1. Introduction

Patients who remain in intensive care units (ICUs) for extended periods face a high disease burden and increased risks of illness and death. Factors contributing to extended ICU stays include multiple organ failure, unstable circulation, delirium, prolonged ventilator weaning with post-extubation dysphagia (PED), and the presence of a tracheal cannula (TC), which can complicate transfers to other wards or care facilities due to their limited capacity to manage such cases [

1]. Tracheostomized ICU patients experience an even greater burden, with longer hospital and ICU stays, higher mortality rates, and a greater chance of being discharged to a care facility. These patients often have severe underlying conditions, and tracheostomy may prompt a reassessment of patient goals and advanced care planning [

2]. Strong respiratory function, demonstrated by powerful cough reflexes and efficient secretion control, is reported as a fundamental predictive factor for successful decannulation [

3]. Ideally, decannulation should occur during or at the conclusion of the patient’s stay in the ICU [

4] to minimize the occurrence of further complications.

A recent national anesthesiology guideline recommends multiprofessional team efforts in order to improve the quality of treatment and shorten the LOS. However, the guideline focuses on the effects of mobilization and thereby on the physiotherapeutic role in the treatment process [

5]. A national [

6] and an international [

7] guideline of intensive care societies both recommend broad staff education and strongly recommend to make speech and language therapy (SLT) available for ICU up to the point that “all patients with a tracheostomy must have communication and swallowing needs assessed by an SLT” [

7]. Especially, SLT and there competencies in tracheostomy and dysphagia management [

8] could provide additional input for intensive care treatment quality beyond their ancestral field of neurologic rehabilitation [

9] and have already demonstrated positive effects on aspects such as pneumonia prevention and length of stay (LOS) in quality management (QM) projects [

10,

11]. Furthermore, there is evidence that the mere application of structured decannulation pathway is able reduce the total time to decannulation [

12].

Hence, we started an

interprofessional

QM project (IQ-ICU) that integrated medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, SLT, and occupational therapy work together to improve the quality of treatment, reduce morbidity and the length of stay (LOS) on

ICU with the respective profession-specific input [

8]. SLT focuses primarily on the aspects of tracheal cannula management and dysphagia. In order to evaluate the effect of IQ-ICU, we retrospectively analyzed patient data one year prior to the implementation phase and compared this historic control group (HC) to an intervention group (IG) one year after the full start of the implemented QM project.

In this paper we will focus on the SLT part of the whole IQ project and its effect on endpoints associated with tracheostomy and dysphagia (IQ-ICU-SLT). The primary aim of the SLT was the fastest possible decannulation with maximum patient safety, and with that ideally a reduction of LOS on ICU.

2. Materials and Methods

Before the start of the IQ-ICU project, there were no specific SOPs dealing with dysphagia or tracheal cannula management for intensive care medicine. Decisions regarding oral feeding or decannulation were based on clinical experience mostly of the nurses and physicians. Only physiotherapy was part of the daily routine. SLT was only available upon specific requests of the ICU physicians in exceptional cases.

Therefore, we decided to implement a comprehensive concept with specific measurements for SLT treatment, focusing on cannula management and dysphagia, on a postoperative ICU of a German university hospital that operates up to 43 beds.

2.1. Descrition of the Overall IQ-ICU Concept

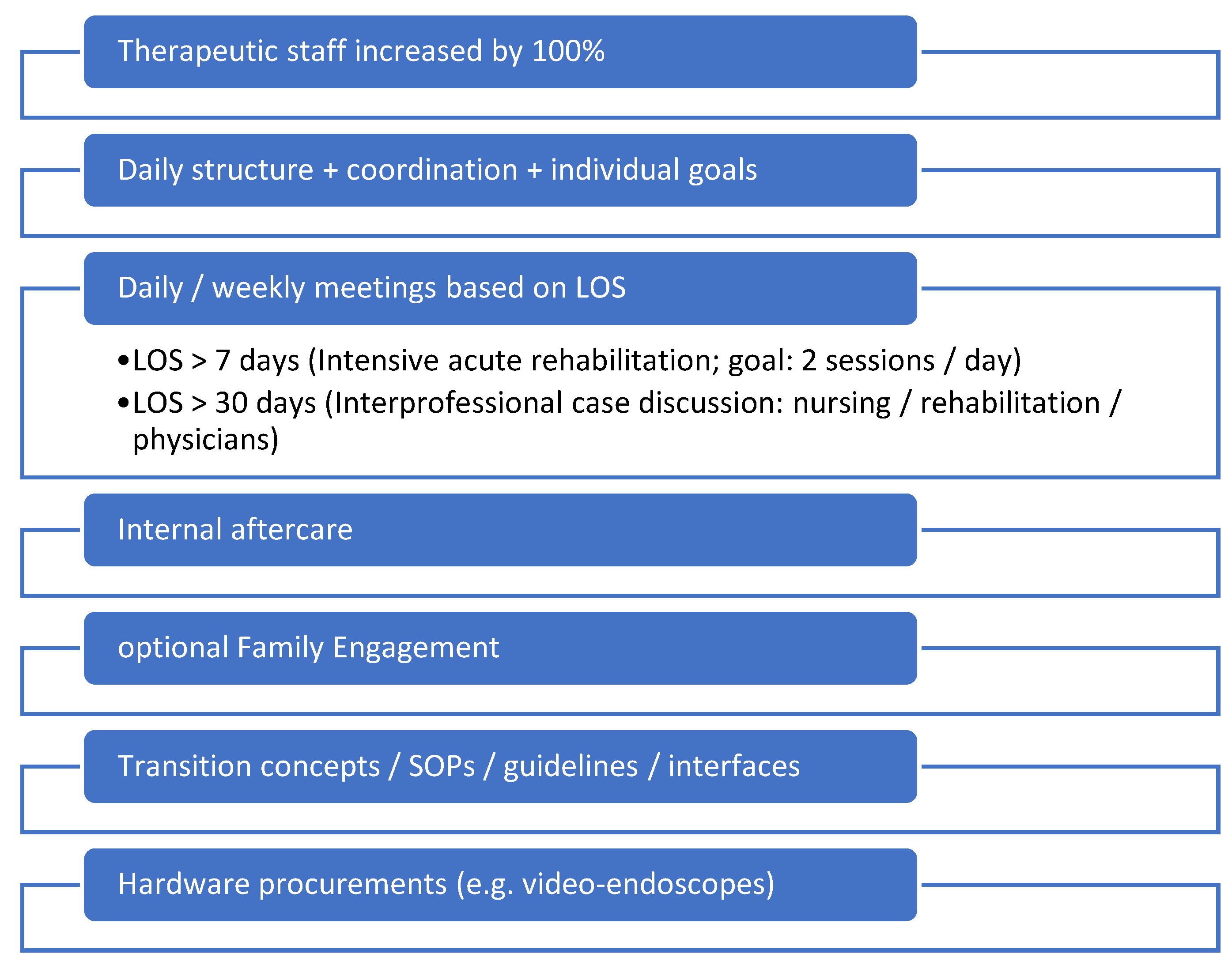

No changes were made regarding the general intensive medical care approach of the physicians. Staffing levels in the therapy area were doubled so that therapy sessions could take place twice a day. An interprofessional Standard Operation Procedure (SOP) for the collaboration of physiotherapy, SLT, and occupational therapy was created. Furthermore, depending on the LOS a daily interprofessional therapy conference and weekly goal meetings were introduced. The integration of family engagement was executed wherever feasible, and adequate supplies (for example video endoscopes for flexible evaluation of swallowing and to detect readiness for decannulation) were procured (compare

Figure 1 for the key points of the IQ-ICU project). Pharyngeal electrical stimulation (PES) was considered, but since the ICU patients do not surely meet the necessary etiologies for its application (in Europe its neurogenic dysphagia), we decided against PES at the first stage of the IQ-ICU project even though it showed superior results for faster decannulation [

13].

