Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is a highly complex multifactorial disease consisting of several interrelated underlying disorders (ß-cell dysfunction, insulin resistance, hormonal hyperactivity of the visceral adipose tissue, and chronic systemic inflammation). The diagnosis has been made for centuries exclusively on the basis of urine and blood glucose elevation, which ultimately only represents a symptom of the disease and only captures the clinical picture very superficially [

1,

2]. Furthermore, the current guideline-based therapy with almost exclusive focus on the normalization of blood glucose and its surrogate parameter HbA1c [

2] has led to the impression that type 2 diabetes mellitus is a chronic progressive disease. The majority of patients die from macrovascular or microvascular events, which appears to be practically unavoidable even if the glycemic treatment goals are achieved [

2,

3,

4,

5].

On the basis of extensive study experience, a method for phenotyping and consecutive personalized diabetes therapy has been developed in our institute, which we would like to present here and put up for international discussion after initial positive feedback during a local attempt [

6,

7]). Important and first of all: this discussion paper has no missionary background. We would like to present and describe an individualized approach to diabetes therapy, which is based on more than 30 years of clinical and study experience (> 400 clinical trials). We have been successfully employing this concept in routine practice for more than 15 years, and we would now like to share it with a wider audience to invite interested colleagues to try it out and/or to comment on it.

This Part 1 describes the background and the procedure for phenotyping with functional biomarkers [

6]. A consecutive Part 2 presents the translation of phenotyping results into an individualized diabetes therapy and will show real-world patient examples treated according to this concept in our practice [

7]. The basis for our personalized treatment concept is our understanding of the disease pathophysiology, as described in the next section.

Physiological Background

The biological processes of energy balance of the human organism, which form an important basis for the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes, represented a survival advantage many thousands of years ago. It can be assumed that in the Stone Age, when our ancestors still lived in caves and hunted prehistoric animals, people did not always have regular and sufficient access to food. This gave individuals a survival advantage - and they prevailed genetically - who were able to store as much energy as possible as lipid tissue when there was an abundance of food so that they could draw on it in times of starvation. Physiologically, the formation of adipose tissue in the body is the exclusive domain of insulin action [

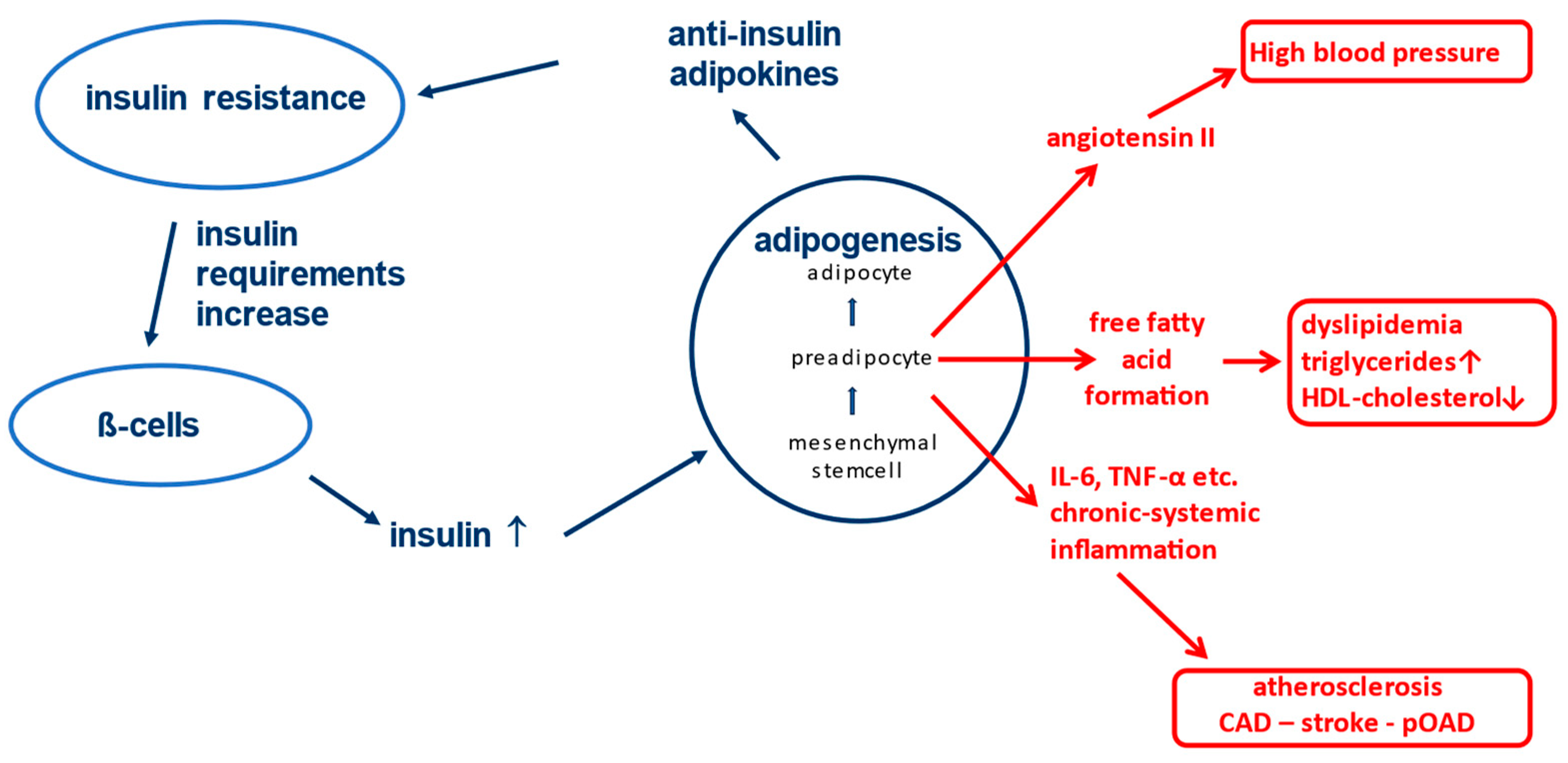

8]. Insulin is known to stimulate the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into preadipocytes (see

Figure 1) [

9,

10,

11].

