1. Introduction

Semantic segmentation provides fine-grained, pixel-level understanding of visual scenes, making it a cornerstone for safe and reliable perception in autonomous driving systems. This task enables vehicles to accurately identify and localize objects such as pedestrians, vehicles, road signs, and lane markings, ensuring effective decision-making in dynamic and often unpredictable traffic environments. Traditionally, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been the dominant backbone for semantic segmentation due to their strong capability in local feature extraction and hierarchical representation learning [

1]. Architectures such as Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) [

2], U-Net [

3], and DeepLab variants [

4] have demonstrated significant progress in achieving high accuracy and efficiency across large-scale benchmark datasets. However, CNNs often struggle to capture long-range dependencies and contextual relationships across the image, limiting their ability to generalize to complex driving scenes that involve diverse object scales, occlusions, and spatial arrangements.

In response to these limitations, transformer-based architectures have recently gained momentum in the semantic segmentation domain. Unlike CNNs, transformers excel in modeling global context and long-range interactions through self-attention mechanisms, which makes them particularly effective in capturing semantic relationships across the entire visual field. SegFormer, a notable transformer-based model [

5], distinguishes itself by introducing a hierarchical transformer encoder that progressively captures multi-scale representations while maintaining computational efficiency. Unlike conventional Vision Transformers (ViTs) [

6], SegFormer does not rely on positional embeddings, instead leveraging overlapping patch embeddings to preserve spatial information more naturally. Its lightweight all-MLP decoder is designed to aggregate multi-level features effectively, eliminating the need for computationally heavy upsampling operations while still delivering strong segmentation accuracy.

While SegFormer has demonstrated state-of-the-art results on large and well-curated datasets such as Cityscapes [

7], its performance on smaller, geographically diverse datasets such as CamVid [

8], KITTI [

9], and Indian Driving Dataset (IDD) [

10] remains relatively underexplored. These datasets present unique challenges compared to Cityscapes: CamVid is smaller in scale and provides fewer annotated frames, KITTI emphasizes real-world driving environments with sensor-specific variations, and IDD introduces significant diversity in terms of weather, lighting, traffic density, and road infrastructure representative of non-Western contexts. Assessing SegFormer on such datasets is crucial for understanding its robustness, generalization ability, and adaptability to real-world deployment scenarios, especially in cases where training data are limited or exhibit significant domain shifts. This exploration not only informs the suitability of transformer-based models for practical autonomous driving systems, but also highlights directions for enhancing their efficiency, generalizability, and domain adaptation capabilities.

This paper addresses two major gaps in the current research, i.e., Understanding how different SegFormer variants scale on a smaller dataset like CamVid in terms of performance and computational cost. Investigating the effectiveness of cross-dataset transfer learning from CamVid to KITTI (Germany) and IDD (India), each representing structured and unstructured driving environments respectively.

Additionally, this work is an extension of our work presented a segmentation based transformer architecture for urban scene segmentation [

11]. In this paper, we extend the previous work by considering more complex dataset and have introduced explainability into the evaluation pipeline using confidence heatmaps, allowing us to visually interpret uncertainty of the model and quality of decision at the pixel level. The contribution of this paper is divided into three folds.

A systematic evaluation of SegFormer variants (B3, B4, B5) on CamVid to study the effects of scaling the architecture.

Implementation of cross-dataset transfer learning from CamVid to KITTI and IDD, including custom class mapping strategies.

Introduction of confidence heatmaps to visualize the certainty of model prediction and aid explainability in safety-critical contexts.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews prior work; Section 3 details our methodology; Section 4 describes datasets and class mappings; Section 5 outlines evaluation metrics and experimental results; and Section 6 concludes the paper with insights and future directions.

2. Related Work

Semantic segmentation has progressed substantially with the advent of deep learning, evolving from convolution-based architectures to transformer-driven designs. Early approaches such as Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) and SegNet [

12] introduced encoder-decoder frameworks that extracted spatial features using convolutional layers. Later models like DenseNet-based Tiramisu [

13] improved training stability through dense skip connections and deep supervision. These CNN-based models were effective for structured scene parsing, but often struggled with modeling long-range dependencies and global context.

To address real-time constraints in autonomous systems, efficient architectures such as BiSeNet [

14] adopted dual-path designs to balance spatial precision and a receptive field. PIDNet [

15] leveraged principles from control theory to better handle multiscale information, while RTFormer [

16] demonstrated that transformer-based designs could match CNN efficiency in real-time settings. These approaches prioritized inference speed, but often at the expense of segmentation accuracy in complex scenes.

Transformer-based segmentation models marked a turning point, with SegFormer [

5] emerging as a notable breakthrough. Its hierarchical transformer encoder, overlapped patch embeddings, and Mix-FFN layers enabled strong global context modeling while preserving local structure outperforming convolutional models on Cityscapes with fewer parameters. Further innovations like Skip-SegFormer [

17] and CFF-SegFormer [

18] extended this architecture with improved multiscale feature fusion and decoder efficiency.

