1. Introduction

Vehicular Ad-hoc Networks (VANETs), a specialized subclass of Mobile Ad-hoc Networks (MANETs), constitute the fundamental communication infrastructure for contemporary Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) [

1]. These networks are integral to a diverse array of applications, encompassing safety-critical functions such as collision avoidance and emergency alert dissemination, as well as efficiency-oriented services like dynamic traffic flow optimization [

2]. As autonomous driving technologies advance, the demand for reliable, low-latency Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) communication becomes increasingly paramount. Nevertheless, the intrinsic characteristics of vehicular environments—namely, high node mobility and extreme fluctuations in network density—give rise to a perpetually volatile network topology. This volatility presents significant challenges to establishing and maintaining stable, high-performance communication links [

3].

Addressing these challenges is complicated by the inherent performance dichotomy between conventional routing paradigms. On one hand,

reactive protocols (e.g., AODV) initiate route discovery only on demand, which minimizes overhead in sparse networks but introduces high latency during the discovery phase [

4]. On the other hand,

proactive protocols (e.g., OLSR) maintain continuous topological tables, ensuring immediate route availability but incurring prohibitive bandwidth overhead in highly dynamic environments [

5]. This fundamental trade-off has led to diverging hypotheses in the research community regarding the optimal strategy for ITS, with neither approach providing a “one-size-fits-all” solution. Recent comparative evaluations in urban scenarios confirm that hybrid approaches are essential for maintaining quality of service as node density varies [32]. In response, hybrid routing architectures have been proposed to synergistically combine the strengths of both paradigms, adaptively transitioning between reactive and proactive modes [

6].

However, optimizing the routing layer alone is often insufficient. Concurrently, adaptive transmission power control has been recognized as an indispensable mechanism for mitigating signal interference (“broadcast storms”) and enhancing energy efficiency [

7]. Despite this, a substantial gap remains in the literature: most existing studies treat routing logic and physical-layer power control as isolated optimization problems. Few frameworks successfully integrate dynamic routing decisions with simultaneous power modulation to address the complex interference patterns found in dense urban traffic.

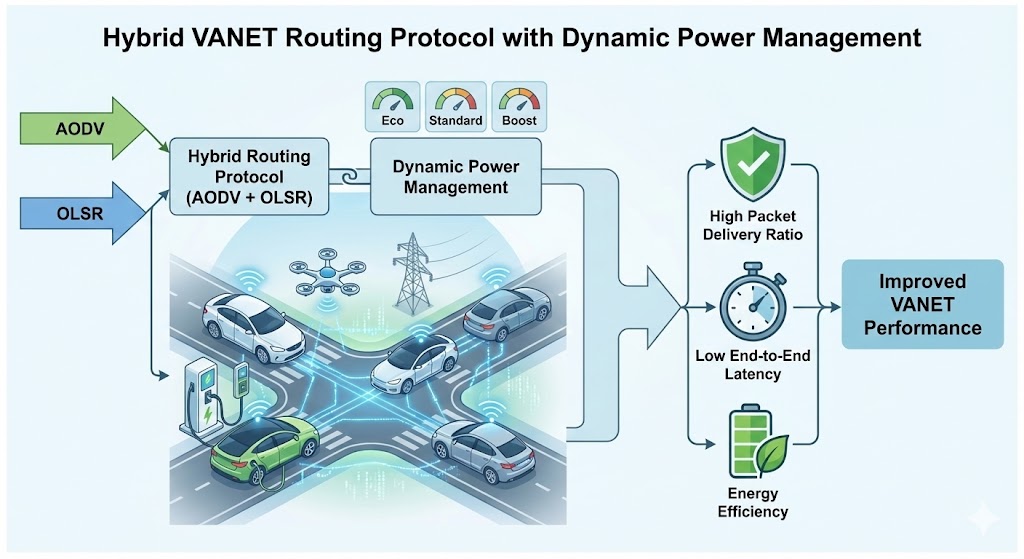

This research presents a novel, context-aware hybrid routing framework—the

Dynamic Hybrid Routing Protocol (DHRP)—that tightly couples routing decisions with physical-layer adaptations. The main aim of this work is to address the scalability and latency limitations of traditional protocols by implementing a sophisticated decision logic that evaluates real-time network metrics, including vehicular speed, density, and destination distance [

8]. Unlike static hybrid approaches, DHRP dynamically selects the most efficient routing strategy (AODV or OLSR) while concurrently modulating transmission power between Eco, Standard, and Boost modes.

The principal conclusions of this study, substantiated through extensive simulations using NS-3 and SUMO, demonstrate that DHRP resolves the routing performance dichotomy. The empirical evidence highlights the pronounced superiority of the proposed system over traditional baselines and contemporary benchmarks (such as ENDRE-VANET). Specifically, DHRP maintains a Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR) exceeding 90%, ensures end-to-end delays remain under the safety-critical 40 ms threshold, and achieves energy savings of up to 60%. This paper details the protocol design, the cross-layer control mechanism, and the validation of these performance enhancements.

2. Related Work

A substantial body of research has characterized the foundational paradigms of VANET routing, revealing a fundamental performance dichotomy. Reactive protocols, exemplified by Ad-hoc On-Demand Distance Vector (AODV), have demonstrated efficacy in sparse vehicular networks due to their minimal control overhead [

3,

4]. In contrast, proactive protocols such as Optimized Link State Routing (OLSR) ensure immediate route availability and low latency by maintaining continuous topological information [

5,

6]. Nevertheless, the literature elucidates the inherent trade-offs: the prohibitive route discovery latency associated with AODV in highly mobile contexts, and the excessive control overhead incurred by OLSR in dynamic topologies.

