1. Introduction

Shoulder injuries are among the most prevalent musculoskeletal conditions in tennis players, largely due to the repetitive overhead movements required by the sport. These demands, combined with the asymmetrical nature of tennis, often lead to muscular imbalances, particularly within the shoulder complex.

Symmetric and asymmetric sports differ markedly in their neuromuscular demands. While symmetric sports involve coordinated bilateral activation, asymmetric sports such as tennis impose a unilateral load, with most technical actions executed by the dominant arm [

1]. This preferential use promotes interlimb asymmetries and neuromuscular imbalances [

2], including bilateral strength deficits and disproportionate force production between agonist and antagonist muscles [

3]. Together with reduced muscular endurance and technical inefficiencies, these adaptations increase the risk of overuse injuries in the glenohumeral joint [

4].

Although many studies have analysed the mechanisms of these adaptations, evidence-based preventive protocols for mitigating neuromuscular asymmetries remain limited. Current strategies emphasise the activation of interscapular muscles, which are essential for maintaining glenohumeral alignment [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The middle and lower trapezius are particularly important, as they stabilise the scapula through upward rotation, retraction, and posterior tilt during overhead actions [

9,

10]. Insufficient activation of these muscles can result in weakness, altered length–tension relationships, and impaired scapulothoracic force couples [

11].

However, there is no clear consensus on the most effective strategies to selectively strengthen these muscles. Exercises involving glenohumeral abduction or rowing between 90° and 150° of elevation elicit high activation of the lower trapezius [

12], while elevation aligned with its anatomical orientation (~145°) has also been suggested [

13]. Both approaches, however, often lead to upper trapezius co-activation, limiting selective recruitment [

14]. Furthermore, much of this evidence is dated, underscoring the need for updated studies using surface electromyography (sEMG) under unilateral conditions.

Elastic resistance bands have become popular in rehabilitation and injury prevention, though only a few studies have assessed their application in tennis. Some evidence indicates improvements in range of motion, serve speed, and accuracy, but most findings come from other overhead sports such as swimming, volleyball, and handball [

6,

7,

15,

16,

17]. Given the explosive and rotational nature of tennis strokes, these results cannot be directly extrapolated. Thus, there is a need for sport-specific studies assessing the role of elastic resistance in shoulder injury prevention [

5,

18,

19].

Additionally, many protocols are based on the mechanics of baseball pitchers, overlooking biomechanical differences between sports. Exercises proven effective in one discipline may not be equally appropriate in another. This limitation is relevant considering that tennis is widely practiced and associated with a high prevalence of injuries linked to muscular imbalances [

20,

21,

22].

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate trapezius muscle activation and asymmetry during unilateral shoulder retraction exercises with elastic resistance bands in tennis and non-tennis athletes, with the hypothesis that tennis players would exhibit greater interlimb asymmetry and reduced selective activation of the lower trapezius, while elastic resistance would enhance overall scapular stabiliser activation compared with exercises performed without resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A randomized, repeated-measures cross-sectional between-group design was employed. The study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE reporting guidelines [

23]

.

2.2. Study Population

This study included a total of 39 athletes from various sports disciplines. Specifically, 16 participants (41%) were identified as active tennis players, thereby representing the most prevalent sport within the sample. The remaining participants were involved in a variety of sports, including soccer (n = 8; 20.5%), athletics (n = 2; 5.1%), futsal (n = 2; 5.1%), and one participant each (2.6%) engaged in triathlon, basketball, swimming, artistic gymnastics, judo, pole vaulting, dance, calisthenics, duathlon, and gym-based training. For analytical purposes, participants were categorized into two distinct groups: Tennis Players (TP) group, comprising 16 athletes who actively practice tennis, and the Non–Tennis Players (N–TP) group, including 23 athletes who do not participate in tennis. Both groups underwent identical physical assessments, and subsequent analyses were conducted to identify potential differences between them.

Demographic, anthropometric, and descriptive variables were collected in accordance with standardized anthropometric protocols to ensure both accuracy and reliability (

Table 1). These data were initially obtained through a self-reported questionnaire and subsequently verified during the assessment phase. Furthermore, all participants were free from any pain or musculoskeletal pathology that could compromise their ability to perform shoulder external rotation exercises.

All participants met the inclusion criteria (

Table 2) and received both written and verbal explanations of the study procedures before the assessment session. After being provided with detailed information, each participant signed an informed consent form in accordance with the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki by the World Medical Association (2013) [

24].

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcome measures analysed in this study included the Root Mean Square (RMS) (µV), the Mean Maximum Amplitude (µV) of three repetitions, and muscle symmetry (%). The Muscle Symmetry Index was used to quantify the similarity in muscle activity between two muscles, categorized as follows: asymmetrical (0–79% similarity), borderline (80–89% similarity), and normal/symmetrical (90–100%) [

25].

These variables were specifically examined in the lower and middle trapezius muscles on both the right and left sides, considering each player's dominant side for a more precise evaluation of muscle asymmetry and its potential impact on performance.

Electromyographic (EMG) data were recorded using the mDurance® system (mDurance® Solutions SL, Granada, Spain), which integrates the EMG Shimmer3 unit (Realtime Technologies Ltd., Dublin, Ireland). The mDurance® system utilizes a validated surface EMG methodology designed for accurate muscle activation assessment. This advanced system combines user-friendly software with lightweight hardware, making it practical and accessible for both clinical and sports performance applications. The Shimmer3 unit within the system is a bipolar surface EMG sensor specifically designed for precise muscle activity acquisition. Each unit features two recording channels, a sampling frequency of 1024 Hz, a bandwidth of 8.4 Hz, and 24-bit resolution, with a signal amplification range of 100 to 10,000 V/V. This configuration ensures high-quality data capture for detailed analysis. The reliability and validity of the mDurance® system in recording muscle activity during functional tasks have been well established in prior research, showing excellent intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC = 0.916; 95% CI = 0.831−0.958) [

26]. These features make the system an invaluable tool for researchers and practitioners assessing neuromuscular performance in real-world settings. The mDurance Android app received data from the Shimmer3 unit and transmitted it to a cloud service, where the data were stored, filtered, and analysed [

26].

