Submitted:

05 November 2025

Posted:

06 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

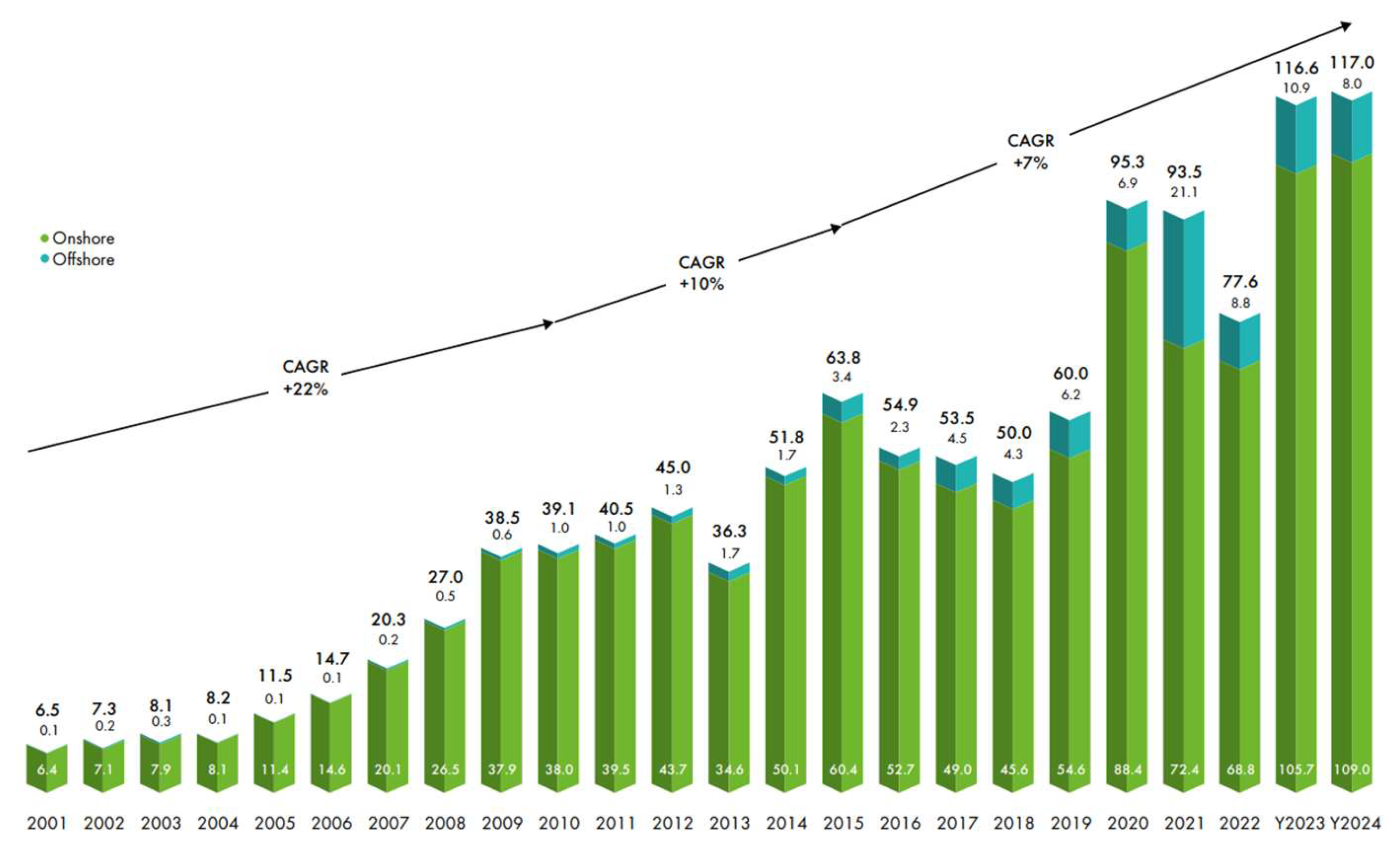

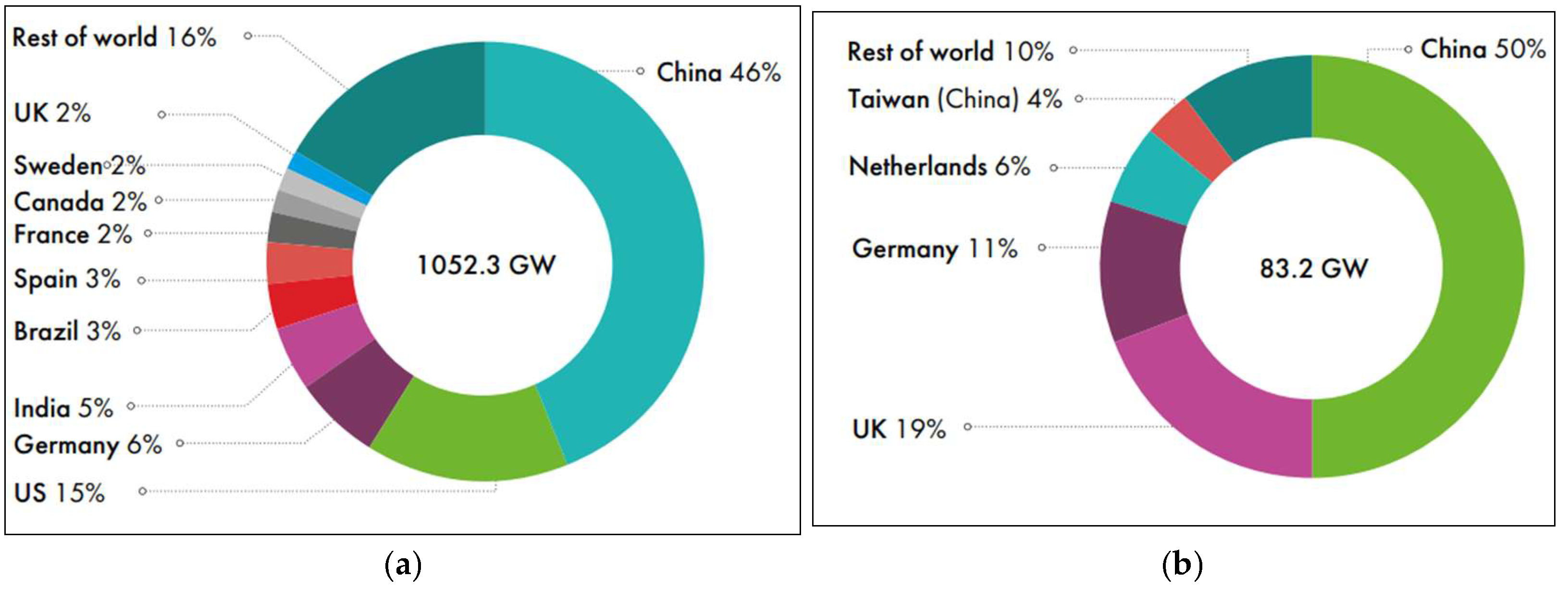

1. Introduction

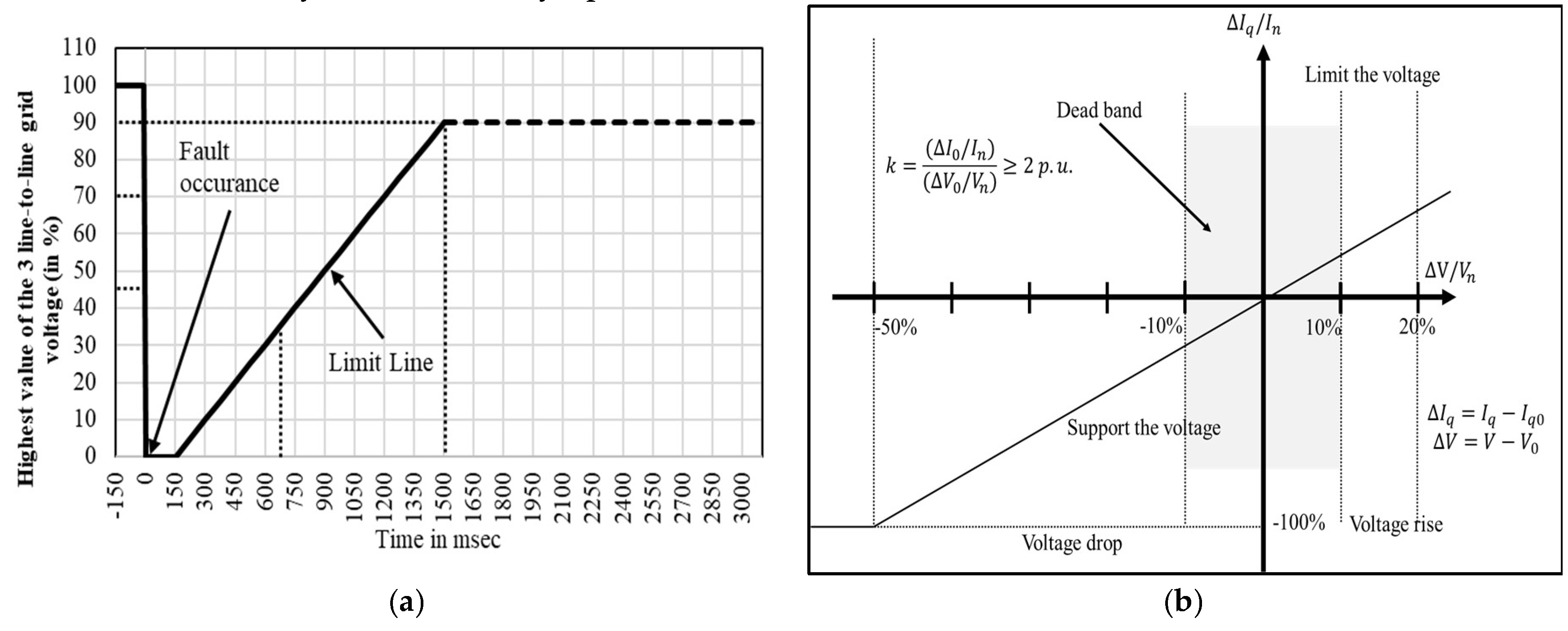

2. Enhancing the Grid Stability Based Wind Power Integration

3. Numerical Methods to Determine the Weibull Parameters

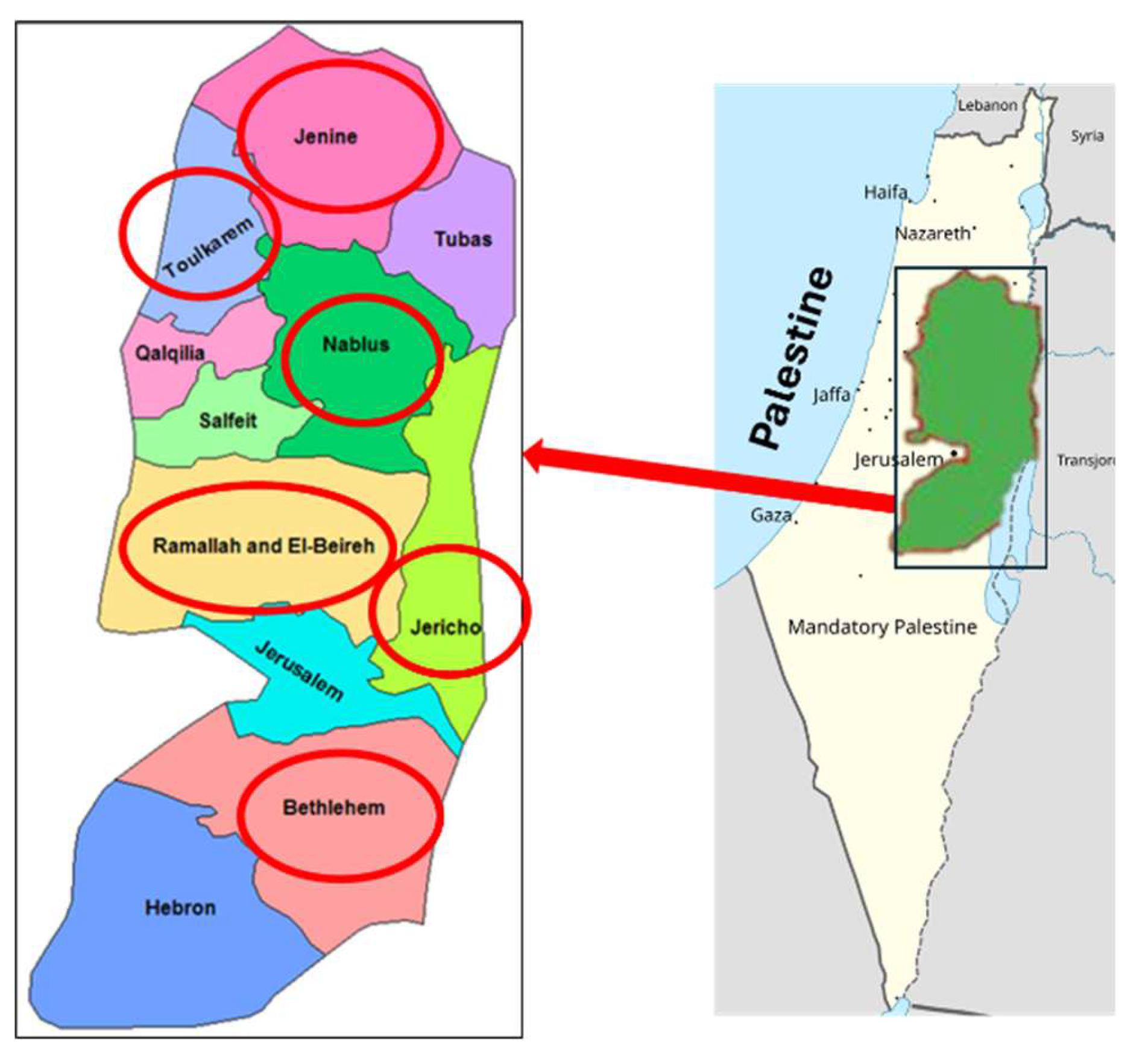

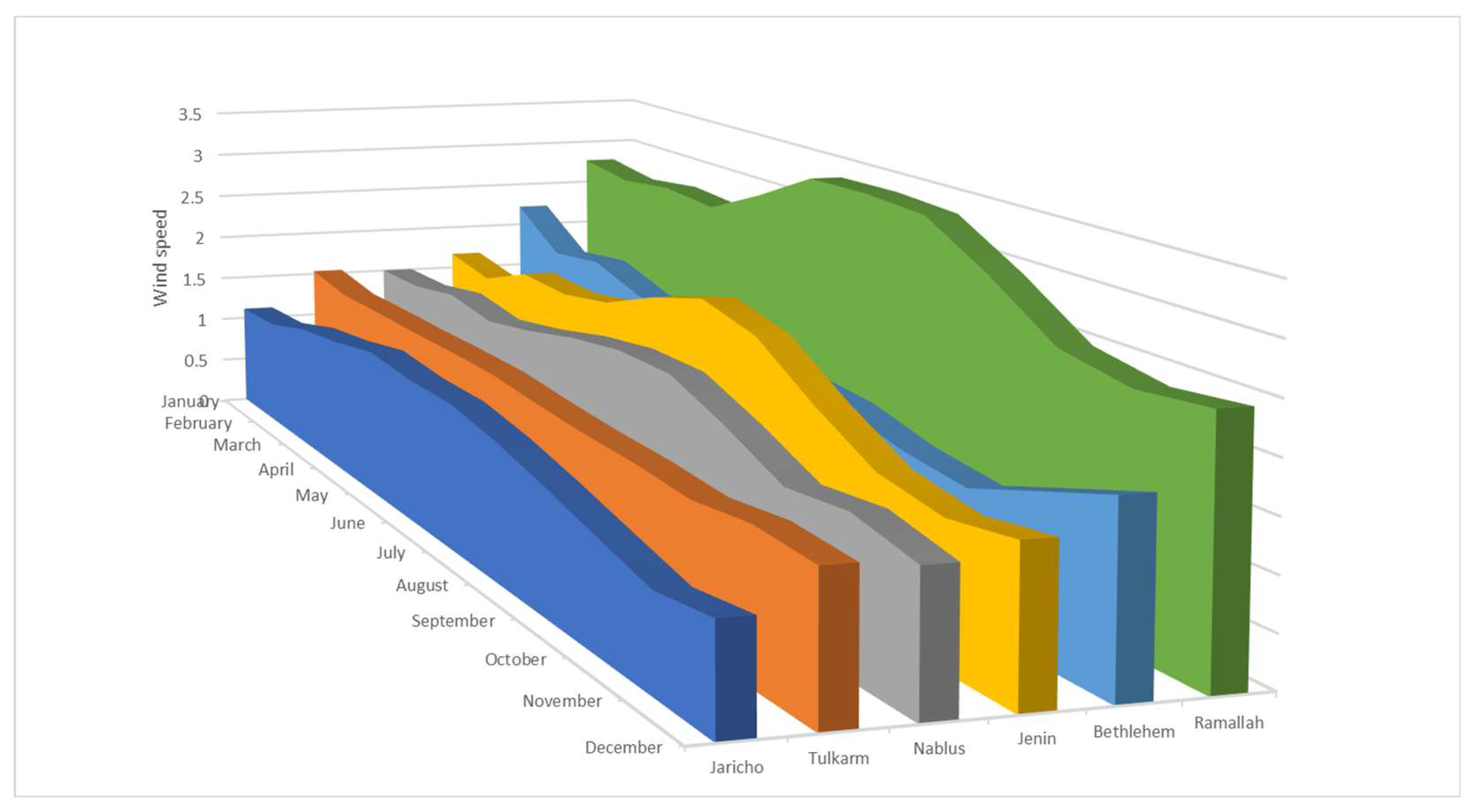

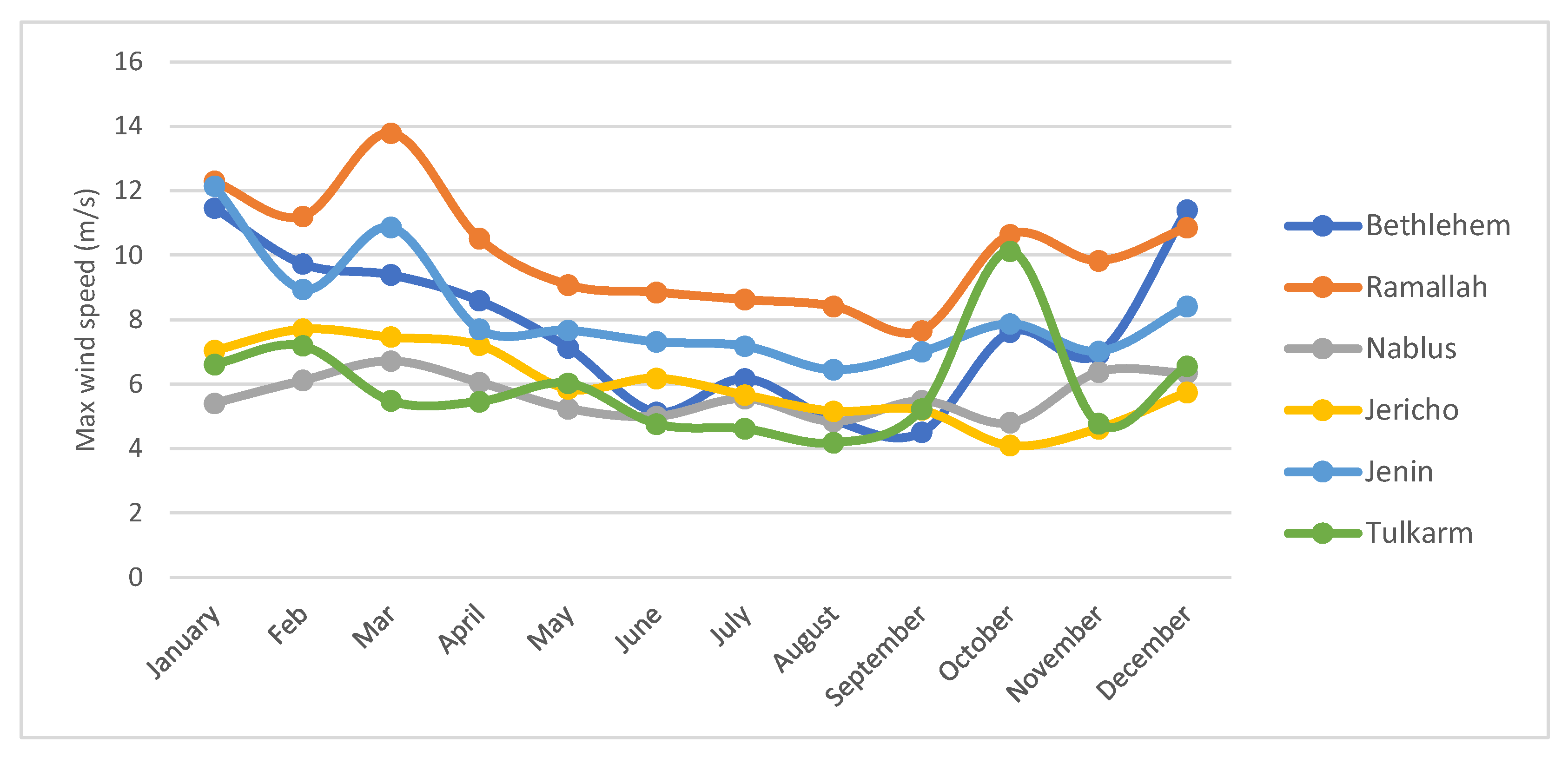

4.1. Experimental Setup and Data Collection

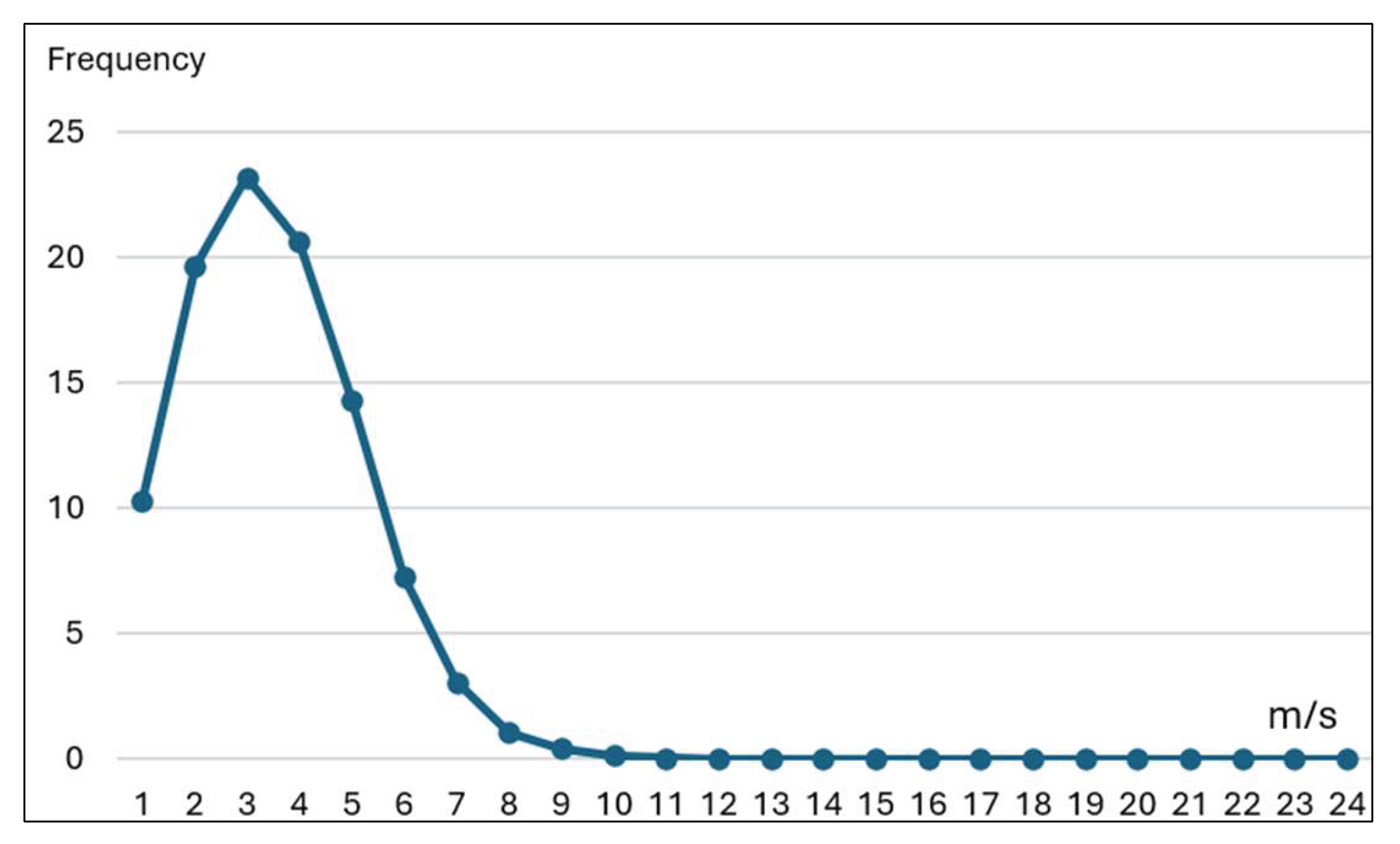

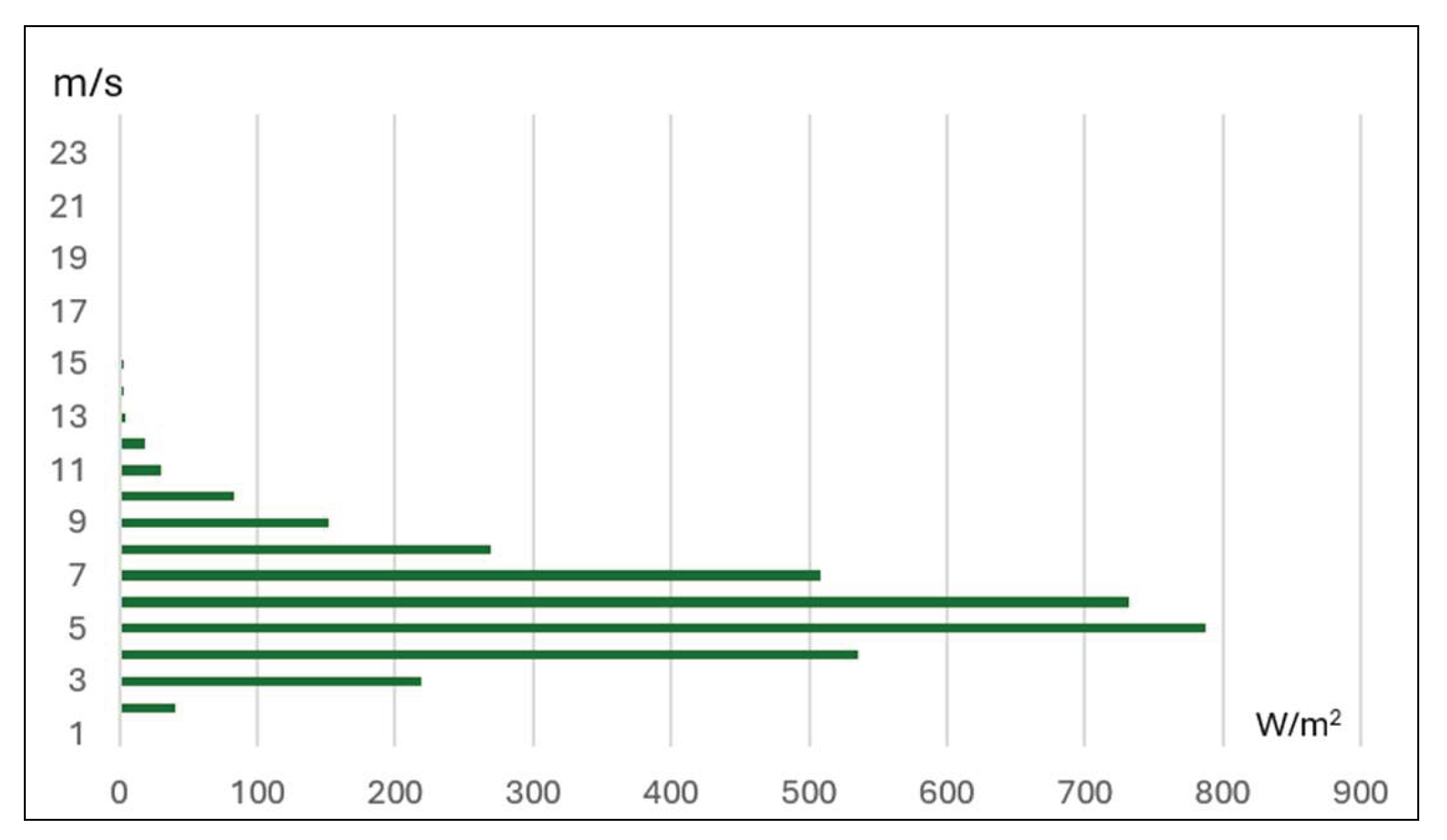

4.2. Estimation of Wind Power Density

4.3. Weibull Parameters Calculation

4.4. Goodness of Fit (GOF)

| Statistical tool | Description of the tool | Equation |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [67,110]. |

The accuracy of a model can be assessed through the RMSE, which quantifies the deviations between the values predicted by the Weibull function and the actual measurement data. | (18) |

| Chi-Square Test (X2) [85,111]. |

is utilized to examine the ratios of independent variables, specifically, the potential disparity between the anticipated frequencies and the observed frequencies of event occurrences. | (19) |

| Index of Agreement (IA) [112,113,114]. |

The IA calculates the level of accuracy in the predicted values compared to the observed values. The IA is calculated by a formula that ranges from 0 to 1. | (20) |

| Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) [115,116,117]. |

The MAPE is a statistical measure that evaluates the average absolute percentage deviation between the estimated wind power derived from the implementation of the Weibull probability function and the wind power computed from the observed data. | (21) |

| Relative Root Mean Square Error (RRMSE) [67,107,118]. | By dividing the RMSE with the mean wind power calculated from the observed values, one can obtain the RRMSE. | ×100 (22) |

