1. Introduction

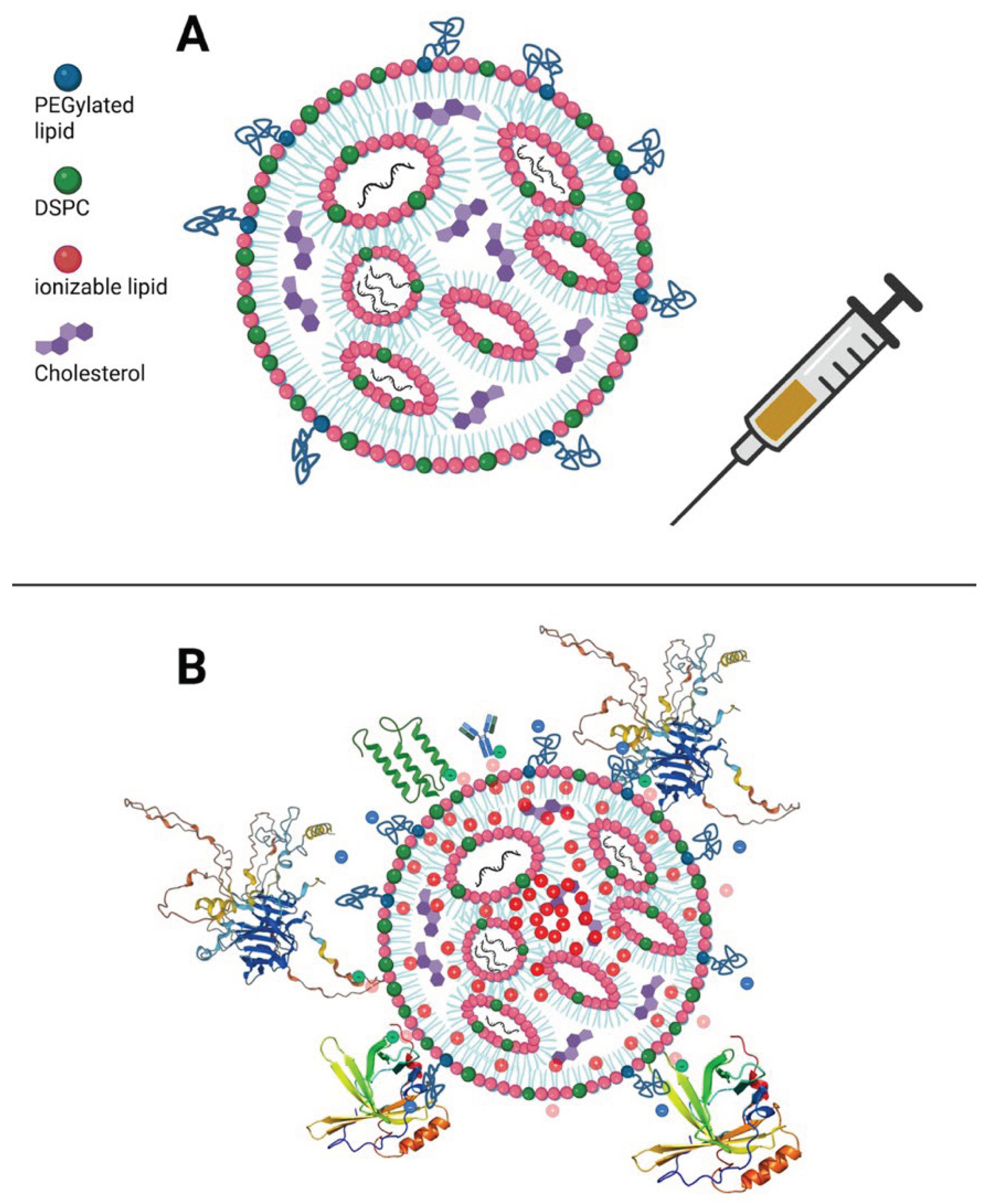

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) used in mRNA vaccine technology are engineered to resemble low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles in many ways, by mimicking their size and structure, so as to exploit their natural mechanisms to gain cell entry through endocytosis. The nanoparticles are crucial for the successful delivery of the vaccine contents. They protect the encapsulated mRNA from ribonucleases and facilitate delivery of intact mRNA to the target site, by improving cellular penetration and facilitating endosomal escape [

1].

Four distinct types of lipids are included in engineered lipid nanoparticles: cationic ionizable lipids, cholesterol, phospholipids, and PEGylated lipids. The cationic ionizable lipids aid in endosomal escape, cholesterol stabilizes the membrane and aids in fusion, and phospholipids stabilize the lipid bilayer [

2]. PEGylation, through the addition of polyethylene glycol, masks the lipid particle's cationic surface charge and provides a hydrophilic stealth coating. PEGylated lipids interact with the negatively charged endosomal phospholipids through the formation of cone-shaped ion pairs [

3]. PEG coatings shield the surface from aggregation, opsonization, and phagocytosis [

4].

There are several ways in which the LNPs can activate the innate immune system. Severe, even life-threatening, adverse reactions can occur due to IgE-mediated allergic reactions that are triggered through induced IgE antibodies to PEGylated particles [

5,

6,

7]. Complement-associated pseudo-allergy (CARPA) due to anti-PEG IgM antibodies can induce mast cell activation and histamine release, resulting in allergic reactions, sometimes severe [

8]. At the cellular level, nanoparticles can bind toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and activate both MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways [

9]. It has been shown that, in THP-1 cells, both Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) are activated [

9,

10]. Based on current evidence, various endogenous receptors can mediate the binding and internalization of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs). Beyond LDL-R–dependent uptake facilitated by ApoE adsorption on conventional four-component LNPs, as described by Dilliard et al. [

11], additional receptor pathways, including VLDLRs and ApoE receptors such as ApoER2 identified by Back et al. [

12], may also contribute to cellular internalization. These mechanisms highlight that LNPs can undergo unintended off-target interactions with multiple receptor systems, not only hepatocyte LDL-R [

13].

Intracellularly, the lipid nanoparticles provoke an immune response that induces the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

10]. This is especially concerning, given that the modRNA particles have been designed to resist degradation, leaving them vulnerable to oxidation damage for a long time [

14]. There is extensive research literature on DNA damage caused by ROS, but it is generally assumed that RNA, although also susceptible and arguably even more vulnerable to many of the same chemical modifications, is generally less significant, because it typically persists for only a few hours. [

15]. Cytoplasmic RNA is especially susceptible in contrast to nuclear DNA, because of the reductive environment of the nucleoplasm [

16]. Due to the modifications to the mRNA done to protect it from degradation (e.g., methylpseudouridine substitution [

17]), it has been shown that the mRNA delivered by the mRNA vaccines can still be present in lymph node germinal centers up to 8 weeks post-vaccination [

18]. Corona formation when the particles engage with serum proteins can influence the nanoparticle’s stability, cellular uptake, and biodistribution, affecting their efficacy and potentially causing an increase in adverse effects [

19].

An essential consideration in understanding the biodistribution of these particles is the route of administration. A comparison between the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines and the approved siRNA-LNP drug Onpattro, used to treat hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (hATTR), was published in 2021 [

20]. Following a single intravenous infusion of siRNA-LNP, 90% of the tracked radioactivity showed up in the liver after just four hours, whereas, after a single intramuscular dose of the mRNA-LNP, radioactivity was concentrated at the injection site for the entire 48 hour measurement period, and did not appear in the liver until after 8-48 hours had elapsed.

The ionizable lipids in LNPs trigger a localized inflammatory response, which attracts immune cells such as neutrophils, monocytes, and dendritic cells to the injection site. These cells then internalize (most likely via transfection) the LNPs, and respond by producing inflammatory cytokines, further promoting an immune response. Following activation, dendritic cells migrate to the draining lymph nodes, where they present the antigen to resident T cells [

21,

22]. In experiments with both mice and primates, a study using PET-CT imaging to visualize the biodistribution of intramuscular delivery of a lipid nanoparticle designed to mimic the Moderna mRNA vaccine, showed that there was rapid trafficking to the draining lymph nodes, presumably via uptake of the cargo into immune dendritic cells [

21]. Of note, the distribution among specific draining nodes was stochastic between subjects and the short imaging window likely precluded detection of secondary accumulation in organs such as the liver at later time points. Through branched DNA assay and the HALO ISH model, Hassett et al. showed that mRNA expression reached highest levels in the spleen at 854ng/g, followed by lymph nodes (155 ng/g), the injection site (98 ng/g), plasma (80 ng/mL), and liver (35 ng/g) in rats [

23].

A remarkable mouse study tracing the fate of mRNA nanoparticles following delivery to a cell revealed that endosomal escape of LNP-mRNA results in the packaging up of the intact mRNA, along with the ionizable lipids, into small lipid particles that are then released as exosomes. These exosomes can then travel through the circulation to distant cells and transfect them with intact mRNA that can then be used to synthesize the encoded protein in the recipient cell. Thus, exocytosis serves as a secondary distribution mechanism as well as a clearance route. This study was published in 2019, and the delivered mRNA coded for human erythropoietin [

24]. However, the same arguments should apply to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines.

The ionizable cationic lipids, both in nanoparticles and the derived exosomes, may alter the zeta potential of blood components, potentially promoting coagulation [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Various cationic lipid formulations have been found to activate coagulation pathways. LNPs can bind to fibrinogen and induce platelet and thrombin activation; these effects are most notable in the lungs following intravenous administration in animal models. [

29]. Such mechanisms could contribute to cases of thrombosis events following mRNA vaccination [

30]. However, ionizable lipids, used in the approved mRNA vaccines, are designed to be neutral at physiological pH and any potential link between lipid components, inflammatory responses, and coagulation abnormalities requires further investigation. The metabolism and clearance of ionizable cationic lipids that becomepositively charged in acidic environments remain poorly understood.

