1. Introduction

Clinical governance is a system through which health service organisations are responsible and accountable for continuously working to improve the quality of their services, safeguarding high standards of care, and ensuring the best clinical outcome for patients [

11]. The concept of clinical governance was first introduced in the United Kingdom in the late 1990s to tackle wide differences in quality of care throughout Britain [

7]. Its purpose was to provide framework supporting local National Health Service (NHS) organisations in implementing their statutory duties of quality. Clinical governance ensures the quality and safety of our public healthcare systems [

13], by creating an environment conducive to excellence in clinical care [

11]. It holds clinicians and healthcare organisations to a set of standards important for health and national health strategies [

2].

Clinical governance provides an opportunity for service providers to better understand and develop the fundamental components needed to deliver positive patient experiences and outcomes for their health issues [

14] Clinical governance also promotes a learning environment, one where healthcare professionals are encouraged to constantly build on their skills and improve their decision making and healthcare outcomes [

2].

South Africa followed suit by adopting and introducing clinical governance into the country’s health system [

10]. In 2018, the Minister of Health published a regulation entitled ‘Norms and standards applicable to different categories of health establishments to promote and protect the health and safety of users and healthcare personnel [

5]. This regulation contains sub-regulations across the following domains: user rights; clinical governance and clinical care; clinical support services; facilities and infrastructure; governance and human resources; and general provisions [

15] This publication of regulations demanded a major shift in values, culture, and leadership to place greater focus on the quality of clinical care, and to make it easier to bring about improvement and change in clinical practice [

10].

Nevertheless, South Africa continues to grapple with disparities in healthcare access and quality between rural and urban area significantly affect the implementation of clinical governance. Disparities create challenges that hinder the effective establishment and functioning of clinical governance, through limited resources, variation in standard of care and challenges in data collection and monitoring [

6]. Health professionals are crucial to the success of clinical governance, their leadership, and involvement in quality improvement, collaboration, education and monitoring efforts can help overcome these challenges and foster a culture of safety and quality in healthcare delivery [

3] In South Africa, there is a concentration of quaternary, tertiary, and regional hospitals in urban areas, leaving rural populations to rely on smaller district hospitals for health services [

13] Also, minority of health professionals are servicing the rural (district) hospitals. [

1] Reports by department of health districts indicate that urban areas have a higher density of doctors and nurses [

5]. For instance, while the national average is about 0.8 doctors per 1000 people, rural areas have as low as 0.1 doctors per 1000 people resulting in limited access to medical care for rural populations [

5].

District hospitals play a crucial role in the healthcare system, serving as primary points of access for a significant portion of the population with unique healthcare needs [

14]. However, the unique contextual factors, resource constraints, and diverse healthcare needs prevalent in district settings present distinct challenges (or barriers) and enable the successful implementation of clinical governance, for example, government policies, societal norms, and cultural beliefs can either facilitate or hinder the implementation process [19].

The health system in the Eastern Cape is characterised by underdeveloped hospital services, shortage of health professionals and beds, inadequate access to quality specialist hospital services and generally poor health outcomes [

14]. A report by the Department of Health (DoH) linked some of these challenges to poor leadership and governance in healthcare facilities [

5]. A well-resourced healthcare institution is better equipped to promote high standards of care, ensure patient safety and foster a culture of continuous improvement, leading to enhanced healthcare quality and outcome, thus availability of resources, both financial and human, within healthcare institutions significantly affects clinical governance implementation [

2].

According to a report of the DoH, Grey hospital is one of the hospitals which are performing poorly in the Buffalo City Metro Municipality, Eastern Cape Province [

5] The report noted with concern, the weaknesses in the areas of clinical governance and management. These weaknesses in areas of hospital governance, including clinical governance can have a negative consequence on the quality of healthcare services and healthcare outcomes of the population [

17]. Despite these findings, the extent to which clinical governance protocols and/or quality improvement initiatives are implemented at Grey hospital remains unknown. No research study has been conducted to explore or establish the implementation of clinical governance at Grey hospital. Thus, this study seeks to explore the implementation of clinical governance protocols and/or quality improvement activities at Grey hospital. This research will gather valuable insights about the hospital in relation to clinical governance implementation and potentially make evidence-based recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Significance of the Study

This study provides insights on the availability and implementation of clinical governance protocols or quality improvement activities at Grey hospital. This study also provided information about the key players in the implementation of clinical governance at Grey Hospital as observed by doctors and nurses. Findings from this study provide baseline information, activate in-depth analysis on the implementation or lack thereof clinical governance at Grey hospital. Furthermore, the study makes recommendations on the important role of members of staff in ensuring that the clinical governance framework is implemented purposefully in a hospital.