During exercise execution, both the participant and the therapist could observe real-time graphs of muscle activation and joint mobility, facilitating a self-correction biofeedback model. Furthermore, a final performance report was generated to provide comprehensive insights into the assessment outcomes (

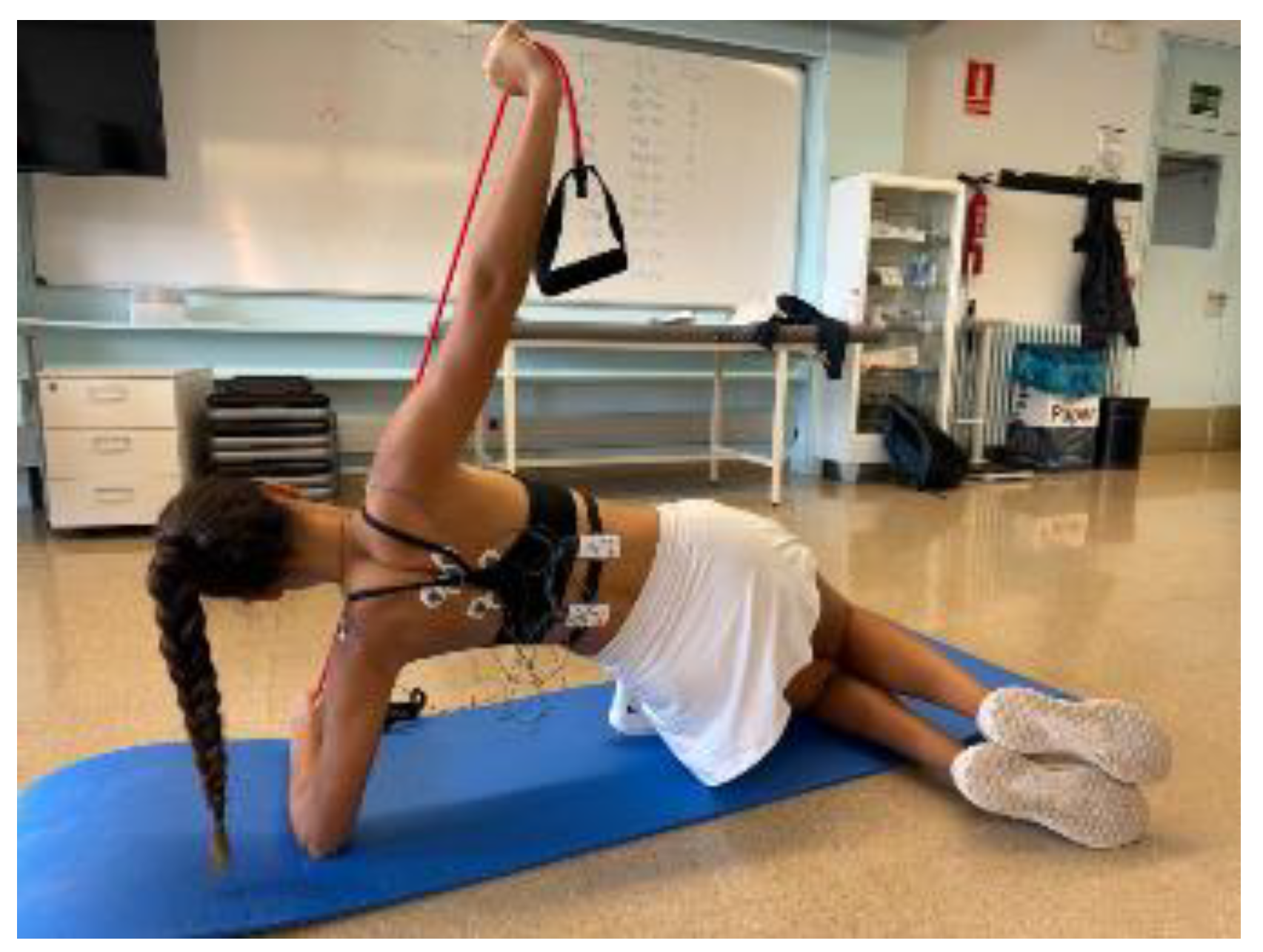

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Exercise: Left Side Plank (LSP) with resistance band at 90°.

Figure 1.

Exercise: Left Side Plank (LSP) with resistance band at 90°.

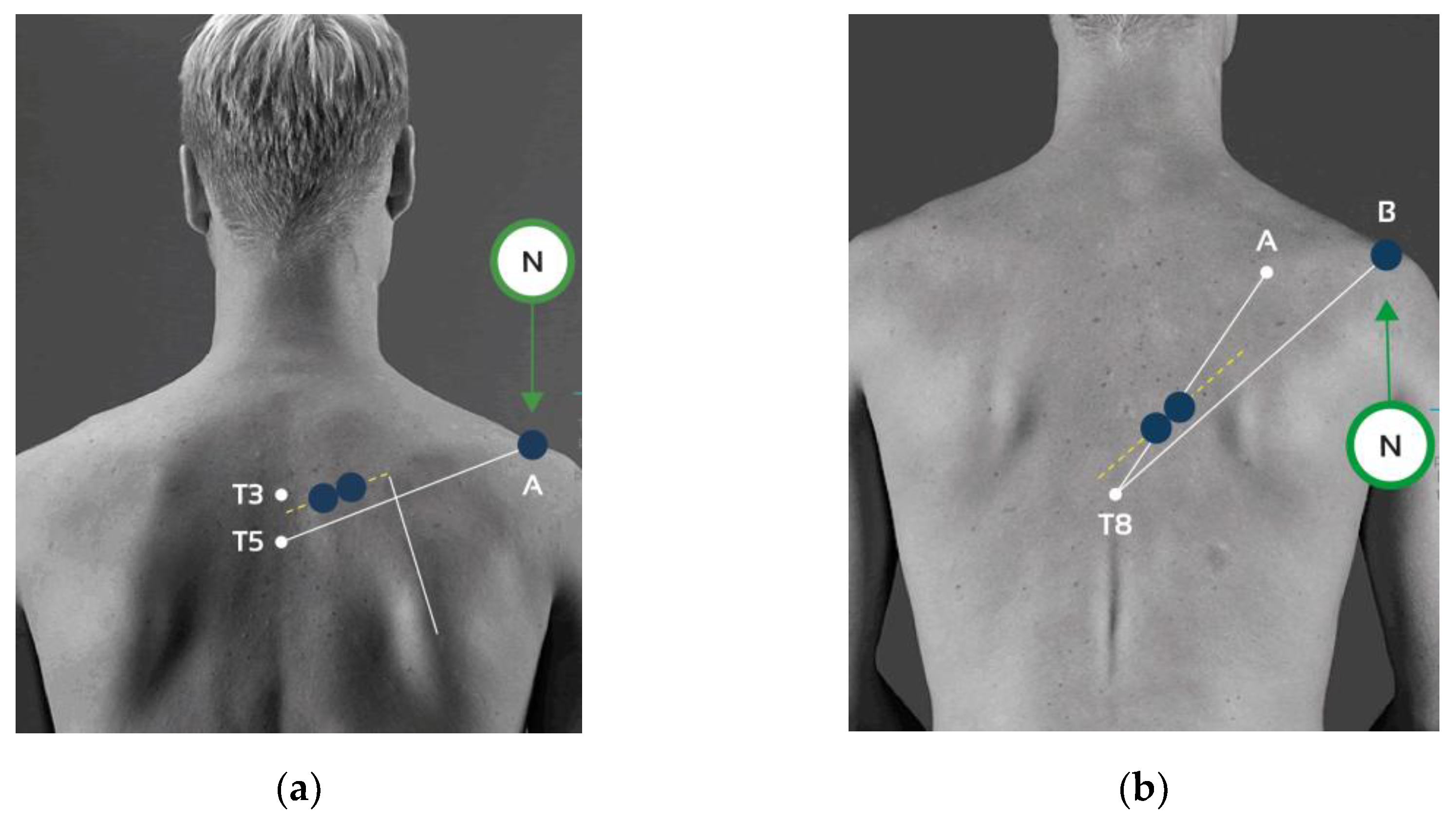

Figure 2.

