Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

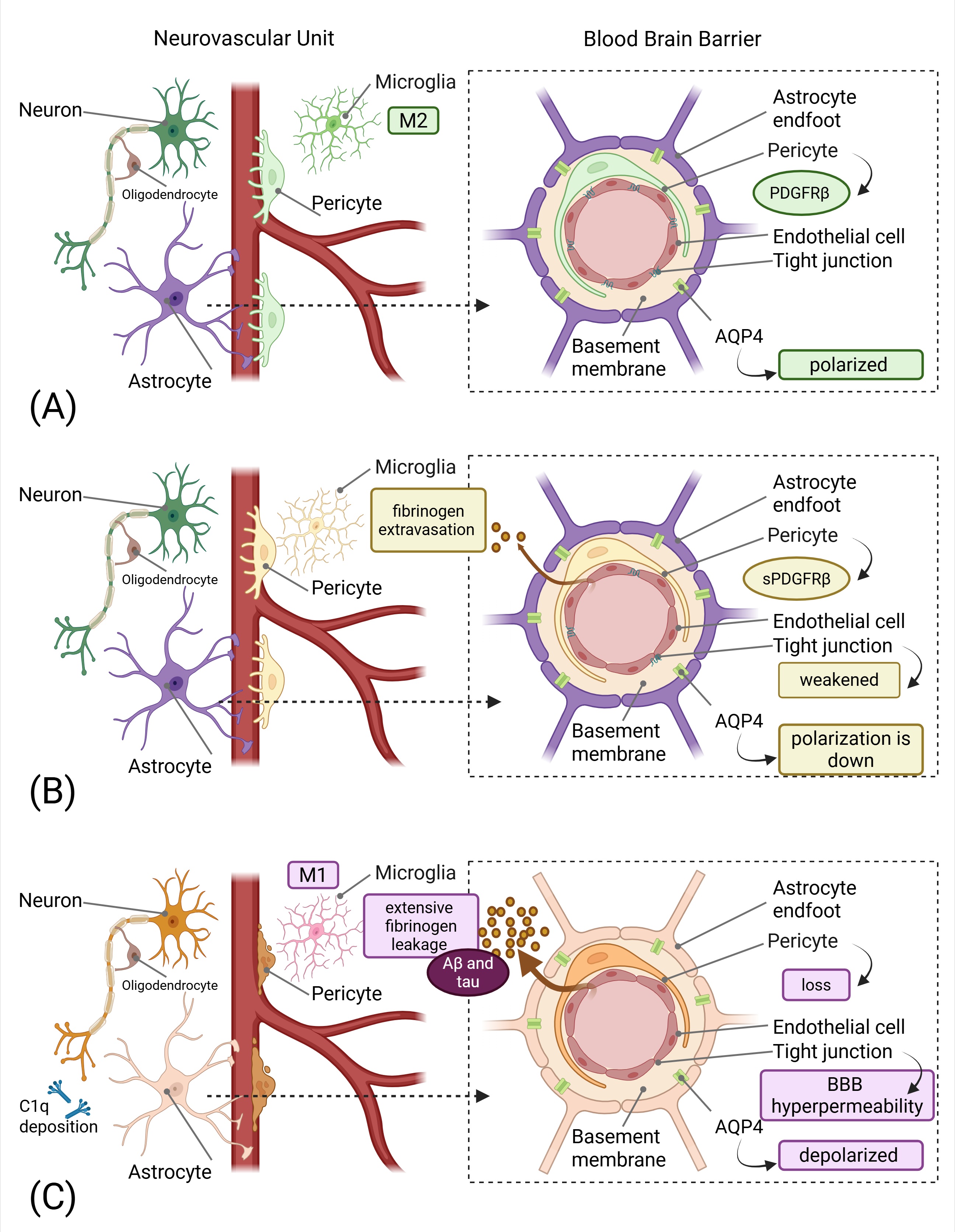

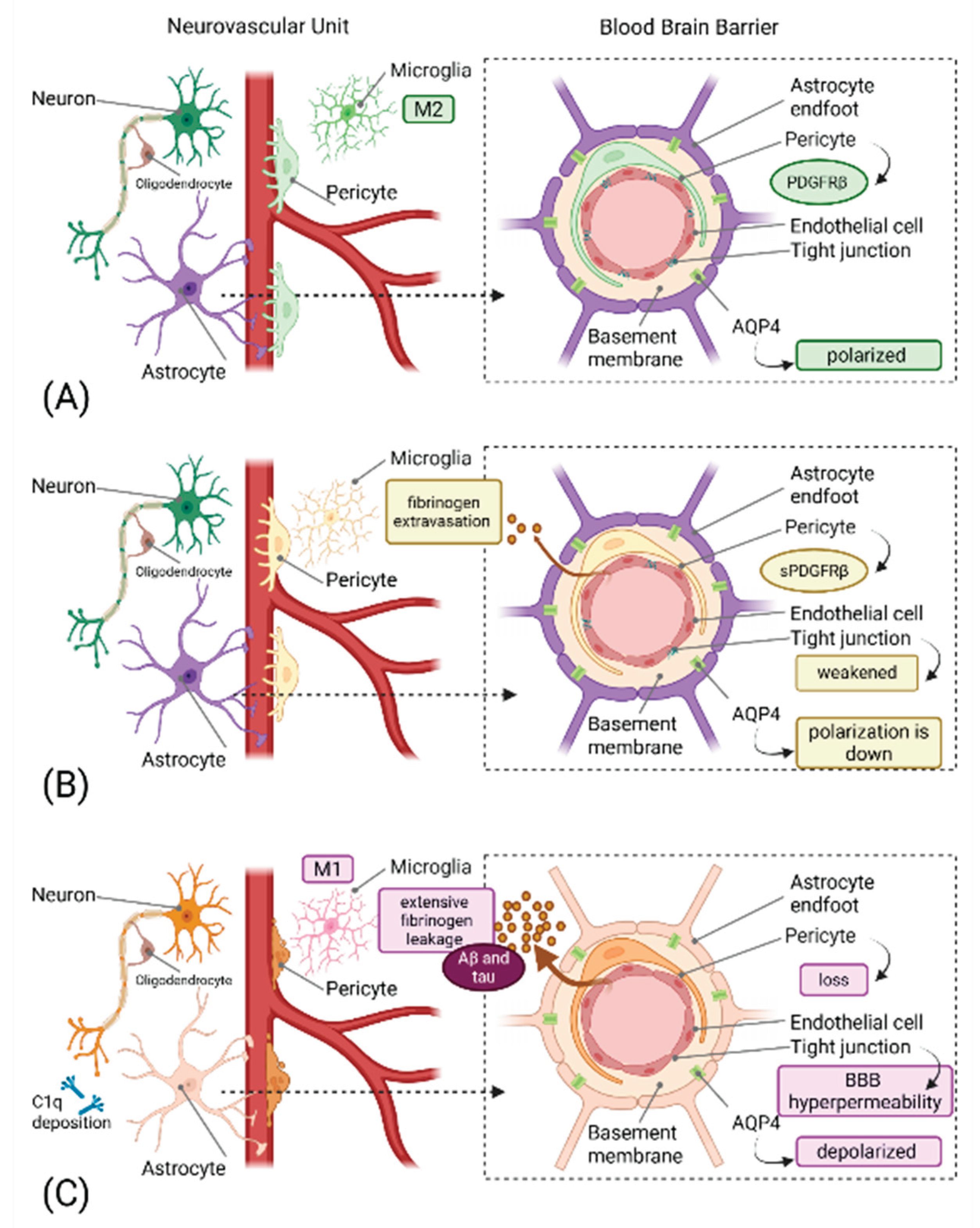

2. Pathophysiology of Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction

2.1. The Neurovascular Unit as a Therapeutic Target

| Biomarker | Source/Location | Pathophysiological Role | Clinical Significance | Detection Method | Key References |

| sPDGFRβ | CSF, released from injured pericytes | Indicates pericyte injury and BBB breakdown; correlates with neuroinflammation | Elevated in early-stage neurodegenerative disorders; correlates with cognitive decline and BBB dysfunction (QAlb) | ELISA, MSD electrochemiluminescence | [12,13,14,15] |

| CSF/Plasma Albumin Ratio (QAlb) | CSF and plasma | Reflects BBB permeability; increased ratio indicates BBB breakdown | Correlates with age, pericyte damage, and neuroinflammation; elevated in MCI and AD | Nephelometry, ELISA | [12,13,16] |

| C1q | Brain tissue, synapses (microglia-derived) | Tags synapses for complement-mediated elimination; initiates classical complement cascade | Increased and localized to synapses before plaque deposition in AD; associated with early synapse loss | Immunohistochemistry, Western blot | [17,18,19] |

| C3/iC3b | Brain tissue, synapses (astrocyte and microglia-derived) | Opsonizes synapses for microglial phagocytosis via CR3 receptor | Elevated in vulnerable brain regions; C3 deficiency protects against age-related synapse loss | Immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry | [18,19,20] |

| AQP4 Polarization Index | Astrocytic perivascular endfeet | Maintains glymphatic fluid flow; loss of polarization impairs waste clearance | Depolarization correlates with disease progression and impaired Aβ clearance | Immunofluorescence microscopy | [21,22,23] |

| CSF YKL-40 | CSF (astrocyte activation marker) | Indicates astrocytic activation and neuroinflammation | Elevated in AD and correlates with BBB dysfunction and PDGFRβ | ELISA | [24,25] |

| CSF GFAP | CSF (astrocyte marker) | Reflects astrocytic reactivity and glial activation | Increased with age and neuroinflammation; associated with BBB dysfunction | ELISA, Simoa | [26] |

| miR-124 | Plasma, CSF, brain tissue | Anti-inflammatory microRNA; maintains microglial quiescence | Downregulated in neurodegeneration; loss promotes M1 microglial polarization | qRT-PCR, sequencing | [27] |

| miR-155 | Plasma, CSF, brain tissue | Pro-inflammatory microRNA; promotes neuroinflammation | Upregulated in MS and AD; correlates with disease severity | qRT-PCR, sequencing | [28,29] |

| VEGF-C | CSF, brain tissue | Regulates meningeal lymphatic vessel function and lymphangiogenesis | Reduced levels associated with impaired brain clearance; therapeutic target | ELISA, Western blot | [30,31] |

