1. Introduction

Acute heart failure (AHF) remains one of the most common cardiovascular emergencies, responsible for millions of hospital admissions each year and associated with high short-term mortality and rehospitalization rates [

1,

2]. The underlying mechanisms leading to this unfavorable outcome are complex, involving abrupt shifts in preload and afterload, neurohormonal activation, and variable contributions from both ventricles [

3,

4]. Importantly, prognosis is not uniform across phenotypes: patients with HFrEF differ in clinical course and outcomes from those with HFpEF [

5,

6].

Early risk stratification is essential to guide management decisions but remains challenging in routine practice. Clinical assessment alone has limited prognostic accuracy [

7], and although biomarkers such as NT-proBNP are powerful diagnostic and prognostic tools [

8,

9,

10], their availability may be delayed or restricted in some clinical contexts. Echocardiography provides immediate, bedside information and is central to the evaluation of both left and right ventricular function [

11,

12]. In routine clinical practice, echocardiographic evaluation in acute settings primarily focuses on left ventricular function, while right ventricular assessment may be more challenging and, at times, overlooked due to technical or time constraints. However, right ventricular performance plays a crucial role in determining outcomes in AHF. This rationale supports the development of a simple, rapid, and feasible index capable of simultaneously evaluating both ventricles at the bedside.

Several echocardiographic parameters have been linked to outcomes in AHF. The left ventricular outflow tract velocity–time integral (LVOT VTI), reflecting forward stroke volume, has shown prognostic relevance in both chronic and acute settings [

13,

14]. On the right side, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) and the tricuspid regurgitation–derived pressure gradient are established indices of right ventricular systolic performance and pulmonary pressures [

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, each parameter reflects only a limited dimension of cardiac function. Emerging evidence highlights the importance of ventricular interdependence, whereby right- and left-sided haemodynamics are dynamically coupled, influencing both symptoms and outcomes [

19].

To capture this interaction, we proposed a new tool - the Virtue index ,defined as the ratio of the right ventricular to right atrial pressure gradient (RV–RA gradient) to the product of TAPSE and LVOT VTI [

20]. Early findings suggested that this composite measure may offer incremental prognostic information by integrating right ventricle (RV) load, longitudinal systolic function, and left ventricle (LV) forward flow. Nonetheless, validation remains limited, and it is not clear whether its prognostic value is consistent across phenotypes defined by ejection fraction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