Nanoparticles are not exclusively transported by immune cells. Recent human and animal data reveal that systemic circulation of mRNA-LNPs occurs and is far more dynamic than previously appreciated. In humans, Kent et al. quantified vaccine mRNA species and ionizable lipid SM-102 in serial plasma samples after boosting with a modRNA vaccine [

31]. They found that both intact and fragmented mRNA decreased with nearly identical half-lives, suggesting that systemic clearance is primarily driven by the behavior of lipid-associated complexes rather than free RNA. Ren et al. later demonstrated rapid LNP-lipoprotein exchange after injection, with serum proteins forming transient hybrids (HDL in particular) that decoupled mRNA and lipid kinetics [

32]. While the ionizable lipid SM-102 was nearly cleared from plasma within 24 hours, a small fraction of mRNA remained detectable for days, likely representing dynamic LNP disassembly and systemic removal rather than the persistence of intact particles in plasma. The remodeling of vesicles and exosome-like intermediates identified by Ren et al. is corroborated by Luo et al. [

33], whose single-cell mapping traced fluorescent LNPs and translated modRNA cargo to non-lymphoid targets such as endothelial cells in the heart, accompanied by immune-vascular proteomic shifts.

Together, these studies suggest a transformational sequence from local injection-site release and drainage into lymph nodes to systemic redistribution and plasma reconstruction, in which ionizable lipid chemistry, corona composition and clearance pathways collectively govern where and how transfection and subsequent modRNA translation occur in vivo.

J Di et al. demonstrated (via intramuscular injection in rats) that lymphatic uptake is the major distribution route prior to entering the systemic circulation and subsequently reaching diverse tissues (but not exclusively) depending on their size [

34]. Interestingly, the authors demonstrated that the mRNAs were detected in individual hepatocytes lining the liver sinusoids, whereas in the lymph node, they appeared highly concentrated, and the authors concluded that only released mRNAs might have been stained, whereas those encapsulated within LNPs were likely not detectable. They also found consistent detection of both LNPs and mRNA in circulation, supporting the findings of Kent et al. [

31].

Furthermore, LNPs can transfect a variety of immune cells in the bloodstream, such as dendritic cells and macrophages [

35]. They can also exit the circulation through fenestrated endothelium or transcytose into different tissues depending on the route of administration and the specific LNP formulation, then circulate there as they are exocytosed after initial cellular uptake [

34]. Lipid nanoparticles also induce oxidative stress, which can enhance the release of exosomes (containing the cargo and cationic ionizable lipids) into the external environment and their circulation throughout the body [

36].

A growing body of work [

32,

34] and the synthesis provided by Xu et al. (2025) [

37] indicate that LNP formulations differ markedly in their stability, propensity for lipid exchange, and tendency to remodel in the bloodstream. More stable LNPs, such as those comprising the Onpattro-like formulation, show reduced redistribution [

38], whereas the less-stable LNPs, used in the modRNA vaccines, exhibit greater susceptibility to lipid exchange, fusion, and systemic escape from the injection site. These qualitative differences align with observations across multiple experimental systems [

24,

31,

32], supporting a broader interpretation: LNPs undergo a constellation of simultaneous and overlapping processes, including uptake, extracellular remodeling, intracellular transfection, and exocytosis. The relative contributions depend strongly on formulation and batch, route, and tissue context.

Moreover, Balcorta et al. demonstrated that conventional radiotracing and fluorescent labelling approaches lack the subcellular resolution required to map LNP distribution accurately [

39]. They introduced new peptide based tags that enable reliable visualization of LNP trafficking within cells and tissues This innovative approach, termed SPARKLE (Strategic Peptide Anchored, Retained, and Kept after Lipid Elimination), leverages lysine-rich peptide sequences conjugated to LNPs via maleimide chemistry, ensuring signal retention even after lipid-disrupting processes like delipidation or tissue clearing for precise subcellular and 3D tracking.

Building on these observations, we analyze the transfection process associated with LNP formulations in greater detail and provide a mechanistic framework that underlies the adverse effects observed with these vaccines. In the following sections, we examine the transfection process mediated by LNP formulations and demonstrate that it contributes substantially to the adverse effects documented with these vaccines. We propose a perspective that can explain the heterogeneous and seemingly idiosyncratic adverse events observed following modRNA–LNP vaccine administration over the past 4-5 years [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. In this work, we will consider the basic perspective that LNPs do not act as simple carriers of the modRNA payload but exhibit complex, diverse pharmacodynamic and biological effects.

Several peer-reviewed analyses have characterized post-authorization adverse events associated with the mRNA vaccines, notably myocarditis, neuropathic, and inflammatory responses [

45,

46,

47]. Independent clinical registries have compiled patient-reported outcomes and case documentation that expand the empirical understanding of post-vaccination effects. These data highlight the variability of systemic reactions and motivate deeper inquiry consistent with the LNP-driven perturbation framework proposed here.

The mechanism of action and possible persistence of LNP components, combined with their capacity to release modRNA into the cytosol, result in prolonged cellular stress responses and inflammation. Subsequent translation of the modRNA can lead to high local and systemic levels of spike protein, further amplifying these stress responses and promoting sustained innate immune activation. In this context, the spike protein should be considered primarily as an amplifier and self-assembling driver of these events, since it may be produced in diverse transfected cell types and can circulate differently than after natural infections. Furthermore, subsequent viral exposure after these changes can unpredictably lead to further alterations in the immune response, compounding prior membrane-level dysregulation.

2. Lipid Nanoparticles for mRNA Delivery: Biological Properties and Effects on Cellular Systems

Before we can establish our hypothesis, the pharmacological and biological aspects of LNPs must be examined in more detail.

2.1. Factors Influencing Nanoparticle Bioactivity

Nanoparticles’ high surface area gives LNPs unique properties that influence interactions with proteins and cells, affecting uptake and immune responses. Their behavior depends on the combined physicochemical characteristics of the entire particle, including size, charge, shape, lipid composition, and packing (payload), rather than on individual lipids [

48]. Factors such as lipid unsaturation, branching, payload, encapsulation, stability, and impurities all impact membrane fusion, biodegradability, persistence, safety, and effectiveness [

49]. The structures of COVID-19 mRNA-LNPs remain unclear due to self-assembly and lipid properties. Models vary from multilamellar vesicles with blebs to core–shell structures [

50,

51] with estimates indicating that 12% [

52] to 80% [

53] of LNPs lack mRNA, depending on assay and formulation [

54].

In vivo, a biocorona forms when the LNPs contact biological fluids, creating a dynamic and diverse coating of serum proteins primarily composed of lipoproteins, immunoglobulins, albumin, complement, and coagulation factors that confers a distinct biological identity. It varies by species [

55], and is determined by both LNP characteristics (size, charge, PEG density, rigidity) and host or environmental factors [

56]. In humans, it remains incompletely defined, with ApoE, vitronectin, C-reactive protein, and alpha-2-macroglobulin consistently present [

57]. The protein corona can modulate ligand accessibility and cellular interactions, with ApoE binding shown to alter LNP structure, biodistribution, and modRNA stability [

58]. LNPs remodel in plasma and lymph, involving lipid and protein transfer, fusion with endogenous particles, and PEG desorption [

59]. These changes can influence nanoparticles’ stability, target cell specificity, immune recognition, and biodistribution, influencing their effectiveness and possibly increasing the risk of adverse effects [

19].

2.2. LNP Biodistribution

With these distinctions in mind, it is essential to consider the distribution of LNPs throughout the body and the cell types they encounter, as these factors influence uptake, antigen presentation, and downstream cellular responses. Biodistribution refers to the physical location of LNPs or drugs within the body and does not necessarily indicate cell entry. Transfection involves the uptake and endosomal escape of nucleic acids into cells. Gene expression occurs when intact modRNA is translated into protein, depending on ribosomal activity and protection from degradation. These separate steps are often conflated in studies and regulatory submissions.

Animal models, primarily rat studies, show that LNPs distribute widely because of their physicochemical properties and the formation of a biocorona, primarily accumulating in the liver, spleen, and draining lymph nodes, which are rich in phagocytic cells of the reticuloendothelial system (RES), involving macrophages and monocytes, Kupffer cells, and splenic macrophages [

60]. Hepatocytes are also primary targets, aided by ApoE in the biocorona and liver fenestration. LNPs also reach the spleen and lymph nodes, where uptake by macrophages and dendritic cells supports antigen presentation and enhances the effectiveness of modRNA vaccines. Additional “off-target” accumulation occurs in the heart, lungs, adrenal glands, ovaries, eyes, and other tissues, facilitated by transcytosis or direct penetration [

61,

62,

63]. Targeted cell types include epithelial, endothelial, and basal cells, as well as cardiac and skeletal muscle, bone marrow-derived immune cells, and hepatic stellate cells, highlighting the widespread biodistribution of LNPs [

3,

64,

65,

66].

The route of administration also affects the biodistribution of LNP-modRNA therapy. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines are given intramuscularly. Factors such as syringe pressure, perfusion rate, proximity to blood and lymphatic vessels, local pH, and temperature influence this process [

67]. A European Medicines Agency assessment report summarized the process as follows: “Intramuscular administration of LNP-formulated RNA vaccines results in transient local inflammation that drives recruitment of neutrophils and antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to the delivery site. Recruited APCs can take up LNPs and express the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 through translation, then migrate to nearby lymph nodes where T cell priming occurs” [

68]. Kent et al. demonstrated in humans that the ionizable lipid, quantified via mass spectrometry, and the vaccine modRNA, quantified by qPCR, appear in circulating plasma, peaking between 4 hours and 2 days post vaccination [

31], while Buckley et al. visualized comparable rapid trafficking to draining lymph nodes in non-human primates using PET-CT but did not measure plasma kinetics [

21]. Together, these findings indicate that intramuscular administration establishes an early lymphatic and vascular distribution phase that initiates immune activation before systemic clearance.