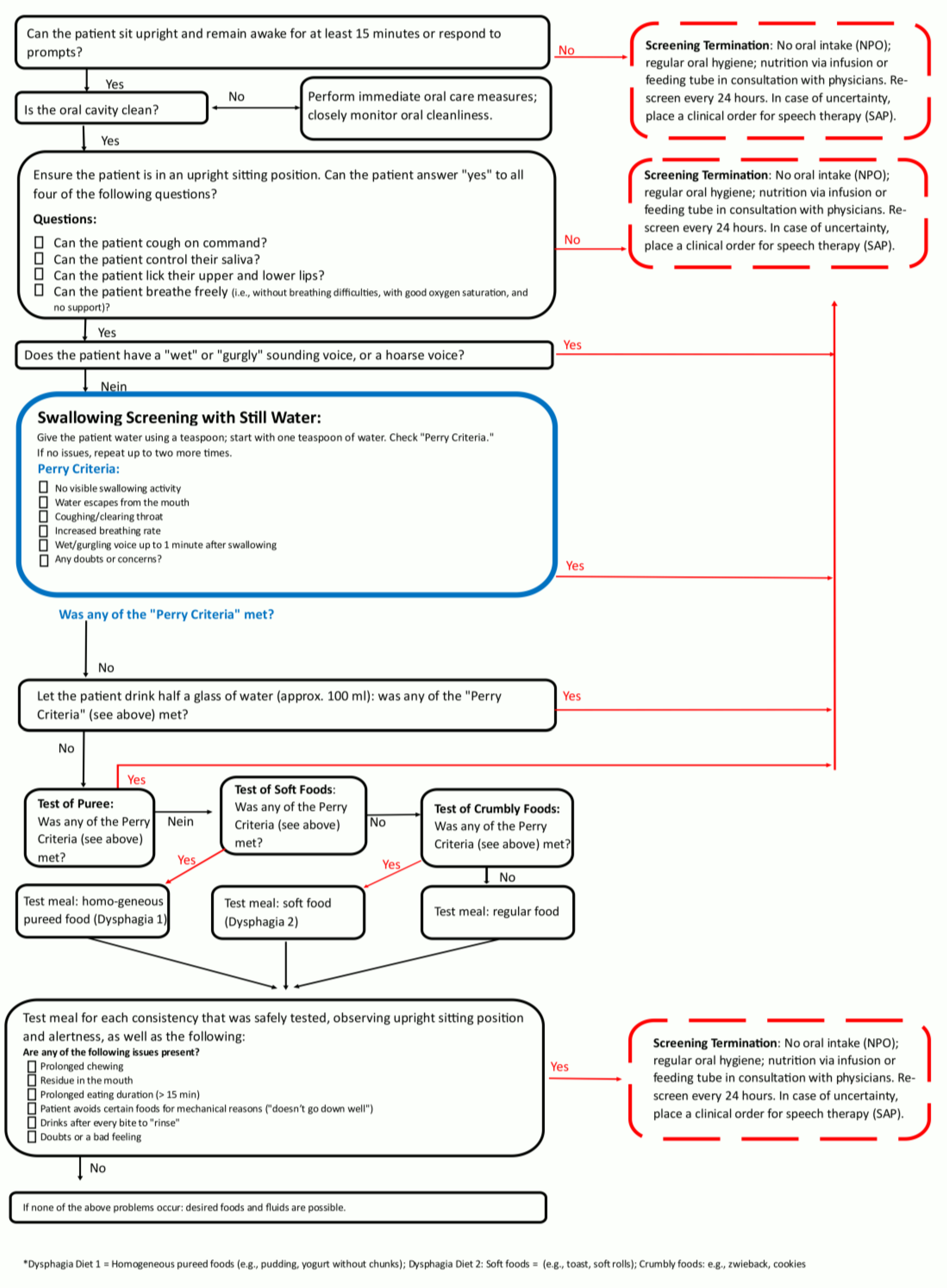

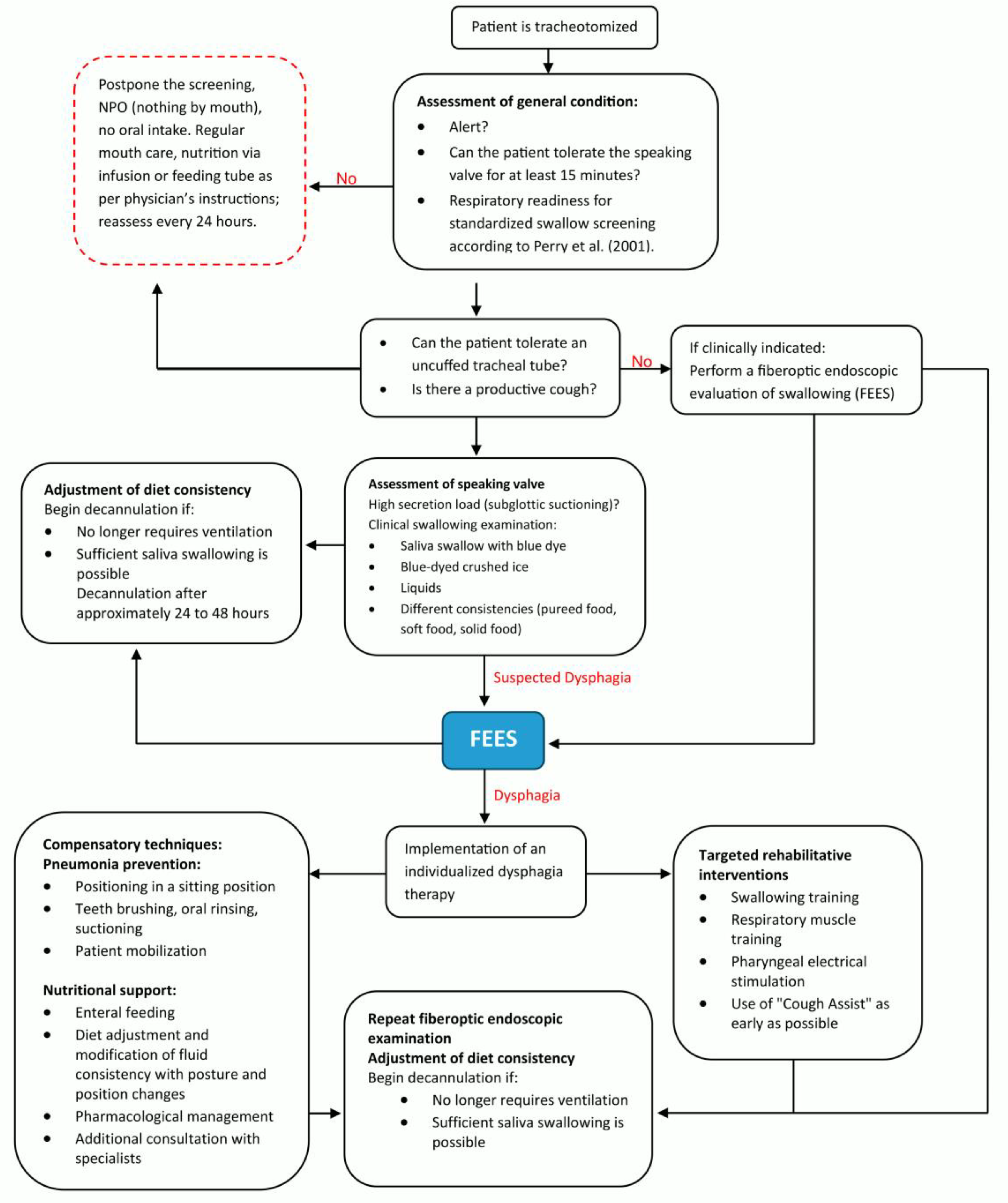

2.2. Descrition of the SLT Concept

A relevant part of the ICU patient care is the tracheostomy management with essential contributions of the SLT team, consisting of +- seven members across the whole intervention period. Two SOPs (the pathways of the SOPs are depicted in

Figure 2 and 3) for dealing with PED patients and for a structured tracheal cannula management based on international expert recommendations (3) were developed for this purpose and were both implemented during in a 3month period at the beginning of 2024. Every team member was trained for the concept. All members are qualified for tracheal cannula management and FEES according to respective curriculums [

14,

15] that are accepted from national and international expert societies (German Society for Swallowing Disorders and European Society for Swallowing Disorders). A further SLT treatment goal was to teach the patients of self-care competence for their cannula (i.e. self suctioning) to the patients. In order to put this into practice, there was a planned SLT staff increase from approximately 0.1 to 0.8 full-time employee equivalents. SLT was allocated to tracheal cannula management if the first assessment of general condition indicated readiness for treatment (see

Figure 3).