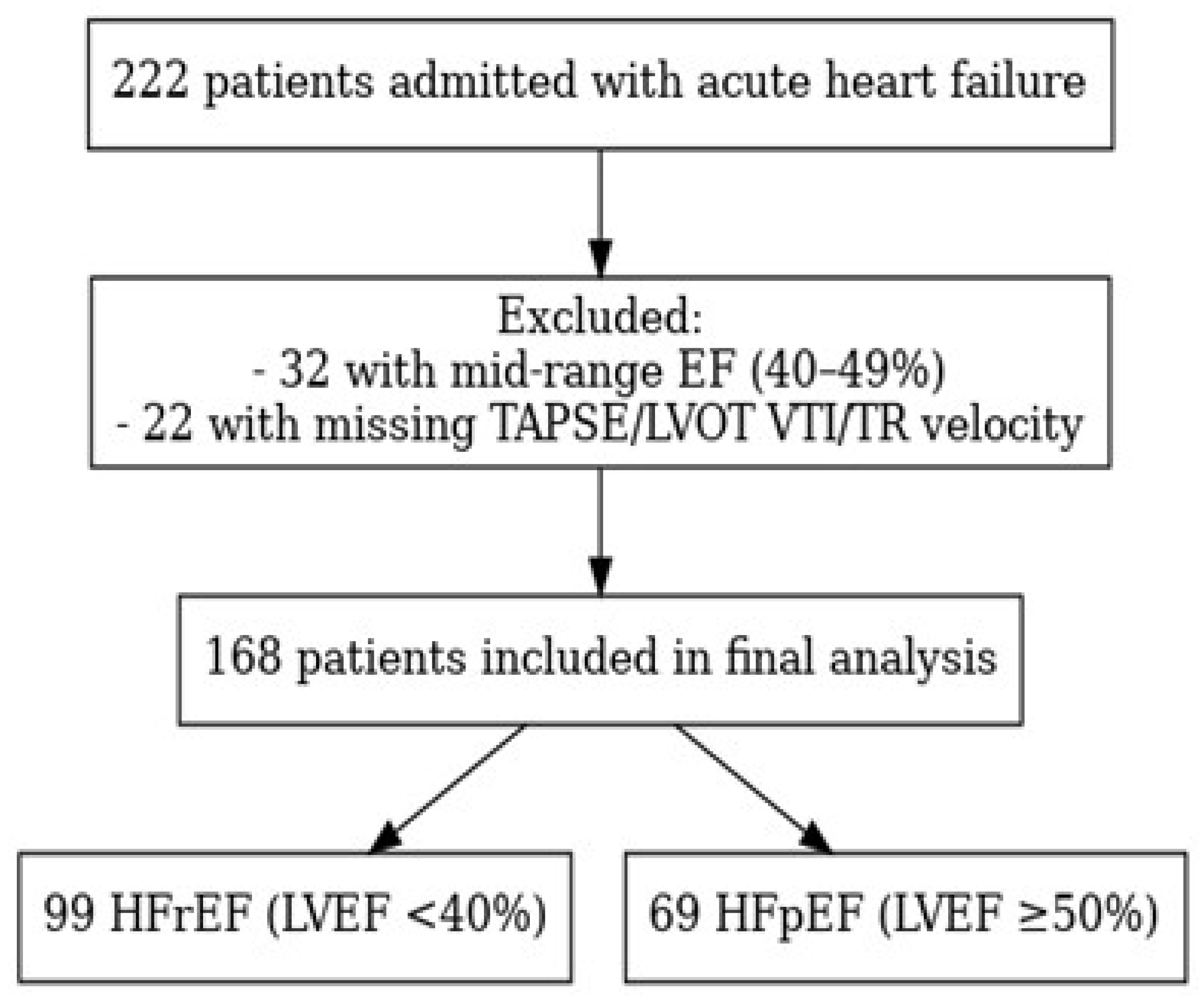

We conducted a retrospective analysis including patients admitted with AHF between January 2024 and June 2025 at St. Pantelimon Clinical Emergency Hospital in Bucharest, Romania. The diagnosis of AHF was established in accordance with the 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines for the management of acute and chronic heart failure [

21]. Patients with missing echocardiographic parameters necessary for the calculation of the Virtue Index were excluded from the analysis. The final study cohort consisted of 222 patients, among whom 99 presented with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, <40%) and 69 with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, ≥50%), whereas individuals with mid-range ejection fraction values (40–49%) were not included.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Emergency Clinical Hospital “Sf. Pantelimon”, Bucharest (Approval No. 77 / 09.09.2024).

The flow of patient selection is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Echocardiographic Assessment

Comprehensive transthoracic echocardiography was performed within the first hours after hospital admission, following standard acquisition protocols and current recommendations for chamber quantification [

22] and diastolic function assessment [

23]. All echocardiographic examinations were performed by experienced cardiologists certified in echocardiography, using the same General Electric Vivid E95 ultrasound system. The following parameters were assessed: left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by Simpson’s biplane method, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) measured in the apical four-chamber view using M-mode [

24], left ventricular outflow tract velocity–time integral (LVOT VTI) obtained by pulsed-wave Doppler in the apical five-chamber view [

13,

14], and the right ventricular-to-right atrial systolic pressure gradient (RV–RA gradient) derived from the peak velocity of tricuspid regurgitation using the modified Bernoulli equation [

24].

The Virtue Index was calculated as:

This index was previously proposed as an integrative marker reflecting the interaction between right ventricular systolic load, longitudinal contractile function, and left ventricular forward flow [

20]. In the present study, the same formula was applied to all patients to explore its prognostic significance across different ejection fraction phenotypes.

2.3. Biomarker Measurement

Blood samples were obtained at admission, prior to initiation of intravenous therapy. Plasma NT-proBNP concentrations were measured using an electrochemiluminescent immunoassay (Elecsys® proBNP II, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Results were expressed in pg/mL. NT-proBNP was selected as a comparator biomarker due to its well-established diagnostic and prognostic significance in AHF, as demonstrated in several pivotal studies [

25,

26,

27].

2.4. Outcomes

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the prognostic performance of the Virtue Index for in-hospital all-cause mortality.

Secondary analyses included assessment of the relationship between the Virtue Index and NT-proBNP at admission and comparison of its discriminative ability with conventional echocardiographic parameters (TAPSE, RV–RA gradient , and LVOT VTI.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Comparisons between groups used the Student t-test for normally distributed data [

28] or the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables [

29]. Categorical variables were compared with the χ² test.

Associations between the Virtue Index and NT-proBNP were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, with 1,000 bootstrap replicates to obtain 95% confidence intervals. Prognostic performance for in-hospital mortality was assessed with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and area under the curve (AUC), with bootstrap confidence intervals. Pairwise comparisons of AUC values were performed using DeLong’s test for correlated ROC curves [

30].

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.2) and Python (version 3.10).

Generative artificial intelligence tools (ChatGPT, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) were used for figure generation and minor linguistic adjustments to improve text clarity and readability.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Baseline demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics were compared between patients with reduced (HFrEF) and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Detailed results are presented in

Table 1.

Patients with HFpEF were significantly older than those with HFrEF (77.6 ± 9.6 vs. 65.9 ± 14.9 years, p < 0.001) and were more frequently female (72.5% vs. 33.3%, p < 0.001). Smoking was considerably less common in the HFpEF group (8.7% vs. 36.4%, p < 0.001). Hypertension was more prevalent in HFpEF (95.7% vs. 82.8%, p = 0.017), while dyslipidaemia showed a similar prevalence across groups (94.2% vs. 94.9%, p = 0.83). Obesity (24.6% vs. 30.3%, p = 0.46) and diabetes mellitus (37.7% vs. 41.4%, p = 0.63) did not differ significantly between groups. Valvular heart disease was slightly more common in HFrEF (80.8% vs. 73.9%, p = 0.29).