| CSF Fibrinogen | CSF (blood-derived) | BBB leakage marker; promotes neuroinflammation | Elevated in AD; correlates with pericyte loss and reduced oxygenation | ELISA, immunohistochemistry | [12] |

2.2. Pericyte Dysfunction: The Primary Pathogenic Event

2.3. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor as a Dual-Acting Therapeutic Target

2.4. The Glymphatic-Lymphatic Interface

2.5. Aquaporin-4 Polarity Loss: A Therapeutic Target

2.6. Meningeal Lymphatic Vessels: A Novel Drainage Target

3. Neuroinflammation and the Tripartite Synapse

3.1. Microglial Dysfunction and Synaptic Clearance

3.2. Complement-Mediated Synaptic Pruning

3.3. MicroRNA-Mediated Inflammation Control

4. Discussion

4.1. Inadequacy of Protein-Centric Approaches

4.2. Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability as an Overlooked Target

4.3. Inflammation-Mediated Neurovascular Damage

4.4. Precision Medicine Approaches to Neurovascular Dysfunction

4.5. Molecular Pathway-Based Therapeutic Targets

4.6. Future Directions and Research Priorities

5. Conclusion

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| APOE4 | Apolipoprotein Epsilon 4 |

| AQP4 | Aquaporin-4 |

| ARG-1 | Arginase 1 |

| BBB | Blood Brain Barrier |

| C/EBPα | CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein alpha |

| C1q | Complement component 1q |

| C3 | Complement component 3 |

| C5aR1 | C5a Receptor 1 |

| CD200-CD200R | CD200-CD200 Receptor |

| CR3 | Complement Receptor 3 |

| CREB1 | cAMP Response Element Binding Protein 1 |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| IL-10 | Interleukin 10 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1 beta |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| miR-124 | microRNA 124 |

| miR-155 | microRNA 155 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa B |

| PDGF-BB | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB |

| PDGFRβ | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor-β |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase |

| PU.1 | PU.1 (also known as SPI1) |

| Qalb | CSF/Plasma Albumin Ratio |

| Ser276 | Serine at position 276 |

| sPDGFRβ | soluble Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor-β |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| TREM2 | Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid cells 2 |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Espay, A.J. Models of Precision Medicine for Neurodegeneration. Handb Clin Neurol 2023, 192, 21–34, doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-85538-9.00009-2.

- Huang, S.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Guo, Y.; Du, J.; Ren, P.; Wu, B.-S.; Feng, J.-F.; Cheng, W.; Yu, J.-T. Glymphatic System Dysfunction Predicts Amyloid Deposition, Neurodegeneration, and Clinical Progression in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 3251–3269, doi:10.1002/alz.13789.

