1. Introduction

The convergence of the opioid crisis and criminal justice involvement represents a growing public health emergency, driving the unprecedented levels of fatal overdoses globally. The National Academies have emphasized the justice system as an essential component in the fight against the opioid epidemic (National Academies of Sciences et al., 2019). While the effectiveness of evidence-based treatments such as medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) is well established, their utilization in the United States remains suboptimal, particularly among justice-involved populations (Stahler et al., 2022). Factors that influence positive outcomes and/or adverse events while receiving substance treatment, including criminal justice status, are still not well understood. Stigma and paternalism within the criminal justice system may influence an individual’s choice to seek treatment (Debbaut, 2022).

Despite policy momentum, fewer than 6% of justice-involved individuals receive community-based MOUD (Guastaferro et al., 2022). Incarceration may temporarily disrupt and reduce substance use, although clinical rates of substance concerns remain post-release (Tangney et al., 2016). There remains a critical gap in understanding the experiences and treatment outcomes of justice-involved individuals once they return to the community post-release or engage in outpatient treatment.

1.1. Medication for Opioid Use Disorder in the Criminal Justice System

MOUD is the gold standard treatment for OUD yet remains underused among justice-involved individuals. There is consistent research evidence that criminal justice referrals to medication-based treatment for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) remain low, and justice-involved individuals who successfully access care are under-researched. Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) is a chronic medical condition, warranting long-term treatment maintenance. Long-term medication-based treatment is associated with improved outcomes and is recommended by the American Society of Addiction Medicine in clinical guidelines (Kraus et al., 2011; Wakeman et al., 2020). Long-term quality of life measures show access to MOUD increases abstinence rates and decreases overdoses, emergency department visits, and arrests (Dever et al., 2024). Analysis of a national data set comparing multiple treatment exposures concluded that buprenorphine and methadone pathways (compared to nonpharmacologic treatments or no treatment) were the only modality associated with a reduced risk of overdose and serious opioid-related acute care incidents (Wakeman et al., 2020). Despite MOUD’s effectiveness, initiating and retaining patients in treatment remains challenging. On average, treatment duration is often under six months (Kennedy et al., 2022; Samples et al., 2018), and 12-month retention rates range widely, from 26% to 91% (Timko et al., 2016).

Justice-involved individuals, who frequently present with complex medical and behavioral health profiles, are significantly less likely to be referred to MOUD programs (Krawczyk et al., 2017). These individuals represent a more complex patient population and experience higher rates of opioid use disorder, overdose, financial struggles, and other adverse outcomes (Krawczyk et al., 2017; Langabeer et al., 2024), including an increased risk of overdose post-incarceration (Binswanger et al., 2016; Grella et al., 2021). Structural, attitudinal, and logistical barriers limit their access, and when they do receive treatment, it is often less comprehensive or discontinued during incarceration (Staton et al., 2023). Moreover, stigma from providers and lack of knowledge from justice personnel further hinders uptake (Booty et al., 2023; Finlay et al., 2016).

1.2. Treatment Utilization

Existing research largely focuses on incarcerated populations or relies on administrative data that do not capture the nuances of clinical engagement. Criminal justice expenditures related to opioid overdose, misuse, and dependence have been estimated to total more than $14 billion in costs, largely driven by enforcement, adjudication, and custody rather than treatment (Florence et al., 2021). While approximately 6 million individuals with justice involvement had been referred to substance use treatment in the past year (Rowell-Cunsolo & Bellerose, 2021), the research does not always distinguish between treatment access and the extent of treatment utilization. There is a large void of research studies that examine the justice-involved status of patients enrolled in MOUD treatment, particularly in outpatient settings. An important limitation of the current literature is the predominant reliance on insurance claims data from commercial payers or public programs such as Medicaid and Medicare, which provide only a partial view of patient engagement in treatment (Zhang et al., 2022). Conclusions drawn solely from claims data limits generalizability to individuals with insurance-based access to care and fails to adequately represent the broader clinical landscape. To date, few studies have examined justice-involved populations receiving comprehensive MOUD treatment. This study investigates whether justice-involved individuals differ in their retention on MOUD within a community-based outpatient setting. Specifically, we aimed to identify demographic and clinical characteristics associated with criminal justice involvement and assess whether such involvement independently predicts retention in MOUD care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Study Sample

