1. Introduction

This paper develops the concept of

hybrid intelligence as a relational infrastructure for co-design between humans and artificial intelligences (AI) in craft and design ecologies. Examples of such technologies include generative AI systems (e.g., large language models), computer vision algorithms, and optimization tools used in design and production workflows [

1]. Rather than framing AI as replacements for artisanal expertise or as purely instrumental tools, we argue that they can act as collaborators, aligning with Miller’s [

2] discussion of creativity in

The Artist in the Machine,—“mirror tools” that amplify and reflect human creativity without erasing its cultural and embodied foundations [

3]. This perspective extends more-than-human approaches to participatory design [

4], positioning AI not as an external agent but as part of a situated network of humans, materials, and computational technologies that together shape craft futures.

The urgency of this inquiry lies in the accelerating integration of AI across design and production domains. Industry often celebrates AI for optimization and scalability, while craft practices emphasize improvisation, tacit knowledge, and cultural heritage. This tension raises three questions: How might generative AI tools support artisanal processes without undermining their authenticity? What new forms of authorship and agency emerge when human and non-human intelligences collaborate? And how can participatory design mediate these encounters to foster inclusive and resilient futures?

Craft provides a fertile arena for exploring these questions. Rooted in embodied skill, material dialogue, and community traditions, artisanal practices stand as counterpoints to mass production and cultural homogenization. Revivals of craft in Italy and beyond—driven by localism, sustainability, and renewed appreciation of material culture—demonstrate both the fragility and vitality of these knowledge systems [

5,

6]. At the same time, artisans are increasingly experimenting with digital fabrication, parametric modeling, and AI-assisted generative design. These hybrid practices illustrate both opportunities for innovation and anxieties around authenticity, authorship, and craft identity. Against this backdrop, we situate generative AI not as a threat to craft survival but as a potential co-designer in its renewal. This approach responds to broader debates on human-centered and value-aligned AI [

7,

8]. Through a literature review and interviews with six Italian experts, we analyze how practitioners imagine AI in relation to cultural memory, creative experimentation, and artisanal knowledge. We also introduce speculative scenarios that extend these imaginaries into possible futures, surfacing ethical and political tensions around human–AI coexistence. This paper outlines three paths. First, it proposes hybrid intelligence as a framework for more-than-human participatory design. Second, it offers situated insights from Italian craft experts negotiating AI’s integration. Third, it indicates how to combine thematic analysis with speculative futuring can highlight responsible pathways for human-AI collaboration making.

2. Theoretical Framework

To situate the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in craftsmanship, this section draws on complementary perspectives from design theory, anthropology, and human–computer interaction (HCI). Together, these lenses illuminate how human skill, material agency, and machine intelligence can be understood in relational rather than oppositional terms. David Pye’s concept of the

workmanship of risk [

9] emphasizes the uncertainty and variability that define traditional craft. Each object emerges through situated judgment, improvisation, direct material sensations, and embodied skill. By contrast, AI systems often privilege precision, repeatability, and control. Juxtaposing these logics exposes the stakes of hybrid practice: how might AI sustain creative risk without erasing the unpredictability that gives craft its value?

Richard Sennett’s notion of the

mirror tool [

3] suggests a possible answer. Rather than substituting human labor, mirror tools extend and reflect human capacities. Applied to AI, this idea positions algorithms not as autonomous producers but as amplifiers of tacit knowledge – capable of handling repetition, suggesting alternatives or visualizing options while preserving the artisan’s interpretative agency.

Lucy Suchman’s work on

situated human–machine collaboration [

10] introduces a critical perspective, reminding us that technology is never neutral. The ways AI systems are designed, implemented, and contextualized shape the distribution of agency and power. In craft contexts, this means that AI integration must respect artisanal authorship and creativity, rather than homogenizing or displacing them.

Giaccardi and Redström’s [

4] notion of

more-than-human design reframes participation as an ongoing negotiation among human and non-human actors. Craft, with its sensitivity to material dialogue and ecological entanglement, offers a particularly fertile ground for this orientation. In parallel, recent scholarships on generative AI highlight the convergence of art and computation [

11], underscoring that algorithms act as cultural as well as technical agents. Situated within craft ecologies, AI emerges not just as a tool of production but as a participant in a relational network linking humans, materials, traditions, and computational systems.

Recent work in HCI and design research reinforces this perspective. Rosner [

12] demonstrates how digital fabrication reshapes authorship and repair, while Devendorf and Rosner [

13] explore how computational tools can foreground care and improvisation in making. Alongside these studies, Sreenivasan and Suresh [

14] review synergies between design thinking and AI, highlighting the methodological convergence that hybrid intelligence builds upon. Liu et al. [

15] propose

hybrid craft as a framework for revitalizing traditional practices through computational methods, revealing both opportunities for innovation and risks of erasure. These contributions position AI not in opposition to craft but as part of an evolving repertoire of tools and collaborators in material culture. Related perspectives deepen this discussion: Tironi and Hermansen [

16] foreground the speculative and political dimensions of design anthropology; Jönsson and Lenskjold [

17] experiment with participatory methods that include diverse agencies; and Seghal and Wilkie [

18] examine how design futures can address the ethical challenges of emerging technologies. Collectively, these works underline the importance of approaching AI in craft ecology not as a neutral tool but as an actor entangled in cultural, material, and political networks.