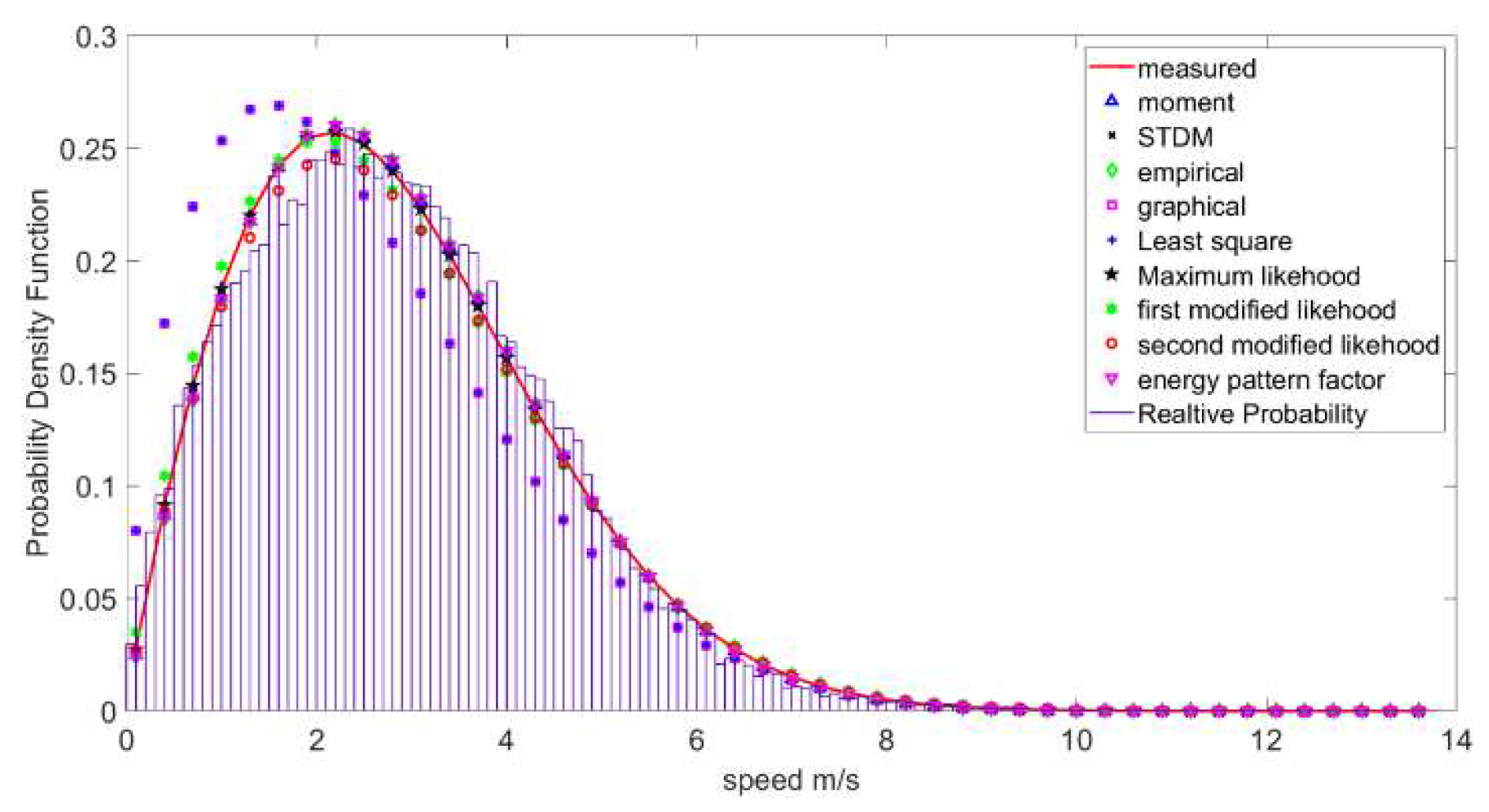

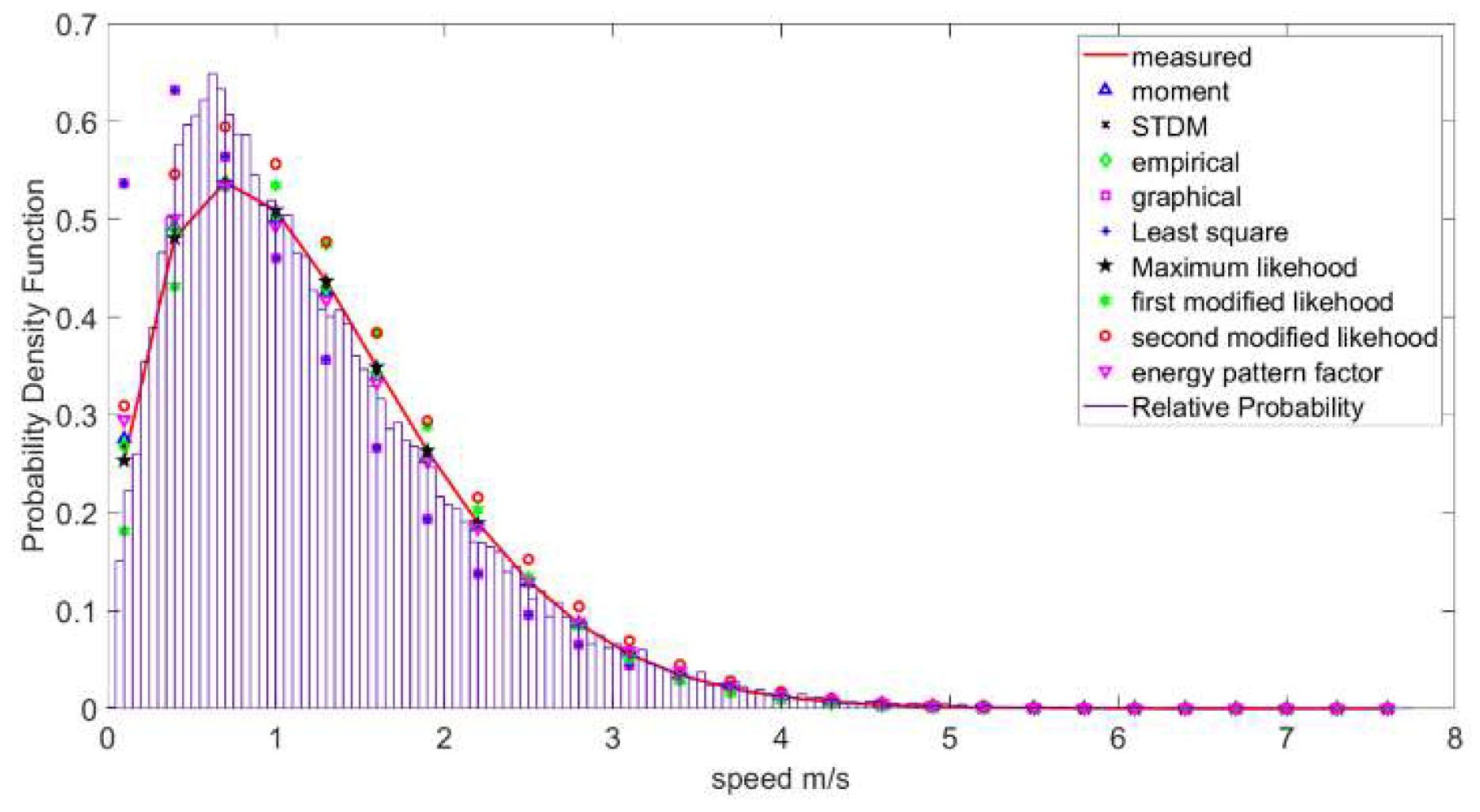

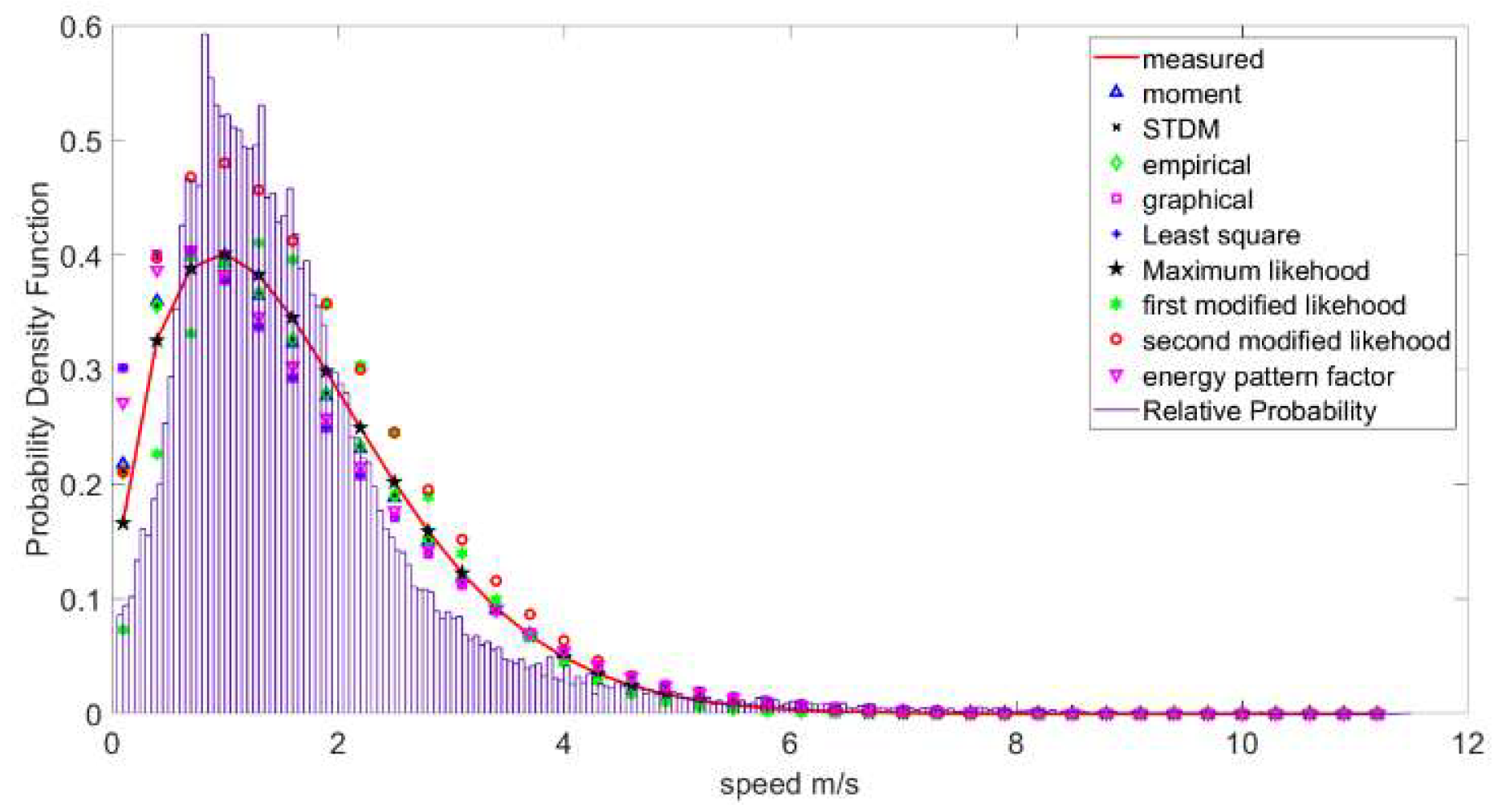

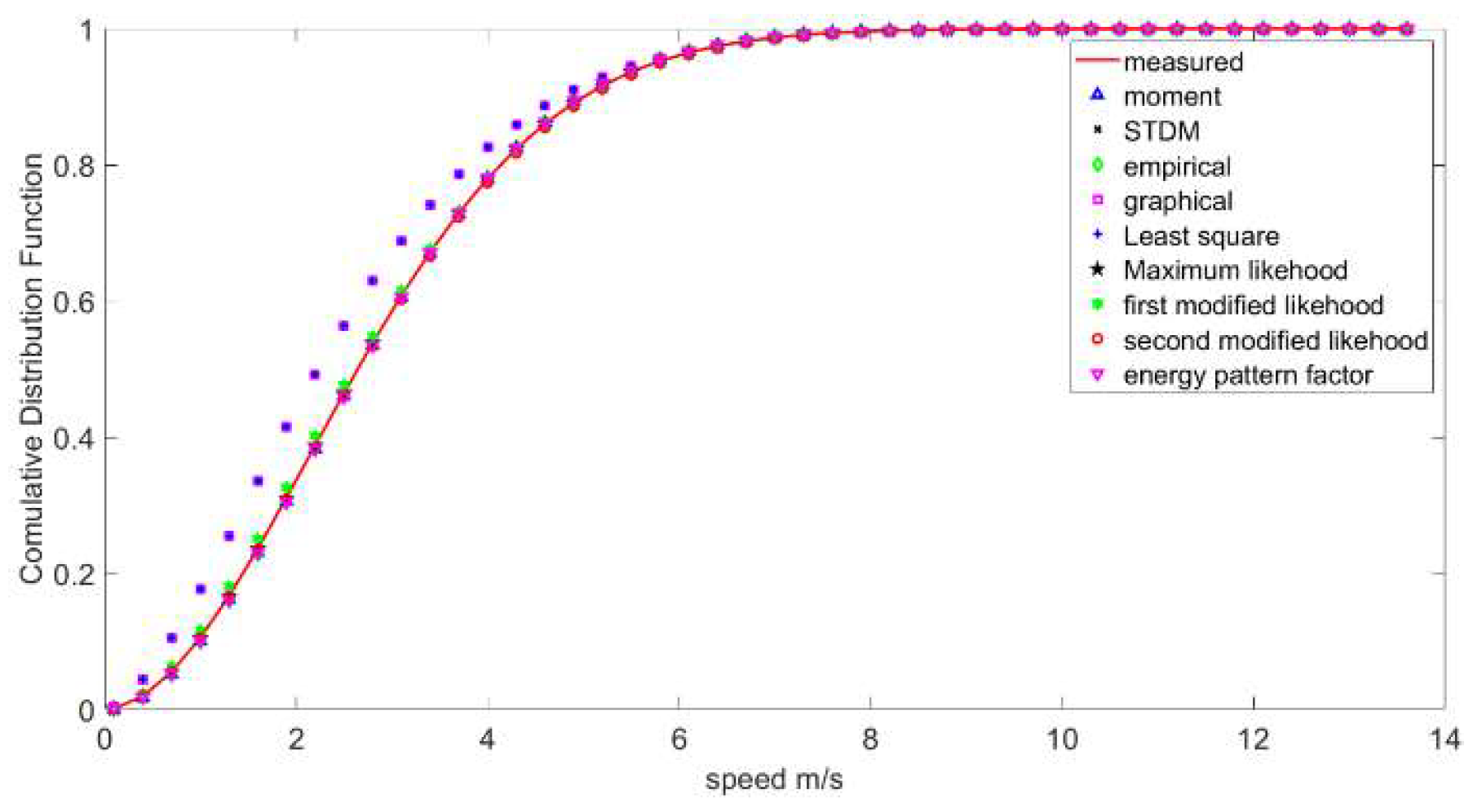

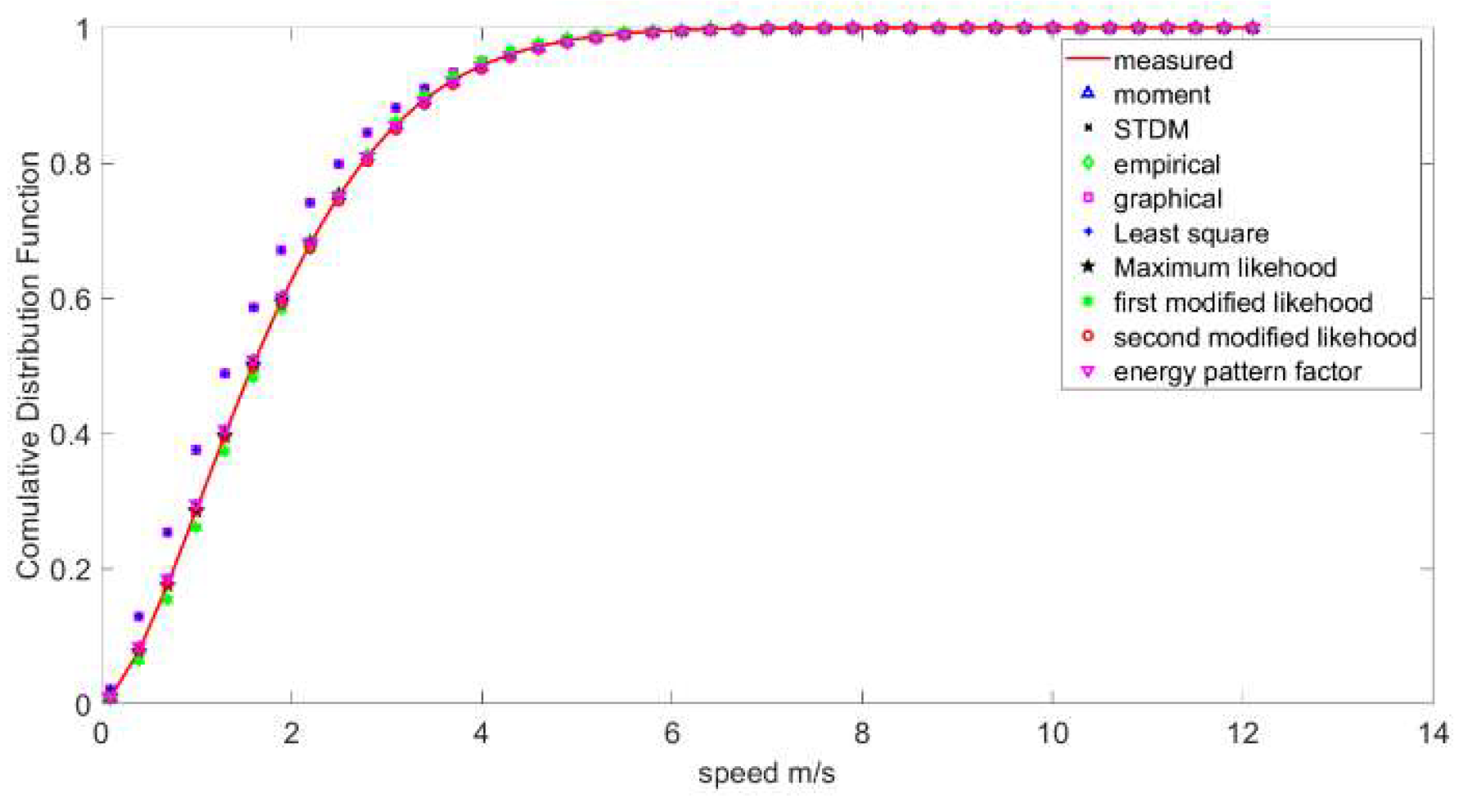

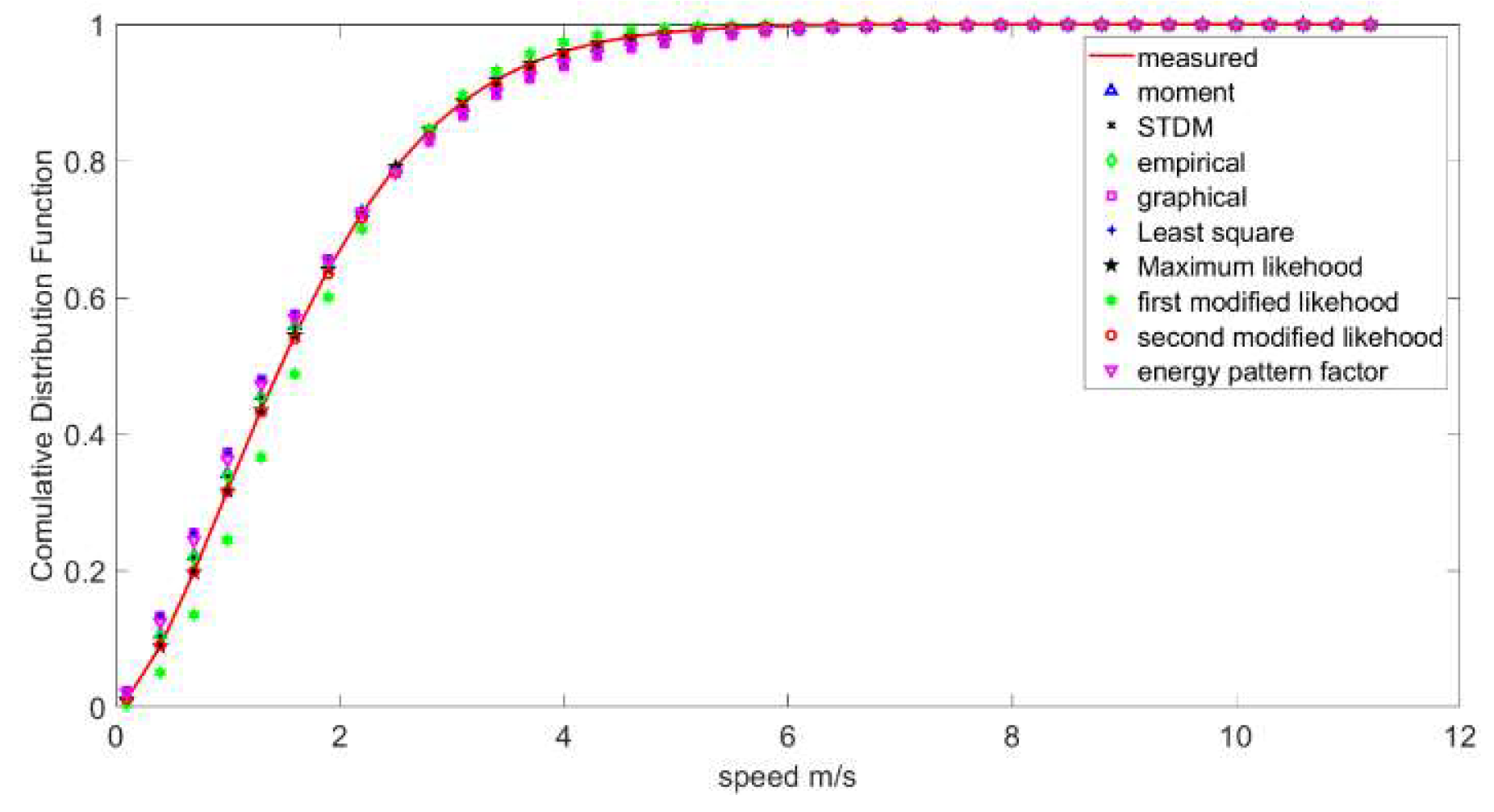

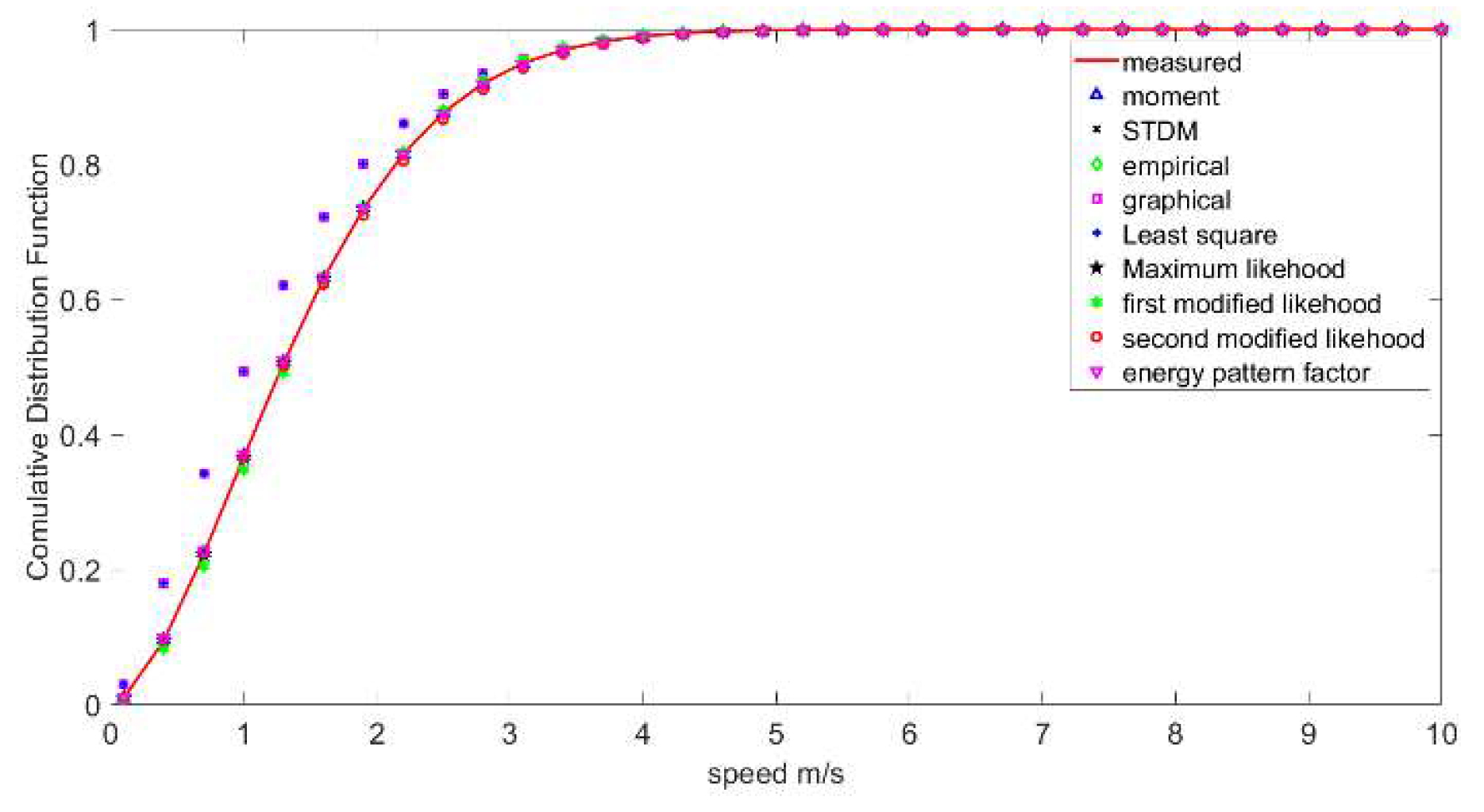

4.5. PDF and CDF Curves

