Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

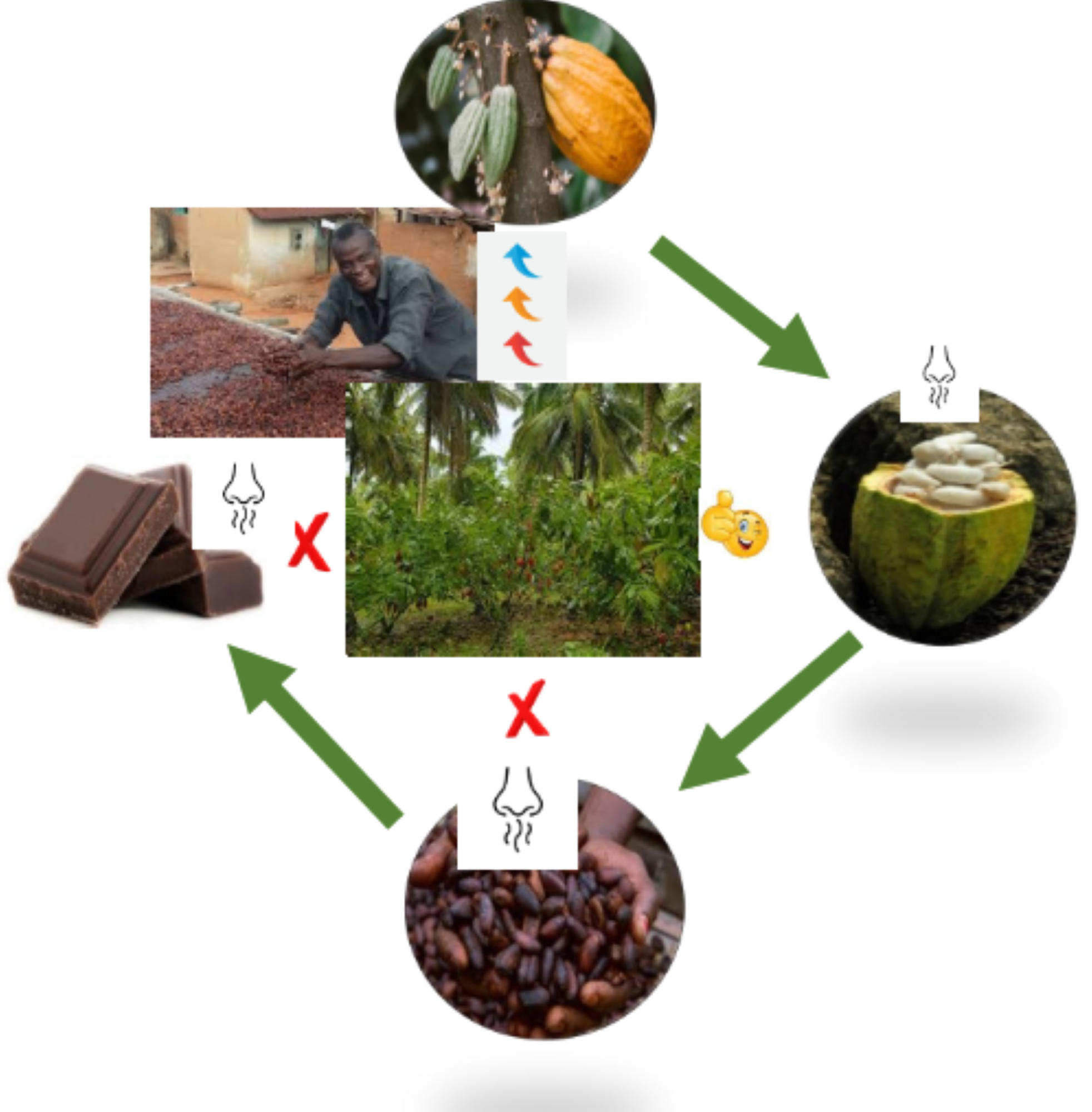

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Méthods

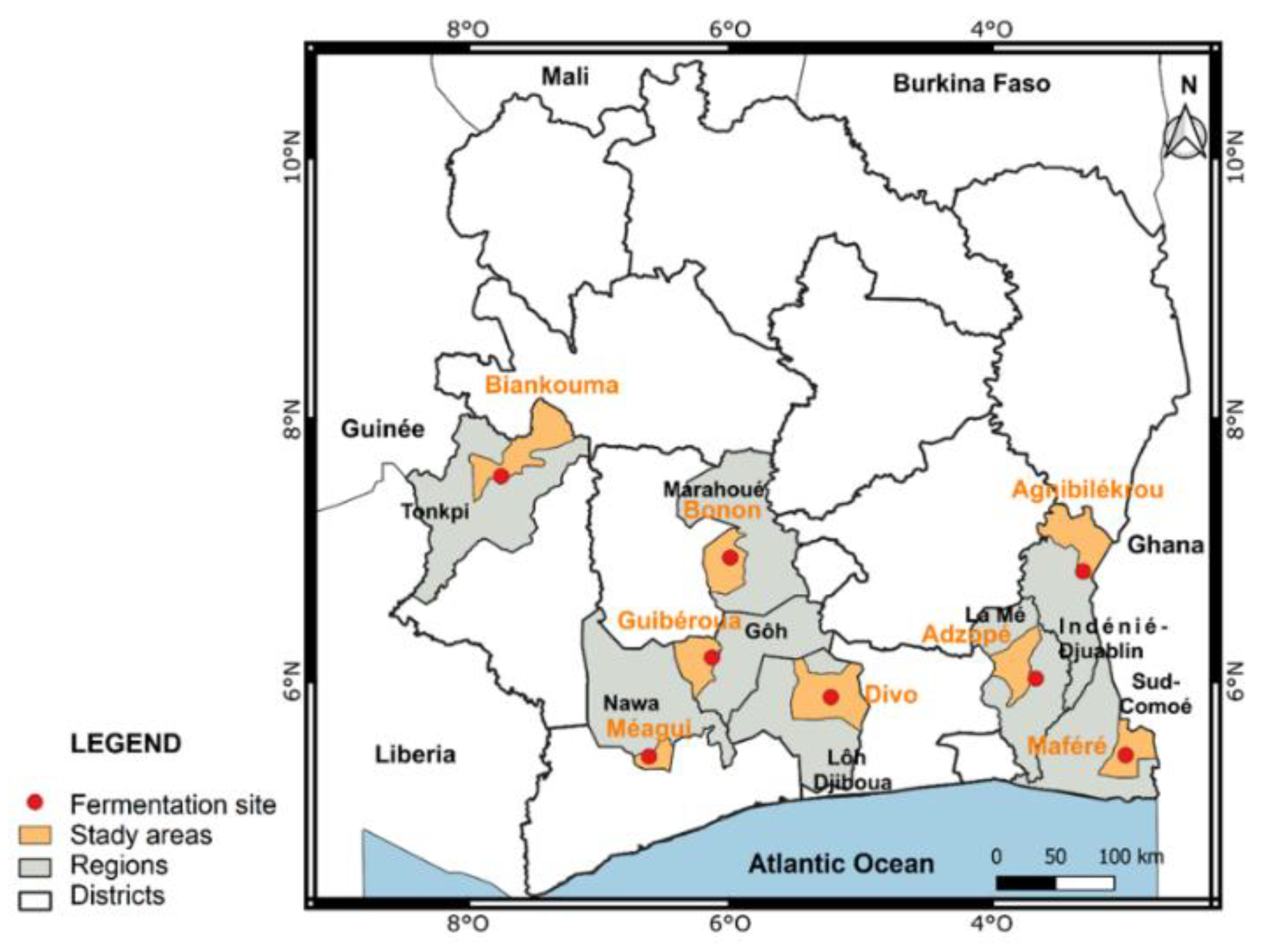

2.1. Sites of Carrying Out of Research Works

2.2. Materials

3. Methods

3.1. Cocoa Beans Fermentation

3.2. Cocoa Beans Sampling

3.3. Cocoa Volatile Compounds Analysis

3.4. Sensory Analysis of Chocolate

3.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

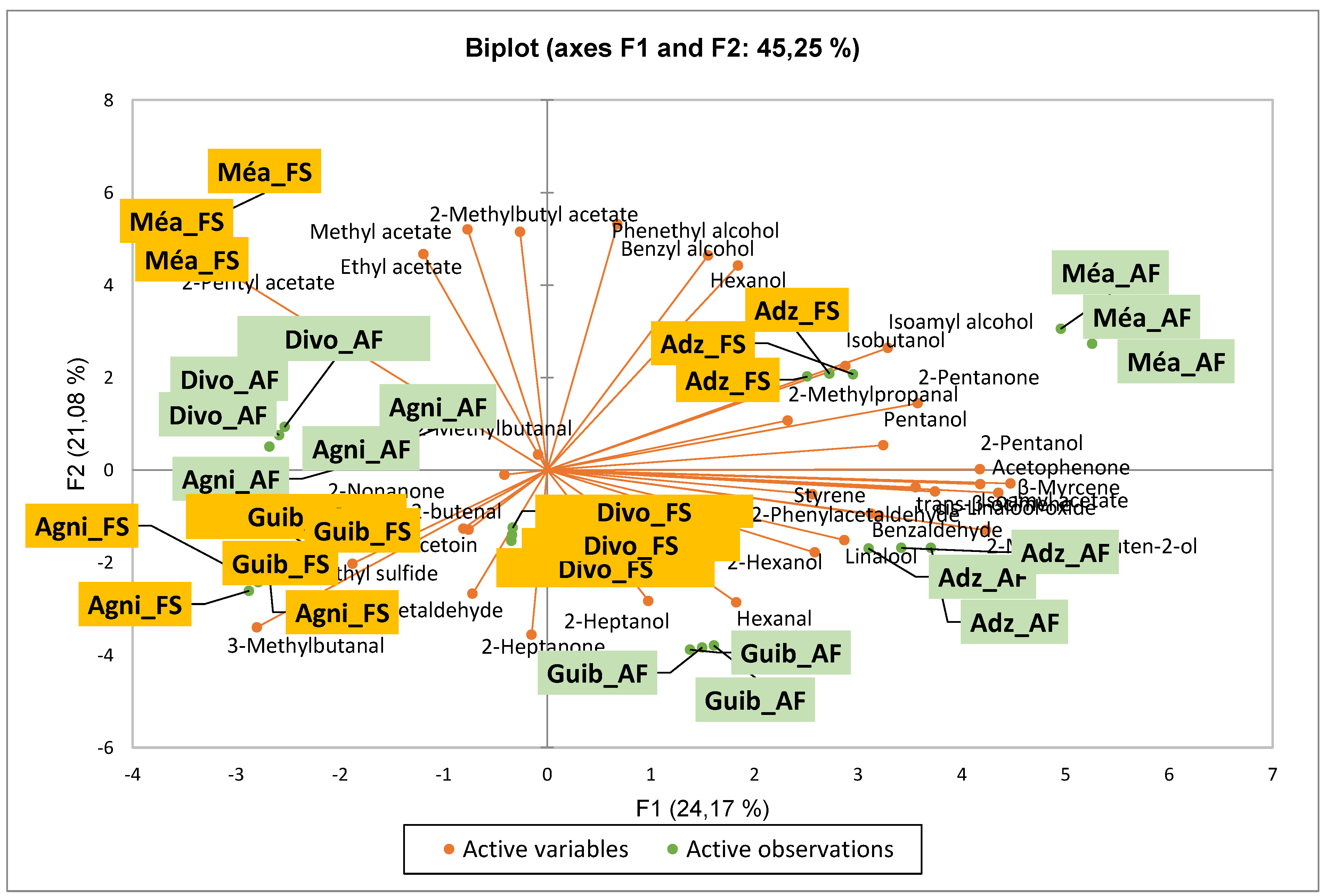

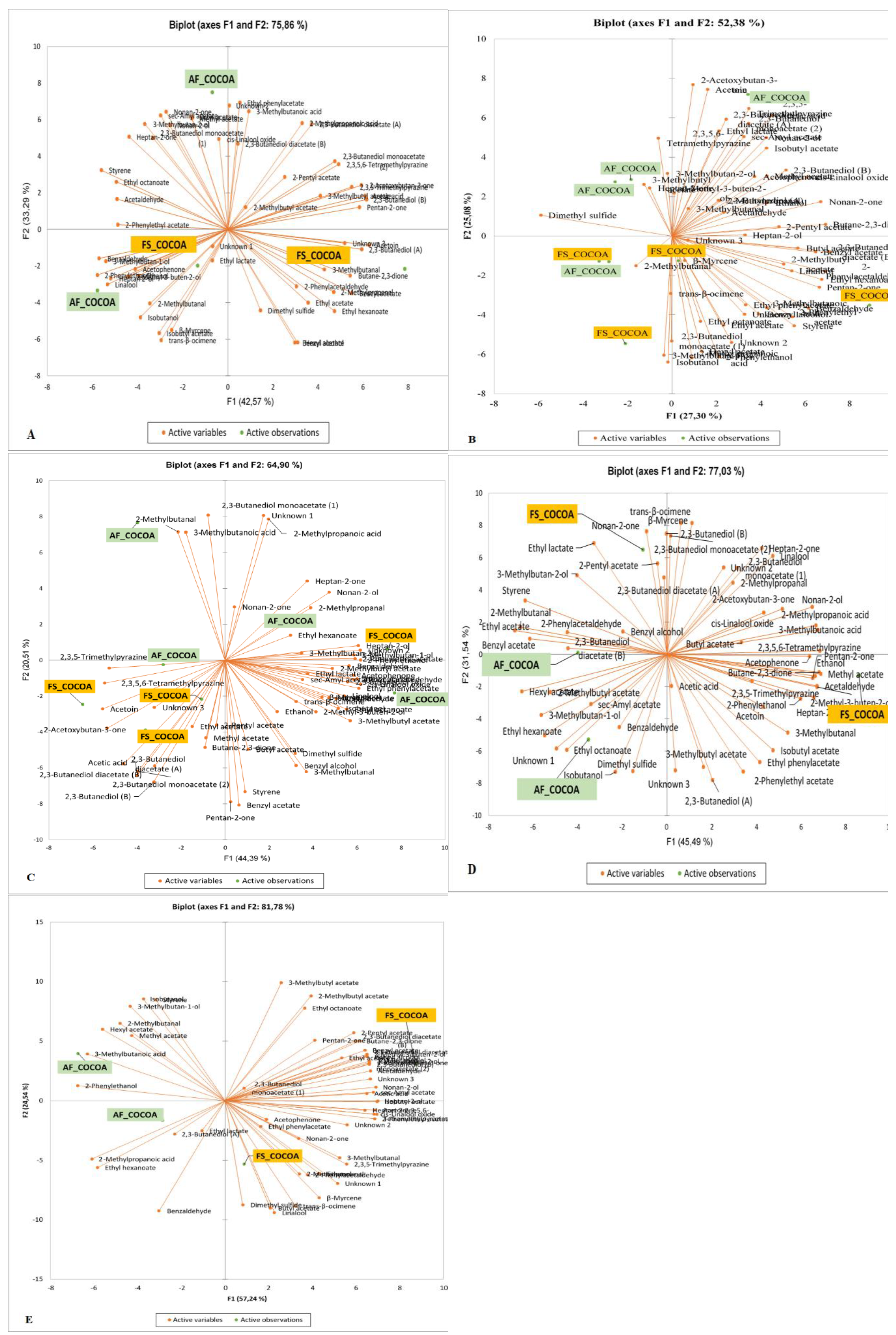

3.1. Effect of Agroforestry on Native Flavor Compound Contents of Crude Cocoa Beans

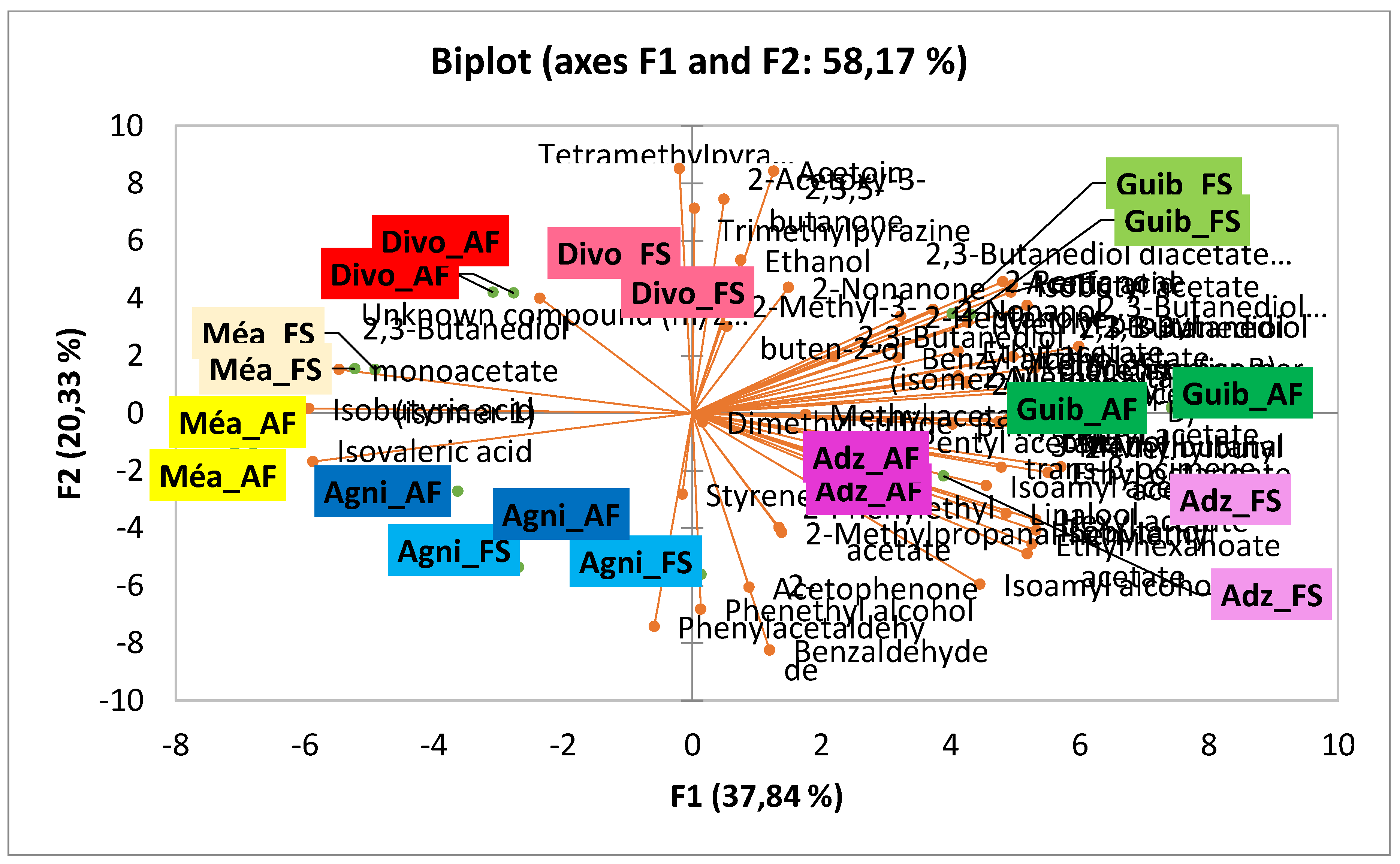

3.2. Effect of Agroforestry on Flavor Compound Contents of Dry Fermented Cocoa Beans