Electrodes placement: (a) Middle trapezius (MT): The electrode was positioned between the spinous processes of the third (T3) and fifth (T5) thoracic vertebrae, following the orientation defined by the line connecting T5 and the acromion (Line A–T5). A reference (neutral) electrode was placed on the surface of the acromion. (b) Lower trapezius (LT): The electrode was placed following the anatomical line extending from the trigonum spinae to the spinous process of the eighth thoracic vertebra (T8) (Line A–T8). An additional alignment was defined by the line connecting T8 and the acromion (Line B–T8). The neutral electrode was consistently located on the acromion surface.

Figure 2.

Electrodes placement: (a) Middle trapezius (MT): The electrode was positioned between the spinous processes of the third (T3) and fifth (T5) thoracic vertebrae, following the orientation defined by the line connecting T5 and the acromion (Line A–T5). A reference (neutral) electrode was placed on the surface of the acromion. (b) Lower trapezius (LT): The electrode was placed following the anatomical line extending from the trigonum spinae to the spinous process of the eighth thoracic vertebra (T8) (Line A–T8). An additional alignment was defined by the line connecting T8 and the acromion (Line B–T8). The neutral electrode was consistently located on the acromion surface.

2.4. Procedure

Following the collection of participants’ descriptive information via a structured questionnaire and the subsequent classification into tennis players (TP) and non–tennis players (N–TP), the experimental protocol proceeded with the standardized placement of surface electromyography (sEMG) electrodes.

Electrode Placement

All participants underwent skin preparation for EMG recording, which included shaving, scrubbing, and cleaning the skin with alcohol to minimize impedance (<10kΩ) [

10]. Surface EMG electrodes were then placed over the muscle bellies, aligned with the muscle-fibbers orientation, for the following muscles: lower trapezius right (LTR), lower trapezius left (LTL), middle trapezius right (MTR), and middle trapezius left (MTL). Self-adhesive 5 cm Dormo surface electrodes were positioned on the muscle belly following the recommendations of the SENIAM project [

27], maintaining an interelectrode distance of 20 mm (

Table 3).

2.5. Experimental Procedure

Participants executed one exercise outlined in the study protocol to analyze the activation patterns of the interscapular musculature during their performance and progression. Prior to each assessment session, participants were advised to avoid engaging in high-intensity physical activity for at least 24 hours.

2.5.1. Recording Muscle Activity

Participants completed the specific exercise included in the study protocol to evaluate the activation patterns of the interscapular musculature during execution and progression. Surface electrodes were bilaterally positioned over the middle and lower trapezius muscles, allowing for simultaneous muscle activity recording. Each testing session lasted approximately 10 minutes per exercise and per participant, which included the time allocated for electrode placement. All procedures were non-invasive, posed no risk to the participants, and did not entail any financial cost. Moreover, the use of surface electromyography ensured a comfortable experience, while the experimental setup allowed participants to execute the movements freely and without restriction.

Participants were instructed to refrain from high-intensity exercise for 24 hours prior to both test sessions.

Each individual completed the exercise, with a maximum duration of 10 minutes, including electrode placement. The assessments posed no particular risk to participants, and all tests were conducted at no cost. Surface electromyography, which is non-invasive and does not cause discomfort, was used, and the wires allowed for unrestricted movement.

Study members received detailed instructions on the correct execution of the exercise. They performed a series of three contractions, followed by a one-minute rest period. The primary objective of the exercises was to promote scapular retraction during each contraction while coordinating with breathing. Participants were instructed to inhale while performing scapular retraction simultaneously. This intervention aimed to enhance muscle function in the scapular region, ensuring proper alignment and optimizing biomechanical performance in functional activities.

2.5.2. Exercise

The first exercise involved a side-lying external rotation movement with elastic resistance, designed to emphasize scapular stability, external rotator activation, and core engagement. Participants were positioned in a side-lying posture on a mat, with the lower arm supporting the head and the knees slightly flexed to maintain balance. The upper arm held a resistance band, anchored under the lower arm or body, with the elbow flexed at approximately 90° and the shoulder positioned in slight abduction.

Prior to the initiation of electromyographic recording, participants performed a maximal scapular retraction to determine the appropriate loop tension for each individual. A multi-loop resistance band (Flexvit Multi, Flexvit Bands, Germany) was utilized, with the loops individually adjusted to each participant’s wingspan to optimize the range of motion and facilitate maximal scapular adduction.

During the concentric phase, participants executed shoulder external rotation by raising the hand upward while maintaining elbow alignment and scapular stability, synchronized with a deep inhalation. In the eccentric phase, the forearm was lowered in a controlled manner during exhalation, ensuring continuous activation of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers. The exercises were initially performed at a 90° angle, followed by execution at 45°. Consistent with the previous protocol, assessments were conducted first at 90°, followed by 45°.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of the factors Angle (45° vs 90°), Side (dominant vs non-dominant), and Muscle, as well as their interactions, on the dependent variable. Player Type was included as a between-subjects factor.

