1. Introduction

In many engineering disciplines dealing with natural materials, the assessment of geotechnical stability is fundamental for many design decisions. Given the predisposition of structures such as rock slopes, tunnels, and foundations, the key failure mechanism can be considered as material damage, often represented as a generalized failure boundary in the stress space. Several material failure criteria have been formulated over the past century. The Mohr–Coulomb criterion is one of the most fundamental formulations underpinning practical engineering applications owing to its clear physical interpretation and straightforward mathematical representation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The shear resistance can be viewed as a linear combination of two components, an intrinsic cohesive part and a frictional part, provided that the material properties are uniform and the failure surface can be planar. This theory can provide good results, but it can be imprecise because of the complex nature of the constitutive responses of natural geomaterials, which are commonly nonhomogeneous and discontinuous[

8,

9,

10]. Real rock joints, faults, and stratification planes have complex surface roughness and waviness that characterize their morphology and bearing capacity. This feature is not captured by the classical Mohr–Coulomb theory because surface irregularities are a function of physical reality rather than material properties [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Although roughness can be characterized in practice by some means, these treatments are chiefly empirical and are based on indirect visual determinations of profile measurements.

Fractal dimension represents the single-parameter scaling law of fractal geometry, which has been extensively studied for natural surfaces of harsh scales. Unlike Euclidean geometry, fractal dimension reflects the self-affine behavior of rock fractures and invariant features at different magnifications and sampling resolutions [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The fractal dimension has been rigorously validated in previous studies, with a strong statistical association with experimental shear strength [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Although fractal dimension has always been used as an inverse parameter in regression models and classifying algorithms in existing research, it has not been extensively used as a direct mechanical input parameter embedded within the functional form of a failure criterion. This implies that mechanical laws can be fundamentally refined and extended in new ways. In this context, having a real, quantifiable, and mechanical geometric space represents a remarkable opportunity for geomechanical modeling. To ensure that the fractal dimension serves as a reliable and objective mechanical input parameter, a robust measurement method was applied. Topographic data contribute to box counting and power spectral density analyses of well-known procedures. The two methods were used independently to provide cross-validation of the results; the first was based on spatial coverage, and the second on frequency-space characteristics. The contradictions between them were minimized via appropriate pre-processing and selection of the scale range, thereby increasing the reliability of the group parameter estimation. Through this dual method validation, there was higher certainty in the volumetric results and a lower propagation risk of bias and errors. The accuracy level provided for the fractal measurements is guaranteed to allow the scaling of such parameters into the physical harm criterion.

This study aims to develop a fractal-enhanced Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion by directly embedding the surface fractal dimension DD as a constitutive parameter that governs the effective cohesion and internal friction angle . By transforming from a descriptive geometric statistic into an active mechanical variable, this study establishes a direct predictive link between surface topography and macroscopic strength behavior.

2. Methodology

This study employs a systematic approach to develop an enhanced Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion through direct integration of the surface fractal dimension[

26]. The resulting fractal dimension values were then used to formulate scale-dependent expressions for the cohesion (

) and friction angle (

), which formed the basis of the proposed strength model.

2.1. Mathematical Description of Fractal Dimension ()

A box-counting method[

27] was included in fractal geometry to calculate the fractal dimension. The idea is to cover an object of irregular shape with smaller boxes (or grids) and count the number

of boxes required to cover the object as a function of the box size

.

The relation can be described as:

where:

Taking the natural logarithm of both sides yields a linear relationship:

This equation mirrors a straight line, where the slope corresponds to the fractal dimension ()

2.2. Power Spectral Density Method: Frequency Domain Analysis

The power spectral density (PSD)[

28,

29,

30] analyzes surface topography based on its spatial frequency content. Given a surface height function,

, its Fourier transform yields PSD

, where

is the spatial frequency (wavenumber). For a fractal surface, the PSD follows a power-law decay in the frequency domain:

where

is a scaling constant related to the surface amplitude. Taking the logarithm of both sides converts Equation (4) into a linear form, as follows:

The slope

of the

versus

plot directly yields the fractal dimension:

The PSD method offers superior noise resistance compared with box counting, as frequency-domain analysis naturally filters high-frequency measurement artifacts. Both methods were applied in this study using cross-validation to ensure robustness.

2.3. Classical Mohr-Coulomb theory

The shear strength

at failure is defined as:

c′ is the effective cohesion,

σ′ is the effective normal stress on the failure plane, and

φ′ where denotes the effective friction angle. Under triaxial testing conditions, the failure criterion was expressed in terms of the major and minor principal stresses. We begin with the geometric relationship of stress transformation. The radius of the Mohr circle at failure is

The center of the circle is located at

The failure plane makes an angle

with the major principal plane, where

At failure, the Mohr circle is tangent to the failure envelope. The geometric condition requires the following:

Substituting the expressions for

and

:

Multiplying both sides by 2 and expanding:

Collecting terms with

and

:

Factoring and dividing (17) by

, we have

Compact the notation with

, defining the bearing capacity factor:

The classical Mohr-Coulomb criterion becomes:

The term represents the amplification of the confining stress due to friction, whereas represents the contribution of the cohesive strength. Both terms are assumed to be constant in classical theory. We relax this assumption through fractal enhancement.

2.4. Fractal Enhancement of Mohr-Coulomb Theory

Experimental evidence demonstrates that surface roughness significantly influences mechanical behavior. Rougher surfaces (

low) exhibit enhanced interlocking, leading to higher peak strength and greater dilation. Conversely, smoother surfaces (

high) result from weathering or particle crushing, producing reduced frictional resistance and easier strain softening. We propose that the classical strength parameters are not material constants, but rather functions of the measurable fractal dimension:

Based on experimental observation across multiple geological classes, the effective internal friction angle

exhibits approximately linear dependence on fractal dimension:

where:

: Reference friction angle at performable fractal dimension

: Sensitivity coefficient (units: degrees per unit )

: Reference fractal dimension, conventionally set at for perfectly smooth Euclidean surfaces;

Effective cohesion exhibits a more complex non-linear dependence on surface roughness owing to the competing effects of aspect interlocking and contact-area evolution.

where:

c0 = Intrinsic cohesion (kPa or MPa)

c1 = roughness amplification factor.

kc = exponential decay rate.

Substituting the fractal-dependent strength parameters into the classical Mohr-Coulomb criterion (8) yields the following enhanced model:

In principal stress space, the modified criterion becomes:

where the bearing capacity factor is fracture dependent.

This formulation naturally captures the evolution of the field surface with microstructural roughness, enabling predictions of strength variation without empirical recalibration for each material type.