| Chemical families | Flavor compounds class contents (µg.g−1) of dry fermented cocoa beans from Ivorian cocoa producing areas | |||||||||

| Adzopé | Agnibilékrou | Divo | Guibéroua | Méagui | ||||||

| Cropping systems | ||||||||||

| AF | FS | AF | FS | AF | FS | AF | FS | AF | FS | |

| Aldehydes | 456.08±77.6a | 428.83±59.8a | 147.14±51b | 243.18±77.3b | 159.53±5.90.b | 251.36±46.7b | 456.77±2a | 461.03±21a | 182.59±17.7b | 213.64±54.2b |

| Esters | 75.04±20.3b | 68.46±2.3b | 70.06±7.72b | 132.47±44.9a | 35.97±14.06.71c | 34.02±3.4b | 117.68±9.7a | 57.03±16.1b | 44.6±1.3bc | 52.48±7.4b |

| Alcohols | 385.67±259.1a | 169.43±8.32a | 158.73±50.17a | 190.88±10.22a | 269.45±111a | 220.05±207.6a | 273.2±10.6a | 155.31±3.6a | 83.31±1.2a | 165.66±95.3a |

| Ketons | 44.84±12.2b | 72.69±32.2c | 51.97±14.19b | 40.55±12.76c | 125.18±49.13a | 131.68±1.6ab | 86.36±9ab | 154.46±4.9a | 42.17±20.2b | 85.76±27.9bc |

| Acids | 630.34±149.2ab | 755.03±185.7ab | 476.18±19.82ab | 485.29±167.23b | 588.29±120.52ab | 912.74±149a | 742.04±11a | 821.41±51.4ab | 401.23±117.2b | 529.77±149.8ab |

| Pyrazines | 16.23±6.61bc | 16.94±8.8bc | 9.53±7.24c | 4.6±2.92c | 70.61±28.51a | 68.78±15.71ab | 56.92±20.51ab | 81.15±27.9a | 20.57±12.6bc | 64.25±17.8ab |

| Terpenes | 10.79±2.20a | 11.39±1.80a | 8.48±3.32a | 12.3±14a | 4.28±3.34ab | 2.27±0.51c | 7.59±2.4ab | 6.21±1.2b | 1.73±0.9b | 3.72±0.9bc |

| Others | 13.14±6.63b | 12.21±5.61b | 4.83±2.79b | 7.8±4.72b | 5.02±0.42b | 54.18±0.34a | 46.08±9.1a | 53.93±6.8a | 2.13±0.1b | 8.77±6.5b |

3.6. Effects of Agroforestry on the Desirable Flavor Compounds of Dry Fermented Cocoa Beans Different Producing Geopgraphical Origins