A retrospective cohort study was conducted to assess retention on buprenorphine/naloxone among individuals enrolled in a community-based outpatient program between January 2022 and April 2024. Participants were adults enrolled in an outpatient program in Houston, Texas, providing rapid access to buprenorphine/naloxone and comprehensive behavioral support. Referral sources included EMS overdose follow-ups, emergency departments, the criminal justice system, and self-referrals (Langabeer et al., 2021). MOUD was available to all participants regardless of justice status, and access to behavioral services was not contingent on MOUD uptake. At enrollment, all individuals were offered the opportunity to see a prescribing clinician, such as a medical doctor, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant, for an initial prescription of buprenorphine/naloxone. In addition to MOUD services, individuals received individual counseling, access to recovery support peer specialists, group counseling, and general case management and support for referrals. Inclusion criteria required participants to have filled at least one prescription for buprenorphine/naloxone after enrollment. Ethical approval was obtained from the university’s Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Criminal justice system (CJS) involvement was determined through a review of five program documentation fields: incarceration outcomes, new court case documentation, closed court case documentation, staff support in court, and documentation of current legal problems on the biopsychosocial intake. Participants were classified as CJS-involved if any of these indicators were positive at any point. A participant was classified as non-CJS involved if all five fields were negative.

2.2. Study Variables

The primary outcome was MOUD retention, defined as the number of days between the first and last continuous prescriptions for buprenorphine/naloxone, verified via the Texas Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PMP). Prescriptions were considered continuous if refilled within 45 days of the previous one. A standardized 7-day supply was assumed across the sample, given the variation in dosage and duration. This study did not capture engagement with other FDA-approved medications for OUD, including methadone or naltrexone. The secondary outcome involved a comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics between individuals with and without CJS involvement.

2.3. Moderating and Control Variables

Demographic variables included age, gender, race, ethnicity, veteran status, insurance status, and housing status. Clinical variables included age of opioid initiation, intravenous drug use history, primary opioid type (prescription or illicit), co-occurring substance use, overdose history, and prior MOUD experience. Behavioral engagement was assessed by the number of sessions with counselors, peers, or groups within the first 30- and 90-days post-enrollment. The total number of sessions served was a proxy for program participation.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Frequencies, means, medians, and proportions were calculated to describe the sample. Univariate comparisons were conducted using t-tests for normally distributed variables, Kruskal-Wallis equality of population rank tests for non-normally distributed variables, and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Pearson correlations were used for associations between continuous variables. For the univariate analyses of the two study outcomes, we tested multiple hypotheses, and the Bonferroni correction was applied to control for Type I error, indicating significance was a p ≤ 0.001.

Because MOUD days were non-normally distributed and heteroskedasticity of the observations was present, a non-parametric kernel regression model (Epanechnikov kernel function) was used to evaluate predictors of retention (Cattaneo & Jansson, 2018; Li et al., 2003; Li & Racine, 2004). This model included covariates with univariate significance of p ≤ 0.05, with bootstrapping to estimate confidence intervals. Variables in the model included housing status, intravenous drug use, opioid type, MOUD history, and program engagement. Considering variables “primary opioid taken was prescription” and “primary opioid taken was illegal” were significantly and inversely correlated, we included in the model only the former one, as it explained more variance and resulted in a better goodness-of-fit. CJS involvement was included as an a priori variable of interest.

An exploratory binary logistic regression model was constructed to identify predictors of our secondary outcome CJS involvement, including covariates with p ≤ 0.10 in univariate testing. The model goodness-of-fit was assessed using the Hosmer & Lemeshow test at χ2= 11.85 (df=8), p = 0.16. The CJS model included 341 observations and had an R-squared of 0.37. The use of the Bonferroni formula in this model indicated significance at a p ≤ 0.006. All analyses and graphical outputs were conducted using Stata/IC version 15.0 (Stata, 2017).

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

A total of 540 charts of adult participants in the program were reviewed. Participants had enrolled between January 3, 2022, and April 30, 2024. Ten (1.8%) participants were excluded from the analysis because they entered the program before the earliest date retrievable from the PMP database. Among the 530 participants, 163 (30.8%) were excluded because they did not have at least one prescription filled per the PMP. A total of 367 were included in this analysis, and we observed the mean (sd) age of this group was 35.2 (9.7) years.