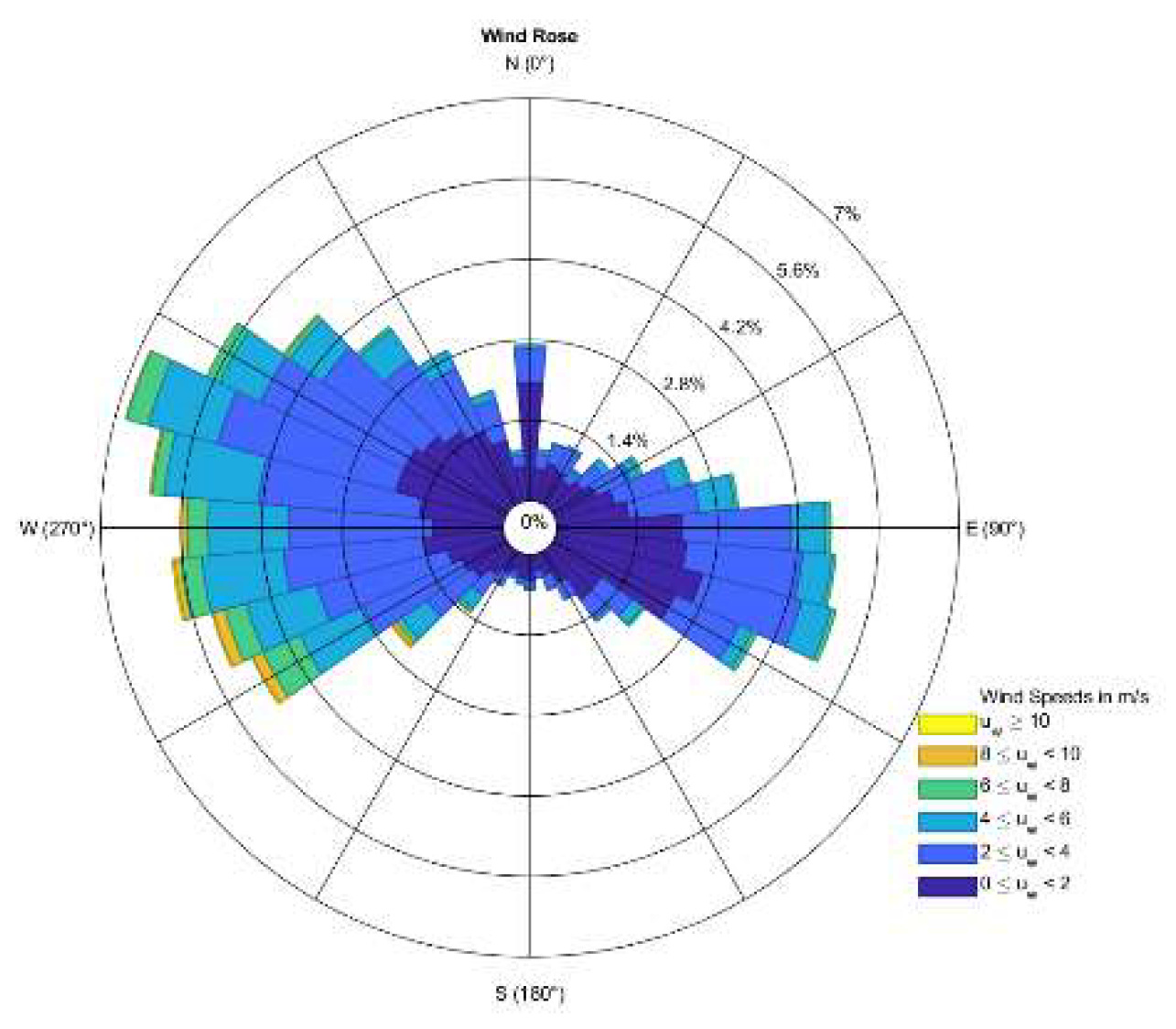

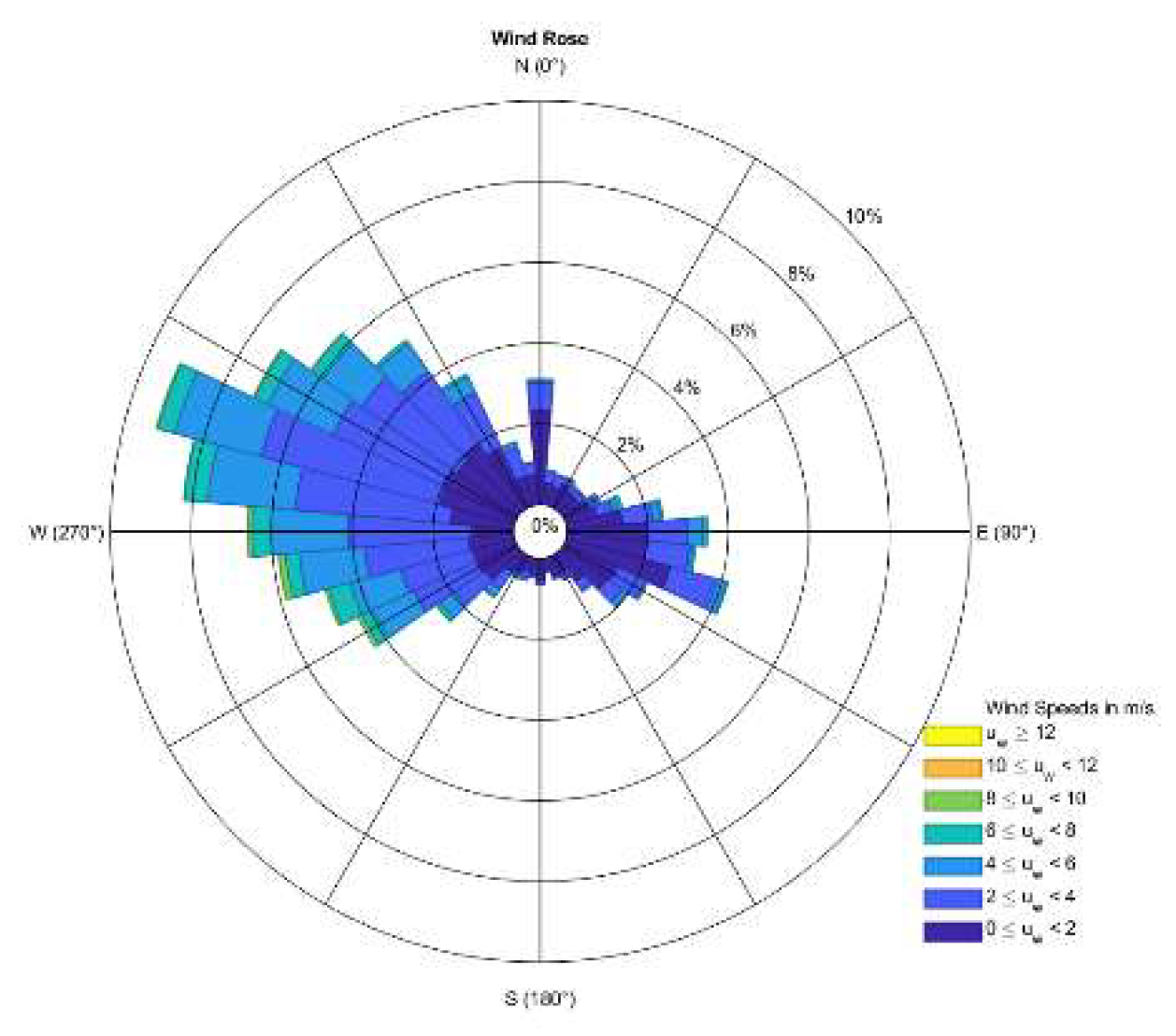

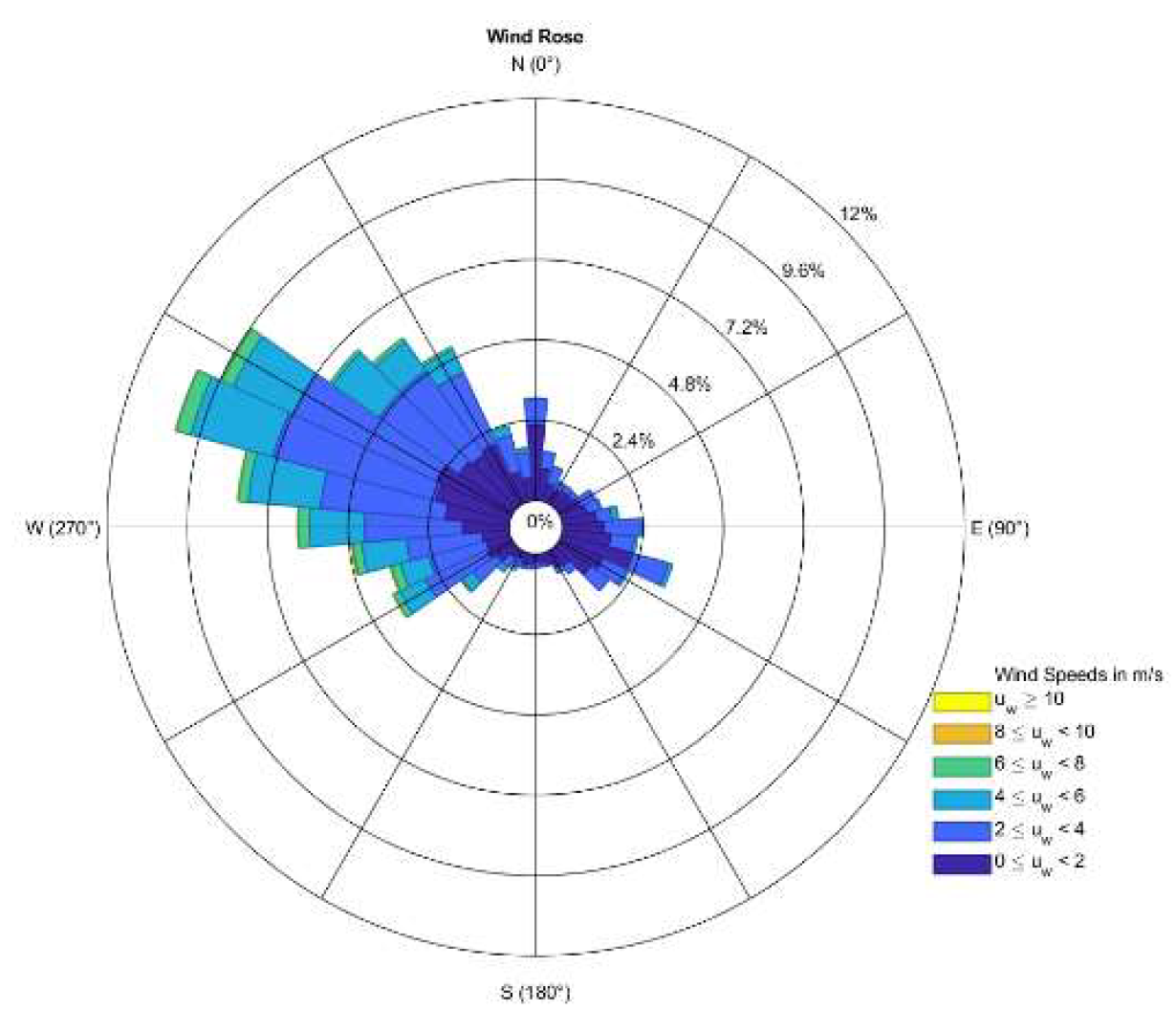

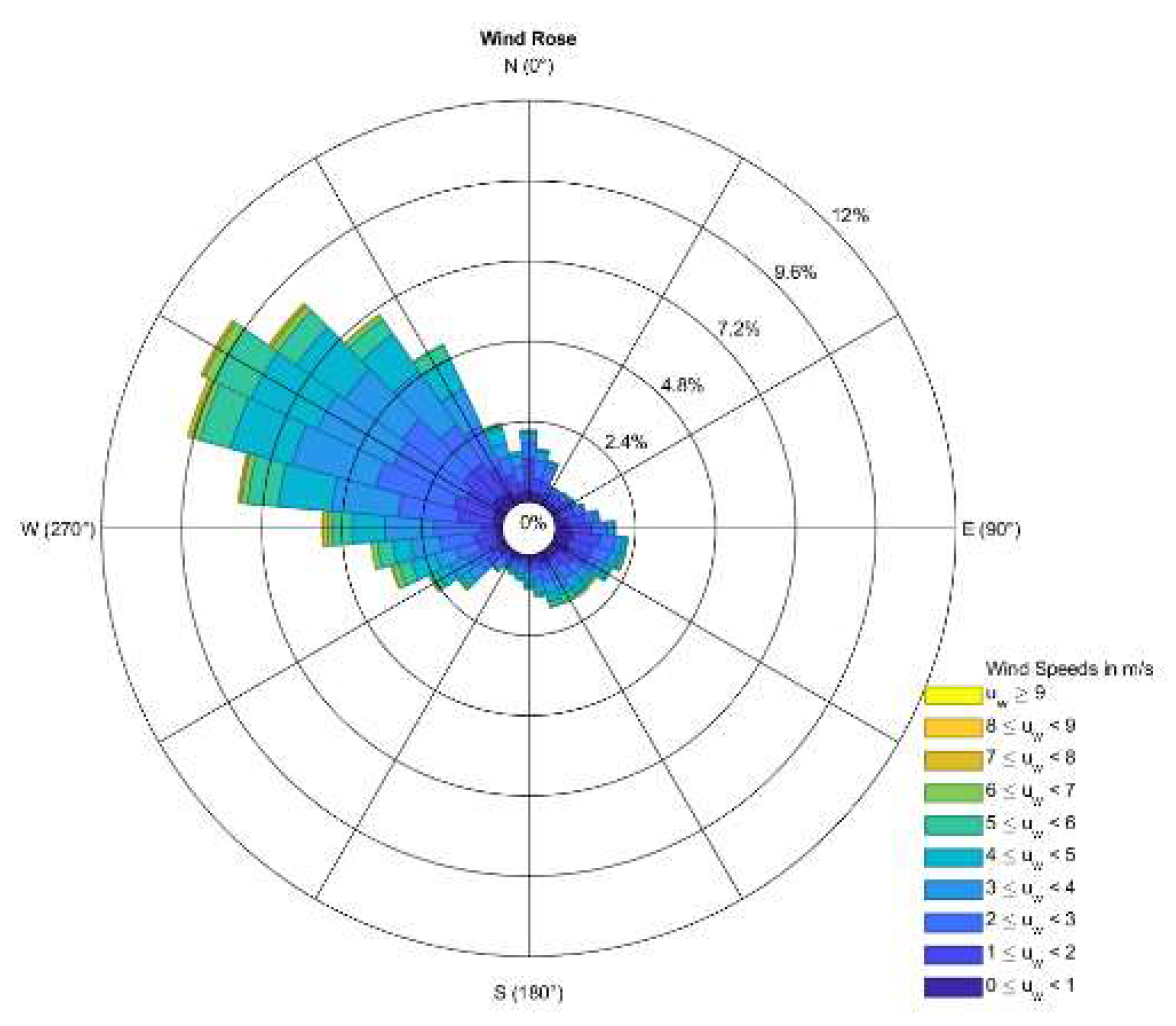

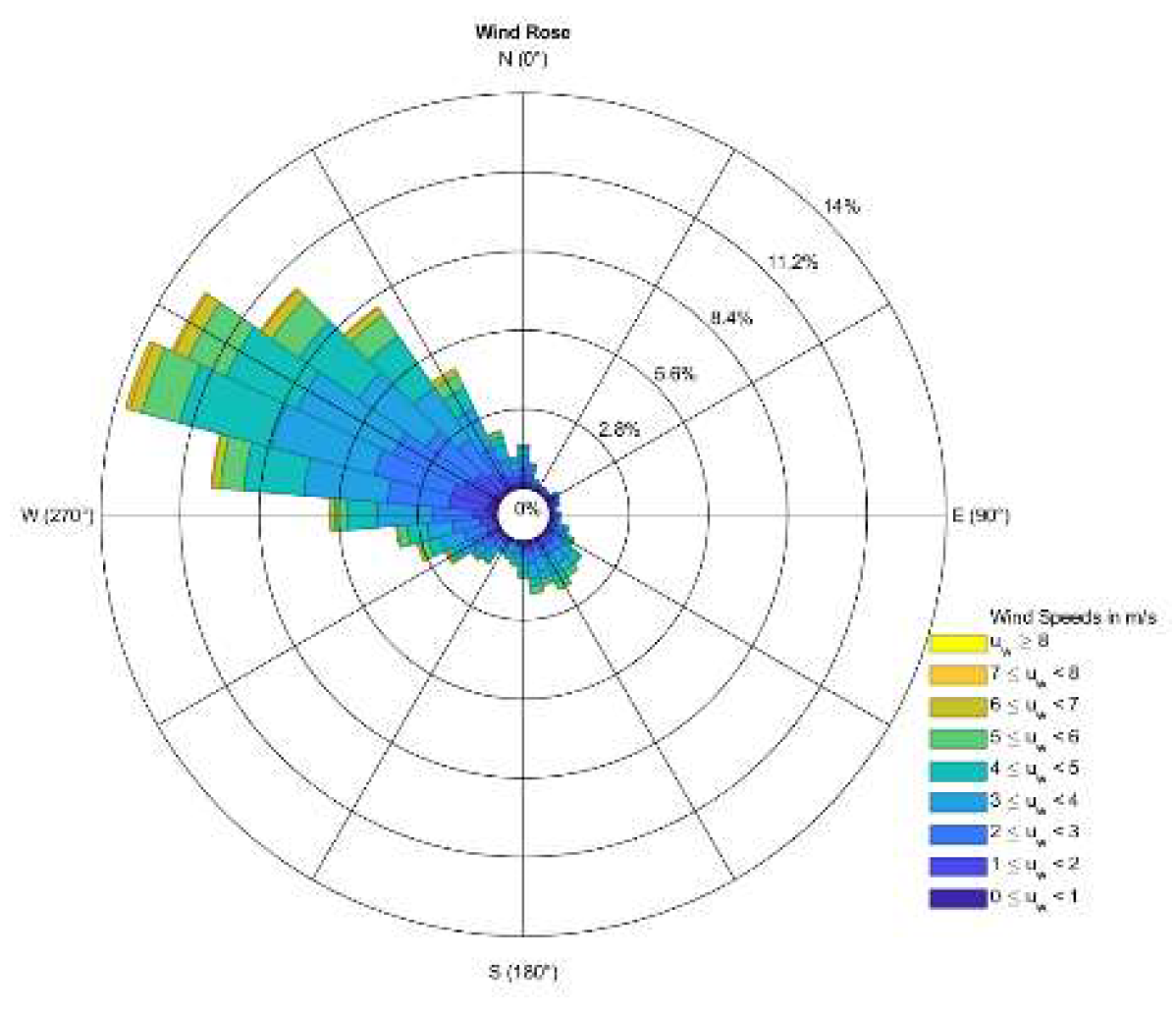

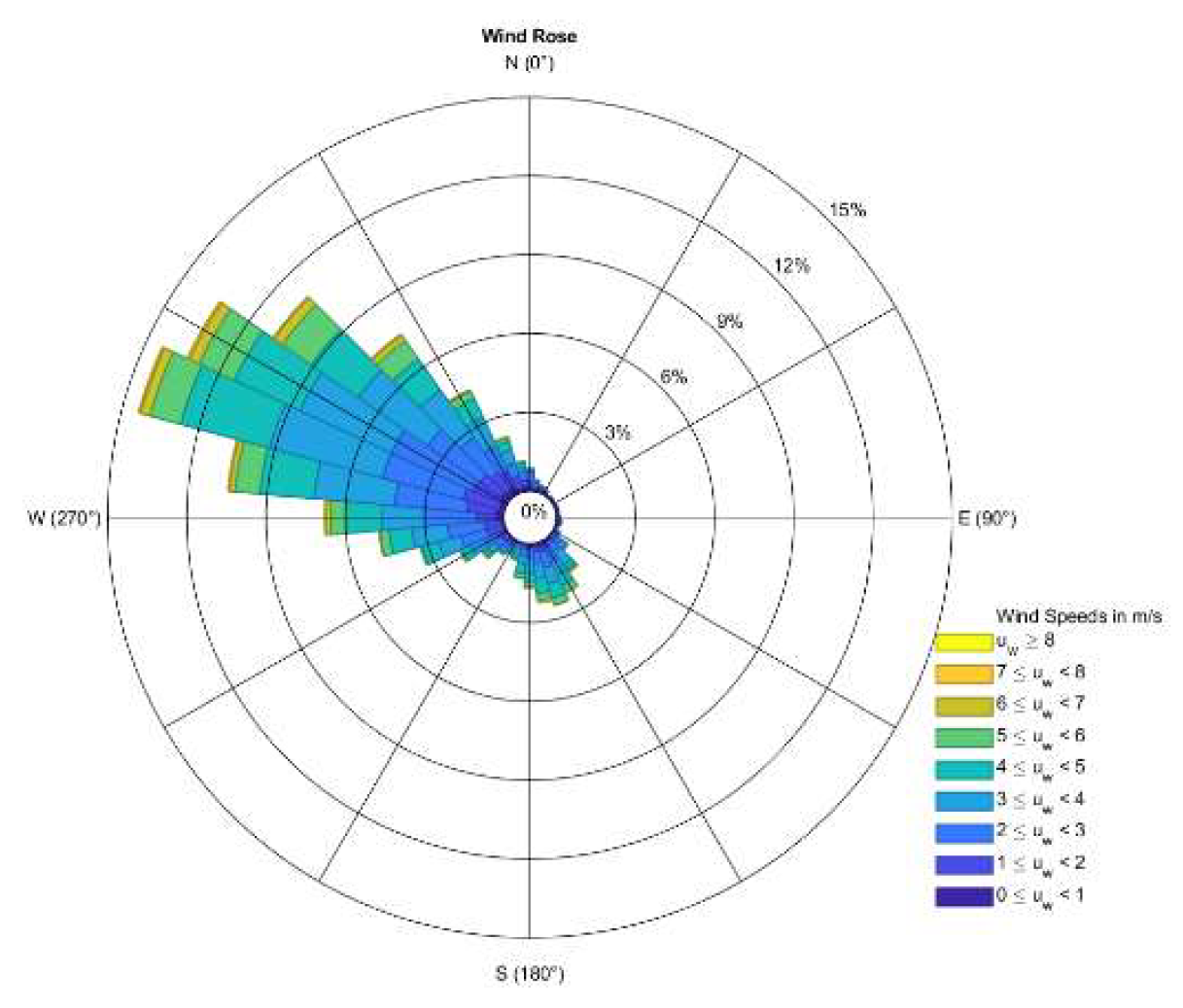

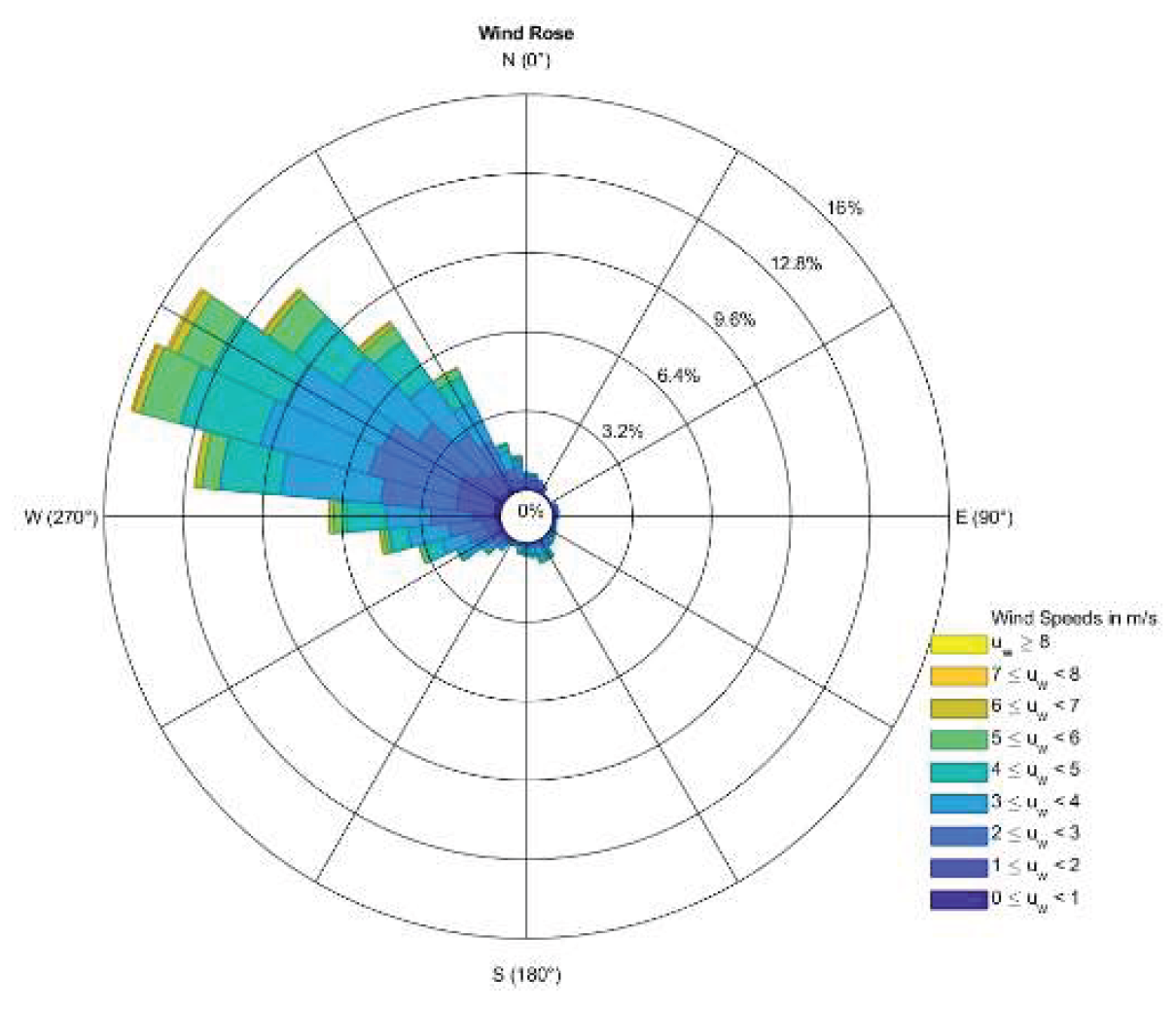