Hemodynamic parameters were broadly comparable, with no significant difference in systolic blood pressure (143 ± 31 in HFrEF vs. 142 ± 31 mmHg in HFpEF, p = 0.83), while diastolic pressure was slightly higher in HFrEF (87 ± 17 vs. 81 ± 17 mmHg, p = 0.02). Median NT-proBNP levels were numerically higher in HFrEF (8453 [4957–21121] pg/mL) than in HFpEF (6537 [2180–24554] pg/mL), though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.41).

Echocardiographic findings were consistent with the expected phenotypic pattern. TAPSE values were similar between groups (20 ± 10 mm vs. 21 ± 7 mm, p = 0.41), whereas LVOT VTI was markedly lower in HFrEF (14 ± 4 cm vs. 21 ± 7 cm, p < 0.001). As anticipated, LVEF differed profoundly (28 ± 7% vs. 60 ± 7%, p < 0.001). The RV–RA gradient was significantly higher in HFpEF (21 [17–24] mmHg) compared with HFrEF (17 [14–22] mmHg, p < 0.001), reflecting greater pulmonary pressure load.

The Virtue Index, reflecting the integrated right–left ventricular interaction, was significantly higher in HFrEF than in HFpEF [0.135 (0.069–0.215) vs. 0.075 (0.049–0.110), p < 0.001], consistent with the more pronounced systolic impairment characterising the reduced-EF phenotype.