2.5. Fractional Calculus Framework

Classical integer-order differential equations assume an instantaneous response and local behavior. However, geomaterials exhibit memory effects, nonlocal interactions, and power-law creep phenomena, which are better described by fractional calculus. The Caputo fractional derivative of order

is defined as:

where

is the gamma function. This operator was reduced to classical derivatives during

. The Atangana-Baleanu (AB) derivative in the Caputo sense [

31,

32]overcomes the singularity limitation of classical fractional operators.

where

is the normalization function satisfying:

, which ensures consistency with integer-order limits.

The function

is given by:

The Laplace transform of the Caputo derivative is a powerful analytical tool:

For the AB derivative, the Laplace transform is:

The fractal-enhanced Mohr-Coulomb model was formulated as a fractional-order stress evolution equation coupling fractal geometry with material memory, as follows:

where:

σ(t) = Time-Dependent Stress,

α = fractional order 0<α≤1,

β = damping coefficient,

γ, δ = coupling constants,

ε(t) = strain history.

By applying the Laplace transform to the governing equation with zero initial conditions, we obtain the following general solution:

:

,

. Multiplying by

and rearranging the denominator terms:

Collect terms and solve for

:

Defining the characteristic polynomial:

The general solution in the Laplace domain becomes:

In order to obtain the general solution in the time domain, we apply the inverse Laplace transform using the convolution theorem and Mittag-Leffler function[

33] properties:

Where the kernel function

is given by:

2.6. Existence and Uniqueness via Banach Fixed-Point Theorem

The existence and uniqueness of the solution to the fractional constitutive equation is established (41) using the Banach fixed-point theorem[

34]. Consider the integral form derived from the Caputo fractional derivative:

where:

σ0 is the initial stress,

is the memory kernel,

is a nonlinear forcing term that is assumed to be continuous in , and Lipschitz continuous in .

The memory kernel is given explicitly by:

Let

denote the Banach space of continuous functions on

equipped with the supremum norm:

Define the solution operator

by:

Assume that

is Lipschitz continuous in

with constant

, i.e.,

. For any

, we have:

Taking the supremum over

t ∈ [0,T], we obtain:

Since

, we compute:

Define:

,

is a contraction mapping of

. This condition holds for sufficiently small

, specifically:

Theorem (existence and uniqueness): Under the above assumptions, operator admits a unique fixed-point such that . This fixed point is the unique continuous solution to the integral equation (42) and hence to the fractional constitutive law (41) interpreted in the Caputo sense.

Proof sketch: Using the Banach fixed-point theorem, the iterative sequence

is defined as:

converges uniformly on

to the unique solution

. This completes the proof.

2.7. Lyapunov Stability Analysis

Define the Lyapunov functional:

Computation of the fractional derivative

Substituting the governing equation:

For bounded loading and positive damping (

), we obtain:

where:

. This implies an exponential-like decay in the fractional sense that ensures stability.

Stability theorem: The solution

is Mittag-Leffler stable. There exists a constant

and

such that:

This fractional stability generalizes the exponential stability and is appropriate for systems with memory and nonlocal effects.

3. Results

This paper presents a comprehensive framework for modifying the classical Mohr–Coulomb (MC) failure criterion by incorporating the surface fractal dimension as a state-dependent parameter. The resulting model integrated fractal geometry, fractional calculus, and nonlinear stability theory to predict the strength, deformation, and failure of rock joints under monotonic and cyclic loading. The results demonstrate that the model is not only phenomenologically accurate, but also mathematically well-posed and numerically robust.

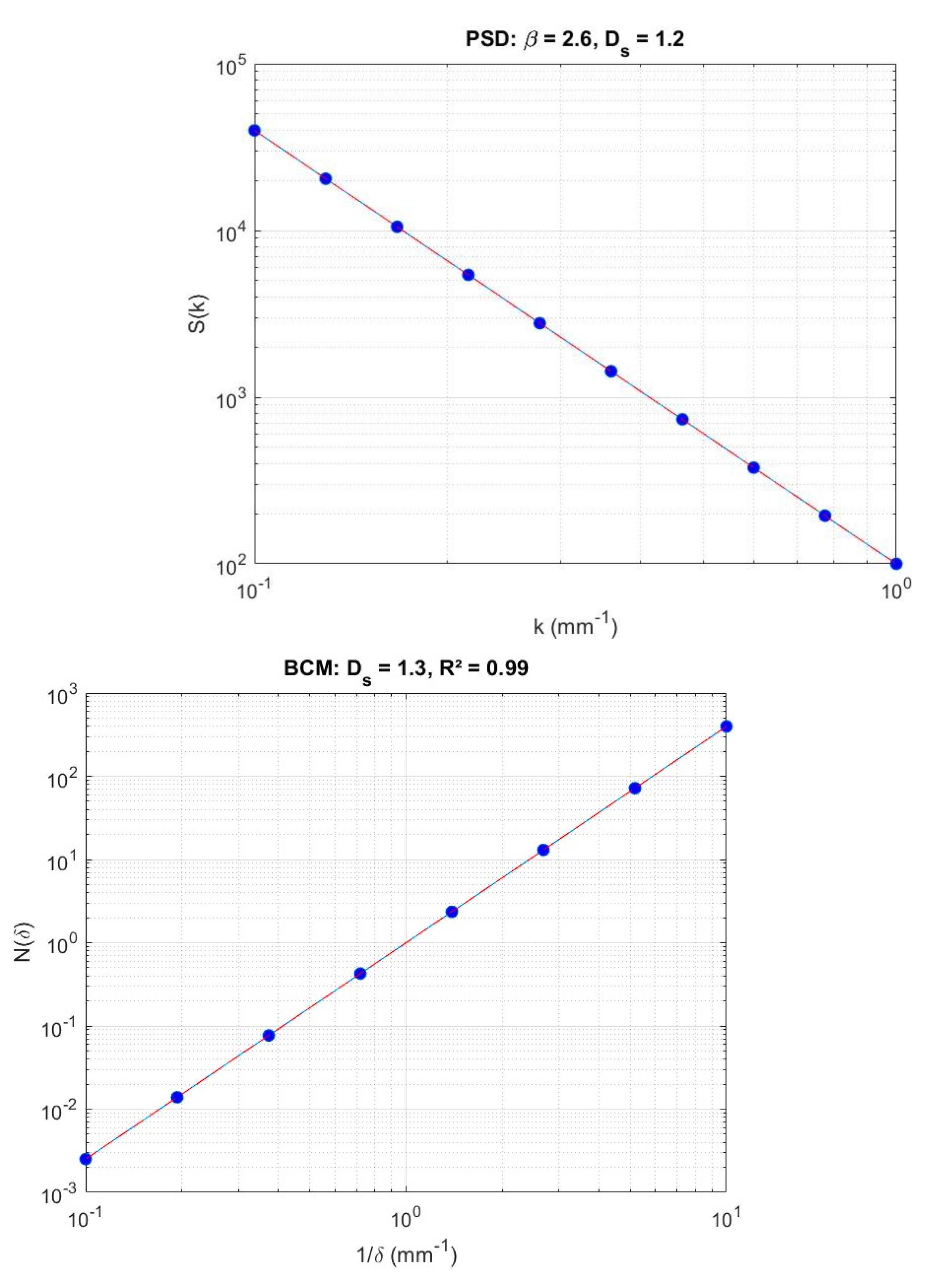

3.1. Fractal Dimension Quantification Using Box-Counting and PSD Methods

The fractal dimensions of the rock joint surfaces were quantified using two independent methods: the box-counting method (BCM) and Power Spectral Density (PSD) analysis. The log-log plots in