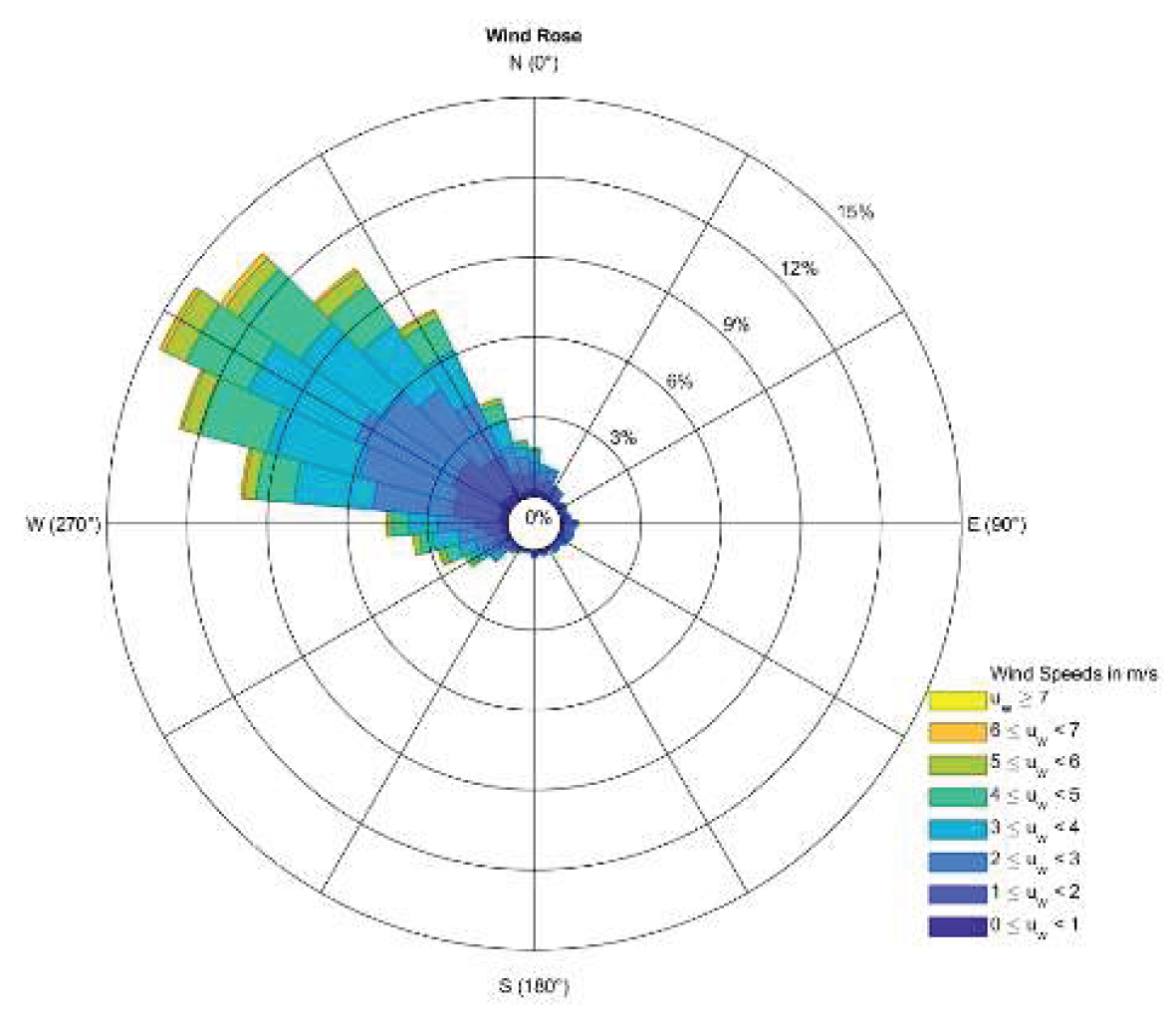

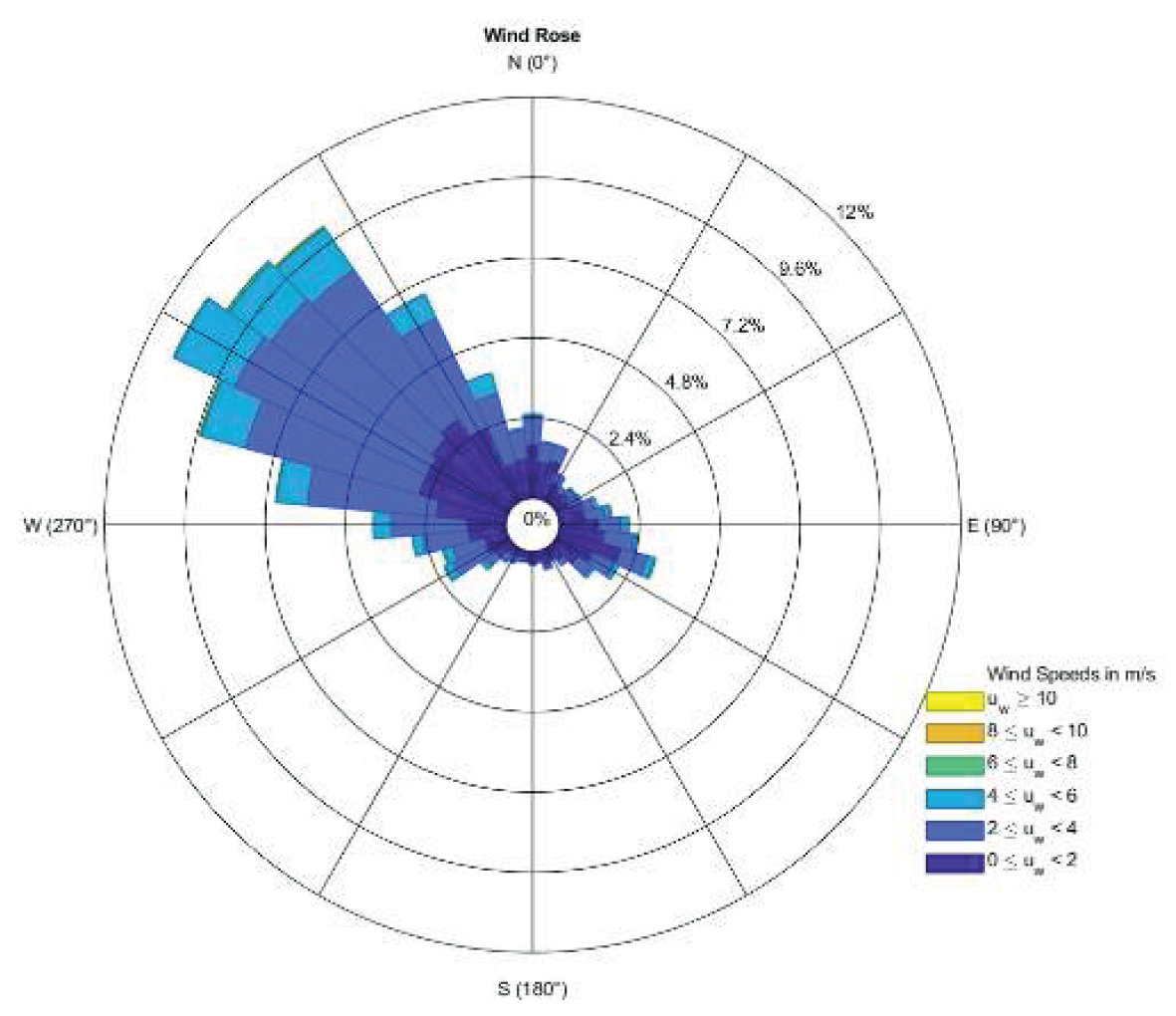

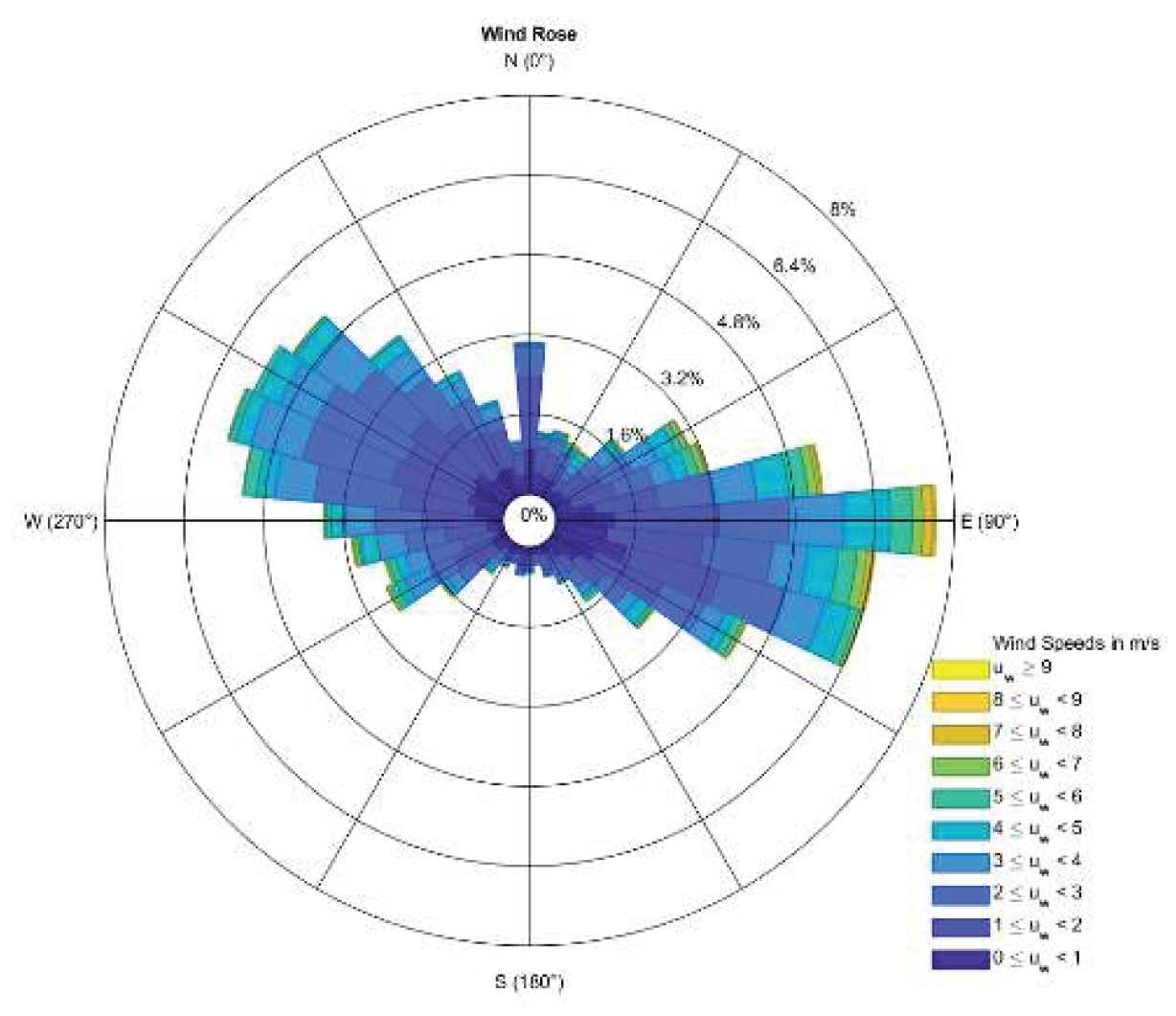

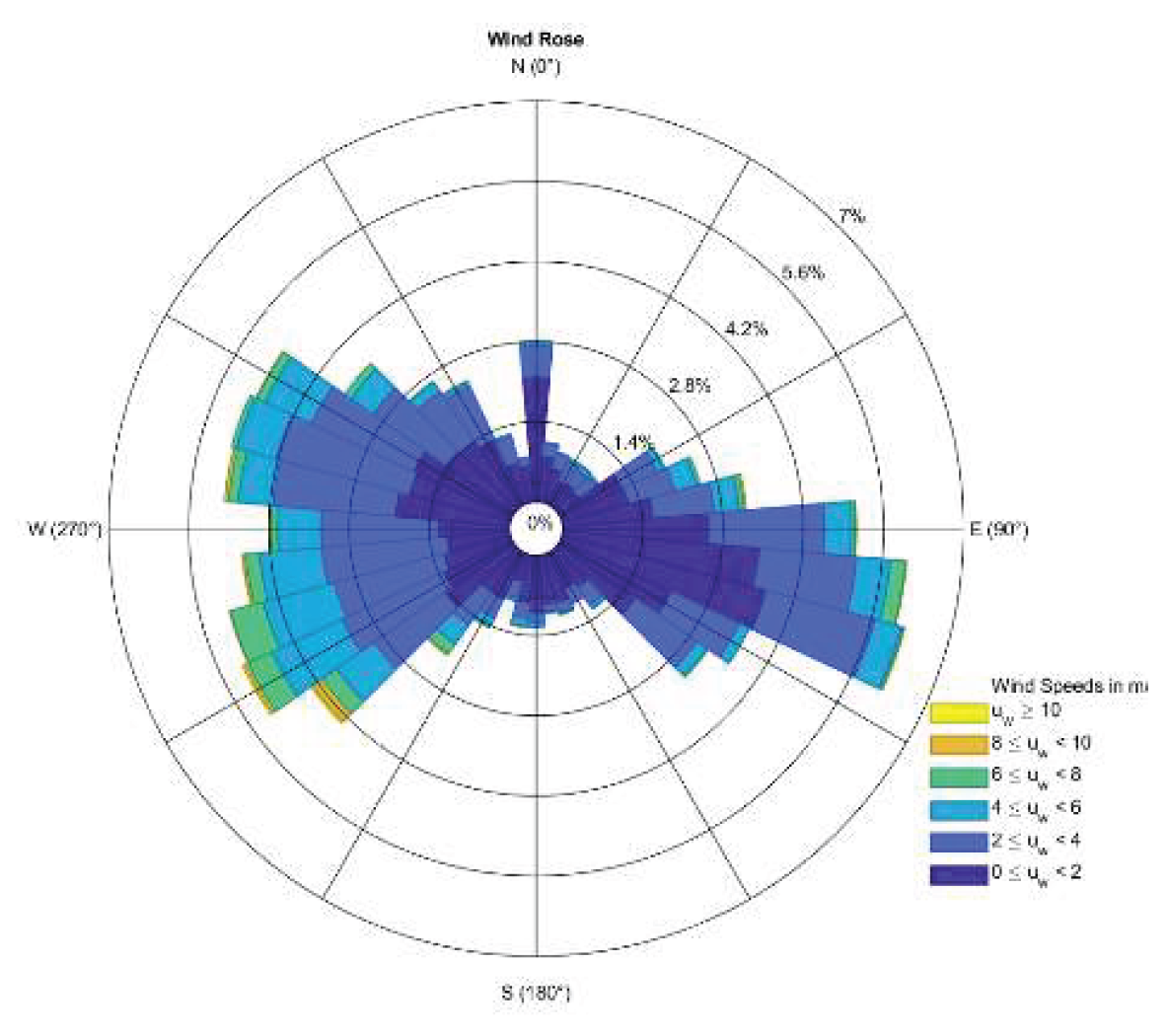

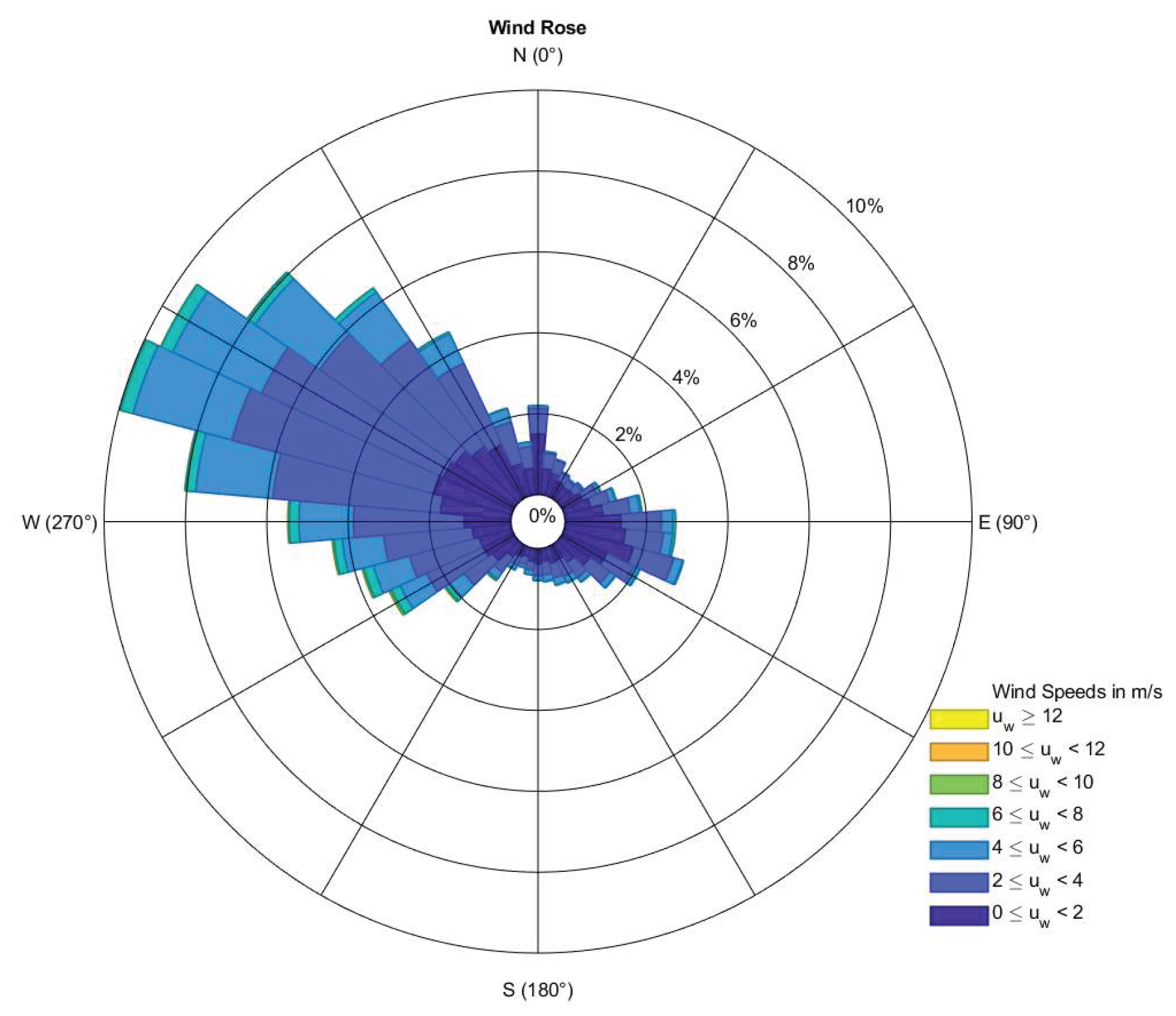

4.6. Wind Direction

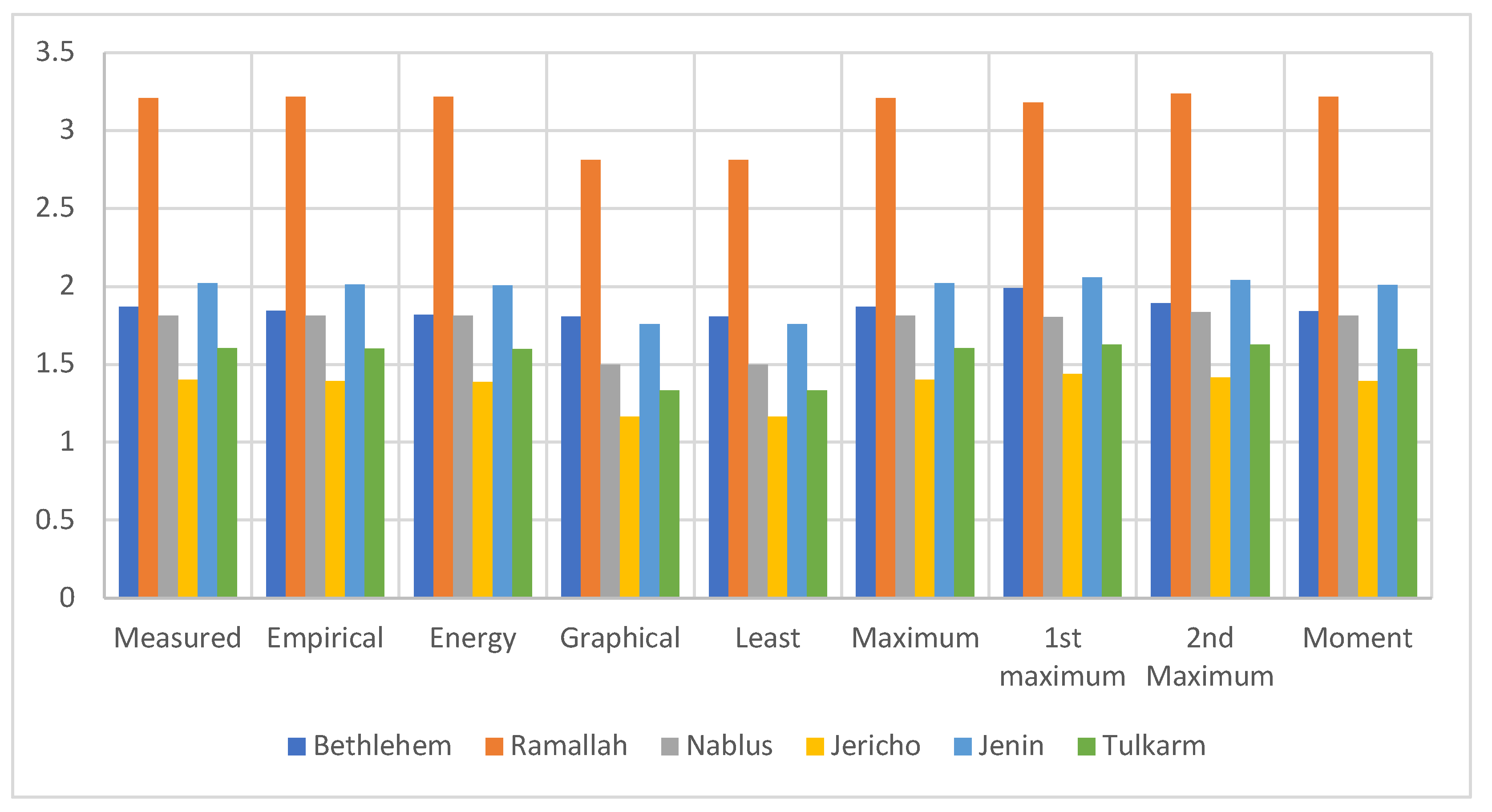

4.7. Weibull Parameters Values

4.8. Validation Using Five Statistical Tools

5.8. Wind Power Density Calculation In Ramallah City

5. Economic Payback Period

6. Conclusion

References

- Kabeyi, M.J.B. and O.A. Olanrewaju, Sustainable energy transition for renewable and low carbon grid electricity generation and supply. Frontiers in Energy research, 2022. 9: p. 743114.

