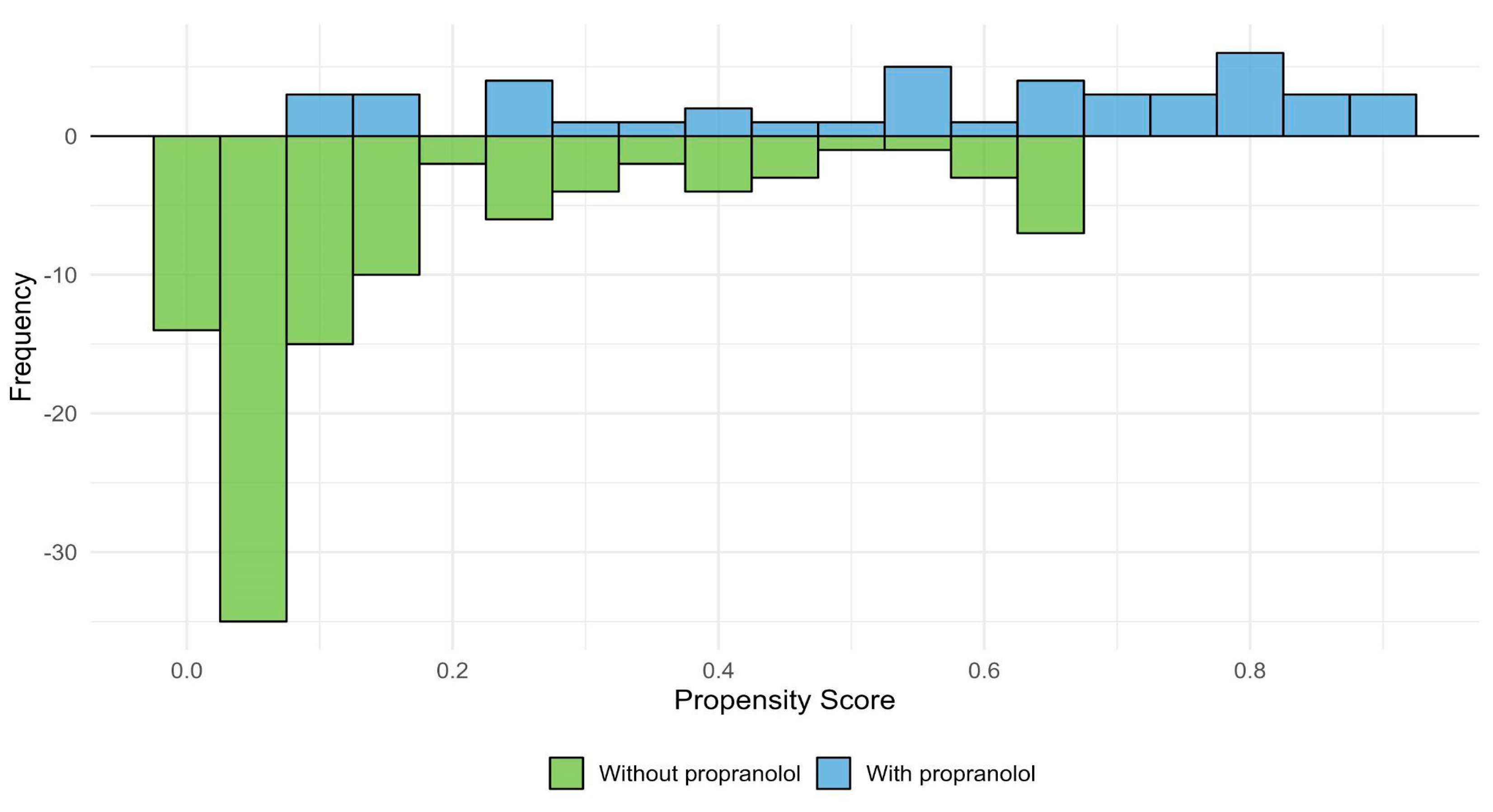

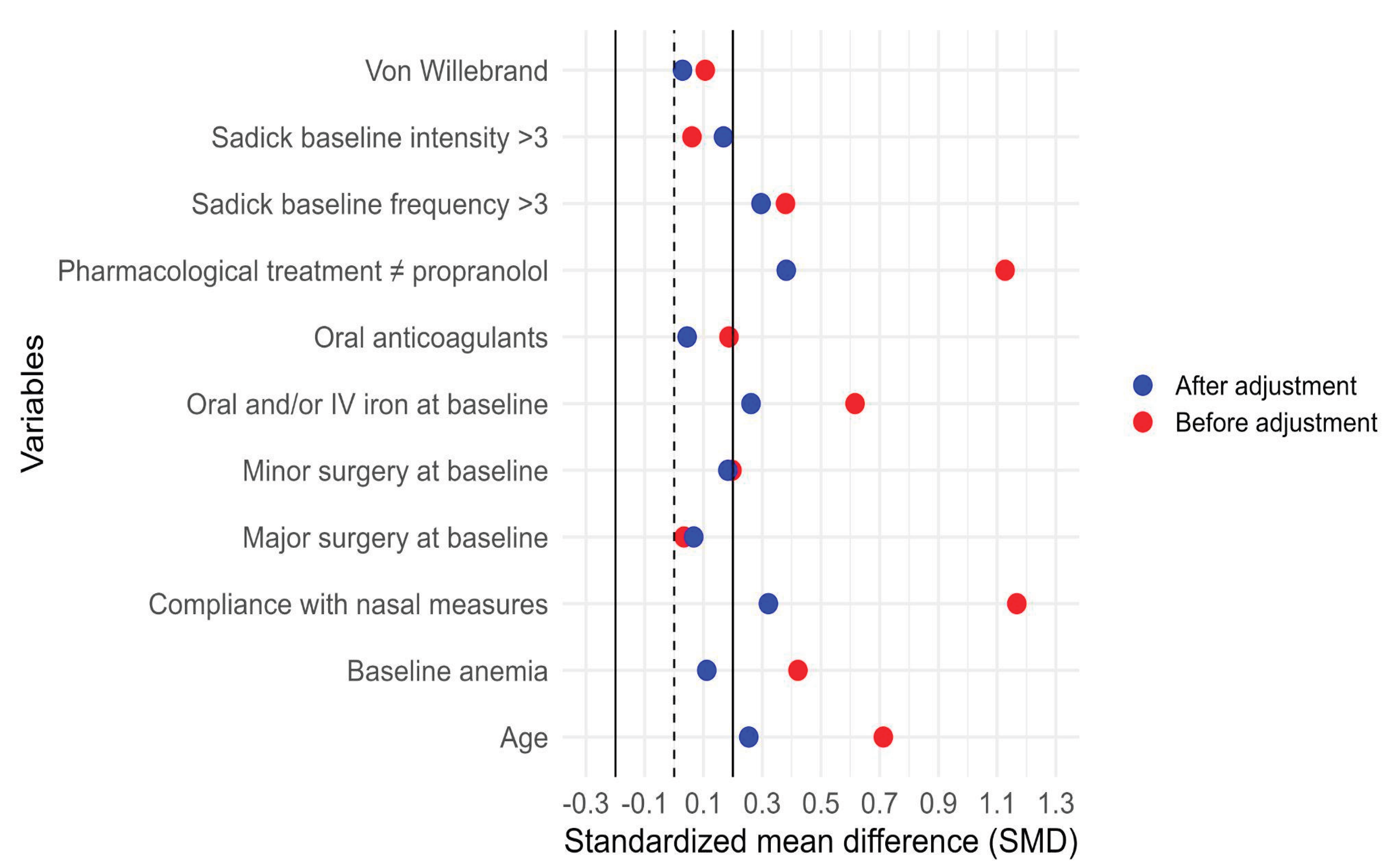

Figure 11 shows the distribution of estimated propensity scores for patients treated and not treated with propranolol, illustrating the region of common support between groups. Figure 12 presents the standardized mean differences (SMDs) for baseline covariates before and after weighting. After IPTW adjustment, all covariates achieved adequate balance (SMD < 0.1), indicating successful reduction of baseline differences between groups.

Figure 10.

