1. Introduction

Plasmonic nanomaterials are widely employed as platforms for developing molecular sensors, while also enabling investigation of strong near-field and quantum effects. Nevertheless, few nanodevices have reached the market, highlighting a gap between laboratory demonstrations and practical implementation despite numerous publications demonstrating their potential [

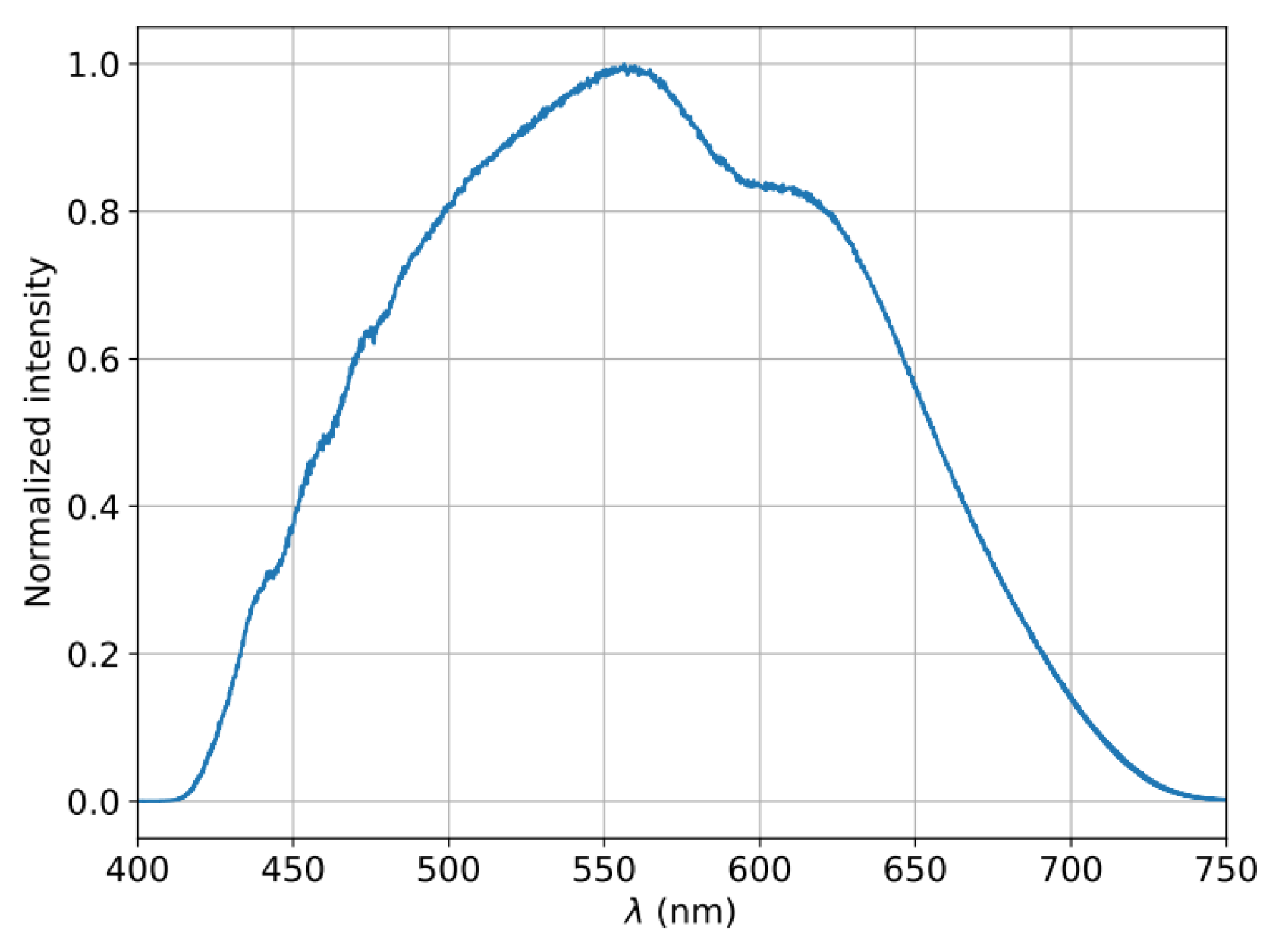

1]. Nanomaterials incorporating noble metal nanoparticles, particularly gold and silver, are among the most popular plasmonic systems because they exhibit remarkable optical responses in the visible range due to localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs). Plasmonic nanoparticles are employed for sensing because their LSPRs are sensitive to subtle changes in the refractive index (RI) of the surrounding environment. Such changes cause a spectral shift of the LSPR band peak or alterations to its line shape, which can be detected via transmittance LSPR spectroscopy [

2].

Among the techniques available for developing plasmonic sensors, physical vapor deposition methods such as sputtering offer a cost-effective and environmentally benign approach. However, as-deposited films typically require post-deposition treatment to achieve the coalescence of metal atoms into nanoparticles of appreciable size. Thermal annealing is a popular approach to induce nanoparticle self-assembly [

3], though it typically lacks spatial control and real-time monitoring capabilities—limitations that motivate the development of alternative annealing strategies.

Previous studies have shown that one-step reactive DC magnetron sputtering deposition produces noble metal clusters with sizes typically limited to less than 10 nm distributed throughout a host oxide matrix [

3,

4]. While the host matrix provides structural robustness to the nanocomposite, it may constrain the mobility and diffusion of gold atoms during self-assembly, with the degree of constraint depending on the selected oxide. Consequently, this approach does not reliably produce noble metal nanoparticles with controlled sizes, shapes, and distributions. Although properly functionalized plasmonic thin films have demonstrated good sensitivity for detecting specific gases [

5] or molecules [

6], the figure of merit of such sensors (S/Δλ, where S is sensitivity and Δλ is LSPR bandwidth [

7]) would improve significantly if the nanoparticle size distribution were narrower, reducing the bandwidth.

Recent studies have demonstrated that short-pulse laser beams tuned to the plasmonic resonance can enable nanoparticle self-assembly with controlled, narrow size distributions [

8]. Recognizing the complementary advantages and limitations of thermal versus laser annealing, we developed a controlled laser annealing system with real-time spectroscopic feedback as a potential alternative to conventional high-temperature thermal annealing. We selected ZnO as the host matrix, primarily for its inherent antimicrobial properties, which could provide additional functionality in antimicrobial sensing applications, as discussed in previous works [

9].