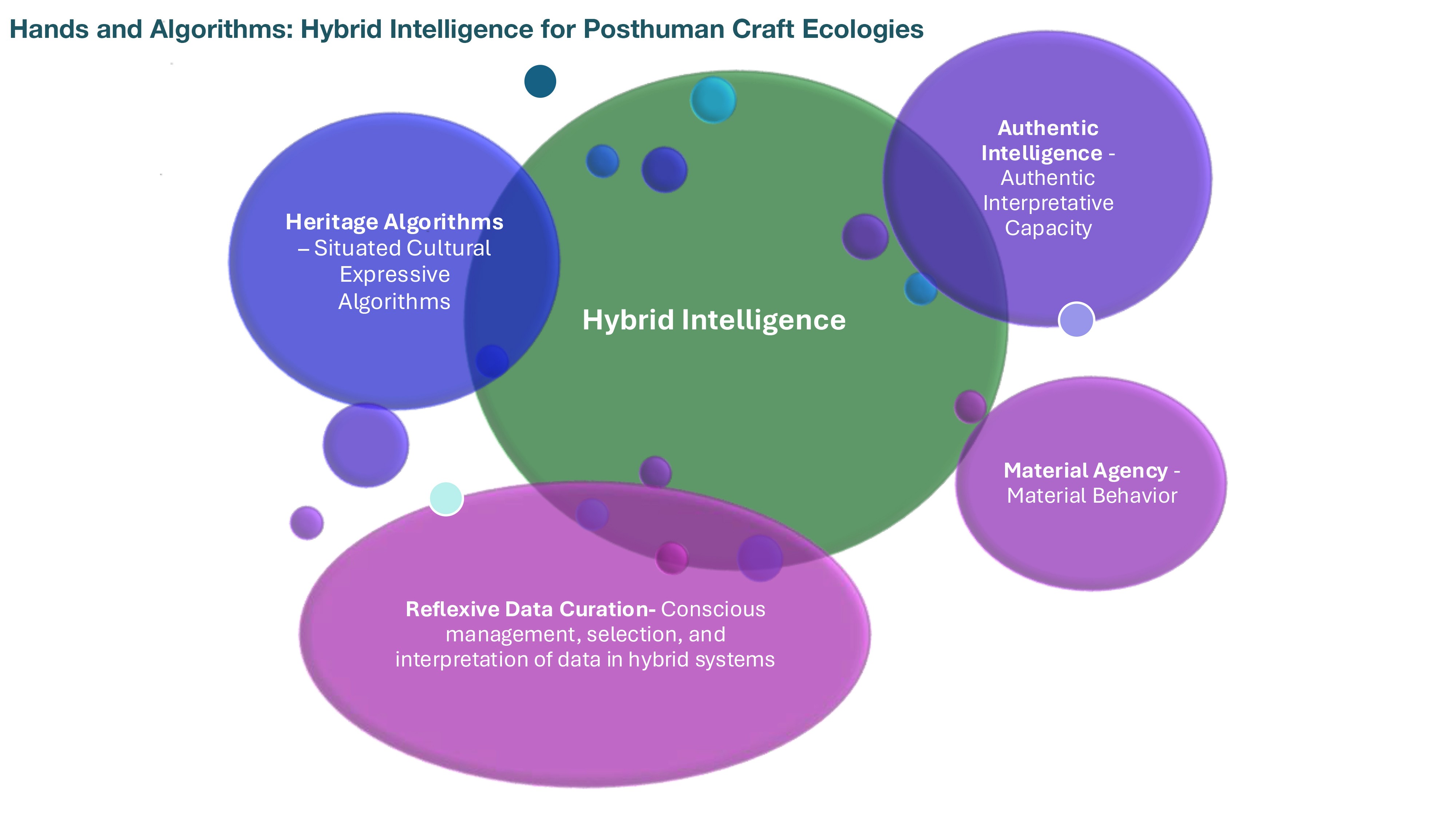

Figure 1.

Conceptual map of Hybrid Intelligence. Hybrid Intelligence—co-created between humans and algorithms in craft contexts—is supported by four pillars: Heritage Algorithms (cultural data practices), Authentic Intelligence (human judgment), Material Agency (active materials), and Reflexive Data Curation (critical data management). Arrows show their interdependence within this hybrid ecosystem.

Figure 1.

Conceptual map of Hybrid Intelligence. Hybrid Intelligence—co-created between humans and algorithms in craft contexts—is supported by four pillars: Heritage Algorithms (cultural data practices), Authentic Intelligence (human judgment), Material Agency (active materials), and Reflexive Data Curation (critical data management). Arrows show their interdependence within this hybrid ecosystem.

