1. Introduction

As the recent COVID pandemic demonstrated, most Western countries are facing a healthcare crisis caused by demographic change. The ageing society is increasing the number of people in need of care, while the number of carers is stagnating. Like most of its European neighbours, Germany is facing increasing demand for health care, exacerbated by multimorbidity, chronic diseases and the impact of COVID-19 on HCW and system constraints [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. A predicted shortage of 500,000 nurses by 2023 and rising care costs are prompting political actions to cut services due to economic constraints [

6]. Moreover, nurses report insufficient time for direct patient care, urging supportive solutions [

7].

At the same time, robots are becoming increasingly important in addressing healthcare shortages [

8]. Although surgical robots became popular in the last decade, SRs are now following due to affordability, advances in computing power, autonomous navigation and human interaction [

9,

10,

11]. Germany’s initiative lags behind Japan’s adoption of robotics for healthcare in ’smart hospitals’, highlighting the need for progress in areas such as TMed [

6,

12,

13]. Robots, working alongside human HCW, could alleviate labour shortages [

14]. Capable of performing repetitive tasks, interacting with infectious patients, and working tirelessly, robots offer patient guidance, entertainment, transportation, and TMed without the need for rest or maintenance [

10,

12,

15]. Shifting such non-empathic tasks to robots has received positive responses from HCW [

16,

17]. However, there are challenges to their integration in healthcare: A fragmented technology landscape and vendor-specific ecosystems limit interoperability [

17,

18,

19]. In addition, the use of closed source software and the lack of universal interfaces prevent operation across different SRs, leading to limited collaboration [

11,

19,

20].

The complexity of hospital environments requires SRs to integrate with existing systems and ensure safe operation around vulnerable people, requiring reliability and safety features such as collision avoidance. However, hospitals lack the technical expertise and HCW for seamless robot integration, limiting their ability to exploit SRs capabilities [

21]. Close collaboration and testing between developers, researchers and HCW is recommended for implementation [

10].

To address these challenges, we propose hospOS, a system that facilitates the interaction between SRs, building infrastructure and stakeholders, while ensuring regulatory compliance in hospitals. hospOS emerged from the SMART FOREST 5G Clinics research project and is now in a prototype stage. The system is currently being evaluated in two hospitals in Lower Bavaria and will be expanded as the project progresses. As hospOS is a work in progress, we have not covered security, version control, diagnostics, remote monitoring, cybersecurity, stability and persistence in detail in this paper. The code from the research project is continuously updated and available as open source

1. Our paper argues for and contributes a blueprint for a centralised robot orchestration platform to connect to existing hospital infrastructure and facilitate the management of SRs. This paper is an extended version of the paper by Schmidt et al. [

22]. To measure the benefits of hospOS, this paper quantifies the time savings in two of the three use cases presented.

2. Related Work

Healthcare SRs cover a wide range of tasks, from helping to move goods to providing assistance to hospital staff, patients and visitors. In the healthcare sector, SRs mainly focus on cleaning, hospital logistics, remote monitoring and TMed, a trend accelerated by COVID-19 [

10]. SRs reduce the physical burden on HCW, for example by transporting heavy loads and thereby reducing their workload [

17].

2.1. Challenges in SRs Orchestration

Existing SRs focus on a single task, such as cleaning, while hospitals require a technical solution that covers many functionalities, from teleconsultation to transport [

10,

11]. Therefore, it seems advantageous to use a system that is able to manage different SRs.

The integration of SRs in the large area of hospitals with lifts, non-electric fire doors, moving obstacles and vulnerable people poses a number of challenges. Due to the lack of interoperability, integration challenges must be solved on a per robot basis or through a robot management system [

19,

20].

Many SRs are neither compliant with national privacy regulations nor customisable to the needs of the hospital. The different software frameworks (ROS, OpenRTM, OPROS) and the proprietary nature of these systems lead to high costs and complexity in customisation, making them less feasible for budget-constrained hospitals [

23].

Healthcare providers have a knowledge gap in SRs management, creating a need for accessible tools that do not require extensive programming skills. The lack of technicians in hospitals exacerbates this challenge and calls for user-friendly solutions [

9].

2.2. Existing Solutions

Software is available to organise and support hospitals, for example to manage patient meal orders from tablets in patients’ rooms. These systems streamline the process by efficiently routing requests to nurses.

TMed SRs focus primarily on video delivery, providing ancillary information and limited hardware support. Some SRs also act as platforms, organising networks of specialist doctors to facilitate remote consultation and treatment [

13].

Robot manufacturers offer control solutions for their SRs, including smartphone apps to manage multiple SRs. However, these systems are limited to the manufacturer’s own products and their built-in functions, and lack cross-compatibility with other systems. Most commercially available robots are built using the open source robot operating system (ROS), so their internal software architecture is similar. Their internal software is often closed and the application programming interfaces (APIs) is restricted to allow the manufacturer to lock users into a walled garden. Thus, to make robots hospOS compatible, an application must be built and run on each robot. In

Section 4 we detail the requirements for a robot vendor provided API to be integrated with hospOS.

Specialised healthcare SRs, mostly developed in research, are becoming more common. Companies are beginning to adopt SRs from the hospitality sector for use in healthcare. In Germany, notable examples include Fraunhofer’s Care-o-bot and Charite’s ERIC. However, these non-commercial prototypes often don’t comply with hospital regulations, are expensive, require high maintenance, have limited availability and are complex technical systems [

9,

10,

12].

Robot management systems capable of orchestrating individual SRs exist in the industry [

10]. However, the requirements are different: In an industrial context, the focus is more on process optimisation with more freedom according to sensors, such as radar on the ceiling of a workshop. As this is not possible in hospitals, hospOS relies on the internal mapping data and building plans of different robots, from which a common map is calculated. To complicate matters further, SRs are closed systems with far fewer interfaces, while industrial SRs are open systems designed for external control. hospOS includes functions such as TMed and must comply with regulations.

3. Benefits of hospOS

A more holistic, multi-robot system can address the range of healthcare tasks and therefore support the introduction of SRs in hospitals [

10,

24,

25]. hospOS serves as a centralised system for the orchestration of SRs with the aim of increasing the efficiency of SRs. It aims to address staff shortages through automation, improving service delivery and functionality of SRs.

It is designed as an independent modular system to leverage the strengths of different SRs while reducing their complexity and providing interoperability with existing hospital IT systems. It is designed to facilitate widespread adoption of SRs in healthcare by supporting a range of use cases, allowing hospitals to tailor the system to their specific needs. Its focus on ease of use and seamless integration with existing systems is designed to reduce the IT burden on hospitals.

The system features an interface developed with input from HCWs, prioritising user-centricity for wider adoption [

26]. It improves patient safety and compliance by automating routine tasks, allowing clinicians to focus on direct patient care.

The consistent operation and real-time monitoring capabilities of hospOS comply with hygiene standards, certification guidelines and local regulations in Germany.

