1. Introduction

Currently, energy issues constitute a critical concern for socio-economic development and command significant international attention. This prominence stems from three primary challenges associated with fossil fuel dependence. Firstly, fossil fuel combustion drives substantial CO₂ emissions, exacerbating global warming. In response, China announced ambitious targets at the 75th UN General Assembly (2020) to peak CO₂ emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 [

1], reaffirming its commitment to green transition and the Paris Agreement at the 79th session (2024) [

2]. Renewable energy development is a scientifically sound pathway to meet these goals, mitigating climate change impacts like extreme weather and biodiversity loss. Secondly, the finite nature and uneven geopolitical distribution of fossil fuels lead to supply insecurities and price volatility, as recent global conflicts underscore, highlighting the imperative for transitioning towards resilient and sustainable energy systems to ensure energy independence and security [

3]. Thirdly, the use of fossil fuels produces harmful pollutants, resulting in severe air pollution and acid rain. Conversely, renewable energy sources generate near-zero emissions, which could significantly reduce public health issues, including an estimated five million annual deaths linked to air pollution.

In China, rapid economic growth and evolving consumption patterns have escalated energy demand, making it a major carbon emitter [

4]. The building operations sector is a crucial focus, accounting for 30% of global final energy consumption [

5]. Space heating alone represents 11% of global final energy consumption, with 63% of heat derived directly from fossil fuels [

6]. Therefore, decarbonizing heating systems is crucial for achieving carbon neutrality ambitions [

6,

7,

8].

Heating strategies in China exhibit strong regional disparities due to the historical ‘North-South Heating Divide’ policy in 1950, which limited centralized heating infrastructure largely to areas in the north of the Qinling-Huaihe line [

4,

9]. This policy aimed to conserve resources but resulted in lower winter thermal comfort, especially in the Hot Summer and Cold Winter (HSCW) zone [

10], which experiences harsh, humid winters with indoor temperatures notably 6℃ lower than in climatically similar regions like the UK [

9,

11]. In China, given the enormous building stock, the operational carbon emissions of buildings in HSCW zones reached 650 million tons of CO₂ in 2020 [

12], with rural residential buildings accounting for 20% of this total. Although traditionally classified as non-heating areas, HSCW zones experience prolonged cold and damp winters. In recent years, frequent freezing rain and snowstorms in southern China have led to record-low temperatures, significantly disrupting daily life and economic activities. As living levels improve, the demand for winter heating in these areas has become increasingly urgent [

13], resulting in a 575-fold increase in residential heating energy consumption over 15 years [

14]. However, due to distinct climatic conditions, building typologies, and lifestyle patterns, heating strategies used in northern rural areas or urban settings cannot be directly applied to southern rural China. In response, a growing number of households have adopted decentralized heating systems, which include individual household and district heating [

6]. Currently, nearly 60% of heating in the zone relies on inefficient air conditioning units[

15], leading to sharp rise in electricity consumption primarily generated from fossil fuels, thus being unable to meet the electricity supply-demand balance [

16] and indirectly generating significant carbon emissions [

5]. In addition, high operational costs also limit broader uptake [

17]. All these underscore the potential of renewable-based heating to improve economic accessibility. Therefore, analyzing household heating energy use in China’s HSCW zones and identifying suitable heating methods are critical for supporting rural revitalization and achieving the nation’s dual carbon goals.

Additionally, China has steadily amplified its support for renewable energy, with the government actively promoting “Assessment Standard for Green Building” (GB/T 50378-2019) [

18] and “Renewable Energy Law of the People’s Republic of China”. Furthermore, regional governments have rolled out energy-saving policies that encourage the utilization of solar energy not only for domestic hot water but also for space heating [

17].

China’s solar energy resources are categorized into five zones according to solar radiation levels. Most cities in the HSCW zone belong to the medium resource category (Zone III), with some falling into the low-resource tier (Zone IV) [

19]. While solar resources in the HSCW zone are less abundant relative to other parts of China, solar radiation intensity in the HSCW zone remains higher than in European nations such as Denmark, where solar heating is extensively utilized [

20]. Consequently, despite comparative disadvantages, solar heating technologies can still fulfill winter heating requirements in the HSCW zone.

However, solar thermal systems often require auxiliary heat sources due to intermittency [

21]. In the HSCW zone, electricity is commonly used for this purpose [

19] via electric heaters, blankets, or AC units, etc. However, this approach is inefficient due to the exergy degradation involved in converting high-exergy electricity to low-exergy heat, in addition to being costly and slow-responding [

22]. Gas boilers offer an alternative auxiliary source [

8], but still contribute to CO₂ emissions. Comparative research indicates that Solar Air Source Heat Pump (SASHP) systems achieve significantly higher exergy efficiency (2-3 times) than solar-gas boiler systems [

23]. By leveraging dual heat sources [

24] and enabling multi-energy synergy [

25], SASHP systems are especially suitable for the HSCW zone, where winter temperatures are moderate (0–10 °C). This configuration reduces frosting risks [

26] and outperforms conventional Air Source Heat Pumps (ASHPs). Notably, SASHP systems have been deployed across multiple global applications [

27]. For enhancing the system’s reliability, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness, the inherent challenges of solar intermittency and declining ASHP performance at lower temperatures can be mitigated by integrating thermal energy storage (TES) technologies, such as water storage tanks [

21], phase change materials or sand-based floors [

28]. Among these, the water storage tank, which is a widespread solution for sensible heat storage, has been demonstrated to substantially improve the system’s Coefficient of Performance (COP) [

29]. Additionally, the size of the storage tank is a critical factor influencing energy efficiency, solar fraction, and overall energy consumption [

21].

Above all, this study aims to provide a theoretical foundation for enhancing the energy efficiency of solar heating systems in rural residential buildings in China’s HSCW zone. Its findings are intended to support the widespread adoption of distributed solar heating technology, contributing significantly to the energy conservation and the facilitation of carbon neutrality goals. Thus, in

Section 2, the building model and heat load are developed. Later,

Section 3 introduces the design scheme of the SASHP heating system referencing to the standards in China. Subsequently, in

Section 4, the performances of the optimized SASHP heating system are analyzed and compared with the results corresponding to the design proposal. Finally,

Section 5 concludes this study.

4. Optimization of the SASHP System

GenOpt, which is developed on the Java platform, couples with TRNSYS simulation software to address optimization challenges in complex system interactions. And the bridging interface between TRNSYS and GenOpt is the TRNOPT module, a component of the TESS library in TRNSYS. In this study, the GenOpt-TRNSYS framework employs the Hooke-Jeeves algorithm, which is known as the “pattern search method” or “step-size acceleration method” and is widely used in unconstrained optimization for non-differentiable functions.

4.1. Optimizing Configurations

The optimization objective is to minimize the annualized cost, considering four optimization variables, including collector area, rated heating capacity of the ASHP, ratio of storage tank volume to collector area, and the tilt angle of the solar collector. Afterward, the following parameters should be configured in TRNOPT: initial guess value, lower bound, upper bound, and step size for each optimization variable; selection of the annualized cost function as the target variable. To prevent temperature imbalance during optimization—where excessive focus on cost reduction might compromise heating performance—a penalty mechanism is introduced. If the storage tank temperature fails to reach 43 °C within two hours of system startup or drops below 43 °C during operation, an economic penalty is triggered. A fixed penalty of ¥5,000 per hour is added to the annualized cost for each hour of non-compliance. The significant disparity between penalty costs and normal operating expenses ensures the optimization process inherently to avoid situations below 43 °C.

where

AEC is the annual equivalent cost, ¥/year;

C0 indicates the initial investment, ¥;

i is the interest rate, which is taken as 5.66% here;

m is the service life, taken as 15 years here;

C is the annual operating cost, ¥/year, including penalty fees and power consumption fees such as ASHPs.