We define hybrid intelligence in craft as the relational interplay between human creativity, embodied skill, material agency, and machine computation. Four key concepts anchor this model:

the mirror tool (AI as an assistant that reflects and extends skill),

the workmanship of risk (variability and improvisation as values at stake),

heritage algorithms (data practices for preserving embodied knowledge in culturally situated ways), and

authentic intelligence (the interpretive, imaginative, and ethical capacities of humans that cannot be reduced to computation).

Within posthuman participatory design,

heritage algorithms reframe data as culturally curated rather than neutral [

19], inviting artisans to decide what is stored, shared, and transmitted.

Authentic intelligence emphasizes human judgment and ethical interpretation as central to participation, ensuring that design processes involve values beyond optimization. Together, these notions highlight hybrid intelligence as fragile and situated rather than seamless. While the term

heritage algorithms originates in Arzberger, Lupetti & Giaccardi [

19], here it is reinterpreted as a design research construct to frame culturally situated data practices within Italian craft contexts. Similarly, we extend the notion of authentic intelligence, originally discussed by De Cremer and Kasparov [

20], to emphasize the ethical and interpretative capacities of human creators in posthuman collaboration.

Building on Arzberger, Lupetti, and Giaccardi’s [

19] notion of

reflexive data curation, hybrid intelligence can be understood as a reflexive process through which human and machine co-learning unfolds. This framework embraces uncertainty, bias, and error not as failures to be corrected but as productive frictions that reveal tacit knowledge and cultural assumptions. Reflexivity, in this sense, is not only an individual cognitive stance but a material and relational practice that unfolds through encounters with algorithmic systems. This resonates with Giaccardi and Bendor’s [

21]

RETHINK DESIGN vocabulary, particularly the concepts of

Reflexive Data Practices and

Algorithmic Sites, which reposition AI collaboration as a situated process distributed across cultural, social, and technical networks. Within hybrid craft ecologies, workshops themselves become such algorithmic sites—spaces where artisans, materials, and AI systems negotiate meanings, biases, and creative directions in real time.

Hybrid intelligence describes not smooth collaboration, but a negotiated interplay: AI can extend practice, yet its integration risks standardization, disembodiment, and the erosion of agency. As Narayanan and Kapoor [

22] caution, uncritical enthusiasm for AI risks overstating its capabilities – what they call AI snake oil – underscoring the need for reflexive and context aware integration.

While existing research in digital fabrication, computational design, and repair studies has explored the tension between augmentation and replacement, our contribution lies in foregrounding cultural specificity. By grounding the concept of hybrid intelligence in Italian craft ecologies and their embedded traditions, we show how posthuman participatory design can be reframed through the dual lens of cultural heritage and more-than-human collaboration. This coupling distinguishes our approach, positioning hybrid intelligence not as a universal model but as a situated, culturally attuned framework for design research. Debates surrounding

augmentation versus replacement in computational design and digital fabrication provide an important backdrop for this discussion. Within HCI and critical making, scholars have examined how digital tools can both extend and constrain creative agency. Rosner [

12] and Devendorf and Rosner [

13] demonstrate that computational systems can reconfigure authorship and care in making—augmenting human skill while simultaneously reshaping the social relations of craft. Similarly, Bardzell and Bardzell [

23] and Löwgren [

24] argue that digital fabrication and design computation rarely substitute for human creativity but instead mediate interpretation, material sensitivity, and aesthetic judgment. Our study builds on these insights by examining how Italian artisans and designers negotiate similar tensions in the context of AI: the aspiration to enhance craftsmanship through algorithmic support coexists with a deep-seated fear of cultural homogenization and loss of embodied nuance. Hybrid intelligence reframes from augmentation not as seamless enhancement, but as a fragile negotiation between human intuition, material agency, and computational logic. While more-than-human design highlights the inclusion of non-human agents—materials, technologies, and environments—within design processes, posthumanism extends this stance by questioning the humanist assumptions that have long structured design inquiry. It shifts attention from recognizing multiple agencies to redistributing authorship, accountability, and decision-making across human and non-human participants [

25,

26,

27]. In this view, intelligence and creativity are not properties of individuals but emerge from intra-actions—relational entanglements through which meanings, materials, and agencies co-constitute one another [

27]. Therefore, adopting a posthuman lens reorients participatory design from managing tools or users toward co-decision and mutual becoming among heterogeneous actors—human, material, and computational [

28]. This stance foregrounds the ethical and political dimensions of hybrid craft ecologies, positioning AI not as an instrument but as a participant in distributed practices of care, negotiation and coexistence.

Within this framework, heritage algorithms are not just technical archives, but socio-cultural practices of data curation led by artisans to safeguard embodied knowledge. Authentic intelligence refers not simply to human rationality but to interpretive, imaginative, and ethical judgments that cannot be delegated to computational systems. Together, these concepts form a conceptual map of hybrid intelligence in craft—one that foregrounds its fragility, situatedness, and ethical complexity. Our perspective as design researchers is interpretative rather than neutral: we engage these imaginaries through a posthuman and participatory lens, acknowledging that our perspective is shaped as much by our disciplinary stance as by practitioner’s voices.