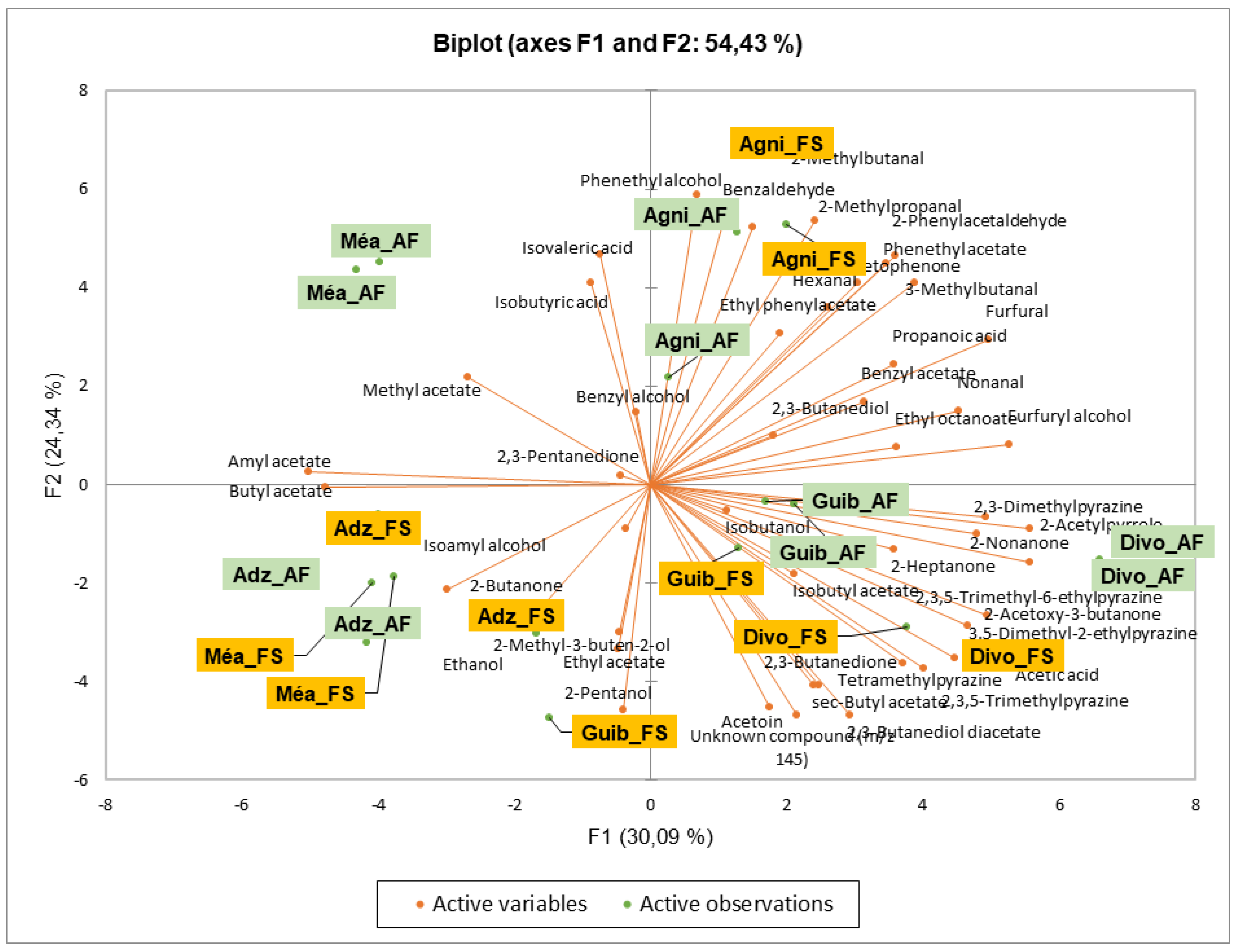

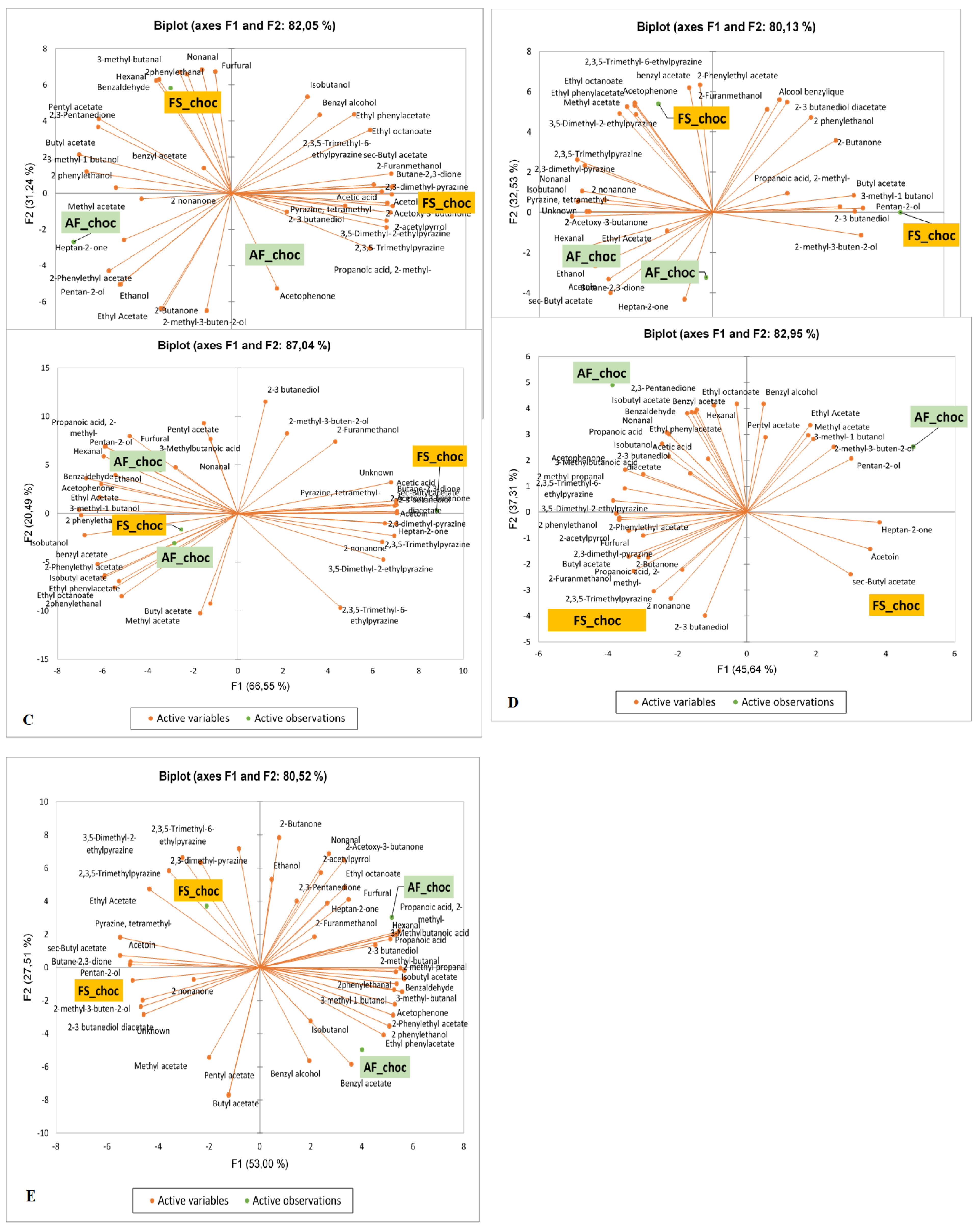

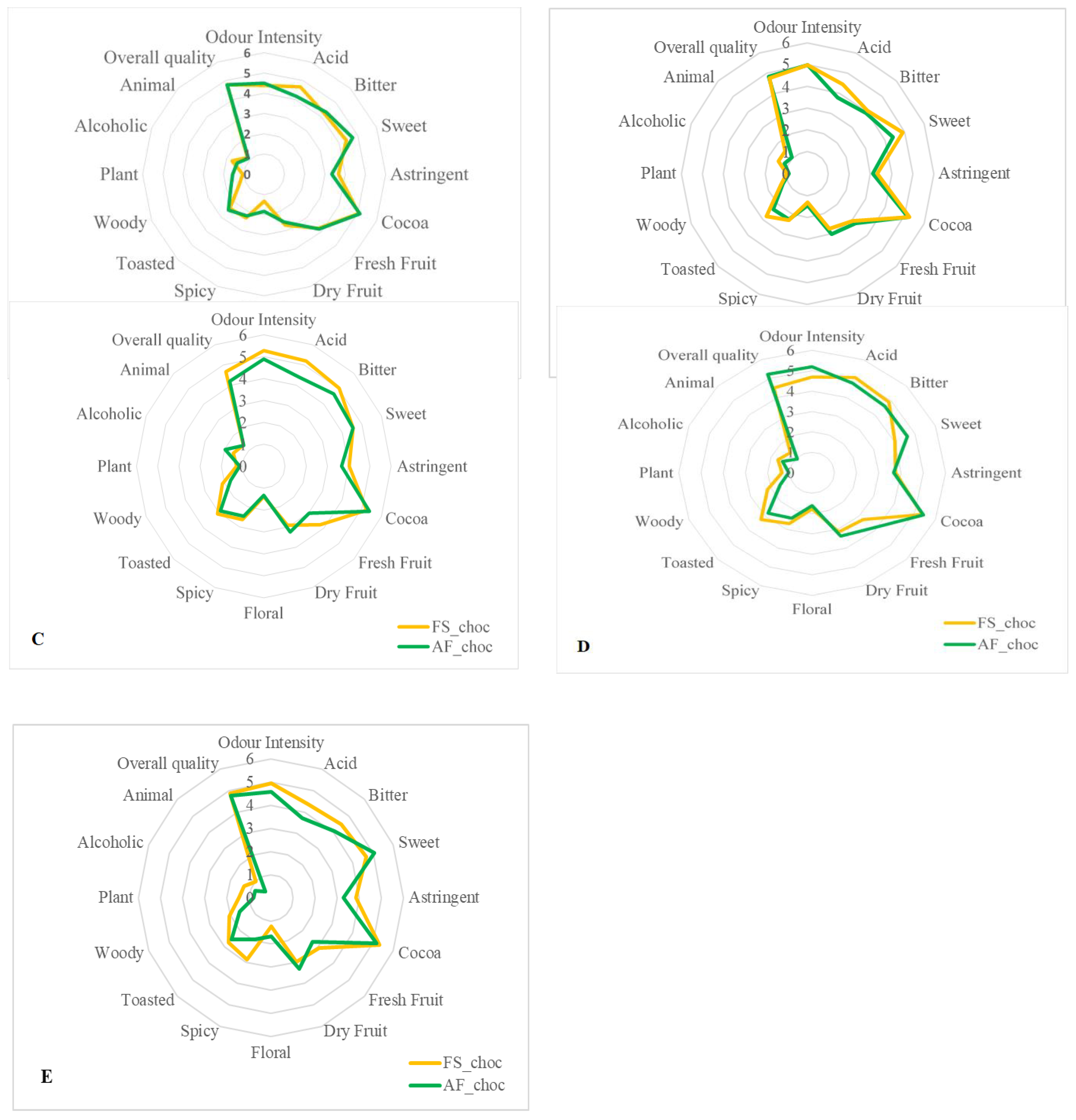

3.7. Effects of Agroforestry on the Flavor Compound Profiles of Chocolates Produced from Dry Fermented Cocoa Within Each Producing Geographical Origin.

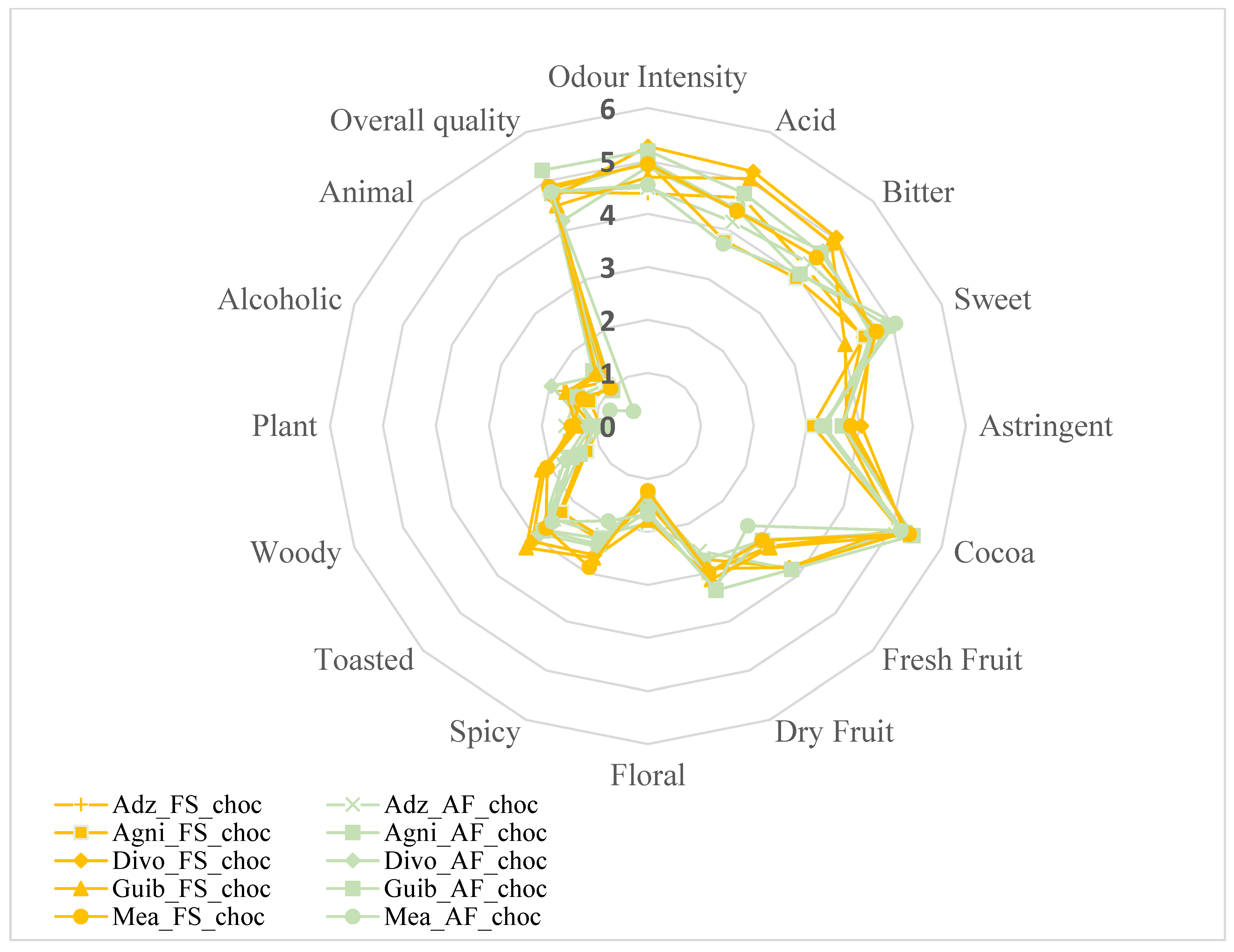

3.9. Effects of Agroforestry on the Sensory Perception of Chocolate Samples

4. Conclusions

Funding

Authors contribution

Data Availability Statement

Aknowledgements

Conflicts of interest

References

- Pedan, V.; Fischer, N.; Bernath, K.; Hühn, T. , Rohn, S. Determination of oligomeric proanthocyanidins and their antioxidant capacity from different chocolate manufacturing stages using the NP HPLC-online-DPPH methodology. Food Chem, 10.1016/j.foodc hem.2016.07.094.

