Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

07 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Background

Methods

Protocol and Reporting

Research Questions

- Characterise the types of violence committed against women and girls in African countries.

- Conduct a thematic and contextual synthesis of determinants and outcomes of such violence.

- Provide a trend analysis across regions and populations over time.

Eligibility Criteria

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Study Selection

Data Extraction

Risk of Bias Assessment

Data Synthesis

Results

Study Characteristics

Thematic Analysis

Contextual Analysis

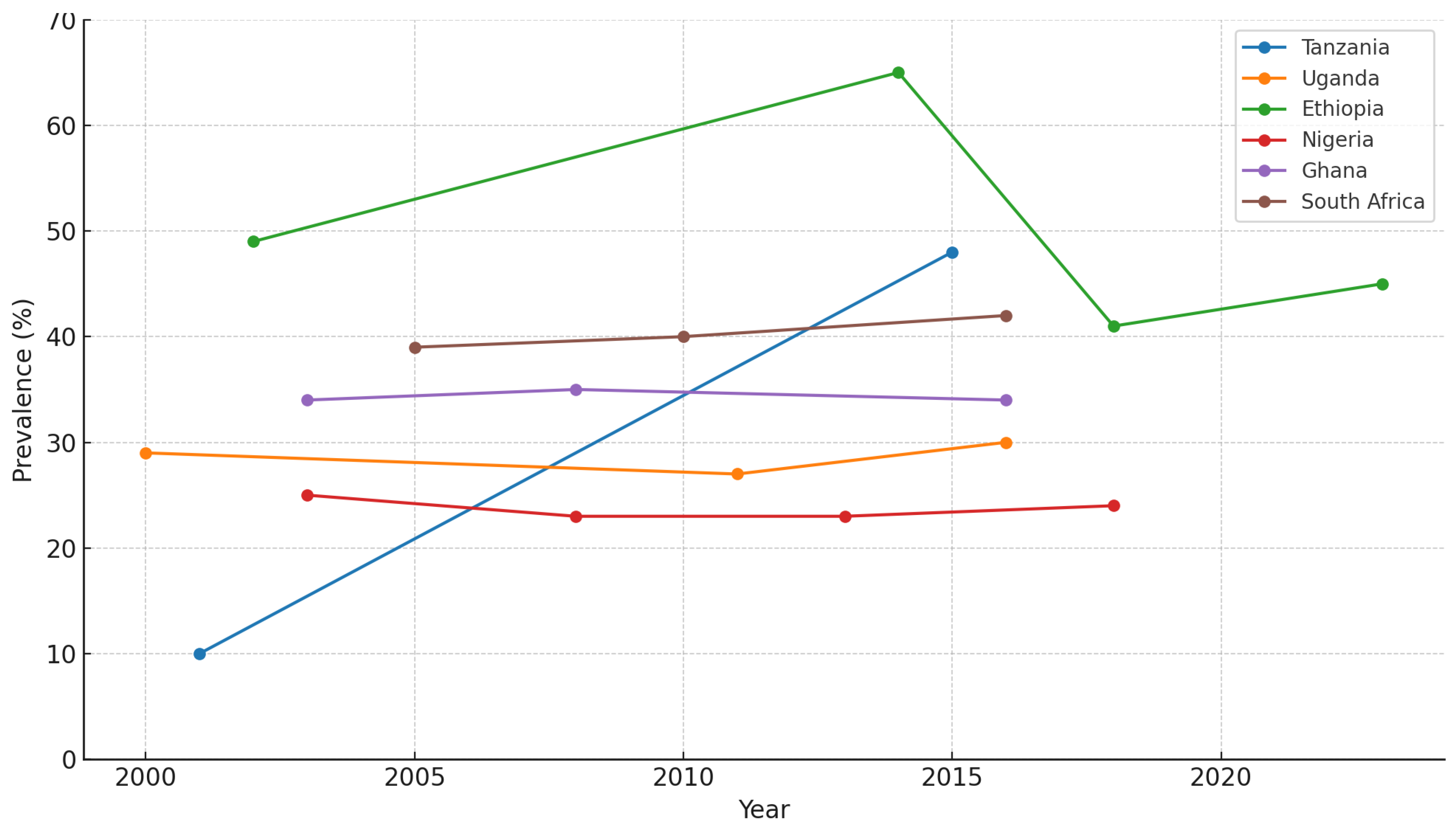

Trend Analysis

Intersectional Analysis

Discussion

Strengths and limitations

Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of interest

Availability of data and material

Code availability

Author contributions

Ethics approval

Consent to participate

Consent for publication

Acknowledgements

References

- Pallitto CG-MaC. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. 2013.

- UNFPA. ANNUAL REPORT 2017. 2017.

- Policy on Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women and Girls (GEEWG) in Humanitarian Action.; 2024.

- Harvey S, Lees S, Mshana G, Pilger D, Hansen C, Kapiga S, Watts C. A cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact on intimate partner violence of a 10-session participatory gender training curriculum delivered to women taking part in a group-based microfinance loan scheme in Tanzania (MAISHA CRT01): study protocol. BMC Women’s Health. 2018;18(1). [CrossRef]

- Gregg S. Gonsalves EHK, A. David Paltiel. Reducing Sexual Violence by Increasing the Supply of Toilets in Khayelitsha, South Africa: A Mathematical Model. 2015.

- Wondimye Ashena BM, Gudina Egata,Yemane Berhane. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy in Eastern Ethiopia. International Journal of Women’s Health 2020.