4. Results: Interpreting AI in Italian Craft Ecologies

The interviews reveal a complex and often ambivalent imaginary on AI in Italian craft. Rather than treating these responses descriptively, we analyze how each perspective aligns with, extends, or diverges from our theoretical framing of hybrid intelligence, mirror tools, workmanship of risk, and more-than-human design. We also discuss the practical feasibility of these imaginaries and synthetize imported concepts into a coherent framework.

The interviews reveal imaginaries that both align with and resist theoretical framings. Artisans and designers insist on authorship and authenticity, fearing homogenization. Engineers emphasize efficiency and innovation but underestimate cultural barriers. Scholars and curators see AI as a custodian of memory, which artisans question. These tensions—tradition vs. innovation; authorship vs. automation; preservation vs. standardization—are central findings. As a pilot, our contribution is not a resolution but surfacing these tensions for participatory design.

4.1. Authorship, Agency and Standardization

One artisan insists that “behind every project, there is a thought executed by skilled hands.” For them, AI risks mediocrity if it replaces artisanal judgment. This resonates with Suchman’s situated action [

10], where technology must remain contextual and subordinate to human agency. Yet it diverges from more-than-human design [

4], which positions AI as a co-actor [

2,

11]. The artisan’s scepticism defines a boundary condition for hybrid intelligence: AI may support but not co-create. In practical terms, this suggests that tools introduced in workshops must be clea

rly framed as assistive rather than directive in maintaining adoption.

A designer echoes this concern: “The machine must not dictate the design. I am still the maker.” This aligns with Sennett’s mirror tool [

3], where AI reflects without erasing authorship. Together, these voices emphasize the feasibility of hybrid intelligence only if systems are developed to preserve interpretive autonomy and embed transparency about authorship. Concerns about homogenization are widespread. One designer states: “I hope artificial intelligence in artisanal products plays no role at all,” highlighting fears that AI accelerates cultural flattening. An artisan reinforces this, describing authenticity as rooted in “thought by hand.” These imaginaries echo Pye’s workmanship of risk [

9], where variability and improvisation are valued. They diverge from optimistic framings of AI as a preservation tool, instead anticipating it as a driver of sameness. Practically, this signal that without mechanisms to localize data and reflect regional aesthetics, AI adoption risks rejection in traditional craft settings. Italian artisans resist AI as co-actor, suggesting that hybrid intelligence must be redefined as

bounded collaboration, not full co-design. For some artisans, the only viable path is rejection of AI in making. By contrast, an engineer counters: “Technology standardizes interfaces, not creativity.” This reflects De Cremer and Kasparov’s authentic intelligence [

20], emphasizing that humans can prevent homogenization. Yet feasibility here depends on resources: Craft SMEs often lack digital literacy and infrastructure to ensure creative autonomy. This reveals a tension in hybrid intelligence—artisans fear erasure, while engineers see creative potential—but without investment in training and accessible tools, the engineer’s optimism may remain aspirational. Notably, automation has already displaced heritage practices—for example, machine embroidery reducing demand for hand-stitching. These counterexamples highlight that hybrid intelligence trajectories may accelerate cultural loss if adoption is left uncritical.

4.2. AI as Assistant or Mirror

Several participants envision AI as supportive. One designer welcomes AI if it “helps me focus more on creation, not repetition.” This matches Sennett’s mirror tool, where AI removes repetitive labor and amplifies tacit skill. An engineer imagines AI as a “co-pilot” for project management, enhancing efficiency in Craft SMEs that often lack structured workflows. Another designer envisions intelligent kilns capable of “setting new parameters” and recognizing firing stages, enabling new interactions between material and maker. These examples extend Pye’s workmanship of risk, suggesting AI can create new spaces for experimentation. Yet feasibility depends on cost and accessibility. Intelligent kilns or AI-driven project management platforms are currently beyond the financial reach of many artisans. For hybrid intelligence to succeed, incremental and affordable interventions—such as open-source software or shared infrastructure in craft cooperatives—are necessary.

4.3. Ethical Design and Cultural Memory

One curator framed ethics as a human responsibility: “AI reflects us—it’s our mirror, and it’s up to us to decide what we see in it.” This view aligns partially with Sennett’s mirror tool [

3] but diverges from more-than-human ethics, which distribute agency among humans, technologies, and materials. Another curator emphasized, “It’s not about the tool—it’s about who controls the context,” echoing Suchman’s

situated design [

10] and underscoring that control structures fundamentally shape ethical outcomes. In practice, these insights point to the need for community-led governance of AI in craft. Questions of data ownership, authorship, and transparency cannot be left to technology providers alone. Without such mechanisms, ethical imaginaries risk collapsing into anxiety or resistance.