In parallel to architectural advancements, transfer learning has become essential for scenarios where labeled data is scarce. DAFormer [

19] showed that domain-adaptive segmentation using transformers could generalize well across synthetic and real domains. However, most prior work has focused on large-scale benchmarks or synthetic to real adaptation. The generalization of the cross-data set between small real-world datasets, such as CamVid, KITTI, and IDD, remains underexplored. This is particularly relevant for developing perception systems intended for deployment across diverse geographic regions. Our study addresses this gap by systematically evaluating SegFormer’s transferability from CamVid to both KITTI and IDD.

Interpretability is increasingly recognized as a key aspect of trustworthy segmentation. Bayesian SegNet [

20] pioneered uncertainty modeling using Monte Carlo dropout. More recent approaches explore class activation maps (CAM), attention visualizations, and confidence heatmaps to make dense predictions more interpretable. Although explainable AI (XAI) has advanced for classification tasks, its integration with transformer-based segmentation remains limited. Our work contributes to this area by introducing confidence heatmaps as a diagnostic tool to expose model uncertainty and failure points in urban scene segmentation.

In summary, previous research has laid the foundation for efficient, accurate, and adaptive segmentation. However, the combined challenges of scaling transformer models, transferring them across real-world datasets, and interpreting their predictions remain open. We address this intersection by evaluating SegFormer’s performance under scaling, cross-dataset transfer, and explainability constraints bringing a unified perspective to transformer-based semantic segmentation.

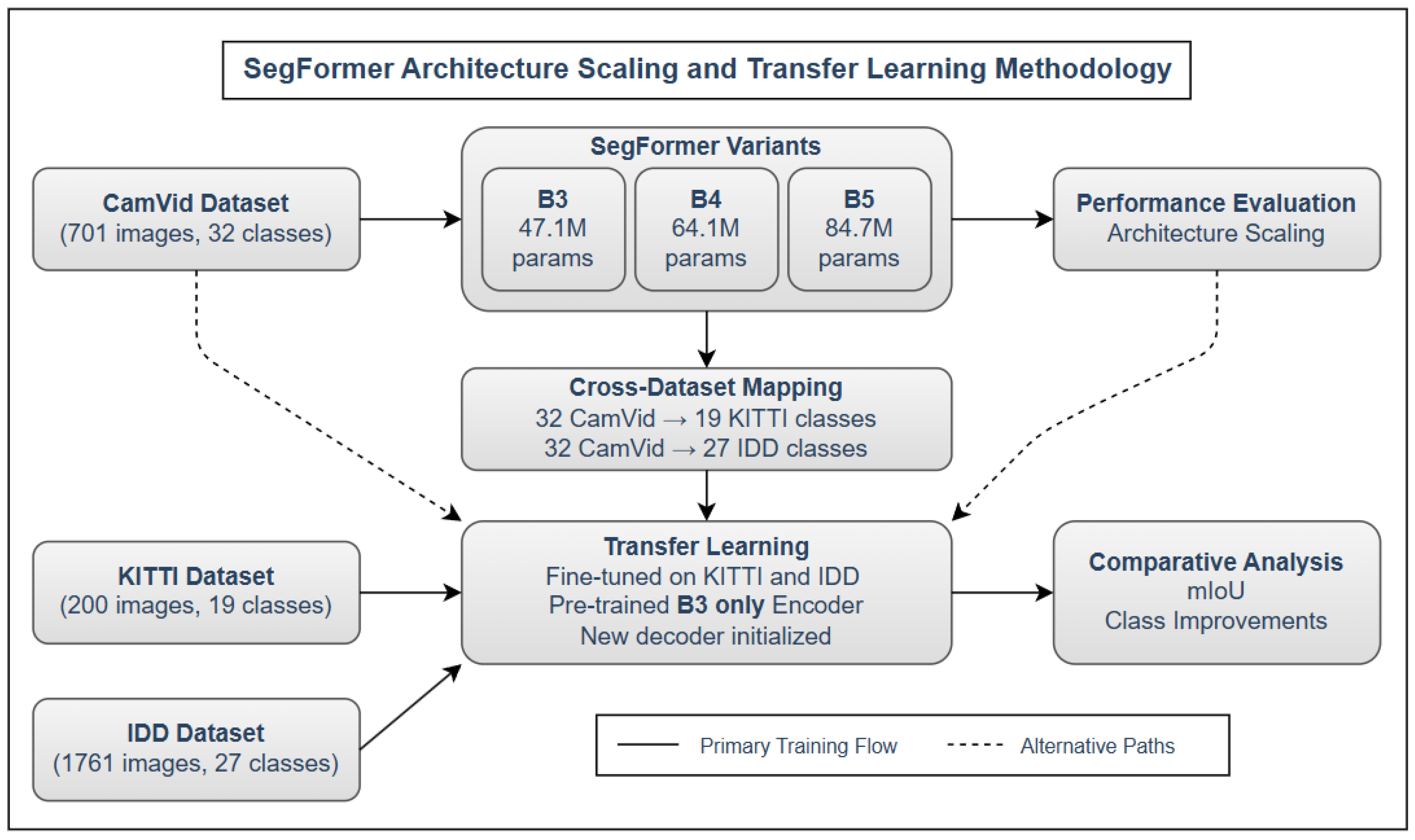

Figure 1.