In-situ optical monitoring can foster the understanding of rapid laser-driven material transformations in thin film systems. Previous work has demonstrated that real-time spectroscopic techniques can track both structural and optoelectronic changes during laser annealing. For example, transmission spectroscopy has been used to monitor sub-bandgap laser annealing of CdTe thin films, revealing distinct kinetic processes in defect removal on minute timescales [

10]. Similarly, pulsed UV laser annealing of rare-earth-doped oxide films, including ZnO, has been tracked through simultaneous monitoring of photoluminescence and transmittance evolution, correlating optical changes with crystallization and surface modifications [

11]. Complementary approaches employing micro-Raman spectroscopy have tracked structural transitions in laser-annealed silicon nanoparticles [

12]. However, these prior studies have focused primarily on monitoring intrinsic material changes—defect removal, crystallization, or phase transitions—rather than tracking the deliberate formation and growth of plasmonic nanostructures. Our work extends this body of research by employing pulse-by-pulse optical transmission spectroscopy to monitor the formation and evolution of plasmonic gold nanoparticles within a ZnO matrix through pulsed laser annealing. By combining real-time spectroscopic tracking of the LSPR transmission dip development with complementary structural characterization, we demonstrate that in-situ optical monitoring can provide valuable information to guide the laser-induced coalescence of plasmonic nanostructures.

4. Discussion

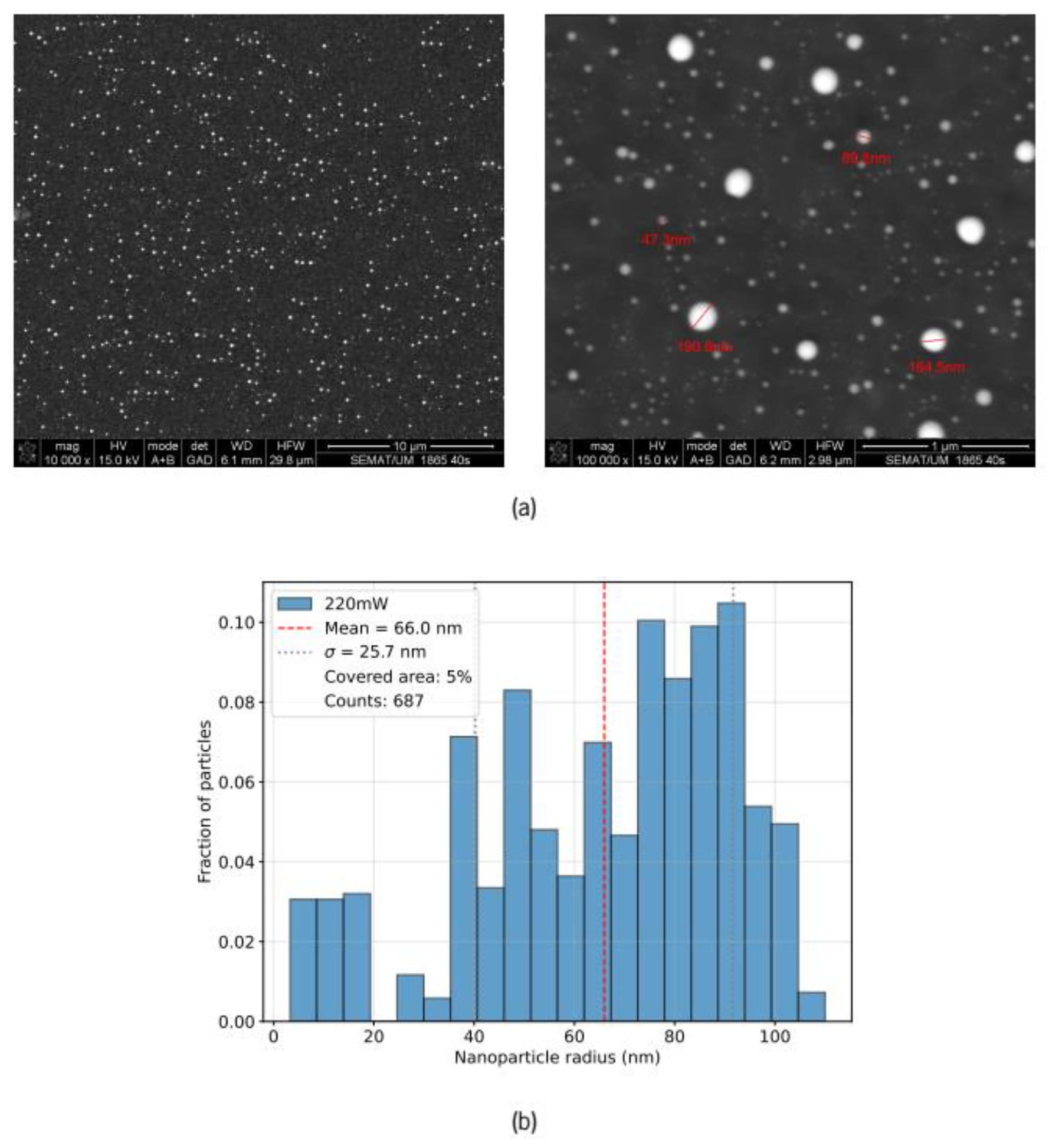

To interpret the distinct evolution paths evident in

Figure 6, we performed baseline simulations of extinction curves for isolated gold spheres as a function of size and dielectric environment. Given the large particle sizes evident in SEM images relative to the 30 nm ZnO film thickness, larger gold particles are expected to protrude significantly from the film. A full simulation of partially protruding particles would require complex three-dimensional finite element modeling with particles positioned relative to the air-ZnO interface. To gain insight into the effect of varying embedding depth, we simulated gold nanospheres with conformal ZnO shells of varying thickness using Mie theory with the Stratify MATLAB toolbox [

16]. This coated-sphere model provides a continuum between two limiting cases: bare gold spheres (surface-protruding configuration with 0 nm shell) and deeply embedded particles (thick shell limit). While idealized, this approach captures the essential physics of particles transitioning from embedded to protruding states during laser annealing.

For material properties, we used the dielectric permittivity of gold from Christy and Johnson [

17] as implemented in Stratify. The complex refractive index for ZnO was obtained from Aguilar et al. [

18] (available as a txt file from RefractiveIndex.info). We enabled Stratify's correction for size-dependent damping due to the finite mean free path of electrons in small gold nanoparticles, which becomes increasingly important below approximately 20 nm radius.