A scholar highlighted the “curation of data that reflects the laboratory practice of craftsmanship,” aligning with more-than-human design, where programming and improvisation coexist. Another academic added, “It could store gestures we’re losing; that’s valuable.” Building on Bennett’s [

30] notion of vibrant materiality, we extend her ideas to theorize what we term “heritage algorithms” as a design research construct. Although Bennett does not use this term herself, her argument that non-human entities—objects, materials, infrastructures—possess agentic capacities provides a conceptual foundation for rethinking data and computation as active participants in cultural life. Within design and craft studies, Bennett’s material vitalism has been mobilized to show that heritage and memory are not static archives but living, evolving systems. In this spirit, heritage algorithms describe socio-technical processes that encode, transmit, and transform cultural and craft knowledge, blending human memory, material practice, and computational mediation. They reimagine data curation, archiving, and machine learning as participatory cultural practices rather than neutral technical operations. This perspective foregrounds artisans’ agency in deciding what knowledge is digitized, how it is represented, and how computational systems might preserve or reinterpret cultural memory without erasing its embodied and local dimensions.

Yet artisans express skepticism, prioritizing embodied skills over digital archives. This divergence reveals a generational and epistemic gap: while academics and curators envision AI as a cultural repository, artisans fear the loss of embodied nuance. Practically, the feasibility of heritage algorithms depends on co-designing archival tools with craft communities to ensure cultural continuity without disembodiment.

