Introduction

Claudin-6 (CLDN6) is a tetraspan transmembrane protein and member of the tight junction claudin family. It contains four transmembrane helices with two extracellular loops (ECL1 and ECL2) that mediate cell–cell contacts [Qu et al.]. Unlike most other claudins, CLDN6 is essentially absent from healthy adult tissues, being expressed only during embryonic development. This cancer-specific expression makes CLDN6 an appealing therapeutic target, as interventions against CLDN6 are less likely to damage normal adult tissues [Qu et al.]. Indeed, CLDN6 is currently under investigation as a target in cancer immunotherapy. However, obtaining high-affinity binders for CLDN6 has been challenging due to its membrane-bound, multispan architecture.

Traditional methods to discover protein binders involve immunization or large library screening, which can be labor-intensive and offer limited control over binder properties [Baker Lab et al.]. By contrast, computational de novo design offers a faster, more customizable route to create binders targeting specific epitopes. Recent advances in deep learning–guided protein design have markedly improved success rates in designing high-affinity binders from a target’s structure alone [Baker Lab et al.]. In particular, generative models like RFdiffusion can “sculpt” a de novo protein backbone that wraps around a chosen target site, and network-based sequence design tools like ProteinMPNN can then optimize the amino acid sequence for stability and binding [Wang et al.]. By combining these tools, researchers have created novel proteins that bind targets with affinities approaching those of natural antibodies.

Materials and Methods

Computational Binder Design: To design a protein that could recognize CLDN6 with high specificity, we used RFdiffusion to generate new protein backbones guided by a target structure. We provided the extracellular domain of CLDN6, which includes its ECL1 and ECL2 loops, to RFdiffusion as the target input for diffusion modeling. We ran multiple independent diffusion trajectories, gradually extending the binder by two residues at a time to explore different binders and interface geometries.

From roughly one hundred generated backbones, we identified one candidate that showed the most promising interface confidence scores, which is a high iPTM, low iPAE, and favorable interface RMSD, and is supported by visual inspection in PyMOL. This backbone was then selected as the foundation for sequence design and refinement.

Sequence Optimization: We next used ProteinMPNN to design amino acid sequences for this backbone, with the goal of stabilizing both the binder’s fold and its interface with CLDN6. Unlike traditional Rosetta-based sequence design, ProteinMPNN leverages neural networks trained on vast structural data to predict sequences that naturally fit a given 3D fold. This approach is faster and often produces better-packed and more realistic interfaces [Baker Lab et al.]. We generated a wide range of sequence variants and evaluated each for predicted stability, energy, and interfacial complementarity. After ranking and inspection, we selected one sequence and carried it forward for in silico validation.

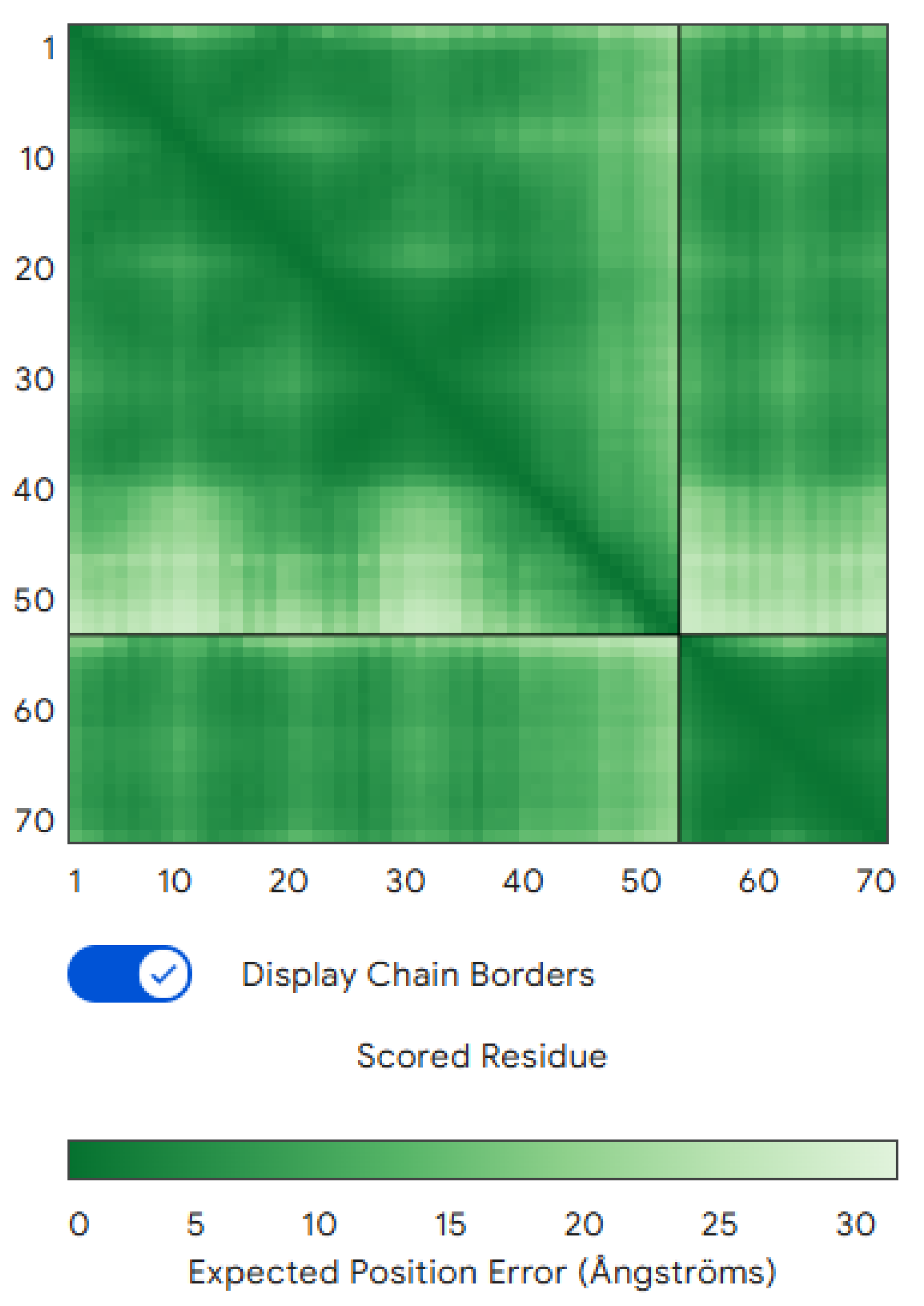

Structure Prediction and Validation: To predict whether the designed binder would fold properly and bind CLDN6 as intended, we used AlphaFold3 (Multimer mode) to model the CLDN6–binder complex, and named it our wildtype. AlphaFold’s predicted interface TM-score (iPTM) for the binder–CLDN6 complex was 0.73, indicating moderate confidence that the two chains interact in the predicted orientation (