These preadipocytes in turn are the source of numerous so-called "adipokines", which, despite their highly diverse effects in the body, have one biochemical property in common: they all act against insulin at different receptors and/or cellular levels [

9,

10,

12]. This results in a metabolic insulin resistance and increased insulin requirement for glycemic control. The production capacity of the pancreatic ß-cells is very high and consequently more insulin is produced in response to the increased need, which supports further differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into preadipocytes. Ultimately, these physiological relationships allow the body to tolerate more insulin and use it to generate lipid tissue for energy storage without experiencing negative effects on blood glucose levels. After all, an unconscious person in hypoglycemia cannot eat. In fact, at least in the western world, we are currently living in times of permanent food abundance. As a consequence of the evolutionary conditions, the world is experiencing a wave of obesity for several decades that has never been seen before in the history of mankind [

13].

Adipokines, among other properties, may have negative effects on blood pressure. A prominent representative is angiotensin II, which is formed and released in an uncontrolled fashion by the preadipocytes and drives up blood pressure [

14]. Also, some adipokines induce the formation of free fatty acids and triglycerides. Hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL levels therefore often occur in this situation [

15]. The already increased cardiovascular risk due to high blood pressure and dyslipidemia (see

Figure 1) make the associated fatal diseases (heart attack, stroke, etc.) to be among the main causes of death in the western world, even independently of diabetes [

16]. Reduction of vaso-protective insulin effects (e.g. reduction of anti-oxidative Nitric Oxide secretion) [

17]) is an additional contributing factor to the negative outcome.

Another factor that increases macrovascular risk is the development of chronic activation of the immune system (chronic systemic inflammation) on the basis of stem cell differentiation in adipose tissue [

18,

19]. Whenever differentiation processes take place in the body, there is also a very small amount of incomplete differentiation of stem cells with an occasional risk of formation of cancer cells. To prevent these from causing damage, the immune system is alerted and activated macrophages migrate into the fatty tissue, which can recognize and destroy mutated cells [

20,

21]. However, as the immune system cannot be activated only locally in a single tissue, all monocytes/macrophages in the body are activated in this situation including immune cells circulating in the vasculature [

22,

23]. These cells may have occasionally taken up oxidized LDL cholesterol, e.g. in case of hypercholesterolemia [

24,

25]. The penetration of these activated lipid-laden monocytes/macrophages into the vessel wall induced by other trigger mechanisms (e.g. hypertension, hyperglycemia, etc.) is the immunological basis for the development of atherosclerosis [

26].

The correlations described above already give an idea of why people who are overweight, especially during weight gain, are prone to hypertension, lipid disorders, insulin resistance and atherosclerosis [

27]. The situation becomes even more serious when an inherited type 2 diabetes mellitus is developing, which turns this physiology into the pathophysiology of a complex metabolic and vascular disease.

Pathophysiological Aspects of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

According to all available current genetic studies, type 2 diabetes mellitus is mainly due to hereditary disorders of ß-cell dysfunction [

28,

29]. While the general public community is often assuming that an unhealthy lifestyle leads to diabetes, it can be taken from the entire literature that only individuals, who carry certain genes associated with ß-cell dysfunction, will ultimately develop type 2 diabetes [

29]. Otherwise, subjects will become obese and probably develop orthopedic problems as well as cardiovascular symptoms at some point. In our experience, a healthy lifestyle can, however, significantly delay the manifestation of diabetes.

In type 2 diabetes, several secretion disorders of the ß-cells are in the foreground. According to current data, the of physiological pulsatility of insulin secretion and the first insulin response to the meal fail as first indications for diabetes (timing secretion disorder) [

30,

31,

32]. Instead of releasing an insulin peak six times per hour, insulin secretion takes place in a "steady flow" ("stage I of ß-cell dysfunction" [

33,

34]). As a result, the protective effect of insulin in microcirculation fails [

17]. This could be one reason why people with diabetes with very good glycemic control can develop microcirculatory disorders after sufficiently long disease duration, especially if other risk factors are also present [

35]). Due to the insulin resistance-mediated increased insulin requirement, "hyperinsulinemia" (quantitative secretion disorder, stage II of ß-cell dysfunction) is known to occur [

34], which subsequently leads to exhaustion of the cleavage capacities of the ß-cells and consecutively to a release of proinsulin in addition to insulin (qualitative secretion disorder; stage III of ß-cell dysfunction) (