2.1. Hybrid Routing Developments (2022–2024)

To reconcile this dichotomy, recent studies have advanced hybrid frameworks. Al-Jubori and Al-Raweshidy [27] proposed a bio-inspired hybrid protocol that optimizes cluster stability in high-mobility scenarios. However, their approach introduces significant computational complexity and lacks a direct mechanism for interference management. Similarly, Menouar and Massi [30] introduced a hybrid congestion control mechanism for V2X communications. While effective at MAC-layer load balancing, their system remains reactive to congestion rather than predictive.

The ENDRE-VANET protocol [

4] represented a step forward by using density and energy as switching criteria. Nevertheless, it relies on static thresholds that cannot adapt to sudden topology changes. More recently, Khan

et al. [31] surveyed the integration of VANETs with 5G and proposed network slicing for service differentiation. However, their framework focuses on infrastructure-to-vehicle (V2I) links and does not address the ad-hoc (V2V) routing stability required when infrastructure is unavailable.

2.2. Power Control and Cross-Layer Limitations

Concurrently, adaptive transmission power control has emerged as a key area of optimization. Zhang et al. [28] utilized Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) to adjust transmission power to minimize interference dynamically. While promising, this approach treats power control as an isolated physical-layer optimization problem, decoupled from routing-layer decisions. This isolation means the routing protocol may select a path that the physical layer cannot sustain at lower power levels.

2.3. Methodological Gaps

Finally, methodological limitations persist in validation standards. Singh and Agrawal [29] conducted a comparative analysis of AODV and OLSR using realistic SUMO traffic. However, their study focused exclusively on packet delivery and latency, omitting energy consumption metrics. This oversight is critical, as high-performance routing is unsustainable if it depletes vehicle communication units (OBUs).

2.4. The Research Gap and Proposed Solution

To contextualize the contributions of the proposed framework, we performed a qualitative comparison against prominent hybrid routing protocols recently published in the literature.

Table 1 juxtaposes the operational mechanics of the proposed DHRP against state-of-the-art benchmarks, specifically highlighting differences in switching criteria and physical-layer integration.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Proposed Hybrid System

This research introduces the Dynamic Hybrid Routing Protocol (DHRP), a novel context-aware architectural framework designed to reconcile the conflicting requirements of scalability, latency, and energy efficiency in VANETs.1 Unlike conventional hybrid protocols that toggle between routing modes based on a single metric, DHRP establishes a Cross-Layer Synergistic Control Plane. This control plane simultaneously orchestrates the Network Layer (routing protocol selection) and the Physical Layer (transmission power modulation) based on a hierarchical evaluation of vehicular speed, nodal density, and destination distance.

3.2. Multi-Criterion Switching Logic

The central control logic of the DHRP dynamically selects the optimal routing paradigm by evaluating a prioritized hierarchy of real-time network parameters. The principal determinant is vehicular speed. When a vehicle’s velocity exceeds a predefined threshold of 80 km/h, the protocol pre-emptively transitions to the proactive OLSR mode.4 This proactive posture is imperative to mitigate the excessive latencies associated with AODV’s on-demand discovery mechanism in high-mobility environments characterized by frequent topological changes.

For vehicles operating at lower speeds, the switching logic is governed by a hysteresis control mechanism based on local nodal density . Specifically:

The protocol transitions to OLSR when the local neighbor count exceeds an upper bound of 80 nodes to manage dense topologies efficiently.

In contrast, it reverts to the resource-parsimonious AODV paradigm when density diminishes below 60 nodes to conserve network bandwidth.

Additionally, for route requests targeting a destination beyond 400 meters (d > 400). At the same time, in AODV mode, the system initiates a transient, geographically constrained OLSR-like broadcast accompanied by a transmission power boost to ensure connectivity.

3.3. Synergistic Power Management Framework

Operating in concert with the multi-criteria routing logic is a three-tiered adaptive power control framework designed to optimize transmission efficiency based on environmental context.11 The system modulates the transmission power as follows:

- 1)

Standard Mode (25 dBm): The system defaults to this mode when operating in reactive AODV mode within sparse to moderate densities, establishing an effective equilibrium between communication range and energy consumption.

- 2)

Eco Mode (18 dBm): In high-density environments where the neighbor count exceeds 80 nodes, the protocol transitions to Eco Mode.13 This reduction is crucial for mitigating signal interference and alleviating the “Broadcast Storm” problem inherent in proactive OLSR routing.

- 3)

Boost Mode (28 dBm): This mode is reserved for exigent circumstances, such as highly sparse AODV environments or long-distance route-discovery requests exceeding 400 meters, to ensure connectivity over extended ranges.

Figure 1 illustrates the decision-making workflow of the proposed hybrid VANET routing controller that adaptively selects the routing mode based on instantaneous mobility conditions. The process begins with node initialization, where AODV is set as the default protocol and the transmission power is configured to 25 dBm. The controller then enters a continuous environmental assessment loop, during which each vehicle periodically collects key context metrics, namely speed and node density.

A mobility-based decision is subsequently performed by comparing the current speed to a predefined threshold (80 km/h). If the vehicle speed exceeds this threshold, the node is classified as being in a high-mobility state, and the controller directs the system to proceed to the proactive-routing stage (Block 5). This choice reflects the need for faster route availability and reduced route-discovery latency in rapidly changing topologies. Conversely, if the speed is below or equal to the threshold, mobility is treated as non-dominant and the controller forwards the decision to a density evaluation stage (Block 6), where routing and power-control actions are determined according to network congestion/sparsity conditions.