- Gashaw BT, Magnus JH, Schei B. Intimate partner violence and late entry into antenatal care in Ethiopia. Women and Birth. 2019;32(6):e530-e7. [CrossRef]

- Yohannes K, Abebe L, Kisi T, Demeke W, Yimer S, Feyiso M, Ayano G. The prevalence and predictors of domestic violence among pregnant women in Southeast Oromia, Ethiopia. Reproductive Health. 2019;16(1). [CrossRef]

- Zelalem Nigussie Azene HYY, Fantahun Ayenew Mekonnen. Intimate partner violence and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care service in Debre Markos town health facilities, Northwest Ethiopia. PLOS one. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Eskedar Berhanie DG, Hagos Berihu, Azmera Gerezgiher and Genet Kidane. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a case-control study. BMC Reproductive Health. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kahsay Zenebe Gebreslasie SW, Gelawdiyos Gebre and Mihret-Ab Mehari. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and risk of still birth in hospitals of Tigray region Ethiopia. Italian Journal of Pediatrics - BMC. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lencha B, Ameya G, Baresa G, Minda Z, Ganfure G. Intimate partner violence and its associated factors among pregnant women in Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0214962. [CrossRef]

- Fekadu E, Yigzaw G, Gelaye KA, Ayele TA, Minwuye T, Geneta T, Teshome DF. Prevalence of domestic violence and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care service at University of Gondar Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health. 2018;18(1). [CrossRef]

- Abay Woday Tadesse ND, Abigiya Wondimagegnehu, Gebeyaw Biset, Setegn Mihret. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and preterm birth among mothers who gave birth in public hospitals, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: A case-control study. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2020.

- Mohammed BH, Johnston JM, Harwell JI, Yi H, Tsang KW-k, Haidar JA. Intimate partner violence and utilization of maternal health care services in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17(1). [CrossRef]

- López-Goñi JJ, Musa A, Chojenta C, Loxton D. High rate of partner violence during pregnancy in eastern Ethiopia: Findings from a facility-based study. Plos One. 2020;15(6). [CrossRef]

- Fiona G Kouyoumdjian LMC, Susan J Bondy, Patricia O’Campo, David Serwadda, Fred Nalugoda, Joseph Kagaayi, Godfrey Kigozi, Maria Wawer and Ronald Gray. Risk factors for intimate partner violence in women in the Rakai Community Cohort Study, Uganda, from 2000 to 2009. BMC Public Health. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mootz JJ, Muhanguzi FK, Panko P, Mangen PO, Wainberg ML, Pinsky I, Khoshnood K. Armed conflict, alcohol misuse, decision-making, and intimate partner violence among women in Northeastern Uganda: a population level study. Conflict and Health. 2018;12(1). [CrossRef]

- Gibbs A, Jewkes R, Willan S, Washington L. Associations between poverty, mental health and substance use, gender power, and intimate partner violence amongst young (18-30) women and men in urban informal settlements in South Africa: A cross-sectional study and structural equation model. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204956. [CrossRef]

- Michael C. Ezeanochie BNO, Adedapo B. Ande, Weyinmi E. Kubeyinje & Friday E. Okonofua. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence against HIV-seropositive pregnant women in a Nigerian population. A C TA Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Bedilu Abebe Abate BAWaTTD. Determinants of intimate partner violence during pregnancy among married women in Abay Chomen district, Western Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Women’s Health. 2016.

- Olufunmilayo I. Fawole ODBaOO. Experience of gender-based violence to students in public and private secondary schools in Ilorin, Nigeria. 2018.

- Leah Okenwa Emegwa SLL, Bjarne JanssonBjarne Jansson. Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence Amongst Women of Reproductive Age in Lagos, Nigeria: Prevalence and Predictors. J Fam. 2009.

- Deborah A Gust YP, Fred Otieno, Tameka Hayes,Tereza Omoro, Penelope A Phillips–Howard, Fred Odongo, George O Otieno. Factors associated with physical violence by a sexual partner among girls and women in rural Kenya. Journal of Global health. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Eunice Kimani JOaDA. Factors increasing vulnerability to sexual violence of adolescent girls in Limuru sub-county, Kenya. African journal of Midwifery and Women’s health. 2016.

- Mathewos Fute ZBM, Negash Wakgari and Gizachew Assefa Tessema. High prevalence of workplace violence among nurses working at public health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. BMC nursing. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Girmatsion Feseha AGmaMG. Intimate partner physical violence among women in Shimelba refugee camp, northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012.

- Gladys Matseke VJR, Karl Peltzer, and Deborah Jones. Intimate partner violence among HIV positive pregnant women in South Africa. J Psychol Afr 2017. [CrossRef]

- Wandera SO, Kwagala B, Ndugga P, Kabagenyi A. Partners’ controlling behaviors and intimate partner sexual violence among married women in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:214. [CrossRef]

- Lyons CE, Grosso A, Drame FM, Ketende S, Diouf D, Ba I, et al. Physical and Sexual Violence Affecting Female Sex Workers in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: Prevalence, and the Relationship with the Work Environment, HIV, and Access to Health Services. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2017;75(1):9-17. [CrossRef]

- Heidi Stöckl CWJKKM. Physical violence by a partner during pregnancy in Tanzania: prevalence and risk factors. Reproductive Health Matters. 2010.

- Mahenge B, Stockl H, Abubakari A, Mbwambo J, Jahn A. Physical, Sexual, Emotional and Economic Intimate Partner Violence and Controlling Behaviors during Pregnancy and Postpartum among Women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164376. [CrossRef]

- Selin A, DeLong SM, Julien A, MacPhail C, Twine R, Hughes JP, et al. Prevalence and Associations, by Age Group, of IPV Among AGYW in Rural South Africa. Sage Open. 2019;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Malavika Prabhu BM, Jan Ostermann, Dafrosa Itemba, Bernard Njaub,Nathan Thielman. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among women attending HIV voluntary counseling and testing in northern Tanzania, 2005–2008. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011. [CrossRef]

- Delamou A, Samandari G, Camara BS, Traore P, Diallo FG, Millimono S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among family planning clients in Conakry, Guinea. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:814. [CrossRef]

- Graham SM, Gibbs A, Carpenter B, Crankshaw T, Hannass-Hancock J, Smit J, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with recent intimate partner violence and relationships between disability and depression in post-partum women in one clinic in eThekwini Municipality, South Africa. Plos One. 2017;12(7). [CrossRef]

- M. Malan MFSaKS. The prevalence and predictors of intimate partner violence among pregnant women attending a midwife and obstetrics unit in the Western Cape. Global mental health. 2018.