4. Design and Functions of hospOS

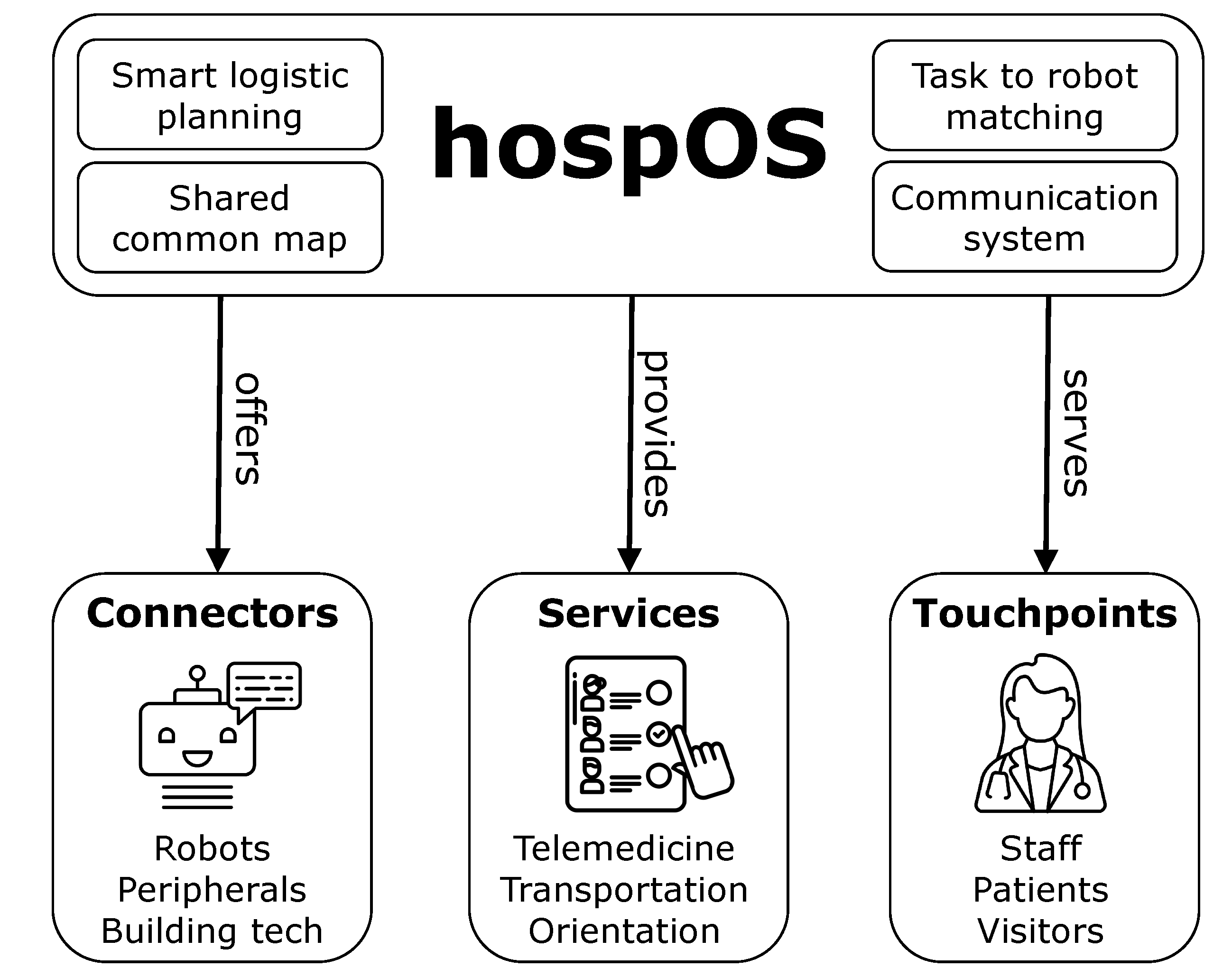

Figure 1 shows that the hospOS architecture consists of a core and three key components. The core component encapsulates the intelligent logistics planning, a common map derived from the building plan and individual maps of the SRs, the task to robot matching logic and the communication system. In addition, the connector component contains connectors to different SRs models, SRs peripheral hardware, e.g. an additional camera for TMeds, and building technology, e.g. elevators and doors. hospOS provides services for each use case, e.g. TMeds, transport and orientation. Individual touchpoints per stakeholder and service are also served by hospOS in order to adapt the user experience to the user group.

Application Interface Requirements

hospOS provides a generalised interface for robot-system interaction. The interface has to be implemented within the hospOS client application running on the robot to overcome the different technical specifications (sensors, operating systems, APIs) of different SRs. The interface requires SRs to provide information of the following four types

Heartbeats including the robot’s current status (charging, ready, doing, error), battery level and IP. Address.

Map data consisting of a point cloud or image and the position of the robot on the map.

Task Types of tasks that are implemented and can be processed by the robot.

Robot functionalities, e.g. navigation or UI.

On each SRs type, a dedicated application must be implemented with the interface functions of hospOS, tailored to the technical characteristics of the SRs.

System Integration

Integrating SRs into hospOS involves setting them up in the orchestration system, which is accessible via a web-based interface designed for hospital staff and IT administrators. SRs are registered with the system using their IP address. Once registered, SRs are managed through hospOS by different roles, such as IT administrators who assign updates. hospOS can trigger maintenance, such as charging. hospOS ensures that each SRs is used effectively within its capabilities, increasing the efficiency of hospitals. Instead of developing a complicated robot that can provide all services, we aim to combine SRs with few skills.

User Interface Requirements

Due to the variety of users interacting with hospOS, the interfaces should be adapted to their specific needs and requirements to increase acceptance [

27].

HCW can use the system to request services provided by hospOS, e.g. TMeds, transport of materials and patient orientation services.

Patients can use the system to order goods to their room and to participate in TMeds consultations.

Visitors can use the system for guidance, orientation and information, e.g. opening hours.

User interaction can take place via SRs and their tablets or via local web applications accessed via computers or smartphones. To facilitate integration with existing hospital information systems and streamline the management of organizational data, the interfaces are built based on the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard. This enables hospOS in the long term to effectively interact with other systems in the hospital, such as scheduling, logistics, and resource management platforms, ensuring that relevant organizational information is consistently available across different user interfaces and systems.

