1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most diagnosed cancer in men, with approximately 1.4 million new cases per year[

1]. One possible treatment for PCa is radical prostatectomy (RP), a surgical procedure involving the complete removal of prostate tissue. Following RP, Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) serum level is monitored over time to detect disease relapse. PSA is a secreted protein with a molecular weight of 33 kDa, expressed in both normal and cancerous prostatic tissue, and should not be present in blood after total prostate resection. However, the presence of residual tumour margins after surgery can lead to a cancer relapse with a progressive increase in serum PSA level. When PSA levels rise above 0.2 ng/ml (6 pM, the current critical threshold) in two consecutive measurements, the patient is said to present a biochemical recurrence (BCR), highly indicative of tumour relapse. Using this threshold (defined also as nadir point[

2]), approximately 23% of patients experience BCR within five years after surgery.

The development of novel ultrasensitive PSA assays (USPSA), defined as assays with a limit of detection (LoD) below 1 pM[

3], has significantly improved the ability to detect early rises in PSA levels. This advancement enables earlier BCR detection following RP, allowing for improved patient management. Furthermore, the introduction of USPSAs has led to the proposal of alternative nadir points, such as 300 fM[

4] and 150 fM[

5]. However, USPSAs available in clinicals settings still have limitations, including the need for specialised laboratories, high costs, and lack of standardization across different platforms, leading to variability in the results. In parallel, the development of commercial point of care (PoC) PSA tests based on gold nanoparticles, such as Lateral Flow Assays (LFA)-based ones, has provided portable, easy-to-use, non-invasive assays that deliver rapid results. However, these tests suffer from a higher LoD range of 9 pM – 3 nM.[

6]

In this context, there is a growing interest for the development of more sensitive assays, including portable ones. Gold nanoparticle-based systems offer excellent optical properties and biocompatibility, making them well-suited for this purpose. Additionally, innovative nanoparticle-based strategies for diagnostic and prognostic applications are paving the way for

in vivo use of triggerable nanostructured systems with an ex vivo readout: upon disassembly of these systems injected in living organisms, renal-clearable reporters are released, and these can be rapidly quantified in urine[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. This approach has proven highly effective in enabling earlier cancer diagnoses compared to traditional

in vitro assays, due to an increased tumour environment accessibility and a longer retention. Various platforms have been explored for this purpose, including polymeric nanoparticles (NPs), fluorescent probes, and inorganic NPs. Among them, inorganic-NPs-based systems, particularly the ones using metal nanoparticles (MNPs), offers notable advantages. These systems can be designed as larger nanostructures (typically 100–200 nm) to exploit the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect for (targeted) accumulation in diseased tissues. Subsequently, they can release ultrasmall nanoparticles with a hydrodynamic diameter (HD) <6 nm, which are efficiently cleared through the kidneys via rapid renal excretion. These systems typically exploit enzymatic biomarkers such as metalloproteinases or β-glucuronidases, which are overexpressed in tumours. However, to our knowledge, no studies have focused in targeting specific protein biomarkers.

