1. Aim of This Review

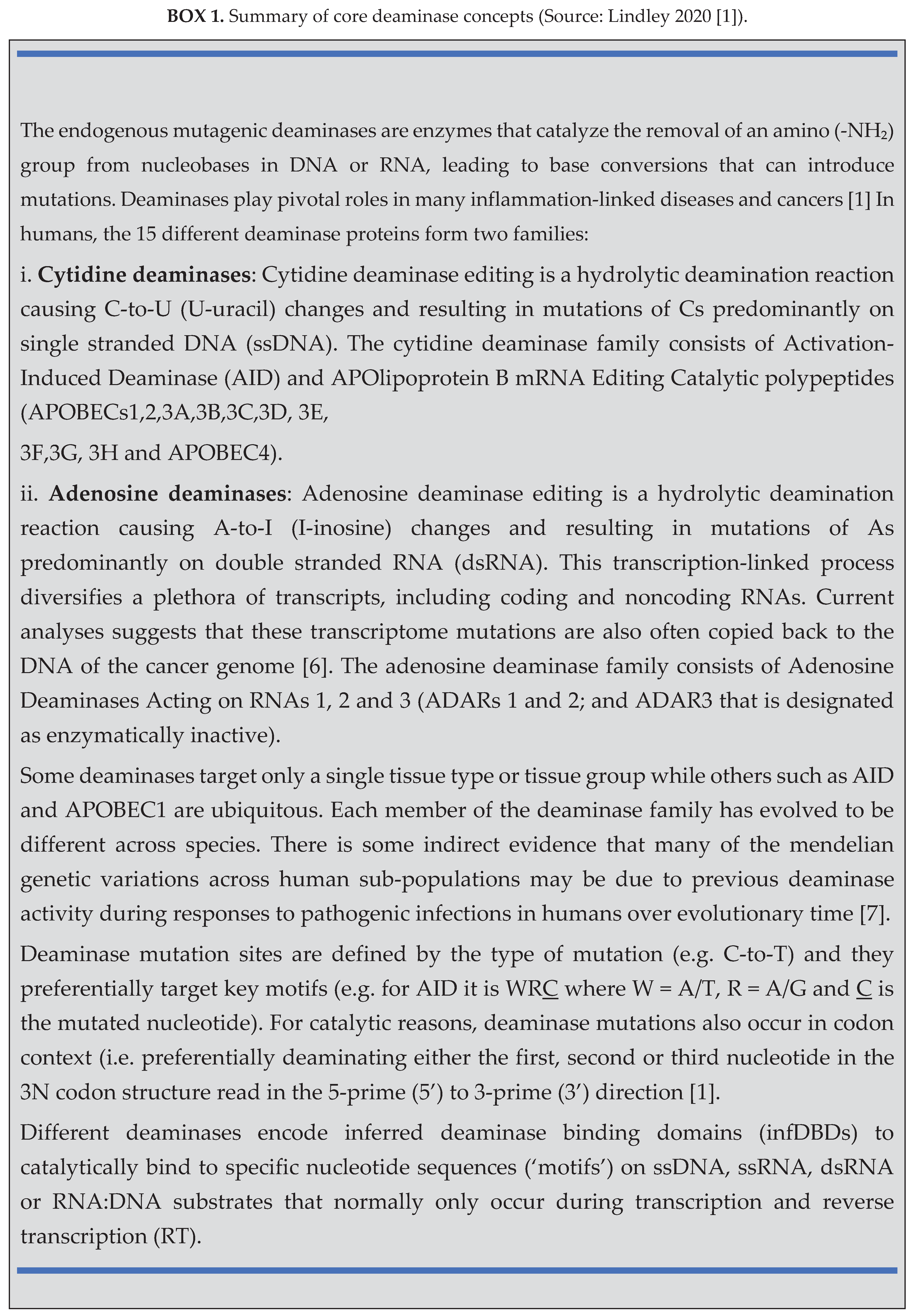

We are now becoming aware of the crucial immunomodulatory and oncogenic roles that a group of endogenous mutagenic enzymes called deaminases play in health and disease. All metazoan life forms carry a cargo of cytosine (C) and adenosine (A) deaminases that co-ordinate a wide range of genomic, epigenomic and regulatory modifications that are a crucial part of an inflammatory response [

1,

2]. [Box 1 provides a summary of core deaminase concepts.] The aim of this review is to describe how these enzymes are now being repurposed as precision therapeutic tools fueling the development of a fundamentally new generation of deaminase modulation drugs. While only a few deaminase modulating drugs are currently approved for clinical use, many are in development. We use examples to highlight the therapeutic promise of these new drugs.

2. Deaminase Action in Inflammation, Immunity and Disease

Inflammation is part of the body’s immune defense that is activated in response to foreign pathogens (e.g. viruses, bacteria, prions, fungi), environmental agents (e.g. toxins, UV exposure, physical trauma) and imperfect wound healing [

3].

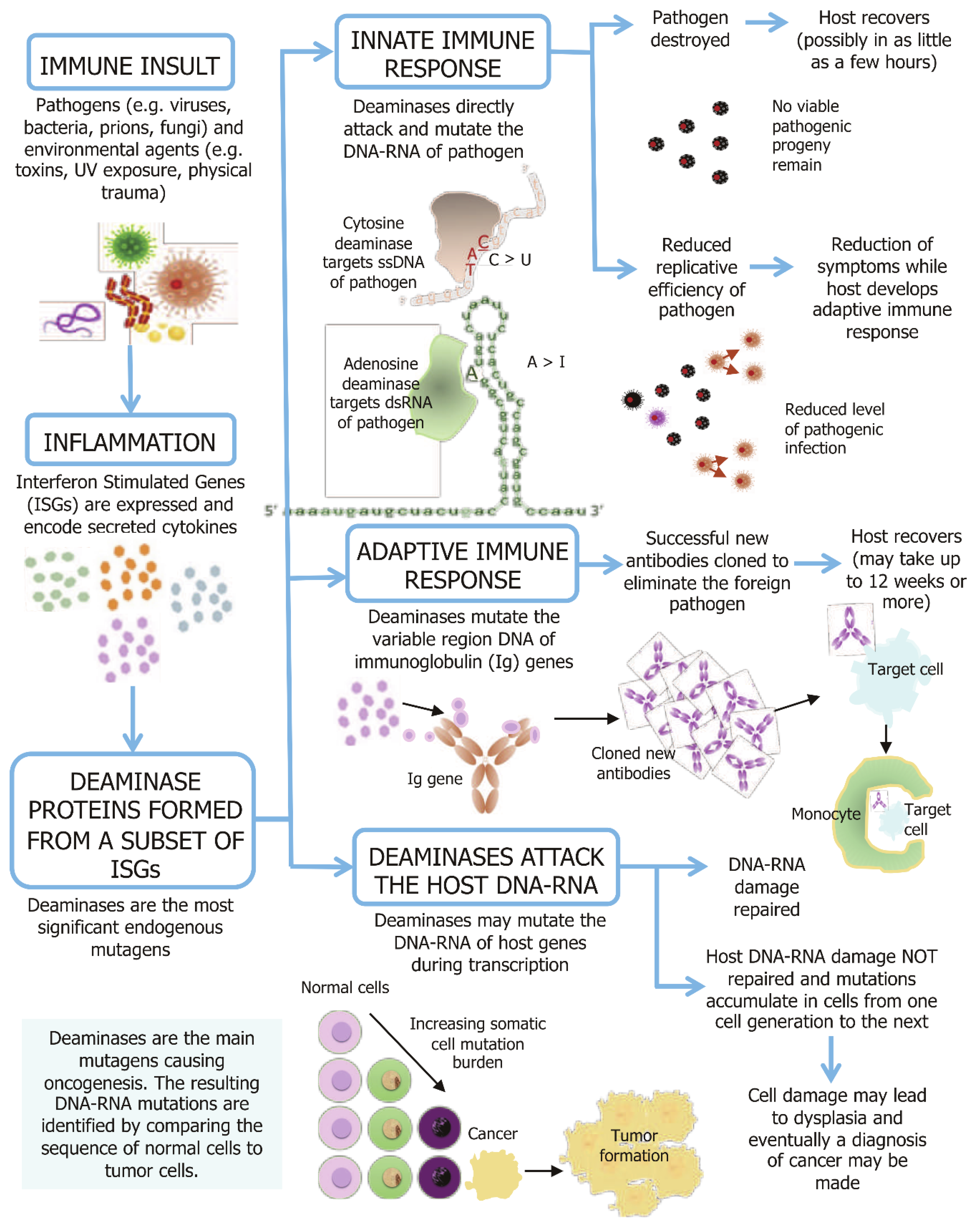

Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the causal links between an inflammatory response and the roles of deaminases in immunity and inflammation-linked disease progression. During a normal inflammatory response, a complex set of interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) pathways are activated. Some deaminase genes are encoded by the ISGs, with their transcription upregulated when interferon signaling is triggered [

4]. Deaminase catalysis is essential for both innate and adaptive immunity. In the innate immune system, many deaminases directly mutate the DNA or RNA of foreign pathogens to attenuate or eliminate the level of viable pathogenic progeny. In the adaptive immune system, B lymphocyte activation induced cytidine deaminase (AID) activity plays crucial roles in somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class switch recombination (CSR) for generating both the diversification of the functional class of immunoglobulins (Ig) and by enhancing antibody specificity and affinity.