4.1. Communication Flow

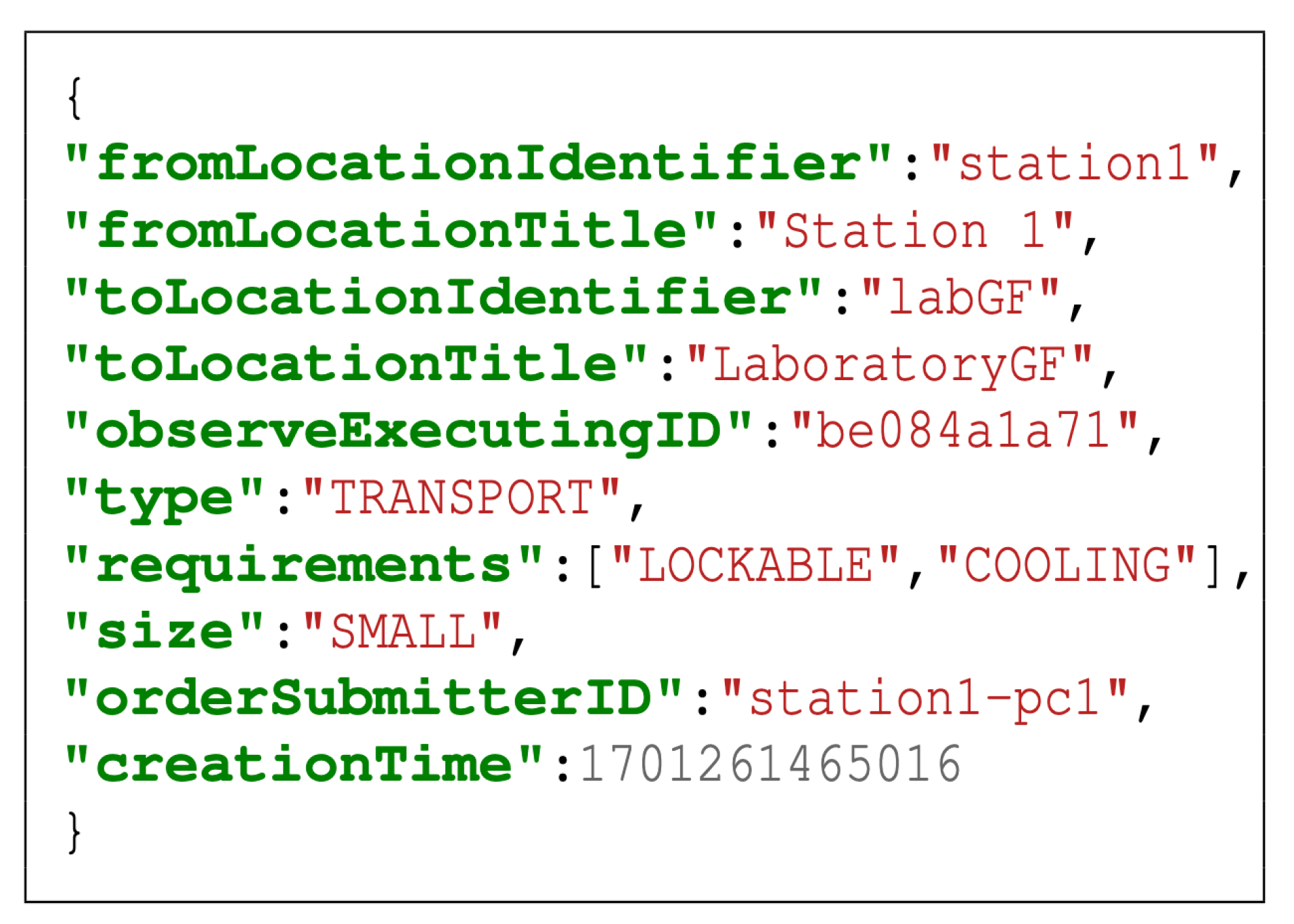

A streamlined communication flow between users and SRs has been developed in hospOS, providing an abstraction for SRs type and system integration independence. The process incorporates the system flow, ensuring a seamless interaction between HCWs and SRs, optimising task allocation and operational efficiency. After registering on the web interface, the robot communicates its available tasks, i.e. its capabilities, to hospOS. This information is stored as a task set in hospOS, making it easier to identify SRs for functions later. hospOS retrieves key information about the robot, including its status (heartbeat), battery level, IP address, stored map and current location, and forwards it to the relevant subsystem. Hospital staff can request services in various ways, including via the web interface or IoT hardware, such as a button in the ward. Requests are abstract and contain only essential information, such as the structure of a transport request. An example of a transport request is shown in

Figure 2.