3.2. MOUD Retention

Of the 367 participants, at the cutoff point of 180 days in the program, 133 (36.2%) remained on MOUD, 35 of which (10%) were involved in the CJS; equating to 38% retention at 180 days of the initial justice-involved group (n=91) as seen in

Table 1. We found that involvement in the CJS was significantly associated with the number of sessions served during the first 90 days. Participants involved in the CJS had a median (IQR) of 12 (4 – 20) sessions served while those not involved in the system had only a median (IQR) of 3 (0.5 – 8) sessions (

p ≤ 0.0001).

There were some notable differences in proportions of key substances used and clinical history between individuals with CJS involvement (n=91) and those without (n=276). Individuals involved in the CJS reported an earlier mean age of substance use initiation (18.2 years vs. 21.1 years; p = 0.007) and a higher proportion of use of heroin as the primary illicit drug (67.0% vs. 48.5%; p = 0.002).

3.3. Modeling MOUD Retention Outcomes

Retention in the program was measured by days using MOUD. For all the participants, we found this variable had a non-normal distribution with an unweighted mean (sd) of 203.9 (261) days and an unadjusted median (IQR) of days on MOUD at 61 (7 – 349) days.

Table 2 highlights the univariate analysis which indicated a significant and positive correlation between the total number of sessions served in the first 90 days in the program and days on MOUD (p ≤ 0.001).

3.4. Characteristics by Justice Involved Status

The exploratory multivariable binary logistic regression model included as dependent variable involvement in the CJS (yes/no) and as independent covariates: gender, race, age at first drug use, use of IV drugs, primary drug taken was prescription, primary drug taken was illegal, type of illicit drug consumed was heroin, first time on MOUD, and total number of sessions served in first 90 days in program. The model had satisfactory goodness of fit, and the number of sessions served was the only independent predictor found. Each additional session within the first 90 days was associated with a 10% increase in the odds of criminal justice involvement (OR = 1.10, 95% CI = (1.07 to 1.14), p ≤ 0.001). Suggesting individuals involved in CJS may have engaged more intensely early in treatment (

Table 3).

Multivariate Analysis CJ Involvement and Days on MOUD

Next, we constructed an exploratory multivariable non-parametric kernel regression model with the total days in MOUD as the dependent variable. The covariates included were: CJS involved, housing, history of use of IV drugs, primary opioid taken was prescription, first time on MOUD, total number of sessions served in the first 90 days in the program, primary opioid prescribed was hydrocodone, and primary other substance consumed was methamphetamine. The weighted mean days on MOUD in this group of patients was 201 days (95% CI = (172 to 234), p = 0.001). Three covariates had a significant impact on the days on MOUD. Compared to participants who had used MOUD before, first-time users of MOUD had significantly fewer days on MOUD (- 79.72, 95% CI =(-138.40 to -27.21), p = 0.001). Compared to those whose primary other substance consumed was not methamphetamine, participants who used this substance had significantly fewer days on MOUD (-104.21, 95% CI = (-165.03 to -45.73), p = 0.001). The number of sessions served in the first 90 days in the program was an independent predictor of days on MOUD; an increase of one activity during this period in the program would increase 10.81 days the total days on MOUD (10.81, 95% CI = (5.55 to 15.67), p = 0.001) shown in

Table 4.