The activity or dysregulation of deaminase proteins may also result in some uncorrected mutations in normal somatic tissue during cellular transcription. While most mutations are corrected, the accumulation of uncorrected mutations is now causally linked to the progression of many inflammation-linked diseases, aging and oncogenesis.

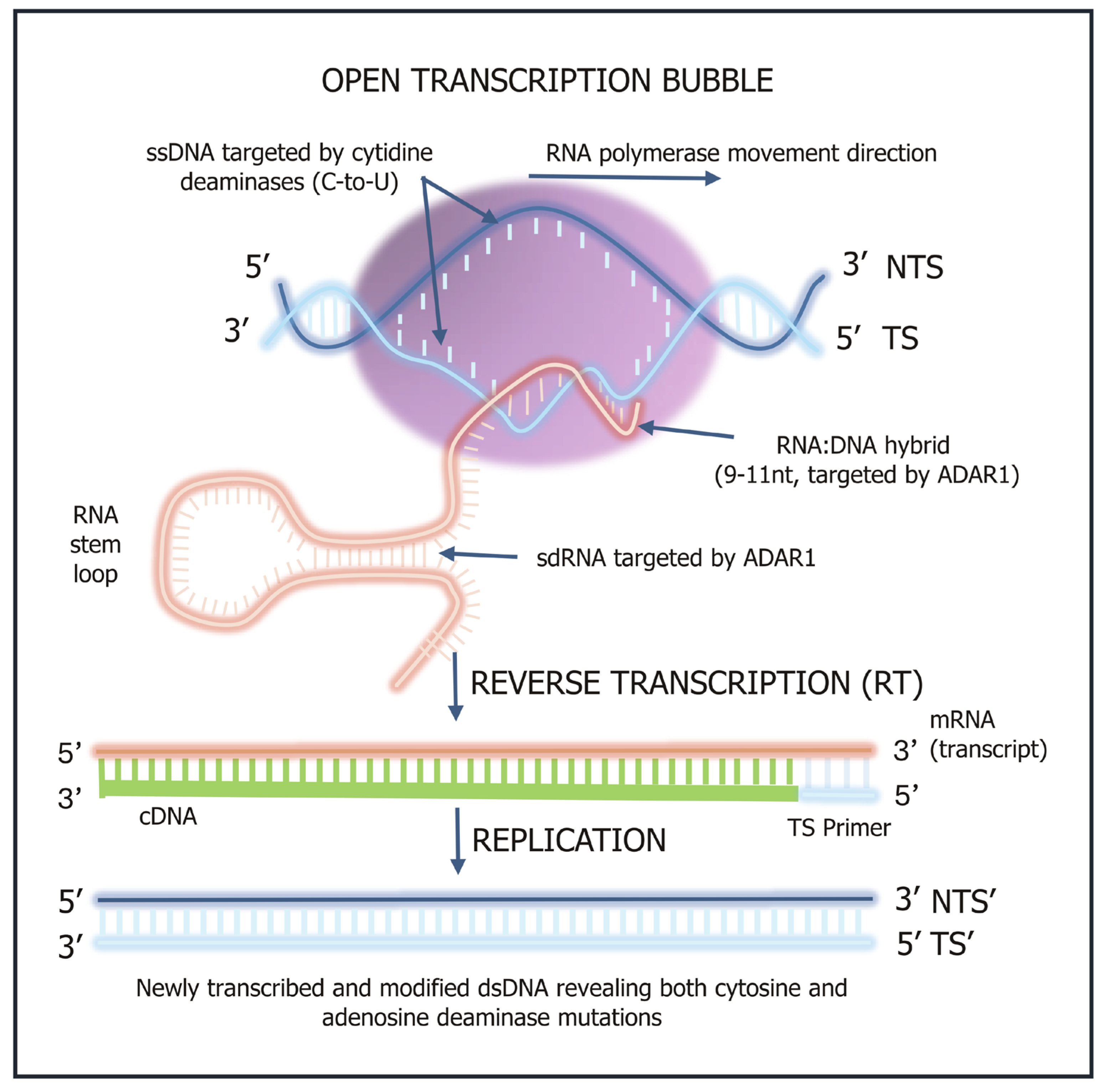

Figure 2 shows the key molecular steps involved in deaminase-driven transcription and reverse transcription (DRT) activity [

5,

6] and shows when single stranded DNA (ssDNA), double stranded RNA (dsRNA) and annealed nascent RNA:DNA hybrids become available for deaminase mutagenic activity.

3. Innate Immune Response

The AID, APOBEC3s (apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide 3s) and ADARs (adenosine deaminases acting on RNA) are crucial parts of the first line of innate immune defense against invading pathogens. They act coordinately to reduce the number of viable progeny or to eradicate the pathogenic impact on the host by launching a direct mutagenic attack on various DNA or RNA target motifs exposed during the lifecycle of most pathogens. As many of the pathogenic progeny may remain viable with the accumulated new mutation burden, the pathogen may in turn benefit from some mutations and acquire altered characteristics to be passed on as a new strain to another host of the same species, or from vertebrate non-humans to humans as a zoonotic disease. This host-pathogen battle may accelerate the evolution of new pathogenic or more virulent strains and possibly promote drug resistance such as antibiotic resistance.

3.1. APOBEC3 Deaminases as ‘Viral Smashers’

The human APOBEC3 enzymes have been widely studied and have been shown to impact replication of many viruses such as human immunodeficiency (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), flaviviruses such as Zika (10) and coronaviruses like severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [

11,

12] herpesviruses, and papillomaviruses, and several retroelements [

13]. The role of deaminases in building innate immunity for HBV has been widely studied. It is a major risk factor predicting the likelihood of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

14,

15]. The cytidine deaminases suppress HBV replication by deaminating and destroying the major form of the HBV genome, the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), without toxicity to the infected cells [

16,

17]. Interferon (IFN)-alpha is used to indirectly activate the APOBEC3 genes in primary hepatocytes [

18] to suppress HBV transcription and replication, and there is also a lower risk of cancer occurrence [

19].

Thus, in recent years, engineering APOBEC3 deaminases has emerged as a promising strategy in antiviral research. Several examples show that even minor changes in the structure of deaminases can give them completely new and unique properties [

20]. Although at present the development of such antivirals is complicated by the lack of tools for activating and controlling deaminase expression in vivo, this strategy presents an opportunity to design new ways to enhance our innate immunity in the face of evolving or emerging new viruses.

3.2. Using Deaminases to Develop New Antimicrobial Drugs

The emergence of antimicrobial drug resistance is a significant global threat leading to a rapid increase in the prevalence of bacterial infections that can no longer be treated with available antibiotics. The World Health Organization estimates that by 2050 up to 10 million deaths per year might be attributed to antimicrobial resistance [

21]. The same host-pathogen interactions that give rise to new viral strains can also be responsible for the evolution of microbes that become resistant to current antibiotics.

At present two structure-based drug design approaches are being used to fight antibiotic resistant microbes: these include targeting structures within bacterial cells (similar to existing antibiotics); and/or targeting virulence factors rather than bacterial growth [

21]. Some of these new drug development strategies are now being used in preclinical studies to identify new molecular candidates for further investigation in animal and human trials. Several advancements in deaminase engineering also hold potential for introducing precise genomic modifications in microbes to counteract antibiotic resistance mechanisms. In recent years, engineered tRNA-specific adenosine (TadA) deaminase variants have been widely studied and adapted for base editing in genome engineering. TadA deaminase variants, enhanced cytosine base editors have been created with high on-target activity and reduced off-target effects [

22,

23].

An alternate deaminase modulating drug development strategy could involve engineering targeted nuclear-localized DBD heterodimers to build a new generation of microbe-specific antimicrobials. As an example, deaminases such as engineered ADAR1p110 could be used as a nuclear shuttle vector to deliver the DNA and/or RNA ‘nuclear microbe warheads’ carrying a payload of microbe-specific DBDs to their intended targets and catalytically rendering them unviable [

20]. Single amino acid substitutions in deaminases can lead to changes in their recognized nucleic acid type, or cause deaminases to accept either DNA or RNA targets.

4. Adaptive Immune Response

In the adaptive immune system, AID is essential for generating new antibody repertoires to effectively fight foreign pathogens [

24]. AID was the first cytosine deaminase to be identified by Tasuku Honjo’s group in 1999 when it was shown to be essential for SHM and CSR in both mice and humans [

25,

26]. The DNA deamination model of how AID promotes antibody diversity among immunoglobulin (Ig) genes is now widely supported [

27,

28]. As the efficacy of our adaptive immune system is dependent upon AID proteins, the regulation of AID expression in B-cells is important. The therapeutic enhancement or suppression of AID might therefore be clinically beneficial to modulate AID enzymatic activity in lymphoid tissue. It is a curious anomaly that there is still only indirect evidence suggesting that the roles of both APOBECs and ADARs are important in promoting B cell diversification [

5,

29,

30].

