Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Procedures and Materials

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Target Compounds

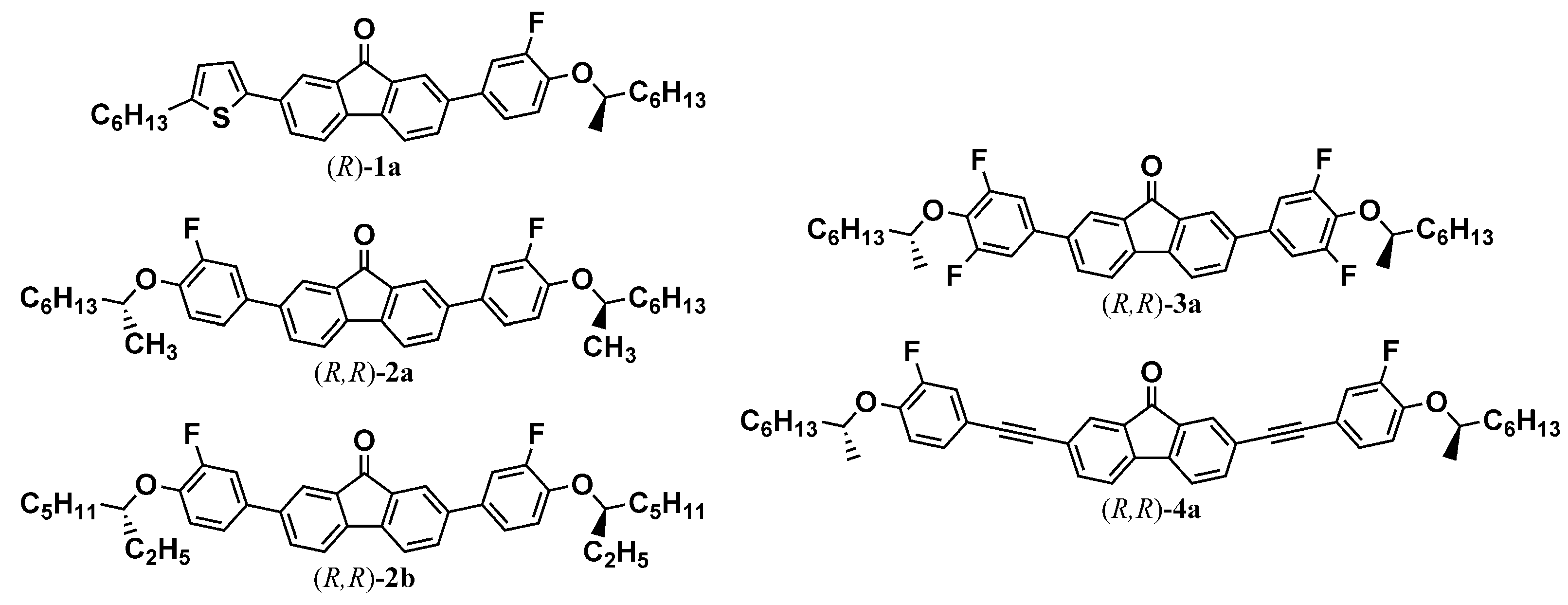

2.2.1. Characterization of (R)-1a

2.2.2. Characterization of (R,R)-2a

2.2.3. Characterization of (R,R)-2b

2.2.5. Characterization of (R,R)-3a

2.2.6. Characterization of (R,R)-4a

2.3. Characterization of Light-Absorption Properties

2.4. Characterization of LC Properties

3. Results and Discussion

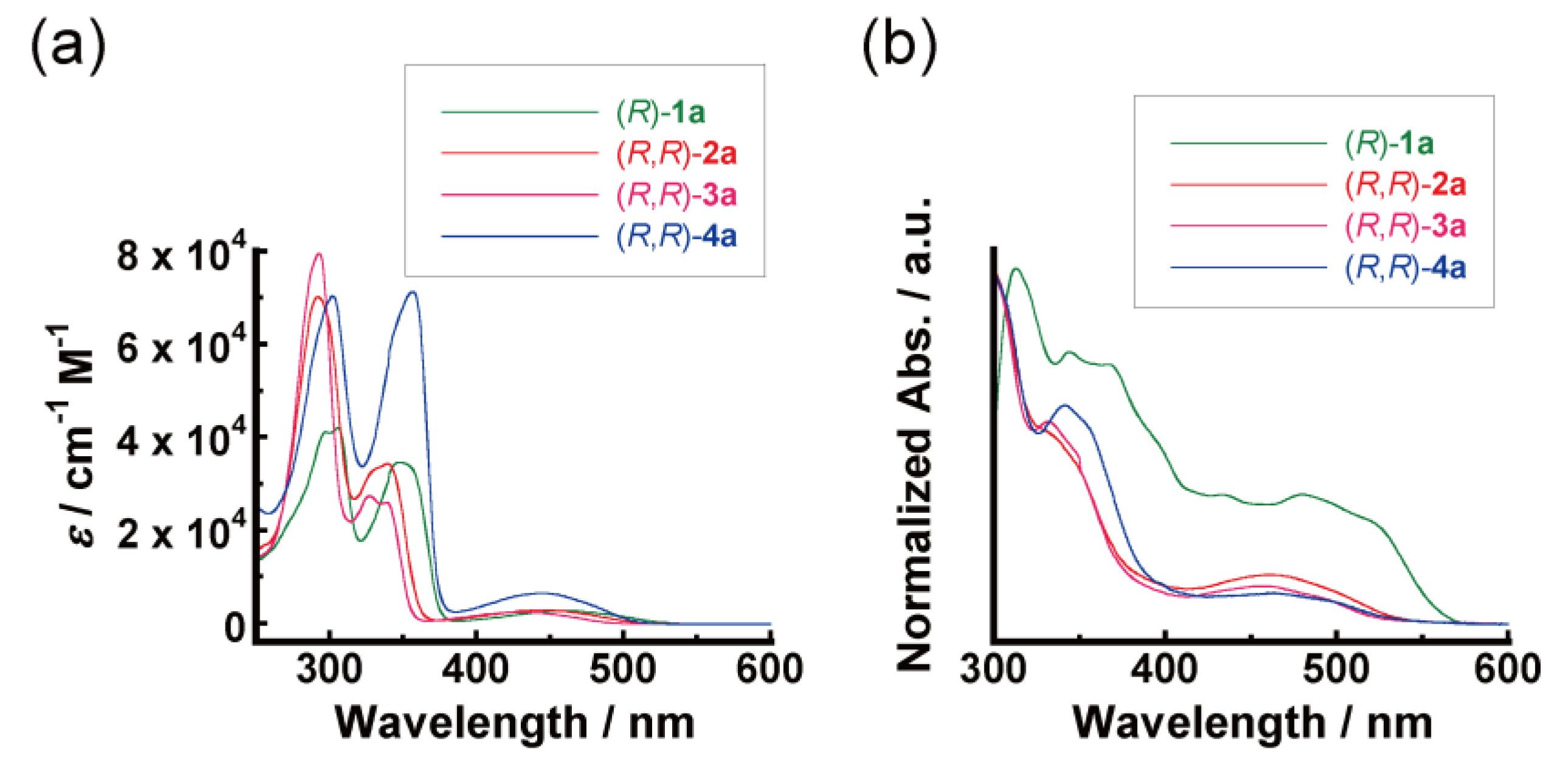

3.1. Light-Absorption Properties

3.2. Liquid-Crystalline Properties

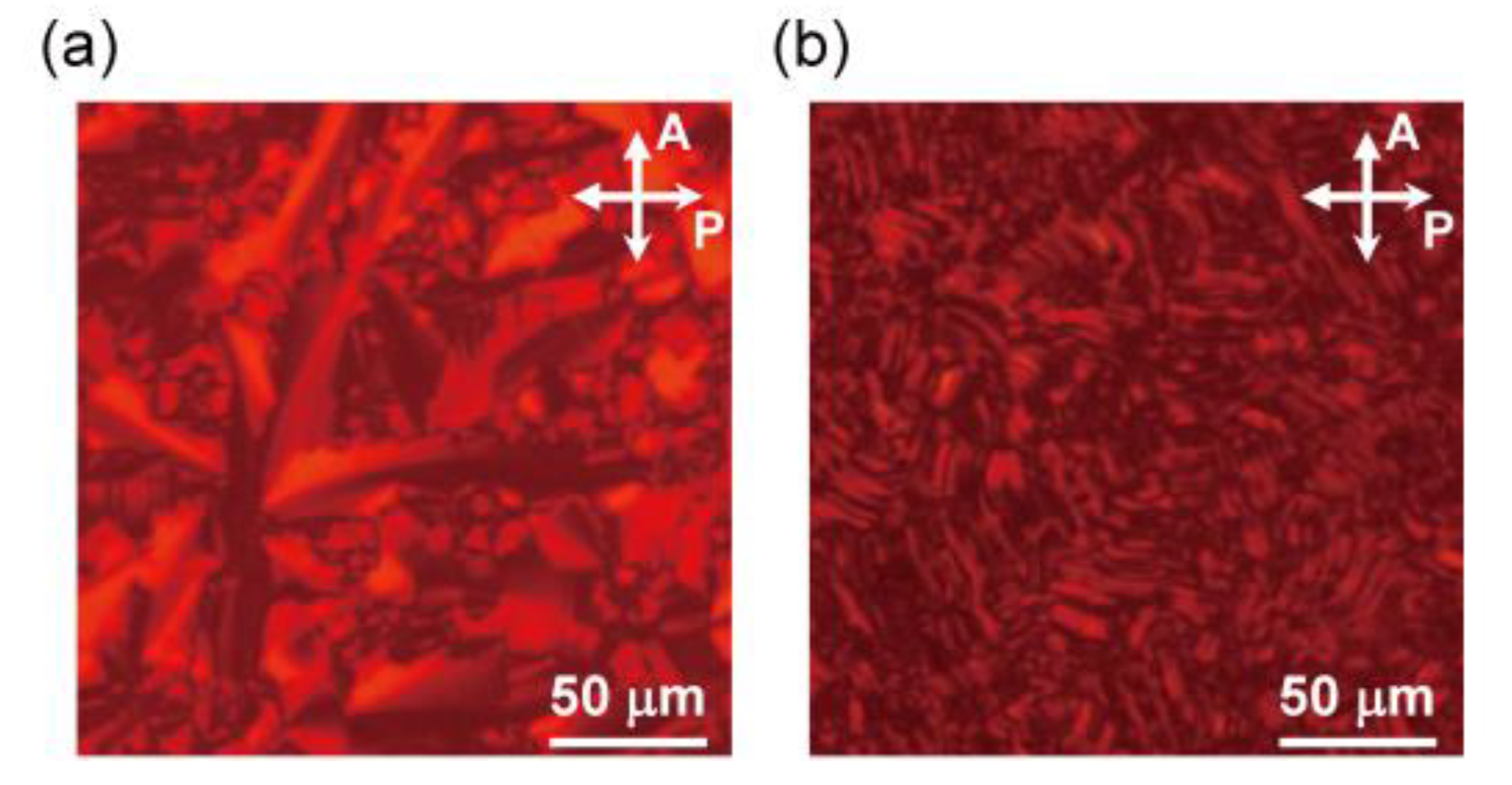