The initial investment

C0 includes investments in equipment such as solar collectors, ASHP, thermal storage water tanks, and water pumps. The initial investment calculation formula is as follows:

where

ASS is the area of the collector, m

2;

CSC indicates the cost per square meter of collector area, ¥/m2;

RHP represents the customized heat for ASHP, kW;

CHP denotes customized heat equipment cost per unit for ASHP, ¥/kW;

VST is the capacity of the hot water storage tank, m3;

CST represents the cost per cubic meter of a hot water storage tank, ¥/m3;

CFJ indicates the cost of the water pump, ¥.

Table 4.

System equipment price list.

Table 4.

System equipment price list.

| Device |

Unit price |

| ASHP |

=1000 yuan/kW |

| Solar collector |

=300 yuan/m2

|

| Heat storage water tank |

=600 yuan/m3

|

| Water pumps and other equipment |

CFJ = 20% of the total price of the above three devices |

The operating cost

C is the cost generated by the electricity consumption of the equipment, and its formula is as follows:

where

WHP is the power consumption of the ASHP, kWh;

WJH indicates the power consumption of the heating pump, kWh;

WCH represents the power consumption of the heat pump, kWh;

MD denotes the electricity price, shown in

Table 5.

4.2. Optimized Results

After determining the optimization variables and objective function, the initial value, minimum value, maximum value, and iteration step of the optimization variables are configured in GENOPT as shown in

Table 6.

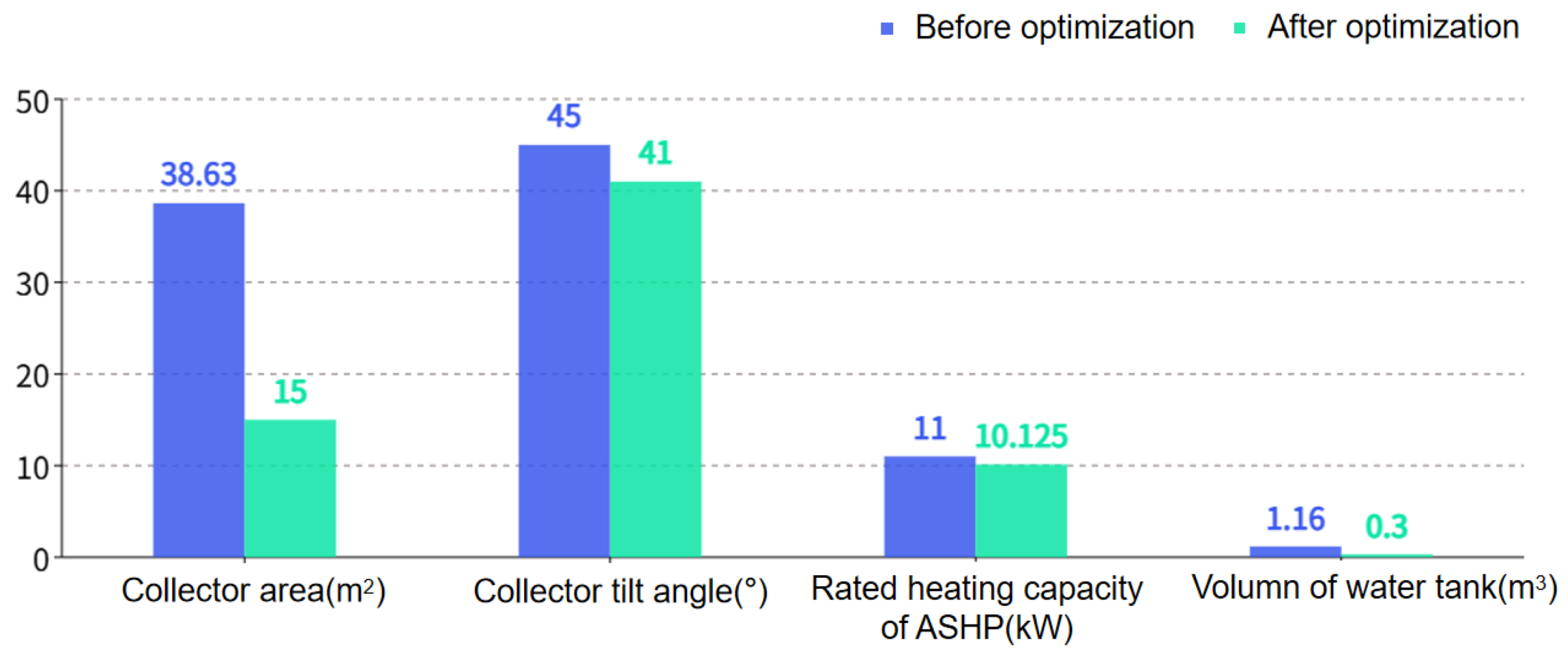

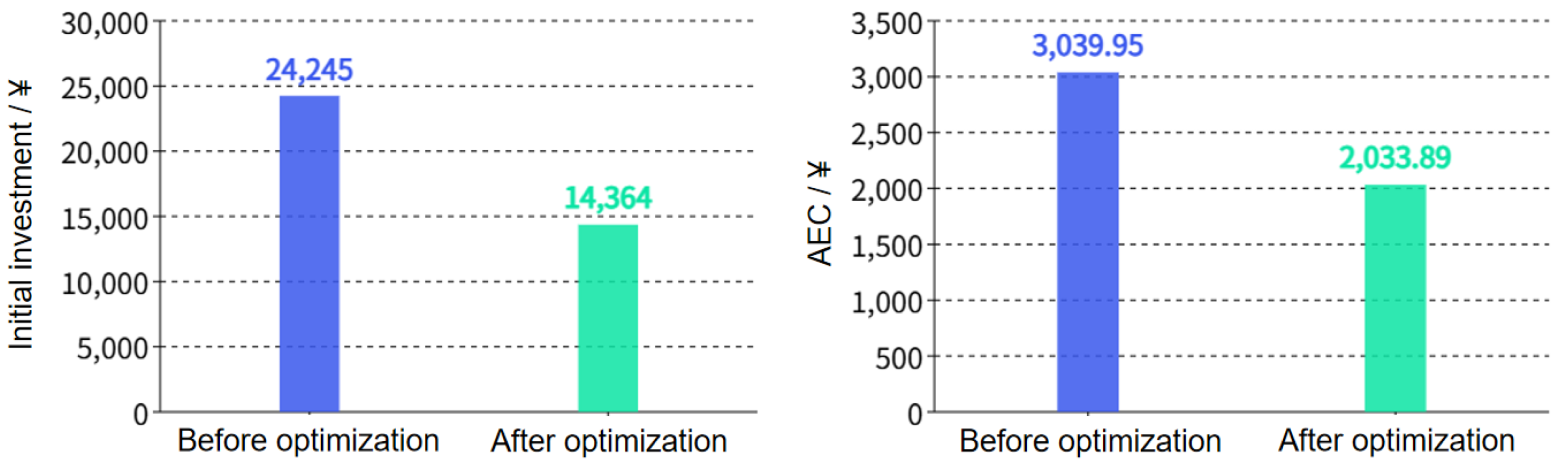

The comparisons before and after optimization are shown in

Table 7 and

Figure 15~

Figure 16. It can be seen that the optimized collector area and heat pump rated heat output have significantly decreased. After optimization, the area of the collector was decreased by 23.63, with a decrease ratio of 61.17%. As well, the tilt angle of the collector was decreased by 4, with a decrease ratio of 8.89%. According to “Technical Standards for Solar Heating and Heating Engineering” (GB50495-2019)[

35], the tilt angle of the solar collector used throughout the year should be the local latitude(30°15’ in Hangzhou) plus 10°, resulting in 40°15’, which is very close to the optimized result. And the rated heat output of the heat pump decreased by 0.875, with a decrease ratio of 7.95%; the volume of the thermal storage water tank was decreased by 0.86, with a decrease ratio of 74.14%. As a result, the initial investment was decreased by ¥9881, with a decrease ratio of 40.75%. AEC was decreased by ¥1006.06, with a decrease ratio of 33.09%. Above all, the optimized equipment parameters are more economical.