3.2. Prognostic Discrimination for In-Hospital Mortality (ROC/AUC Analyses)

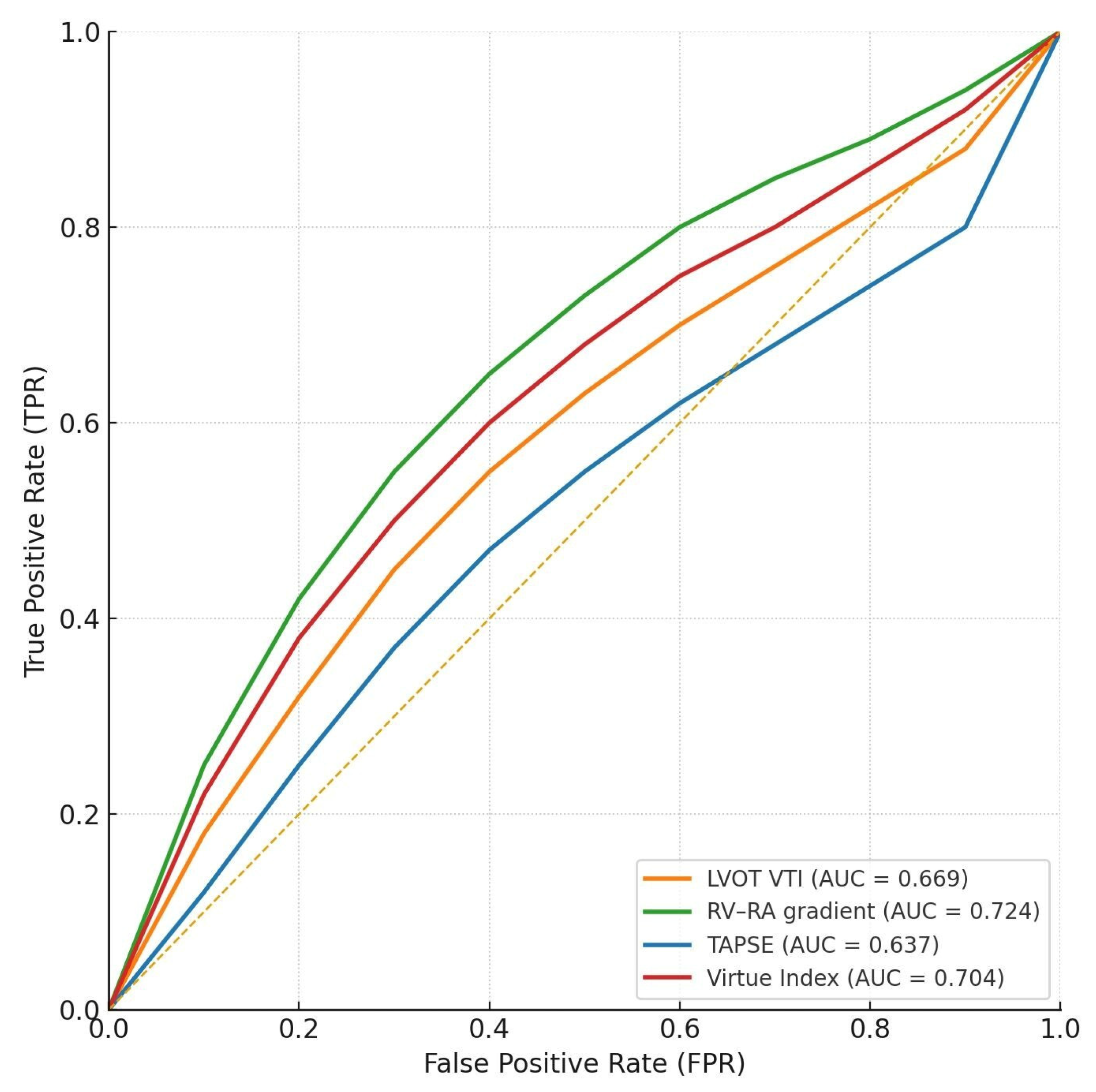

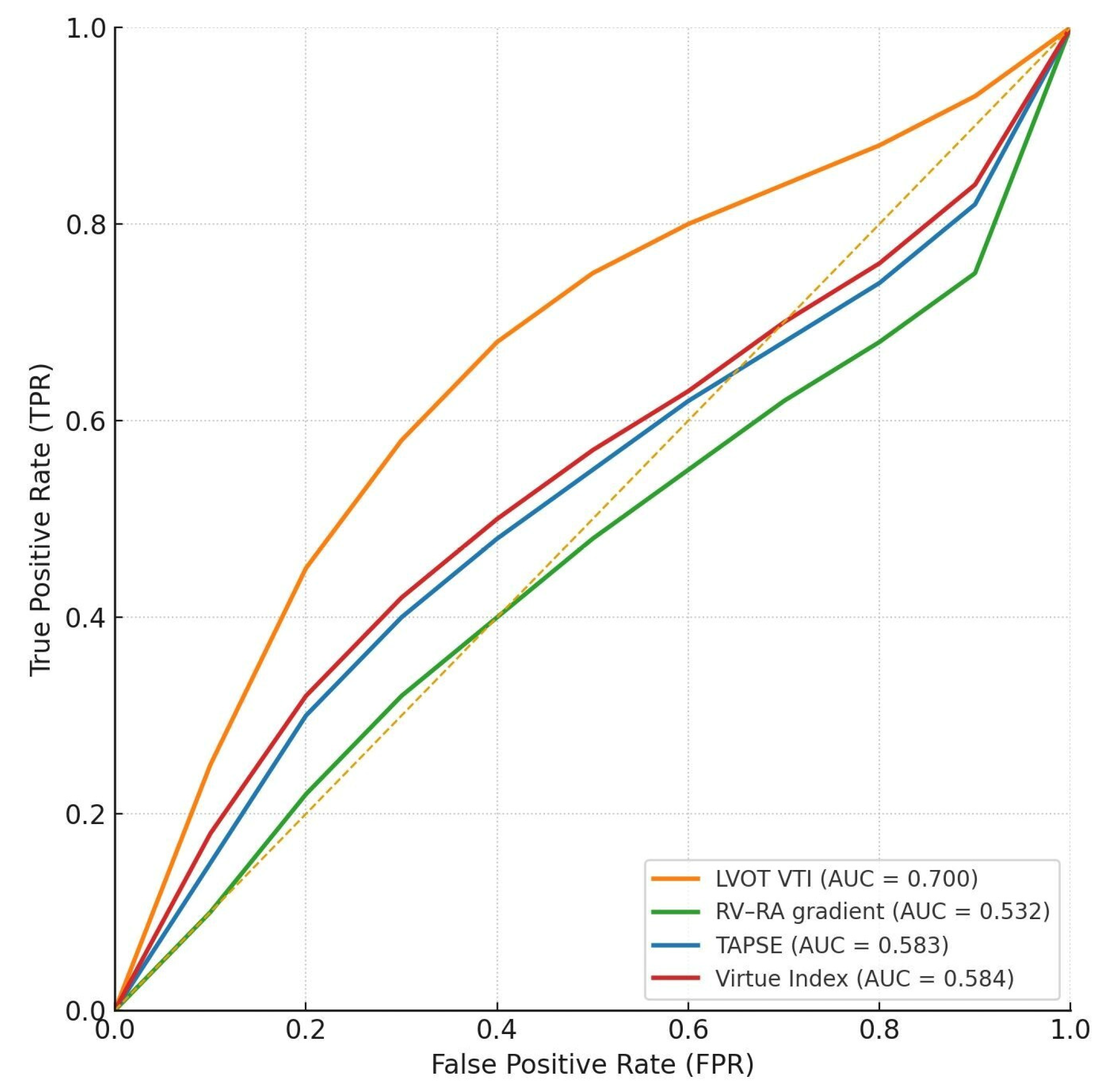

We next evaluated the discriminative ability of the Virtue Index and conventional echocardiographic parameters: RV–RA gradient, TAPSE, and LVOT VTI—for in-hospital mortality.

In the HFrEF subgroup (N = 99, 9 (9%) deaths), Virtue showed modest discrimination (AUC 0.584, 95% CI 0.36–0.79), similar to RV–RA gradient (0.532, 95% CI 0.46–0.72) and TAPSE (0.583, 95% CI 0.45–0.77). LVOT VTI performed best in this group (AUC 0.700, 95% CI 0.53–0.85).

In the HFpEF subgroup (N = 69, 8 (11.6%) deaths), Virtue achieved good discrimination (AUC 0.704, 95% CI 0.53–0.85), comparable to RV–RA gradient (0.724, 95% CI 0.54–0.90) and higher than TAPSE (0.637, 95% CI 0.45–0.89) and LVOT VTI (0.669, 95% CI 0.45–0.86).