Propensity score distribution and region of common support. Distribution of estimated propensity scores for patients treated with propranolol (blue) and without propranolol (green). The x-axis represents the estimated propensity score for each individual, and the y-axis represents the frequency of patients within each group. The overlapping area indicates the region of common support, where both groups share comparable probabilities of receiving propranolol.

Figure 10.

Propensity score distribution and region of common support. Distribution of estimated propensity scores for patients treated with propranolol (blue) and without propranolol (green). The x-axis represents the estimated propensity score for each individual, and the y-axis represents the frequency of patients within each group. The overlapping area indicates the region of common support, where both groups share comparable probabilities of receiving propranolol.

Figure 11.

Covariate balance before and after inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). Standardized mean differences (SMDs) for baseline covariates before (red) and after (blue) IPTW adjustment. The vertical solid and dashed lines at 0 and ±0.1 represent thresholds for acceptable covariate balance. After weighting, all covariates retained in the final outcome model achieved SMD +-0.1, indicating adequate balance between propranolol and non-propranolol groups. Variables outside the SMD threshold were not used to construct the IPTW but were included as additional adjustment covariates when estimating the association between propranolol and the outcome.

Figure 11.

Covariate balance before and after inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). Standardized mean differences (SMDs) for baseline covariates before (red) and after (blue) IPTW adjustment. The vertical solid and dashed lines at 0 and ±0.1 represent thresholds for acceptable covariate balance. After weighting, all covariates retained in the final outcome model achieved SMD +-0.1, indicating adequate balance between propranolol and non-propranolol groups. Variables outside the SMD threshold were not used to construct the IPTW but were included as additional adjustment covariates when estimating the association between propranolol and the outcome.

Improvement in epistaxis, defined as a reduction of at least one point in any category of the Sadick scale, was observed in 34 of 44 patients treated with propranolol (77%) compared with 63 of 107 patients without propranolol (58.9%). No significant association was found between propranolol use and overall improvement in bleeding, either in the unadjusted analysis or after adjusting for indication bias using IPTW (

Table 4).

Cr OR, Crude odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Adj OR, Adjusted odds ratioModel adjusted for propranolol use, age, oral and/or intravenous iron supplementation, baseline minor surgery, nasal lubrication measures, any treatment other than propranolol, baseline Sadick frequency ≥3, and propensity score using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW).

IPTW: Von Willebrand disease, Sadick intensity ≥3, baseline major surgery, anticoagulant therapy

When outcomes were analyzed separately, 26 of 44 patients treated with propranolol (59.1%) showed improvement in bleeding intensity, compared with 53 of 107 patients in the non-propranolol group (49.5%). Regarding frequency, improvement was observed in 27 of 44 patients treated with propranolol (61.4%) versus 38 of 107 patients without propranolol (35.5%). Stratified analysis of the Sadick scale categories confirmed a significant association between propranolol use and improvement in frequency, both in crude and adjusted analyses, whereas no association was found for intensity (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

This study suggests that propranolol is useful for the treatment of epistaxis in HHT patients, particularly through the reduction of bleeding frequency and probably also intensity. Therapeutic strategies in HHT remain limited. Although in recent years relevant advances have been made in understanding its pathophysiological mechanisms, current management is mainly based on the repurposing of drugs approved for other indications that can modulate biological processes involved in the disease. Some of these include hormonal analogues and antiangiogenic agents, some designated as orphan drugs in Europe, such as raloxifene and bazedoxifene [

27,

28] . Propranolol has emerged as a promising candidate, although clinical evidence is still limited due to heterogeneity in its pharmacological administration, low statistical power, and study design [

19,

27,

29]. The rationale for propranolol repurposing is based on multiple biological properties: antiangiogenic action, modulation of signaling pathways, vasoconstrictive effect, and usefulness in other common HHT clinical manifestations (migraines, arrhythmias, portal hypertension) or comorbidities such as arterial hypertension. Propranolol is a safe, inexpensive, and widely used drug, although its beta-blocking effect could compromise compensatory mechanisms in severe hemorrhage, which explains the preference of some groups for topical alternatives such as timolol [

29]. However, experience in infantile hemangioma suggests that antiangiogenic effects are mainly achieved with systemic administration [

18].

