1. Introduction

In recent years, the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events around the world have posed unprecedented challenges to the traditional flood control system that relies on engineered defenses and floodplain planning, and the severe floods that occurred in 2005 in New Orleans, U.S.A., and Carlisle, U.K., have become an important case study to test the effectiveness of the existing flood control model(Spencer et al., 2017). Despite the differences in geography, governance systems, and social structures, the causes of the floods, the consequences of the damage, and the problems exposed by the flood prevention policies showed a high degree of commonality.

New Orleans is located in the Mississippi River Delta, where long-term urban sprawl, oil and gas development, and wetland loss have led to a significant erosion of natural buffering capacity(Eleonora Rohland, 2017). Carlisle, on the other hand, sits at the confluence of three rivers and has suffered extensive urban flooding due to continuous heavy rainfall and drainage system failures(Spencer et al., 2017). Both sites had considered floodplain setting and engineering facilities as a core flood control strategy, but the widespread failure of defenses under extreme weather impacts revealed systemic risks from ecological degradation, land hardening, insufficient financial investment, and fragmented governance.

In addition to the dilemmas at the natural and engineering levels, the social structure and policy implementation capacity have become key factors affecting the effectiveness of flood control. In New Orleans, inequalities among communities in policy participation, access to information, and resources for post-disaster reconstruction magnified the social consequences of the disaster(Rohland, 2018), while in Carlisle, lagging funding and limited local governance capacity stalled the flood control program for a long time(Convery & Bailey 2008). The above cases show that the applicability of flood control strategies is not only constrained by technical conditions but also by a combination of landscape characteristics, urban development patterns, governance capacity, and community participation.

Therefore, there is an urgent need to revisit the boundaries between floodplain policies and the applicability of urban flood control systems, and to explore how to build a flood control model that combines ecological resilience, social justice, and governance synergy in the context of climate change. The experiences of New Orleans and Carlisle provide typical samples for comparative studies and important insights for assessing the replicability and limitations of flood control strategies.

2. The Failure of Floodplains Flood Defence Strategies

Traditional flood defence is commonly divided into structural and non-structural measures. In the early stages of flood control policies, structural flood defence was dominated by engineering interventions such as levees, dams, and reservoirs(Dillenardt, Hudson, and Thieken 2022). These large-scale infrastructures were initially effective in mitigating small- and medium-scale flood risks. However, when the volume of floodwater exceeds the designed capacity of these structures, their protective functions can rapidly deteriorate, resulting in catastrophic failures and amplified flood impacts(Klijn et al., 2015).

A notable example is Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which exposed the vulnerability of structural flood defences in New Orleans, United States. The city’s extensive levee system, designed to protect against storm surges from the Gulf of Mexico, collapsed at multiple points when the surge exceeded the designed thresholds. As a result, approximately 80% of New Orleans was inundated, leading to the deaths of more than 1,800 people and economic losses exceeding US$100 billion(Brunkard, Namulanda, and Ratard 2008a). This event illustrated the limits of engineering flood control when urban expansion and infrastructure ageing intersect with extreme weather events.

A similar pattern can be observed in Carlisle, United Kingdom, where severe flooding in 2005 and again in 2015 overwhelmed existing flood defences. Despite the city’s flood walls and embankments along the River Eden, prolonged heavy rainfall and record-breaking discharge levels led to the failure of several flood barriers. The 2015 Storm Desmond flood caused over 2,000 properties to be inundated, major disruptions to transportation and electricity networks, and significant economic losses estimated at over £250 million(Marsh et al., 2016). The Carlisle case reveals that even advanced flood protection infrastructure can be compromised when rainfall intensity and duration exceed design parameters.

Both the New Orleans and Carlisle cases highlight a critical limitation of traditional engineering flood defences: their dependence on static design assumptions in a changing climate. As extreme weather events become more frequent and severe, scholars and policymakers increasingly emphasize non-structural and ecological flood management strategies—such as wetland restoration, adaptive land-use planning, and community-based risk governance—to enhance long-term resiliency (Marquardt, 2017).

A widespread structural flood defense measure is the creation of levees as the primary line of protection. In earlier decades, in response to the increasing frequency of riverine and coastal floods, levees and floodwalls were constructed around low-lying cities to reduce flood risk. This approach was particularly prominent in New Orleans, USA, where a complex system of levees and floodgates was designed to protect the city—approximately 80 percent of which lies below sea level—from the Mississippi River and storm surges from the Gulf of Mexico(Colten, 2018). Although this system provided temporary security, the catastrophic failure of several levees during Hurricane Katrina in August 2005 exposed the limitations of structural flood control. The surge overtopped and breached multiple sections of the flood defense network, resulting in the inundation of nearly 80% of the city and the loss of more than 1,800 lives(Seed et al., 2008). The disaster demonstrated that levee-based protection, while effective under design conditions, cannot withstand extreme or compound flooding events that exceed expected thresholds.

Similarly, Carlisle in the United Kingdom has long relied on engineered flood defences, such as embankments and floodwalls along the River Eden and its tributaries. These defenses were enhanced after major floods in 2005; however, in December 2015, Storm Desmond brought record-breaking rainfall that overwhelmed the city’s flood control system. The floodwalls and levees were overtopped, submerging large parts of the city and forcing thousands of residents to evacuate (Huq and Stubbings, 2015). The event revealed that even well-maintained defences could fail when extreme precipitation exceeds their design capacity, reinforcing the need for adaptive and nature-based flood management approaches.

In both cities, the reconsideration of floodplain functions has become a central issue. The creation of floodplains, once regarded as a benign alternative to direct containment by levees, still primarily serves to divert water away from urban areas rather than integrating floods into the ecological and social systems of the landscape. Contemporary approaches, such as Natural Flood Management (NFM), promote the rational use of land by restoring wetlands, reconnecting rivers to their floodplains, and enhancing the ecological and storage capacity of the catchment (Dadson et al.,. However, the challenges of land use planning, maintenance, and long-term management often lead to the failure of traditional floodplain schemes. As demonstrated in both New Orleans and Carlisle, insufficient integration of ecological design and community-based planning can result in repeated flood risk and increasing vulnerability over time.