Finally, the figure includes a preemptive OLSR switching action that returns control to the assessment loop, ensuring the routing protocol selection is continuously updated as traffic dynamics change. Overall, the figure formalizes a lightweight context-aware mechanism that prioritizes mobility-driven adaptation and integrates with subsequent density-based control to improve stability and communication efficiency in heterogeneous VANET scenarios.

4. Performance Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed protocol, the following standard performance metrics were employed:

4.1. Network Management Cost (Normalized Routing Load)

To evaluate the bandwidth economy of the proposed system, we analyze the Normalized Routing Load (NRL). This index quantifies the operational “cost” of maintaining connectivity by comparing the volume of non-payload traffic against actual data throughput. Specifically, it represents the ratio of all protocol-specific control messages—such as topology updates, route requests (RREQ), and replies (RREP)—to the aggregate number of data packets successfully received at the destination. A minimized NRL value demonstrates that the routing logic is efficient, preserving the majority of channel capacity for user applications rather than administrative overhead.

4.2. Transmission Success Rate (Packet Delivery Ratio)

The Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR) functions as the core reliability index for the vehicular network. This metric measures the integrity of the communication link by calculating the proportion of generated data packets that successfully traverse the network and reach their intended destination. For safety-critical ITS services, achieving a high PDR is paramount to ensuring that vital collision warnings and status updates are not lost due to channel interference or mobility-induced link breaks. The metric is computed as follows:

where

is the total number of packets received and

is the total number of packets sent.

4.3. Average End-to-End Delay (E2ED)

This metric assesses the time-domain characteristics of the network, which is paramount for safety-critical ITS applications requiring the immediate dissemination of warning messages. Mathematically, E2ED is defined as the average time interval between the time a data packet originates at the source application layer and its successful arrival at the destination application layer. The measurement encapsulates all intermediate latency components, including route acquisition delays, interface queuing, medium access contention, and physical propagation time.

4.4. Network Throughput: Network

Throughput quantifies the adequate capacity and reliability of the communication channel. It is computed as the cumulative sum of payload bits successfully received by the destination nodes divided by the total simulation duration. A superior throughput metric reflects the protocol’s ability to sustain high-volume data exchange while effectively mitigating packet loss and channel saturation.

4.5. Energy Efficiency (EE)

To assess the operational sustainability of the routing framework, Energy Efficiency (EE) is employed as a key performance indicator. This metric represents the trade-off between communication performance and power expenditure, calculated as the ratio of the total bits successfully delivered to the network’s aggregate energy consumption (in Joules). Higher energy efficiency signifies that the protocol effectively minimizes control overhead and optimizes transmission power, thereby preserving the battery life of vehicular On-Board Units (OBUs).

4.6. Simulation Environment

To ensure the reproducibility of the proposed DHRP framework and to validate its performance under realistic vehicular conditions, we utilized the Network Simulator 3 (NS-3, version 3.36.1). This simulator was coupled with SUMO (Simulation of Urban Mobility) to generate high-fidelity vehicle traces derived from real-world road maps, thereby avoiding the inaccuracies often associated with synthetic random waypoint models. The simulation was configured to test scalability by varying the vehicular density from 50 to 500 nodes within a 400-second operational window.

Table 2 outlines the specific configuration parameters employed throughout the experimental campaign.

5. Results

This section presents the experimental findings obtained from the comprehensive simulation campaign. The performance of the proposed Dynamic Hybrid Routing Protocol (DHRP) was benchmarked against a traditional Hybrid protocol and the state-of-the-art ENDRE-VANET protocol. The evaluation focused on validating the protocol’s adaptability and quantifying its performance in terms of reliability, latency, and energy efficiency.

5.1. Real-Time Adaptation and Context Awareness

The primary capability of the DHRP is its autonomous adaptation to fluctuating network conditions. Simulation logs provided empirical validation of this cross-layer decision logic.

Protocol Switching Accuracy: As detailed in

Table 3, the protocol correctly identified network context; nodes located in high-density areas (specifically those with >100 neighbors) successfully transitioned to the proactive Optimized Link State Routing (OLSR) mode. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the density-based hysteresis mechanism in selecting the optimal routing strategy.

Dynamic Power Control: Table 4 illustrates the synergistic power adjustment mechanism. The results confirm that nodes with high neighbor counts reduced their transmission power to ‘Eco Mode’ to mitigate interference, whereas nodes in sparse environments increased power to ensure connectivity.

Table 3.

Protocol switching mechanism.

Table 3.

Protocol switching mechanism.

| Node ID |

Density State |

Neighbours (N) |

Active Protocol |

Node 195

Node 92

Node 238

|

HIGH

|

136

|

OLSR

|

|

HIGH

|

136

|

OLSR

|

|

HIGH

|

136

|

OLSR

|

Node 13

Node 99

|

HIGH

|

108

|

OLSR

|

|

HIGH

|

102

|

OLSR

|

Node 150

Node 206

Node 391

Node 417

|

HIGH

|

102

|

OLSR

|

|

HIGH

|

102

|

OLSR

|

|

HIGH

|

102

|

OLSR

|

|

HIGH

|

102

|

OLSR

|

Node 90

Node 196

|

HIGH

|

136

|

OLSR

|

|

MODERATE

|

93

|

No Change (Hysteresis)

|

|

Node 252

|

MODERATE

|

93

|

No Change (Hysteresis)

|

|

Node 215

|

MODERATE

|

93

|

No Change (Hysteresis)

|

|

Node 393

|

MODERATE

|

93

|

No Change (Hysteresis)

|

|

Node 413

|

MODERATE

|

93

|

No Change (Hysteresis)

|

|

Node 435

|

MODERATE

|

93

|

No Change (Hysteresis)

|

|

Node 10

|

HIGH

|

104

|

OLSR

|

|

Node 432

|

HIGH

|

107

|

OLSR

|

|

Node 157

|

HIGH

|

107

|

OLSR

|

|

Node 404

|

HIGH

|

110

|

OLSR

|

|

Node 188

|

HIGH

|

104

|

OLSR

|

|

Node 26

|

HIGH

|

140

|

OLSR

|

|

Node 259

|

HIGH

|

136

|

OLSR

|

|

Node 106

|

HIGH

|

116

|

OLSR

|

|

Node 103

|

HIGH

|

110

|

OLSR

|

Table 4.