3.5. Predictors of Days on MOUD

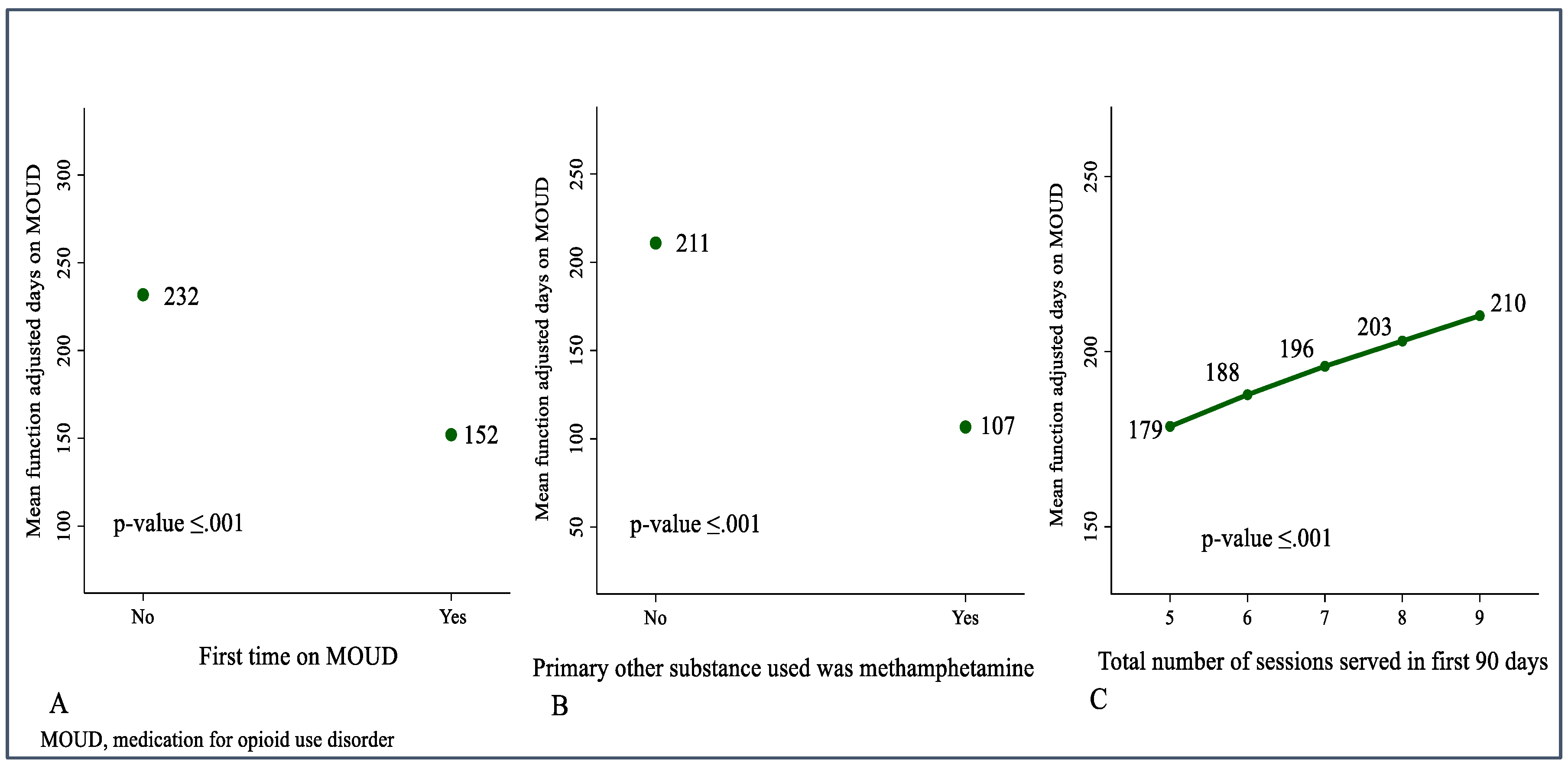

The predictive margins of the three independent predictors observed are depicted in

Figure 1. Assuming the rest of the covariates stay at mean values, the analyses of margins indicated the adjusted mean days predicted for those who used MOUD for the first time was 152 (95% CI= (111 to 187),

p ≤ 0.001) vs. 232 days (95% CI= (194 to 269),

p ≤ 0.001) for those who had MOUD before. Participants who had not used methamphetamines had a predicted adjusted mean of 211 days (95% CI= (184 to 241),

p ≤ 0.001) while participants using this drug had an adjusted mean of only 107 days (95% CI= (57 to 170),

p ≤ 0.001). Increasing the number of sessions served during the first 90 days in program from five (the median number of the study group) to seven sessions resulted in an increment of 17 days, from a predicted adjusted mean of 179 days (95% CI = (150 to 215),

p ≤ 0.001) at five sessions to an adjusted mean of 196 days (95% CI= (164 to 236?0,

p ≤ 0.001) when seven sessions were served. See

Figure 1 (A, B, C).