End-to-end pipeline: SegFormer variants are trained on CamVid, transferred to KITTI and IDD with class mappings, and interpreted via confidence heatmaps.

Figure 1.

End-to-end pipeline: SegFormer variants are trained on CamVid, transferred to KITTI and IDD with class mappings, and interpreted via confidence heatmaps.

3. Datasets and Cross-Dataset Mapping

To evaluate both architectural scalability and cross-domain transferability, we used three publicly available urban driving datasets: CamVid, KITTI, and IDD. These datasets represent different geographical locations, label taxonomies, and annotation densities, making them suitable benchmarks for our study.

The

Cambridge-driving Labeled Video Database (CamVid) [

21] contains 701 densely annotated frames (

resolution) extracted from video sequences captured in the UK. It includes 32 semantic classes covering roads, buildings, pedestrians, vehicles, the sky, and street furniture. We used the standard split: 367 training images, 101 validation, and 233 testing images. Due to its clean annotation and balanced scene composition, CamVid serves as the source domain for model scaling and transfer learning.

The

KITTI Semantic Segmentation Benchmark [

22] offers 200 high-resolution images (

) from urban driving scenes in Germany. It follows a 19-class taxonomy derived from Cityscapes, focusing on structured environments with well-defined object boundaries. Due to its relatively small sample size and the partial overlap of the labels with CamVid, KITTI is selected as a target domain for cross-dataset transfer.

The Indian Driving Dataset (IDD) captures diverse and unstructured driving scenes in India. It contains 10,004 images annotated with 27 semantic classes, including region-specific categories such as autorickshaw, guard rail, and billboard. For consistency and computational feasibility, we use a subset comprising 1761 training and 350 validation samples. IDD introduces a significant visual domain, including varied lighting, occlusions, and unconventional vehicle types—making it a challenging but valuable target domain.

To facilitate effective transfer learning from CamVid to target datasets, we establish a structured class mapping protocol. Since each dataset follows its own label taxonomy, alignment is necessary to preserve semantic consistency and ensure correct feature adaptation. Our mapping strategy categorizes class relationships into three types, as summarized in

Table 1.

To handle novel classes, we reinitialize the decoder weights while preserving the CamVid-pretrained encoder. This allows the network to reuse generalized features and adapt them to new class boundaries and appearance patterns during fine-tuning. This strategy ensures semantic consistency while enabling flexible cross-dataset transfer in geographically and structurally diverse urban scenes.

4. Methodology

Our proposed methodology investigates the scalability, transferability, and interpretability of transformer-based segmentation using SegFormer. The experimental design is divided into three major stages: (1) model scaling experiments using CamVid; (2) cross-dataset transfer learning to KITTI and IDD; and (3) application of confidence-based interpretability techniques to evaluate model reliability.

4.1. SegFormer Architecture Overview

SegFormer [

5] consists of three core components: (i)

Overlapping Patch Embedding to preserve spatial details, (ii) a

Hierarchical Transformer Encoder that extracts multi-scale contextual features, and (iii) a

Lightweight Decoder that fuses these features via an MLP and performs semantic prediction.

We consider three SegFormer variants—B3, B4, and B5—differentiated by model size, capacity, and architectural configurations:

B3: With 47.1M parameters, this variant employs a hierarchical structure of 12 transformer layers distributed across 4 stages (2,3,6,3), where each stage operates at progressively reduced spatial resolutions of , , , and . It utilizes a hidden dimension of 512 in the deeper layers and a reduction ratio of 1 in its efficient self-attention mechanism.

B4: The intermediate variant contains 64.1M parameters with 12 transformer layers arranged in a (2,2,8,2) configuration across the four stages. B4 employs a larger embedding dimension of 640, increasing its capacity to model complex relationships while maintaining reasonable computational demands.

B5: The largest variant with 84.7M parameters, B5 maintains the (2,2,8,2) layer distribution of B4 but expands the embedding dimension to 768. This provides substantially increased representational capacity and attention width, allowing for more nuanced feature extraction and relationship modeling.

All three variants share the same lightweight MLP decoder structure, which aggregates multi-level features from the hierarchical encoder through a simple yet effective design. For all variants, we employ the same efficient self-attention mechanism with a linear complexity of

instead of the standard quadratic

complexity, achieved through a sequence reduction process. This attention mechanism is mathematically expressed as:

where

R represents the reduction operation that decreases the sequence length by a factor of the reduction ratio.

4.2. Cross-Dataset Transfer Learning

We use CamVid as the source domain for transfer learning due to its structured annotations and clean urban scenes. SegFormer-B3 serves as the base model for knowledge transfer. For each target dataset—KITTI and IDD—we perform the following steps:

Initialize the encoder using CamVid-pretrained weights.

Re-initialize the decoder to match the target dataset’s class taxonomy.

Adapt input-output pipelines using custom class mappings.

Fine-tune the model with a reduced learning rate to avoid catastrophic forgetting.