- Sweeney, M.D.; Sagare, A.P.; Zlokovic, B.V. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Alzheimer Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14, 133–150, doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2017.188.

- Chen, T.; Dai, Y.; Hu, C.; Lin, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Zeng, L.; Li, S.; Li, W. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of the Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Fluids Barriers CNS 2024, 21, 60, doi:10.1186/s12987-024-00557-1.

- Yu, X.; Ji, C.; Shao, A. Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 334, doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00334.

- Kugler, E.C.; Greenwood, J.; MacDonald, R.B. The “Neuro-Glial-Vascular” Unit: The Role of Glia in Neurovascular Unit Formation and Dysfunction. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 732820, doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.732820.

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Xu, W.; Pan, Y.; Gao, S.; Dong, X.; Zhang, J.H.; Shao, A. Persistent Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction: Pathophysiological Substrate and Trigger for Late-Onset Neurodegeneration After Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 581, doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00581.

- van Vliet, E.A.; Marchi, N. Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction as a Mechanism of Seizures and Epilepsy during Aging. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 1297–1313, doi:10.1111/epi.17210.

- Najjar, S.; Pearlman, D.M.; Devinsky, O.; Najjar, A.; Zagzag, D. Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction with Blood-Brain Barrier Hyperpermeability Contributes to Major Depressive Disorder: A Review of Clinical and Experimental Evidence. J Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 142, doi:10.1186/1742-2094-10-142.

- Najjar, S.; Pahlajani, S.; De Sanctis, V.; Stern, J.N.H.; Najjar, A.; Chong, D. Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction and Blood-Brain Barrier Hyperpermeability Contribute to Schizophrenia Neurobiology: A Theoretical Integration of Clinical and Experimental Evidence. Front Psychiatry 2017, 8, 83, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00083.

- Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Pacheco-Herrero, M.; Martínez-Gómez, P.A.; Campa-Córdoba, B.B.; Apátiga-Pérez, R.; Villegas-Rojas, M.M.; Harrington, C.R.; de la Cruz, F.; Garcés-Ramírez, L.; Luna-Muñoz, J. The Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 2022, doi:10.3390/ijms22042022.

- Miners, J.S.; Kehoe, P.G.; Love, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K. CSF Evidence of Pericyte Damage in Alzheimer’s Disease Is Associated with Markers of Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction and Disease Pathology. Alzheimers Res Ther 2019, 11, 81, doi:10.1186/s13195-019-0534-8.

- Nation, D.A.; Sweeney, M.D.; Montagne, A.; Sagare, A.P.; D’Orazio, L.M.; Pachicano, M.; Sepehrband, F.; Nelson, A.R.; Buennagel, D.P.; Harrington, M.G.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown Is an Early Biomarker of Human Cognitive Dysfunction. Nat Med 2019, 25, 270–276, doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0297-y.

- Sweeney, M.D.; Sagare, A.P.; Pachicano, M.; Harrington, M.G.; Joe, E.; Chui, H.C.; Schneider, L.S.; Montagne, A.; Ringman, J.M.; Fagan, A.M.; et al. A Novel Sensitive Assay for Detection of a Biomarker of Pericyte Injury in Cerebrospinal Fluid. Alzheimers Dement 2020, 16, 821–830, doi:10.1002/alz.12061.

- Vrillon, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Bouaziz-Amar, E.; Mouton-Liger, F.; Cognat, E.; Dumurgier, J.; Lilamand, M.; Karikari, T.K.; Prevot, V.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Dissection of Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction through CSF PDGFRβ and Amyloid, Tau, Neuroinflammation, and Synaptic CSF Biomarkers in Neurodegenerative Disorders. EBioMedicine 2025, 115, 105694, doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2025.105694.

- Montagne, A.; Barnes, S.R.; Sweeney, M.D.; Halliday, M.R.; Sagare, A.P.; Zhao, Z.; Toga, A.W.; Jacobs, R.E.; Liu, C.Y.; Amezcua, L.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in the Aging Human Hippocampus. Neuron 2015, 85, 296–302, doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.032.

- Stephan, A.H.; Madison, D.V.; Mateos, J.M.; Fraser, D.A.; Lovelett, E.A.; Coutellier, L.; Kim, L.; Tsai, H.-H.; Huang, E.J.; Rowitch, D.H.; et al. A Dramatic Increase of C1q Protein in the CNS during Normal Aging. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 13460–13474, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1333-13.2013.

- Shi, Q.; Colodner, K.J.; Matousek, S.B.; Merry, K.; Hong, S.; Kenison, J.E.; Frost, J.L.; Le, K.X.; Li, S.; Dodart, J.-C.; et al. Complement C3-Deficient Mice Fail to Display Age-Related Hippocampal Decline. J Neurosci 2015, 35, 13029–13042, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1698-15.2015.

- Hong, S.; Beja-Glasser, V.F.; Nfonoyim, B.M.; Frouin, A.; Li, S.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Merry, K.M.; Shi, Q.; Rosenthal, A.; Barres, B.A.; et al. Complement and Microglia Mediate Early Synapse Loss in Alzheimer Mouse Models. Science 2016, 352, 712–716, doi:10.1126/science.aad8373.

- Presumey, J.; Bialas, A.R.; Carroll, M.C. Complement System in Neural Synapse Elimination in Development and Disease. Adv Immunol 2017, 135, 53–79, doi:10.1016/bs.ai.2017.06.004.

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Sci Transl Med 2012, 4, 147ra111, doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748.

- Smith, A.J.; Yao, X.; Dix, J.A.; Jin, B.-J.; Verkman, A.S. Test of the “glymphatic” Hypothesis Demonstrates Diffusive and Aquaporin-4-Independent Solute Transport in Rodent Brain Parenchyma. Elife 2017, 6, e27679, doi:10.7554/eLife.27679.

- Mestre, H.; Hablitz, L.M.; Xavier, A.L.; Feng, W.; Zou, W.; Pu, T.; Monai, H.; Murlidharan, G.; Castellanos Rivera, R.M.; Simon, M.J.; et al. Aquaporin-4-Dependent Glymphatic Solute Transport in the Rodent Brain. Elife 2018, 7, e40070, doi:10.7554/eLife.40070.

- Craig-Schapiro, R.; Perrin, R.J.; Roe, C.M.; Xiong, C.; Carter, D.; Cairns, N.J.; Mintun, M.A.; Peskind, E.R.; Li, G.; Galasko, D.R.; et al. YKL-40: A Novel Prognostic Fluid Biomarker for Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol Psychiatry 2010, 68, 903–912, doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.025.