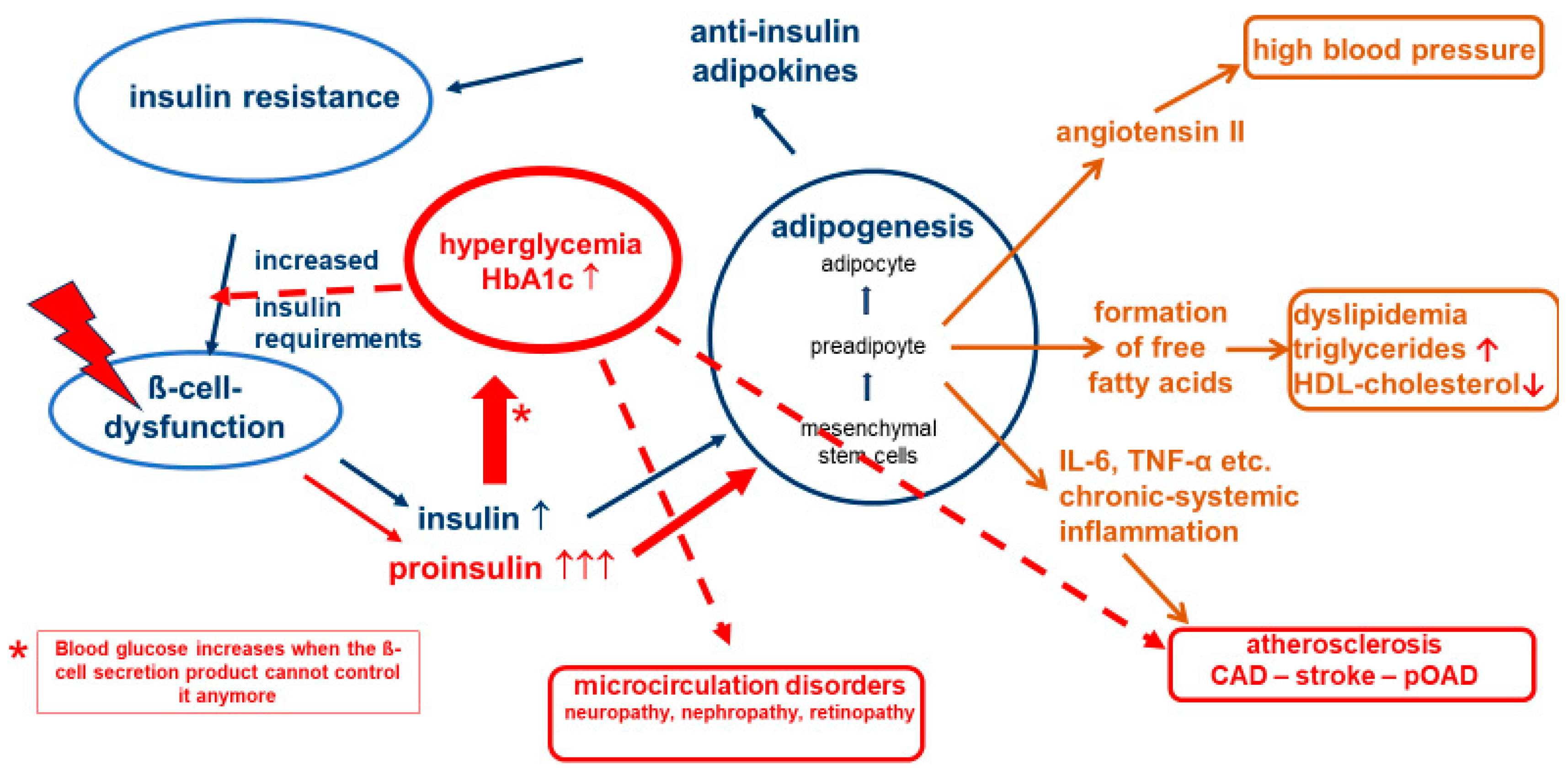

Figure 2) [

34].

Proinsulin, the precursor of insulin in the cellular insulin production process, is a non-physiological hormone that can also lower blood sugar, but only with 10-20% of the effectiveness of insulin [

36]. At the same time, it has the same lipogenetic action as insulin [

11]. On a molecular level, 5 to 10 times more proinsulin than insulin is needed to control blood glucose, which can in turn further increase the negative effects of adipokines on the body. In this situation, the blood glucose-lowering effect of proinsulin can help to maintain normoglycemia, while the other pathological processes continue unabated. One of us (APF) has described this contradictory state of "normoglycemic" diabetes almost two decades ago, together with other authors, and referred to it at the time as "cardiodiabetes" or "vascular diabetes" [

37]. In this phase, a competitive race takes place in the body: is there still enough time for the (blood glucose-based) diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, or does a fatal macrovascular event occur beforehand? The correlations described also explain why manifest atherosclerotic vascular changes are already diagnosed in many affected people when type 2 diabetes mellitus is first diagnosed [

2,

38].

Hyperglycemia in turn increases the insulin demand and further boosts insulin production, which accelerates the vicious circle of this pathophysiology. This underlines the need for good blood glucose control. If blood glucose is not consistently normalized, glucose toxicity leads to a significant acceleration in the development of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Our approach to achieve a stable and non-progressive long-term glycemic control is to treat with lifestyle and pharmaceutical drugs and/or drug combinations guided by a panel of functional biomarkers determining the individual degree of severity of the underlying disease deteriorations. It is of note that usually one of the deteriorations can be the predominant “driver” of the disease pathology, which can also lead to different clinical appearance (phenotypes).

Why Phenotyping?