Figure 1.

3D model of the residence.

Figure 1.

3D model of the residence.

Figure 2.

Annual hourly outdoor dry bulb temperature in Hangzhou.

Figure 2.

Annual hourly outdoor dry bulb temperature in Hangzhou.

Figure 3.

Annual hourly horizontal solar radiation.

Figure 3.

Annual hourly horizontal solar radiation.

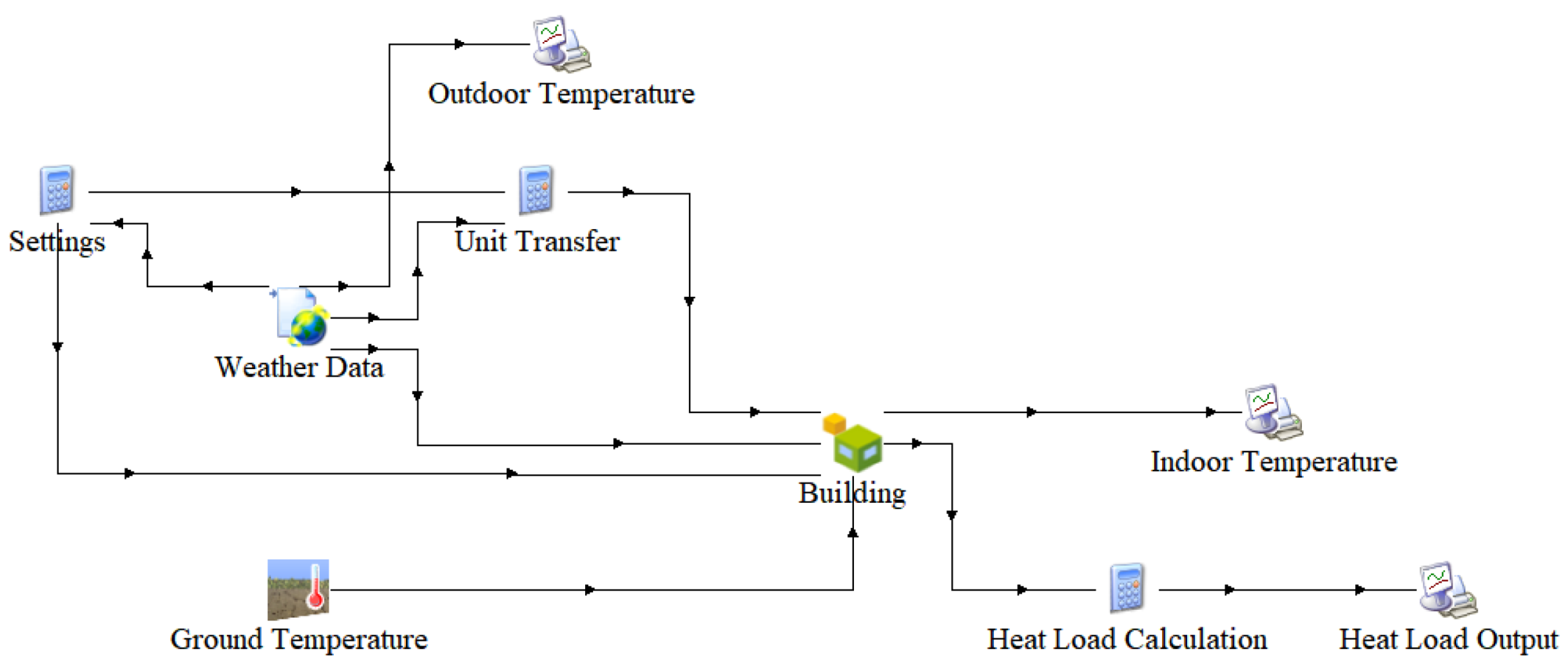

Figure 4.

Building load output model.

Figure 4.

Building load output model.

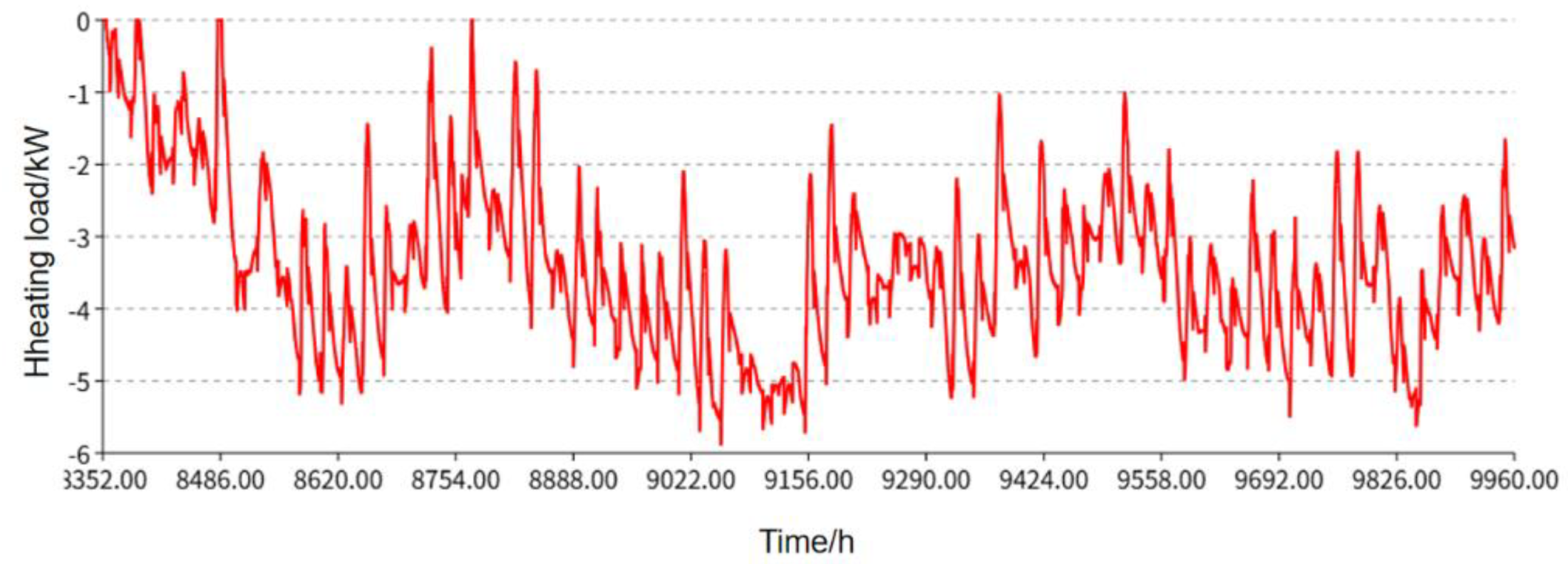

Figure 5.