2.3. Study Design, Patient Inclusion and Endpoints

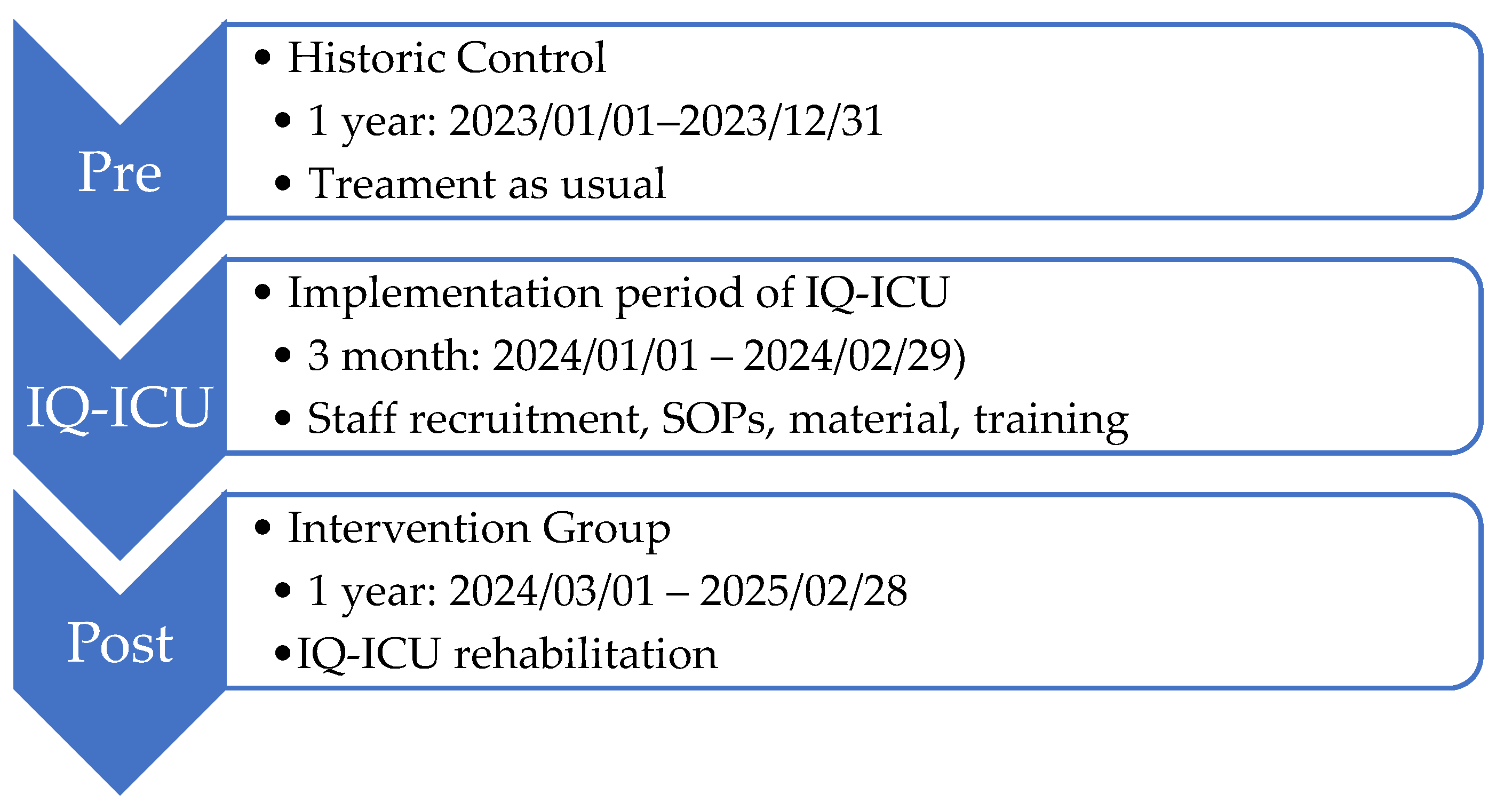

As a basis for comparison of the effects on the intervention group (IG), a historical control (HC) group was created through a retrospective data analysis of the year 2023 (Ethics Committee of the Rhineland-Palatinate Chamber of Physicians: 2024-17433). The whole time period of the comparison was across 24 (+3) months in a non-randomized pre-/post study design (see

Figure 4). The study is registered with the WHO Register for Clinical Trials (DRKS00036084).

We included all patients that underwent tracheostomy during intensive care stay or later during the hospital stay or that already entered the ICU tracheostomized. No additional exclusion criteria were applied. The primary endpoint of the framework project (IQ-ICU) is a composite endpoint, combining morbidity and the length of stay on ICU. Secondary outcomes were morbidity: amongst many others measured by the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score (SOFA, 0-24, organ dysfunction ) [

18], the Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II, 0-163, risk of mortality) [

19], Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS, 0-9, frailty) [

20], functional dependence and independence (Early Rehabilitation Barthel-Index A (-325 - 0) and B, (0 - 100) [

21], and mortality.

As the SLT specific primary outcome (P1) we considered the group differences of: Days with tracheal cannula during the ICU stay. Clinically more relevant, but not solely attributable to SLT, is the LOS on ICU, hence we considered it as a further primary but not SLT specific outcome (P2). SLT specific secondary outcomes were: amount of possible safe decannulations during the ICU stay, given SLT therapy in minutes, amount of performed clinical and endoscopic swallowing examinations and competence of self-care for their cannula (i.e. self suctioning).

This paper specifically analyses the SLT related outcomes and evaluates their influence on the LOS

2.4. Data Acquisition, Aggregation, and Statistic Analyses

Data was collected from two online patient data management systems by two members of the study group (I.N. and L.M.). All patient data were entered into one pseudonymized Excel sheet table. After several mutual meetings and data curation it resulted in a clear to analyze version. All further statistical calculations (either with MS Excel 2016 or SPSS v.29) are based on this final version of the raw data table. For inferential statistics of metric variables we calculated two-sample t-test (two-sided significance) and X2-tests for nominal variables. Additionally, for the most relevant outcomes effect sizes according to Cohen’s D [

22] were provided.

3. Results

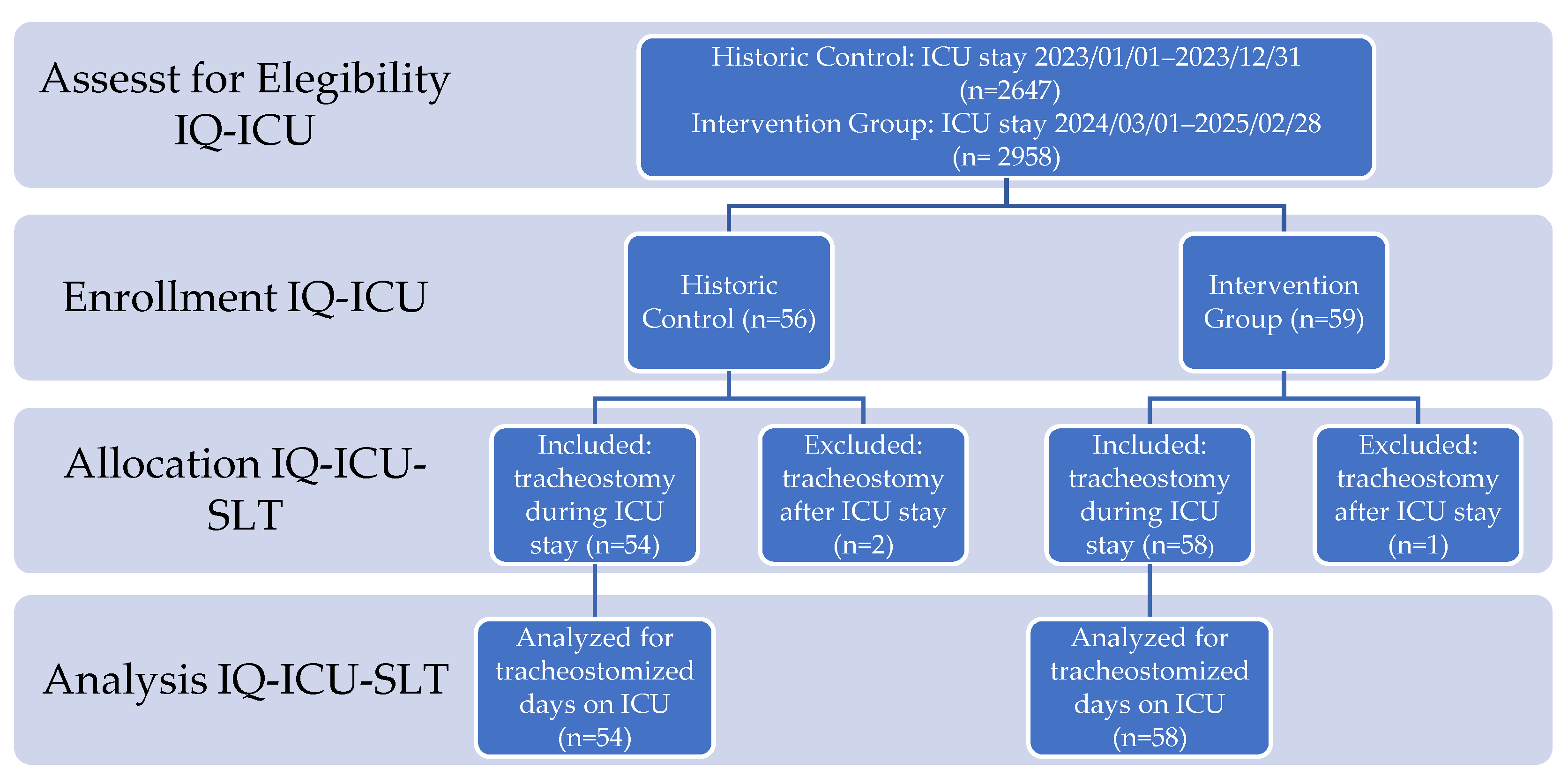

After assessment for eligibility of n=5,605 patients (HC n=2,647; IG n=2,958) we enrolled 115 tracheostomized patients during the investigation period who came from a broad-spectrum, postoperative intensive care unit, allocated n=112 (2%) to IQ-ICU-SLT (HC n=54, IG n=58), and analyzed these cases regarding the SLT specific endpoints (see

Figure 5 for details of enrollment).

3.1. Patient Characteristics After Enrollment

Amongst the most prominent etiologies were heart-vascular surgery and plastic operations on vessels, surgery of the gastrointestinal tract, and organ replacement therapy.

General patient characteristics across both groups such as the mean age in years (HC=65.43, IG=67.75), and BMI (HC=27.0, IG=28.06) appear to be comparable, although sex is unequally distributed with lesser females in the HC (f=29.6%). Regarding clinical characteristics, both group samples show typical values in ICU-related scores. The risk of morbidity (according to SOFA max) was higher in the HC but not unequally distributed for all other scores. In the 20.4% of the patients in the HC and in 10.3% of the patients in the IG (15.18% across both groups) the complication of apoplexy emerged. Mortality across groups was not unequal. Regarding types of tracheostomies, there were more surgical (primary and secondary) tracheostomies in the IG. This difference also resulted in an earlier performed tracheostomy or first day with TC on ICU (patients with prior tracheostomy) in the IG (mean of days: HC=13.93, IG=9.71) All most relevant patient and clinical characteristics can be viewed in

Table 1.

3.2. Results forSLT Specific Primary and Secondary Study Endpoints

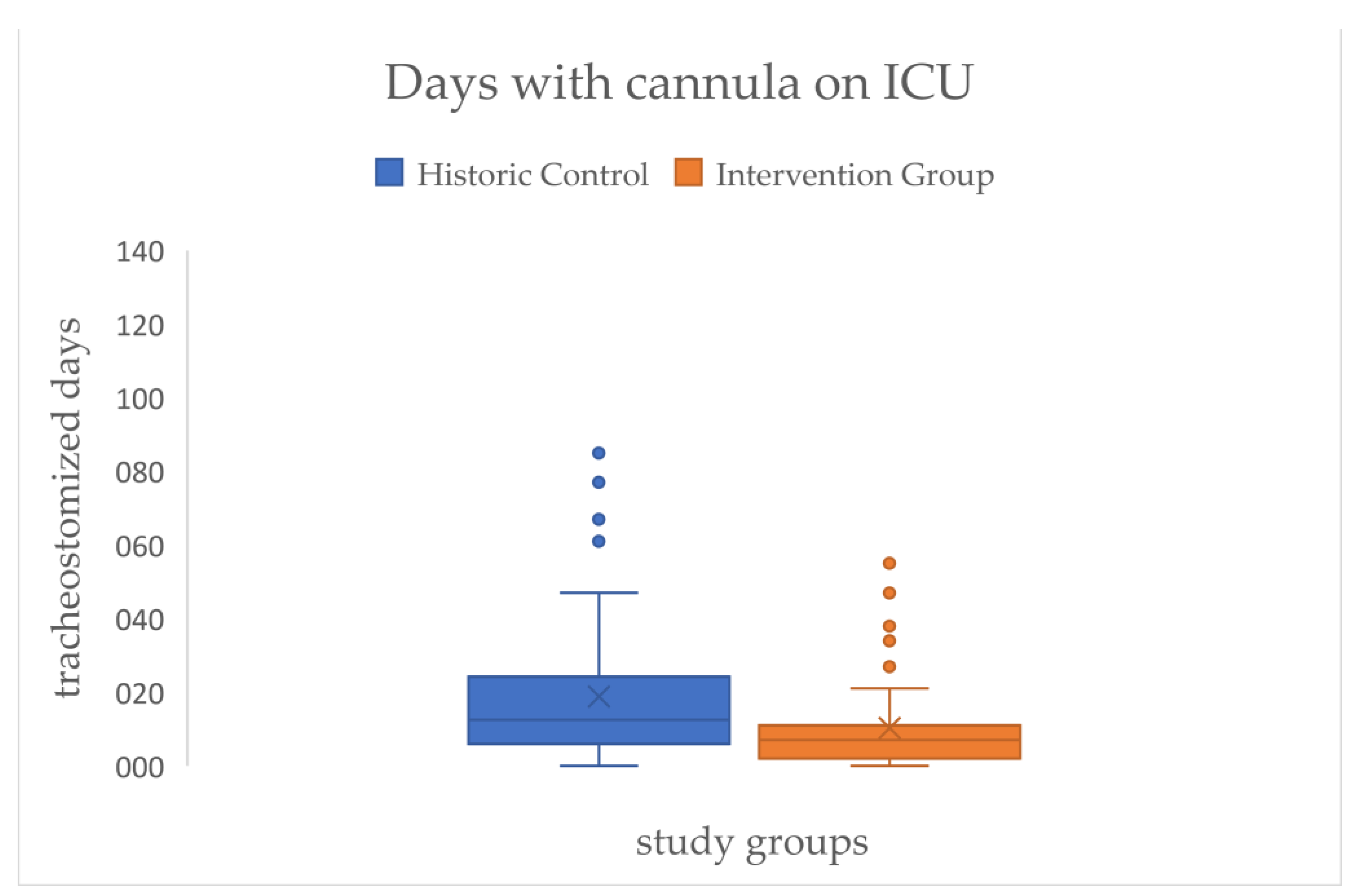

Across all patients, there is a significant effect for the primary outcome of the SLT that resulted in a reduction of the mean time of days with cannula on ICU of approximately eight days (HC=18.85 → IG=10.31) with a medium effect size (d=.54) (see

Figure 6/

Table 2).

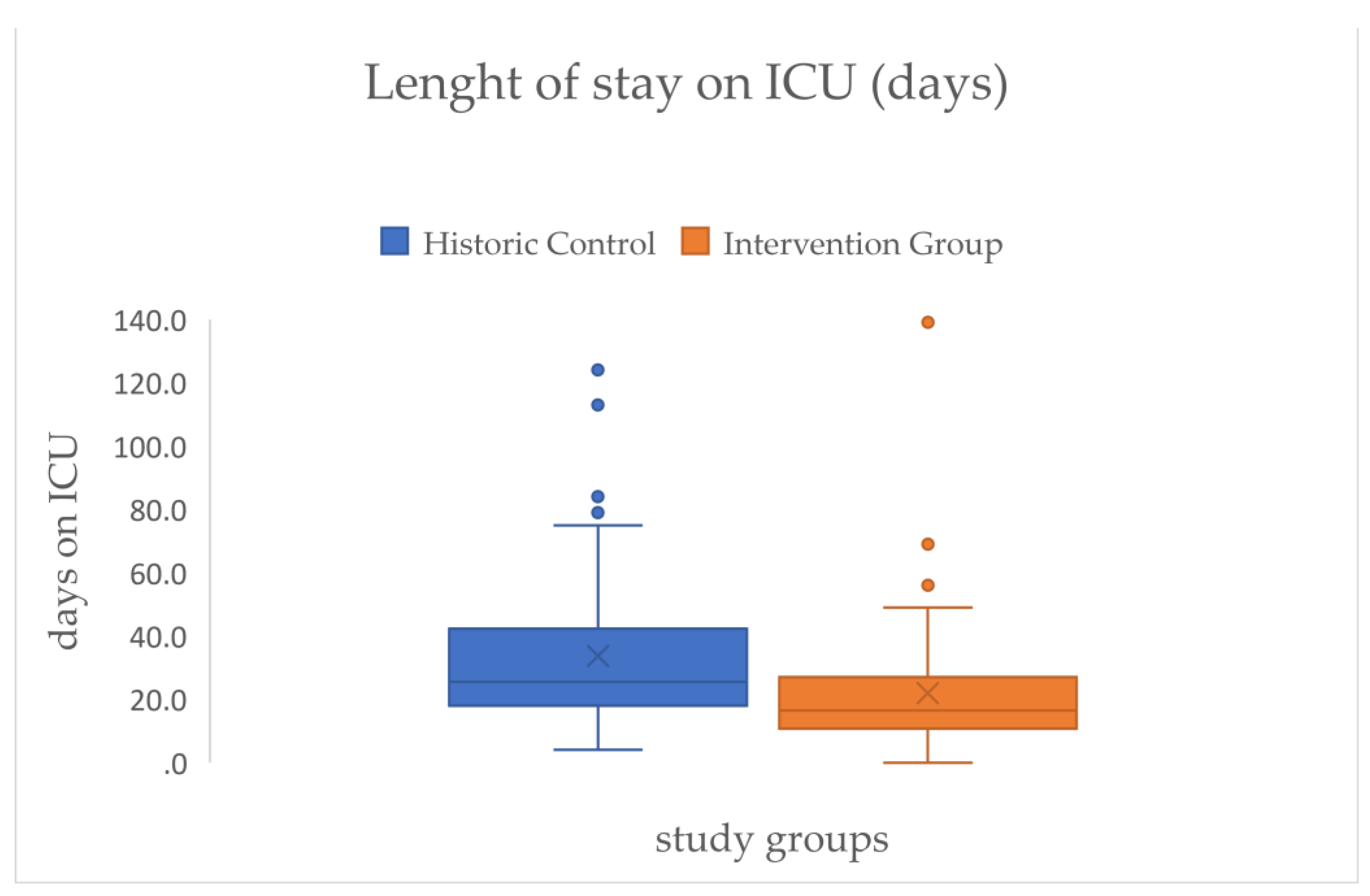

This is linked to the LOS on ICU that shows a comparable effect size (d=.48) and on average a significant reduction of mean days between both groups of approximately twelve days (HC=33.74 → IG=21.94) (see

Figure 7/

Table 2).

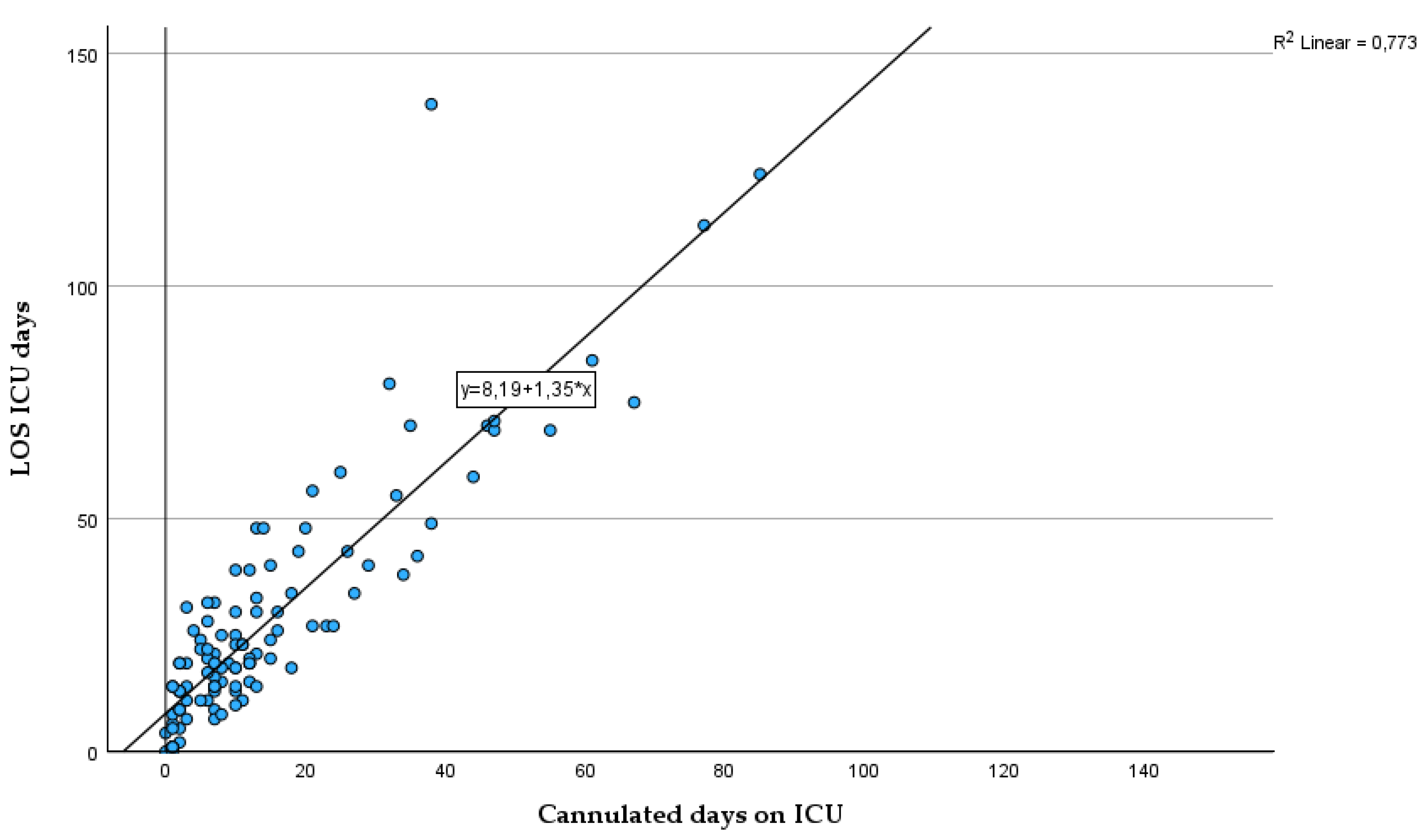

To demonstrate the interdependence of days with cannula and the LOS on ICU we calculated a linear regression with the cannulated days on ICU as a predictor variable for the LOS on ICU. The coefficient of determination showed that 77% (p<.001*) of the variation of the LOS can be explained by days with cannula on ICU, while the rest is explained by some other variables not included.