2.3. Mechanisms of Uptake

Uptake occurs via both receptor-mediated and receptor-independent mechanisms, often simultaneously, with the protein corona modulating these interactions [

69,

70]. Receptor-independent uptake relies on nonspecific hydrophobic or electrostatic forces, while receptor-mediated pathways, including clathrin-mediated endocytosis, are dependent on the local microenvironment and lipid–membrane interactions. Specific lipid components, such as helper lipids, can alter membrane conformation and signaling to facilitate G-Protein Coupled Receptor (GPCR) engagement without direct binding, and lipoprotein-enriched coronas further enhance internalization [

71]. Successful delivery requires release of the modRNA into the cytosol, a process termed transfection, which is a critical step in intracellular delivery [

72]. Organ fenestrations and LNP apparent pKa primarily govern biodistribution and uptake, while the zeta (ζ) potential influences protein corona formation [

73] (see

Figure 1). Given the diversity of mechanisms, receptors, and cell states within complex biological systems, systematically targeting receptor-driven and/or non-receptor-driven pathways remains highly problematic [

63]. The key challenge is not whether transfection occurs, but how much it occurs and how it is affected by systems biology, and

vice versa.

2.4. Endosomal Escape and Membrane Destabilization Due to Ionizable Lipids

For LNPs carrying modRNA, successful endosomal escape is essential for therapeutic action. After endocytosis, the acidification of endosomes protonates ionizable lipids (e.g., ALC-0315, pKa ~6.1; SM-102, pKa ~6.7), promoting lipid rearrangement, membrane destabilization, and the release of the payload into the cytosol through proton-driven osmotic swelling, also known as the proton sponge effect [

72,

74]. Endosomal damage, evidenced by galectin recruitment, can occur solely from ionizable lipids without cytosolic RNA delivery [

75]. Smaller membrane perturbations induced by LNPs are detected and sealed by the Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport-III (ESCRT-III) machinery. Lipid geometry, such as the conical shape of branched, unsaturated fatty acids, further induces negative curvature stress that facilitates membrane destabilization [

76]. Computational and experimental studies suggest that LNPs can transiently tear membranes, disrupt lipid raft organization, and tether to the endosomal membrane, enhancing escape [

74,

77,

78].

Endosomal escape is highly inefficient, as only approximately 1–15% of internalized LNPs result in gene expression or spike protein production, due to the brief fusion window, typically within minutes after cellular uptake, during endosome maturation [

72,

79,

80,

81,

82]. LNPs that fail to escape are degraded via lysosomal fusion or exocytosed, making endosomal escape a primary bottleneck in modRNA delivery. If modRNA is not released into the cytoplasm, endosomes mature and fuse with lysosomes, where enzymatic degradation of modRNA and lipids occurs; however, accumulation of LNP components can impair lysosomal function, block receptor recycling, create a cellular “traffic jam,” and prolong lipid retention, reducing therapeutic efficacy and potentially causing toxic effects [

72,

83,

84,

85,

86].

Indeed, LNP uptake follows a bell-shaped, nonlinear response influenced by the LNPs themselves and cell-specific factors. Immune cells such as monocyte-derived macrophages and THP-1 cells exhibit limited cytotoxicity compared to other cell types, likely because their phagocytic and endocytic pathways better manage LNP uptake and membrane stress [

87]. This has implications for cell signaling, which is itself a highly dose-dependent process [

88].

2.5. Spread to Distant Sites via Exosomes

Once modRNA escapes the endosome, it can be packaged into naturally secreted membrane-bound vesicles along with ionizable lipids and intact mRNA. These exosomes circulate systemically, transfect distant cells, and enable protein translation, as demonstrated in mice with erythropoietin in 2019 [

24]. In humans, BNT162b2 vaccination induces exosomes carrying spike protein prior to antibody development [

89], and spike-positive exosomes have been identified in cell supernatants [

90], indicating that LNP cargo can redistribute beyond initial target cells and influence systemic protein expression and immune activation. The data suggest that endosomal escape allows modRNA to enter exosomal pathways in a paracrine manner [

91], facilitating the transport of both mRNA and ionizable lipids to distant secondary sites where functional translation is possible.

2.6. LNP Metabolism Leads to Oxidative Stress and Signaling Cascades

The process by which the LNPs disassemble and are metabolized within cells is not well understood. The metabolism of the ionizable lipid is typically described as hydrolysis and clearance [

92,

93], and their fatty acid metabolites can induce toxicity by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) [

85].

Additionally, lipid adduct formation poses an underrecognized risk. Tertiary amine-based ionizable lipids can generate N-oxides and reactive aldehydes during manufacturing and storage, which may covalently modify modRNA, rendering it untranslatable. Moderna first identified such adducts in 2021 [

94] and noted that Tris buffer mitigates their formation [

95]; Pfizer subsequently adopted Tris in late 2021 [

96], raising the possibility that early batches may have been more vulnerable. Upon inoculation, damaged adducted modRNA taken up by cells could be recognized as abnormal or viral-like, possibly triggering inflammatory and interferon responses [

15,

97]. Additionally, reactive aldehydes like 4-HNE from lipid peroxidation are cytotoxic, can disrupt protein folding, generate neoantigens, and promote oxidative stress and lysosomal dysfunction [

85,

98,

99]. However, direct

in vivo evidence for such processes is lacking.

Developers have tested alternative lipids and mitigation strategies [

100], but the long-term persistence [

93], biodistribution [

101], and possible mutagenic risks [

102] of ionizable lipids remain poorly understood.

In silico studies suggest these lipids may localize within the bilayer [

74,

76], further complicating predictions of LNP stability and

in vivo behavior. This is important because, intracellularly, the lipid nanoparticles provoke an immune response that induces the release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

102]. Although present at low levels, RNA–lipid adducts could plausibly influence translation or stress signaling, and the chemical stabilization of modRNA raises the question of whether such lesions might persist in cells longer than expected. This has not been systematically investigated.

Because mRNA modified with N1-methylpseudouridine can persist in lymph node germinal centers for up to 8 weeks post vaccination [

17,

18], it remains worth considering whether lipid–RNA adducts influence its persistence. Similarly, residual bacterial DNA impurities from manufacturing could also form DNA adducts, which could also stimulate an immune response, leading to increased inflammatory signaling [

103]. Therefore, LNP metabolism should be seen not only as producing degradative metabolites but also as a source of bioactive and potentially pro-inflammatory lipid species with lasting biological effects.

2.7. Activation of the Immune System

LNPs can activate the innate immune system in plasma by transfecting immune cells, providing an intrinsic adjuvant-like activity [

86] that aids in antibody production; they can also trigger severe, even life-threatening, adverse reactions. An IgE-mediated allergic reaction can occur via induced IgE antibodies to PEGylated particles on the biocorona [

5,

6,

7]. CARPA can occur due to anti-PEG IgM antibodies, inducing mast cell activation and the release of histamines [

8], leading to acute infusion reactions [

104]. Allergic reactions observed after modRNA COVID-19 vaccination may be mediated by this phenomenon [

105].

While RNA-lipid adducts and residual DNA may affect the persistence of modRNA and immune signaling, the clinically approved siRNA-LNP patisiran (Onpattro®) provides a clinical reference model in humans. Although its ionizable lipid is less biodegradable [

92], endosomal escape is limited (~1%), with transient membrane disruptions, which contribute to slower and decreased cytotoxicity [

87]. Clinically, Onpattro infusions can trigger CARPA, sometimes severely, through complement activation [

106,

107]. However, its hepatotropic biodistribution limits off-target effects to the liver, where mild and generally reversible hepatic enzyme elevations have been observed, possibly reflecting underlying hepatocellular stress that could be masked by PPARα [

108] and PPARγ [

109,

110] activation, consistent with the known anti-inflammatory and metabolic modulatory effects of these receptors observed in renal epithelial cells and in complement factor D-mediated metabolic pathways (see also

Section 4).

LNPs can activate TLR3, 7, 8, and 9 in the endosome [

111]. Additionally, LNPs bind to diverse cell membrane receptors like CRP, TLR4, and TLR2, and can activate NLRP3 [

112]. Moreover, they can also get directly internalized by macro-pinocytosis [

113]. Recently, Baimanov et al. [

114] found anti-PEG antibodies within the LNP corona, and observed complement opsonization that triggered CSF2RB-mediated phagocytosis by human myeloid cells

in vivo, which suggests the protein corona itself may underlie immune responses to PEGylated lipids.

More broadly, proteins such as ApoE can adsorb to LNPs and engage receptors like LDL-R [

115], exemplifying the complex interaction of LNPs on cell membrane uptake. These immune effects emphasize the importance of distinguishing between biodistribution, transfection, and gene expression, and show that LNP-modRNA interactions are nonlinear and highly context dependent, with the potential to produce pathogen-like effects that extend beyond simple cytotoxicity.

3. The Principles Behind How LNP-modRNA was Thought to Work

The original idea behind modRNA technology arose from the problem that mRNA is immediately recognized by the immune system, in particular by intracellular toll-like receptors (TLRs), triggering an immune response that leads to rapid degradation of the mRNA before it can translate into protein [

116]. To avoid these effects, teams such as Karikó and Weissman sought solutions to the issues of increased premature degradation and poor protein yield [

117]. The thought was to suppress cytosolic pattern recognition receptors (PRR) such as the TLRs to avoid an immune response early on [

118]. It was further assumed that, by suppressing TLR activation through specific nucleoside modifications such as N1-methylpseudouridine, and thereby increasing translation efficiency, these issues could be overcome [

119].