Figure 1) [

Watson et al.]. The overall predicted TM-score (pTM) for the complex was 0.83 (with the CLDN6 chain pTM ≈0.72). Notably, the binder chain alone received a very low pTM (~0.2), suggesting that the binder may be intrinsically disordered in isolation and only folds into a stable structure upon binding to CLDN6. Nonetheless, the AlphaFold3 prediction provided confidence that the designed binder can indeed engage CLDN6 at the intended epitope, even if the binder relies on the target for its full structure. We designate CLDN6 as chain A and the binder as chain B in all subsequent analyses.

Figure 1.

Predicted CLDN6–binder complex structure. The AlphaFold3-predicted model of the CLDN6 (chain A) and binder (chain B) complex is shown.

Figure 1.

Predicted CLDN6–binder complex structure. The AlphaFold3-predicted model of the CLDN6 (chain A) and binder (chain B) complex is shown.

Interface Analysis: We evaluated the CLDN6–binder interface using the Rosetta protein modeling suite to calculate key interface metrics. These metrics included the binding energy (Rosetta ΔG_separated, where a more negative value indicates stronger predicted binding), the buried interface surface area (dSASA_int), shape complementarity (SC), and the number of interfacial hydrogen bonds. We also performed computational alanine scanning on the complex to identify “hotspot” residues. In these scans, individual residues at the interface were mutated to alanine, and the change in binding free energy (ΔΔG_bind) relative to the wild-type was computed using Rosetta’s ddG protocol. Residues yielding large positive ΔΔG upon alanine mutation are considered binding hot spots, which contribute significantly to interface affinity [Du et al.].

In Silico Mutagenesis: To probe structure–function relationships and potentially improve affinity, we carried out rational in silico mutagenesis on the binder. Guided by the alanine-scanning results (see Results), we focused on binder positions contacting the identified hotspot region of the epitope. Two variants that were designed and evaluated are B10K and B12W. For each variant, we used Rosetta to relax the complex and compute binding energies and interface metrics as above. Additionally, heavy-atom contacts within 4.5 Å were tallied to generate residue–residue contact maps for the wild-type and mutant interfaces, facilitating visualization of any interface remodeling. All structural models and contact analyses were examined using PyMOL and ChimeraX for visualization.

Computational Setup: All computational design and analysis steps were performed on a Linux platform using standard builds of RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN, AlphaFold3 (multimer), and Rosetta. No experimental (wet-lab) data were generated in this study; all results are predictive and require experimental validation.