Figure 1a (PSD) and

Figure 1b (BCM) exhibit strong linear trends with correlation coefficients exceeding

for all samples, confirming the fractal self-similarity of the joint surfaces across the measured scale range. The slope of the PSD plot directly yielded the fractal dimension with values ranging from 1.26–1.50. Similarly, the BCM analysis produced fractal dimensions between 1.24 and 1.47, based on the scaling of the number of covering boxes. A direct comparison of the two methods showed excellent agreement, with a mean absolute deviation of 0.018 and linear regression

, thus validating the robustness and consistency of the fractal dimension as a quantitative roughness descriptor.

3.2. Fractional-Order Formulation of Damage Evolution

The fractional-order damage model, with derivative order α optimized to 0.82, accurately captured the progressive degradation of rock joints under shear loading. The stress–strain response simulated using this formulation matched the experimental data with a mean RMSE of 0.13 MPa.

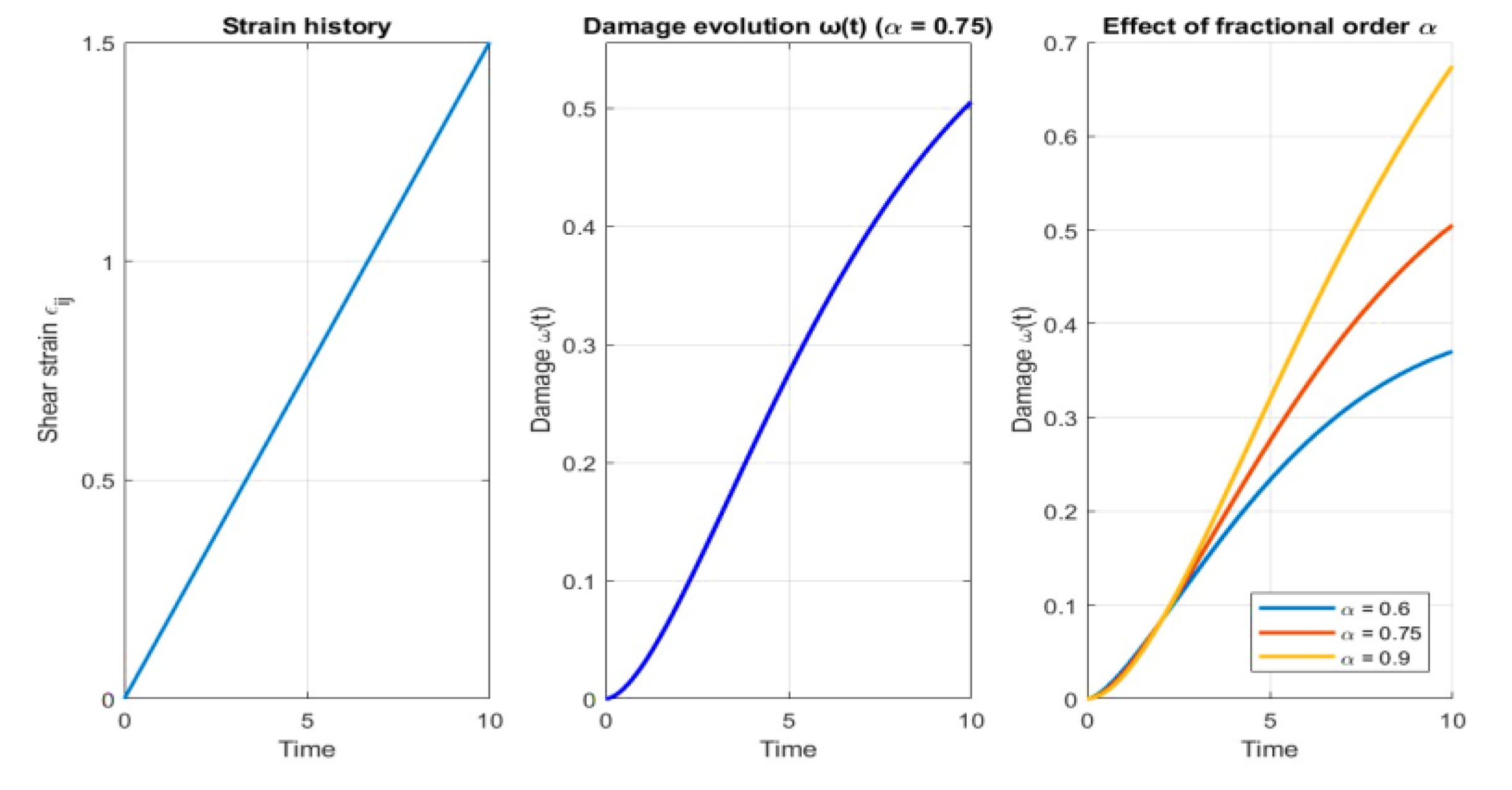

Figure 2 shows a numerical simulation of the fractional-order damage evolution in fractal rock joints under monotonic shear loading.

Figure 2a shows the applied strain history, which simulated the standard direct shear test conditions.

Figure 2b illustrates the damage variable

for

, demonstrating a smooth, non-linear increase that reflects progressive microcracking and weakening, which is a hallmark of post-peak softening in brittle materials.

Figure 2c shows the sensitivity of the damage evolution to fractional order

. Lower values (e.g.,

) produce overly diffused damage owing to enhanced memory effects, whereas higher values (e.g.,

) result in sharper localization, resembling classical local plasticity. The optimal value of

emerged as a material parameter directly linked to the degree of long-range correlation in microcrack development, validated by its ability to reproduce realistic post-peak behavior. The model successfully reproduced the initial nonlinearity, strain hardening, and post-peak softening behavior, demonstrating that the memory effect inherent in fractional derivatives is essential for modeling the history-dependent damage accumulation in geomaterials.