However, it was not taken into account that transfection agents such as Lipofectamine can already promote immune stimulation [

120,

121,

122]. Lipid nanoparticles and modified RNA both act directly on the cellular sensing machinery. Moreover, the activation of dendritic cells and monocytes through pattern recognition receptors such as TLR2, TLR4, and TLR7/8 initiates a TBK1–IRF7 signaling axis that drives innate immune programming [

123].

In a recent

in vivo model, it was shown that LNPs alone can drive strong reactogenicity and sickness behavior in mice via TLR4 and MyD88 [

124]. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that TLR engages in crosstalk with other immune receptors, and this itself is decisive for the downstream outcome [

125,

126,

127,

128,

129]. For example, it was shown that TLR-TLR crosstalk in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) elicits both synergistic and antagonistic effects on the regulation of type I and type II interferons, IL-12, and TNF-α [

130].

Furthermore, TLRs participate in context-specific crosstalk with other receptors, such as members of the LDL receptor family [

131,

132,

133]. LDL receptors play an important role in the uptake of LNPs [

134]. Hovland et al. [

132] also indicate that both LDL and the complement system, as well as TLRs, are crucial players in the development of atherosclerosis. Moreover, TLRs engage in crosstalk with membrane lipids [

135,

136].

This may create a paradox when attempting to elicit an adequate immune response through LNP-modRNA injections. On the one hand, cytosolic TLRs are intentionally silenced or even suppressed, while at the same time TLR4 is activated. Moreover, macropinocytosis-like and endocytotic uptake occur in an uncontextualized manner, potentially leading to receptor internalization and/or activation. It appears biologically plausible that the cascade underlying this paradox originates at the membrane level during transfection, leading to profound downstream alterations in cellular signaling, transcriptional profiles, and ultimately protein processing.

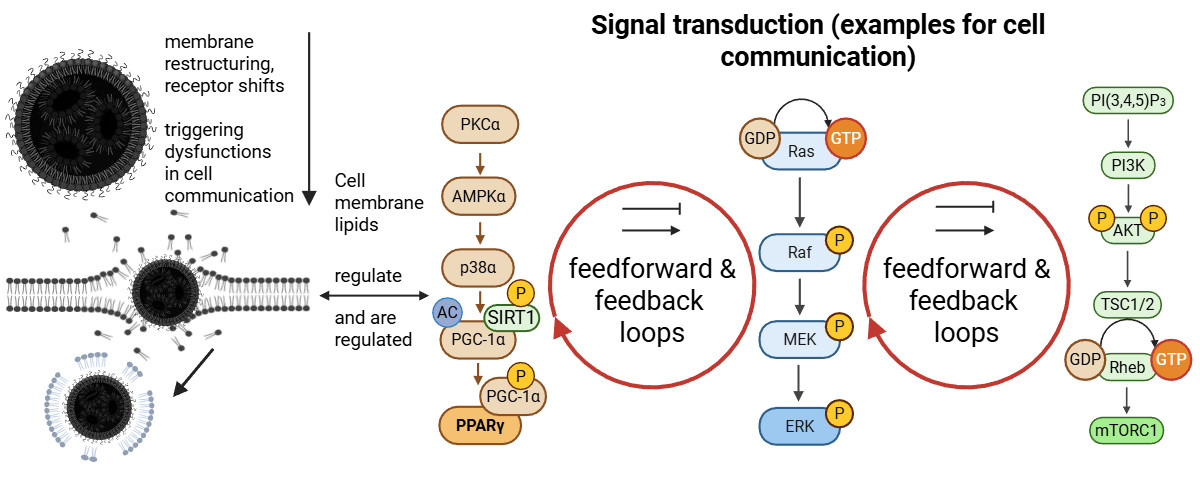

To test this hypothesis, we will first examine the limited omics data currently available to determine whether the cell membrane is affected and whether diffuse changes at the transcriptomic and proteomic levels occur, as would be expected if a broad, nonspecific response takes place. In the final section of this work, we will then propose a mechanistic perspective on disturbances in all the cellular lipid membranes that could result from exposure to the lipid nanoparticles.

4. Omics: Evidence for Membrane Dysfunction Secondary to LNP Transfection

Omics-based methodologies, including transcriptomics, metabolomics, lipidomics and proteomics, serve as exploratory tools for investigating cellular and organismal responses under defined experimental conditions. Rather than providing conclusive mechanistic proof, these approaches generate high-dimensional datasets that facilitate the identification of molecular patterns, pathway perturbations, and candidate mechanisms. In this sense, omics data provide a critical foundation for formulating and testing hypotheses, as their value lies not in definitive causal attribution but in enabling falsifiability through reproducible molecular signatures.

To investigate the intracellular processes potentially triggered by modRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination, omics evidence offers a useful framework for examining the molecular signatures associated with both empty LNPs and modRNA-loaded LNPs in immune cells. Shotgun omics approaches enable a broad mapping of the diverse signaling cascades that may follow LNP uptake, endosomal processing, and subsequent modRNA translation. These datasets, while descriptive in nature, provide starting points for mechanistic interpretation, and they thus serve as a basis for determining if membrane dysfunction occurs as a result of LNP transfection (L-DMD).

To the best of our knowledge, very few omics analyses have been conducted on the effects of the lipid nanoparticles, and none have directly compared vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts over longer periods of time. Transcriptomic, lipidomic, and proteomic studies are of primary interest, as they offer the most direct insights into altered signaling pathways and protein activity states in immune cells following LNP and modRNA transfection.

4.1. Ndeupen et al.—A Pioneering Omics Study

In 2021, Ndeupen et al. published a pioneering

in vivo study, in which they provided an analysis of how a biological system reacts to empty LNPs (eLNPs) [

137]. Their pharmacokinetic investigation, in which wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 (B6) mice were intramuscularly injected with 10 μg of eLNPs, revealed thousands of changes in gene expression patterns. The choice of dosage corresponds to the typical design for pharmacodynamic evaluation [

138,

139].

Regarding the number of up- or down-regulated genes, the study analysis revealed that “with p < 0.05 and FDR [False Discovery Rate] < 0.05, 9,508 genes and 8,883 genes, respectively, were differentially expressed.” A marked upregulation of genes involved in monocyte and granulocyte development, recruitment, and function (e.g., CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL7) was observed. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed a pronounced induction of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, GM-CSF, and IL-6, which are hallmark markers of acute immune activation.

Table 1 displays some of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways that were either up- or down-regulated in response to the lipid nanoparticles. NF-κB was upregulated by 2.5–2.6 log₂-fold. In contrast, the TCA cycle and PPAR signaling pathways were markedly downregulated, with an approximate 2.0 log₂-fold reduction in expression. The upregulation of genes associated with TLRs, NOD-like receptors, and RIG I-like receptors suggests a robust system-wide immunological response. Hematopoietic cell lines, in particular, showed a more than 2 log₂-fold increase in gene expression, indicating pronounced activation within stem and progenitor compartments that may be driven by the combined signaling of TLRs, NOD receptors, and RIG I pathways and/or the internalization pathways of the LNPs.

4.2. Upregulation of Multiple Inflammatory Markers

The simultaneous upregulation of IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-17 is notable, since these cytokines form a pro-inflammatory axis frequently implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune and chronic inflammatory conditions [

150]. While IL-6 can modulate autophagy in the context of oxidative stress [

151], and IL-1β levels may be influenced by autophagic clearance of pro-IL-1β [

152], their elevation in this setting more likely reflects a broader integration of NLRP3-inflammasome activation [

151], NF-κB signaling, and MAPK pathway dysregulation [

153,

154,

155]. Similarly, β-chemokines such as CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, and CCL7 contribute not only to immune cell recruitment [

156,

157], but may also intersect with autophagy-related transcriptional regulation (e.g., via FOXK1) [

158,

159]. These mechanisms, in concert, could promote maladaptive immune activation and, under chronic conditions, create a milieu favoring autoimmunity or other pathogenic sequelae.

Interestingly, Forster III et al. [

160] demonstrated that lysosomal disruption triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome cascade, implicating potential p38-MAPK dysregulation, as previously reported by Shin et al. [

161] and shown by Lv et al. [

162]. These findings align with the increased phagosome-related expression changes observed by Ndeupen et al. [

137].

4.3. Downregulation of PPAR and AMPK Signaling

The data of Ndeupen et al. show downregulation of both PPAR pathways and AMPK signaling [

137]. Given that PPARγ is a central regulator of lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, and anti-inflammatory signaling and is modulated through AMPK-dependent phosphorylation [

163,

164], the strong downregulation suggests disruption of homeostatic lipid and energy control. Such suppression, as reported under inflammatory or stress conditions [

165,

166,

167], may exacerbate NF-κB activation (as shown by the data) and contribute to chronic inflammatory or degenerative outcomes. The expression pattern is indicative of MAPK pathway dysregulation that affects PPARγ phosphorylation and signaling [

166,

167]. Notably, in macrophages, PPARγ regulates inflammatory gene expression [

166]. Ballav et al. highlight that partial PPARγ dysregulation can broadly disturb cellular metabolism and signaling, influencing disease fate decisions across multiple tissues [

168].

4.4. Downregulated Xenobiotic Metabolism by Cytochrome P450 Enzymes

Another notably downregulated KEGG pathway identified by Ndeupen et al. was the metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes [

137]. Approximately 80% of all drugs are mainly metabolized by CYP isoforms belonging to the CYP1, 2, and 3 families, which are primarily expressed in the liver [

169]. Because CYPs are among the most diverse catalysts in biochemistry, they contribute to variations in drug responses among individuals, influenced by genetic and epigenetic factors, environmental elements such as gender, age, and disease, as well as pathophysiological aspects. Significantly, CYPs can be inhibited or induced by other drugs and metabolites, drug-gene interactions, and by inflammatory cytokines.