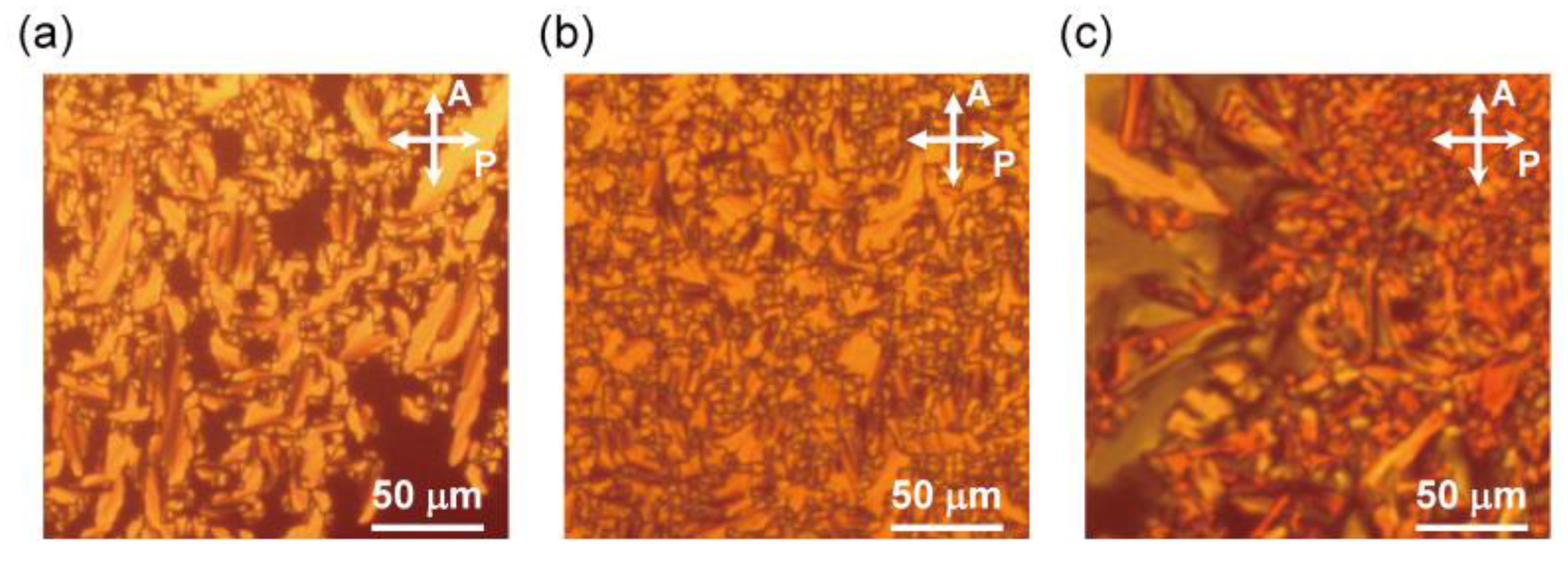

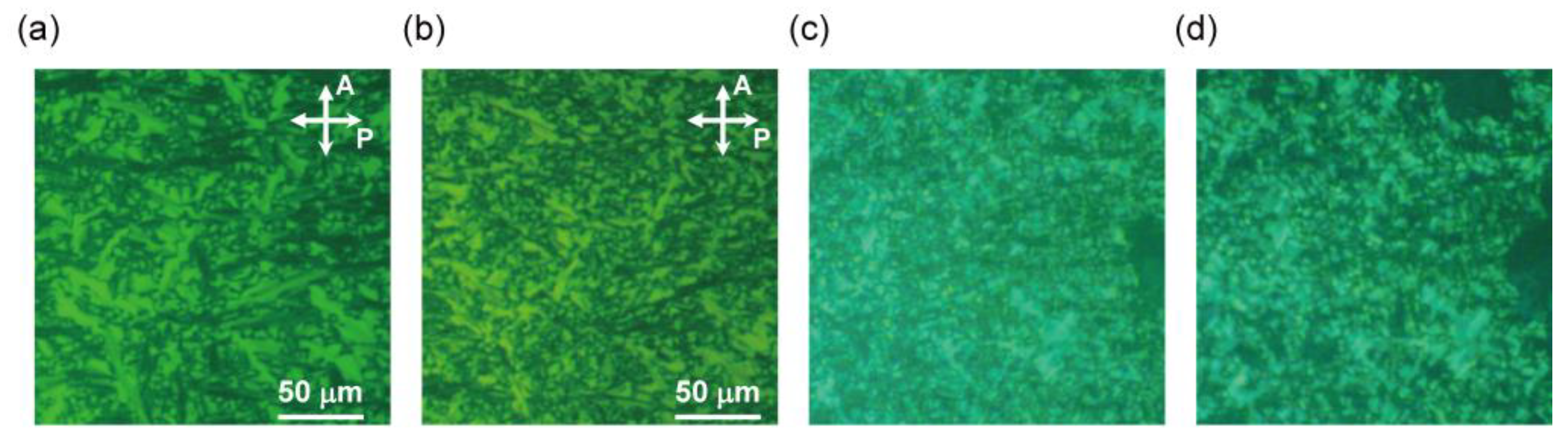

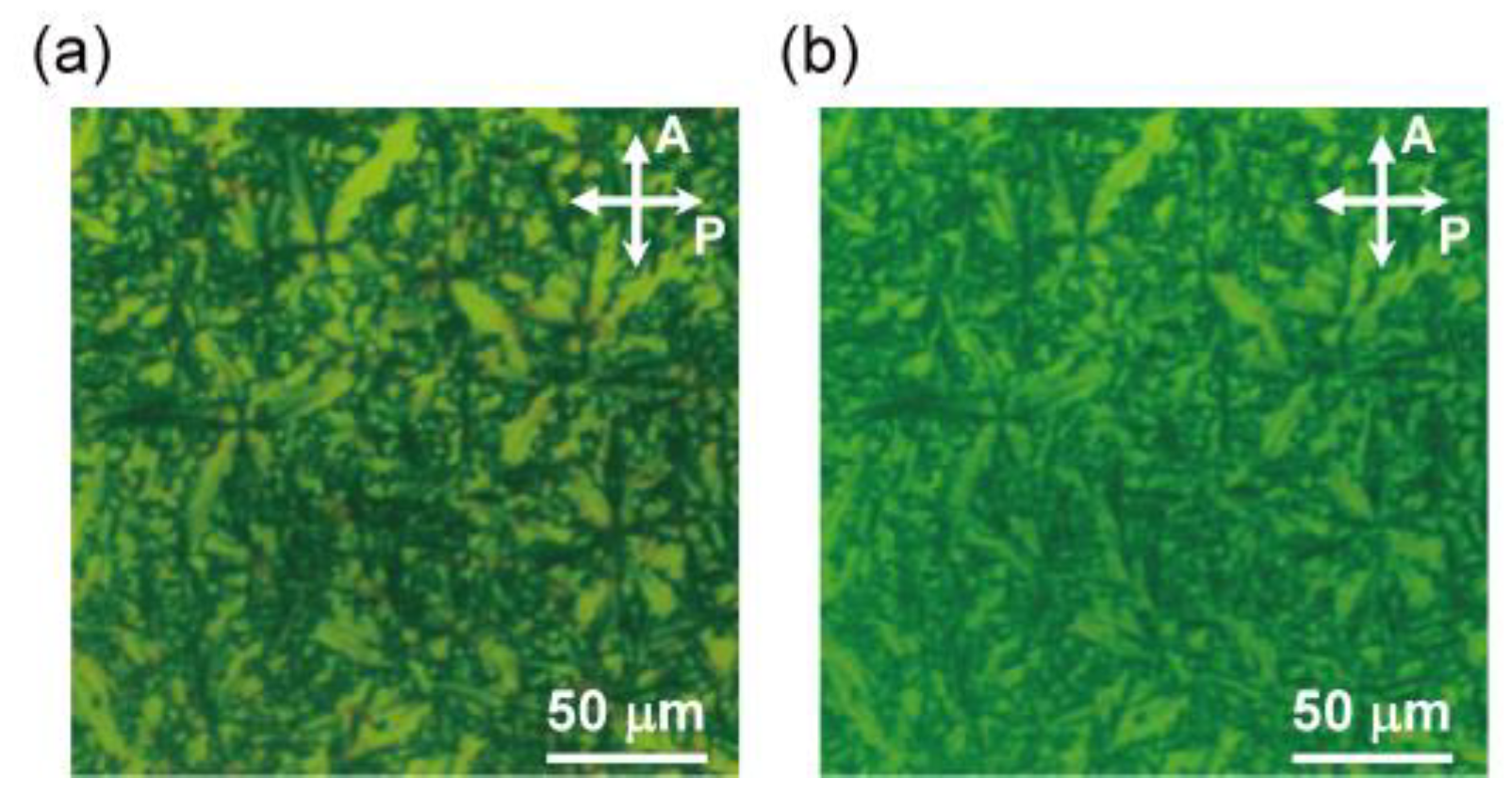

3.2.1. Polarizing Optical Microscopy

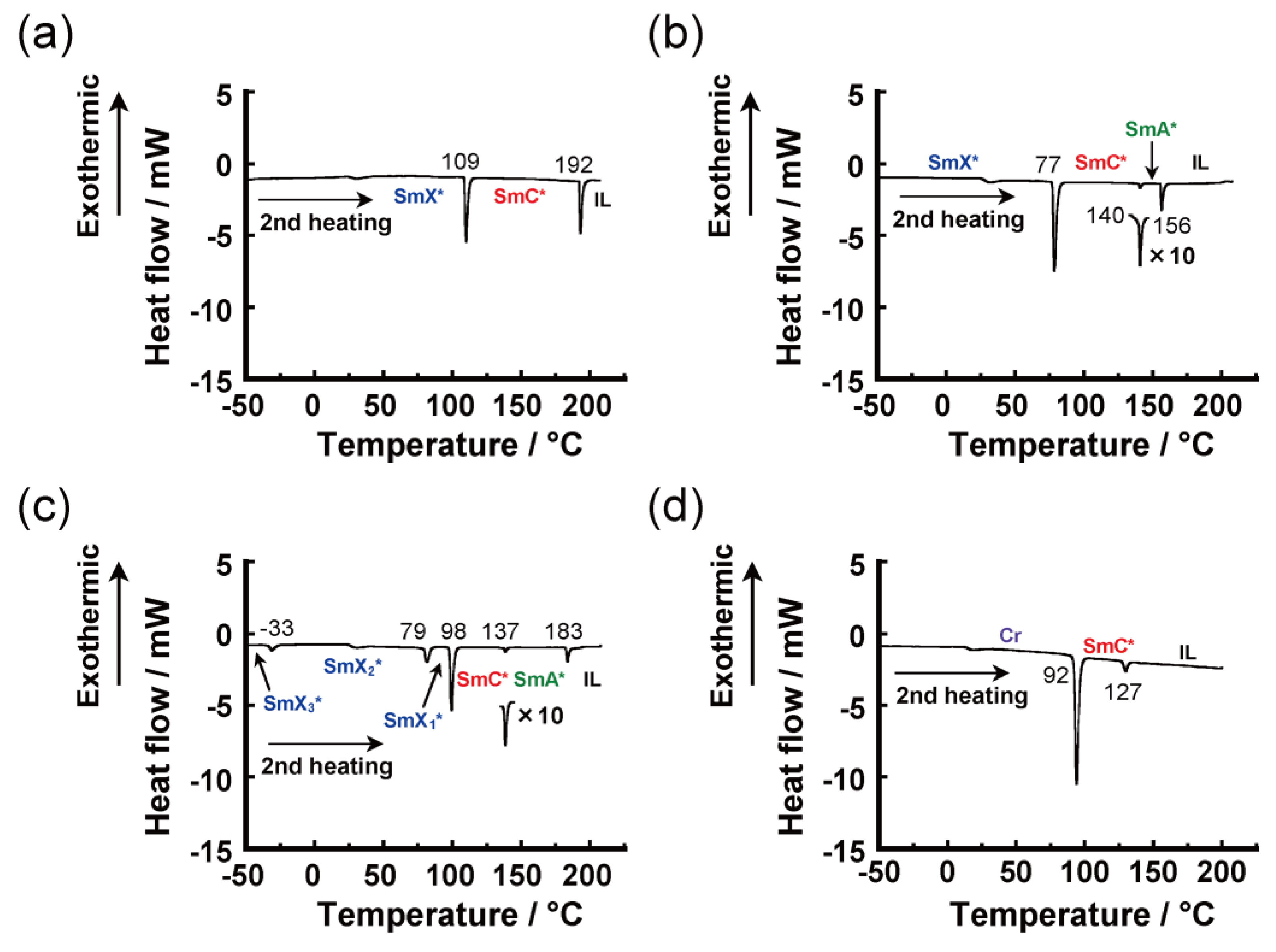

3.2.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

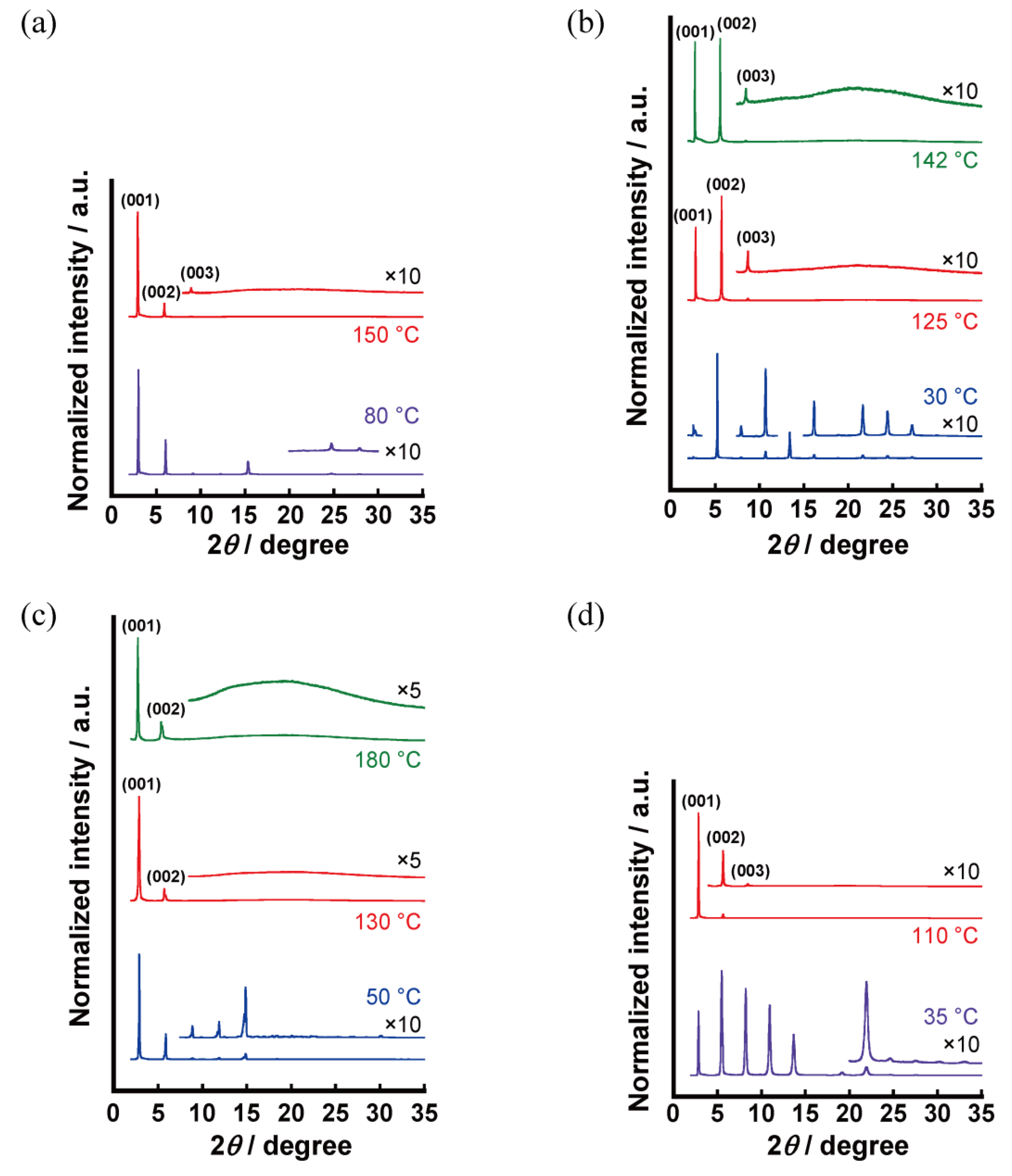

3.2.3. X-ray Diffraction

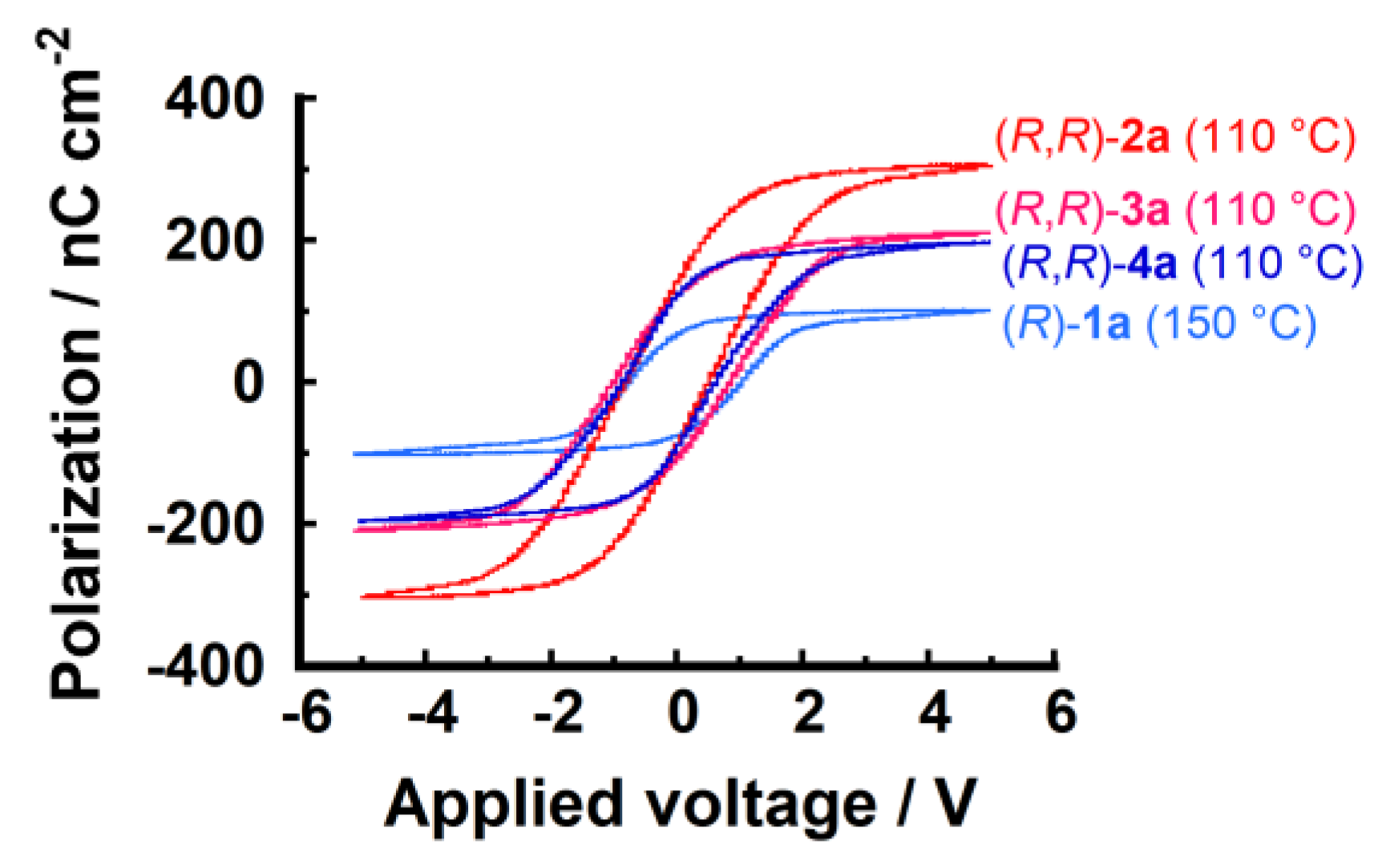

3.3. Ferroelectric Properties

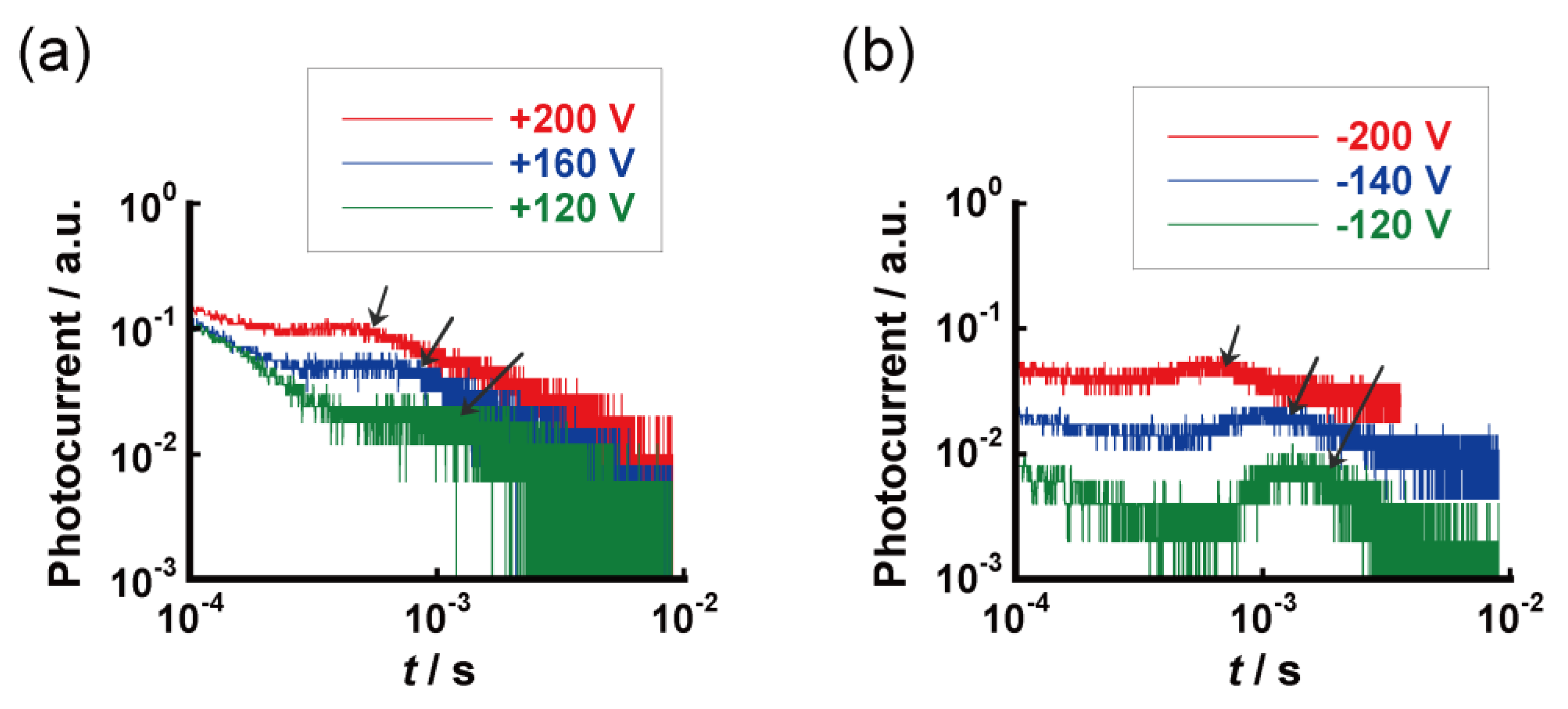

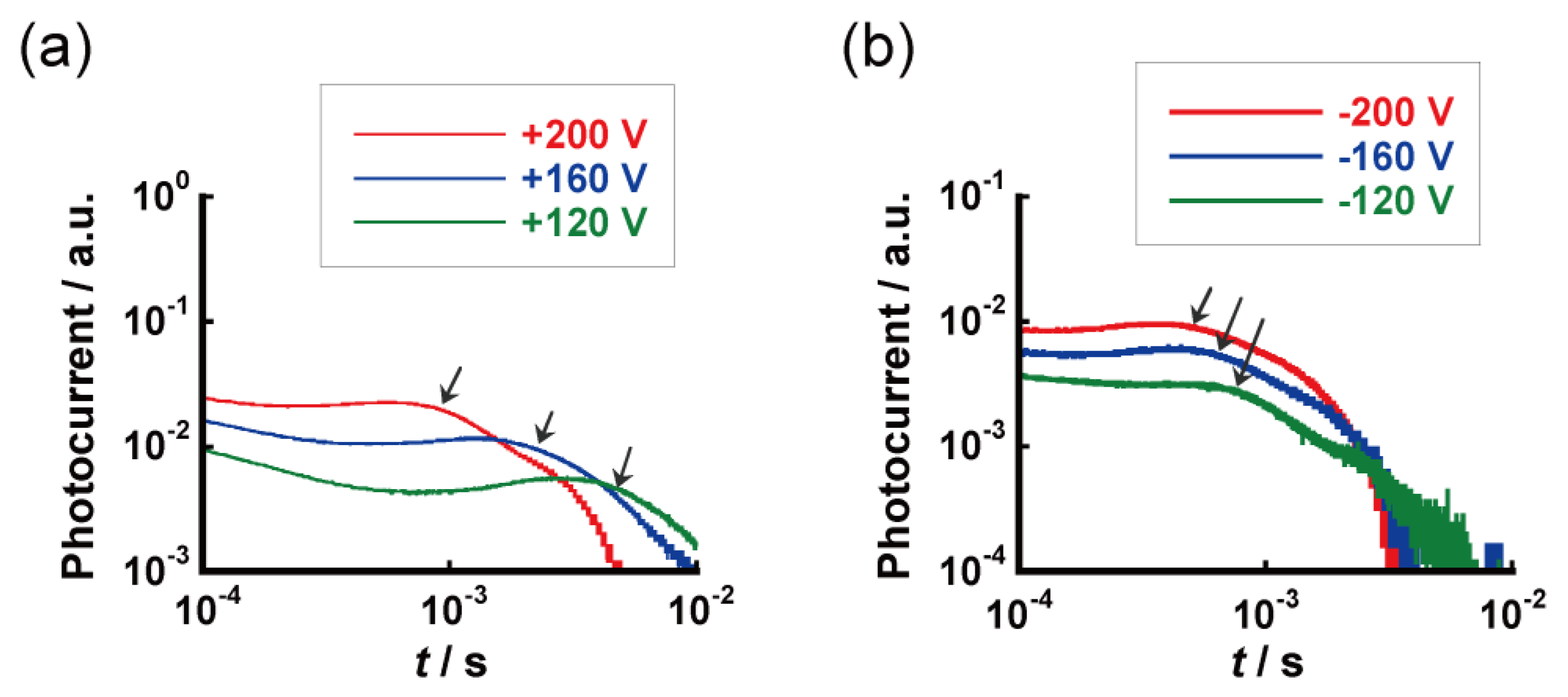

3.4. Carrier Transport Properties

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bisoyi, H. K.; Li, Q. Light-Directing Chiral Liquid Crystal Nanostructures: From 1D to 3D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 3184–3195.