4.1. Therapeutic Inhibition of AID in Lymphoid Tissue

A wide range of adverse health conditions such as chronic inflammation are associated with AID dysregulation or overexpression. Abnormalities in AID have been shown to disrupt gene networks and signaling pathways in both B-cell and T-cell lineage lymphoblastic leukemia, although the full extent of its role in lymphoid carcinogenesis remains unclear [

31]. A classic manifestation of downregulation of AID expression is hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2) [

26]. The most direct manifestation of the upregulation of AID expression in lymphoid cells is that it promotes the development of B-cell lymphomas that emerge from hypermutation and antigenic selection in post-antigenic germinal centers (GCs). This is due to its natural ability to modify DNA through deamination in lymphoid cells [

32,

33]. Lymphomas can result from AID causing strand breaks in the Ig heavy chains regions [

34,

35]. Montamat-Sicotte et al. [

36] found that Heat Shock Protein 90 inhibitors decrease AID protein levels and reduced disease severity in a mouse model of acute B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia in which AID accelerates disease progression. Tepper et al. [

37] showed that poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) is another key factor restricting AID activity and SHM at the Ig variable region. Thus PARP-1 inhibitor therapy might also be used more widely as an AID inhibitor. Other consequences of AID overexpression include AID generated mutations that result in resistance to lymphoma drugs [

38]. Thus, there is mounting evidence pointing to the possible clinical benefits of therapeutically suppressing AID for a range of B-cell related diseases.

In 2015, King et al. [

39] demonstrated that AID activity can be modulated by modifying the accessibility of the deamination catalytic pocket and the DNA binding ability in its tertiary structure. More recently, to develop the first generation of AID small molecules that could modulate AID activity, Alvarez-Gonzalez et al. [

40] used a fluorescence-based reporter assay to identify three compounds that reduced CSR and base editing and thus demonstrating the feasibility of modulating AID activity in biological systems. Such studies are laying an important foundation for the eventual development of this new drug class of AID inhibitors.

4.2. Can AID Be Used to Improve Vaccine Efficacy?

There is a need to improve the efficacy of vaccines by investigating new adjuvant therapies to boost immunogenicity. At present, aluminum salt adjuvants like aluminum hydroxide gel and aluminum phosphate are often used as commercial antigen-nonspecific vaccine adjuvants to potentiate the immune response [

41]. These work by inducing a 2-3-fold higher rate of B cell mutations that are associated with a higher expression of AID which is the major enzyme controlling B cell receptor (BCR) affinity maturation [

42].

Many studies have also been conducted to investigate the use of interferons as adjuvants (IFN-α, -β, -γ and -λ) [

43]. Recently there has also been an increased interest in using self-assembled nanoparticles based on graphene oxide (GO) quantum dots as a vaccine adjuvant. As an example, zinc-based graphene oxide adjuvant reagent (ZnGC-R) is designed as a new adjuvant for the influenza vaccine. It has a higher been shown that ZnGC-R induced a 342% stronger IgG antibody response compared with vaccines using inactivated virus alone and leading to 100% in vivo protection efficacy against an H1N1 influenza virus challenge [

44]. However, GO injections can lead to significant oxidative stress and inflammation as its use stimulates the release of a specialized subset of cytokines that primarily direct cell migration [

45]. The antigen presenting cells migrate to the lymph nodes where antibody class switching and maturation takes place giving rise to high affinity and long-lasting antibody production (

Figure 1, 46).

Each of these current approaches for developing new adjuvant therapies rely on indirect strategies to potentiate immunogenicity. As deaminase proteins are expressed as a subset of the IFN stimulated cytokine release pathway, the translation and optimization of AID-based adjuvants might therefore be considered for future investigation.

5. Cytidine Deaminase Modulation and Non-Lymphoid Cancer

Chronic inflammation is a known risk factor for cancer initiation and progression [

47]. Once oncogenesis is initiated, deaminase mutagenic activity becomes increasingly "dysregulated" by potentially targeting expressed genes during transcription. In this section, some examples reporting the diverse roles of deaminases in oncogenesis and the emerging opportunities for developing new deaminase-based therapies are identified.

5.1. AID Modulation in Non-Lymphoid Cancers

Apart from AID’s natural physiological function in B cell maturation and antibody production, AID also introduces double-strand breaks in non-Ig genes making them more unstable (34) and associated with chromosomal translocations (33, 48). Some AID-driven mechanisms in non-B cells have been identified as oncogenic [

31,

32,

49] and also play a role in the reprogramming of genomic DNA methylation [

50,

51,

52]. Gene promoters targeted by AID exhibit abnormally low methylation levels, indicating high activation of these genes [

53]. It has also been reported that the tumor necrosis factor a (TNFα) triggers abnormal AID expression in certain inflammation-related cancers such as helicobacter pylori-associated gastric cancer and colitis-associated colon cancers [

54,

55].

Our understanding of these and other roles of AID in non-B cell cancers is further compounded by the increasing evidence showing that there is a high level of Ig expression in many non-lymphoid malignancies and is produced by the cancer cells themselves. Although the cancer-derived Ig shares identical basic structures with B cell-derived Ig, the cancer-derived Ig has restricted variable region sequences and shows aberrant glycosylation [

56]. Additionally, cancer-derived IgG was shown to be a predictor of lymph node metastasis and worse prognostic outcomes. However, although AID has a direct mutagenic role in cancers, we have little understanding of the co-dependence of the roles of AID in SHM and non-B cell Ig expression in tumors. This suggests that it is likely to be some time before new AID modulating drugs will be approved for clinical use in non-lymphoid cancers.

5.2. APOBEC3 Modulation in Oncology

Over the last decade, many studies have contributed to our understanding of how members of the APOBEC3 homologous family of deaminases influence oncogenesis. The APOBEC3-mediated signatures are often detected in sub-clonal branches of tumor phylogenies and are acquired in cancer cell lines over time, indicating that APOBEC3 mutagenesis is likely ongoing in oncogenesis [

57]. Since APOBEC3s induce a high level of DNA damage, their targeted overexpression in cancer cells may also be cytotoxic [

58]. Based on these and many other APOBEC3 studies, it is evident that there are many new development opportunities using APOBEC3 modulation in cancers (Table 6, 59). The following examples draw attention to how some of these may improve clinical outcomes.

5.2.1. Promoting Immune Activation in the Tumor Microenvironment

Pan-cancer analyses have found that high APOBEC3-mediated mutagenesis is associated with increased immune activation in the solid tumor microenvironment for a range of cancers [

60]. For example, studies in breast cancer report that high APOBEC3B expression is associated with more tumor infiltrating lymphocytes [

61,

62]. APOBEC3C-H expression levels are correlated with more cytotoxic T cell lymphocytes (CTLs) effector form CD8 T cells in the tumor microenvironment, increased T cell receptor diversity, and greater cytolytic activity [

62,

63]. Similar immune activation has been observed in bladder cancer, with multiple studies detecting increased immune signatures and interferon signaling in APOBEC3-high tumors [

64,

65]. In lung cancer, T cell-mediated immune activation was linked with high APOBEC3B expression and high APOBEC3 induced mutation loads [

66,

67]. In ovarian cancer, elevated APOBEC3B and APOBEC3G expression have been associated with greater immune cell infiltration [

68].

A few studies have also reported that APOBEC3s are immune-suppressive (Table 4, 59). In some cancers a higher APOBEC3B expression was found to be associated with less immune cell infiltration in adrenocortical carcinoma and gastric cancer [

60,

69]. Although not in the tumor itself, increased APOBEC3A expression causes C-to-U mutations in RNA in thousands of genes and in monocytes and macrophages [

70], and it has been shown to shift macrophage polarization to a pro-inflammatory, immune activating state [

71,

72]. Activation of APOBEC3A alone may also cause apoptosis in vitro, as it has the highest deamination activity among the APOBEC3s [73, 74)]

Understanding the relationship between APOBEC3B activity and cyclic hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment is also important. Evidence from in vivo experiments suggests that cyclic hypoxia is the primary cause of most deaminase-driven solid tumor cancers and is associated with the resistance to standard therapies, genomic instability and a poor patient prognosis [

75]. Using tumor cell lines for a number of cancers that included colorectal, breast, bladder, lung, and esophageal tumor cell lines, it was shown that cyclic hypoxic conditions induce the expression and activity of APOBEC3B.

In summary, controlled APOBEC modulation, rather than complete inhibition in the tumor microenvironment of some cancers, could improve patient outcomes by promoting tumor immunogenicity. Other impacting factors such as cyclic hypoxia also need to be considered. Trials using localized modulation in the tumor microenvironment have the added advantage of minimizing off-target mutagenesis and systemic toxicity while preserving beneficial mutational processes in healthy cells.

