Submitted:

04 November 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Animal Feeds

2.2. Feed and Water Intake

2.3. Methane Production

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

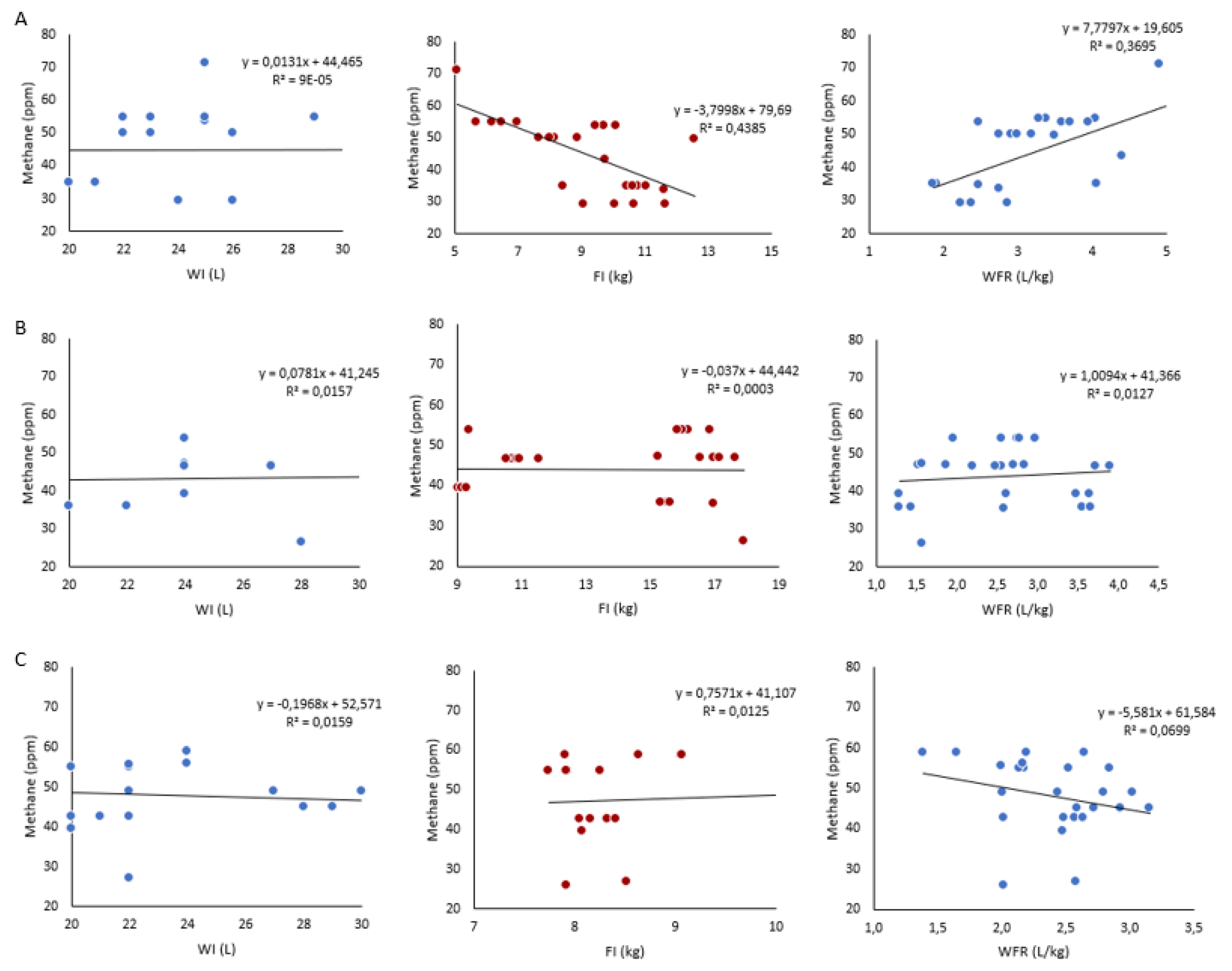

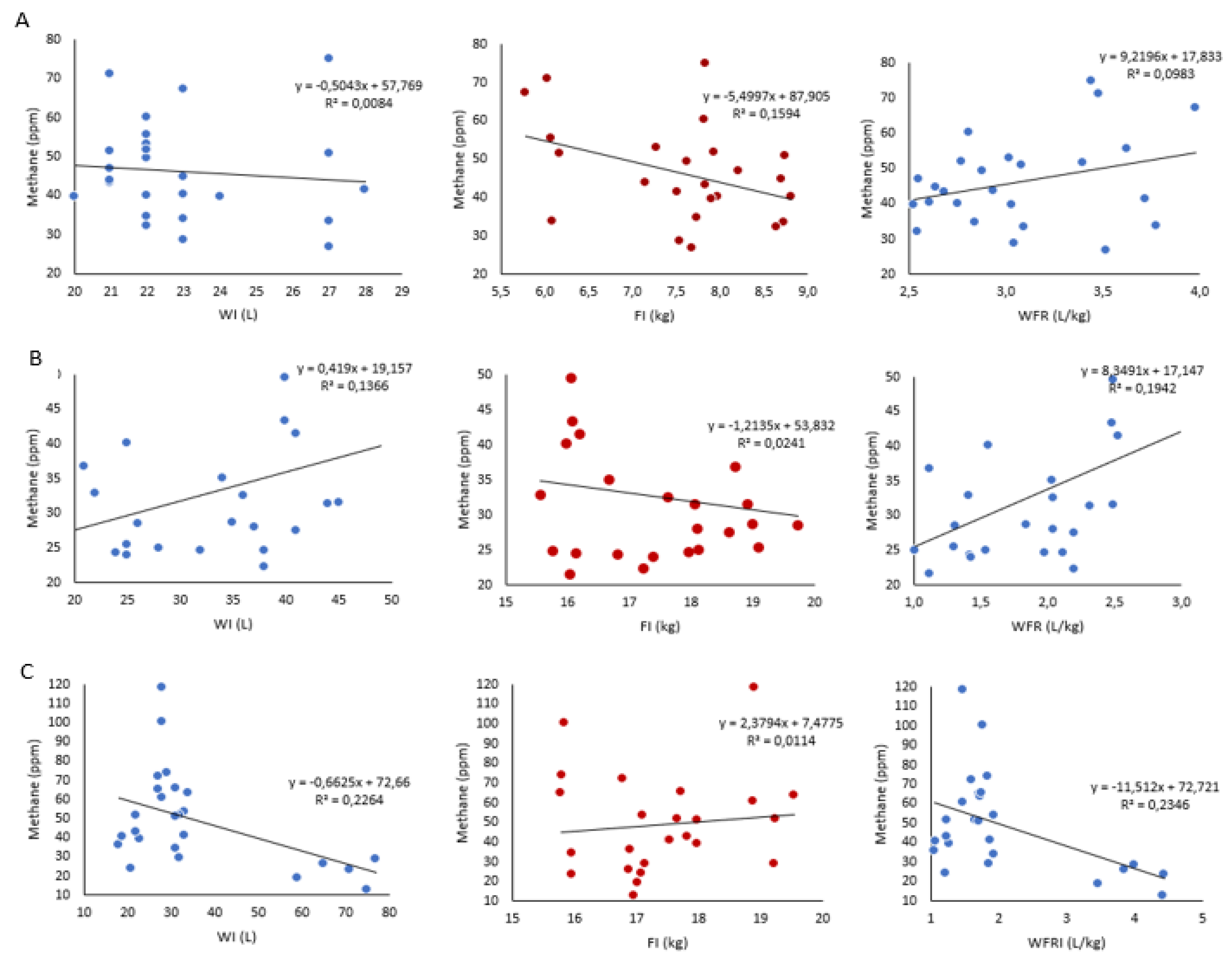

3.1. Water and Feed Intake on Methane Production

| Growth Phase |

Frame size |

Methane (ppm) |

WI (L) |

WC (L) |

FI (kg) |

WFR (L/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | 44.84a±10.02 | 28.96ab±7.85 | 29.66ab±8.06 | 9.17b±3.45 | 3.25a±0.61 | |

| Starter | Medium | 43.93a±10.02 | 34.36a±7.85 | 35.42a±8.06 | 13.85a±3.45 | 2.54b±0.61 |

| Large | 48.14a±10.02 | 22.52b±7.85 | 23.23b±8.06 | 9.29b±3.45 | 2.41b±0.61 | |

| Small | 46.15a±11.75 | 23.04b±5.42 | 23.61b±5.44 | 7.59b±1.53 | 3.07a±0.42 | |

| Grower | Medium | 52.70a±11.75 | 32.32a±5.42 | 33.63a±5.44 | 17.41a±1.53 | 1.86b±0.42 |

| Large | 48.92a±11.75 | 35.84a±5.42 | 37.15a±5.44 | 17.41a±1.53 | 2.07b±0.42 | |