Figure 8.

Scatterplot of residence time in days of the tracheal cannula (x-axis, independent variable) and length of stay on ICU in days (y-axis, dependent variable) with line of origin, regression line, regression model and information about goodness of fit.

Figure 8.

Scatterplot of residence time in days of the tracheal cannula (x-axis, independent variable) and length of stay on ICU in days (y-axis, dependent variable) with line of origin, regression line, regression model and information about goodness of fit.

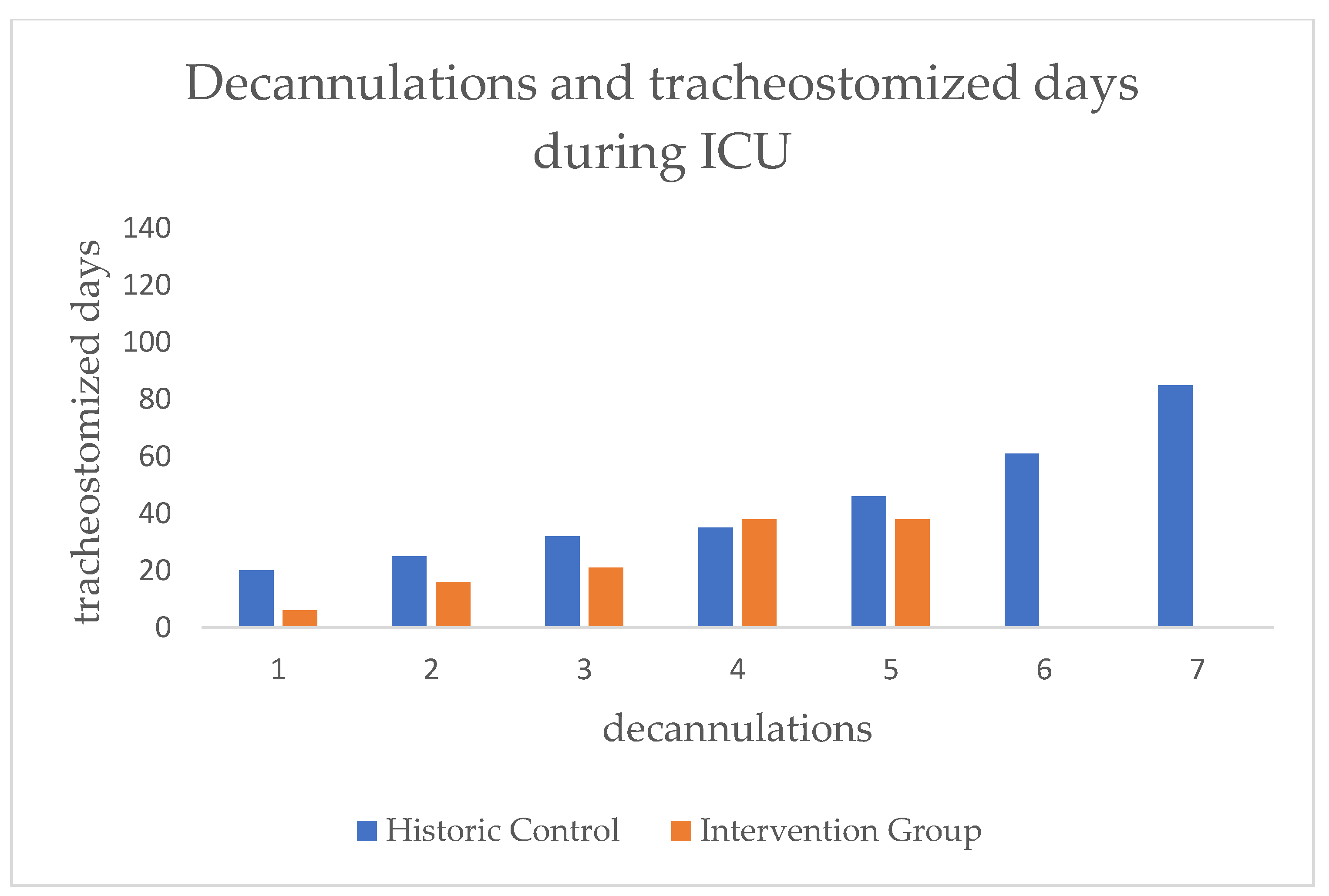

In order to look at the effect on SLT and decannulation alone, we analyzed the subgroup of patients that were decannulated during the ICU stay. We therefore used the date of the successful attempt. Regarding the frequency of decannulation, we found no significant difference between both groups. In the HC there were seven (12.96%) and in the IG there were five (8.62%) successfully decannulated (see

Figure 9/

Table 2).