2.2. Research Objectives

❖ To identify available clinical governance protocols and related quality improvement activities at Grey hospital

❖ To identify the principal role players involved in the implementation of clinical governance activities at Grey hospital

❖ To determine the perceived level of importance of selected managers at Grey hospital

2.3. Methods and Analysis

This study used a quantitative approach with a cross-sectional design to answer the research questions. The use of a quantitative research approach ensured that data is collected in a consistent manner, while the cross-sectional design allowed the researcher to collect data at a single point in time [

8].

2.4. Study Setting

The study was conducted at Grey hospital, a 67-bed district-level hsopital located in King William’s Town within the Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa [

5]. Buffalo City is a metropolitan municipality situated along the east coast of the Eastern Cape, a province that spans approximately 168,966 square kilometres—accounting for 13.8% of South Africa’s total land area [

5].

Established in the 19th century, Grey hospital has a longstanding history of serving diverse communities and addressing both acute and chronic health needs. The hospital comprises several departments, including Emergency, Paediatrics, Maternity, Outpatients, Surgical, Medical, Operating Theatre, Pharmacy, Counselling, Laundry, Kitchen, and Mortuary services. As a cornerstone of healthcare delivery in the region, Grey Hospital plays a critical role in providing essential medical services and contributing to community well-being [

5]. Despite its significance, the hospital faces persistent challenges such as staff shortages, limited resources, high patient volumes, and governance constraints. These contextual factors are important for understanding the implementation and sustainability of clinical governance practices within the facility [

5]. Despite its significance, the hospital faces persistent challenges such as staff shortages, limited resources, high patient volumes, and governance constraints. These contextual factors are important for understanding the implementation and sustainability of clinical governance practices within the facility.

2.5. Population and Sampling

All doctors and nurses employed at Grey hospital with at least six months working at the hospital were recruited for participation in this study. Consequently, the total sample size for the study was 115 participants, comprising 8 doctors and 107 nurses.

2.6. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

❖ Only doctors and nurses who have been working at Grey hospital for at least six months were considered for participation in this study. This period was considered to be long enough for participants to have adequate knowledge about the hospital to enable them to respond to the survey questions.

❖ Only participants who are at least 18 years old of age were considered for participation in this study.

❖ Participants who chose not to sign the informed consent form were excluded from participation in this study. This criterion ensured that all included individuals voluntarily agreed to participate and understood the nature of the research.

2.7. Data Collection and Management

The researcher utilised a validated, structured quantitative questionnaire (Appendix A) derived from Chitha's "Clinical Governance Implementation Status Survey" (CGIS) [

17]. Given that all prospective participants are professional healthcare workers, the questionnaire was administered in English without translation. Participants completed the printed questionnaires independently, although the researcher was available to provide clarification as needed. This approach helped mitigate social desirability bias by ensuring anonymity, minimizing the data collector's influence, and fostering a comfortable environment for respondents. As a result, this method facilitated the collection of accurate and genuine data, thereby enhancing the validity of the research findings [

18]. The researcher selectively employed sections of the CGIS deemed pertinent to this study’s objectives.

The adapted CGIS questionnaire is structured as follows:

❖ Section A: Demographic profile. This section captured information about the Nationality, Sex, Age, Years of service, Years of service at Grey hospital and Organisational status of the participants.

❖ Section B: Confirmation of the presence of the following quality improvement activities and protocols in my hospital. This section captured participant responses about availability of selected clinical governance protocols and/or occurrence of quality improvement activities using the following Likert scale responses: 1= Yes, 2= No, 3= Not sure, 4= Don’t know.

❖ Section C: Hospital staff members’ involvement in the implementation of quality improvement activities and their perceived level of importance. This section captured the responses from participants about the extent to which selected hospital staff members are involved in the implementation of quality improvement activities. This section also captured responses about the perceived level of importance of the selected hospital staff members in the implementation of quality improvement activities using the following Likert scale options: 1= Very Important, 2= Somewhat Important, 3= Not Important.