3. Results

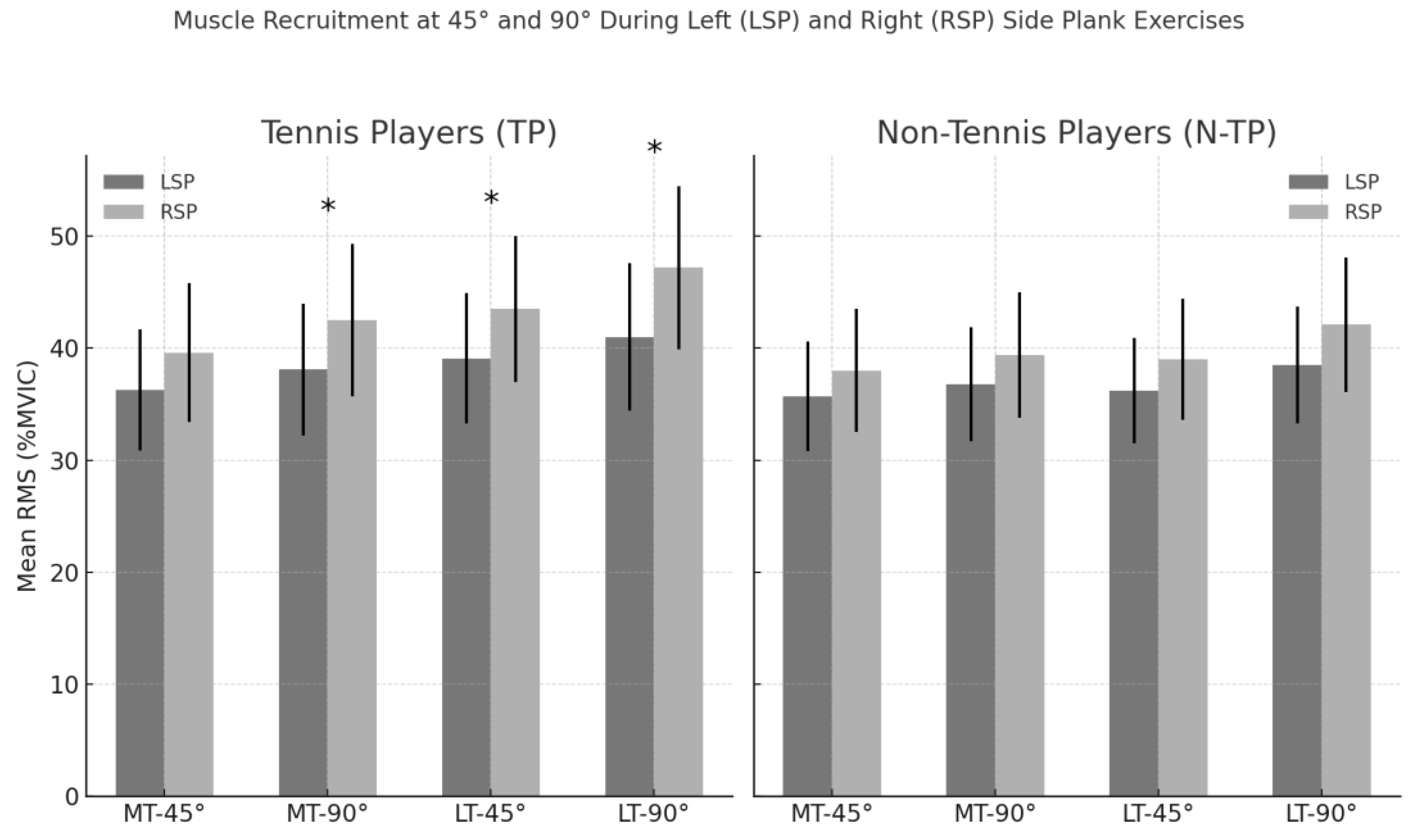

3.1. Muscle Recruitment During Right and Left Side Plank at 90° and 45°

At 90° of shoulder abduction, non-tennis players exhibited greater activation of the middle trapezius on the dominant side (p=0.002), whereas tennis players showed higher activation of the middle trapezius on the non-dominant side (p=0.005).For the lower trapezius, tennis players demonstrated greated activation on both the dominant (p=0.013) and non-dominant sides (p=0.049), while non-tennis players presented the highest overall values for the non-dominant side (p<0.001).

At 45°, non-tennis players showed significantly greater activation of the middle trapezius on the dominant side (p=0.001), whereas tennis players presented higher activation on the non-dominant side (p=0.018). Regarding the lower trapezius, tennis players significantly higher activation on the dominant side (p=0.007), while non-tennis players again exhibited greater activity on the non-dominant side (p<0.001); see

Table 4.

For the right side plank (RSP), significant significant differences in muscle activation were observed in the lower trapezius (LT). Tennis players exhibited greater activation than non-tennis players on the non-dominant side at 90° of shoulder abduction (

p = 0.033), as well as on both the dominant (

p = 0.043) and non-dominant sides (

p = 0.039) at 45°; see

Table 5.

A significant main effect of angle was observed (F(1,36)= 6.67, p=0.014), with higher activation values recorded at 90° compared to 45°. A significant interaction between plank type and side was also found (F(1,36)=19.52, p<0.001).

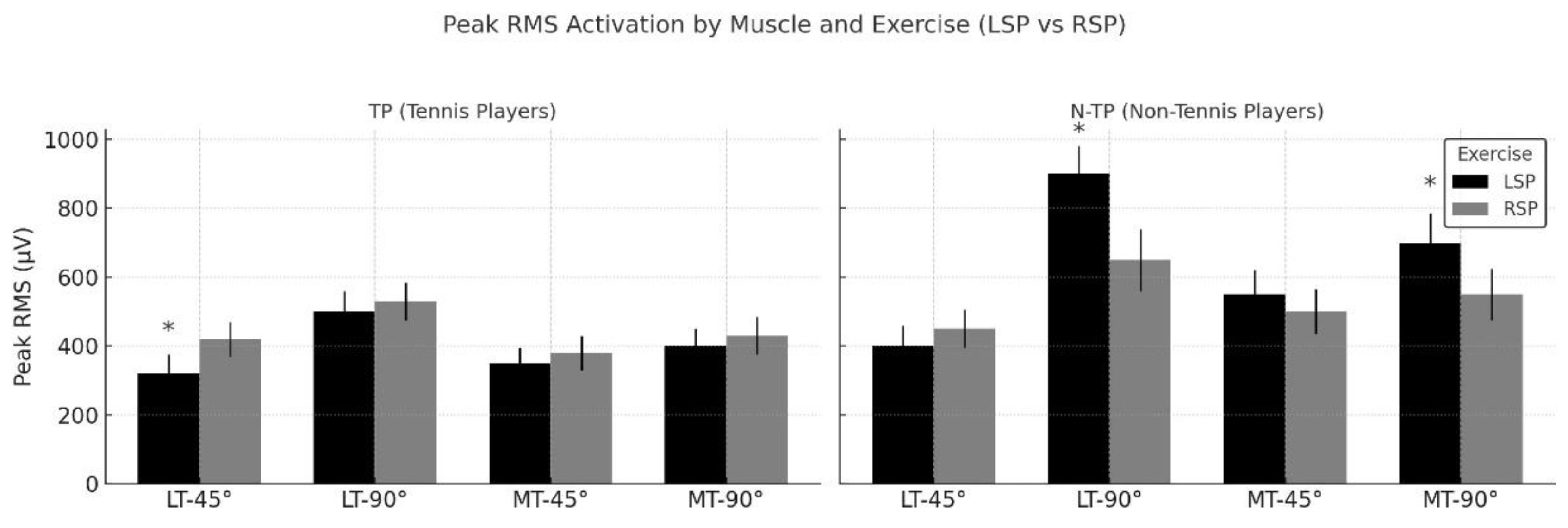

In addtion, a significant three-way interaction involving plank type, muscle, and side was detected (F(1,36)=9.94, p=0.003), as well as a significant three-way interaction between plank type, side, and shoulder abduction angle (F(1,36)= 6.72, p=0.014). Comparision within groups revealed significant differences between the LSP and RSP in TPs for MT at 90 ° and 45 ° (p<0.05).

