Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

10 November 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Blood Collection, Processing, and Storage

2.3. Biochemical and Hematological Analyses

2.4. Cardiovascular, Inflammatory, and Oxidative Biomarkers

2.5. Lp-PLA₂ (PLA2G7) mRNA Expression by RT-qPCR

| Title 1 | Title 2 | Title 3 |

| IL-6 | 5'- CAC CGG GAA CGA AAG AGA AG -3' 5'- GGG CGG CTA CAT CTT TGG AAT C -3 |

For Rev |

| TNF-α |

5'- AAG AAT TCA AAC TGG GGC CT -3' 5'- GAG GAA GGC CTA AGG TCC AC -3' |

For Rev |

| Lp-PLA₂ | 5'- CCA CCC AAA TTG CAT GTG C -3' 5'- GCC AGT CAA AAG GAT AAA CCA CA -3' |

For Rev |

| GAPDH | 5'- CAA GGT CAT CCA TGA CAA CTT TG -3' 5'- GTC CAC CAC CCT GTT GCT GTA G -3' |

For Rev |

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Analysis Sets

3.2. Baseline Clinical, Biochemical and Hematological Characteristics

3.3. Inflammatory and Oxidative Biomarkers

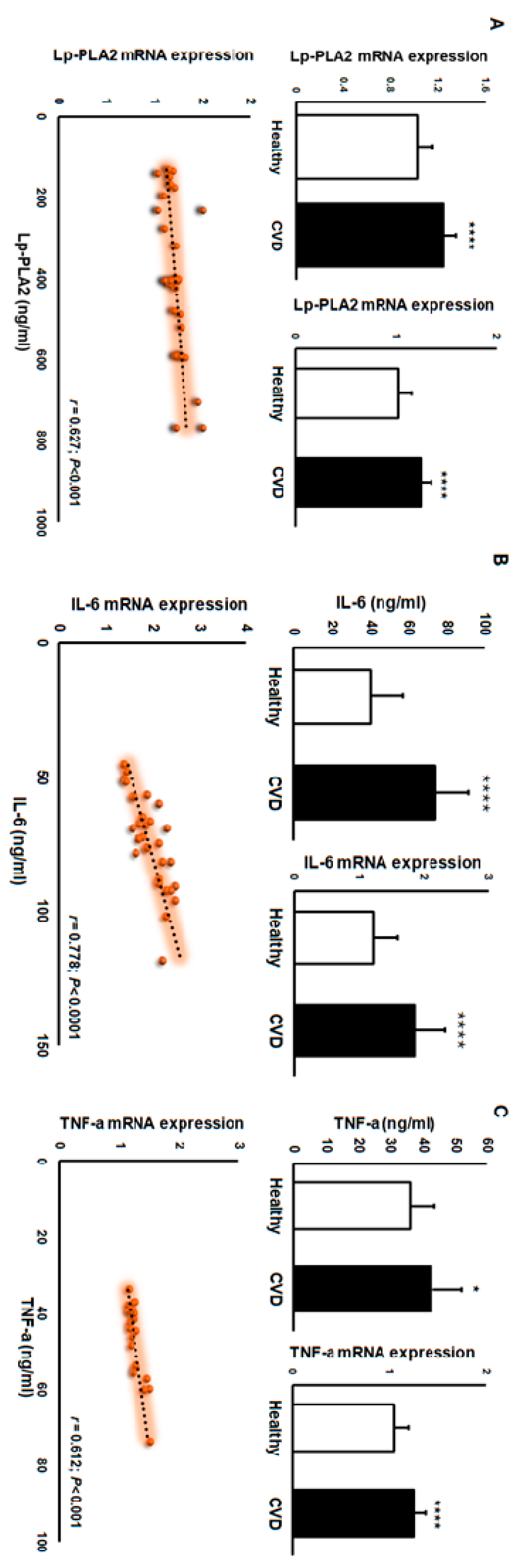

3.4. Paired Protein–mRNA Analyses

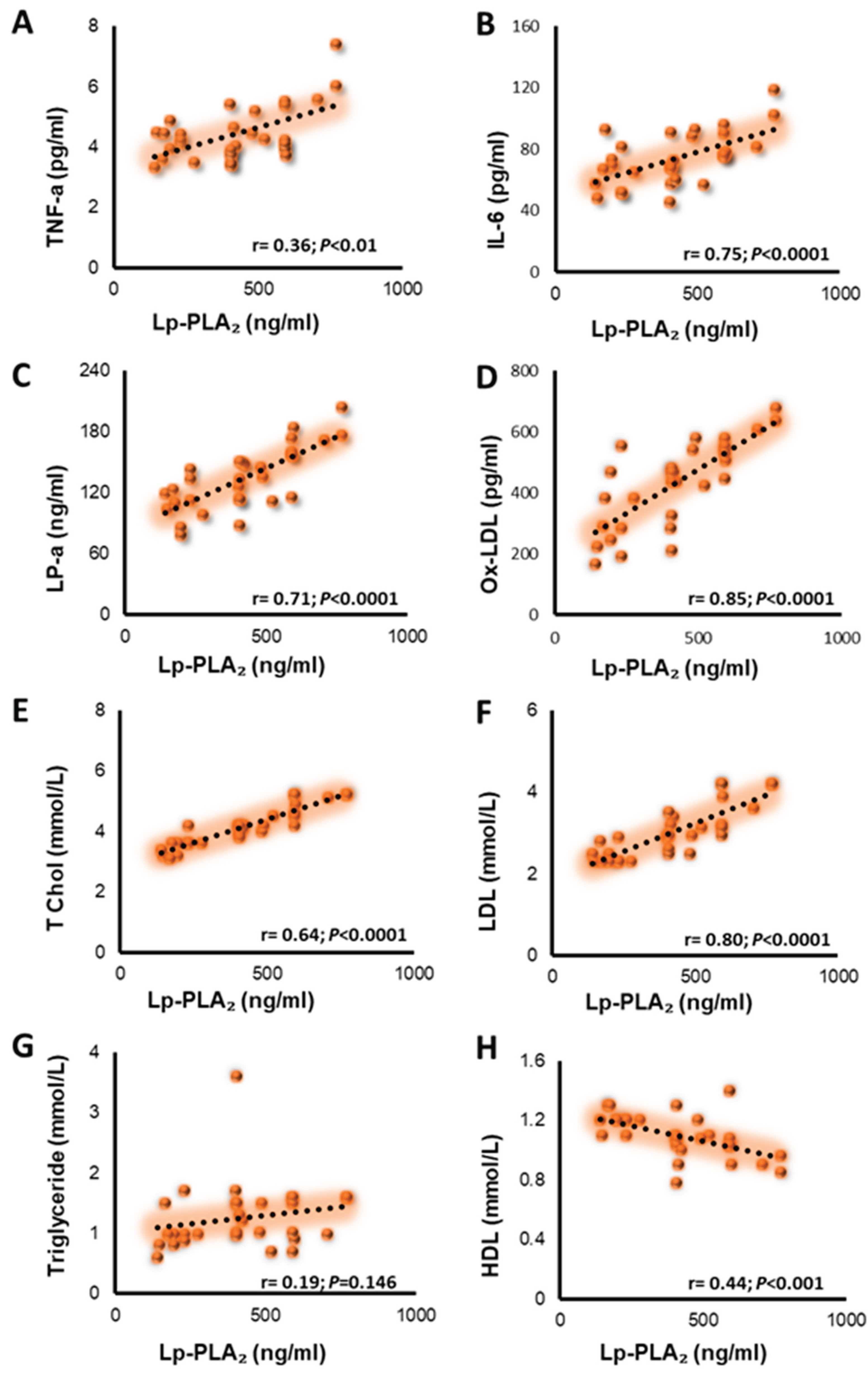

3.5. Associations Between Lp-PLA2 Concentration and Circulating Lipid Profiles, Inflammatory, and Oxidative Biomarkers

3.6. Discrimination of CVD from Healthy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) Fact Sheet. 31 Jul 2025.

- Rosenson RS, Stafforini DM. Lipoprotein-Associated and Secreted Phospholipases A₂ in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2011;124:2749–2769.