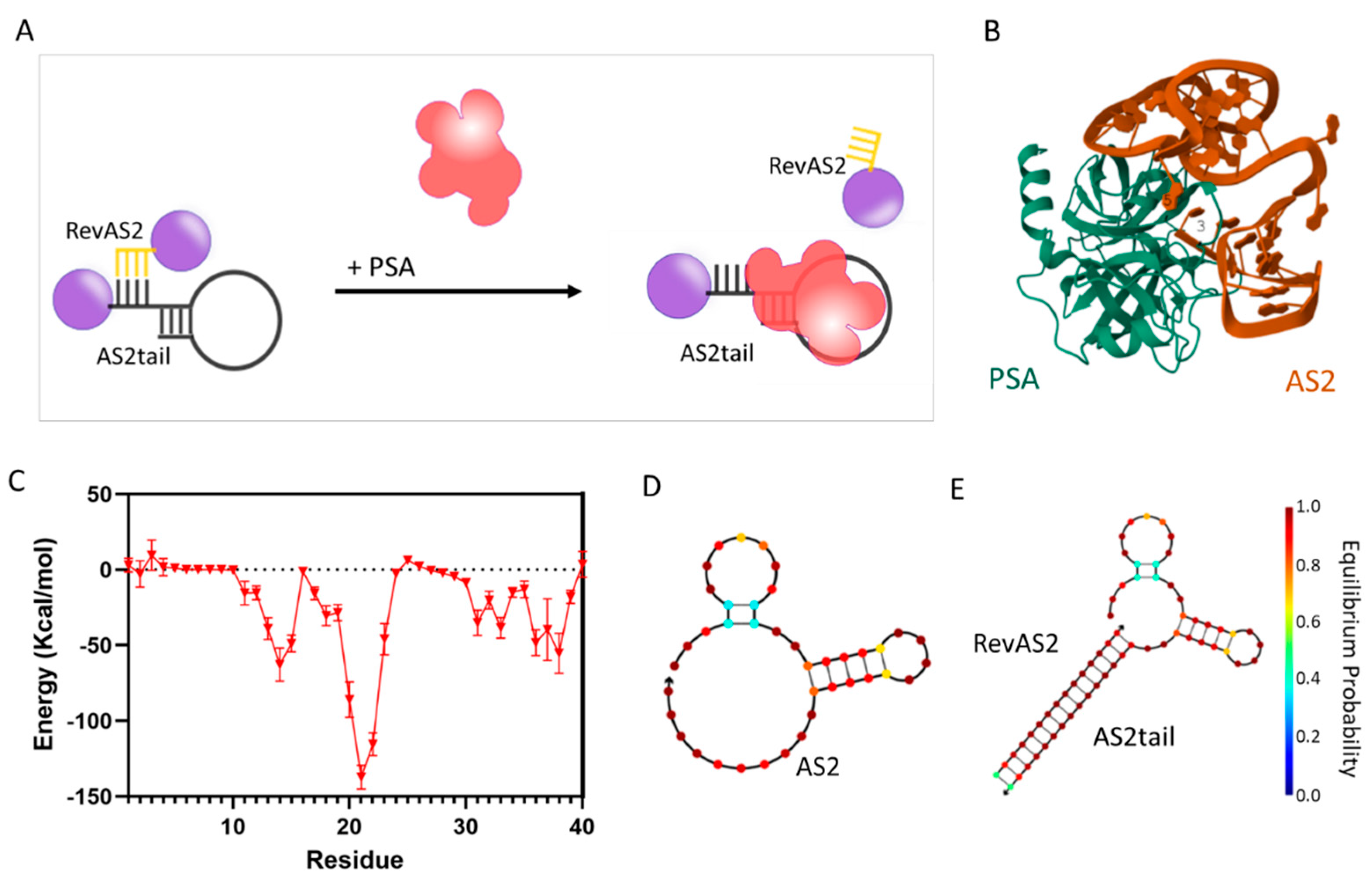

In this study, we present an activatable aptamer-nanoparticle-based structure responsive to PSA, named AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate, composed of aggregated ultrasmall gold nanoparticles (US-AuNPs), with a size suitable for renal clearance. This system is based on a switchable nucleotide architecture composed by two (partially) complementary sequences attached to, and linking together, the US-AuNPs; one of these oligonucleotides incorporates an aptamer specific for PSA. Upon biomarker recognition, the system releases, or is disassembled into, single US-AuNPs. The nanostructure development was initiated by designing switchable sequences through an in-silico approach. Moreover, we evaluated the stability of the AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate nanostructure in the presence of blood components to assess its potential for in vivo application. This step is crucial, as physiological fluids such as plasma contain biomolecules that may compromise nanostructure properties. By investigating the behaviour of the system in these complex conditions, we aimed to evaluate its functionality in biologically relevant environments, thus providing key insights into its suitability for translational applications in real-time, non-invasive diagnostics.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials and Instrumentation. Nucleotidic and aptameric sequences were purchased from Metabion (Germany). The Native Human Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). Fluorophores used for ssDNA functionalisation were the following: NHS-Rhodamine (5/6-carboxy-tetramethyl-rhodamine succinimidyl ester; Thermo Scientific™) and Atto580Q-NHS-ester (ATTO-TEC). DNase I Solution used for nucleases stability experiments was purchased by Thermo Scientific™. Human Plasma was obtained from Biowest and Human Female Plasma from Aurogene. Chemicals used in this study were the following: Gold(III) chloride trihydrate, Sodium Borohydride, Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB), all from Sigma-Aldrich®. For ELONA assays we used Corstar® 96 well assay flat bottom plate (Corning), colorimetric readings were performed with the Infinite ® PRO 200 (TECAN) instrument. DLS (Malvern Panalytical, Zetasizer Nano ZS) and UV-Vis spectra (Agilent, Cary 3500 UV-Vis) were used for nanostructures characterisation. DLS was set with PBS as solvent and gold as material of the nanoparticles. DLS for Zeta potential measurements were set in automatic mode. All measurements were done with a backscatter measurement angle =137°.