4. Discussion

Retention in MOUD treatment remains a national challenge. Our results support prior research which demonstrates that many individuals discontinue treatment before the six-month mark (Kennedy et al., 2022). However, the weighted mean within the cohort in this study reached 201 days. This is an encouraging outcome in comparison to national trends. The total number of sessions served in the first 90 days in the program served as a proxy of engagement of the participants with extended services (e.g., peer recovery coaching, individual therapy, group support). This outcome was significantly associated with increased retention in the treatment program which supports prior evidence that MOUD, when paired with comprehensive, individualized services, produces more durable outcomes (Ahmed et al., 2022; Pivovarova et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022). We also observed that first-time users of MOUD and the concurrent consumption of methamphetamine with opioids significantly reduced the retention in the program.

Regarding CJS as our secondary outcome of interest, we did not find CJS to be an independent determinant of days on MOUD. However, the criminal justice relationship may be more nuanced. This study showed some differences in substance use and MOUD history between groups. Individuals involved in the CJS experienced more severe substance use profiles, marked by higher proportions of earlier initiation of opioids, heroin use and injection/intravenous as the reported route of administration. A higher proportion of individuals in the CJ system were first-time MOUD participants, and the predictive model for retention highlighted that, compared to previous use of MOUD, first-time MOUD utilization was significantly associated with a lower weighted mean function of days in MOUD.

Unexpectedly, engagement in behavioral services was associated with increased odds of being CJS involved. This may suggest that justice-involved individuals, who are often under legal or social pressure to demonstrate recovery progress, are more motivated or mandated to engage with these services, independent of their retention timeline on MOUD. A final finding worth emphasizing is the impact of polysubstance use, particularly concurrent stimulant use, on treatment retention. Individuals reporting methamphetamine use experienced significantly lower retention. This mirrors national data from the “fourth wave” of the opioid crisis, characterized by concurrent use of opioids and stimulants (Ciccarone, 2021). With no FDA-approved pharmacotherapy for stimulant use disorder, this subgroup remains vulnerable and underserved.

The convergence of opioid use disorder and justice system involvement persists across the continuum, from incarceration to specialty courts and community supervision. Justice-involved individuals remain significantly less likely to access MOUD, with referral rates consistently below 6% (Guastaferro et al., 2022; Krawczyk et al., 2017). In our study, individuals with prior exposure to MOUD exhibited significantly better retention than first-time participants, many of whom were justice-involved. While this may signal increasing access for justice-involved individuals, it also highlights the critical role of education and targeted support for first-time MOUD recipients.

Although all participants in our study had access to MOUD, uptake among justice-involved individuals was still incomplete, indicating persistent gaps in utilization (Yatsco, Garza, et al., 2020). Justice staff, from probation officers to court personnel, play an essential role in facilitating MOUD access, yet stigma and misinformation about buprenorphine continue to impede progress. Evidence from systematic reviews supports the efficacy of MOUD even in the absence of counseling (Mattick et al., 2009, 2014), underscoring the need to prioritize treatment initiation and expand referrals. Our analytic approach was to conduct an exploratory nonparametric kernel regression model, a procedure that belongs to the family of analytic tools known as random forest models. Considered superior to traditional linear regression models, the random forest models have the capacity to account for nonlinear relationships and multicollinearity, providing a robust framework for identifying key predictors within complex behavioral health data (Fife & D’Onofrio, 2022).

5. Conclusions

The strong partnerships between justice stakeholders and the outpatient program in this study likely contributed to our ability to analyze a meaningful subset of justice-involved clients. Such collaboration is key to reducing systemic barriers to care (Yatsco, Champagne-Langabeer, et al., 2020). Decades of advocacy have established MOUD as a first-line, evidence-based treatment. Efforts to shift cultural perceptions and eliminate stigma must continue to ensure that justice-involved individuals are not excluded from these lifesaving therapies. Our findings support the broader conclusion that, when provided access to comprehensive, coordinated treatment services, justice-involved individuals can achieve similar retention outcomes to their non-justice-involved peers. Investing in such programs is a public health and equity imperative.

This study focused solely on buprenorphine, one of three FDA-approved MOUDs, and some individuals classified as non-MOUD may have received methadone or naltrexone elsewhere. As a retrospective, non-randomized study drawn from a voluntary treatment program, findings may be influenced by self-selection and are not generalizable beyond this specific setting. MOUD was offered to all participants, but engagement varied, with some opting into non-pharmacological services only. Program structure and community context may limit applicability to other regions.

