1. Introduction

The use of antimicrobials in food animal production has a history over 80 years, with the first use dating back to the 1940s [

1]. Antimicrobials played a significant role in enhancing animal productivity and meeting the growing food demand for rapidly increasing global population [

2]. However, their overuse has created a major global health crisis: antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Operating under the "One Health" framework, AMR not only limits treatment options for veterinarians and compromises animal health, but it also poses a direct threat to human health through the food chain. With research suggesting that a 10% increase in animal antimicrobial use can lead to a 0.3% increase in human AMR [

3], it’s clear that curbing antimicrobial usage (AMU) in food animals is a crucial step toward protecting both animal and human health.

To address these concerns, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has implemented various policies aimed at regulating antimicrobials use in food animals. Notably, Guidance for Industry (GFI) #213, which took effect on January 1, 2017, prohibited the use of medically important antimicrobials for growth promotion purposes [

4]. This guidance initially led to a significant decline in total antimicrobials sales, but the downward trend began slowdown in 2018. Among food animal industry, the antimicrobial usage status in swine industry concerning the public the most. According to the FDA, in 2023, swine accounted for the highest percentage (44%) of medically important antimicrobial sales among all food-producing animals [

5]. This concerning trend underscores the urgent need for promoting the judicious use of antimicrobials in the swine industry to mitigate the risk of AMR.

A significant driver of AMU in swine is the use of antimicrobials to treat secondary bacterial infections that often follow viral diseases. For example, viruses can damage the respiratory and intestinal barriers, making pigs more susceptible to bacterial infections. Studies have shown that in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS)-positive herds, antimicrobial use increases significantly by 379% in nursery pigs and 274% in pigs approaching market weight [

6]. Vaccines offer a promising solution by reducing the burden of viral diseases and, in turn, the reliance on antimicrobials. While an ideal vaccine should be effective, safe, affordable, and readily available, many existing vaccines fall short of these expectations. Given their crucial role in advising producers, understanding veterinarians’ perspectives on the challenges and opportunities of current viral vaccines is essential. This study aims to address that knowledge gap by gathering insights from U.S. swine veterinarians. By exploring their perspectives on the prioritization of swine diseases and the limitations of existing viral vaccines—including concerns about safety, efficacy, availability, and cost—we can better identify opportunities for improvement. This information will help guide the development of improved vaccines that protect animal health, reduce the industry’s AMU, and help mitigate the global threat of antimicrobial resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

The study materials and research protocol were approved by the Kansas State University Research Compliance Office (Protocol # IRB-12219) prior to project started. All participants were requested to sign consent at the beginning of the survey, and anonymity was assured throughout. Participants had the option to provide their email address voluntarily at the end of the survey to receive a $25 gift card as a token of appreciation.

2.2. Survey Design and Dissemination

The study consists of two phases to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. In the first phase, an online survey was distributed to collect quantitative data. At the conclusion of the survey, participants were asked if they would be willing to participate in a follow-up interview. In the second phase, participants who expressed interest were invited to one-on-one semi-structured interviews to gather qualitative insights.

The swine veterinarians practiced in the United States were the target population for this survey. Our survey was implemented using the Qualtrics software, Copyright© 2024 Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA. Available at

http://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 10th August 2024), access with license through the Kansas State University (KSU), KS, USA. The survey invitations to participate were distributed via personalized emails to American Association of Swine Veterinarians (AASV) membership lists (n= 200) between June and July 2024. A reminder email was sent one week after the initial invitation. The survey remained open for a total of eight weeks, concluding in August 2024.

The questionnaire was designed based on insights from the literature and the expertise of authors specializing in swine veterinary medicine and agricultural economics. The questionnaire used the branching logic format, allowing the survey adapted dynamically to participants’ responses by skipping irrelevant questions (e.g., if the participants didn’t identify Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) as a swine disease that urgently need a better vaccine, they will not receive the following sub-questions designed for PRRS). Therefore, individual participants answered a variable number of questions. On average, the survey took 40 minutes to complete (after excluding one outlier caused by prolonged survey inactivity.)

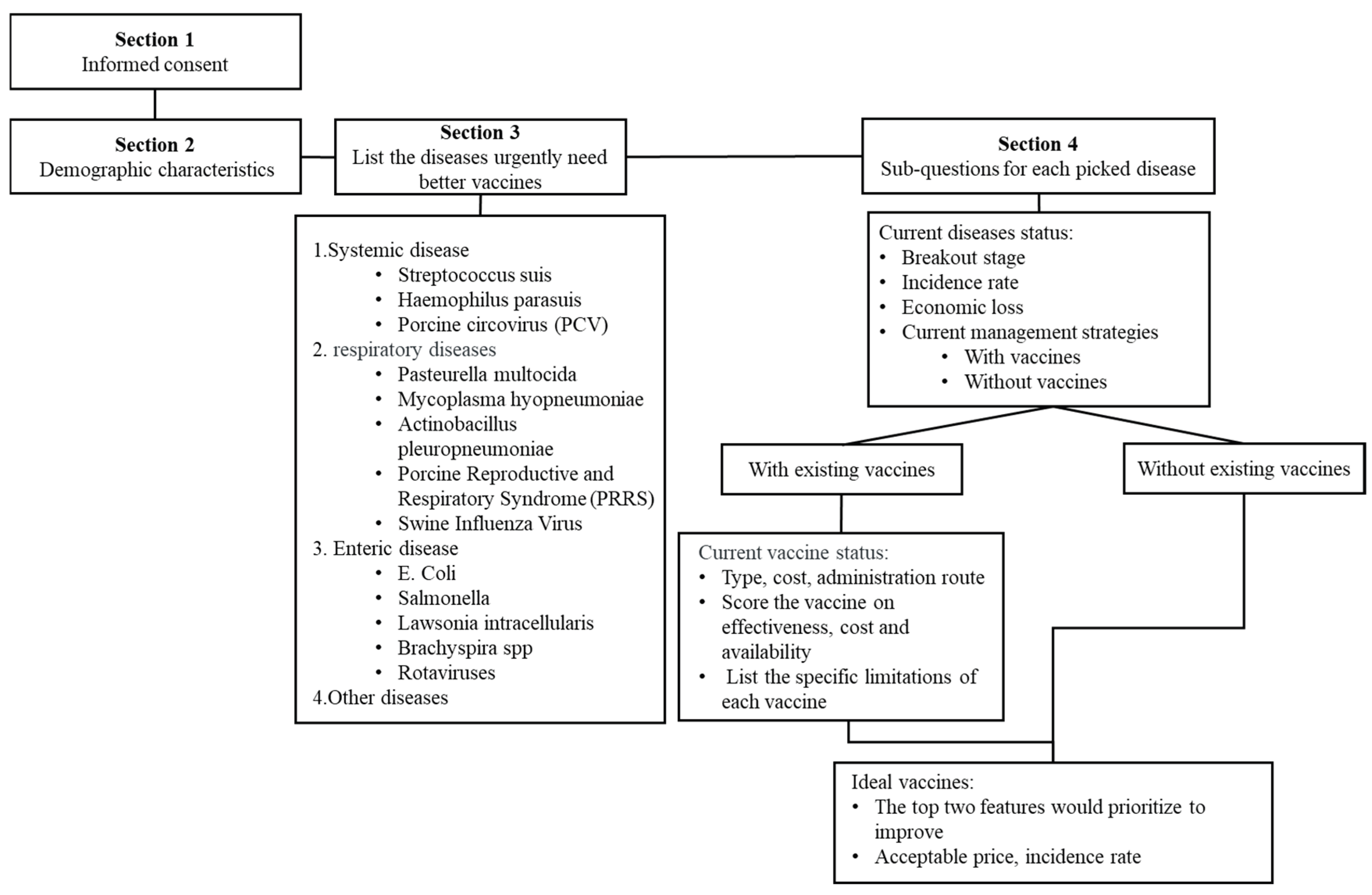

The survey consisted of four main sections (

Figure 1): (i) Informed consent: Participants were required to read and agree to the informed consent form before proceeding. (ii) Demographic characteristics and general practice information: This section included three questions on years of practice, the number of pigs served, and the geographic region of practice. (iii) Swine diseases in urgent need of improved vaccines: This section included four questions focusing on systemic, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and other diseases categories, covering a total of 13 common swine diseases. (iv) Detailed question for each selected disease: For each disease selected by participants, 32 structured questions were presented covering the following areas: (a) Current disease status (e.g., production stages affected, incidence rates, and economic impact etc.). (b) Current management strategies (based on participants answers, distinguishing disease into with existing vaccines and those without, two categories). (c) For the diseases with existing vaccines, participants graded the vaccine on three aspects including efficacy, availability, and cost, on a scale of 1 to 5 (where 1 indicated “not ideal” and 5 indicated “extremely ideal”). Participants identified specific limitations contributing to the challenges of the current vaccine on adverse effects and the aspects that graded lower than five. Then identified limitations formed a pool of current vaccine challenges. Participants selected the top two challenges from the pool that they believed should be prioritized for improvement. Based on these improvements, participants were also asked to indicate the desired incidence rate and the acceptable cost increase for the improved vaccine. (d) For the disease without existing vaccine, participants identified the top two features they desired in a future vaccine. Similarly, participants were asked to indicate the desired incidence rate and the acceptable cost for the future vaccine.

2.3. Interview

Semi-structured interviews were tailored for each participant based on their survey responses. Between June and July 2024, five swine veterinarians participated in interviews, four conducted via Zoom and one in person. All interviews were hosted and documented by the first author. The interviews were all audio recorded with participants’ consent. Recordings were used only to ensure the accuracy of notes, and access to recordings was restricted to the first author.

Each interview lasted approximately 40 minutes with an average of eight open-ended questions. The interview focused on following 7 key areas: (i) The relationship between vaccines and antibiotics in swine health management; (ii) Priority diseases for vaccine development and disease control strategies; (iii) Economic considerations of vaccine adoption; (iv) Regulatory, educational, and logistical challenges in vaccine implementation; (v) Prescription platform vaccines and custom vaccine development; (vi) Future trends in vaccine development and antimicrobial use reduction; (vii) Challenges in disease surveillance and data collection. These interviews aimed to further understand U.S. swine veterinarians’ awareness and attitudes toward reducing antimicrobials use through vaccine adoption.

2.4. Data and Statistical Analysis

For the survey data, we first exported results from Qualtrics into Microsoft Excel (Version 2509 Build 16.0.19231.20138) for initial organization and summarization. Subsequently, these data were imported into GraphPad Prism (version 10) for further statistical analysis and visualization. The figure “Regional distribution of all respondents” was generated by Power BI (Version 2.131.901.0), while the rest of the figures were visualized using GraphPad Prism 10. We used a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction to compare current and ideal vaccine morbidity rates. The comparison of current and ideal vaccine prices was performed using a two-tailed, unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. All figures use a 95% confidence interval to measure the significance between groups. All significant results (P-value <0.05) were indicated with asterisks in the figures.

For interviews, recordings were transcribed verbatim and anonymized. The transcripts were reviewed multiple times to ensure accuracy and familiarity with the content. Key points from the interviews were grouped into major themes that consistently appeared across multiple participants. These themes encompassed shared perspectives on vaccine effectiveness, economic factors, regulatory and logistical challenges, and future vaccine development priorities. Responses were also compared to identify both common viewpoints and individual differences. To provide a more comprehensive understanding of swine veterinarians’ perspectives on using vaccines as an alternative to antimicrobials, we integrated our interview findings with the survey data.

A five-point Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) was adopted to assess multiple dimensions of vaccine evaluation, including effectiveness, cost, and availability. For effectiveness, a score of 1 indicated not effective at all and 5 indicated extremely effective. For cost, a score of 1 represented very cheap and 5 represented very expensive. For availability, a score of 1 indicated extremely difficult to obtain and 5 indicated extremely easy to obtain. To minimize potential misunderstanding of the scale, each numeric option was accompanied by descriptive text in the questionnaire. Responses were treated as ordinal data but summarized as mean values with 95% confidence intervals for comparative purposes. This structured NRS approach ensured consistency and comparability across respondents’ subjective assessments.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