Enzyme-linked Oligonucleotide Assay (ELONA). The aPSA[

14], AS2[

15] and As2-tail sequences were tested with ELONA. A 96-well Assay plate was incubated with 250 ng of PSA (diluted in 100 μl of 0.1 M NaHCO

3 pH 9.6 buffer) at 37 °C for one hour with agitation. The PSA solution was removed, and, without additional washing, incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with 200 μl of Blocking Solution (BSA 3% + 100 nM of an equimolar mixture of the coating ssDNA sequences hlyQF, hlyQR, L23SQF, L23SQR)[

27]. Blocking Solution was removed, without additional washing. 100 μl of folded biotinylated-sequences (aPSA-biotin; AS2tail-biotin and annealed AS2tail-biotin:RevAS2) were prepared in 1:2 serial dilutions in PBS buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgCl

2, ranging from 500 nM to 3.9 nM, and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with gentle shaking. The solution was removed and washed once with 200 μl of Washing Solution (PBS Tween-20 0.05% (v/v)). 100 μl of the enzyme conjugation solution (HRP-streptavidin diluted 1:20,000 in PBS BSA 1%) were added and incubated for 1 hour with gentle shaking at room temperature. The enzyme-conjugation solution was removed, and washed six times with 200 μl of Washing Solution. 100 μl of 5,5´-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) solution was added, the plate was incubated from 3 to 20 minutes, until the solution started to turn blue, at which point 100 μl of TMB stop solution (0.16M sulphuric acid) were added. Absorbance values were read at 450 nm, and the response curve was generated after applying blank correction (samples without aptamer).

Switchable nucleotide-sequences development. The

in silico protocol applied to investigate the interaction of the AS2 aptamer and PSA was developed in a previous work[

17]. This protocol was used to predict which nucleotides of the aptamer contact PSA and to estimate their respective energy contributions to the binding interaction. Briefly, after obtaining the 3D structure of the aptamer we performed a flexible docking interaction and post-docking analysis between the aptamer and the target protein. The crystallographic structure of the PSA protein used for the simulation corresponds to the PDB code 2ZCK. The NUPACK online tool (NUPACK3 version, [

28]) was used to predict the secondary folding and thermal stability of these sequences [

29,

30]. Thermal stability was calculated between 30 and 70 °C using a saline concentration of 150 mM of NaCl and 25 mM of Mg

++.

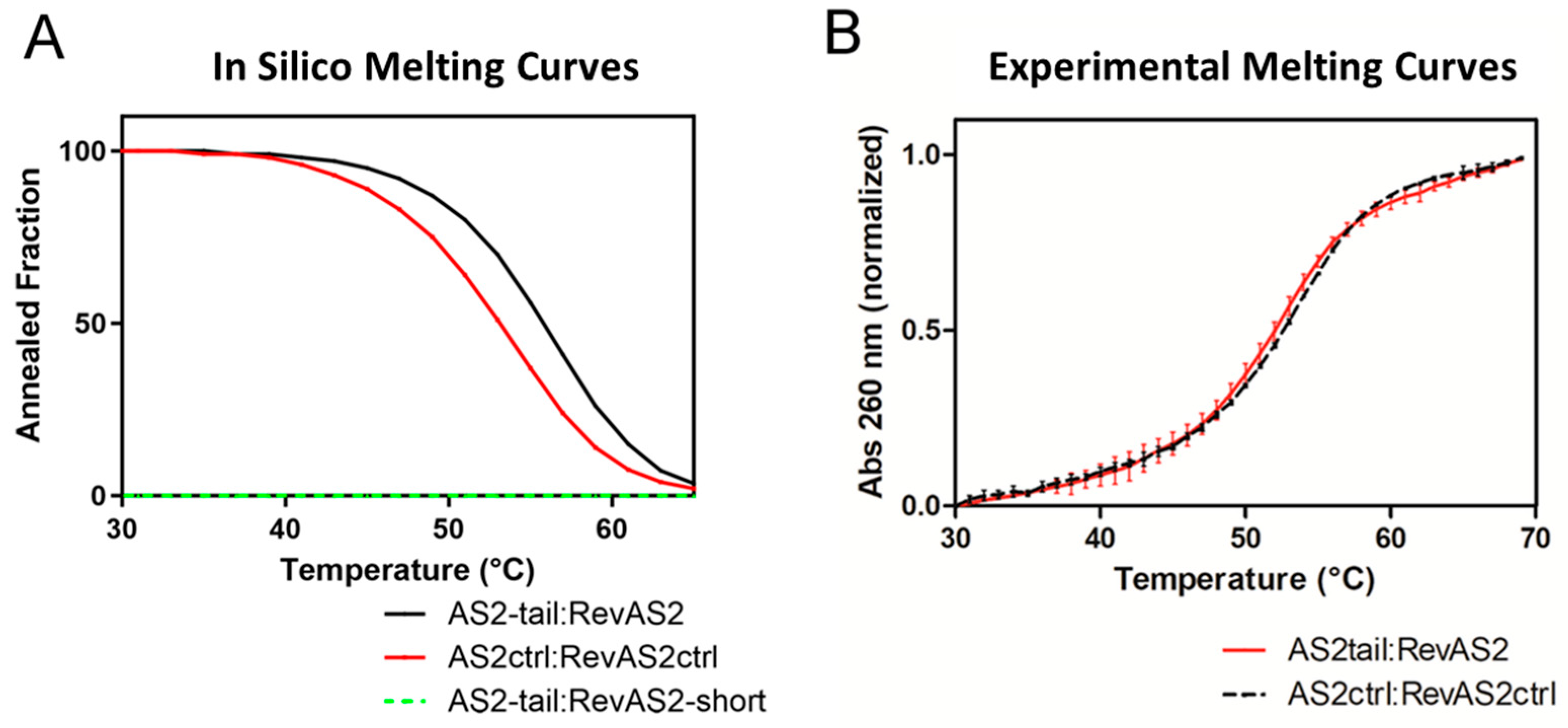

In silico melting temperatures (T

m) of the complexes were estimated using a nucleotide concentration of 100 nM and T

