1. Introduction

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is an inherited motor neuron disorder (MND) characterized by progressive muscle atrophy caused by the loss of lower motor neurons (MNs) in the ventral horn of the spinal cord, resulting in weakness and wasting of proximal limb and respiratory muscles. The disease is triggered by homozygous loss-of-function variation in the

survival of motor neuron 1 (

SMN1) gene [

1,

2], which encodes the SMN protein, a key factor in post-transcriptional RNA processing, including mRNA splicing. Disease severity is strongly modified by the copy number of the paralogous

SMN2 gene. Patients with few

SMN2 copies typically develop severe, early-onset SMA within the first months of life, while higher copy numbers lead to milder forms with later onset of symptoms [

2,

3,

4,

5].

The identification of the genetic basis of SMA has led to the development of therapies that restore SMN expression, with nusinersen becoming the first approved treatment in 2016 [

6,

7]. While SMN-enhancing drugs have significantly improved survival and motor outcomes, their therapeutic effect is limited when treatment is initiated at advanced disease stages [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Persistent motor deficits and the high economic burden of treatment highlight the need for complementary, SMN-independent therapeutic strategies.

Astrocytes, the predominant glial cell type in the central nervous system, have emerged as significant contributors to the pathophysiology of MND, including Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and SMA. Several studies have shown astrocytic activation preceding MN degeneration [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. In late-onset SMA, astrocytic dysfunction has been implicated in MN death, with evidence pointing to dysregulated glutamate homeostasis as a key driver of neurotoxicity in both a late-onset SMA mouse model and patient-derived samples [

16].

Astrocytes communicate through gap junctions composed of connexons, each formed by six connexin proteins [

18,

19]. Connexin 43 (Cx43), encoded by

GJA1, is the predominant connexin expressed in astrocytes and plays a central role in intercellular coupling. Cx43 has been implicated in maintaining central nervous system homeostasis through multiple mechanisms, including buffering extracellular ions, synchronizing astrocytic networks, providing metabolic support to neurons, regulating the blood–brain barrier, and modulating synaptic plasticity [

20,

21,

22]. Importantly, Cx43 has been linked to the regulation of extracellular glutamate, suggesting that astrocytic gap junctions are involved in controlling excitatory neurotransmission [

23,

24]. Dysregulation of astrocytic Cx43 has been associated with neurodegeneration, and its contribution to MN pathology has already been established in ALS [

25].

Building on our recent findings that astrocytic activation and glutamate dysregulation drive MN death in late-onset SMA [

16,

17], Cx43 emerges as a promising candidate mechanism for contributing to astrocyte-mediated neurotoxicity. In the present study, we investigate the role of astrocytic gap junctions, with a focus on Cx43, in the context of late-onset SMA. To this end, we employ complementary in vitro and ex vivo approaches, including SMN-deficient human induced astrocytes, murine astrocyte cultures, spinal cord slice preparations, and the Taiwanese mild SMA mouse model, which recapitulates the late-onset phenotype [

26]. We hypothesize that astrocytic Cx43 contributes to MN degeneration in late-onset SMA and propose that targeting this protein may provide a potential SMN-independent therapeutic strategy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

The Taiwanese mild SMA mouse model reflecting late-onset SMA (FVB.Cg-Smn1<sup>tm1Hung</sup>Tg(SMN2)2Hung/J; Jackson Laboratory #005058) was obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and bred in the Animal Research Facility of the University Hospital Essen (North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany). These mice are double homozygotes carrying a knockout of murine

SMN1 together with four copies of the human

SMN2 gene. Compared with wild-type FVB/N mice, they are smaller in size and exhibit reduced body weight, decreased grip strength, and hindlimb weakness. In addition, ear and tail necrosis typically occur, resulting in shortened ears and thickened, shortened tails. Previous studies demonstrated MN loss in this model at approximately postnatal day (P) 35, defining this stage as a critical time point to investigate the role of Cx43 [

16,

17]. For temporal analysis, P20 was defined as the early stage, P35 as the onset of MN loss, and >P100 as the late stage of disease progression.

Wild-type (WT) FVB/N mice were used as controls and for culture experiments. For MN preparation, embryos were harvested at embryonic day (E) 14 from timed pregnant WT females. All animals were maintained under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional animal welfare guidelines of the University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany. The use of the late-onset SMA mouse model was approved by the State Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety (LAVE), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany (approval number 81–02.04–2020.A335).

2.2. Isolation of the Spinal Cord

To extract the spinal cord, WT mice were euthanized by decapitation, after deep anesthetization with isoflurane. The spine was then extracted, and the spinal cord was obtained by hydraulic extrusion. The meninges were removed, and the cord was ready for use.

2.3. Spinal Cord Slice Preparation

The lumbar part of the spinal cord was placed in embedding medium and snap frozen using liquid nitrogen. The tissue was then cut into 20 µm slices using a cryotome. Every fifth section of each spinal cord was mounted on an independent microscopy slide and stored at -20 °C.

2.4. Culture of Spinal Astrocytes from WT Mice

The spinal cord tissue was finely diced with a razor blade and placed in a 0.25% trypsin/EDTA solution (#25200056, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) for 30 min at 37 °C. Enzymatic digestion was halted by introducing DMEM/F12 (#210410202, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, #16140071, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) to the solution. A homogenized cell solution was then produced by mechanical titration with a pipette. The solution was centrifuged down at 500 G for 5 min. The supernatant was removed, 10 mL of our culture medium (a DMEM/F12 solution containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, #15140122, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany), was added and then transferred to a 75 cm2 cell culture flask (T75) and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The next day and for every 2 days after that, the medium was exchanged with fresh culture medium until a confluency of about 65% was reached at 10-14 days in vitro (DIV). The flask was then placed on an orbital shaker (250 rpm, 37 °C, 5% CO2) overnight for the microglia to detach. Subsequently, the culture medium was exchanged, and cells were detached from the cell culture flask, enumerated, and then seeded with 3500 cells per coverslip onto poly-d-lysine (PDL) (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany)-treated glass coverslips in a 24-well plate. The culture medium was again replaced in the same manner.

2.5. Human Tissue Samples

Human skin biopsy was performed by a physician. All participants provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Duisburg-Essen (approval number 19–9011-BO).

2.6. Generation of hiAstrocytes from Skin Fibroblasts

hiAstrocytes were generated from dermal fibroblasts of healthy donors as previously described [

27]. In brief, fibroblasts were directly reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), via retroviral transduction with

Oct4,

Sox2,

Klf4, and

c-Myc (#RF101, ALSTEM, USA) in the presence of a neural induction medium. Following transfection, cells were maintained in conversion medium. Conversion medium was a solution of DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1% GlutaMAX, 1% N-2 supplement, 1% B27 supplement, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 20 ng/mL human fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-basic (#100-18B, PreproTech, Germany), 20 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor (EGF) (#AF-100–15, PreproTech, Germany), and 5 μg/mL heparin). Cells were passaged at a 1:2 ratio after five days to allow further multiplication and then plated after an additional 2–3 days onto PDL-coated glass coverslips.

iPSCs were subsequently cultured in iPSC medium (DMEM/F12 with 1% GlutaMAX, 1% N-2 supplement, 1% B27 supplement, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 40 ng/mL human FGF-basic) until confluent. The cells were then enzymatically dissociated using Accutase and seeded into 24-well plates containing PDL-coated coverslips. Differentiation into hiAstrocytes was induced using an astrocyte conversion medium (DMEM high glucose supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.2% N-2 supplement) and maintained until approximately 80% confluency was achieved.