- Fawole Olufunmilayo I DAT. Prevalence and correlates of violence against female sex workers in Abuja, Nigeria. African Health sciences. 2014.

- Ogum Alangea D, Addo-Lartey AA, Sikweyiya Y, Chirwa ED, Coker-Appiah D, Jewkes R, Adanu RMK. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence among women in four districts of the central region of Ghana: Baseline findings from a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200874. [CrossRef]

- Reese BM, Chen MS, Nekkanti M, Mulawa MI. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Women’s Past-Year Physical IPV Perpetration and Victimization in Tanzania. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017;36(3-4):1141-67. [CrossRef]

- Edwin Were KC, Sinead Delany-Moretlwe, Edith Nakku-Joloba, Nelly R.Mugo,James Kiarie, Elizabeth A. Bukusi, Connie Celum, Jared M. Baeten. A Prospective Study of Frequency and Correlates of Intimate Partner Violence among African Heterosexual HIV Serodiscordant Couples. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Kathryn L. Falb JA, Mazeda Hossain, Monika Topolska, Denise Kpebo,and Jhumka Gupta. Recent abuse from in-laws and associations with adverse experiences during the crisis among rural Ivorian women: Extended families as part of the ecological model. Glob Public Health. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Matthew J Breiding AR, Jama Gulaid, Curtis Blanton, James A Mercy, Linda L Dahlberg, Nonhlanhla Dlaminid & Sapna Bamrahe. Risk factors associated with sexual violence towards girls in Swaziland. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Negussie Deyessa YB, Mary Ellsberg,Maria Emmelin, Gunnar Kullgren and Ulf Hogberg. Violence against women in relation to literacy and area of residence in Ethiopia. BGlobal Health Action. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Ebrima J. Sisawo SYYAOaS-LH. Workplace violence against nurses in the Gambia: mixed methods design. BMC Health Services Research. 2017.

- Laura K. MurrayI JK, Nancy Glass, Stephanie Skavenski van WykI, Flor Melendez, Ravi Paul, Carla Kmett Danielson, Sarah M. MurrayI,John Mayeya, Francis Simenda, Paul Bolton. Effectiveness of the Common Elements Treatment Approach (CETA) in reducing intimate partner violence and hazardous alcohol use in Zambia (VATU): A randomized controlled trial. PLOS One - Medicine. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zoé Mistrale Hendrickson AML, Noya Galai, Jessie K Mbwambo,Samuel Likindikoki,6 Deanna L Kerrigan. Work-related mobility and experiences of gender-based violence among female sex workers in Iringa, Tanzania: a cross-sectional analysis of baseline data from Project Shikamana. BMJ Open. 2018.

- Constance J Newman DHdV, Jeanne d’Arc Kanakuze and Gerard Ngendahimana. Workplace violence and gender discrimination in Rwanda’s health workforce: Increasing safety and gender equality. Human Resources for Health 2011. [CrossRef]

- Amsal Seraw Alemie HYY, Ejigu Gebeye Zeleke and Birye Dessalegn Mekonnen. Intimate partner violence and associated factors among HIV positive women attending antiretroviral therapy clinics in Gondar city, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw EAaY. Disparities in Intimate Partner Violence among Currently Married Women from Food Secure and Insecure Urban Households in South Ethiopia: A Community Based Comparative Cross-Sectional Study. BioMed Research International. 2018.

- Tsai AC, Tomlinson M, Comulada WS, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Intimate Partner Violence and Depression Symptom Severity among South African Women during Pregnancy and Postpartum: Population-Based Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(1):e1001943. [CrossRef]

- Jiepin Cao JAG, Mohammed Ali, Margaret Lillie Elena McEwan, John Koku Awoonor-Williams , John Hembling, Safiyatu Abubakr-Bibilazu4, Haliq Adam ,and Joy Noel Baumgartner. The impact of a maternal mental health intervention on intimate partner violence in Northern Ghana and the mediating roles of social support and couple communication: secondary analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mwumvaneza Mutagoma LN, Dieudonne ’ Sebuhoro, David J Riedel and Joseph Ntaganira. Sexual and physical violence and associated factors among female sex workers in Rwanda: a cross-sectional survey. International journal of STD&AIDS. 2018.

- Peter Memiah TAM, Kourtney Prevot, Courtney K. Cook, Michelle M. Mwangi, E. Wairimu Mwangi, Kevin Owuor, and Sibhatu Biadgilign. The Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence, Associated Risk Factors, and Other Moderating Effects: Findings From the Kenya National Health Demographic Survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Rachel Jewkes YS, Mzikazi Nduna, Nwabisa Jama Shai & Kristin Dunkle. Motivations for , and perceptions and experiences of participating in, a cluster randomised controlled trial of a HIV-behavioural intervention in rural South Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Hanan M. Ghoneim OTT, Zakia M. Ibrahim and Amal A. Ahmed. Violence and sexual dysfunction among infertile Egyptian women. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zubairu Iliyasu HSG, Sanusi Abubakar, Maryam S. Auwala, Chisom Odoh,Hamisu M. Salihu, Muktar H. Aliyu. Phenotypes of intimate partner violence among women experiencing infertility in Kano, Northwest Nigeria. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Allison P. Pack KLE, Peter Mwarogo & Nzioki Kingola. Intimate partner violence against female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Greene JCKaWAT. Alcohol use and intimate partner violence among women and their partners in sub-Saharan Africa. Global Mental Health 2017.