5.2.2. Increasing Response to Cancer Therapeutics

To date, many studies have focused on the anti-tumor benefits of APOBEC3 mutation activation, partly based on the observation that those patients with a higher mutation burden tended to respond better to immunotherapy, including the checkpoint inhibitors [

76]. Overexpression of APOBEC3s was shown to increase responsiveness to targeted ATR (Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3-Related) and Chk1/2 (Checkpoint Kinase 1 and 2) inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia and osteosarcoma cell lines [

77,

78]. Similarly, APOBEC3B overexpression sensitized tumor protein 53 deficient (p53-deficient) cells to Chk1/2 checkpoint kinases (regulate the cell cycle), Wee1 kinase (regulates the cell cycle), and PARP enzymes (involved in repairing breaks in ssDNA) inhibition [

79]. Increased sensitivity to PARP inhibitors was also observed with APOBEC3A upregulation in pancreatic cancer cells [

80]. In a 2018 study, Fujiki et al. [

81] showed that APOBEC3B messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels correlated with the efficacy of chemotherapy and that high APOBEC3B mRNA expression was a predictive factor for pathological Complete Response (pCR).

Research also indicates that members of the APOBEC3 family, particularly APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B, can upregulate PD-L1 (Programmed Death-Ligand 1) expression and potentially enhance responses to immunotherapy. It was shown that APOBEC3B upregulation is significantly associated with immune gene expression, including PD-L1 expression and T-cell infiltration in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

66]. Another study reported that APOBEC3A expression positively correlates with PD-L1 levels in many other cancers, including lung adenocarcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, breast invasive cancer, cervical cancer, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [

41]. The study proposed that APOBEC3A induces PD-L1 expression through the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK/c-JUN) signaling pathway, that is independent of interferon signaling.

However, there are also some studies reporting that inhibiting the APOBEC3 deaminases could be therapeutically beneficial. For example, it was reported that APOBEC3 inhibitors could prevent non-muscle invasive bladder cancer from progressing to muscle-invasive disease [

82]. It was shown that APOBEC3B expression is associated with poor prognosis for breast cancer and some other cancers [

83]. In a bioinformatics study by Ma et al. [84)] it was shown that the high expression of APOBEC3G was also significantly associated with short overall survival (OS) in non-M3 acute myeloid leukemia (non-AML) patients which are the vast majority of AML patients. This study also identified that treatment with crotonoside (a natural plant product) can reduce the expression of APOBEC3G and thus inhibit the viability of different AML cells in vitro. Crotonoside, a potent guanosine tyrosine kinase inhibitor with immunosuppressive effects, is now considered to be one possible natural candidate for APOBEC3G inhibition in non-AML patients.

Thus, while APOBEC3 inhibition holds therapeutic potential to improve patient outcomes in certain cancers by limiting tumor evolution, subclone heterogeneity, and therapy resistance, there may also be cases where APOBEC3 supplementation could enhance immune support and improve responsiveness to selected therapies. In both scenarios, the relationships between the different APOBEC3 isomers need to be better understood.

5.2.3. Overcoming Drug Resistance

Acquired drug resistance to anticancer targeted therapies involving the APOBEC3 deaminases remains an unaddressed clinical challenge. However, there are studies reporting the association between the expression of particular members of the APOBEC3 family, and the development of drug resistance. In a recent study, it was shown that deletion of APOBEC3A reduces the number of mutations and the number of structural variations in persister cells and therefore delaying the development of drug resistance [

85]. Thus, the suppression of APOBEC3A activity may represent a potential therapeutic strategy to prevent or delay resistance to targeted therapies in lung cancer patients. Caswell et al. [

86] showed that APOBEC3B could also be a useful target to overcome NSCL immunotherapy drug resistance. APOBEC3B is known to promote tamoxifen resistance in estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer patients [

87]. Law et al. [

87] also showed that APOBEC3B depletion in an ER+ breast cancer cell line results in prolonged tamoxifen responses in these murine xenograft experiments. These and several other studies suggest that multiple APOBEC3 family members contribute to targeted therapy resistance and therefore might be inhibited to overcome drug resistance [

47,

85].

5.2.4. APOBEC3s and Cancer Progression

The first indication that changes in both adenosine and cytosine deaminase mutation signatures might be used to predict cancer progression was reported for a study of high-grade ovarian cancer (HGS-OvCa) in 2016 [

88]. It has since been observed that APOBEC3B expression in various cancers, including breast, lung, and cervical cancers leads to DNA mutations predicting progression [

89]. Evidence showing that mutational changes in tumor phylogenies are associated with cancer progression has also been reported [

57]. It is inferred from these studies, that at some stage during oncogenesis, some deaminases ‘self-edit’ and some activate alternate deaminase DBDs to generate the new mutation signatures observed. If these new DBD variants are linked to aggressive cancer, then they may become new therapeutic targets to suppress or slow cancer progression.

5.2.5. APOBEC3 Modulation Drug Development Approaches

It is evident that both APOBEC3-enhancing or APOBEC3-inhibiting drug development is already creating important new treatment options as early APOBEC3 deaminase modulation therapies develop.

Efforts to develop APOBEC3 small molecule inhibitors that target catalytic pockets of the APOBEC3s will help to guide the future design of inhibitors specific to each APOBEC enzyme [

90,

91]. Other potential strategies to reduce APOBEC3 activity include gene-silencing therapies and alternative splicing modulators [

92]. For APOBEC3A, a nucleic acid secondary structure has emerged as a factor in determining substrate targeting affinity, with a preference for ssDNA that forms stem loop hairpin structures. Serrano et al. [

93] used this knowledge to develop a nucleic acid-based inhibitor of APOBEC3A that showed specificity against APOBEC3A relative to the closely related catalytic domain of APOBEC3B. This work demonstrates the feasibility of leveraging secondary ssDNA structural preferences to design effective DNA inhibitors as potential therapeutics to inhibit APOBEC-driven viral and tumor evolution, and drug resistance. At the same time, we need to understand the clinical benefits of increasing APOBEC activity in cancers, particularly in the immunosuppressive hypoxic regions of tumors and to increase the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade therapy due to increased neoepitope presentation [

94].

6. Adenosine Deaminase Modulation

Dysregulation of ADAR1 and ADAR2 deaminase A-to-I editing is now implicated in a wide range of diseases, including immune and inflammatory illness, neurological conditions (including schizophrenia), viral infections, and cancers [

95,

96]. It is also important to note that ADAR1,2 expression levels are not always correlated with the editing frequency indicating that there is another layer of factors modulating the editing frequency of ADARs and hence influencing the accumulated cell damage [

97]. RNA editing can also modify some gene products without causing permanent changes in the genome and therefore has great potential in gene therapy [

98]. Understanding how these complex layers of differential ADAR modulation influence the course of human pathologies is important for the development of future adenosine modulation therapeutics.

6.1. ADAR1 Tumor Promotion

Mutations caused by ADAR1 have been implicated in oncogenesis by contributing to tumor development and progression in various cancers [

99,

100]. In an ADAR1 study of thyroid cancer patients it was found that inhibiting ADAR1 profoundly repressed proliferation, invasion, and migration in thyroid tumor cell models [

101].In an early thyroid cancer study, it was shown that the pharmacological inhibition of ADAR1 activity with 8-azaadenosine reduced cancer cell aggressiveness [102)]. However, it was subsequently found that 8-azaadenosine is not suitable for therapies that require selective inhibition of one ADAR isoform over another and may cause cellular toxicity likely due to broader disruptions in RNA metabolism [

103]. An interesting study by Wang X et al. [

104] has shown that the small-molecule ADAR1 inhibitor ZYS-1 can dramatically suppress prostate cancer cell growth and inhibit metastasis, and that it has a favorable safety profile. As most prostate cancer patients eventually relapse, these results identify ADAR1 as a potential druggable target using inhibition therapies such as ZYS-1. ADAR1 is also a potential druggable target in some breast cancers. Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are aggressive, chemotherapy-resistant, and have a poor prognosis. Baker et al. [

105]showed that ADAR1 loss in TNBC cells resulted in reduced growth, reduced invasion, and diminished mammosphere formation, implying that ADAR1 helps promote these aggressive behaviors in TNBC. Consistent with this view, Binothman et al. [

106] reported that ADAR1 is more abundantly expressed in invasive breast cancer (BC) tumors than in benign tumors.

Some studies have also identified ADAR1 as a potential druggable target to overcome resistance to therapy. In one study, it was shown that loss of ADAR1 in tumors overcomes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade [

107]. This study identified the possibility that ADAR1 inhibitors could restore melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5), mitochondrial antiviral-signaling (MAVS) protein and IFN (MDA5-MAVS-IFN) signaling and inflammatory responses in tumors and resurrect their response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. However, a study by Shiromoto et al. [108)]suggested that the suppression of ADAR1 editing activity also resulted in genome instability and apoptosis, particularly in non-alternate lengthening of telomeres (non-ALT) and telomerase-positive cancers that are 70–80% of all types of cancers. Shiromoto predicted that ADAR1 inhibitors could be an effective treatment for cancer patients as they interfere with two completely different pro-oncogenic functions: suppression of MDA5-MAVS-IFN signaling by the cytoplasmic ADAR1p150, and maintenance of telomere stability in telomerase-reactivated cancer cells by the nuclear ADAR1p110 [

108].

Dysregulation of the ADAR1 editing function has also been implicated in various autoimmune diseases. For instance, loss-of-function mutations in the ADAR1 gene are associated with Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS), a congenital autoimmune disorder [

109]. Loss of this ADAR1p150 function has been shown to cause embryonic lethality in ADAR1 null mice, the severe autoimmune disease AGS in humans, and has been associated with resistance to immune checkpoint blockade in cancers (108). Notably, ADAR1p150 not only binds right-handed (A-form) dsRNA, but also the left-handed Z-RNA duplex. Endogenous Z-RNAs arising from retroelements in mammalian genomes, if not edited and quenched by ADAR1p150, activate the innate immune sensor Z-NA Binding Protein 1 (ZBP1) and trigger ZBP1-dependent cell death. Such cell death drives autoimmunity in ADAR-deficient mice and may contribute to the development of AGS in humans. Other research indicates that adequate ADAR1 editing may serve as a defense mechanism against autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis [110)] Yet significant overexpression of ADAR1 was found in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) synovial tissue and in the blood of patients with active RA [

111] and suggesting that ADAR1 could be a potential therapeutic target. Elevated ADAR1 expression and heightened A-to-I RNA editing activity is also a prominent feature of progressing HCC [

112], gastric cancer [

113] and a significant subset of progressing lung adenocarcinomas [114)]

These examples underscore the importance of balancing A-to-I RNA editing in maintaining immune homeostasis and preventing unwanted oncogenic and autoimmune pathologies. The results also emphasize the potential applicability of ADAR1 inhibitors or ZBP1 agonists for several cancers.

6.2. ADAR2 Immunomodulation

Corresponding to the largely oncogenic role of ADAR1, there are now several studies reporting that ADAR2 plays a tumor-suppressive role in multiple cancers and in modulating the inflammatory responses.

In glioblastoma ADAR2 has been shown to slow progression by editing and modulating the function of the GLI1 gene (Glioma-Associated Oncogene Homolog 1) that is a transcription factor and a key component of the Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway, which plays a crucial role in cancer progression [

115]. Additionally, loss of ADAR2 in glioblastoma promotes tumor growth and resistance to therapy. In another glioblastoma study, restoration of ADAR2 editing activity has been shown to prevent tumor growth [

116]. Further, it has been shown that the rescue of ADAR2 activity in glioblastoma cancer cells recovers the edited micro-RNA (miRNA) population lost in glioblastoma cell lines and tissues and rebalances expression of onco-miRNAs and tumor suppressor miRNAs to the levels observed in normal human brain [

117]. Thus, ADAR2 largely reduces the expression of many miRNAs, most of which are onco-miRNAs. Similarly, in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), reduced levels of ADAR2 have been associated with poor prognosis as ADAR2 functions as a tumor suppressor in many cancers [

112,

113,

118], including in hepatocellular and gastric cancers. Given the poor prognosis for these cancers, the restoration or supplementation of ADAR2’s function could provide therapeutic benefit.

ADAR2 is also found to lower the risk of autoimmune diseases by playing an important role in modulating inflammatory responses and thus lowering the risk of autoimmune diseases. A study on Borna disease virus (BoDV) demonstrated that ADAR2 edits the viral RNA, allowing it to mimic 'self' RNA [

119]. This editing prevents the activation of innate immune responses. The study also showed that ADAR2-mediated RNA editing is essential for distinguishing self from non-self RNA and thereby reducing the risk of autoimmune responses. Deficient ADAR2 activity has been observed in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patients, resulting in improper GluA2 gene editing [

120]. These results are consistent with an earlier study reporting that mice lacking ADAR2 exhibit subsequent neurodegeneration [

121]. Such studies underscore ADAR2’s essential role in neuronal survival, and there have been several studies exploring ADAR2 supplementation. For instance, a hyperactive ADAR2 variant capable of enhanced editing at specific RNA motifs has been identified [

122]. Guide RNAs have also been designed to recruit endogenous ADAR2 to recode a loss-of-function mutation in the PINK1 gene associated with Parkinson's disease [

123]. This approach successfully restored PINK1 function in cellular models without introducing artificial proteins. Additionally, studies have shown that ADAR2 protein levels correlate with patient outcomes in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) [

124]. These studies highlight the therapeutic potential of ADAR2 supplementation and engineering in advancing the development of RNA-based therapies. However, as of now, there pre-clinical studies but no therapeutic interventions involving ADAR2 supplementation.

7. Harnessing the Power of Deaminase Modulation

There are a growing number of companies and research institutions that are part of a broader trend developing new biotechnologies to harness the power of deaminase modulation (

Table S1). While there are several Adenosine deaminase (ADA) and Cytidine deaminase (CDA) modulating drugs on the market with proven therapeutic benefit, these are targeting metabolic enzymes. Inosine dysregulation is implicated in many human diseases [

125] and they are included for reference.

Table S1 also includes some of the companies at the forefront of developing base editing tools. These rely upon the precise editing by cytidine or adenosine deaminase base editors to introduce targeted mutations without creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) like clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 does. Several promising base editing therapies are now advancing through clinical development. It is also likely that many other developments remain unpublished to prevent competitors from copying, or to secure patents. A key challenge for the approval of new deaminase modulation therapies is demonstrating the titration levels required to address deaminase imbalances.

8. Closing Remarks

A new area of drug development based on deaminase modulation is gaining traction because it has broad therapeutic application in oncology, immunology, virology, infectious diseases, neurology and gene editing. With ongoing clinical trials and rapid biotechnological advancements, this new era in drug development is likely to revolutionize genetic medicine. However, while several companies are already developing technologies and drugs that leverage the potential of deaminase modulation, we are still several years away from being able to deliver the wide range of promised therapeutic benefits. The fact that the deaminases are natural and highly targeted mutagenic enzymes that play crucial roles in immunity and the progression of all inflammation-linked diseases makes them powerful agents for forging this new frontier in drug development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

RAL is the sole author contributing to the conceptualization and writing of this article.

Funding

This paper is not funded from any external funding source.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the pre-submission reviews and editorial input by Dr Nathan E. Hall, Dr Jared Mamrot, Professor Rouf Banday, Professor Siddharth Balachandran and Assoc. Professor Edward J. Steele.

Conflicts of Interest

RAL is a co-founder and Director of GMDx Genomics and holds equity. She is also an inventor of patents relating to Targeted Somatic Mutation (TSM) methods and applications. She is an Hon. Principal Fellow at the Department of Clinical Pathology, University of Melbourne, a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

References

- Lindley, R. A. A review of the mutational role of deaminases and the generation of a cognate molecular model to explain cancer mutation spectra. Med. Res. Arch. 2020, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Gracia, K.; Gramalla-Schmitz, A.; Weischedel, J.; Chahwan, R. APOBECs orchestrate genomic and epigenomic editing across health and disease. Trends Genet. 2021, 37, 1028–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Pardo-Pastor, C.; Jenkins, R. G.; Rosenblatt, J. Imperfect wound healing sets the stage for chronic diseases. Science 2024, 386, eadp2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W. M.; Chevillotte, M. D.; Rice, C. M. Interferon-stimulated genes: A complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 513–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, E. J.; Lindley, R. A. Somatic mutation patterns in non-lymphoid cancers resemble the strand-biased somatic hypermutation spectra of antibody genes. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2010, 9, 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, E. J.; Lindley, R. A. Deaminase-driven reverse transcription mutagenesis in oncogenesis: Critical analysis of transcriptional strand asymmetries of single base substitution signatures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindley, R. A.; Hall, N. E. APOBEC and ADAR deaminases may cause many single nucleotide polymorphisms curated in the OMIM database. Mutat. Res. 2018, 810, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayona-Feliu, A.; Herrera-Moyano, E.; Badra-Fajardo, N.; Galvan-Femenia, I.; Soler-Oliva, E.; Aguilera, A. The chromatin network helps prevent cancer-associated mutagenesis at transcription-replication conflicts. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoy, H.; Zwicky, K.; Kuster, D.; Lang, K. S.; Krietsch, J.; Crossley, M. P.; Schmid, J. A.; Cimprich, K. A.; Merrikh, H.; Lopes, M. Direct visualization of transcription-replication conflicts reveals post-replicative DNA:RNA hybrids. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2023, 30, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindley, R. A.; Steele, E. J. ADAR and APOBEC editing signatures in viral RNA during acute-phase innate immune responses of the host-parasite relationship to Flaviviruses. Res. Rep. 2018, 2, e1–e22. [Google Scholar]