- Pescitelli, G.; Di Bari, L.; Berova, N. Application of electronic circular dichroism in the study of supramolecular systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5211–5233.

- Zhang, L.; Qin, L.; Wang, X.; Cao, H.; Liu, M. Supramolecular Chirality in Self-Assembled Soft Materials: Regulation of Chiral Nanostructures and Chiral Functions. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 6959–6964.

- Yashima, E.; Ousaka, N.; Taura, D.; Shimomura, K.; Ikai, T.; Maeda, K. Supramolecular Helical Systems: Helical Assemblies of Small Molecules, Foldamers, and Polymers with Chiral Amplification and Their Functions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 13752–13990.

- Evers, F.; Aharony, A.; Bar-Gill, N.; Entin-Wohlman, O.; Hedegård, P.; Hod, O.; Jelinek, P.; Kamieniarz, G.; Lemeshko, M.; Michaeli, K.; Mujica, V.; Naaman, R.; Paltiel, Y.; Refaely-Abramson, S.; Tal, O.; Thijssen, J.; Thoss, M.; van Ruitenbeek, J. M.; Venkataraman, L.; Waldeck, D. H.; Yan, B.; Kronik, L. Theory of Chirality Induced Spin Selectivity: Progress and Challenges. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, No.2106629.

- Dierking, I. Chiral Liquid Crystals: Structures, Phases, Effects. Symmetry 2014, 6, 444–472.