Our mapping strategy includes:

Direct Mappings (e.g., road → road)

Semantic Mappings (e.g., bicyclist → rider)

Novel Classes (e.g., autorickshaw in IDD)

4.3. Transfer Learning Algorithm

To formalize our cross-dataset knowledge transfer approach, we present Algorithm 1, which details the process of transferring learned representations from a source urban scene dataset (CamVid) to target datasets (KITTI and IDD) with different class taxonomies and visual characteristics.

|

Algorithm 1 Cross-Dataset Knowledge Transfer for Semantic Segmentation |

- 1:

Input: Source dataset with classes, Target dataset with classes - 2:

Input: Class mapping function

- 3:

Output: Target-adapted model

- 4:

Phase 1: Source Domain Pretraining - 5:

Initialize SegFormer model with random weights - 6:

Train on using loss function

- 7:

Store optimized source parameters

- 8:

Phase 2: Cross-Domain Parameter Transfer - 9:

Initialize target model with encoder weights from

- 10:

Randomly initialize decoder parameters of for classes - 11:

Apply class mapping M to align source and target semantics - 12:

Phase 3: Target Domain Fine-tuning - 13:

Set learning rate

- 14:

for epoch to max_epochs do

- 15:

Update by minimizing on

- 16:

Evaluate on validation set

- 17:

if early stopping criterion met then

- 18:

break

- 19:

end if

- 20:

end for - 21:

return optimized target model

|

4.4. Loss Function

To ensure robust learning across imbalanced classes and complex boundary regions, we employ a multi-component loss function that addresses various aspects of semantic segmentation quality:

The class-weighted cross-entropy component

addresses class imbalance by applying inverse frequency weighting:

where

is the ground truth,

is the predicted probability, and

is the class weight calculated as

, with

being the frequency of class

c in the training set.

The IoU loss component

focuses on optimizing the Intersection over Union metric directly:

The boundary-aware component

enhances precision at class transitions:

where

is the set of boundary pixels identified using a Sobel edge detector on the ground truth, and

is a distance-based weight that emphasizes pixels closer to boundaries.

The coefficients and were determined through systematic grid search on the validation set. This configuration achieved an optimal balance between overall segmentation accuracy and boundary precision.

4.5. Explainability via Confidence Heatmaps

To interpret model behavior, we generate confidence heatmaps that visualize softmax entropy per pixel. These maps provide spatial cues on:

High-confidence regions (well-learned objects)

Uncertain predictions (occlusions, rare classes)

Model confusion at boundaries

These visualizations help reveal failure modes, guide further training improvements, and support safer model deployment in real-world scenarios.

5. Evaluation Metrics and Results

This section presents a rigorous quantitative and qualitative assessment of our SegFormer experiments across CamVid, KITTI, and IDD datasets. We first establish the mathematical foundation of our evaluation framework, then analyze the performance of different SegFormer variants and the effectiveness of our cross-dataset transfer learning approach.

5.1. Mathematical Formulation of Evaluation Metrics

Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) measures the overlap between predicted and ground truth segmentation masks for each class, then averages across all classes:

In our CamVid experiments, semantic classes, while KITTI uses classes and IDD uses classes.

Pixel Accuracy (PA) quantifies the overall proportion of correctly classified pixels:

Convergence Acceleration Factor (CAF) measures the reduction in training time:

Class-Specific Transfer Gain (CSTG) quantifies the improvement for each semantic class after transfer learning:

5.2. Architecture Scaling Analysis on CamVid

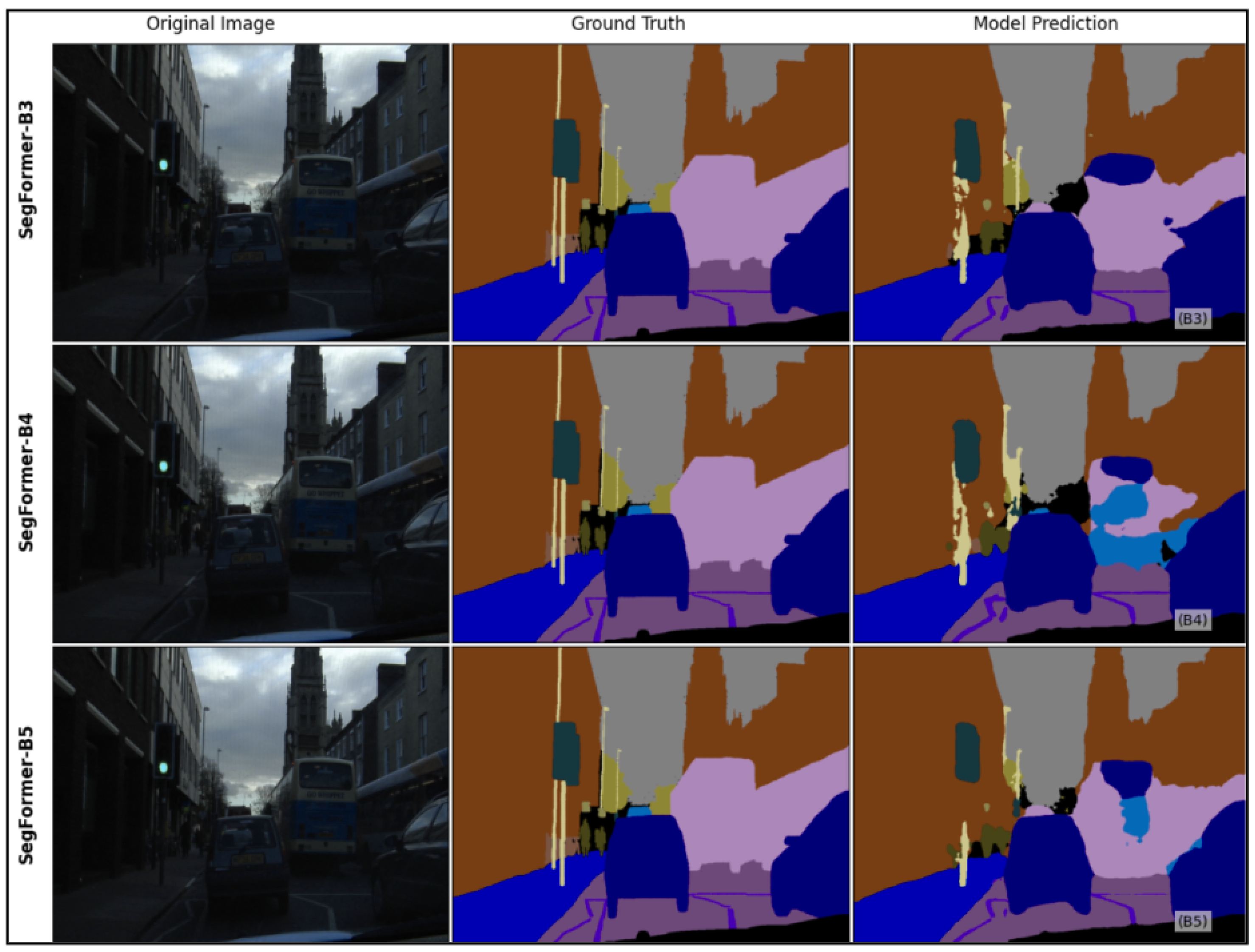

We systematically evaluated three SegFormer variants (B3, B4, and B5) on the CamVid dataset to understand the relationship between model capacity and segmentation performance.

Table 2 summarizes our findings.

The relationship between model size and performance follows a sub-linear pattern, indicating diminishing returns as model capacity increases. While SegFormer-B5 achieves the highest accuracy, the performance gain over B3 (+4.5% mIoU) comes at the cost of significantly increased parameters (+80%) and inference time (+29.6%).

For our cross-dataset transfer learning experiments, we selected SegFormer-B3 as the base model due to its favorable balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Figure 2.

Qualitative segmentation results of SegFormer variants on CamVid. Larger models show improved boundary precision and semantic consistency.

Figure 2.

Qualitative segmentation results of SegFormer variants on CamVid. Larger models show improved boundary precision and semantic consistency.