Adaptive Power Management.

Table 4.

Adaptive Power Management.

| Node ID |

Number of Neighbours |

Action taken |

| |

|

|

|

482

|

40

|

Increasing Power

|

|

483

|

122

|

Setting Moderate Power

|

|

485

|

106

|

Setting Moderate Power

|

|

486

|

84

|

Setting Moderate Power

|

|

487

|

200

|

Reducing Power

|

|

488

|

123

|

Setting Moderate Power

|

|

489

|

86

|

Setting Moderate Power

|

|

490

|

186

|

Reducing Power

|

|

491

|

90

|

Setting Moderate Power

|

|

492

|

40

|

Increasing Power

|

|

493

|

157

|

Reducing Power

|

|

494

|

42

|

Increasing Power

|

|

495

|

154

|

Reducing Power

|

|

496

|

177

|

Reducing Power

|

|

497

|

97

|

Setting Moderate Power

|

|

498

|

138

|

Reducing Power

|

|

499

|

186

|

Reducing Power

|

“

Table 3 presents a granular validation of the protocol’s switching logic. It confirms that nodes in high-density clusters (e.g., Node 195 with 136 neighbors) correctly transition to the proactive OLSR paradigm to mitigate congestion. Furthermore, nodes in the moderate density band (e.g., Node 196 with 93 neighbors) demonstrate the effectiveness of the dual-threshold hysteresis mechanism, engaging the ‘No Change’ state to prevent deleterious protocol oscillations and ensure network stability.”

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the DHRP’s operational logic follows a hierarchical, continuous control loop that adapts to rapid environmental changes. The process initiates (Step 1) by defaulting to the reactive AODV protocol with standard transmission power (25 dBm), ensuring minimal overhead during system startup.

The core cycle begins with Context Acquisition (Step 2), where the OBU aggregates real-time telemetry: vehicular velocity (v), local neighbor density (N), and destination distance (D). The decision matrix prioritizes Mobility Evaluation (Step 3) as the primary stability constraint. If the vehicle speed exceeds 80 km/h, the system immediately preempts the topology check. It forces a switch to OLSR, ensuring that routing tables are proactively maintained to counter the high probability of link breakage.

If the mobility is within stable limits, the logic proceeds to Topology Evaluation (Step 4), which employs a hysteresis mechanism to manage network density:

High Density (N > 80): The system switches to OLSR to handle the complex mesh but simultaneously activates Eco Mode (18 dBm) in Step 5. This critical cross-layer action reduces the contention domain, mitigating interference in congested clusters.

Low Density (N < 60): The system reverts to AODV to conserve bandwidth. Within this branch, a secondary check evaluates the destination distance. If the target is distant ($> 400$ m), Boost Mode (28 dBm) is triggered to maximize the single-hop reachability range.

Moderate Density (60 < N < 80): To prevent “ping-pong” effects (rapid oscillations between protocols), the system maintains the previous state until a clear threshold violation occurs.

The empirical data in

Table 4 confirms the inverse proportionality logic embedded in the DHRP control plane. The system exhibits three distinct behavioral zones:

Sparse Topology Response (N < 60): As observed in Nodes 482, 492, and 494 (where N approximately 40), the algorithm correctly identifies a risk of network partitioning. Consequently, it triggers a “Boost Mode” state, increasing transmission power to bridge the communication gap with distant vehicles.

Moderate Stability Zone (60 < N < 130): Nodes such as 483 and 486 remain in “Standard Mode.” This indicates the hysteresis mechanism is functioning correctly, preventing unnecessary power fluctuations when the topology is stable.

High-Density Saturation (N > 130): Critically, nodes in highly congested clusters (e.g., Node 487 with 200 neighbors and Node 496 with 177 neighbors) automatically trigger the “Eco Mode.” By reducing transmission power in these instances, the protocol successfully limits the contention domain, thereby preventing the packet collisions and broadcast storms that typically degrade performance in dense VANET scenarios.

Figure 3 depicts the packet delivery ratio (PDR) as a function of the number of vehicles, comparing the proposed DHRP against ENDRE-VANET and a Traditional Hybrid baseline. The results indicate that the proposed DHRP maintains a consistently high PDR (≈90–95%) over the whole density range, demonstrating strong reliability and robustness under both moderate and highly congested traffic conditions. ENDRE-VANET also shows relatively stable performance, but it remains below the proposed scheme across most operating points, gradually improving with increased density and converging toward the proposed method only at the highest vehicle counts.

In contrast, the Traditional Hybrid approach exhibits substantial performance degradation as node density increases. After a brief improvement at low densities, its PDR decreases sharply with increasing vehicle density, approaching near-zero delivery rates in very dense scenarios. This behavior is consistent with the increased likelihood of channel contention, packet collisions, route instability, and control-message overhead at high traffic loads, which disproportionately affects routing strategies that are less adaptive to rapidly changing topology and congestion.