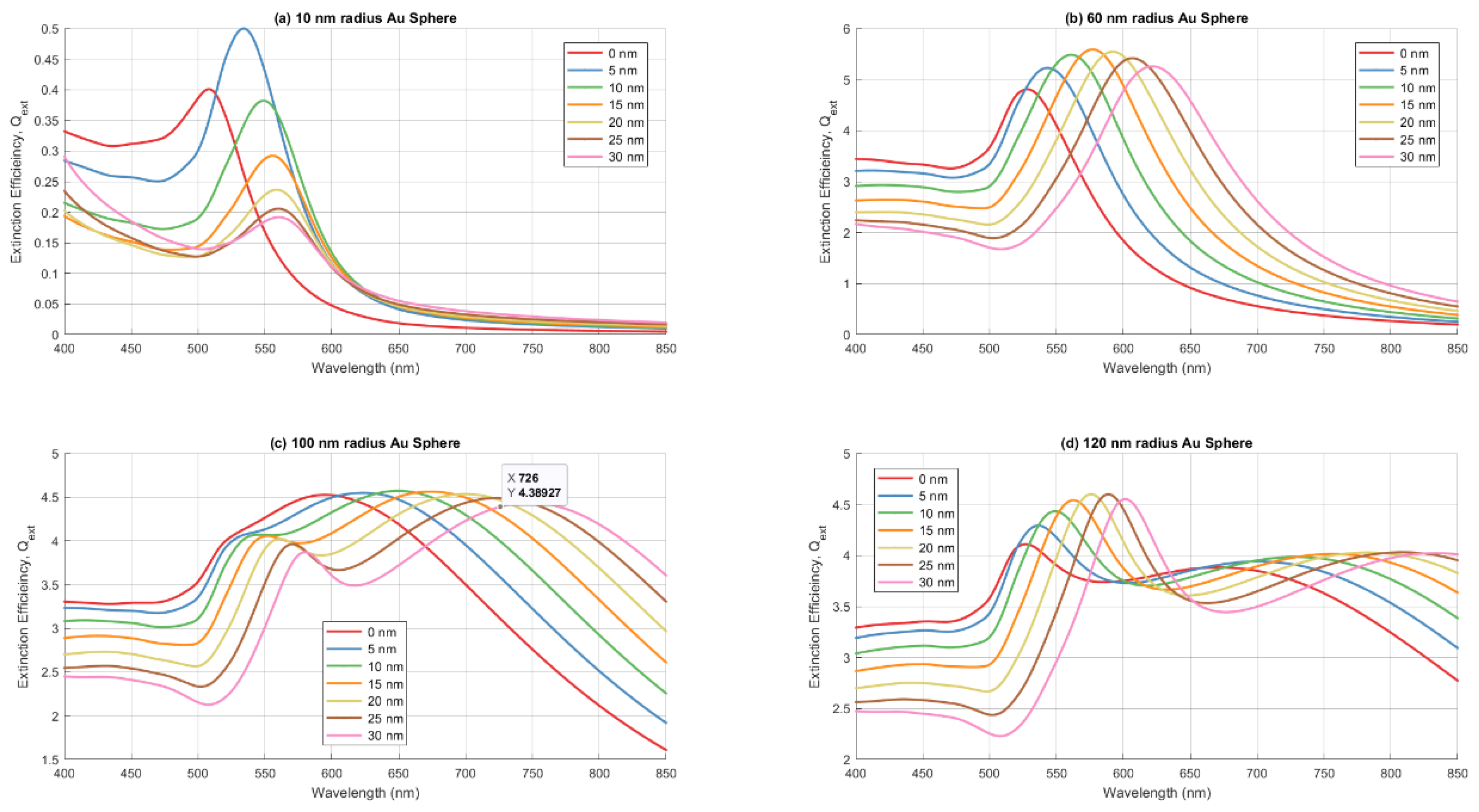

Results of the simulations are presented in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

Figure 7 displays the extinction efficiency (Q

ext), defined as the extinction cross-section normalized by the geometric cross-section of the sphere,

, for four representative particle radii (10 nm, 60 nm, 100 nm and 120 nm) as a function of ZnO shell thickness. ZnO shell thickness ranges from 0 nm (bare gold sphere in air, representing maximum surface protrusion) to 30 nm (nominal ZnO film thickness, representing maximum embedding). These radii were chosen to span the observed particle size range: small (10 nm), intermediate (60 nm), and large (100 nm and 120 nm).

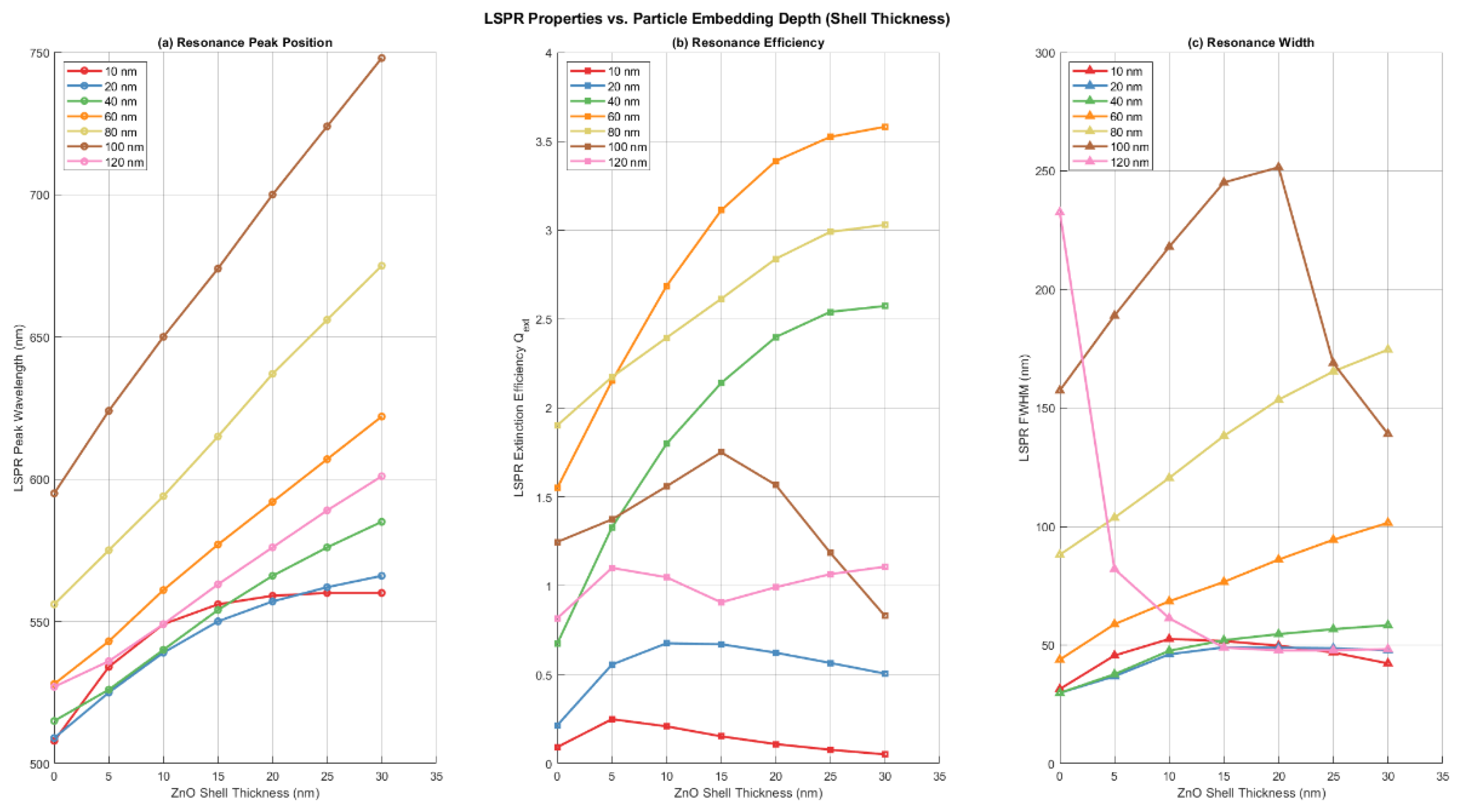

Figure 8 presents the quantitative metrics extracted from the full simulation dataset: (a) peak resonance wavelength, (b) peak extinction efficiency, and (c) resonance full-width at half-maximum (FWHM), all plotted versus ZnO shell thickness for all simulated radii (10 nm, 20nm and 40 to 120 nm in 20 nm increments).

As expected from Mie theory, the LSPR peak shifts to longer wavelengths as ZnO shell thickness increases, reflecting the large real part of ZnO's refractive index (approximately 2). For spheres with radii above 40 nm, this shift is roughly linear with shell thickness; for smaller spheres, the red-shift saturates as shell thickness becomes comparable to the sphere radius. There is also a pronounced size-dependent red-shift of the LSPR resonance with increasing sphere radius.

Uncoated gold spheres (0 nm shell) exhibit distinct size-dependent behavior. Spheres ≤60 nm radius show relatively blue-shifted resonances with peak wavelengths in the 508–528 nm range. The 80 nm and 100 nm radius spheres exhibit peak extinctions at 560 nm and 590 nm, respectively. Notably, the 100 nm sphere shows a secondary blue-shifted peak emerging at ~ 520, creating a bimodal spectrum. For the 120 nm radius sphere, this blue-shifted peak becomes dominant (peak at 527 nm), though a significant red-shifted extinction shoulder persists, extending beyond 800 nm.

The LSPR resonance width broadens as the ZnO shell thickness increases, representing increasing embedding depth. Width also increases dramatically with sphere radius, ultimately splitting into two distinct spectral features for 100 nm radius spheres: a sharp blue-shifted peak between 520 nm and 560 nm and a broader red-shifted feature with maximums from 600nm to 750 nm depending on the shell thickness. For the 120 nm radius sphere, the blue-shifted peak dominates, although the increasingly red-shifted component still contributes significantly to the extinction.

Extinction efficiency shows non-monotonic size dependence. For small to intermediate radii (10–60 nm), extinction efficiency generally increases with both sphere radius and ZnO shell thickness. However, this trend reverses at larger sizes: the extinction efficiency of the dominant LSPR feature drops substantially above 80 nm radius. At 100 nm radius, the extinction efficiency of the primary peak falls to approximately that of a 40 nm sphere—a ~50% decrease from the maximum observed at ~60 nm. The 120 nm sphere continues the trend, with extinction efficiency less than approximately 2× that of the 20 nm sphere. This non-monotonic behavior reflects competing effects: increasing particle size enhances scattering strength, while broadening and damping increase in the intermediate-to-large size regime, reducing peak efficiency. These effects compromise the optical strength precisely where improved resonance sharpness appears (at 100–120 nm with embedding).

This complex behavior illustrates the intricate interplay between particle size and embedding depth in determining resonance position and width. Both factors contribute substantially, and their effects are not simply additive. At large particle sizes (100–120 nm), the interplay becomes particularly rich, generating bimodal spectra with markedly different characteristics for each component.

For sensing applications requiring narrow resonance features,

Figure 8(c) suggests two strategies: (1) limit particle size to <40 nm, maintaining narrow resonances across all embedding depths, or (2) for larger particles (120 nm), maintain substantial ZnO embedding to activate the sharp blue-shifted resonance that emerges in this size range. However, this strategy sacrifices the extinction efficiency available from many small particles (<40 nm), which show the strongest resonances—representing a fundamental tradeoff between resonance sharpness and optical signal strength.

This size-dependent efficiency has important implications for coalescence. Although a single 80 nm sphere requires 8× more gold than a 40 nm sphere, its extinction cross-section exceeds that of eight separate 40 nm particles by approximately 40%. This geometric advantage drives continued coalescence during laser annealing: larger particles produce stronger optical signals even at the cost of reduced peak efficiency. However, the plateau above 100 nm radius, where efficiency drops substantially, sets an upper limit on the beneficial size for further coalescence. The system likely reaches equilibrium when further growth provides diminishing returns in optical strength while sacrificing resonance sharpness.