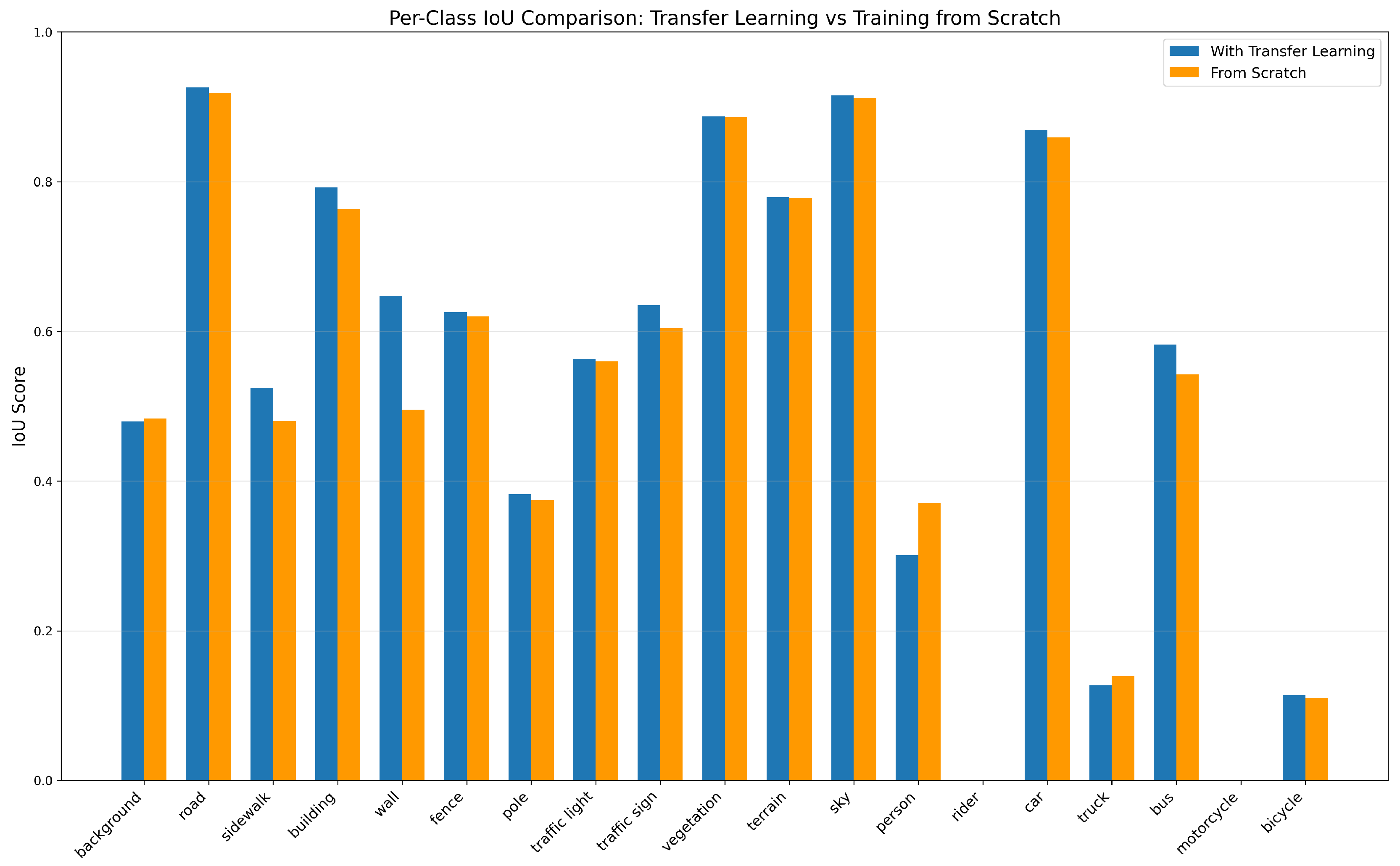

5.3. KITTI Transfer Performance

We transferred knowledge from CamVid (source domain) to KITTI (target domain) by initializing a SegFormer-B3 model with weights pre-trained on CamVid, then fine-tuning on KITTI training data.

Table 3 quantifies the class-specific benefits of this transfer learning approach.

Figure 3.

Per-class IoU comparison between transfer learning (blue) and training from scratch (orange) on KITTI. Classes with complex features and limited examples show the greatest relative improvements.

Figure 3.

Per-class IoU comparison between transfer learning (blue) and training from scratch (orange) on KITTI. Classes with complex features and limited examples show the greatest relative improvements.