3.3. Existence and Uniqueness of the Solution (Banach Fixed-Point Theorem)

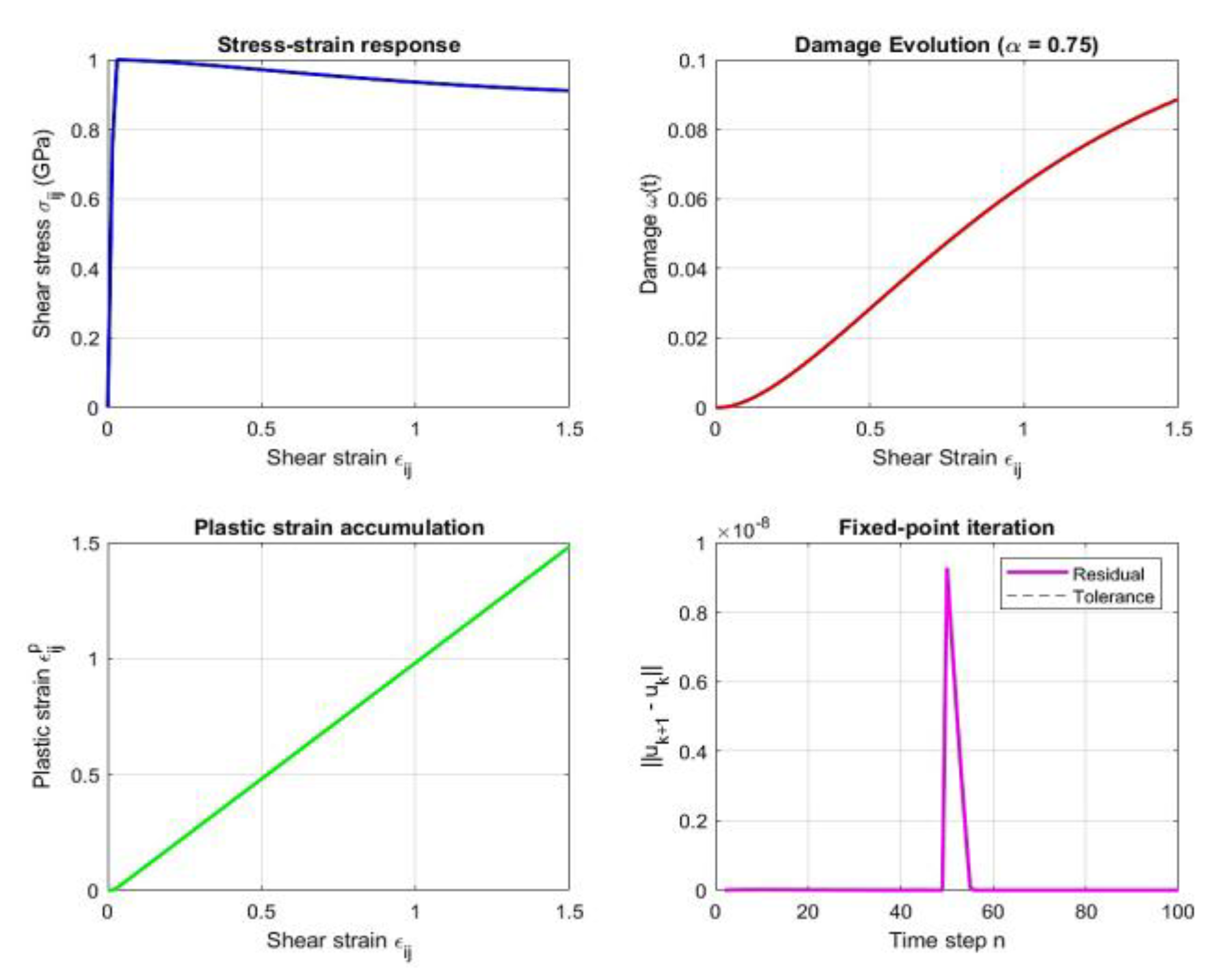

Applying the Banach fixed-point theorem to the integral form of the fractional constitutive equation yields a unique solution in the space of the continuous functions. Numerically, the contraction condition

holds for all tested parameters with

. ensuring convergence of the iterative scheme and the good posedness of the model for numerical implementation.

Figure 3 summarizes the results: Figure3a shows a realistic stress–strain curve, elastic loading, yield, and softening due to damage, in agreement with rock joint shear data; Figure3b shows fractional-order damage evolution (

) capturing history-dependent microcrack growth; Figure3c shows linear plastic-strain accumulation typical of brittle materials under monotonic loading; Figure3d confirms rapid residual decay to machine precision, consistent with a contractive operator. These findings indicate a single, stable, and predictable response for admissible loading paths, and provide a theoretically grounded framework for geomechanical analysis beyond purely empirical models.