CYP enzyme downregulation tends to correlate with rises in pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-1α, and IL-1β [

170]. In fact, inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and interferon-γ induced by both infection and vaccination have been shown to suppress multiple hepatic CYP isoenzymes, most notably CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 [

171]. For the modRNA vaccines, case reports and cohort analyses document clinically relevant changes in clozapine pharmacokinetics post vaccination, in some cases leading to neutropenia and hospitalization [

172,

173,

174].The mechanism is consistent with inflammation-mediated suppression of CYP enzymes, particularly CYP1A2 and CYP3A4, central to clozapine metabolism [

175]. Comparable effects have been reported for other CYP metabolized drugs, including statins, benzodiazepines, antiepileptics, and immunosuppressants, which are predominantly CYP3A4 [

176] or CYP2C9 substrates [

177].

Transient suppression of these pathways could significantly alter drug exposure, due to the robust innate inflammatory response following modRNA vaccination. Pharmacokinetic interactions studies specific to modRNA vaccines remain scant, and clinicians might be unaware of these potential dynamics. Furthermore, recent findings suggest that the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and PPARγ regulate CYPs in crosstalk via mTORC1 [

178] indicating that inflammatory or metabolic stressors could simultaneously influence detoxification, lipid homeostasis, and cellular energy metabolism. CYP enzymes also perform crucial biological functions, including cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism, vitamin D activation, and the synthesis of prostacyclins and thromboxanes from arachidonic acid [

179]. These pathways could likewise be perturbed following modRNA vaccination, though comprehensive studies have yet to be reported.

The magnitude of CYP downregulation observed following modRNA vaccination appears greater than would be expected from a conventional vaccine-induced inflammatory response. Clinically significant changes in drug levels due to cytokine-mediated CYP suppression have otherwise been observed predominantly in patients with severe systemic inflammation, such as sepsis, major trauma or critical illness, where C-reactive protein (CRP) levels often exceed 100 mg/L [

180]. The observation of comparable pharmacokinetic perturbations in vaccinated individuals suggests that the inflammatory burden imposed by the modRNA platform may, in some cases, approach the intensity of these pathophysiological states [

181]. Such a response to mRNA vaccination suggests the need to characterize both the acute-phase intensity and resolution of post-vaccination inflammation, especially in those receiving drugs with a narrow therapeutic range.

4.5. Non-Canonical Transciptomics and Proteomic Alterations—Are the TLR4 Reactions Decoupled?

The observations of Ndeupen et al. [

137] are consistent with those made by Zelkoski et al. [

9], showing that empty LNPs trigger TLR4-dependent signaling that bifurcates into a strong MyD88–NF-κB response and a parallel, though weaker, TRIF-mediated IRF activation. Their KEGG GSEA analysis revealed that JUN, a component of the AP-1 transcription factor complex activated via the JNK-MAPK cascade downstream of TLR4–MyD88 signaling, exhibited a 1.93-fold log₂ expression change, whereas the JAK-STAT axis, typically associated with interferon signaling, showed a more modest 1.13-fold log₂ change. Taken together, the results by Ndeupen et al. and Zelkoski et al. show a biased TLR4 dual-pathway activation pattern which should be considered as divergent. These results suggest a decoupled TLR4 dual pathway activation, which is in line with the above discussed observations. Decoupling of the TLR4 pathway starts upstream at the cell membrane, and this potentially supports our L-DMD hypothesis.

Another study supporting this conclusion was published by Luo et al., investigating proteomic alterations induced by lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) without mRNA cargo. The authors compared cargo versus no-cargo LNPs versus phosphate buffered saline [PBS] controls [

33]. They detected 375 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs), of which 240 were upregulated and 135 downregulated in the no-cargo LNP group. These changes were linked to metabolic processes, particularly ribosome function, protein translation, and RNA metabolism, as determined by Reactome pathway analysis. Specific markers, including Ribosomal Protein (Rpl)11, Rpl15, Eukaryotic Initiation Factor (Eif) 4b, Eif2b3, Ribosomal Protein (Rps) 6, and Rps2, were found to be differentially regulated.

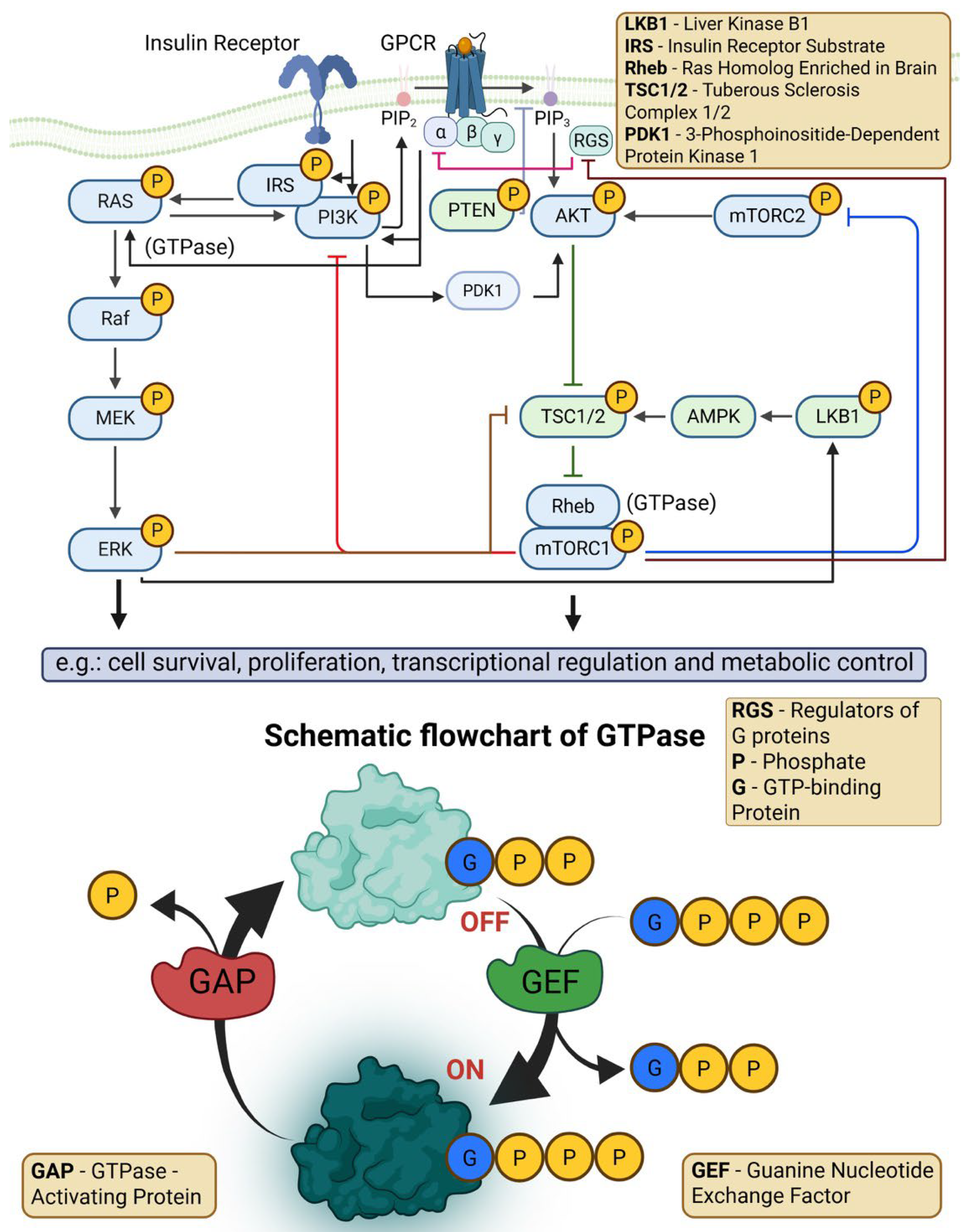

Driven by these data, we suggest that signaling transduction pathways such as mTORC and the MAPKs regulating the eucaryotic eIF family may be involved in transfection processes [

182,

183]. Furthermore, the study investigated interactions of different ionizable LNP lipids (MC3, Lung SORT, SM-102, and ALC-0315) with cell surface proteins to identify possible competitors for LNP attachment forming a proteinaceous corona. In this context, vitronectin and ficolin-1 were found to particularly facilitate attachment of LNPs to heart tissue cells. Interaction with vitronectin may promote cell proliferation and enhance tumor growth and metastatic potential [

184], while ficolin-1, through binding to transforming growth factor (TGF-β1), may modulate the lectin pathway and the complement component of innate immunity [

185].

4.6. Dysregulation of MAPK/ERK, JAK-STAT, and Other Signaling Pathways

Knabl et al. conducted an

in vivo transcriptomic study to assess the systemic effects of modRNA packaged in LNPs in both comorbid elderly and healthy younger vaccinated individuals [

186]. In this study, four patients had received the first dose of BNT162b2 approximately 11 days before the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, while five patients were unvaccinated. All patients were treated with dexamethasone. Immune transcriptomes (MSigDB-GSEA) were analyzed at days 7–13, 20–32, and 42–60 after symptom onset (Supplementary S3). In the raw data, thousands of genes in the transcriptomics were statistically significantly changed (up- or downregulated) after the BNT162b2-application.

As reported by the authors, COVID-19 symptoms (Beta variant) developed in all patients including those who became infected shortly after the administration of the first BNT162b2 dose [

186]. MSigDB-GSEA analysis of the four vaccinated patients revealed acute gene expression changes across thousands of genes. One of the elderly comorbid patients died before the end of the study. Signaling pathways that were affected included JAK-STAT3, Interleukin-6 (Il-6) and Kirsten Rat Sarcoma (KRAS) (part of the ERK-MAPK pathway), among others, with many changes reaching statistical significance.

