1. Introduction

The city of San Cristóbal de la Laguna dates back to 1496 when the troops of the Catholic Monarchs, led by D. Alonso Fernández de Lugo, defeated the indigenous people of the island of Tenerife, known as the Guanches, and founded this first strategic city. Initially, the city was established on the upper part of the island next to the old lagoon (which gave the city its name) called “Villa de Arriba”, whose settlement was irregular and without specific planning. A few years later, in 1500, Fernández de Lugo, now with the title of Adelantado, returned to the island and founded the definitive city called “Villa de Abajo” approximately 1 km to the southeast, with an orderly layout, from which the city’s grid pattern would originate [

1].

This foundation played an important ecclesiastical role, and it should be remembered that on 13 December 1486, the Catholic Monarchs had obtained from Pope Innocent VIII the papal bull Ortodoxae fidei, which granted them Royal Patronage over the churches of the Canary Islands, the Kingdom of Granada and the town of Puerto Real [

2], allowing them to build and financially support churches, cathedrals, convents and hospitals. La Laguna was the head of one of the two initial benefices (or churches) on the island and served as the residence of the island’s vicars, which led it to become the ecclesiastical capital of the island of Tenerife [

3]. The role of the Cabildo, led by the Adelantado, would be very important in the organisation of the parish and in helping to found hermitages, churches and convents, with the aim of achieving the highest ecclesiastical rank for the city [

4]. In this way, La Laguna would become the first capital of the Canary Islands and an administrative, religious and cultural centre.

But what was truly novel about this city was that it responded to a new peaceful social order or “City of Peace” inspired by the religious doctrine of the millennium and its expression through urban design, being the first example of an unfortified city or grid-shaped city-territory, which would later be replicated in the expansion throughout America [

5]. This archetype used its own natural borders to delimit itself, employing a grid system with a precise geometric map that, 500 years later, led to its declaration as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO [

6].

In this work, we will analyse the chronology of the ecclesiastical foundations of La Laguna and, in particular, the urban axes or structures that these buildings generated in the evolution and growth of the city as the main articulators of blocks and streets, playing an essential role in the urban footprint.

We will use a graphical analysis methodology through sequential maps, where we will locate each foundation in stages, analysing the veracity of the impact that these buildings had on the urban design of the city. We will then compare them with the first foundations in America, Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, the first city founded by the Spanish in 1502, and Panama Viejo, the first non-insular foundation in 1519, which gives this study a distinct added value by providing new knowledge on the subject.

The selected objects of study also have in common the fact that they are historic centres inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (Santo Domingo in 1990 and La Laguna in 1999), with Panama Viejo on the tentative list since 2015 for possessing exceptional universal values of early colonial urbanism, which have endured to this day, thanks in part to the convent establishments, an architectural typology that has had an impact on the urban footprint of these enclaves. The conclusions of our study will therefore provide new insights into the role of convents as key urban elements in the articulation of colonial cities, and in particular, how the case of La Laguna served as a testing ground and bridge between Spain and America, providing a direct relationship in time and space with the role of religious orders in these cities and determining their unique value in the current urban fabric. A resilient typology of maximum heritage value, which in the past played a fundamental role in the emergence and expansion of these historic sites and which contributes heritage values linked to the present and future of the three cities analysed.

2. Colonial Model of City-Territory

Firstly, we will analyse the urban model that emerged in La Laguna, as a basis for studying this city. We find ourselves at the end of the 15th century, when the Catholic Monarchs were completing the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula and founding the last cities that would serve as the closest model to replicate in the New World. We highlight the cities of Puerto Real (Cádiz) and Santa Fe (Granada) in Lower Andalusia on the Iberian Peninsula, and San Cristóbal de La Laguna (Tenerife) in the Canary Islands, which is the case study for this work. These cities served as precedents and references for the design of colonial cities due to their rational planning, orthogonal layout, and strategic function. Below, we analyse the origin and contribution of each to the colonial urban model, and classify them into two types:

2.1. Fortified Cities

Cities founded by the Catholic Monarchs during the Reconquista. In the case of Puerto Real, it was an urban project planned to have its own royal port in the Bay of Cádiz, a strategic area for trade and defence. In the case of Santa Fe, it was established during the siege of Granada, created as a military camp that quickly evolved into a permanent city. Their purpose was to serve as a base for the conquest of the last Muslim stronghold on the Peninsula. Here we highlight two examples:

Puerto Real (Cadiz, founded in 1483): Its design reflected an orthogonal layout (grid streets) with a central square where the church is located, a model inspired by medieval bastides and Roman camps (castrum) whose town charter authorised “towered gates” [

7]. This layout facilitated social and administrative organisation. Puerto Real served as a prototype for urban planning in port cities in America, where commercial and defensive functions were key.

Santa Fe (Granada, founded in 1491): Santa Fe had a grid layout with straight streets and a central main square surrounded by administrative and religious buildings. Its design reflected the influence of Renaissance ideals of order and symmetry, as well as the need for territorial control. Santa Fe is considered a direct model for colonial cities in America. Its rapid foundation and functional structure were replicated in the colonies, where cities had to be founded quickly to establish the Spanish presence.

2.2. Unfortified Cities or City-Territories

This is an example that served as a trial run for the grid-based urban model, but without the need for fortification, instead adapting to the existing terrain and designed and built according to a pre-existing map. Here we have the example of San Cristóbal de La Laguna (Tenerife, founded in 1496, consolidated in 1525). Founded by Alonso Fernández de Lugo after the conquest of the Canary Islands, La Laguna was one of the first grid cities outside the Iberian Peninsula. The Canary Islands served as a “laboratory” for colonial practices that were later applied in America. La Laguna adopted a grid layout with a central square, churches and administrative buildings, adapting to the mountainous terrain. Its urban planning combined practical elements with Renaissance ideals of order and beauty. As an early colonial city, La Laguna was a model for American cities, especially because of its adaptation to a non-peninsular environment. Its space is organised according to a new peaceful social order inspired by the religious doctrine of the millennium that arose in the year 1500.

The Spanish colonial urban model was fundamentally developed from the experiences of Puerto Real, Santa Fe and La Laguna, which combined medieval tradition, Renaissance ideals and the strategic needs of the monarchy. The three cities shared a grid design, with straight streets converging on a main square, which facilitated social, administrative and religious organisation. The experiences of Puerto Real, Santa Fe and La Laguna were codified in the Laws of the Indies of 1573, which standardised colonial urban design with an emphasis on the grid, the central square and spatial hierarchy. Each city responded to specific needs (defence, trade, conquest), which was transferred to the colonies, where cities were tools of territorial control. However, there is one issue that sets them apart, and that is the role of religious foundations in shaping the urban fabric, as in the case of La Laguna, which we will use as a case study to compare with the first foundations in America in the early 16th century.