m was calculated as the temperature at which the concentration of the AS2 and Control duplexes lowered to 50 nM. Melting temperatures of AS2-tail:RevAS2 and AS2tail-ctrl:RevAS2-ctrl were measured by performing absorbance reading at 260 nm. Firstly, sequences were annealed in Annealing Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM MgCl

2) at a concentration of 100 nM with the following thermal steps: 2 minutes at 95 °C and then the solution was cooled down at 12 °C with a temperature ramp of -2 °C/min. For melting curve recording, absorbance values of the annealed DNAs solutions were recorded at 260 nm from 25 to 75 °C, with temperature steps dT of 1°C and with a temperature rate of +2°C/min. For

in vitro analysis, melting temperature of the annealed sequences was determined as the one at the maximum value of the first derivative of the absorbance (A) with respect to the temperature (T) of the recorded melting curve (dA/dT).

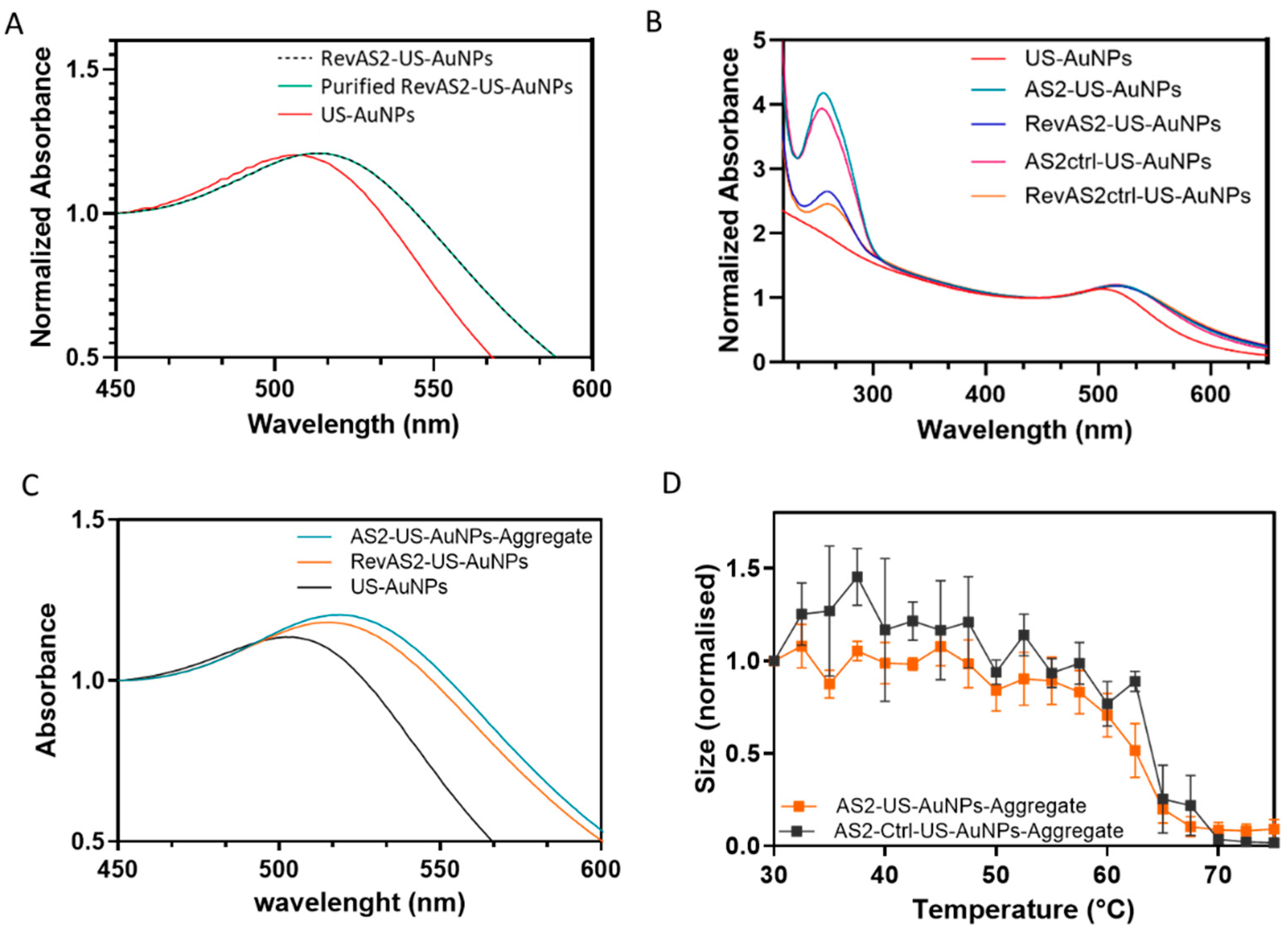

US-AuNPs synthesis and functionalisation. US-AuNPs were synthetized following a protocol for obtaining 2-nm diameter nanoparticles[