While peer support services were available, their specific role in influencing justice-involved participants’ treatment outcomes warrants further study. The broader literature offers limited insight into the experiences of justice-involved individuals who do enter MOUD programs in community settings. Future research should explore why some justice-involved clients choose medication treatment while others do not, ideally through qualitative inquiry. Expanding justice-status data collection and replicating this analysis across diverse settings will be essential to deepen understanding and inform equitable MOUD implementation strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y.; methodology, M.C-T., F.R.V., A.S.C.; validation, F.V., A.S.C.; formal analysis, M.C-T., F.R.V.; investigation, A.Y., F.R.V.; resources, T. C-L; data curation, A.S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Y., F.R.V.; writing—review and editing, A.Y., F.R.V., A.S.C., M.C-T., J. R. L., T.C-L; visualization, M.C-T., F.R.V.; supervision, J.R.L., T.C-L.; project administration, A.Y., A.S.C. J.R.L.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston protocol code HSC-SBMI-17-1021 date of approval: January 10, 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to all the participants who shared their time and their stories to make this research possible. Special thanks to Rakshitha Vijendra.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmed, F. Z., Andraka-Christou, B., Clark, M. H., Totaram, R., Atkins, D. N., & Del Pozo, B. (2022). Barriers to medications for opioid use disorder in the court system: provider availability, provider “trustworthiness,” and cost. Health Justice, 10(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Binswanger, I. A., Stern, M. F., Yamashita, T. E., Mueller, S. R., Baggett, T. P., & Blatchford, P. J. (2016). Clinical risk factors for death after release from prison in Washington State: a nested case-control study. Addiction, 111(3), 499-510. [CrossRef]

- Booty, M. D., Harp, K., Batty, E., Knudsen, H. K., Staton, M., & Oser, C. B. (2023). Barriers and facilitators to the use of medication for opioid use disorder within the criminal justice system: Perspectives from clinicians. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 149, 209051. [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, M. D., & Jansson, M. (2018). Kernel-based semiparametric estimators: small bandwidth asymptotics and bootstrap consistency. Econometrica, 86(3), 955-995. [CrossRef]

- Ciccarone, D. (2021). The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 34(4), 344-350. [CrossRef]

- Debbaut, S. (2022). The legitimacy of criminalizing drugs: Applying the ‘harm principle’ of John Stuart Mill to contemporary decision-making. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 68, 100508. [CrossRef]

- Dever, J. A., Hertz, M. F., Dunlap, L. J., Richardson, J. S., Wolicki, S. B., Biggers, B. B.,…Guy, G. P. (2024). The Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Study: Methods and Initial Outcomes From an 18-Month Study of Patients in Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. Public Health Reports, 139(4), 484-493. [CrossRef]

- Finlay, A. K., Harris, A. H., Rosenthal, J., Blue-Howells, J., Clark, S., McGuire, J.,…Binswanger, I. (2016). Receipt of pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder by justice-involved U.S. Veterans Health Administration patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 160, 222-226. [CrossRef]

- Florence, C., Luo, F., & Rice, K. (2021). The economic burden of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose in the United States, 2017. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 218, 108350. [CrossRef]

- Grella, C. E., Ostlie, E., Scott, C. K., Dennis, M. L., Carnevale, J., & Watson, D. P. (2021). A scoping review of factors that influence opioid overdose prevention for justice-involved populations. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, Policy, 16(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Guastaferro, W. P., Koetzle, D., Lutgen-Nieves, L., & Teasdale, B. (2022). Opioid agonist treatment recipients within criminal justice-involved populations. Substance Use & Misuse, 57(5), 698-707. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A. J., Wessel, C. B., Levine, R., Downer, K., Raymond, M., Osakue, D.,…Liebschutz, J. M. (2022). Factors Associated with Long-Term Retention in Buprenorphine-Based Addiction Treatment Programs: a Systematic Review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(2), 332-340. [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M. L., Alford, D. P., Kotz, M. M., Levounis, P., Mandell, T. W., Meyer, M.,…Wyatt, S.A. (2011). Statement of the american society of addiction medicine consensus panel on the use of buprenorphine in office-based treatment of opioid addiction. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 5(4), 254-263. [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, N., Picher, C. E., Feder, K. A., & Saloner, B. (2017). Only one in twenty justice-referred adults in specialty treatment for opioid use receive methadone or buprenorphine. Health Affairs (Millwood), 36(12), 2046-2053. [CrossRef]