The canonical ERK-MAPK signaling pathway involves several key components: Rat Sarcoma (Ras), Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma (Raf), Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MEK), and Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK), and it has extensive crosstalk with the mechanistic target of rapamycin complexes (mTORC) 1/2 downstream [

187,

188].

Notably, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) via NF-κB signaling was upregulated in both study groups (see next paragraphs), similar to the activation observed by Zelkoski et al. [

9] and Ndeupen et al. [

137]. While it remains unclear whether this reflects canonical (RELA/p65-IκB-dependent) or non-canonical (NIK-RELB-mediated) NF-κB activation [

189], such induction is consistent with stress-responsive transcriptional reprogramming. In this context, KRAS activation is of particular concern, as RAS-driven signaling can trigger both NF-κB pathways through the RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT cascades, thereby promoting cellular adaptation to inflammatory or genotoxic stress and, under chronic conditions, favoring malignant transformation [

190,

191]. Concurrent upregulation of p53, as also reported by Knabl et al., indicates the presence of a counter-regulatory response to such proliferative or stress-related cues [

192].

Moreover, Knabl et al. detected significant mTORC1 signaling across doses 1 to 3, with ten overlapping genes reaching statistical significance, underscoring that both mTORC1 and p53 are co-activated under conditions of physiological and genotoxic stress. KRAS signaling can engage NF-κB through multiple downstream routes (including RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT branches) [

143], thereby promoting transcriptional programs that support cell survival and stress adaptation. Distinguishing canonical from non-canonical NF-κB activation in these samples requires targeted inspection of pathway components (e.g. RELA/p65 phosphorylation and IκB degradation for the canonical arm; NIK/RelB dynamics for the non-canonical arm) at the transcript and protein level [

143,

189]. Moreover, the four elderly patients showed profound upregulation of the JAK-STAT5 pathway with IL-2 and the JAK-STAT3 pathway with IL-6.

The authors later included eight healthy naive individuals receiving their first vaccine dose, analyzing transcriptional changes 7-10 days post-vaccination. In these naive individuals, selective upregulation of the transcription factor E2F8 and specific interferon-stimulated genes was observed, while E2F1 and CCNA1 remained largely unchanged. Similarly, only three canonical mTORC1 target genes (CDC25A, RRM2 and BUB1) were modulated, indicating that global mTORC1 activation was minimal but statistically significant at this early time-point. CDC25A, RRM2, and BUB1 mark the transitions G1/S (CDC25A), DNA synthesis (RRM2), and mitosis (BUB1) [

193]. However, growing evidence suggests that E2F1/2/4 expression correlates with immune cell infiltration and may modulate immune responses in proliferative or stressed cells [

194,

195,

196].

It is known that E2F1 is in tight crosstalk during cell cycle phases with the 7 other members of the E2F transcription factor family [

197,

198,

199]. Furthermore, it was shown that E2F1 plays a crucial role in immune cell differentiation and cloning [

200,

201]. These findings support the notion that modRNA-LNP exposure can induce selective, systemic transcriptomic changes even in the absence of active viral infection, with partial activation of cell cycle genes, interferon responses, and minimal mTORC1 signaling, consistent with a fragmented or dysregulated cell cycle program rather than a synchronized proliferative response [

202,

203]. Furthermore, the consistent P53 upregulation in both groups together with a decoupled E2F1 from E2F8 transcription factor transcriptome is indicating that a cell cycle dysfunctionality was observed in the immune cells which was depending on the mTORC1 signaling regulating CDC25A [

204,

205]. Another indication that the cell cycle is affected at the transcriptomic level is the coordinated enrichment of gene sets associated with mitosis, checkpoint control, and Rho-GTPase signaling (Supplementary Data S5). All analyses were made with KEGG and show that the signals were active.

In summary, the insights of Knabl et al. [

186] support the assumption that the inflammatory properties of LNPs observed in mice by Ndeupen et al. and the findings of Luo et al. [

33] are also present

in vivo following BNT162b2 transfection. As discussed in the previous section regarding TLR signaling and the counterintuitive effects of modRNA modifications, these effects may be additive and/or synergistic and/or antagonistic

in vivo. Moreover, as discussed in

Section 2, not every immune cell internalizes LNPs equally, as uptake efficiency is influenced by factors such as the protein corona. This heterogeneity highlights limitations in generalizing the transcriptomic effects observed in Knabl et al. [

186] and sets the stage for the subsequent discussion of more controlled experimental models.

4.7. Disrupted RAS Signaling

Hickey et al. conducted one of the first proteomic analyses examining molecular alterations following BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccination. Their data indicate that even one month after BNT162b2 administration, RAS-mediated signaling remained moderately downregulated [

206]. The authors also observed a downregulation of RAS variant signaling, while the chemical carcinogenesis pathway appeared activated. This pathway encompasses several receptor-driven cascades, including ERK, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and related signaling routes, which are normally involved in cellular adaptation processes and stress responses.

These findings warrant attention, as physiological RAS signal cascades act as finely tuned molecular switches that cycle between inactive and active states and back again over a defined temporal window, ranging from hours to a few days, depending on the cellular context [

207,

208,

209]. Through these transient activation patterns, RAS-dependent signaling governs essential cellular functions such as migration, proliferation, differentiation, survival, and metabolic regulation [

210,

211]. Sustained alterations in these pathways, therefore, may reflect a broader disturbance of regulatory homeostasis rather than a direct oncogenic transformation. Nonetheless, a paradigm shift is occurring in this field of research, suggesting that cell homeostasis is one of the most important factors for cancer progression, challenging the traditional mutation-centric picture [

212,

213].

4.8. Disruption of the ESCRT Circuit and Phosphatidylinositol Signaling

Another relevant observation reported in a proteomics study by Hickey et al. concerns a reduction in endocytic activity and a downregulation of the ESCRT circuit, both of which point toward an acute perturbation of the phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) cycle [

206]. This cycle is a central phospholipid regulatory pathway that coordinates membrane dynamics and endosomal trafficking [

214,

215,

216]. It has been shown that the modRNA-LNPs induce membrane perturbations, which are detected by the ESCRT machinery, and small disruptions are quickly sealed before disruption accelerates and larger perturbations trigger galectin 9 repair [

75,

87].

This observation is also consistent with the review by Hurley et al. [

217], which summarizes ESCRTs as central to cell membrane repair mechanisms and, beyond that, to the organelle transport system. Interestingly, ESCRTs appear to be cooperators and facilitators for ubiquitin-driven PtdIns [

218]. The ESCRT disruption demonstrated by Hickey et al. [

206] is also consistent with the downregulated PPARγ pathway reported by Ndeupen et al. [

137], as recent results suggest direct crosstalk between PPARγ and ESCRT [

219].

Our review of existing omics analysis reveals cell homeostasis affecting properties of LNPs that go beyond the traditional toxicological effects, particularly through their ionizable lipid components and, as we will discuss in

Section 5, DSPC and cholesterol as well. One limitation that should be considered is that there are no data available on the use of empty LNPs in humans alone. It is therefore unclear to what extent synergistic, additive, and antagonistic effects need to be considered. Simonsen and Schoenmaker et al. reported that approximately 30–50% of LNPs succeed in containing and delivering genetic material [

220,

221]. This is another important observation that strengthens our hypothesis. However, since these minimally loaded LNPs or eLNPs have been shown to exhibit greater fusogenicity, endosomal escape efficiency, and gene expression

in vivo, it is possible these “empty LNPs” could engage or overload the ESCRT machinery, affecting endolysosomal homeostasis and downstream signaling [

222].

However,

in vitro and

in vivo data demonstrate that lipid formulated constructs, such as liposomes and LNPs, disrupt cellular homeostasis by altering signal transduction pathways, receptor activation, and phosphorylation cascades [

9,

137,

223,

224,

225]. An autophagy deficiency might also appear, triggering apoptosis as one of the moderate downstream consequences, underscoring the broader toxic impact of LNPs. This finding is of considerable significance, as the omics data we have discussed here and the shifts in signaling pathways cannot be attributed solely to the presence of modRNA and/or spike proteins.

4.9. Perturbations Originate at the Plasma Membrane and Disturb PtdIns Signaling Cascades

The sequence of events needs to be considered: the LNPs are taken up first (time point 0), after which the release of modRNA into the cytosol occurs only with marked delay. In fact, with release rates estimated at well below 10–15%, as suggested by Müller et al. [

79], it appears far more likely that most of the modRNA remains inside the LNPs and is subsequently exocytosed again. Only after an additional delay does the fraction of modRNA that escapes become translated into spike protein. This can occur at a distant site from the injection, as we have pointed out in

Section 2.

However, our hypothesis that LNPs drive the immune system’s first response and have effects on more than only the immune system is furthermore supported by the study of Connors et al., [

123], who showed that empty LNPs induce activation and maturation of monocyte derived dendritic cells (MDDCs) and also upregulated CD40 expression, which led to recruitment of pro-TFH cytokines, key cytokines and chemokines. Furthermore, Qin et al. showed in mice that these effects have transgenerational shifted immunological consequences [

225].

Taken together, the above discussed findings underscore the fact that the earliest perturbations following LNP exposure likely originate at the plasma membrane, with the phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns/PI) cycle as a central regulatory hub. Even subtle disturbances at this level could have cascading effects on lipid raft organization, receptor localization, and downstream signal transduction pathways, leading to transcriptional alterations and, as Hickey et al. [

206] and Luo et al. [

33] have demonstrated, proteomic consequences.