- Jahurul, M.H.A.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Norulaini, N.A.N.; Sahena, F.; Jinap, S.; Azmir, J.; Sharif, K. M.; Omar, A.K.M. Cocoa butter fats and possibilities of substitution in food products concerning cocoa varieties, alternative sources, extraction methods, composition, and characteristics. Journal of Food Engineering, 2013, 117, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICCO (2024). Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics, Vol. L, No. 2, Cocoa year 2023/24. International Cocoa Organization, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire.

- Kalischek, N.; Lang, N.; Renier, C.; Daudt, R.C.; Addoah, T.; Thompson, W.; Blaser-Hart, W.J.; Garrett, R.; Schindler, K. Wegner, J. D. Cocoa plantations are associated with deforestation in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Nature Food, 2023, 4, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achaw, O.W.; Danso-Boateng, E. (2021). Cocoa Processing and Chocolate Manufacture. In: Chemical and Process Industries. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Santander Muñoz, M.; Rodríguez Cortina, J.; Vaillant, F.E.; Escobar Parra, S. An overview of the physical and biochemical transformation of cocoa seeds to beans and to chocolate: Flavor formation. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. [CrossRef]

- Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Luca, S.V.; Miron, A. Flavor chemistry of cocoa and cocoa products—an overview. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2016, 15, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltini, R.; Akkerman, R.; Frosch, S. Optimizing chocolate production through traceability: A review of the influence of farming practices on cocoa bean quality. Food control, 2013, 29, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Heimdal, H. Effect of fermentation method, roasting and conching conditions on the aroma volatiles of dark chocolate. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 4: 36 (5). [CrossRef]

- Kongor, J.E. ; M. Hinneh, M. ; de Walle, D.V. ; Afoakwa, E.O. ; Boeckx, P.; Dewettinck, K. Factors influencing quality variation in cocoa (Theobroma cacao) bean flavor profile – A review. Food Research International,. [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.; J. , Almeida, M.H.; Nout, M.R.; Zwietering, M.H. Theobroma cacao L.,“The food of the Gods”: quality determinants of commercial cocoa beans, with particular reference to the impact of fermentation. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 2011, 51, 731–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadow, D.; Niemenak, N.; Rohn, S.; Lieberei, R. Fermentation-like Incubation of Cocoa Seeds (Theobroma cacao L.)—Reconstruction and Guidance of the Fermentation Process. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hue, C.; Gunata, Z.; Breysse, A.; Davrieux, F.; Boulanger, R.; Sauvage, F.X. Impact of fermentation on nitrogenous compounds of cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) from various origins. Food Chemistry, 9: 192. [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Weckx, S. The cocoa bean fermentation process: from ecosystem analysis to starter culture development. Journal of applied microbiology. [CrossRef]

- Crafack, M.; Mikkelsen, M.B.; Saerens, S.; Knudsen, M.; Blennow, A.; Lowor, S.; Takrama, J.; Swiegers, J.H.; Petersen, G.B.; Heimdal, H.; Nielsen, D.S. Influencing cocoa flavor using Pichia kluyveri and Kluyveromyces marxianus in a defined mixed starter culture for cocoa fermentation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 1: 167. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J.; Lieberei, R. Biochemistryof cocoa fermentation. Cocoa and coffee fermentations.

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Quao, J.; Takrama, J.; Budu, A.S.; Saalia, F.K. Chemical composition and physical quality characteristics of Ghanaian cocoa beans as affected by pulp pre-conditioning and fermentation. Journal of food science and technology, 2013, 50, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanquah, D.T. 2013.

- Parra-Paitan, C.; Meyfroidt, P.; Verburg, P.H.; zu Ermgassen, E.K. Deforestation and climate risk hotspots in the global cocoa value chain. Environmental Science & Policy, 2024, 158, 103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraatpisheh, M.; Bakhshandeh, E.; Hosseini, M.; Alavi, S.M. Assessing the effects of deforestation and intensive agriculture on the soil quality through digital soil mapping. Geoderma, 2020, 363, 114139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroth, G.; da Fonseca, G.A.; Harvey, C.A.; Gascon, C.; Vasconcelos, H.L.; Izac, A.M.N. (Eds.) . Agroforestry and Biodiversity Conservation in Tropical Landscapes. 2004. Island Press, Washington DC.

- Greenberg, R. Biodiversité dans l'agroécosystème cacaoyer : gestion de l'ombre et considérations paysagères. 2014. https://repositorio.catie.ac. 1155. [Google Scholar]

- Middendorp, R.S.; Vanacker, V.; Lambin, E.F. Impacts of shaded agroforestry management on carbon sequestration, biodiversity and farmers income in cocoa production landscapes. Landscape Ecology, 2018, 33, 1953–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.B.; Rawale, G.B.; Pradhan, A.; Uthappa, A.R.; Kakade, V.D.; Morade, A.S.; Paul, N.; Das, B.; Chichaghare, A.R.; Changan, S.; Khapte, P.S.; Basavaraj, P.S.; Babar, R.; Salunkhe, C.; Jinger, D.; Nangare, D.D.; Reddy, KS. Optimizing tree shade gradients in Emblica officinalis-based agroforestry systems: impacts on soybean physio-biochemical traits and yield under degraded soils. Agrofrestry Systemes, 2025, 99, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; McGraw, M.L.; George, M.F. ; Garret., S.E. Nutritive quality and morphological development under partial shade of some forage species with agroforestry potential. Agroforestry Systems,. [CrossRef]

- Guehi, T.S.; Dadie, A.T.; Koffi, K.P.; Dabonne, S.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Kedjebo, K.D.; Nemlin, G.J. Performance of different fermentation methods and the effect of their duration on the quality of raw cocoa beans. International journal of food science & technology, 2010, 45, 2508–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouassi, A.D.D.; Koné, K.M.; Assi-Clair, B.J.; Lebrun, M.; Maraval, I.; Boulanger, R.; Guéhi, T.S. (2022). Effect of spontaneous fermentation location on the fingerprint of volatile compound precursors of cocoa and the sensory perceptions of the end-chocolate. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2022, 59, 4466–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koné, M.K.; Guéhi, S.T.; Durand, N.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Berthiot, L.; Tachon, A.F.; Brou, K. , Boulanger, R. ; Montet, D. Contribution of predominant yeasts to the occurrence of aroma compounds during cocoa bean fermentation. Food Research International, 89. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.B.; Amorim, L.R.; Nonato, M.A.; Roselino, M.N.; Santana, L.R.; Ferreira, A.C. , Rodrigues, F.M.; Mesquita, P.R.R.; Soares, S. E. Optimization of HS-SPME/GC-MS method for determining volatile organic compounds and sensory profile in cocoa honey from different cocoa varieties (Theobroma cacao L.). Molecules, 3194; 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi-Clair, B.J.; Koné, M.K.; Kouamé, K.; Lahon, M.C.; Berthiot, L.; Durand, N.; Lebrun, M.; Julien-Ortiz, A.; Maraval, I.; Boulanger, R. , Guéhi, T.S. Effect of aroma potential of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation on the volatile profile of raw cocoa and sensory attributes of chocolate produced thereof. European Food Research and Technology, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander, M.; Leguizamón, L.; Vaillant, F.; Boulanger, R.; Zuluaga, M.; Maraval, I.; Rodriguez, J.; Liano, S.; Sommerer, N.; Meudec, E.; Meter, A.; Escobar, S. Influence of driven fermentation of cacao in bioreactors on quality: decoding the effect of temperature, mixing, and pH on metabolomic, sensory, and volatile profiles. LWT, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wu, B.; Qin, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Yan, L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, G.; Li, F. Quality differences and profiling of volatile components between fermented and unfermented cocoa seeds (Theobroma cacao L.) of Criollo, Forastero and Trinitario in China. Beverage Plant Research, 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzwieser, J.; Schnitzler, J.P.; Steinbrecher, R. Biosynthesis of organic compounds emitted by plants. Plant Biology, 1999, 1, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmerer, T.W.; MacDonald, R.C. Acetaldehyde and ethanol biosynthesis in leaves of plants. Plant Physiology, 1987, 84, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missihoun, T.D.; Kotchoni, S.O. Aldehyde dehydrogenase and the hypotheisis of a glycolaldehyde shunt pathway of photorespiration. Plant signaling & behavior, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Li, R.; Chu, Z.; Zhu, K.; Gu, F.; Zhang, Y. Chemical and flavor profile changes of cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) during primary fermentation. Food Science & Nutrition, 4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konan, G.D.; Kpangui, K.B.; Kouakou, K.A.; Barima, Y.S.S. (2023). Typologie des systèmes agroforestiers à base de cacaoyers selon le gradient de production cacaoyère en Côte d’Ivoire: Typology of cocoa-based agroforestry systems according to the cocoa production gradient in Côte d'Ivoire. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences, 2023, 17, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvadet, M.; Van den Meersche, K.; Allinne, C.; Gay, F.; de Melo Virginio Filho, E.; Chauvat, M.; Becquer, T.; Tixier, P.; Harmand, J.M. Shade trees have higher impact on soil nutrient availability and food web in organic than conventional coffee agroforestry. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 649, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koné, K.M.; Assi-Clair, B.J.; Kouassi, A.D.D.; Yao, A.K.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Durand, N.; Guéhi, T.S. Pod storage time and spontaneous fermentation treatments and their impact on the generation of cocoa flavour precursor compounds. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2516; 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseglia, A.; Musci, M.; Rinaldi, M.; Palla, G.; Caligiani, A. Volatile fingerprint of unroasted and roasted cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) from different geographical origins. Food Research International, 2020, 132, 109101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottiers, H.; Tzompa Sosa, D.A.; De Winne, A.; Ruales, J.; De Clippeleer, J.; De Leersnyder, I.; De Wever, J.; Everaery, H.; Messens, K.; Dewettinck, K. Dynamique des composés volatils et des précurseurs d'arômes lors de la fermentation spontanée de fèves de cacao Trinitario de qualité supérieure. European Food Research and Technology, 2019, 245, 1917–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Campos, J.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Contreras-Ramos, S.M.; Orozco-Avila, I.; Jaramillo-Flores, E.; Lugo-Cervantes, E. Effect of fermentation time and drying temperature on volatile compounds in cocoa. Food chemistry, 2012, 132, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinap, S.; Ikrawan, Y.; Bakar, J.; Saari, N.; Lioe, H.N. Aroma precursors and methylpyrazines in underfermented cocoa beans induced by endogenous carboxy peptidase. Journal of Food Science, 2008, 73, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puziah, H.; Jinap, S.; Sharifah, K.S.M.; Asbi, A. Changes free amino acid, peptide, sugar and pyrazine concentration during cocoa fermentation. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 1998, 78, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, N.; Hassan, O.; Said, M.; Samsudin, W.; Idris, N.A. Influence of roasting conditions on volatile flavor of roasted Malaysian cocoa beans. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 2006, 30, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.T.T.; Zhao, J.; Fleet, G. Yeasts are essential for cocoa bean fermentation. International journal of food microbiology, 2014, 174, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayek, N.M.; Xiao, J.; Farag, M.A. A multifunctional study of naturally occurring pyrazines in biological systems; formation mechanisms, metabolism, food applications and functional properties. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2023, 63, 5322–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, H.G.; Koffi, B.L.; Karou, G.T.; Sangaré, A.; Niamke, S.L.; Diopoh, J.K. Implication of Bacillus sp. in the production of pectinolytic enzymes during cocoa fer mentation. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2008, 24, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reineccius, G.A.; Keeney, P.G.; Weissberger, W. (1972). Factors affecting the concentration of pyrazines in cocoa beans. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 1972, 20, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinneh, M.; Semanhyia, E.; Van de Walle, D.; De Winne, A.; Tzompa-Sosa, D.A. , Scalone, G.L.L.; De Meulenaer, B.; Messens, K.; Durme, J.V.; Afoakwa, E.O.; De Cooman, L.; Dewettinck, K. Assessing the influence of pod storage on sugar and free amino acid profiles and the implications on some Maillard reaction related flavor volatiles in Forastero cocoa beans. Food Research International, 2018, 111, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouamé, C.; Loiseau, G.; Grabulos, J.; Boulanger, R.; Mestres, C. Development of a model for the alcoholic fermentation of cocoa beans by a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2021, 337, 108917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetschik, I.; Pedan, V.; Chatelain, K.; Kneubühl, M.; Hühn, T. Characterization of the flavor properties of dark chocolates produced by a novel technological approach and comparison with traditionally produced dark chocolates. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.; Frey, L.J.; Berger, A.; Bolten, C.J.; Hansen, C.E. , Wittmann, C. The key to acetate: metabolic fluxes of acetic acid bacteria under cocoa pulp fermentation-simulating conditions. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 4702; 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafack, M.; Keul, H.; Eskildsen, C.E.; Petersen, M.A.; Saerens, S.; Blennow, A.; Skovmand-Larsen, M.; Swiegers, J.H.; Petersen, G.B.; Heimdal, H.; et al. Impact of starter cultures and fermentation techniques on the volatile aroma and sensory profile of chocolate. Food Res. Int. 2014, 63, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meersman, E.; Steensels, J.; Struyf, N.; Paulus, T.; Saels, V.; Mathawan, M.; Allegaert, L.; Vrancken, G.; Verstrepen, K.J. Tuning chocolate flavor through development of thermotolerant Saccharomyces cerevisiae starter cultures with increased acetate ester production. Applied and environmental microbiology, 2016, 82, 732–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Ríos, H.G.; Suárez-Quiroz, M.L.; Hernández-Estrada, Z.J.; Castellanos-Onorio, O.P.; Alonso-Villegas, R.; Rayas-Duarte, P.; Cano-Sarmiento, C.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.Y.; González-Rios, O. Yeasts as producers of flavor precursors during cocoa bean fermentation and their relevance as starter cultures: a review. Fermentation, 2022, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegleder, G. Composition of Flavor Extracts of Raw and Roasted Cocoas. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1991, 192, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegleder, G. Linalool Contents as Characteristic of Some Flavor Grade Cocoas. Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1990, 191, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Chen, K.F.; Changchien, L.L.; Chen, K.C.; Peng, R.Y. Volatile variation of Theobroma cacao Malvaceae L. beans cultivated in Taiwan affected by processing via fermentation and roasting. Molecules, 2022, 27, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdouche, Y.; Meile, J.C.; Lebrun, M.; Guehi, T.; Boulanger, R.; Teyssier, C.; Montet, D. Impact of turning, pod storage and fermentation time on microbial ecology and volatile composition of cocoa beans. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamat, J.; Mordingah Harun, S. Formation of methyl pyrazine during cocoa bean fermentation. Pertanika, 1994, 17, 27–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Campos, J.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B.; Orozco-Avila, I.; Lugo-Cervantes, E.; Jaramillo-Flores, M.E. Dynamics of volatile and non-volatile compounds in cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) during fermentation and drying processes using principal components analysis. Food Research International, 2011, 44, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauendorfer, F.; Schieberle, P. Changes in key aroma compounds of Criollo cocoa beans during roasting. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2008, 56, 10244–10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, A.B.; da Cruz, M.L.; de Souza Oliveira, F.A.; Soares, S. :, Druzian, J.I.; de Santana, L.R.R., de Souza, C.O., Eds.; da Silva Bispo, E. Influence de la masse de cacao sous-fermentée dans la production de chocolat: Acceptation sensorielle et caractérisation du profil volatil lors de la transformation. Lwt, 2021, 149, 112048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical families | Flavor compounds content (µg.g−1) per class found in crude cocoa beans according to Ivorian cocoa producing areas | |||||||||