- Tselepis AD, et al. Pathophysiological Role and Clinical Significance of Lp-PLA₂ bound to LDL and HDL. Curr Med Chem. 2014;20(40):6256–6269.

- O’Donoghue M, et al. Lp-PLA₂ in Acute Coronary Syndrome: distribution across lipoprotein classes. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(10):1256–1262.

- The Lp-PLA₂ Studies Collaboration. Meta-analysis of observational studies of Lp-PLA₂ mass/activity and CVD risk. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(1):3–11.

- The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Lp-PLA₂ and risk of coronary disease and stroke: collaborative analysis of 32 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375:1536–1544.

- The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Lp-PLA₂ and risk of coronary disease and stroke: collaborative analysis of 32 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375:1536–1544.

- Chaudhary R, et al. Biochemical differences in the mass vs activity tests of Lp-PLA₂. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;471:32–37.

- Kolodgie FD, et al. Lp-PLA₂ protein expression in human coronary atheroma: association with high-risk lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(7):e164–e171.

- The STABILITY Investigators. Darapladib for preventing ischemic events in stable CHD. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1702–1711.

- O’Donoghue ML, et al. Effect of darapladib on major coronary events after ACS (SOLID-TIMI 52). JAMA. 2014;312(10):1006–1015.

- Holmes MV, Talmud PJ. Deciphering the causal role of sPLA₂s and Lp-PLA₂ in CHD (Mendelian randomization). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2281–2289.

- Patel RS, et al. Carriage of the V279F null allele of PLA2G7 and coronary risk in East Asians. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18208.

- Wang L, et al. Mechanisms of lysophosphatidylcholine in atherosclerosis. Life Sci. 2020;247:117443.

- Ismaeel S, Qadri A. ATP release drives inflammation with lysophosphatidylcholine. ImmunoHorizons. 2021;5(4):219–233.

- Luigi M, et al. Role of free fatty acids in endothelial dysfunction. J Biomed Sci. 2017;24:50.

- van der Valk FM, et al. Oxidized phospholipids on Lp(a) elicit arterial wall inflammation in humans. Circulation. 2016;134:611–624.

- Tsimikas S, et al. Oxidized phospholipid modification of Lp(a): epidemiology, genetics, and pathophysiology. Atherosclerosis. 2022;349:76–86.

- Packard CJ, Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from vascular biology to biomarker discovery and risk prediction. Clin Chem. 2008;54(1):24–38.

- Hansson GK, Hermansson A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(3):204–212.

- Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473(7347):317–325.

- Ridker PM, Luscher TF. Anti-inflammatory therapies for cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(27):1782–1791.

- Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115–126.

- Ridker PM, et al. Interleukin-6 signaling and the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2018;269:203–209.

- Kishimoto T. IL-6: from its discovery to clinical applications. Int Immunol. 2010;22(5):347–352.

- Tzoulaki I, Murray GD, Lee AJ, Rumley A, Lowe GD, Fowkes FG. Inflammatory markers and the risk of coronary heart disease: prospective study and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(22):2743–2749.

- Macphee CH, Moores KE, Boyd HF, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase, generates two bioactive products during the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein. Biochem J. 1999;338:479–487.

- Wilensky RL, et al. Inhibition of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 reduces complex coronary atherosclerotic plaque development. Nat Med. 2008;14(10):1059–1066.

- Tellis CC, Tselepis AD. The role of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis may depend on its lipoprotein carrier in plasma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791(5):327–338.

- Zalewski A, Macphee C. Role of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3380–3387.

- Tsimikas S, et al. Lipoprotein(a): novel target and emerging biomarker in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(2):177–192.

- Mehta JL, Chen J, Hermonat PL, Romeo F, Novelli G. Lectin-like, oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1): a critical player in the development of atherosclerosis and related disorders. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69(1):36–45.

- Bergmark C, Dewan A, Orsoni A, et al. A novel function of lipoprotein(a) as a preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(10):2230–2239.