- Janelidze, S.; Mattsson, N.; Stomrud, E.; Lindberg, O.; Palmqvist, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Hansson, O. CSF Biomarkers of Neuroinflammation and Cerebrovascular Dysfunction in Early Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2018, 91, e867–e877, doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006082.

- Benedet, A.L.; Milà-Alomà, M.; Vrillon, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Pascoal, T.A.; Lussier, F.; Karikari, T.K.; Hourregue, C.; Cognat, E.; Dumurgier, J.; et al. Differences Between Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein Levels Across the Alzheimer Disease Continuum. JAMA Neurol 2021, 78, 1471–1483, doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3671.

- Ponomarev, E.D.; Veremeyko, T.; Barteneva, N.; Krichevsky, A.M.; Weiner, H.L. MicroRNA-124 Promotes Microglia Quiescence and Suppresses EAE by Deactivating Macrophages via the C/EBP-α-PU.1 Pathway. Nat Med 2011, 17, 64–70, doi:10.1038/nm.2266.

- Guedes, J.R.; Custódia, C.M.; Silva, R.J.; de Almeida, L.P.; Pedroso de Lima, M.C.; Cardoso, A.L. Early miR-155 Upregulation Contributes to Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease Triple Transgenic Mouse Model. Hum Mol Genet 2014, 23, 6286–6301, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu348.

- Butovsky, O.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Cialic, R.; Krasemann, S.; Murugaiyan, G.; Fanek, Z.; Greco, D.J.; Wu, P.M.; Doykan, C.E.; Kiner, O.; et al. Targeting miR-155 Restores Abnormal Microglia and Attenuates Disease in SOD1 Mice. Ann Neurol 2015, 77, 75–99. Erratum in. Ann Neurol. 2015, 77: 1085. doi:10.1002/ana.24304.

- Da Mesquita, S.; Louveau, A.; Vaccari, A.; Smirnov, I.; Cornelison, R.C.; Kingsmore, K.M.; Contarino, C.; Onengut-Gumuscu, S.; Farber, E.; Raper, D.; et al. Functional Aspects of Meningeal Lymphatics in Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2018, 560, 185–191. Erratum in. Nature. 2018, 564: E7. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0368-8.

- Ahn, J.H.; Cho, H.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.H.; Ham, J.-S.; Park, I.; Suh, S.H.; Hong, S.P.; Song, J.-H.; Hong, Y.-K.; et al. Meningeal Lymphatic Vessels at the Skull Base Drain Cerebrospinal Fluid. Nature 2019, 572, 62–66, doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1419-5.

- Brown, L.S.; Foster, C.G.; Courtney, J.-M.; King, N.E.; Howells, D.W.; Sutherland, B.A. Pericytes and Neurovascular Function in the Healthy and Diseased Brain. Front Cell Neurosci 2019, 13, 282, doi:10.3389/fncel.2019.00282.

- Li, P.; Fan, H. Pericyte Loss in Diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 1931, doi:10.3390/cells12151931.

- Preis, L.; Villringer, K.; Brosseron, F.; Düzel, E.; Jessen, F.; Petzold, G.C.; Ramirez, A.; Spottke, A.; Fiebach, J.B.; Peters, O. Assessing Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction and Its Association with Alzheimer’s Pathology, Cognitive Impairment and Neuroinflammation. Alzheimers Res Ther 2024, 16, 172, doi:10.1186/s13195-024-01529-1.

- Smyth, L.C.D.; Highet, B.; Jansson, D.; Wu, J.; Rustenhoven, J.; Aalderink, M.; Tan, A.; Li, S.; Johnson, R.; Coppieters, N.; et al. Characterisation of PDGF-BB:PDGFRβ Signalling Pathways in Human Brain Pericytes: Evidence of Disruption in Alzheimer’s Disease. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 235, doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03180-8.

- Shen, J.; Xu, G.; Zhu, R.; Yuan, J.; Ishii, Y.; Hamashima, T.; Matsushima, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Takatsuru, Y.; Nabekura, J.; et al. PDGFR-β Restores Blood-Brain Barrier Functions in a Mouse Model of Focal Cerebral Ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019, 39, 1501–1515, doi:10.1177/0271678X18769515.

- Cercy, S.P. Pericytes and the Neurovascular Unit: The Critical Nexus of Alzheimer Disease Pathogenesis? Exploratory Research and Hypothesis in Medicine 2021, 6, 125–134, doi:10.14218/ERHM.2020.00062.

- Liu, T.; Guo, W.; Gong, M.; Zhu, L.; Cao, T.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, S.; et al. Pericyte Loss: A Key Factor Inducing Brain Aβ40 Accumulation and Neuronal Degeneration in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Exp Brain Res 2025, 243, 191, doi:10.1007/s00221-025-07134-4.

- Góra-Kupilas, K.; Jośko, J. The Neuroprotective Function of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF). Folia Neuropathologica 2005, 43, 31–39.

- Arendash, G.W.; Lin, X.; Cao, C. Enhanced Brain Clearance of Tau and Amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients by Transcranial Radiofrequency Wave Treatment: A Central Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF). J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 100, S223–S241, doi:10.3233/JAD-240600.

- Jiang, S.; Xia, R.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Gao, F. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors Enhance the Permeability of the Mouse Blood-Brain Barrier. PLoS One 2014, 9, e86407, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086407.

- Feng, Y.; Rhodes, P.G.; Bhatt, A.J. Neuroprotective Effects of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Following Hypoxic Ischemic Brain Injury in Neonatal Rats. Pediatr Res 2008, 64, 370–374, doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e318180ebe6.

- Zhang, H.-T.; Zhang, P.; Gao, Y.; Li, C.-L.; Wang, H.-J.; Chen, L.-C.; Feng, Y.; Li, R.-Y.; Li, Y.-L.; Jiang, C.-L. Early VEGF Inhibition Attenuates Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Ischemic Rat Brains by Regulating the Expression of MMPs. Mol Med Rep 2017, 15, 57–64, doi:10.3892/mmr.2016.5974.

- Tarasoff-Conway, J.M.; Carare, R.O.; Osorio, R.S.; Glodzik, L.; Butler, T.; Fieremans, E.; Axel, L.; Rusinek, H.; Nicholson, C.; Zlokovic, B.V.; et al. Clearance Systems in the Brain-Implications for Alzheimer Disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2015, 11, 457–470. Erratum in. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016, 12: 248. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2015.119.

- Gomolka, R.S.; Hablitz, L.M.; Mestre, H.; Giannetto, M.; Du, T.; Hauglund, N.L.; Xie, L.; Peng, W.; Martinez, P.M.; Nedergaard, M.; et al. Loss of Aquaporin-4 Results in Glymphatic System Dysfunction via Brain-Wide Interstitial Fluid Stagnation. Elife 2023, 12, e82232, doi:10.7554/eLife.82232.