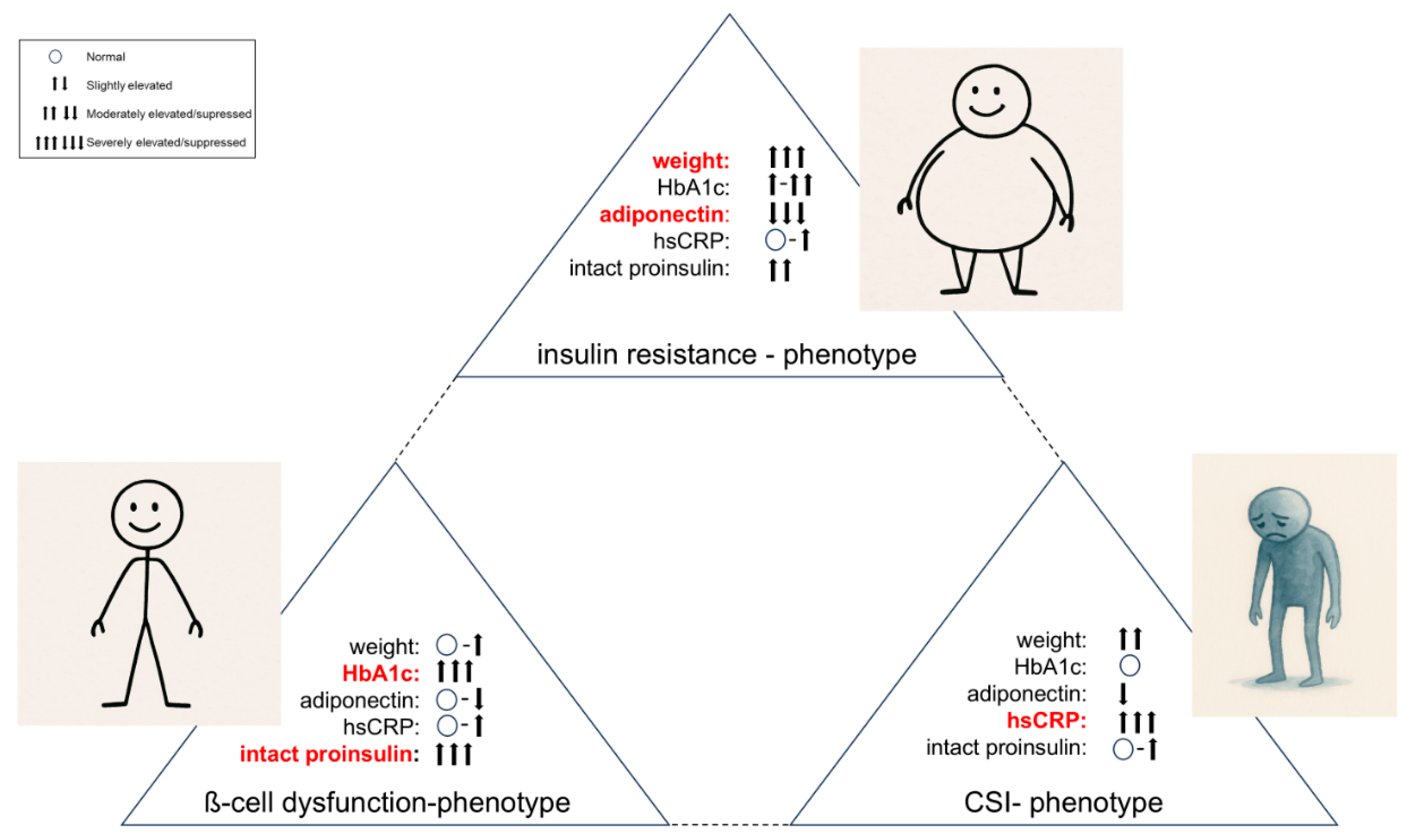

The basic disorders described above (ß-cell dysfunction, insulin resistance, visceral adipose tissue activity, chronic systemic inflammation - hereafter “CSI”) can be present in different stages and with different degrees of severity, which leads to different clinical phenotypes (

Figure 3).

The phenotype, which is primarily driven by ß-cell dysfunction (BCD-Phenotype), shows a poor response to guideline-based diabetes therapy. The people affected are often rather slim or only slightly overweight and usually have poor blood glucose and HbA1c values until insulin is finally used after guideline-compliant therapy escalation.

The insulin resistance-driven phenotype (IR-Phenotype) presents significant obesity, difficult-to-treat hypertension and often has already manifest and systemic atherosclerosis.

One extreme phenotype is certainly the normoglycemic person with "cardiodiabetes", who is often slightly overweight and presents clinically with arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia and hyperuricaemia (CSI-driven phenotype). This phenotype is currently not recognized as diabetes-related disease, as it does not fulfill the gliucose criteria for diabetes diagnosis. It is therefore only treated symptomatically.

In our experience, the phenotype of each person with diabetes lies individually between these three extremes and it is difficult to consider that a glucocentric and solely HbA1c-fixed escalating standard approach (diet & lifestyle → metformin → metformin & another antidiabetic drug → metformin & two other antidiabetic drugs → insulin & other antidiabetic drugs, [

39]) should be able to treat these diverse clinical pictures so efficiently that microcirculatory complications and macrovascular events can be prevented. In any case, according to current data, guideline-based HbA1c-controlled standard therapy does not really lead to a reduction in the main causes of death in people with diabetes (heart attack and stroke). Even when HbA1c treatment targets are achieved, it is known that diabetes usually progresses and often leads to final macrovascular endpoints [

2,

3,

4,

5]. We are trying to avoid this fatal development with our personalized treatment approach that is based on a panel of biochemical and clinical parameters as provided in

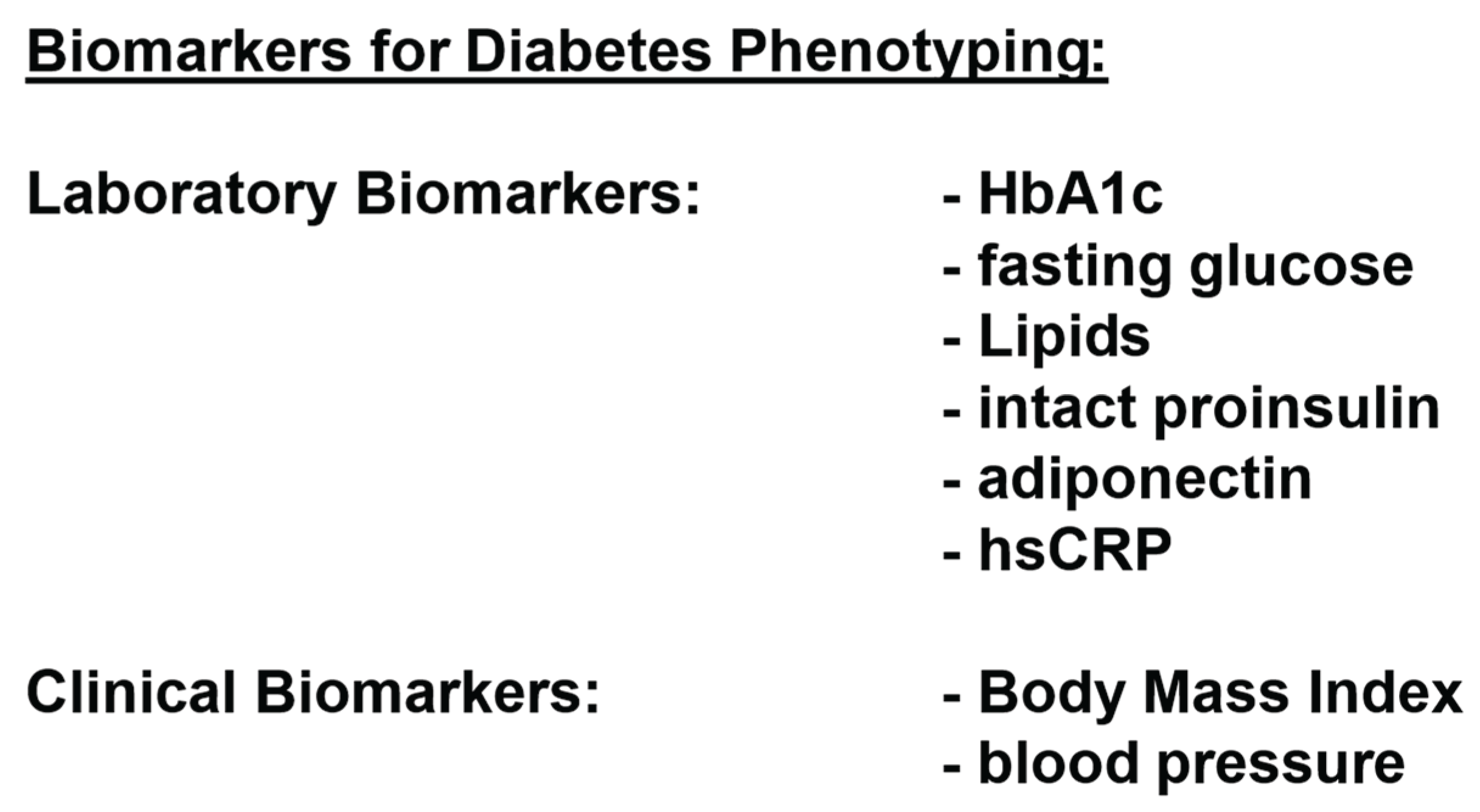

Figure 4.

How to Phenotype Effectively?

The classification of patients with type 2 diabetes based on the classic clinical and laboratory markers (HbA1c, glucose, lipids, BMI and blood pressure) is a classification according to symptoms and provides virtually no insight into the underlying pathophysiological disorders (insulin resistance, ß-cell dysfunction, adipogenesis and CSI). Together with co-authors, one of us (APF) published the biomarker concept as shown in

Figure 4 over 15 years ago, and we have been using it regularly in our practice ever since then [

40].

The assessment of ß-cell dysfunction is of particular interest to us, as more and more drugs have been developed to protect the ß cells or maintain their functionality, such as GLP-1 analogs or DPPIV inhibitors.

In addition to the conventional means of assessing ß-cell function and insulin resistance (e.g. HOMA score or meal-related insulin/C-peptide secretion), we use the determination of intact proinsulin (iPI) in the fasting state or under stress to determine the extent of ß-cell dysfunction and macrovascular risk. iPI, together with insulin or C-peptide, is an indicator of the overall remaining production capacity and production quality of the ß-cells. There are numerous reports from randomized, prospective long-term studies with large cohort numbers proving that iPI is not only a valid risk indicator for an imminent diabetes manifestation or for macrovascular events [review in 41], but must even be regarded as a cardiovascular risk factor [

36,

42]. When proinsulin binds to insulin receptors at the vessel wall, this leads to atherogenic activation of MAP kinase in the endothelium with release of atherogenic inflammatory factors (e.g. endothelin I) [

17]. Treatment with high doses of intact proinsulin in the context of earlier pharmaceutical product development led, among other things, to massive and uncontrolled secretion of plasminogen activator-inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) from visceral adipose tissue [

42,

43]. This cytokine is known to block the physiologically necessary thrombolysis [

44]. After several unexplainable and two fatal macrovascular events had occurred in patients with new-onset type 1 and type 2 diabetes during phase II of this drug development, the development of proinsulin as an antidiabetic agent was discontinued [

36].

The determination of an elevated fasting iPI in a patient with normal glucose values is in any case indicative of ß-cell dysfunction and clinically relevant insulin resistance [

45], especially in the CSI-driven phenotype, which can e.g. be diagnosed by measuring elevated iPI but normal glucose levels. In terms of differential diagnosis, elevated fasting iPI values otherwise only occur in the case of a (very rare) proinsulinoma [

46,

47] or in the early manifestation phase of type 1 diabetes [

48].

Adiponectin is another physiologically important adipokine, although it is produced in mature adipose tissue (i.e. not in preadipocytes) and in the connective tissue. It is known to increase insulin sensitivity in the liver and periphery and to have vaso-protective and anti-atherosclerotic effects [

49,

50]. In visceral adipogenesis, adiponectin secretion is suppressed, which leads, for example, to a further increase in insulin resistance [

51]. In our concept, the suppression of adiponectin is an indicator of the extent of anti-insulin visceral hormonal activity and the lead biomarker in the insulin resistance-driven phenotype.