Results

Structure Prediction and Initial Interface Properties

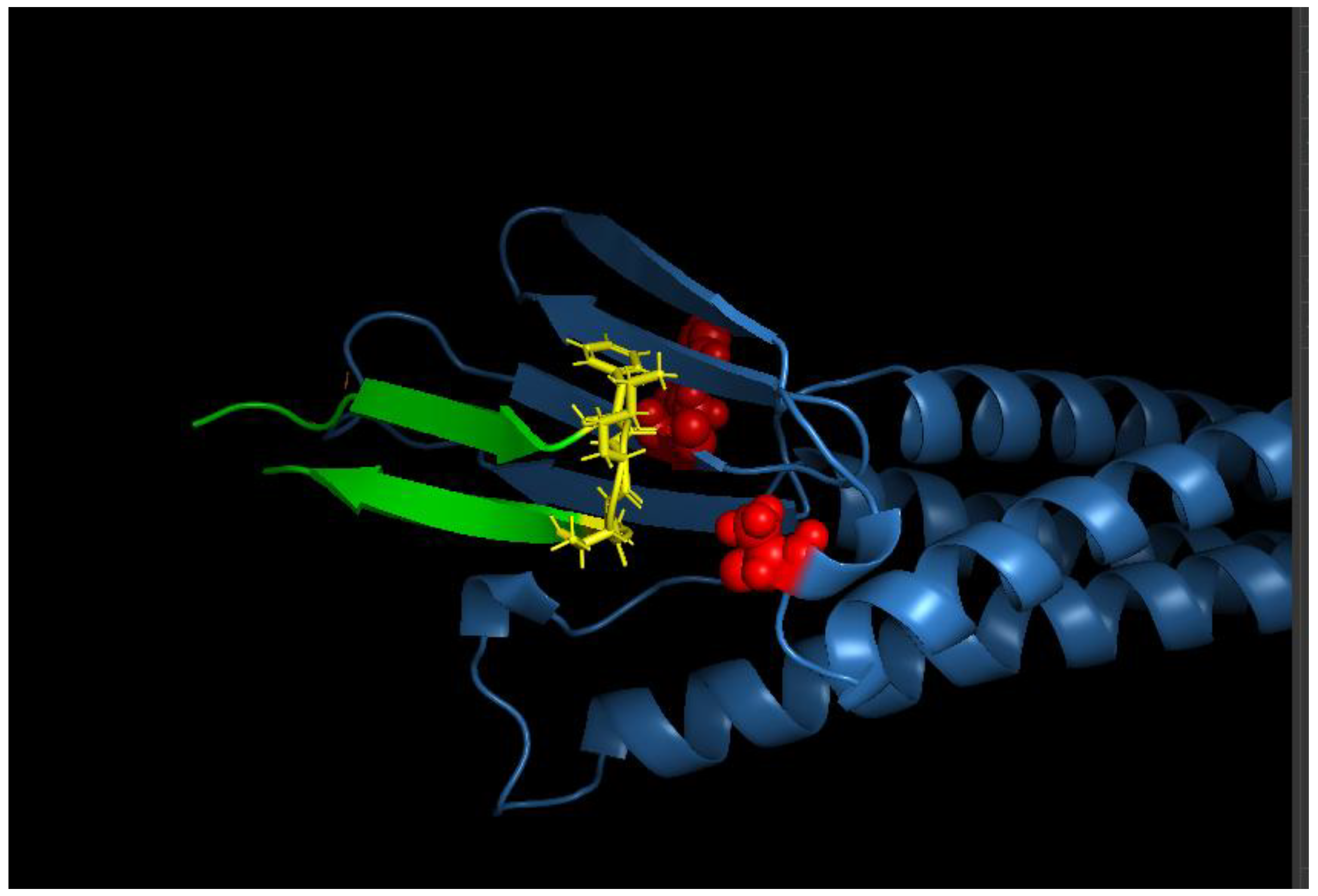

We visualized the protein-binder complex in PyMOL, and the model confirmed that the binder is capable of wrapping around CLDN6’s extracellular region, forming the intended interface (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Design model of the CLDN6 binder interface. A close-up view of the CLDN6–binder interface is shown (visualized in PyMOL). CLDN6 (blue surface) and the binder (green cartoon) interact primarily through the ECL1 region and contacts to ECL2. Key binder side chains forming the interface are shown in stick representation. The designed binder conforms snugly to the CLDN6 surface, with shape complementarity evident from the interlocking surfaces.

Figure 2.

Design model of the CLDN6 binder interface. A close-up view of the CLDN6–binder interface is shown (visualized in PyMOL). CLDN6 (blue surface) and the binder (green cartoon) interact primarily through the ECL1 region and contacts to ECL2. Key binder side chains forming the interface are shown in stick representation. The designed binder conforms snugly to the CLDN6 surface, with shape complementarity evident from the interlocking surfaces.

We next analyzed the predicted CLDN6–binder interface using Rosetta energy calculations. Across an ensemble of 40 relaxed complex models, the average Rosetta interface binding energy (ΔG_separated) was –60.05 ± 0.57 REU, placing it comfortably in the range of high-affinity protein complexes (approximately –40 to –80 REU for many antibody–antigen interfaces). This corresponds to roughly –4.86 ± 0.08 REU per 100 Ų of buried interface area (mean buried surface area ≈1236 ± 19 Ų). About 61% of the buried surface was hydrophobic (≈755 ± 22 Ų). Notably, the total buried area (~1200 Ų) and hydrophobic fraction align with typical values for antibody–antigen interfaces of moderate to high affinity (often on the order of 1200–2000 Ų buried). The Rosetta energy decomposition is consistent with a tightly packed interface: a large favorable van der Waals term (fa_atr ≈ –1332 REU) is partly offset by modest steric repulsion (fa_rep ≈ +145 REU) and desolvation penalties (fa_sol ≈ +751 REU), while electrostatic interactions contribute favorably (fa_elec ≈ –434 REU). The complex also features an extensive hydrogen-bonding network, with ~9–11 interfacial hydrogen bonds (average ~9.6) contributing roughly –239 REU in total hbond energy. On a per-residue basis, interfacial residues (averaging ~55 residues total on both sides) contribute about –3.15 REU each to the binding energy[Fleishman et al.]. These metrics paint a picture of a well-optimized interface dominated by shape complementarity and dispersion forces, with a supportive but not extreme electrostatic component. In summary, the designed binder forms a densely packed, desolvated interface with CLDN6, comparable in quality to natural protein complexes.