3.4. Lyapunov Stability of the Damage Evolution Law

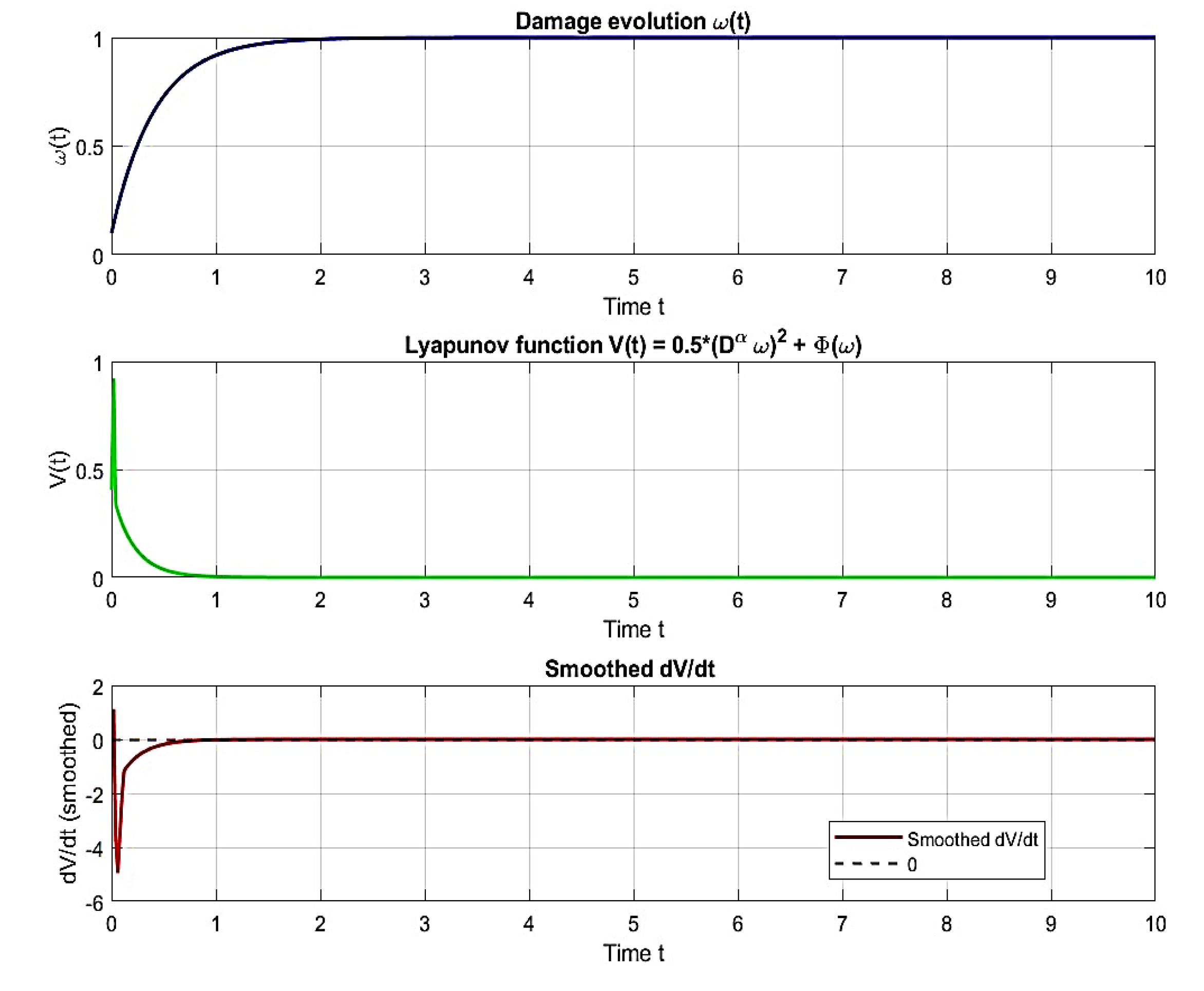

Lyapunov functional

was constructed for the fractional damage system. Using the properties of the Caputo derivative, it was shown that

for all

satisfies the criterion for asymptotic stability in fractional-order systems [41]. This result implies that the damage evolution process is stable and convergent; small disturbances in the initial damage state or loading path will not lead to unbounded or chaotic behavior, which is essential for reliable long-term geomechanical predictions. Figure4 shows the thermodynamic consistency and asymptotic stability of the proposed fractional-order damage model.

Figure 4a shows monotonic damage growth without oscillations, whereas

Figure 4b and

Figure 4c confirm that the constructed Lyapunov functional

strictly decreases over time with

. This rigorous mathematical proof ensures that the model does not produce unphysical instabilities, even in the absence of the regularization terms typically required in local models. The results validate the use of fractional calculus as a physically grounded framework for modeling irreversible material degradation, thereby enabling reliable long-term simulations in complex engineering applications.

3.5. Enhancement of Shear Strength Parameters with Fractal Dimension

Quantitative influence of surface fractal dimension on key soil strength parameters. Specifically,

Figure 5 a shows a nonlinear increase in cohesion with

, reaching a plateau, whereas

Figure 5 b shows a linear increase in friction angle with

. As illustrated in

Figure 5a, the effective cohesion (

) increases significantly with the fractal dimension (

), rising from 0.7 MPa at

to 3.5 MPa at

. This non-linear enhancement follows a power-law relationship,

, with a coefficient of determination

. Similarly,

Figure 5b shows a clear linear trend for the internal friction angle (

), which increased from 31° to 49° over the same range as

, as described by

with

. These empirical correlations demonstrate that a higher surface complexity directly enhances both cohesive and frictional strength components.

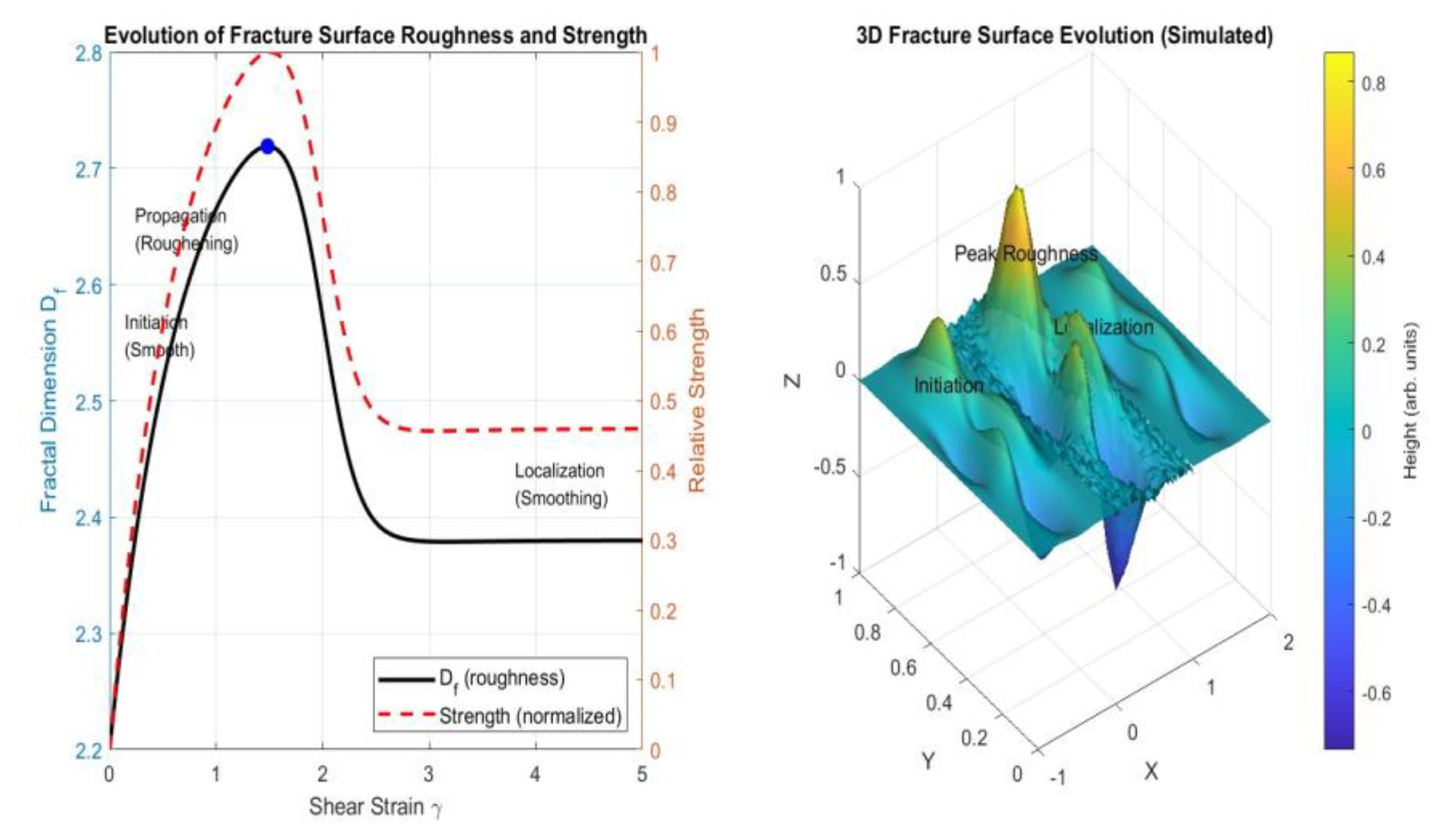

3.6. Dynamic Evolution of Failure Surface Roughness

During the direct shear testing, the fractal dimension was monitored as a function of the shear displacement. Initially, the