3. The convents in San Cristóbal de la Laguna as Articulating Pieces of the Urban Fabric

As explained above, La Laguna is the first example of an unfortified city following an irregular grid design adapted to the terrain, a feature that would be replicated in the first foundations in America. Its straight streets and well-defined blocks reflect the ideals of order and symmetry of the time, and we will analyse how the convent foundations impacted this urban design.

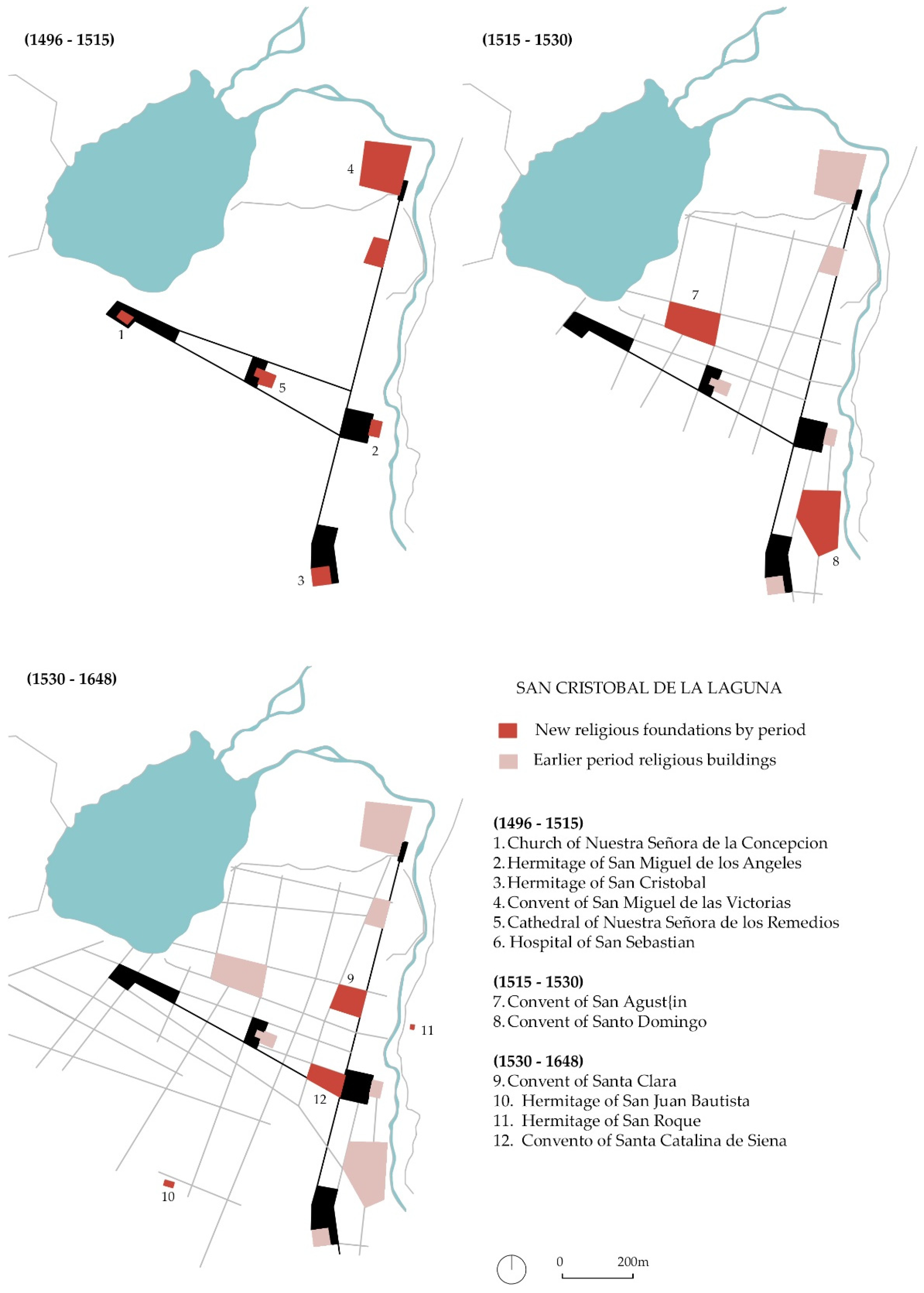

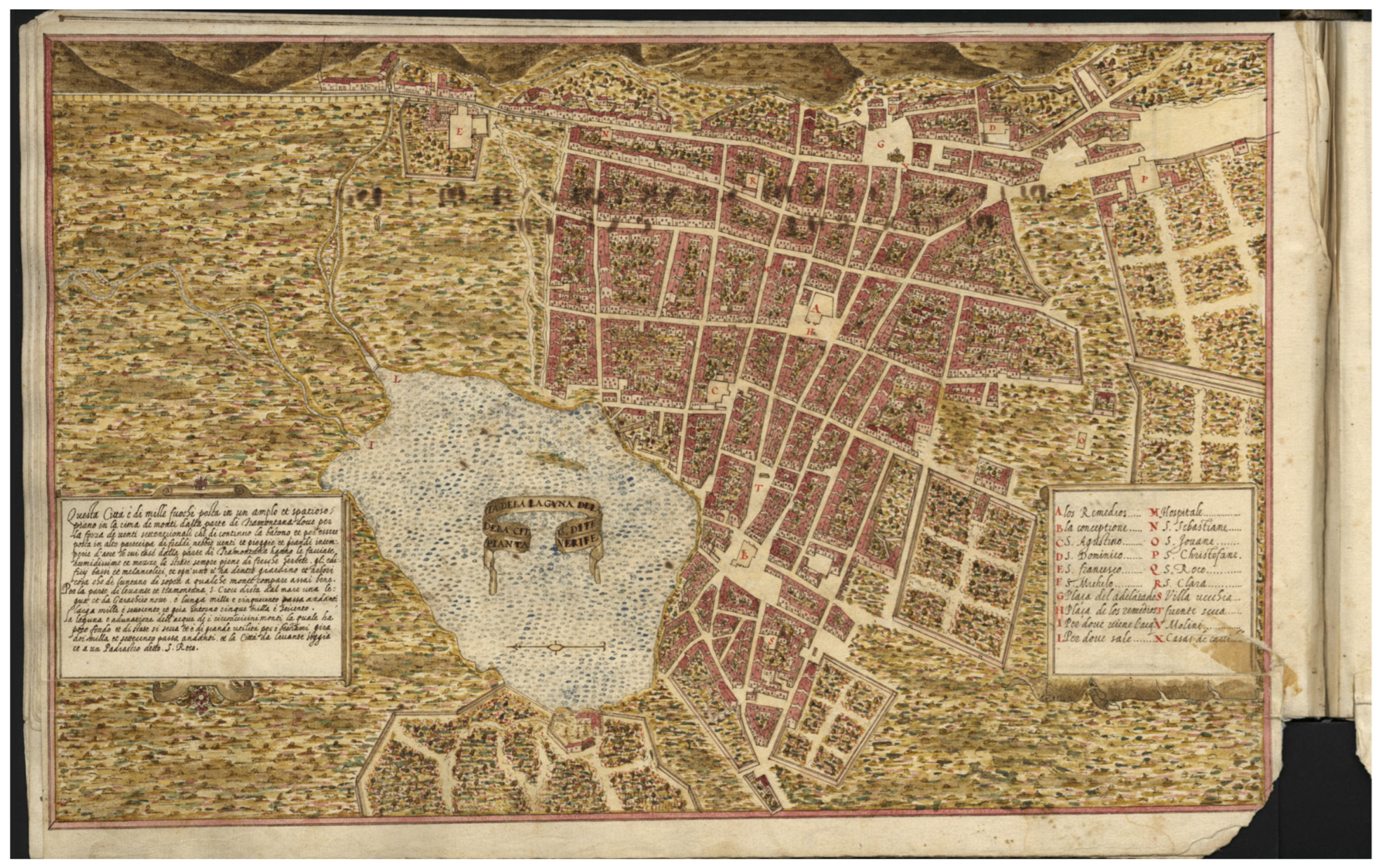

According to Leonardo Torriani’s 1588 map (see

Figure 1), the first detailed map of La Laguna, more than half of the legend corresponds to ecclesiastical buildings, showing four convents (Franciscan, Dominican, Augustinian and Poor Clare), the two main churches (Concepción and Remedios), two hospitals and several hermitages. Preserved in historical archives, this map is fundamental to reconstructing the urban and religious layout of the city’s foundation. We will analyse these foundations chronologically and how the city was shaped through these urban articulators.

3.1. East-West Religious Axis Between Villas de Arriba and Villa de Abajo

Firstly, we will highlight the first foundations of religious buildings that gave rise to the urban centre, forming a main axis around which the city is organised, linking Villas de Arriba and Villas de Abajo.

3.1.1. Church of Nuestra Señora de la Concepción (1496, rebuilt in 1511)

Founded by Alonso Fernández de Lugo after the Corpus Christi festival in 1496 [

4], it is the mother parish of Tenerife, from which all the other parishes on the island were derived. Initially a small hermitage in the Upper Town, where the Council met in the early years of the city [

3], it was rebuilt in 1511 with a three-nave design in the Mudejar style, designed by the architect. It was declared a Historic-Artistic Monument in 1948 and served as a temporary cathedral between 2002 and 2014.

3.1.2. Hermitage of San Miguel de los Ángeles (1506)

Founded on 14 May 1506 by Fernandez de Lugo, it was named after the archangel Saint Michael due to the Adelantado’s particular devotion to him. It was the seat of the island’s council until 1526, on those occasions when there was no other place to hold it. This first building, located in the Plaza del Adelantado, was built by the architect Pedro de Llerena, who came from Seville to work in the archipelago. In 1574, work was carried out on the hermitage and its modest bell tower was built in 1578 [

8]. It is currently occupied by the Convent of Santa Catalina de Siena.

3.1.3. Cathedral of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios (1511, enlarged in 1515)

The second parish in La Laguna was founded in 1515, in a location roughly equidistant between the main square and the Church of La Concepción in Villa de Arriba. In this case, the location was specifically chosen by Fernández de Lugo, reinforcing the religious character of the area [

4]. With the extension in 1515, it became a parish church dedicated to Our Lady of Los Remedios, patron saint of the city, the island and the diocese. Today it is active as a cathedral, Marian shrine and parish church. It was declared a Historic-Artistic Monument in 1983.

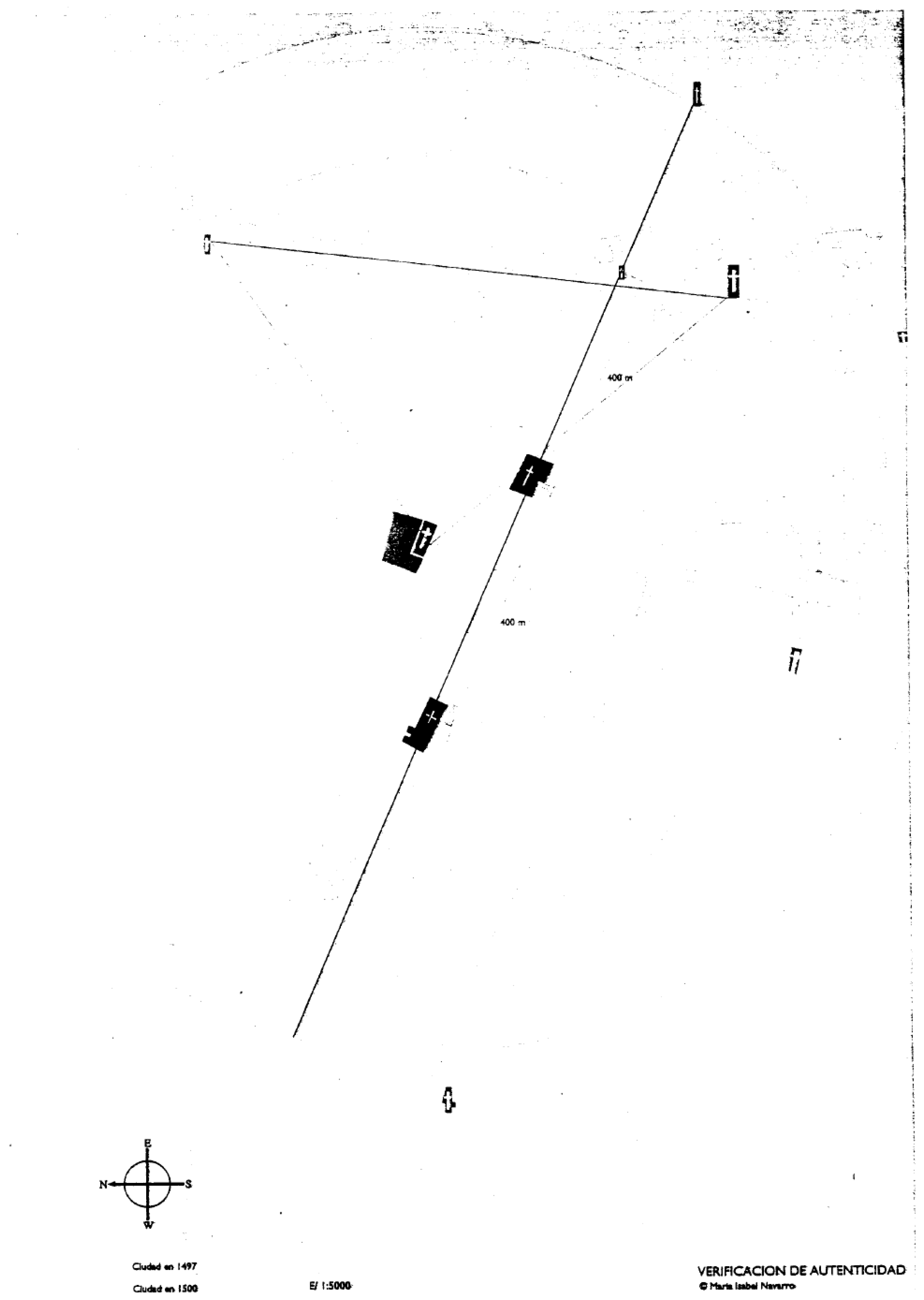

As mentioned above, these three religious buildings linked the first two centres with a marked religious character, precisely planned by the Adelantado; from La Concepción to Los Remedios there are 800 steps, and from Los Remedios to San Miguel, another 800 steps, as recounted in the document. This can be seen in

Figure 2 prepared by María Isabel Navarro in the UNESCO declaration [

6].

3.2. North-South Axis Between Franciscans and Dominicans

In addition to the east-west axis, there is a north-south axis (as can be seen in

Figure 2), at the intersection of which is the Plaza del Adelantado, which links the Franciscan and Dominican convents, creating another axis of growth for the city and completing the grid pattern.

3.2.1. Convent of San Miguel de las Victorias, now San Francisco (1506-1508)

It is said that this convent was founded immediately after the conquest of Tenerife by five Franciscan monks. Its first location was on the hill known as Bronco. There they had a hut covered with palm leaves where they celebrated mass. When Don Alonso de Lugo saw them, he gave them new land, on which he himself laid the first stone of the building in 1506 [

8]. By 1508, the convent house had been completed, and it would be expanded in subsequent decades until the end of the century [

4].

3.2.2. Convent of Santo Domingo (1527-1533)

Founded by Dominican monks in 1527, who had been living in the hermitage of San Miguel de las Victorias since 1522 [

8], this convent was a key educational and religious centre in La Laguna. Originally, it was to be located closer to the Plaza del Adelantado, the usual site for Dominicans closer to the centre of power, but it was eventually located further south, near the road to Santa Cruz. Arriving later than the Franciscans and Augustinians, they had to win the affection of the community [

4]. This convent, located on the north-south axis of the city, marked the urban development of the area. In the 19th century, after the confiscation, it became a diocesan seminary. The building, documented in Torriani’s map (1588), preserves a Renaissance cloister and remains of mural paintings. It was declared a Site of Cultural Interest in 1983.

3.2.3. Hermitage of San Cristóbal (1506-1525)

We can also include in this north-south route the Hermitage of San Cristóbal, one of the first ecclesiastical buildings (around 1506) south of Villa de Abajo, in an eccentric location surrounded by farmland [

3], although it is relevant to our route as it is located on the southern outskirts of the city on the road to the cross. It was not completed until approximately 1525 [

4].

3.2.4. Hospitals of Santa María de la Antigua Misericordia (1507) and San Sebastián (1512)

There are also references to two hospitals in this period, which we mention because of their religious nature and connection. In 1507, the Hospital of Santa María de la Antigua Misericordia was located on what is now Calle San Agustín (a secondary east-west axis) connecting with the Augustinian convent, and another was the Hospital of Sebastián, with Franciscan links, built in 1512 near the convent, where there is now a nursing home [

6].

This axis, of great religious significance, remains reinforced today, as all these buildings are still standing.

3.3. San Agustín as a Geometric Centre

3.3.1. Convent of San Agustín or Espíritu Santo (1505-1530)

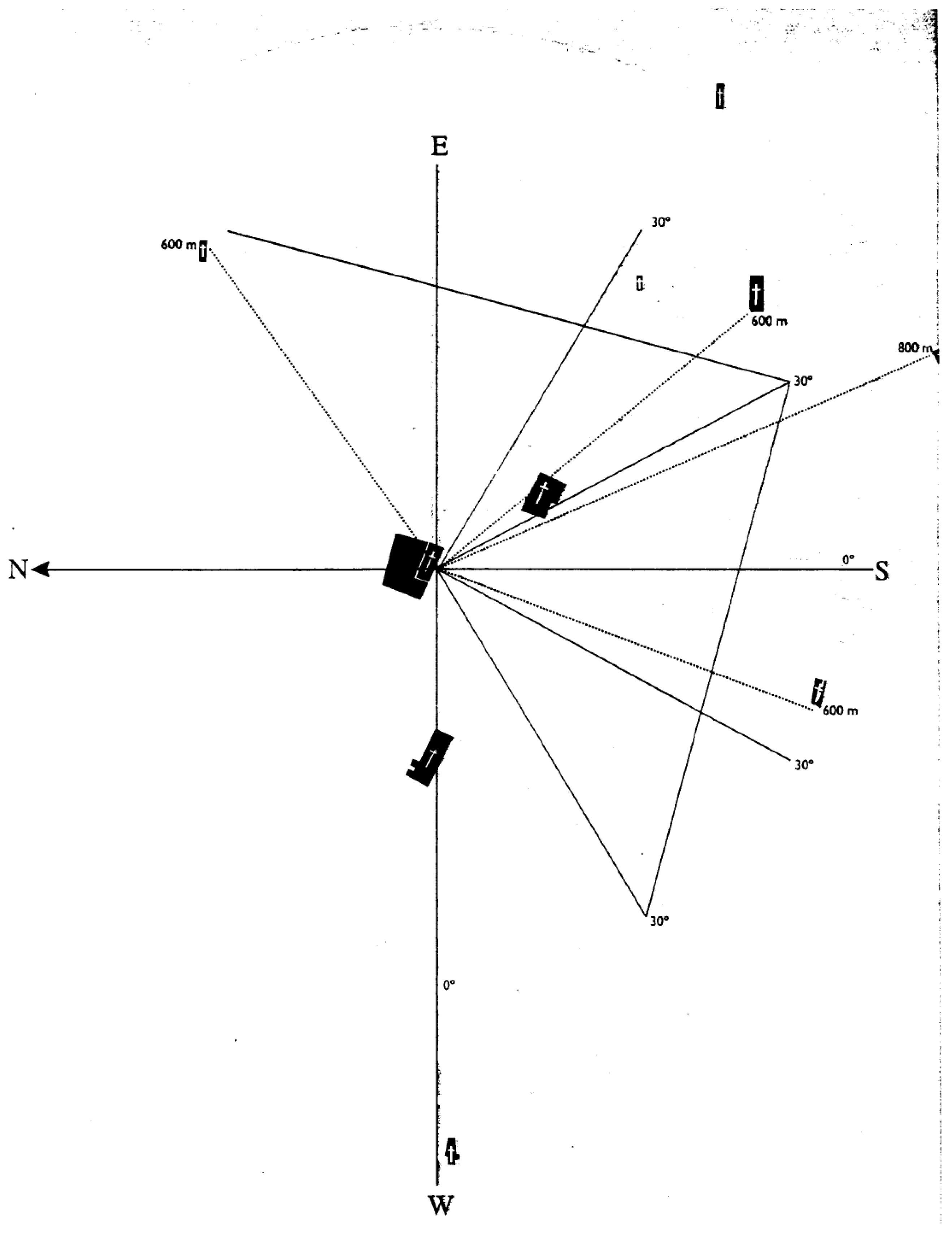

This convent was founded by the Augustinian monks Fray Pedro de Cea and Frat Andrés de Goles on land donated by the governor, initially intended for a hospital, near the Church of La Concepción [

6]. Work began in 1505, but most of the convent was built after 1530 [

4]. Its Renaissance cloister is one of the finest in the Canary Islands, with red stone columns and wooden footings. In 1964, a fire damaged the church, which remains in ruins, but the convent was restored between 1993 and 1997. It houses the remains of the historian Juan Núñez de la Peña and was declared a Site of Cultural Interest in 1983.

The Convent of San Agustín, in addition to being on another secondary E-W axis, would have had a very important position in the planning of the city since its origin, as it was established as a theoretical centre from which measurements of 1,200 steps would be taken radially to establish the perimeter of the city, delimiting the location of the rest of the religious foundations and hermitages and streets, forming a triangle between the Franciscans, Augustinians and Dominicans.

Figure 3.

Geometric relationship between the convent positions with Saint Augustine at the centre [

6] .

Figure 3.

Geometric relationship between the convent positions with Saint Augustine at the centre [

6] .

3.4. North-South Female Axis Between the Poor Clares and the Dominicans

Until 1531, when the city was granted its charter [

3], the main period of formation of the urban fabric of the city coincided with the period of foundation of the male convents and main religious buildings in the city. However, it is important to highlight the arrival of female convents in the city, as their location reinforced these urban structures, positioning themselves on the north-south axis marked between the Franciscan and Dominican convents, but closer to the centre and the powerful families, who were most interested in the emergence of this type of building.

3.4.1. Convent of Santa Clara (1547)

Since the 1920s, the Cabildo, acting on behalf of the most powerful neighbourhood, had wanted the island to have a female convent. The male orders were approached, first the Dominicans and then the Augustinians, but it was the Franciscans with whom an agreement was reached in 1540 to establish a convent for the Poor Clares, which would be founded in 1547 [

4]. This cloistered convent is one of the oldest in La Laguna. Its church and outbuildings reflect Canarian colonial architecture, with Mudejar elements. It remains a centre of religious life and is open to the public for limited visits.

3.4.2. Convent of Santa Catalina de Siena (1611)

The second female foundation in the capital had to wait many years from the emergence of the idea (between 1520 and 1530) to its completion (in the 17th century). In 1611, there were only four nuns from Seville, and by 1676, it housed 100 nuns [

4]. This cloistered convent is one of the most emblematic in La Laguna. Its Baroque church houses valuable works of art and relics.

Today, these two convents are the only ones that remain active and in excellent condition, providing a great example of resilience in convent use in the city.

3.5. Other Eccentric Religious Buildings

Although they do not have any particular urban relevance in the areas mentioned above, it is important to mention the rest of the religious buildings in La Laguna, which are important in the historical ecclesiastical context.

3.5.1. 16th-Century Hermitages: Nuestra Señora de Gracia, San Benito, San Juan Bautista, San Lázaro, and San Roque

Although they do not occupy relevant locations in the urban layout, being far from the main urban grid, these religious buildings have managed to survive to the present day since the city’s founding.

The Hermitage of Gracia was one of the first, along with the aforementioned San Miguel and San Cristóbal, from the period between the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century, commemorating the battles against the Guanches, although it was rebuilt in 1530. Then came San Lázaro, from the first decade of the 16th century, then rebuilt in 1530-1535 in its current location, San Benito (1532-1554), San Juan Bautista (1582-1584) and San Roque (circa 1600), the latter on the hillside near the Plaza del Adelantado [

4,

8].

3.4.3. Convent of San Diego del Monte (1648)

Founded by the Franciscan Recollects, located outside the city walls. It is known for the story of Fray Juan de Jesús, who claimed to have seen the Virgin of Los Remedios blessing La Laguna from the cathedral tower. The convent played an important spiritual role in the city.

3.5. Summary of Ecclesiastical Foundations and Urban Chronology

Although not all foundations have exact dates of foundation, we have compiled the dates of emergence of all these buildings in

Table 1, in order to then establish stages of development and show them on a map.

We will establish three stages of study:

1496-1515 -> Early origins of the Upper and Lower Towns, still as separate centres. Arrival of mendicant orders and first convent foundations

1515-1530-> Union of both centres, establishing connection axes established and related by the convent foundations (E-W and N-S).

1530-mid-17th century -> Origin of female conventuality and consolidation of the city.

Figure 4.

Urban morphological evolution based on the periods of foundation of religious buildings. Source: Author’s own work.

Figure 4.

Urban morphological evolution based on the periods of foundation of religious buildings. Source: Author’s own work.

4. Discussion

There are studies on how the Spanish city was conceptually transferred to the colonies in America [

9], passing through models from the medieval to the Renaissance city, where the urban grid structure of the late 15th century, with the examples cited of Puerto Real and Santa Fe de Granada in Lower Andalusia, became the model to be exported.

The founding of Santo Domingo in La Española (now the Dominican Republic) in 1502 was the first in the entire colonial process, which is why it lends itself particularly well to comparative study. Recent studies compare it with Oaxaca (Mexico), which has a similar colonial history (also declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO), highlighting how urban planning, religious architecture and spatial governance historically functioned as instruments of control [

10]. Or the authors’ own study prior to this research, which compares it with Panama Viejo, highlighting the role of the territory and the geographical conditions of the environment in establishing the city, as well as the role of mendicant orders in the urban structure [

11].

However, the role of La Laguna as an intermediate point between the Peninsula and America is what sets this research apart, providing a preliminary essay of relevance to the study of early colonial urbanism in America, which has not been addressed to date in this chronology. It is therefore of interest to compare La Laguna with the first settlements in the Americas, such as Santo Domingo, the first island settlement, and Panama Viejo, the first on the mainland, contextualising this process in the early 16th century.

4.1. Religious Axes Articulating the Grid

As we have seen in San Cristóbal de la Laguna (1496), the city emerged around an east-west axis that linked the Villas de Abajo and Villas de Arriba through its religious buildings (La Concepción, Los Remedios and San Miguel), limited by the existing geographical features (the lagoon to the west and the mountains to the east). Similarly, the northern and southern boundaries are marked by hermitages and convents, such as the Franciscan convent to the north, established on the outskirts as instruments of urban control. This cardus-decumanus is materialised by the Plaza Mayor at its intersection, following the classical model, and where power and the upper classes are established. The design of this unfortified city is therefore adapted to a grid pattern adapted to the existing terrain.

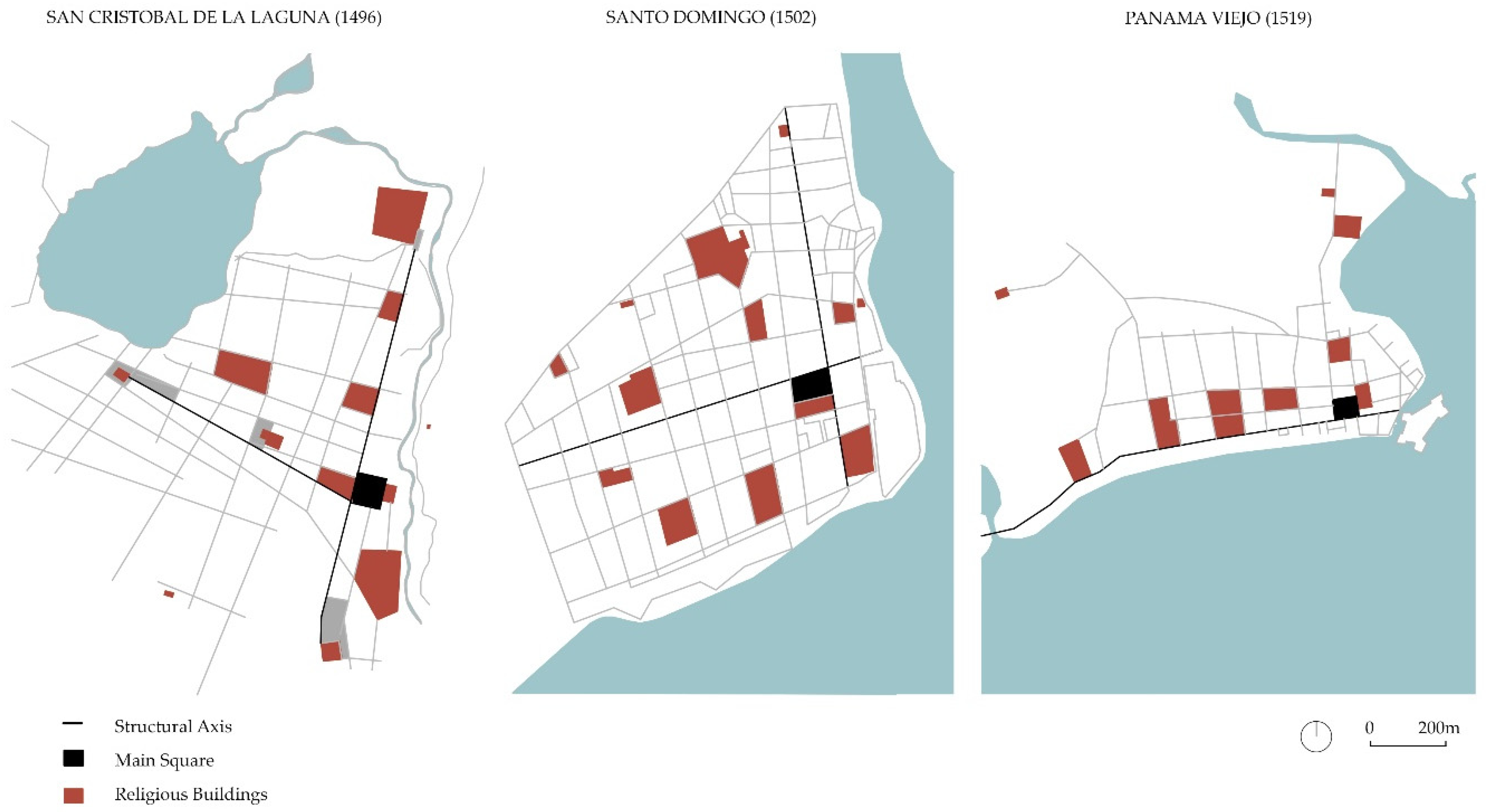

In

Figure 5, you can see how this urban feature also corresponds to the two American cities of Santo Domingo (1502) and Panama Viejo (1519). These two cities established their grid in an “L” shape parallel to the sea, adapting to the existing terrain. They placed their Plaza Mayor and Cabildo in a central position, and from that point, the same E-W and N-S axes where all the religious buildings were built, which marked the size of the city blocks.

4.2. The Role of Mendicant Orders

It has been shown how mendicant orders and their foundations in La Laguna played a fundamental role in shaping the urban fabric and its evolution. The presence of friars in La Laguna is as old as its foundation, given that both Franciscans and Augustinians accompanied the conquistadors [

3].

These orders and their members participated actively in urban society, attached to the city and in direct contact with the faithful through their preaching, which required intellectual preparation, a rich inner life and eloquence [

9].

Table 2 shows the arrival of the mendicant orders in the cities studied in chronological order.

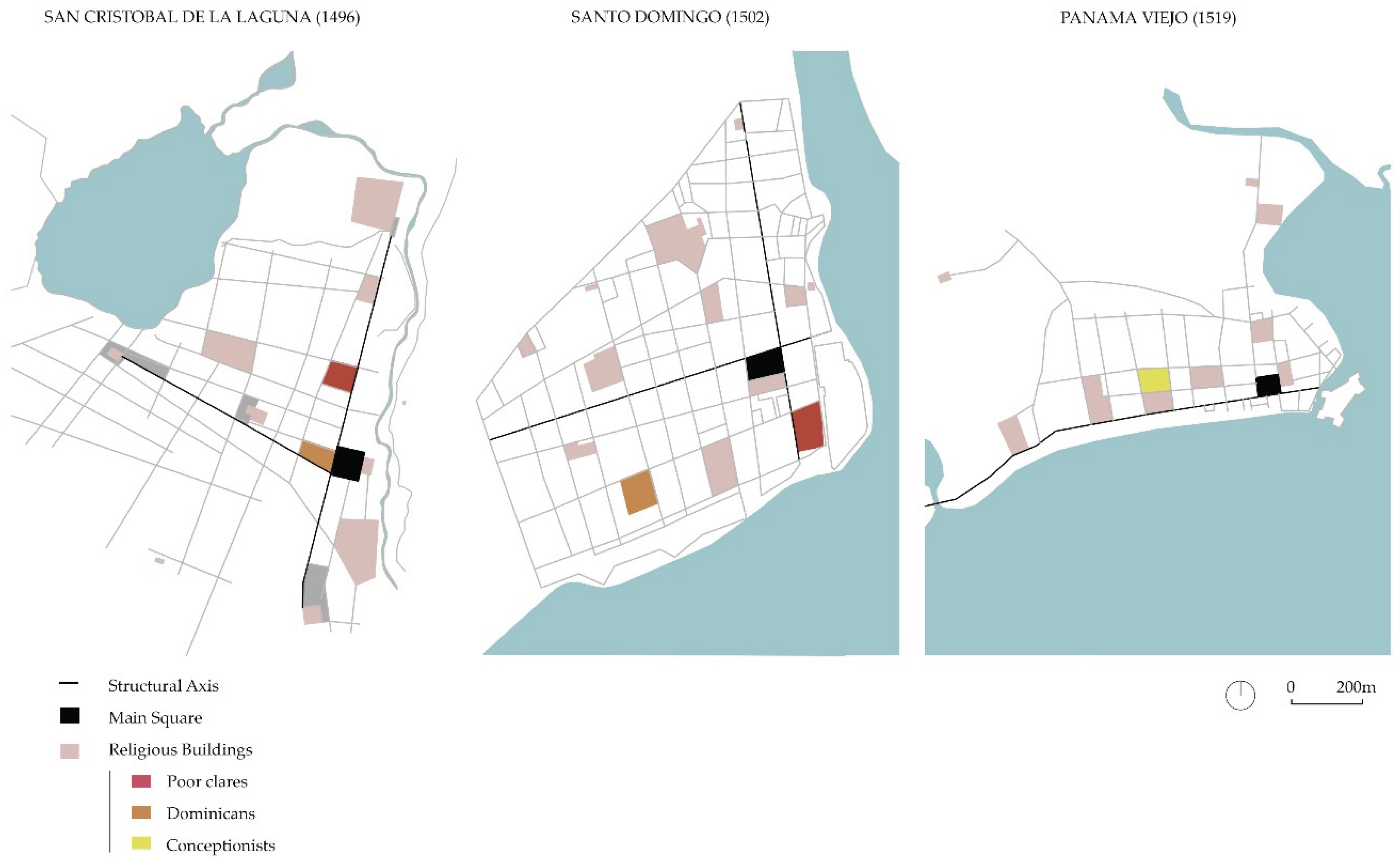

We can see that Franciscans and Dominicans were the only two orders that were established in all the cities studied, which is why we highlight their role in the articulation of these cities, with clearly differentiated roles:

Franciscans: They arrived together with the founders of each city. They were located on the outskirts, where the link with the indigenous people for evangelisation was greater. Their large orchards and connection with the rural environment served as a border t and control point for the territory. They were often associated with nearby hospitals, as their doctrine was related to healing and caring for the most disadvantaged.

Dominicans: They tended to arrive somewhat later, although their role in high society was much greater, as they usually had close relationships with powerful families. In the case of La Laguna, the Dominicans were related to the Lugo family of the founder. They were located near the Plaza Mayor, for greater influence in the governmental tasks of the cities.

Figure 6.

Identification of the male Franciscan and Dominican convents in the three case study cities. Source: Author’s own work based on the previous study between Santo Domingo and Panama [

11].

Figure 6.

Identification of the male Franciscan and Dominican convents in the three case study cities. Source: Author’s own work based on the previous study between Santo Domingo and Panama [

11].

On the other hand, it is worth mentioning the role of the female orders, although they were established after the male orders and were therefore less influential in shaping the early urban fabric, they played a very important role in the resilience of the convent typology in these cities.

Table 3.

Female orders in the case study cities. Author’s own work.

Table 3.

Female orders in the case study cities. Author’s own work.

| City |

Female orders in order of arrival |

| La Laguna |

Poor Clares and Dominicans |

| Santo Domingo |

Poor Clares and Dominicans |

| Panama Viejo |

Conceptionists |

La Laguna and Santo Domingo share the same process in terms of female orders. First the Poor Clares, and then the Dominicans (the same orders that stood out in the case of men), settled in these cities and occupied important positions in the city. They usually settled near the Plaza Mayor, where the noble families resided, as many daughters of these families ended up joining these convents as an honour for their families.

As can be seen in

Figure 7, the case of Panama Viejo is different, as only the nuns of the Convent of La Concepción settled in this city.

These buildings (except in the case of Panama Viejo, now in ruins after being moved to another location [

12]) have survived to the present day thanks to their continuous ecclesiastical activity, in contrast to the male convents. They are the best examples of heritage conservation and one of the greatest real estate assets in the cataloguing of these historic centres as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

4.3. Unique and Exceptional Value Recognised by UNESCO

As already mentioned, one of the common threads linking the three cities is their status as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Being included on the List is no easy feat, as it is necessary to demonstrate that a site has outstanding universal value (OUV), unlike other heritage protection measures in individual countries, where the recommendation is that everything of value should be protected. For example, in Spain, according to the Spanish Historical Heritage Law [

13], all defensive architecture, such as

alcazabas (citadels), castles, fortresses, walls, etc., is considered to be of cultural interest and, as such, is protected, regardless of its number, type or similarity. On the contrary, to be included on the UNESCO list, it must be demonstrated that the site is exceptional; there can be nothing else like it on the list. It is understood to be the best example of something [

14], like Noah’s Ark, where only one pair of each species is allowed, with no repetitions. In other words, we move from exhaustive national or regional protection of all existing assets to representative protection of what is universal.