Finally, a significant four-way interaction was found between plank type, side, angle, and player type (F(1,36)= 5.67, p=0.023). No other main effects or interactions reached statistical significance (p>0.05); see

Figure 2

Figure 2.

Comparision of mean RMS muscle activation (µV) during Left (LSP) and Right (RSP) Side Plank with resistance band in tennis players (TPs) and non-tennis players (N-TPs). Each bar represents the average activation of the middle trapezius (MT) and lower trapezius (LT) muscles at 45◦ and 90◦ of glenohumeral abduction, with error bars indicating ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM). Asterisks (*) denote statistically significant differences between Left Side Pland and Right Side Plank within group (p < 0.05, paired-sample ANOVA).

Figure 2.

Comparision of mean RMS muscle activation (µV) during Left (LSP) and Right (RSP) Side Plank with resistance band in tennis players (TPs) and non-tennis players (N-TPs). Each bar represents the average activation of the middle trapezius (MT) and lower trapezius (LT) muscles at 45◦ and 90◦ of glenohumeral abduction, with error bars indicating ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM). Asterisks (*) denote statistically significant differences between Left Side Pland and Right Side Plank within group (p < 0.05, paired-sample ANOVA).

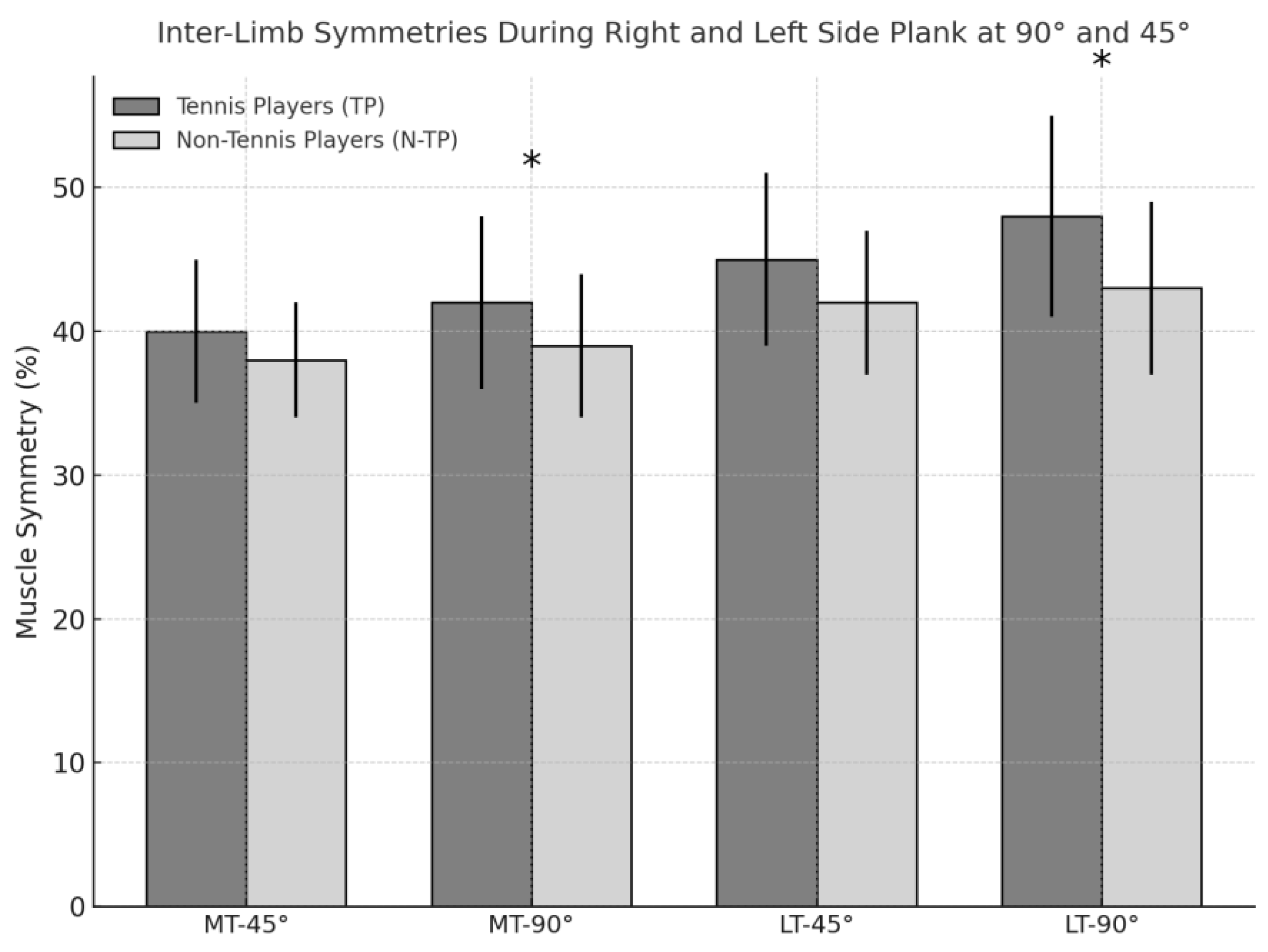

3.2. Inter-Limb Symmetries During Right and Left Side Plank at 90° and 45°

A significant difference between groups was observed for the Left Side Plank of the Middle Trapezius at 45°, where non-tennis players exhbited higher mean RMS values compared to tennis players (p=0.010). All other comparisions did not reach statistical significance (p>0.05) (

Table 6)

A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of muscle (F(1,36)=10.47),

p=0.003), indicating differences in mean RMS activation between the middle and lower trapezius. A significant interaction between exercise type and msucle was also oberseved (F(1,36)=4.37,

p=0.044), suggesting that changes in exercise side (LSP vs RSP) affected the two muscles differently (

Figure 3)

3.3. Peak Muscle Activation During Right and Left Side Plank at 90° and 45°

For the LSP, the activation of the MT at 90° was significantly higher in tennis players (p=0-008), as well as the LT at 90° (p=0.002). Additionally, the LT in the non-dominant arm at 90° showed a significant differences between groups (p<0.001).

At 45°, the MT in the non-dominant side also presented a significant difference (p=0.025), and the LT in the dominant side at 45° was significantly different (p<0.001); see

Table 8.