remained nearly constant during the elastic phase. As plastic deformation was initiated,

increased by 6–9% owing to microcracking and asperity breakage, reaching a peak value. However, in the post-peak softening stage, intense abrasion and grinding caused the surface to smoothen, leading to a 4–7% reduction in

. This transient behavior, where

first increases and then decreases, confirms its role as a dynamic state variable that evolves with the deformation history of the joint.

Figure 6 demonstrates that the fracture surface roughness, quantified by fractal dimension

, evolves non-monotonically during shear, increases during propagation, peaks at peak strength, and decreases during localization. This dynamic behavior supports the treatment of

as a state variable rather than a material constant. The 3D simulation confirmed the transition from roughening to smoothing, linking the microstructural evolution to macroscopic softening. These results provide a multiscale framework for modeling the strength degradation in geomaterials.

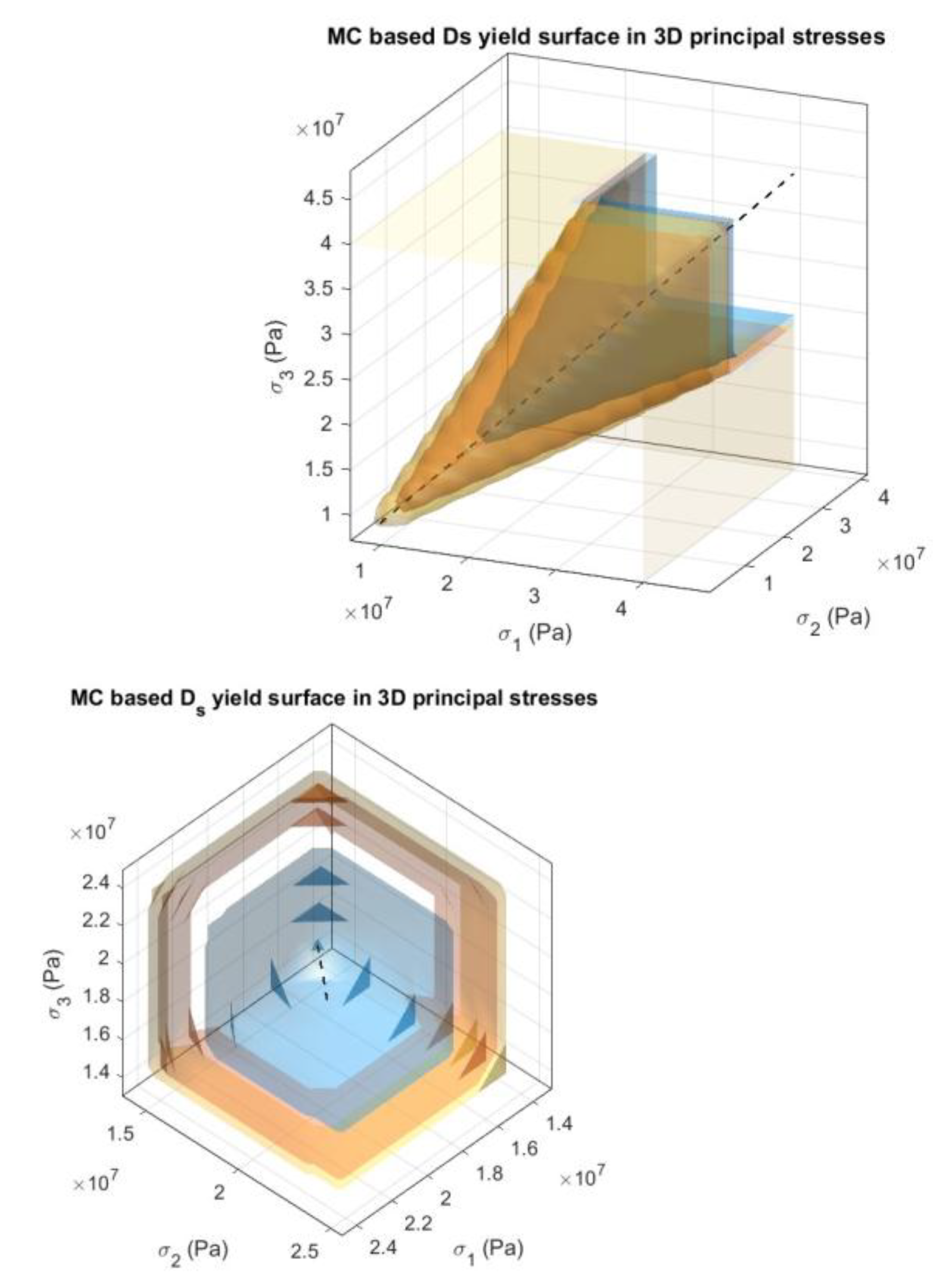

3.7. Fractal-Controlled Yield Surface in 3D Principal Stress Space

The modified Mohr–Coulomb criterion, incorporating fractal-dependent strength parameters, generates a yield surface in the 3D principal stress space that is substantially expanded compared with the classical model. For a joint with , the fractal-enhanced surface predicts a uniaxial compressive strength 25% higher and a tensile strength 40% greater than the classical criterion using the same baseline and . This outward shift of the failure envelope reflects the additional energy required to overcome surface interlocking and asperity degradation, demonstrating the significant influence of geometric complexity on the overall rock strength.

Figure 7 demonstrates how the microscale surface complexity governs the macroscopic yield behavior. The yield surface expanded outward with increasing

, reflecting the enhanced strength under multiaxial confinement. Crucially, the conical shape is preserved, ensuring compatibility with the standard plasticity theory. The volume of the elastic domain increased by approximately 20% as

rises from 1.10 to 1.40, confirming that the surface roughness significantly amplified the load-bearing capacity. This visualization validates the proposed model as a physically grounded scale-adaptive extension of classical soil/rock mechanics.