Table 5 reports the packet delivery ratio (PDR, %) as a function of vehicular density (50–500 vehicles) for three schemes: Traditional Hybrid, ENDRE-VANET, and the proposed DHRP. Overall, the proposed DHRP delivers the most reliable packets across the evaluated densities, maintaining a high PDR that remains close to 90% even as the network becomes increasingly congested.

Specifically, DHRP achieves 94.16% PDR at 50 vehicles and gradually decreases to 88.73% at 500 vehicles, indicating good scalability under higher contention and more frequent topology changes. In contrast, ENDRE-VANET starts at a lower value (82.0% at 50 vehicles) and increases steadily with density to 89.0% at 500 vehicles. Across most operating points (50–450 vehicles), DHRP provides a clear improvement over ENDRE-VANET, with an advantage of approximately 7.6–12.2 percentage points, while performance becomes nearly comparable at the highest density (500 vehicles).

The Traditional Hybrid baseline exhibits substantial degradation as density increases, reflecting limited robustness under congested or highly dynamic conditions. Its PDR fluctuates at low densities (e.g., 40% at 50 vehicles and 60% at 100 vehicles) but then declines sharply at higher densities, reaching single-digit values (≈5% at 400 vehicles and 4% at 450 vehicles); at 500 vehicles it is reported as N/A, suggesting failure to sustain valid delivery/measurement under extreme network load. These results imply that the traditional hybrid approach becomes increasingly vulnerable to route instability, control overhead, and channel contention, whereas DHRP maintains stable delivery through its adaptive design.

In summary,

Table 5 confirms that DHRP offers the best reliability and scalability, delivering consistently high PDR across low-to-high density VANET scenarios, and outperforming both ENDRE-VANET and the Traditional Hybrid baseline in most tested conditions.

5.2. Routing Efficiency (Overhead)

As shown in

Figure 4, the proposed DHRP demonstrates an exceptionally low and stable routing overhead across all evaluated densities. Notably, even under the most congested scenario (500 vehicles), the number of control packets remains below 40, indicating strong scalability in high-load VANET conditions. This overhead reduction is primarily attributed to the adaptive use of AODV in sparse or moderately connected environments, which limits unnecessary proactive signalling, and to the proposed Eco Mode, which constrains the dissemination scope of OLSR control messages by restricting broadcast propagation to a bounded neighbourhood. Consequently, DHRP avoids excessive control traffic amplification typically observed in proactive routing under dense topologies, thereby improving routing efficiency while preserving communication reliability.

Table 6 presents the routing overhead (control packet count) as a function of vehicular density for the Traditional Hybrid, ENDRE-VANET, and the proposed DHRP scheme. The results show that DHRP maintains the lowest and most stable overhead profile across all traffic densities, indicating strong scalability and reduced signalling burden in both sparse and congested VANET environments.

At low densities, DHRP introduces only limited control traffic (e.g., ≈10 packets at 50 vehicles, increasing gradually to ≈20 packets at 150 vehicles). As density increases, the overhead growth remains moderate: DHRP stays below ≈30 packets up to 350 vehicles and reaches only ≈38 packets at 500 vehicles. This behaviour suggests that the proposed hybrid switching strategy effectively limits unnecessary proactive broadcasts while preserving route availability.

In comparison, ENDRE-VANET exhibits a monotonic increase in overhead as the number of vehicles rises, growing from ≈20 packets at 50 vehicles to ≈180 packets at 500 vehicles. This indicates a higher control-plane cost under dense conditions, likely due to increased periodic signalling and topology maintenance requirements.

The Traditional Hybrid baseline demonstrates the least favourable behaviour in dense scenarios. Although its overhead is relatively small at low densities (≈10–25 packets up to 150 vehicles), it escalates sharply at higher loads, reaching ≈350 packets at 400–450 vehicles, and becomes N/A at 500 vehicles, implying instability or inability to maintain valid operation/measurement under extreme congestion. Such escalation is consistent with excessive route maintenance, frequent rediscovery, and amplified control messaging under intense contention and rapidly changing connectivity.

Overall,

Table 6 confirms that DHRP achieves superior routing efficiency by substantially reducing control overhead compared with ENDRE-VANET and avoiding the severe overhead explosion observed for the Traditional Hybrid approach in highly dense VANET scenarios.

5.3. Latency and Throughput Analysis

Regarding network throughput, as presented in Figure 6 and

Table 7, the DHRP demonstrates superior channel utilization. The protocol achieves a peak throughput of approximately 0.37 Mbps. Furthermore, it maintains a substantial performance margin over the benchmark protocols at all vehicle densities exceeding 150 nodes. This sustained throughput indicates effective congestion management and reduced packet collisions, enabled by the synergistic power control mechanism.

Figure 5 illustrates the end-to-end delay (E2ED) as a function of the number of vehicles, comparing the proposed DHRP with ENDRE-VANET and a Traditional Hybrid baseline. Overall, the proposed DHRP achieves the lowest delay across all tested densities, remaining in the tens-of-milliseconds range and showing only a modest increase as the network becomes more congested. This indicates that DHRP maintains stable route availability and mitigates route repair latency even under high traffic density.

In contrast, ENDRE-VANET exhibits higher delays that increase steadily with the number of vehicles, reflecting a larger control-plane burden and greater sensitivity to contention and topology dynamics. The Traditional Hybrid method exhibits the worst delay performance, with delays increasing markedly as density rises, consistent with frequent route disruptions, repeated route discoveries, and intensified channel contention in dense VANET scenarios.

These results confirm that DHRP provides superior timeliness and scalability, effectively limiting latency growth under congestion by adaptively selecting the most suitable routing behaviour for the prevailing network conditions.