Heat load output results.

Figure 5.

Heat load output results.

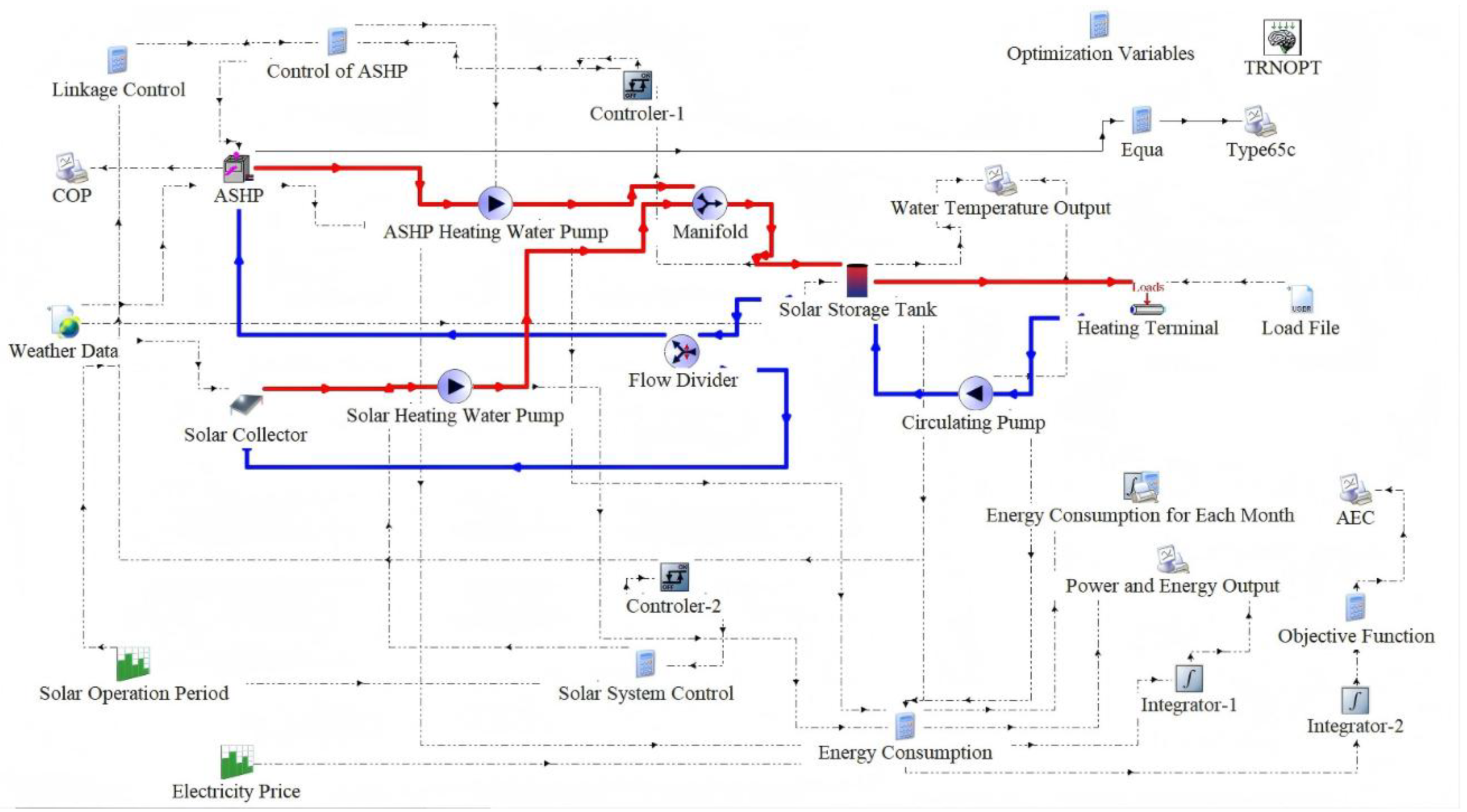

Figure 6.

Simulation model of the SASHP heating system.

Figure 6.

Simulation model of the SASHP heating system.

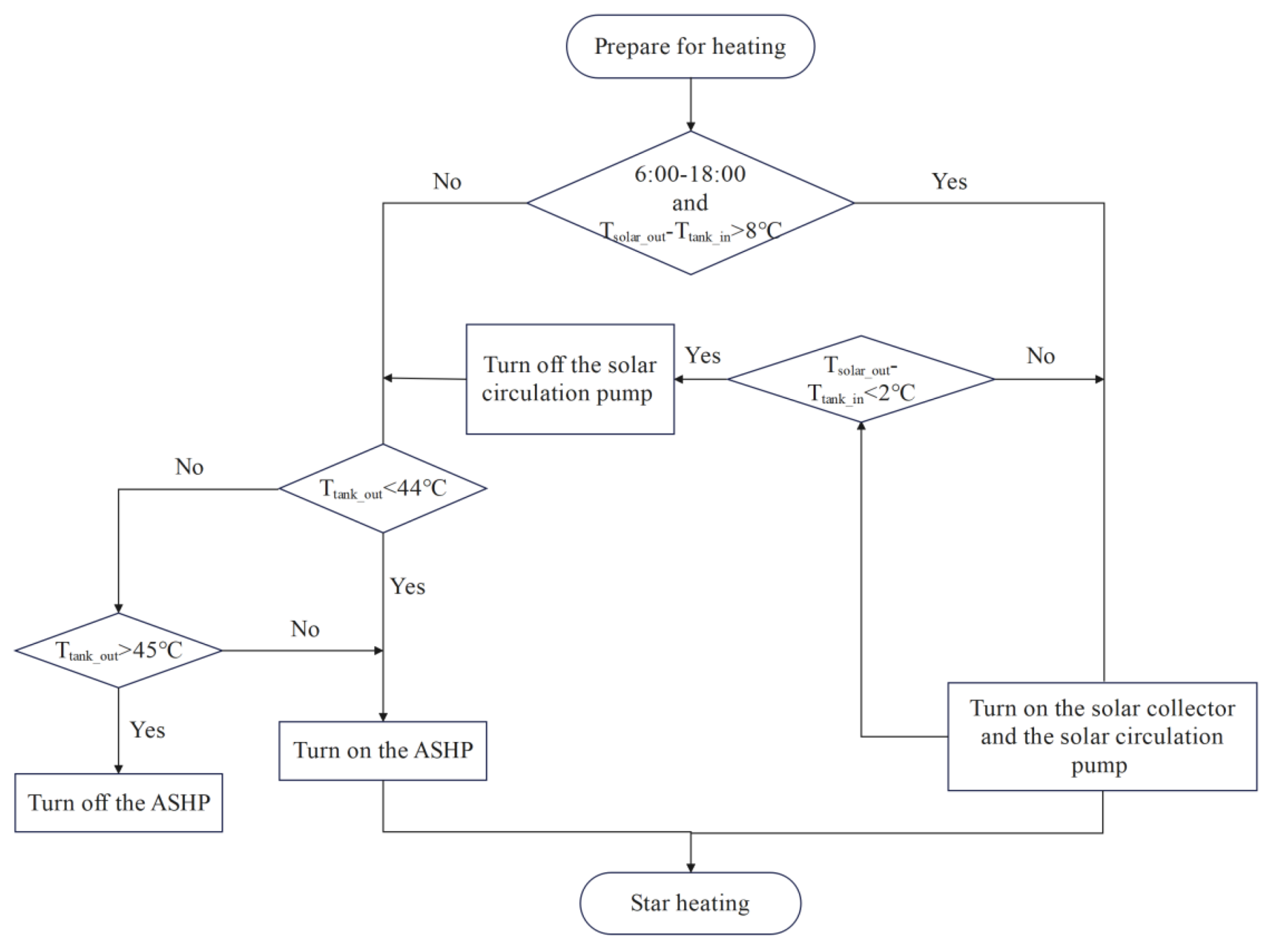

Figure 7.