- Kitzerow, H.-S.; Bahr, C. (Eds.) Chirality in Liquid Crystals, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, USA, 2001.

- Goodby, J. W. Symmetry and Chirality in Liquid Crystals. In Handbook of Liquid Crystals, 1st ed.; Demus, D.; Goodby, J. W.; Gray, G. W.; Spiess, H.-W.; Vill, V., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 115–132.

- Meyer, R. B.; Libert, L.; Strzelecki, L.; Keller, P. Ferroelectric liquid crystals. J. Phys. 1975, 36, L69–L71.

- Lagerwall, S. T.; Dahl, I. Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1984, 114, 151–187.

- Takanishi, Y.; Takezoe, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Kobayashi, I.; Yajima, T.; Terada, M.; Mikami, K. Spontaneous Enantiomeric Resolution in a Fluid Smectic Phase of a Racemate. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2353–2356.

- Young, C. Y.; Pindak, R.; Clark, N. A.; Meyer, R. B. Light-Scattering Study of Two-Dimensional Molecular-Orientation Fluctuations in a Freely Suspended Ferroelectric Liquid-Crystal Film. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978, 40, 773–776.

- Clark, N. A.; Lagerwall, S. T. Submicrosecond bistable electro-optic switching in liquid crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1980, 36, 899–901.