Figure 6 presents the average throughput (Mbps) versus the number of vehicles, comparing the proposed hybrid system with the baseline hybrid protocol. The proposed approach consistently delivers higher throughput across the evaluated densities. In particular, throughput increases markedly from low-density conditions. It reaches its maximum at moderate network loads (around the mid-range vehicle counts), indicating improved channel utilization and more stable data forwarding when connectivity becomes sufficiently rich. As vehicular density continues to increase, a moderate reduction is observed, expected due to intensified medium contention, increased collision probability, and queuing effects; however, the proposed scheme maintains a clear advantage over the baseline in the high-density regime.

Conversely, the baseline hybrid protocol exhibits lower throughput and a more pronounced degradation as the network becomes congested, reflecting reduced efficiency in maintaining stable routes and higher susceptibility to contention-driven retransmissions and control overhead. Overall, the figure demonstrates that the proposed hybrid system achieves superior spectral efficiency and scalability, sustaining higher throughput under both moderate and dense VANET scenarios.

Table 7 reports the average throughput (Mbps) achieved by the Proposed Hybrid System compared with the baseline Hybrid protocol under increasing vehicular density (50–450 vehicles). Overall, the proposed approach delivers superior throughput in medium-to-high density regimes, demonstrating improved channel utilization and more efficient data forwarding as the network becomes more connected.

At low density, the baseline hybrid protocol achieves higher throughput (e.g., 0.15 Mbps vs. 0.06 Mbps at 50 vehicles, and 0.19 Mbps vs. 0.14 Mbps at 100 vehicles), suggesting that the proposed strategy incurs an initial adaptation overhead or benefits less from sparse connectivity. However, as density increases, the proposed system quickly surpasses the baseline: at 150–200 vehicles, throughput rises to 0.33–0.37 Mbps, whereas the baseline remains at 0.18–0.24 Mbps. This indicates that the proposed mechanism more effectively exploits the richer neighbor set and improved path diversity at moderate densities.

In the higher-density region (≥250 vehicles), the proposed method maintains throughput in the range of 0.26–0.32 Mbps, while the baseline experiences a pronounced decline, dropping to 0.16 Mbps at 300 vehicles and reaching as low as 0.06–0.08 Mbps at 400–450 vehicles. The degradation of the baseline at high density is consistent with increased medium contention, collision probability, and routing/control overhead, which reduce effective payload transmission. By contrast, the proposed hybrid system preserves higher throughput, implying better congestion tolerance and routing stability under heavy network load.

In summary, the table confirms that the proposed system provides higher throughput scalability, particularly in dense VANET scenarios where conventional hybrid routing becomes increasingly inefficient.

5.4. Energy Efficiency

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the proposed scheme maintains consistently high energy efficiency, ranging from 94.5% to 96.6% across the examined vehicular densities. In contrast, ENDRE-VANET exhibits substantially lower efficiency under sparse network conditions, highlighting its reduced ability to conserve energy when connectivity is limited and route maintenance becomes more costly. These findings confirm that the proposed design effectively balances communication performance and energy consumption. Moreover, the observed efficiency gains are consistent with the synergistic power-control strategy summarized in

Table 8, which adaptively regulates transmission power to minimize unnecessary energy expenditure while preserving reliable link formation and packet delivery.

Figure 7 shows the energy efficiency of the proposed DHRP compared with ENDRE-VANET across different densities. DHRP maintains consistently high energy efficiency across the full range of vehicle counts, indicating effective power-aware operation without sacrificing communication performance. By contrast, ENDRE-VANET exhibits substantially lower efficiency at sparse and medium densities, and its efficiency gradually improves with increasing density. The results validate that DHRP’s energy-aware strategy reduces unnecessary energy expenditure and achieves a more favourable trade-off between reliability and resource consumption.

As illustrated in

Table 8, the proposed DHRP demonstrates superior robustness and scalability compared to the ENDRE-VANET protocol. A critical disparity is observed in sparse network scenarios (50–150 vehicles). In these low-density environments, ENDRE-VANET suffers significant performance degradation, achieving an efficiency of only 12% at 50 vehicles. This poor performance is attributed to its reliance on stable clusters, which are difficult to form when vehicles are widely scattered.

In contrast, the proposed DHRP maintains a high efficiency of 94.49% even at the lowest density. This validates the efficacy of the protocol’s adaptive switching logic; in sparse conditions, DHRP correctly identifies the lack of neighbors and switches to AODV with Boost Mode, ensuring connectivity is maintained even without a dense mesh of nodes.

As the network density increases to 500 vehicles, ENDRE-VANET shows a linear improvement, peaking at 87%. However, the proposed protocol remains remarkably stable, consistently delivering >96% efficiency across traffic loads. This “density-invariance” demonstrates that DHRP effectively mitigates congestion issues that typically plague high-density VANETs, likely due to the interference suppression enabled by the Eco Mode (18 dBm) power control mechanism.

6. Discussion

This study proposed the Dynamic Hybrid Routing Protocol (DHRP) as a context-aware framework that jointly optimizes routing adaptation and transmission-power control through a unified decision plane, aiming to address the long-standing scalability–latency–energy trade-off in VANETs. Unlike many hybrid designs that switch routing modes using a single criterion, DHRP employs a multi-criterion hierarchy (speed, density with hysteresis, and distance) and couples this logic with a three-tier power management strategy (Eco/Standard/Boost) to regulate interference and conserve energy while maintaining connectivity.