| Adzopé | Agnibilékrou | Divo | Guibéroua | Méagui | ||||||

| Cropping systems | ||||||||||

| AF | FS | AF | FS | AF | FS | AF | FS | AF | FS | |

| Aldehydes | 138.6±7.6a | 118.8±2.4a | 111.7±4.6ab | 102.4±12.8a | 73.7±0.9c | 116.5±2.7a | 107.6±23.5b | 116.2±41.1a | 95.7±1.2bc | 92.7±1a |

| Esters | 85.4±2b | 59.5±2.5a | 56±3.5c | 70.1±25.7a | 56.6±0.3bc | 73.2±2.8a | 65±22.1bc | 56.2±25.1a | 159.8±4.2a | 71.7±1.4a |

| Alcohols | 590.9±27.4b | 391.6±10a | 330.6±110.8c | 448.6±223.7a | 341.5±9.1c | 432.2±0.1a | 432±69.2c | 362±186.1a | 1134.4±34a | 173.9±12a |

| Ketons | 103.4±6c | 151.7±0.9a | 108.7±38.7c | 85.8±62a | 191.4±32.4b | 195.1±1.1a | 153.3±5.7b | 106.7±91.3a | 504.6±2.7a | 58.6±7a |

| Terpens | 8.5±0ab | 11±0.7a | 3.9±0.5b | 2.7±0.3c | 1.7±0.4b | 4.3±0.3b | 12.7±7.2a | 3.2±0.5c | 8.2±0.1ab | 2.9±0.1c |

| Others | 7.7±0a | 3.2±0.1c | 7.7±8.1a | 4.6±3bc | 5.9±0.4a | 8±0.2ab | 5.4±1a | 2.3±1.2c | 6.4±0.1a | 10.3±0.5a |

| 说 | Kovats index (NIST) | Calculated Kovats index | Odor description | Cropping system | Concentration of flavor compounds of cocoa beans from producing regions (µg.g−1) | ||||

| Adz | Agni | Divo | Guib | Méa | |||||

| 3-Methylbutyl acetate | 1123 | 1123 | Fruity, banana | AF | 47,7±17b | 2,2±0,1c | 2,8±1,2c | 84,2±3,7a | 15,8±2,9c |

| FS | 75,2±2,9a | 37,2±9,1ab | 33,2±36,3ab | 41,9±17ab | 18,6±9,4b | ||||

| 2-Methylbutyl acetate | 1125 | 1120 | Fruity, banana | AF | 72,6±1,8a | 24,4±5,6b | 9,5±1,3b | 76,3±11,8a | 16,0±3,6b |

| FS | 75,2±2,9a | 37,2±9,1ab | 33,2±36,3ab | 39.9±13ab | 18,6±9,4b | ||||

| Benzyl acetate | 1720 | 1714 | Sweet, floral, fruity | AF | 1,4±0,2a | 0,8±0,2a | 1,7±1,2a | 3,4±2,3a | 0,5±0,1a |

| FS | 2,8±1,1a | 1,8±1,5a | 2,5±0,4a | 1,5±0,8a | 1,8±1,5a | ||||

| 2-Methylpropanal | 819 | 823 | Chocolate | AF | 0,5±0,1c | 2,1±0,2a | 1,5±0,1ab | 1,3±0,3abc | 0,9±0,7bc |

| FS | 2,5±0,3ab | 3,1±1,3a | 0,9±0,5b | 1,5±0,6ab | 1,1±0b | ||||

| 2-Methylbutanal | 914 | 872 | Cocoa, chocolate, almond | AF | 8,2±9,9b | 1,5±1,1b | 3,7±3,3b | 65,3±3,3a | 2,4±0,1b |

| FS | 3,2±1,3a | 1,8±1a | 1,7±0,6a | 26,3±9,7a | 1,7±0,2a | ||||

| 3-Methylbutanal | 918 | 876 | Cocoa, chocolate | AF | 1,4±0,2b | 1,1±0,3bc | 1,1±0,2bc | 2,0±0,1a | 0,8±0,1c |

| FS | 1,6±0,8a | 0,94±0,1a | 1,4±0,3a | 0,7±0,3a | 1,3±0,1a | ||||

| Benzyl alcohol | 1870 | 1878 | Floral, pink, phenolic | AF | 3,9±1,6a | 2,7±0,2a | 4,6±2,7a | 5,7±2,5a | 3,2±0,1a |

| FS | 5,6±1,1a | 5,1±0,9a | 5,1±0,6a | 3,2±1,2a | 6,4±3,1a | ||||

| 2-Phenylethanol | 1907 | 1907.8 | Floral, Flowery | AF | 45,0±21,2a | 65±2,1a | 23,7±12,6a | 75,4±54,3a | 40,6±6,8a |

| FS | 28,8±13,8b | 102,9±2,1a | 19,0±2,7b | 22,7±8,2b | 29,0±6,9b | ||||

| Acetoin | 1285 | 1305 | Creamy, buttery | AF | 30,1±9,6b | 34,4±11,2b | 93,1±36,4a | 57,3±4,9ab | 33,3±19,2b |

| FS | 57,4±27,2bc | 25,6±6,9c | 99,3±4,3ab | 116,5±7,6a | 71,5±22,4b | ||||

| 2-Acetoxybutan-3-one | 1378 | 1405 | Sweet, creamy, buttery | AF | 1,9±1,3b | 2,5±1,1b | 14,4±9,1a | 6,1±2,1ab | 1,1±0,7b |

| FS | 2,7±1,4c | 1,2±0,9c | 19,3±0,2a | 10,4±4,2b | 3,7±3,1c | ||||

| Acetophenone | 1647 | 1624 | Flowery, sweet | AF | 5,2±0,4a | 6,7±1,9a | 4,8±0,9a | 4,4±1,3a | 3,7±1,3a |

| FS | 4,8±0,1b | 6,7±1a | 4,4±0,5b | 3,4±0,5b | 3,53±0,5b | ||||

| 2,3,5-Trimethylpyrazine | 1402 | 1407 | Cocoa, roasted, baked, Peanut, roasted | AF | 2,06±0,7bc | 1,1±0,5c | 4,3±1,1a | 3,5±1,1ab | 2,2±0,4bc |

| FS | 2,3±1,1bc | 1,1±0,6c | 4,1±0,2a | 2,7±0,7ab | 4±0,3a | ||||

| Tetramethylpyrazine | 1469 | 1468 | Milk coffee, roasted, chocolate | AF | 14,1±5,9bc | 8,4±6,7c | 66,2±27,4a | 53,4±19,5ab | 18,5±12,2bc |

| FS | 14,68±7,8bc | 3,61±2,3c | 64,8±15,9ab | 78,47±40,1a | 60,2±18ab | ||||

| Cis-Linalool oxid | 1444 | 1473.3 | Sweet, floral, earthy, woody | AF | 1,4±0,2a | 1,05±0ab | 0,7±0,2b | 1,3±0,5ab | 0,6±0,1b |

| FS | 1,45±0,2a | 1,2±0,2ab | 0,63±0c | 1,2±0,3ab | 0,8±0,1bc | ||||

| Linalool | 1547 | 1548.4 | Floral, rose, sweet, green, citrus | AF | 2,4±0,4a | 2,4±1a | 0,8±0,5b | 1,1±0,5ab | 0,3±0,1b |

| FS | 2,2±0,2ab | 3,4±1a | 0,5±0,1c | 1,00±0,2bc | 0,5±0,2c | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).