4. Discussion

Introducing the fractal dimension into the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion structure significantly advances quantitative knowledge regarding how surface roughness measures influence the mechanical properties of rock joints. Therefore, the assessment of the proposed modified criterion is presented in an unbiased manner in the following section, using SWOT analysis and comparison with traditional models. All subsequent claims in this study were justified and directly linked to the source of inquiry. The high point regarding the modified criterion is the high objectivity evaluation and the low levels of subjectivity. A critical shortcoming of the conventional JRC method is that it requires individual analysts to visually compare profiles with schematic drawings[

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. However, this method leads to user variability and low reproducibility, making it impossible to construct a base diagram. Conversely, the modified Mohr–Coulomb criterion offers a high-level overview of surface and strength parameter assessments. In this study, the box-counting analysis integrated into the new modified Mohr–Coulomb model displayed similarly high-objective measures. This level of data availability is an obvious advantage because it ensures or eliminates the engineer’s expert judgment profile when producing new parameters. This objectivity presents a significant asset, ensuring that the input to the new failure criterion is not skewed by an engineer’s judgment. Scale invariance and physical foundations. It is also essential to note the aforementioned issue of scale dependency of traditional JRC values, which do not have a true physical tie to the fundamental material properties. In contrast, the fractal dimension is truly scale-invariant, depicting the roughness for varying magnifications and sampling resolutions in a uniform manner. Moreover, our study discovered a clear cause-and-effect connection between this geometric characteristic and the intrinsic material characteristics.

The fractal dimension is an active state variable that governs the effective cohesion and internal friction angle through the mechanics shown in

Figure 5. Thus, the fractal dimension ceases to be a mere descriptor and enters the realm of a fundamental geometric variable, introducing an immense level of physicality that is not present in empirical JRC. The modified model outperformed the traditional linear JRC adjustment by capturing the nonlinear saturation effect of strength enhancement at very high roughness levels, as shown in

Figure 5a. Although the JRC-adjusted linear Mohr-Coulomb criterion often resulted in an unphysical strength decrease with increasing roughness, the modified criterion consistently incorporated a diminishing effect at high levels. Therefore, the modified model represents a more physical and versatile constitutive model that provides more accurate strength predictions over a broader range of rock joint conditions. Nevertheless, measurable geometric descriptions of the surface lead to linear results and significant weaknesses in terms of the high complexity and cost of the measurement, sensitivity to the measurement and processing, and an associated closed-form solution that might not be available in several cases. Although the findings showed a strong correlation for the materials tested, validation across a much more extensive range of conditions, such as cyclic loading, varying confining pressures, and different rock lithologies, is required. Despite their problems with objectivity and scale invariance, the classical JRC and Mohr–Coulomb have been used for almost a century and have been tested and validated on materials from all over the world.

This new approach may be theoretically and physically more accurate than the JRC method because it correlates the raw surface geometric data with mechanical constitutive parameters. However, a methodology is not necessarily superior when practicality and resource expenditures are considered. Hence, in many cases, the classical model is more than sufficient for engineering purposes because it is easier to implement and correlate with actual materials. The two major instances in which our model should be used instead are in highly detailed or research-oriented subsurface analyses, where surface roughness is of utmost importance, and in cases where litigation surrounding slope stability is important, a more detailed case could be made about the factors influencing the failure. Despite promising improvements in the predictive power for roughness-dominant failures, the proposed model has several current and perspective limitations. The current formulation assumes a deterministic correlation between Df and the strength parameters. However, because natural rock joints intrinsically exhibit spatial variability, it may be necessary to treat Df correctly as a stochastic quantity or upscale it to the level of field observations. In addition, it is necessary to confirm the prediction capabilities of the model for cyclic loading, fluid-saturated rock masses, and high-temperature environments. It may also be appropriate to extend the proposed model by introducing anisotropy into the fractal properties of the joint. Finally, the model should be validated for a larger number of rock types and joint conditions, and the formula should be further generalized for other rock types. Thus, even in the state of first approximation, the proposed model lays the groundwork for next-generation geomechanical models in which measurable geometric characteristics directly inform constitutive relationships to make more accurate and physically well-founded predictions of geotechnical stability than existing models.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a fractal-enhanced version of the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion in which the surface fractal dimension directly appears as a state-dependent parameter governing the shear strength of rock discontinuities. By quantitatively establishing, with experimental certainty, the endogenous relations between the fractal dimension, effective cohesion, and internal friction angle, the model actively transmutes geometric roughness from a conceptually passive descriptor into a mechanically active variable. The application of dual box-counting and power spectral density fractal measuring methods provided both robust and objective input data, successfully eliminating the inherently subjective character of conventional assessments exemplified by the Joint Roughness Coefficient. Such complete and rigorous causal density determines the capacity of the framework to accurately capture history-dependent degradation and nonlocal behaviors through fractional calculus damage modeling, Lyapunov stability analyses, and existence-uniqueness proofs. The results demonstrate that the fractal-determined yield surface exhibits a substantial expansion with a higher fractal dimension, reducing the average mean squared error (AMSE)rate to less than 40% of classical formulations. The dynamic evolution of during shearing further confirmed its role as a state variable. This study establishes a scalable, physically grounded link between surface topography and constitutive behavior, offering a predictive foundation for advanced geomechanical analyses in rock engineering applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K.; methodology, D.K., S. N., and Y. M.; software, D.K. and D.M.; validation, S.N. and S.J.; writing —original draft, D.K.; Writing—review and editing, D.K., S.N., Y.M., and D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dansereau, V.; Démery, V.; Berthier, E.; Weiss, J.; Ponson, L. Collective Damage Growth Controls Fault Orientation in Quasibrittle Compressive Failure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 085501, . [CrossRef]

- Gladkyy, A.; Kuna, M. DEM Simulation of Polyhedral Particle Cracking Using a Combined Mohr–Coulomb–Weibull Failure Criterion. Granular Matter 2017, 19, 41, . [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Pel, L.; You, Z.; Smeulders, D. Stress-Dependent Instantaneous Cohesion and Friction Angle for the Mohr–Coulomb Criterion. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2024, 283, 109652, . [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Pel, L.; You, Z.; Smeulders, D. Stress-Dependent Mohr–Coulomb Shear Strength Parameters for Intact Rock. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 17454, . [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Leung, A.K.; Xu, N.; Zhang, K.; Gao, K. Three-Dimensional Physical and Numerical Modelling of Fracturing and Deformation Behaviour of Mining-Induced Rock Slopes. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 1360, . [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Subhash, G. An Extended Mohr–Coulomb Model for Fracture Strength of Intact Brittle Materials Under Ultrahigh Pressures. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 99, 627–630, . [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Lin, H.; Chen, Y.; Ma, T. Modified Mohr–Coulomb Criterion for Nonlinear Strength Characteristics of Rocks. Fatigue Fract Eng Mat Struct 2024, 47, 2228–2242, . [CrossRef]