Binder Variant Design and Affinity Evaluation

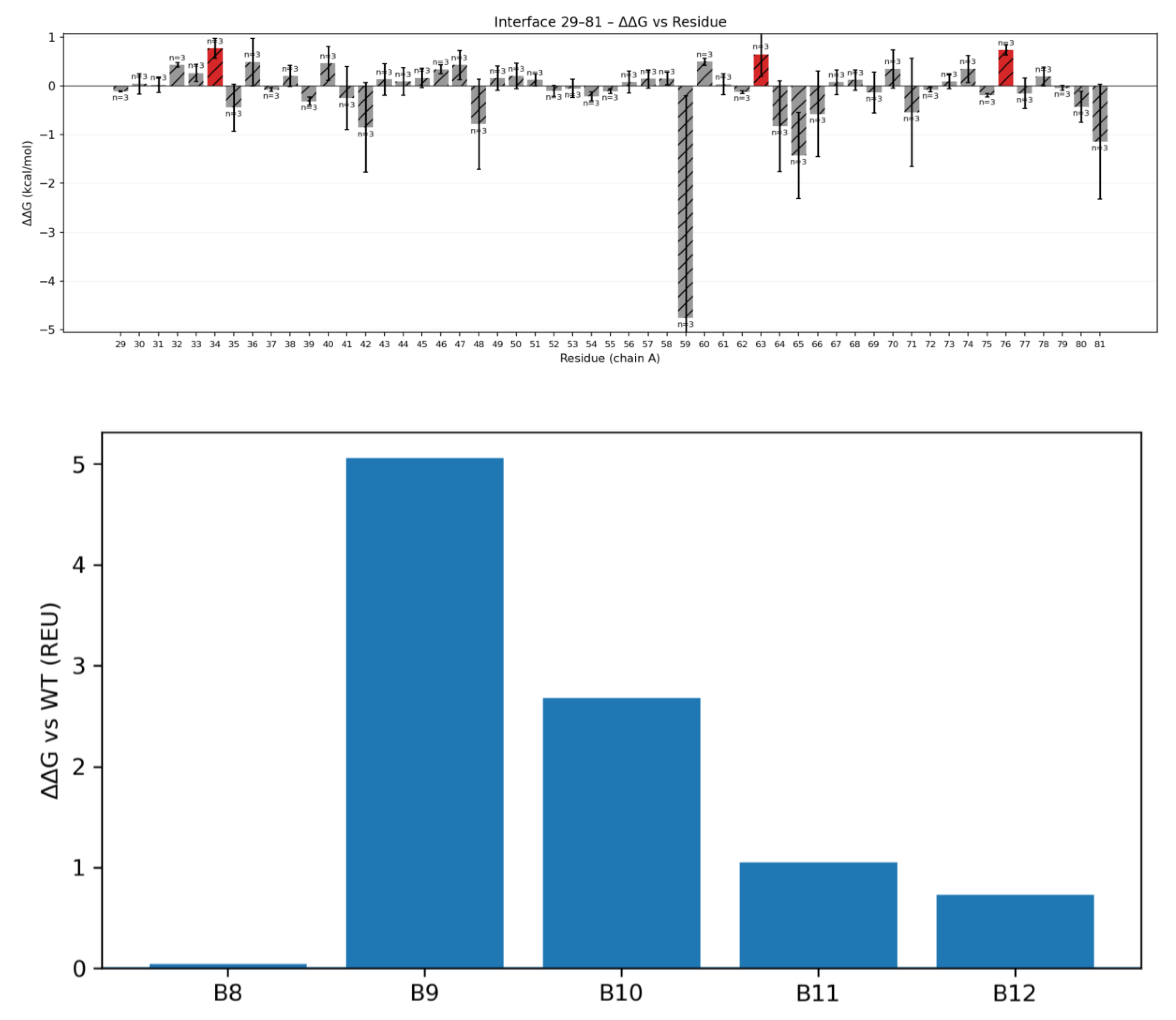

Our wild-type binder showed strong predicted affinity in silico, but we wanted to see if we could push it further through rational mutation design. Based on the hotspot analysis above, we focused on residues B10 and B12. Both sit next to the key hotspot B9 and are positioned near the edge of the interface, making them good candidates for fine-tuning.

Variant B10K:

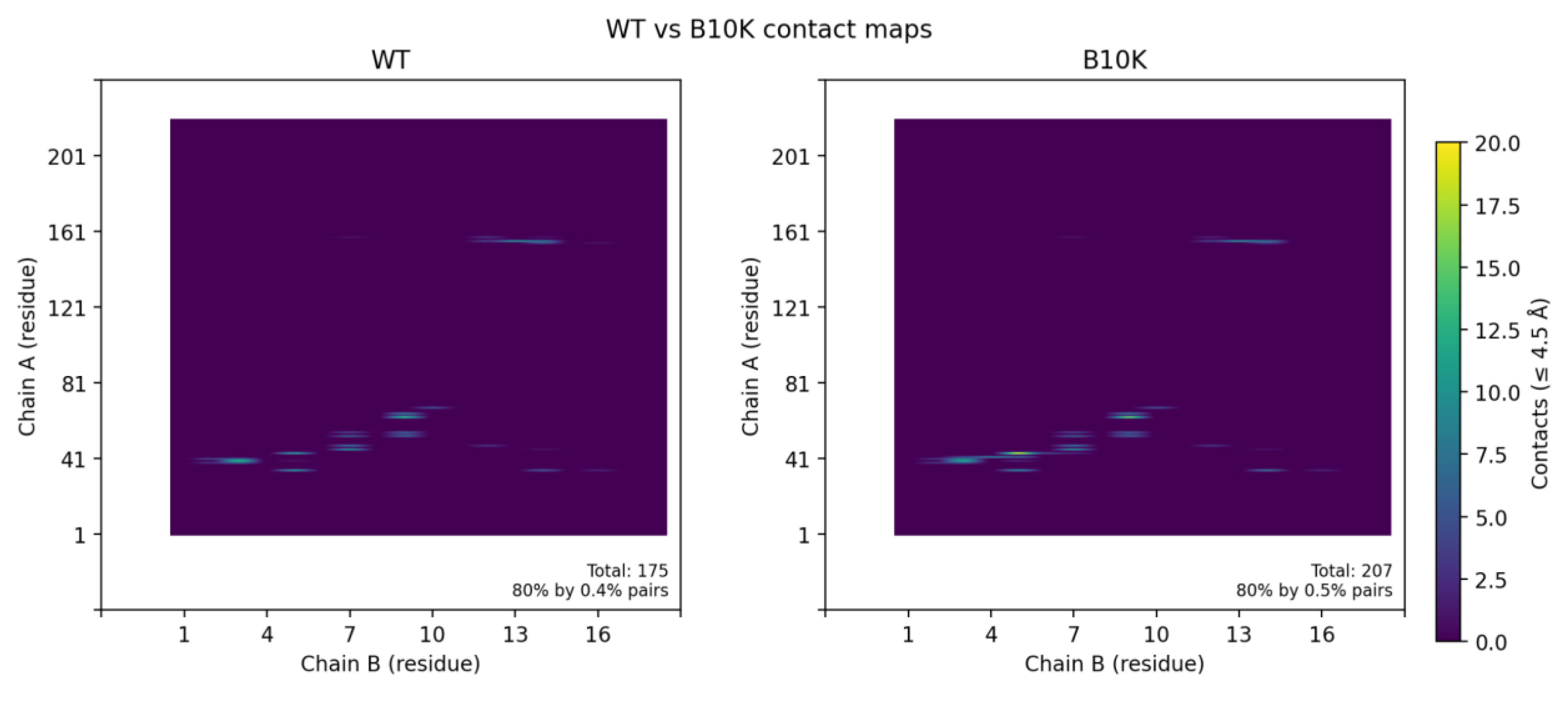

Residue B10 lies beside hotspot B9, which interacts with an acidic patch on the CLDN6 ECL1 loop. Since this region contains several negatively charged residues (Asp and Glu), we reasoned that introducing a positively charged residue at B10 could strengthen electrostatic interactions or form new hydrogen bonds. We substituted lysine at this position, creating variant B10K. Lysine’s long, flexible side chain seemed well-suited to reach into the interface and form potential salt bridges.