- Gebrezgi BH, Badi MB, Cherkose EA, Weldehaweria NB. Factors associated with intimate partner physical violence among women attending antenatal care in Shire Endaselassie town, Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study, July 2015. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):76. [CrossRef]

- S Mashaphu GEW, E Gomo,and A Tomita. Intimate partner violence among HIV-serodiscordant couples in Durban, South Africa. S Afr Med J 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lalem Menber Belay NM. Intimate partner violence against pregnant women in East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia. 2019.

- Naeemah Abrahams RJ, Carl Lombard, Shanaaz Mathews, Jacquelyn Campbell & Banwari Meel. Impact of telephonic psycho-social support on adherence to post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after rape. AIDS Care. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Vyas S. Violence Against Women in Tanzania and its Association With Health-Care Utilisation and Out-of-Pocket Payments: An Analysis of the 2015 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey. East African Health Research Journal 2019.

- Kristin Dunkle ES, Sangeeta Chatterji, Lori Heise. Effective prevention of intimate partner violence through couples training: a randomised controlled trial of Indashyikirwa in Rwanda. BMJ Global Health. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Katherine G. MerrillI JCC, Michele R. Decker, John McGready,Virginia M. Burke, Jonathan K. Mwansa, Sam Miti, Christiana Frimpong, Caitlin E. Kennedy, Julie A. Denison. Prevalence of physical and sexual violence and psychological abuse among adolescents and young adults living with HIV in Zambia. PLOS ONE. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bright Opoku Ahinkorah KSDaA-AS. Women decision-making capacity and intimate partner violence among women in sub-Saharan Africa. Archives of Public Health. 2018.

- Ameh N. KTS, Onuh S.O., Okohue J.E., Umeora D.U.J., Anozie O.B. Burden of domestic violence among infertile women attending fertility clinics in Nigeria. Nigerian journal of medicine. 2007.

- Nambusi Kyegombea, TA, KMDa, LMb, , b JN, et al. What is the potential for interventions designed to prevent violence against women to reduce children’s exposure to violence? Findings from the SASA! study, Kampala, Uganda. 2015.

- Mhairi A. Gibson EG, Beatriz Cobo, María M. Rueda, and Isabel M. Scott. Measuring Hidden Support for Physical Intimate Partner Violence: A List Randomization Experiment in South-Central Ethiopia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Michele R. Decker SP, Adesola Olumide,Rajib Acharya, Oladosu Ojengbede, Laura Covarrubias, Ersheng Gao, Yan Cheng, Sinead Delany-Moretlwe and Heena Brahmbhatt. Prevalence and Health Impact of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-partner Sexual Violence Among Female Adolescents Aged15-19 Years in Vulnerable Urban Environments: A Multi Country Study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Cockcroft A, Marokoane N, Kgakole L, Tswetla N, Andersson N. Access of choice-disabled young women in Botswana to government structural support programmes: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup2):24-7. [CrossRef]

- Nakku-Joloba E, Kiguli J, Kayemba CN, Twimukye A, Mbazira JK, Parkes-Ratanshi R, et al. Perspectives on male partner notification and treatment for syphilis among antenatal women and their partners in Kampala and Wakiso districts, Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):124. [CrossRef]

- Nicola J Christofides AMH, Angelica Pino, Dumisani Rebombo,Ruari Santiago McBride, Althea Anderson, Dean Peacock. A cluster randomised controlled trial to determine the effect of community mobilisation and advocacy on men’s use of violence in periurban South Africa: study protocol. BMJ 2018. [CrossRef]

- Cheru Tulu EK, Dame Hirkisa, Zebiba Kedir, Lensa Abdurahim, Gemechu Ganfure, Jemal Muhammed, Kenbon Seyoum, Genet Fikadu, Ashenafi Mekonnen. Prevalence of Domestic Violence and Associated Factors among Antenatal Care Attending Women at Robe Hospital, Southeast Ethiopia. Clinics in Mother and Child Health 2019.

- Ashenafi W, Mengistie B, Egata G, Berhane Y. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy in Eastern Ethiopia. Int J Womens Health. 2020;12:339-58. [CrossRef]

- Ameh CA, Azene ZN, Yeshita HY, Mekonnen FA. Intimate partner violence and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care service in Debre Markos town health facilities, Northwest Ethiopia. Plos One. 2019;14(7). [CrossRef]

- Malan M, Spedding MF, Sorsdahl K. The prevalence and predictors of intimate partner violence among pregnant women attending a midwife and obstetrics unit in the Western Cape. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2018;5:e18.

- Yenealem DG, Woldegebriel MK, Olana AT, Mekonnen TH. Violence at work: determinants & prevalence among health care workers, northwest Ethiopia: an institutional based cross sectional study. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2019;31:8. [CrossRef]

- Stöckl H, Watts C, Kilonzo Mbwambo JK. Physical violence by a partner during pregnancy in Tanzania: prevalence and risk factors. Reproductive Health Matters. 2010;18(36):171-80. [CrossRef]

- Bloom BE, Wagman JA, Dunkle K, Fielding-Miller R. Exploring intimate partner violence among pregnant Eswatini women seeking antenatal care: How agency and food security impact violence-related outcomes. Glob Public Health. 2022;17(12):3465-75. [CrossRef]

- Fute M, Mengesha ZB, Wakgari N, Tessema GA. High prevalence of workplace violence among nurses working at public health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:9. [CrossRef]

| ID |

Author | Country | Study type |

Methodology |

Setting | Population | Age |

Sample size |

Findings/ Outcome |

Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gonsalve, Kaplan & Paltiel[6] |

South Africa | Mathematical model | Quantitative | Urban | N/A | N/A | N/A | Less sanitation facilities leads to major risk of sexual assault for women. | Census and statistics 2015,2016 |

| 2 | Ashenafi et al.[7] |

Eastern Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Rural& urban | Postpartum mothers | 15–44 years |