- Tabas I, Garcia-Cardena G, Owens GK. Recent insights into the cellular biology of atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol. 2015;209(1):13–22.

- Libby P, Buring JE, Badimon L, et al. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: report from a scientific session. Atherosclerosis. 2019;283:91–100.

- Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Cytokines in atherosclerosis: pathogenic and regulatory pathways. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(2):515–581.

- Monaco C, Andreakos E, Kiriakidis S, et al. Canonical pathway of nuclear factor kappaB activation selectively regulates proinflammatory and prothrombotic responses in human atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(15):5634–5639.

- White HD, Held C, Stewart R, et al. Darapladib for preventing ischemic events in stable coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1702–1711.

- O’Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, White HD, et al. Effect of darapladib on major coronary events after an acute coronary syndrome: the SOLID-TIMI 52 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(10):1006–1015.

- Packard CJ, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 as an independent predictor of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(16):1148–1155.

- Mallat Z, Lambeau G, Tedgui A. Lipoprotein-associated and secreted phospholipases A2 in cardiovascular disease: roles as biological effectors and biomarkers. Circulation. 2010;122(21):2183–2200.

- Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Hamm CW, et al. Clinical outcomes with Lp-PLA2 inhibition after acute coronary syndromes. Atherosclerosis. 2019;286:1–9.

- Sabatine MS, et al. Lipid, inflammatory, and metabolic biomarkers and the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2012;125(4):450–458.

| Healthy | CVD | P-value | |||||||

| Age | 53+14 | 55+10 | |||||||

| BMI | 26+1 | 29+5 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Hb (g/dL) | 14+1 | 14+3 | |||||||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.8+1.5 | 6.8+2 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.6+0.5 | 4.2+0.6 | 0.001 | ||||||

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.3+0.3 | 1.1+0.1 | 0.001 | ||||||

| LDL (mmol/L) | 1.8+0.6 | 3+0.6 | 0.00001 | ||||||

| Triglycerides(mmol/L) | 1.3+0.5 | 1.3+0.5 | |||||||

| ALT (IU/L) | 22+7 | 38+30 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 81+12 | 107+24 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Urea (mmol/L) | 4.8+1.2 | 10+5 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Healthy(mean±SD) | CVD(mean±SD) | P-vaule | |||

| WBC (10e3/uL) | 7+1.6 | 10.6+5 | 0.001 | ||

| RBC (10e6/uL) | 5+0.35 | 4.7+0.9 | |||

| Hematocrit % | 43+3 | 43+8 | |||

| MCV (fL) | 83+4 | 90+3.7 | 0.0001 | ||

| MCH (pg) | 27+2 | 29+2 | 0.01 | ||

| MCHC (g/dL) | 33+1.2 | 32+1.3 | 0.01 | ||

| RDW-CV % | 13+1.5 | 12+2 | 0.05 | ||

| MPV (fL) | 10+0.6 | 8+1.2 | 0.001 | ||

| Platelets (10e3/uL) | 268+50 | 275+103 | |||

| Neutrophils % | 47+11 | 65+11 | 0.0001 | ||

| Lymphocytes % | 40+10 | 22+11 | 0.0001 | ||

| Monocytes % | 8+1.8 | 8.6+2.3 | |||

| Eosinophils % | 3+1.3 | 2.3+1.3 | 0.05 | ||

| Basophils % | 0.7+0.2 | 0.8+0.3 | 0.05 |

| Measure | Healthy (mean±SD) | CVD (mean±SD) | p-value |

| Lp-PLA2 (ng/ml) | 101+31 | 419+185 | 0.0001 |

| IL-6 (ng/ml) | 40+17 | 74+17 | 0.0001 |

| TNF-a (ng/ml) | 3.6+0.8 | 4.3+0.9 | 0.0001 |

| ox-LDL (nmol/ml) | 242+66 | 430+147 | 0.0001 |

| LP-a (ng/ml) | 90+33 | 134+31 | 0.0001 |

| FABP3 (ng/ml) | 3.1+0.1 | 3.4+1 | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).