- Meshcheryakova, A.; Pietschmann, P.; Zimmermann, P.; Rogozin, I. B.; Mechtcheriakova, D. AID and APOBECs as multifaceted intrinsic virus-restricting factors: Emerging concepts in the light of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 690416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, A. J.; Birmingham, W. R.; Zhuo, Y.; Thorpe, T. W.; da Costa, B. Z.; Crawshaw, R.; Rowles, I.; Finnigan, J. D.; Young, C.; Holgate, G. M.; Muldowney, M. P.; Charnock, S. J.; Lovelock, S. L.; Turner, N. J.; Green, A. P. An engineered cytidine deaminase for biocatalytic production of a key intermediate of the COVID-19 antiviral molnupiravir. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 3761–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. S. Insights into the structures and multimeric status of APOBEC proteins involved in viral restriction and other cellular functions. Viruses 2021, 13, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2024 Global Hepatitis Report: Action for Access in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Baecker, A.; Liu, X.; La Vecchia, C.; Zhang, Z. F. Worldwide incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma cases attributable to major risk factors. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 27, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucifora, J.; Xia, Y.; Reisinger, F.; Zhang, K.; Stadler, D.; Cheng, X.; Sprinzl, M. F.; Koppensteiner, H.; Makowska, Z.; Volz, T.; Remouchamps, C.; Chou, W. M.; Thasler, W. E.; Hüser, N.; Durantel, D.; Liang, T. J.; Münk, C.; Heim, M. H.; Browning, J. L.; Dejardin, E.; Dandri, M.; Schindler, M.; Heikenwalder, M.; Protzer, U. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA. Science 2014, 343, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyushev, D.; Brezgin, S.; Kostyusheva, A.; Ponomareva, N.; Bayurova, E.; Zakirova, N.; Kondrashova, A.; Goptar, I.; Nikiforova, A.; Sudina, A.; Babin, Y.; Gordeychuk, I.; Lukashev, A.; Zamyatnin, A. A., Jr.; Ivanov, A.; Chulanov, V. Transient and tunable CRISPRa regulation of APOBEC/AID genes for targeting hepatitis B virus. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 32, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonvin, M.; Achermann, F.; Greeve, I.; Stroka, D.; Keogh, A.; Inderbitzin, D.; Candinas, D.; Sommer, P.; Wain-Hobson, S.; Vartanian, J. P.; Greeve, J. Interferon-inducible expression of APOBEC3 editing enzymes in human hepatocytes and inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication. Hepatology 2006, 43, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Z. Roles of APOBEC3 in hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and hepatocarcinogenesis. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 2074–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzko, L.; Hoffa-Sobiech, K.; Jackowiak, P.; Figlerowicz, M. Engineered deaminases as a key component of DNA and RNA editing tools. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 34, 102062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipić, B.; Ušjak, D.; Rambaher, M. H.; Oljacic, S.; Milenković, M. T. Evaluation of novel compounds as antibacterial or antivirulence agents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1370062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zeng, T.; Duan, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, C.; Liu, M.; Hu, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Yang, H. Optimized TadA variants improve cytidine-to-thymidine base editing efficiency and fidelity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4714. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, C. H.; Yeh, W. H.; Yeh, C. Y.; Lansky, S. M.; Qi, L.; Muneeruddin, K.; Park, J.; Soto, J.; Cadiñanos, J.; Ding, X.; Langner, L. M.; Mandegar, M. A.; Srifa, W.; Shen, M. W.; Keiser, M. S.; Tesar, P. J.; Gersbach, C. A.; Joung, J. K. Enhanced cytosine base editing by engineered TadA deaminases with minimized off-target effects. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 621–631. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Seija, N.; Di Noia, J. M.; Martin, A. AID in antibody diversification: There and back again. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muramatsu, M.; Kinoshita, K.; Fagarasan, S.; Yamada, S.; Shinkai, Y.; Honjo, T. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Nature 2000, 408, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revy, P.; Muto, T.; Levy, Y.; Geissmann, F.; Plebani, A.; Sanal, O.; Catalan, N.; Forveille, M.; Dufourcq-Labelouse, R.; Gennery, A.; Tezcan, I.; Ersoy, F.; Kayserili, H.; Ugazio, A. G.; Brousse, N.; Muramatsu, M.; Notarangelo, L. D.; Kinoshita, K.; Honjo, T.; Fischer, A.; Durandy, A. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2). Cell 2000, 102, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methot, S. P.; Di Noia, J. M. Molecular mechanisms of somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. Adv. Immunol. 2017, 133, 37–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J. K.; Alt, F. W.; Yeap, L. S. Related mechanisms of antibody somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, MDNA3–0037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, E. J.; Lindley, R. A.; Wen, J.; Weiller, G. F. Computational analyses show A-to-G mutations correlate with nascent mRNA hairpins at somatic hypermutation hotspots. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2006, 5, 1346–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, E. J.; Franklin, A.; Lindley, R. A. Somatic mutation patterns at Ig and non-Ig loci. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2024, 133, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Lv, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fan, L.; Yang, A. The off-target effects of AID in carcinogenesis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1221528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, L. A. S.; Cloete, B.; Mowla, S. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase: In sickness and in health. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 146, 2721–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Lieber, M. R. The RNA tether model for human chromosomal translocation fragile zones. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2024, 49, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbiani, D. F.; Nussenzweig, M. C. Chromosome translocation, B cell lymphoma, and activation-induced cytidine deaminase. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2013, 8, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, F. W.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, F. L.; Guo, C.; Schwer, B. Mechanisms of programmed DNA lesions and genomic instability in the immune system. Cell 2013, 152, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montamat-Sicotte, D.; Litzler, L. C.; Abreu, C.; Safavi, S.; Zahn, A.; Orthwein, A.; Müschen, M.; Oppezzo, P.; Muñoz, D. P.; Di Noia, J. M. HSP90 inhibitors decrease AID levels and activity in mice and in human cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2015, 45, 2365–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, S.; Mortusewicz, O.; Członka, E.; Freire, J.; Gütgemann, D.; Schuetz, M. L.; Dörk, B.; Leonhardt, H.; Barroso, V. R.; Niehrs, N. H. Restriction of AID activity and somatic hypermutation by PARP-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 7418–7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, L.; Duy, C.; Iacobucci, I.; Kuchen, S.; von Levetzow, G.; Feldhahn, N.; Henke, N.; Li, Z.; Hoffmann, T. K.; Kim, Y. M.; Hofmann, W. K.; Jumaa, H.; Groffen, J.; Heisterkamp, N.; Martinelli, G.; Lieber, M. R.; Casellas, R.; Muschen, M. The B cell mutator AID promotes B lymphoid blast crisis and drug resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J. J.; Manuel, C. A.; Barrett, C. V.; Raber, S.; Lucas, H.; Sutter, P.; Larijani, M. Catalytic pocket inaccessibility of activation-induced cytidine deaminase is a safeguard against excessive mutagenic activity. Structure 2015, 23, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Gonzalez, J.; Yasgar, A.; Maul, R. W.; Rieffer, A. E.; Crawford, D. J.; Salamango, D. J.; Dorjsuren, D.; Zakharov, A. V.; Jansen, D. J.; Rai, G.; Marugan, J.; Simeonov, A.; Harris, R. S.; Kohli, R. M.; Gearhart, R. J. Small molecule inhibitors of activation-induced deaminase decrease class switch recombination in B cells. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 1214–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Wu, W.; Li, X. Vaccine adjuvants: Mechanisms and platforms. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Honda-Okubo, Y.; Li, C.; Sajkov, D.; Petrovsky, N. Delta inulin adjuvant enhances plasmablast generation, expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase and B cell affinity maturation in human subjects receiving seasonal influenza vaccine. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toporovski, R.; Morrow, M. P.; Weiner, D. B. Interferons as potential adjuvants in prophylactic vaccines. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2010, 10, 1489–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Su, W.; Sanchez, D. J.; Mai, J. D. H.; Zhi, X.; Chen, H.; Ding, X. A self-assembled graphene oxide adjuvant induces both enhanced humoral and cellular immune responses in influenza vaccine. J. Control. Release 2024, 365, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, B.; Karami-Darehnaranji, M.; Mirzaei, E.; Karami, A. R.; Amirkhani, M. H.; Rahimi, A. R.; Nasab, M. J. Graphene oxide as a novel vaccine adjuvant. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 125, 111062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, H.; Mani, R.; Bhatnagar, R. Re-inventing traditional aluminum-based adjuvants: Insight into a century of advancements. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petljak, M.; Alexandrov, L. B.; Brammeld, J. S.; Price, S.; Wedge, D. C.; Grossmann, S.; Dawson, K. J.; Ju, Y. S.; Iorio, F.; Tubio, J. M. C.; Koh, C. C.; Georgakopoulos-Soares, I.; Rodríguez-Martín, B.; Otlu, B.; O’Meara, S.; Butler, A. P.; Menzies, A.; Bhosle, S. G.; Raine, K.; Jones, D. R.; Teague, J. W.; Beal, K.; Latimer, C.; O’Neill, L.; Zamora, J.; Anderson, E.; Patel, N.; Maddison, M.; Ng, B. L.; Graham, J.; Garnett, M. J.; McDermott, U.; Nik-Zainal, S.; Campbell, P. J.; Stratton, M. R. Characterizing mutational signatures in human cancer cell lines reveals episodic APOBEC mutagenesis. Cell 2019, 176, 1282–1294.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieber, M. R. Mechanisms of human lymphoid chromosomal translocations. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynaud, C. A.; Weill, J. C. Predicting AID off-targets: A step forward. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W. AID in reprogramming: Quick and efficient. Identification of a key enzyme called AID, and its activity in DNA demethylation, may help to overcome a pivotal epigenetic barrier in reprogramming somatic cells toward pluripotency. Bioessays 2010, 32, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, E.L.; Papavasiliou, F.N. Cytidine deaminases: AIDing DNA demethylation? Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, P.M.; Shaknovich, R. Epigenetic function of activation-induced cytidine deaminase and its link to lymphomagenesis. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, M.; Lv, Z.; Odhiambo, W.; Yu, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, C.; Ma, Y.; Ji, Y. AID and TET2 co-operation modulates FANCA expression by active demethylation in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2019, 195, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohri, T.; Nagata, K.; Kuwamoto, S.; Matsushita, M.; Sugihara, H.; Kato, M.; Horie, Y.; Murakami, I.; Hayashi, K. Aberrant expression of AID and AID activators of NF-κB and PAX5 is irrelevant to EBV-associated gastric cancers, but is associated with carcinogenesis in certain EBV-non-associated gastric cancers. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 4133–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, A.; Jin, L.; Nara, H.; Takeda, Y.; Nemoto, N.; Gazi, M.Y.; Asao, H. IL-21 enhances the development of colitis-associated colon cancer: Possible involvement of activation-induced cytidine deaminase expression. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 3326–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Liao, Q.; Qiu, X. Immunoglobulin expression in cancer cells and its critical roles in tumorigenesis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 613530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petljak, M.; Dananberg, A.; Chu, K.; Bergstrom, E.N.; Striepen, J.; von Morgen, P.; Chen, Y.; Shah, H.; Sale, J.E.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Stratton, M.R.; Maciejowski, J. Mechanisms of APOBEC3 mutagenesis in human cancer cells. Nature 2022, 607, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vile, R.G.; Melcher, A.; Pandha, H.; Harrington, K.; Gunn, G.; Fruehauf, S.; Rampling, S.; Kaufman, J.; Gough, M.; Russell, S.J. APOBEC and cancer viroimmunotherapy: Thinking the unthinkable. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 3280–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, K.; Banday, A.R. APOBEC3-mediated mutagenesis in cancer: Causes, clinical significance and therapeutic potential. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Zhu, L.; Huang, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, H.; Nong, B.; Xiong, Y. APOBEC alteration contributes to tumor growth and immune escape in pan-cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.; Lv, M.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, G.; Cui, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. APOBEC3B expression and its prognostic potential in breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 19, 3205–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMarco, A.V.; Qin, X.; McKinney, B.J.; Garcia, N.M.G.; Van Alsten, S.C.; Mendes, E.A.; Force, J.; Hanks, B.A.; Troester, M.A.; Owzar, K.; Xie, J.; Alvarez, J.V. APOBEC mutagenesis inhibits breast cancer growth through induction of T cell-mediated antitumor immune responses. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2022, 10, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaoka, M.; Patnaik, S.K.; Ishikawa, T.; Takabe, K. Different members of the APOBEC3 family of DNA mutators have opposing associations with the landscape of breast cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 5111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glaser, A.P.; Fantini, D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Rimar, K.J.; Podojil, J.R.; Miller, S.D.; Meeks, J.J. APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis in urothelial carcinoma is associated with improved survival, mutations in DNA damage response genes, and immune response. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 4537–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhao, T.; Trapp, C.; Wang, X.; Unger, K.; Zhou, C.; Lu, S.; Buchner, A.; Schulz, G.B.; Cao, F.; Belka, C.; Su, C.; Li, M.; Shu, Y. APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis is a favorable predictor of prognosis and immunotherapy for bladder cancer patients: Evidence from pan-cancer analysis and multiple databases. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4181–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jia, M.; He, Z.; Liu, X.S. APOBEC3B and APOBEC mutational signature as potential predictive markers for immunotherapy response in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2018, 37, 3924–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chong, W.; Teng, C.; Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X. The immune response related mutational signatures and driver genes in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 2348–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüder, U.; Denkert, C.; Kunze, C.A.; Jank, P. APOBEC3B protein expression and mRNA analyses in patients with high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Histol. Histopathol. 2019, 34, 405–417. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, S.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.Y.; Cheng, X.X.; Li, J.; Hu, Y.X. Immune inactivation by APOBEC3B enrichment predicts response to chemotherapy and survival in gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 1975386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Patnaik, S.K.; Kemer, Z.; Baysal, B.E. Transient overexpression of exogenous APOBEC3A causes C-to-U RNA editing of thousands of genes. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamrot, J.; Balachandran, S.; Steele, E.J.; Lindley, R.A. Molecular model linking Th2 polarized M2 tumour-associated macrophages with deaminase-mediated cancer progression mutation signatures. Scand. J. Immunol. 2019, 89, e12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqassim, E.Y.; Sharma, S.; Khan, A.N.M.N.H.; Emmons, T.R.; Cortes Gomez, E.; Alahmari, A.; Singel, K.L.; Mark, J.; Davidson, B.A.; McGray, A.J.R.; Liu, Q.; Lichty, B.D.; Moysich, K.B.; Wang, J.; Odunsi, K.; Segal, B.H.; Baysal, B.E. RNA editing enzyme APOBEC3A promotes pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage polarization. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Zheng, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, M. Effect of APOBEC3A functional polymorphism on renal cell carcinoma is influenced by tumor necrosis factor-α and transcriptional repressor ETS1. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 4347–4363. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, B. ADAR1-mediated RNA editing and its role in cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 956649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, S.B.; Ma, T.S.; Simpson, C.J.; Liang, J.; Maezono, S.E.B.; Olcina, M.M.; Buffa, F.M.; Hammond, E.M. Replication catastrophe induced by cyclic hypoxia leads to increased APOBEC3B activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 7492–7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, M.J.; Jones, K.F.M.; Carpenter, A.M.; Harris, R.S.; Harki, D.A. The current toolbox for APOBEC drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.; Budagyan, K.; Hayer, K.E.; Reed, M.A.; Savani, M.R.; Wertheim, G.B.; Weitzman, M.D. Cytosine deaminase APOBEC3A sensitizes leukemia cells to inhibition of the DNA replication checkpoint. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 4579–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buisson, R.; Lawrence, M.S.; Benes, C.H.; Zou, L. APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B activities render cancer cells susceptible to ATR inhibition. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 4567–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkilä, J.; Kumar, R.; Campbell, J.; Brandsma, I.; Pemberton, H.N.; Wallberg, F.; Nagy, K.; Scheer, I.; Vertessy, B.G.; Serebrenik, A.A.; Monni, V.; Harris, R.S.; Pettitt, S.J.; Ashworth, A.; Lord, C.J. Elevated APOBEC3B expression drives a kataegic-like mutation signature and replication stress-related therapeutic vulnerabilities in p53-defective cells. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wörmann, S.M.; Zhang, A.; Thege, F.I.; Specht, C.D.; Gordon, J.A.; Wallace, M.N.; Ocañas, M.G.; Schenk, M.S.; Chung, D.H.; Morton, J.P.; Ying, H.; Vonderheide, R.H.; Klein-Szanto, A.M.P.; Stanger, B.Z. APOBEC3A drives deaminase domain-independent chromosomal instability to promote pancreatic cancer metastasis. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 1338–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiki, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sueta, A.; Yamamoto-Ibusuki, M.; Goto-Yamaguchi, L.; Tomiguchi, M.; Takeshita, T.; Iwase, H. APOBEC3B gene expression as a novel predictive factor for pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 30513–30526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Dong, X.; Yang, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Zhou, L. Comparative analysis of differentially mutated genes in non-muscle and muscle-invasive bladder cancer in the Chinese population by whole exome sequencing. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 831146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafarpour, S.; Yazdi, M.; Nedaeinia, R.; Ghobakhloo, S.; Salehi, R. Unfavorable prognosis and clinical consequences of APOBEC3B expression in breast and other cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2022, 44, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Liu, P.; Cui, S.; Gao, C.; Tan, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, R. The identification of APOBEC3G as a potential prognostic biomarker in acute myeloid leukemia and a possible drug target for crotonoside. Molecules 2022, 27, 5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isozaki, H.; Sakhtemani, R.; Abbasi, A.; Nikpour, N.; Stanzione, M.; Oh, S.; Langenbucher, A.; Monroe, S.; Su, W.; Cabanos, H.F.; et al. Therapy-induced APOBEC3A drives evolution of persistent cancer cells. Nature 2023, 620, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell, D.R.; Gui, P.; Mayekar, M.K.; Law, E.K.; Pich, O.; Bailey, C.; Boumelha, J.; Kerr, D.L.; Blakely, C.M.; Manabe, T.; et al. The role of APOBEC3B in lung tumor evolution and targeted cancer therapy resistance. Nat. Genet. 