All hard copies of the data are stored in a secured and lockable cabinet which is only accessed by the researchers. The electronic data on the other hand is stored in a cloud-based storage system which is password protected only known by the researchers.

2.8. Data Analysis

In this study, survey data was captured into Microsoft Excel then exported into STATA version 18 for analysis. Data for all the three study objectives was analysed using descriptive statistics. Categorical data are compared using frequencies, percentages, and graphical representations. Numerical data, including participant and years of service, were explored for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported as data is non-normally distributed, while the mean and standard deviation (SD) are reported as data is normally distributed. This approach ensured that appropriate statistical measures were applied, enhancing the reliability of the findings.

2.9. Ethical Consideration

Ethics approval for the study was secured from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University (Ref: 218/2024). Authorization to access the health facilities was granted by the Provincial Health Research Committee of the Eastern Cape (Ref: EC_202412_026). Furthermore, permission to conduct research at Grey hospital was obtained from the hospital's Chief Executive Officer prior to initiating data collection. The study adhered to the four ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Participants were required to sign an informed consent form, ensuring that they were fully aware of their rights. This included the right to withdraw from the study at any time or to decline to answer specific questions without facing any repercussions. To maintain participant confidentiality, all identifiable information, such as personal details, was removed from the data, ensuring complete anonymity throughout the research process.

3. Results

3.1. Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to present and discuss the study results, aligning with the objectives set out in Chapter 1. The methods and techniques described in the previous chapter were used to analyse the survey data. The results are summarised in

Table 1 and

Table 2 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

3.2. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

The study included 107 participants, of whom the majority were females (71%), and 37-47 years (48.6%) were the majority, young participant 26 years and 60 years being the oldest participant with a mean age of 43,9 years. Most participants were professional nurses (59.8%), and doctors were few with 1.8%. The years of service were relatively evenly distributed across different categories with a median of 12 years.

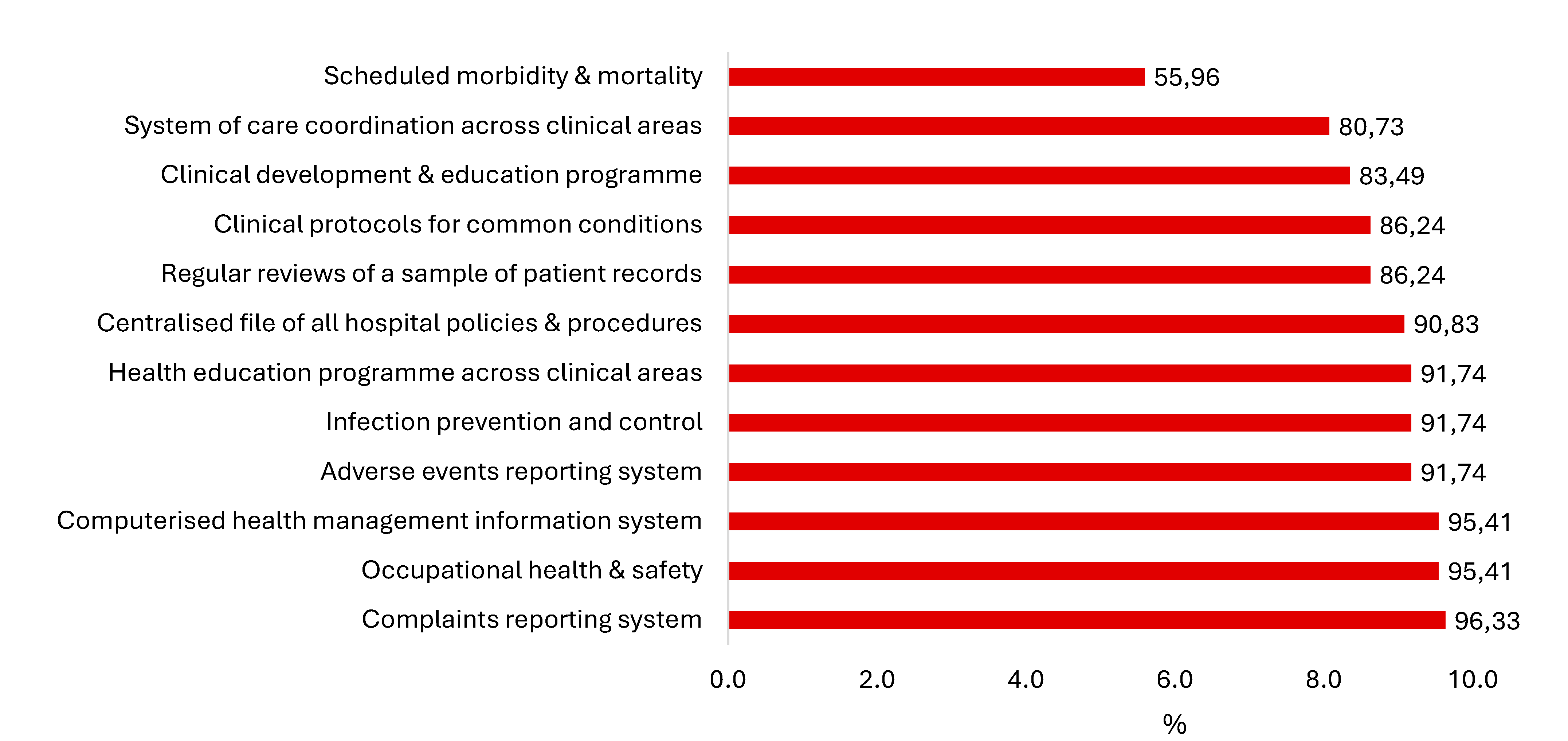

Figure 1: shows the distribution of participants responses concerning the existence of clinical governance protocols and associated quality improvement initiatives at Grey hospital, data derived from healthcare professionals at Grey hospital depicts the proportion of respondents who either affirmed or denied the presence of clinical governance protocols. The distribution patterns within the figure reveal the extent to which clinical governance and quality improvement are perceived to be embedded within the hospital’s operational structure. Over 80% of protocols and activities are affirmed to be present by participants with scheduled morbidity and mortality meetings at 56%.

Table 2 shows statistically significant differences regarding the information and nursing operations managers’ (p-value = 0.036 and p = 0.018, respectively) in the implementation of clinical governance as reported by the study participants. No statistically significant differences regarding the observed involvement of the other hospital managers in the implementation of clinical governance activities.

Table 2 further shows that participants perceive a strong involvement of various management in the implementation of clinical governance activities. A significant majority of respondents indicate that each role player listed is involved. Specifically, the nursing operations manager (97.3%), other health professionals (92.7%), and clinical head of department (91.7%) are perceived as most fully involved. While most roles are seen as fully involved by over 80% of respondents.