Control strategy for the SASHP heating system.

Figure 7.

Control strategy for the SASHP heating system.

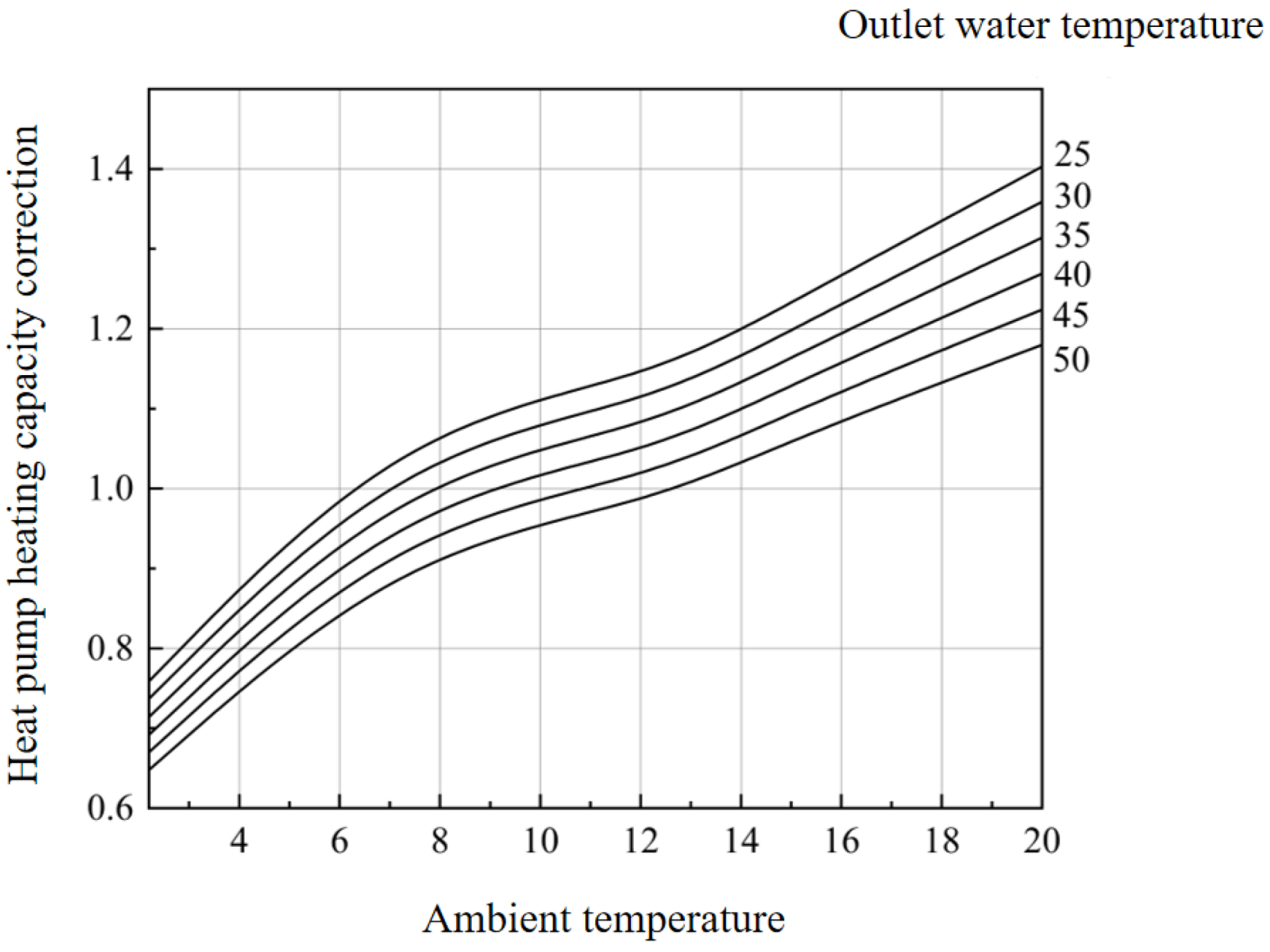

Figure 8.

Correction factor of heat pump heating capacity vs. ambient temperature and outlet water temperature.

Figure 8.

Correction factor of heat pump heating capacity vs. ambient temperature and outlet water temperature.