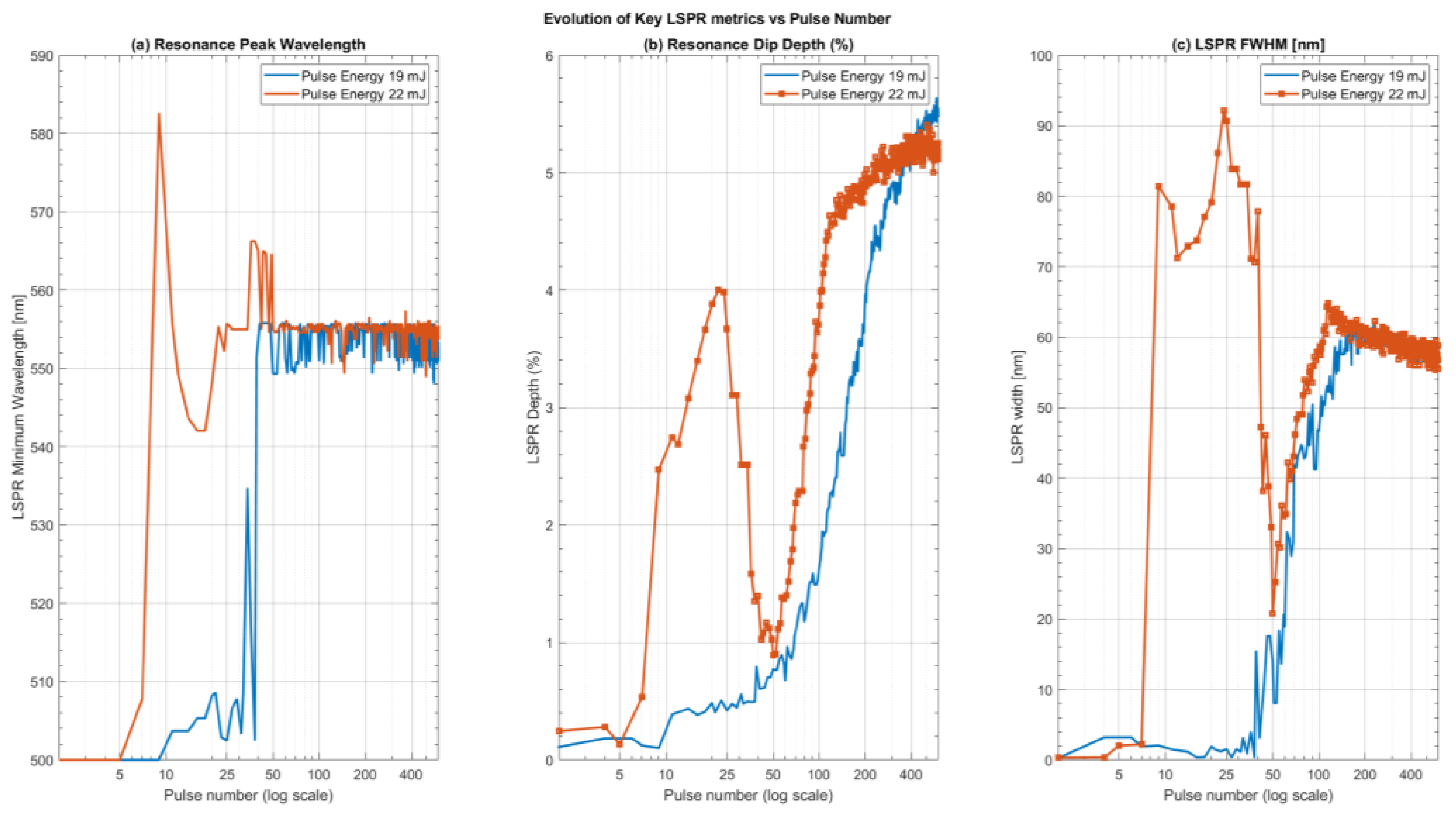

4.1. Evolution of the LSPR Position

The transmission dip depth reflects the oscillator strength of the plasmonic resonance, which increases with particle size and is enhanced by narrower size distributions. However, as our Stratify simulations demonstrate, resonance wavelength is strongly modulated by particle embedding depth. Since the ZnO film thickness (30 nm) is comparable to or smaller than the particle sizes evident in SEM images, one would expect many particles to protrude beyond the air-ZnO interface into air, experiencing blue-shifting from the reduced dielectric environment. Embedded particles, by contrast, experience red-shifting from the high-index ZnO matrix. This interplay between size growth and surface migration suggests that the convergence of both energies to 555 nm reflects complex dynamics between coalescence and preferential protrusion from the ZnO surface.

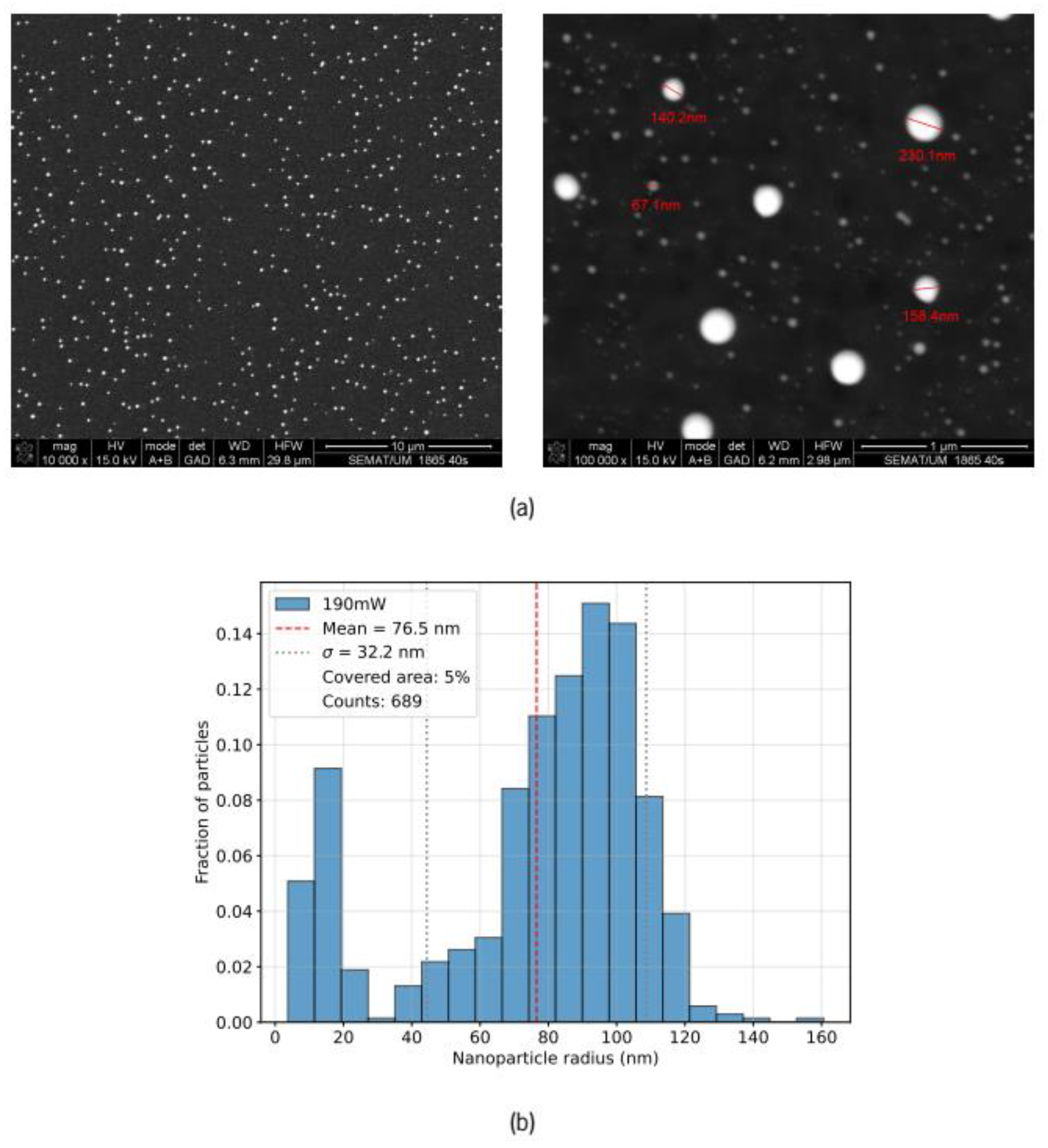

The SEM size distribution for the 19 mJ case reveals approximately 35% of particles with radii ≥100 nm, which produce extremely broad LSPR responses extending to much redder wavelengths, albeit with lower extinction efficiencies. For particles above 120 nm, the secondary blue-shifted resonance emerging in the 520–600 nm region (depending on ZnO shell thickness) might also contribute to the observed 555 nm feature. Additionally, these particles contribute to extended background extinction at wavelengths above 600 nm. Without detailed modeling of the full ensemble (accounting for particle size distribution, spatial arrangements, and potential dipolar coupling) or additional measurements such as variable-angle spectroscopy, it remains unclear which contributions dominate the observed 555 nm resonance: the mixture of smaller protruding and moderately embedded intermediate particles, or the larger 100+ nm particles with their complex bimodal spectra.