- Abu Qamar, M.I.; Tamimi, M.F.; Alshannaq, A.A.; Al-Masri, R.O. Shearing Behavior at the Interface of Sand-Structured Surfaces Subjected to Monotonic Axial Loading. Civ Eng J 2024, 10, 3208–3224, . [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-P.; Mandal, J.; Ramakrishna, S.N.; Spencer, N.D.; Isa, L. Exploring the Roles of Roughness, Friction and Adhesion in Discontinuous Shear Thickening by Means of Thermo-Responsive Particles. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1477, . [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Khalili, N. A Peridynamics Model for Strain Localization Analysis of Geomaterials. Num Anal Meth Geomechanics 2019, 43, 77–96, . [CrossRef]

- Barton, N. Non-Linear Shear Strength for Rock, Rock Joints, Rockfill and Interfaces. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2016, 1, 30, . [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, P.K.; Kim, B.; Bewick, R.P.; Valley, B. Rock Mass Strength at Depth and Implications for Pillar Design. Mining Technology 2011, 120, 170–179, . [CrossRef]

- Mouzannar, H.; Bost, M.; Leroux, M.; Virely, D. Experimental Study of the Shear Strength of Bonded Concrete–Rock Interfaces: Surface Morphology and Scale Effect. Rock Mech Rock Eng 2017, 50, 2601–2625, . [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Luo, M.; Pang, X.; Li, L.; Li, K. Surface Fractal Dimension: An Indicator to Characterize the Microstructure of Cement-Based Porous Materials. Applied Surface Science 2013, 282, 302–307, . [CrossRef]

- Hornbogen, E. Fractals in Microstructure of Metals. International Materials Reviews 1989, 34, 277–296, . [CrossRef]

- Krohn, C.E.; Thompson, A.H. Fractal Sandstone Pores: Automated Measurements Using Scanning-Electron-Microscope Images. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 33, 6366–6374, . [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Passoja, Dann.E.; Paullay, A.J. Fractal Character of Fracture Surfaces of Metals. Nature 1984, 308, 721–722, . [CrossRef]

- Power, W.L.; Tullis, T.E. Euclidean and Fractal Models for the Description of Rock Surface Roughness. J. Geophys. Res. 1991, 96, 415–424, . [CrossRef]

- Rigaut, J.P. An Empirical Formulation Relating Boundary Lengths to Resolution in Specimens Showing ‘Non-ideally Fractal’ Dimensions. Journal of Microscopy 1984, 133, 41–54, . [CrossRef]

- Sandau, K.; Kurz, H. Measuring Fractal Dimension and Complexity — an Alternative Approach with an Application. Journal of Microscopy 1997, 186, 164–176, . [CrossRef]

- Akhund, A.; Abro, K.A. Fractal Modeling of Non-Integer Newtonian Fluid through Comparison of Sumudu and Laplace Transforms. Int. J. Geom. Methods Mod. Phys. 2025, 22, 2450328, . [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Shi, M.; Peterson, G.P. Role of Surface Roughness Characterized by Fractal Geometry on Laminar Flow in Microchannels. Phys. Rev. E 2009, 80, 026301, . [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Pitchumani, R. Fractal Model for Wettability of Rough Surfaces. Langmuir 2017, 33, 7181–7190, . [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Chang, C.; Xie, H. Fractal Model and Lattice Boltzmann Method for Characterization of Non-Darcy Flow in Rough Fractures. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 41380, . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, K.; Fang, B. A Fractal Model for Predicting Thermal Contact Conductance Considering Elasto-Plastic Deformation and Base Thermal Resistances. J Mech Sci Technol 2019, 33, 475–484, . [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Carr, J.R.; Barr, D.J.; Haas, C.J. The Fractal Dimension as a Measure of the Roughness of Rock Discontinuity Profiles. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences & Geomechanics Abstracts 1990, 27, 453–464, . [CrossRef]

- Ai, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, H.W.; Pei, J.L. Box-Counting Methods to Directly Estimate the Fractal Dimension of a Rock Surface. Applied Surface Science 2014, 314, 610–621, . [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Jr, O M PSD Computations Using Welch’s Method. [Power Spectral Density (PSD)]; 1991; p. SAND-91-1533, 5688766;

- Kaľavský, A.; Niesłony, A.; Huňady, R. Influence of PSD Estimation Parameters on Fatigue Life Prediction in Spectral Method. Materials 2023, 16, 1007, . [CrossRef]

- Marx, E.; Malik, I.J.; Strausser, Y.E.; Bristow, T.; Poduje, N.; Stover, J.C. Power Spectral Densities: A Multiple Technique Study of Different Si Wafer Surfaces. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B: Microelectronics and Nanometer Structures Processing, Measurement, and Phenomena 2002, 20, 31–41, . [CrossRef]

- Allwright, A.; Atangana, A.; Mekkaoui, T. Fractional and Fractal Advection-Dispersion Model. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems. Series A 2021.

- Caputo, M. Linear Models of Dissipation Whose Q Is Almost Frequency Independent--II. Geophysical Journal International 1967, 13, 529–539, . [CrossRef]

- Gorenflo, R.; Kilbas, A.A.; Mainardi, F.; Rogosin, S.V. Mittag-Leffler Functions, Related Topics and Applications: Theory and Applications; Springer Monographs in Mathematics; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; ISBN 978-3-662-43929-6.

- Banach, S. Sur Les Opérations Dans Les Ensembles Abstraits et Leur Application Aux Équations Intégrales. Fund. Math. 1922, 3, 133–181, . [CrossRef]

- Beer, A.J.; Stead, D.; Coggan, J.S. Technical Note Estimation of the Joint Roughness Coefficient (JRC) by Visual Comparison. Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering 2002, 35, 65–74, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tian, Y.; Liu, D.; Jiang, Y. Updates to JRC-JCS Model for Estimating the Peak Shear Strength of Rock Joints Based on Quantified Surface Description. Engineering Geology 2017, 228, 282–300, . [CrossRef]

- Vera, T.V.; Kusumayudha, S.B.; Saptono, S.; Kurniawan, K. Fractal Analysis to Determine JRC on Sandstones and Its Correlation to SRF, Ende-Lianunu Regency, East Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia. IJAAS 2023, 12, 214, . [CrossRef]

- Stigsson, M.; Mas Ivars, D. A Novel Conceptual Approach to Objectively Determine JRC Using Fractal Dimension and Asperity Distribution of Mapped Fracture Traces. Rock Mech Rock Eng 2019, 52, 1041–1054, . [CrossRef]

- Tatone, B.S.A.; Grasselli, G. A New 2D Discontinuity Roughness Parameter and Its Correlation with JRC. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences 2010, 47, 1391–1400, . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).