3. Case Studies

3.1. Hurricane Katrina 2005 in New Orleans, USA

New Orleans, located in the state of Louisiana, United States, is situated in the low-lying Mississippi River Delta and is relatively low-lying, with approximately 80 percent of the city below sea level(Brunkard, Namulanda, and Ratard 2008b). This has resulted in the city historically facing the threat of flooding, especially during hurricane seasons. The context of flooding in New Orleans encompasses natural factors, urban planning, climate change, and human factors. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina was one of the worst flooding disasters in the history of New Orleans. On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina, one of the strongest tropical storms since 1928, struck New Orleans (Abass et al.,. Heavy rainfall and strong winds from the hurricane caused massive precipitation, and the volume of heavy rainfall and storm surges put the city's flood control system under tremendous stress.

The impact of human activities on nature is continuous. The ecosystems of some areas are damaged, especially when the flow of rivers is altered by human activities(Hupp, Pierce, and Noe 2009). When large amounts of heavy rainfall flood into a river area, it reduces the area's ability to withstand flooding. This was evident in the 2005 floods in New Orleans, U.S.A. Between the early 1900s and 2005, Louisiana lost an average of 88 square kilometres of wetlands per year. Between 1932 and 2000, approximately 4,900 square kilometres of wetlands were lost in coastal Louisiana (Elizabeth Fussell,. Much of the wetland loss during this period was due to the urban sprawl of New Orleans, and some of it was attributed to the overexploitation of oil and gas (Cutter et al. 2018). As a result of rapid economic growth, the region's cities have expanded rapidly, and the population has grown, leading to a concomitant loss of wetlands.

The reduction of wetlands has weakened the region's ability to cope with extreme weather. This led to the devastation of the region on 29 August 2005 when Hurricane Katrina struck. Storm surge and rainfall caused more than 50 levees and protective structures to fail(Brunkard et al. 2008b). Nearly 80 percent of the New Orleans metropolitan area was flooded, with water over three meters deep in some areas. In the end, more than 1,500 people died and nearly a million were evacuated. Direct economic losses exceeded $125 billion. As a result of this major natural disaster (Jonkman et al. 2009), the authorities spent $15 billion to reestablish the flood protection system, incorporating coastal protection to reduce the impact of storm surges.

3.2. Carlisle 2005 floods, UK

Carlisle is the county town and principal city of Cumbria, with a population of around 74,000, and is the economic and industrial centre of the North of England and the Scottish Borders (Roberts et al.,. Carlisle is served by three main rivers: the River Eden, the River Culdew, and the River Petrell. Carlisle is located at the confluence of these three rivers and is therefore highly susceptible to flooding. The city has a long history of flooding, with notable floods in 1771, 1822, 1856, 1925, 1968, and most recently in 2005. The flood level of the River Eden in 2015 was 0.6 metres higher than in 2005. The Carlisle area is highly susceptible to flooding due to its unique geographical location, which is characterized by three rivers. On 8 January 2005, two days of heavy rainfall in northwest England resulted in flash flooding, with large quantities of water and sediment pouring into the River Culdur, causing severe flooding (Roberts et al. 2009). Part of the river flows through an urban area, and the floodwaters poured into the area, causing extensive loss of life and property damage.

According to the UK government's Met Office, the source of the flooding that caused the 2005 mega-floods was mainly due to rising river flows. Sixty-seven percent of the flooding originated from rivers and watercourses, 25 percent was caused by surface water, and 8 percent was attributed to sewage and infrastructure failures resulting from flooding (Spencer et al., This is why floods often occur in cities that border rivers. The northern part of the Clare urban area experiences flooding every year during the summer months, primarily due to the rainy season, when the entire north of England is subjected to large amounts of rainfall. Of these, the worst affected is the entire northern part of the urban area. Apart from the topography of the area, the most critical aspect of flooding in Carlisle is that the city is situated in the northern part of the United Kingdom. The region has a maritime climate. The eastern and western parts of the region receive high levels of precipitation due to the maritime environment. The city's proximity to three major rivers makes flooding extremely severe (Spencer et al.,.

Since 2005, three severe floods have occurred in the locality, in 2005, 2009, and 2015, resulting in the destruction of 1,600, 15, and 2,128 houses, respectively (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,. The study found a positive correlation between the flow of the three local rivers and the extent of flood damage. Flooding has not only left a large number of residents homeless, but it has also had a profound impact on their mental health. Data showed that about 18 percent of residents worried about flooding during the rainy season, and 19 percent worried about flooding almost every day (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,. Additionally, nearly half of the residents had considered relocating from the area due to flooding. Flooding has had a significant negative impact on the local economy, the lives of residents, and their physical and mental health.

Following the 2005 floods, flood defences were established in relatively gentle areas of the Clare area. However, these floodplains do not appear to be functioning as they should. A study by the University of Salford into the flooding situation in the area concluded that ‘every few years, these areas flood. Flooding occurs in these areas every few years, and rather than diverting floodwaters away from urban areas, these floodplains exacerbate the flooding problems in the area. This is because large amounts of floodwaters wash over the floodplains, making them more prone to waterlogging. The initial plan was to introduce water slowly into the floodplain, allowing the soil and natural environment to capture large amounts of water, thereby reducing flood pressure downstream (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage 2016). However, the reality is that the flooding in the area has become significantly worse due to the massive influx of water, resulting in subsidence. When flooding is not occurring, the floodplains in the area are saturated. The situation in this area will undoubtedly worsen when the floods arrive (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,.

According to another survey conducted by the University of Salford, 90 percent of the UK's floodplains are not functioning correctly (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,. Through the survey, it was found that 65 percent of the floodplains have been converted into impermeable artificial surfaces, 9 percent of the land has been taken over by urban and suburban development, and 4 percent of the land has been taken over by open water. The remaining 6 percent and 0.5 percent have been taken over by woodlands and wetlands, respectively. This also means that many human activities have encroached on natural floodplains, thus posing a serious threat to the region's flood defenses (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,.