6.1. Interpretation of Results in Relation to Prior Hybrid Designs

From the perspective of prior hybrid AODV/OLSR studies, the core limitation is often that switching is reactive (triggered after link failures or congestion symptoms) and power control is not co-designed with routing, which can leave dense networks vulnerable to uncontrolled broadcast propagation and channel contention. In contrast, DHRP explicitly targets these gaps by integrating power modulation into the routing controller and by introducing predictive switching based on mobility conditions. This architectural choice directly supports the working hypothesis that cross-layer co-design can improve reliability and timeliness without sacrificing energy efficiency under heterogeneous traffic densities.

6.2. Synergistic Impact of Cross-Layer Power Control

The experiments further show that energy efficiency and connectivity need not be conflicting objectives when routing and power are jointly managed. DHRP achieves substantial energy savings (up to 60%), attributed primarily to Eco Mode operation in dense clusters.

Importantly, reducing transmission power yields a dual effect: (i) it preserves the energy budget of on-board units and (ii) it lowers aggregate interference, improving the local SINR and stabilizing nearby links. This outcome contrasts with ENDRE-VANET, which includes energy-related awareness but does not implement a fully dynamic, integrated transmission-power adjustment mechanism, allowing higher interference to persist in dense regimes.

The consistently high energy-efficiency range reported for the proposed approach (remaining tightly bounded around ~94–97% across densities) further suggests that the proposed power-aware control remains robust as contention increases. This aligns with recent findings suggesting that cross-layer optimization parameters are critical for enhancing the lifespan of vehicular nodes in heterogeneous networks [32].

6.3. Broader Implications for Practical ITS Deployments

From a deployment perspective, the results suggest that routing scalability in VANETs cannot be fully achieved solely at the network layer; interference-aware operation at the physical layer is essential as density increases. The DHRP design demonstrates a practical blueprint for such cross-layer control by combining: (i) mobility-driven proactive stabilization, (ii) density-aware hysteresis switching to avoid oscillatory mode changes, and (iii) transmission-power modulation (Eco/Standard/Boost) tailored to congestion and connectivity demands.

This integrated approach is especially relevant for next-generation ITS use cases that require both reliability and bounded latency under rapidly changing traffic densities. The proposed DHRP provides a context-aware architectural framework for self-organizing, high-mobility wireless networks. By unifying routing adaptation with transmission-power control under a single decision plane, the protocol addresses the classical trade-off between scalability and latency in dense and dynamic vehicular environments.

6.4. Mitigation of the Broadcast Storm Problem

A key observation from the results (

Figure 5) is the severe performance collapse of the traditional hybrid baseline, which exhibits end-to-end delays exceeding 2000 ms under high-load conditions. This behavior is consistent with the broadcast storm problem, where unmanaged flooding and excessive control dissemination saturate the shared wireless medium. As vehicle density increases, the resulting contention and collisions trigger repeated retransmissions and prolonged MAC-layer exponential back-off, ultimately destabilizing routing and increasing latency.

In contrast, DHRP employs an Eco Mode (18 dBm) in high-density regimes to reduce the effective collision domain and contain broadcast propagation. This mechanism limits channel saturation and maintains delay within a safety-relevant bound, keeping end-to-end latency consistently below 40 ms even when the network scales to 500 vehicles [92]. These findings indicate that cross-layer power containment is an effective mechanism for improving timeliness in dense VANET deployments.

6.5. Predictive Versus Reactive Switching

Another distinctive advantage of DHRP is the use of vehicular speed as a pre-emptive switching trigger. Conventional hybrid protocols typically react to topology changes after link breaks or packet losses are detected. In DHRP, the routing mode transitions to the more robust OLSR configuration once a vehicle exceeds 80 km/h, thereby anticipating impending topological instability before it degrades communication performance. This predictive behavior is a significant factor behind the sustained delivery reliability observed in the experiments, enabling the protocol to maintain PDR > 90% under varying mobility conditions.

6.6. Limitations and Future Work

Despite its strong performance in urban and highway settings, DHRP has limitations. The decision process depends on accurate, real-time context inputs (e.g., speed and GPS-derived measures) to estimate density and inter-node distance. In environments characterized by GPS denial or severe signal shadowing (e.g., tunnels or dense urban canyons), distance estimation may become unreliable and could lead to suboptimal mode selection or power configuration.

Future work will investigate learning-based mobility prediction to improve resilience against sensor uncertainty or data loss and will evaluate the protocol under larger-scale conditions (e.g., networks exceeding 1000 nodes) to further validate scalability in extreme-density deployments.

7. Conclusions

This study introduced DHRP, a context-aware hybrid routing protocol for VANETs that integrates AODV and OLSR with a cross-layer transmission-power control module. By selecting routing behaviour based on mobility and density indicators and dynamically adjusting transmission power to mitigate interference, DHRP achieves consistently high performance across a wide range of traffic densities. Specifically, the proposed protocol maintains PDR > 90% and end-to-end delays below 40 ms, while significantly improving scalability and energy efficiency compared with state-of-the-art baselines (e.g., ENDRE-VANET). The results provide a validated foundation for developing reliable and energy-aware communication support for next-generation Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.G.; data curation, B.G.; formal analysis, B.G.; investigation, B.G.; methodology, B.G.; supervision, F.T.; validation, B.G.; visualization, B.G.; writing—original draft, B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare no funding is available.