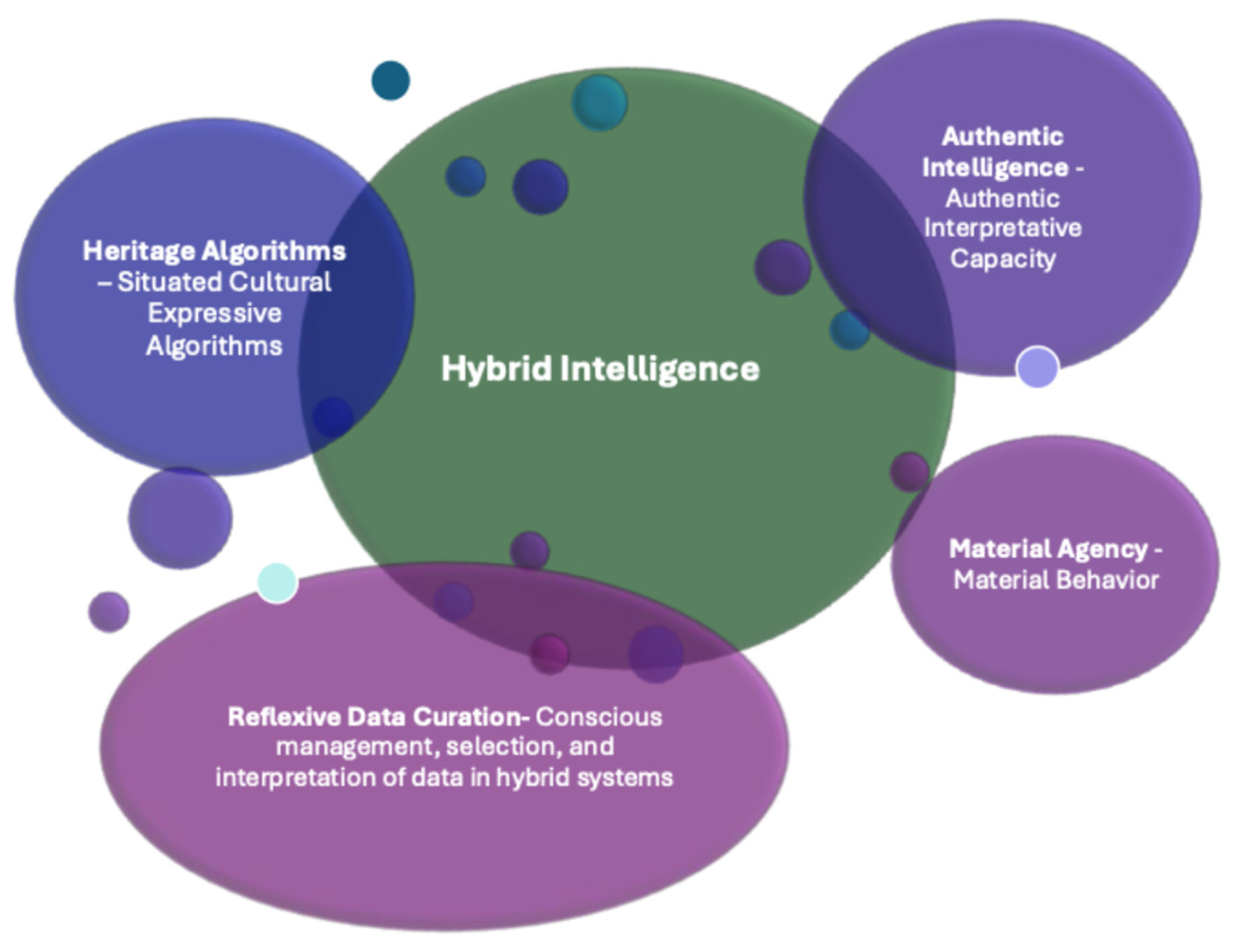

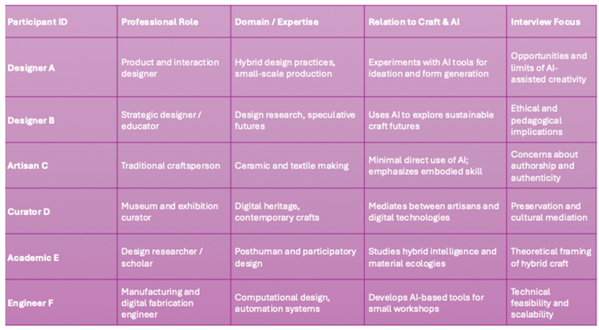

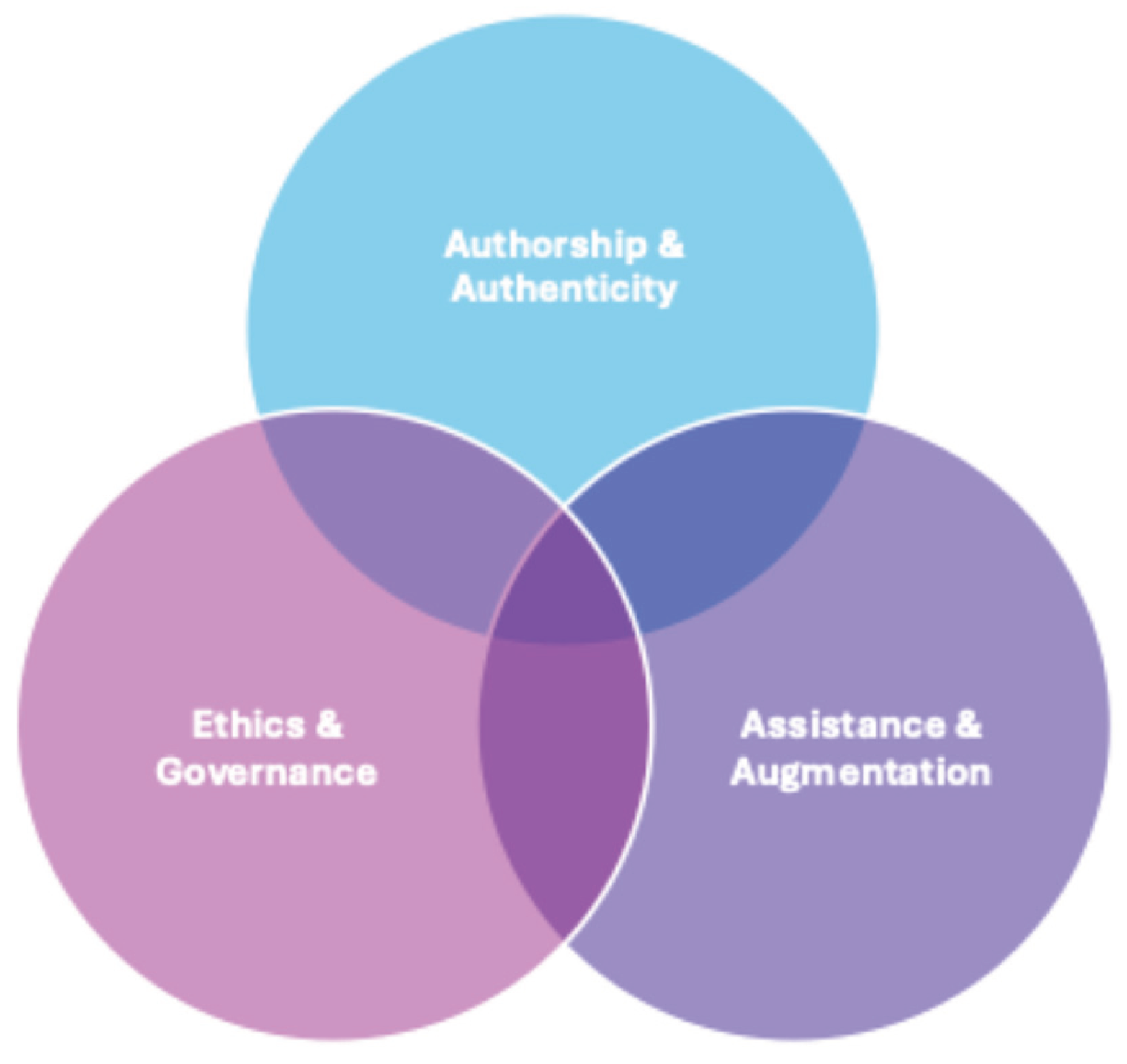

Figure 2.