- Lago-Silva, M.; Fernández-Míguez, M.; Rodríguez, R.; Quiñoá, E.; Freire. F. Stimuli-responsive synthetic helical polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 793–852.

- Zhang, M.; Kim, M.; Choi, W.; Choi, J.; Kim, D. H.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Z. Chiral macromolecules and supramolecular assemblies: Synthesis, properties and applications. Prog. Polym. 2024, 151, No. 101800.

- García, F.; Gómez, R.; Sánchez, L. Chiral supramolecular polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 7524–7548.

- Seki, A.; Funahashi, M. Photovoltaic Effects in Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals based on Phenylterthiophene Derivatives. Chem. Lett. 2016, 45, 616–618.

- Seki, A.; Funatsu, Y.; Funahashi, M. Anomalous photovoltaic effect based on molecular chirality: Influence of enantiomeric purity on the photocurrent response in π-conjugated ferroelectric liquid crystals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 16446–16455.

- Seki, A.; Funahashi, M. Chiral photovoltaic effect in an ordered smectic phase of a phenylterthiophene derivative. Org. Electron. 2018, 62, 311–319.

- Seki, A.; Yoshio, M.; Mori, Y.; Funahashi, M. Ferroelectric Liquid-Crystalline Binary Mixtures Based on Achiral and Chiral Trifluoromethylphenylterthiophenes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 53029–53038.

- Seki, A.; Shimizu, K.; Aoki, K. Chiral π-Conjugated Liquid Crystals: Impacts of Ethynyl Linker and Bilateral Symmetry on the Molecular Packing and Functions. Crystals 2022, 12, No.1278.

- Seki, A.; Funahashi, M.; Aoki, K. Ferroelectric Photovoltaic Effect in the Ordered Smectic Phases of Chiral π-Conjugated Liquid Crystals: Improved Current-Voltage Characteristics by Efficient Fixation of Polar Structure. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2023, 96, 1224–1233.

- Mulder, D. J.; Schenning, A. P. H. J.; Bastiaansen, C. W. M. Chiral-nematic liquid crystals as one-dimensional photonic materials in optical sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 6695–6705.

- Hartmann, W. J. A. M. Ferroelectric Liquid Crystal Displays for Television Application. Ferroelectrics 1991, 122, 1–26.

- Mondal, R.; Tönshoff, C.; Khon, D.; Neckers, D. C.; Bettinger, H. F. Synthesis, Stability, and Photochemistry of Pentacene, Hexacene, and Heptacene: A Matrix Isolation Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14281–14289.

- Mushrush, M.; Facchetti, A.; Lefenfeld, M.; Katz, H. E.; Marks, T. J. Easily Processable Phenylene−Thiophene-Based Organic Field-Effect Transistors and Solution-Fabricated Nonvolatile Transistor Memory Elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9414–9423.

- Wu, J. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds for Organic Field-effect Transistors: Molecular Design and Syntheses. Curr. Org. Chem. 2007, 11, 1220–1240.

- Fichou, D. Structural order in conjugated oligothiophenes and its implications on opto-electronic devices. J. Mater. Chem. 2000, 10, 571–588.

- Zhang, L.; Colella, N. S.; Cherniawski, B. P.; Mannsfeld, S. C. B.; Briseno, A. L. Oligothiophene semiconductors: synthesis, characterization, and applications for organic devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 5327–5343.

- Warman, J. M.; de Haas, M. P.; Dicker, G.; Grozema, F. C.; Piris, J.; Debije, M. G. Charge Mobilities in Organic Semiconducting Materials Determined by Pulse-Radiolysis Time-Resolved Microwave Conductivity: π-Bond-Conjugated Polymers versus π−π-Stacked Discotics. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 4600–4609.

- Pisula, W.; Zorn, M.; Chang, J. Y.; Müllen, K.; Zentel, R. Liquid Crystalline Ordering and Charge Transport in Semiconducting Materials. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2009, 30, 1179–1202.

- O’Neill, M.; Kelly, S. M. Ordered Materials for Organic Electronics and Photonics. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 566–584.

- Funahashi, M. Nanostructured liquid-crystalline semiconductors – a new approach to soft matter electronics. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 7451–7459.

- Funahashi, M.; Kato, T. Design of liquid crystals: from a nematogen to thiophene-based π-conjugated mesogens. Liq. Cryst. 2015, 42, 909–917.

- Seki, A.; Funahashi, M. Nanostructure Formation Based on the Functionalized Side Chains in Liquid-Crystalline Heteroaromatic Compounds. Heterocycles 2016, 92, 3–30.

- Kato, T.; Yoshio, M.; Ichikawa, T.; Soberats, B.; Ohno, H.; Funahashi, M. Transport of ions and electrons in nanostructured liquid crystals. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, No.17001.

- Funahashi, M.; Hanna, J. Photoconductive Behavior in Smectic A Phase of 2-( 4’-Heptyloxyphenyl)-6-Dodecylthiobenzothiazole. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 35, No. L703.

- Funahashi, M.; Hanna, J.-I. High Carrier Mobility up to 0.1 cm2 V–1 s–1 at Ambient Temperatures in Thiophene-Based Smectic Liquid Crystals. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 594–598.

- Funahashi, M.; Sonoda, A. High electron mobility in a columnar phase of liquid-crystalline perylene tetracarboxylic bisimide bearing oligosiloxane chains. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 25190–25197.

- Adam, D.; Closs, F.; Frey, T.; Funhoff, D.; Haarer, D.; Ringsdorf, H.; Schuhmacher, P.; Siemensmeyer, K. Transient photoconductivity in a discotic liquid crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 457–460.

- Boden, N.; Bushby, R. J.; Clements, J.; Movaghar, B.; Donovan, K. J.; Kreouzis, T. Mechanism of charge transport in discotic liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1995, 52, 13274–13280.

- Simmerer, J.; Glüsen, B.; Paulus, W.; Kettner, A.; Schuhmacher, P.; Adam, D.; Etzbach, K.-H.; Siemensmeyer, K.; Wendorff, J. H.; Ringsdorf, H.; Haarer, D. Transient photoconductivity in a discotic hexagonal plastic crystal. Adv. Mater. 1996, 8, 815– 819.

- Ban, K.; Nishikawa, K.; Ohta, K.; van de Craats, A. M.; Warman, J. M.; Yamamoto, I.; Shirai, H. Discotic liquid crystals of transition metal complexes 29: Mesomorphism and charge transport properties of alkylthiosubstituted phthalocyanine rare-earth metal sandwich complexes. J. Mater. Chem. 2001, 11, 321–331.

- Demenev, A.; Eichhorn, S. H.; Taerum, T.; Perepichka, D. F.; Patwardhan, S.; Grozema, F. C.; Siebbeles, L. D. A.; Klenkler, R. Quasi temperature independent electron mobility in hexagonal columnar mesophases of an H-bonded benzotristhiophene derivative. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 1420–1428.

- Pisula, W.; Menon, A.; Stepputat, M.; Lieberwirth, I.; Kolb, U.; Tracz, A.; Sirringhaus, H.; Pakula, T.; Mullen, K. A Zone Cast-ing Technique for Device Fabrication of Field-Effect Transistors Based on Discotic Hexa-peri-Hexabenzocoronene. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 684–689.