Data Availability Statement

The simulation data, including NS-3 configuration scripts and SUMO mobility traces used to support the findings of this study, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tamilarasi, A.; Sivabalaselvamani, D.; Loganathan, R.; Adhithyaa, N. A hybrid model for performance evaluation of fixed VANETs using novel 1C3N and topology-based ad-hoc routing protocols with packet loss control methods. Int. Res. J. Multidiscip. Technov. 2023, 5, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jyothi, S.A.; Singla, A.; Godfrey, P.B.; Kolla, A. Measuring and understanding the throughput of network topologies. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1402.2531. [Google Scholar]

- Onuora, A.C.; Essien, E.E.; Ogban, F.U. An adaptive hybrid routing protocol for efficient data transfer and delay control in mobile ad hoc networks. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2023, 71, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlDulaimi, A.M.K.; Abbas, F.H.; Mahdi, Q.S.; Alkhayyat, A.H.R.; Alsalamy, A.A. Effective neighbour discovery-based routing in emergency VANETs. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Conference on Engineering Technology and its Applications (IICETA), Najaf, Iraq, 19–20 September 2023; pp. 324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ahwal, A. Performance prediction for AODV, AOMDV, and hybrid protocols in high-density networks. Eng. Res. J. (ERJ) 2022, 51, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengag, A.; Bengag, A.; Elboukhari, M. Routing protocols for VANETs: A taxonomy, evaluation and analysis. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2020, 5, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dalahmeh, M.; El-Dalahmeh, A.; Adeel, U. Analyzing the performance of AODV, OLSR, and DSDV routing protocols in VANET based on the ECIE method. IET Netw. 2024, 13, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, D.; Deshmukh, M. Adaptive hybrid routing protocol for VANETs. Int. J. Recent Innov. Trends Comput. Commun. 2017, 5, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, S.; Joardar, A.; Das, A.; Majumder, K. Performance analysis of three routing protocols in MANET using the NS-2 and ANOVA test. In Ad Hoc Networks; Mostafa, A., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, A.G.; Shaker, M.S. Vehicular ad-hoc network (VANET)—A review. In Proceedings of the 2022 Iraqi International Conference on Communication and Information Technologies (IICCIT), Basrah, Iraq, 7–8 September 2022; pp. 367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Jenila, B.S.; Ashvini, S. A hybrid routing protocol for VANETs. Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Commun. Eng. 2014, 2, 5056–5061. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar, W.; Malaney, R. Mobility models and the performance of location-based routing in VANETs. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 92nd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Fall), Victoria, BC, Canada, 18 November–16 December 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kushwaha, U.S.; Jain, N.; Malviya, J.; Dhummerkar, M. Comparative analysis of DSR, AODV, AOMDV, and AOMDV-LR in VANET by increasing the number of nodes and speed. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 16, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Hasan, M.; Padmanabhan, S. End-to-end network delay guarantees for real-time systems using SDN. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1509.06969. [Google Scholar]

- Seema; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S.K.; Khan, S.A.; Singh, P. Simulation-based performance evaluation of VANET routing protocols under Indian traffic scenarios. ICIC Express Lett. 2022, 16, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Manhar, A.; Dembla, D. Routing optimising decisions in MANET: The enhanced hybrid routing protocol (EHRP) with adaptive routing based on network situation. Int. J. Recent Innov. Trends Comput. Commun. 2023, 11, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Chakraborty, S. Improvement of packet delivery ratio in MANET using ADLR: A modified regularisation-based Lasso regression. J. Adv. Inf. Technol. 2024, 15, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi Uddin, K.M.; Islam, N.; Akhtar, J. Implementing the AODV routing protocol in VANET using SDN. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2020, 175, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, R.; Naidu, R.C.A.; S, M. Hybrid multihop routing mechanism with intelligent transportation system architecture for efficient routing in VANETs. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Disruptive Technologies for Multi-Disciplinary Research and Applications (CENTCON), Mysuru, India, 29–31 November 2022; pp. 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, A.M.; et al. An improved hybrid routing approach for disaster management in MANET. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Science and Technology (ICES&T), Karachi, Pakistan, 15–16 March 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kour, S.; et al. Comparative analysis of low and high scalable VANET in terms of receive rate, packets received, MAC/PHY overhead and average goodput. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 230, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbayti, O.; Housni, K.; Hanin, M.; El Makrani, A. Comparative study of proactive and reactive routing protocols in vehicular ad-hoc networks. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2023, 13, 5374–5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kour, S.; Sarangal, H. Modelling and simulation of VANET routing protocols under realistic mobility patterns. Research Square 2024, rs.3.rs-7463391, (Preprint). [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, A.; Puntambekar, S. Reactive & multipath routing with adaptive urban area vehicular traffic (AUAVT) in VANET environment. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 2024, 12, 802–810. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Wu, H.; He, Y.; Li, Q. A multi-objective optimized OLSR routing protocol. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubori, A.; Al-Raweshidy, H. Bio-inspired hybrid routing protocol for enhanced stability in high-mobility VANETs. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, K. Adaptive transmission power control based on deep reinforcement learning for VANETs. Veh. Commun. 2023, 41, 100602. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Agrawal, S. Comparative performance analysis of AODV, OLSR and DSR in realistic urban scenarios using SUMO and NS-3. Wireless Pers. Commun. 2023, 129, 2105–2123. [Google Scholar]

- Menouar, H.; Massi, I. Next-generation congestion control for V2X: A hybrid approach. Sensors 2024, 24, 512. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.; Ullah, I.; Alkinani, M.H.; Almazroi, A. Integration of VANETs with 5G: A survey on routing protocols and open challenges. Electronics 2023, 12, 890. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hadhrami, Y.; Al-Fayez, F. Performance Evaluation of Topology-Based Routing Protocols for VANETs in Urban Scenarios. Electronics 2023, 12, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Khan, S. Cross-Layer Design for Energy-Efficient Routing in VANETs: A Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |