1. Introduction

The concept of

free energy unifies thermodynamic, informational, and biological principles of organization. Within the

Free Energy Principle (FEP), adaptive systems minimize an internal free-energy functional to resist disorder and maintain self-organization [

1,

2]. Yet, the geometric structure underlying this process—how symmetry and invariance constrain information flow—remains underexplored. Here we formulate free-energy minimization as an

entropic gradient flow on Lie-group orbits, allowing a unified view of symmetry, stability, and self-organization. Recent expositions provide simplified overviews and technical clarifications that we leverage here [

3,

4].

Contributions

We provide: (i) an orbit-reduced formulation of variational free energy; (ii) first- and second-variation formulas on orbits; (iii) local well-posedness and Lyapunov monotonicity; (iv) convergence on compact groups and under the Kurdyka–Łojasiewicz (KŁ) property; (v) stability criteria via the orbit-restricted Hessian; (vi) a pitchfork scenario for ; and (vii) worked Gaussian examples with explicit derivatives.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Standing Assumptions and Notation

(Q1) is a statistical manifold with Fisher metric . (Q2) G is a finite-dimensional Lie group acting smoothly on Q by , with stabilizer H at ; the orbit is an embedded submanifold. (Q3) The free-energy functional is and bounded below on . (Q4) G carries a right-invariant Riemannian metric . Throughout, , denotes the gradient with respect to , and the infinitesimal action for .

2.2. Variational Free Energy

Given a generative model

and a variational posterior

,

so minimizing

recovers the evidence lower bound.

2.3. Statistical Manifolds

Let

with log-density

. The Fisher information metric is

with natural gradient

for smooth

.

2.4. Group Actions and Orbits

Optimization restricted to the orbit converts to with .

3. Orbit Gradients

We make precise the identification between the natural gradient on Q and the Riemannian gradient on G.

Theorem 1 (Equivalence of natural and group gradients on the orbit)

. Under (Q1)–(Q4), let parametrize G near e, and set . Assume the Jacobian has full column rank along . Equip G with the induced metric from the Fisher metric . Then for any smooth , the natural gradient of restricted to corresponds exactly to the Riemannian gradient on ; i.e.

Proof. Let and consider the variation . By the chain rule, where . Denote by the Fisher metric on and define an induced inner product on parameter increments by . This is positive definite by full column rank of J. The Riesz representation of with respect to yields the unique such that for all . But . Thus corresponds to , which is precisely the coordinate representation of the Riemannian gradient on . Projecting to accounts for any null directions associated with the stabilizer H. □

Remark 1 (Coordinate formula). In local coordinates, , with . This realizes a Gauss–Newton structure typical of natural-gradient methods.

4. Gradient Flows and Convergence

Define the gradient flow on

G by

Theorem 2 (Local well-posedness)

. If and is locally Lipschitz with respect to γ, then (

3)

admits a unique maximal solution from any initial point.

Proof. Right-translate by and write with . The map is locally Lipschitz on charts. This gives a locally Lipschitz ODE on in coordinates; Picard–Lindelöf on manifolds (via charts and partition of unity) yields a unique solution. □

Theorem 3 (Lyapunov monotonicity)

. Along any solution of (

3)

,

If F is bounded below, the limit exists.

Proof. The identity holds by definition of the gradient. Substitute . □

Theorem 4 (Asymptotics on compact groups)

. If G is compact and has only nondegenerate critical points, then every trajectory of (

3)

has ω-limit set contained in the (finite) set of critical points. In particular, every bounded trajectory approaches the set of critical points; moreover, if F additionally satisfies the KŁ property at its critical points (e.g. F is real-analytic), then the trajectory converges to a single critical point.

Proof. Compactness implies that sublevel sets are compact. By Theorem 3, decreases and is bounded below, hence remains in a compact set and admits accumulation points, all critical by . Nondegeneracy and the stable manifold theorem imply convergence to a single critical point. □

Theorem 5 (Convergence under KŁ property). Assume is bounded below and satisfies the Kurdyka–Łojasiewicz property at every critical point (e.g., F is real-analytic on an analytic G). Then every bounded trajectory of has finite length and converges to a single critical point as .

Proof. Let be bounded with . The KŁ inequality provides near the limit set for some desingularizing function . Integrating over time and applying the inequality shows , hence has finite length and is Cauchy; completeness of G yields convergence to a critical point. □

5. Second Variation and Stability

We derive the orbit-restricted Hessian and a stability test.

Lemma 1 (First and second variations along one-parameter subgroups)

. For and ,

If , then along at a critical with ,

Proof. For (

5), differentiate

and use

. For (

6), differentiate (

5) again in the direction

Y and invoke the symmetry of

plus the Lie-bracket identity

. □

Proposition 1 (Stability on the orbit)

. Let be the Lie algebra of the stabilizer at . If the quadratic form is positive definite on , then is a strict local minimum and asymptotically stable for (

3)

. Negative/indefinite signatures yield maxima/saddles.

Proof. Positive definiteness implies that

in a neighborhood (in exponential coordinates), hence

F is a Lyapunov function with a strict minimum. The linearization of (

3) at

has spectrum in

on

, yielding asymptotic stability by the Hartman–Grobman theorem on manifolds. □

6. Symmetry and Bifurcation

Definition 1 (Group invariance). The functional is G-invariant if for all , . Then F is constant on G, and every g is critical. Partial invariance or data terms induce nontrivial landscapes.

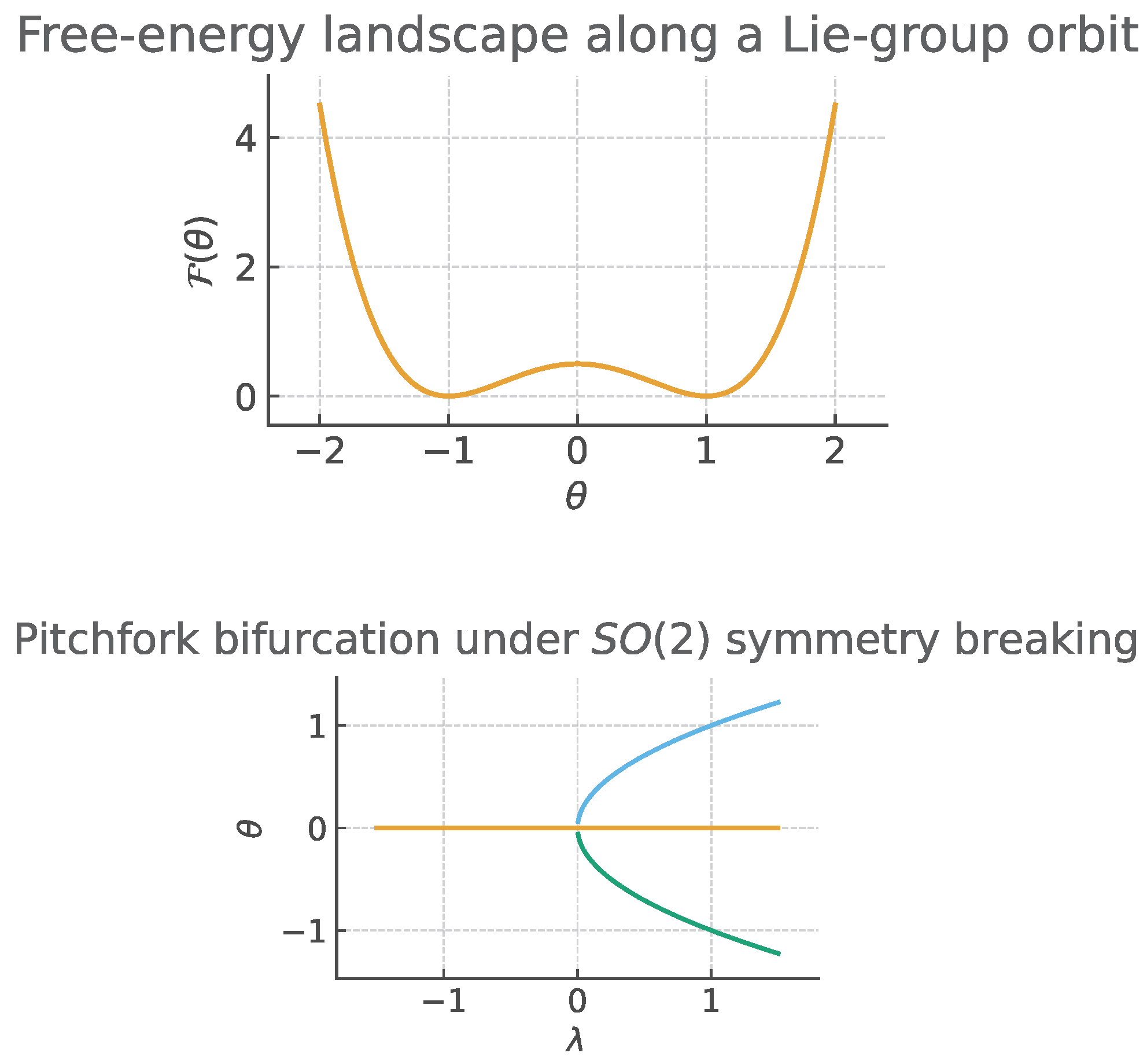

Theorem 6 (Pitchfork for ). Let act on planar Gaussians by covariance conjugation, and consider a one-parameter family . If at the smallest nonzero orbit-restricted eigenvalue of the Hessian crosses zero while symmetry suppresses the cubic term, then two nontrivial minima bifurcate from the symmetric one as λ passes through .