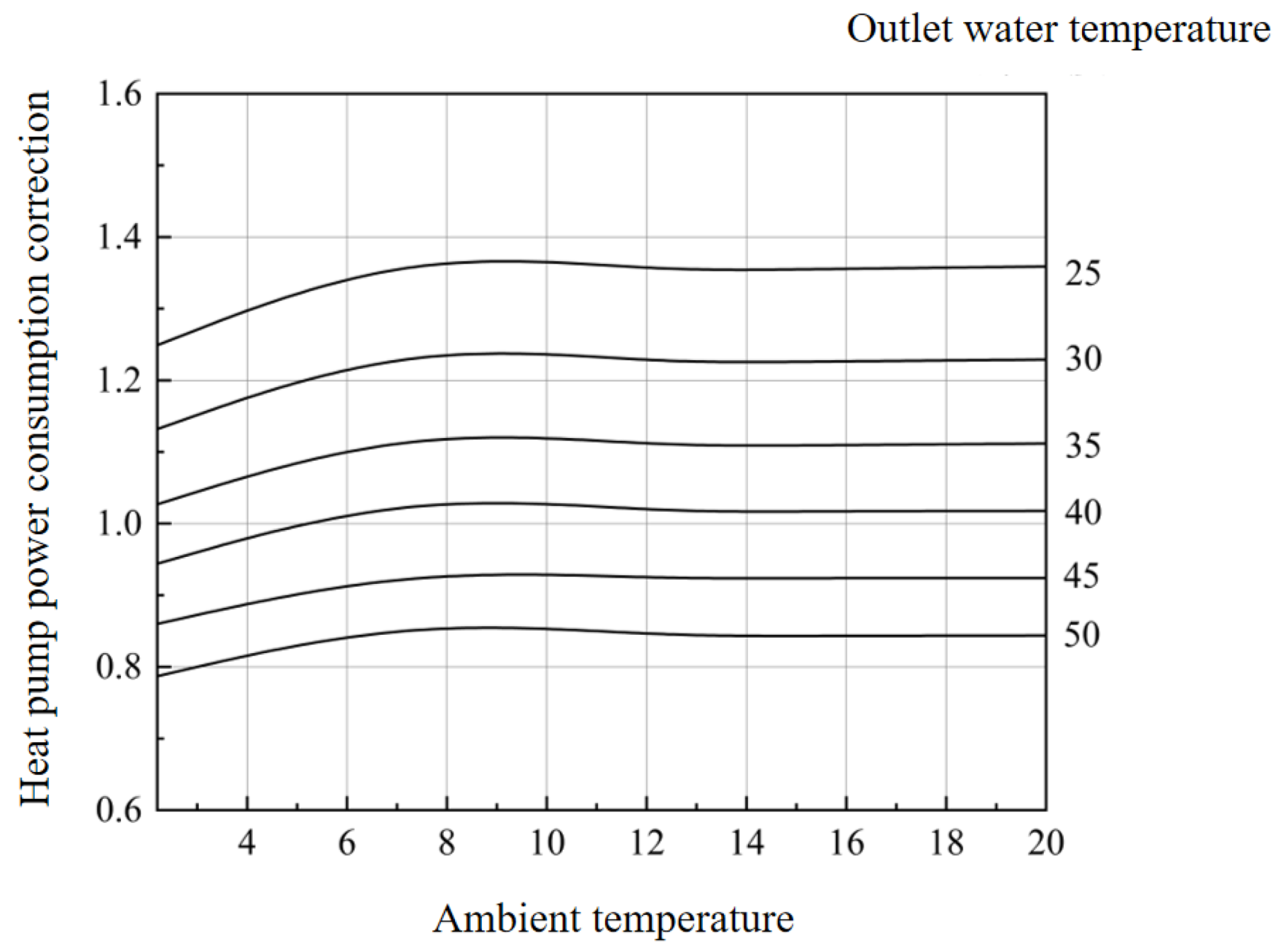

Figure 9.

Correction factor of heat pump power consumption vs. ambient temperature and outlet water temperature.

Figure 9.

Correction factor of heat pump power consumption vs. ambient temperature and outlet water temperature.

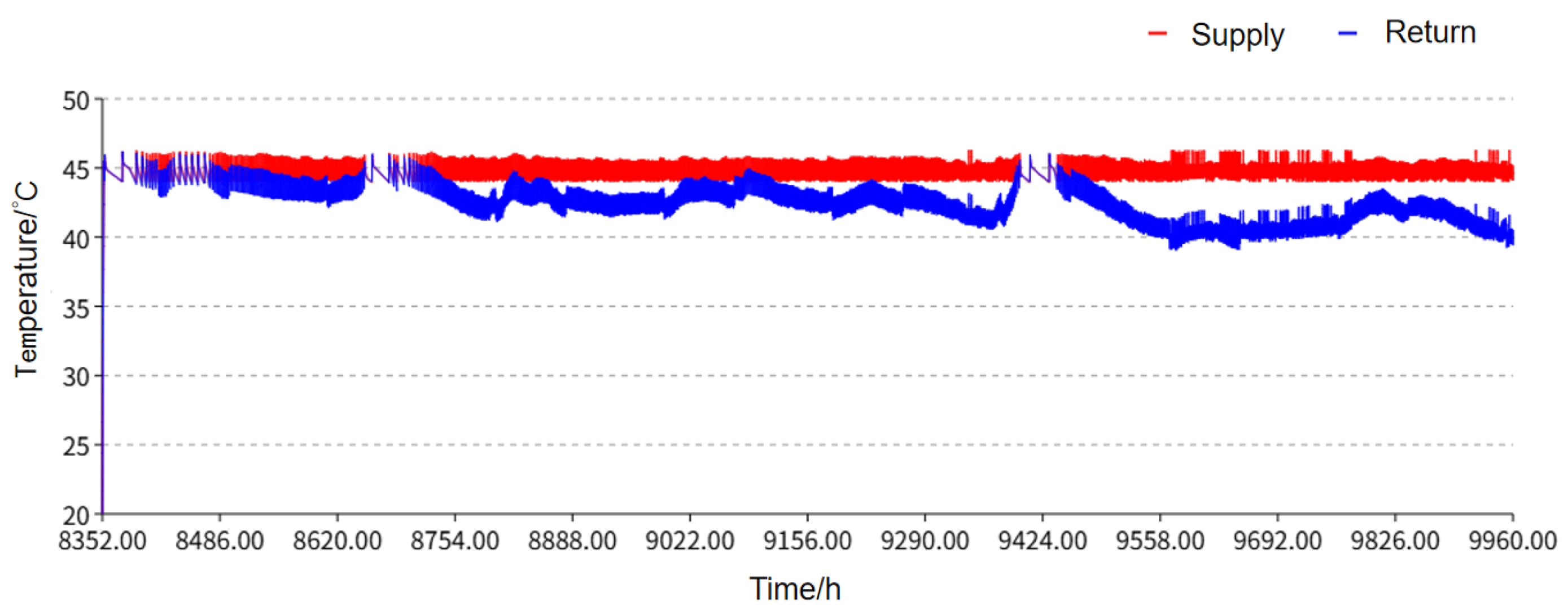

Figure 10.

Temporal variations of supply and return water temperatures.

Figure 10.

Temporal variations of supply and return water temperatures.

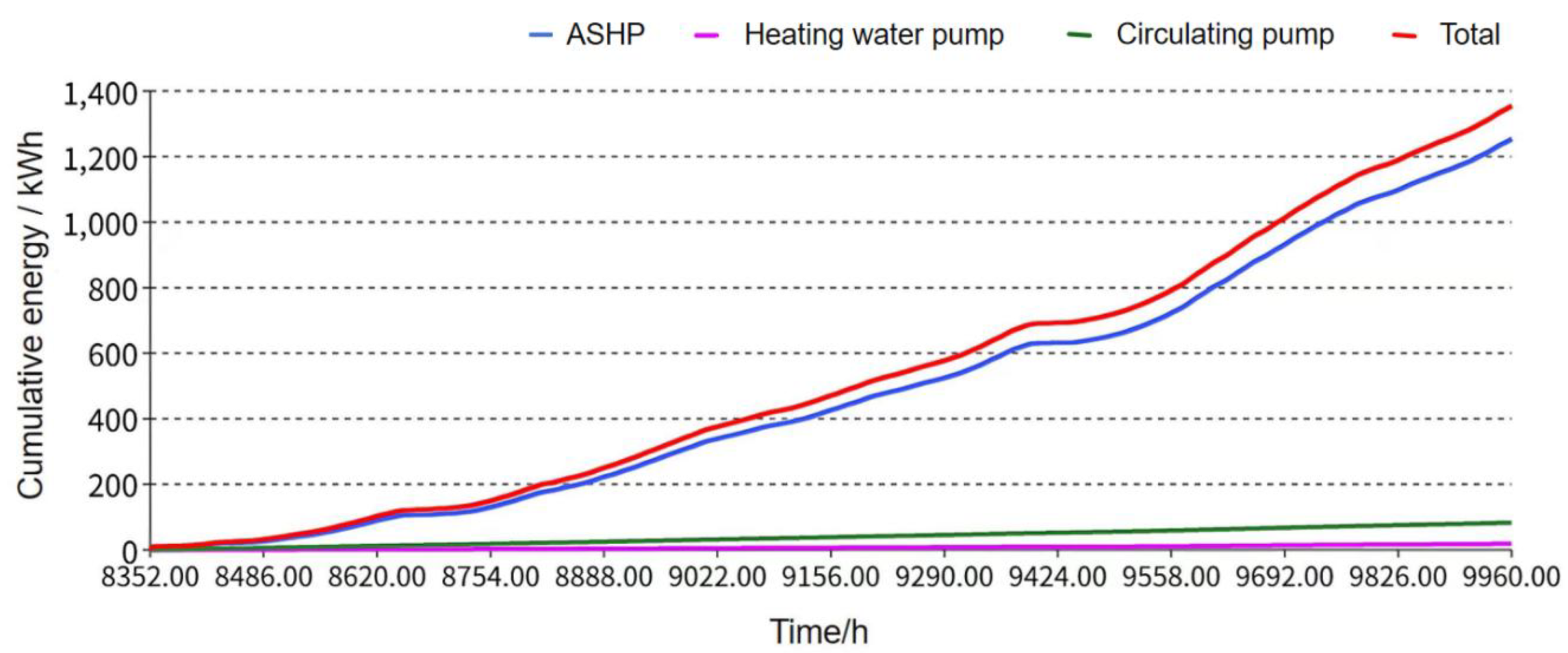

Figure 11.