- van Breemen, A. J. J. M.; Herwig, P. T.; Chlon, C. H. T.; Sweelssen, J.; Schoo, H. F. M.; Setayesh, S.; Hardeman, W. M.; Martin, C. A.; de Leeuw, D. M.; Valeton, J. J. P.; Bastiaansen, C. W. M.; Broer, D. J.; PopaMerticaru, A. R.; Meskers, S. C. J. Large Area Liquid Crystal Monodomain Field-Effect Transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2336–2345.

- Funahashi, M.; Zhang, F.; Tamaoki, N. High Ambipolar Mobility in a Highly Ordered Smectic Phase of a Dialkylphenylterthiophene Derivative That Can Be Applied to Solution-Processed Organic Field-Effect Transistors. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 353–358.

- Mori, T.; Komiyama, H.; Ichikawa, T.; Yasuda, T. A liquid-crystalline semiconducting polymer based on thienylene–vinylene–thienylene: Enhanced hole mobilities by mesomorphic molecular ordering and thermoplastic shape-deformable characteristics. Polym. J. 2020, 52, 313–321.

- Hassheider, T.; Benning, S. A.; Kitzerow, H. -S.; Achard, M. -F.; Bock, H. Color-Tuned Electroluminescence from Columnar Liquid Crystalline Alkyl Arenecarboxylates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2060–2063.

- Benning, S. A.; Oesterhaus, R.; Kitzerow, H. -S. Polarized electroluminescence of a discotic mesogenic compound. Liq. Cryst. 2004, 31, 201–205.

- Aldred, M. P.; Contoret, A. E. A.; Farrar, S. R.; Kelly, S. M.; Mathieson, D.; O’Neill, M.; Tsoi, W. C.; Vlachos, P. A Full-Color Electroluminescent Device and Patterned Photoalignment Using Light-Emitting Liquid Crystals. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 1368–1372.

- Hori, T.; Miyake, Y.; Yamasaki, N.; Yoshida, H.; Fujii, A.; Shimizu, Y.; Ozaki, M. Solution Processable Organic Solar Cell Based on Bulk Heterojunction Utilizing Phthalocyanine Derivative. Appl. Phys. Express 2010, 3, No. 101602.

- Shin, W.; Yasuda, T.; Watanabe, G.; Yang, Y. S.; Adachi, C. Self-Organizing Mesomorphic Diketopyrrolo-pyrrole Derivatives for Efficient Solution-Processed Organic Solar Cells. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 2549–2556.

- Kogo, K.; Maeda, H.; Kato, H.; Funahashi, M.; Hanna, J. Photoelectrical Properties of a Ferroelectric Liquid Crystalline Photoconductor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999, 75, 3348−3350.

- Funahashi, M.; Hanna, J. High Ambipolar Carrier Mobility in Self-Organizing Terthiophene Derivative. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 76, 2574−2576.

- Funatsu, Y.; Sonoda, A.; Funahashi, M. Ferroelectric Liquid-crystalline Semiconductors Based on a Phenylterthiophene Skeleton: Effect of the Introduction of Oligosiloxane Moieties and Photovoltaic Effect. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 1982−1993.

- Yang, M.-C.; Hanna, J; Iino, H. Novel Calamitic Liquid Crystalline Organic Semiconductors Based on Electron-Deficient Dibenzo[c,h][2,6]naphthyridine: Synthesis, Mesophase, and Charge Transport Properties by the Time-of-Flight Technique. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 13192−13202.

- Porzio, W.; Destri, S.; Giovanella, U.; Pasini, M.; Motta, T.; Natali, D.; Sampietro, M.; Campione, M. Fluorenone–thiophene derivative for organic field effect transistors: A combined structural, morphological and electrical study. Thin Solid Films 2005, 492, 212−220.

- Lincker, F.; Attias, A. -J.; Mathevet, F.; Heinrich, B.; Donnio, B.; Fave, J. -L.; Rannou, P.; Demadrille, R. Influence of polymorphism on charge transport properties in isomers of fluorenone-based liquid crystalline semiconductors. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 3209−3211.

- Lim, C. J.; Lei, Y.; Wu, B.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, F.; Ong, B. S.; Hu, X.; Ng, S. -C. Synthesis and characterization of two fluorenone-based conjugated polymers and their application in solar cells and thin film transistors. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1430−1434.

- Suzuki, M.; Seki, A.; Yamada, S.; Aoki, K. Multi-stimuli-responsive behaviours of fluorenone-based donor–acceptor–donor triads in solution and supramolecular gel states. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 7401−7412.

- Suzuki, M.; Yamada, S.; Iwai, K.; Aoki, K.; Seki, A. Acid vapor–responsive supramolecular gels of hydrogen-bonding D–A type fluorenones, Chem. Lett. 2025, 54, No. upaf004.

- Kukhta, N. A.; da Silva Filho, D. A., Volyniuk, D.; Grazulevicius, J. V.; Sini, G. Can Fluorenone-Based Compounds Emit in the Blue Region? Impact of the Conjugation Length and the Ground-State Aggregation. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 1695–1707.

- Rao, P. B.; Rao, N. V. S.; Pisipati, V. G. K. M. The Smectic F Phase in nO.m Compounds. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1991, 206, 9–15.

- Ouchi, Y.; Uemura, T.; Takezoe, H.; Fukuda, A. Molecular Reorientation Process in Chiral Smectic I Liquid Crystal. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1985, 24, 893–895.

- Goodby, J. W. Optical Activity and Ferroelectricity in Liquid Crystals. Science 1986, 231, 350–355.

- Kelly, S. M.; O’Neill, M. Liquid Crystals for Electro-Optical Applications. In Handbook of Advanced Electronic and Photonic Materials and Devices. In Liquid Crystals, Display and Laser Materials; H. S. Nalwa Ed.; Academic Press: New York, USA, 2001; Vol. 7, pp. 1−66.

| Compound | Phase Transition Temperature / °C (Enthalpy / kJ mol−1) 1,2 |

| (R)-1a (R,R)-2a (R,R)-2b (R,R)-3a (R,R)-4a |

SmX* 109 (11) SmC* 192 (8) IL SmX1* 77 (16) SmC* 140 (1) SmA* 156 (3) IL G 44 IL SmX3* –33 (2) SmX2* 79 (4) SmX1* 98 (11) SmC* 137 (1) SmA* 183 (2) IL Cr 92 (23) SmC* 127 (2) IL |

| Compound | T/°C | V/V |

μ/ cm2 V−1 s−1 (Positive carrier) |

V/V |

μ/ cm2 V−1 s−1 (Negative carrier) |

| (R)-1a (R,R)-2a (R,R)-3a (R,R)-4a |

160 120 130 120 |

+200 +200 +200 +200 |

6 × 10–5 3 × 10–5 1 × 10–5 1 × 10–5 |

−200 −200 −200 −200 |

4 × 10–5 6 × 10–5 1 × 10–5 1 × 10–5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).