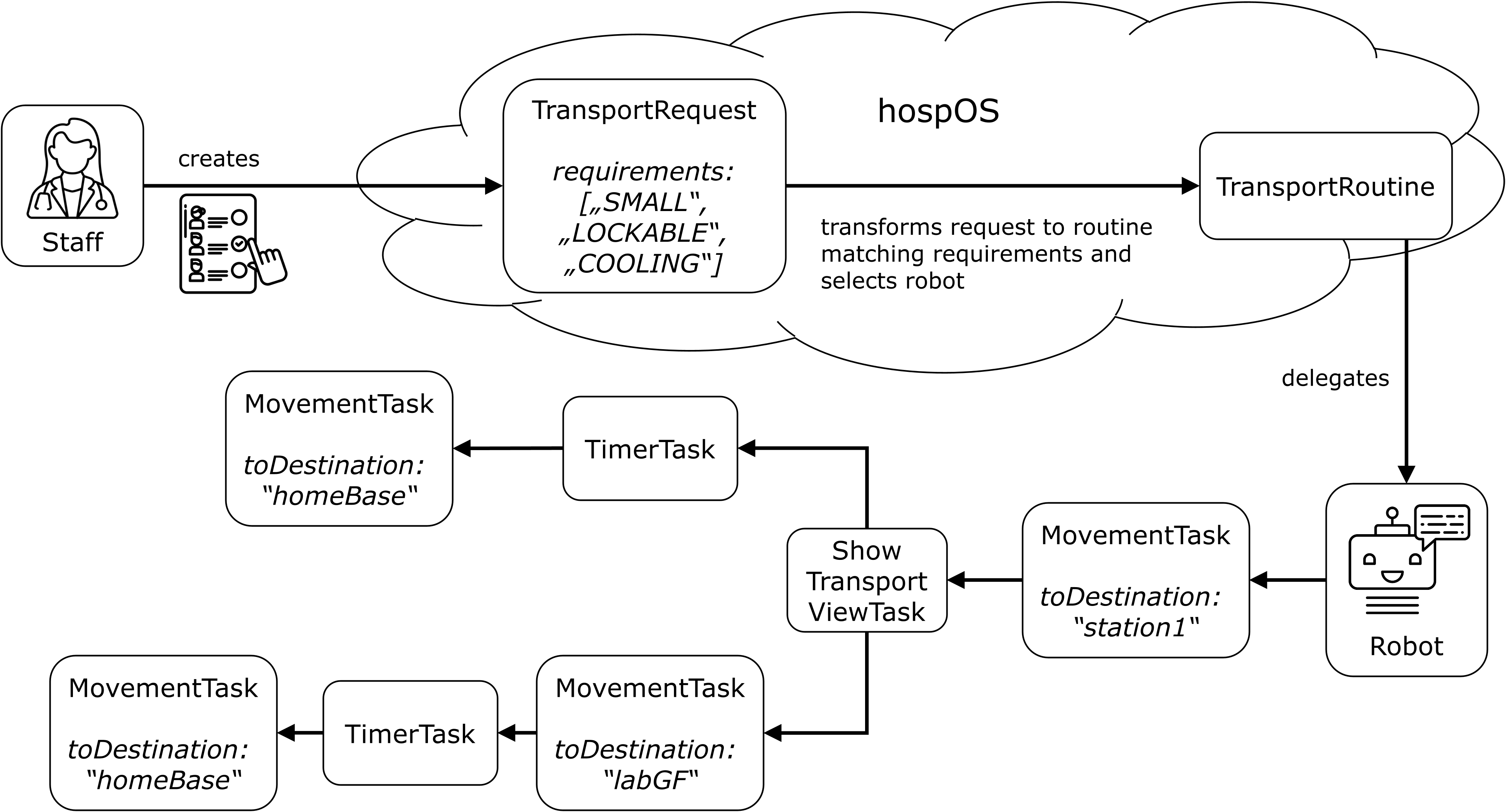

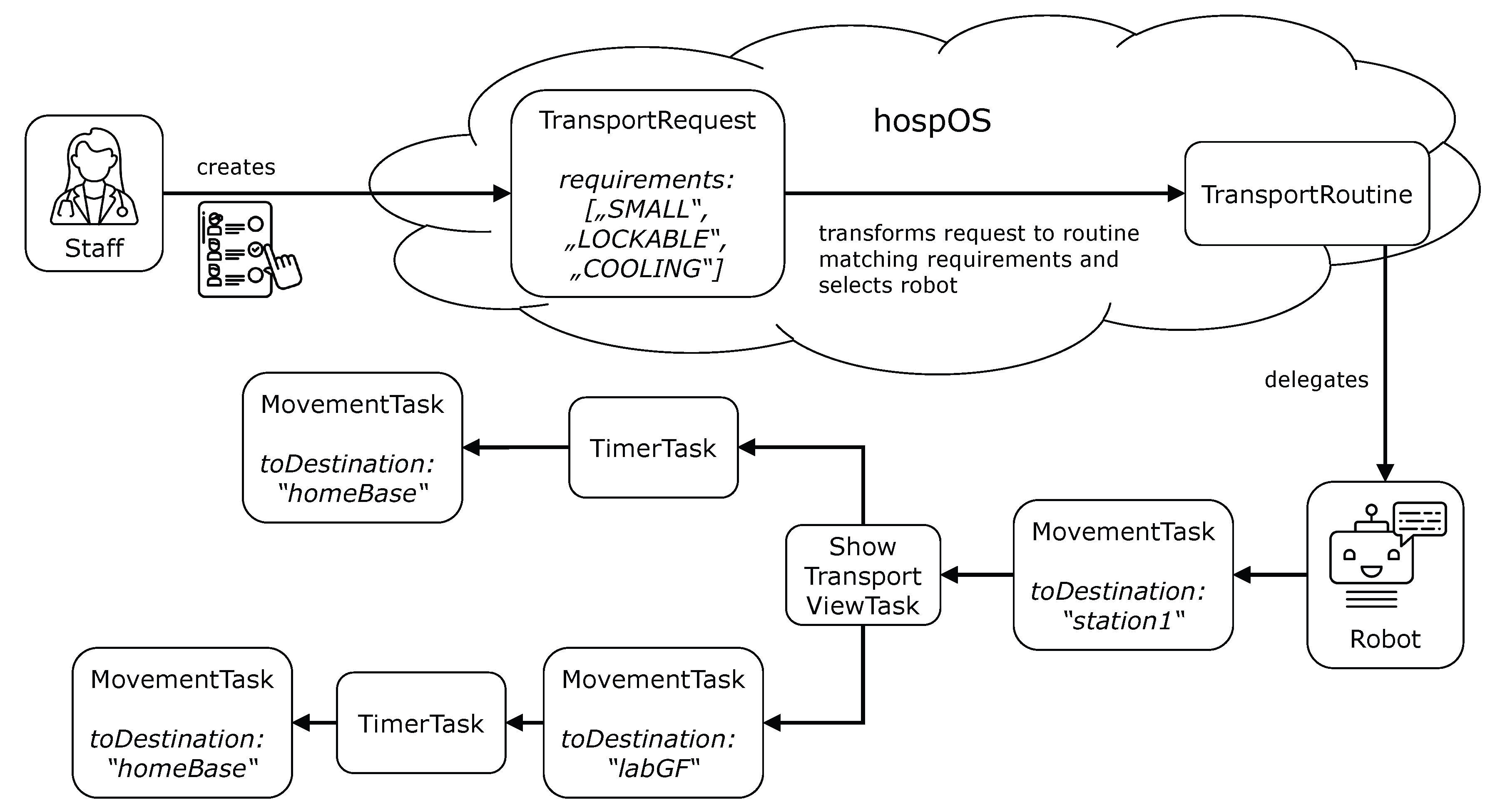

Incoming requests are translated into routines, which consist of specific tasks, as shown in

Figure 3. A routine acts as a parent class, managing a tree structure of different tasks. Tasks can range from robot functions such as

MovementTask or

ShowViewTask to

TimerTasks which simply block time. Once such a routine has been created, the task is compared with each robot’s capabilities to assign a suitable robot: One that can handle all the specific task types in the routine and is not currently engaged in another task or in an error state. A simple example is the transport of blood samples: The robots must be able to drive autonomously and store small capacities. In addition, the samples cannot be transported openly, so there is a need for a lockable tray and cooling.

The final step is to send the created routine to the selected SRs. Converted into JSON format, the routine is processed by the robot, which performs only the specified tasks, ensuring robot independence. The status of the SRs is set to doing until completion. Meanwhile, new requests can be received and processed as in the previous step, creating an operational cycle.

4.2. Common Challenges

Infrastructure Acceptance

The integration of different types of SRs presents significant challenges, particularly in the area of navigation. A key task is to merge different robot maps into a common map and to convert locations between SRs. Using the floor plan as a base, three calibration points on both the robot map and the floor plan allow for scaling and rotation alignment. This allows accurate SRs positioning and Point of Interests ( POIs) on the unified map. Another major challenge is adapting existing building doors for SRs access. The approach depends on the existing capabilities of the door: (i) For doors that open electrically (common for accessibility), a standard Shelly module conversion will suffice. (ii) Non-electrified doors require the addition of an electric motor. This cost-effective solution also integrates a Shelly, ensuring a consistent implementation across different door types.

Compliance with Regulations

To meet data protection standards, the system operates on a locally hosted solution. All systems function without internet access, requiring only a local network for SRs communication. Furthermore, CE certification, compatibility, freedom from interference, and ethical considerations should be taken into account. Although hospOS is not a medical device, it complies with the regulations of the EU MDR. This has the advantage that other products, that are medical devices, can also integrate hospOS in the long term.

Accessibility

Although patient data must be stored and processed very securely, user interfaces such as web applications must be accessible with low technical barriers. This implies the need for a sophisticated data security policy, including controlled data flow between different data endpoints.

5. Use Cases

We gathered input from doctors, HCWs and hospital managers. From their input we derived use cases and system requirements. The following three use cases were implemented in two hospitals in Bavaria, Germany, between 2021 and 2024.