In this study, 151 patients were included from a total of 510 initially evaluated. Only significant differences in age and visceral malformations were observed, both more frequent in the included patients compared to the excluded individuals. This suggests a study population with greater clinical severity, more comorbidities, and closer contact with the healthcare system, making the results generalizable to older and more complex HHT patients. Among those treated with propranolol, characteristics of greater severity, higher drug use, particularly antifibrinolytics, and better adherence to nasal care measures were observed, likely reflecting greater interaction with HHT specialists. These baseline differences are expected in an observational study, unlike randomized clinical trials with propranolol or topical timolol, in which no significant discrepancies between groups were found [

23,

30,

31]. Regarding gastrointestinal bleeding, no baseline differences were observed between groups, although the analysis was limited by the absence of endoscopic studies in several patients, particularly those under 50 years of age.

To the best of our knowledge, no clinical trial has evaluated the efficacy of propranolol in this context, whereas studies on gastrointestinal bleeding in HHT are limited, probably due to the complexity of its assessment. Differences in the therapeutic response to other drugs have also been observed: tranexamic acid has not shown efficacy in this scenario [

13], while pazopanib or bevacizumab appear more effective for gastrointestinal than for nasal bleeding [

32,

33,

34], likely reflecting variations in the extent, localization, and biological microenvironment of telangiectasias.

Hemoglobin levels and their variations were considered as indirect indicators of bleeding. Since hemoglobin depends largely on iron levels, and these on the balance between intake and losses, an additional variable was included to account for variations in iron supplementation, both oral and intravenous, though dietary iron intake could not be considered. No statistically significant variations in hemoglobin levels were observed in either group, despite a noticeable increase in propranolol-treated patients. Notably, patients in the propranolol group started with lower hemoglobin levels compared with the other group. This may indirectly indicate that they were more severe bleeders with deeper iron deficits.

Within-group comparisons between baseline and 6-month evaluations provided additional insight into the clinical evolution of patients. Iron supplementation requirements remained stable over time, whereas antifibrinolytic use increased significantly among patients without propranolol, indicating a need for additional pharmacological support in that group. Adherence to nasal care showed improvement among non-treated patients and stability among propranolol users. Finally, when analyzing the Sadick scale, both groups exhibited a significant reduction in intensity scores, while only patients treated with propranolol showed a significant decrease in high-frequency epistaxis. Altogether, these trends highlight that while general supportive measures benefit all patients, propranolol appears to specifically reduce the recurrence of bleeding episodes.

From a clinical perspective, patients with greater compromise are generally those requiring more treatments. Conversely, those experiencing less frequent and/or less intense bleeding tend to respond better to iron supplementation, showing an increase in hemoglobin. In the study by Ichimura et al. (2016) with topical timolol in patients undergoing septodermoplasty, stabilization of hemoglobin with cessation of transfusion requirements was reported [

35]. Using topical timolol in patients treated with laser, this was not observed in the TIM-HHT trial, in which no changes in hemoglobin or other iron-related parameters were found with the intervention [

30]. In a pilot retrospective study with propranolol gel, the authors reported a significant increase in hemoglobin levels after 12 weeks of treatment in the intervention group, although this was not associated with a significant reduction in transfusion requirements [

36]. These findings were confirmed in a subsequent trial conducted by the same group with 1.5% propranolol gel in a larger cohort over 8 weeks [

31]. Dupuis-Girod and colleagues also did not observe modifications in hemoglobin levels in the randomized double-blind trial of topical timolol versus placebo [

37]. A recent small trial with oral propranolol, found a significant increase in hemoglobin after 3 months of treatment but not after six months [

24]. Hemoglobin improvement in treated patients is variable across studies. Although study designs and pharmacological formulations differ, hemoglobin modifications depend on multiple factors. Other drugs used in HHT, such as tranexamic acid or thalidomide, although significantly reducing bleeding, have not shown consistent hemoglobin increases, except for bevacizumab, in which EPO gene involvement may also play a role.