31], then they were characterised for size (DLS) and plasmonic properties (absorbance reading). Briefly, 375 μl of a 4% HAuCl4 solution and 500 μl of 0.2 M K2CO3 were added to 100 ml of cold Millipore water, while stirring. Then, five 1 mL aliquots of 0.5 mg/ml sodium borohydride (NaBH4) solution were added to the reaction solution while rapidly stirring. US-AuNPs concentration was calculated using a molar extinction coefficient of 6.5 × 10

5 cm

-1 M

-1 at a wavelength of 510 nm [

18]. US-AuNPs were decorated with thiolated sequences (i.e. sequences modified by C3-SS or C6-SS thiol modifier) reduced by incubation of 30 μl of oligonucleotide solution (100 μM) with 3 μl of 100 mM TCEP and 2 μl of Acetate Buffer 100 mM pH 5.2 for 1 hour at room temperature. Reduced sequences were purified with Amicon spin 3 KDa filters and quantified by absorbance reading at 260 nm. For US-AuNPs functionalisation, 1 nanomole of reduced ssDNA was incubated with 100 μl of the US-AuNPs solution with shaking overnight at room temperature. The day after, 500 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.2) buffer and 1M NaCl were gently added dropwise to each vial to obtain a final Tris-acetate concentration of 5 mM and NaCl final concentration of 300 mM. The reaction vials were stored with shaking for one additional night. ssDNA decorated US-AuNPs were purified with Amicon 100 KDa Filters and suspended in 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris acetate, pH 8. The ssDNA/particle ratio was estimated with UV-Vis measurements by subtracting the contribution of the US-AuNPs at 260 nm[

18] from the absorbance value recorded at 260 nm. The obtained value was used for calculating the oligonucleotides concentration. The ssDNA/particle ratio was finally calculated by dividing the ssDNA concentration obtained to the AuNPs concentration value of the solution.

US-AuNPs-Aggregate assembly and characterisation. To prepare the AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate, equal volumes of two separately synthesized batches—RevAS2-US-AuNPs and AS2-US-AuNPs—were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and stored at 4 °C overnight while stirring, and purified by centrifuging the solution at 1000 xg for 2 minutes; the nanoparticle pellet was resuspended in 150 mM NaCl 5 mM Tris-acetate pH 8.2 buffer solution. The AS2ctrl-US-AuNPs-Aggregate was prepared using the same protocol, mixing AS2ctrl-US-AuNPs with RevAS2ctrl-US-AuNPs. DLS and UV-Vis spectroscopy were employed to characterize the size distribution and optical properties of both Aggregates. The plasmonic peaks of the aggregates were determined by identifying the wavelengths at which the first derivative of the absorbance with respect to wavelength equals zero, after applying a five-point average smoothing. Thermal stability was assessed by monitoring the changes in hydrodynamic diameter at DLS across a temperature range of 30°C to 75°C.

AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate PSA response characterisation in PBS. Stability and Kinetic analysis of the AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate in the presence or absence of different concentrations of PSA was conducted for about 30 minutes at 37°C using DLS (set to perform 15 measurements in automatic mode). For these studies, the Aggregate was used at a final concentration corresponding to an absorbance (1 cm light path) of 0.02–0.03 at the plasmon peak. Control reactions were performed with the AS2ctrl-US-AuNPs-Aggregate under identical conditions. PSA was tested initially at 1 pM and 1 nM. DLS data were analyzed using the instrument software with the following settings: material set as gold (refractive index [RI] = 0.20; absorption = 3.320) and dispersant set as water (RI = 1.1330; viscosity = 0.6864). Data processing was carried out under the “general purpose” analysis mode, and the resulting size distributions were reported as provided by the software. Additionally, we further analysed the DLS provided correlogram as explained in the following. The correlogram characterizes the fluctuations of the intensity ; in particular, its autocorrelation function is defined as where the angled bracket indicates an average over time . can usually be written as , where is the normalized electric field autocorrelation function. If the colloid is not monodispersed, becomes a sum of several exponential decays or an integral representing a continuous distribution of hydrodynamic diameters. The DLS software allows for exporting a correlation coefficient derived from the by subtracting the long lag-time background , assuming the intensity remains relatively constant during the measurement, and by applying normalization. This correlation coefficient is proportional to . We fit this function with a squared multiexponential function ; the number of components was set to 2 or 3, with constraints sometimes imposed on possible ranges of . Each corresponds to a hydrodynamic diameter given by (µs) nm in our setup ( is the temperature, the Boltzmann constant, the refraction index and the viscosity of the medium, and =137° as already specified). For the incubation of AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate with PSA, the fitting constraints were: τ₁: 0–250 µs (corresponding to d₁ ≤ 116 nm); τ₂: 250–700 µs (d₂ in the 116–325 nm range) and τ₃: >1 ms (d₃ > 464 nm).