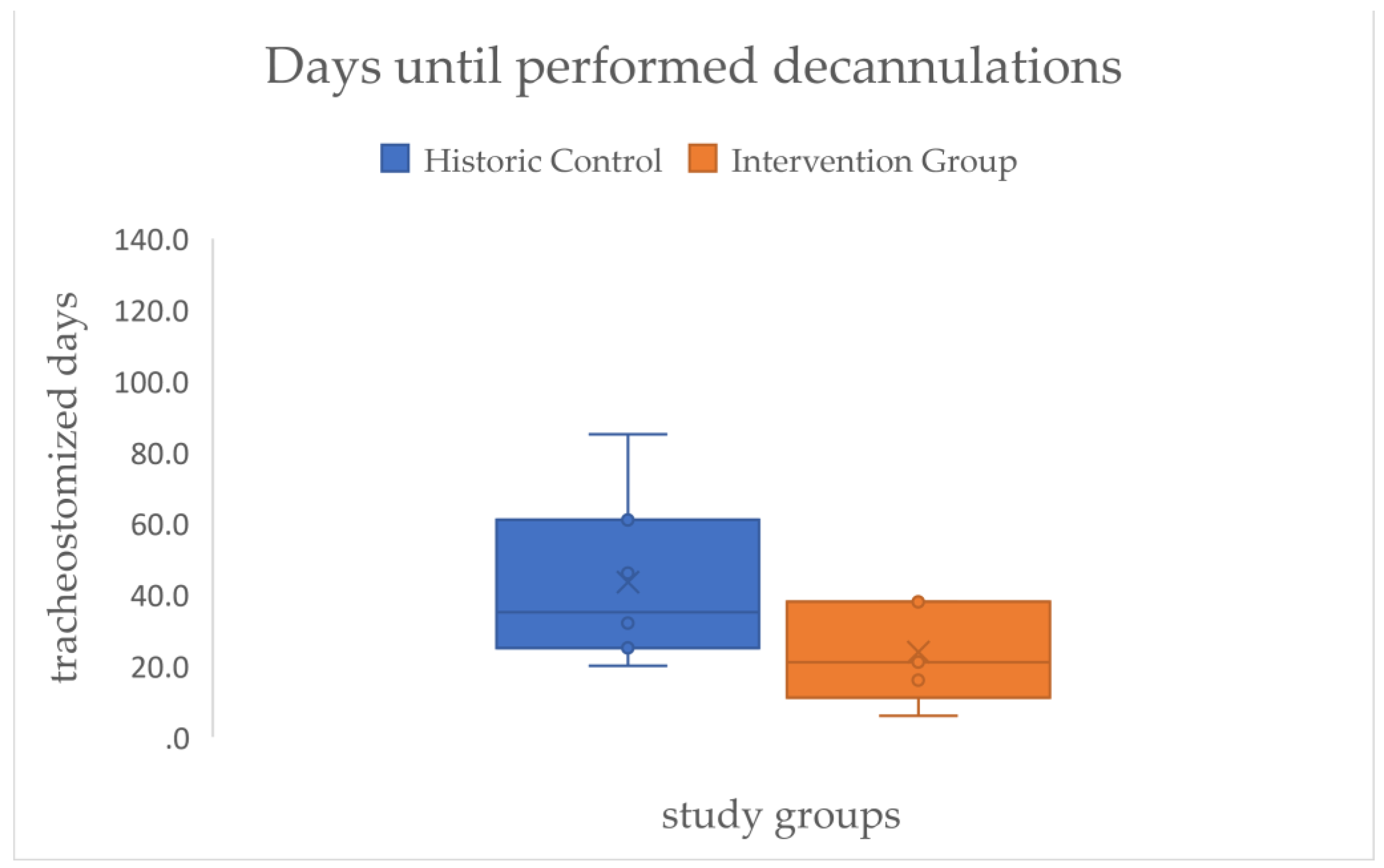

In the next step of the analysis we focused on the residence time of the cannulas of those that could be decannulated. A large effect size (d=.99) but no statistical significance could be demonstrated for the time difference in days with cannula between both groups (HC=43.43, IG=23.85) (see

Figure 10/

Table 2).

The final part of the analysis is related to SLT and its integration in the ICU setting and the qualitative impact on the project. The allocation of SLT to the dedicated patients was possible for about 65% in the IG, and this was significantly higher and more treatment (d=.739) than the only 9% of patients in the HC that received SLT during their ICU stay. This also impacted the diagnostic component of the patient care and led to significantly more clinical dysphagia examinations (CDA) as well as Flexible Endoscopic Evaluations of Swallowing. On the other hand, it did not lead to more patients that were fed by mouth (HC=11.11% vs. IG=13.79%) (see

Table 2).

Regarding the competence of self-care for their cannula (i.e. self suctioning) we unfortunately cannot report results since it was not possible to gather reliable information from the electronic patient documentation systems on this topic.

4. Discussion

After implementation of the IQ-ICU project we were able to demonstrate a mean reduction of days being tracheostomized on ICU by eight days and a reduction of LOS by twelve days for all patients. Coming down to those who could be decannulated during the ICU stay, clinically highly relevant results with a large effect size (d=.99) could be demonstrated by a mean reduction of the residence time of the tracheal cannula by 20 days. Due to the small sample of performed decannulations (HC n=7, IG n=5) this did not reach statistical significance.

The mean reduction of the residence time of the tracheal cannula is in line with a comparable pre-post study investigating the effect of a tracheostomy pathway [

12]. Also for the direct group comparison of those that could be decannulated on ICU and the found difference of 20 days there are similar effects described after the introduction of early rehabilitation concepts (30 days) [

23].

Our result, that the decannulation process can be fastened but that the amount of patients who can be decannulated remains stable has also been shown by others [

23]. Not more decannulations possible can mean that there might be some “iatrogenic” barrier for possible decannulations which cannot be “bypassed” by traditional means of tracheostomy management (compare 4.2 Ideas for future research).

As demonstrated by the regression model, which exhibited an explained variance of 77%, the days with cannula can be regarded as a robust predictor of length of stay (LOS). This is noteworthy despite the fact that it functions as a surrogate parameter for a variety of clinical conditions. Hence, it seems very likely that efforts to reduce the residence time of tracheal cannula will directly translate into reduced LOS on ICU. This perspective is distinctive in that research has either sought to predict decannulation success [

24,

25] or LOS [

26].

When focusing on feasibility of integrating SLT in the ICU setting, we were able to allocate SLT to 65% of dedicated patients in the IG. This resulted in significantly more treatment (d=.739) and also impacted the diagnostic component of the patient care with significantly more clinical dysphagia examinations (CDA) as well as Flexible Endoscopic Evaluations of Swallowing. Hence, we conclude that this is evidence for the practical applicability of respective guideline recommendations [

6,

7]. On the other hand, this did not lead to more patients that were fed by mouth (HC=11.11% vs. IG=13.79%), although this cannot be considered a primary goal for ICU and can always be addressed on subsequent normal wards.

4.1. Limitations

First of all, limitations arise from the pre-post study design. A randomized controlled trial would have been a more desirable study design, but it was not feasible to implement two different projects on the same ICU ward with the same staff simultaneously. Also the retrospective data analysis for the HC bears risks of bias. For instance, a strong source of bias would have been data from the Corona period. Consequently, the retrospective analysis was constrained to the post-Corona period, with sufficient temporal distance.

The fact that not more decannulation were possible in the IG than in the HC, as we expected before, could have been influenced by the differences in the tracheostomy types between the two groups. There were significantly more surgical tracheostomies in the IG (12) than in the HC contributing to more efforts for decannulation (e.g. the necessary surgical closure of the stoma) [

27]. A potential source of bias, contributing to a shorter LOS in the IG, hence a reverse effect to the one previously discussed, could be the mean difference in time of tracheostomy (first day with TC on ICU) of four days between both groups (HC=13.93 → IG =9.7). This is because there is relevant evidence that found early tracheostomy to result in fewer ICU days [

28]. However, given that both groups can be classified as "early tracheostomies" and that we identified both an inhibiting and a promoting potential bias within the same group (i.e., our IG), it is anticipated that these biases will offset each other.

4.2. Considerations and Ideas for Future Research

For a better understanding of the effect of SLT on the reduction of time until decannulation in the IG, we will perform a detailed case study of these patients as a next step.

In order to stay with state of the art research, we want to implement the Standardized Endoscopic Swallowing Evaluation for Tracheostomy Decannulation (SESETD) protocol [

29] in the IQ-ICU-SLT SOP.

As explained, due to uncertainty if ICU patients would meet the necessary etiologies for PES application (i.e. neurogenic dysphagia in Europe), we decided against PES at the first stage of the IQ-ICU project. Nevertheless, its proven usefulness to fasten the decannulation process [

13] makes it an interesting tool. Since across both of our groups the complication of apoplexy emerged in 15.18% with an associated high risk for neurogenic and post-extubation dysphagia [

30], we consider PES as a potential future means of PED prevention. Hence, PES could be integrated in the weaning from ventilation process during the early intubation phase in order to reduce PED and extubation failure/or necessary tracheostomies with the potential to further shorten the LOS on ICU. Therefore, includable etiologies (e.g. stroke, brain tumor, traumatic brain injury) or clinical symptoms indicating for neurogenic dysphagia (e.g. tolerance of endotracheal tubes, saliva pooling) that potentially would profit from PES application on general ICU wards have to be identified. By this, the PED could be reduced and this might result in either a lower necessity for tracheostomy at all or more decannulations that can already be performed on ICU and not later in course of rehabilitation.

The demonstrated feasibility to implement SLT in tracheostomy management of an ICU and the accompanying positive results of IQ-ICU-SLT should be acknowledged by professional societies and associations and lead to clear recommendations for the inclusion of SLT on ICU, as already demonstrated in one guideline [

7].

5. Conclusions

This project demonstrated that interprofessional teamwork of medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, SLT, and occupational therapy on a general ICU is feasible, will improve the quality of treatment, and reduce morbidity as well as the LOS on ICU. Integrating SLT and their expertise into intensive care will likely lead to benefits such as shorter time to decannulation and safer decannulation processes since necessary diagnostics like FEES can be performed more often and by specially trained staff. This also enhances patients' quality of life.

Surely, the shown positive effects on reduction of LOS cannot be solely attributed to the SLT input on treatment. However, the demonstrated reduction in days until possible and save decannulation can be considered an indicator for the effective integration of SLT in this process on general ICUs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., J.K., U.B., and H.M.; methodology, M.B., J.K., U.B., and H.M.; validation, M.B., I.N., J.K., L.M., U.B., and R.K.; formal analysis, J.K., M.B., R.K., L.M., and I.N.; investigation, I.N., L.M. and M.B.; resources, M.B. and U.B.; data curation, I.N., L.M., J.K. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, J.K., M.B., R.K., and U.B.; visualization, J.K.; supervision, M.B., U.B., H.M., and J.K.; project administration, M.B., J.K., U.B., and H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the responsible ethics committee of the State Chamber of Physicians of Rhineland-Palatinate (Nr.: 2024-17433), and is registered with the WHO register for Clinical Trials (DRKS00036084).