We also assessed changes in oral and/or intravenous iron supplementation at baseline and after six months. In line with hemoglobin levels, a slightly higher proportion of patients in the propranolol group increased iron requirements. Although intravenous iron often indicates more severe disease, it may also reflect intolerance to oral formulations, patient preference, accessibility, or cost. In HHT, where bleeding is chronic and unpredictable, iron therapy is rarely discontinued.

Regarding hygienic and lubrication measures, nasal care is the first-line therapy for epistaxis and strongly recommended in the Second International Guidelines for HHT [

13]. In our center, patients are instructed in writing on proper technique and products. Adherence was inconsistent overall, though higher among those not receiving propranolol. Patients treated with propranolol showed stable adherence, possibly reflecting greater disease severity, more frequent clinical follow-up, or reinforcement of recommendations. No previous studies of beta-blockers in HHT have assessed changes in nasal care. Importantly, some topical trials suggest potential benefits from the vehicle itself, such as saline or thermosensitive gels [

38].

Pharmacological treatments in HHT aim to compensate for haploinsufficiency, modulate angiogenesis, reduce inflammation, or optimize coagulation. They are often used in combination, as monotherapy rarely achieves control. We assessed changes in non-propranolol therapies during follow-up, grouping them into antifibrinolytics, antiangiogenics, and bevacizumab (considered separately given its stronger evidence). Fewer patients in the propranolol group required additional pharmacological treatment, suggesting that propranolol may reduce the need for other drugs to control epistaxis, although discontinuation due to adverse effects, lack of efficacy, accessibility, or patient preference may also account for this finding. Antifibrinolytic use increased only in the non-propranolol group, suggesting a synergistic role of propranolol with tranexamic acid. Consistent with prior studies [

39], tranexamic acid was effective mainly in reducing severity rather than frequency of bleeding, and in our practice remains the first-line agent after nasal care.

Regarding the primary outcome, propranolol was not significantly associated with overall improvement (frequency + intensity). However, patients receiving propranolol had an almost four-fold higher odds of improvement in frequency, with the lower CI close to 1 (OR ~4, 95% CI 0.9-5.6) [

40]. This trend aligns with the TIM-HHT trial, where timolol did not achieve significance but showed borderline improvements in bleeding scores [

41]. Of note, our follow-up of 6 months may capture more durable clinical benefit than the shorter periods assessed in topical studies.

Trials with topical propranolol gel in patients with moderate epistaxis (ESS ≥4) demonstrated significant reductions in bleeding, transfusion requirements, and hemoglobin improvement, although nasal inspection did not differ [

31,

36]. Similarly, our data suggest propranolol is particularly effective in more severe cases. Other trials with topical timolol reported improvements but failed to demonstrate superiority over placebo, while systemic propranolol has shown beneficial effects in both cardiovascular/neurological indications and bleeding parameters [

19]. A small trial compared oral propranolol (10 patients) versus placebo (5 patients). The authors did not observe morphological differences in the nasal telangiectasias, although they were able to estimate a reduction in epistaxis severity (ESS) in the propranolol arm after 3 months of treatment. However, the study presents notable limitations in both methodology and patient recruitment [

24].

Mechanistically, propranolol may reduce shear stress, stabilize telangiectasias, and exert vasoconstrictive and antiangiogenic effects, thereby lowering the number of fragile lesions [

42,

43]. Its catecholamine-blocking action may also decrease stress-induced epistaxis, the most frequent trigger in our series. Conversely, PAI-1 inhibition may explain the limited effect on intensity, highlighting a complementary role for tranexamic acid [

44].

In our study, most patients received low propranolol doses, precluding dose-response analysis. Although preclinical data support dose-dependency, our results suggest that even low doses may reduce bleeding frequency. A small randomised trial with oral propranolol reports benefits with 80 mg per day [

24]. No standardized dosing exists for HHT-related epistaxis; extrapolation from infantile hemangioma (2–3 mg/kg/day) may be reasonable, though further trials are required [

45].

Adverse effects were reported in six patients (hypotension, insomnia, or mood changes). As with other beta-blocker studies, events were mild, and none were severe [

24,

37]. While topical timolol has been associated with systemic absorption and hemodynamic effects [

38,

46], propranolol was generally well tolerated. Thus, systemic propranolol appears safer and more justified than topical formulations.