To be included on the list, the property must meet some of the criteria set out by UNESCO and other important requirements such as integrity and authenticity, as well as protection and management requirements.

As we can see in

Table 4, two of the six cultural criteria, (ii) and (iv), are shared by all the cities, and the two American cities also share criterion (vi). Criterion (ii) refers to their urban values, specifically noting their grid pattern (Santo Domingo), grid map (San Cristobal de La Laguna) and colonial Spanish town planning (Panama Viejo), as well as some of their most representative buildings that will be a reference for the future development of the city (cathedral, churches or convents). Criterion (iv) refers to the architecture, typology or character of the site as an architectural ensemble. In all three cases, the architectural coherence of the same historical period, the 16th century, is mentioned as constituting a new social order. Criterion (vi), which is recommended as complementary to others, has an intangible component as it refers to beliefs, ideas, traditions or events. Both in the case of Panama, the spread of European culture in the region, and in the case of Santo Domingo, the spread of evangelisation and the first Leyes de Indias (Laws of the Indies) were proclaimed and enforced, refer to the promotion of religious culture carried out by the different religious communities.

5. Conclusions

The comparative case between La Laguna and the first experiences in America illustrates how this “laboratory” city served as an example for the founding of these colonies, extrapolating important urban keys to understanding the historical process, which would later serve for the Laws of the Indies of 1573, consolidating the entire Spanish colonial urban process.

It has been demonstrated how the grid urban model, which initially emerged in the Iberian Peninsula, was replicated in the Canary Islands in La Laguna and later implemented in the Spanish Caribbean, following a precise urban pattern. In the cities studied, the main premise is adaptability to the existing geography, which in some cases will make it somewhat more irregular than a pure Roman-style grid. On the other hand, this will give each city its own recognisable character.

We have highlighted the role of mendicant orders, both male and female, in the formation of these cities. Similarly, this process emerged from the peninsula, where many of the friars and nuns came from the convents of Seville, the capital of the Spanish Empire at that time, to the new territories, both in the Canary Islands and in America, creating a common thread between these case studies. These cities became major spiritual centres in their regions, with La Laguna being the first bishopric in the Canary Islands and Santo Domingo also being the first bishopric in the Americas.

To differentiate between the different religious congregations, we can highlight the role of the Franciscan and Dominican orders, as they played a leading role in all these cities, as well as in all American expansionism, while the Mercedarians and Augustinians were not as important, although today they are still present in most Latin American countries. It is worth mentioning the case of the Jesuits, as they arrived somewhat later in America and therefore did not have as much impact on the early colonial urbanism of these first cities, but they did play a prominent role in later decades, as they were the main promoters of educational centres in the region. This is undoubtedly a case study to be explored in greater depth in cities founded in the mid- to late 16th century.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the resilience of this type of building, as today the conventual footprint is evident in each of these cities, a key value for which these three cities have been recognised by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. The practical value of this heritage has allowed these monumental buildings to endure over the centuries, and 500 years after most of these constructions were built, we still have an architectural and urban historical legacy of such high value to protect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.-H.; methodology, A.C.-H. and M.T.P.-C.; validation, M.T.P.-C. and F.J.M.-F.; formal analysis, A.C.-H. and M.T.P.-C.; investigation, A.C.-H. and M.T.P.-C.; resources, A.C.-H. and M.T.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-H.; writing—review and editing, M.T.P.-C. and F.J.M.-F.; visualization, A.C.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Serra Ràfols, E. Fontes rerum canariarum IV. Acuerdos del Cabildo de Tenerife (Vol. I, 1497-1507), 2nd ed.; Instituto de Estudios Canarios: San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain, 1996; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- García Guzmán, M.M., El Real Patrono y la villa de Puerto Real en el reinado de los Reyes Católicos. Notas para su estudio. Estudios sobre patrimonio, cultura y ciencias medievales, 2004, V-VI, pp. 81-98.

- Aznar Vallejo, E., La época fundacional y su influjo en el patrimonio histórico de San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, 2008, 54-I, pp. 169-205.

- Rodriguez Yanez, J.M. La Laguna 500 años de historia. Tomo I: La Laguna durante el antiguo régimen. Desde su fundación hasta finales del siglo XVII; Ayuntamiento de San Cristóbal de la Laguna: San Cristóbal de La Laguna, Spain, 1997; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gangui, A. Paisaje Celeste y Arqueoastronomía: Las Iglesias Históricas como indicadores de la planimetría de una ciudad ideal. In Naturaleza y Paisaje. IX Encuentro Internacional sobre Barroco. August 2019. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO World Heritage List. San Cristóbal de la Laguna. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/929 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Muro Orejón, A. La villa de Puerto Real: fundación de los Reyes Católicos. Anuario de historia del derecho español, 1950, 20, 746–757. [Google Scholar]

- Corbella Guadalupe, D. La arquitectura de las ermitas del siglo XVI, en el municipio de La Laguna. In III Coloquio de Historia Canario-Americana. VIII Congreso Internacional de Historia de América. Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2000, pp. 2833-2846.

- De Tomás Medina, C. De las Navas de Tolosa a la fundación de Santo Domingo: Fundamentos de la Ciudad Española en América. PhD Thesis, University of Seville, Seville, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barraza Cardenas, L. Colonial Legacies in Urban Landscapes: A Comparative Analysis of Santo Domingo and Oaxaca. IJPP – Italian Journal of Planning Practice, 2024, 14, 58–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cubero-Hernández, A.; Raony Silva, E.; Arroyo Duarte, S. Urban Layout of the First Ibero-American Cities on the Continent through Conventual Foundations: The Cases of Santo Domingo (1502) and Panama Viejo (1519). Land 2022, 11, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubero-Hernández, A.; Arroyo Duarte, S. Colonial Architecture in Panama City. Analysis of the Heritage Value of Its Monastic Buildings. Designs 2020, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley 16/1985, de 25 de junio, del Patrimonio Histórico Español. Disposición adicional segunda.

- Becerra García, J.M. La conservación de la ciudad histórica en Andalucía. El planeamiento urbanístico como instrumento de protección en el cambio de siglo, Almuzara, Cordoba, Spain, 2020, p. 272.

- UNESCO World Heritage List. Colonial City of Santo Domingo. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/526 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage List. Archaeological Site of Panama Viejo and Historic District of Panama. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/document/1429 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List. Archaeological Site and Historic Centre of Panamá City. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5970/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage List. The Colonial Transisthmian Route of Panamá. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1582 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Patrimonio Panama Site. Available online: https://www.patrimoniopanama.org/?tag=panama-viejo (accessed on 28 October 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).