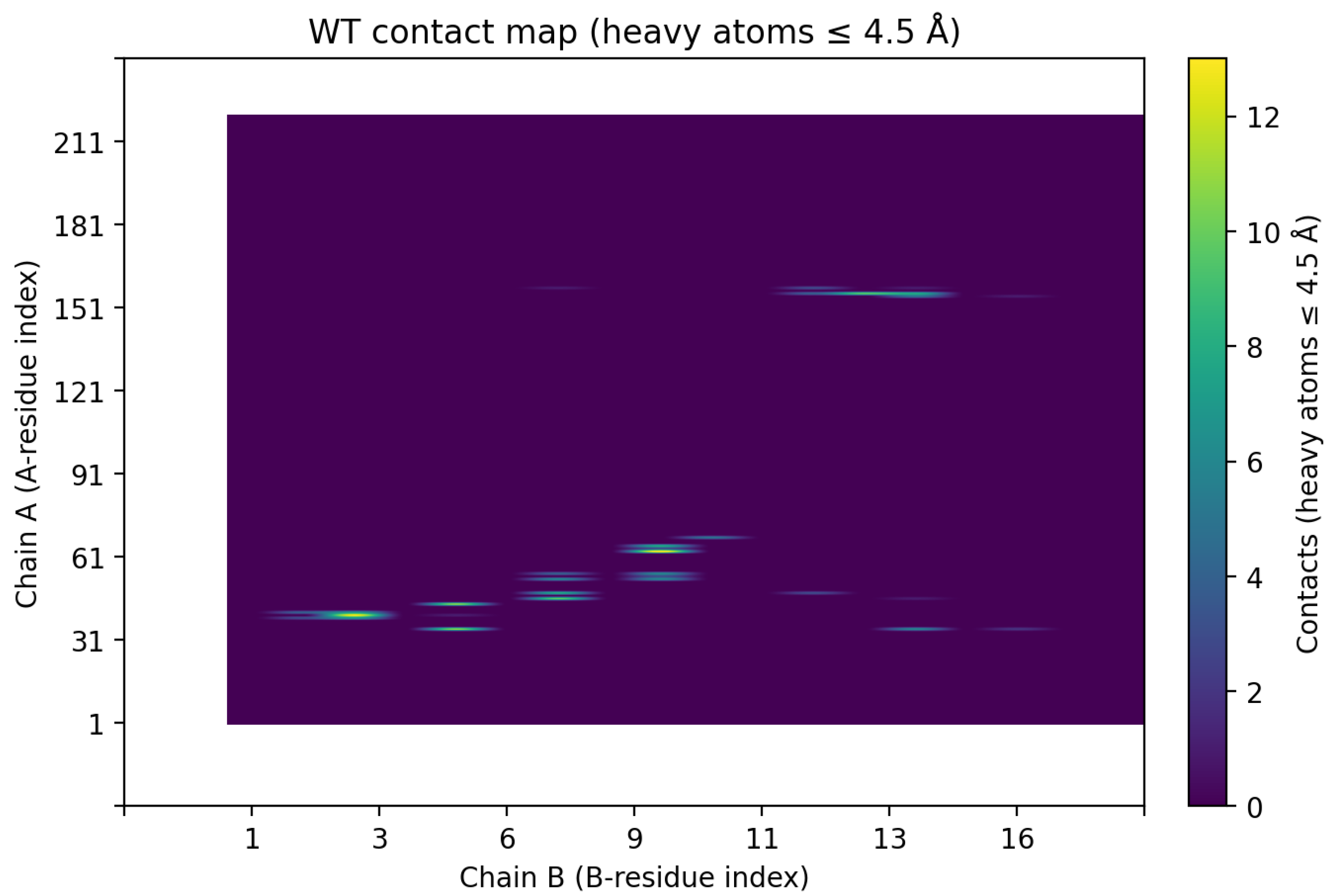

When we relaxed the B10K complex in Rosetta, the predicted binding energy improved slightly by about 0.2–0.3 REU, but this difference falls within the typical uncertainty of Rosetta scoring. Consistent with this, contact map analysis showed that the overall interfacial contacts in B10K were nearly identical to those of the wild-type (

Figure 5A), revealing that B10K doesn’t have better binding interfaces compared to the wild-type.

Figure 5.

Effects of binder mutations on interface contacts. (A) Wild-type vs. B10K contact maps: The residue contact matrix for variant B10K (right) is virtually identical to the wild-type binder (left), indicating that introducing a Lys at binder position 10 does not substantially alter the interface contacts with CLDN6. No new salt bridge or electrostatic interaction was observed; the variant maintains the original binding mode.

Figure 5.

Effects of binder mutations on interface contacts. (A) Wild-type vs. B10K contact maps: The residue contact matrix for variant B10K (right) is virtually identical to the wild-type binder (left), indicating that introducing a Lys at binder position 10 does not substantially alter the interface contacts with CLDN6. No new salt bridge or electrostatic interaction was observed; the variant maintains the original binding mode.