5.1. Description of Use Cases

5.1.1. Use Case 1: Telemedicine

We aim to evaluate a TMed robot, building on previous results [

28]. Our hospOS approach goes beyond conventional TMed by integrating a mobile TMed robot. This innovation aims to provide economic savings and staff relief by reducing doctors’ travel time. A future study will quantify the savings for on-call physicians and evaluate the effectiveness of the TMed robot in healthcare delivery.

We will conduct a quantitative secondary analysis of hospital billing data to determine the cost savings of using a TMed robot for on-call physician services. Specifically, we plan to analyse the use of TMed robots in neurology and estimate their potential to reduce staffing and ward costs, with projections for the whole hospital.

The study will include economic benefits such as reduced travel time and associated costs, reduced material costs (particularly for TMed in isolation rooms) and reduced staff costs. We will also look at intangible benefits such as improving the attractiveness of the workplace for medical staff.

Feedback highlighted the robot’s autonomous mobility as crucial, improving flexibility and reducing nursing workload. Doctors noted the robot’s superior audiovisual quality, which improves patient communication and diagnosis. hospOS’s ability to control peripherals (external cameras, robotic arms, door openers, monitors) is an advantage, allowing customisation for specialties such as neurology and surgery. Modular camera equipment and an adaptable interface support additional functionalities such as visual animations or wound size measurements.

5.1.2. Use Case 2: Orientation

In December 2022, we conducted a seven-day observational study in a HR. Of all recorded enquiries (N=1,499), most were from visitors (51.3 %) and patients (38.5 %). Common queries included COVID-19 related questions and patient room numbers [

29]. Patients frequently asked about appointment bookings, emergency procedures and directions [

29]. Our findings suggest that SRs could handle many requests efficiently, reducing the burden on staff. To reassess information needs post-COVID, we conducted a further evaluation in November 2023, including a SRs in HR to answer FAQs. Results are expected in 2024.

5.1.3. Use Case 3: Transport

A previous study in two hospitals identified frequent, short-duration transport tasks in clinical care, particularly the transport of meals, which resulted in significant costs [

30]. In particular, the results indicate significant needs in the areas of non-medical and medical supplies, pharmacotherapy and other categories such as food and drink. Most transports had an actual transport time of less than one minute, with patient transport and laboratory samples showing greater variability. In total, 77.15% of all observed transports (N=1629) were performed manually. The use of SRs is particularly promising for the transport of meals and drinks, as the economic perspective shows a potential annual cost saving of approximately 10,000 Euro per hospital. However, a user-friendly, synergy-oriented and cost-effective robot orchestration tool such as hospOS is needed for the implementation of SRs, which facilitates efficiency.

Drawing from the study, stakeholder feedback, and discussions with robot manufacturers, we derived system requirements for transport SRs in hospitals, including the following requirements:

SRs need to be capable of navigating autonomously in hospital environments, coping with dynamic settings.

Handling of clinical goods should be efficient, with a balance between capacity and agility.

Hospitals have high hygiene standards to which SRs must adhere, e.g., SRs must withstand cleaning alcohol and be easy to clean.

Transport needs are diverse, resulting in various requirements, such as temperature and access-controlled compartments.

hospOS serves different stakeholder groups which require individual and easy-to-use interfaces, e.g., for managing transport requests and monitoring delivery status.

Based on our research, we have identified key requirements for robot-assisted orientation and wayfinding:

Use of humanoid robots: Use humanoid SRs such as Pepper for higher interaction rates.

Update Information Access: SRs should have access to an up-to-date hospital information repository.

Navigation Support: Support Pepper to coordinate with other SRs for advanced guidance tasks.

User-friendly interface: Integrate an intuitive interface, such as a touch screen, for wayfinding.

Staff Control Functionality: Allow hospital staff to easily control the robot, for example via a web application.

5.2. Quantification of Use Cases

5.2.1. Use Case 1: Telemedicine

Currently in one rural hospital, prototyping of a telemedicine (TMed) robot is ongoing and accompanied by a study from 1

th to 30

th October 2024. Typically, extensive chief physician rounds and visits take place in hospitals as part of the on-call service and in the form of consultations. The diagnosis and treatment process depends on communication between professionals and the regular assessment of the patient. Due to time lost in transit and limited specialist capacity, TMed support promises relief and monetary savings. A study showed that TMed leads to a median savings of 97.16 Euro for patients and a median carbon emission savings of 13 kg [

31]. TMed can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and travel costs can range up to 800 Euro per Patient, esp. when a patient needs to be brought to another hospital or specialist doctors need to be consulted [

32]. Especially for on-call services TMed can reduce travel times and the risk of work commute accidents as well as stress for doctors [

33].

In addition to TMed’s advantages for healthcare workers, patient outcomes also benefit. For instance, response times decrease with TMed, leading to better health outcomes and improved healthcare access [

34,

35,

36]. TMed can successfully contribute to infection protection and has some economic implications [

37,

38]. To prevent highly infectious diseases, nurses must wear personal protective equipment, including goggles, coveralls, hoods, masks, and face shields, every time they enter the isolation room. The material needs to be changed for every patient, including products that are primarily single-use and being discarded, leading to economic and environmental harm [

39]. Expenses for the protective gear, which also cannot always prevent infection, depend on the disease. For an Ebola patient, the cost is approximately 12 Euro in material cost for each dressing [

40].

5.2.2. Use Case 2: Orientation

A robot system to answer frequently asked questions in the hospital entrance area was used in 10.1 % of all 1,703 interactions that were handled in this area [

41]. Common requests included orientation in the building with 44.9 %, visiting times (26.3 %), and opening hours (20.0 %). Accordingly, the use of SRs to facilitate information in hospital robots saves 8 hours and 36 minutes per month during the study period [

41].

In this study, it was used as a supplement to the reception desk. Additional potential could be realized by covering less busy shifts or by using it outside of regular gate hours. In less busy shifts, gate staff is underutilized and therefore missing in other positions that could be more beneficial, resulting in inefficiency and avoidable costs for the hospital. Outside of regular gate hours, e.g. at night, orientation questions are directed towards the next staff members available, which often happen to be nurses whose shifts are thinly staffed already. Considering the general shortage of skilled nursing staff and the tense financial situation of hospitals, using robots in off-peak hours is a valuable lever for realizing potential that needs further examination.

Additionally to the information service alone, a robot guidance service has provided time savings for hospital workers and proven to be economically beneficial for the institution. The physical robot capable of autonomous navigation guided people from the entrance hall to their hospital destination in 41 cases within a week or 178 cases per month. In addition, the guidance service is now also used for in-house routes, e.g. to guide patients from the ambulance to the X-ray department or from the on-call service to the stationary admission. The hospital benefits not only from the time and physical effort saved by hospital staff not having to walk patients to their destinations. Moreover, also the fact that the hospital reception would be temporarily unmanned can be avoided and therefore queues and the necessity of delegating a second person to answer information requests.