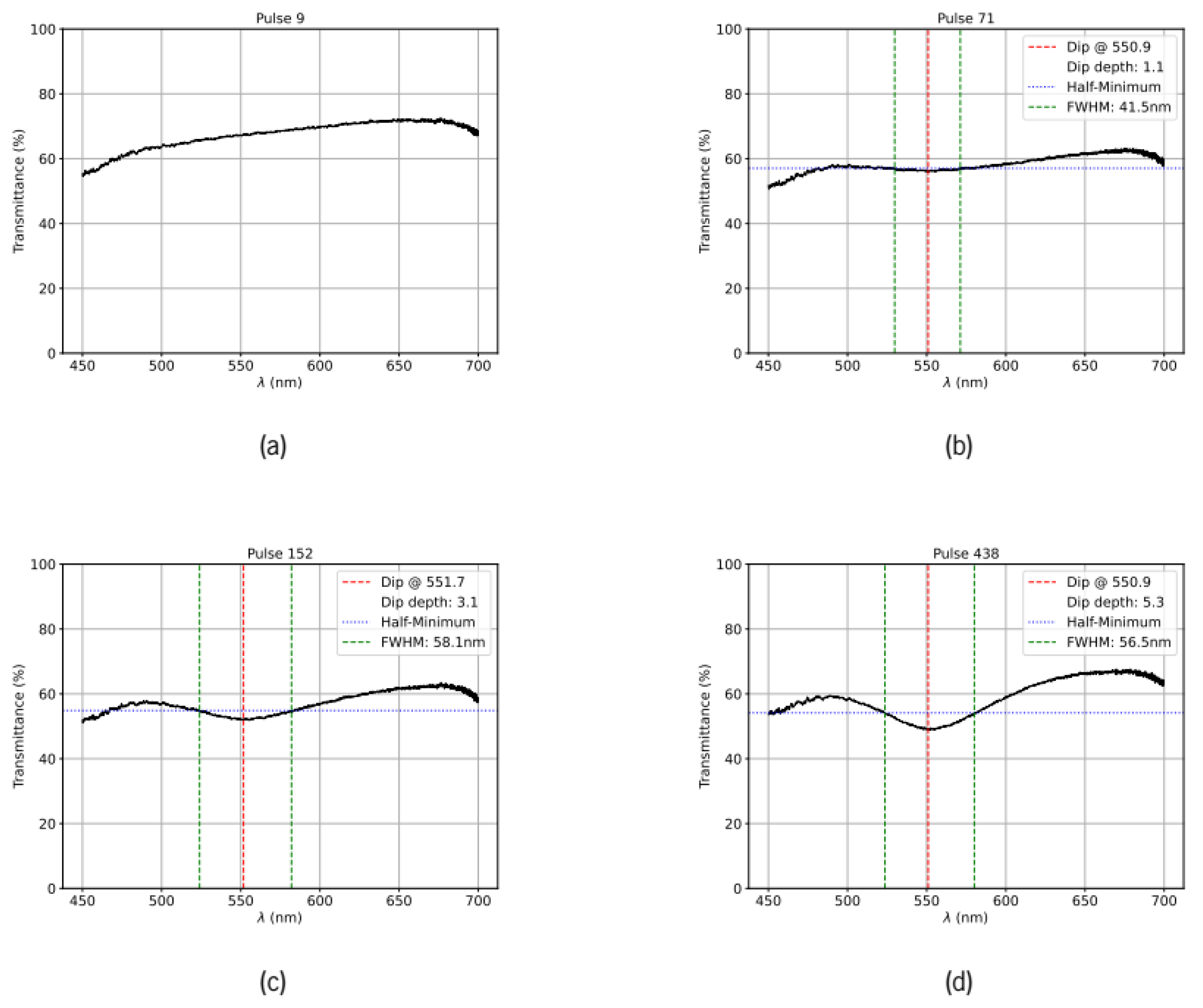

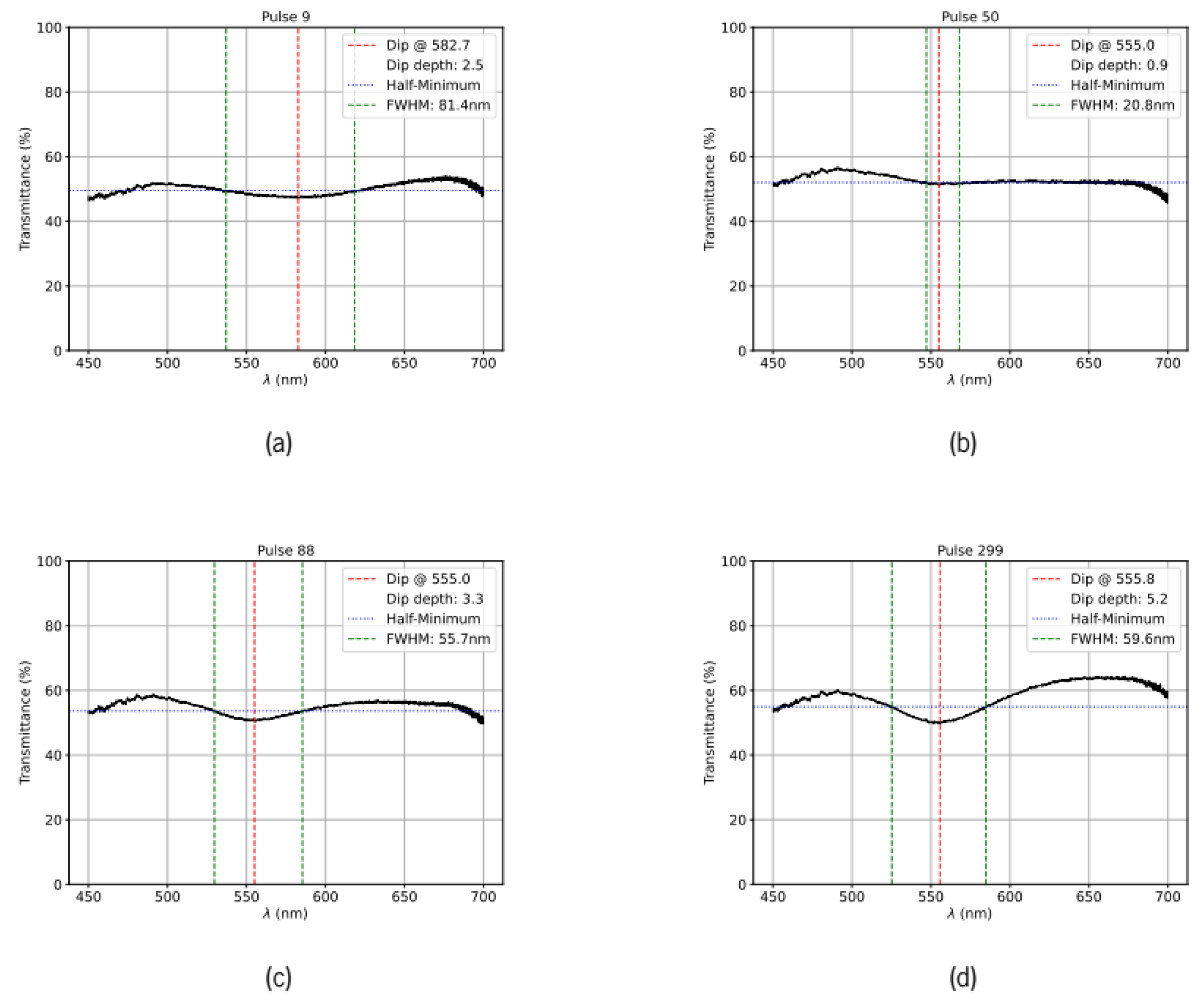

The 22 mJ case reveals markedly different dynamics. The LSPR appears earlier (at ~5 pulses) but exhibits striking wavelength oscillations: it rapidly shifts to the red (582 nm at pulse 9), then abruptly shifts back to the blue (542 nm at pulse 18), before converging to 555 nm by pulse 27. These transient oscillations likely reflect rapid coalescence at higher photon density, transiently forming larger and more heavily embedded particles after the first few laser pulses. After pulse 9, these particles either migrate rapidly to the surface or fragment into smaller particles. By pulse 27, the spectrum appears similar to the 19 mJ case, suggesting that coalescence and surface migration have produced more optically efficient configurations that resonate near 555 nm.

The final SEM size distribution for the 22 mJ case contains only ~11% particles with radii ≥100 nm, compared to ~35% for the 19 mJ case. This dramatic difference suggests that the higher laser fluence inhibits formation of very large particles, possibly through selective thermal effects: transient melting of the largest protruding particles (which retain heat longest) could cause them to fragment or remain smaller, while smaller particles continue to coalesce. The faster convergence to 555 nm (27 vs. 40 pulses) reflects this more efficient pathway toward configurations that resonate near this wavelength.

Notably, both energies converge to the same final wavelength (555 nm) despite dramatically different early-stage dynamics and final size distributions (35% vs. 11% particles >100 nm). This convergence indicates that 555 nm represents a robust state—a broad manifold of particle configurations that collectively produce similar observed resonance regardless of specific size distribution details. Rather than reflecting a unique thermodynamic equilibrium, the 555 nm resonance might emerge from the competing effects of particle size, embedding depth, and non-monotonic extinction efficiency that characterizes the 50–100 nm size range. The specific laser excitation pathway (19 mJ vs. 22 mJ) determines which route through the dual parameters of size and embedding extent the system takes—and crucially, whether it suppresses (22 mJ) or permits (19 mJ) formation of the optically less efficient 100+ nm particles. This strongly suggests that laser energy tuning alone cannot fully optimize particle distributions; selective control of coalescence kinetics—through spatial patterning, temporal pulse sequencing, or substrate engineering—would be required to suppress unwanted size regimes and enhance desired configurations.

4.2. Evolution of the LSPR Depth and the Role of Particle Embedding

Resonance depth reflects the oscillator strength of the ensemble and thus the degree of coalescence. At 19 mJ, depth increases smoothly to ≈5 % in a kinetics-limited fashion, indicating gradual particle growth and migration toward the surface. The continued deepening after wavelength stabilization likely reflects the nonlinear increase of extinction cross-section with particle size.