2024, 56, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, E.K.; Sieuwerts, A.M.; LaPara, K.; Leonard, B.; Starrett, G.J.; Molan, A.M.; Temiz, N.A.; Vogel, R.I.; Meijer-van Gelder, M.E.; Sweep, F.C.G.J.; et al. The DNA cytosine deaminase APOBEC3B promotes tamoxifen resistance in ER-positive breast cancer. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, R.A.; Humbert, P.; Larner, C.; Akmeemana, E.H.; Pendlebury, C.R. Association between targeted somatic mutation (TSM) signatures and HGS-OvCa progression. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 2629–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Sun, Y.; Yan, H.; Xie, L.; Zhang, Z. APOBEC3B, a molecular driver of mutagenesis in human cancers. Cell Biosci. 2017, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.E.; Li, M.; Harris, R.S.; Harki, D.A. Small-molecule APOBEC3G DNA cytosine deaminase inhibitors based on a 4-amino-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol scaffold. ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.J.; Borzooee, F.; Im, J.; Asgharpour, M.; Ghorbani, A.; Diamond, C.P.; Fifield, H.; Berghuis, L.; Larijani, M. Structure-based design of first-generation small molecule inhibitors targeting the catalytic pockets of AID, APOBEC3A, and APOBEC3B. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 1390–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvach, M.V.; Barzak, F.M.; Harjes, S.; Schares, H.A.M.; Jameson, G.B.; Ayoub, A.M.; Moorthy, R.; Aihara, H.; Harris, R.S.; Filichev, V.V.; Harki, D.A.; Harjes, E. Inhibiting APOBEC3 activity with single-stranded DNA containing 2′-deoxyzebularine analogues. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.C.; VonTrentini, D.; Berrios, K.N.; Barka, A.; Dmochowski, I.J.; Kohli, R.M. Structure-guided design of a potent and specific inhibitor against the genomic mutator APOBEC3A. ACS Chem. Biol. 2022, 17, 3379–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, C.B.; Schuelke, M.R.; Kottke, T.; Thompson, J.M.; Wongthida, P.; Tonne, J.M.; Huff, A.L.; Miller, A.; Shim, K.G.; Molan, A.; et al. APOBEC3B-mediated corruption of the tumor cell immunopeptidome induces heteroclitic neoepitopes for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Okada, S.; Sakurai, M. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing in neurological development and disease. RNA Biol. 2021, 18, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Shiromoto, Y.; Minakuchi, M.; Nishikura, K. The role of RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 in human disease. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2022, 13, e1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khermesh, K.; D’Erchia, A.M.; Barak, M.; Annese, A.; Wachtel, C.; Levanon, E.Y.; Picardi, E.; Eisenberg, E. Reduced levels of protein recoding by A-to-I RNA editing in Alzheimer’s disease. RNA 2016, 22, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, H.G.; Matos, V.J.; Park, S.; Pham, K.M.; Beal, P.A. Selective inhibition of ADAR1 using 8-azanebularine-modified RNA duplexes. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 1376–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ji, W.; Zhao, J.; Song, J.; Zheng, S.; Chen, L.; Li, P.; Tan, X.; Ding, Y.; Pu, R.; et al. Transcriptional repression and apoptosis influence the effect of APOBEC3A/3B functional polymorphisms on biliary tract cancer risk. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 150, 1825–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.R.; Slack, F.J. ADAR1 and its implications in cancer development and treatment. Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Moya, J.; Baker, A.R.; Slack, F.J.; Santiseban, P. ADAR1-mediated RNA editing is a novel oncogenic process in thyroid cancer and regulates miR-200 activity. Oncogene 2020, 39, 3738–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, D.; Gacquer, D.; Rothe, F.; Lefort, A.; Libert, F.; Brown, D.; Kheddoumi, N.; Shlien, A.; Konopka, T.; Salgado, R.; et al. Principles governing A-to-I RNA editing in the breast cancer transcriptome. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottrell, K.A.; Torres, L.S.; Dizon, M.G.; Weber, J.D. 8-Azaadenosine and 8-chloroadenosine are not selective inhibitors of ADAR. Cancer Res. Commun. 2021, 1, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, L.; Fang, M.; Zhao, H.; Xu, W.; Liu, Z. Targeting ADAR1 with a small molecule for the treatment of prostate cancer. Nat. Cancer 2025, xx, xxx–xxx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.R.; Miliotis, C.; Ramírez-Moya, J.; Marc, T.; Vlachos, I.S.; Santisteban, P.; Slack, F.J. Transcriptome profiling of ADAR1 targets in triple-negative breast cancer cells reveals mechanisms for regulating growth and invasion. Mol. Cancer Res. 2022, 20, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binothman, N.; Aljadani, M.; Alghanem, B.; Refai, M.Y.; Rashid, M.; Al Tuwaijri, A.; Alsubhi, N.H.; Alrefaei, G.I.; Khan, M.Y.; Sonbul, S.N.; et al. Identification of novel interact partners of ADAR1 enzyme mediating the oncogenic process in aggressive breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizuka, J.J.; Manguso, R.T.; Cheruiyot, C.K.; Ki, B.; Panda, A.; Iracheta-Vellve, A.; Miller, B.C.; Du, P.P.; Yates, K.B.; Dubrot, J.; et al. Loss of ADAR1 in tumours overcomes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature 2019, 565, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiromoto, Y.; Sakurai, M.; Minakuchi, M.; Ariyoshi, K.; Nishikura, K. ADAR1 RNA editing enzyme regulates R-loop formation and genome stability at telomeres in cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakahama, T.; Kawahara, Y. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing in the immune system: Friend or foe? Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2931–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tossberg, J.T.; Heinrich, R.M.; Farley, V.M.; Alexander, E.J.; Meeks, C.S.; Levin, A.S.; Cooper, T.R. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing of Alu double-stranded RNAs is markedly decreased in multiple sclerosis and unedited Alu dsRNAs are potent activators of proinflammatory transcriptional responses. J. Immunol. 2020, 205, 2606–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachogiannis, N.I.; Gatsiou, A.; Silvestris, D.A.; Sachse, E.; Stellos, T.; Bochenek, J.; Ayers, J.R.; Smith, J.L.; Dimmeler, J.M.; Engelhardt, J.F. RNA modifications in autoimmunity: The epitranscriptome in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 106, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.H.; Lin, C.H.; Qi, L.; Fei, J.; Li, Y.; Yong, Y.K.J.; Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Chow, R.K.; Ng, V.H.; et al. A disrupted RNA editing balance mediated by ADARs (adenosine deaminases that act on RNA) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2014, 63, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.H.; Qamra, A.; Tan, K.T.; Guo, J.; Yang, H.; Qi, L.; Lin, J.S.; Ng, V.H.; Song, Y.; Hong, H.; et al. ADAR-mediated RNA editing predicts progression and prognosis of gastric cancer. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 637–650.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, E.M.; Liu, Y.; Deng, S.; Tan, K.S.; Chudgar, N.; Mayo, M.W.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Adusumilli, P.S.; Schultz, N.; Jones, D.R. The RNA-editing enzyme ADAR promotes lung adenocarcinoma migration and invasion by stabilizing FAK. Sci. Signal. 2017, 10, eaah3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawa, T.; Rahman, M.F.-U.; Tostar, U.; Sonkoly, E.; Ståhle, M.; Pivarcsi, A.; Palaniswamy, R.; Zaphiropoulos, P. RNA editing of the GLI1 transcription factor modulates the output of Hedgehog signaling. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, xxx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, F.; Rossetti, C.; Tomaselli, S.; Cifaldi, L.; Lezzerini, M.; Pezzullo, M.; Boldrini, R.; Massimi, L.; Di Rocco, C.M.; Locatelli, F.; et al. ADAR2-editing activity inhibits glioblastoma growth through the modulation of the CDC14B/Skp2/p21/p27 axis. Oncogene 2013, 32, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, S.; Galeano, F.; Alon, S.; Raho, R.; Galardi, E.; Polito, F.; de Santis, R.; Gallo, C.A.; Picardi, F.L.; Avolio, M.A.; et al. Modulation of microRNA editing, expression, and processing by ADAR2 deaminase in glioblastoma. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Mendoza, J.J.; Sun, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.Z.; Zhou, X.; Wu, Z.Y. Advances in A-to-I RNA editing in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, M.; Kojima, S.; Sakai, M.; Asano, S.; Nakamura, T.; Takeda, M.; Ikeda, Y.; Yokota, K.; Shirogane, T. ADAR2 is involved in self and nonself recognition of Borna disease virus genomic RNA in the nucleus. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01513–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, H.; Hideyama, T.; Yamashita, T.; Kimura, T.; Suzuki, N.; Aoki, M.; Kwak, S. Deficient RNA-editing enzyme ADAR2 in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient with a FUS(P525L) mutation. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 32, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.; Vissel, B. The essential role of AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit RNA editing in the normal and diseased brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2012, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katrekar, D.; Xiang, Y.; Palmer, N.; Saha, A.; Meluzzi, D.; Mali, P. Comprehensive interrogation of the ADAR2 deaminase domain for engineering enhanced RNA editing activity and specificity. eLife 2022, 11, e75555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wettengel, J.; Reautschnig, P.; Geisler, S.; Kahle, P.J.; Stafforst, T. Harnessing human ADAR2 for RNA repair—Recoding a PINK1 mutation rescues mitophagy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 2797–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesarini, V.; Silvestris, D.A.; Galeano, F.; Tassinari, V.; Martini, M.; Locatelli, F.; Gallo, A. ADAR2 protein is associated with overall survival in GBM patients and its decrease triggers the anchorage-independent cell growth signature. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.S.; Jo, E.K. Inosine: A bioactive metabolite with multimodal actions in human diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1043970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).