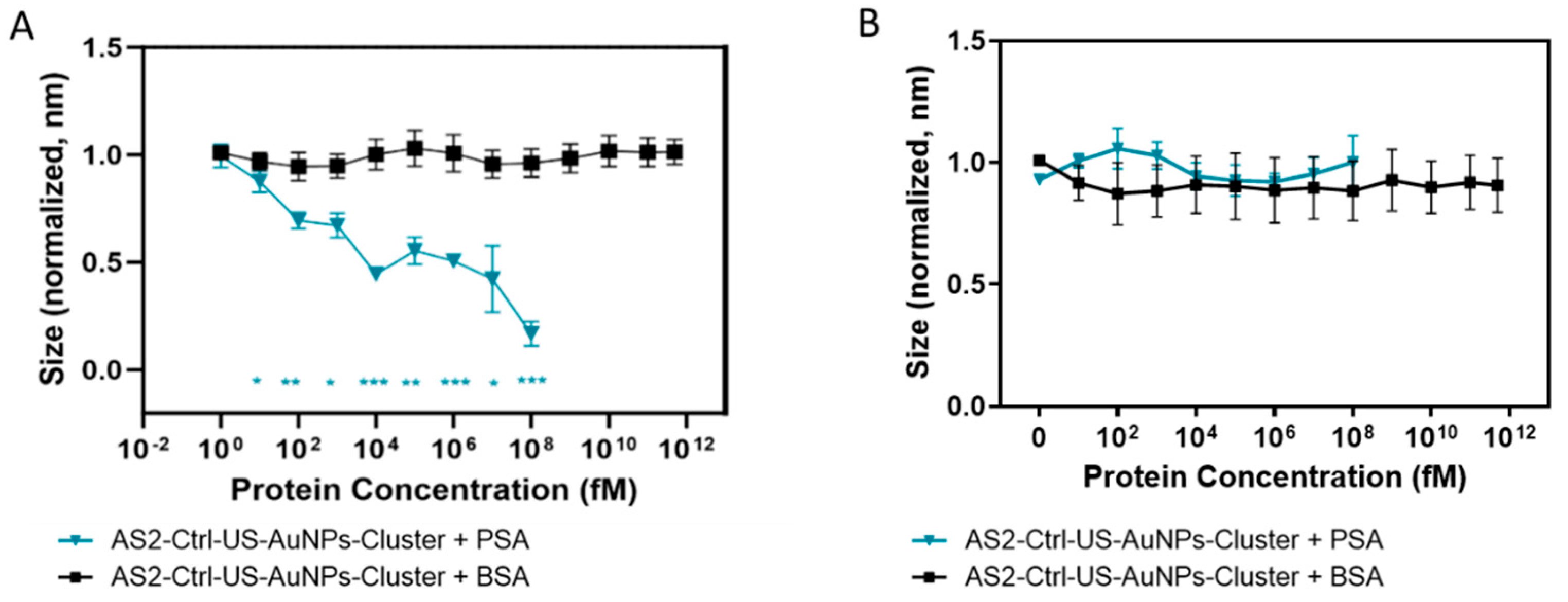

The AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate was then tested by incubating it with PSA in a concentration range between 1 fM to 100 nM. The AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate was also incubated with BSA at a concentration range from 1 fM to 500 μM. The AS2ctrl-US-AuNPs-Aggregate was incubated in the same conditions. These tests were performed at a temperature of 37°C. If not otherwise stated, measurements were taken 15 minutes after the addition of PSA to the Aggregate suspension and recorded for about 5 minutes. The size of the Aggregates was monitored by DLS measurements, and the absorbance spectrum was recorded as well.