3015 | WHO multi-country study questionnaire |

|

| 3 | B.T. Gashaw et al. [8] | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Descriptive | Acute | Pregnant women | 15–45 years |

720 | Among multiparous women, any lifetime emotional or physical abuse was associated with late ANC |

The standardized and validated abuse assessment screening (AAS) tool |

| 4 | Yohannes et al. [9] |

Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute |

Pregnant women | 18–50 years |

299 | Physical violence was reported as the commonest type of violence Being illeterate, husband’s alcohol consumption, husband history of arrest, occupation of husband were significantly associated with domestic violence against pregnant women. |

A structured World Health Organization (WHO) multi-country study questionnaire |

| 5 | Azene, Yeshita & Mekonnen[10] | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | one referral hospital, three public health Centers, seven private clinics and 14 health posts, seven in rural and seven in urban areas |

Pregnant women | Not mentioned |

409 |

The prevalence of psychological, physical, and sexual violence was 29.1%, 21%, 19.8% respectively |

A structured questionnaire |

| 6 | Berhanie et al.[11] |

Ethiopia | Case -control | Quantitative | Acute | Pregnant women | 16-48 years | 954 | women who had been exposed to physical violence during pregnancy were five times more likely to experience low birth weight |

Pre-tested structured questionnaire |

| 7 | Gebreslasie et al.[12] |

Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Post- partum women | 19-35 years | 648 | statistically significant association between exposure to intimate partner violence during pregnancy and still birth. Pregnant women who were exposed to intimate partner violence during pregnancy |

A structured questionnaire |

| 8 | Lencha et al.[13] | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Pregnant women | Not mentioned | 612 | Physical violence (20.3%), sexual violence (36.3%), psychological/emotional violence (33.0), controlling behavior violence (30.4%) and economic violence (27.0) were the type of IPV encountered by participants. |

Pre-tested structured questionnaire |

| 9 | Fekadu et al.[14] |

Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Pregnant women | 18 to 49 years |

450 | Of the total pregnant women surveyed, 58.7% were victims of at least one form of domestic violence during pregnancy, |

Pre-tested structured questionnaire |

| 10 | Tadesse et al.[15] | Ethiopia | Case -control | Quantitative | Acute | Post- partum women | 138 cases and 276 controls |

Any IPV during pregnancy was significantly associated with PTB |

IPV questionnaire was adopted and modified from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (21) and the WHO 2005 Multi-Country study |

|

| 11 | Mohammed Et al.[16] |

Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Couples | 18 to 42 years |

210 male/female pairs | IPV is prevalent in Ethiopia where three out of four women reported having experienced one or more type of IPV. |

self-reported questionnaires |

| 12 | Musa et al.[17] | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Post- partum women | 15–49 years |

648 | The prevalence of intimate partner violence during the most recent pregnancy was found to be 39.81% |

interviewer-administered standardized questionnaire based on the World Health Organization Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women survey |

| 13 | Kouyoumdjian et al. [18] |

Uganda | Cohort study | Quantitative | Community | Female participants who had at least one sexual partner |

15 to 49 years |

15081 | Risk factors for IPV from childhood and early adulthood included sexual abuse in childhood or adolescence, earlier age at first sex, lower levels of education, and forced first sex. |

Revised Conflict Tactics Scales |

| 14 | Mootz et al. [19] | Uganda | Survey | Quantitative | Community | Women | 13 – 49 years |

605 | Most respondents (88.8%) experienced conflict-related violence. |

Survey questions |

| 15 | Gibbs et al.[20] | South Africa | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Urban | Men and women | 18-30 years | 680 women and 677 men |

Two third of women experienced physical or/and sexual IPV over past year. |

WHO violence against women scale |

| 16 | Owusu Adjah and Agbemafle[21] |

Ghana | Cross sectional (Secondary data analysis) | Quantitative | Community | Married women | 16-49 years | 2563 | Of the 1524 ever married women in this study, 33.6% had ever experienced domestic violence (some form of sexual, physical or emotional violence) and 87% were currently married. |

Household questionnaire |

| 17 | Abebe Abate et al.[22] |

Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Community | Married pregnant women |

15–49 years |

282 | The prevalence of intimate partner violence during recent pregnancy was 44.5%. |

WHO multi-country study questionnaire |

| 18 | Fawole et al.[23] | Nigeria | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Schools | Students | 10-21 years | 640 | At least one form of GBV was experienced by 89.1% of public and 84.8% private schools students |

Self-administered questionnaire. |

| 19 | Okenwa et al.[24] | Nigeria | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Women | 15-49 years | 934 | The 1 year prevalence of IPV was 29%, with significant proportions reporting psychological (23%), physical (9%) and sexual (8%) abuse. |

A structured questionnaire |

| 20 | Gust et al.[25] | Kenya | Cross sectional | Descriptive | Community | Women and girls | 8003 | Among 8003 participants, 11.6% reported physical violence by a sexual partner in the last 12 months |

A survey | |

| 21 | Kimani, Osero and Akunga[26] |

Kenya | Cross sectional | Mixed | Shool | Adolescent girls | 15–19 years. |

301 | Among the respondents, 33% were victims of sexual violence. |

self-administered questionnaires |

| 22 | Fute et al. [27] |

Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Community | Nurses | 25–52 years. |

660 | The prevalence of workplace violence was 29.9% |

A pre-tested and structured questionnaire |

| 23 | Feseha et al.[28] |

Ethiopia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Refugee camp | Refugee women | Not mentioned | 422 | The prevalence of physical violence in the last 12 months and lifetime were 107(25.5%) and 131(31.0%) respectively. |

A pre- tested interviewer guided structured questionnaire |

| 24 | Matseke et al.[29] |

South Africa | Randomised controlled trial | Descriptive | Community health centres | HIV-positive pregnant women |