Establishing precise mechanistic patterns

in vivo remains challenging, particularly in the absence of large, well-characterized cohorts stratified by age, vaccine type, dose number, batch, comorbidities, prior illnesses, and genetic predisposition. Early membrane-centered dysregulation, although not directly reflected in conventional blood values, may nonetheless set the stage for broader signaling alterations that we hypothesize as the initiating events for downstream cellular responses and potential dysregulations which will lead to paracrine and endocrine cascades [

226].

Therefore, in the next section, we will examine membrane organization, focusing on lipid rafts, as well as endosomal-lysosomal and autophagosomal aspects, which are suspected to act as primary drivers of the dysregulations, namely PI3K/AKT/mTOR, JAK-STAT and MAPK cascades, observed here. We will propose a plausible biological mechanism for how LNP uptake interferes with cellular homeostasis via L-DMD.

5. Breaching the Plasma Membrane: Important Roles for Phosphoinositides

In

Section 2, we outlined that LNP/modRNA complexes enter cells through both receptor-dependent and receptor-independent endocytosis-like processes, i.e., membrane breaching. It is further evident that LNPs can transfect a broad range of cell types, including B cells, T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells. This suggests that receptor shifts may already occur at this stage, involving altered conformations, translocations, or similar rearrangements.

The membrane-uptake mechanisms of LNPs are well documented. LNPs are internalized into the cell by endocytosis (receptor-mediated) and macro-pinocytosis (receptor-independent) This is best confirmed in the literature by earlier work such as that of Panariti et al. [

227], Voigt et al. [

228], and current reviews such as those of Wang et al. and Gerelli [

229,

230]. In this section, we focus on the mechanisms of membrane structuring and recycling and how these processes, when influenced by modRNA LNP technology, may lead to unpredictable consequences for membrane integrity and the recycling system.

We propose that membrane penetration and direct interactions of ionizable lipids with the phospholipid bilayer and membrane-bound receptors could contribute to reorganization events, including changes in lipid raft stability, where receptor proteins such as GPCRs are embedded. Ermilova and Swenson [

76] and Pilkington et al. [

78] provide relevant insights to support this perspective. Notably, Ermilova and Swenson’s free energy calculations of ionizable tertiary amine lipids indicated that both ALC-0315 and SM-102 can easily reside in the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer. This is consistent with observations, such as those by Wang et al. [

229] and Aliakbarinodehi et al. [

80]. Furthermore, Lavagna et al. [

231] suggest that the size-dependent aggregation of hydrophobic nanoparticles within lipid membranes can induce pronounced local curvature, folding, and even transient phase transitions of the bilayer. These membrane reorganizations arise purely from nanoparticle geometry and concentration and could thus represent an initial mechanical trigger that perturbs phosphoinositide organization and receptor localization, setting the stage for altered signaling and recycling dynamics.

5.1. Brief Overview of the Phosphatidylinositide Cycle

Given that membrane interactions are evident, the membrane structuring and recycling process must first be examined by investigating the phosphatidylinositide (PI)-cycle and potential effects the LNPs may have on it. The eukaryotic cell membrane consists of a phospholipid bilayer forming a stable barrier between aqueous compartments [

232]. Phospholipids are amphipathic molecules, with hydrophobic tails oriented inward and hydrophilic heads facing the aqueous environment. This arrangement allows selective transport of molecules. Membrane fluidity is influenced by fatty acid composition and cholesterol content. Embedded proteins, such as protein receptors (e.g., GPCRs), ion channels, and transmembrane-bound enzymes such as angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), mediate transport, signaling, and cell-cell recognition via extracellular signaling [

233]. The composition of fatty acids in phospholipids often follows the 18:0/18:1, or 18:1/18:1 rule, where the numbers indicate the degree of saturation. This affects membrane fluidity, as unsaturated chains (e.g., 18:1) reduce packing density and increase lipid mobility due to their kinks [

234]. Furthermore, the phospholipid bilayer should be regarded as a fluid mosaic [

235].

Lipid rafts are specialized microdomains in eukaryotic cell membranes, enriched in sphingolipids and cholesterol, with a specific composition of phospholipids, including phosphoinositides, that can influence membrane order and permeability [

236,

237]. Additionally, lipid rafts create local spatial and electrical potential differences compared to surrounding membrane regions, promoting receptor clustering and anchoring of signaling molecules. From a cellular signaling perspective, phosphoinositides act as first intracellular messengers, initiating downstream signaling cascades at the plasma membrane and on endosomal membranes after receptor internalization [

238]. Moreover, the triggered cascades are regulating this cycle in feedback loops [e.g., via RHO-GTPases (Ras homologous) and cell division cycle 42 (Cdc42 - part of the RHO family)] [

239,

240].

Fallahi-Sichani and Linderman showed that lipid rafts as membrane microdomains influence the localization of receptors like GPCRs [

241]. With rapid dimerization and monomerization, frequent partner changes lead to the formation of oligomeric receptor clusters. In addition, the effect of ligands varies broadly: “while some GPCRs are stimulated to dimerize by ligands, others are inhibited - indicating a differential, ligand-dependent receptor organization.” [

241]

5.2. The Role of Lipid Rafts in LNP Uptake into Cells

Building on the role of lipid rafts in receptor localization and oligomeric clustering described by Fallahi-Sichani and Linderman [

241], it has been suggested that these membrane microdomains also play a critical role in mediating interactions with exogenous particles. Wang et al. highlight that the ordered structure of lipid rafts can facilitate interactions between LNPs and the cellular membrane, thereby enhancing intracellular uptake through endocytosis [

242]. Furthermore, the specific organization of these domains may mimic natural raft structures, improving recognition and internalization processes regulated by lipid rafts. Since lipid rafts organize receptor clusters and serve as platforms for regulated signaling and endocytosis, phosphatidylinositides emerge as key intracellular messengers and spatial organizers within these microdomains. Their composition and dynamic turnover help coordinate receptor localization, membrane trafficking, and downstream signaling events, highlighting their central role in understanding how LNPs may influence cellular homeostasis.

5.3. Signaling Through Phosphorylation States of Phosphatidylinositols

Phospatidylinostol phosphates (PIPs) are derivatives of PIs, which orient themselves to the cytosolic side of the membrane through the phosphorylizable inositol head groups [

243]. PIs are amphiphilic and electrically neutral, and they are integral components of the cell membrane. They make up about 1%–5% (depending on membrane type) of the entire lipid mosaic [

244]. In contrast, their phosphorylated derivatives (PIPs) are electrically negatively charged and functionally active both in the cell membrane and in the cytosol, where they are localized membrane-bound in organelles such as early endosomes. Despite their low concentration in the phospholipid membrane mosaic, their role in phagocytosis, endocytosis, receptor-mediated endocytosis, and macro- and micropinocytosis is essential (see

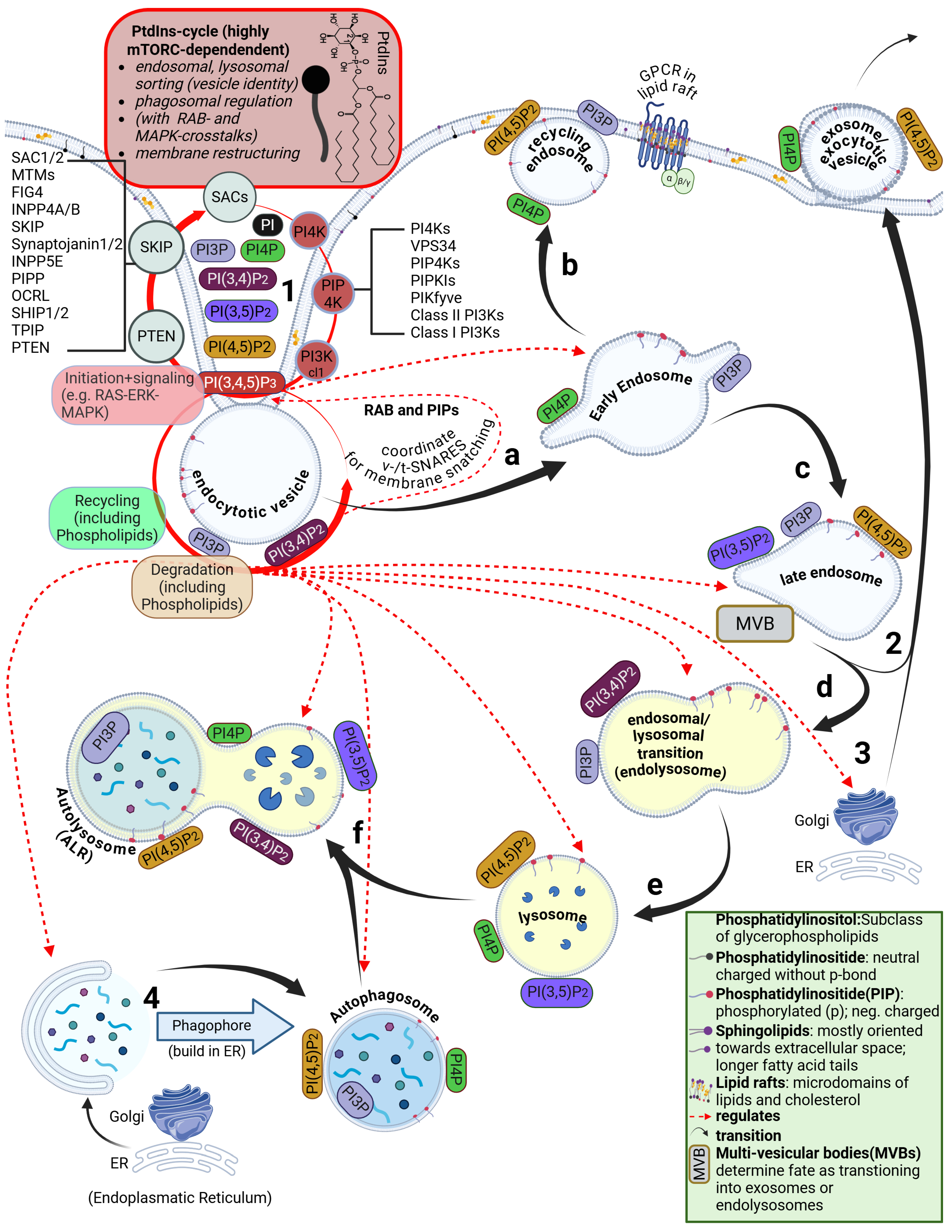

Figure 2).