Förster Resonance Energy Transfed (FRET) response of annealed AS2-Rhodamine:RevAS2-atto580Q sequences to plasma nucleases. AS2-NH2 and RevAS2-NH2 sequences were labelled respectively with NHS-Rhodamine and atto580Q-NHS-ester. Labelling reaction was performed overnight at room temperature in PBS 10x using a 10-fold molar excess of the fluorophore. The labelled ssDNAs were isolated by fraction collection with DNAPac™ PA100 (Thermo Scientific™) column with HPLC, using Tris HCl 20 mM pH 7.6 (eluent A) and Tris HCl 20 mM NaCl 1 M pH 7.6 (eluent B) as mobile phases with a gradient from 30% to 100% of B mobile phase in 20 minutes of run. Collected fractions were concentrated in MilliQ water using Amicon 3KDa filters, previously coated with BSA 1%. AS2-Rhodamine and RevAS2-atto580Q were annealed at equal molar ratios as described earlier. A solution of 20 nM of AS2-Rhodamine:RevAS2-atto580Q was incubated with human plasma (Biowest, France) diluted 1:8 at a temperature of 37°C. Fluorescence measurements were taken at 15-minute intervals over a duration of 10-30 hours. The fluorimeter was set with an excitation wavelength of 540 nm with a slit aperture of 10 nm, and emission wavelength between 550 and 750 nm with a slit aperture of 5 nm. The photomultiplier tube (PMT) voltage was maintained at 900 V throughout the measurements. Fluorescence intensity, after background removal (refer to S2), was calculated as the area under the curve (AUC) within the wavelength range 570 to 610 nm. For the stability of AS2-Rhodamine:RevAS2-Atto580Q towards DNase I, a solution containing 200 nM of AS2-Rhodamine:RevAS2-Atto580Q was incubated with DNase I 0.3 U/ml. Fluorescence measurements were conducted at 60-minute intervals over a 14-hour period and quantified as before. Averages and integrals have been calculated using Microsoft Excel; fit of the backgrounds have been performed using OriginPro 9 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton MA, USA), calculation of additive and multiplicative constant for the background, background subtraction and integration of the spectra have been automatized using a home-made script in MATLAB R2017b.

Stability of the AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate to DNase I activity. An AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate solution at a DNA final concentration of 200 nM was incubated with DNase I at a concentration of 0.3 U/ml. DNA digestion was monitored by following AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate size and count rate variation with DLS every 60 minutes after the addition of DNase I for 14 hours.