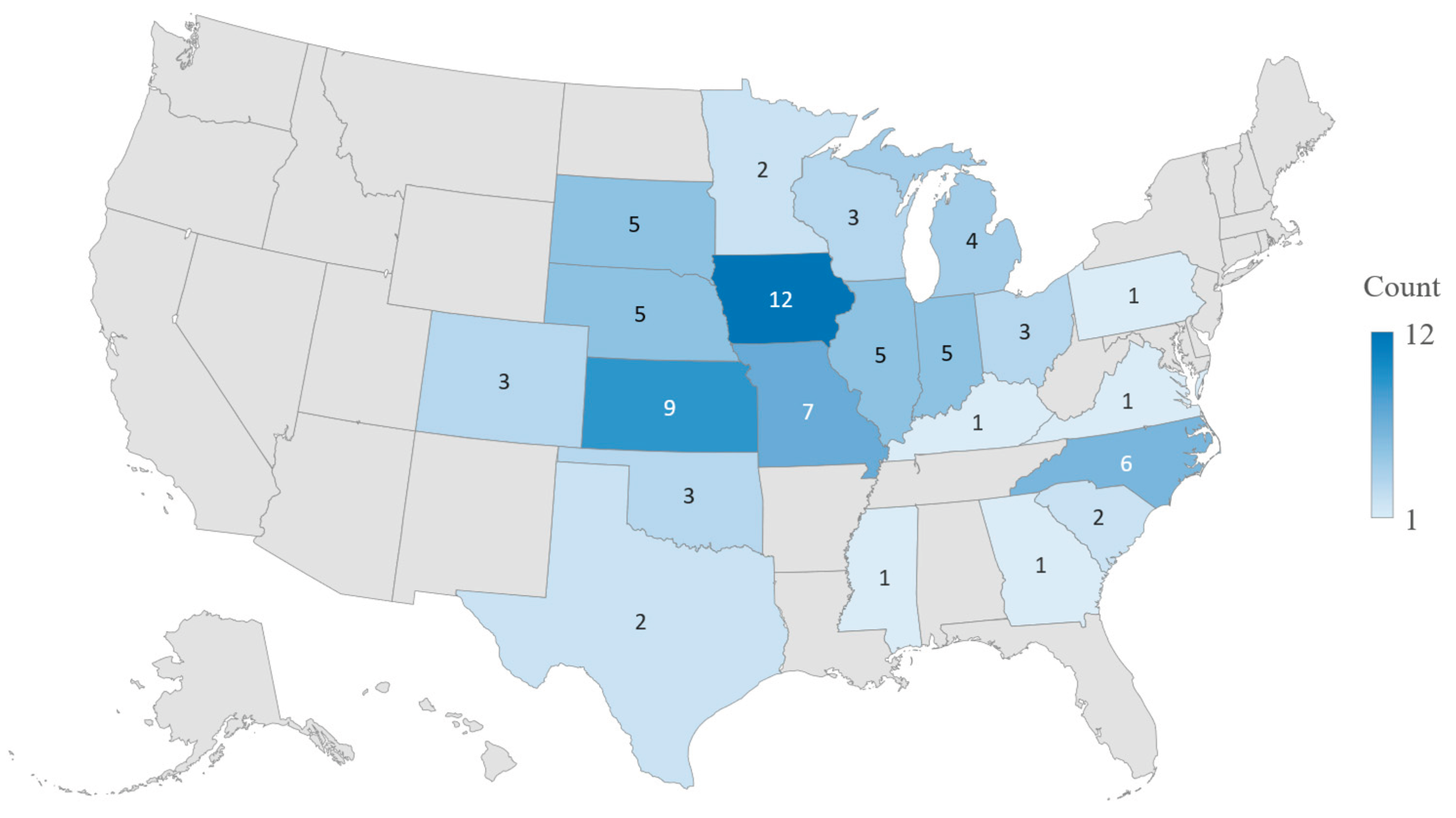

A total of 46 responses were received, with a response rate of 23%. Of these, 27 responses were excluded from the final statistical analysis due to less than 80% complete or the participants stated that they were not directly responsible for swine medical treatment. The final statistical analysis included 19 surveys, resulting in an effective response rate of 9.5%. The 19 swine veterinarians included in the analysis had an average of 24.7 years of practice experience, and more than 78% of them had 15 or more years of swine medicine experience. On average, 482,736 pigs (including sows, growing and finishing pigs) were under direct or joint responsibility of each swine veterinarian at the time of the survey. As shown in

Figure 2, the participants practiced across over 20 U.S. states, and 73% were located in Midwestern region, which is known for high concentration of pig populations.

3.2. Prioritization of Swine Diseases in Need of Better Vaccines

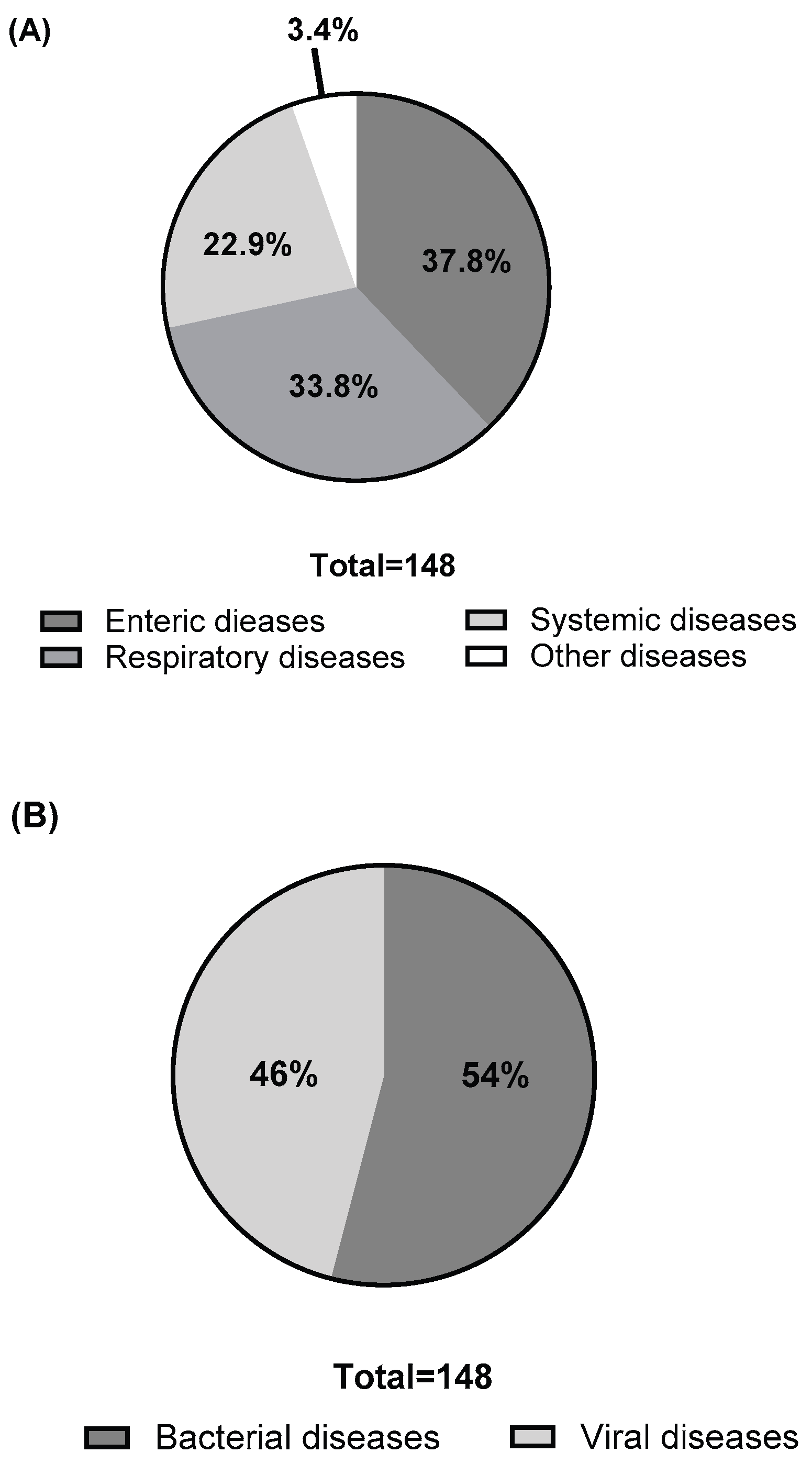

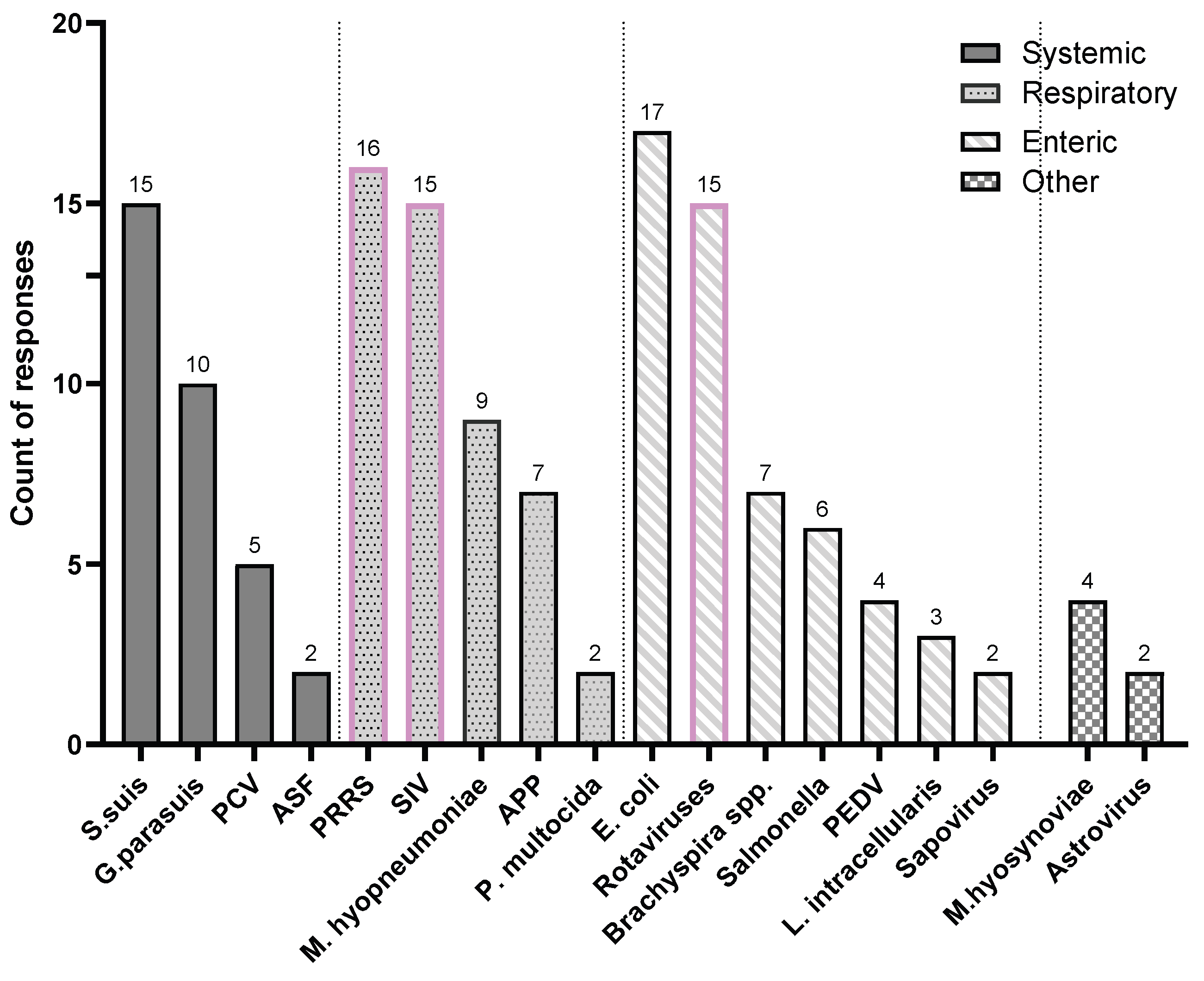

Participants reported a total of 25 swine diseases that are in urgent need of better vaccines. As shown in

Figure 3, these diseases were mentioned 148 times collectively. Based on affected organ system, enteric diseases were the most frequently reported (56 mentions, 37.8% of total), followed by respiratory diseases (50 mentions, 33.8%), systemic diseases (34 mentions, 22.9%), and other diseases (8 mentions, 3.4%). When categorized by pathogen type, viral diseases were mentioned 68 times, making up 45.3% of the total.

Our findings on the prioritization of swine viral diseases are highlighted in

Figure 4. The data reveals a strong consensus among veterinarians regarding which diseases urgently need improved vaccines. PRRS was the most frequently cited disease, with 84.2% fof veterinarians (n=16) identifying it as a top priority. Swine influenza (SIV) and rotaviral enteritis followed closely, each mentioned by 78.9% of the respondents (n=15). Of all the viral diseases discussed, PRRS, SIV, and rotaviral enteritis were identified as the top three diseases most urgently in need of improved vaccine solutions.

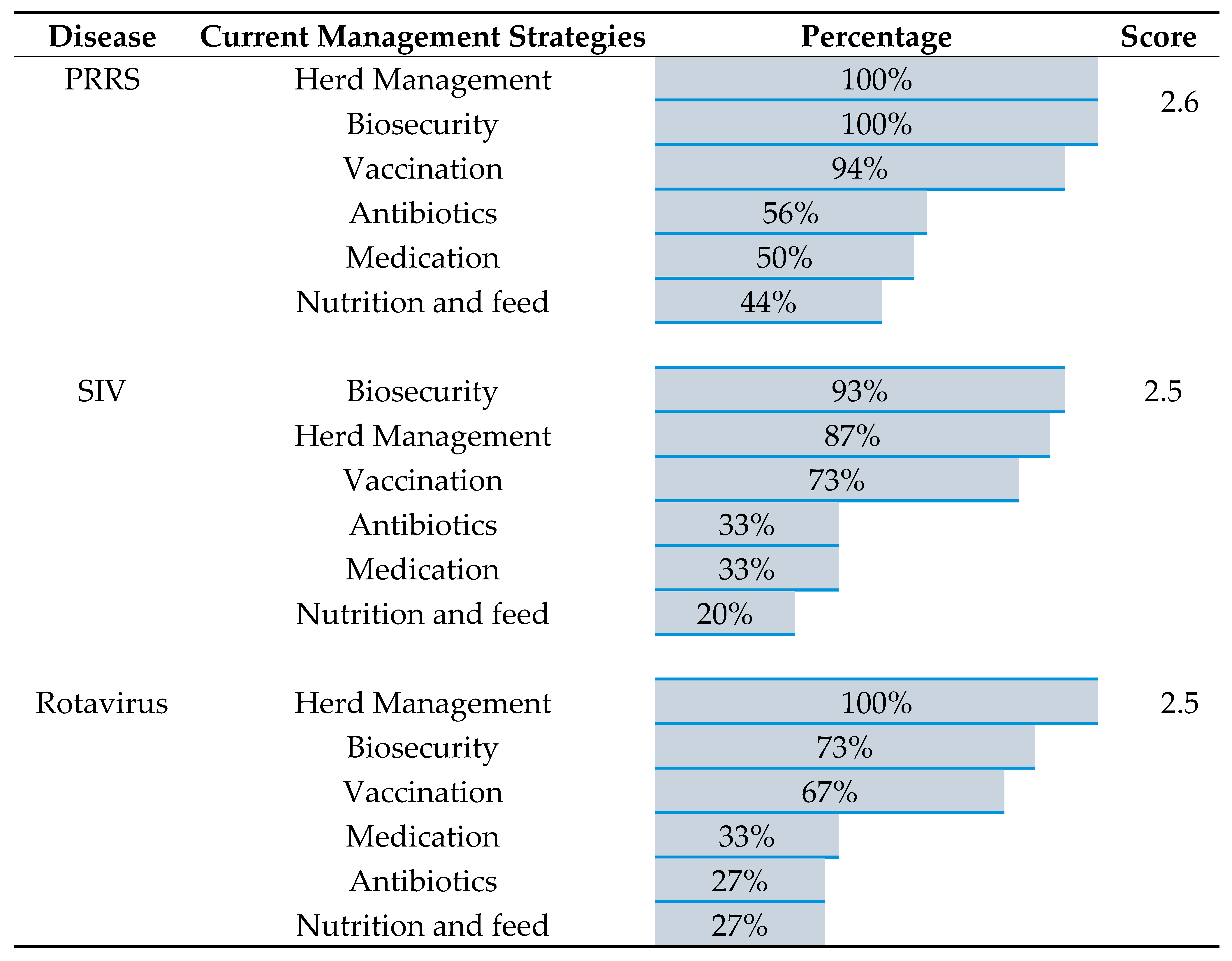

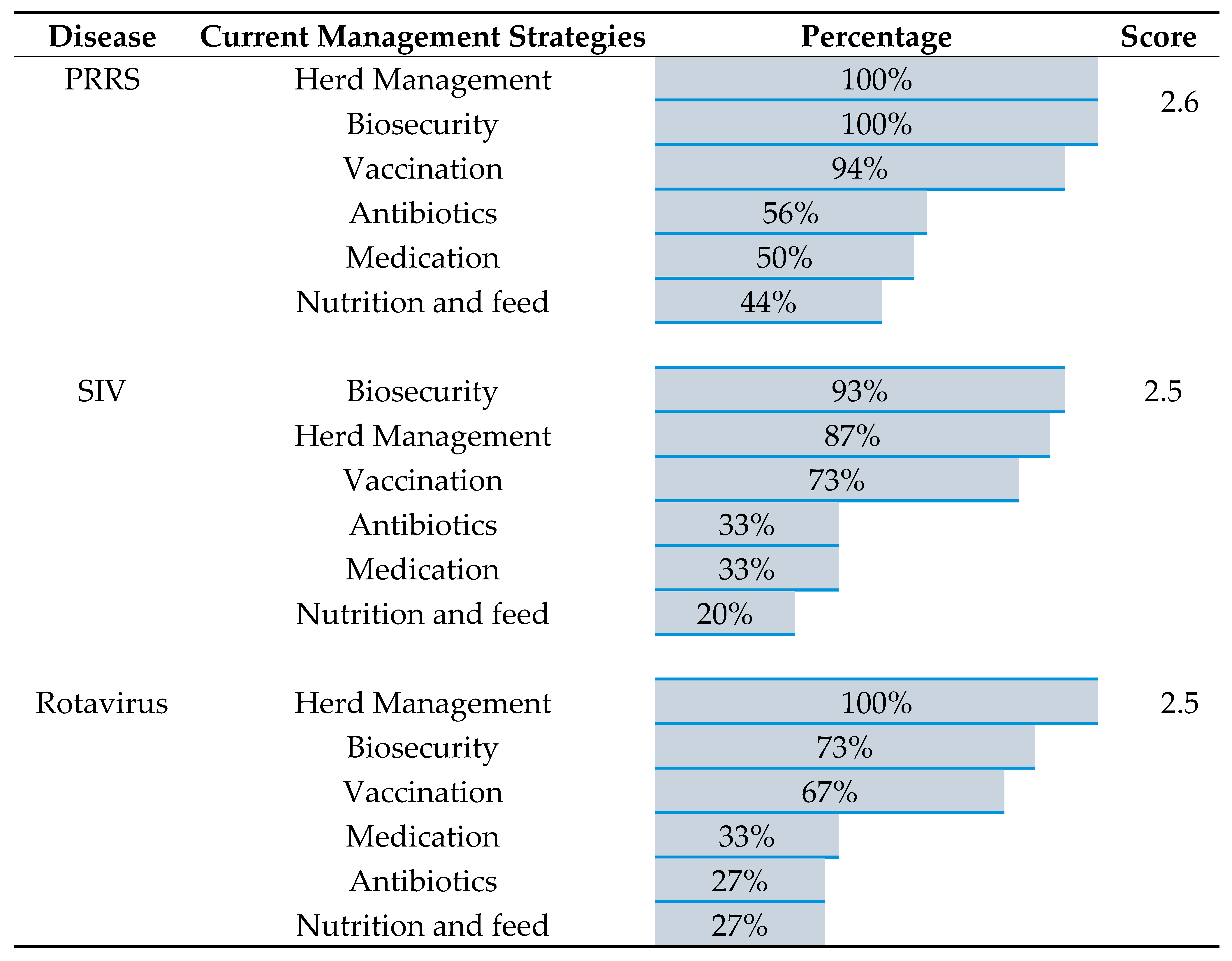

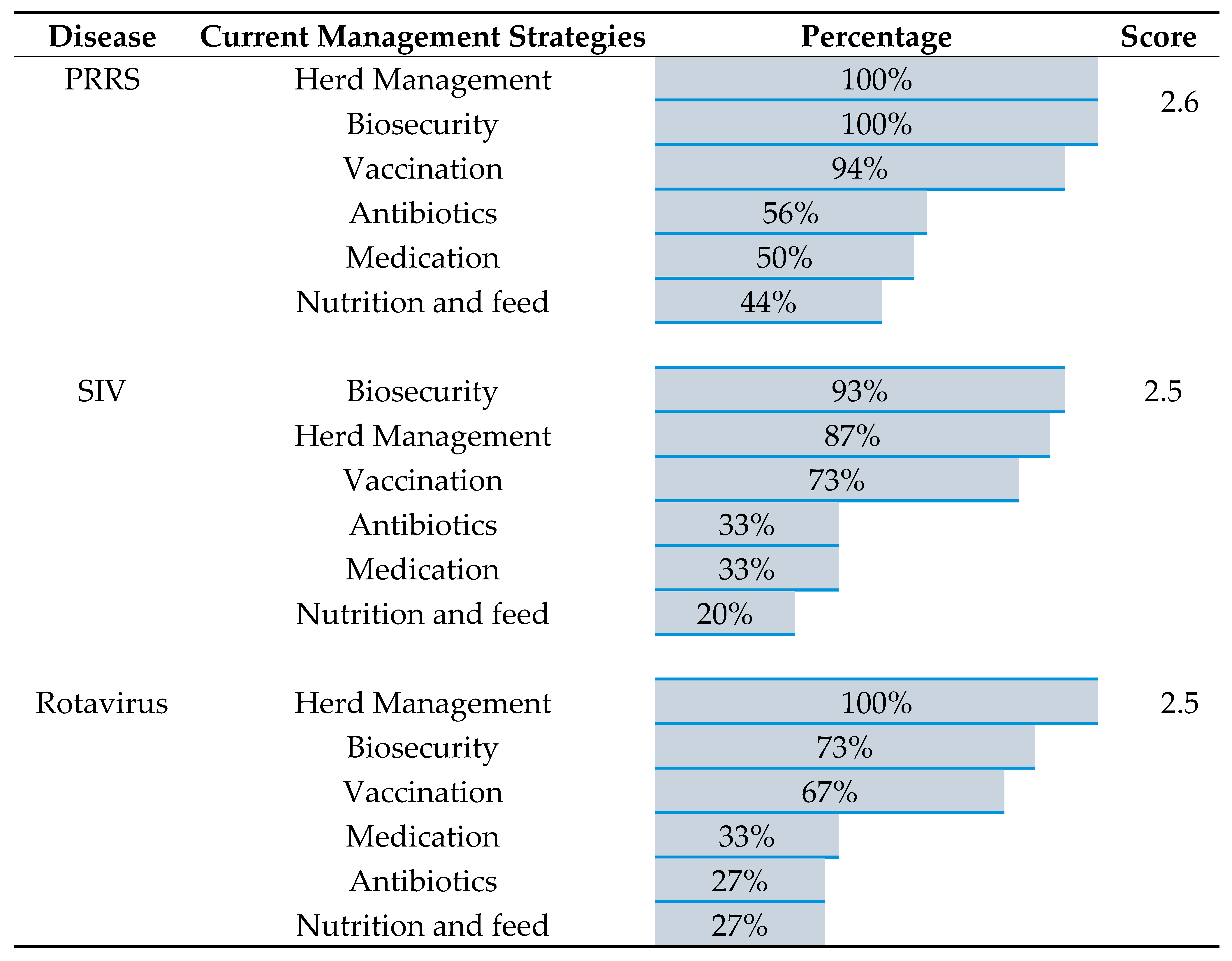

3.3. Current Management Strategies for the Top Swine Viral Diseases

For the top three viral diseases, PRRS, SIV, and rotaviral enteritis, all participants reported using a combination of herd management, biosecurity measures, and vaccination as their primary disease management strategies. Additionally, over 25% of veterinarians noted using antimicrobials to address secondary bacterial complications that arise with these infections. Of the three, PRRS had the highest proportion of veterinarians relying on vaccines as a key management strategy (94%), as well as the highest proportion of using antimicrobial to control the secondary bacterial infections (56%). Notably, nearly all veterinarians were dissatisfaction with the effectiveness of the current management strategies. On a 5-point scale, the average effectiveness score for each disease was approximately 2.5, placing them between "slightly effective" and "moderately effective." (

Table 1).