Posor et al. describe the PI cycle (

Supplementary Table S1 and

Figure 2) as a tightly regulated network of dynamic transitions between phosphorylation states, such

as phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) and PI(3,4,5)P3 [

243]. This cycle regulates the processing and degradation of endosomes formed from the plasma membrane. During endosome formation, PIPs mark endosomes by binding to their membranes, a process initiated by membrane-membrane contact, acting as key modulators of downstream signaling pathways, including GTPases [

245]. The phosphorylation of PIPs is controlled by kinases such as phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and phosphatases such as the inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases (INPPs) [

246,

247] and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), as well as downstream signals, most notably, Akt. PIPs undergo a cyclic transition, for example from PI(3,4,5)P3 to PI(4,5)P2. These dynamics govern organelle maturation and transitions, such as the endosomal-lysosomal pathway. Moreover, PIPs play a critical role in balancing phospholipid recycling and degradation, essential for membrane restructuring and integrity (see

Figure 2). [

243,

246] Furthermore, the PtdIns cycle also controls RAB GTPases, integrating phosphoinositide signaling with the mechanical regulation of plasma membrane dynamics and organelle membrane trafficking [

248,

249].

5.4. Oxysterol-Binding Proteins (OSBs) and a Role for Cholesterol

Emerging evidence suggests that oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP)-related proteins (OSB proteins; also known as oxysterol homology (OSH) proteins) contribute to membrane organization and reorganization [

250,

251]. Since the PtdIns cycle is a key regulator of membrane dynamics, this points to additional layers of regulation that are not yet fully understood. It further raises the possibility of extensive crosstalk between PtdIns metabolism and OSH proteins in coordinating membrane reorganization. OSH proteins also bind to oxidized cholesterol. This raises the question of what role cholesterol in lipid nanoparticles could play in membrane disturbances, particularly since the particles induce an inflammatory response [

252].

Given that PIPs mark endosomal membranes and tightly regulate organelle maturation and trafficking, any disruption of their dynamic phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycles can compromise membrane integrity. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), upon endocytic uptake, introduce high local concentrations of cationic or ionizable lipids into the endosomal membrane. These lipids interact with the negatively charged PIPs and the surrounding phospholipid matrix, destabilizing the tightly regulated membrane environment described above. Consequently, this can lead to endosomal and lysosomal membrane holes or pores, facilitating the cytosolic release of encapsulated cargo such as modRNA, while bypassing the canonical degradation pathways that are normally orchestrated by the PI cycle [

160,

253].

In

Section 2, we also discussed that only 3% - maximum 15% of cargo-containing LNPs (depending on the formulation and cell type) actually reach the phase of endsomal/lysosomal escape [

24]. Furthermore, Paramasivam et al. showed that the efficiency of endosomal escape does not correlate with overall uptake, indicating that the fraction of LNPs reaching endosomes is largely independent of how efficiently they later escape into the cytosol [

83]. In other terms, that means that it is not known how many LNPs are taken up and how many stay in the endsomal/lysosomal/autophagosome transition.

Recent spatiotemporal analyses using sensitive LNP labeling platforms further support this notion, showing that continuous endocytosis and endolysosomal trafficking are required to maintain pools of releasable compartments, thereby mechanistically explaining why only a fraction of LNPs achieve cytosolic release while the remainder remains in lysosomes [

254]. This partial efficiency highlights the unresolved question of how the remaining LNPs, which do not induce endosomal rupture and are trafficked to lysosomes, are subsequently degraded or recycled within the cell, and whether their presence might disturb these important processes.

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), upon endocytic uptake, introduce high local concentrations of cationic or ionizable lipids into the endosomal membrane, a phenomenon that has been highlighted as a major determinant of both efficacy and toxicity of LNP formulations [

92]. Moreover, Jörgensen et al. suggest that even the biodegraded blocks of the protonated tertiary amines (ionizable lipids) like ALC-0315 and SM-102 remain bioactive. The authors note: “

However, they are neither synthesized from endogenous or natural structures nor are they degraded into typical biocompatible building blocks” [

92].

5.5. How Does 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC) Affect the PI Cycle?

In the context of the recycling processes and membrane organization, another aspect that has received little attention is the phospholipid, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC) [

255,

256], which is used as an auxiliary lipid in LNPs. DSPC (also known as 18:0/18:0) has two saturated stearic acid chains. While structurally similar to the phospholipids naturally found in cell membranes, DSPCs are more tightly packed, more rigid, and more thermally stable [

257] than the typical 18:0/18:1 and 18:1/18:1 phospholipids found in eukaryotic membranes [

234,

258]. It has a high gel-liquid transition temperature (Tm approx. 55°C), which confers it with unusual rigidity [

259]. It is a natural phospholipid, primarily found in human pulmonary surfactant [

260].

This raises the question of how DSPC affects the PI-cycle, as it is known that PCs are recycled into various phospholipids, including PI. Phospholipase D, which converts PCs into phosphatidic acid (PA), plays an essential role in this process [

261,

262,

263]. PA is converted into CDP-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) by CDP-DAG synthase, a key step in channeling PA into the biosynthesis of PI and other phospholipids [

264,

265]. CDP-DAG subsequently serves as the immediate precursor for phosphatidylinositols, synthesized by PI synthase at the endoplasmic reticulum, forming the core PI scaffold [

265,

266].

To the best of our knowledge, it remains uncharacterized how DSPC is degraded and whether it can interfere with membrane physiology beyond the process of transfection through recycling. After 24 hours, most DSPC primarily accumulates in the liver, spleen, heart, kidney, and lung, indicating that these organs' plasma membranes take up the lipid [

267]. This confirms DSPC's tissue delivery and retention. However, it is known that liposomes composed of phospholipids such as DSPC can strikingly alter membrane structure, as previously discussed in the review by Lonez et al. [

223]. The exact cellular mechanism

in vivo remains poorly characterized. Studies indicate that DSPC-containing liposomes can undergo hydrolytic and oxidative degradation, producing phospholipid-derived products that may alter membrane structure and stability in unpredictable ways [

268,

269].

Although not yet demonstrated

in vivo, it is conceivable that lipid nanoparticles may interfere with autophagic lysosome reformation (ALR) [

270,

271], a process essential for sustaining lysosomal homeostasis and autophagic flux [

272,

273]. Since ALR depends on phosphoinositide transitions [

274] and clathrin-mediated membrane remodeling [

275], the insertion of ionizable lipids into these organelles could compromise the delicate balance of lysosomal recycling. Such perturbations may not only disturb autophagic flux but could also contribute to organ-specific toxicities observed with LNPs [

107].

5.6. A Role for Lipid Impurities

As we suggested in

Section 2, LNPs act as bioactive particles with unpredictable biodistribution and transfection pathways. It remains unclear under which membrane conditions their proposed mechanisms of action will occur. Furthermore, it is not known how lipid impurities may influence the processes of endosomal-lysosomal transition, autophagosome formation and the subsequent autophagosome-lysosome fusion leading to autolysosome formation.

One of the most likely occurring lipid impurities are covalent lipid adducts. Covalent RNA-lipid adducts, a class of degradation products first identified by Packer et al. [

94] are formed during manufacturing and storage.

In vitro studies have demonstrated that oxidative and hydrolytic transformations of tertiary amine-containing lipids (e.g., SM-102, ALC-0315, DLin-MC3-DMA) can generate electrophilic fatty aldehyde species and secondary amines. These aldehydes are reactive towards the nucleobases to form stable covalent adducts, rendering the modRNA untranslatable [

100]. Adducts are chemically stable and can persist unless removed or prevented. However, if adducted modRNA, present in the vaccine, is taken up by the cell, it may be perceived as abnormal or viral-like by cellular sensors [

97]. RNA-adducts may trigger inflammatory signals or interferon responses, contributing to systemic immune dysregulation, ribosomal stalling, and collision with trailing ribosomes, as well as inflammatory responses [

15], especially in vulnerable individuals [

276,

277]. Research on secondary amines and reactive aldehydes (e.g., 4-HNE, a product of lipid peroxidation) suggests that they can be cytotoxic. They may affect protein folding or function, leading to the formation of neoantigens that can provoke undesired immune responses [

98], and they may contribute to oxidative stress and lysosomal dysfunction [

99]. However, direct

in vivo evidence of new adduct formation after LNP uptake has not been confirmed. It remains unclear how such covalent lipid adducts affect organelle function and trafficking (e.g., the transition from endosome to lysosome), and consequently, the PI cycle.

5.7. Small Perturbations Can Lead to Major Shifts in PIP Signaling

Recent work by Fung et al. on the nonlinear dynamics of phosphoinositide metabolism demonstrates that PIP interconversion is governed by both feedback and feedforward circuits, excitable and oscillatory regimes, and kinetic thresholds, such that small perturbations in membrane composition, enzyme activity, or lipid transport can produce disproportionately large and sometimes paradoxical shifts in PIP balance [

278]. This nonlinearity implies that local perturbations introduced by LNPs (ionizable lipids, DSPC, pH changes) can push the system across dynamical, non-linear thresholds, radically altering endosomal identity, trafficking and release outcomes [

279]. Simple formulation ‘optimization’ may therefore be insufficient to guarantee predictable delivery across all cell types and physiological states.