| Small | 34.56b±13.25 | 35.88a±4.27 | 36.57a±4.30 | 10.07a±1.74 | 3.60a±0.64 | |

| Finisher | Medium | 67.33a±13.25 | 28.88b±4.27 | 29.58b±4.30 | 10.16a±1.74 | 2.87b±0.64 |

| Large | 47.12b±13.25 | 29.40b±4.27 | 30.16b±4.30 | 11.05a±1.74 | 2.71b±0.64 |

3.2. Linear Regression and Pearson Correlation Coefficients of Relationships

| Frame size | Variables | Methane (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| WI (L) | 0.009NS | |

| Small | FI (kg) | -0.662*** |

| WFR | 0.608*** | |

| WI (L) | 0.125NS | |

| Medium | FI (kg) | -0.016NS |

| WFR | 0.113NS | |

| WI (L) | -0.126NS | |

| Large | FI (kg) | 0.112NS |

| WFR | -0.264NS |

| Frame size | Variables | Methane (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| WI (L) | 0.448* | |

| Small | FI (kg) | -0.023NS |

| WFR | 0.322NS | |

| WI (L) | 0.370NS | |

| Medium | FI (kg) | -0.155NS |

| WFR | 0.441* | |

| WI (L) | -0.476* | |

| Large | FI (kg) | 0.107NS |

| WFR | -0.484* |

| Frame size | Variables | Methane (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| WI (L) | -0.198NS | |

| Small | FI (kg) | 0.364NS |

| WFR | -0.384NS | |

| WI (L) | -0.087NS | |

| Medium | FI (kg) | -0.146NS |

| WFR | -0.006NS | |

| WI (L) | 0.060NS | |

| Large | FI (kg) | -0.134NS |

| WFR | 0.162NS |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Webb E, Erasmus L. The effect of production system and management practices on the quality of meat products from ruminant livestock. South Afr J Anim Sci. 2014 Jan 9;43(3):413. [CrossRef]

- Saki A. Economic Sustainability of Extensive Beef Production in South Africa. 2020;

- Cheng M, McCarl B, Fei C. Climate Change and Livestock Production: A Literature Review. Atmosphere. 2022 Jan 15;13(1):140. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 2023 [cited 2025 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009157896/type/book.

- Min BR, Lee S, Jung H, Miller DN, Chen R. Enteric Methane Emissions and Animal Performance in Dairy and Beef Cattle Production: Strategies, Opportunities, and Impact of Reducing Emissions. Animals. 2022 Apr 7;12(8):948. [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin KA, Ungerfeld EM, Eckard RJ, Wang M. Review: Fifty years of research on rumen methanogenesis: lessons learned and future challenges for mitigation. Animal. 2020;14:s2–16. [CrossRef]

- Tongwane MI, Moeletsi ME. Emission factors and carbon emissions of methane from enteric fermentation of cattle produced under different management systems in South Africa. J Clean Prod. 2020 Aug;265:121931. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi LO, Abdalla AL, Álvarez C, Anuga SW, Arango J, Beauchemin KA, et al. Quantification of methane emitted by ruminants: a review of methods. J Anim Sci. 2022 July 1;100(7):skac197. [CrossRef]

- Gerber PJ, Hristov AN, Henderson B, Makkar H, Oh J, Lee C, et al. Technical options for the mitigation of direct methane and nitrous oxide emissions from livestock: a review. Animal. 2013;7:220–34. [CrossRef]

- Hristov AN, Melgar A, Wasson D, Arndt C. Symposium review: Effective nutritional strategies to mitigate enteric methane in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2022 Oct;105(10):8543–57. [CrossRef]

- Smith PE, Kelly AK, Kenny DA, Waters SM. Enteric methane research and mitigation strategies for pastoral-based beef cattle production systems. Front Vet Sci. 2022 Dec 23;9:958340. [CrossRef]

- Horwitz W, AOAC International, editors. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. 18. ed., current through rev. 1, 2006. Gaithersburg, Md: AOAC International; 2006. 2400 p.