A detailed analysis of the Framingham study cohort by Ridker et al. showed that CRP concentrations in the near-normal range (< 10 mg/dl) allow independent stratification of cardiovascular risk into three risk groups when measured with a highly sensitive test method (hsCRP) [

52,

53,

54]. This marker has gained worldwide acceptance as a biomarker of chronic systemic inflammation and is part of the risk assessment guidelines of many scientific societies, including the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association [

2,

52]. Values below 1 mg/l describe a low cardiovascular risk, 1 - 3 mg/l indicate a moderate cardiovascular risk, and 3 - 10 mg/l describe a population at high risk. Values above 10 mg/l may occur due to other non-specific infections and inflammation and therefore cannot be used to assess the chronic systemic vascular inflammatory process [

40,

55,

56,

57]. In type 2 diabetes, elevated hsCRP levels are often associated with marked insulin resistance and substantial ß-cell dysfunction. [

57].

With this biomarker information and under consideration of the clinical appearance of the patient, we are able to target the treatment towards the underlying disorders rather than treating the symptom of elevated glucose of elevated HbA1c.

"Blood Glucose Cosmetics" vs. Phenotype-Driven Personalized Therapy

The pathophysiological relationships described above raise the question, how an exclusive therapeutic focus on blood glucose and HbA1c can ultimately improve macrovascular prognosis. Therapeutic guidelines worldwide always recommend starting treatment for type 2 diabetes with diet and lifestyle measures followed by use of metformin as the first line drug [

2,

39,

58]. This is justified by all professional societies with the evidence base regarding the development of late complications in comparative studies. However, it ignores the fact that there are practically no direct comparative studies between metformin and modern antidiabetic drugs. The non-specific insulin secretagogues (sulfonylureas, glinides) reduce blood glucose efficiently, especially at the beginning of therapy, but at the same time accelerate the pathophysiological progression. There is - in our opinion - more than sufficient evidence in the literature that their consistent prescription and use by the patient leads to a significant increase in cardiovascular risk [e.g. 59-61]. To a certain extent, they cause "additional damage", and in a direct comparison with sulfonylureas, metformin therefore performs significantly better [

62].

As a result, metformin has achieved the currently undisputed status of "first-line" medication despite its well-known very high gastrointestinal side-effect profile. Although its mechanism of action (inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis from adipose tissue) also does not really interfere with the pathophysiology of the underlying disorders, and even actively counteracts weight loss, it shows a moderate effect on weight loss in current meta-analyses [

63]. In one of the few direct randomized prospective mono-therapeutic head-to-head comparative studies against a pathophysiologically-oriented antidiabetic agent (rosiglitazone) in the ADOPT study [

64], metformin monotherapy was superior to glimepiride (sulfonylurea) in terms of inhibition of diabetes progression - measured over the time until the need for an additional antidiabetic agent - but performed significantly worse than rosiglitazone. In a direct comparison with dulaglutide in the AWARD-3 study, metformin also showed poorer treatment results [

65]. It can, therefore, not be expected that the progression of type 2 diabetes can generally be prevented with metformin as first-line therapy.

In summary, type 2 diabetes is a highly complex disease driven by several interlocking underlying disorders, which can be present in varying degrees of severity. This can lead to very individual clinical phenotypes, none of which are currently optimally treated by standardized glucocentric therapy. The method of phenotyping using functional biomarkers, which we have described in this discussion paper, and which has been applied in our practice for more than 15 years now, opens up the possibility of individual and personalized diabetes therapy. We will present how we treat in our practice and what results we have been able to achieve so far in a consecutive Part 2 of our discussion paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.P. and J.J., writing: A.P. and J.J., original draft preparation: A.P., writing – review and editing: J.J., visualization: A.P. and J.J., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- King KM, Rubin G. A history of diabetes: from antiquity to discovering insulin. Br J Nurs. 200; 12(18):1091-5. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Care in Diabetes 2024, Diabetes Care 2024; 47(Suppl.1): S1-S308.

- Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group; Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2545–2559.

- Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al.. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:129–139. [CrossRef]

- Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al.; ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet; 2007; 370:829–840.

- Pfützner A. Glukosekosmetik“ vs. Personalisierte Diabetestherapie Teil 1: Funktionelle Phänotypisierung als Grundlage einer individuellen Typ 2 Diabetes Therapie. Diabetes Stoffw. Herz 2023; 32:299-306.

- Pfützner A.: „Glukosekosmetik“ vs. personalisierte Diabetestherapie Teil 2: Personalisierte Therapie (Standard of Care plus). Diabetes Stoffw. Herz 2024; 33:11-19.

- Hauner H, Löffler G. Adipose tissue development: the role of precursor cells and adipogenic factors. Part I: Adipose tissue development and the role of precursor cells. Klin Wochenschr. 1987; 65:803-11.

- Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM, Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. 2006; Nature 444:847-853. [CrossRef]

- Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell. 2014; 156:20-44.

- Pfützner A., Schipper D., Pansky A., Kleinfeld C., Rooitzheim B., Tobiasch E.: Mesenchymal Stem Cell Differentiation into Adipocytes is Equally Induced by Insulin and Proinsulin in vitro. Int. J. Stem Cell 2017; 10:154-159. [CrossRef]

- Das D, Shruthi NR, Banerjee A, Jothimani G, Duttaroy AK, Pathak S. Endothelial dysfunction, platelet hyperactivity, hypertension, and the metabolic syndrome: molecular insights and combating strategies. Front Nutr. 2023; 10:1221438. [CrossRef]

- World Obesity Atlas 2022 (last access on 03/31/2024) https://www.worldobesity.org/resources/resource-library/world-obesity-atlas-2022.

- Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME. Obesity, kidney dysfunction and hypertension: mechanistic links. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019; 15367-385. [CrossRef]

- Lafontan M. Advances in adipose tissue metabolism. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008; 32(Suppl 7):S39-51.