Numerical results are shown in

Table 2, while

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 provide graphical representations of the AUC values and ROC curves for each subgroup.

Interpretation

In the HFrEF subgroup, the Virtue Index demonstrated only modest discrimination for in-hospital mortality (AUC 0.584), similar to TAPSE and RV–RA gradient—parameters traditionally recognised as limited short-term prognostic markers in advanced systolic heart failure. LVOT VTI showed the highest predictive accuracy (AUC 0.700), underscoring the dominant role of left ventricular stroke volume and forward flow in determining outcomes when systolic function is severely reduced. Thus, in patients with reduced EF, Virtue does not appear to provide additional prognostic information beyond established systolic indices.

Conversely, in the HFpEF subgroup, Virtue achieved good discrimination (AUC 0.704), comparable to RV–RA gradient (AUC 0.724) and clearly outperforming TAPSE and LVOT VTI. Its significant correlation with NT-proBNP supports its physiological relevance as an integrative marker of right–left ventricular interaction and filling pressures. In this context, where conventional systolic indices often fail to predict outcomes, composite measures such as Virtue may more accurately capture the haemodynamic determinants of prognosis.

Overall, the prognostic performance of Virtue appears phenotype-dependent—limited in HFrEF, where LV forward flow remains the main determinant of short-term outcomes, but more informative in HFpEF, reflecting the interplay between right-sided pressures, longitudinal function, and LV outflow.

3.3. Correlation Between Virtue Index and NT-proBNP

In subgroup analyses, the Virtue Index demonstrated distinct patterns of correlation with NT-proBNP levels at admission.

In the HFrEF subgroup, the correlation was weak and not statistically significant (ρ = 0.191, 95% CI −0.006–0.39, p = 0.06; N = 96 pairs). This suggests that in patients with reduced ejection fraction, where neurohormonal activation and structural remodeling are typically advanced, Virtue may add limited prognostic information beyond NT-proBNP.

In contrast, in the HFpEF subgroup, Virtue showed a moderate and statistically significant correlation (ρ = 0.380, 95% CI 0.13–0.58, p = 0.002; N = 66 pairs). This supports the biological plausibility of Virtue as an integrated marker of congestion and ventricular interaction in patients with preserved systolic function, where conventional indices often fail to capture relevant prognostic information.

These results are summarized in

Table 3. Taken together, they indicate that the relationship between Virtue and NT-proBNP may be phenotype-dependent: weak in reduced EF, but stronger and clinically relevant in preserved EF, supporting its potential role as an integrated haemodynamic marker in HFpEF.

3.4. Pairwise AUC Comparisons Between Virtue and Conventional Parameters

The discriminative ability of Virtue was directly compared with RV–RA gradient, TAPSE, and LVOT VTI using pairwise AUC differences (Hanley–McNeil approximation of the DeLong test).The results are summarized in

Table 4.

In the HFrEF subgroup (n = 99, 9 deaths – 9.1%), Virtue demonstrated marginally higher AUCs than the RV–RA gradient (ΔAUC = +0.052, Z = 0.407, p = 0.684) and TAPSE (ΔAUC = +0.001, Z = 0.008, p = 0.994), but performed slightly worse than LVOT VTI (ΔAUC = −0.116, Z = −0.894, p = 0.372). None of these differences reached statistical significance.

In the HFpEF subgroup (n = 69, 8 deaths – 11.6%), Virtue showed comparable discrimination to the RV–RA gradient (ΔAUC = −0.020, Z = −0.186, p = 0.852) and modestly higher AUCs than TAPSE (ΔAUC = +0.067, Z = 0.504, p = 0.614) and LVOT VTI (ΔAUC = +0.035, Z = 0.277, p = 0.782). Again, none of these pairwise comparisons were statistically significant.

Interpretation

In HFrEF, the Virtue Index performed similarly to RV–RA gradient and TAPSE, while LVOT VTI remained the most discriminative parameter, consistent with its established role as a marker of forward stroke volume and systolic output.

In HFpEF, Virtue exhibited comparable or slightly superior discrimination relative to conventional indices. Although these differences were not statistically significant, the index appears to integrate aspects of ventricular coupling and congestion more effectively in this phenotype.

Overall, in our study cohort, Virtue demonstrated non-inferior prognostic accuracy compared to traditional echocardiographic measures in both subgroups, with a subtle tendency toward better alignment with congestion markers in HFpEF