Informed Consent Statement

The approval of the ethics committee covers the data analysis for the historical control group and the intervention group as they were gathered as a part of the daily clinical routine. Hence, no individual patient consent was obtained. Publication of these anonymized data is accepted, especially when part of aggregated data.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to restrictions on the use of clinical patient data. Furthermore, a public accessibility is not covered by the given ethics vote. In this, data sharing is limited to inner institutional research partners.

Acknowledgments

Foremost, the authors would like to thank all of the anonymous patients. All clinical colleagues are acknowledged for their daily work in the clinical routine!

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Yu, W.; Dan, L.; Cai, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Incidence of post-extubation dysphagia among critical care patients undergoing orotracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Medical Research 2024, 29, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, M.; Battaglini, D.; Antonelli, M.; Corso, R.; Frova, G.; Merli, G.; Petrini, F.; Ranieri, M.V.; Sorbello, M.; Di Giacinto, I.; et al. Follow-up short and long-term mortalities of tracheostomized critically ill patients in an Italian multi-center observational study. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderone, A.; Filoni, S.; De Luca, R.; Corallo, F.; Calapai, R.; Mirabile, A.; Caminiti, F.; Conti-Nibali, V.; Quartarone, A.; Calabrò, R.S.; et al. Predictive Factors of Successful Decannulation in Tracheostomy Patients: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2025, 14, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Saran, S.; Baronia, A.K. The practice of tracheostomy decannulation—a systematic review. Journal of Intensive Care 2017, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin e. V. (DGAI). Lagerungstherapie und Mobilisation von kritisch Erkrankten auf Intensivstationen (2024). Available online: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/001-015 (accessed on 24.09.2025).

- Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin (DIVI). Empfehlung zur Struktur und Ausstattung von Intensivstationen 2022 (Erwachsene). Available online: https://www.divi.de/publikationen/intensivstationen (accessed on 15.10.2025).

- The Short-life Standards and Guidelines Working Party of the UK National Tracheostomy Safety Project. Guidance For: Tracheostomy Care (2023). Available online: https://www.ficm.ac.uk/sites/ficm/files/documents/2021-11/2020-08%20Tracheostomy_care_guidance_Final.pdf (accessed on 03.10.2025).

- Rivelsrud, M.C.; Hartelius, L.; Speyer, R.; Løvstad, M. Qualifications, professional roles and service practices of nurses, occupational therapists and speech-language pathologists in the management of adults with oropharyngeal dysphagia: a Nordic survey. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol 2024, 49, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton-Frost, N.; Brodsky, M.B. Speech-language pathology approaches to neurorehabilitation in acute care during COVID-19: Capitalizing on neuroplasticity. PM & R: the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation 2022, 14, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burek, A.; Büßelberg, N.; Stanschus, S. Qualitätssicherungs-Projekt zur Prävention von Aspirationspneumonien in der Akutversorgung von Schlaganfallpatienten mit Dysphagie. Forum Logopädie 2008, 22, 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Martino, R.; Foley, N.; Bhogal, S.; Diamant, N.; Speechley, M.; Teasell, R. Dysphagia after stroke: incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke 2005, 36, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.A.; Matthews, T.W.; Dubé, M.; Spence, G.; Dort, J.C. Changing practice and improving care using a low-risk tracheotomy clinical pathway. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014, 140, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewas, R.; Stellato, R.; van der Tweel, I.; Walther, E.; Werner, C.J.; Braun, T.; Citerio, G.; Jandl, M.; Friedrichs, M.; Notzel, K.; et al. Pharyngeal electrical stimulation for early decannulation in tracheotomised patients with neurogenic dysphagia after stroke (PHAST-TRAC): a prospective, single-blinded, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2018, 17, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledl, C.; Frank, U.; Dziewas, R.; Arnold, B.; Bähre, N.; Betz, C.S.; Braune, S.; Deitmer, T.; Diesener, P.; Fischer, A.S.; et al. Curriculum „Trachealkanülenmanagement in der Dysphagietherapie“. Der Nervenarzt 2024, 95, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewas, R.; Glahn, J.; Helfer, C.; Ickenstein, G.; Keller, J.; Lapa, S.; Ledl, C.; Lindner-Pfleghar, B.; Nabavi, D.; Prosiegel, M.; et al. FEES für neurogene Dysphagien. Der Nervenarzt 2014, 85, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, L. Screening swallowing function of patients with acute stroke. Part two: Detailed evaluation of the tool used by nurses. Journal of clinical nursing 2001, 10, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likar, R.; Aroyo, I.; Bangert, K.; Degen, B.; Dziewas, R.; Galvan, O.; Grundschober, M.T.; Köstenberger, M.; Muhle, P.; Schefold, J.C.; et al. Management of swallowing disorders in ICU patients - A multinational expert opinion. Journal of Critical Care 2024, 79, 154447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L.; Moreno, R.; Takala, J.; Willatts, S.; De Mendonça, A.; Bruining, H.; Reinhart, C.K.; Suter, P.M.; Thijs, L.G. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996, 22, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Gall, J.R.; Lemeshow, S.; Saulnier, F. A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. Jama 1993, 270, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; Mitnitski, A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönle, P.W. The Early Rehabilitation Barthel Index--an early rehabilitation-oriented extension of the Barthel Index. Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 1995, 34, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zivi, I.; Valsecchi, R.; Maestri, R.; Maffia, S.; Zarucchi, A.; Molatore, K.; Vellati, E.; Saltuari, L.; Frazzitta, G. Early Rehabilitation Reduces Time to Decannulation in Patients With Severe Acquired Brain Injury: A Retrospective Study. Front Neurol 2018, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaga, C.J.; Milliren, C.E.; McGrath, B.A.; Yang, C.J.; Schiff, B.A.; Warrillow, S.J.; Henningfeld, J.K.; Gregson, P.A.; Bedwell, J.R.; Beaudet, K.M.; et al. Predictors of Decannulation Success in Tracheostomy: A 10-Year Analysis of the Global Tracheostomy Collaborative Database. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery n/a. [CrossRef]

- Añón, J.M. Can we predict the duration of the decannulation process? Medicina Intensiva (English Edition) 2012, 36, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, A.; Schober, P.; Venetz, P.; Andereggen, L.; Bello, C.; Filipovic, M.G.; Luedi, M.M.; Huber, M. Predicting admission to and length of stay in intensive care units after general anesthesia: Time-dependent role of pre- and intraoperative data for clinical decision-making. Journal of clinical anesthesia 2025, 103, 111810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, A.; Swami, G.; Kumar, K.D. Comparative Study of Percutaneous Dilatational Tracheostomy and Conventional Surgical Tracheostomy in Critically Ill Adult Patients. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2023, 75, 1568–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorath, K.; Hoang, A.; Rajasekaran, K.; Moreira, A. Association of Early vs Late Tracheostomy Placement With Pneumonia and Ventilator Days in Critically Ill Patients: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2021, 147, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewas, R.; Warnecke, T.; Labeit, B.; Schulte, V.; Claus, I.; Muhle, P.; Brake, A.; Hollah, L.; Jung, A.; von Itter, J.; et al. Decannulation ahead: a comprehensive diagnostic and therapeutic framework for tracheotomized neurological patients. Neurological Research and Practice 2025, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertschi, D.; Rotondo, F.; Waskowski, J.; Venetz, P.; Pfortmueller, C.A.; Schefold, J.C. Post-extubation dysphagia in the ICU−a narrative review: epidemiology, mechanisms and clinical management (Update 2025). Critical Care 2025, 29, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).