18 years or older |

673 | Overall, 56.3% reported having experienced either psychological or physical IPV. |

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale 10 IPV was assessed using an adaptation of the Conflict Tactics Scale 18 HIV serostatus disclosure was assessed using an adapted version of the Disclosure Scale |

| 25 | Wandera et al.[30] |

Uganda | Cross-sectional | Survey | Community | Women who were in a union |

15-35+ years | 1307 | More than a quarter (27%) of women who were in a union in Uganda reported Initimate Partner Sexual Violence. |

Shortened and modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale |

| 26 | Lyons et al.[31] |

Abidjan | Cross-sectional | Quantitati | Communi | Women (assigned female sex at birth, and engaged in sex work as a primary source of income) | 18 years or older |

466 | Police refusal of protection was associated with physical and sexual violence |

interviewer-administered questionnaires |

| 27 | H Stöckl et al.[32] |

Tanzania | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Pregnant women | 15–49 years |

2503 | In total, 7% (n=88) of women in Dar es Salaam and 12% (n=147) of women in Mbeya reported having experienced violence during pregnancy. |

Pretested questionnaire |

| 28 | Mahenge et al.[33] | Tanzania | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Acute | 1-9 months postpatum women | 18-<36 years | 500 | 18.8% experienced some physical and/or sexual violence during pregnancy. |

Structured questionnaire |

| 29 | Selin et al.[34] |

Soth Africa | Randomised control trial | Quantitative | Rural | Adolescent girls and young women |

13-20 years | 2,533 |

Nearly one quarter (19.5%, 95% CI = [18.0, 21.2]) of AGYW experienced any IPV ever (physical or sexual) by a partner. |

Survey |

| 30 | M. C. Ezeanochie et al.[21] |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Acute | HIV-positive women |

21 - 43 years |

305 | Intimate partner violence was reported by 99 women, giving a prevalence of 32.5% . |

semi-structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. |

| 31 | Prabhu et al.[35] |

Tanzania | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | HIV voluntary counseling and testing center |

Women | 18-<40 years | 2436 | 432 (17.7%) reported IPV during their lifetime. |

Standardised 44 item questionnaire |

| 32 | Delamou et al. [36] |

Guinea | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Women | 15-49 years | 232 | 213 (92%) experienced IPV in one form or another at some point in their lifetime. |

IPV screening questionnaire |

| 33 | Gibbs et al. (2017)[37] | South Africa | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Postpartuem women | 18- <35 years | 275 | Prevalence of past 12-month sexual and/or physical IPV was 10.55% (n = 29). |

Structured questionnaires |

| 34 | Malan, Spedding and Sorsdahl[38] |

Western Cpe | Cross-sectional | Quantitive | Acute | Pregnant women |

18 years or older |

150 | Lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates for any IPV were 44%. |

Self-report measures Socio-demographics questionnaire WHO interpersonal violence questionnaire (IPVQ) Childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ) Alcohol use disorder identi cation test (AUDIT) Exposure to community violence questionnaire The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) |

| 35 | Olufunmilayo and Abosede[39] |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional | Analytical | Community | Female sex workers | 22 - 30 years |

283 | Sexual violence was the commonest type (41.9%) of violence experienced, followed by economic (37.7%), physical violence (35.7%) and psychological (31.9%). |

Semi-structured interviewer administered questionnaire and in-depth interview guide. |

| 36 | Alangea et al.[40] | Ghana | Randomised control trial | Descriptive exploratory | Community | Female | 18 to 49 years |

2000 | Half of women (50.9%) had experienced IPV in their lifetime; with ever experi- ence of sexual or physical IPV. |

A structured quantitative survey |

| 37 | Reese et al.[41] | Tanzania | Secondary data analysis | Quantitative | Community | Women | 15–49 years |

10139 | Approximately 1.5% (n =94) of women reported perpetrating isolated physical IPV |

Domestic violence module (questionnaire) |

| 38 | Were et al.[42] |

East and South Africa | Randomised control trial | Quantitative | Community | HIV serodiscordant couples |

N/A | 3408 |

IPV was reported at 2.7% of quarterly visits by HIV infected women. |

Interview |

| 39 | Falb et al.[43] |

West Africa | Secondary analysis | Quantitative | Rural | Women | N/A | 981 | Half of women reported lifetime physical or sexual IPV, and nearly 1 in 5 (18.6%) reported experiencing reproductive coercion. |

Survey |

| 40 | Breiding et al.[44] |

Swaziland |

Survey | Quantitative | Community | Female | 13 - 24 years |

1244 | The risk of experiencing sexual violence in childhood was significantly higher among respondents who reported having had no relationship with their biological mothers |

Survey questionnaire |

| 41 | Negussie Deyessa et al.[45] |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | rural and semi-urban |

Married women | 15–49 years |

1994 | Violence against women was more prevalent in rural communities. |

A standardised WHO questionnaire |

| 42 | Yenealem et al. |

Ethiop | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Health care workers |

25- years<35 | 553 | The prevalence of workplace violence was found to be 58.2% |

Structured self administered questionnaire |

| 43 | Sisawo et al. [46] |

Gambia | Cross-sectional | Mixed | Health administrative regions | Nurses | 30> years | 219 | A sizable majority of respondents (62.1%) reported exposure to violence in the 12 months prior to the survey; exposure to verbal abuse, physical violence, and sexual harassment was 59.8%, 17.2%, and 10% respectively. |

self-administered questionnaire |

| 44 | Murrayl et al.[47] | Zambia | Randomised control trial | Quantitative | Community | Couples | 18-66 + years | 123 | 112 clients reported active IPV |

N/A |

| 45 | Hendrickson ZM, et al.[48] |

Tanzania | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Community | Female sex workers | 18–55 years |

496 | Forty per cent of participants experienced recent physical or sexual violence, and 30% recently experienced severe physical or sexual violence. |

WHO’s Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test assessment |

| 46 | Newman et al. [49] |

Rwanda | Survey | Mixed | Community | Health workers | N/A | 297 | Thirty-nine percent of health workers had experienced some form of workplace violence in year prior to the study. |

health workers survey, facility manager and key informant interviews, patient focus groups and a facility risk assess- ment inventory (NB: This article draws only from a subset of health worker survey, key informant and facility man- ager interview, |

| 47 | Alemie et al. [50] |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Acute | HIV positive women | 19-<45 years | 626 | The overall prevalence of intimate partner violence against HIV positive women within the last 12 months was 64.2% |

A pretested structured interviewer-administered ques- tionnaire |

| 48 | Andarge and Shiferaw[51] |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Community | Married women | 15-49 years |

696 | LifetimeandcurrentIPVwere62.4%and 50%,respectively. |

A pretested and structured questionnaire |

| 49 | Tsai et al.[52] | South Africa | Cohort | Longitudenal | Community | Pregnant women | 1238 | IPV intensity had a statistically significant association with depression symptom severity |

Survey and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale |

|

| 50 | Cao et al.[53] |

Ghana | Randomised control trial | Quantitative | Community | Pregnant women | 16< years | 374 | The IPV prevalence was in high sample with 84.8% |

Ghana Demographic and Health Survey |

| 51 | Mutagoma et al.[54] |

Rwanda | Cross-sectional survey |

Quantitative | Community | Female sex workers | ≥15 years |

1978 | - Violence prevalence: 18.1% raped/forced sex during sex work, 35.6% experienced physical violence. |

Survey |

| 52 | Memiah et al.[55] |

Kenya | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Community | Women ever-partnered |

aged 15–49 years, | 3028 | - Higher odds of IPV associated with: age 40–49 yrs, urban residence, being employed, poor wealth index, early sexual debut (<18), low education, partners aged >50 yrs, and attitudes justifying wife-beating. |

Survey |

| 53 | R. Jewkes et al.[56] |

South Africa | Cluster randomized control trial | Quantitative | Community | Young women and men, normally resident, able to consent |

Intended: 16–23 years; Actual: 15–26 years |

Baseline: 1,415 women & 1,367 men; Follow-up: 1,085 women & 985 men |

- Main motivations: HIV testing, community benefit, smaller proportion for incentive (R20). |

structured questionnaire |

| 54 | Ghoneim et al.[57] |

Egypt | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Community | Women | 18–45 year |

303 | There was no signi cant difference between both groups in rates of exposure to violence (p-value 0.830). Primary infertility was a signi cant contributing factor in infertile women’s exposure to violence (p-value 0.001) |

Arabic validated NorVold Domestic Abuse Questionnaire |

| 55 | Z. Iliyasu et al.[58] |

Nigeria | Cross-sectional | Quatitative | Acute | Women | range 18–45 years |

373 |

- Prevalence of IPV in past year: 35.9% (95% CI 31.1–41.0). - Types: psychological (94%), sexual (82.8%), verbal (35.1%), physical (18.7%), economic (66.4%). - 25.4% experienced multiple forms of IPV. - Main perpetrators: spouses. |

CTS2 (Conflict Tactics Scale, revised). |

| 56 | A.P. Pack et al.[59] |

Kenya | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Community | Female sex workers |

≥18 years (majority >24 years: 60.6%) |

619 | - Prevalence of IPV (last 30 days): 78.7%. - Perpetrators: both clients & non-paying partners. |

survey |

| 57 | M.C.Greene et al.[60] | 14 Sub Saharan Africa | population-based cross- sectional survey (multilevel mixed-effects model) |

Quantitative | Community | Women | 15-49 years | 86024 | Prevalence of partner alcohol use and IPV ranged substantially across countries (3–62 and 11–60%, respect- ively). |

Demographic and Health Surveys |

| 58 | Gebrezgi et al.[61] |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | Mixed | Acute | Pregnant women | 15->34 | 422 | The prevalence of intimate partner physical violence in pregnancy was 20.6% ( |

Interview, pretested semi-structured locally adapted question- naire |

| 59 | Harvey et al. |

Tanzania | Cluster randomized control trial | Mixed | Community | Women | Not mentioned | 66 | Baseline interviews with participants indicate a prevalence of physical and/or sex- ual IPV during the past 12 months of 27% (95% confi- dence interval: 24% to 29%) |

Structured questionnaires, In depth interview guides |

| 60 | Mashaphu et al.[62] |

South Africa | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Community | serodiscordant couples |

aged ≥18 year |

30 | Exposure to IPV differed significantly between men (28.6%) and women (89.3%) (proportional |

Questionnaire |

| 61 | Belay and Menber[63] | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Married women | below the age 30 years old |

119 | Nearly half (46.4%) of the study participants were victims of at least one episodes of intimate partner violence in the recent pregnancy. Psychological violence 141 (44.2%) was the most common form of violence encountered followed by sexual violence 137 (42.9%). |

structured and pretested questionnaire |

| 62 | Abrahams et al.[64] | South Africa | RCT | Quantitative | Acute | Rape survivors |

10 - >22 years | 279 | The follow-up rate for the control arm was 92.7% and 91.9% for the intervention arm. |

Telephone call conversations |

| 63 | Vyas S.[65] |

Tanzania | Demographic and Health Survey |

Quantitative | Acute | Women | Mean age 29 years | 9,304 |

In total, 3,868 (43.2%) women reported that they had experi- enced physical or sexual violence by a partner or non-partner |

household questionnaire |

| 64 | Dunkle K, et al.[66] |

Rwanda | RCT | Quantitative | Community | Couples | <25->35 years | 828 women and 821 men |

at endline, 815 women (98.4%) and 763 men (92.9%) in the intervention and 802 women (96.4%) and 773 men (93.1%) were available for intention- to- treat analysis |