This study has limitations: first, fewer patients than expected, although baseline differences were limited to age and visceral AVMs, without affecting baseline epistaxis severity; the inability to apply ESS in most patients, requiring dichotomization of the Sadick scale, which reduced statistical power but enabled separate evaluation of bleeding frequency and intensity; there were limited genetic data, precluding genotype-specific analyses; besides, insufficient information to assess gastrointestinal bleeding response; and lack of detailed dose–response analysis. The strengths of the study include: it represents the largest cohort reported to date, overcoming the methodological limitations of the few prior studies, which lacked placebo or untreated control groups or a very small number of patients included. Although observational studies provide a lower level of evidence compared with randomized clinical trials, a major strength of our work is its real-world design, where follow-up frequency, treatment adherence, and patient behavior were not controlled, better reflecting clinical practice. The 6-month follow-up allowed evaluation of both initial response and its maintenance. Analyses were adjusted for relevant clinical variables and indication bias using IPTW.

Figure 1.

Patient flowchart from the Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) Registry (December 2019).

Figure 1.

Patient flowchart from the Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) Registry (December 2019).

Figure 2.

Distribution of hemoglobin levels (g/dL) in patients treated with and without propranolol at baseline and after 6 months of follow-up. Boxplots show the median (central line), interquartile range (box), and extreme values (whiskers). Within-group comparisons between time points were performed using paired tests (p-values indicated in the graph). With propranolol baseline median 11 (RIC 9.5-12.8) 6 month median 12.2 (RIC 9.2-13) Without propranolol baseline median 12 (RIC 10.8-13.8) 6 month median 12.7 (RIC 11-13.9).

Figure 2.

Distribution of hemoglobin levels (g/dL) in patients treated with and without propranolol at baseline and after 6 months of follow-up. Boxplots show the median (central line), interquartile range (box), and extreme values (whiskers). Within-group comparisons between time points were performed using paired tests (p-values indicated in the graph). With propranolol baseline median 11 (RIC 9.5-12.8) 6 month median 12.2 (RIC 9.2-13) Without propranolol baseline median 12 (RIC 10.8-13.8) 6 month median 12.7 (RIC 11-13.9).

Figure 3.

Distribution of iron supplementation at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients receiving each type of iron supplementation in each group (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines denote 95% confidence intervals. The numbers displayed above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients.

Figure 3.

Distribution of iron supplementation at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients receiving each type of iron supplementation in each group (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines denote 95% confidence intervals. The numbers displayed above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients.

Figure 4.

Distribution of hygienic–dietary adherence categories at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients receiving each type of iron supplementation in each group (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines denote 95% confidence intervals. The numbers displayed above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients.

Figure 4.

Distribution of hygienic–dietary adherence categories at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients receiving each type of iron supplementation in each group (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines denote 95% confidence intervals. The numbers displayed above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients.

Figure 5.

Distribution of pharmacological treatments (antiangiogenic, antifibrinolytic and bevacizumab) other than propranolol at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients receiving anti-angiogenic, antifibrinolytic, or bevacizumab therapy in each group (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. The numbers displayed above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients,.

Figure 5.

Distribution of pharmacological treatments (antiangiogenic, antifibrinolytic and bevacizumab) other than propranolol at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients receiving anti-angiogenic, antifibrinolytic, or bevacizumab therapy in each group (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. The numbers displayed above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients,.

Figure 6.

Distribution of Sadick intensity scores categories at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients within each Sadick intensity category at baseline (1–3) and at 6-month follow-up (0–3), according to propranolol treatment (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Numbers above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients in each category.

Figure 6.

Distribution of Sadick intensity scores categories at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients within each Sadick intensity category at baseline (1–3) and at 6-month follow-up (0–3), according to propranolol treatment (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Numbers above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients in each category.

Figure 7.

Distribution of Sadick frequency scores categories at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients within each Sadick frequency category at baseline (1–3) and at 6-month follow-up (0–3), according to propranolol treatment (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Numbers above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients in each category.