3.4. Challenges of Current Vaccines for the Top Swine Viral Diseases

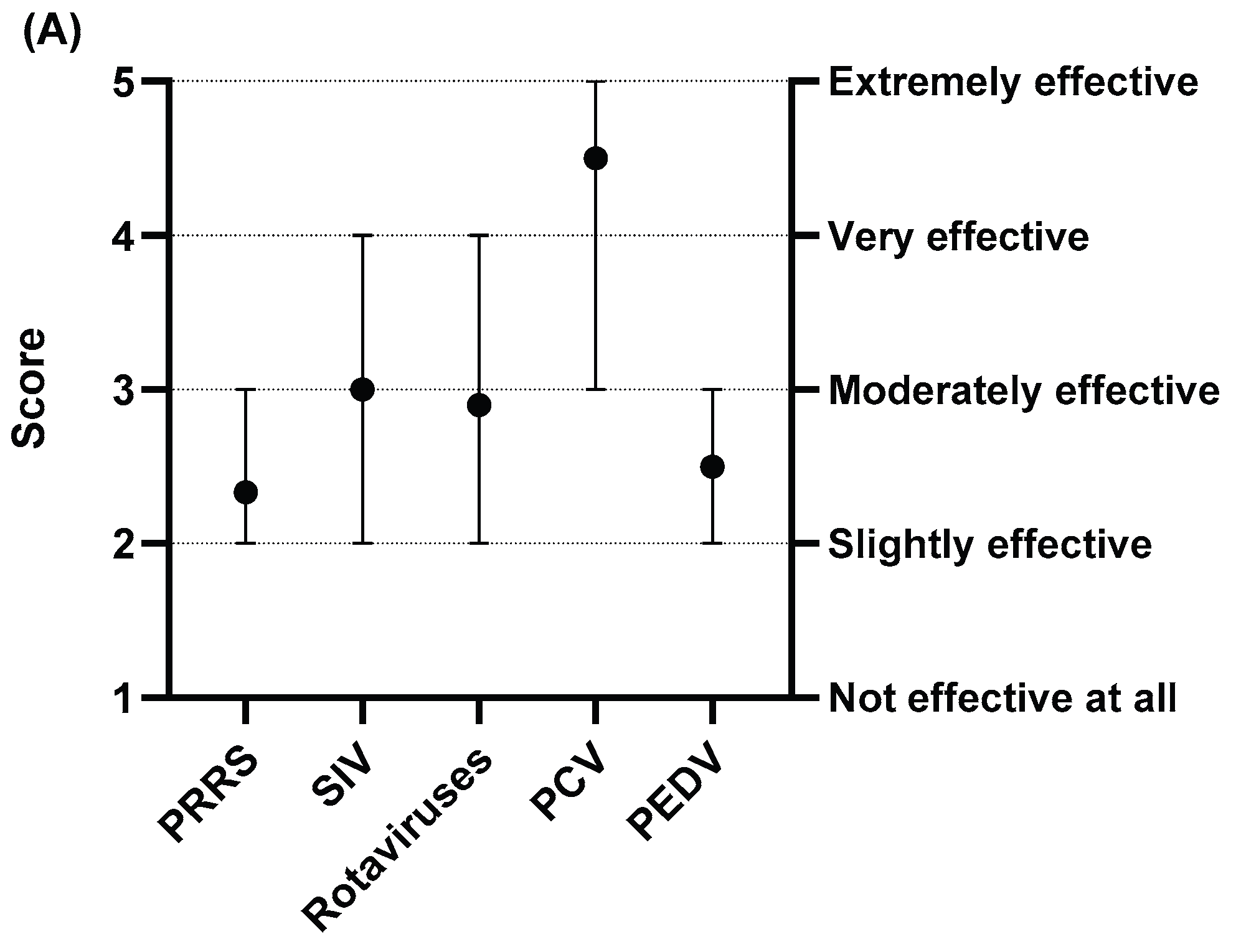

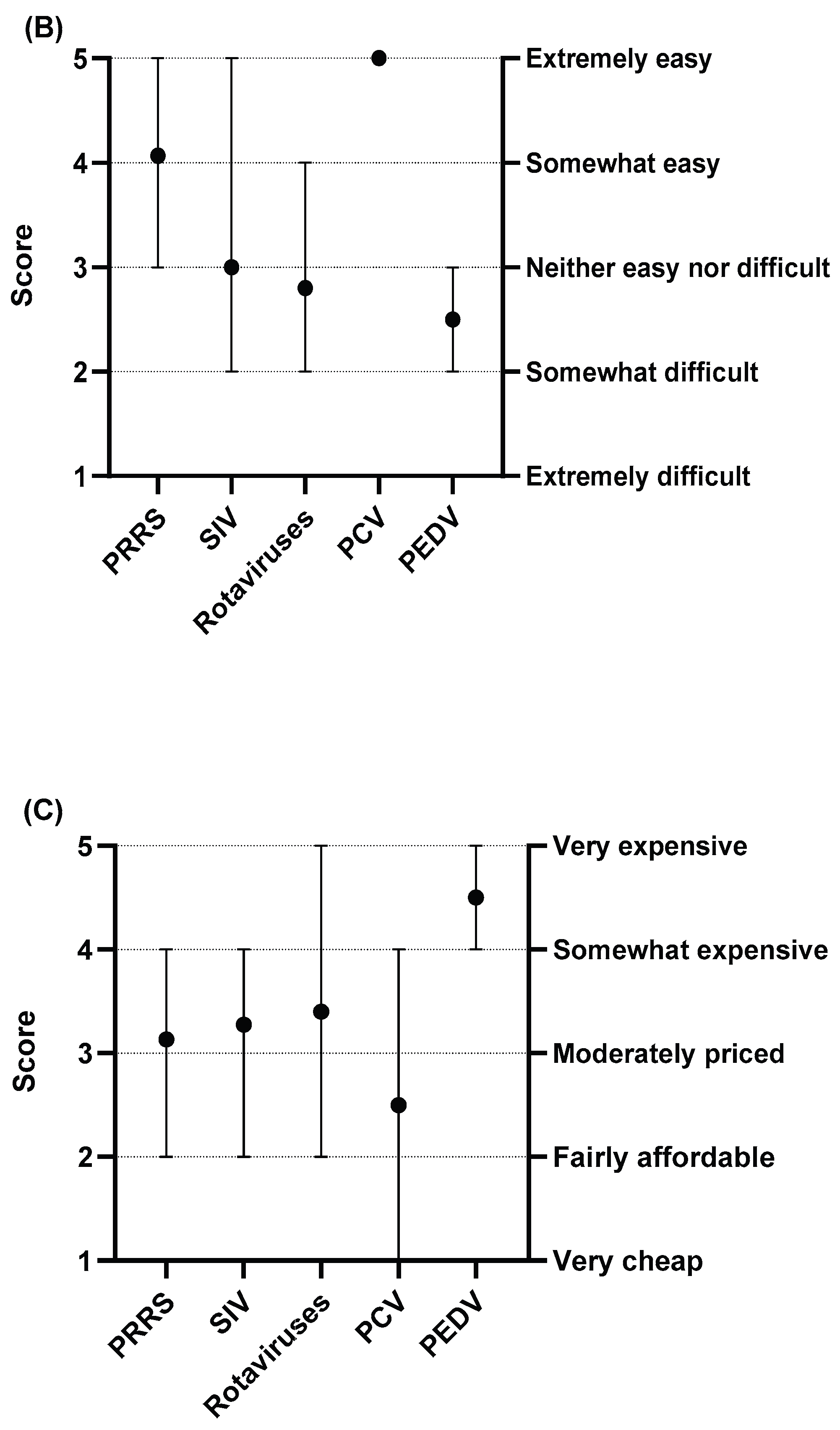

Vaccines are a critical tool in managing swine viral diseases, but our survey shows they have significant limitations.

Figure 5 illustrates the average scores veterinarians assigned to the effectiveness, availability, and cost of current vaccines for PRRS, SIV, rotavirus, porcine circovirus (PCV), and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV). For effectiveness, only the PCV vaccine scored highly, rated between "extremely effective" and "very effective." In contrast, vaccines for PRRS, SIV, rotavirus, and PEDV were all rated as only "slightly" to "moderately" effective (

Figure 5A). For availability, while PRRS and PCV vaccines were generally rated as "somewhat easy" to acquire, those for SIV, rotavirus, and PEDV were perceived as less available, falling in the range of "neither easy nor difficult" to "somewhat difficult" (

Figure 5B). For cost, PCV was the only vaccine considered relatively affordable, rated between "fairly affordable" and "moderately priced." The other four vaccines were all rated on the more expensive side, between "moderately priced" and "very expensive" (

Figure 5C). These scores highlight key areas for improvement. The following sections explore the specific limitations that contribute to these challenges in more detail.