3.3. Case Summaries

In 2005, New Orleans in the United States and Carlisle in the United Kingdom suffered severe flooding, with many similarities in the causes and impacts of the floods, despite geographical differences. New Orleans is located in the Mississippi River delta, about 80 per cent of the city is below sea level, the low-lying terrain makes it face the threat of flooding for a long time, in August 2005, Hurricane Katrina brought heavy rainfall and storm surges caused more than 50 flood control facilities to fail, and 80 per cent of the city was inundated, with an economic loss of more than 125 billion US dollars, and about 1,500 people were killed(Elizabeth Fussell 2007). Long-term urban sprawl and oil development have caused a massive loss of wetlands, severely weakening the natural buffering capacity and exacerbating the destructive power of disasters. Similarly, Carlisle, UK, is situated at the confluence of three rivers, making it geographically vulnerable to flooding. Continuous heavy rainfall in early 2005 triggered widespread flooding of the rivers, resulting in extensive inundation of the city. Studies have shown that 67 percent of the water in the floods came from rivers, with the rest originating from surface runoff and drainage failures (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,. The flooding in Carlisle not only caused damage to homes and economic losses, but also long-term psychological stress and an increased willingness of residents to move. Although the government created floodplains and other protective measures after the disaster, most of the flood zones were ineffective due to land hardening and urban development.

Overall, the construction of construction zones associated with floodplains, which were adopted in both areas, did not work too well for these two areas. The two floods highlighted the fragile balance between natural geographic conditions and human activities. They exposed the inadequacy of the synergistic management of flood protection infrastructure and ecosystems in cities in the face of extreme weather events.

4. Policy Comparison

4.1. Key Influences on Floodplain Policies

The development and implementation of flood policies are primarily subject to two significant factors: natural conditions and the economic interests of multiple parties. The primary source of flooding problems in an area is often attributed to the specific climatic conditions of the region. Most areas at risk of flooding typically have several contributing factors, the first being that the terrain is relatively low-lying. The second is that the amount of precipitation over a given period exceeds the upper limit of what the area's water resources can handle. These objective natural factors are the primary source of policy development.

Second, the formulation and implementation of floodplain policies often involves multiple actors: first, the government, which seeks to strike a balance between economic construction, social stability, and ecological security; second, urban developers and construction forces, who usually tend to promote land use conversion to meet the interests of real estate, industrial, and commercial development; and third, the public and community residents, who are the direct bearers of flood disasters and the ultimate bearers of ecological risks. Risk bearers. In some countries, environmental organizations, academics, and citizen action groups also play a significant role, but their voice and participation vary substantially.

4.1. Failure of Floodplains Due to Environmental Changes

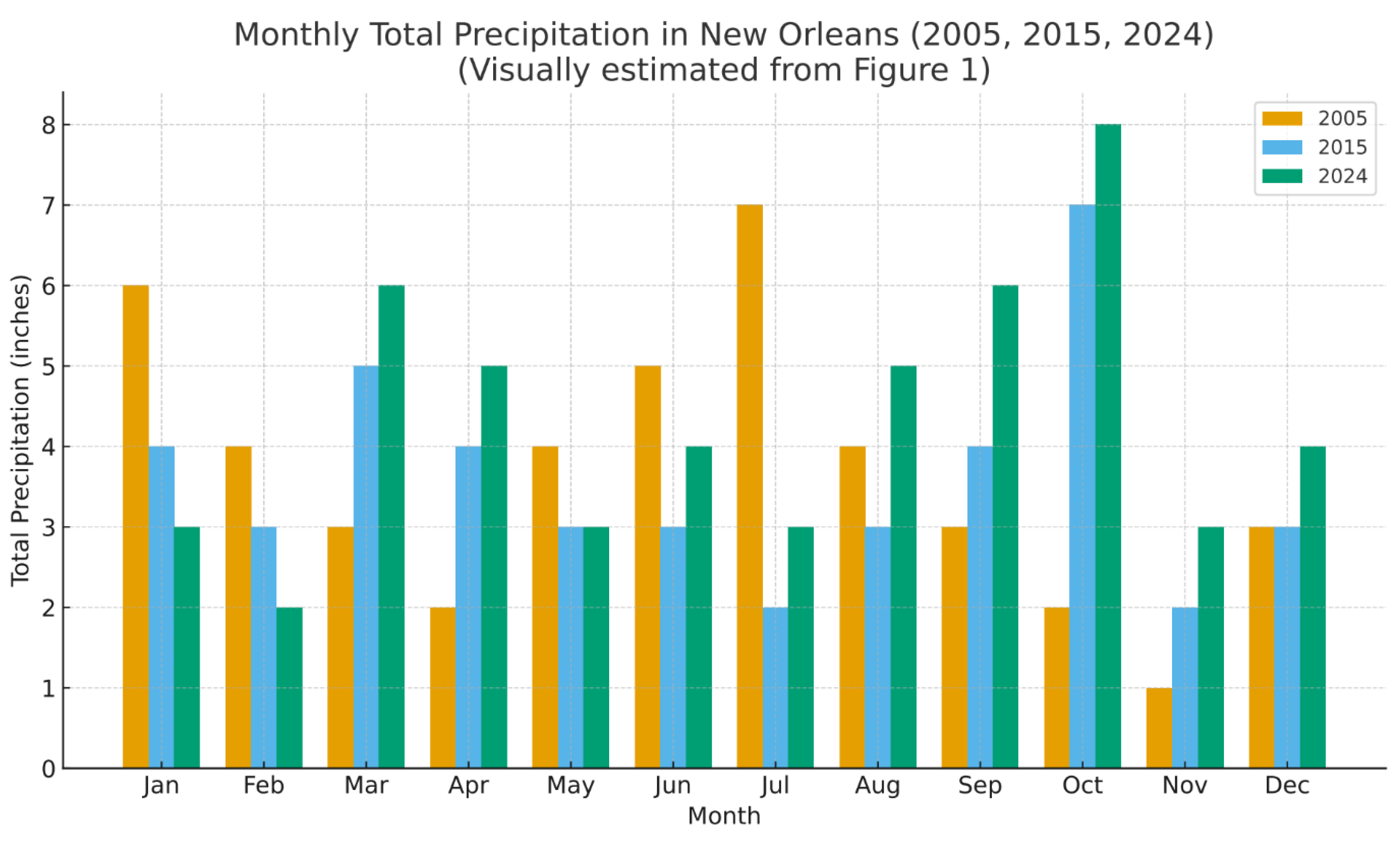

Over the last 20 years, New Orleans, USA, has experienced increasing floodplain failure due to extreme weather changes, primarily in the form of increased hurricane intensity, increased rainfall, and challenges to flood control infrastructure (Eleonora Rohland,. There has been a significant increase in precipitation in the New Orleans area in recent years. Climate studies have shown that nearly 90% of the United States has experienced an increase in hourly rainfall intensity since 1970 (Brasted 2025; Rohland 2018). As shown in

Figure 1, the picture illustrates the average daily precipitation changes in the New Orleans area for the years 2005, 2015, and 2024 over three years. From these three graphs of change, it is evident that there has been a significant increase in precipitation intensity, which also indicates an increased likelihood of extreme weather events. An April 2025 rainstorm, which dropped over six inches of rain in a matter of hours, resulted in multiple floods in the city. This shows a straightforward correlation to climate change.

New Orleans has experienced numerous extreme weather events over the past 20 years, highlighting the vulnerability of its flood defense system (Cass, Shao, and Smiley 2022). Despite the massive infrastructure rebuilding efforts following Katrina, existing systems will need to be continually upgraded and adapted as the challenges posed by climate change intensify. However, 10 years later, in 2015, the storm surge again affected the area, causing significant damage.

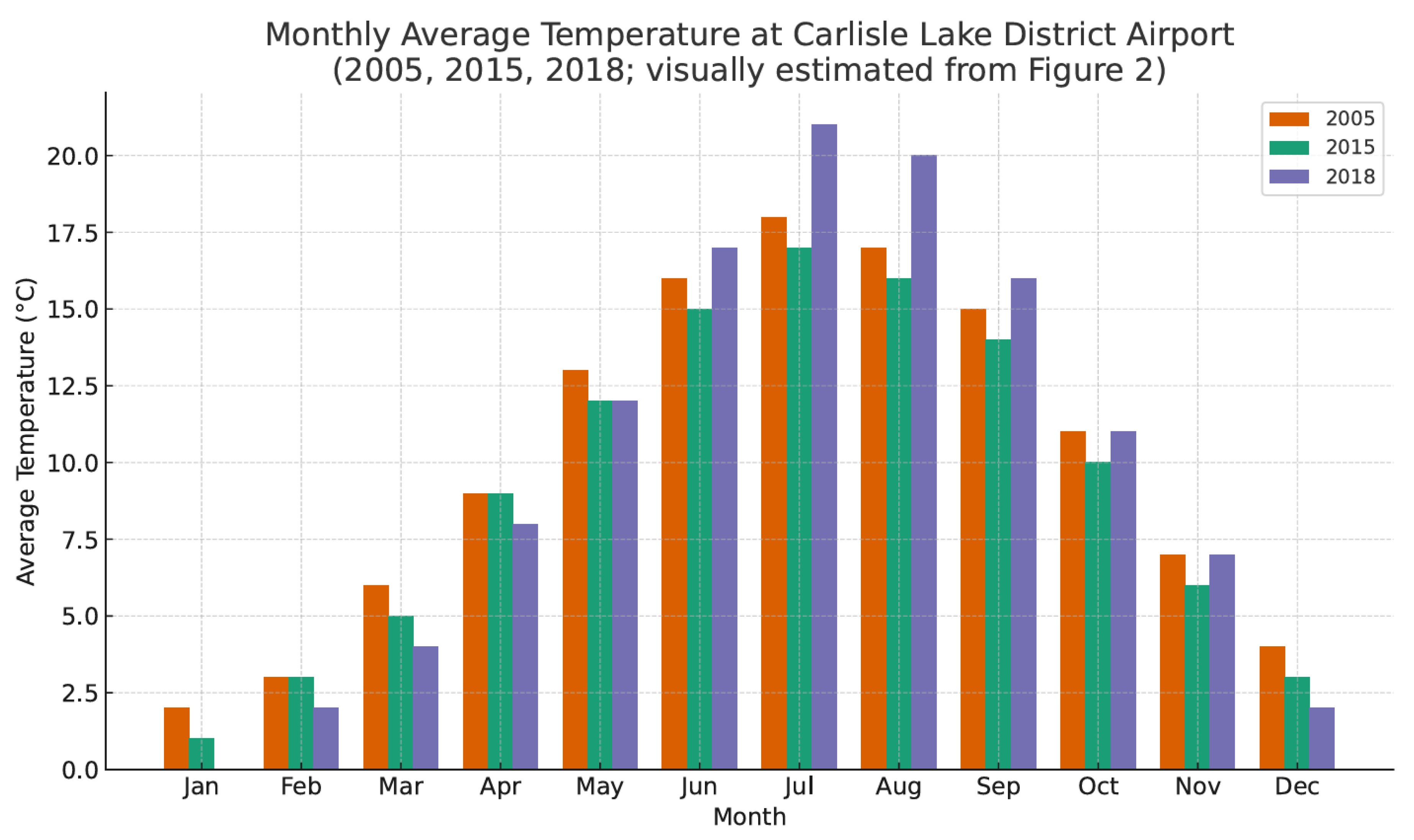

Figure 2.

Observed Weather in 2005,2015, and 2018 at Carlisle Lake District Airport (The data for this report comes from the Carlisle Lake District Airport).

Figure 2.

Observed Weather in 2005,2015, and 2018 at Carlisle Lake District Airport (The data for this report comes from the Carlisle Lake District Airport).

The Carlisle region of the United Kingdom has the same problem. Climate change has led to an increase in the incidence of extreme weather events, thereby increasing the risk of flooding. In January 2005, Carlisle was hit by extreme rainfall, which led to the flooding of three major rivers (the Eden, the Petrel, and the Caldor). Despite upgrades to flood defences, Storm Desmond in December 2015 caused severe flooding in Carlisle. The flooding exceeded the standard of protection set in 2005 and resulted in the flooding of over 1,000 residential and commercial properties, as well as damage to infrastructure (Convery and Bailey,. The Environment Agency subsequently launched a Pound25 million three-phase flood improvement programme aimed at increasing protection and taking climate change into account.

The Carlisle area has experienced numerous severe floods over the past 20 years, highlighting the inadequacy of flood defenses in coping with extreme weather. Whilst the Government and relevant agencies have taken steps to strengthen flood defences, delays and underfunding of projects remain major issues (Pattison et al.,. As the challenges posed by climate change intensify, there is an urgent need to accelerate the upgrading and maintenance of flood defenses in Carlisle and other flood-prone areas in order to safeguard the lives and property of residents (Convery and Bailey 2008).

New Orleans in the United States and the Carlisle area in the United Kingdom have similar policies, although they can block flooding in the area. However, when the carrying capacity of the floodplain exceeds the proper flood range, it still poses a threat to the people in the area. Moreover, one of the primary reasons for this is the increase in extreme weather. The increase in climate extremes has also rendered the original floodplain insufficient to support the area's flood defence needs.

4.3. Urban Sprawl

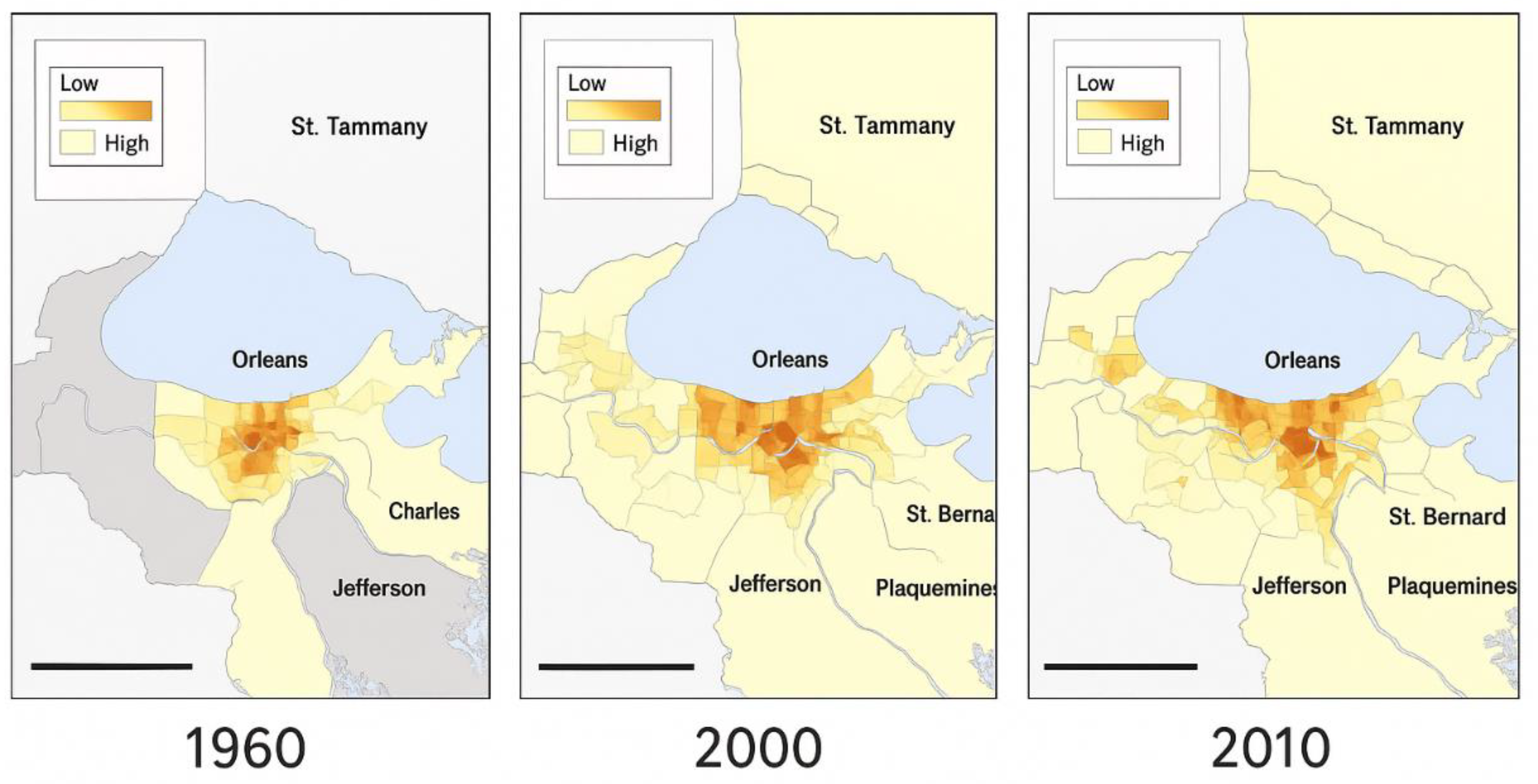

In addition to climate change causing the floodplain to lose its proper flood protection, another primary reason is urban sprawl, which occupies the land of the original wetland. As shown in

Figure 3, all three maps depict the southeastern Louisiana region, with Orleans (specifically, New Orleans) as the primary city. Each of the three maps represents a map of the changes in urban sprawl in the New Orleans area of the United States. The light yellow to dark brown colors indicate a scale from “low” to “high”. As can be seen, the 1960 image shows that the towns in the region were still concentrated at the junction of the three rivers. Beginning in 2000, as the population of the region increased, the towns began to expand along the rivers. By 2000, the surrounding coastal areas had become urban. By 2010, this graph shows that the towns are still expanding, but have stabilized regionally. This is due to the stabilization of population growth in the area.

As a result of urban sprawl in the New Orleans area of the United States, this has been a reduction in wetlands. In the midst of a research study addressing land area changes in coastal Louisiana. The study utilized satellite data to quantify landscape changes between 1932 and 2016. The analysis revealed a net decrease of approximately 4,833 square kilometers of land area in coastal Louisiana, equivalent to a 25% reduction from the 1932 land area (Couvillion et al.,. The decline of wetlands in the New Orleans area is the result of a combination of natural and anthropogenic factors. Although the rate of wetland loss has slowed in recent years, wetland ecosystems remain under significant pressure due to the ongoing impacts of climate change and human activities. Urban expansion is inevitable due to a range of demands, including population growth and the desire for an improved quality of life. On this basis, the urban resilience of the area should be maintained as much as possible. This makes the area resilient to flooding. Therefore, continued research and effective management measures are essential to protect and restore these critical ecosystems.

4.4. Limited Applicability of Flood Control Strategies in the Floodplain

4.4.1. Constraints of Environmental Factors

Natural conditions play a fundamental role in determining the suitability of flood control strategies. Located in the low-lying Mississippi River Delta, with approximately 80% of the city below sea level, New Orleans' flood threat is not only from riverine inundation but is also closely associated with hurricane storm surges and saltwater backup (Raymond J. Burby,. There is a high reliance on dyke systems and pumping facilities, and when infrastructure fails, flooding can be catastrophic. In contrast, Carlisle, UK, is situated at the confluence of the rivers Eden, Petrel, and Caldew, where flooding is primarily caused by stormwater runoff and surface catchments, and is exacerbated by extreme weather events (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,. While both locations have adopted a flood control strategy for the floodplain, the applicability of this strategy varies widely.

As a result, in the New Orleans area, levees and pumping devices constructed using manual techniques are still primarily used to protect against flooding (Burby 2001). This is mainly limited by the fact that the area does not have a relatively large open area to channel floodwaters into, like the Carlisle area has(Cutter et al. 2018). Additionally, Carlisle's floodplain detention mechanisms are unable to cope with the high tide level storm surges experienced in New Orleans. Thus, the effectiveness of flood control policies must be tailored to the geographic characteristics of specific watersheds rather than being generalized as a generic template.

4.4.2. Impact of Government Governance Capacity

Government governance capacity determines the depth and sustainability of floodplain policy implementation. Post-Katrina restoration exposed the fragmentation of the bureaucracy and the lag in the deployment of funds(Burby 2006). In contrast, while Carlisle's governance structure was relatively centralized, the local government had limited financial resources. It lacked the capacity to adjust policies to extreme weather contexts (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,. Policy revisions following the floods primarily involved paper-based planning, resulting in a disconnect between actual regulations and their implementation. In addition, local governments in the UK tend to respond to people's opinions through formalized reviews, but often still compromise with development capital in land planning approvals (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,. As a result, insufficient governance capacity not only weakens the effectiveness of flood prevention strategies but also limits their replication in similar areas.

At the same time, the current floodplain's extent and flood capacity cannot keep pace with the rate of climate deterioration. This is particularly true in the Carlisle area, which is increasingly flooded by floodplains that have fallen into disrepair (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,. The area has even shifted from being one where floods could be stored to one that is more prone to flooding (Neil Entwistle and George Heritage,. The government must obtain numerous approvals when planning for the area, which slows down the maintenance and reconstruction of the floodplain. Thus, it also delays many construction projects.

Overall, the applicability of flood control strategies in the Panhandle is not dependent on their technological maturity but is influenced by a combination of natural conditions and governmental governance capacity. The cases of New Orleans and Carlisle clearly show that geomorphic differences determine the boundaries of the strategy, and governance fragmentation stalls policy implementation. Together, these factors are the structural causes of the “non-replicability” of flood control strategies. Therefore, any cross-regional transplantation of flood control policies must be based on local environmental assessments and incorporate social justice, spatial planning, and governance capacity into the overall framework; otherwise, the strategies will not only be challenging to implement, but may also trigger new social and environmental risks.

4.5. Conflict Between Floodplain Policies and Citizen Participation

In the sociological sense, civic participation refers to the public occupying a specific position and playing a particular role in the formulation, implementation, and monitoring of public policies (Houser et al., 2022). This section will focus on community residents. This idea directly relates to a crucial sociological concept: citizen participation. Since citizens are the direct bearers of the entire flood problem, their opinions will be critical. In some developing countries, citizen participation is relatively low (Hudson et al., 2019). Even in some developed countries, although citizen participation is practiced (Houser et al., 2022), final policy decisions often favor developers and vested interests. However, the actual situation often deviates from this ideal(Venkataramanan et al., 2019).

In many developing countries, mechanisms for citizen participation are immature and lack effective channels for information sharing(Priest et al., 2016). Citizens themselves are less aware of the importance of political participation due to economic development. The government and capital mostly dominate the policy-making process. In some developed countries, although there are channels for citizen consultation, hearing, and policy feedback at the institutional level, in practice, there are still problems such as “superficiality of participation”, “exclusion of participation”, and “tendency of decision-making to develop interests”. "The public's views are not always heard. Even when the public expresses its opinion, the final policy direction is often still in favor of land developers, investment groups, or groups with vested interests(Mehring et al. 2018).

Take the flood policies of the United Kingdom and the United States, for example (Huq and Stubbings 2015). The United Kingdom typically emphasizes “public participation” and “consultative governance” in the formulation of flood control policies, but in practice, the process is often standardized (Priest et al.,. Take Carlisle as an example; the city is located in a low-lying area where several rivers meet and has experienced severe flooding many times in its history. Before planning flood prevention policies, the UK government and local authorities encourage residents to participate in discussions to gather views on flood storage areas, land use, and relocation plans (Spencer et al.,. However, the final policy outcome often still tends to satisfy the interests of developers and local economic development. For example, under the pressure of housing shortages or urban renewal, even if there is strong public opposition to building projects in high-risk areas, the local government may still authorize development on the grounds of “planning balance” or “economic necessity”(Abass et al. 2020). At the same time, foreign residents and tenant groups are marginalized in civic engagement mechanisms. They are unfamiliar with local regulations, community networks, and the deliberation process, so their motivation and cooperation are naturally low. In consultation questionnaires, hearings, and community meetings, these groups often lack organization and representation, resulting in policy outcomes that reflect the voices of the “capable participants”. Over time, a disconnect develops between “procedural participation” and “substantive listening”, resulting in a decline in community acceptance of and cooperation with policy implementation, and a weakening of the social basis for floodplain planning (Mehring et al.,.

Flood management in the U.S. is highly dependent on local governments and community organizations, and community culture and stratification profoundly affect the effectiveness of civic engagement(Burby 2006). In New Orleans, for example, which was devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the flooding revealed multiple problems in urban planning, engineering, and social inequality. The ability to participate before, during, and after the flood differed significantly between affluent and poor neighborhoods (Cutter et al. 2018). Better-educated and better-off communities were more familiar with the language of policy, had higher levels of trust in governmental mechanisms and experience in deliberation, and were therefore more likely to exert influence in negotiations and reconstruction (Burby 2001). On the contrary, some chronically poor communities have a weaker ability to anticipate, understand, and respond to government policies, a limited willingness to cooperate with official surveys and community planning, and a low perception of flood risk. This has led to their lower resilience in the face of floods and slower post-disaster recovery (Kates et al. 2006). At the same time, due to weak participation, they lack representation at the policy formulation stage and often struggle to advocate for infrastructure rehabilitation, housing subsidies, or fair resource allocation. In the long run, instead of being weakened by policy governance, floods may further widen the wealth and security gap between communities and intensify social conflicts. These tensions can also push back on policies, in some cases triggering more complex community resistance or political demands, which in turn affect floodplain management and urban governance structures.

5. Conclusions

The 2005 flood events in New Orleans and Carlisle exemplify the structural deficiencies in floodplain governance and urban flood management infrastructure when confronted with severe weather phenomena. The contrasting geomorphic characteristics of these locations—deltaic lowlands versus river confluence zones—determined the scope of their respective flood control measures. Moreover, ongoing urban sprawl, wetland degradation, and land hardening have further diminished the natural buffering capacity. These floods have exposed a deficiency in coordination between engineering infrastructure and ecosystem management, highlighting the current flood control system's inability to effectively respond to extreme precipitation and flood peaks surpassing original design parameters.

Furthermore, inadequate financial inputs, fragmented governance, and delayed policy implementation have undermined the capacity of local governments to effectively respond to risks over the long term. The urban sprawl of New Orleans, primarily driven by wetland development and the oil industry, has resulted in the loss of 25% of its coastal land. Conversely, Carlisle's defenses have failed due to the expansion of hard surfaces and drainage failures, despite the existence of a floodplain. The cases of both locations demonstrate that the success of flood control strategies is not solely dependent on technological sophistication but is also limited by factors such as natural conditions, governance capacity, spatial planning, and community participation.

The social dimension likewise constitutes a significant dividing line in floodplain management. The practice of New Orleans has demonstrated that social stratification considerably influences residents' capacity to engage in pre-disaster preparation, disaster response, and post-disaster reconstruction, resulting in disparities in policy resources and recovery velocity, and potentially amplifying social inequality over time. Floodplain policies that neglect social vulnerability and justice principles are not only challenging to replicate but may also engender secondary risks.

Therefore, flood control policies in floodplains must be grounded in suitable environmental conditions and should integrate ecological restoration, spatial planning, social equity, and governance capacity within the comprehensive governmental framework. The future flood mitigation system ought to transition from “engineering defense” to “resilient governance,” establishing a multi-level flood prevention mechanism capable of addressing extreme weather events through restoring floodplain functions, increasing community participation, and reinforcing financial and institutional safeguards.

References

- Abass, Kabila, Daniel Buor, Kwadwo Afriyie, Gift Dumedah, Alex Yao Segbefi, Lawrence Guodaar, Emmanuel Kofi Garsonu, Samuel Adu-Gyamfi, David Forkuor, Andrews Ofosu, Abass Mohammed, and Razak M. Gyasi. 2020. ‘Urban Sprawl and Green Space Depletion: Implications for Flood Incidence in Kumasi, Ghana’. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 51:101915. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101915.

- Brasted, Chelsea. 2025. ‘You are Not Wrong: New Orleans’ Rainstorms Are Getting More Intense’. https://www.axios.com/local/new-orleans/2025/04/22/new-orleans-rainstorms-more-intense-flooding-rain.

- Brunkard, Joan, Gonza Namulanda, and Raoult Ratard. 2008a. ‘Hurricane Katrina Deaths, Louisiana, 2005’. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2(4):215–23. doi:10.1097/DMP.0b013e31818aaf55.

- Brunkard, Joan, Gonza Namulanda, and Raoult Ratard. 2008b. ‘Hurricane Katrina Deaths, Louisiana, 2005’. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2(4):215–23. doi:10.1097/DMP.0b013e31818aaf55.

- Burby, Raymond J. 2001. ‘Flood Insurance and Floodplain Management: The US Experience’. Global Environmental Change Part B: Environmental Hazards 3(3):111–22. doi:10.3763/ehaz.2001.0310.

- Burby, Raymond J. 2006. ‘Hurricane Katrina and the Paradoxes of Government Disaster Policy: Bringing About Wise Governmental Decisions for Hazardous Areas’. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 604(1):171–91. doi:10.1177/0002716205284676.

- Cass, Evan, Wanyun Shao, and Kevin Smiley. 2022. ‘Comparing Public Expectations with Local Planning Efforts to Mitigate Coastal Hazards: A Case Study in the City of New Orleans, USA’. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 74:102940. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102940.

- Colten, Craig E. 2018. ‘Raising New Orleans: Historical Analogs and Future Environmental Risks’. Environmental History 23(1):135–42. doi:10.1093/envhis/emx097.

- Convery, I. Convery, I., and C. Bailey. 2008. ‘After the Flood: The Health and Social Consequences of the 2005 Carlisle Flood Event’. Journal of Flood Risk Management 1(2):100–109. doi:10.1111/j.1753-318X.2008.00012.x.

- Couvillion, Brady R., Holly Beck, Donald Schoolmaster, and Michelle Fischer. 2017. Land Area Change in Coastal Louisiana (1932 to 2016). 3381. U.S. Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/sim3381.

- Cutter, Susan L., Christopher T. Emrich, Melanie Gall, and Rachel Reeves. 2018. ‘Flash Flood Risk and the Paradox of Urban Development’. Natural Hazards Review 19(1):05017005. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000268.

- Dadson, Simon J., Jim W. Hall, Anna Murgatroyd, Mike Acreman, Paul Bates, Keith Beven, Louise Heathwaite, Joseph Holden, Ian P. Holman, Stuart N. Lane, Enda O’Connell, Edmund Penning-Rowsell, Nick Reynard, David Sear, Colin Thorne, and Rob Wilby. 2017. ‘A Restatement of the Natural Science Evidence Concerning Catchment-Based “Natural” Flood Management in the UK’. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 473(2199):20160706. doi:10.1098/rspa 2016.0706.

- Dillenardt, Lisa, Paul Hudson, and Annegret H. Thieken. 2022. ‘Urban Pluvial Flood Adaptation: Results of a Household Survey across Four German Municipalities’. Journal of Flood Risk Management 15(3):e12748. doi:10.1111/jfr3.12748.

- Eleonora Rohland. 2017. ‘Adapting to Hurricanes. A Historical Perspective on New Orleans from Its Foundation to Hurricane Katrina, 1718–2005 - Rohland - 2018 - WIREs Climate Change - Wiley Online Library’. https://wires.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wcc.488?casa_token=uiP2vFSJVI0AAAAA%3Aa1ZwalfFExUGvl0fxGHJsXxDHQEbJpNcvfg9mX3brRXThdyLR98p6itVuFEVcHxvK5zuOe2gYmlRM-s6.

- Elizabeth Fussell. 2007. ‘Constructing New Orleans, Constructing Race: A Population History of New Orleans | Journal of American History | Oxford Academic’. https://academic.oup.com/jah/article-abstract/94/3/846/776862.

- Houser, Matthew, Beth Gazley, Heather Reynolds, Elizabeth Grennan Browning, Eric Sandweiss, and James Shanahan. 2022. ‘Public Support for Local Adaptation Policy: The Role of Social-Psychological Factors, Perceived Climatic Stimuli, and Social Structural Characteristics’. Global Environmental Change 72:102424. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102424.

- Hudson, Paul, W. J. Wouter Botzen, Jennifer Poussin, and Jeroen C. J. H. Aerts. 2019. ‘Impacts of Flooding and Flood Preparedness on Subjective Well-Being: A Monetisation of the Tangible and Intangible Impacts’. Journal of Happiness Studies 20(2):665–82. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9916-4.

- Hupp, Cliff R., Aaron R. Pierce, and Gregory B. Noe. 2009. ‘Floodplain Geomorphic Processes and Environmental Impacts of Human Alteration along Coastal Plain Rivers, USA’. Wetlands 29(2):413–29. doi:10.1672/08-169.1.

- Huq, Nazmul, and Alexander Stubbings. 2015. ‘How Is the Role of Ecosystem Services Considered in Local Level Flood Management Policies: Case Study in Cumbria, England’. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management 17(04):1550032. doi:10.1142/S1464333215500325.

- Jonkman, Sebastiaan N., Bob Maaskant, Ezra Boyd, and Marc Lloyd Levitan. 2009. ‘Loss of Life Caused by the Flooding of New Orleans After Hurricane Katrina: Analysis of the Relationship Between Flood Characteristics and Mortality’. Risk Analysis 29(5):676–98. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01190.x.

- Kates, R. W., C. Kates, R. W., C. E. Colten, S. Laska, and S. P. Leatherman. 2006. ‘Reconstruction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: A Research Perspective’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103(40):14653–60. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605726103.

- Klijn, Frans, Heidi Kreibich, Hans de Moel, and Edmund Penning-Rowsell. 2015. ‘Adaptive Flood Risk Management Planning Based on a Comprehensive Flood Risk Conceptualisation’. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 20(6), 845–864. doi:10.1007/s11027-015-9638-z.

- Marquardt, Jens. 2017. ‘Central-Local Relations and Renewable Energy Policy Implementation in a Developing Country’. Environmental Policy and Governance, 27(3), 229–43. doi:10.1002/eet.1756.

- Marsh, Terry, Celia Kirby, Katie Muchan, Lucy Barker, Ed Henderson, and Jamie Hannaford. 2016. The Winter Floods of 2015/2016 in the UK - a Review. Wallingford: NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology.

- Mehring, P., H. Mehring, P., H. Geoghegan, H. L. Cloke, and J. M. Clark. 2018. ‘What Is Going Wrong with Community Engagement? How Flood Communities and Flood Authorities Construct Engagement and Partnership Working’. Environmental Science & Policy 89:109–15. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2018.07.009.

- Neil Entwistle and George Heritage. 2016. ‘UK Floods – Changes to Our Rivers and Floodplains Have Exacerbated Flooding – FloodList’. https://floodlist.com/protection/uk-floods-changes-rivers-floodplains-exacerbated-flooding.

- Neil Entwistle and George Heritage. 2017. ‘UK – 90% of Floodplains No Longer Work Properly, Study Reveals – FloodList’. https://floodlist.com/protection/floodplains-study.

- Pattison, I., S. N. Lane, R. J. Hardy, and S. Reaney. 2009. ‘Long Term Changes in Flood Risk in the Eden Catchment, Cumbria: Links to Changes in Weather Types and Land Use’. P. 9555 in.

- Priest, Sally J., Cathy Suykens, Helena F. M. W. Van Rijswick, Thomas Schellenberger, Susana Goytia, Zbigniew W. Kundzewicz, Willemijn J. van Doorn-Hoekveld, Jean-Christophe Beyers, and Stephen Homewood. 2016. ‘The European Union Approach to Flood Risk Management and Improving Societal Resilience: Lessons from the Implementation of the Floods Directive in Six European Countries’. Ecology and Society 21(4). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26270028.

- Raymond J. Burby. 2006. ‘Hurricane Katrina and the Paradoxes of Government Disaster Policy: Bringing About Wise Governmental Decisions for Hazardous Areas’. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0002716205284676?casa_token=u5BjhiHWaFEAAAAA:vN4q1uKrOg1t9JTHPT2koIWTtajdUsZphfoE01R5T04fhxaR_b5T1vaHO6v-JobrZ-H-xgiCiU6P6w.

- Roberts, Nigel M., Steven J. Cole, Richard M. Forbes, Robert J. Moore, and Daniel Boswell. 2009. ‘Use of High-Resolution NWP Rainfall and River Flow Forecasts for Advance Warning of the Carlisle Flood, North-West England’. Meteorological Applications 16(1):23–34. doi:10.1002/met 94.

- Rohland, Eleonora. 2018. Changes in the Air: Hurricanes in New Orleans from 1718 to the Present. Berghahn Books.

- Seed, R. B., R. G. Bea, A. Athanasopoulos-Zekkos, G. P. Boutwell, J. D. Bray, C. Cheung, D. Cobos-Roa, L. Ehrensing, L. F. Harder, J. M. Pestana, M. F. Riemer, J. D. Rogers, R. Storesund, X. Vera-Grunauer, and J. Wartman. 2008. ‘New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina. II: The Central Region and the Lower Ninth Ward’. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering 134(5):718–39. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2008)134:5(718).

- Spencer, Peter, Duncan Faulkner, Ian Perkins, David Lindsay, Guy Dixon, Matthew Parkes, Andrew Lowe, Anita Asadullah, Kim Hearn, Liam Gaffney, Adam Parkes, and Richard James. 2017. ‘The Floods of December 2015 in Northern England: Description of the Events and Possible Implications for Flood Hydrology in the UK’. Hydrology Research 49(2):568–96. doi:10.2166/nh.2017.092.

- Venkataramanan, Vidya, Aaron I. Packman, Daniel R. Peters, Denise Lopez, David J. McCuskey, Robert I. McDonald, William M. Miller, and Sera L. Young. 2019. ‘A Systematic Review of the Human Health and Social Well-Being Outcomes of Green Infrastructure for Stormwater and Flood Management’. Journal of Environmental Management 246:868–80. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.05.028.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).