For the RSP, significant differences in peak muscle activation were observed between groups in three conditions. Specificalley, tennis players showed higher activation of the middle trapezius in the non-dominant side at 90° (p=0.016), as well as greater activation of the LT in both the dominant side at 90° (p=0.039) and non-tennis players ton he dominant side at 45° (p=0.037) (

Table 9)

Significant differences in peak RMS activation were identified across conditions considering limb dominance, muscle type, angle of shoulder abduction, and player type (tennis players [TPs] vs. non-tennis players [N-TPs]).

For the dominance factor, RMS peak values were significantly higher in the dominant limb across participants (p = 0.001, η²ₚ = 0.262). Regarding angle, shoulder abduction at 90° elicited significantly greater activation compared to 45° (p = 0.001, η²ₚ = 0.261).

A significant interaction between muscle and limb side (p = 0.011, η²ₚ = 0.166) showed that activation patterns differ between MT and LT depending on the side of execution (left vs. right plank). The muscle × dominance interaction reached significance (p = 0.023, η²ₚ = 0.135). Similarly, the angle × dominance interaction (p = 0.023, η²ₚ = 0.135) (

Figure 4)

4. Discussion

This study analysed neuromuscular recruitment and interlimb asymmetry of the middle (MT) and lower trapezius (LT) in tennis players (TPs) and non-tennis players (N-TPs) during unilateral scapular stabilization exercises at 45° and 90° of glenohumeral abduction with elastic resistance. Elastic bands were highlighted as a practical tool for injury prevention. The hypothesis of reduced LT activation and increased asymmetry in TPs was only partially confirmed, but the results reinforce the role of elastic resistance exercises in selectively engaging scapular stabilizers and exposing functional imbalances.

Tennis players consistently showed greater ND activation, particularly at 90° of abduction, with moderate-to-large effect sizes (d = 0.66–0.94). This is likely due to the increased biomechanical demands at higher elevation angles, where a longer external moment arm and reduced passive support from capsuloligamentous structures amplify scapular stabilizer requirements [

7,

28,

29]. In contrast, N-TPs displayed more symmetrical recruitment, suggesting that the adaptations observed in TPs are sport-specific, reflecting unilateral loading demands of training and competition [

22,

30,

31,

32]. Repetitive exposure to tennis strokes (~1,000 unilateral actions per match [

35]) may increase contralateral postural control needs and ND scapular activation [

33,

34]. Moreover, as tennis strokes often occur near 45° abduction [

5], chronic practice at this angle may induce relative inefficiency or weakness in scapular stabilizers [

25,

32,

35].

Overactivation of the ND scapular musculature may represent a compensatory strategy to enhance trunk and scapular stability under asymmetrical loads [[

5,

36,

37]. This highlights the need to consider both abduction angle and loading side when prescribing preventive exercises, since small configuration changes substantially influence recruitment [

29,

33,

38]. LT activation was particularly evident during resisted side plank, possibly due to trunk orientation and load direction increasing stabilization demands [

32,

39,

40]. The static support role of the dominant limb may further enhance contralateral LT activity.

Peak RMS values were consistently higher at 90° and on the ND side in TPs, suggesting these measures may serve as sensitive indicators of neuromuscular imbalance [

21,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Including RMS peak values could enrich functional evaluation and monitoring in preventive and rehabilitation programs.

Overall, unilateral side plank with elastic resistance significantly activated scapular stabilizers in both groups, particularly the LT. Its unilateral, laterally loaded design combines isometric stabilization with elastic tension, closely replicating sport-specific demands. Yet TPs exhibited more pronounced asymmetries than N-TPs, supporting the notion that chronic unilateral loading shapes scapular neuromechanics [

45,

46,

47,

48]. These adaptations may involve reorganization of motor strategies, with compensatory ND activation helping maintain thoracohumeral stability [

30,

32,

34,

36,

49]. Such findings underline the importance of tailoring preventive training to dominance profile and sport-specific context.

Targeted trapezius activation may help reduce risk for scapular dyskinesis and glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) [

3,

22,

41,

42,

50,

51,

52,

53]. Elastic resistance exercises appear valuable for correcting functional imbalances and mitigating chronic sport-induced asymmetries [

49,

54,

55]. Their simplicity, low joint stress, and specificity make them suitable for early rehabilitation and long-term maintenance, provided angle and loading side are individualized.

Limitations include the modest sample size of specialized athletes, restriction of EMG to MT and LT, lack of kinematic variables, and inherent variability in elastic band loading. Future studies should broaden populations, include other asymmetric sports, and adopt longitudinal designs to test whether elastic band training reduces asymmetry. Complementary assessments (strength, motor control, fatigue) could further clarify adaptations and compensatory strategies.

Practical Implications

Elastic resistance exercises at 90° abduction elicit higher trapezius activation and should be prioritised in preventive and rehabilitative protocols for tennis players.

Interlimb asymmetry assessment is essential in athletes from unilateral sports, as neuromuscular imbalances may increase injury risk if not addressed.

Exercise configuration matters: small variations in shoulder abduction angle or side of loading can substantially influence recruitment and should be tailored to athlete profile and dominance.

Unilateral resisted side plank provides a functional, low-stress exercise option that closely replicates sport-specific stabilization demands and can be integrated into both early-stage rehabilitation and ongoing maintenance programs.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that unilateral shoulder prevention exercises with elastic resistance effectively activate the middle and lower trapezius in both tennis and non-tennis athletes, with higher recruitment at 90° of abduction. Tennis players exhibited greater interlimb asymmetries, particularly with increased activation on the non-dominant side, reflecting sport-specific adaptations to repetitive unilateral loading. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating elastic resistance exercises at varied shoulder angles to selectively target scapular stabilizers, address neuromuscular imbalances, and reduce the risk of shoulder dysfunction in tennis players. Coaches and clinicians should tailor exercise selection to the athlete’s dominance profile and sport-specific demands to optimize preventive and rehabilitative strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S–T. and M.T.; methodology, M.S–T.; software, M.T.; validation, M.S–T.; formal analysis, M.T.; investigation, M.S–T. and M.T; resources, M.S–T. and M.T; data curation, M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.; writing—review and editing M.S–T..; visualization, M.S–T.; supervision, M.S–T.; project administration, M.S–T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declarationof Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of University Ramon Llull (CER,FPCEE Blanquerna, 1819011D, 10 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions related to participant confidentiality and the terms of informed consent.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all participants for this study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TP |

Tennis Players |

| N–TP |

Non–Tennis Players |

| LSP |

Left Side Plank |

| RSP |

Right Side Plank |

| MT |

Middle Trapezius |

| LT |

Lower Trapezius |

| D |

Dominant (side) |

| ND |

Non-Dominant (side) |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| ES |

Effect Size (Cohen’s d) |

| p |

Significance Level (p-value) |

| RMS |

Root Mean Square |

| µV |

Microvolts |

| ICC |

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| sEMG / EMG |

Surface Electromyography / Electromyography |

| STROBE |

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| VAS |

Visual Analogue Scale |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| FPCEE Blanquerna |