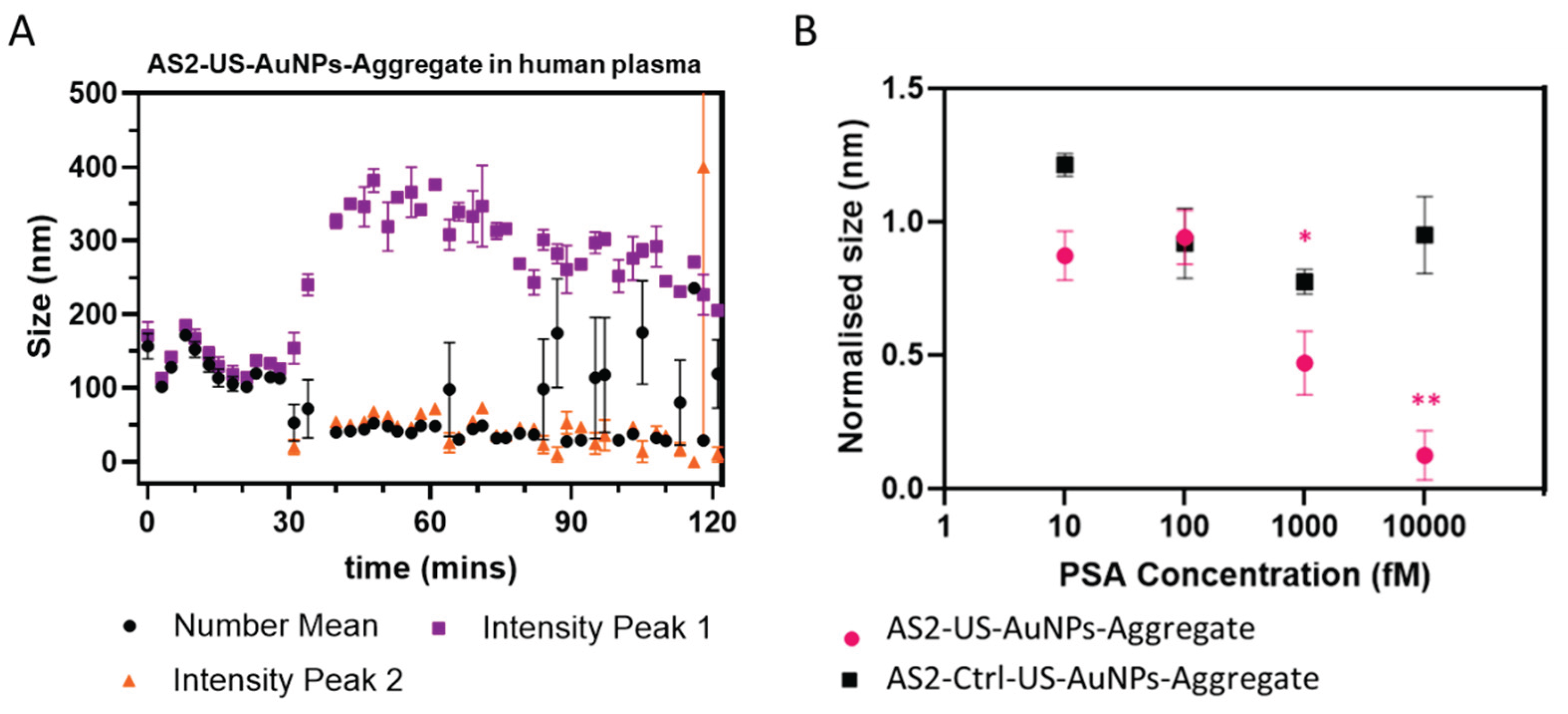

US-AuNPs-Aggregate interaction with filtered Human Plasma. Human female plasma (pooled; TCS Biosciences, United Kingdom) was processed as follows: plasma was first centrifuged at 3,000 xg for 30 minutes at 4 °C to remove cells and cellular debris. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 xg for 1 hour at 4°C and then filtered using SterilFlip® 0.22 μm filter to remove microvesicles. Finally, the supernatant was then centrifuged at 33,000 xg for 1 hour and 30 minutes at 4°C to eliminate exosomes and larger plasma complexes. The obtained supernatant was finally filtered using an Amicon 100 kDa filter at 12,000 xg for 15 minutes, to remove large proteic and lipidic complexes. Plasma was characterised using DLS at every purification step. The stability and the response to PSA presence of the AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregates in the presence of plasma was evaluated incubating them at a concentration causing an optical density of 0.1 at the plasmonic peak, with the filtered plasma diluted 1:6 at a temperature of 37°C. The Aggregate stability was assessed over a 2-hour duration through DLS. The response to PSA was tested at PSA concentrations of 10 fM, 100 fM, 1 pM, and 10 pM. The reaction kinetics were monitored using DLS over a 20-minute interval.

Statistical Tests. All data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (in Tables) or standard error (in Figures). All the data sets were analysed with t-test comparisons. Significance was attributed with a P value less than 0.05. Specifically, in figures significance is represented as follows: P<0.05 is *, P<0.01 is ** and P<0.001 is ***.

4. Discussion

The developed AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregates demonstrated target-responsive rapid disassembly in buffered solutions, with detectable responses at PSA concentrations as low as 10 fM. Under blood-mimicking conditions, a significant signal change was observed starting at 1 pM PSA, with faster and more pronounced kinetics at higher concentrations (10 pM). These results highlight a detection capability that surpasses many existing commercial point-of-care (PoC) assays, positioning the AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate as a promising platform for ultrasensitive biomarker sensing in complex media, with potential for real-time monitoring and early disease detection.

DLS measurements provided valuable insights into the Aggregate size variation during PSA interaction. However, given the limitations of DLS in complex biological matrices —such as signal variability due to polydispersity and interference from plasma components— additional characterization with higher-resolution or molecular-specific techniques is warranted to confirm and refine these findings.

This study represents a preliminary step toward in vivo applications of the AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate system. In a physiological context, nuclease activity, also combined with dynamic blood flow, could have both positive and negative effects. Blood flow would help to remove the detached particles from the interaction site, effectively favouring the kinetics of the system as if it were an irreversible reaction [

23,

24]. In this scenario, the reaction is not limited by the concentration of analyte species, but rather by the absolute number of analyte molecules available, leading to an increased sensitivity. In this scenario, nucleases may facilitate this irreversibility, by digesting faster the oligomers on the disassembled nanoparticles. On the other hand, the spontaneous instability of the aggregates in plasma—partially influenced by nuclease activity—must be carefully considered, particularly in relation of achieving precise temporal control. Within the intended reaction time window, the system must remain stable long enough for PSA recognition, subsequent aggregates disassembly, and excretion of the disassembled nanoparticles to urine, where they can be detected. However, over longer timescales, complete nuclease digestion could be beneficial, ensuring full disassembling and clearance of nanoparticles also in the absence of PSA, an essential feature for safe in vivo applications.

Given that the AS2-US-AuNPs-Aggregate was specifically designed for in vivo applications, optimising its performance and stability in biological environments is essential, and this includes strategies for temporal control of the aggregate integrity. Loynachan[

25] reported the detection of renal-clearable nanoparticles in urine one hour after triggerable-nanostructure injection. In contrast, our system exhibits instability after 30 minutes, highlighting the need for optimization to extend its lifetime in plasma. This could be achieved through the incorporation of antifouling sequences and the use of modified nucleic acids more resistant to nuclease activity[

26].

The use of US-NPs-Aggregate systems could enable in the future the translation of a specific protein biomarker’s presence into a measurable reporter signal in urine. Furthermore, the design of this nanostructure could be adapted for the detection of other disease-associated biomarkers, or configured by using different types of nanoparticles, thereby broadening its potential applications in diagnostic medicine.