- Sharma, P. and R.K. Mishra, Comprehensive study on photovoltaic cell’s generation and factors affecting its performance: A Review. Materials for Renewable and Sustainable Energy, 2025. 14(1): p. 1-28.

- Balakrishnan, P. , Global Renewable Energy Transition Challenges and Strategic Solutions, in Geopolitical Landscapes of Renewable Energy and Urban Growth. 2025, IGI Global Scientific Publishing. p. 63-96.

- Council, G.W.E. , GWEC Global Wind Report 2023. Global Wind Energy Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Badawi, A. , et al., Evaluation of wind power for electrical energy generation in the mediterranean coast of Palestine for 14 years. International Journal of Electrical & Computer Engineering (2088-8708), 2019. 9(4).

- Alsamamra, H. and J.A.H. Shoqeir, Assessment of Wind Power Potential at Eastern-Jerusalem, Palestine. 2020.

- Badawi, A. , et al., Energy and power estimation for three different locations in Palestine. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 2019. 14(3): p. 1049-56.

- de Oliveira Azevêdo, R. , et al., Identification and analysis of impact factors on the economic feasibility of wind energy investments. International Journal of Energy Research, 2021. 45(3): p. 3671-3697.

- Ouerghi, F.H. , et al., Feasibility evaluation of wind energy as a sustainable energy resource. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2024. 106: p. 227-239.

- Eliwa, M.S. , et al., Theoretical framework and inference for fitting extreme data through the modified Weibull distribution in a first-failure censored progressive approach. Heliyon, 2024. 10(14).

- Kneib, T., J. -C. Schlüter, and B. Wacker, Revisiting Maximum Log-Likelihood Parameter Estimation for Two-Parameter Weibull Distributions: Theory and Applications. Results in Mathematics, 2024. 79(6): p. 224.

- Zhang, S. , et al., Extreme wind speed distribution in a mixed wind climate. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, 2018. 176: p. 239-253.

- Badawi, A. , et al., Wind Power Potential of Southeast Brazil: Analytical Study for São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Wind Energy, 2025. 28(11): p. e70066.

- Stevens, M. and P. Smulders, The estimation of the parameters of the Weibull wind speed distribution for wind energy utilization purposes. Wind engineering, 1979: p. 132-145.

- Deaves, D. and I. Lines, On the fitting of low mean windspeed data to the Weibull distribution. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, 1997. 66(3): p. 169-178.

- Akdağ, S.A. and A. Dinler, A new method to estimate Weibull parameters for wind energy applications. Energy conversion and management, 2009. 50(7): p. 1761-1766.

- Seguro, J. and T. Lambert, Modern estimation of the parameters of the Weibull wind speed distribution for wind energy analysis. Journal of wind engineering and industrial aerodynamics, 2000. 85(1): p. 75-84.

- Mohammadi, K. , et al., Assessing different parameters estimation methods of Weibull distribution to compute wind power density. Energy Conversion and Management, 2016. 108: p. 322-335.

- Shaban, A.H., A. K. Resen, and N. Bassil, Weibull parameters evaluation by different methods for windmills farms. Energy Reports, 2020. 6: p. 188-199.

- Bingöl, F. , Comparison of Weibull estimation methods for diverse winds. Advances in Meteorology, 2020. 2020.

- Kaplan, Y.A. , Calculation of Weibull distribution parameters at low wind speed and performance analysis. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Energy, 2022. 175(4): p. 195-204.

- Sireesha, P.V. and T. Sandhya, Statistical analysis of wind power density using different mixture probability distribution functions in coastal region of Andhra Pradesh. Electrical Engineering, 2024. 106(3): p. 3061-3082.

- Huang, X., C. Wang, and S. Zhang, Research and application of a Model selection forecasting system for wind speed and theoretical power generation in wind farms based on classification and wind conversion. Energy, 2024. 293: p. 130606.

- Fanfoni, M. , et al., Weibull function to describe the cumulative size distribution of clumps formed by two-dimensional grains randomly arranged on a plane. Physical Review E, 2024. 109(4): p. 044131.

- Badawi, A. , et al., Weibull probability distribution based on four years wind speed data using nine numerical methods, in Innovation and Technological Advances for Sustainability. 2024, CRC Press. p. 193-200.

- de Souza, A. , et al., A comprehensive analysis of Weibull distribution parameter estimation methods to improve wind potential assessment. Ciência e Natura, 2024. 46: p. e87369-e87369.

- Barantiev, D. and E. Batchvarova, Wind speed profile statistics from acoustic soundings at a black sea coastal site. Atmosphere, 2021. 12(9): p. 1122.

- Abuhelwa, M. , et al., Exploring the Prevalence of Renewable Energy Practices and Awareness Levels in Palestine. Energy Science & Engineering, 2025.

- Morrar, R. , Investment in Green Infrastructure and Adaptation with Climate Change in Palestine. Priorities for Palestine’s Economy in the Midst of War, 2024: p. 111.

- Bilgili, M. and H. Alphan, Global growth in offshore wind turbine technology. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 2022. 24(7): p. 2215-2227.

- Guchhait, R. and B. Sarkar, Increasing growth of renewable energy: A state of art. Energies, 2023. 16(6): p. 2665.

- Badawi, A.S. , An analytical study for establishment of wind farms in palestine to reach the optimum electrical energy. An Analytical Study for Establishment of Wind Farms in Palestine to Reach the Optimum Electrical Energy, 2013.

- Megantoro, P. , et al., Modeling the uncertainties and active power generation of wind-solar energy with data acquisition from telemetry weather measurement. Results in Engineering, 2025. 25: p. 104392.

- Hadjipetrou, S. and P. Kyriakidis, High-Resolution Wind Speed Estimates for the Eastern Mediterranean Basin: A Statistical Comparison Against Coastal Meteorological Observations. Wind, 2024. 4(4): p. 311-341.

- Hamada, S. and A. Ghodieh, Mapping of solar energy potential in the west bank, Palestine using Geographic Information Systems. Papers in Applied Geography, 2021. 7(3): p. 256-273.

- Yaseen, E.B. , Renewable energy applications in Palestine. 2009.

- Donkoh, C. , Optimal design of grid connected pvwind power generation for urban healthcare facility using homer environment. 2022, University of Education Winneba.

- Liu, J., G. Xiong, and P.N. Suganthan, Differential evolution-based mixture distribution models for wind energy potential assessment: A comparative study for coastal regions of China. Energy, 2025. 321: p. 135151.

- Azad, A.K., M. G. Rasul, and T. Yusaf, Statistical diagnosis of the best Weibull methods for wind power assessment for agricultural applications. Energies, 2014. 7(5): p. 3056-3085.

- Habali, S. , et al., Wind as an alternative source of energy in Jordan. Energy Conversion and Management, 2001. 42(3): p. 339-357.

- Juaidi, A. , et al., An overview of renewable energy strategies and policies in Palestine: Strengths and challenges. Energy for sustainable development, 2022. 68: p. 258-272.

- Salah, S., H. R. Alsamamra, and J.H. Shoqeir, Exploring wind speed for energy considerations in eastern Jerusalem-Palestine using machine-learning algorithms. Energies, 2022. 15(7): p. 2602.

- Abuhomos, M. , et al., The effect of geopolitical factors on local energy system performance: Examining the case of Palestine. Energy Strategy Reviews, 2025. 58: p. 101681.

- Salamanca, O.J. Hooked on electricity: The charged political economy of electrification in Palestine. in New Direction in Palestine Studies Workshop, Brown University. 2014.

- Badawi, A.S., et al. Maximum power point tracking controller technique using permanent magnet synchronous generator. in 2021 6th IEEE International Conference on Recent Advances and Innovations in Engineering (ICRAIE). 2021. IEEE.

- Mahela, O.P. , et al., Comprehensive overview of low voltage ride through methods of grid integrated wind generator. Ieee Access, 2019. 7: p. 99299-99326.

- Mostafa, M.A., E. A. El-Hay, and M.M. Elkholy, An overview and case study of recent low voltage ride through methods for wind energy conversion system. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2023. 183: p. 113521.

- Badawi, A. , et al., Optimizing Low-Voltage Ride-Through in DFIG Wind Turbines via QPQC-Based Predictive Control for Grid Compliance. International Journal of Robotics and Control Systems, 2025. 5(1): p. 86-104.

- Srivastava, P.K., A.N. Tiwari, and S.N. Singh, Impacts of Wind Energy Integration to the Utility Grid and Grid Codes: A Review. Recent Advances in Electrical & Electronic Engineering (Formerly Recent Patents on Electrical & Electronic Engineering), 2020. 13(4): p. 446-469.

- Tsili, M. and S. Papathanassiou, A review of grid code technical requirements for wind farms. IET Renewable power generation, 2009. 3(3): p. 308-332.

- Huang, M. , et al., Bifurcation and large-signal stability analysis of three-phase voltage source converter under grid voltage dips. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, 2017. 32(11): p. 8868-8879.

- Badawi, A. , et al., Wind energy production using novel HCS algorithm to reach MPPT for small-scale wind turbines under rapid change wind speed, in Innovation and Technological Advances for Sustainability. 2024, CRC Press. p. 183-192.

- Ahmed Badawi, H.A., I. Elzein, and A.M. Zyoud, Performance Evaluation of Incremental Conductance and Adaptive HCS MPPT Algorithms for WECS.

- Badawi, A., et al. Robust adaptive HCS MPPT algorithm-based wind generation system using power prediction mode. in 2024 IEEE 8th Energy Conference (ENERGYCON). 2024. IEEE.

- Badawi, A. , et al., Boost efficiency performance through the enhancement of duty cycle based MPPT algorithm. International Journal of Applied, 2025. 14(3): p. 541-550.

- Azareer, A. , Optimal Sizing and Allocation of DG Techniques for Enhancing Active Distribution Network in Palestine. 2023.

- Medina, C., C. R.M. Ana, and G. González, Transmission grids to foster high penetration of large-scale variable renewable energy sources–A review of challenges, problems, and solutions. International Journal of Renewable Energy Research (IJRER), 2022. 12(1): p. 146-169.

- Blarke, M.B. and B.M. Jenkins, SuperGrid or SmartGrid: Competing strategies for large-scale integration of intermittent renewables? Energy Policy, 2013. 58: p. 381-390.

- Badawi, A.S. , et al., Practical electrical energy production to solve the shortage in electricity in palestine and pay back period. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 2019. 9(6): p. 4610.

- Nassar, Y.F. , et al., Renewable energy potential in the State of Palestine: Proposals for sustainability. Renewable Energy Focus, 2024. 49: p. 100576.

- Maghalseh, M. , et al. Investigation of Grid-Tied Photovoltaic Power Plant on Medium-Voltage Feeder: Palestine Polytechnic University Case Study. in Solar. 2025. MDPI.

- Ahmed, M., S. Mirsaeidi, and M.A. Koondhar, Mitigation Uncertainty Problems of Renewable Energy Resources with Efficient Integration of Hybrid solar PV/Wind system into Power Networks.

- Wu, D. , et al., Grid integration of offshore wind power: Standards, control, power quality and transmission. IEEE Open Journal of Power Electronics, 2024. 5: p. 583-604.

- Rantissi, T. , et al., Transforming the water-energy nexus in Gaza: A systems approach. Global Challenges, 2024. 8(5): p. 2300304.

- Garba, B.M.P. , et al., Energy efficiency in public buildings: Evaluating strategies for tropical and temperate climates. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 2024. 23(03): p. 409-421.

- Badawi, A. , et al., Extensive Numerical Analysis of PDF Parameters for Wind Energy in Brazil: A Study Across 27 Cities for 60 Years Wind Speed. IEEE Access, 2025.

- Yadav, A.K. , et al., Comparative analysis of Weibull parameters estimation for wind power potential assessments. Results in Engineering, 2024. 23: p. 102300.

- ul Haq, M.A., S. Hashmi, and M. Aslam, Marshall-Olkin length biased exponential distribution for wind speed analysis alternative to Weibull distribution. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 2024. 10(1): p. 1095-1108.

- Shambira, N., P. Mukumba, and G. Makaka, Assessing the Wind Energy Potential: A Case Study in Fort Hare, South Africa, Using Six Statistical Distribution Models. Applied Sciences, 2025. 15(5): p. 2778.

- Chen, Y. , et al., Comparative analysis of offshore wind resources and optimal wind speed distribution models in China and Europe. Energies, 2025. 18(5): p. 1108.

- Okakwu, I. , et al., Performance evaluation of ten numerical methods for Weibull distribution parameter estimation applied to Nigerian wind speed data. Scientia Africana, 2024. 23(2): p. 427-444.

- Badawi, A.S. , et al., Weibull probability distribution of wind speed for gaza strip for 10 years. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 2019. 892: p. 284-291.

- Chakraborty, U., D. S. Boning, and C.V. Thompson, Bound-Constrained Expectation Maximization for Weibull Competing-Risks Device Reliability. IEEE Transactions on Device and Materials Reliability, 2024.

- dos Santos, F.S. , et al., Brazilian wind energy generation potential using mixtures of Weibull distributions. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024. 189: p. 113990.

- Shambira, N., L. Luvatsha, and P. Mukumba, Comparative Analysis of Five Numerical Methods and the Whale Optimization Algorithm for Wind Potential Assessment: A Case Study in Whittlesea, Eastern Cape, South Africa. Processes, 2025. 13(5): p. 1344.

- Shirzadi, N. , et al., Smart urban wind power forecasting: Integrating weibull distribution, recurrent neural networks, and numerical weather prediction. Energies, 2023. 16(17): p. 6208.

- Duman, N., H. İ. Acar, and L. Ertürk, Estimation of wind power potential in sivas cumhuriyet university campus using various probability density functions. The European Physical Journal Plus, 2025. 140(4): p. 1-15.

- Badawi, A.S., et al. The simplest estimation method of weibull probability distribution parameters. in 2021 6th IEEE International Conference on Recent Advances and Innovations in Engineering (ICRAIE). 2021. IEEE.

- Gómez, Y.M. , et al., An in-depth review of the Weibull model with a focus on various parameterizations. Mathematics, 2023. 12(1): p. 56.

- Ahmad, Z. , et al., On predictive modeling using a new flexible Weibull distribution and machine learning approach: Analyzing the COVID-19 data. Mathematics, 2022. 10(11): p. 1792.

- Jerez, D. , et al., Operator norm-based determination of failure probability of nonlinear oscillators with fractional derivative elements subject to imprecise stationary Gaussian loads. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 2024. 208: p. 111043.

- Chen, X. , et al., A novel derivative search political optimization algorithm for multi-area economic dispatch incorporating renewable energy. Energy, 2024. 300: p. 131510.

- Ezeah, S. , et al., On a Variant Weibull-Weibull Distribution: Theory and Properties. Statistics, 2024. 12(5): p. 401-408.

- Marzouk, O.A. , Wind Speed Weibull Model Identification in Oman, and Computed Normalized Annual Energy Production (NAEP) From Wind Turbines Based on Data From Weather Stations. Engineering Reports, 2025. 7(3): p. e70089.

- Mrabet, N., et al. Enhancing Wind Power Estimation for Dakhla, Morocco: A Comparative Exploration of Four Numerical Methods Leveraging the Weibull Distribution. in 2024 International Conference on Global Aeronautical Engineering and Satellite Technology (GAST). 2024. IEEE.

- Shi, H. , et al., Wind speed distributions used in wind energy assessment: a review. Frontiers in Energy Research, 2021. 9: p. 769920.

- Aljeddani, S.M. and M. Mohammed, A novel approach to Weibull distribution for the assessment of wind energy speed. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 2023. 78: p. 56-64.

- Vu, C.-C. and H.-H. Tran, Performance analysis of methods to estimate Weibull parameters for the compressive strength of concrete. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 2023. 19: p. e02330.

- Liu, K. , Moment Monotonicity of Weibull, Gamma and Log-normal Distributions. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2502.11366, 2025.

- Badawi, A. , et al., Data bank: nine numerical methods for determining the parameters of weibull for wind energy generation tested by five statistical tools. International Journal of Power Electronics and Drive Systems (IJPEDS), 2021.

- Kang, S. , et al., Comparison of different statistical methods used to estimate Weibull parameters for wind speed contribution in nearby an offshore site, Republic of Korea. Energy Reports, 2021. 7: p. 7358-7373.

- Alanazi, M.A. , et al., Wind energy assessment using Weibull distribution with different numerical estimation methods: a case study. Emerg. Sci. J., 2023. 7(6): p. 2260-2278.