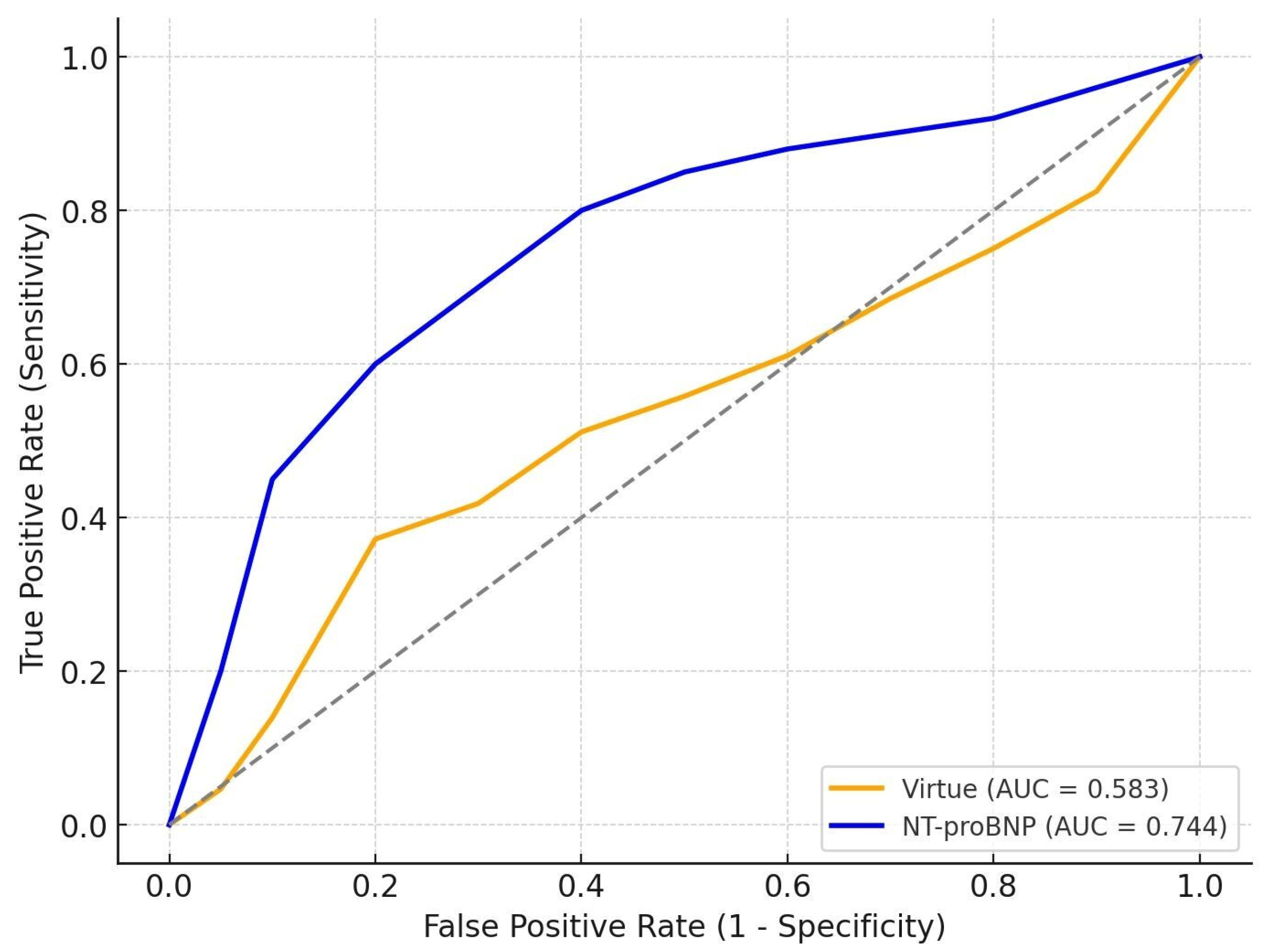

3.5. Comparative Prognostic Performance of Virtue and NT-proBNP

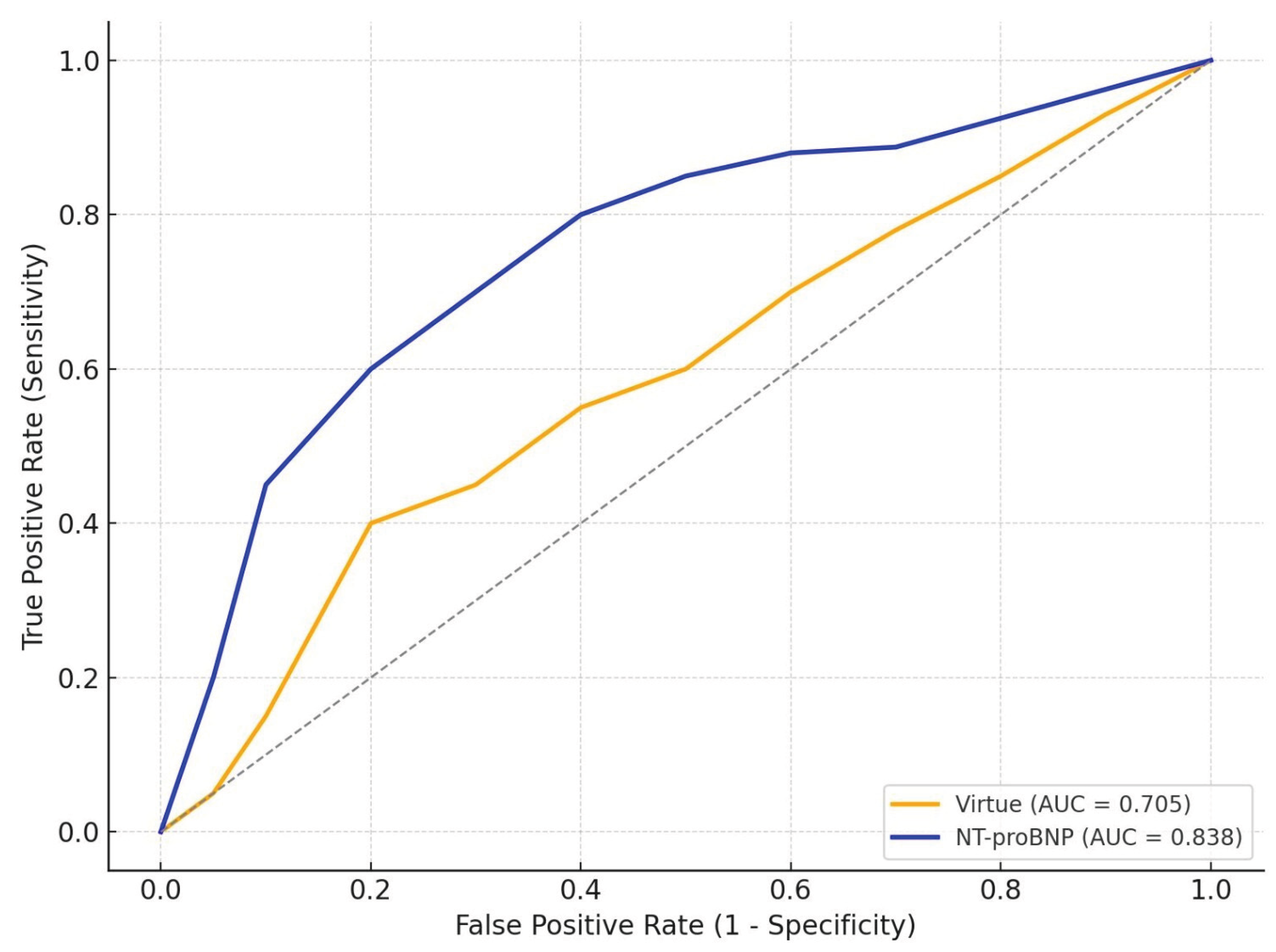

We further compared the discriminative performance of the Virtue Index with NT-proBNP at admission.

In HFrEF (N = 99, 9 deaths -9,1%), Virtue achieved AUC 0.583, while NT-proBNP reached 0.744, confirming the superior prognostic accuracy of the biomarker in systolic dysfunction.

In HFpEF (N = 69, 8 deaths – 11,6%) Virtue reached AUC 0.705, whereas NT-proBNP achieved 0.838, again outperforming the echocardiographic index in short-term mortality prediction.

Numerical results are summarized in

Table 5, and graphical representations of the ROC curves are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

Interpretation

Across both subgroups, NT-proBNP generally provided superior prognostic discrimination compared with the Virtue Index. In HFrEF, NT-proBNP showed substantially better performance (AUC 0.744 vs. 0.583, p = 0.04), underscoring its established role as a powerful marker of neurohormonal activation and decompensation in systolic heart failure. In HFpEF, Virtue achieved reasonable discrimination (AUC 0.705), although NT-proBNP remained superior (AUC 0.838, p = 0.05).

These findings suggest that while Virtue captures relevant haemodynamic information, NT-proBNP retains higher accuracy as a standalone prognostic marker in both phenotypes. Importantly, the comparable performance of Virtue in HFpEF supports its potential complementary role, particularly when echocardiography provides immediate bedside insights and NT-proBNP results may be delayed or unavailable.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to validate the Virtue Index in a cohort of patients admitted with acute heart failure (AHF) and to assess its prognostic significance across phenotypes defined by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Our findings indicate that the Virtue Index retains prognostic value, although its performance varies with phenotype. Specifically, it provided stronger discrimination and closer alignment with NT-proBNP in HFpEF, whereas its contribution was more modest in HFrEF, where parameters of forward flow dominated outcome prediction. These results extend previous observations and emphasise the importance of integrating ventricular mechanics and congestion profiles when interpreting echocardiographic prognostic markers [

32,

33,

34].

The heterogeneity of AHF continues to complicate risk assessment and management. While systolic dysfunction and reduced cardiac output characterise HFrEF, diastolic stiffness, abnormal relaxation, and ventriculo-arterial uncoupling define HFpEF [

32,

35]. These distinct mechanisms influence not only congestion patterns and filling pressures but also the prognostic interpretation of imaging and biomarker parameters. The Virtue Index—combining tricuspid regurgitation gradient with TAPSE and LVOT VTI—was conceived to capture this complex interaction between right- and left-sided function. By linking pulmonary pressure load to longitudinal contractility and stroke volume, it integrates the efficiency of biventricular coupling and the haemodynamic cost of maintaining cardiac output [

13,

18,

36].