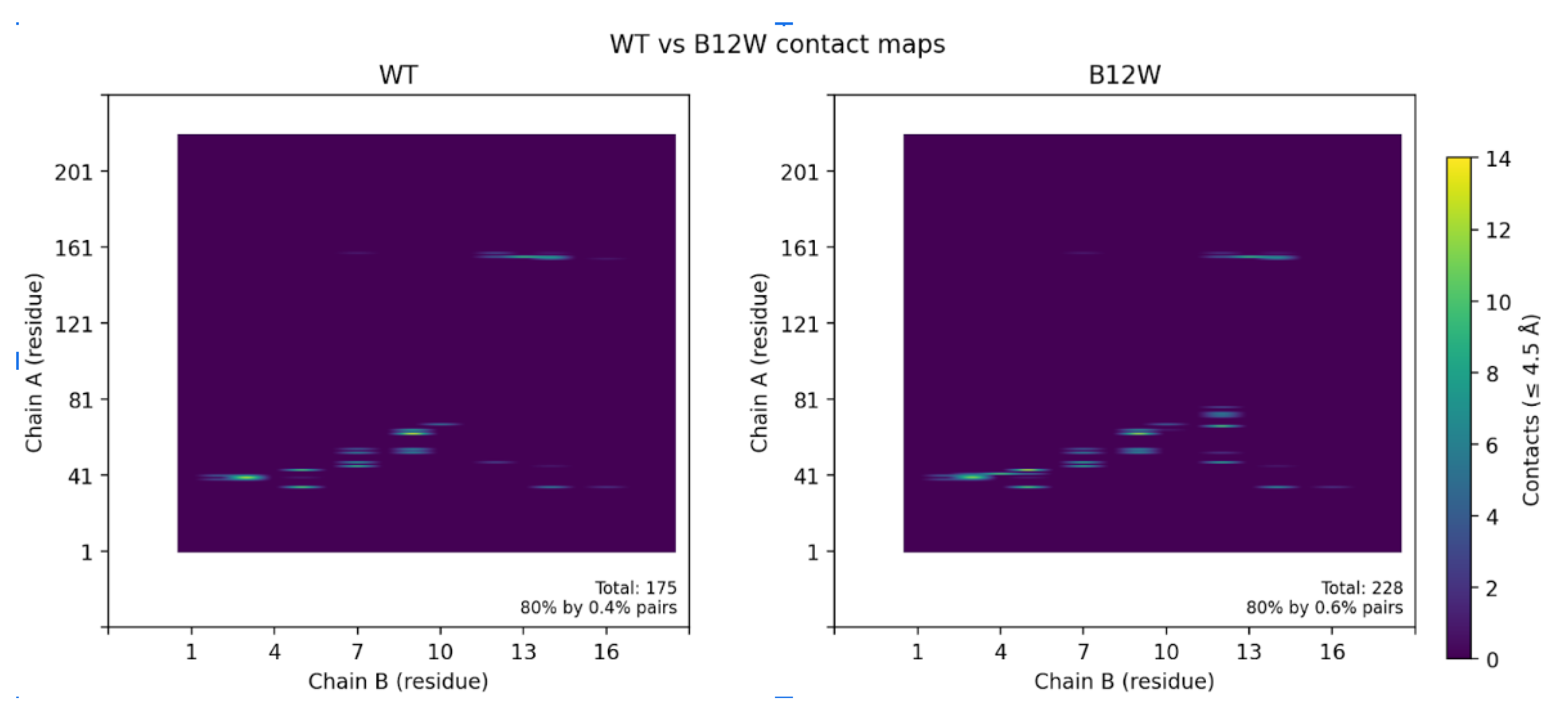

Variant B12W Packing optimization: Binder residue B12 is located at the periphery of the binding interface, next to the critical B9–B10 loop. In the wild-type design, B12 is only partially buried upon complex formation, where its side chain is only partially buried. This means that part of the residue remains solvent-exposed rather than fully shielded within the hydrophobic core. This type of partial burial often signals suboptimal packing, as it leaves small cavities or unpaired hydrophobic surfaces that neither contribute to binding affinity nor structural stability.

To improve this, we conducted an in silico saturation mutagenesis at position B12, evaluating all 20 amino acid substitutions. The screen revealed that aromatic or bulky hydrophobic residues consistently improved predicted binding energies, whereas polar or charged substitutions were often destabilizing. Among all variants, tryptophan (B12W) emerged as the most favorable, suggesting that its large, planar indole ring could effectively occupy a shallow pocket on the CLDN6 surface. The Trp side chain can reinforce local hydrophobic clustering and establish additional π–π or edge-to-face contacts, improving van der Waals complementarity.

The B12W variant improved Rosetta binding energetics relative to wild type. Its average binding free energy (dG_separated) was –67.46 ± 3.31 REU, compared with –60.05 ± 0.57 REU for WT, an improvement of ~–7.41 REU. The interface also grew: dSASA_int = 1383.79 ± 74.58 Ų for B12W vs 1235.85 ± 18.64 Ų for WT (+148 Ų). Both hydrophobic and polar buried surface areas increased (~+130 Ų hydrophobic; ~+18 Ų polar), consistent with Trp12 forming additional contacts. Interfacial hydrogen bonds rose from 9.60 ± 0.55 to 10.45 ± 0.82. Although the larger Trp side chain raised fa_rep (+1.48), this was balanced by a stronger fa_atr (~6.72 REU more favorable). Statistical testing confirmed the directional improvements for B12W over WT as dG_separated decreased by –7.41 REU (Welch one-sided p ≈ 1.6×10⁻¹⁷, 95% CI [–8.34, –6.30]); dSASA_int increased by +148 Ų (p ≈ 5.9×10⁻¹⁶, 95% CI [+123, +170]); hydrophobic and polar contributions rose by ~+130 Ų and ~+18 Ų (p ≤ 3.0×10⁻⁵ each); and interfacial H-bonds increased by +0.85 (p ≈ 3.3×10⁻⁷, 95% CI [+0.55, +1.15]). Although fa_rep increased (+1.48, p ≈ 9.1×10⁻⁴), this was offset by a more favorable fa_atr (–6.72 REU, p ≈ 1.6×10⁻⁸). Overall, B12W creates a tighter, more extensive interface with CLDN6, with gains driven primarily by increased contact area and van der Waals attraction.