Figure 7.

Distribution of Sadick frequency scores categories at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients within each Sadick frequency category at baseline (1–3) and at 6-month follow-up (0–3), according to propranolol treatment (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Numbers above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients in each category.

Figure 8.

Distribution of Sadick intensity scores >=3 versus <3 at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients with Sadick intensity score ≥ 3 at baseline and at 6-month follow-up, according to propranolol treatment (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Numbers above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients in each group.

Figure 8.

Distribution of Sadick intensity scores >=3 versus <3 at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients with Sadick intensity score ≥ 3 at baseline and at 6-month follow-up, according to propranolol treatment (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Numbers above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients in each group.

Figure 9.

Distribution of Sadick frequency scores >=3 versus <3 at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients with Sadick frequency score ≥ 3 at baseline and at 6-month follow-up, according to propranolol treatment (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Numbers above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients in each group.

Figure 9.

Distribution of Sadick frequency scores >=3 versus <3 at baseline and at 6-month follow-up according to propranolol treatment. Bars represent the proportion of patients with Sadick frequency score ≥ 3 at baseline and at 6-month follow-up, according to propranolol treatment (blue: with propranolol; green: without propranolol). Vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Numbers above each bar correspond to the percentage of patients in each group.

Table 1.

Sadick-Bergler Scale.

Table 1.

Sadick-Bergler Scale.

| Grade of Sadick-Bergler |

Frequency of Bleeding |

Intensity of Bleeding |

| Grade 1 |

Less than once per week |

Slight stains on handkerchief |

| Grade 2 |

Several times per week |

Soaked handkerchief |

| Grade 3 |

More than once per day |

Bowl or equivalent container necessary |

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of excluded and included patients.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of excluded and included patients.

| |

Excluded

(n=201)

|

Included

(n=151)

|

p value |

| Male sex, n (%) |

77 (38.3) |

56 (37.1) |

0.902 |

| Median age (IQR) |

43 (34–58) |

50 (38.5–64) |

0.003 |

| AVMs, n (%) |

106 (52.7) |

124 (82.1) |

<0.001 |

Sadick scale – intensity* n (%)

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

115 (57.2) |

84 (55.6) |

|

| 2 |

63 (31.3) |

50 (33.1) |

0.939 |

| 3 |

23 (11.4) |

17 (11.3) |

|

Sadick scale – frequency* n (%)

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

102 (50.7) |

70 (46.4) |

|

| 2 |

46 (22.9) |

25 (29.8) |

0.341 |

| 3 |

53 (26.4) |

36 (23.8) |

|

| Sadick scale** |

|

|

|

| Intensity ≥3 |

53 (26.4) |

36 (23.8) |

0.677 |

| Frequency ≥3 |

23 (11.4) |

17 (11.3) |

0.999 |

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without propranolol treatment.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without propranolol treatment.

| Characteristic |

Without propranolol (n=107) |

With propranolol

(n=44)