- SAS Institute. Base SAS 9.4 Procedures Guide, Seventh Edition. 2017;

- Méo-Filho P, Berndt A, Marcondes CR, Pedroso AF, Sakamoto LS, Boas DFV, et al. Methane Emissions, Performance and Carcass Characteristics of Different Lines of Beef Steers Reared on Pasture and Finished in Feedlot. Animals. 2020 Feb 13;10(2):303. [CrossRef]

- Meo-Filho P, Ramirez-Agudelo JF, Kebreab E. Mitigating methane emissions in grazing beef cattle with a seaweed-based feed additive: Implications for climate-smart agriculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2024 Dec 10;121(50):e2410863121. [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe GA, Takahashi T, Orr RJ, Harris P, Lee MRF. Distributions of emissions intensity for individual beef cattle reared on pasture-based production systems. J Clean Prod. 2018 Jan;171:1672–80. [CrossRef]

- McAllister TA, Stanford K, Chaves AV, Evans PR, Eustaquio De Souza Figueiredo E, Ribeiro G. Nutrition, feeding and management of beef cattle in intensive and extensive production systems. In: Animal Agriculture [Internet]. Elsevier; 2020 [cited 2025 Feb 9]. p. 75–98. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128170526000057.

- Terry SA, Basarab JA, Guan LL, McAllister TA. Strategies to improve the efficiency of beef cattle production. Miglior F, editor. Can J Anim Sci. 2021 Mar 1;101(1):1–19.

- Neel JPS, Turner KE, Coleman SW, Brown MA, Gowda PH, Steiner JL. Effect of Frame Size on Enteric Methane (CH4) and Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Production by Lactating Beef Cows Grazing Native Tall-Grass Prairie Pasture in Central Oklahoma, USA, 1: Summer Season. J Anim Sci Res [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Feb 9];3(3). Available from: https://www.sciforschenonline.org/journals/animal-science-research/JASR130.php.

- Ojo AO, Mulim HA, Campos GS, Junqueira VS, Lemenager RP, Schoonmaker JP, et al. Exploring Feed Efficiency in Beef Cattle: From Data Collection to Genetic and Nutritional Modeling. Animals. 2024 Dec 17;14(24):3633. [CrossRef]

- Gerber PJ, Mottet A, Opio CI, Falcucci A, Teillard F. Environmental impacts of beef production: Review of challenges and perspectives for durability. Meat Sci. 2015 Nov;109:2–12. [CrossRef]

- Haque MN. Dietary manipulation: a sustainable way to mitigate methane emissions from ruminants. J Anim Sci Technol. 2018 Dec;60(1):15. [CrossRef]

- Ismail M, Al-Ansari T. Enhancing sustainability through resource efficiency in beef production systems using a sliding time window-based approach and frame scores. Heliyon. 2023 July;9(7):e17773. [CrossRef]

- Mapiye O, Chikwanha OC, Makombe G, Dzama K, Mapiye C. Livelihood, Food and Nutrition Security in Southern Africa: What Role Do Indigenous Cattle Genetic Resources Play? Diversity. 2020 Feb 12;12(2):74. [CrossRef]

- Pressman EM, Kebreab E. A review of key microbial and nutritional elements for mechanistic modeling of rumen fermentation in cattle under methane-inhibition. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2024 Nov 21 [cited 2025 July 28];15. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1488370/full.

- Goopy JP, Korir D, Pelster D, Ali AIM, Wassie SE, Schlecht E, et al. Severe below-maintenance feed intake increases methane yield from enteric fermentation in cattle. Br J Nutr. 2020 June 14;123(11):1239–46. [CrossRef]

- Galyean ML, Hales KE. Feeding Management Strategies to Mitigate Methane and Improve Production Efficiency in Feedlot Cattle. Animals. 2023 Feb 20;13(4):758. [CrossRef]

- Hristov AN, Oh J, Giallongo F, Frederick TW, Harper MT, Weeks HL, et al. An inhibitor persistently decreased enteric methane emission from dairy cows with no negative effect on milk production. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015 Aug 25;112(34):10663–8. [CrossRef]

- Romanzin A, Degano L, Vicario D, Spanghero M. Feeding efficiency and behavior of young Simmental bulls selected for high growth capacity: Comparison of bulls with high vs. low residual feed intake. Livest Sci. 2021 July;249:104525. [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin KA, Tamayao P, Rosser C, Terry SA, Gruninger R. Understanding variability and repeatability of enteric methane production in feedlot cattle. Front Anim Sci. 2022 Nov 3;3:1029094. [CrossRef]

- Miller GA, Auffret MD, Roehe R, Nisbet H, Martínez-Álvaro M. Different microbial genera drive methane emissions in beef cattle fed with two extreme diets. Front Microbiol. 2023 Apr 13;14:1102400. [CrossRef]