5.2.3. Use Case 3: Transport

5.2.3.1. Previous Study Results

A previous study showed that in a period of seven days, a total of 1,025 transports took place in a geriatric ward in Viechtach (VIT) with one nurse being observed [

30]. The observations took place on both of the day shifts, not on the night shift. Of all recorded transports, ten were laboratory sample transports [

30]. Extrapolated to one month, this results in 44 transports based on one nurse. Assuming the nursing staff consists of four people, this corresponds to 176 transports of laboratory samples within one month.

5.2.3.2. Robot Log Data

A transport robot is currently used in VIT to take laboratory samples from a ward to the laboratory. According to the robot log data recorded from 20th June to 14th August, 2024, which consists of 55 days, the robot was used for transports between the laboratory and the ward 257 times, traveling a total of 18 hours and 20 minutes during the log period. Considering the average for one month, the robot completed 142 transport routines between the ward and the laboratory, averaging 4.67 transports per day. The pure traveling time consists of 10 hours and 7 minutes per month or 20 minutes per day.

Another transport robot is currently being used at a trauma surgery ward in the hospital in FRG. The robot is used as a mobile service kitchen to shorten the nurses’ necessary routes. It delivers fresh water, coffee, and tea to defined points of interest, from where the staff brings the goods to the patients’ rooms. The recorded data covers 85 days from 27th May to 20th August, 2024. In this period of time, the robot was sent 567 times to a specific location, averaging 203 transports per month or 6.67 per day. The robot traveled a total of 17 hours and 18 minutes during the log period. Considering the average for one month, the robot is used for 203 transports, which corresponds to a pure traveling time of 6 hours and 15 minutes per month or 12 minutes per day.

5.2.3.3. Comparison of Study Data and Robot Logs

Based on the extrapolated study data of VIT, approximately 176 transports of laboratory samples were carried out by the nursing staff, and the robot handled 142 transports within one month. The robot currently fulfills around 80.68 % of laboratory sample transports in VIT. The use of a robot could have led to more individual transports, as a nurse may only take the walk to the laboratory for a larger number of samples in order to minimize the effort and time required. Nonetheless, general technology acceptance and adaption of the process can be assumed based on the data and the nurses’ feedback.

The current robot log data from FRG cannot be used for comparison with data from the previous study, as the transport of water, coffee, and tea is not exclusively included. It is a subset in the study category ’Meals or Drinks’, where the transport of the three main meals breakfast, lunch, and dinner dominates.

5.2.3.4. Extrapolation for All Transported Goods

In principle, a robot can perform all transport tasks that occur in a hospital ward, given physical feasibility. Of the 1,830 transports recorded from both hospitals, which were divided into ten categories, SRs can handle the transportation of goods from the categories of non-medical consumables, medical consumables, meals or drinks, documents, and laboratory samples without further adjustment. Due to regulatory and safety restrictions, objects belonging to pharmacotherapy cannot be transported by robots without further measures. However, as it is a regulatory issue only, it should be possible in the future. Thus, SRs can take over five of the ten categories without adaptation, which corresponds to a lower limit of 1,129 transports. With an adaptation, it would be six categories, which corresponds to an upper limit of 1,387 transports (see

Table 1). Considering the time savings potential of laboratory samples, the robot currently takes over 80.68 % of all recorded transports, which means that, based on the study data, it can save 912 to 1,120 transports. This corresponds to a total time savings potential between 49.84 % and 61.20 % for all transported goods in a hospital ward through SRs.

6. Discussion

hospOS addresses the predicted shortage of nurses by 2030 by digitising hospital processes. It offers cost savings and improved quality of care, in line with market trends driven by an ageing population and increasing healthcare demands. Its vendor-independent, versatile system reduces the IT burden on hospitals and addresses specific clinical needs, with scalability potential through its software.

Integrated robot orchestration systems are essential in complex healthcare environments to monitor robot activities [

10,

18,

42]. The need for smart hospitals highlights the lack of interfaces in SRs, exacerbated by economic constraints and staff shortages. The lack of interoperability in robotic solutions limits the potential [

25]. Research gaps exist in robot-robot interaction and human-robot collaboration [

20]. Regulatory compliance, such as CE certification, is critical.

The use of SRs in healthcare is expected to increase over the next decade, emphasising the importance of hospOS [

15]. Investment in user-friendly SRs management solutions is crucial [

11]. The German hospital reform does not currently address the potential of SRs to address staffing issues. Financial support for SRs and standardised frameworks, such as the HL7 standard for device interfaces, are needed for integration into cross-device platforms [

25].

The potential of hospOS has multiple positive effects, also on employee health. By efficient utilization of transport robots, hospital workers experience fewer physical demands. Intelligent coordination of different robots reduces the organizational effort and stress of robot usage for the staff.

Acquiring and implementing new technology as well as changing processes come with costs for hospitals. Especially in the light of many hospitals facing a tense financial situation, decisions are made based on economic considerations. While economic benefits via hospOS in the telemedicine use case can not be quantified yet, the potential can be derived in orientation and transport use cases.

A humanoid robot reduced the workload of gate staff by answering orientation questions for 8 hours and 36 minutes per month. In addition, the robot guidance service is capable of taking over 176 accompanying walks per month. Without any adjustments, service robots can create a time savings potential between 49.84 % and 61.20 % of all transport tasks of a ward in a rural hospital. Log data shows that the adoption of robot transports in hospital processes is taking place already, as a robot currently fulfills around 80.68 % of laboratory sample transports, resulting in a travel time of 10 hours and 7 minutes per month.

Some limitations in the data analysis remain: During the transport study, only a limited number of nurses were observed for one week. The study included day shifts, but excluded night shifts. While it seems reliable, there could be a bias in the data, as some nurses might take over more transport tasks than others. Our transport study and the log data analysis both only cover a limited time frame. The transport study observed two periods of 7 days, the log data used in this study covers 55 and 85 days. To eliminate seasonal factors, further research should be done based on data from longer periods.

The comparison of the transport study’s results and current robot log data in this study only cover one small portion of all transport tasks in the hospitals, in detail only sample transports in VIT. More log data is available, but not yet sufficient for meaningful extrapolations and statements. For example, currently log data from FRG cannot be used for comparison, as the transport only covers a subset of the category ’Meals or Drinks’. Furthermore, the installment of the robot in FRG is yet only used to create a first touchpoint and thus increase the staff’s familiarity with transport robots. Therefore, in this phase, it was not yet connected to a concrete time savings target, nor accompanied by process adaption and change management. The ward’s nursing staff were given the option to contemplate a use case they wanted to try out and created the idea of the mobile service kitchen. This limits the potential for time savings, as the robot does not take over any main transport processes. An extensive and accompanied integration into the process of meal delivery will take place in the fall of 2024, creating the possibility for further data comparison and research.

Additionally, the logs in total originate from only two hospitals with similar sizes from lower Bavaria. For a better understanding, more hospitals with different profiles should be included. To do so, hospOS should be installed in more hospitals.

hospOS can operate electrified hospital doors that are mainly used in hospital hallways, but most patient rooms are not equipped with electrified doors. For transports to and from patient rooms, this means that robots can only drive in the hallways and to the door, but not into the room. While a large part of the transport is done by the robot, a nurse is required for opening the door for the robot or finishing the delivery. For maximum time savings, these tasks should be avoided. Further research should focus on whether this can be solved e.g., by patients opening the door themselves after receiving a notification, if they are physically able to do so.