- Langabeer, J. R., Champagne-Langabeer, T., Yatsco, A. J., O’Neal, M. M., Cardenas-Turanzas, M., Prater, S.,…Chambers, K. A. (2021). Feasibility and outcomes from an integrated bridge treatment program for opioid use disorder. Journal of The American College of Emergency Physicians Open, 2(2), e12417. [CrossRef]

- Langabeer, J. R., Vega, F. R., Cardenas-Turanzas, M., Cohen, A. S., Lalani, K., & Champagne-Langabeer, T. (2024). How financial beliefs and behaviors influence the financial health of individuals struggling with opioid use disorder. Behavioral Sciences (Basel), 14(5). [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Lu, X., & Ullah, A. (2003). Multivariate local polynomial regression for estimating average derivatives. Journal of Nonparametric Statistics, 15(4-5), 607-624. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Racine, J. (2004). Cross-validated local linear nonparametric regression. Statistica Sinica, 14(2), 485-512. https://www3.stat.sinica.edu.tw/statistica/oldpdf/A14n29.pdf.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineeering, and Medicine. (2019). Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Pivovarova, E., Taxman, F. S., Boland, A. K., Smelson, D. A., Lemon, S. C., & Friedmann, P. D. (2023). Facilitators and barriers to collaboration between drug courts and community-based medication for opioid use disorder providers. Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment, 147, 208950. [CrossRef]

- Rowell-Cunsolo, T. L., & Bellerose, M. (2021). Utilization of substance use treatment among criminal justice-involved individuals in the United States. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 125, 108423. [CrossRef]

- Samples, H., Williams, A. R., Olfson, M., & Crystal, S. (2018). Risk factors for discontinuation of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorders in a multi-state sample of Medicaid enrollees. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 95, 9-17. [CrossRef]

- Stahler, G. J., Mennis, J., Stein, L. A. R., Belenko, S., Rohsenow, D. J., Grunwald, H. E.,…Martin, R. A. (2022). Treatment outcomes associated with medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) among criminal justice-referred admissions to residential treatment in the U.S., 2015-2018. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 236.

- Stata. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. In. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LLC.

- Staton, M., Pike, E., Tillson, M., & Lofwall, M. R. (2023). Facilitating factors and barriers for use of medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD) among justice-involved individuals in rural Appalachia. Journal of Community Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. P., Folk, J. B., Graham, D. M., Stuewig, J. B., Blalock, D. V., Salatino, A.,…Moore, K. E. (2016). Changes in inmates’ substance use and dependence from pre-incarceration to one year post-release. Journal of Criminal Justice, 46, 228-238. [CrossRef]

- Timko, C., Schultz, N. R., Cucciare, M. A., Vittorio, L., & Garrison-Diehn, C. (2016). Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: A systematic review. Journal of Addiction Diseases, 35(1), 22-35. [CrossRef]

- Wakeman, S. E., Larochelle, M. R., Ameli, O., Chaisson, C. E., McPheeters, J. T., Crown, W. H.,…Sanghavi, D. M. (2020). Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Network Open, 3(2), e1920622. [CrossRef]

- Yatsco, A. J., Champagne-Langabeer, T., Holder, T. F., Stotts, A. L., & Langabeer, J. R. (2020). Developing interagency collaboration to address the opioid epidemic: A scoping review of joint criminal justice and healthcare initiatives. International Journal of Drug Policy, 83, 102849. [CrossRef]

- Yatsco, A. J., Garza, R. D., Champagne-Langabeer, T., & Langabeer, J. R. (2020). Alternatives to arrest for illicit opioid use: a joint criminal justice and healthcare treatment collaboration. Substance Abuse Resaerch and Treament, 14, 1178221820953390. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Tossone, K., Ashmead, R., Bickert, T., Bailey, E., Doogan, N. J.,…Bonny, A. E. (2022). Examining differences in retention on medication for opioid use disorder: An analysis of Ohio Medicaid data. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 136, 108686. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).