Sketch. Normal-form reduction on the one-dimensional orbit coordinate gives with , , and the odd cubic suppressed by symmetry. The change of sign of a yields a supercritical pitchfork. □

7. Examples

7.1. Translations of Means (Abelian Case)

Let

Q be

d-dimensional Gaussians with mean

and fixed covariance

. The additive group

acts by

. Consider

Proposition 2. The orbit cost is strictly convex and admits a unique minimizer with .

Proof. Convexity follows from convexity of the squared norm and the joint convexity of under translations. Strictness holds unless p is itself translation invariant. Differentiating under the integral sign gives the first-order condition. □

7.2. Planar Rotations of Covariances

For zero-mean Gaussians,

Let

with

the

rotation. Then

Hence

Critical points satisfy

, i.e. simultaneous diagonalizability of

and

; anisotropy yields two symmetric minima modulo

.

7.3. Rigid Motions and Outlook to

The special Euclidean group couples rotations and translations; the induced metric on G blends mean and covariance directions. The same formalism extends to for 3D pose models.

Figure 1.

(Top) Free-energy landscape along a Lie-group orbit. (Bottom) Pitchfork bifurcation under symmetry breaking.

Figure 1.

(Top) Free-energy landscape along a Lie-group orbit. (Bottom) Pitchfork bifurcation under symmetry breaking.

8. Entropy Reduction Under Lie-Group Symmetry

This section interprets free-energy descent as a physical process of entropy reduction constrained by Lie-group symmetry.

Thermodynamic entropy and informational stability.

On Lie-group orbits, entropy reduction corresponds to the dissipation of uncertainty along symmetry-constrained manifolds. The Fisher metric quantifies the local curvature of information, and its geodesic flow describes the most efficient direction of entropy decrease under free-energy descent. Thus, stability of a group orbit can be interpreted as a steady state with (possibly nonzero) steady entropic production balanced by symmetry-constrained fluxes.

Information-theoretic analogy.

Write the free energy as

Along any smooth evolution of

q, we have

Hence entropy reduction and evidence gain are coupled but not identical in general. In our orbit-restricted dynamics, Lyapunov monotonicity yields

, which we interpret as a nonnegative “entropic production rate” on the group manifold. Lie-group symmetries then restrict admissible directions of this production, shaping the accessible information flows.

Physical interpretation.

In this light, the orbit flow describes a dissipative process that drives the system toward minimal free energy under constraints imposed by G. Equilibria on orbits correspond to stationary nonequilibrium states, and bifurcations of F signal transitions between entropic basins—an informational analogue of phase transitions.

9. Related Work

Classical information geometry [

7,

8] endows models with the Fisher metric and dual connections; natural gradient methods exploit this geometry. In contrast, we constrain inference to Lie-group orbits and move optimization to the group manifold. This orbit-centric view enables stability and bifurcation analyses less transparent in parameter space. We also draw on recent discussions of the FEP and Bayesian mechanics [

3,

4,

5,

6].

10. Discussion

We presented a geometric reduction of FEP to optimization on Lie groups, with explicit stability and bifurcation analyses. Future work includes thermodynamic formulations of entropy reduction on noncommutative groups (, matrix groups), and numerical exploration of entropic symmetry breaking. This framework bridges information geometry, nonequilibrium thermodynamics, and adaptive inference in a single mathematical language.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks colleagues for discussions on information geometry, Lie theory, and variational principles.

References

- K. Friston, A theory of cortical responses, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 360, 815–836 (2005). [CrossRef]

- K. Friston, The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?, Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11, 127–138 (2010). [CrossRef]

- K. Friston, The free energy principle made simpler but not too simple, Physics Reports 1024, 1–43 (2023). [CrossRef]

- K. J. Friston, L. Da Costa, T. Parr, Some Interesting Observations on the Free Energy Principle, Entropy 23(8), 1076 (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. Da Costa, K. Friston, C. Heins, G. A. Pavliotis, Bayesian mechanics for stationary processes, Proceedings of the Royal Society A 477(2256), 20210518 (2021). [CrossRef]

- P. Ao, Emerging of Stochastic Dynamical Equalities and Steady State Thermodynamics from Darwinian Dynamics, Communications in Theoretical Physics 49(5), 1073–1090 (2008). [CrossRef]

- S.-I. Amari and H. Nagaoka, Methods of Information Geometry, AMS/OUP (2000).

- S.-I. Amari, Information Geometry and Its Applications, Springer (2016).

- F. Otto, The geometry of dissipative evolution equations: the porous medium equation, Communications in Partial Differential Equations 26(1–2), 101–174 (2001). [CrossRef]

- C. Villani, Optimal Transport: Old and New, Springer, Berlin (2009).

- J. M. Lee, Introduction to Smooth Manifolds, 2nd ed., Springer (2012).

- F. W. Warner, Foundations of Differentiable Manifolds and Lie Groups, Springer (1983).

- S. Helgason, Differential Geometry, Lie Groups, and Symmetric Spaces, Academic Press (1978).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).