The clinical profile of our cohort illustrates the contrasting characteristics of heart failure phenotypes [

32,

35]. Patients with HFpEF were typically older, more often women, and had a greater prevalence of atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and renal dysfunction compared with those with reduced ejection fraction [

32,

33,

34]. Despite preserved systolic function, these patients experienced higher in-hospital mortality. The combination of advanced age, multiple comorbidities, and impaired diastolic reserve likely creates a fragile physiological balance that is easily disrupted during acute decompensation [

33,

35]. Increased vascular stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, and altered ventricular–vascular coupling further limit cardiac adaptability to volume and pressure overload, resulting in greater vulnerability to congestion and instability [

33,

37].

The frequent coexistence of atrial fibrillation in HFpEF adds to this complexity by reducing atrial contribution to ventricular filling and increasing pulmonary pressures [

34,

37]. When combined with hypertension, renal impairment, and age-related vascular changes, these factors delineate a high-risk profile that explains the observed trend toward greater in-hospital mortality in HFpEF despite preserved systolic performance [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

Within this context, the interaction between right and left ventricular function appears particularly relevant in HFpEF. In this subgroup, the Virtue Index correlated significantly with NT-proBNP and achieved comparable prognostic performance to the RV–RA gradient, outperforming TAPSE and LVOT VTI. These findings are consistent with reports highlighting the central role of ventricular interdependence and pulmonary pressure adaptation in preserved-EF syndromes [

33,

37]. In HFpEF, even small increases in left ventricular filling pressure can lead to disproportionate rises in pulmonary artery pressure and early right ventricular dysfunction [

34,

37]. Consequently, both Virtue and NT-proBNP may reflect overlapping pathophysiological domains—specifically diastolic load, wall stress, and venous congestion—rather than isolated contractile impairment. This alignment supports Virtue as a feasible echocardiographic surrogate for congestion in settings where biomarker testing is delayed or unavailable [

20,

38].

In contrast, Virtue showed limited predictive ability in HFrEF, where LVOT VTI emerged as the most powerful echocardiographic predictor. This observation aligns with the established pathophysiology of systolic heart failure, in which stroke volume and forward output remain the principal determinants of short-term outcomes [

11,

12,

22]. As systolic dysfunction advances, the variability of TAPSE and tricuspid gradients narrows, diminishing the discriminative capacity of composite coupling indices. Similar attenuation has been reported for other metrics such as cardiac power output and RV/LV interaction ratios, whose incremental prognostic value declines once left ventricular contractility becomes severely impaired [

36,

39].

As expected, NT-proBNP outperformed all echocardiographic indices in both phenotypes. Nevertheless, Virtue offers a distinct practical advantage—it can be derived instantly at the bedside, providing an immediate imaging-based estimate of haemodynamic burden. This may be particularly valuable in acute presentations, where rapid clinical decisions precede laboratory confirmation. In HFpEF, where diagnostic uncertainty is frequent and conventional systolic indices are often preserved, early incorporation of Virtue into echocardiographic evaluation could refine prognostic assessment and support therapeutic prioritisation [

35,

40].

Methodologically, this study expands on the initial validation of Virtue [

20] by analysing a larger, more heterogeneous population and incorporating phenotype-specific assessment with bootstrap-derived confidence intervals. The absence of significant differences in DeLong testing likely reflects the limited number of events; nevertheless, the consistent direction of results across parameters supports the comparable performance of Virtue to established echocardiographic predictors derived from routine measurements.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective, single-centre design may introduce selection bias, and the relatively small number of in-hospital deaths per subgroup limits the power for extensive multivariable modelling. NT-proBNP values were measured only at admission, precluding assessment of dynamic changes. Prospective multicentre validation with longitudinal follow-up is warranted to confirm these findings and to determine whether serial Virtue measurements can track therapeutic response or predict post-discharge outcomes.

Despite these limitations, the present analysis provides new insight into phenotype-specific prognostication in AHF. Virtue appears to capture the integrated haemodynamic burden that drives outcomes in HFpEF, whereas in HFrEF its prognostic value is overshadowed by global systolic failure. This phenotype-dependent pattern supports a combined approach to risk stratification—one that integrates biomarkers and echocardiographic indices rather than considering them competing tools. Future research should explore whether combining Virtue with NT-proBNP or other congestion markers could enhance real-time risk assessment and optimise bedside decision-making in acute heart failure [

35,

37,

38,

39,

40].

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that the Virtue Index, a simple, integrative, echocardiographic marker reflecting the interaction between the right and left ventricles, could offer additional prognostic insight in AHF. Its performance appears to vary according to the type of dysfunction. In patients with HFpEF, the index showed a closer link with NT-proBNP levels and a better ability to identify patients at higher short-term risk, likely mirroring the combined effects of congestion and impaired ventricular coupling [

20,

32,

34,

37]. In contrast, among those with HFrEF, where global systolic failure predominates, its contribution to prognosis was more limited, and measures of forward flow such as LVOT VTI remained stronger predictors [

11,

12,

22].

Overall, the results suggest that the Virtue Index may enhance rather than replace established tools, providing an immediate, noninvasive view of haemodynamic burden at the bedside. Still, as this was a retrospective single-center study with a moderate sample size, the observations should be interpreted cautiously. Larger, prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and to clarify whether changes in the Virtue Index over time could help guide therapy and refine prognosis in AHF [

20,

36,

40].