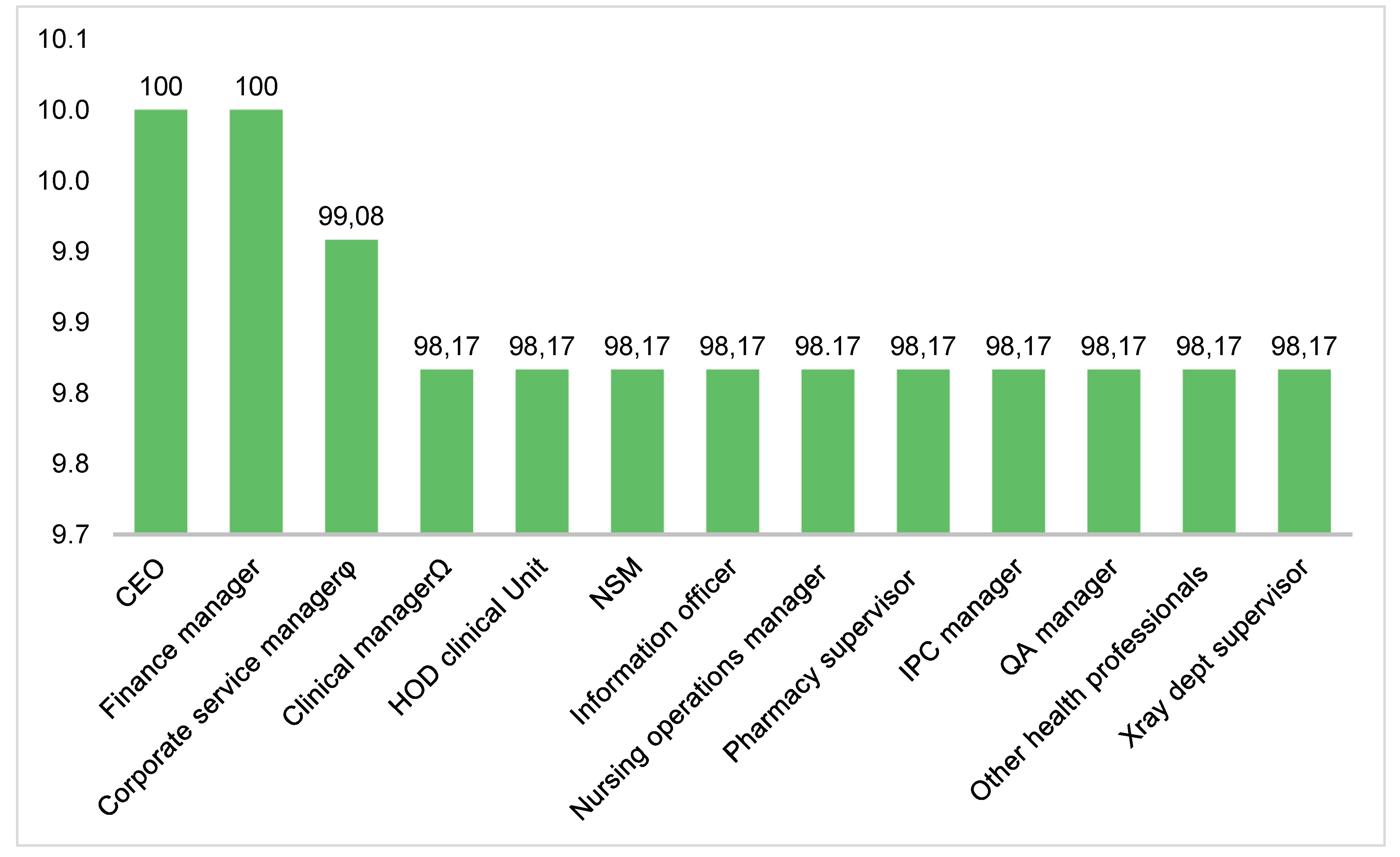

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of participants' ratings of the importance of selected managers in the implementation of clinical governance activities at Grey Hospital, using a 5-point Likert scale showing that the CEO and Finance manager are most important at Grey hospital about clinical governance and every unit manager is much important as they are all above 90%.

4. Discussion

This study assessed implementation of clinical governance protocols or quality improvement activities, hospital management’s involvement and their level of importance in implementing clinical governance activities at Grey hospitals from the perspective of medical doctors and nurses. The findings indicated that a significant number of clinical governance protocols and quality improvement activities were either available or actively taking place within the hospital. However, it was noted that fewer than 60% of participants reported the presence of scheduled morbidity and mortality meetings, indicating a potential gap in critical quality oversight mechanisms. The involvement of hospital management in implementing clinical governance activities was reported to be robust, with all members perceived as important. Notably, the CEO and Finance Manager stood out as the most crucial figures, underscoring their roles in driving the clinical governance agenda and ensuring the financial viability of quality improvement initiatives.

The scheduled morbidity and mortality meetings reflect an essential component of clinical governance as they improve patient outcomes through reflective practice and learning from adverse events [

11]. The findings of this study are supported with findings by [

4] in a study they conducted in the University of Wisconsin in the United State of America. Suggesting that having morbidity and mortality meetings is crucial as it helps to pre-empt problems and review the quality of care that is being provided and active engagement in governance protocols is crucial for fostering a culture of safety and accountability in healthcare settings.

Findings regarding involvement among key role players suggest that the implementation of clinical governance may not be uniformly perceived or executed across all departments, possibly due to different priorities [

3]. The absence of statistically significant differences in the reported involvement of other hospital managers indicates a more consistent, although potentially lower level of engagement across these roles, suggesting a need for targeted interventions to enhance their participation in clinical governance initiatives [

6]. A similar study conducted by [

8] supports these findings in their study conducted at six NHS hospitals in United Kingdom, England.