- Okakwu, I. , et al., Comparative assessment of numerical techniques for Weibull parameters’ estimation and the performance of wind energy conversion systems in Nigeria. IIUM Engineering Journal, 2023. 24(1): p. 138-157.

- Abdelhadi, H. , et al., Innovative hierarchical control of multiple microgrids: Cheetah meets PSO. Energy Reports, 2024. 11: p. 4967-4981.

- Aziz, A. , et al., Influence of Weibull parameters on the estimation of wind energy potential. Sustainable Energy Research, 2023. 10(1): p. 5.

- Ikbal, N.A.M., S. A. Halim, and N. Ali, Estimating Weibull parameters using maximum likelihood estimation and ordinary least squares: Simulation study and application on meteorological data. Stat, 2022. 10(2): p. 269-292.

- Emam, W. , On statistical modeling using a new version of the flexible Weibull model: Bayesian, maximum likelihood estimates, and distributional properties with applications in the actuarial and engineering fields. Symmetry, 2023. 15(2): p. 560.

- Liang, W. , et al., Monitoring ai-modified content at scale: A case study on the impact of chatgpt on ai conference peer reviews. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2403.07183, 2024.

- Puthenpura, S. and N.K. Sinha, Modified maximum likelihood method for the robust estimation of system parameters from very noisy data. Automatica, 1986. 22(2): p. 231-235.

- Cohen, C.A. and B. Whitten, Modified maximum likelihood and modified moment estimators for the three-parameter Weibull distribution. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods, 1982. 11(23): p. 2631-2656.

- Yaniktepe, B. , et al., Comparison of eight methods of Weibull distribution for determining the best-fit distribution parameters with wind data measured from the met-mast. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023. 30(4): p. 9576-9590.

- Deji, A., S. Khan, and M.H. Habaebi, Mathematical Differential Analysis of Atlantic Ocean Wind to Electrical Energy Generation in Lekki Peninsular Lagos Nigeria. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research (IJFMR). 6(3): p. 1-28.

- Doungpan, S., V. Chatchavong, and K. Janchitrapongvej. Applicability of Weibull distribution in Generating Model for Evaluating Lifespan Closed Circuit Television System (CCTV). in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2023. IOP Publishing.

- Mdee, O.J. , Performance evaluation of Weibull analytical methods using several empirical methods for predicting wind speed distribution. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects, 2025. 47(1): p. 1626-1649.

- Bulut, A. and O. Bingöl, Weibull parameter estimation methods on wind energy applications-a review of recent developments. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 2024. 155(10): p. 9157-9184.

- Krit, M., O. Gaudoin, and E. Remy, Goodness-of-fit tests for the Weibull and extreme value distributions: A review and comparative study. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, 2021. 50(7): p. 1888-1911.

- Safari, M.A.M. , et al., Robust estimation of the three parameter Weibull distribution for addressing outliers in reliability analysis. Scientific Reports, 2025. 15(1): p. 11516.

- Badawi, A.S.A. , Maximum power point tracking control scheme for small scale wind turbine. 2019, PhD Thesis.

- Dawlah, A. and A.S. Alghamdi, A New Extended Weibull Distribution: Estimation Methods and Applications in Engineering, Physics, and Medicine. Mathematics, 2025. 13(20): p. 3262.

- El-Bayoumi, M.A. , A Direct Iterative Technique for Weibull Parameters Estimation Optimized for lowest Root Mean Square Error. Journal of International Society for Science and Engineering, 2024. 6(2): p. 47-51.

- Ige, P. and R. Israel, Diameter distribution, maximum likelihood estimation, probability distribution function, generalized Weibull, 3-parameter gamma, parameter estimation. Nigeria Agricultural Journal, 2024. 55(3): p. 257-268.

- Wu, S.-F. and K.-Y. Chiang, Assessment of the overall lifetime performance index of Weibull products in multiple production lines. Mathematics, 2024. 12(4): p. 514.

- Li, Z., H. Fu, and J. Guo, Reliability Assessment of a Series System with Weibull-Distributed Components Based on Zero-Failure Data. Applied Sciences, 2025. 15(5): p. 2869.

- He, Y., et al. Reliability Assessment for Wind Turbine under Index Weight and Failure of Subsystem. in 2024 6th International Conference on Power and Energy Technology (ICPET). 2024. IEEE.

- Kaplan, A.G. and Y.A. Kaplan, Using of the Weibull distribution in developing global solar radiation forecasting models. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy, 2024. 43(4): p. e14380.

- Wang, S. , et al., Constant-Stress ADTs and Weibull-Based Lifetime Estimation of LED Lamp. Journal of Electronic Materials, 2024. 53(6): p. 2903-2909.

- Muhamad Jamil, S.A., J. Lai, and M.A.A. Abdullah, Measuring the performances of covariates using exponential survival analysis with partly-interval censored simulation data. 2024.

- Eidous, O. and H. Maqableh, On Inference of Weitzman Overlapping Coefficient in Two Weibull Distributions. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2409.02950, 2024.

- Wang, Z. and W. Liu, Wind energy potential assessment based on wind speed, its direction and power data. Scientific reports, 2021. 11(1): p. 16879.

- Tiwari, U.D., N. S. Ghaisas, and K. Mitra, Wind Farm Performance Assessment Using CFD: Key Factors, SOWFA, and Yaw Misalignment Case Study, in Optimization, Uncertainty and Machine Learning in Wind Energy Conversion Systems. 2025, Springer. p. 79-104.

- Elkelawy, M., H. A.-E. Bastawissi, and H.E. Seleem, Cutting-Edge Innovations in Wind Power: Enhancing Efficiency, Sustainability, and Grid Integration. Pharos Engineering Science Journal, 2025. 2(1): p. 143-156.

- Liu, S. , et al., Advances in urban wind resource development and wind energy harvesters. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2025. 207: p. 114943.

- Yang, Y. and E.V. Solomin, Wind direction prediction based on nonlinear autoregression and Elman neural networks for the wind turbine yaw system. Renewable Energy, 2025. 241: p. 122284.

- Spiru, P. and P.L. Simona, Wind energy resource assessment and wind turbine selection analysis for sustainable energy production. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 10708.

- Bilendo, F. , et al., Applications and modeling techniques of wind turbine power curve for wind farms—A review. Energies, 2022. 16(1): p. 180.

- Zhang, J. , et al., Power prediction of a wind farm cluster based on spatiotemporal correlations. Applied Energy, 2021. 302: p. 117568.

- Castillo, O.C. , et al., Comparison of power coefficients in wind turbines considering the tip speed ratio and blade pitch angle. Energies, 2023. 16(6): p. 2774.

- Pellegri, A. , The complementary betz theory. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2201.00181, 2022.

- Wang, Y. , et al., A new method for prediction of power coefficient and wake length of a horizontal axis wind turbine based on energy analysis. Energy Conversion and Management, 2022. 252: p. 115121.

- Hernández Montoya, E.E., E. Mendoza, and E.J. Stamhuis, Biomimetic design of turbine blades for ocean current power generation. Biomimetics, 2023. 8(1): p. 118.

- Abdel-Qader, M.S.I. , Simulation of a hybrid power system consisting of wind turbine, PV, storage battery and diesel generator with compensation network: design, optimization and economical evaluation. 2008.

- Lewicki, W., M. Niekurzak, and A. Koniuszy, Evaluation of the Possibility of Using a Home Wind Installation as Part of the Operation of Hybrid Systems—A Selected Case Study of Investment Profitability Analysis. Energies, 2025. 18(8): p. 2016.

- Saleh, Y.A.S., M. Durak, and C. Turhan, Enhancing Urban Sustainability with Novel Vertical-Axis Wind Turbines: A Study on Residential Buildings in Çeşme. Sustainability, 2025. 17(9): p. 3859.

- Badawi, A.S. , et al., Practical electrical energy production to solve the shortage in electricity in palestine and pay back period. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), 2019. 9(6): p. 4610-4616.

| Method Name | Description of Method | Method’s Equations |

| Method of Moments (MM) [87,88]. | Utilizing the MM approach is a highly efficient strategy for obtaining the Weibull parameters. The 1st moment corresponds to the origin, whereas the 2nd moment is relevant to the mean. Moments serve as the basis for computing the parameters k and c [83,89]. |

, (3) (4) , (5) , (6) where; is the total number of non-zero wind speed data points, and Γ(x) is the gamma function, and can be calculated as in (7): (7) |

| Empirical Method (EM) or Standard Deviation Method (STDM) [90,91,92,93]. | The empirical approach presents a direct and practical solution that merely requires knowledge of mean wind speed and standard deviation σ [94]. |

(8) (9) |

| Maximum Likelihood Method (MLM) [95,96,97]. |

Used in the research of finding information about the wind speed. The k and c parameters are obtained by an associated set of equations. |

(10) (11) |

| Modified Maximum Likelihood Method (MMLM) [98,99,100]. | MMLM can only be applied when the wind speed data is presented in the form of a frequency distribution. It involves multiple iterations in order to calculate the Weibull parameters [101]. |

(12) , (13) |

| Second Modified Maximum Likelihood Method (SMMLM)[25,90]. | SMMLM eliminates the need for iterative estimation of the shape parameter and does not require any iteration or data sorting [102]. |

, (14) |

| Graphical Method (GM) or Least Mean Square Method (LSM) [102,103,104]. | In the context of GM, it is necessary to initially classify the wind speed record into specific bins. |

(15) |

| Energy Pattern Factor Method (EPF) [75,105]. |

The EPF is correlated with the average records of wind speed. |

, (16) where is given as (17). , (17) |

| Numerical methods | GOF for Ramallah of wind speed data | ||||||||||

| R: Ranking based on the percentage of errors | |||||||||||

| Comparative analysis | |||||||||||

| RMSE | R | X2 | R | IA | R | MAPE | R | RRMSE | R | ||

| 1 | MM | 5.9333e-05 | 2 | 0.0015 | 2 | 0.9999 | 2 | 0.0011 | 2 | 0.0818 | 2 |

| 2 | STDM, EM | 8.0679e-05 | 4 | 0.0031 | 4 | 0.99982 | 4 | 0.0015 | 4 | 0.1112 | 4 |

| 3 | MLM | 3.2486e-08 | 1 | 4.0035e-10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5.7298e-07 | 1 | 4.4793e-05 | 1 |

| 4 | MMLM | 1.8832e-04 | 5 | 0.0097 | 6 | 0.9993 | 5 | 0.0029 | 6 | 0.2596 | 5 |

| 5 | SMMLM | 0.0171 | 7 | 0.0056 | 5 | 0.9992 | 6 | 0.0027 | 5 | 23.7037 | 7 |

| 6 | GM, LSM | 0.0013 | 6 | 0.2199 | 7 | 0.9782 | 7 | 0.0157 | 7 | 1.8855 | 6 |

| 7 | EPF | 7.2081e-05 | 3 | 0.0024 | 3 | 0.99986 | 3 | 0.00136 | 3 | 0.0993 | 3 |

|

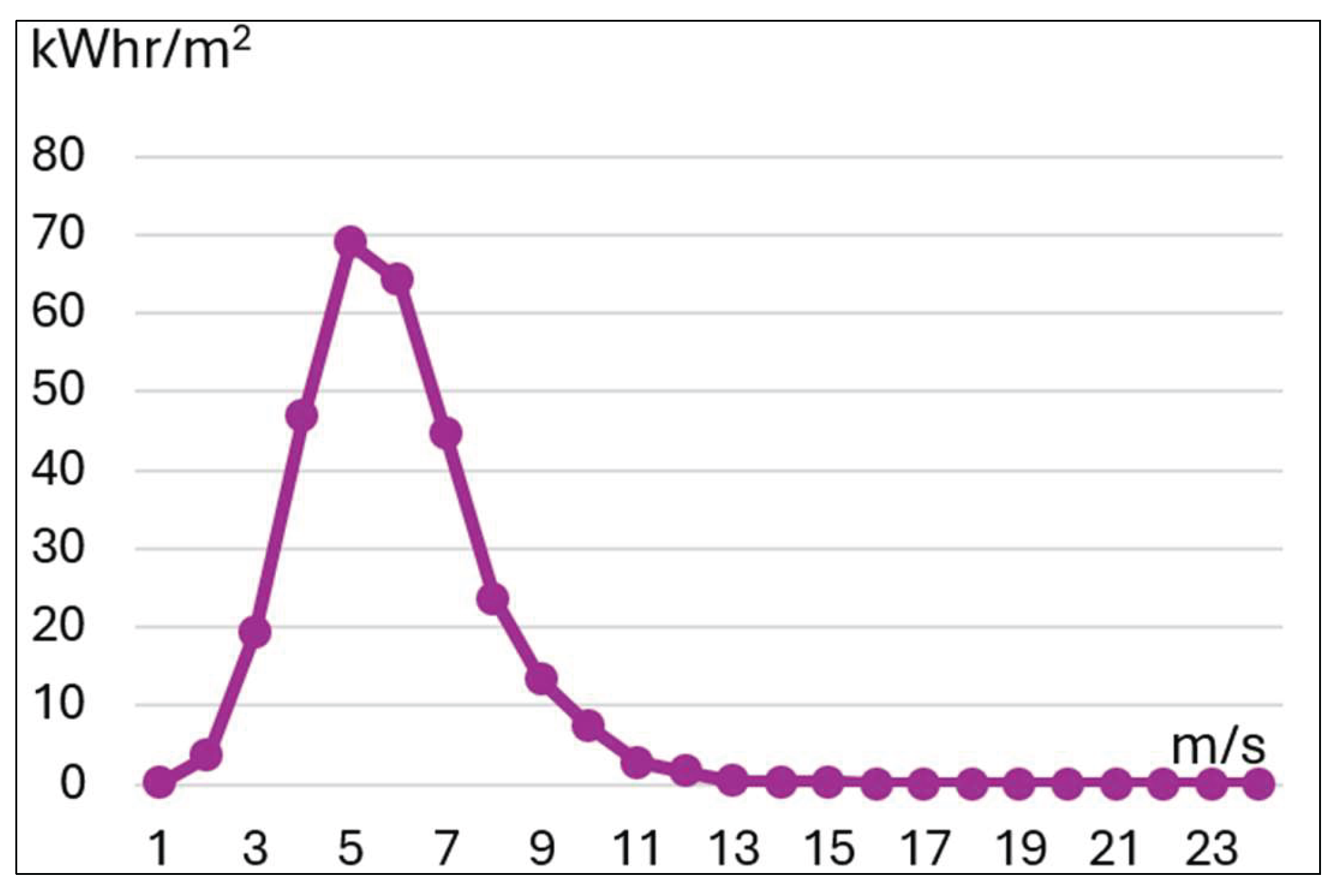

μ m/s |

Times (hr.) |

Incident (%) | Power (W) | Power Density (W/m2) |

Energy kW.hr/m2 |

| 0.5 | 899.8 | 10.27 | 0.075625 | 0.78 | 0.07 |

| 1.5 | 1718.8 | 19.62 | 2.041875 | 40.06 | 3.51 |

| 2.5 | 2030.6 | 23.18 | 9.453125 | 219.12 | 19.2 |

| 3.5 | 1806.3 | 20.62 | 25.93938 | 534.87 | 46.85 |

| 4.5 | 1250.3 | 14.27 | 55.13063 | 786.84 | 68.93 |

| 5.5 | 637.5 | 7.28 | 100.6569 | 732.48 | 64.17 |

| 6.5 | 268.2 | 3.07 | 166.1481 | 508.77 | 44.56 |

| 7.5 | 92.5 | 1.06 | 255.2344 | 269.37 | 23.61 |

| 8.5 | 35.9 | 0.41 | 371.5456 | 152.11 | 13.34 |

| 9.5 | 14 | 0.16 | 518.7119 | 82.68 | 7.26 |

| 10.5 | 3.8 | 0.04 | 700.3631 | 30.55 | 2.66 |

| 11.5 | 1.8 | 0.02 | 920.1294 | 18.52672 | 1.66 |

| 12.5 | 0.3 | 0.00 | 1181.641 | 3.96537 | 0.35 |

| 13.5 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 1488.527 | 2.50 | 0.15 |

| 14.5 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 1844.418 | 3.09 | 0.18 |

| 15.5 | 0 | 0 | 2252.944 | 0 | 0 |

| 16.5 | 0 | 0 | 2717.736 | 0 | 0 |

| 17.5 | 0 | 0 | 3242.422 | 0 | 0 |

| 18.5 | 0 | 0 | 3830.633 | 0 | 0 |

| 19.5 | 0 | 0 | 4485.999 | 0 | 0 |

| 20.5 | 0 | 0 | 5212.151 | 0 | 0 |

| 21.5 | 0 | 0 | 6012.717 | 0 | 0 |

| 22.5 | 0 | 0 | 6891.328 | 0 | 0 |

| 23.5 | 0 | 0 | 7851.614 | 0 | 0 |

| Sum 8760 | 100% | 50137.56 | 3385.75 | 296.5 | |

| Type | Wind Power Generator |

| Cut-in wind speed | 3m/s |

| Rotor diameter | 6 m |

| Rated output power | 5 kW at 10m/s |

| Max output power | 7.5 kW |

| Generator type | Permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG), 3 phase AC |

| wind turbine type | Horizontal axis |

| Output voltage | 48 volts |

| Type | Wind Power Generator |

| Cut-in wind speed | 3m/s |

| Rotor diameter | 6 m |

| Rated output power | 5 kW at 10m/s |

| Max output power | 7.5 kW |

| Generator type | Permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG), 3 phase AC |

| wind turbine type | Horizontal axis |

| Output voltage | 48 volts |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).