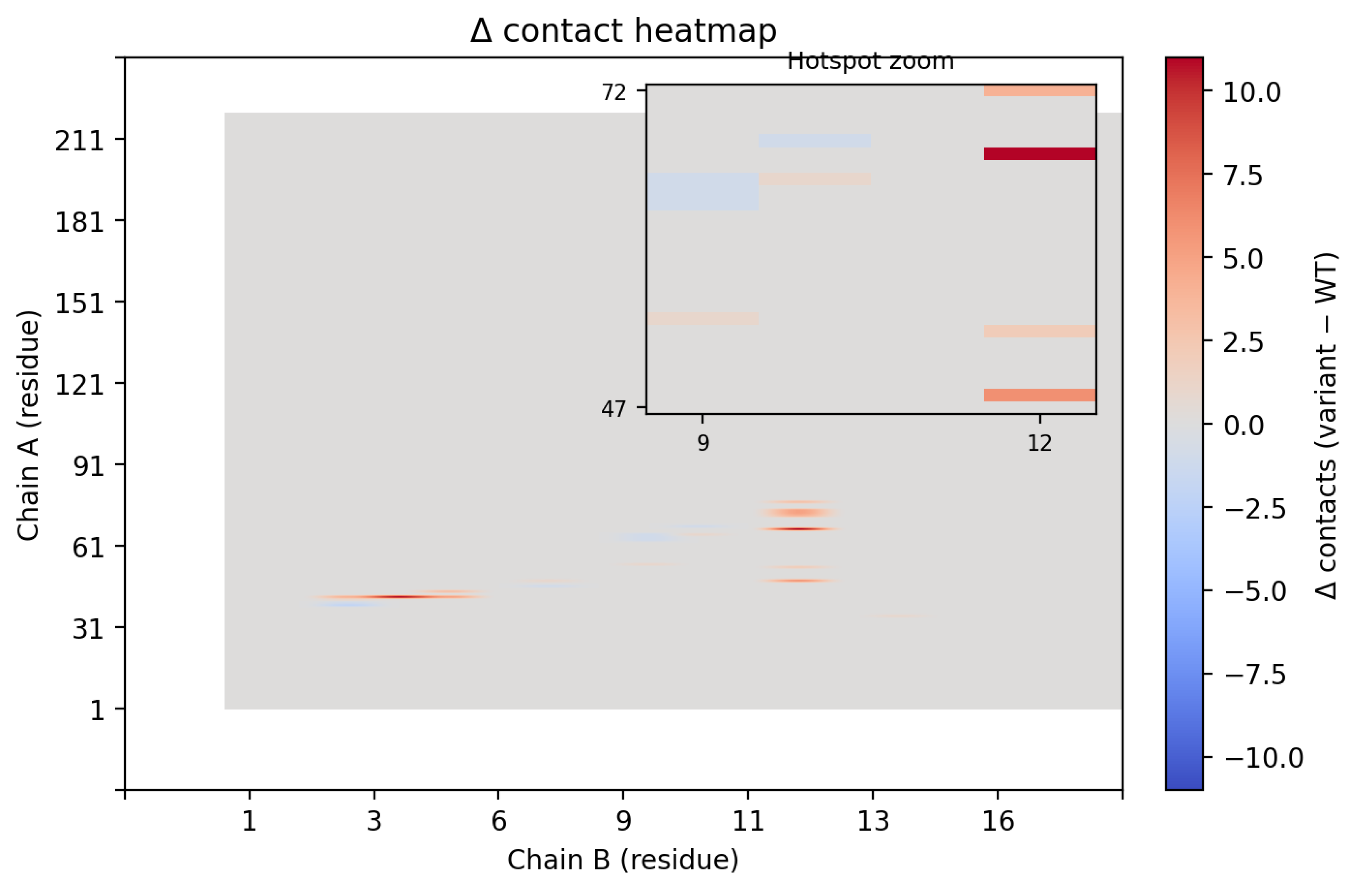

Contact map analysis further supported these findings (

Figure 6). Introduction of Trp12 expanded the interfacial footprint of the binder, increasing the number of residue–residue contacts, particularly between CLDN6 residues 47–72 and binder residue 12. Collectively, these data demonstrate that a single-point substitution at the edge of the binding interface can significantly remodel packing interactions, yielding a tighter, more extensive, and energetically favorable complex.

Figure 6.

(A)Contact maps highlighting the differences between the wild-type binder and the B12W variant. The B12W mutation introduces additional contacts with CLDN6, indicated by the greater density of contact dots. Specifically, Trp12 fills a hydrophobic crevice on CLDN6’s ECL1, increasing the binder’s interfacial complementarity. The broadened contact pattern for B12W correlates with its ~7.4 REU binding energy improvement over the wild-type binder. (B) Contact map contrasting contact points between WT and B12W.

Figure 6.

(A)Contact maps highlighting the differences between the wild-type binder and the B12W variant. The B12W mutation introduces additional contacts with CLDN6, indicated by the greater density of contact dots. Specifically, Trp12 fills a hydrophobic crevice on CLDN6’s ECL1, increasing the binder’s interfacial complementarity. The broadened contact pattern for B12W correlates with its ~7.4 REU binding energy improvement over the wild-type binder. (B) Contact map contrasting contact points between WT and B12W.

Discussion

The CLDN6 binder could have several potential applications in oncology if wet-lab experiments validate the function of this binder. It could function as a steric blocker, attaching directly to CLDN6’s extracellular loops and preventing their participation in tumor-promoting signaling or cell–cell adhesion. In particular, CLDN6’s ECL2 region has been implicated in epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis [Qu et al.]; blocking this surface could help inhibit cancer cell invasiveness and reduce metastatic potential. Such an approach may parallel strategies used for CLDN18.2- and HER2-targeted biologics, which achieve tumor growth inhibition through ligand occlusion rather than cytotoxic payload delivery [Du et al.].

Beyond direct inhibition, the binder could serve as a targeting module across a range of therapeutic and diagnostic platforms. When fused to an Fc domain, it could engage immune effector mechanisms such as antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC) or complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), providing antibody-like activity with a smaller molecular footprint. In an antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) configuration, the binder could guide cytotoxic payloads such as MMAE or DM1 specifically to CLDN6-positive tumor cells, minimizing off-target toxicity. This strategy aligns with the growing success of anti-CLDN6 ADCs like CLDN6–23-ADC, which have shown potent preclinical activity in xenograft models and are progressing through early clinical development [McDermott et al.].

The binder also holds promise in cellular immunotherapy. By incorporating its sequence into a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) construct, engineered T cells could be directed to recognize and eliminate CLDN6-expressing cancer cells. Early-stage trials of CLDN6 CAR-T therapy (e.g., BNT211) have reported encouraging safety profiles and measurable antitumor responses [Mackensen et al.]. Alternatively, conjugating the binder to imaging agents or nanoparticle carriers could enable precise visualization and targeted delivery of therapeutics to CLDN6-positive tumors, aiding both diagnostic imaging and surgical navigation.