Thematic clusters from interviews. This figure visualizes the three main themes emerging from the interviews—Authorship & Authenticity, Assistance & Augmentation, and Ethics & Governance—and their intersections, illustrating how participants’ perspectives overlap across creative, technical, and ethical dimensions of AI in craft.

Figure 2.

Thematic clusters from interviews. This figure visualizes the three main themes emerging from the interviews—Authorship & Authenticity, Assistance & Augmentation, and Ethics & Governance—and their intersections, illustrating how participants’ perspectives overlap across creative, technical, and ethical dimensions of AI in craft.

The ambivalence expressed by artisans and designers—oscillating between fascination and resistance—echoes the tactics of reflexive data curation identified by Arzberger et al. [

19]:

auto-confrontation,

change of perspective, and

clash of expectations. Artisans’ discomfort with automation, or their insistence on manual authorship, can be read as moments of auto-confrontation—critical junctures where traditional knowledge meets algorithmic mediation. Similarly, curators’ and scholars’ speculative optimism enacts a change of perspective that reimagines AI as a cultural participant. In this sense, the tensions observed are not contradictions to be resolved but reflections of a reflexive human-AI practice already underway.

4.4. Conclusion of Findings

The interviews reveal imaginaries that both align with and resist theoretical framings:

Alignment: Mirror tool (designer, curator), workmanship of risk extended by AI (designer), heritage algorithms as cultural memory (scholar).

Divergence: Rejection of AI as co-actor (artisan, designer), authenticity fears (artisan, designer) versus optimism about creativity (engineer).

Feasibility requires addressing infrastructural and cultural barriers: Craft SMEs need affordable tools and digital literacy; artisans require assurances of authorship and authenticity; and communities must retain control over data. Imported concepts such as the mirror tool, workmanship of risk, and heritage algorithms converge in a sharper synthesis here: hybrid intelligence in Italian craft is not a seamless collaboration, but a situated negotiation where feasibility depends on respecting artisanal boundaries, enabling accessibility, and embedding ethical governance.

Hybrid intelligence in Italian craft ecologies emerges as both promising and precarious. It aligns with theoretical notions of reflective partnership and cultural preservation but diverges when fears of homogenization and loss of authorship dominate. Feasibility depends on incremental, affordable, and community-controlled adoption strategies. Far from universal, hybrid intelligence is always situated, partial, and contested—a condition that design research must embrace rather than resolve.

Taken together, these findings recalibrate the theoretical model of hybrid intelligence by emphasizing its negotiated and contingent character within participatory design. While our framework initially conceived AI as a co-designer within more-than-human assemblages, the Italian case underscores the need to temper this view with a stronger attention to asymmetries of agency, access, and authorship. Artisans’ skepticism toward AI as a creative collaborator reveals that participation in hybrid systems is not merely a matter of inclusion but of boundary work—where practitioners continuously define what should remain human, embodied, and situated. For participatory design, this implies a methodological shift from designing with AI toward designing the conditions of coexistence—that is, facilitating dialogue, governance, and critical reflection across human and computational actors. In this sense, the empirical evidence transforms hybrid intelligence from an aspirational framework of seamless collaboration into a reflexive practice of negotiation, care, and partial alignment among heterogeneous intelligences.

5. Speculative Future of Hybrid Craftsmanship

Our approach to speculative scenarios is inspired by critical design [

31], reflective design [

32], and anticipatory design practices [

33,

34], using speculation as a means of inquiry rather than prediction. Building these findings, we extend the analysis into speculative design scenarios. Each scenario explicitly connects to participant imaginaries, theoretical frameworks, and practical feasibility. Extending the

RETHINK DESIGN lexicon, these speculative futures can be read as experiments in

acts of interfacing [

15] and

prototeams [

35], where artisans, designers, and AI systems collaborate through iterative and provisional partnerships. Each scenario treats hybrid intelligence as a reflexive infrastructure that unfolds within specific algorithmic sites of making. Through such speculative prototyping, we explore how uncertainty, bias, and material negotiation might become productive forces in crafting responsible human-AI futures.

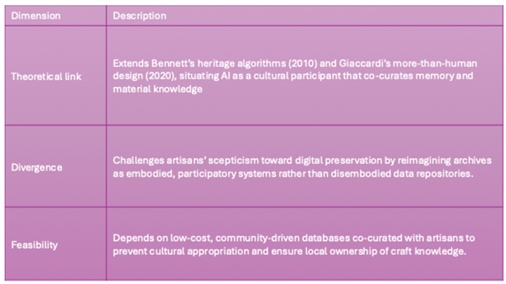

Scenario 1: The AI Apprentice with Memory

In a small workshop, an artisan collaborates with an AI trained on regional gestures. The AI suggests forgotten methods, acting as a co-learner rather than a dictator.