Facultat de Psicologia, Ciències de l’Educació i de l’Esport Blanquerna |

| CER |

Comitè d’Ètica de Recerca (Ethics Committee) |

| TPs / N-TPs |

Plural forms: Tennis Players / Non-Tennis Players |

| η²ₚ |

Partial Eta Squared (effect size in ANOVA) |

| SEM |

Standard Error of the Mean |

References

- Ramos-Álvarez, J.J.; Del Castillo-Campos, M.J.; Polo-Portés, C.E.; Lara-Hernández, M.T.; Jiménez-Herranz, E.; Naranjo-Ortiz, C. Estudio Comparativo Entre Deportes Simétricos y Asimétricos Mediante Análisis Estructural Estático En Deportistas Adolescentes. Archivos de Medicina del Deporte 2016, 33, 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Colomar, J.; Peña, J.; Vicens-Bordas, J.; Baiget, E. Range of Motion and Muscle Stiffness Differences in Junior Tennis Players with and without a History of Shoulder Pain. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2025, 20, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, V.Z.; Motta, C.; Vancini, R.L.; De Lira, C.A.B.; Andrade, M.S. Shoulder Isokinetic Strength Balance Ratio in Overhead Athletes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2021, 16, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, E.; Programme, D.; Physiotherapy, I.N. Shoulder Injury Prevention in Overhead Sports : Independent Learning Material for Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy Studies. 2020.

- Terré, M.; Solana-Tramunt, M. Muscle Recruitment and Asymmetry in Bilateral Shoulder Injury Prevention Exercises: A Cross-Sectional Comparison Between Tennis Players and Non-Tennis Players. Healthcare (Switzerland) 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, A.S.C.; Moreira, J.S.; Afreixo, V.; Moreira-Gonçalves, D.; Donato, H.; Cruz, E.B.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Sousa, A.S.P. Effectiveness of Specific Scapular Therapeutic Exercises in Patients with Shoulder Pain: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. JSES Reviews, Reports, and Techniques 2024, 4, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mey, K.; Danneels, L.; Cagnie, B.; Cools, A.M. Scapular Muscle Rehabilitation Exercises in Overhead Athletes with Impingement Symptoms: Effect of a 6-Week Training Program on Muscle Recruitment and Functional Outcome. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2012, 40, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, A.M.; Johansson, F.R.; Borms, D.; Maenhout, A. Prevention of Shoulder Injuries in Overhead Athletes: A Science-Based Approach. Braz J Phys Ther 2015, 19, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, P.R.; Neumann, D.A. Kinesiologic Considerations for Targeting Activation of Scapulothoracic Muscles – Part 2: Trapezius. Braz J Phys Ther 2019, 23, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berckmans, K.R.; Castelein, B.; Borms, D.; Parlevliet, T.; Cools, A. Rehabilitation Exercises for Dysfunction of the Scapula: Exploration of Muscle Activity Using Fine-Wire EMG. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2021, 49, 2729–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Yu, I.Y.; Oh, J.S.; Kang, M.H. Effects of Intended Scapular Posterior Tilt Motion on Trapezius Muscle Electromyography Activity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, J.B.; Jobe, F.W.; Pink, M.; Perry, J.; Tibone, J. EMG Analysis of the Scapular Muscles during a Shoulder Rehabilitation Program. American Journal of Sports Medicine 1992, 20, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstrom, R.A.; Donatelli, R.A.; Soderberg, G.L. Surface Electromyographic Analysis of Exercises for the Trapezius and Serratus Anterior Muscles. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 2003, 33, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlotta, M.; LoVasco, G.; McLean, L. Selective Recruitment of the Lower Fibers of the Trapezius Muscle. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2011, 21, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Tommasina, I.; Trinidad-Morales, A.; Martínez-Lozano, P.; González-de-la-Flor, Á.; Del-Blanco-Muñiz, J.Á. Effects of a Dry-Land Strengthening Exercise Program with Elastic Bands Following the Kabat D2 Diagonal Flexion Pattern for the Prevention of Shoulder Injuries in Swimmers. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Schwiertz, G.; Muehlbauer, T. Effects of an Elastic Resistance Band Intervention in Adolescent Handball Players. Sports Med Int Open 2021, 5, E65–E72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarin, N.C.; De Lira, C.A.B.; Vancini, R.L.; Pochini, A. de C.; da Silva, A.C.; Andrade, M. dos S. Strength Training Using Elastic Bands: Improvement of Muscle Power and Throwing Performance in Young Female Handball Players. J Sport Rehabil 2017, 26, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguszewski, D.; Dobrowolska, J. The Effects of Exercises with Elastic Bands on Selected Elements of Physical Fitness in Middle-Aged Amateur Tennis Players. Polish Journal of Sport and Tourism 2024, 31, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Fernandez, J.; Ellenbecker, T.; Sanz-Rivas, D.; Ulbricht, A.; Ferrauti, A. Effects of a 6-Week Junior Tennis Conditioning Program on Service Velocity. J Sports Sci Med 2013, 12, 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Kalo, K.; Vogt, L.; Sieland, J.; Banzer, W.; Niederer, D. Injury and Training History Are Associated with Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit in Youth Tennis Athletes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2020, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, P.; Balthillaya, G.; Bagrecha, S. Prevalence of Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit and Its Association with Scapular Dyskinesia and Rotator Cuff Strength Ratio in Collegiate Athletes Playing Overhead Sports. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2018, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terré, M.; Tlaiye, J.; Solana-Tramunt, M. Assessing Active and Passive Glenohumeral Rotational Deficits in Professional Tennis Players: Use of Normative Values at 90° and 45° of Abduction to Make Decisions in Injury-Prevention Programs. Sports 2025, 13, 0–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epidemiologico, C. del conocimiento STROBE Statement—Checklist of Items That Should Be Included in Reports Of. Universidad de los Andes 2020, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Holstila, E.; Vallittu, A.; Ranto, S.; Lahti, T.; Manninen, A. WorldMedical Association Declaration OfHelsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Cities as Engines of Sustainable Competitiveness: European Urban Policy in Practice, 2016; 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, G.; D’Emanuele, S.; Brustio, P.R.; Beratto, L.; Tarperi, C.; Casale, R.; Sciarra, T.; Rainoldi, A. Strength Asymmetries Are Muscle-Specific and Metric-Dependent. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Molina, A.; Ruiz-Malagón, E.J.; Carrillo-Pérez, F.; Roche-Seruendo, L.E.; Damas, M.; Banos, O.; García-Pinillos, F. Validation of MDurance, A Wearable Surface Electromyography System for Muscle Activity Assessment. Front Physiol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Merletti, R.; Stegeman, D.; Blok, J.; Rau, G.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Hägg, G. European Recommendations for Surface ElectroMyoGraphy. Roessingh Research and Development 1999, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Spanhove, V.; Van Daele, M.; Van den Abeele, A.; Rombaut, L.; Castelein, B.; Calders, P.; Malfait, F.; Cools, A.; De Wandele, I. Muscle Activity and Scapular Kinematics in Individuals with Multidirectional Shoulder Instability: A Systematic Review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2021, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cools, A.M.; Witvrouw, E.E.; De Clercq, G.A.; Danneels, L.A.; Willems, T.M.; Cambier, D.C. Scapular Muscle Recruitment Pattern: Electromyographic Response of the Trapezius Muscle to Sudden Shoulder Movement Before and After a Fatiguing Exercise; 2002.