Finally, it should be considered that processes optimized and adapted to being done by robots will differ from the old ones without a robot. When collecting data from an optimized system, maximizing the time savings, these differences have to be taken into consideration when comparing data in further studies.

7. Conclusion

We presented hospOS, a platform for orchestrating service robots in healthcare facilities. Our approach addresses key challenges in healthcare robotics, including integration complexity, interoperability and stakeholder-specific user interfaces.

By providing a centralised, modular and adaptable orchestration system, hospOS bridges the gap between different robot functions and the existing hospital IT infrastructure. The platform’s focus on user-centricity and compliance with local regulations, such as GDPR, makes it a viable solution for SRs integration in healthcare facilities.

Our ongoing evaluation of hospOS for the three use cases TMeds, transport, and orientation has demonstrated its potential to improve operational efficiency, patient safety, and staff workload. While the telemedicine use case can not be quantified yet, this study derived quantifiable outcomes for orientation and transport.

hospOS was able to reduce the workload by answering orientation questions for 8 hours and 36 minutes and taking over 176 accompanying walks per month with the orchestrated use of a humanoid and an autonomously driving guidance robot. Further potential lies in using robots for orientation services in less busy shifts or outside of regular gate hours as a substitution instead of using it as a supplement.

By orchestrating laboratory sample transports, hospOS assisted nurses in a rural hospital with a traveling time of 10 hours and 7 minutes per month for these transports. Transportation of laboratory samples is just a small portion of transportation tasks in a hospital. The potential of extending the use case to adoptable categories of all transport tasks of a ward in a rural hospital is even bigger. Without any adjustments, it results in a time savings potential of 49.84 %. With adjustments due to regulatory and safety restrictions regarding pharmacotherapy objects, the number increases to 61.20 %. Log data shows that the adoption of robot transports in hospital processes is taking place already, as a robot currently fulfills around 80.68 % of laboratory sample transports in a rural hospital, resulting in a reduced workload of nurses by a travel time of 10 hours and 7 minutes per month for transportation of these samples.

8. Future Work

Future work will focus on emphasizing the quantification of time savings and economic benefit in the three introduced use cases. After rolling out the telemedicine use case in the hospitals, its potential needs to be examined. For a better understanding of the time savings potential in the orientation use case, additional research should be conducted using hospOS and SRs as a substitute instead of a supplement. For a deeper analysis of the time savings potential in the transportation use case, remaining transport use cases need to be investigated. It should be examined how many transports are still done by walking, and how the number and frequency of transports might have changed by adding the possibility of robot transports. Thus, as robots’ traveling speed and nurses’ walking speed differ, the time and effort saved by reducing the transports done by nurses should be further evaluated.

Future work will focus on improving the functional and non-functional aspects of the use cases. Regarding TMeds, functionalities for special requirements in medical fields such as geriatrics and surgery will be extended. For example, wound measurements or vital data from the processed video stream can be made available to the doctor. In the case of transport, the focus will be on integrating more and different robot models. The system will therefore be able to choose from a wider range of available SRs according to the requirements of the request, e.g. transport with cooling, locking or the need for a larger storage area. Both the orientation SRs and the web application interfaces will benefit from further iterations of usability testing and engineering, adapting the user interfaces as best as possible to the needs of the defined stakeholder groups.

In terms of non-functional aspects, the focus is on improving regulatory compliance. As hospOS replaces analogue processes, it is built as a redundant service layer without integrating critical paths (e.g. emergency alarm implementations). There are no plans to use hospOS to replace certified security systems or to add security critical dependencies to hospOS. However, in a hospital environment, hospOS and its connected robots must follow predictable behaviour patterns even in the case of complete or partial system failure, e.g. robots must not block corridors in case of system failure. To achieve this, we implement hierarchical error handling strategies. At the technical protocol level, we will use the MQTT last will feature to ensure predictable behaviour even in the case of a lost connection. For example, a robot should move to an area where it will not interfere with other processes in the hospital - e.g. its home base or the side of the corridor in the event of a system failure.

Acknowledgments

We thank our hospital partners, the Kliniken am Goldenen Steig gGmbH, Freyung and Arberlandklinik Viechtach for their cooperation. The German Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport supported this research under grant No. 45FGU120.

This extended paper builds upon previously approved studies conducted within the Smart Forest – 5G Clinics research framework. All studies complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guidelines for Safeguarding Good Research Practice (DFG). Ethical approval and assessments were obtained from the Joint Ethics Committee of the Bavarian Universities of Applied Sciences (GEHBa) under the reference number GEHBa-202309-V-128. In addition, the procedures were reviewed and approved by the respective hospital ethics committees and the data protection management of the university. All underlying studies ensured informed consent, voluntary participation, and strict data confidentiality. The present extended paper involves no new studies with human participants, no additional data collection, and therefore required no further ethical approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Parliament, E. Demographic outlook for the european union 2022: Think Tank, 2022.

- Lützerath, J.; Bleier, H.; Schaller, A. Work-Related Health Burdens of Nurses in Germany: A Qualitative Interview Study in Different Care Settings. Healthcare 2022, 10, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, V.; Papazova, I.; Thoma, A.; Kunz, M.; Falkai, P.; Schneider-Axmann, T.; Hierundar, A.; Wagner, E.; Hasan, A. Subjective burden and perspectives of German healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience 2021, 271, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroczek, M.; Späth, J. The attractiveness of jobs in the German care sector: results of a factorial survey. The European Journal of Health Economics 2022, 23, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, J.; Vu-Eickmann, P.; Li, J.; Müller, A.; Wilm, S.; Angerer, P.; Loerbroks, A. Desired improvements of working conditions among medical assistants in Germany: a cross-sectional study. Journal of occupational medicine and toxicology (London, England) 2019, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2023; OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing: Paris, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, D.; Wilhelm, S.; Wahl, F. Nurses’ Workplace Perceptions in Southern Germany—Job Satisfaction and Self-Intended Retention towards Nursing. Healthcare 2024, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köppen, J.; Busse, R. Die Personalsituation im Krankenhaus im Internat..ionalen Vergleich. In Krankenhaus-Report 2023; Klauber, J., Wasem, J., Beivers, A., Mostert, C., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2023; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Gu, D.; Klein, R.; Zhou, S.; Shih, Y.C.T.; Tracy, T.; Soybel, D.; Dillon, P. Factors Associated With Hospital Decisions to Purchase Robotic Surgical Systems. MDM policy & practice 2020, 5, 2381468320904364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.; Kingston, L.; McCarthy, C.; Armstrong, E.; O’Dwyer, P.; Merz, F.; McConnell, M. Service Robots in the Healthcare Sector. Robotics 2021, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf, N.; Sidaoui, A.; Elhajj, I.H.; Asmar, D. Robotics in Nursing: A Scoping Review. Journal of nursing scholarship:an official publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing 2018, 50, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; An, S.; Lee, H.Y.; Cha, W.C.; Kim, S.; Cho, M.; Kong, H.J. Review of Smart Hospital Services in Real Healthcare Environments. Healthcare Informatics Research 2022, 28, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, G.; König, A.S.L. Robotic devices and ICT in long-term care in Japan: Their potential and limitations from a workplace perspective. Contemporary Japan 2021, 35, 270–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimpel, H.; Schröder, J.; Baier, M.S.; Heger, S.; Hufnagl, C.; Kriner, H.; Wöhl, M. Krankenhaus-Report 2023. In Hospital 4.0; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2021; pp. 179–195. [CrossRef]