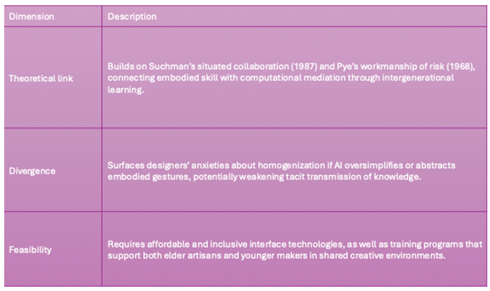

Scenario 2: Intergenerational Craft Interfaces

An augmented environment allows elder artisans and younger makers to co-design through tactile and digital means. Gestures are captured and visualized, blending oral tradition with computational mediation.

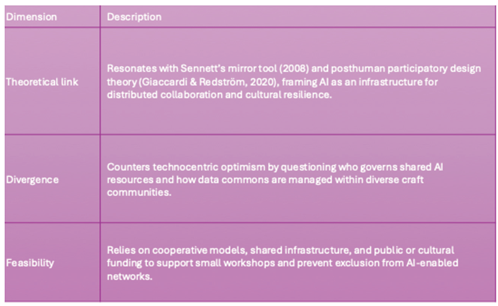

Scenario 3: Decentralized Design Sanctuaries

Networks of workshops adopt open-source AI systems to curate and remix local craft knowledge, balancing experimentation and sustainability.

Across these scenarios, hybrid intelligence emerges not as seamless innovation but as a contested and negotiated process. Each vignette extends a specific participant imaginary while highlighting practical conditions for adoption. Together, they demonstrate that hybrid craftsmanship requires incremental, community-driven, and ethically governed approaches. Only then can hybrid intelligence balance tradition and innovation, efficiency and authenticity, and assistance and authorship in Italian craft ecologies.

Our scenarios highlight both potential and risk:

AI Apprentice with Memory: Extends heritage algorithms, but risks disembodied archives disconnected from practice.

Intergenerational Craft Interfaces: Promotes skill transfer, but risks oversimplification of embodied knowledge.

Decentralized Design Sanctuaries: Democratizes AI use, but risks exclusion without governance and infrastructure.

By framing AI as an Epimethean figure—a symbol of afterthought, delayed wisdom, and hesitant reflection rather than heroic foresight—we emphasize that it reflects risks as well as opportunities.

6. Conclusions

Hybrid intelligence in Italian craft ecologies emerges as promising but precarious. It aligns with theoretical models of reflective partnership and cultural preservation yet diverges when fears of homogenization and loss of authorship dominate. Feasibility depends on incremental, affordable, and community-controlled strategies. This study should be understood as exploratory: a pilot that surfaces tensions rather than resolves them. Its value lies in situating hybrid intelligence within Italian craft ecologies, offering a starting point for participatory design research that can develop more concrete, actionable models of responsible human–AI coexistence.

Participatory design must evolve explicitly including non-human collaborators such as AI systems and material ecologies. This requires methods that move beyond human-centered frameworks toward infrastructures of coexistence. Designers should cultivate practices that invite AI into co-creation as a reflective partner, while also attending to power, authorship, and ethical concerns. By treating AI as one actor among many in socio-technical networks, participatory design can better support inclusive and situated modes of making.

The integration of AI into craft highlights the need for hybrid apprenticeship models that combine traditional skill transmission with computational literacies. Rather than framing digital tools as displacing artisanal knowledge, education can position them as mediators of intergenerational exchange. For students, this means learning both tacit, material practices and algorithmic ways of working; for educators, it calls for pedagogies that embrace improvisation, reflection, and critical awareness of technology’s cultural impacts.

For craft communities, the challenge lies in developing strategies for ethical AI adoption that preserve cultural authenticity while enabling innovation. This includes creating accessible pathways to AI tools, ensuring community control over data and design processes, and resisting homogenization by embedding AI within local traditions and values. Approached critically, AI can assist artisans in documentation, sustainability, and experimentation—supporting resilience without eroding identity.

Hybrid intelligence in craft is inseparable from the reflexive capacities that designers and artisans cultivate through their engagement with AI. Following Arzberger, Lupetti, and Giaccardi [

19], reflexive data curation transforms data work into a meaningful practice of introspection, where encountering algorithmic uncertainty becomes an opportunity for ethical awareness and creative reinvention. As articulated by Giaccardi and Bendor [

21], such reflexive data practices are foundational to design with AI in ways that are situated, inclusive, and more-than-human. Hybrid intelligence could represent not only a technological configuration but also a pedagogical and ethical orientation—one that encourages designers to work with, rather than against, the frictions of computation.

In bringing together theory, empirical insights, and speculative futures, this paper argues for hybrid intelligence as a framework for responsible human–AI coexistence in craft. By reframing AI as a dialogic partner in design, we open pathways for participatory practices that take care of cultural heritage, sustain artisanal agencies, and imagine more inclusive and resilient futures for making. This study should therefore be read as an initial, situated exploration. Its small sample and speculative scenarios limit generalizability, but its value lies in making visible the contested imaginaries that shape hybrid intelligence in Italian craft. These insights outline directions for future research to develop more concrete and actionable models of responsible human–AI coexistence.