- WHO (last access 03/31/2024) https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death.

- Forst T, Hohberg C, Pfützner A. Cardiovascular effects of disturbed insulin metabolism in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes patients. Horm. Metab. Res. 2009; 41:123 – 131. [CrossRef]

- Andersson CX, Gustafson B, Hammarstedt A, Hedjazifar S, Smith U. Inflamed adipose tissue, insulin resistance and vascular injury. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008; 24:595-603. [CrossRef]

- Murdolo G, Smith U. The dysregulated adipose tissue: a connecting link between insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus and atherosclerosis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis.1 2006; 6(Suppl.1):S35-8. [CrossRef]

- Dandona P, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A, Mohanty P. Endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and diabetes. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2004; 5:189-97.

- Dandona P, Aljada A, Ghanim H, Mohanty P, Tripathy C, Hofmeyer D, Chaudhuri A. Increased plasma concentration of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and MIF mRNA in mononuclear cells in the obese and the suppressive action of metformin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004; 89:5043-7. [CrossRef]

- Ghanim H, Aljada A, Hofmeyer D, Syed T, Mohanty P, Dandona P. Circulating mononuclear cells in the obese are in a proinflammatory state. Circulation; 2004; 110:1564-71. [CrossRef]

- Ringseis R, Eder K, Mooren FC, Krüger K. Metabolic signals and innate immune activation in obesity and exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2015; 21:58-68.

- Mushenkova NV, Bezsonov EE, Orekhova VA, Popkova TV, Starodubova AV, Orekhov AN. Recognition of Oxidized Lipids by Macrophages and Its Role in Atherosclerosis Development. Biomedicines, 2021; 9:915-923. [CrossRef]

- Orekhov AN, Nikiforov NG, Sukhorukov VN, Kubekina MV, Sobenin IA, Wu WK, Foxx KK, Pintus S, Stegmaier P, Stelmashenko D, Kel A, Gratchev AN, Melnichenko AA, Wetzker R, Summerhill VI, Manabe I, Oishi Y. Role of Phagocytosis in the Pro-Inflammatory Response in LDL-Induced Foam Cell Formation; a Transcriptome Analysis. Int J Mol Sci.; 2021; 21:817-821. [CrossRef]

- Boyle JJ. Macrophage activation in atherosclerosis: pathogenesis and pharmacology of plaque rupture. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2003; 3:63-68. [CrossRef]

- Freeman AM, Acevedo LA, Pennings N. Insulin Resistance. 2023 Aug 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–. PMID: 29939616.

- Alford FP, Henriksen JE, Rantzau C, Vaag A, Hew LF, Ward GM, Beck-Nielsen H. Impact of family history of diabetes on the assessment of beta-cell function. Metabolism. 1998; 47:522-8. [CrossRef]

- O’Rahilly S.P., Nugnet Z, Rudenski A.S., Hosker J.P., Burnett M.A., Darling P., Turner R.C. Beta-cell dysfunction, rather than insulin insensitivity, is the primary defect in familial type 2 diabetes. 1986; Lancet 2:360-364. [CrossRef]

- Brunzell J.D., Robertson R.P., Lerner R.L., Hazzard W.R., Ensinck J.W., Bierman E.L. Relationships between fasting plasma glucose levels and insulin secretion during intravenous glucose tolerance tests. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1976; 42:222–229. [CrossRef]

- Lang D.A., Matthews D.R., Burnett M., Turner R.C. Brief, irregular oscillations of basal plasma insulin and glucose concentrations in diabetic man. Diabetes. 10981; 30:435–439.

- Polonsky K.S., Given B.D., Hirsch L.J., Tillil H., Shapiro E.T., Beebe C. Abnormal patterns of insulin secretion in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1988; 318:1231–1239. [CrossRef]

- Wahren J, Kallas A. Loss of Pulsatile Insulin Secretion: A Factor in the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes? Diabetes 2012; 61:2228-2229. [CrossRef]

- Pfützner A., Pfützner A.H., Larbig M., Forst T.: Role of intact proinsulin in diagnosis and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab. Technol. Ther. 2004; 6:405-412. [CrossRef]

- Toyama T, Shimizu M, Yamaguchi T, Kurita H, Morita T, Oshima M, Kitajima S, Hara A, Sakai N, Hashiba A, Takayama T, Tajima A, Furuichi K, Wada T, Iwata Y. A comprehensive risk factor analysis using association rules in people with diabetic kidney disease. 2023; Sci Rep. 3:11690. [CrossRef]

- Galloway JA, Hooper SA, Spradlin CT, Howey DC, Frank BH, Bowsher RR, Anderson JH: Biosynthetic human proinsulin. Review of chemistry, in vitro and in vivo receptor binding, animal and human pharmacology studies, and clinical trial experience. Diabetes Care 1992; 15:666-692. [CrossRef]

- Kintscher U., Marx N., Koenig W., Pfützner A., Forst T., Schnell O.: Kardiodiabetologie: Der aktuelle Stand – Epidemiologie, Pathophysiologie, Therapie, Klinik und Praxis. Diabetes Stoffw. Herz 2006; 15:31-45.

- Ruigomez A, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Presence of diabetes related complication at the time of NIDDM diagnosis: an important prognostic factor. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998; 14:439-45. [CrossRef]

- Bundesärztekammer (BÄK), Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF). Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Typ-2-Diabetes – Teilpublikation der Langfassung, 2. Auflage. Version 1. 2021 (last access on 03/31/2024) https://www.ddg.info/fileadmin/user_upload/05_Behandlung/01_Leitlinien/Evidenzbasierte_Leitlinien/2021/diabetes-2aufl-vers1.pdf.