The study indicate that participants regard the CEO and finance manager as crucial to the implementation of clinical governance at Grey hospital. The high importance ratings above 90% for unit managers highlight the necessity for leadership at all levels to foster a culture of quality and safety. This reflects the study by [

10] conducted in the United Kingdom which emphasizes the CEO's responsibility in creating a supportive environment for clinical governance. This involves allocating resources, setting strategic direction, and ensuring accountability for quality and safety [

16]. research suggests that a CEO's visible commitment is directly correlated with the successful adoption of clinical governance frameworks. Furthermore, the finance manager's role, often overlooked, is crucial in providing the necessary financial resources and incentives for clinical governance initiatives.

5. Conclusions

These findings indicate the presence of a clinical governance framework at Grey hospital, highlighting the need for ongoing engagement and collaboration among all stakeholders, including both clinical and non-clinical leaders. Such collaboration is crucial for optimising governance practices and ensuring that the framework remains effective and responsive to the needs of the organisation.

To enhance the framework, it is imperative to facilitate consistent information sharing among all staff members. This will foster a culture of transparency and inclusiveness, encouraging active participation from healthcare professionals across various levels. Strategies could include regular meetings, workshops, and accessible digital platforms where staff can share insights, report concerns, and propose improvements related to governance practices. By prioritising continuous communication and the involvement of all personnel at Grey hospital, the institution can strengthen its clinical governance framework, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes and enhanced operational efficiency.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Eastern Cape DoH approval number: EC_202412_026, and Walter Sisulu University Health Research Ethics Committee of Walter Sisulu University protocol code: 218/2024 dated 17 December 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

The study abided by the four ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Participants signed informed consent form. Participants were notified about their rights including the fact that they can withdraw at any stage of the study or opt out of questions they do not wish to respond to without facing any consequences. Data was de-identified by removing any identifying (such as, personal details) information to ensure anonymity of the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Eastern Cape DoH (Research Committee) and BCMM District health manager for allowing me to collect data in one of their hospitals. Also, I extend my sincere gratitude to the management of Grey hospital and every individual who participated in the process of data collection.:

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NHS |

National Health Services |

| DoH |

Department of health |

| CGIS |

Clinical Governance Implementation Status Survey |

| CEO |

Chief Executive Officer |

| BCMM |

Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality |

References

- Grol R, Wensing M. Improving Patient Care: The Implementation of Change in Health Care. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

- Firth, K. Ward leadership: Balancing the clinical and managerial roles. Professional Nurse. 2021;17(8):486-489.

- Jose Bien RH, Peggy YK. Epidemiology morbidity and mortality. StatPearls. 2022.

- Balding, C. From quality assurance to clinical governance. Australian Health Review. 2019;32(3):383-391.

- Joubert G, Ehrlich R. Epidemiology: A Research Manual for South Africa. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

- Gillam S, Siriwardena AN. Frameworks for improvement: Clinical audit, understanding processes and how to improve them. 2013;323(4382).

- Department of Health. National Health Act (61/2003): Policy on National Health Insurance. Government Gazette 34523. Pretoria; 2019.

- Dixon-Woods M, Baker R, Charles K. Overcoming challenges to improving quality. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2011;20(1):1-5.

- Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Ellis LA, Long J. Complexity in the implementation of clinical governance: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17(1):1-10.

- Barron P, Padarath A. Twenty years of the South African Health Review. South African Health Review. 2017;2017(1):1-0.

- Joubert G, Ehrlich R. Epidemiology: A Research Manual for South Africa. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2012.

- Ferlie E, Fitzgerald L, Wood M, Hawkins C. The nonspread of innovation: The mediating role of professionals. Academy of Management Journal. 2005;48(1):117-134.

- Flynn MA, Brennan NM. Mapping clinical governance to practitioner roles and responsibilities. Journal of Health Organization and Management. 2020;35(9). Accessed []. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Walsh MK. The future of hospitals. Aust Health Rev. 2002;25(5):32-44. Accessed [11 July 2025]. https://www.publish.csiro.au/ah/ah020032a.

- Pillay, R. The skills gap in hospital management in the South African public health sector. Public Health Management Practice. 2018;14(5): E8-E14.

- Thomas, EJ. Improving teamwork in healthcare: Current approaches and the path forward. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2019;20:647-650.

- Chitha, W. The Implementation of Clinical Governance Protocols in the District Hospitals of OR Tambo Health District, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. 2015.

- Pearson B. The clinical governance of multidisciplinary care. International Journal of Health Governance. 2017;22(4). Accessed [17 September 2025]. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHG-03-2017-0007. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).