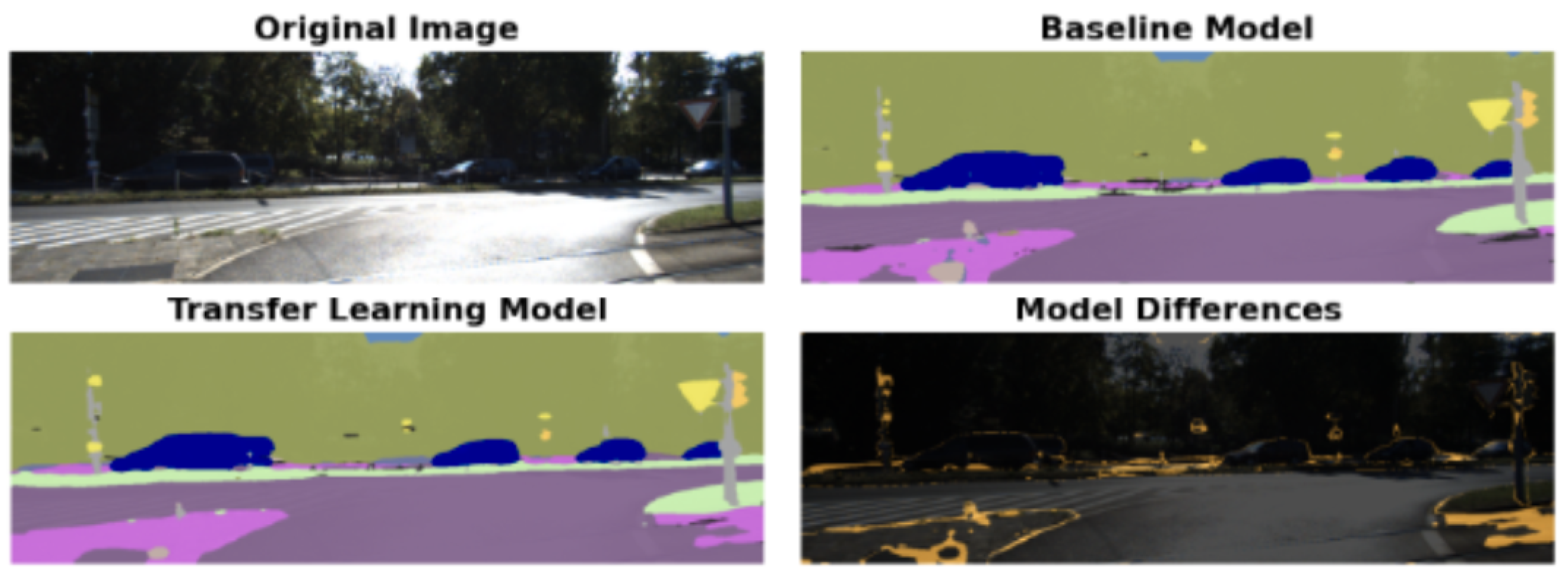

The magnitude of improvement varies significantly across classes, with structural elements showing the largest gains. The overall mIoU improvement from 52.08% to 53.42% may appear modest, but this aggregate metric obscures the substantial class-specific gains. Moreover, the training efficiency improvement is dramatic, with a 61.1% reduction in training time from 18 epochs to 7 epochs.

Figure 4.

Qualitative results on KITTI. Top left: Original image. Top right: Baseline model prediction. Bottom left: Transfer learning model prediction. Bottom right: Model differences visualization.

Figure 4.

Qualitative results on KITTI. Top left: Original image. Top right: Baseline model prediction. Bottom left: Transfer learning model prediction. Bottom right: Model differences visualization.

5.4. IDD Transfer Performance

The Indian Driving Dataset presents a more challenging transfer scenario due to greater visual differences from European urban scenes.

Table 4 shows that transfer learning yields even larger improvements on IDD than on KITTI.

Figure 5.

Per-class IoU comparison between transfer learning (blue) and training from scratch (orange) on IDD. Much larger improvements demonstrate transfer learning benefits for datasets with greater domain shift.

Figure 5.

Per-class IoU comparison between transfer learning (blue) and training from scratch (orange) on IDD. Much larger improvements demonstrate transfer learning benefits for datasets with greater domain shift.

The remarkably high improvement for "Motorcycle" (+72.74%) can be attributed to low baseline performance due to class imbalance and visual complexity, combined with transferable features from similar classes in CamVid. Even classes unique to IDD like "Autorickshaw" benefit from transfer learning (+15.87%), demonstrating that lower-level features learned from CamVid transfer effectively despite semantic differences.

Figure 6.

Qualitative results on IDD showing improved segmentation of region-specific vehicles and structures.

Figure 6.

Qualitative results on IDD showing improved segmentation of region-specific vehicles and structures.

6. Explainability and Interpretability

While performance metrics such as mean Intersection-over-Union (mIoU) and pixel-wise accuracy provide essential quantitative benchmarks for evaluating semantic segmentation models, they often fall short in explaining the underlying reasoning behind model predictions. To bridge this interpretability gap, we incorporate two complementary techniques—confidence heatmaps and Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM).

Confidence heatmaps serve as a visual indicator of the model’s certainty in its predictions. For each pixel, the confidence score is defined as the maximum softmax probability across all classes:

This scalar value reflects the model’s belief in its most likely prediction at that location. As illustrated in

Figure 7, high-confidence regions typically correspond to well-represented classes like roads and vehicles, while low-confidence regions often cluster around ambiguous areas, class boundaries, and occluded objects.

Grad-CAM is employed to generate class-specific activation maps, enabling us to probe the model’s internal reasoning. The technique computes the gradient of the class-specific logit

with respect to the activation maps

of the final convolutional layer. The final Grad-CAM heatmap

for class

c is obtained by:

where

are importance weights for each channel. As shown in

Figure 8, each class triggers distinct regions of activation, with road class activations across pavement areas and pole class activations in vertical regions.

To examine generalizability across diverse driving environments, we evaluate Grad-CAM outputs on CamVid and IDD datasets. The CamVid dataset features dense urban traffic with frequent pedestrian and bicycle interactions. As illustrated in

Figure 9, the model shows broader, more diffused attention around dynamic objects, while stationary classes maintain sharp activations.

The IDD dataset poses greater challenges due to unstructured Indian street scenes. As shown in

Figure 10, attention remains strong for high-frequency classes like road and vegetation, but becomes scattered for occluded classes, reflecting increased model uncertainty in complex contexts.

6.1. Visual Results with Prediction Overlay

To supplement our quantitative metrics and interpretability analyses, we present qualitative visualizations demonstrating SegFormer-B3’s segmentation capabilities across diverse real-world driving environments.

Figure 11 shows results from the CamVid dataset, where the model demonstrates strong performance in delineating core urban classes such as roads, sidewalks, and buildings, as well as dynamic objects like cyclists and pedestrians.

Figure 12 depicts results on the KITTI dataset, featuring structured suburban driving scenes. SegFormer-B3 exhibits precise segmentation of road surfaces, curbs, and sidewalks, with clear improvements from transfer learning.

Figure 13 presents segmentation examples from the IDD dataset with unstructured Indian street scenes. Despite the complexity, SegFormer-B3 accurately segments roads, vehicles, and adapts well to underrepresented classes after transfer learning.

These visualizations collectively illustrate that SegFormer-B3 generalizes well across varying spatial layouts and lighting conditions, demonstrating its suitability for real-time, resource-constrained environments like autonomous vehicles.