Adapted WHO violence against women instrument |

| 65 | Tchamo et al. |

Mozambique | Population based analysis | Quantitative | Community | Stakeholders and population | Not mentioned | 850,881 (Patients) |

The economic cost of VAW in Maputo, Matola, Beira, and Nampula, for a time horizon of 4 years (2005–2008), was US$1,473,828.7, with the health sector absorbing about 81% of the amount, justice 17%, and organizations working in the area of prevention with 2%. |

Interviews |

| 66 | Merrill et al.[67] | Zambia | RCT | Quantitative | Acute | HIV-positive adolescents and young adults |

15–24 years |

272 | prevalence of any violence victimization was 78.2%. Past-year preva- lence was 72.0% among males and 74.5% among females. |

survey |

| 67 | Ahinkorah et al. [68] |

Sub saharan Africa | Survey | Quantitative | Community | Women | 15–49 |

84,486 |

The odds of reporting ever experienced IPV was higher among women with decision-making capacity [AOR = 1. 35; CI = 1.35–1.48]. |

survey |

| 68 | Ameh et al.[69] | Nigeria | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Infertile women | 20-40+ years | 233 | 41% women experienced domestic violence. | Questionnaire |

| 69 | N. Kyegombe et al. [70] |

Uganda | RCT | Mixed | Community | women | 15–49 years |

419 men, 343 women | At follow-up, women in intervention communities were less likely to report past year experience of physical or sexual IPV than their control counterparts (aRR 0.68, 95% CI 0.16–1.39) |

Interview guide and quantitative questionnaire |

| 70 | Gibson et al.[71] |

Ethiopia | survey | Quantitative | Community | adults | 18-26+ years | 809 | The survey shows that only 18% of people openly say wife-beating is acceptable, but indirect questions suggest about 28% support it. | population-based demographic survey |

| 71 | Dibaba et al. |

Oromia | Cross sectional | Quantitative | Community | Female youth | 15 to 424years |

600 |

15.3% youth had experienced rape |

Adapted from other studies |

| 72 | Chirwa ED. Et al.[40] |

Ghana | RCT | Quantitative | Community | Adult men) |

(≥18 years | 2126 |

Lifetime IPV perpetration: 50% of men |

Interview guide |

| 73 | Tadesse et al. | Ethiopia | Case control study |

Quantitative | Acute | Mothers who gave birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation |

15- ≥35 years |

138 cases and 276 controls |

the prevalence of any IPV during pregnancy was 44.8% among cases and 25% among controls. |

IPV questionnaire was adopted and modified from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (21) and the WHO 2005 Multi-Country |

| 74 | M.R. Decker et al. [72] | Baltimore, Maryland, USA; New Delhi, India; Ibadan, Nigeria; Johannesburg, South Africa; and Shanghai, China |

survey | Quantitative | Community | Female Adolescents |

15 - 19 Years |

1,112 |

Among ever-partnered women, past-year IPV prevalence ranged from 10.2% in Shanghai to 36.6% in Johannesburg. Lifetime non-partner sexual violence ranged from 1.2% in Shanghai to 12.6% in Johannesburg. |

survey |

| 75 | Cockcroft et al.[73] |

Botswana | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Community | Young women | 15–29 years |

3,516 |

8% reported sexual violence |

Interview guide |

| 76 | Nakku-Joloba et al.[74] |

Uganda | N/A | Qualitative | Community | Male and female | 25–44 years |

54 | Fourteen of 22 (63%) female participants reported that they sometimes experienced domestic violence. Male participant’s knowledge of syphilis and their perception of their valued role as responsible fathers of an unborn baby facilitated return. |

Interview guide |

| 77 | Christofides NJ, et al.[75] | South Africa | Cluster RCT | Quantitative | Community | male | 18–40 years |

2600 | intervention expected to reduce men’s perpetration of physical/sexual VAW and improve gender-equitable norms |

audio computer-assisted self-interview questionnaire |

| 78 | Tulu C, et al.[76] |

Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | Quantitative | Acute | Pregnant women |

<20- >34 years |

385 | Overall prevalence of domestic violence during pregnancy: 24.5%. Factors significantly associated with domestic violence: partner alcohol consumption, unplanned pregnancy, and unwanted pregnancy |

Questionnaire |

| Theme | Sub-themes | Determinants | Exposures | Evidence synthesis |

| Forms of violence | Physical, sexual, psychological, economic, reproductive coercion, in-law abuse, workplace harassment | – | WHO/DHS IPV items; workplace violence tools; reproductive coercion scales | IPV 30–65%; pregnancy IPV 25–60%; CSA ~33%; FSWs 50%+; WPV 30–62% |

| Determinants | Alcohol/substance use; poverty/food insecurity; low education; childhood trauma; partner control; infertility stigma; disability; conflict | Individual, relationship, community, societal (WHO ecological model) | Logistic regression, mediation analysis, DHS pooled regressions | Consistent drivers in >80% of studies; partner alcohol strongest predictor |

| Health and social outcomes | Maternal morbidity, depression, anxiety, poor ANC use, adverse birth outcomes (preterm, LBW, stillbirth), HIV/STI risk, sexual dysfunction, workplace stress | – | EPDS, FSFI, birth outcomes, ANC attendance, STI/HIV status | IPV linked to depression (β=1.04–1.54), unintended pregnancy, poor adherence to PMTCT/PEP, low ANC uptake |

| Protective factors/interventions | Education, joint decision-making, social support, couple communication, gender-transformative curricula, psychotherapy, economic empowerment | Individual/relationship/community | SASA! cRCT; Indashyikirwa cRCT; CETA psychotherapy RCT; MAISHA trial | Demonstrated reductions in IPV and improved co-benefits (mental health, food security, parenting) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).