- Pfützner A., Weber M.M., Forst T.: A Biomarker Concept for Assessment of Insulin resistance, ß-Cell Function and Chronic Systemic Inflammation in Type 2 Diabetes mellitus. Clin Lab. 2008; 54;485-490.

- Pfützner A, Manessis A, Hanna MR, Lewin J. Increased Intact Proinsulin in the Oral Glucose Challenge Sample is an Early Indicator for Future Type 2 Diabetes Development – Case Reports and Evidence from the Literature. Clin. Lab. 2020; 66:923-92. [CrossRef]

- Nordt TK, Bode C, Sobel BE. Stimulation in vivo of expression of intra-abdominal adipose tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor type I by proinsulin. Diabetologia, 2002; 44:1121-4. [CrossRef]

- Panahloo A, Mohamed-Ali V, Gray RP, Humphries SE, Yudkin JS. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) activity post myocardial infarction: the role of acute phase reactants, insulin-like molecules and promoter (4G/5G) polymorphism in the PAI-1 gene. Atherosclerosis 2003; 168:297-304. [CrossRef]

- Munkvad S, Jespersen J, Gram J, Kluft C. Interrelationship between coagulant activity and tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) system in acute ischaemic heart disease. Possible role of the endothelium. J Intern Med; 1990; 228:361-6.

- Pfützner A, Kunt T, Mondok A, Pahler S, Konrad T, Luebben G, Forst T. Fasting Intact Proinsulin is a Highly Specific Predictor of Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:682-687. [CrossRef]

- Fadini GP, Maran A, Valerio A et al. Hypoglycemic syndrome in a patient with proinsulin-only secreting pancreatic adenoma (proinsulinoma). Case Rep Med., 20011; 2011:930904. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pevida B, Idoate MÁ, Fernández-Landázuri S, Varo N, Escalada J. Hypoglycemic Syndrome without Hyperinsulinemia. A Diagnostic Challenge. Endocr Pathol.; 2016; 27:50-4. [CrossRef]

- Bolinder J, Fernlund P, Borg H, Arnqvist HJ, Björk E, Blohmé G, Eriksson JW, Nyström L, Ostman J, Sundkvist G. Hyperproinsulinemia segregates young adult patients with newly diagnosed autoimmune (type 1) and non-autoimmune (type 2) diabetes. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2005; 65:585-94. [CrossRef]

- Schöndorf T, Maiworm A, Emission N, Forst T, Pfützner A. Biological Background and Role of Adiponectin as Marker for Insulin Resistance and Cardiovascular Risk. Clin Lab. 2005; 51:489-94.

- Trujillo ME, Scherer PE. Adiponectin - journey from an adipocyte secretory protein to biomarker of the metabolic syndrome J Intern Med. 2005; 257:167-175.

- Bastard JP, Maachi M, Lagathu C, Kim MJ, Caron M, Vidal H, Capeau J, Feve B. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006; 17:4-12.

- Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO 3rd, Criqui M, Fadl YY, Fortmann SP, Hong Y, Myers GL, Rifai N, Smith SC Jr, Taubert K, Tracy RP, Vinicor F; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; American Heart Association. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice. A statement for health care professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2003; 107:499-511.

- Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: potential adjunct for global risk assessment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation; 2001; 103:1813-1818.

- Ridker PM, Wilson PF, Grundy SM. Should C-reactive protein be added to metabolic syndrome and to assessment of global cardiovascular risk. Circulation 2004; 109:2818-2815. [CrossRef]

- Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, Eda S, Eiriksdottir G, Rumley A, Lowe GD, Pepys MB, Gudnason V. C-reactive protein and other circulation markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:1387-1397. [CrossRef]

- Pfützner A., Forst T.: HsCRP as cardiovascular risk marker in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diab. Technol. Ther. 2006; 8:28 – 36.

- Pfützner, A. , Standl E., Strotmann H.J., Schulze J., Hohberg C., Lübben G., Pahler S., Schöndorf T., Forst T.: Association of hsCRP with Advanced Stage ß-Cell Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes mellitus. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2006; 44:556-560.

- Landgraf R, Aberle J, Birkenfeld AL, Gallwitz B, Kellerer M, Klein HH, Müller-Wieland D, Nauck MA, Wiesner T, Siegel E. Therapie des Typ-2-Diabetes [Treatment of type 2 diabetes]. Diabetologie. Apr 27:1–38. German. (Epub ahead of print), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Forst T, Hanefeld M, Jacob S, Moeser G, Schwenk G, Pfützner A, Haupt A. Association of sulphonylurea treatment with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2013; 10:302-314. [CrossRef]

- Simpson SH, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, Eurich DT, Johnson JA. Dose-response relation between sulfonylurea drugs and mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ. 2006; 174:169-74.

- Volke V, Katus U, Johannson A, Toompere K, Heinla K, Rünkorg K, Uusküla A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of head-to-head trials comparing sulfonylureas and low hypoglycaemic risk antidiabetic drugs. BMC Endocr Disord. 2022; 22:251. [CrossRef]

- Johnson JA, Majumdar SR, Simpson SH, Toth EL: Decreased mortality associated with the use of metformin compared with sulfonylurea monotherapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:2244–2248.

- Haddad F, Dokmak G, Bader M, Karaman R. A Comprehensive Review on Weight Loss Associated with Anti-Diabetic Medications. Life (Basel) 2023; 13:1012. [CrossRef]

- Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, Herman WH, Holman RR, Jones NP, Kravitz BG, Lachin JM, O'Neill MC, Zinman B, Viberti G: Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2427–2443. [CrossRef]

- Umpierrez G, Tofé Povedano S, Pérez Manghi F, Shurzinske L, Pechtner V. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide monotherapy versus metformin in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD-3). Diabetes Care. 2014; 37:2168-76. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).