2.7. Induction of SMN Deficiency in Cultured Spinal Astrocytes

Following the replating process, small interfering (si)RNA experiments were commenced after 7 DIV. A genetic knockdown was achieved by transfecting WT murine astrocyte cultures with mouse-specific SMN1-siRNA (#SR408287, OriGene, USA) to induce SMN deficiency. For hiAstrocytes, human SMN1 (#SR304480 OriGene, USA) was used. Transfection with scrambled(scr)-siRNA-FITC (#sc-36869, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA) served as our control. For this purpose, 2 h before applying siRNA to the spinal astrocytes, the medium was replaced with FBS-free medium (only DMEM/F12 containing 1% P/S).

Subsequently, 10 nM of the

SMN1-siRNA was combined with 200 μM of SilenceMag (#SM11000, OZ Biosciences, Marseille, France) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature (RT). The solution was then added to the cells and incubated for 2 h on a magnetic plate at 37 °C and 5% CO

2. The magnetic plate was then removed, and the cells allowed to incubate until the next day, when the siRNA medium was exchanged with fresh medium (DMEM/F12, 10% FBS, 1% P/S) and in part with 200 μM Gap27 (#E0040, Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA), a Cx43 inhibitor. The cells were maintained in culture for three more days before being used in experiments. The efficiency of this transfection method has been previously evaluated by immunostaining for SMN-positive cells after transfection [

17].

2.8. Immunostaining

For immunostaining, cell cultures and tissue were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and permeabilized with 0.1 v/w Triton X-100 in PBS. The tissue was then blocked in a solution of 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, and the cells were treated with 1% BSA in PBS.

Primary antibodies against Cx43 (rabbit, 1:500, #SAB4501175 Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), βIII-tubulin (TUJ1) (mouse, 1:500, #8578 Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), non-phosphorylated neurofilament proteins (SMI-32, mouse, 1:500, #801701, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (mouse, 1:500, #63893, Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) were diluted in the appropriate blocking agent and incubated over night at 4 °C.

After washing, secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit, goat anti-mouse, 1:300, Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1:500, Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany), diluted in blocking solution, were administered to the tissue and cells, incubated for 1.5 h at RT, then washed, covered, dried overnight, and sealed.

Images were captured utilizing a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The Zeiss Zen software was employed to visualize the target proteins. To ensure consistency in the analyses, all microscope settings, including laser intensity, exposure time, and contrast, were maintained at identical parameters for each protein. With the use of the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), the immunoreactivity of the tagged protein in the spinal cord tissue slices was measured by marking the target area. The fluorescence intensity was then normalized against the background intensity of each area. ImageJ was used to determine the cell count of MNs, and the quantity of Cx43 particles in the astrocytes.

All analyses were conducted by setting the experiment into the perspective of an appropriate control. WT mice were used as a control for SMA mice. scr.-siRNA transfected astrocytes were used as controls for SMN-deficient astrocytes.

2.9. Western Blots

Western blot (WB) analysis was performed to confirm the protein levels assessed through immunostaining. To achieve this, spinal cord tissue from SMA and WT mice was homogenized using RIPA buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Germany). The protein content in these lysates was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (BCA).

A total of 10 µm of protein was applied to 4–15% TGX Stain-Free gels (Biorad, Germany); subsequent protein transfer to 0.2 µm nitrocellulose membranes was achieved through a semi-dry blotting technique. Membrane images were captured for comprehensive assessment of total protein. The membranes then underwent a 10-min incubation in fast-blocking solution (Biorad, Germany) with gentle agitation at RT. Following this, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies diluted 1:8000 in blocking solution, targeting Cx43, at 4 °C overnight.

The secondary anti-rabbit antibody diluted at 1:10000 in blocking solution and coupled to horseradish peroxidase was then introduced to the membranes after thorough washing and incubated for 90 min at RT. After another washout, an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate was added, and immunoreactivity was detected using a WB imaging system (BioRad, Germany). The WB signals were analyzed with Biorad imaging software. Initially, the signal intensity of Cx43 lanes were assessed. Subsequently, the protein signal of the lanes was adjusted relative to its total protein value. Lastly, the determined protein level in SMA mice was normalized against the value observed in age-matched controls. The blots and the total protein are shown in the Additional file.

2.10. Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reactions

The total RNA was isolated from spinal cord samples employing Qiazol (Qiagen #79306). One microgram of each RNA sample was used for first-strand complementary DNA synthesis in a 20-μL reaction using the high-capacity cDNA RT Kit (Applied Biosystems #4368814). Expression levels of the Cx43 gene GJA1 (forward primer: GGTGATGAACAGTCTGCCTTTCG, reverse primer: GTGAGCCAAGTACAGGAGTGTG; #MP205239, OriGene, United States) were quantified through real-time quantitative polymerase chain reactions (qPCR) analysis utilizing Power SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (#4,367,659, Applied Biosystems, United States). Data were normalized to a β-actin gene (forward primer: CATTGCTGACAGGATGCAGAAGG, reverse primer: TGCTGGAAGGTGGACAGTGAGG; #MP200232, OriGene, United States).

2.11. Isolation and Culture of Organotypic Spinal Cord Slice Cultures from WT and SMA-Mice

To achieve the best resemblance of SMA pathophysiology in the mouse spinal cord and the effect of pharmacology on this tissue with the lowest burden on the animal, slice culture experiments were established. After isolating the spinal cord of SMA mice at P25(±1), the lumbar section was extracted, placed on an appropriately cut agar plate, and introduced to a vibratome filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid, 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM glucose. 350 µm slices were prepared and put on inserts with a semi-permeable membrane into wells filled with a culture medium consisting of Neurobasal-A (#10888022, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) containing 1% P/S and 2% B-27 Plus Supplement (#17504044, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany). Age-matched control mice were utilized in a different experiment with the same protocol.

On 1 DIV, the culture media was replaced with fresh medium, and half of the samples were treated with Gap27. The supernatant (SN) was collected at 1, 7, and 14 DIV, snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C for experimentation purposes.

2.12. Isolation and Culture of Spinal Motor Neurons from Embryonic WT Mice

Embryos at E14 were harvested from the expecting mother, decapitated, fixed to a plate, and had their spinal cord removed under the microscope. The meninges were carefully removed, and the cord was kept in Neurobasal (#21103049, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) on ice. Next, the spinal cords were introduced to our 0.25% trypsin/EDTA solution and allowed to digest at 37 °C.

After enzymatic digestion and mechanical dissociation with a pipette, the tissue was centrifuged and added to a culture medium consisting of DMEM:F12 with 1% P/S, 10% FBS, and 1:800 GlutaMAX (#35050061, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Dreieich, Germany). The cell suspension was then added to a petri dish and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1h. The debris was gently washed off, and the adhering cells were scraped off, added to the culture medium, and plated on PDL-coated wells (5000 cells/well). After incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, the wells were flooded with culture medium to a total of 500 µl.

The next day, the medium was removed. A new medium was introduced, consisting of Neurobasal with 2% B-27, 1% P/S, 1:800 GlutaMAX, 1:400 ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF, #C-240, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), 1:100 glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF, #G-240, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), and 1 µl cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside (AraC, #C6645, Sigma Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). The medium was then changed at 8 DIV, and the culture was usable for further experimentation after 14 DIV.

2.13. Calcium Imaging

To determine whether inhibiting Cx43 in the mouse spinal cord had any impact on spinal MNs, the collected medium of the slice cultures was introduced to the cultured WT MN and incubated overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

The next day, the wells were washed and introduced to 1 µM of the calcium ion (Ca2+) fluorescence dye Fluo-4 AM (#F14201, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in FBS-free medium and incubated for 15 min. Using a Zeiss Axio Examiner fluorescent microscope, images were captured under various conditions, and the difference in Ca2+ signaling intensity was measured using ImageJ.