- Ota, M.; Sato, N.; Nakaya, M.; Shigemoto, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Chiba, E.; Yokoi, Y.; Tsukamoto, T.; Matsuda, H. Relationships Between the Deposition of Amyloid-β and Tau Protein and Glymphatic System Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease: Diffusion Tensor Image Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2022, 90, 295–303, doi:10.3233/JAD-220534.

- Harrison, I.F.; Ismail, O.; Machhada, A.; Colgan, N.; Ohene, Y.; Nahavandi, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Fisher, A.; Meftah, S.; Murray, T.K.; et al. Impaired Glymphatic Function and Clearance of Tau in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Brain 2020, 143, 2576–2593, doi:10.1093/brain/awaa179.

- Hazzard, I.; Batiste, M.; Luo, T.; Cheung, C.; Lui, F. Impaired Glymphatic Clearance Is an Important Cause of Alzheimer’s Disease. Exploration of Neuroprotective Therapy 2024, 4, 401–410, doi:10.37349/ent.2024.00091.

- Murdock, M.H.; Yang, C.-Y.; Sun, N.; Pao, P.-C.; Blanco-Duque, C.; Kahn, M.C.; Kim, T.; Lavoie, N.S.; Victor, M.B.; Islam, M.R.; et al. Multisensory Gamma Stimulation Promotes Glymphatic Clearance of Amyloid. Nature 2024, 627, 149–156, doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07132-6.

- Liang, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Lin, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Huang, S.; Chen, L. Aerobic Exercise Improves Clearance of Amyloid-β via the Glymphatic System in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Res Bull 2025, 222, 111263, doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2025.111263.

- Qianqian, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Ye, Y.; Yu, C. Factors Affecting Aquaporin-4 and Its Regulatory Mechanisms in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology Asia 2025, 30, 361–367, doi:10.54029/2025kfk.

- Patabendige, A.; Chen, R. Astrocytic Aquaporin 4 Subcellular Translocation as a Therapeutic Target for Cytotoxic Edema in Ischemic Stroke. Neural Regen Res 2022, 17, 2666–2668, doi:10.4103/1673-5374.339481.

- Dai, J.; Lin, W.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Q.; He, B.; Luo, C.; Lu, X.; Pei, Z.; Su, H.; Yao, X. Alterations in AQP4 Expression and Polarization in the Course of Motor Neuron Degeneration in SOD1G93A Mice. Mol Med Rep 2017, 16, 1739–1746, doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.6786.

- Feng, S.; Wu, C.; Zou, P.; Deng, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Li, F.; Liu, T.C.-Y.; Duan, R.; et al. High-Intensity Interval Training Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease-like Pathology by Regulating Astrocyte Phenotype-Associated AQP4 Polarization. Theranostics 2023, 13, 3434–3450, doi:10.7150/thno.81951.

- Li, G.; Cao, Y.; Tang, X.; Huang, J.; Cai, L.; Zhou, L. The Meningeal Lymphatic Vessels and the Glymphatic System: Potential Therapeutic Targets in Neurological Disorders. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2022, 42, 1364–1382, doi:10.1177/0271678X221098145.

- Zhang, Q.; Niu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, C.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Feng, H. Meningeal Lymphatic Drainage: Novel Insights into Central Nervous System Disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2025, 10, 142, doi:10.1038/s41392-025-02177-z.

- Boisserand, L.S.B.; Geraldo, L.H.; Bouchart, J.; El Kamouh, M.-R.; Lee, S.; Sanganahalli, B.G.; Spajer, M.; Zhang, S.; Lee, S.; Parent, M.; et al. VEGF-C Prophylaxis Favors Lymphatic Drainage and Modulates Neuroinflammation in a Stroke Model. J Exp Med 2024, 221, e20221983, doi:10.1084/jem.20221983.

- Liu, Q.; Wu, C.; Ding, Q.; Liu, X.-Y.; Zhang, N.; Shen, J.-H.; Ou, Z.-T.; Lin, T.; Zhu, H.-X.; Lan, Y.; et al. Age-Related Changes in Meningeal Lymphatic Function Are Closely Associated with Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-C Expression. Brain Res 2024, 1833, 148868, doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2024.148868.

- Lull, M.E.; Block, M.L. Microglial Activation and Chronic Neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 354–365, doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.014.

- Guo, S.; Wang, H.; Yin, Y. Microglia Polarization From M1 to M2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 815347, doi:10.3389/fnagi.2022.815347.

- Asl, E.R.; Hosseini, S.E.; Tahmasebi, F.; Bolandi, N.; Barati, S. MiR-124 and MiR-155 as Therapeutic Targets in Microglia-Mediated Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2025, 45, 63, doi:10.1007/s10571-025-01578-6.

- Song, G.J.; Suk, K. Pharmacological Modulation of Functional Phenotypes of Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2017, 9, 139, doi:10.3389/fnagi.2017.00139.

- Gomez-Arboledas, A.; Acharya, M.M.; Tenner, A.J. The Role of Complement in Synaptic Pruning and Neurodegeneration. Immunotargets Ther 2021, 10, 373–386, doi:10.2147/ITT.S305420.

- Györffy, B.A.; Kun, J.; Török, G.; Bulyáki, É.; Borhegyi, Z.; Gulyássy, P.; Kis, V.; Szocsics, P.; Micsonai, A.; Matkó, J.; et al. Local Apoptotic-like Mechanisms Underlie Complement-Mediated Synaptic Pruning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 6303–6308, doi:10.1073/pnas.1722613115.

- Liu, H.; Jiang, M.; Chen, Z.; Li, C.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M. The Role of the Complement System in Synaptic Pruning after Stroke. Aging Dis 2024, 16, 1452–1470, doi:10.14336/AD.2024.0373.

- Cho, K. Emerging Roles of Complement Protein C1q in Neurodegeneration. Aging Dis 2019, 10, 652–663, doi:10.14336/AD.2019.0118.

- Qin, Q.; Wang, M.; Yin, Y.; Tang, Y. The Specific Mechanism of TREM2 Regulation of Synaptic Clearance in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 845897, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.845897.

- Zhao, J.; He, Z.; Wang, J. MicroRNA-124: A Key Player in Microglia-Mediated Inflammation in Neurological Diseases. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 771898, doi:10.3389/fncel.2021.771898.