The 22 mJ case exhibits a more striking behavior in the resonance depth: it rapidly increases to 4% by pulse 24, then paradoxically declines to a minimum of 0.8% at pulse 53—where the transmission spectrum becomes nearly flat with only a slight dip at 555 nm. The initial rapid depth increase reflects accelerated coalescence at high fluence, driving particles toward larger sizes within the ZnO film leading to large red-shifts. However, the subsequent decline in depth suggests that particles then migrate toward the surface more rapidly than at 19 mJ.

At pulse 53, we observe a crossover: particles have grown large enough that they preferentially protrude from the ZnO film rather than remaining embedded, causing a blue-shift that partially cancels the size-driven red-shift. The resulting spectrum exhibits suppressed plasmonic response. Remarkably, the resonance wavelength remains near 555 nm throughout this process, suggesting selective thermal dynamics. Particles protruding into air absorb laser energy with minimal heat dissipation to the environment, reaching very high temperatures—potentially exceeding melting and even evaporation points for large particles. In contrast, embedded particles rapidly lose heat through ZnO's high thermal conductivity (~40 W m⁻¹ K⁻¹). This differential heating favors selective melting and reshaping of protruding portions, and could maintain the characteristic equilibrium embedding depth and thus constant resonance wavelength even as coalescence proceeds.

The recovery phase of the 22 mJ case represents the system settling into configurations where larger, protruding particles produce resonance near 555 nm with a depth of approximately 5%—comparable to the 19 mJ case despite markedly different excitation histories and final size distributions (35% vs. 11% particles >100 nm). This convergence in both wavelength and depth, despite different coalescence pathways, provides further evidence for the robustness of the final state: multiple particle configurations naturally produce similar transmission characteristics, highlighting the fundamental stability of the transmission spectra.

4.3. Evolution of the LSPR Width and Embedding Dependent Broadening

The FWHM evolution reveals the most dramatic differences between the two laser energies and provides the clearest signature of both particle size distribution changes and embedding depth heterogeneity. The resonance width is determined by two competing factors: the inherent size distribution of particles and the distribution of embedding depths in the ZnO matrix. The Stratify simulations show that embedding strongly affects not just resonance position but also resonance width. Particles with a wide distribution of embedding depths—ranging from fully embedded to primarily surface-protruding, exhibit broadened resonance features because different subpopulations resonate at different wavelengths, creating a convolution of spectra. The final width reflects not a single sharp resonance, but a superposition of contributions from particles across a range of sizes and embedding depths.