In a separate experiment, Fluo-4 was introduced to WT MNs. The MNs were then examined under the microscope, and a video recording was started. At the one-minute mark (application), the SN of SMA or SMA treated with Gap27 slice cultures was added to the cultures and recorded for an additional four minutes. The spike amplitude of all viable cells was measured as the difference between the highest point and the point of application. Measurements were done using ImageJ Software.

2.14. Glutamate Assay

To measure the glutamate level in the supernatants of slice cultures and transfected astrocyte cultures, a glutamate assay kit (#MAK004, Sigma Aldrich, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The total protein in the supernatants was measured using a BCA and normalized to the measured glutamate level and to their appropriate controls.

2.15. Statistical Analysis

For statistical analyses between two conditions, Student’s t-tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were applied; for analyses between two or more conditions, the one-way ANOVA was used. Normality was verified by applying the D’Agostino & Pearson test. Significances were defined at a value of ⁕ p < 0.05; ⁕⁕ p < 0.01; ⁕⁕⁕ p < 0.001. All values are given as mean ± standard deviation. All statistical analyses and their graphical presentations were made using GraphPad Prism 9. All graphical presentations of methodological approaches were done using biorender.com.

4. Discussion

This study identifies astrocytic Cx43 as a contributor of glutamate-driven MN loss in late-onset SMA. We demonstrate that SMN deficiency leads to a pronounced upregulation of Cx43 in spinal astrocytes, both in a murine and in human iPSC-derived model. Elevated Cx43 expression was accompanied by increased extracellular glutamate and abnormal MN Ca²⁺ responses, indicating enhanced excitotoxic stress. Pharmacological inhibition of Cx43 with the hemichannel blocker Gap27 effectively normalized glutamate levels and restored MN Ca²⁺ signaling to control values, establishing a direct functional link between astrocytic Cx43 and MN excitotoxicity in SMA.

Our findings highlight the importance of non-neuronal mechanisms in SMA pathogenesis. Although SMA is considered an MND caused by loss of SMN protein, growing evidence indicates that astrocytes critically modulate disease progression. Previous work has shown astrocytic activation and glutamate dysregulation preceding MN degeneration in late-onset SMA mice [

16,

17]. The present data extend these findings by identifying Cx43 as a central molecular contributor to this glial dysfunction.

Cx43 is the predominant connexin in astrocytes and forms both gap junctions and hemichannels that regulate intercellular signaling, ion homeostasis, and neurotransmitter clearance [

22,

24]. Under pathological conditions, excessive opening of Cx43 hemichannels results in uncontrolled release of glutamate, ATP, and other neuroactive molecules, thereby amplifying excitotoxicity and inflammation [

28]. Our results indicate that late-onset SMA condition promotes such aberrant Cx43 activity, leading to impaired glutamate buffering and excitotoxic stress on MNs. The reversal of these effects by Gap27 demonstrates that Cx43 hemichannels are functionally involved in the astrocyte-mediated toxicity observed in late-onset SMA.

At the molecular level, the early but transient increase in Cx43 mRNA and sustained protein overexpression suggest post-transcriptional dysregulation. This pattern aligns with the established function of SMN in RNA processing and transport [

29,

30] and supports the hypothesis that SMN deficiency interferes with the post-transcriptional regulation of astrocytic genes. Such mechanisms may contribute to the persistent elevation of Cx43 protein seen at symptomatic and late disease stages.

Notably, the upregulation of astrocytic Cx43 is not unique to SMA and has been described in other neurodegenerative and neuromuscular disorders, including ALS, Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, and Multiple Sclerosis [

15,

25,

31]. In ALS, Cx43-dependent hemichannel opening has been shown to promote MN degeneration, and its inhibition mitigates excitotoxic damage [

25]. Our study provides converging evidence that similar mechanisms operate in late-onset SMA, reinforcing the concept that Cx43-mediated astrocytic dysfunction is a common pathway contributing to MN loss across distinct MNDs.

Importantly, our experiments using human SMN-deficient astrocytes reproduced the findings obtained in mouse models, underscoring the translational relevance of this mechanism. Gap27 treatment normalized glutamate release in both systems, suggesting that pharmacological modulation of Cx43 may represent a potential therapeutic strategy. Such approaches could be especially valuable for late-onset SMA patients who are diagnosed at advanced stages, when SMN-enhancing therapies alone show limited efficacy [

32].

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. The study relies primarily on ex vivo and in vitro systems, which, while allowing controlled mechanistic analysis, may not fully capture the complexity of the in vivo spinal environment. In addition, although Gap27 efficiently inhibited pathological Cx43 activity in culture, its limited bioavailability and tissue penetration pose challenges for clinical application [

33]. Future work should therefore employ conditional, astrocyte-specific Cx43 knockout models and evaluate clinically tested gap junction modulators such as Tonabersat [

34,

35,

36] in different phenotype-related SMA models to determine their therapeutic potential.

Beyond glutamate regulation, Cx43 hemichannels also control the release of ATP and cytokines [

37,

38], which may further exacerbate neuroinflammation and MN injury. Thus, astrocytic Cx43 likely contributes to late-onset SMA pathology through multiple converging mechanisms that warrant deeper investigation.

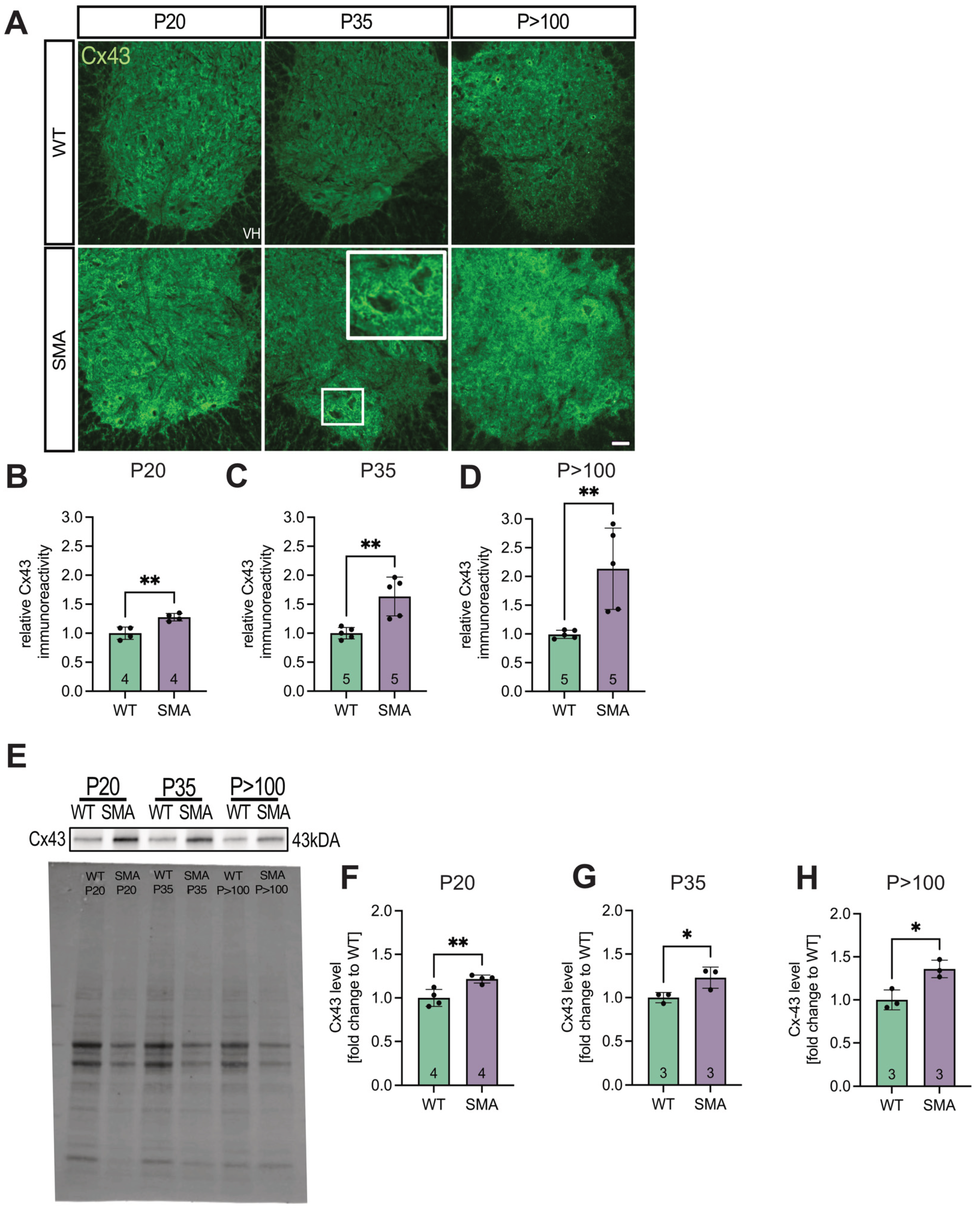

Figure 1.

SMA spinal cord analyses showed an increased expression of Cx43 compared to WT. (A) Spinal cord slices of SMA and WT mice at ages P20, P35, and P>100 (n = 4-5 animals) were stained for Cx43 (green). Imaging studies showed an increased expression of Cx43 in SMA at P20 (** p = 0.0035). This increased expression was also visible at P35 and P>100 (** p = 0.0094 and p = 0.0071, respectively). Higher accumulation of Cx43 was evident around motor neurons, particularly in SMA, pointed out in the SMA P35 image. Scale bar 20 μm. (B) For WB studies, lumbar spinal cord tissue of n = 3-4 animals was used. Results were then adjusted to the total protein value. At P35 (* p = 0.0309) and P>100 (** p = 0.0037), Cx43 expression was increased in SMA compared to WT. At P20, we identified no difference in the Cx43 expression (p = 0.1115). Analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests. Full blots are shown in the Additional file. Abbreviations: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; WB, Western blot; WT, wild-type; P, postnatal day.

Figure 1.

SMA spinal cord analyses showed an increased expression of Cx43 compared to WT. (A) Spinal cord slices of SMA and WT mice at ages P20, P35, and P>100 (n = 4-5 animals) were stained for Cx43 (green). Imaging studies showed an increased expression of Cx43 in SMA at P20 (** p = 0.0035). This increased expression was also visible at P35 and P>100 (** p = 0.0094 and p = 0.0071, respectively). Higher accumulation of Cx43 was evident around motor neurons, particularly in SMA, pointed out in the SMA P35 image. Scale bar 20 μm. (B) For WB studies, lumbar spinal cord tissue of n = 3-4 animals was used. Results were then adjusted to the total protein value. At P35 (* p = 0.0309) and P>100 (** p = 0.0037), Cx43 expression was increased in SMA compared to WT. At P20, we identified no difference in the Cx43 expression (p = 0.1115). Analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests. Full blots are shown in the Additional file. Abbreviations: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; WB, Western blot; WT, wild-type; P, postnatal day.

Figure 2.

qPCR analyses showed an increase in Cx43 mRNA expression early in the pathogenesis. (A) Whole lumbar spinal cord tissue of SMA and WT mice at P20, P35, and P>100 were prepared, and qPCR analyses were performed. The results suggested an increase in mRNA expression at P20 in SMA compared to WT (* p = 0.029). (B&C) No significant difference was visible between SMA and WT at later stages (P35, p = 0.9485; P>100, p = 0.0542). n = 3 individual animals, analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests. Abbreviations: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; WT, wild-type; P, postnatal day.

Figure 2.

qPCR analyses showed an increase in Cx43 mRNA expression early in the pathogenesis. (A) Whole lumbar spinal cord tissue of SMA and WT mice at P20, P35, and P>100 were prepared, and qPCR analyses were performed. The results suggested an increase in mRNA expression at P20 in SMA compared to WT (* p = 0.029). (B&C) No significant difference was visible between SMA and WT at later stages (P35, p = 0.9485; P>100, p = 0.0542). n = 3 individual animals, analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests. Abbreviations: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; WT, wild-type; P, postnatal day.

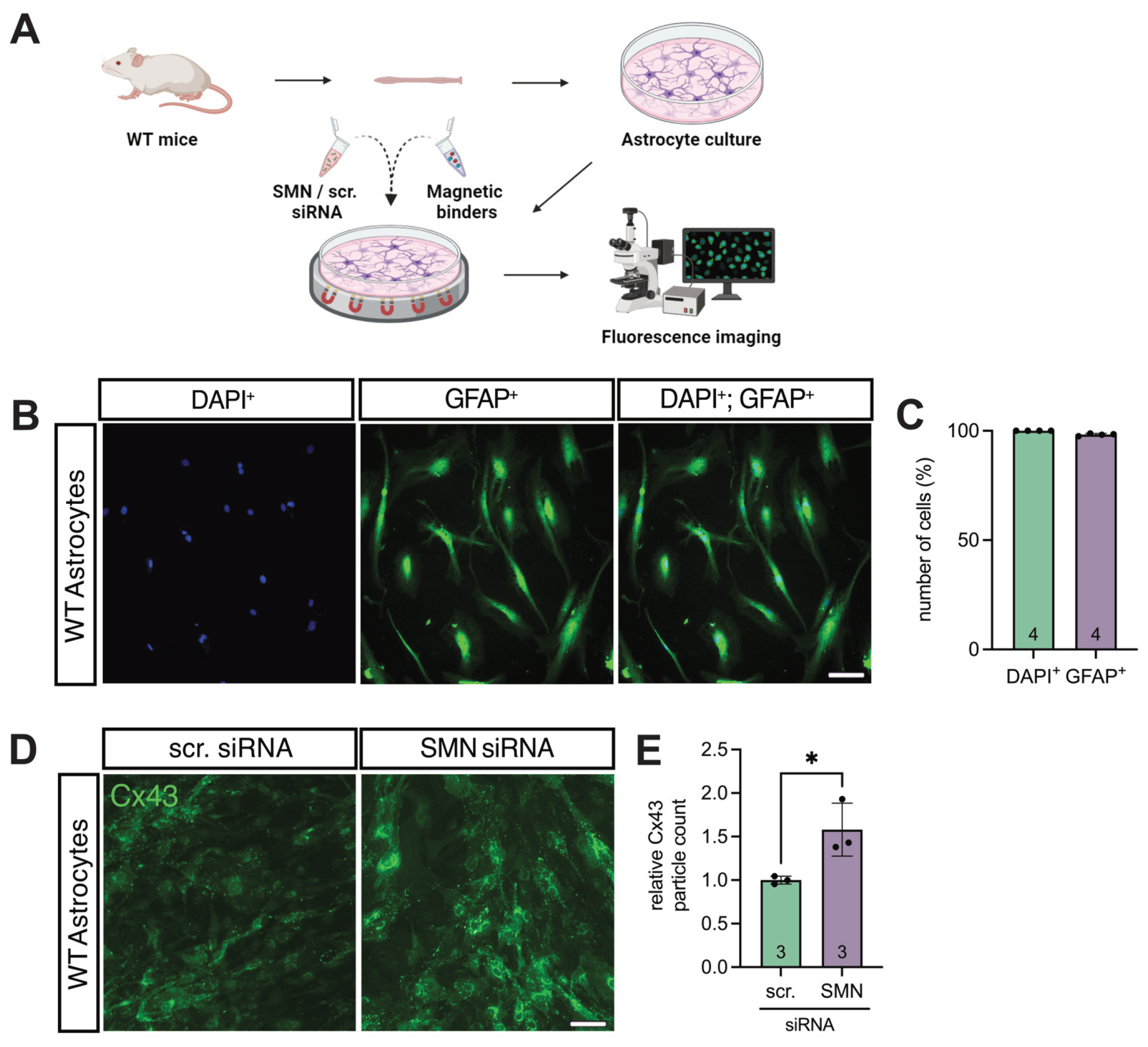

Figure 3.

Overexpression of Cx43 in a model of in vitro-induced SMN-deficiency in astrocytes. (A) Astrocytic cultures were prepared from the lumbar part of the spinal cord of WT mice and transfected with SMN-siRNA to induce SMN-deficiency. Appropriate control cultures were transfected with scr-siRNA and fluorescence imaging was conducted. (B&C) GFAP (red) and DAPI (blue) staining of the same cultures demonstrated an astrocyte proportion of >98% compared to all viable cells; n = 4 individual cultures for each of the three animals, scale bar 50 μm. (D&E) Immunostaining of Cx43 (green) in transfected astrocytes. Analysis showed a 1.6-fold increase in Cx43 expression in SMN-deficient cells compared to control (* p = 0.03; n = 3 independent experiments for each of the three individual animals, analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests, scale bar 50 μm. Abbreviations: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SMN, survival of motor neuron; WT, wild-type.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of Cx43 in a model of in vitro-induced SMN-deficiency in astrocytes. (A) Astrocytic cultures were prepared from the lumbar part of the spinal cord of WT mice and transfected with SMN-siRNA to induce SMN-deficiency. Appropriate control cultures were transfected with scr-siRNA and fluorescence imaging was conducted. (B&C) GFAP (red) and DAPI (blue) staining of the same cultures demonstrated an astrocyte proportion of >98% compared to all viable cells; n = 4 individual cultures for each of the three animals, scale bar 50 μm. (D&E) Immunostaining of Cx43 (green) in transfected astrocytes. Analysis showed a 1.6-fold increase in Cx43 expression in SMN-deficient cells compared to control (* p = 0.03; n = 3 independent experiments for each of the three individual animals, analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests, scale bar 50 μm. Abbreviations: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SMN, survival of motor neuron; WT, wild-type.

Figure 4.

SMN deficient hiAstrocytes showed a higher Cx43 expression compared to control, reversible by Gap27. (A&B) Culture clarity and iPSC induction success were proven by GFAP staining, showing >98% astrocytes in the cultures. (C&D) hiAstrocytes were transfected with SMN-siRNA to induce SMN deficiency. Appropriate controls were transfected with scr-siRNA. Staining for SMN showed an effective decrease compared to control (p = 0.006). (E&F) Staining for Cx43 showed an increased expression after SMN-knockdown (p = 0.02), which was reduced after treatment with the Cx43 inhibitor Gap27 (p = 0.007). n = 3-7 independent experiments, analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests and ANOVA, scale bar 50 μm. Abbreviations: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; E, embryonal day; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; WT, wild-type.

Figure 4.

SMN deficient hiAstrocytes showed a higher Cx43 expression compared to control, reversible by Gap27. (A&B) Culture clarity and iPSC induction success were proven by GFAP staining, showing >98% astrocytes in the cultures. (C&D) hiAstrocytes were transfected with SMN-siRNA to induce SMN deficiency. Appropriate controls were transfected with scr-siRNA. Staining for SMN showed an effective decrease compared to control (p = 0.006). (E&F) Staining for Cx43 showed an increased expression after SMN-knockdown (p = 0.02), which was reduced after treatment with the Cx43 inhibitor Gap27 (p = 0.007). n = 3-7 independent experiments, analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests and ANOVA, scale bar 50 μm. Abbreviations: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; E, embryonal day; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; WT, wild-type.

Figure 5.

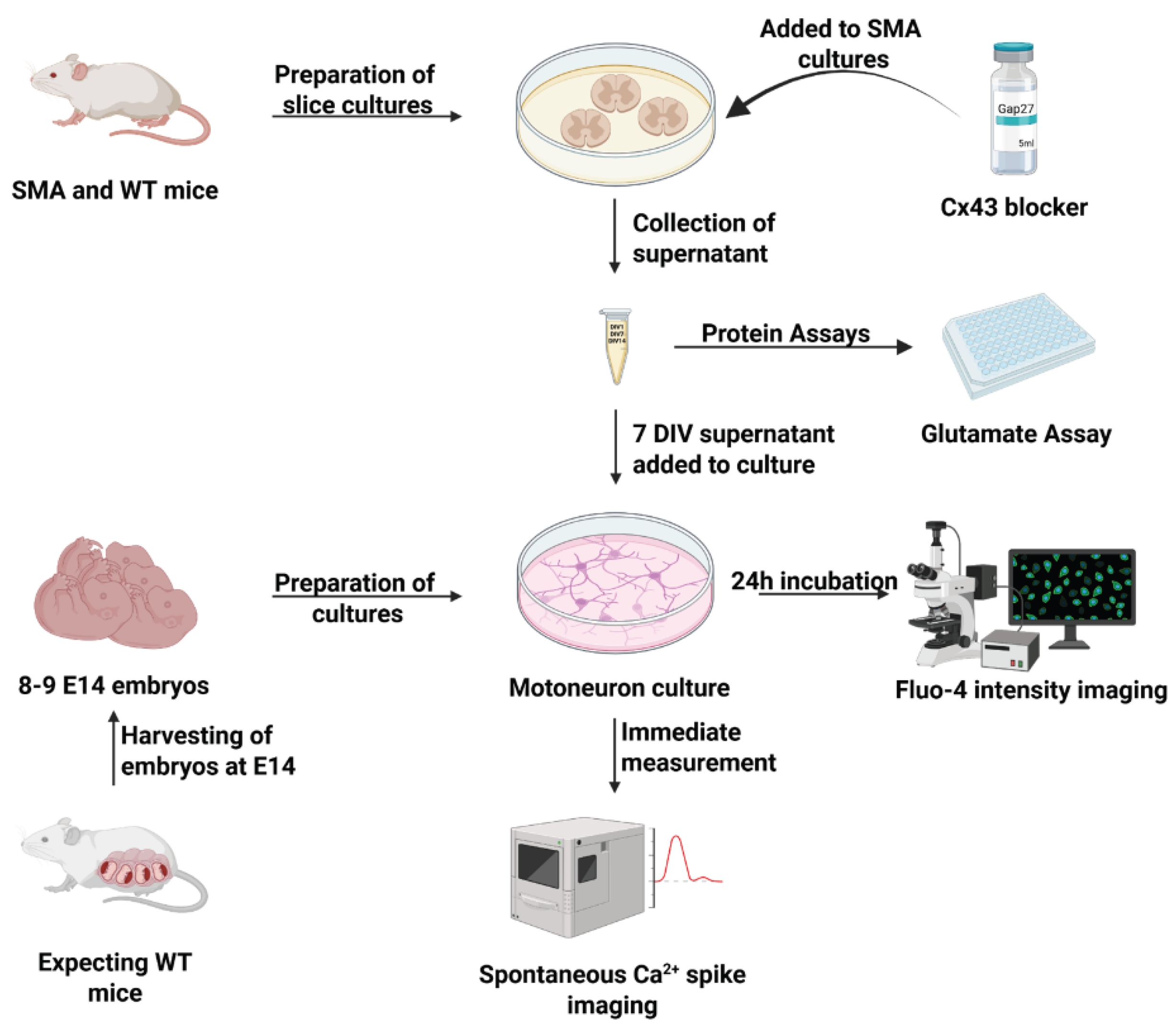

Preparation of organotypic spinal cord slice cultures as an in vitro model of SMA. Slice cultures from WT and SMA mice were prepared. Supernatant was removed at 1 DIV, and half of the SMA cultures were treated with Gap27. Supernatant was again removed at 7 DIV and at 14 DIV. Embryonal motor neuronal cultures were prepared and, after maturation, the 7 DIV supernatant was introduced to the cultures. After 24-h incubation, the Ca2+ intensity was measured. In another experiment, the Ca2+ spike amplitude was measured immediately after applilacation of 7 DIV supernatants. All supernatants were assayed for glutamate with glutamate assays. Abbreviations: DIV, days in vitro; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; E, embryonal day; WT, wild-type.

Figure 5.

Preparation of organotypic spinal cord slice cultures as an in vitro model of SMA. Slice cultures from WT and SMA mice were prepared. Supernatant was removed at 1 DIV, and half of the SMA cultures were treated with Gap27. Supernatant was again removed at 7 DIV and at 14 DIV. Embryonal motor neuronal cultures were prepared and, after maturation, the 7 DIV supernatant was introduced to the cultures. After 24-h incubation, the Ca2+ intensity was measured. In another experiment, the Ca2+ spike amplitude was measured immediately after applilacation of 7 DIV supernatants. All supernatants were assayed for glutamate with glutamate assays. Abbreviations: DIV, days in vitro; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; E, embryonal day; WT, wild-type.

Figure 6.

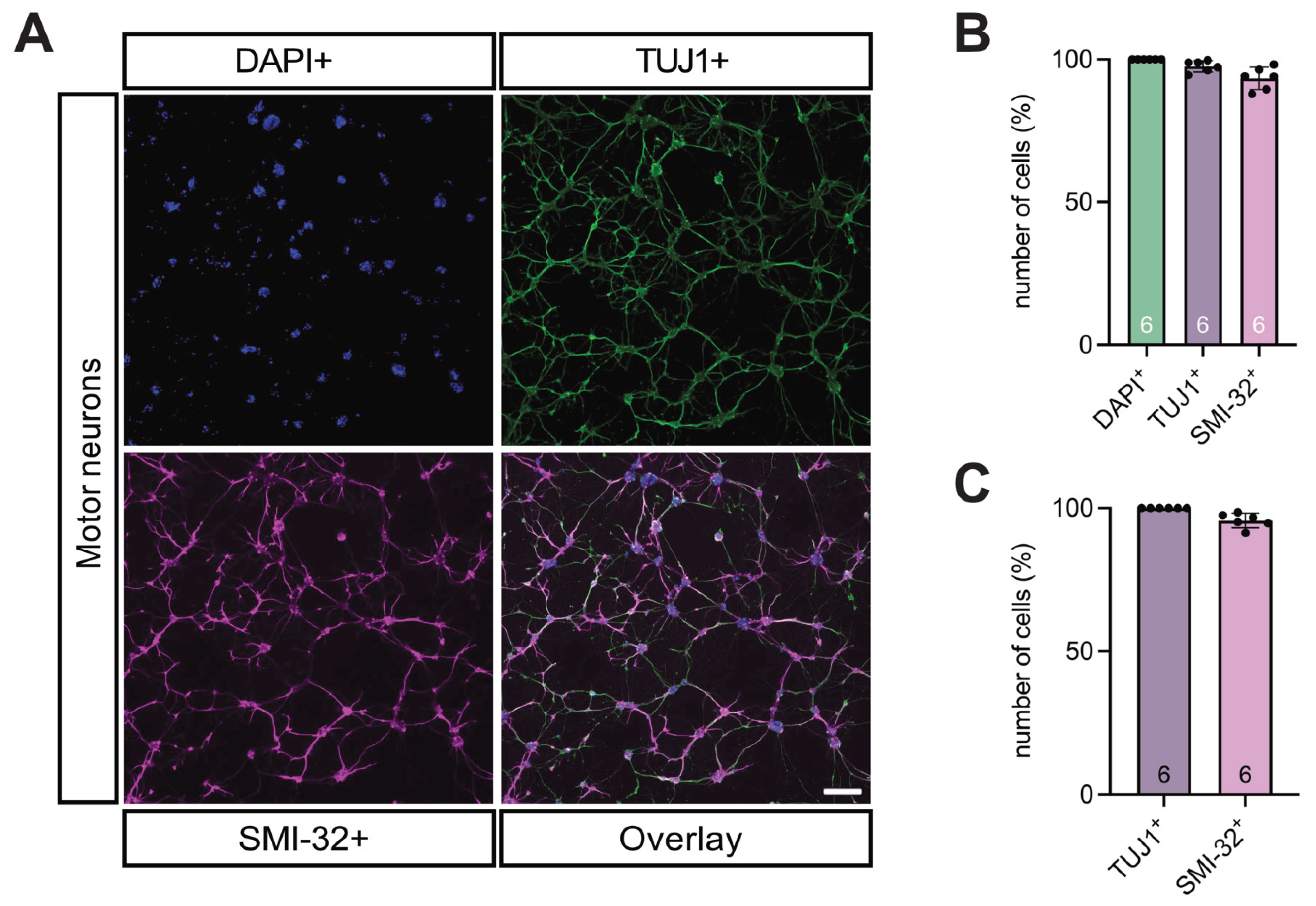

Clarity of motor neuron cultures were tested using TUJ1 and SMI-32 staining. (A-C) DAPI (blue), TUJ1 (green) for neurons, and SMI-32 (magenta) for MN staining of the neuronal cultures demonstrated that all viable cells in the culture were comprised of neurons (> 97%) and motor neurons (> 93%). MNs made up > 95% of all neurons in the culture. n = 6 independent experiments from six individual cultures, each prepared from 8-9 WT E14 embryos, scale bar 100 μm. Abbreviations: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; E, embryonal day.

Figure 6.

Clarity of motor neuron cultures were tested using TUJ1 and SMI-32 staining. (A-C) DAPI (blue), TUJ1 (green) for neurons, and SMI-32 (magenta) for MN staining of the neuronal cultures demonstrated that all viable cells in the culture were comprised of neurons (> 97%) and motor neurons (> 93%). MNs made up > 95% of all neurons in the culture. n = 6 independent experiments from six individual cultures, each prepared from 8-9 WT E14 embryos, scale bar 100 μm. Abbreviations: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; E, embryonal day.

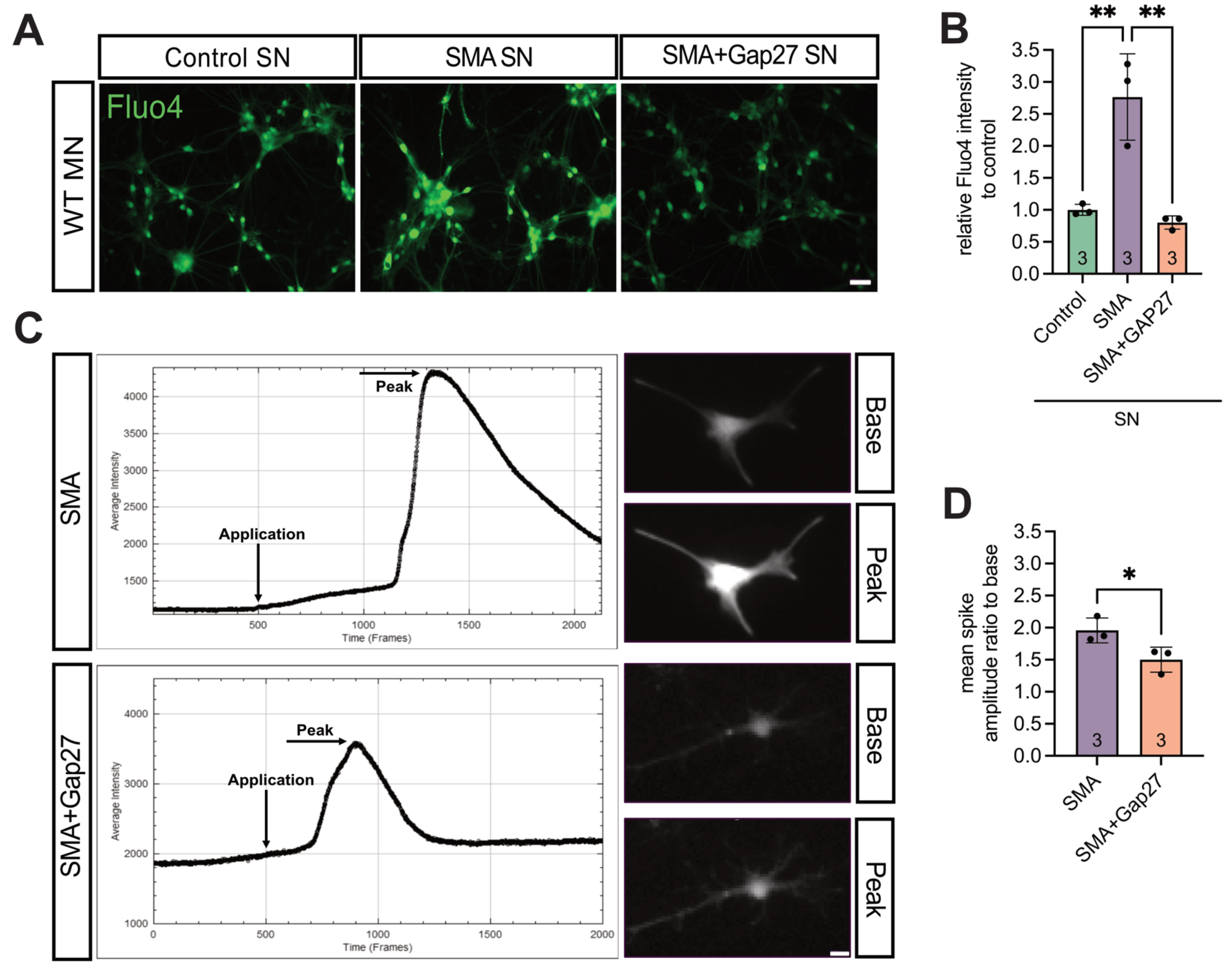

Figure 7.

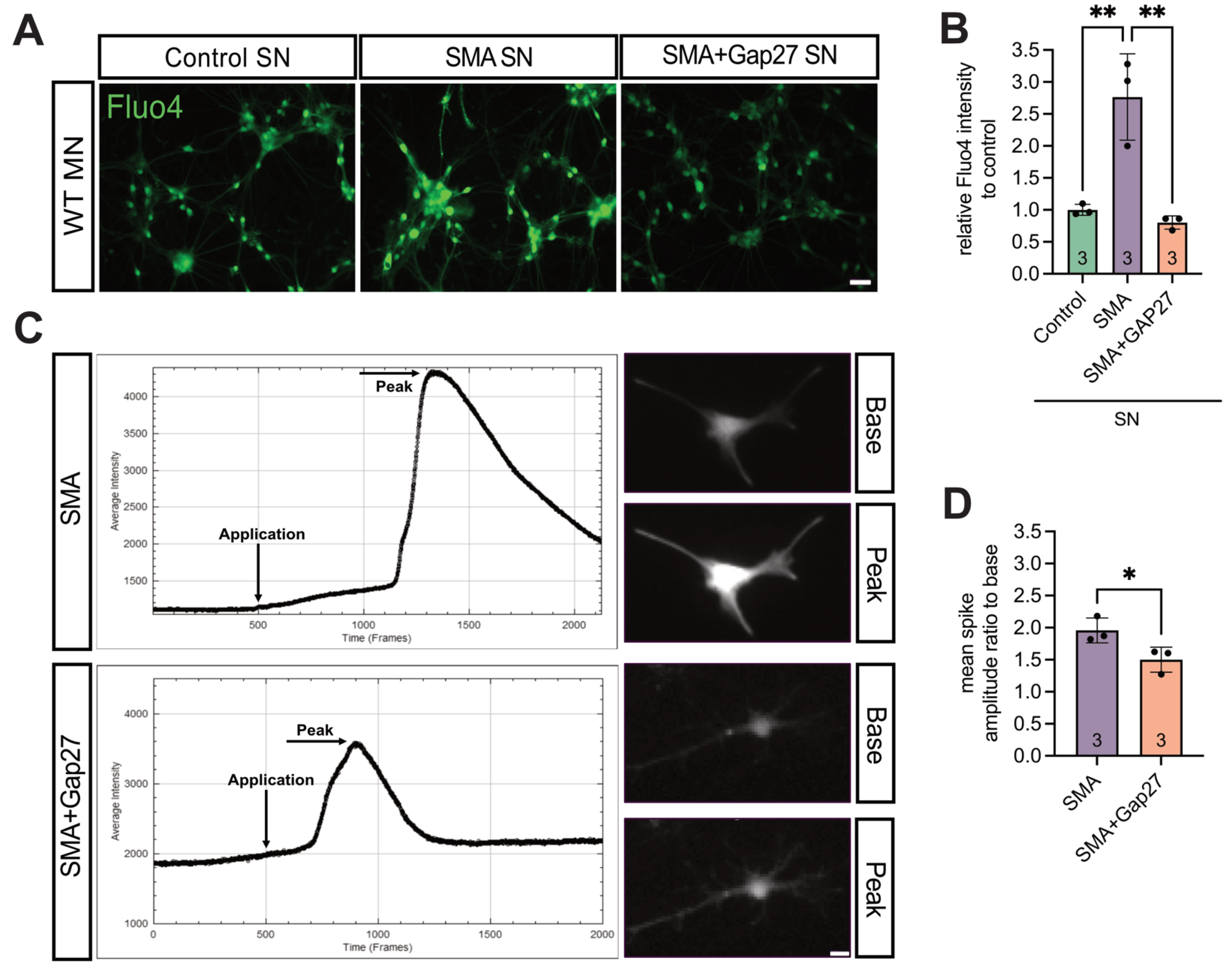

Inhibition of Cx43 in SMA led to significantly lower WT-like Ca2+ response in MN. (A&B) 24h Incubation of WT MNs with the supernatant from SMA slice cultures (SMA) caused a significant increase in the Ca2+ response compared to incubation with the supernatant from WT mice slice culture (Control) (** p = 0.0076), measured by Fluo-4 staining to visualize Ca2+ processes (green). MNs incubated with SMA slice culture supernatant that had Cx43 inhibited (SMA + Gap27) caused a significant decrease in the Ca2+ response compared to incubation with the untreated SMA supernatant (** p = 0.002). SMA + Gap27 SN showed a result comparable to control (p = 0.82). n = three independent experiments, scale bar 100 μm. (C&D) After acquiring the results from (A), the change in the spontaneous Ca2+ response in MNs to SN of SMA or SMA + Gap27 slice cultures was measured. Acute introduction of SMA + Gap27 slice culture supernatant to WT MNs (Application, at 500 frames = 1min) showed a significant decrease in Ca2+ spike amplitude compared to treatment with SMA supernatant, visualized with Fluo-4 staining in all vial cells (* p < 0.05). n = 3 independent experiments, scale bar 10 μm, analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests and ANOVA. Abbreviations: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; WT, wild-type.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of Cx43 in SMA led to significantly lower WT-like Ca2+ response in MN. (A&B) 24h Incubation of WT MNs with the supernatant from SMA slice cultures (SMA) caused a significant increase in the Ca2+ response compared to incubation with the supernatant from WT mice slice culture (Control) (** p = 0.0076), measured by Fluo-4 staining to visualize Ca2+ processes (green). MNs incubated with SMA slice culture supernatant that had Cx43 inhibited (SMA + Gap27) caused a significant decrease in the Ca2+ response compared to incubation with the untreated SMA supernatant (** p = 0.002). SMA + Gap27 SN showed a result comparable to control (p = 0.82). n = three independent experiments, scale bar 100 μm. (C&D) After acquiring the results from (A), the change in the spontaneous Ca2+ response in MNs to SN of SMA or SMA + Gap27 slice cultures was measured. Acute introduction of SMA + Gap27 slice culture supernatant to WT MNs (Application, at 500 frames = 1min) showed a significant decrease in Ca2+ spike amplitude compared to treatment with SMA supernatant, visualized with Fluo-4 staining in all vial cells (* p < 0.05). n = 3 independent experiments, scale bar 10 μm, analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests and ANOVA. Abbreviations: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; WT, wild-type.

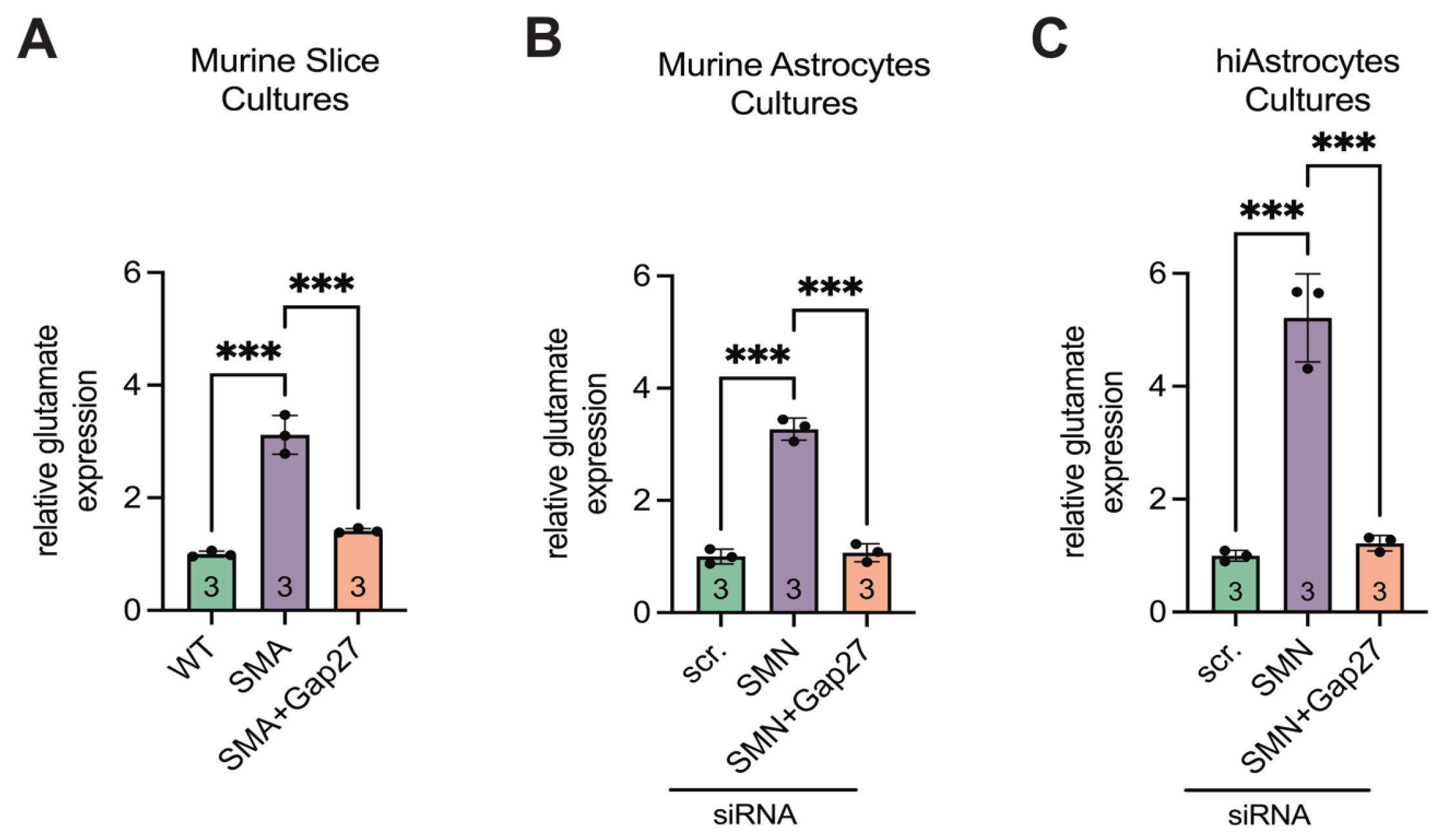

Figure 8.

Glutamate assay showed increased expression in SMA, reversible by Inhibiting Cx43. (A) Slice cultures showed higher glutamate levels in SMA compared to WT (*** p < 0.001). Gap27 treatment in SMA resulted in a decrease in glutamate levels (*** p < 0.001) to the level of WT (p = 0.1). (B) Murine cell cultures also showed higher glutamate levels when SMN was knocked down (*** p < 0.001), with the levels decreasing with Gap27 (*** p < 0.001) to the level of WT (p = 0.85). (C) Similarly, hiAstrocytes showed increased glutamate levels when SMN was knocked down (*** p < 0.001). This significantly decreased after treatment with Gap27 (p < 0.001) to the level of control (p = 0.92). Analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests. n = 3 independent experiments. Abbreviations: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMN, survival of motor neuron; WT, wild-type. hiAstrocytes, human induced astrocytes.

Figure 8.

Glutamate assay showed increased expression in SMA, reversible by Inhibiting Cx43. (A) Slice cultures showed higher glutamate levels in SMA compared to WT (*** p < 0.001). Gap27 treatment in SMA resulted in a decrease in glutamate levels (*** p < 0.001) to the level of WT (p = 0.1). (B) Murine cell cultures also showed higher glutamate levels when SMN was knocked down (*** p < 0.001), with the levels decreasing with Gap27 (*** p < 0.001) to the level of WT (p = 0.85). (C) Similarly, hiAstrocytes showed increased glutamate levels when SMN was knocked down (*** p < 0.001). This significantly decreased after treatment with Gap27 (p < 0.001) to the level of control (p = 0.92). Analysis was done using unpaired Student’s t-tests. n = 3 independent experiments. Abbreviations: SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMN, survival of motor neuron; WT, wild-type. hiAstrocytes, human induced astrocytes.