- Gaudet, A.D.; Fonken, L.K.; Watkins, L.R.; Nelson, R.J.; Popovich, P.G. MicroRNAs: Roles in Regulating Neuroinflammation. Neuroscientist 2018, 24, 221–245, doi:10.1177/1073858417721150.

- Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Gui, H.; Xu, D.-P.; Yang, Y.-L.; Su, D.-F.; Liu, X. MicroRNA-124 Mediates the Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Action through Inhibiting the Production of pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. Cell Res 2013, 23, 1270–1283, doi:10.1038/cr.2013.116.

- Nagy, E.E.; Frigy, A.; Szász, J.A.; Horváth, E. Neuroinflammation and Microglia/Macrophage Phenotype Modulate the Molecular Background of Post-Stroke Depression: A Literature Review. Exp Ther Med 2020, 20, 2510–2523, doi:10.3892/etm.2020.8933.

- Long, Y.; Li, X.-Q.; Deng, J.; Ye, Q.-B.; Li, D.; Ma, Y.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Hu, Y.; He, X.-F.; Wen, J.; et al. Modulating the Polarization Phenotype of Microglia - A Valuable Strategy for Central Nervous System Diseases. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 93, 102160, doi:10.1016/j.arr.2023.102160.

- Dan, Y.R.; Chiam, K.-H. Discovery of Plasma Biomarkers Related to Blood-Brain Barrier Dysregulation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Bioinform 2024, 4, 1463001, doi:10.3389/fbinf.2024.1463001.

- Zhang, Y.; Mu, B.-R.; Ran, Z.; Zhu, T.; Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.-M.; Ma, Q.-H.; Lu, M.-H. Pericytes in Alzheimer’s Disease: Key Players and Therapeutic Targets. Exp Neurol 2024, 379, 114825, doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2024.114825.

- İş, Ö.; Wang, X.; Reddy, J.S.; Min, Y.; Yilmaz, E.; Bhattarai, P.; Patel, T.; Bergman, J.; Quicksall, Z.; Heckman, M.G.; et al. Gliovascular Transcriptional Perturbations in Alzheimer’s Disease Reveal Molecular Mechanisms of Blood Brain Barrier Dysfunction. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4758, doi:10.1038/s41467-024-48926-6.

- Niotis, K.; Janney, C.; Helfman, S.; Hristov, H.; Clute-Reinig, N.; Angerbauer, D.; Saperia, C.; Murray, S.; Westine, J.; Seifan, A.; et al. A Blood Biomarker-Guided Precision Medicine Approach for Individualized Neurodegenerative Disease Risk Reduction and Treatment: The Future of Preventive Neurology? (P7-3.016). Neurology 2025, 104, 201, doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000208443.

- Ashton, N.J.; Benedet, A.L.; Di Molfetta, G.; Pola, I.; Anastasi, F.; Fernández-Lebrero, A.; Puig-Pijoan, A.; Keshavan, A.; Schott, J.; Tan, K.; et al. Biomarker Discovery in Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases Using Nucleic Acid-Linked Immuno-Sandwich Assay. medRxiv 2024, 2024.07.29.24311079, doi:10.1101/2024.07.29.24311079.

- Armulik, A.; Genové, G.; Mäe, M.; Nisancioglu, M.H.; Wallgard, E.; Niaudet, C.; He, L.; Norlin, J.; Lindblom, P.; Strittmatter, K.; et al. Pericytes Regulate the Blood-Brain Barrier. Nature 2010, 468, 557–561, doi:10.1038/nature09522.

- Kitchen, P.; Day, R.E.; Taylor, L.H.J.; Salman, M.M.; Bill, R.M.; Conner, M.T.; Conner, A.C. Identification and Molecular Mechanisms of the Rapid Tonicity-Induced Relocalization of the Aquaporin 4 Channel. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 16873–16881, doi:10.1074/jbc.M115.646034.

- Wang, M.; Ding, F.; Deng, S.; Guo, X.; Wang, W.; Iliff, J.J.; Nedergaard, M. Focal Solute Trapping and Global Glymphatic Pathway Impairment in a Murine Model of Multiple Microinfarcts. J Neurosci 2017, 37, 2870–2877, doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2112-16.2017.

- Ding, X.-B.; Wang, X.-X.; Xia, D.-H.; Liu, H.; Tian, H.-Y.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y.-K.; Qin, C.; Wang, J.-Q.; Xiang, Z.; et al. Impaired Meningeal Lymphatic Drainage in Patients with Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease. Nat Med 2021, 27, 411–418, doi:10.1038/s41591-020-01198-1.

- Fonseca, M.I.; Chu, S.-H.; Hernandez, M.X.; Fang, M.J.; Modarresi, L.; Selvan, P.; MacGregor, G.R.; Tenner, A.J. Cell-Specific Deletion of C1qa Identifies Microglia as the Dominant Source of C1q in Mouse Brain. J Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 48, doi:10.1186/s12974-017-0814-9.

- Lansita, J.A.; Mease, K.M.; Qiu, H.; Yednock, T.; Sankaranarayanan, S.; Kramer, S. Nonclinical Development of ANX005: A Humanized Anti-C1q Antibody for Treatment of Autoimmune and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Toxicol 2017, 36, 449–462, doi:10.1177/1091581817740873.

- Wyss-Coray, T.; Yan, F.; Lin, A.H.-T.; Lambris, J.D.; Alexander, J.J.; Quigg, R.J.; Masliah, E. Prominent Neurodegeneration and Increased Plaque Formation in Complement-Inhibited Alzheimer’s Mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 10837–10842, doi:10.1073/pnas.162350199.

- Litvinchuk, A.; Wan, Y.-W.; Swartzlander, D.B.; Chen, F.; Cole, A.; Propson, N.E.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, H. Complement C3aR Inactivation Attenuates Tau Pathology and Reverses an Immune Network Deregulated in Tauopathy Models and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2018, 100, 1337-1353.e5, doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.031.

- Fonseca, M.I.; Ager, R.R.; Chu, S.-H.; Yazan, O.; Sanderson, S.D.; LaFerla, F.M.; Taylor, S.M.; Woodruff, T.M.; Tenner, A.J. Treatment with a C5aR Antagonist Decreases Pathology and Enhances Behavioral Performance in Murine Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Immunol 2009, 183, 1375–1383, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901005.

- Hernandez, M.X.; Jiang, S.; Cole, T.A.; Chu, S.-H.; Fonseca, M.I.; Fang, M.J.; Hohsfield, L.A.; Torres, M.D.; Green, K.N.; Wetsel, R.A.; et al. Prevention of C5aR1 Signaling Delays Microglial Inflammatory Polarization, Favors Clearance Pathways and Suppresses Cognitive Loss. Mol Neurodegener 2017, 12, 66, doi:10.1186/s13024-017-0210-z.