Cumulative energy distribution.

Figure 11.

Cumulative energy distribution.

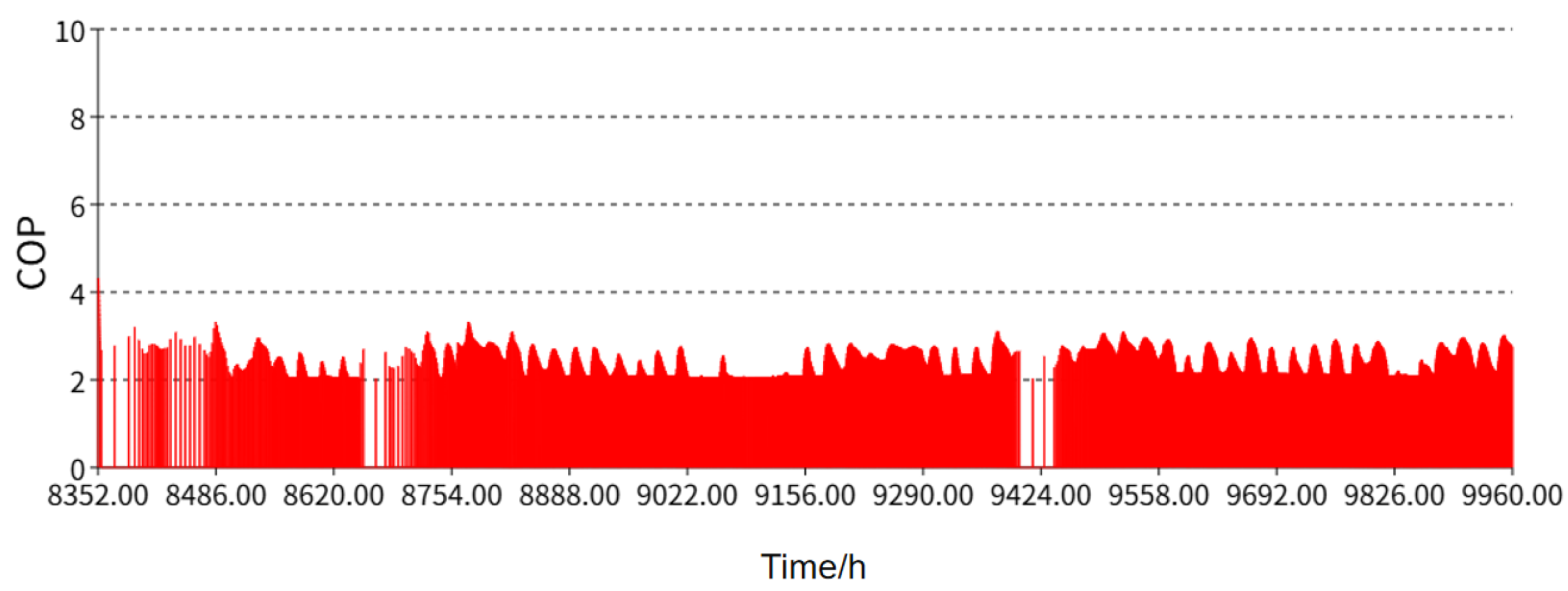

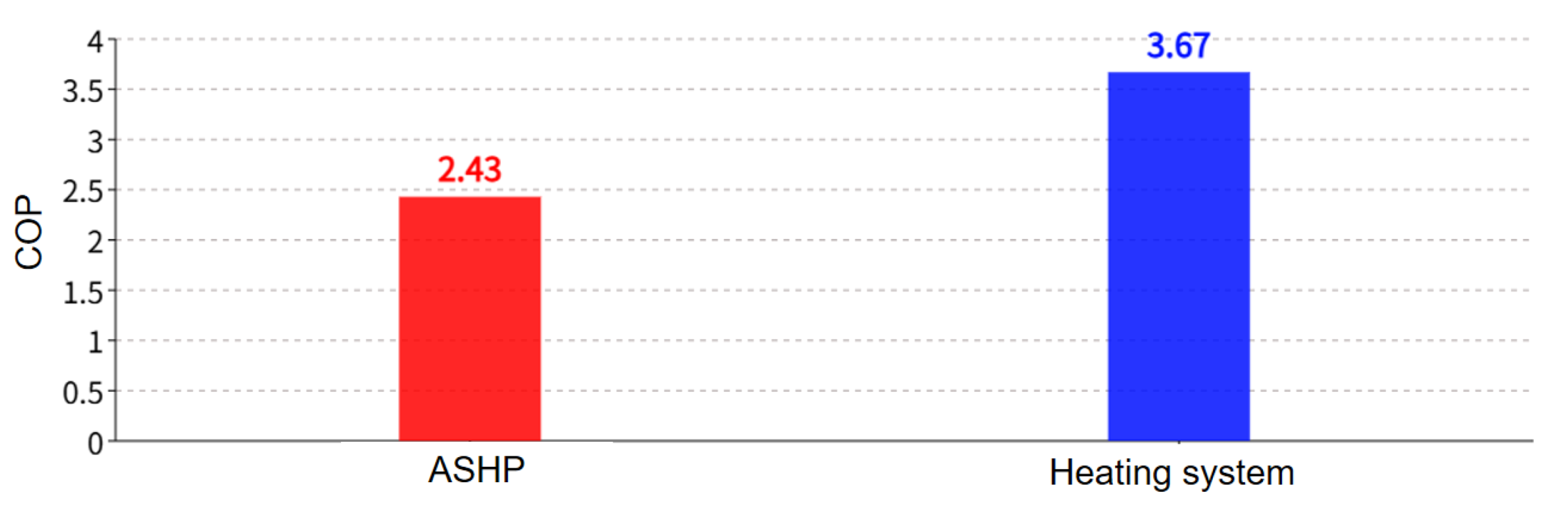

Figure 13.

Average energy efficiency comparison between ASHP and heating system.

Figure 13.

Average energy efficiency comparison between ASHP and heating system.

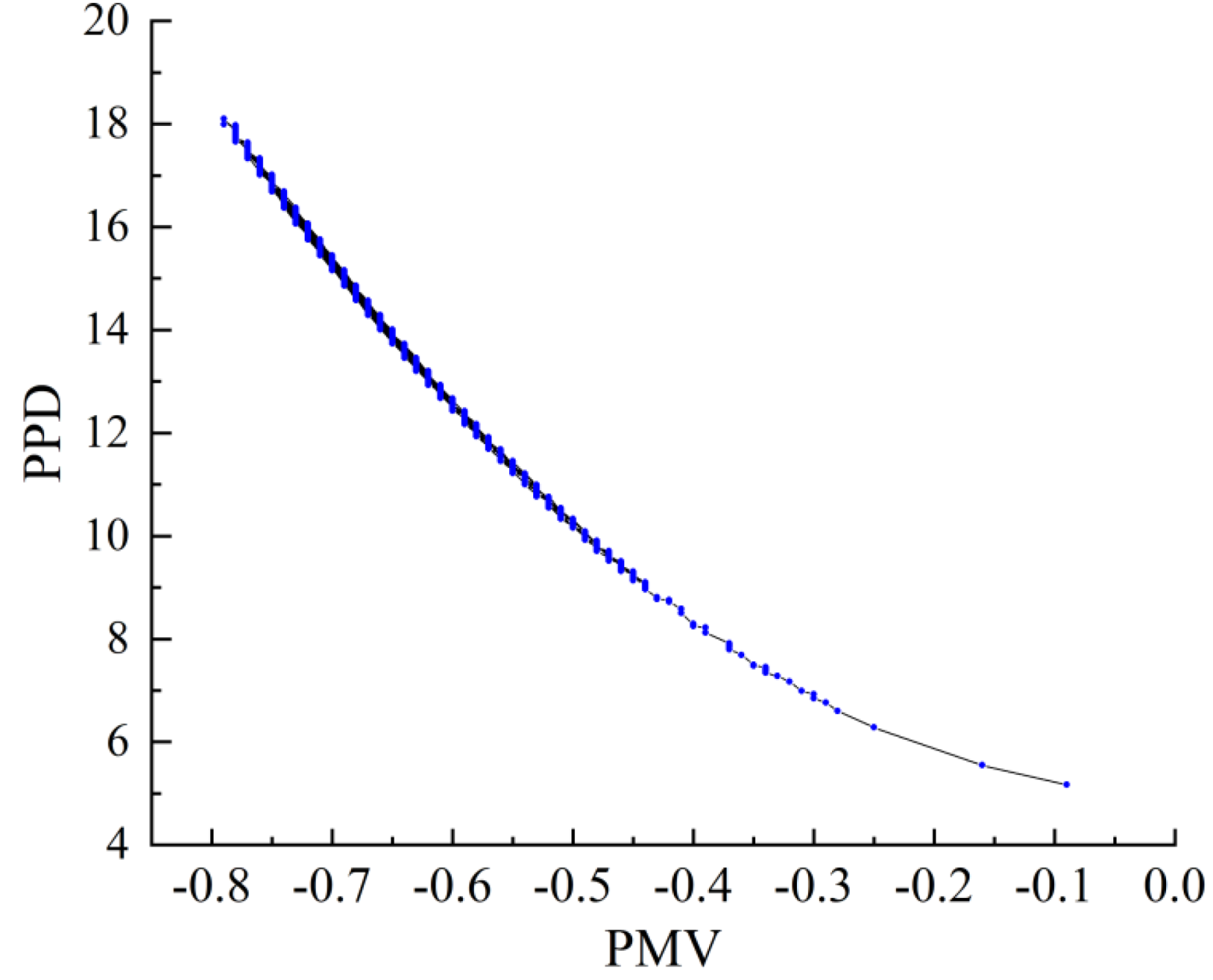

Figure 14.

Thermal comfort curve.

Figure 14.

Thermal comfort curve.

Figure 15.

Comparison of the optimization of four variables.

Figure 15.

Comparison of the optimization of four variables.

Figure 16.

Comparison of initial investment and annual cost before and after optimization.

Figure 16.

Comparison of initial investment and annual cost before and after optimization.

Table 1.

The enclosure structure and external window parameters.

Table 1.

The enclosure structure and external window parameters.

| Enclosure Type |

Composition |

Heat transfer coefficient W/(m2·K) |

Limit value of heat transfer coefficient W/(m2·K) |

| Construction material |

Thickness (mm) |

| External wall |

Cement mortar |

20 |

0.467 |

0.5 |

| Steel reinforced concrete |

165 |

| Extruded polystyrene foam board |

55 |

| Cement mortar |

20 |

| Roof |

Cement mortar |

20 |

0.196 |

0.2 |

| Extruded polystyrene foam board |

75 |

| Steel reinforced concrete |

80 |

| Extruded polystyrene foam board |

70 |

| Cement mortar |

20 |

| External window |

Broken bridge aluminum window |

1.690 |

1.8 |

| Floor |

Cement mortar |

20 |

0.755 |

- |

| Aerated concrete |

200 |

| Cement mortar |

20 |

Table 2.

TRNSYS module configuration table.

Table 2.

TRNSYS module configuration table.

| Module Name |

Type |

Quantity |

Module Name |

Type |

Quantity |

| Meteorological data |

Type15-2 |

1 |

Controller |

Type2b |

2 |

| Solar collector |

Type1b |

1 |

Data reader |

Type9e |

1 |

| ASHP |

Type941 |

1 |

Calculator |

Equation |

6 |

| Thermal storage tank |

Type158 |

1 |

Integrator |

Type24 |

2 |

| Pump |

Type114 |

3 |

Printer |

Type65c |

3 |

| Converging tee |

Type11h |

1 |

Integral printer |

Type28b |

1 |

| Diverging tee |

Type11f |

1 |

Scheduler |

Type14h |

2 |

| Heating terminal |

Type682 |

1 |

Optimizer |

TRNOPT |

1 |

Table 3.

Key design parameters for the SASHP system in Hangzhou.

Table 3.

Key design parameters for the SASHP system in Hangzhou.

| Parameter |

Value |

Unit |

| Collector area (Ac) |

38.63 |

m² |

| ASHP rated capacity (Qhp) |

11 |

kW |

| ASHP rated power |

2.72 |

kW |

| Thermal storage tank volume |

1.16 |

m³ |

| Solar collector pump flow rate |

2086 |

kg/h |

| ASHP pump flow rate |

945 |

kg/h |

Table 5.

Electricity price.

Table 5.

Electricity price.

| Period of time |

Electricity price (¥/kWh) |

| 8:00-22:00 |

0.568 |

| 22:00-8:00 (the next day) |

0.288 |

Table 6.

Genopt variable parameter settings.

Table 6.

Genopt variable parameter settings.

| Parameter |

Collector area(m2) |

Tilt of collector(°) |

Rated heat capacity ofASHP(kW)

|

Water tank volume per unit heat collection area (m3) |

| Initial value |

38.63 |

45 |

10.5 |

0.2 |

| Minimum value |

15 |

20 |

5 |

0.2 |

| Maximum value |

80 |

80 |

12 |

0.6 |

| Iterative step |

5 |

2 |

1 |

0.2 |

Table 7.

Comparison of heating system variables before and after optimization.

Table 7.

Comparison of heating system variables before and after optimization.

| Parameter |

Collector area(m2) |

Tilt angle of collector(°) |

Rated heat capacity of ASHP (kW) |

Water tank volume per unit heat collection area (m3) |

C0

|

AEC(¥/year)

|

| Before optimization |

38.63 |

45 |

11 |

1.16 |

24245 |

3039.95 |

| After optimization |

15 |

41 |

10.125 |

0.3 |

14364 |

2033.89 |

| Changing ratio |

-61.17% |

-8.89% |

-7.95% |

-74.14% |

-40.75% |

-33.09% |