|

p value↯

|

| Median age (IQR) |

47 (34-62.5) |

62 (48.7-68). |

<0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) |

39 (36.4) |

17 (38.6) |

0.946 |

| HMO, n (%) |

19 (17.8) |

3 (6.8) |

0.140 |

| Argentine nationality, n (%) |

102 (95.3) |

43 (97.7) |

0.820 |

| Vascular malformations, n (%) |

|

| CNS involvement |

22 (20.6) |

14 (31.8) |

0.206 |

| Hepatic involvement |

72 (67.3) |

38 (86.4) |

0.028 |

| Pulmonary involvement |

47 (43.9) |

17 (38.6) |

0.677 |

| Digestive involvement |

13 (12.1) |

12 (27.3) |

0.042 |

| Any visceral involvement✝ |

92 (86) |

39 (88.6) |

0.862 |

|

Hemorrhagic conditions or comorbidities, n (%)⇉** |

|

| Von Willebrand disease |

1 (0.9) |

1 (2.3) |

0.999 |

| Anticoagulant use* |

3 (2.8) |

3 (6.8) |

0.491 |

| Specific treatments for HHT other than propranolol, n (%) |

|

| Antifibrinolytics |

18 (16.8) |

23 (52.3) |

<0.001 |

| Hormonal therapy or analogs |

5 (4.7) |

8 (18.2) |

0.018 |

| Bevacizumab |

1 (0.9) |

4 (9.1) |

0.041 |

| Other antiangiogenic agentsұ |

1 (0.9) |

4 (9.1) |

0.041 |

| At least one non-propranolol drug↡ |

25 (23.4) |

32 (72.7) |

<0.001 |

| Compliance with nasal hygiene and lubrication measures, n (%)* |

|

| Insufficiente |

81 (75.7) |

11 (25) |

|

| Partial compliance |

20 (18.7) |

18 (40.9) |

<0.001 |

| Optimal compliance |

6 (5.6) |

15 (34.1) |

|

| Non-compliance with nasal hygiene/lubrication⇟** |

81 (88) |

11 (11.9) |

0.001 |

| Baseline surgical or ablative treatments, n (%) |

|

| Major surgery |

3 (2.8) |

1 (2.3) |

0.999 |

| Young’s procedure |

0 |

2 (4.5) |

0.151 |

| Minor surgery |

10 (9.3) |

7 (15.9) |

0.381 |

| Iron support and/or transfusions, n (%) |

|

| Oral Iron |

24 (22.4) |

18 (40.9) |

0.035 |

| Intravenous Iron |

17 (15.9) |

11 (25) |

0.281 |

| Oral and/or intravenous iron. |

34 (31.8) |

27 (61.4) |

0.001 |

| RBC transfusions |

5 (4.7) |

1 (2.3) |

0.820 |

| Baseline hemoglobin |

|

|

|

| Mean hemoglobin (SD) |

12.1 (2.2) |

11.1 (2.1) |

0.007 |

| Anemia#, n (%) |

51 (47.7) |

30 (68.2) |

0.034 |

| Sadick scale – intensity* n (%) |

|

|

|

| 1 |

47(43.9) |

19 (43.2) |

|

| 2 |

43 (40.2) |

17 (38.6) |

0.941 |

| 3 |

17 (15.9) |

8 (18.2) |

|

| Sadick scale – frequency*n (%) |

|

|

|

| 1 |

43 (40.2) |

10 (22.7) |

|

| 2 |

39 (36.4) |

16 (36.4) |

0.048 |

| 3 |

25 (23.4) |

18 (40.9) |

|

| Sadick scale** n (%) |

|

|

|

| Sadick Intensity >=3 |

17 (15.9) |

8 (18.2) |

0.917 |

| |

|

|

|

| Sadick Frequency >=3 |

25 (23.4) |

18 (40.9) |

0.049 |

| Digestive bleeding baseline (%) |

12 (25) |

8 (25) |

0.993 |

| Digestive bleeding at 6 months& n (%) |

9 (18.8) |

8 (25) |

0.516 |

Table 4.

Association Between Propranolol Administration and Improvement of Epistaxis.

Table 4.

Association Between Propranolol Administration and Improvement of Epistaxis.

| Epistaxis improvement |

Cr OR (IC 95%) |

p value |

Adj OR* (CI 95%) |

p value |

| Without propranolol |

reference |

|

|

|

| With propranolol |

2.2 (0.9-5.6) |

0.079 |

2.8 (0.9-8.6) |

0.083 |

Table 5.

Association between propranolol administration and epistaxis improvement in intensity of frequency.

Table 5.

Association between propranolol administration and epistaxis improvement in intensity of frequency.

| Epistaxis improvement |

Cr OR (CI 95%) |

p value |

Adj OR* (CI 95%) |

p value |

| Intensity |

|

|

|

|

| Without propranolol |

reference |

|

|

|

| With propranolol |

1.5 (0.7-2.9) |

0.286 |

1.9 (0.7-5.2) |

0.181 |

| Frequency |

|

|

|

|

| Without propranolol |

reference |

|

|

|

| With propranolol |

2.9 (1.4-5.9) |

0.004 |

3.8 (1.3-11.2) |

0.016 |