- Propson, N.E.; Roy, E.R.; Litvinchuk, A.; Köhl, J.; Zheng, H. Endothelial C3a Receptor Mediates Vascular Inflammation and Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability during Aging. J Clin Invest 2021, 131, 140966, doi:10.1172/JCI140966.

- Lopez-Ramirez, M.A.; Wu, D.; Pryce, G.; Simpson, J.E.; Reijerkerk, A.; King-Robson, J.; Kay, O.; de Vries, H.E.; Hirst, M.C.; Sharrack, B.; et al. MicroRNA-155 Negatively Affects Blood-Brain Barrier Function during Neuroinflammation. FASEB J 2014, 28, 2551–2565, doi:10.1096/fj.13-248880.

- Hsu, M.; Rayasam, A.; Kijak, J.A.; Choi, Y.H.; Harding, J.S.; Marcus, S.A.; Karpus, W.J.; Sandor, M.; Fabry, Z. Neuroinflammation-Induced Lymphangiogenesis near the Cribriform Plate Contributes to Drainage of CNS-Derived Antigens and Immune Cells. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 229, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08163-0.

- Wang, Y.; Cella, M.; Mallinson, K.; Ulrich, J.D.; Young, K.L.; Robinette, M.L.; Gilfillan, S.; Krishnan, G.M.; Sudhakar, S.; Zinselmeyer, B.H.; et al. TREM2 Lipid Sensing Sustains the Microglial Response in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Cell 2015, 160, 1061–1071, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.049.

- Bemiller, S.M.; McCray, T.J.; Allan, K.; Formica, S.V.; Xu, G.; Wilson, G.; Kokiko-Cochran, O.N.; Crish, S.D.; Lasagna-Reeves, C.A.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. TREM2 Deficiency Exacerbates Tau Pathology through Dysregulated Kinase Signaling in a Mouse Model of Tauopathy. Mol Neurodegener 2017, 12, 74, doi:10.1186/s13024-017-0216-6.

- Filipello, F.; Morini, R.; Corradini, I.; Zerbi, V.; Canzi, A.; Michalski, B.; Erreni, M.; Markicevic, M.; Starvaggi-Cucuzza, C.; Otero, K.; et al. The Microglial Innate Immune Receptor TREM2 Is Required for Synapse Elimination and Normal Brain Connectivity. Immunity 2018, 48, 979-991.e8, doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.016.

- Walker, D.G.; McGeer, P.L. Complement Gene Expression in Human Brain: Comparison between Normal and Alzheimer Disease Cases. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1992, 14, 109–116, doi:10.1016/0169-328x(92)90017-6.

- Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, S. Therapeutic Approaches to CNS Diseases via the Meningeal Lymphatic and Glymphatic System: Prospects and Challenges. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1467085, doi:10.3389/fcell.2024.1467085.

- Negro-Demontel, L.; Maleki, A.F.; Reich, D.S.; Kemper, C. The Complement System in Neurodegenerative and Inflammatory Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Front Neurol 2024, 15, 1396520, doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1396520.

- Shaheen, N.; Shaheen, A.; Osama, M.; Nashwan, A.J.; Bharmauria, V.; Flouty, O. MicroRNAs Regulation in Parkinson’s Disease, and Their Potential Role as Diagnostic and Therapeutic Targets. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2024, 10, 186, doi:10.1038/s41531-024-00791-2.

- He, Z.; Sun, J. The Role of the Neurovascular Unit in Vascular Cognitive Impairment: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Neurobiol Dis 2025, 204, 106772, doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2024.106772.

- Thalgott, J.H.; Zucker, N.; Deffieux, T.; Koopman, M.S.; Dizeux, A.; Avramut, C.M.; Koning, R.I.; Mager, H.-J.; Rabelink, T.J.; Tanter, M.; et al. Non-Invasive Characterization of Pericyte Dysfunction in Mouse Brain Using Functional Ultrasound Localization Microscopy. Nat Biomed Eng 2025. Erratum in. Nat Biomed Eng. 2025. doi:10.1038/s41551-025-01465-x.

- Qi, L.; Wang, F.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, K.; Li, J. Recent Advances in Tissue Repair of the Blood-Brain Barrier after Stroke. J Tissue Eng 2024, 15, 20417314241226551, doi:10.1177/20417314241226551.

- Zhao, K.; Li, Z.; Sun, T.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Barreto, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, R. Editorial: Novel Therapeutic Target and Drug Discovery for Neurological Diseases, Volume II. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1566950, doi:10.3389/fphar.2025.1566950.

- Loh, J.S.; Mak, W.Q.; Tan, L.K.S.; Ng, C.X.; Chan, H.H.; Yeow, S.H.; Foo, J.B.; Ong, Y.S.; How, C.W.; Khaw, K.Y. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Its Therapeutic Applications in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 37, doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01743-1.

- Carloni, S.; Rescigno, M. The Gut-Brain Vascular Axis in Neuroinflammation. Semin Immunol 2023, 69, 101802, doi:10.1016/j.smim.2023.101802.

- Wasan, K.M.; Iqtadar, S.; Mudogo, C.N.; Chávez-Fumagalli, M.A. Editorial: Novel Pharmacological Targets and Strategies to Treat Neglected Global Diseases (NGDs): An LMIC Perspective. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2025, Volume 15-2024. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1527705.

- Imam, F.; Saloner, R.; Vogel, J.W.; Krish, V.; Abdel-Azim, G.; Ali, M.; An, L.; Anastasi, F.; Bennett, D.; Pichet Binette, A.; et al. The Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium: Biomarker and Drug Target Discovery for Common Neurodegenerative Diseases and Aging. Nat Med 2025, 31, 2556–2566, doi:10.1038/s41591-025-03834-0.

- Antoniou, M.; Jorgensen, A.L.; Kolamunnage-Dona, R. Biomarker-Guided Adaptive Trial Designs in Phase II and Phase III: A Methodological Review. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0149803, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0149803.

- Wang, S.; Xie, S.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, G. Biofluid Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2024, 16, 1380237, doi:10.3389/fnagi.2024.1380237.

- Keikha, R.; Hashemi-Shahri, S.M.; Jebali, A. The miRNA Neuroinflammatory Biomarkers in COVID-19 Patients with Different Severity of Illness. Neurologia 2023, 38, e41–e51, doi:10.1016/j.nrl.2021.06.005.