7. Discussion and Future Work

This study presented a comprehensive evaluation of SegFormer for urban scene segmentation, contributing significant insights across three key dimensions: architecture scaling, cross-dataset transfer learning, and model interpretability.

Our architectural scaling experiments on CamVid demonstrated that while SegFormer-B5 achieves the highest accuracy at 82.4% mIoU, the efficiency-performance trade-off favors the more balanced SegFormer-B3 variant for practical deployments. The relationship between model capacity and performance follows a sub-linear pattern, with diminishing returns as parameter count increases—an important consideration for resource-constrained autonomous systems.

Our cross-dataset transfer learning investigation revealed that knowledge acquired from CamVid can significantly enhance segmentation performance on both structurally similar environments (KITTI) and substantially different driving contexts (IDD). The transfer benefits were particularly pronounced for classes with limited training examples and complex geometric structures, with improvements as high as 30.75% for "Wall" in KITTI and 72.74% for "Motorcycle" in IDD. Moreover, transfer learning dramatically reduced training time by 61.1% on KITTI, demonstrating considerable practical value for model adaptation across geographic regions.

Our interpretability analysis incorporated both confidence heatmaps and Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to enhance transparency into the model’s internal decision-making. Confidence heatmaps allowed us to visualize model certainty at the pixel level, while Grad-CAM provided class-specific saliency visualizations. This layer of explainability is critical for safety-critical applications such as autonomous driving, where understanding the rationale behind predictions is essential for trust and deployment readiness.

These multifaceted contributions offer significant value for real-world autonomous systems facing the challenges of varied deployment conditions, limited labeled data availability, and requirements for model explainability. By demonstrating SegFormer’s adaptability across diverse urban environments, our work provides a foundation for developing more geographically robust perception systems.

8. Conclusion

Several promising directions are extended from our current findings. First, exploring multisource pretraining and domain adaptation strategies could further enhance model generalization. Rather than transferring from a single source dataset, simultaneously utilizing knowledge from multiple geographically diverse datasets could create more universal feature representations and model specification based on explainability. Secondly, by evaluating and interpreting SegFormer deployment on embedded hardware platforms would address real-world implementation challenges. Quantifying the latency-accuracy trade-offs across different computational constraints would provide practical guidelines for autonomous vehicle manufacturers and smart city developers.

By pursuing these research directions, we anticipate significant advancements in the development and deployment of efficient, transferable, and interpretable segmentation models for urban scene understanding across diverse global environments.

References

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation; CVPR, 2015.

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation; MICCAI, 2015.

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. ECCV 2018, DeepLabv3. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W. ; Yu,.Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS); NeurIPS Proceedings, 2021.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale; ICLR (Vision Transformer, 2020.

- Cordts, M.; et al. The Cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding; CVPR, 2016.

- Brostow, G.J.; Shotton, J.; Fauqueur, J.; Cipolla, R. Semantic object classes in video: A high-definition ground truth database; Pattern Recognition Letters (CamVid, 2009.

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Urtasun, R. Are we ready for autonomous driving? The KITTI vision benchmark suite; CVPR, 2012.

- Varma, G.; et al. IDD: A dataset for exploring problems of autonomous navigation in unconstrained environments; WACV, 2019.

- Hatkar, T.S.; Ahmed, S.B. Urban scene segmentation and cross-dataset transfer learning using SegFormer. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Machine Vision and Applications (ICMVA 2025); Osten, W.; Jiang, X.; Qian, K., Eds. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, Vol. 13734; 2025; p. 1373406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jégou, S.; Drozdzal, M.; Vazquez, D.; Romero, A.; Bengio, Y. The One Hundred Layers Tiramisu: Fully convolutional DenseNets for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the CVPR Workshops; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yu,.C.; Wang, J.; Peng, C.; Gao, C.; Yu,.G.; Sang, N. BiSeNet: Bilateral segmentation network for real-time semantic segmentation. In ECCV; IEEE, 2018.

- Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, B.; Yang, W. PIDNet: A real-time semantic segmentation network inspired by PID controllers. In ECCV; Springer Science, 2022.

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Chen, K.; Wang, X.; Hu, J. RTFormer: Efficient design for real-time semantic segmentation with transformer. In CVPR; IEEE, 2022.

- Tang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, W. Skip-SegFormer: Efficient semantic segmentation for urban driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Systems; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Wei, X.; Chen, J. CFF-SegFormer: Lightweight network modeling based on SegFormer. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 84372–84384. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer, L.; Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. DAFormer: Improving network architectures and training strategies for domain-adaptive semantic segmentation. In CVPR; IEEE, 2022; pp. 10157–10167.

- Kendall, A.; Badrinarayanan, V.; Cipolla, R. Bayesian SegNet: Model uncertainty in deep convolutional encoder-decoder architectures for scene understanding. In BMVA; British Machine Vision Association, 2016.

- Brostow, G.J.; Fauqueur, J.; Cipolla, R. Semantic object classes in video: A high-definition ground truth database. Pattern Recognition Letters 2009, 30, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The KITTI dataset. International Journal of Robotics Research 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).