- Asgharian, P.; Panchea, A.M.; Ferland, F. A Review on the Use of Mobile Service Robots in Elderly Care. Robotics 2022, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra Marín, S.D.; Gomez-Vargas, D.; Céspedes, N.; Múnera, M.; Roberti, F.; Barria, P.; Ramamoorthy, S.; Becker, M.; Carelli, R.; Cifuentes, C.A. Expectations and Perceptions of Healthcare Professionals for Robot Deployment in Hospital Environments During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2021, 8, 612746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radic, M.; Vosen, A.; Graf, B. Use of Robotics in the German Healthcare Sector. In Social Robotics; Salichs, M.A., Ge, S.S., Barakova, E.I., Cabibihan, J.J., Wagner, A.R., Castro-González, Á., He, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Li, H.; Suomi, R.; Li, C.; Peltoniemi, T. Intelligent Physical Robots in Health Care: Systematic Literature Review. Journal of medical Internet research 2023, 25, e39786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Strüber, D.; Brugali, D.; Di Fava, A.; Pelliccione, P.; Berger, T. Software variability in service robotics. Empirical Software Engineering 2023, 28, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.F.N.; Christou, A.; Stouraitis, T.; Gienger, M.; Vijayakumar, S. Adaptive assistive robotics: a framework for triadic collaboration between humans and robots. Royal Society open science 2023, 10, 221617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnack, H.; Uthoff, S.A.K.; Ansmann, L. The perceived impact of physician shortages on human resource strategies in German hospitals - a resource dependency perspective. Journal of health organization and management 2022, 36, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Sommer, D.; Greiler, T.; Wahl, F. hospOS: A Platform for Service Robot Orchestration in Hospitals. In Proceedings of the ICT4AWE; 2024; pp. 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Min Ho Lee.; H. Ahn.; B. MacDonald. A Case Study: Robot Manager for Multi-Robot Systems with Heterogeneous Component-based Frameworks. CARES University of Auckland.

- Morgan, A.A.; Abdi, J.; Syed, M.A.Q.; Kohen, G.E.; Barlow, P.; Vizcaychipi, M.P. Robots in Healthcare: a Scoping Review. Current robotics reports 2022, 3, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Veiga, T.; Chandler, J.H.; Lloyd, P.; Pittiglio, G.; Wilkinson, N.J.; Hoshiar, A.K.; Harris, R.A.; Valdastri, P. Challenges of continuum robots in clinical context: a review. Progress in Biomedical Engineering 2020, 2, 032003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturkcan, S.; Merdin-Uygur, E. Humanoid service robots: The future of healthcare? Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases 2022, 12, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammenwerth, E. Technology acceptance models in health informatics: TAM and UTAUT. Stud Health Technol Inform 2019, 263, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, D.; Wilhelm, S.; Ahrens, D.; Wahl, F. Implementing an Intersectoral Telemedicine Network in Rural Areas: Evaluation from the Point of View of Telemedicine Users. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, D.; Greiler, T.; Fischer, S.; Wilhelm, S.; Hanninger, L.M.; Wahl, F. Investigating User Requirements: A Participant Observation Study to Define the Information Needs at a Hospital Reception. In HCI Internat..ional 2023; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Ntoa, S., Salvendy, G., Eds.; Springer Internat..ional Publishing AG: Cham, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, D.; Kasbauer, J.; Jakob, D.; Schmidt, S.; Wahl, F. Potential of Assistive Robots in Clinical Nursing: An Observational Study of Nurses’ Transportation Tasks in Rural Clinics of Bavaria, Germany. Nursing Reports 2024, 14, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papavero, S.C.; Fracasso, A.; Ramaglia, P.; Cicchetti, A.; de Belvis, A.D.; Ferrara, F. Telemedicine Has a Social Impact: An Italian National Study for the Evaluation of the Cost-Opportunity for Patients and Caregivers and the Measurement of Carbon Emission Savings. Telemedicine journal and e-health : the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association 2023. [CrossRef]

- Donald, N.; Irukulla, S. Greenhouse Gas Emission Savings in Relation to Telemedicine and Associated Patient Benefits: A Systematic Review. Telemedicine journal and e-health : the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association 2022. [CrossRef]

- Heponiemi, T.; Presseau, J.; Elovainio, M. On-call work and physicians’ turnover intention: the moderating effect of job strain. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2015, 21, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lv, H.; Lu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wu, H.; Xiong, J.; Yang, G. A Medical Assistive Robot for Telehealth Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Development and Usability Study in an Isolation Ward. JMIR human factors 2023, 10, e42870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, N.; Hai, X.; Huu, L.; Nam, T.; Thinh, N.T. Remote Healthcare for the Elderly, Patients by Tele-Presence Robot. 2019 International Conference on System Science and Engineering (ICSSE) 2019, pp. 506–510. [CrossRef]

- Teng, R.; Ding, Y.; See, K. Use of Robots in Critical Care: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaeinili, N.; Vilendrer, S.; Williamson, E.; Zhao, Z.; Brown-Johnson, C.; Asch, S.M.; Shieh, L. Inpatient Telemedicine Implementation as an Infection Control Response to COVID-19: Qualitative Process Evaluation Study. JMIR Formative Research 2021, 5, e26452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Wan, F.; Jin, A. Is telemedicine worth the effort? A study on the impact of effort cost on healthcare platform with heterogeneous preferences. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2024, 188, 109854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeek, J.H.; Rajamaki, B.; Ijaz, S.; Sauni, R.; Toomey, E.; Blackwood, B.; Tikka, C.; Ruotsalainen, J.H.; Kilinc Balci, F.S. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolas, T.; Werner, K.; Alkenbrack, S.; Uribe, M.V.; Wang, M.; Risko, N. The economic value of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers. PLOS Global Public Health 2023, 3, e0002043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, D.; Fischer, S.; Wahl, F. Investigating Hospital Service Robots: A Observation Study About Relieving Information Needs at the Hospital Reception. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Springer; 2024; pp. 395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ragno, L.; Borboni, A.; Vannetti, F.; Amici, C.; Cusano, N. Application of Social Robots in Healthcare: Review on Characteristics, Requirements, Technical Solutions. Sensors 2023, 23, 6820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).