- Løvendahl P, Difford GF, Li B, Chagunda MGG, Huhtanen P, Lidauer MH, et al. Review: Selecting for improved feed efficiency and reduced methane emissions in dairy cattle. Animal. 2018;12:s336–49. [CrossRef]

- Cottle DJ, Eckard RJ. Global beef cattle methane emissions: yield prediction by cluster and meta-analyses. Anim Prod Sci. 2018;58(12):2167. [CrossRef]

- Garnsworthy PC, Saunders N, Goodman JR, Algherair IH, Ambrose JD. Effects of live yeast on milk yield, feed efficiency, methane emissions and fertility of high-yielding dairy cows. animal. 2025 Jan;19(1):101379. [CrossRef]

- Basarab JA, Beauchemin KA, Baron VS, Ominski KH, Guan LL, Miller SP, et al. Reducing GHG emissions through genetic improvement for feed efficiency: effects on economically important traits and enteric methane production. Animal. 2013;7:303–15. [CrossRef]

- Knapp JR, Laur GL, Vadas PA, Weiss WP, Tricarico JM. Invited review: Enteric methane in dairy cattle production: Quantifying the opportunities and impact of reducing emissions. J Dairy Sci. 2014 June;97(6):3231–61. [CrossRef]

- Thompson LR, Rowntree JE. Invited Review: Methane sources, quantification, and mitigation in grazing beef systems. Appl Anim Sci. 2020 Aug;36(4):556–73. [CrossRef]

- Beede DK. What will our ruminants drink? Anim Front. 2012 Apr 1;2(2):36–43. [CrossRef]

- Morales AG, Cockrum RR, Teixeira IAMA, Ferreira G, Hanigan MD. Graduate Student Literature Review: System, plant, and animal factors controlling dietary pasture inclusion and their impact on ration formulation for dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2024 Feb;107(2):870–82. [CrossRef]

- Grossi G, Goglio P, Vitali A, Williams AG. Livestock and climate change: impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies. Anim Front. 2019 Jan 3;9(1):69–76. [CrossRef]

- Smith PE, Waters SM, Kenny DA, Kirwan SF, Conroy S, Kelly AK. Effect of divergence in residual methane emissions on feed intake and efficiency, growth and carcass performance, and indices of rumen fermentation and methane emissions in finishing beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 2021 Nov 1;99(11):skab275. [CrossRef]

- O’Meara FM, Gardiner GE, O’Doherty JV, Lawlor PG. Effect of water-to-feed ratio on feed disappearance, growth rate, feed efficiency, and carcass traits in growing-finishing pigs. Transl Anim Sci. 2020 Apr 1;4(2):630–40. [CrossRef]

- Leng RA. Interactions between microbial consortia in biofilms: a paradigm shift in rumen microbial ecology and enteric methane mitigation. Anim Prod Sci. 2014;54(5):519. [CrossRef]

- Lan W, Yang C. Ruminal methane production: Associated microorganisms and the potential of applying hydrogen-utilizing bacteria for mitigation. Sci Total Environ. 2019 Mar;654:1270–83. [CrossRef]

- Mwangi FW, Charmley E, Gardiner CP, Malau-Aduli BS, Kinobe RT, Malau-Aduli AEO. Diet and Genetics Influence Beef Cattle Performance and Meat Quality Characteristics. Foods. 2019 Dec 6;8(12):648. [CrossRef]

| Feed ingredient (kg) | Starter | Grower | Finisher |

| Hominy chop | 630 | 670 | 690 |

| Eragrostis hay | 200 | 180 | 160 |

| Soya oilcake | 80 | 60 | 60 |

| Molasses | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Limestone | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Urea | 8.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| Salt | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Vit/mineral premix | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| Estimated nutrient specifications (%) | |||

| DM | 92.35 | 93.81 | 93.13 |

| TDN | 74.22 | 74.69 | 75.26 |

| NE (MJ/kg) | 6.81 | 6.85 | 6.91 |

| CF | 8.41 | 7.69 | 7.08 |

| CP | 13.72 | 13.39 | 13.51 |

| Ca | 6.98 | 6.86 | 6.79 |

| P | 3.13 | 3.10 | 3.14 |

| Growth phase | Variables | Methane (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| WI (L) | -0.297NS | |

| Starter | FI (kg) | -0.409 NS |

| WFR | -0.048 NS | |

| WI (L) | -0.474 NS | |

| Grower | FI (kg) | -0.211 NS |

| WFR | -0.175 NS | |

| WI (L) | -0.688* | |

| Finisher | FI (kg) | -0.175 NS |

| WFR | -0.107 NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).