At 19 mJ, the resonance remains unresolved until approximatly 40 pulses (when particles are still small and mostly embedded). As particles gradually coalesce and grow, the resonance becomes measurable (~10 nm FWHM at pulse 40) and then progressively broadens to ~60 nm by pulse 160. This gradual broadening reflects two simultaneous processes: (1) development of a wider particle size distribution as coalescence proceeds at different rates due to the inhomogeneous distribution of gold particles, and (2) increasing heterogeneity in particle embedding depth as larger particles preferentially proturde above the air-ZnO interface. The modest width narrowing from pulse 160 to 600 pulses (from 60 to 57 nm, approximately 5% decrease) indicates that while coalescence continues (as evidenced by the continued depth increase), the distribution of particle sizes and embedding depths has largely stabilized. This suggests the system is approaching a quasi-stable state.

The 22 mJ series begins with an exceptionally broad LSPR feature at pulse 9 (>80 nm FWHM), indicating a highly heterogeneous ensemble of particles with widely varying sizes and/or embedding depths. Given the position of the LSPR minimum at 582 nm, this initial broadness likely reflects large particles preferentially located at or near the air–ZnO interface. Remarkably, the resonance then sharpens dramatically to only 20 nm by pulse 50—a narrowing of 75%—before gradually broadening again. This dramatic sharpening phase is not observed in the 19 mJ data and cannot be explained by coalescence dynamics alone. The selective thermal effects noted in the depth discussion provide insight into this behavior: differential heating of protruding portions (reaching vaporization temperatures) versus rapid heat dissipation from embedded portions through ZnO's high thermal conductivity strongly favor thermal restructuring of surface-protruding particles. The high laser fluence may preferentially vaporize or fragment the largest protruding particles, suppressing their further growth and leaving a smaller, more uniform particle ensemble. The resulting smaller particles gradually migrate to the surface during continued irradiation, creating a more uniform embedding depth distribution centered near the air–ZnO interface configuration, which reduces inhomogeneous broadening and narrows the spectral width from >80 nm to 20 nm.

The subsequent gradual broadening of the 22 mJ series from pulse 50 onward reflects the resumption of size-selective coalescence: as particles continue to grow on the surface under continued laser irradiation, a new size distribution develops, reintroducing inhomogeneous broadening and causing progressive width increase that gradually mirrors the 19 mJ behavior. By pulse 115, the width (65 nm) approaches that of the 19 mJ case, and both subsequently converge toward ~55 nm by 600 pulses.

Remarkably, both excitation energies evolve toward remarkably similar steady-state optical characteristics—λ ≈ 555 nm, depth ≈ 5 %, and FWHM ≈ 55 nm, despite markedly different size distributions (35% vs. 11% particles >100 nm) and convergence timescales. This robust convergence across all three metrics demonstrates that the system evolves toward characteristic configurations determined by the underlying physics of particle coalescence, thermal effects, and embedding-dependent optical properties, rather than being driven by specific laser excitation parameters. The observation that width converges more slowly than wavelength and depth suggests that optimizing resonance sharpness for sensing applications will require not just tuning laser energy, but also controlling the formation of particle size and embedding depth distributions—through a combination of spatial patterning, temporal pulse sequencing, and substrate engineering.

5. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that real-time, pulse-by-pulse spectroscopic monitoring of laser annealing enables direct observation and the potential to optimize plasmonic nanostructure formation. By tracking the evolution of LSPR wavelength, depth, and width simultaneously, we have illuminated some of the dynamics underlying nanoparticle coalescence in ZnO thin films and identified two distinct annealing pathways that both converge toward the same plasmonic resonance characteristics despite dramatically different intermediate dynamics.

The 555 nm resonance that emerges during laser annealing appears not to be a unique thermodynamic equilibrium but rather a broad manifold of particle configurations (varying in size and embedding depth) that collectively produce similar optical response. Both 19 mJ and 22 mJ incident energies converge to this state (wavelength 555 nm, depth ~5%, width ~55 nm), but via fundamentally different pathways. The 19 mJ case exhibits gradual, kinetically-limited coalescence with progressive surface migration, while the 22 mJ case demonstrates aggressive early-stage dynamics where selective thermal vaporization of large protruding particles suppresses formation of optically inefficient 100+ nm particles. These findings reveal that a global laser energy tuning alone cannot fully control the final nanoparticle distribution; the outcome depends on complex interplay among particle size, embedding depth, film thickness, thermal effects, and coalescence kinetics.

Traditional thermal annealing, as employed by groups fabricating Au–ZnO films for sensing applications, requires blind searching through temperature and time parameter space to optimize LSPR response. This approach is time-consuming, inefficient, and provides no insight into the underlying dynamics. In contrast, pulse-by-pulse spectroscopic monitoring of laser annealing offers decisive advantages: Continuous observation of resonance evolution reveals when optimal conditions are achieved; the ability to correlate spectral evolution with particle coalescence dynamics provides insights unavailable from post-annealing characterization; laser annealing can be applied to specific regions, enabling patterned nanostructures or localized optimization; by understanding how size growth and surface migration compete to determine final resonance characteristics, one can anticipate and potentially mitigate undesired effects.

The insights from this work suggest several promising strategies for further optimization. A key observation is that higher laser fluence (22 mJ) suppresses large particle formation through selective thermal vaporization, while producing the sharpest intermediate resonances (~20 nm FWHM at pulse 50). A dynamic ramping strategy—beginning with high energy to achieve narrow particle size distributions, then ramping to lower energy to maintain these distributions while optimizing coalescence—could potentially produce narrower, more uniform nanoparticle ensembles with enhanced resonance sharpness. This would directly address the sensing applications, where resonance linewidth is a critical figure of merit.

The large particles produced by laser annealing preferentially protrude from the ZnO surface, with substantial fractions extending into air. This geometry is advantageous for functionalization: the protruding portions can be chemically functionalized to detect specific biomolecules or gas-phase analytes without competing interactions with the buried ZnO matrix. Combined with the in-situ monitoring capability to optimize resonance depth and wavelength, laser annealing could produce custom-designed sensing platforms where both the plasmonic properties and the accessibility for functionalization are controlled.

Real-time monitoring enables rapid exploration of incident energy, pulse frequency, and total pulse number, enabling one to explore the landscape of achievable LSPR properties. This could identify parameter combinations that produce particularly desirable characteristics (e.g., narrow linewidth with high extinction efficiency).

Our work demonstrates that in-situ spectroscopic feedback can help transform laser annealing from an empirical, trial-and-error approach into a more controlled, physics-driven synthesis method. By combining real-time monitoring with mechanistic understanding from simulations, we believe that even complex systems with competing effects can be optimized systematically.