- De Kort, A.M.; Kuiperij, H.B.; Kersten, I.; Versleijen, A.A.M.; Schreuder, F.H.B.M.; Van Nostrand, W.E.; Greenberg, S.M.; Klijn, C.J.M.; Claassen, J.A.H.R.; Verbeek, M.M. Normal Cerebrospinal Fluid Concentrations of PDGFRβ in Patients with Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement 2022, 18, 1788–1796, doi:10.1002/alz.12506.

- Cicognola, C.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; van Westen, D.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Palmqvist, S.; Ahmadi, K.; Strandberg, O.; Stomrud, E.; Janelidze, S.; et al. Associations of CSF PDGFRβ With Aging, Blood-Brain Barrier Damage, Neuroinflammation, and Alzheimer Disease Pathologic Changes. Neurology 2023, 101, e30–e39, doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000207358.

| Therapeutic Target | Mechanism of Action | Preclinical Evidence | Proposed Therapeutic Approach | Potential Benefits | Challenges/Considerations | Key References |

| PDGF-BB/PDGFRβ Signaling | Maintains pericyte survival and BBB integrity via ERK and PI3K pathways | PDGFRβ+/- mice show accelerated BBB breakdown and neurodegeneration; restoration protects against vascular damage | PDGF-BB supplementation; prevention of PDGFRβ shedding; APOE4-targeted interventions | Preserves pericyte coverage; maintains BBB integrity; prevents early vascular damage | Timing critical; systemic effects; optimal dosing unclear | [35,78] |

| VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 Signaling | Enhances meningeal lymphatic vessel function and promotes lymphangiogenesis for brain waste clearance | VEGF-C administration in AD mice increases mLV diameter, reduces CSF and brain Aβ, restores cognition | Recombinant VEGF-C (intrathecal or systemic); VEGFR-3 agonists; transcranial radiofrequency stimulation | Enhances protein clearance; reduces tau and Aβ accumulation; improves cognitive function | Delivery route optimization; potential angiogenic effects; dose-finding needed | [30,31] |

| AQP4 Polarization Restoration | Restores proper localization of AQP4 at perivascular astrocytic endfeet to enhance glymphatic flow | Exercise and calmodulin inhibition restore AQP4 polarization and improve Aβ clearance in AD models | High-intensity interval training; aerobic exercise; calmodulin inhibitors (trifluoperazine); pharmacological AQP4 modulators | Enhances glymphatic clearance; reduces protein accumulation; improves waste removal | Exercise compliance; pharmacological specificity; avoiding edema | [79,80,81] |

| Complement C1q Inhibition | Blocks initiation of classical complement cascade; prevents C1q tagging of synapses for elimination | C1q deletion or neutralizing antibodies protect synapses and improve cognition in AD mouse models | Anti-C1q monoclonal antibodies; C1q inhibitor peptides; selective C1q blockers | Prevents excessive synaptic pruning; preserves cognitive function; reduces neuroinflammation | Balancing physiological vs pathological complement; immune surveillance concerns | [19,82,83] |

| Complement C3 Modulation | Prevents C3 cleavage and iC3b-mediated synaptic tagging; blocks complement amplification | C3 deficiency prevents age-related synapse loss and improves LTP in aged mice; protects against AD pathology | C3 inhibitors (compstatin analogs); C3 convertase inhibitors | Reduces synaptic loss; improves cognitive outcomes; maintains neuronal networks | Timing of intervention; systemic complement functions; infection risk | [18,84,85] |

| CR3 (CD11b/CD18) Blockade | Prevents microglial engulfment of iC3b-tagged synapses | CR3 knockout mice protected from Aβ-induced synapse loss; reduced microglial phagocytosis | CR3 antagonists; CD11b-blocking antibodies; small molecule inhibitors | Preserves synapses; reduces microglial-mediated damage; maintains circuit function | Microglial function preservation; specificity for pathological pruning | [19,20] |

| C5aR1 (C5a Receptor) Antagonism | Blocks C5a-mediated microglial activation; reduces excessive synaptic pruning | C5aR1 deletion or PMX205 treatment reduces synapse loss and improves cognition in multiple AD models | PMX205 or PMX53 (C5aR1 antagonists); small molecule C5aR1 inhibitors | Reduces synaptic loss; improves behavior; modulates neuroinflammation without blocking upstream complement | Better therapeutic window than C1q/C3 inhibition; preserves beneficial complement functions | [86,87,88] |

| miR-124 Replacement Therapy | Restores anti-inflammatory signaling; promotes M2 microglial polarization; inhibits inflammatory mediators | miR-124 overexpression reduces neuroinflammation and promotes neuroprotection in injury models | Lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated miR-124; viral vector delivery; synthetic miR-124 mimics | Shifts microglia to anti-inflammatory phenotype; reduces TNF-α; increases IL-10 | Delivery to CNS; off-target effects; stability of miRNA therapeutics | [27] |

| miR-155 Inhibition | Reduces pro-inflammatory signaling; decreases NF-κB activation; attenuates M1 microglial responses | miR-155 deletion improves outcomes in spinal cord injury and reduces neuroinflammation in MS models | AntagomiR-155; locked nucleic acid (LNA) anti-miR-155; GapmeR inhibitors | Reduces neuroinflammation; improves functional recovery; modulates TLR signaling | Delivery challenges; dosing optimization; potential immune effects | [29,89] |

| Meningeal Lymphatic Enhancement | Physical or pharmacological enhancement of mLV structure and function | Exercise enhances mLV flow; VEGF-C expands mLV diameter and improves clearance in aged mice | Aerobic exercise protocols; VEGF-C administration; minimally invasive mLV stimulation | Enhances brain-to-cervical lymph node drainage; improves clearance of proteins and immune cells | Age-related mLV degeneration; non-invasive enhancement methods needed | [30,90] |

| TREM2 Modulation | Regulates microglial phagocytic capacity and metabolic state; modulates complement-mediated pruning | TREM2 deficiency alters microglial response to plaques; affects synaptic engulfment | TREM2 agonistic antibodies; TREM2 activity enhancers (context-dependent) | Modulates microglial function; may enhance beneficial phagocytosis while reducing excessive pruning | Complex role (protective vs detrimental); stage-dependent effects | [91,92,93] |

| CD200-CD200R Axis Enhancement | Maintains microglial quiescence; promotes M2 polarization; reduces inflammatory activation | CD200-Fc treatment shifts macrophages/microglia from M1 to M2; reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines | CD200-Fc fusion protein; CD200R agonists | Reduces neuroinflammation; promotes neuroprotective microglial phenotype; decreases oxidative stress | Systemic delivery; CNS penetration; long-term safety | [94] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).