Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

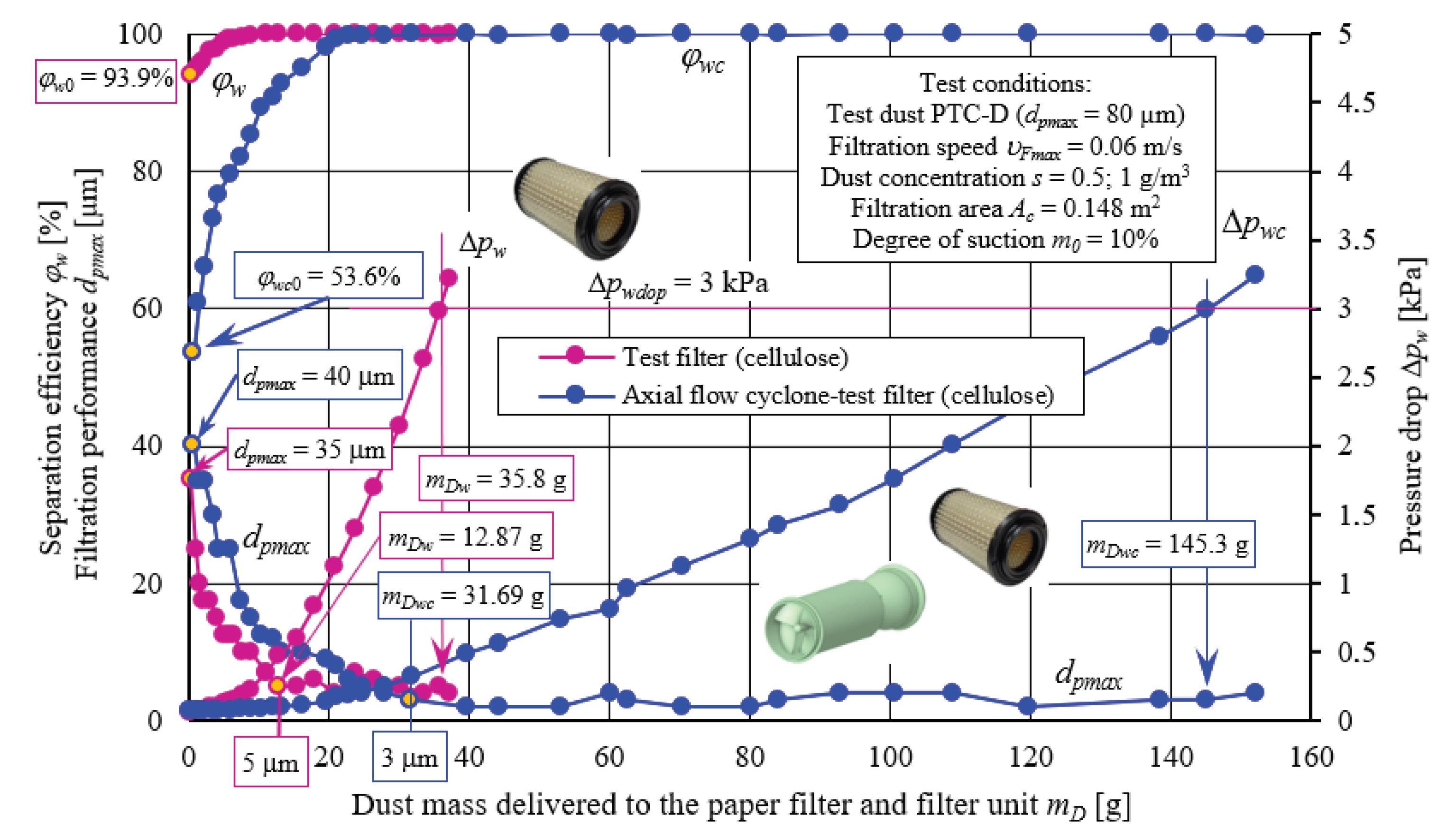

The operating conditions of engines in motor vehicles used in conditions of high air dustiness resulting from sandy ground and in helicopters using temporary landing sites were analyzed. The impact of mineral dust on accelerated abrasive and erosive wear of components and assemblies of piston and turbine engines was presented. Attention was drawn to the formation of dust deposits on turbine engine components. The possibilities of minimizing abrasive wear by using two-stage intake air filtration systems in motor vehicle engines were presented. The filtration properties of cyclones used as the first stage of air filtration were discussed. Three forms of protection for helicopter engines against the intake of contaminated air and to extend their service life were presented: intake barrier filters (IBF), tube separators (VTS), and particulate separators (IPS) called Engine Air Particle Separation (EAPS). It has been shown that pleating the filter bed significantly increases the filtration area without increasing the frontal area, whereby optimization of the filter bed geometry is of great importance here. An important advantage of the VTS air filtration system was demonstrated in the form of no maintenance due to the use of a system for the continuous removal of separated dust, whereby increasing the suction flow increases separation efficiency and pressure drop and energy losses. IPS is an air filtration system integrated with a turbine engine, characterized by a compact design, low external resistance, and no periodic maintenance, but with lower separation efficiency than VTS and IBF systems. The primary goal of such systems is to separate as many solid particles as possible at the lowest possible energy cost. The results of experimental research conducted by the author are presented, the aim of which was to demonstrate the advantages of a filtration unit consisting of cyclones and a porous partition in terms of increased filtration efficiency and filter operating time. During the research, an innovative method was used to determine the characteristics of a barrier filter operating in a two-stage filtration system, which reduces testing time and energy losses. It was a single VTS axial flow cyclone with a test barrier filter arranged in series behind it, whose filter bed was pleated paper with a suitably selected surface area. The results confirmed the advisability of using two-stage filtration systems to purify the intake air for internal combustion engines of motor vehicles and helicopter turbine engines. Since a porous partition increases pressure drop during operation, it is advisable to use permissible resistance sensors to limit their use due to increasing engine energy losses.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Impact of Mineral Dust on the Operation of Internal Combustion Engines

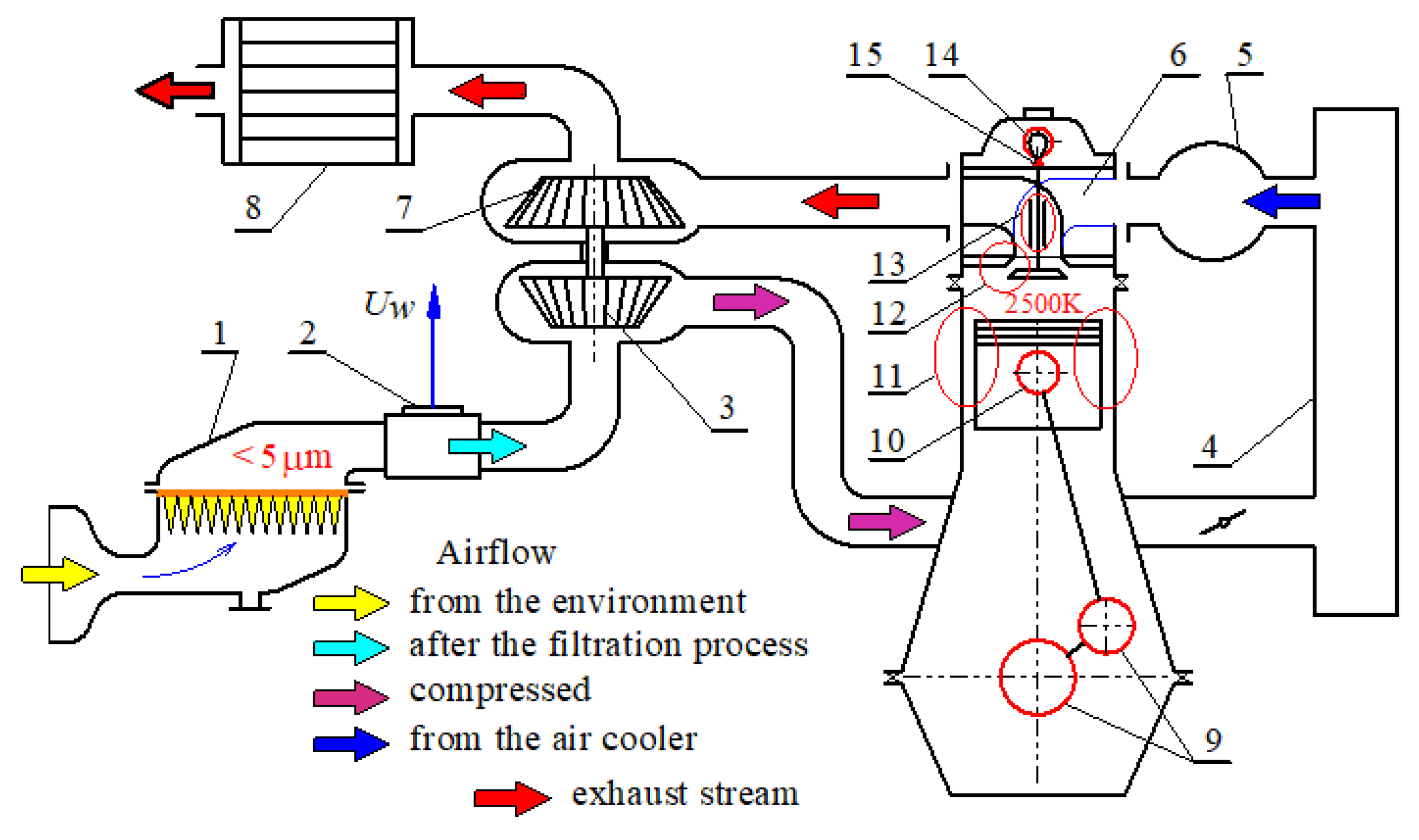

2.1. The Impact of Mineral Dust on the Wear of Components and the Operation of Piston Engines

- the formation of a layer of dust and other contaminants on the measuring element of the flow meter, which, due to its insulation properties, limits heat exchange with the flowing air stream and generates an incorrect signal,

- erosive wear of the compressor and turbine blades of the supercharger,

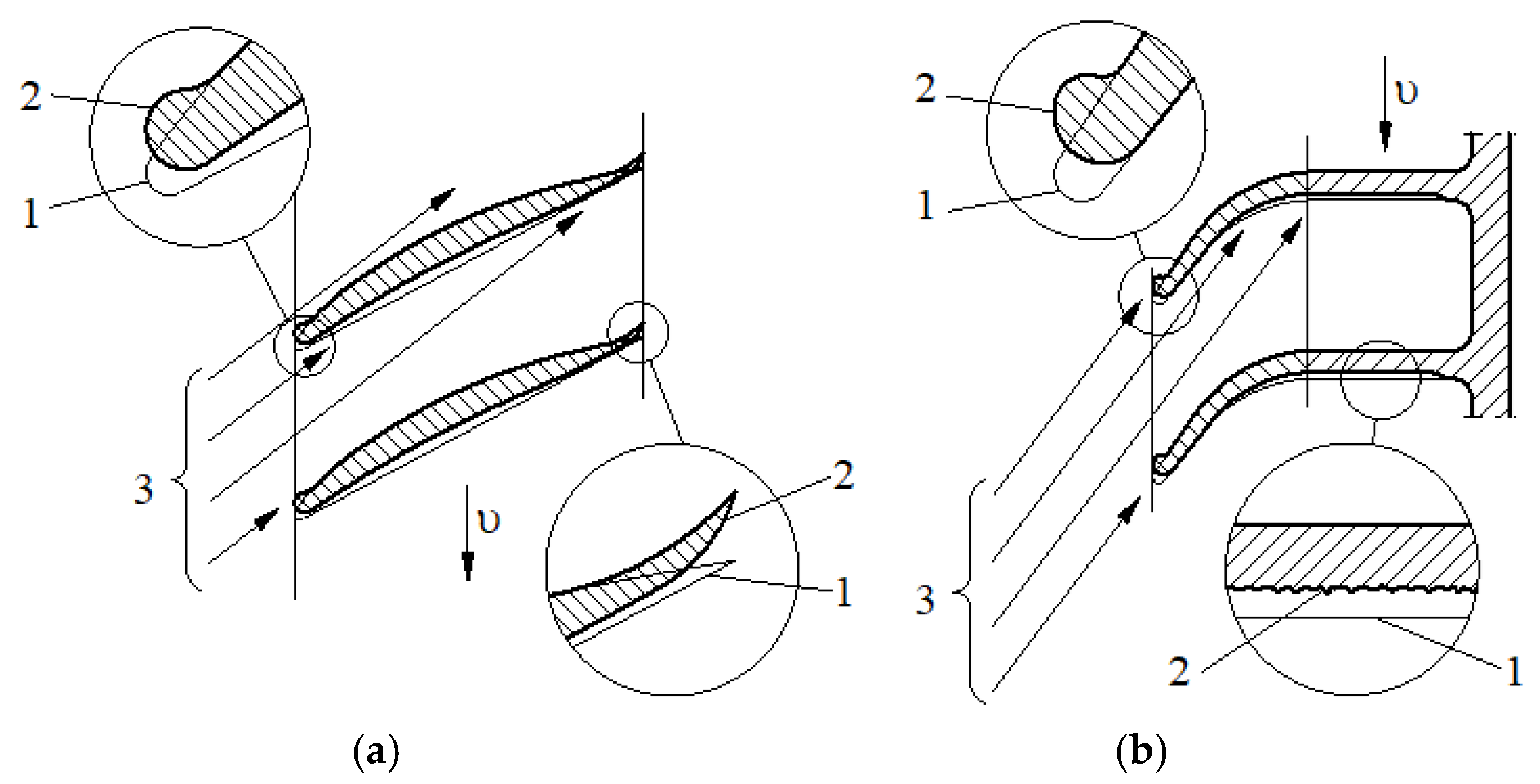

- abrasive wear of the P-PR-C components performing reciprocating motion,

- abrasive wear of the “valve stem-guide” components performing reciprocating motion,

- erosive wear of the seats and poppets of the intake and exhaust valves,

- abrasive wear of the sliding bearing components (journal-bearing shell) of the crankshaft, camshaft, and turbocharger shaft,

- abrasive wear of other friction-operated assemblies supplied with lubricating oil (cam-valve disc, valve levers,

- formation of a layer of molten dust particles on the catalytic surface of reactors, resulting in reduced efficiency.

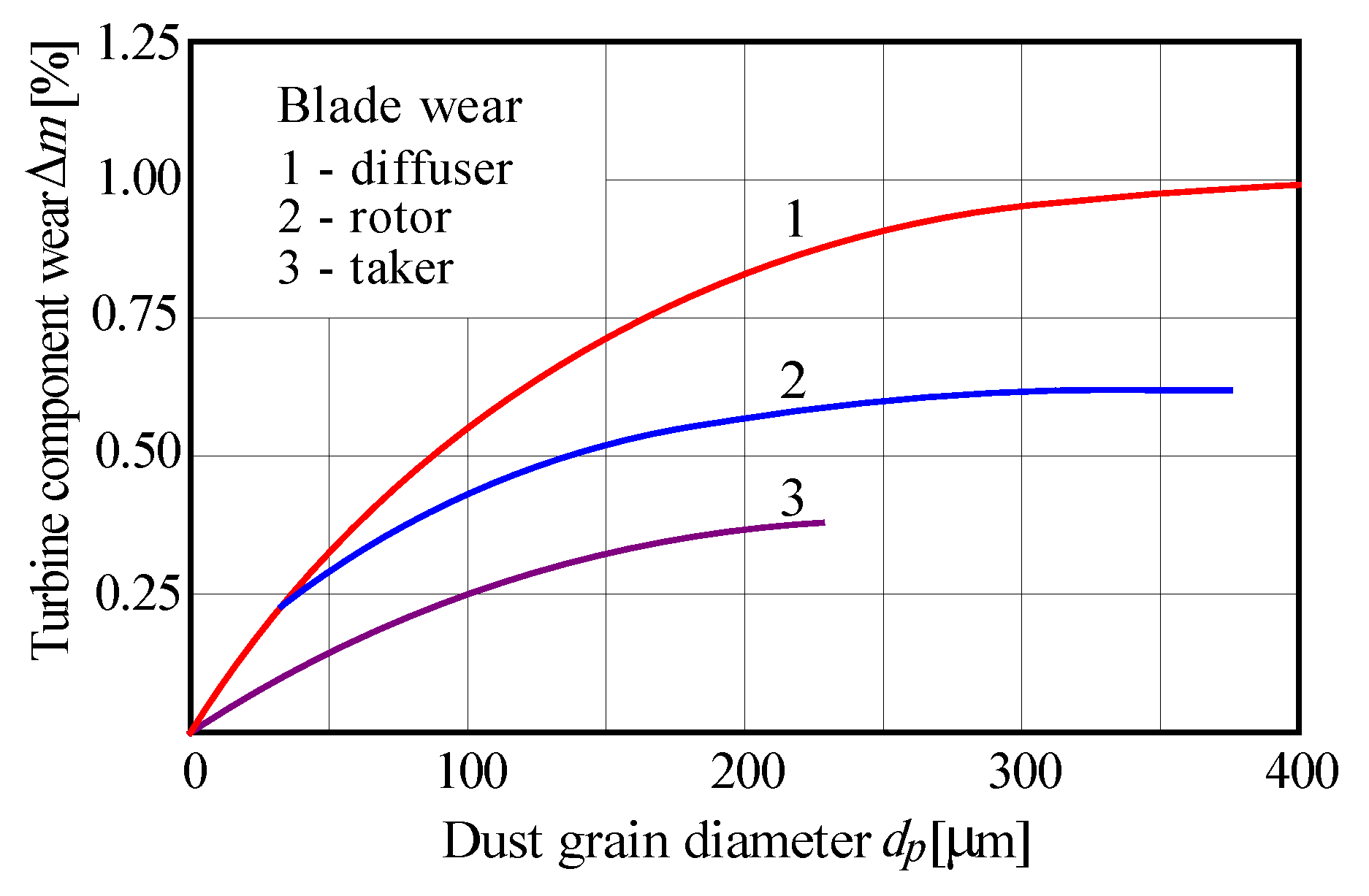

2.2. The Impact of Mineral Dust on Component Wear and Turbine Engine Operation

3. Filtration of Air Intake for Motor Vehicle Engines

4. Filtration of Air Intake for Helicopter Turbine Engines

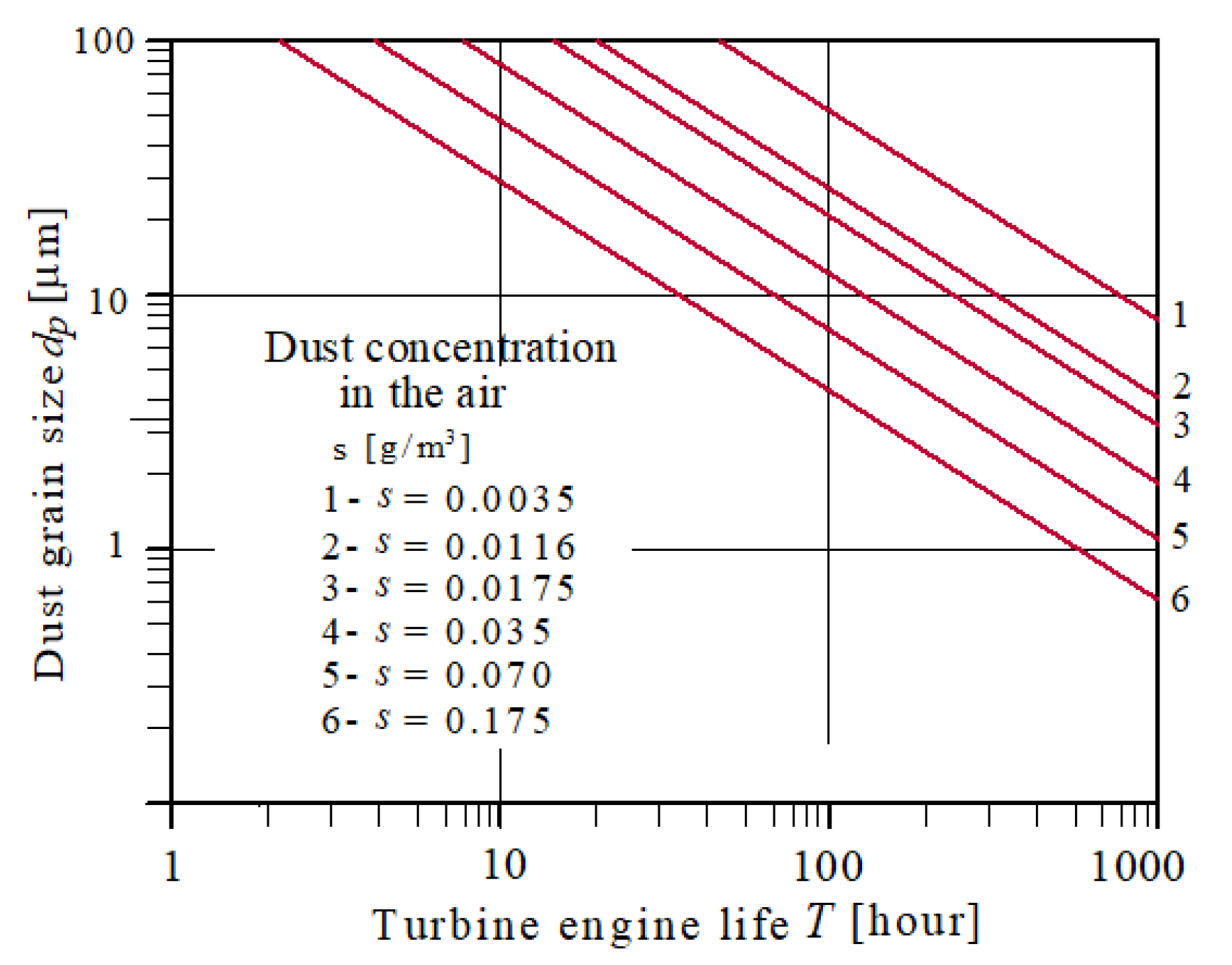

- Special vehicles (wheeled and tracked) are operated in sandy and off-road areas, where airborne dust concentrations are particularly high, often exceeding 1 g/m³. Helicopters, during takeoff (landing) on a random landing site in sandy terrain, create a dust cloud with dust concentrations reaching up to 3.5 g/m³, significantly reducing visibility and impeding control, potentially leading to disaster.

- Turbine engines, for proper operation, draw in large airflows (Boeing CH-47 - 39,600 m³/h), and therefore dust – 1.65 kg of dust per minute at an airborne dust concentration of 2.5 g/m³. The intake airflow for a 700 kW tracked vehicle engine is 3500 m3/h, while the dust mass drawn in with the air is several times smaller, at approximately 0.057 kg per minute.

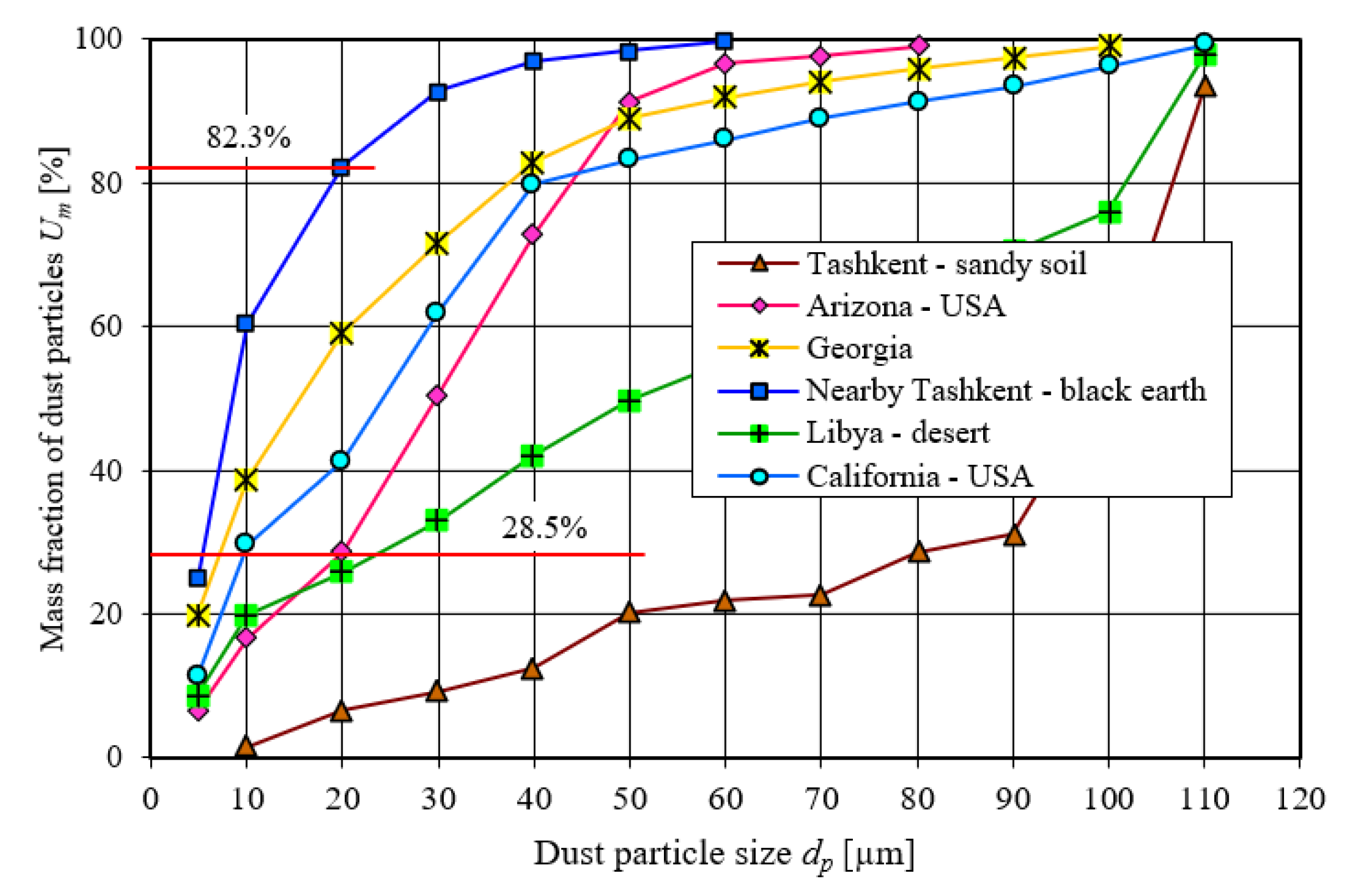

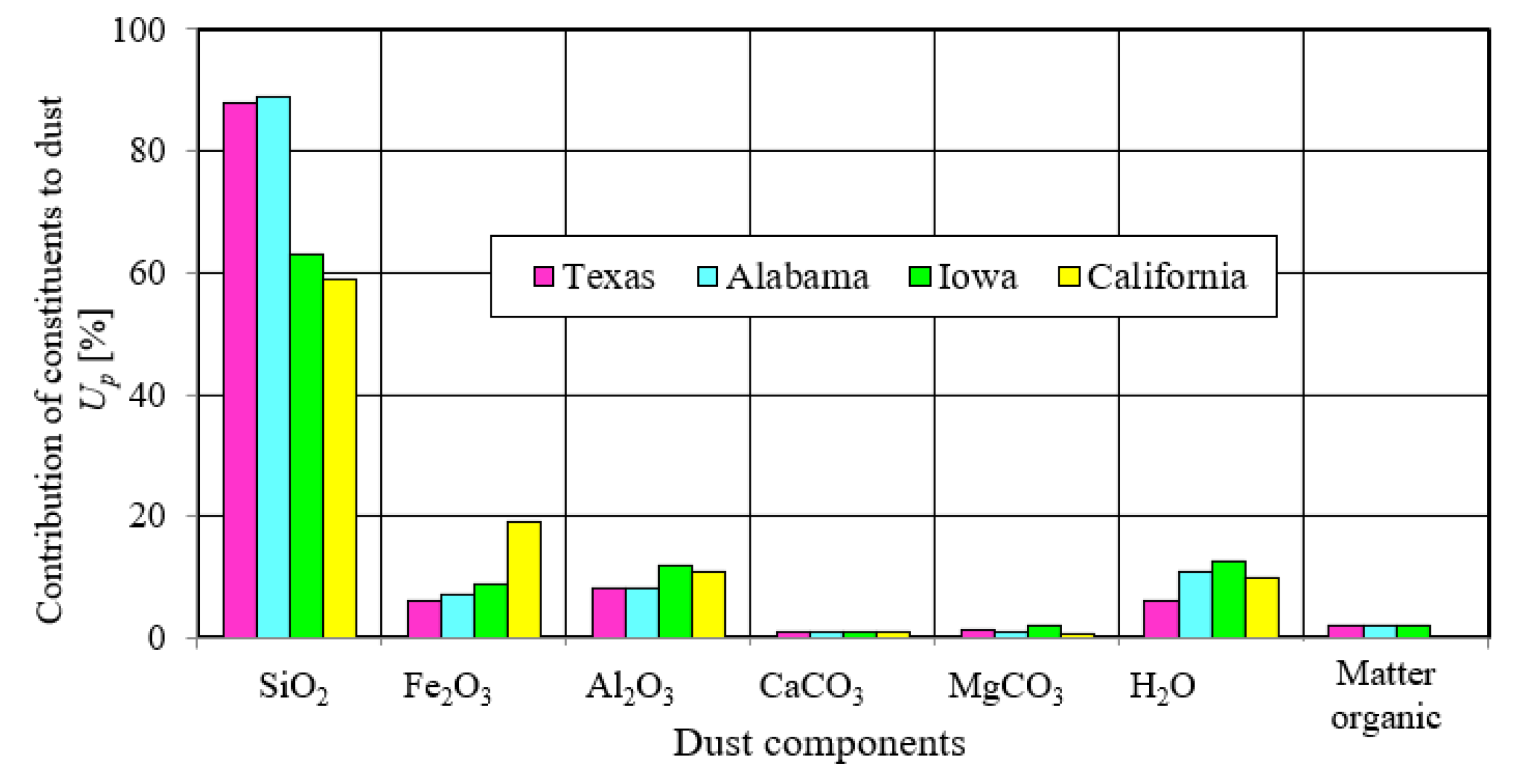

- Mineral dust grains are characterized by high hardness (7-9 on the Mohs scale) and irregular shapes, which have a destructive effect on engine components, causing accelerated wear. Silica SiO2 and corundum Al2O3 grains are particularly dangerous, with their mass fraction in the dust reaching 60-95%. This reduces the engine’s operating efficiency and limits its durability and reliability.

- In piston engines, excessive abrasive wear caused by mineral dust primarily affects the T-PR-C connection, which results in increased leakage in the piston head space, and consequently, a decrease in filling and engine power, as well as an increase in specific fuel consumption and exhaust opacity.

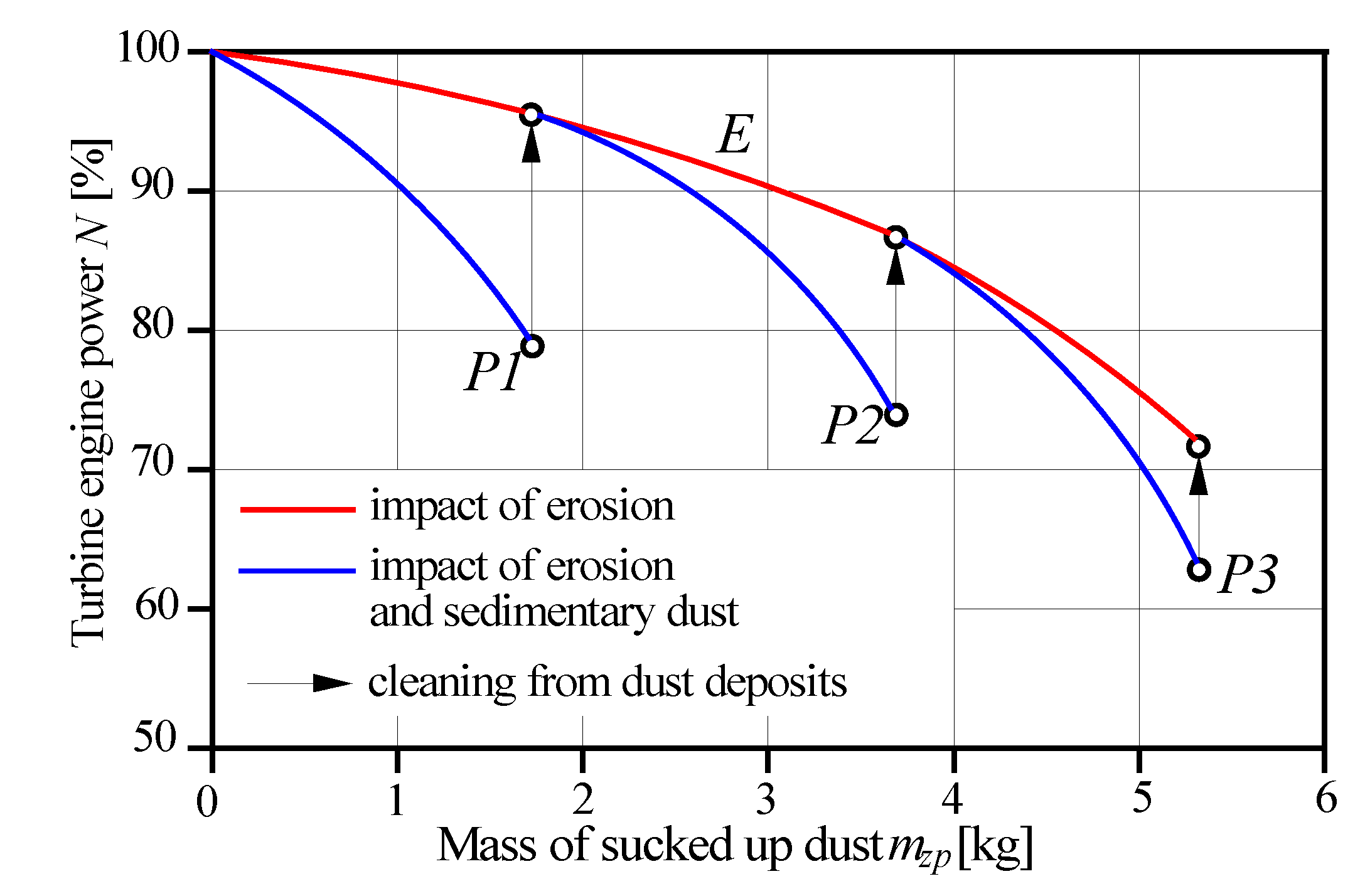

- In turbine engines, the primary effect of dust grains is accelerated erosive wear of individual parts and entire engine assemblies due to the high peripheral speeds of the rotor assemblies (200-500 m/s) and the deposition of dust deposits (molten contaminants) on the combustion chamber walls and turbine blades. Both effects simultaneously result in a deterioration of power, fuel consumption, and oil consumption characteristics.

- Erosive wear is a long-term phenomenon, while the accumulation of deposits on the first-stage engine blades and combustion chamber walls is a sudden phenomenon caused by high dust concentrations in the air intake despite the short duration of engine operation under such conditions. The cross-sectional area of the duct decreases, resulting in reduced airflow and engine stalling. This situation is common in helicopter engines during takeoff or landing on an unavoidable landing site, as well as in passenger aircraft that may come into contact with a volcanic ash cloud. There have been reports of tragic helicopter engine failures caused by ingesting excessive amounts of ash.

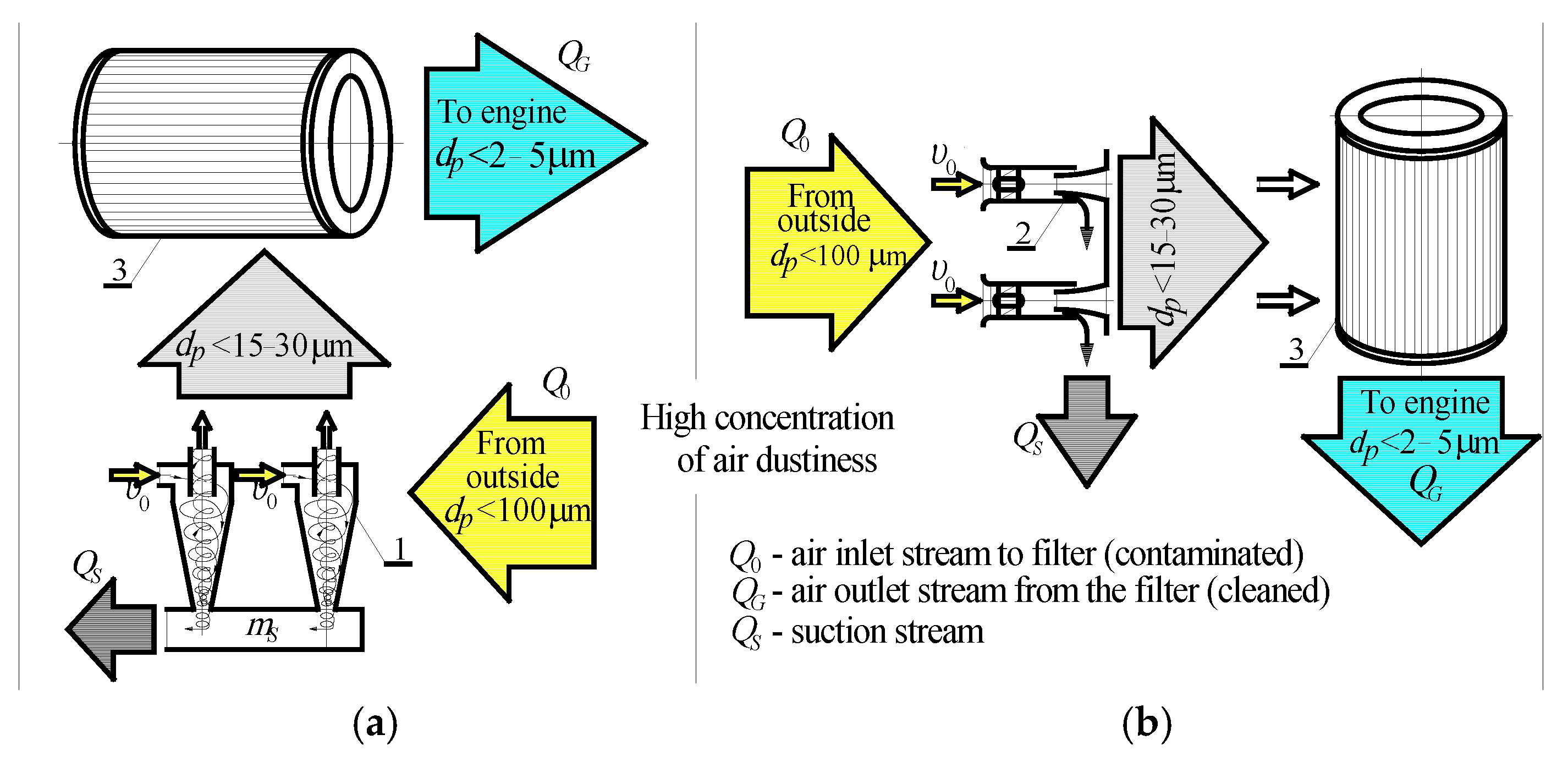

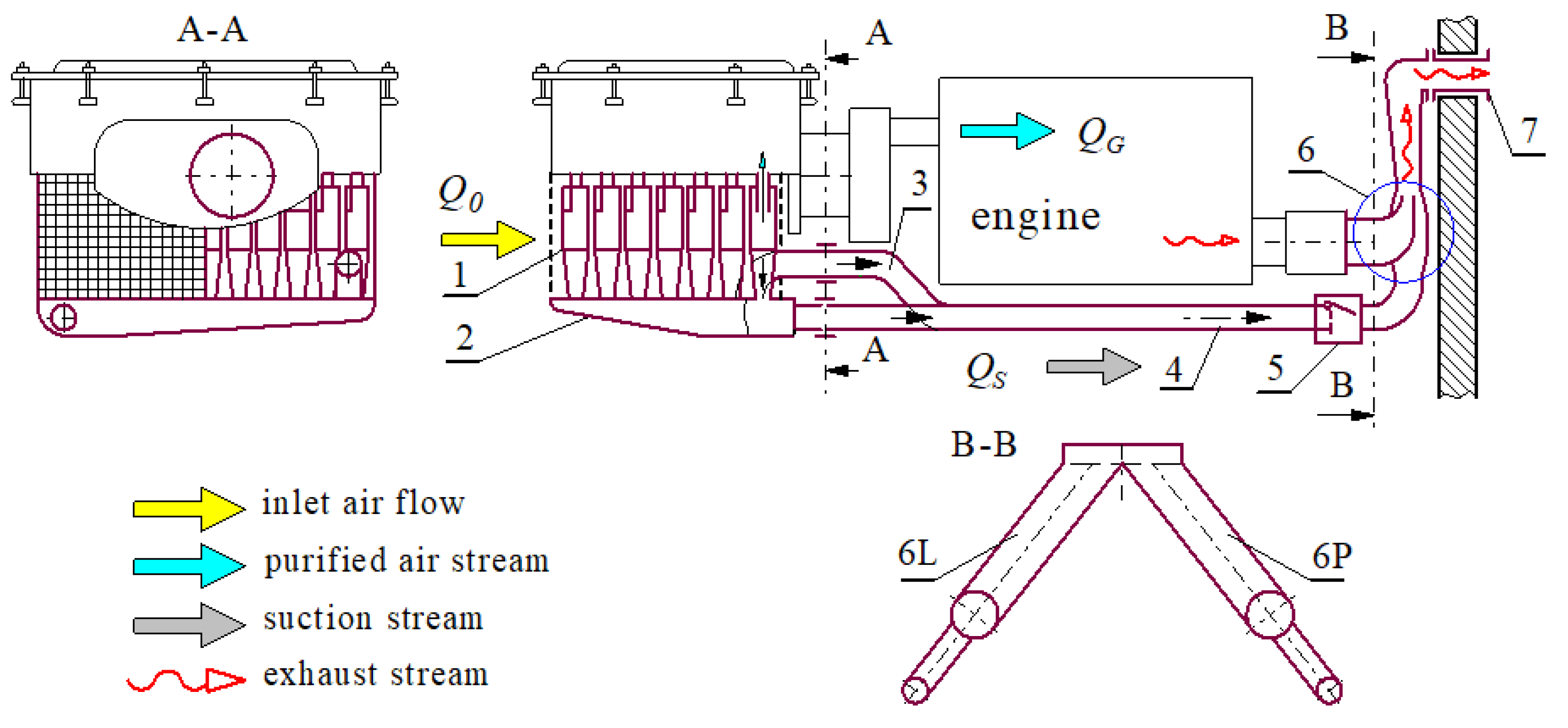

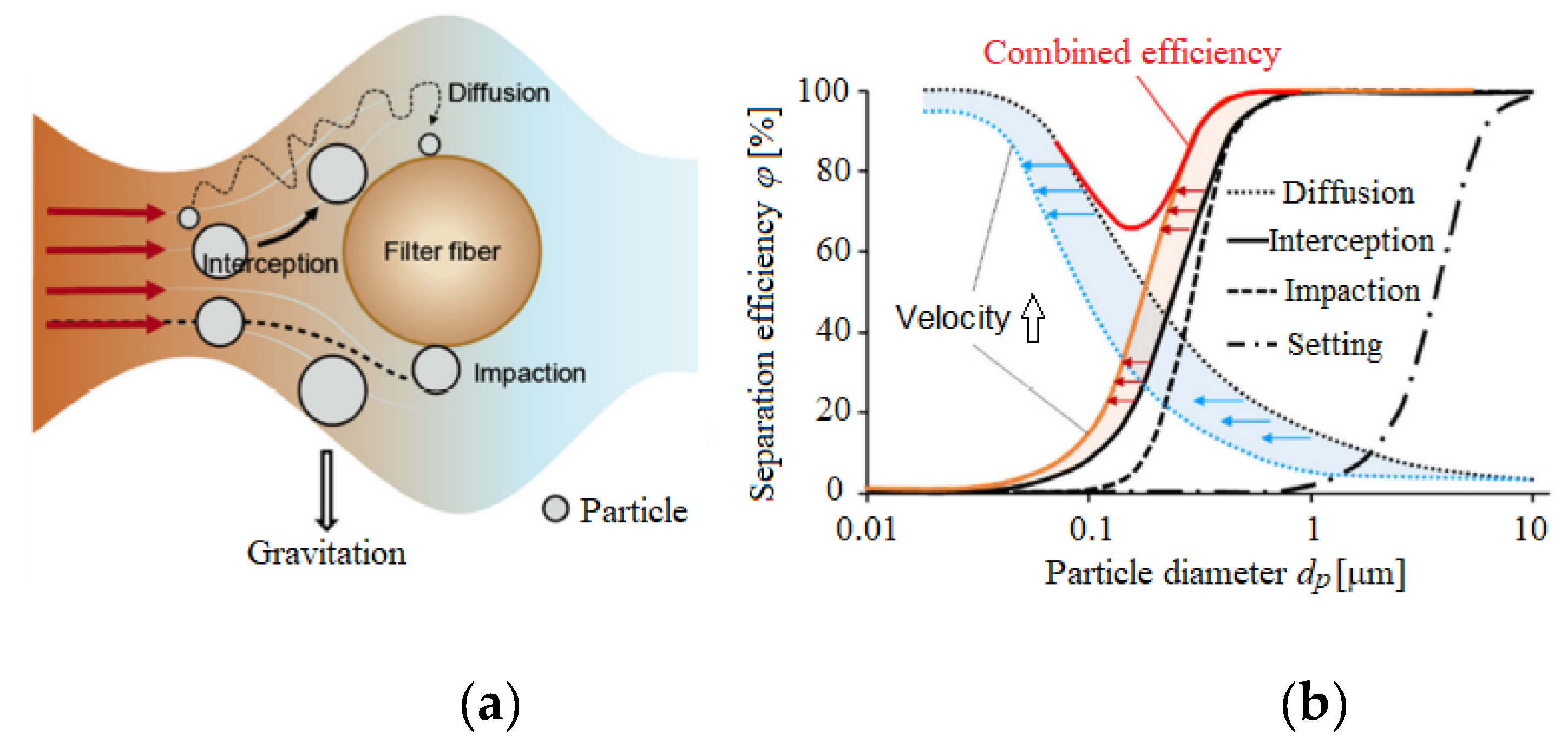

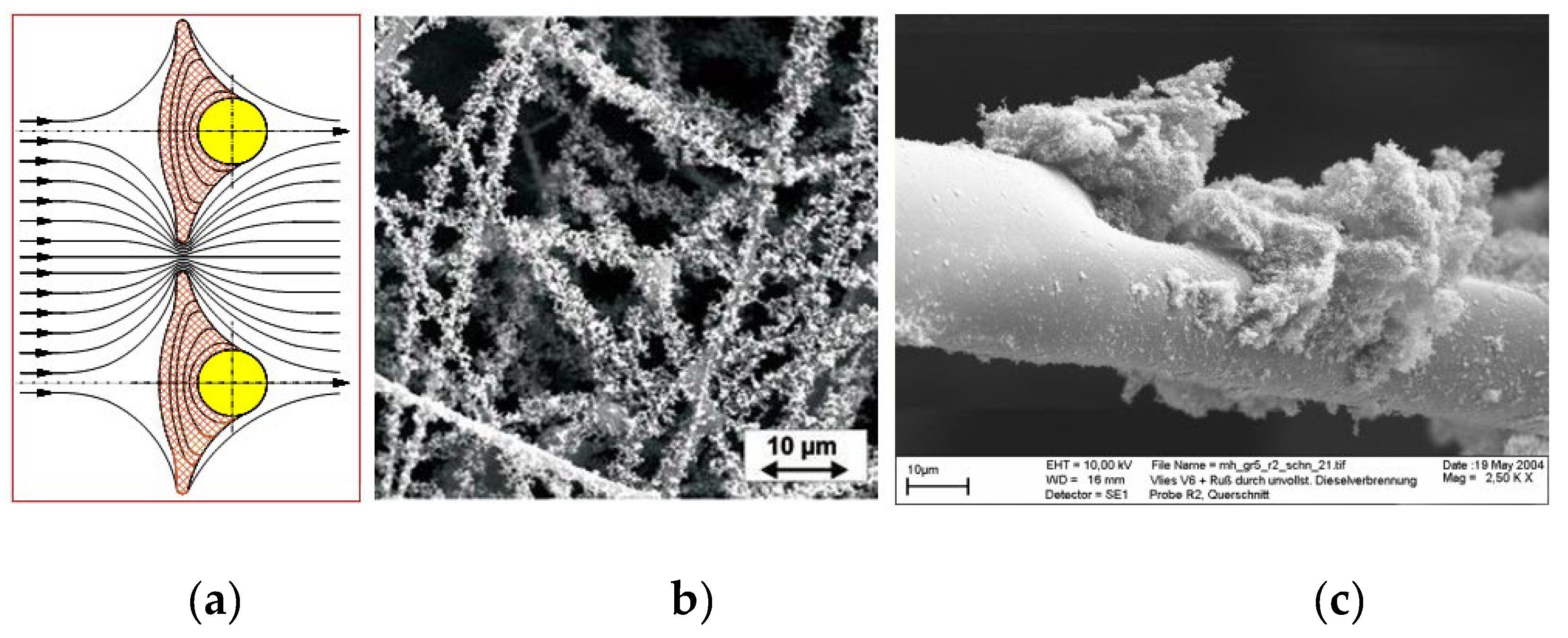

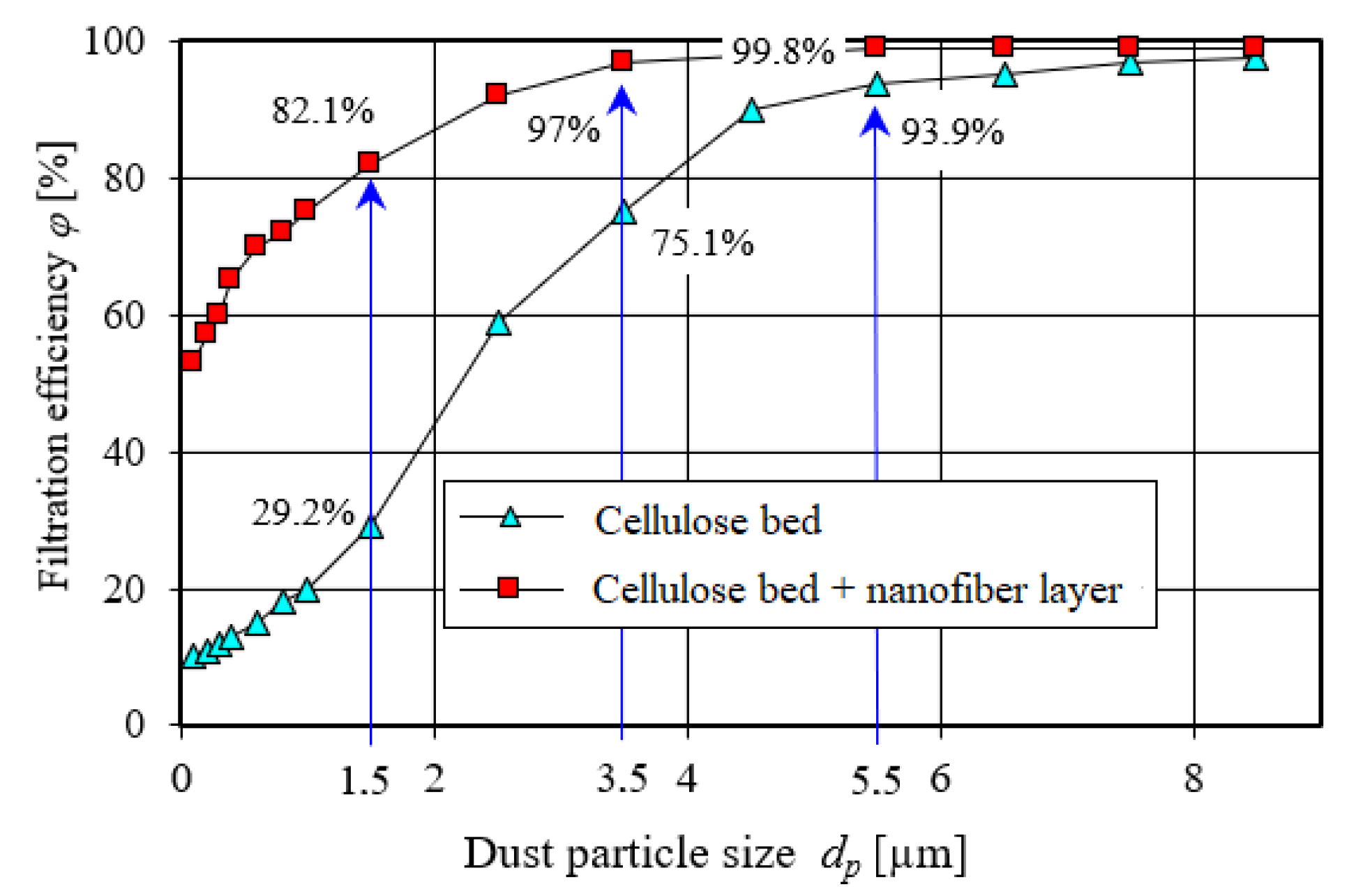

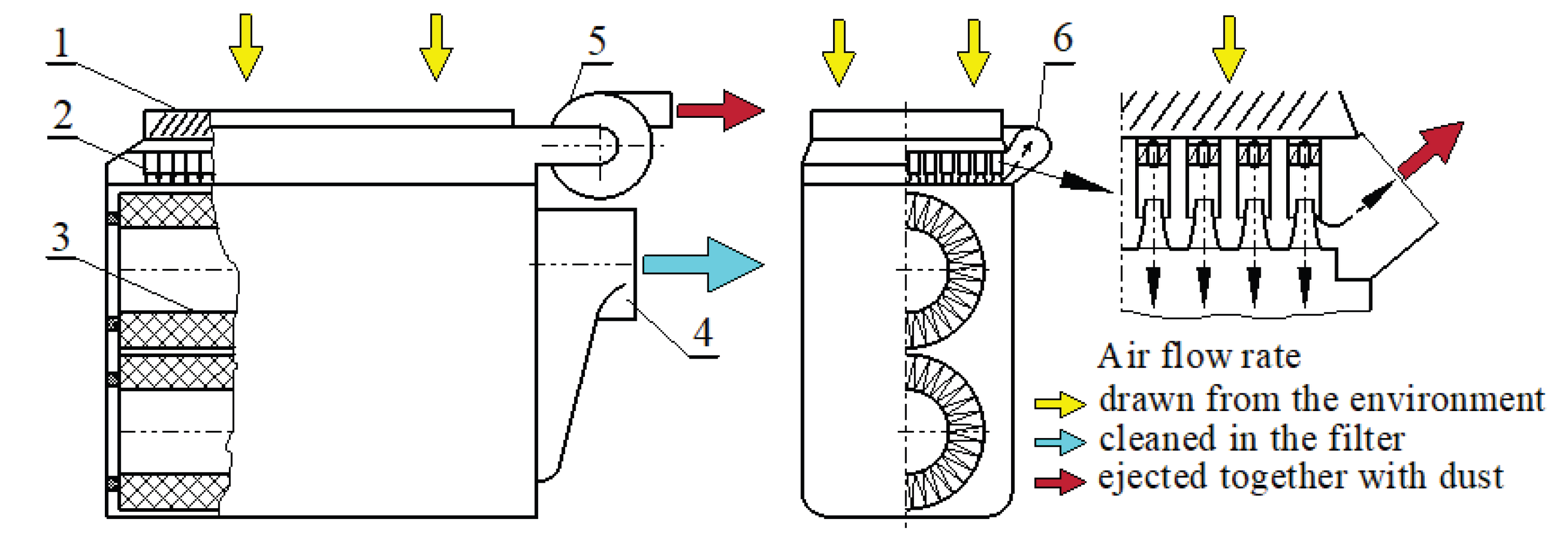

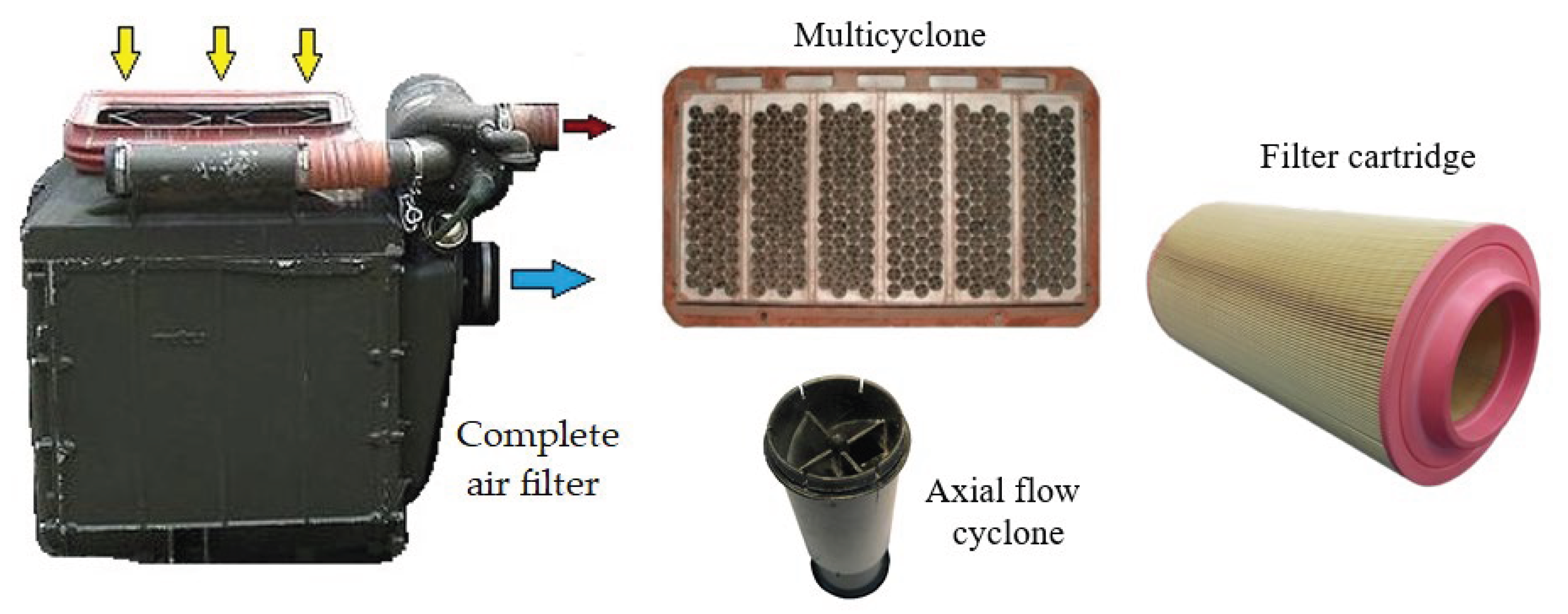

- Internal combustion engines of motor vehicles are protected from the harmful effects of mineral dust contained in the intake air by using two-stage filtration systems. The first filtration stage is a set of tangential or through-flow cyclones, and the second is a series-arranged porous barrier in the form of a pleated filter paper insert. The two-stage system ensures extended service life but is limited by achieving permissible pressure drop and high accuracy (above 2-5 µm) of the engine intake air.

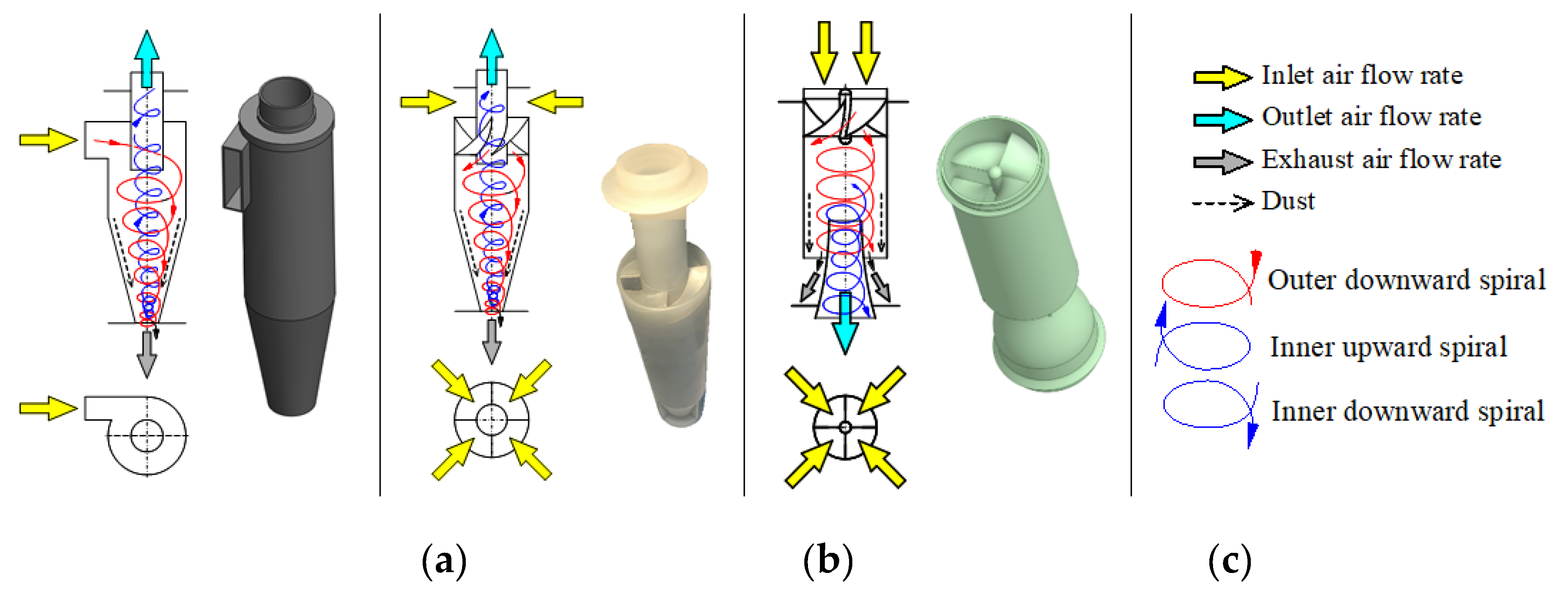

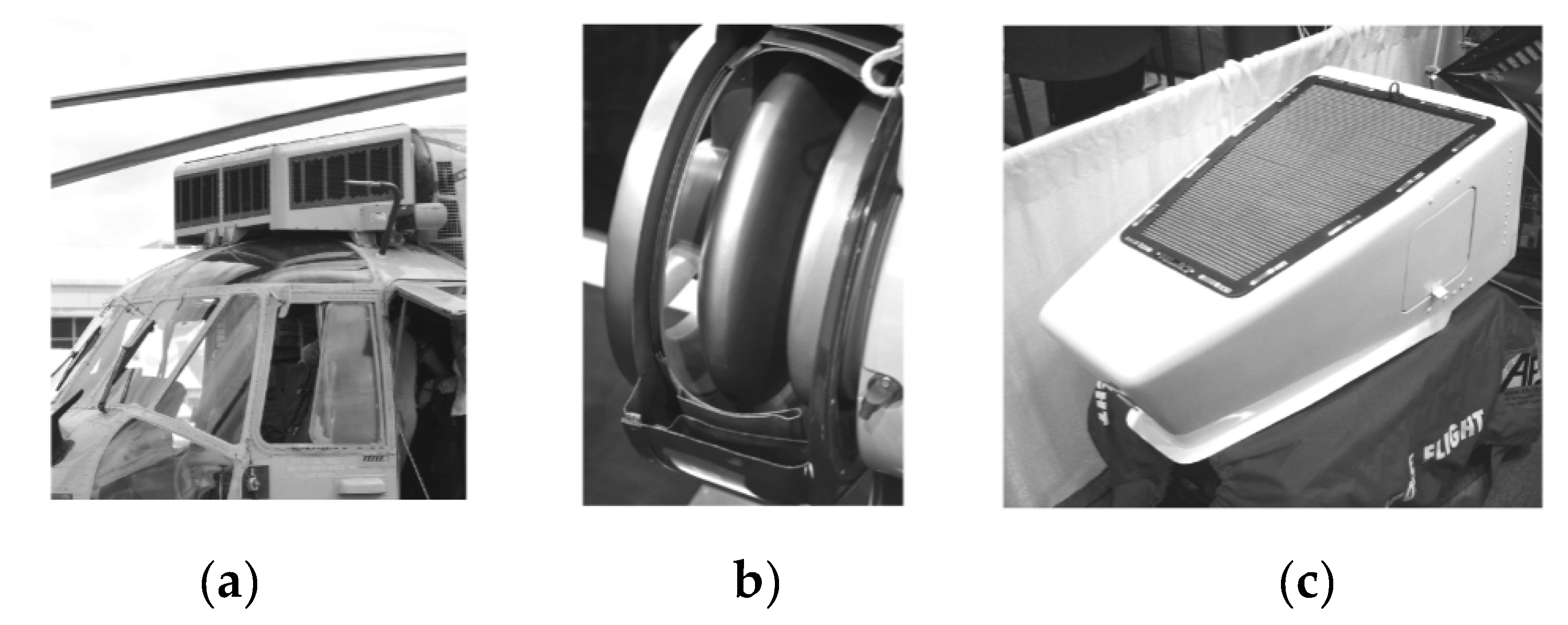

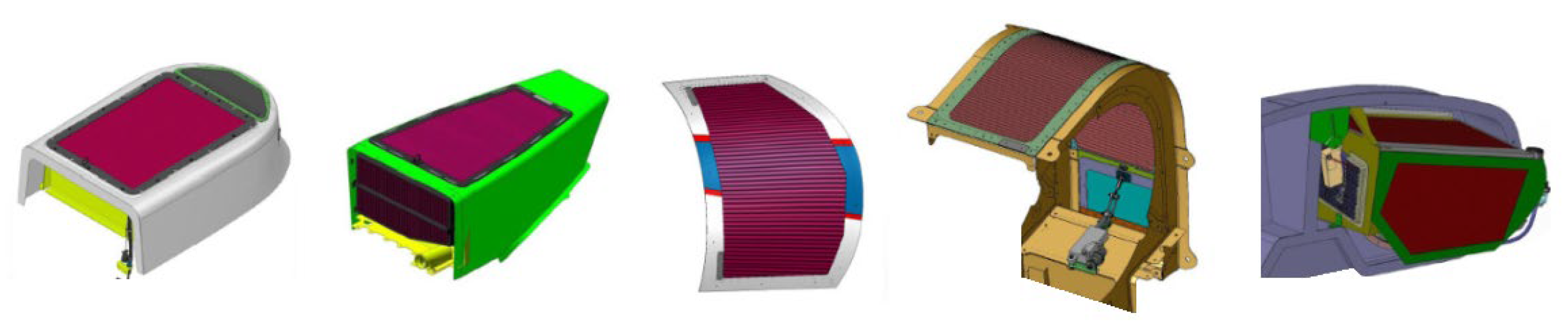

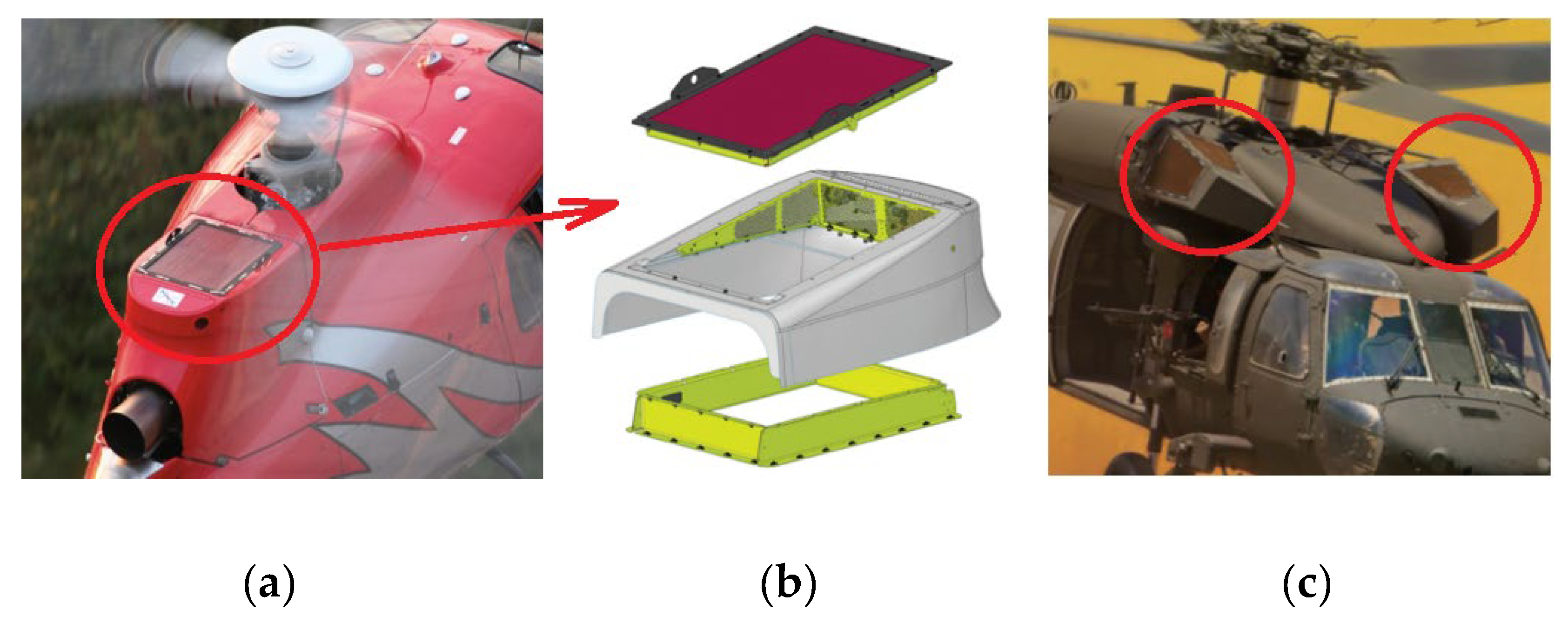

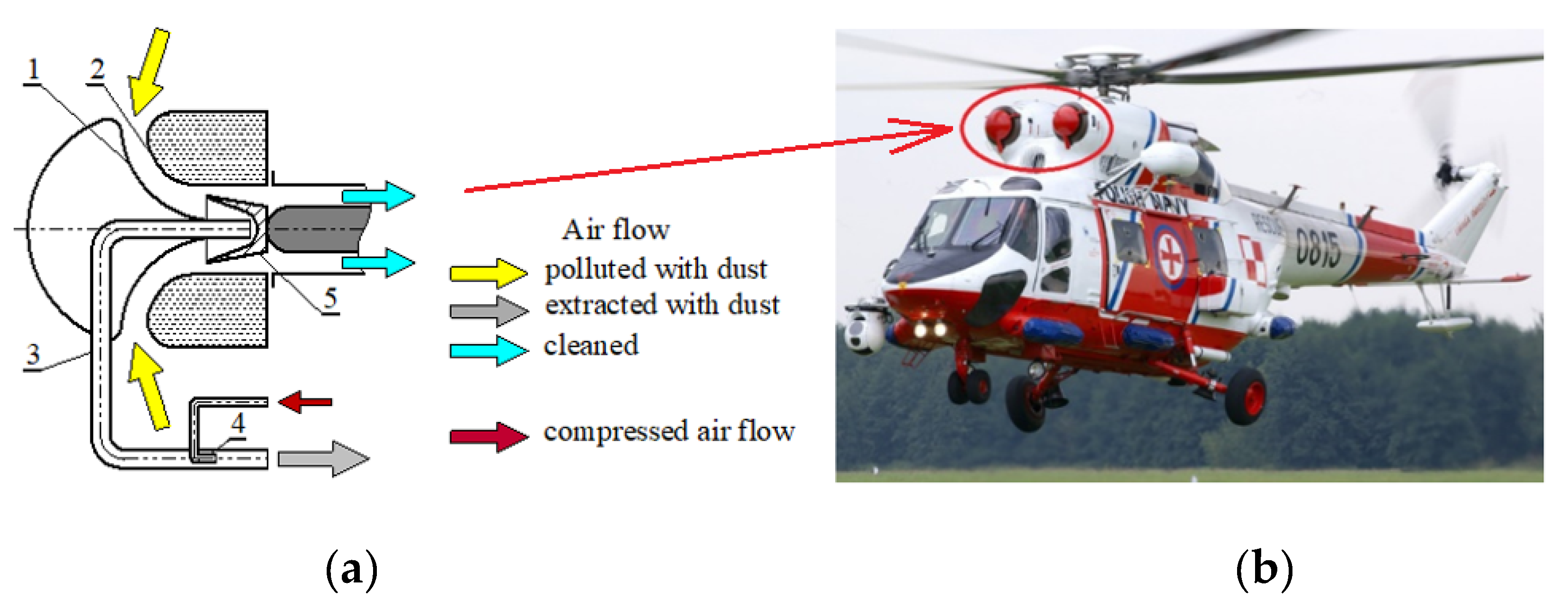

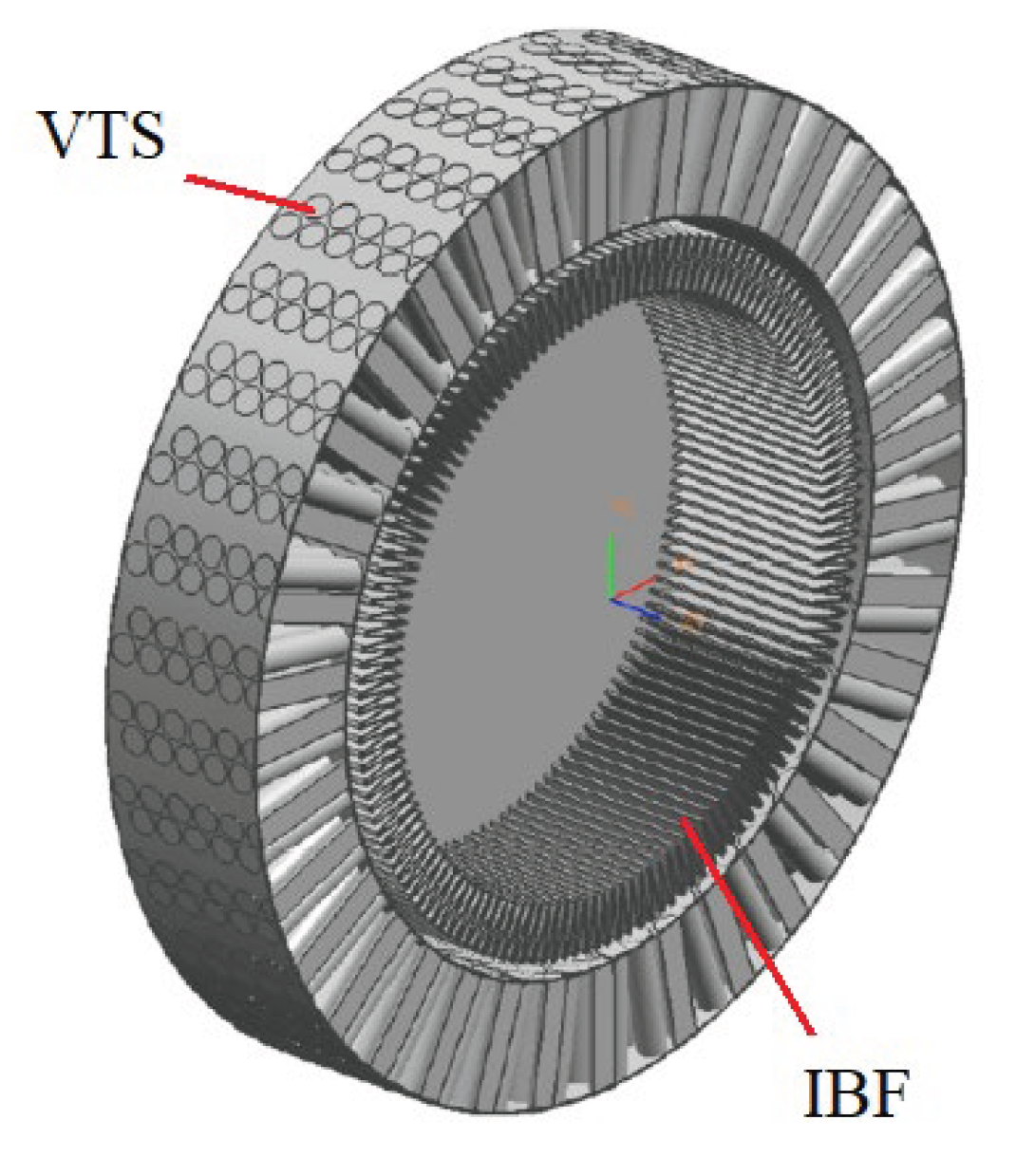

- To protect helicopter engines from ingesting contaminated air and extending their service life, pipe separators (VTS), inlet barrier filters (IBF), and particle separators (IPS) are used. These devices, collectively referred to as Engine Air Particle Separation (EAPS), can be used individually or in a two-stage system, significantly increasing filtration efficiency and accuracy.

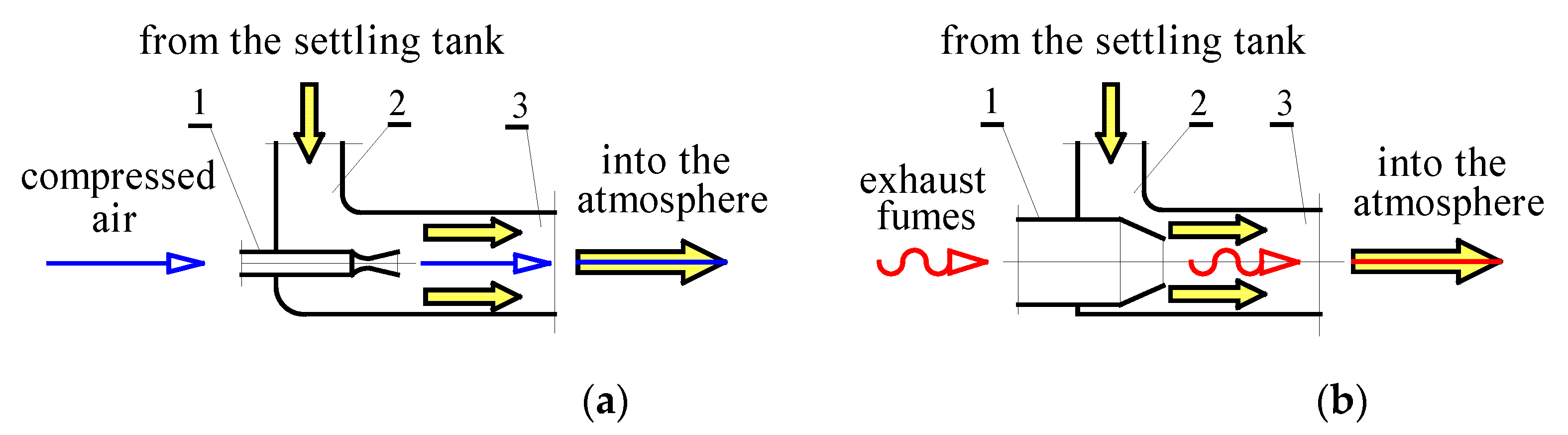

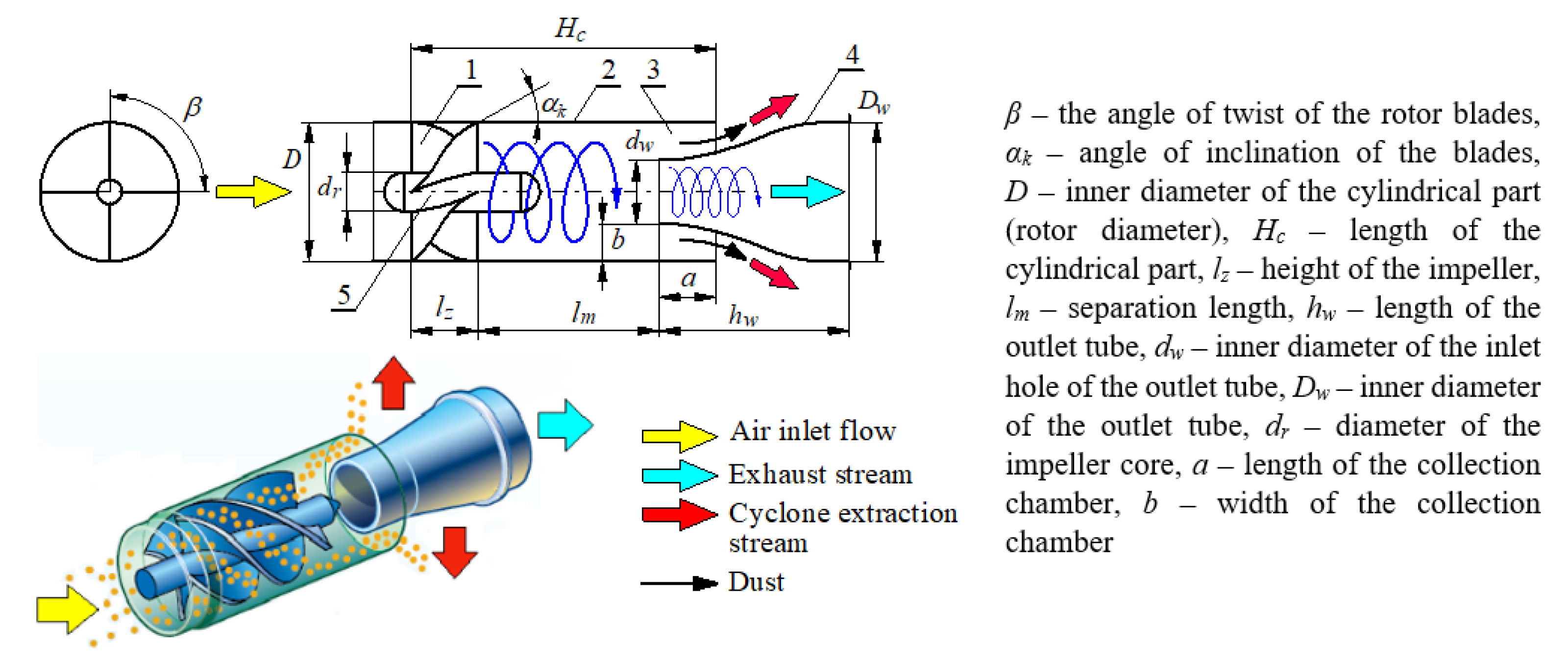

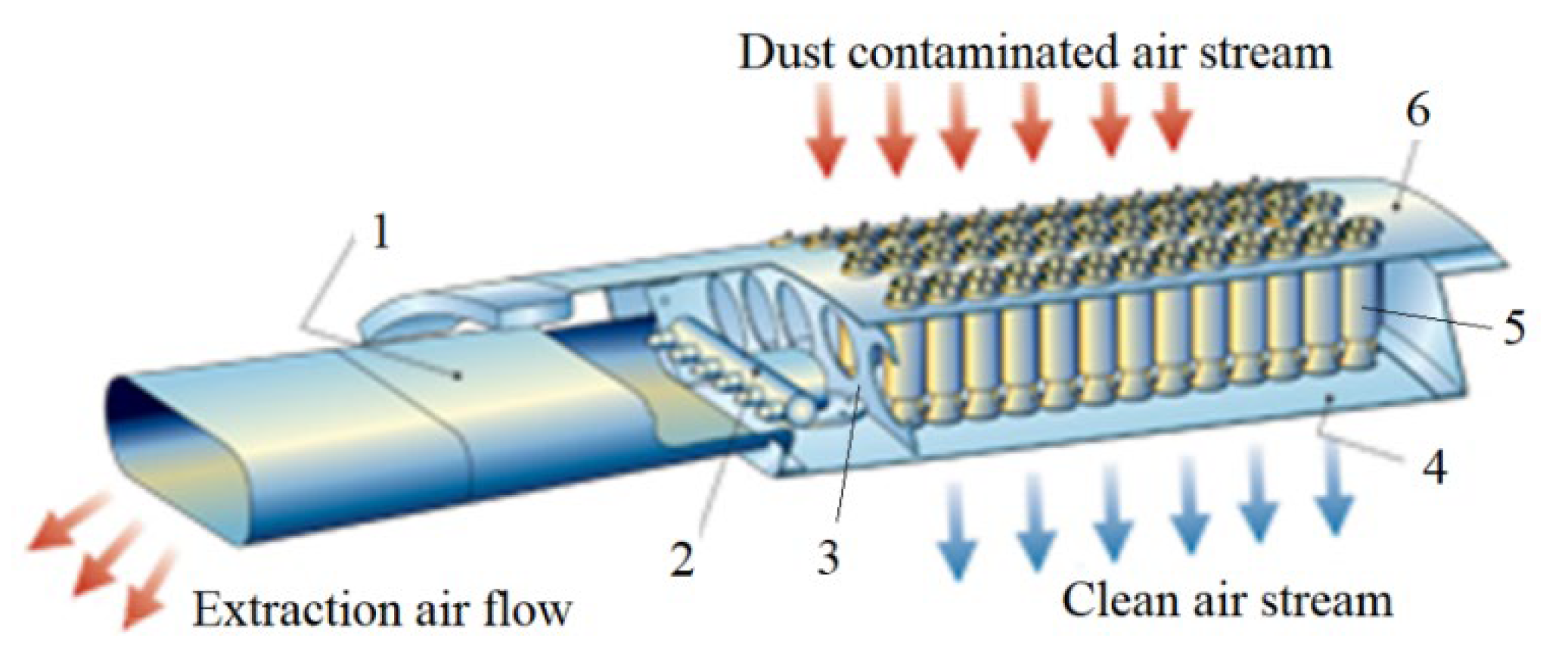

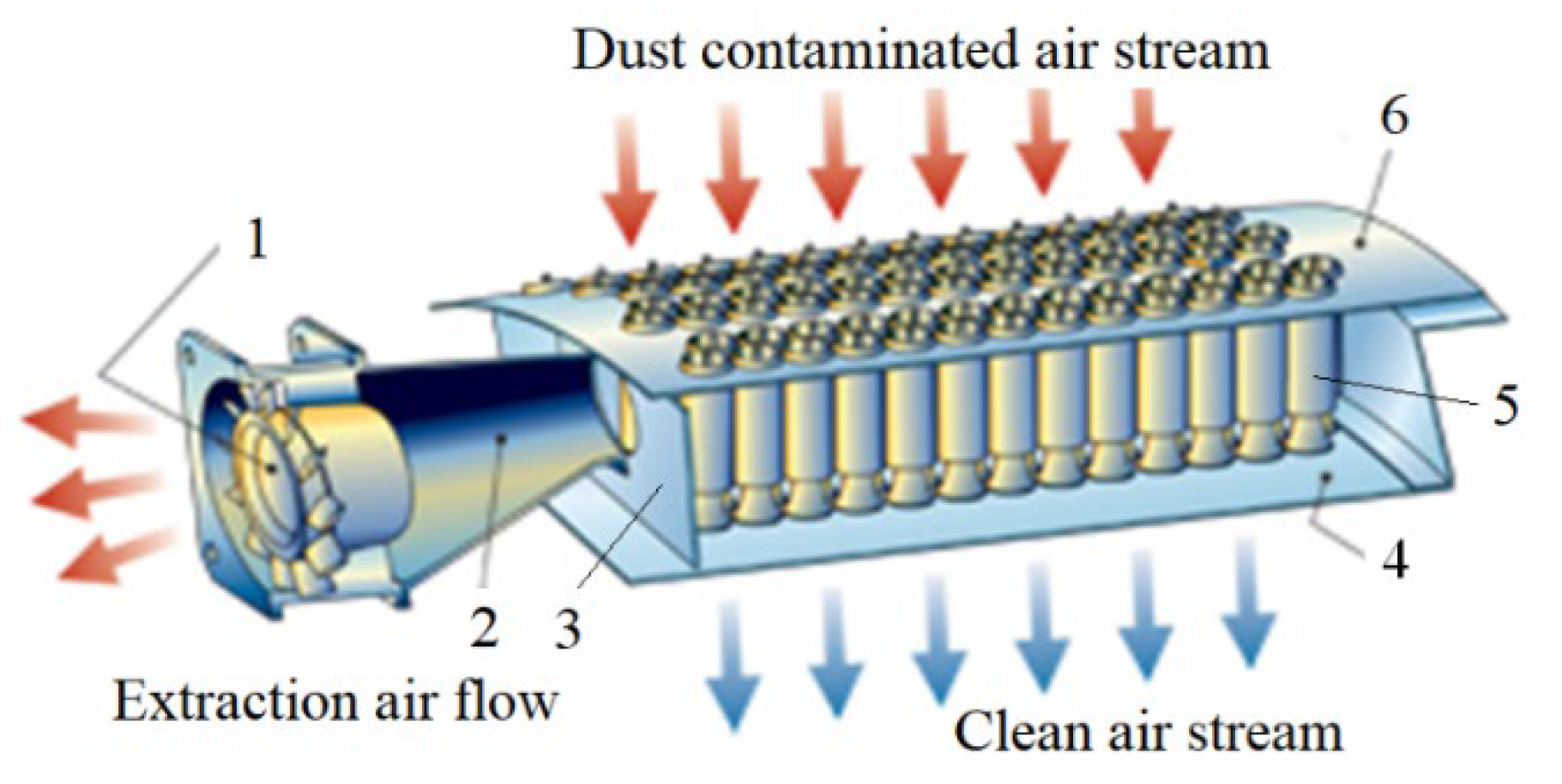

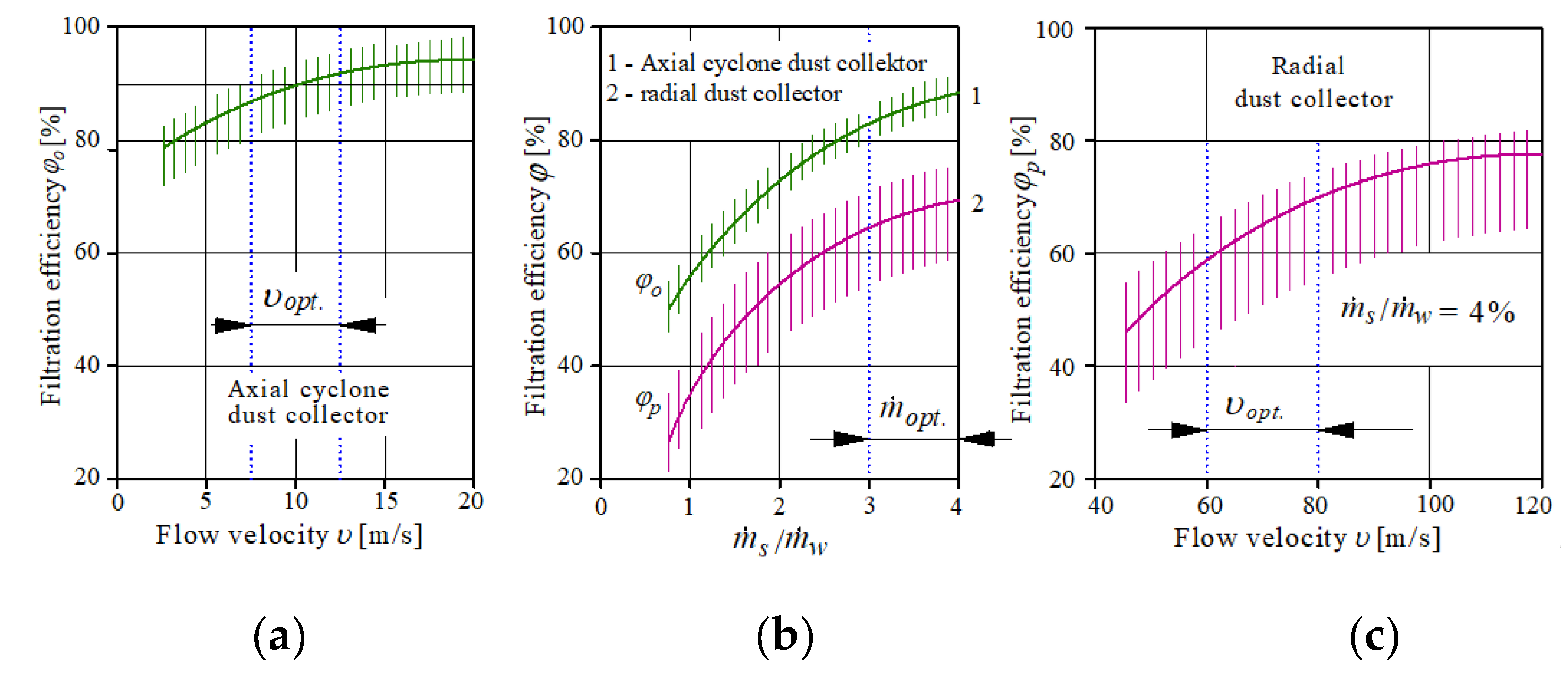

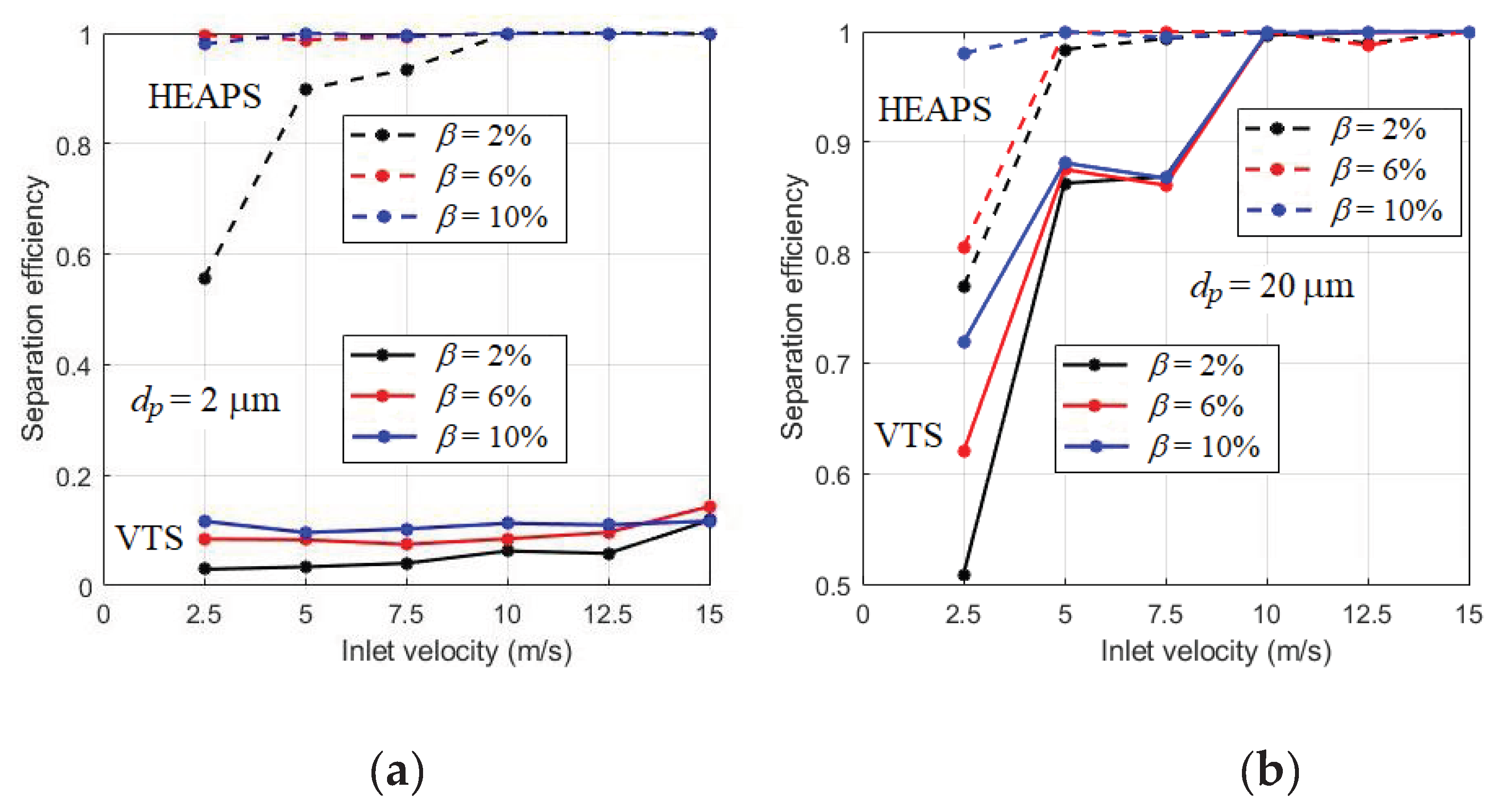

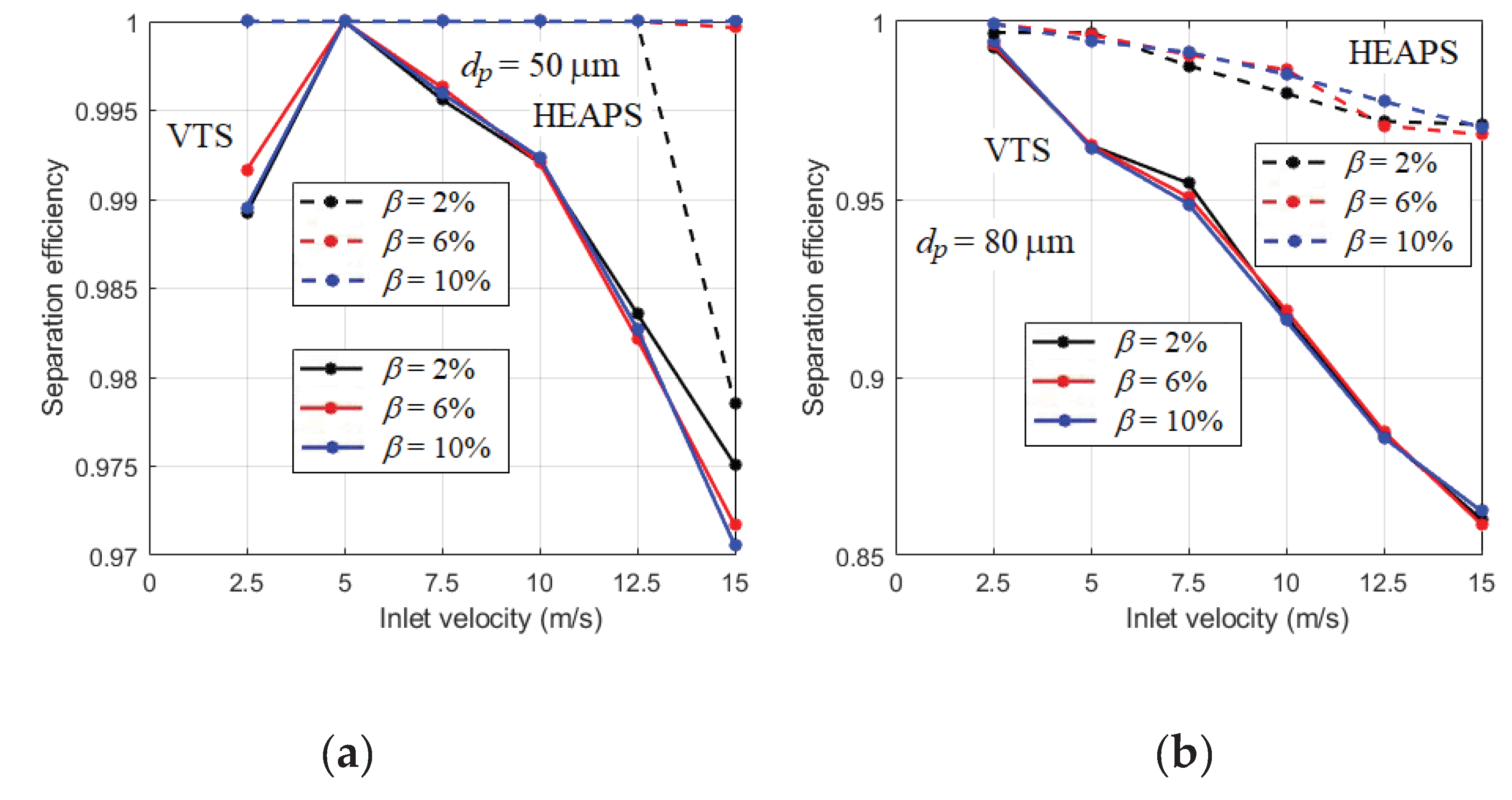

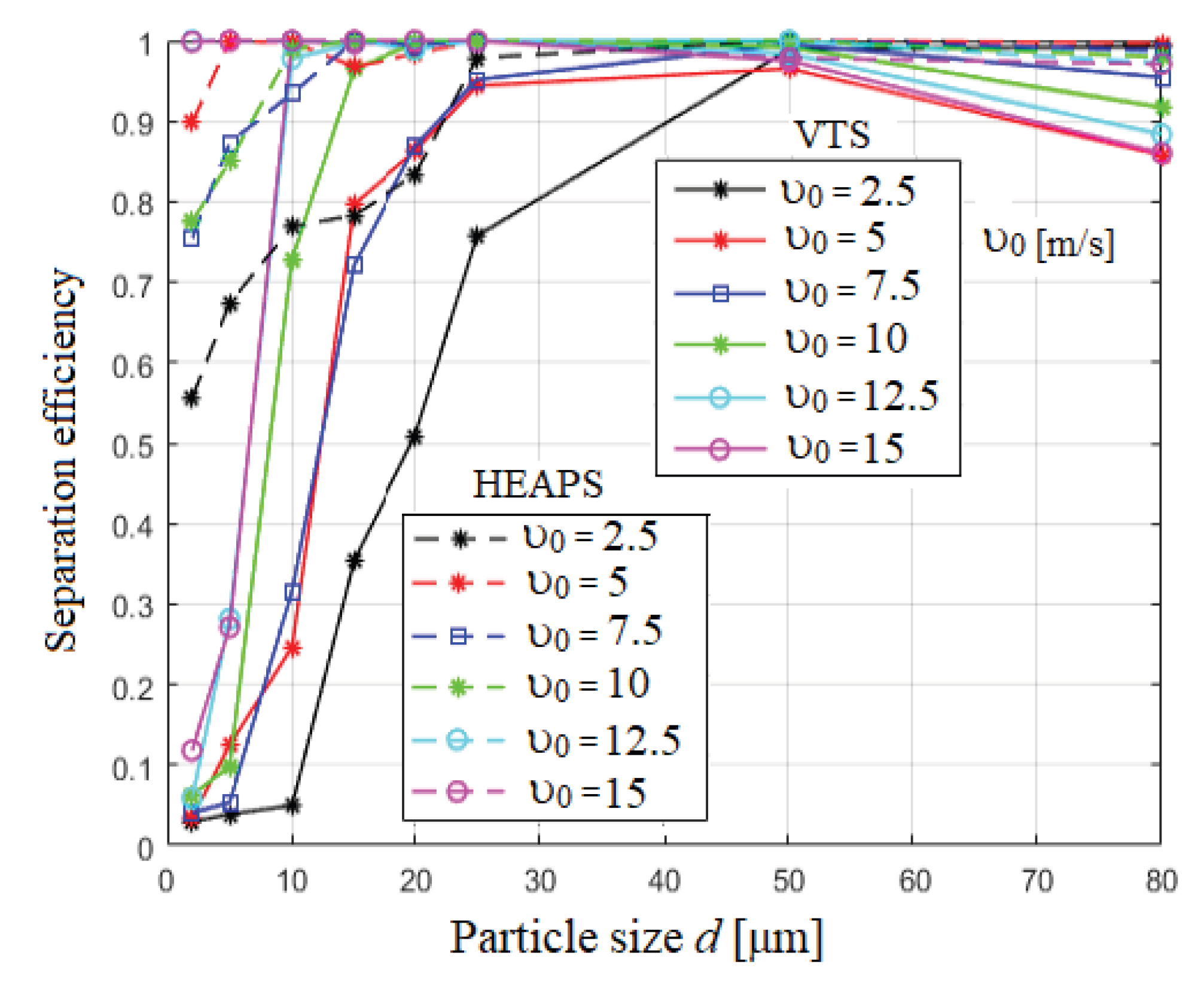

- Tubular separators (VTS) are constructed from several hundred individual cyclones with an axial inlet of uniform diameter, typically no more than 40 mm, arranged parallel to each other offer many advantages, including: low pressure drop, maintenance-free due to automatic (ejector) dust removal, and protection against ice, snow, heavy rain, and salt spray. The VTS device generates additional pressure drop during flight because it is an externally installed device and requires a large surface area to accommodate the appropriate number of cyclones and ensure the required minimum inlet velocity. The VTS device itself provides low pressure drop and filtration efficiency ranging from 86 to 91%.

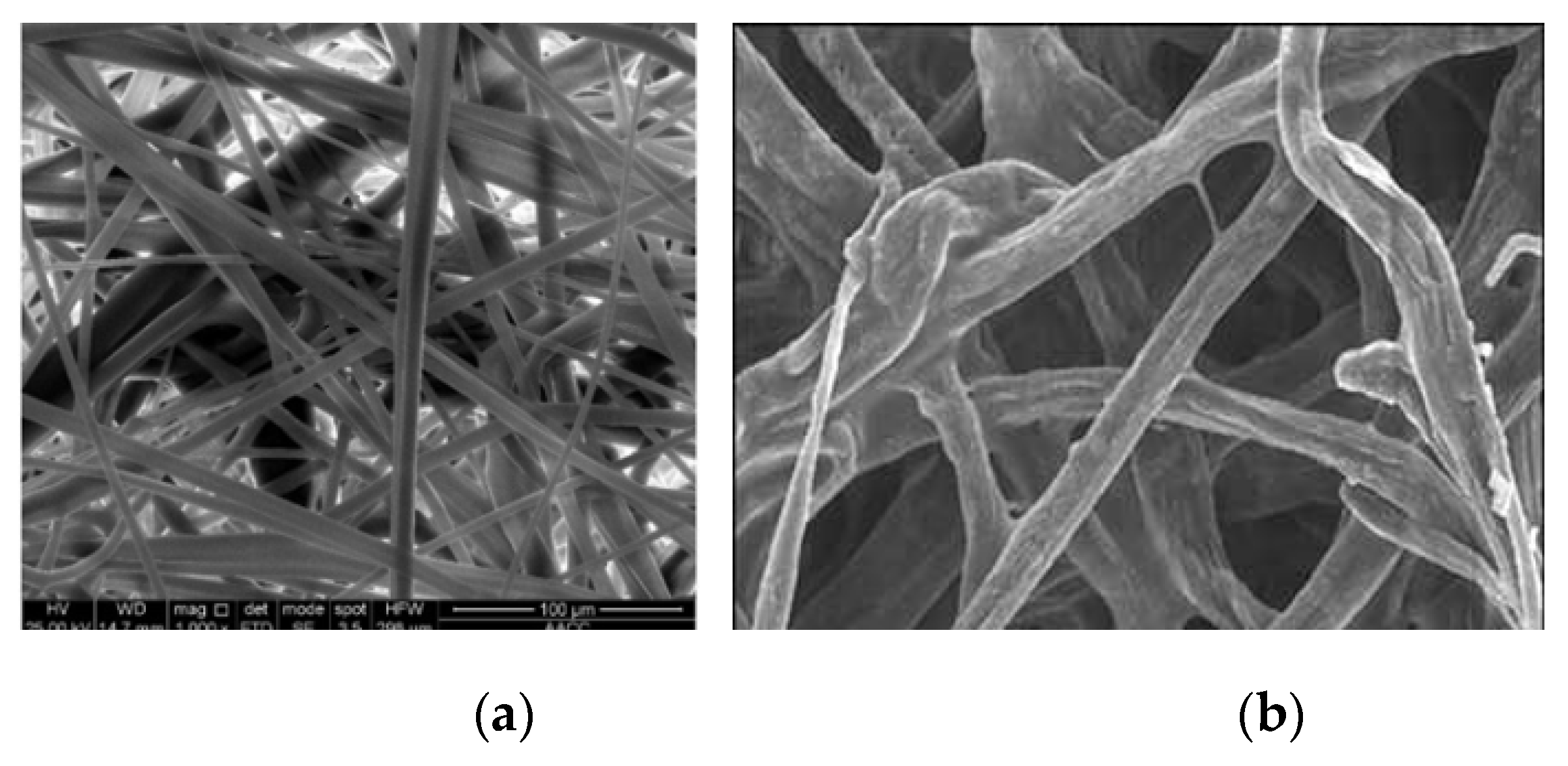

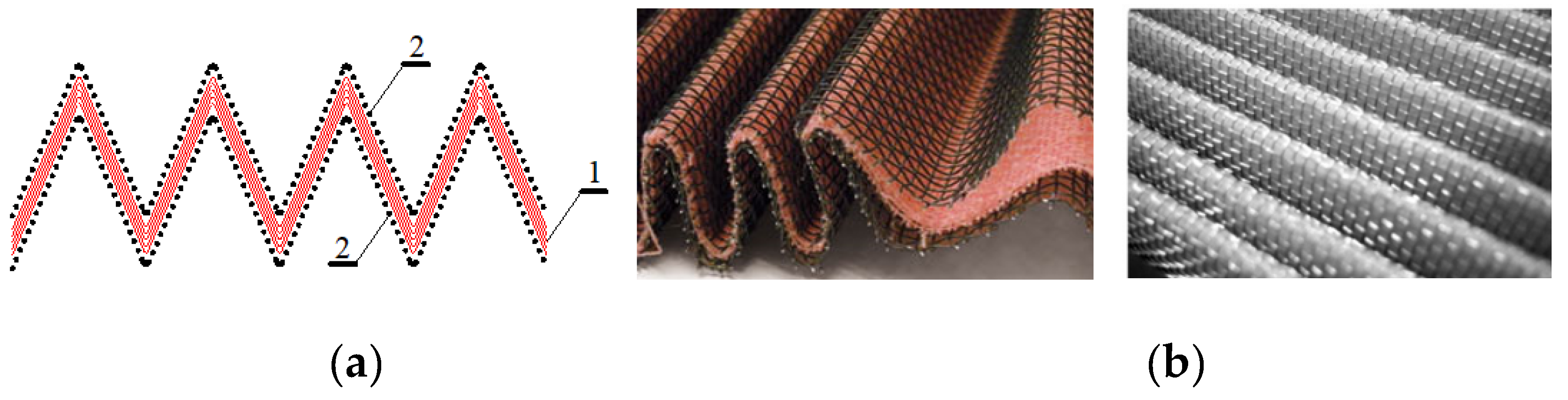

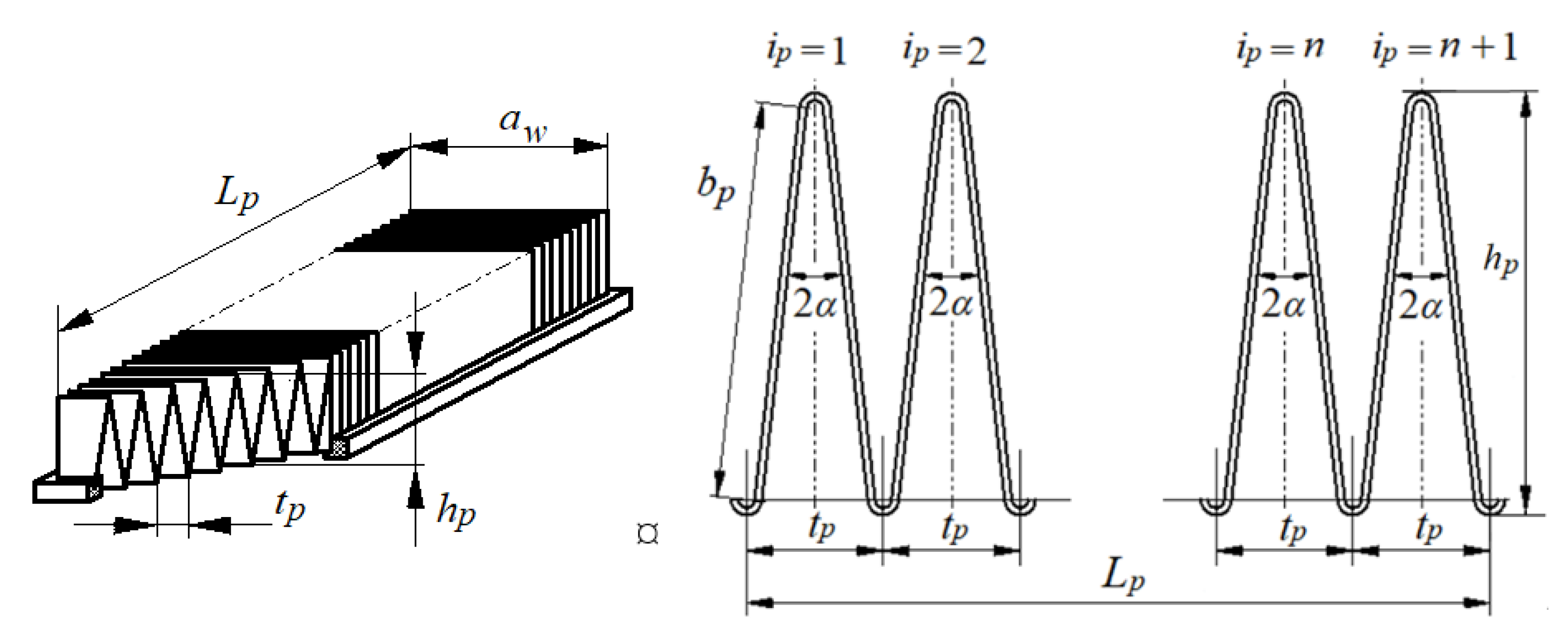

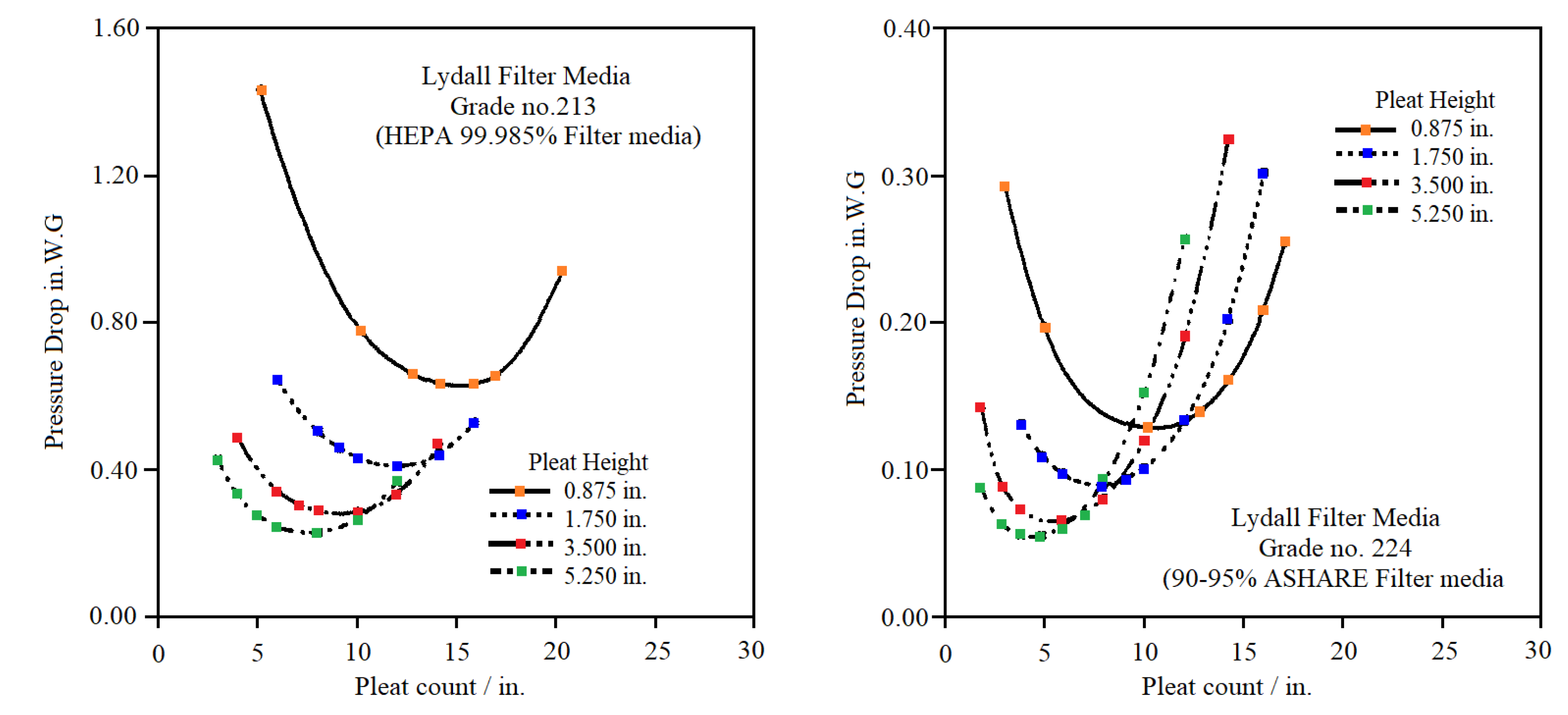

- The basic element of the filter system (IBF) is a panel, where the filter medium is a multi-layer pleated cotton or cotton-synthetic nonwoven fabric impregnated with special preparation and reinforced with metal mesh on both sides. The IBF ensures low pressure drop and very high filtration efficiency, ranging from 99.3% to 99.9%. Optimizing pleat geometry to reduce pressure drop is crucial.

- Dust accumulation on the filter element causes a continuous pressure drop, which reduces the airflow to the engine. When the pressure drop reaches a predetermined limit during flight, the bypass (safety) valve opens, allowing air to flow into the engine. However, the engine is then exposed to solid mineral contaminants drawn in from the ambient air.

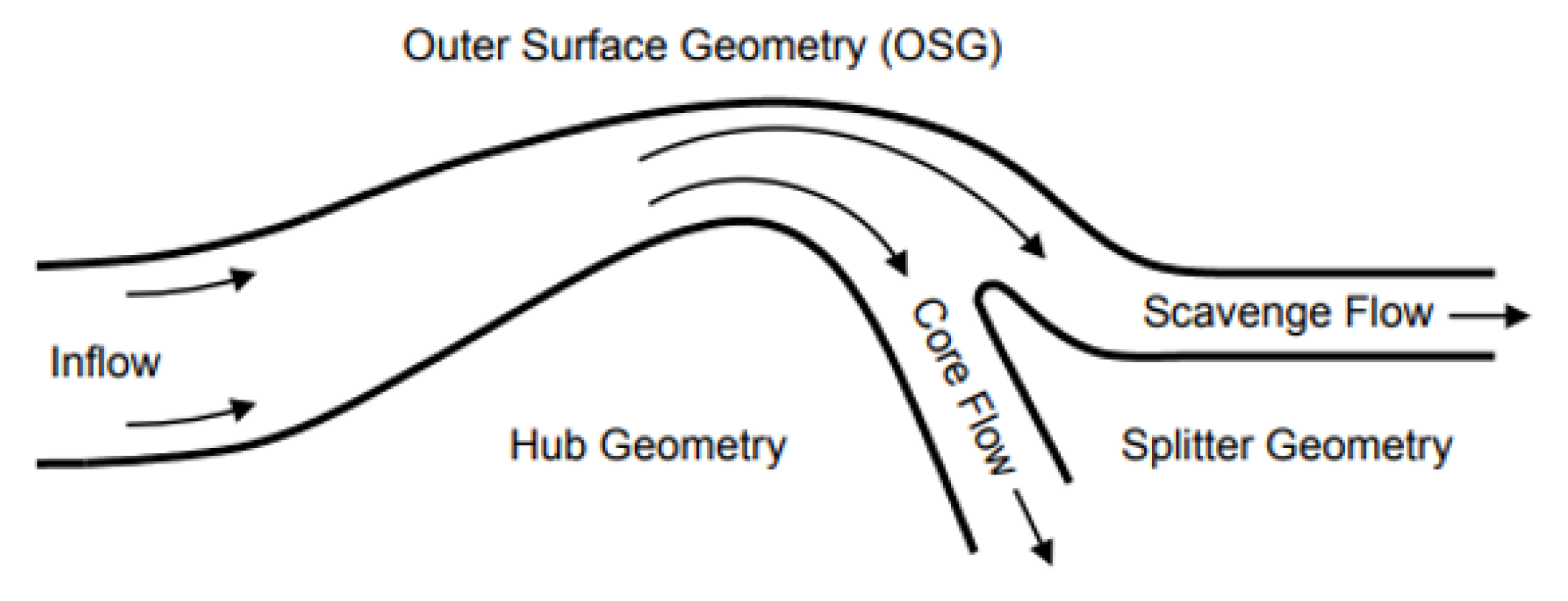

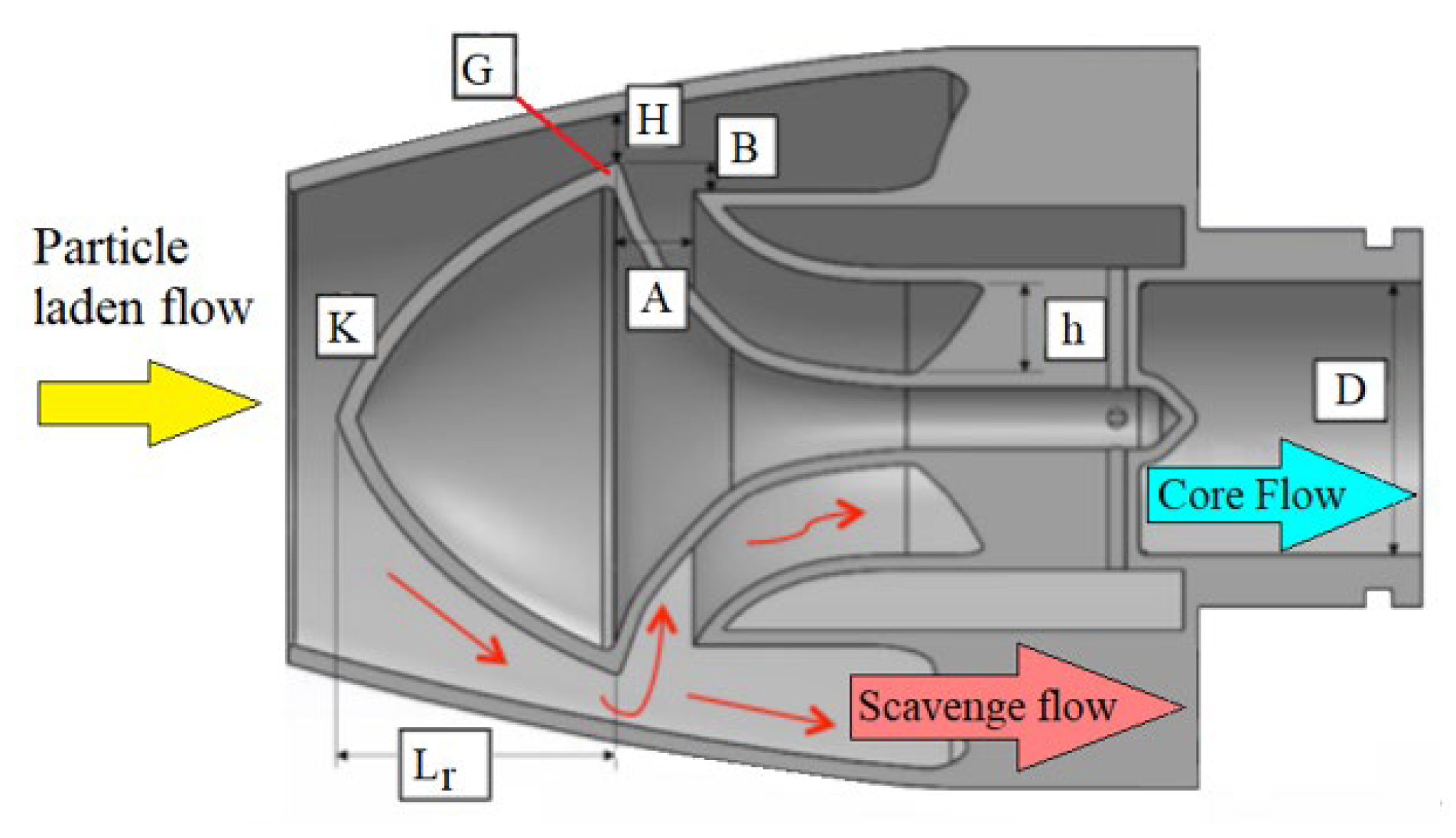

- The IPS filtration system is an air filtration system integrated with the turbine engine. It is characterized by a compact design, low external resistance, and requires no periodic maintenance. However, it has lower separation efficiency (approximately 75-86%) than the VTS and IBF systems. Improved filtration efficiency is achieved through the use of hybrid VTS-IPS and VTS-IBF devices, which achieve efficiency of up to 99% for particles with a diameter exceeding 20 μm and ensure a less pronounced increase in pressure drop, extending the service life of the filtration system.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| P-PR-C | Piston-Piston Rings-Cylinder |

| BDC | Bottom Dead Center |

| EAPS | Engine Air Particle Separation |

| VTS | Vortex Tube Separators |

| IBF | Inlet Barrier Filters |

| IPS | Inertial Particle Separators |

References

- Van der Walt, J.P.; Nurick, A. Erosion of dust-filtered helicopter turbine engines part I: basic theoretical considerations, Journal of Aircraft 1995, 32(1), 106-111. [CrossRef]

- Van der Walt, J.P.; Nurick, A. Erosion of dust-filtered helicopter turbine engines part II: erosion reduction. Journal of Aircraft 1995, 32(1), 112-117. [CrossRef]

- Honeywell AGT1500 - Archived 3/2009. https://www.forecastinternational.com/archive/disp_pdf.cfm?DACH_RECNO=180.

- Schaeffer, J.W.; Olson, L.M. Air Filtration Media for Transportation Applications. Filtration & Separation 1998, 35(2), 124-129.

- Jaroszczyk, T.; Pardue, B.A.; Heckel, S.P., Kallsen, K.J. Engine air cleaner filtration performance – theoretical and experimental background of testing. Presented at the AFS Fourteenth Annual Technical Conference and Exposition, May 1, 2001, Tampa, Florida. Included in the Conference Proceedings (Session 16).

- Pinnick, R.G.; Fernandez, G.; Hinds, B.D.; Bruce, C.W.; Schaefer, K.W.; Pendelton, J.D. Dust Generated by Vehicular Traffic on Unpaved Roadways: Sizes and Infrared Extinction Characteristics. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 1985, 4, 99-121. [CrossRef]

- Barbolini, M.; Di Pauli, F.; Traina. M. Simulation of air filtration for the determination of filter elements. MTZ - Motortechnische Zeitschrift 2016, 5(12), 24-28. [CrossRef]

- Dziubak, T. Zapylenie powietrza wokół pojazdu terenowego. Wojskowy Przegląd Techniczny 1990, 3(257), 154-157. (in Polish).

- Dziubak, T. Research into a Two-Stage Filtration System of Inlet Air to the Internal Combustion Engine of a Motor Vehicle. Energies 2024, 17, 6295. [CrossRef]

- Rybak, P.; Hryciów, Z.; Michałowski, B.; Wiśniewski, A. Assessment of the Impact of Wear and Tear of Rubber Elements in Tracked Mechanism on the Dynamic Loads of High-Speed Tracked Vehicles. Acta Mechanica et Automatica 2023, 17(1). [CrossRef]

- Bojdo, N. Rotorcraft engine air particle separation. A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences 2012. https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/uk-ac-man-scw:183545.

- Szczepankowski, A.; Szymczak, J.; Przysowa, R. The Effect of a Dusty Environment Upon Performance and Operating Parameters of Aircraft Gas Turbine Engines, Conference: Specialists’ Meeting - Impact of Volcanic Ash Clouds on Military Operations NATO AVT-272-RSM-047 At: Vilnius. May 2017. [CrossRef]

- Taslim, M.E.; Spring, S. A Numerical study of sand particle distribution, density, and shape effects on the scavenge efficiency of engine inlet particle separator system, Journal of the American Helicopter Society. 2010, 55(2), 022006. [CrossRef]

- Stallard, P. Helicopter engine protection. Perfusion. 1997, 12(4), 263-267. [CrossRef]

- Jaroszczyk, T.; Fallon, S.L; Liu, Z.G.; Heckel, S.P. Development of a Method to Measure Engine Air Cleaner Fractional Efficiency. International Congress and Exposition Detroit, Michigan March 1-4, 1999.

- Needelman, W.M.; Madhaven, P.V. Review of Lubricant Contamination and Diesel Engine Wear, SAE Technical Paper 881827. 1988, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Diesel Engine Air Filtration. Pall Aerospace, Europa House. 1999.

- Dziubak, T.; Dziubak, S.D. A Study on the Effect of Inlet Air Pollution on the Engine Component Wear and Operation. Energies 2022, 15, 1182. [CrossRef]

- Koszałka, G.; Suchecki, A. Changes in performance and wear of small diesel engine during durability test. Combustion Engines 2015, 162(3), 34-40. [CrossRef]

- Fitch J. Clean Oil Reduces Engine Fuel Consumption, Practicing Oil Analysis Magazine 11-12, 2002. https://www.machinerylubrication.com/Read/401/oil-engine-fuel-consumption. (Accessed 2 January 2025).

- Thomas, J.; West, B.; Huff, S. Effect of Air Filter Condition on Diesel Vehicle Fuel Economy; SAE Technical Paper 2013-01-0311; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Long J.; Tang M.; Sun Z.; Liang Y.; Hu J. Dust Loading Performance of a Novel Submicro-Fiber Composite Filter Medium for Engine. Materials 2018, 11(10), 2038. [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, A. Krzemionka krystaliczna: kwarc i krystobalit – frakcja respirabilna. Podstawy i Metody Oceny Środowiska Pracy 2014, 4(82), 67-128. https://m.ciop.pl/CIOPPortalWAR/file/75268/20150527112518&5.krzemionka.pdf (Accessed 23 July 2025).

- Kurz, R.; Brun, K. Degradation of Gas Turbine Performance in Natural Gas Service. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering 2009, 95-102. [CrossRef]

- Szczeciński, S. Odpylanie powietrza wlotowego. Wojskowy Przegląd Techniczny 1983, 5-6, 236-241.

- Melino, F.; Morini, M.; Peretto, A.; Pinelli, M.; Spina, P.R. Compressor fouling modeling: relationship between computational roughness and gas turbine operation time. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2012, 134 (5) 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Alqallaf, J.; Teixeira, J.A. Numerical study of effects of solid particle erosion on compressor and engine performance. Results in Engineering 2022, 15, 100462. [CrossRef]

- Tabakoff, W.; Hamed, A.; Shanov, V. Blade deterioration in a gas turbine engine. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 1998, 4(4), 233-241. [CrossRef]

- Hamed, A.; Tabakoff, W.C.; Wenglarz, R.V. Erosion and deposition in turbomachinery. J. Propul. Power 2006, 22(2), 350-360. [CrossRef]

- Dzierżanowski, P.; Kordziński, W.; Otyś, J.; Szczeciński, S.; Wiatrek, R. Napędy Lotnicze. Turbinowe silniki śmigłowe i śmigłowcowe. WKŁ Warszawa, 1985, Poland.

- Bojdo, N.; Filippone, A. Operational Performance Parameters of Engine Inlet Barrier Filtration Systems for Rotorcraft. Conference: American Helicopter Society 67th Annual Forum, Virginia Beach, VA, May 3-5, 2011. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266087797.

- Hamed, A.; Tabakoff, W.; Wenglarz, R. Erosion and deposition in turbomachinery. Journal of Propulsion and Power. 2006, 22(2). [CrossRef]

- Filippone, A.; Bojdo, N. Turboshaft Engine Air Particle Separation. Progress in Aerospace Sciences. 2010, 46(5), 224-245. [CrossRef]

- Kozakiewicz, A. Analiza uszkodzeń turbinowych silników odrzutowych, Prace Instytutu Lotnictwa 2011, 213, 224-234.

- Balicki, W.; Chachurski, R.; Kozakiewicz, A.; Głowacki, P.; Szczeciński, J.; Szczeciński, S. Problematyka filtracji powietrza wlotowego do turbinowych silników śmigłowych. Prace Instytutu Lotnictwa 2009,199(4), 25-30.

- Fatal MV-22 crash in Hawaii linked to excessive debris ingestion. https://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/fatal-mv-22-crash-in-hawaii-linked-to-excessivedebr-419484/ (Accessed 28 November, 2024).

- Tabakoff, W.; Hamed, A. Installed engine performance in dust-laden atmosphere. Aircraft Design Systems and Operations Meeting. October 31-November 2, 1984/San Diego, California. [CrossRef]

- Przedpelski, Z.J.; Casadevall, T.J. Impact of Volcanic Ash from 15 December 1989 Redoubt Volcano Eruption on GE CF6-80C2 Turbofan Engines. In Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety: Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Volcanic Ash and Aviation Safety, U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1994, 2047, 129-135. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237216295.

- Chen, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y. The use of axial cyclone separator in the separation of wax from natural gas: A theoretical approach. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 2615-2624. [CrossRef]

- Dziubak, S,; Małachowski, J.; Dziubak, T.; Tomaszewski, M. Numerical studies of an axial flow cyclone with ongoing removal of separated dust by suction from the settling tank, Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 208, 29-51. [CrossRef]

- Dziubak, T., Problems of dust removal from multi-cyclones of engine air cleaners in cross-country motor vehicles. Arch. Automot. Eng. – Archiwum Motoryzacji 2017, 76(2), 37-62. [CrossRef]

- Dzierżanowski, P.; Dziubak, T. Możliwości wykorzystania strumienia spalin wylotowych silnika tłokowego do odsysających układów ejekcyjnych odpylaczy bezwładnościowych powietrza wlotowego, Międzynarodowa konferencja KONES ’96, Zakopane 11-14.09.1996. Poland.

- Dziubak, T.: Problemy odsysania pyłu z multicyklonu filtru powietrza silnika pojazdu mechanicznego eksploatowanego w warunkach dużego zapylenia powietrza. Zagadnienia Eksploatacji Maszyn PAN 2001, 1(125).

- Teng, G.; Shi, G.; Zhu, J.; Qi, J. A numerical simulation method for pressure drop and normal air velocity of pleated filters during dust loading. PLoS ONE 2023,18(2), e0282026. [CrossRef]

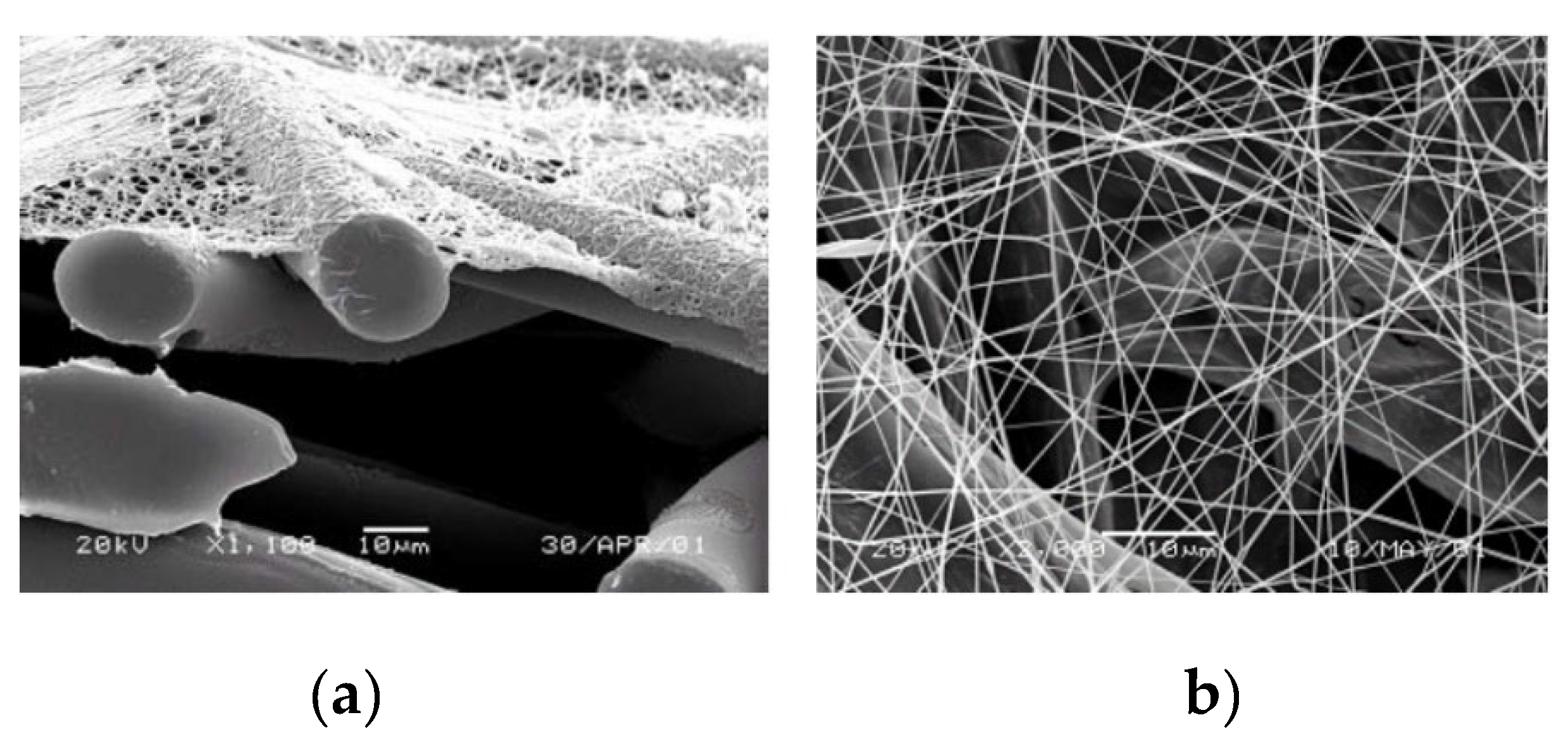

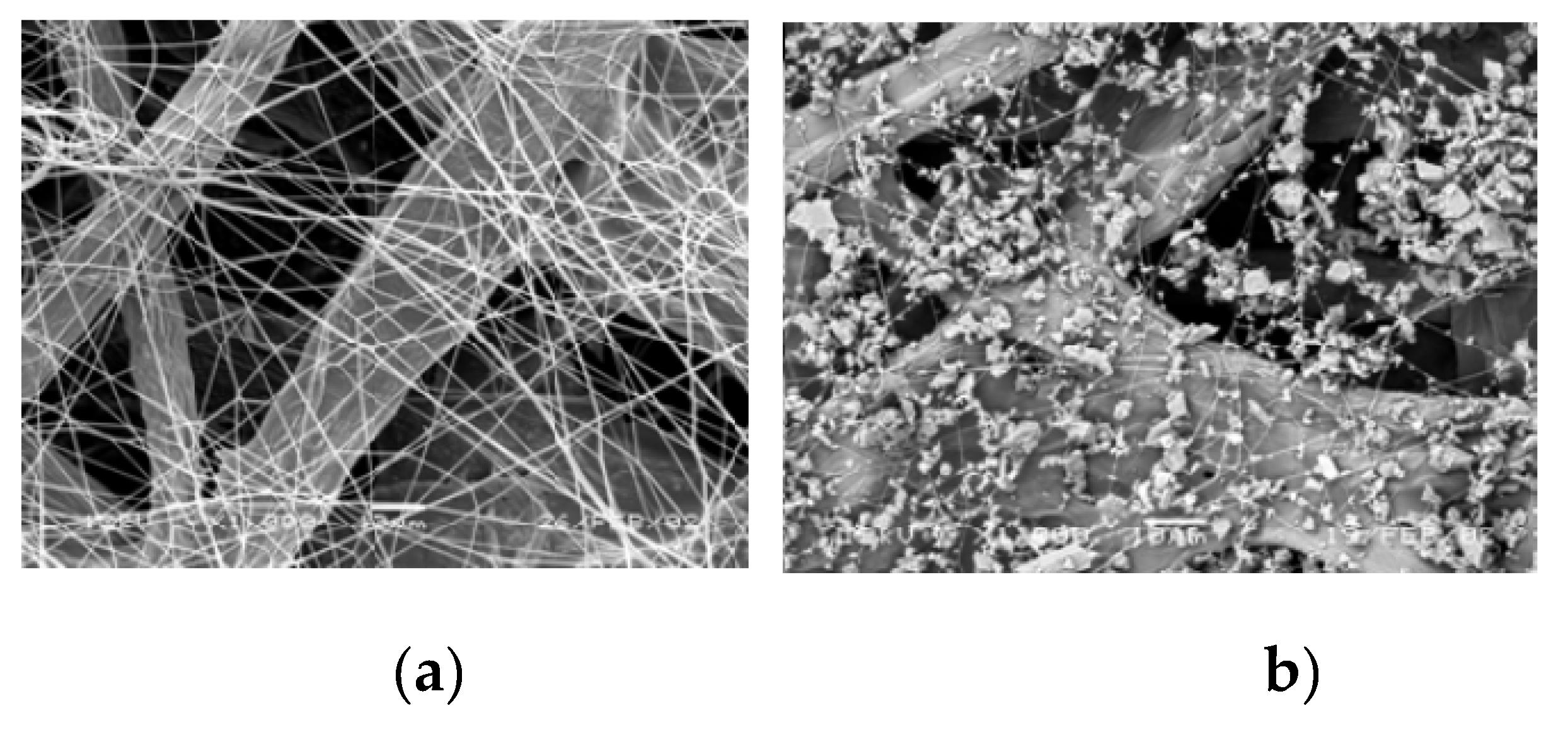

- Jung, S.; Kim, J. Advanced Design of Fiber-Based Particulate Filters: Materials, Morphology, and Construction of Fibrous Assembly. Polymers 2020, 12, 1714. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Han, J.; Wang, F.; Shao, W.; Xiong, R.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, H.; Yang, Y.; Samal, S.K.; Zhang, F.; et al. Electrospun Nanofibers Membranes for Effective Air Filtration. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2017, 302, 1600353.

- Abdolghader, P.; Brochot, C.; Haghighat F.; Bahloul A. Airborne nanoparticles filtration performance of fibrous media: A review. Science and Technology for the Built Environment 2018 24, 648–672. [CrossRef]

- Tennal, K.B.; Mazumder, M.K.; Siag, A.; Reddy, R.N. Effect of loading with AIM oil aerosol on the collection efficiency of an electret filter. Particulate Science and Technology 1991, 9(1-2), 19-29. [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Liu, B. Theoretical study of aerosol filtration by fibrous filters. Aerosol Science and Technology 1982, 1(2):147-161. [CrossRef]

- Payet, S.; Boulaud, D.; Madelaine, G.; Renoux, A. Penetration and pressure drop of a HEPA filter during loading with submicron liquid particles. Journal of Aerosol Science 1992, 23(7):723-735. [CrossRef]

- Barris, M.A. Total Filtration TM. The Influence of Filter Selection on Engine Wear. Emissions and Performance; SAE Technical Paper: 952557; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bugli, N.J.; Green, G.S. Performance and Benefits of Zero Maintenance Air Induction Systems. SAE Technical Paper 2005-01-1139, 2005, 114, 1015–1028. [CrossRef]

- Trautmann, P.; Durst, M.; Pelz, A.; Moser, N. High Performance Nanofibre Coated Filter Media for Engine Intake Air Filtration. AFS 2005 Conference and Expo, April 10-13, 2005.

- Dziubak, T. Experimental Dust Absorption Study in Automotive Engine Inlet Air Filter Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 3249. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; He, W.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, J. PET/TPU nanofiber composite filters with high interfacial adhesion strength based on one-step co-electrospinning. Powder Technol. 2021, 387, 136–145. [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Tang, M.; Sun, Z.; Liang, Y.; Hu, J. Dust Loading Performance of a Novel Submicro-Fiber Composite Filter Medium for Engine. Materials 2018, 11, 2038. [CrossRef]

- Mann-Hummel - wysokowydajne filtry z nanowłókien. https://truckfocus.pl/nowosci/7520/mann-filter-wprowadza-wysokowydajne-filtry-z-nanowlokien. (Accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Grafe, T.; Graham, K. Polymeric Nanofibers and Nanofiber Webs: A New Class of Nonwovens. Presented at INTC 2002: International Nonwovens Technical Conference (Joint INDA – TAPPI Conference), Atlanta, Georgia, September 24-26, 2002.

- Heikkilä, P.; Sipilä, A.; Peltola, M.; Harlin, A. Electrospun PA-66 Coating on Textile Surfaces. Textile Research Journal 2007, 77(11), 864-870. [CrossRef]

- Jaroszczyk, T.; Liu, Z.G.; Schwartz, S.W.; Holm, Ch.E.; Badeau, K.M.; Janikowski E. Direct flow air filters – a new approach to high performance Engine filtration. Presented at Filtech 2005, Wiesbaden, Germany, October 11-13, 2005, Conference Proceedings, Vol. II, 235-243.

- Grafe, T.; Googins M.; Barris, M.; Schaefer, J.; Canepa, R. Nanofibers in Filtration Applications in Transportation, Filtration 2001 International Conference and Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, December 3-5, 2001.

- Stephenson, C.D.; Shohet, H.N.; Speiden, E.F. CH-54A and CH-53A Engine Air Particle Separator (EAPS) Development, Proceedings of the Seventh Annual National Conference on Environmental Effects on Aircraft and Propulsion Systems, Paper No. 67-ENV-7, Sept. 1967.

- Stephenson, C.D. CH-54A Engine Air Particle Separator-3 1/2 Years of Successful Operation. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Presentation at the ASME Gas Turbine Conference & Products Show, Brussels, Belgium, May 24-28, 1970.

- Ghodbane, S.; Beniaiche, A.; Belkallouche, A.; Janssens, B. Numerical Investigation on Separation Efficiency of a Novel Hybrid Engine Air-Particle Separator. Journal of Applied Fluid Mechanics, Vol. 16, No. 9, pp. 1704-1716, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Daldal, A.B. Investigation of inertial particle separator from a broader perspective, M.S. - Master of Science, Middle East Technical University, 2023. file:///D:/!%20-%20USER/tdziubak/Pobrane/ABurakDaldalThesis%20(1).pdf. (Accessed July 24, 2025).

- Bojdo, N.; Filippone, A. Comparative Study of Helicopter Engine Particle Separators. Journal of Aircraft. Vol. 51, No. 3, May–June 2014. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.B.; Shelley, E.; Daniel, S. Design of an Engine Air Particle Separator for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Applications. AIAA SciTech. 4-8 January 2016, San Diego, California, USA. 54th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting.

- Bojdo, N.; Filippone, A. Conceptual and preliminary design of a hybrid dust filter for Helicopter Engines. Conference Paper September 2017. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320734248.

- Engine Air Intake Protection. PALL Corporation, USA 2010. https://www.pall.com/content/dam/pall/aerospace-defense/literature-library/non-gated/Mil_Mi_Centrisep_Brochure_AEMILMIENb_.pdf. (Accessed July 24, 2025).

- Li, W.; Dai, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J. Numerical study on the performance of swirl tube based on orthogonal design. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 33 103620. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Pu, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Song, Z.; Chen, K.; Han, D. Orthogonal experimental design of an axial flow cyclone separator, Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2019, 144. [CrossRef]

- Pall Centrisep® dust protection device for Mi-17/Mi-8MT helicopters. http://www.pall.com/pdfs/Aerospace-Defense-Marine/AEMI17SRU.pdf.

- PUREair System Designed for CH-47 Chinook Helicopters. https://www.pall.com/content/dam/pall/ aerospace-defense/literature-library/non-gated/AECH47SEN.pdf.

- Kim, H.T.; Zhu, Y.; Hinds, W.C.; Lee, K.W. Experimental study of small virtual cyclones as particle concentrators, J. Aerosol Sci. 33 (5) (2002) 721–733. [CrossRef]

- Dziubak, S.; Dziubak, T. Experimental study of an axial flow cyclone with ongoing dust removal from a settling tank. Chemical Engineering & Processing: Process Intensification 2025, 209 110167. [CrossRef]

- Dziubak, T.; Dziubak, S.; Tomaszewski, M. Numerical study of the effect of axial cyclone inlet velocity and geometrical parameters on separation efficiency and pressure drop. Powder Technology, 427, 2023, 118692. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.B.; Shelley, E.; Stralka, D. Design of an Engine Air Particle Separator for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Applications. 54th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting. 4-8 January 2016, San Diego, California, USA.

- Air intake filtration solutions for Helicopters – Inlet Barrier Filter. https://nedaero.com/inlet-barrier-filters-overview/.

- Erdmannsdörfer, H. Trocklenluftfilter für Fahrzeugmotoren-Auslegungs – und Leistungsdaten, MTZ-Motortechnische Zeitschrift, 43, no 7/8, 1982.

- Taufkirch, G. Papierluftfilter in der Einsatzpraxis von Nutzfahrzeugen. MTZ-Motortechnische Zeitschrift, 58(1997), No 4.

- Braun, R.; Sauter, H.; Seggern, J.; Enderich, A. Engine air filtration. MTZ-Motortechnische Zeitschrift, 67, 2006.

- Scimone, M.J. Aircraft engine air filter and method, July 2003. U.S. Patent 6,595,742.

- Chen, D.R.; Pui, D.Y.H.; Liu, B.Y.H. Optimization of Pleated Filter Designs Using a Finite-Element Numerical Model. Aerosol Science and Technology 1995, 23(4), 579-590. http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uast20.

- Rebai, M.; Prat, M.; Meireles, M.; Schmitz, P.; Baclet, R. A semi-analytical model for gas flow in pleated filters, Chemical Engineering Science. 2010, 65(9), 835-2846. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Kang, J.; Wang, D.; Liang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, G.; Wang, H.; Tang, M. Experimental and Simulation Study of Particle Deposition Characteristics and Pressure Drop Evolution in Pleated Filter Media. Processes 2025, 13, 975. [CrossRef]

- Dziubak, T.; Dziubak, S.D. Experimental Study of Filtration Materials Used in the Car Air Intake, Materials 2020, 13(16), 3498. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Li, S.; He, S.; Hu, S.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, F. The Pressure Drop of Fibrous Surface Filters for Gas Filtration: Modeling and Experimental Studies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 350, 127981. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Bai, Y.; Fan, G.; Guo, H.; Shi, P.; Cui, W.; Jin, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; He, J. Large-Scale Fabrication of 3D Gradient Hierarchical Fibrous Filter Materials with Micro-Submicro-Nanofibers for Efficient and Long-Duration Air Filtration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131867. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Sun, W.; Lin, M.; Chen, T.; Duan, K.; Lin, H.; Zhang, C.; Qi, H. Bicomponent Core/Sheath Melt-Blown Fibers for Air Filtration with Ultra-Low Resistance. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 14100-14113. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Nie, J.; Sun, B.; Jiao, T.; Zhang, M.; Song, S. A Cellulose Composite Filter with Multi-Stage Pores Had High Filtration Efficiency, Low Pressure Drop, and Degradable Properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148908. [CrossRef]

- Sawatdee, S.; Botalo, A.; Noinonmueng, T.; Posoknistakul, P.; Intra, P.; Pongchaikul, P.; Charnnok, B.; Chanlek, N.; Laosiripojana, N.; Wu, K.C.W.; et al. Fabrication of Multilayer Cellulose Filters Isolated from Natural Biomass for Highly Efficient Air Filtration for Replacement of Synthetic HEPA Filters. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 194, 216-230. [CrossRef]

- Chagas, P.A.M.; Lima, F.A.; Yamanaka, V.; Medeiros, G.B.; Guerra, V.G.; Oliveira, W.P.; Aguiar, M.L. Short Cellulose Acetate Nanofibers: A Novel and Scalable Coating for Enhancing Nanoparticles Filtration Efficiency of Filter Media. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 358, 130315. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Z.; Gu, H.; Yuan, H.; Cao, S. Numerical Simulation Study on Depth Filtration Performance of Metal Fiber Pre-Filters with Different Pleat Structures. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 425, 113337. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lin, B.; Zhou, H.; Rao, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhou, Q.; Feng, S.; Zhong, Z.; Xing, W. Effect of Pleat Structure on the Air Purification Performance of a Polytetrafluoroethylene/Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Composite Membrane Filter. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 16048-16057. [CrossRef]

- Park, B.H.; Lee, M.-H.; Jo, Y.M.; Kim, S.B. Influence of Pleat Geometry on Filter Cleaning in PTFE/Glass Composite Filter. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2012, 62, 1257-1263. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Long, Z. Modeling Unsteady Filtration Performance of Pleated Filter. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 626–637. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zhu, J.; Qian, F.; Cao, B.; Lu, J.; Han, Y. CFD–DEM Simulation of Particle Deposition Characteristics of Pleated Air Filter Media Based on Porous Media Model. Particuology 2023, 72, 37-48. [CrossRef]

- Teng, G.; Shi, G.; Zhu, J. Influence of Pleated Geometry on the Pressure Drop of Filters during Dust Loading Process: Experimental and Modelling Study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20331. [CrossRef]

- Dziubak, T. Experimental Studies of PowerCore Filters and Pleated Filter Baffles. Materials 2022, 15, 7292. [CrossRef]

- Théron, F.; Joubert, A.; Le Coq, L. Numerical and Experimental Investigations of the Influence of the Pleat Geometry on the Pressure Drop and Velocity Field of a Pleated Fibrous Filter. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 182, 69-77. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Qian, F.; Fang, C.; Zhu, J. Numerical Simulation of Particle Spatial Distribution and Filtration Characteristic in the Pleated Filter Media Using Open FOAM. Indoor Built Environ. 2021, 30, 1159-1172. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kwon, M.; Lee, M. Optimized Pleat Geometry at Specific Pleat Height in Pleated Filters for Air Purification. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e13135. [CrossRef]

- Fotovati, S.; Hosseini, S.A.; Vahedi Tafreshi, H.; Pourdeyhimi, B. Modeling Instantaneous Pressure Drop of Pleated Thin Filter Media during Dust Loading. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 4036-4046. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.M.; Fotovati, S.; Vahedi Tafreshi, H.; Pourdeyhimi, B. Modeling Service Life of Pleated Filters Exposed to Poly-Dispersed Aerosols. Powder Technol. 2014, 266, 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hu, S.; Xie, B.; Jin, H.; Xin, J.; Wang, F.; Zhou, F. Influence of Pleat Geometry on the Filtration and Cleaning Characteristics of Filter Media. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 210, 38-47. [CrossRef]

- Fotovati, S.; Tafreshi, H.V.; Pourdeyhimi, B. A macroscopic model for simulating pressure drop and collection efficiency of pleated filters over time. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 98, 344-355. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.M.; Vahedi Tafreshi, H. A simple semi-numerical model for designing pleated air filters under dust loading. Sep. Purif. Technol, 2014, 137, 94-108. [CrossRef]

- Maddineni, A.K.; Das, D.; Damodaran, R.M. Oil-treated pleated fibrous air filters for motor vehicle engine intake application. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering. 2019, 095440701985037. [CrossRef]

- Dziubak T.: Experimental Testing of Filter Materials for Two-Stage Inlet Air Systems of Internal Combustion Engines. Energies 2024, 17, 2462. [CrossRef]

- Rotorcraft inlet barrier filter systems for airbus h125/as350 series helicopters. https://kadexaero.com/wp-content/uploads/KADEX-Donaldson-Inlet-Barrier-Filter-Systems-for-Airbus-350-STC-Matrix.pdf.

- Du, Z.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wu, F. Sand Discharge Simulation and Flow Path Optimization of a Particle Separator. Entropy 2023, 25, 147. [CrossRef]

- Bojdo, N., Filippone, A. Design Guidelines for Inertial Particle Separators. ASME Journal of Turbomachinery 2025, 147(10) 101013. [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, M.; Mayo, I.; Demolis, J.; Eulitz, F. Analysis of the Bifurcating Duct of an Inlet Particle Separator in Transonic Flow Conditions. ASME Journal of Turbomachinery 2024, 146(11): 111004. [CrossRef]

- Connolly, B. Inertial Particle Separators: Experiments, Simulations, and Design Insights. University of Virginia, Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering - School of Engineering and Applied Science, PHD (Doctor of Philosophy), 2020-07-27. [CrossRef]

- Barone, D.; Loth, E.; Snyder, P. A 2-D inertial particle separator research facility. 28th Aerodynamic Measurement Technology, Ground Testing, and Flight Testing Conference - New Orleans, Louisiana 2012. [CrossRef]

- Balicki, W.; Chachurski, R.; Głowacki, P.; Godzimirski, J.; Kawalec, K.; Kozakiewicz, A.; Pągowski, Z.; Rowiński, A.; Szczeciński, J.; Szczeciński, S. Lotnicze silniki turbinowe. Konstrukcja-eksploatacja-diagnostyka, część I. Biblioteka Naukowa Instytutu Lotnictwa, Warszawa 2010.

- Śmigłowiec W-3 Sokół. https://www.pzlswidnik.pl/pl/produkty/komercjalne-parapubliczne/pzl-w3a. (Accessed October 6, 2025).

- Jaroszczyk, T. Air Filtration in Heavy-Duty Motor Vehicle Applications. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Dust Symposium III Vicksburg MS, September 15-17, 1987.

- Summers, C.E. The physical characteristics of road and field dust. SAE Technical Paper, 250010,1925, 10.4271/250010.1925.

- Thomas, G.E.; Culbert, R.M. Ingested Dust, Filters, and Diesel Engine Ring Wear. Society of Automotive Engineers. Inc. West Coast Meeting San Francisco, Calif. August 12-15, 1968. [CrossRef]

- Bojdo, N.; Filippone, A. Effect of desert particulate composition on helicopter engine degradation rate. 40th European Rotorcraft Forum, Southampton, Conference Paper. September 2014. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265556798.

- Smialek, J.L.; Archer F.A. Garlick, R.G. Turbine Airfoil Degradation in the Persian Gulf War. The Journal of The Minerals. Metals & Materials Society (TMS). 46(12), 39-41. 1994. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).