- Colomar, J.; Corbi, F.; Baiget, E. Inter-Limb Muscle Property Differences in Junior Tennis Players. J Hum Kinet 2022, 82, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-de-Celis, C.; Labata-Lezaun, N.; Romaní-Sánchez, S.; Gassó-Villarejo, S.; Garcia-Ribell, E.; Rodríguez-Sanz, J.; Pérez-Bellmunt, A. Effect of Load Distribution on Trunk Muscle Activity with Lunge Exercises in Amateur Athletes: Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare (Switzerland) 2023, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madruga-Parera, M.; Bishop, C.; Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe, A.; Beltran-Valls, M.R.; Skok, O.G.; Romero-Rodríguez, D. Interlimb Asymmetries in Youth Tennis Players: Relationships with Performance. J Strength Cond Res 2020, 34, 2815–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadke, V.; Camargo, P.R.; Ludewig, P.M. Scapular and Rotator Cuff Muscle Activity during Arm Elevation: A Review of Normal Function and Alterations with Shoulder Impingement. Revista Brasileira de Fisioterapia 2009, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel Torres, R.; Ellera Gomes, J.L. Measurement of Glenohumeral Internal Rotation in Asymptomatic Tennis Players and Swimmers. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2009, 37, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonavolontà, V.; Gallotta, M.C.; Zimatore, G.; Curzi, D.; Ferrari, D.; Vinciguerra, M.G.; Guidetti, L.; Baldari, C. Chronic Effects of Asymmetric and Symmetric Sport Load in Varsity Athletes across a Six Month Sport Season. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Guerrero, O.; Gadea-Uribarri, H.; Villavicencio Álvarez, V.E.; Calero-Morales, S.; Mainer-Pardos, E. Relationship between Interlimb Asymmetries and Performance Variables in Adolescent Tennis Players. Life 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, I.; Ducher, G.; Brosseau, O.; Hautier, C. Asymmetry in Volume between Dominant and Nondominant Upper Limbs in Young Tennis Players. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2008, 20, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarsen, B.; Bahr, R.; Andersson, S.H.; Munk, R.; Myklebust, G. Reduced Glenohumeral Rotation, External Rotation Weakness and Scapular Dyskinesis Are Risk Factors for Shoulder Injuries among Elite Male Handball Players: A Prospective Cohort Study. Br J Sports Med 2014, 48, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellenbecker, T.S.; Pluim, B.; Vivier, S.; Sniteman, C. Common Injuries in Tennis Players : Exercises to Address Muscular Imbalances and Reduce Injury Risk CAN PLAY A KEY ROLE IN PRE- TION PROVIDED IN THIS ARTICLE LAR IMBALANCES THAT HAVE A. 2009, 31, 50–58.

- Chorley, J.; Eccles, R.E.; Scurfield, A. Care of Shoulder Pain in the Overhead Athlete. Pediatr Ann 2017, 46, e112–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cools, A.M.; Palmans, T.; Johansson, F.R. Age-Related, Sport-Specific Adaptions of the Shoulder Girdle in Elite Adolescent Tennis Players. J Athl Train 2014, 49, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.A.; De Giacomo, A.F.; Neumann, J.A.; Limpisvasti, O.; Tibone, J.E. Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit and Risk of Upper Extremity Injury in Overhead Athletes: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Sports Health 2018, 10, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohuchi, K.; Kijima, H.; Saito, H.; Sugimura, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Miyakoshi, N. Risk Factors for Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit in Adolescent Athletes: A Comparison of Overhead Sports and Non-Overhead Sports. Cureus 2023, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jácome-López, R.; Tejada-Gallego, J.; Silberberg, J.M.; Garcia-Sanz, F.; Garcia-Muro-San Jose, F. Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit in General Population with Shoulder Pain: A Descriptive Observational Study. Medicine (United States) 2023, 102, E36551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Ni, G.; Muh, S.; Lemos, S. Shoulder Muscle Activation Pattern Recognition Based on SEMG and Machine Learning Algorithms. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2020, 197, 105721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, D.H.; Alizadehkhaiyat, O.; Kemp, G.J.; Fisher, A.C.; Roebuck, M.M.; Frostick, S.P. Shoulder Muscle Activation and Coordination in Patients with a Massive Rotator Cuff Tear: An Electromyographic Study. J Orthop Res 2012, 30, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A, E.K.; A, J.W.; A, A.Z.; C, B.H.; A, D.V.; B, T.S.; Glass, S. Activation of the Trapezius Muscle during Varied Forms of Kendall Exercises. Physical Therapy in Sport 2008, 9, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barden, J.M.; Balyk, R.; Raso, V.J.; Moreau, M.; Bagnall, K. Atypical Shoulder Muscle Activation in Multidirectional Instability. Clinical Neurophysiology 2005, 116, 1846–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, A.M.; Declercq, G.; Cagnie, B.; Cambier, D.; Witvrouw, E. Internal Impingement in the Tennis Player: Rehabilitation Guidelines. Br J Sports Med 2008, 42, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, R.; Oceguera, M. GIRD, TRROM, and Humeral Torsion-Based Classification of Shoulder Risk in Throwing Athletes Are Not in Agreement and Should Not Be Used Interchangeably. J Sci Med Sport 2016, 19, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakic, J.G.; Smith, B.; Gosling, C.M.; Perraton, L.G. Musculoskeletal Injury Profiles in Professional Women’s Tennis Association Players. Br J Sports Med 2018, 52, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekelekis, A.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Moore, I.S.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B. Risk Factors for Upper Limb Injury in Tennis Players: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjelm, N.; Werner, S.; Renstrom, P. Injury Risk Factors in Junior Tennis Players: A Prospective 2-Year Study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2012, 22, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas, M.J.M.S.J. Rehabilitation of Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. SportEX Medicine 2014, 15, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbecker, T.S.; Cools, A. Rehabilitation of Shoulder Impingement Syndrome and Rotator Cuff Injuries: An Evidence-Based Review. Br J Sports Med 2010, 44, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).