For any of these applications, further optimization and validation will be required. Our design already takes advantage of sequence differences unique to CLDN6’s extracellular loops to enhance selectivity, but experimental studies will be critical for confirming this. Because AlphaFold3 suggests that the binder may rely on its target for structural stability, biochemical handling may require stabilizing mutations or fusion to a carrier protein to maintain a folded state in isolation.

By combining deep generative modeling (RFdiffusion), AI-based sequence design (ProteinMPNN), and physics-based validation (Rosetta), this workflow demonstrates that it is now feasible to rationally design high-affinity, target-specific binders from scratch. The CLDN6 binder, therefore serves as an example illustrating how AI-driven protein design can accelerate the creation of new molecular tools for cancer therapy and diagnostics.

Conclusion

This study shows that de novo binder design for challenging membrane proteins is a practical, programmable workflow. By integrating RFdiffusion for backbone generation, ProteinMPNN for sequence design, and Rosetta for energetic refinement, we created a compact protein that forms a stable, high-affinity interface with the extracellular loops of CLDN6. The discovery that a single, strategically placed mutation (B12W) can further strengthen packing and improve predicted binding energy highlights how computational tools can both generate binders and iteratively evolve them.

While all findings here remain in silico, the binder provides a concrete starting point for experimental validation in vitro and in cancer-relevant cell systems. If validated, it could serve as a modular targeting domain for applications ranging from CAR-T and ADC platforms to imaging probes and competitive inhibitors that block CLDN6-mediated signaling. More broadly, this work illustrates how AI-guided protein design can accelerate the development of selective agents against oncofetal targets that are difficult to target with traditional antibody discovery methods.

References

- Abramson, J., Adler, J., Dunger, J., Evans, R., Green, T., Pritzel, A., Ronneberger, O., Willmore, L., Ballard, A. J., Bambrick, J., Bodenstein, S. W., Evans, D. A., Hung, C., O’Neill, M., Reiman, D., Tunyasuvunakool, K., Wu, Z., Žemgulytė, A., Arvaniti, E., . . . Jumper, J. M. (2024). Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature, 630(8016), 493–500. [CrossRef]

- Bakerlab. (2024, March 9). Designing binders with the highest affinity ever reported • Baker Lab. Baker Lab • UW Institute for Protein Design. https://www.bakerlab.org/2023/12/19/designing-binders-with-the-highest-affinity-ever-reported/#:~:text=The%20study%20introduces%20a%20novel,peptide%E2%80%99s%20amino%20acid%20sequence%20alone.

- Du, H., Yang, X., Fan, J., & Du, X. (2021). Claudin 6: Therapeutic prospects for tumours, and mechanisms of expression and regulation (Review). Molecular Medicine Reports, 24(3). [CrossRef]

- Fleishman, S. J., Leaver-Fay, A., Corn, J. E., Strauch, E.-M., Khare, S. D., Koga, N., Ashworth, J., Murphy, P., Richter, F., Lemmon, G., Meiler, J., & Baker, D. (2011). RosettaScripts: A scripting language interface to the Rosetta macromolecular modeling suite. PLoS ONE, 6(6), e20161. [CrossRef]

- Tyka, M. D., Keedy, D. A., André, I., Dimaio, F., Song, Y., Richardson, D. C., Richardson, J. S., & Baker, D. (2011). Alternate states of proteins revealed by detailed energy landscape mapping. Journal of Molecular Biology, 405(2), 607–618. [CrossRef]

- Khatib, F., Cooper, S., Tyka, M. D., Xu, K., Makedon, I., Popovic, Z., Baker, D., & Players, F. (2011). Algorithm discovery by protein folding game players. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(47), 18949–18953. [CrossRef]

- Mackensen, A., Haanen, J. B., Koenecke, C., Alsdorf, W., Wagner-Drouet, E., Borchmann, P., Heudobler, D., Ferstl, B., Klobuch, S., Bokemeyer, C., Desuki, A., Lüke, F., Kutsch, N., Müller, F., Smit, E., Hillemanns, P., Karagiannis, P., Wiegert, E., He, Y., . . . Şahin, U. (2023). CLDN6-specific CAR-T cells plus amplifying RNA vaccine in relapsed or refractory solid tumors: the phase 1 BNT211-01 trial. Nature Medicine, 29(11), 2844–2853. [CrossRef]

- McDermott, M. S., O’Brien, N. A., Hoffstrom, B., Gong, K., Lu, M., Zhang, J., Luo, T., Liang, M., Jia, W., Hong, J. J., Chau, K., Davenport, S., Xie, B., Press, M. F., Panayiotou, R., Handly-Santana, A., Brugge, J. S., Presta, L., Glaspy, J., & Slamon, D. J. (2023). Preclinical efficacy of the antibody–drug conjugate CLDN6–23-ADC for the treatment of CLDN6-Positive solid tumors. Clinical Cancer Research, 29(11), 2131–2143. [CrossRef]

- Qu, H., Jin, Q., & Quan, C. (2021). CLDN6: From traditional barrier function to emerging roles in cancers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(24), 13416. [CrossRef]

- Simon, A. G., Lyu, S. I., Laible, M., Wöll, S., Türeci, Ö., Şahin, U., Alakus, H., Fahrig, L., Zander, T., Buettner, R., Bruns, C. J., Schroeder, W., Gebauer, F., & Quaas, A. (2023). The tight junction protein claudin 6 is a potential target for patient-individualized treatment in esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma and is associated with poor prognosis. Journal of Translational Medicine, 21(1). [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Liu, C., & Deng, L. (2018). Enhanced prediction of hot spots at Protein-Protein interfaces using extreme gradient boosting. Scientific Reports, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. L., Juergens, D., Bennett, N. R., Trippe, B. L., Yim, J., Eisenach, H. E., Ahern, W., Borst, A. J., Ragotte, R. J., Milles, L. F., Wicky, B. I. M., Hanikel, N., Pellock, S. J., Courbet, A., Sheffler, W., Wang, J., Venkatesh, P., Sappington, I., Torres, S. V., . . . Baker, D. (2023). De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature, 620(7976), 1089–1100. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).