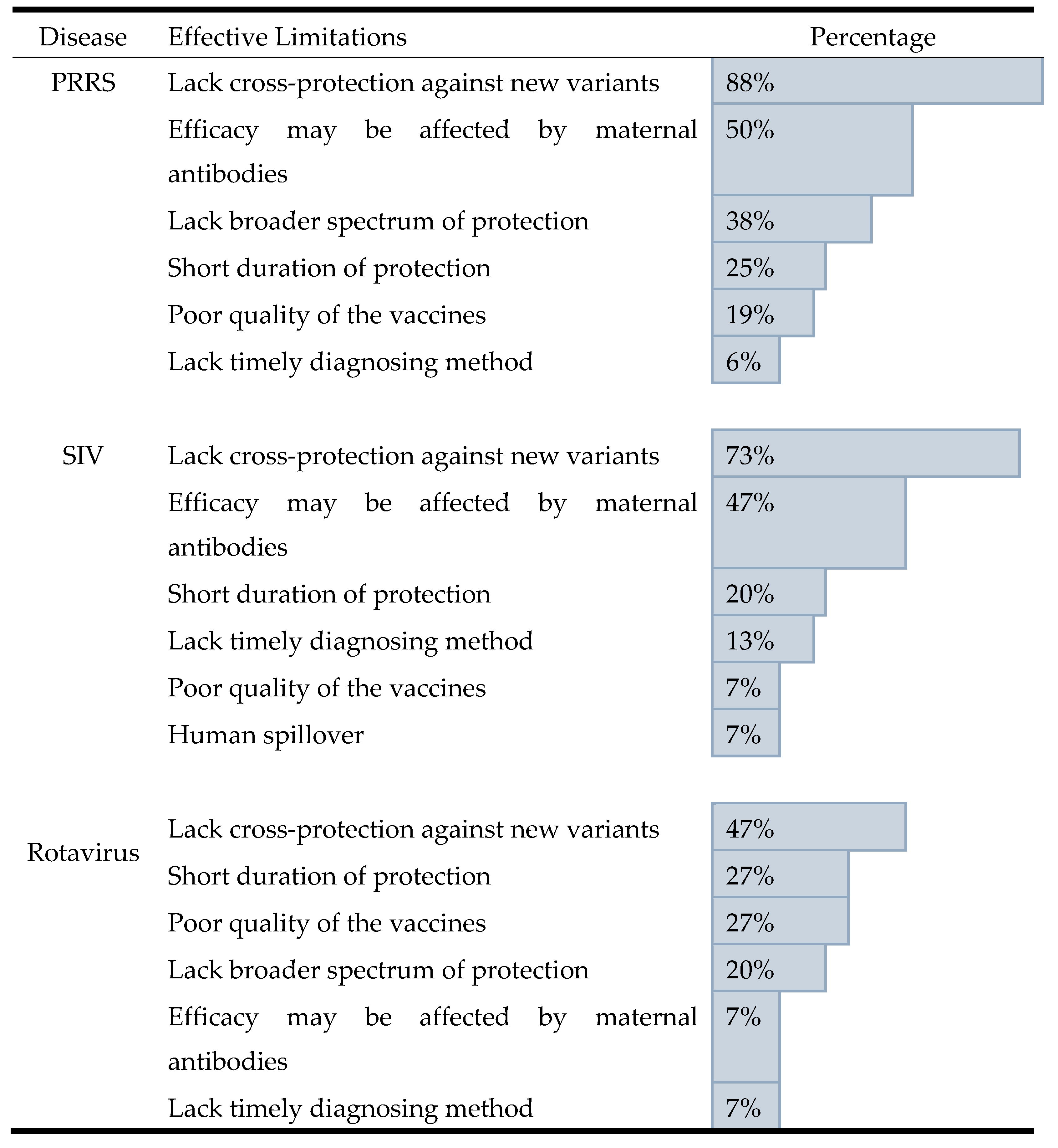

3.4.1. Specific Limitations that Contribute to Challenges on Effectiveness of Swine Viral Vaccines

When evaluating vaccine effectiveness, veterinarians rated the SIV (mean score = 3.0) and rotavirus (mean score = 2.9) vaccines as "moderately effective." In contrast, the PRRS vaccine received a significantly lower average score of 2.3, placing it in the "slightly effective" category (

Figure 5A). The most common challenge across all three diseases was a lack of cross-protection against new viral variants. This was cited by 88% of respondents for PRRS, 73% for SIV, and 47% for rotavirus. Beyond this shared issue, other challenges were disease-specific. For PRRS and SIV, the second most common challenge was the negative effect of maternal antibodies on vaccine efficacy, cited by 50% and 47% of veterinarians, respectively. For rotavirus, the second most common concerns were a short duration of protection and poor vaccine quality, both cited by 27% of respondents (

Table 2).

3.4.2. Specific Limitations That Contribute to Challenges on Cost and Availability of Swine Viral Vaccines

Veterinarians reported that PRRS, SIV, and rotavirus infections lead to significant economic losses, estimated at

$4.00,

$2.00, and

$0.89 per head, respectively. Despite these high costs, veterinarians rated all three current vaccines as moderately priced, with mean scores of 3.1 for PRRS, 3.2 for SIV, and 3.4 for rotavirus on a 5-point scale (

Figure 5C). Veterinarians further provided their insights on specific costs of vaccines for the 3 top swine viral diseases. For PRRS vaccines, the cost per dose ranges from

$0.60 to

$2.00, with an average of

$1.20 per dose and an average annual cost of

$1.80 per head. For SIV vaccines, the cost per dose ranges from

$0.50 to

$1.30, with an average of

$0.80 per dose and an average annual cost of

$1.80 per head. For rotavirus vaccines, the cost per dose ranges from

$0.40 to

$1.50, with an average of

$0.90 per dose and an average annual cost of

$1.70 per head. Veterinarians feel that the vaccines’ limited effectiveness prevents them from providing a significant economic benefit. Since the vaccines don’t adequately reduce disease incidence, producers are still forced to use costly antimicrobial treatments. This undermines the overall economic viability of vaccination and highlights the critical need for future improvements in vaccine effectiveness and quality.

When looking at the availability of swine viral vaccines, several key limitations were identified. (i) Limited vaccine administration method: All three vaccines for PRRS, SIV, and rotavirus were primarily administered through the intramuscular (IM) route. Only a small number of veterinarians reported using alternative methods, such as subcutaneous (SQ) for PRRS vaccine, subcutaneous (SQ) and intranasal (IN) for SIV vaccine, and both SQ and oral (PO) for rotavirus vaccine. (ii) Preference of vaccine types: Veterinarians showed a clear preference for commercial vaccines for PRRS. In contrast, autogenous vaccines were more frequently used for SIV and rotavirus (

Table 3). This preference for autogenous vaccines for SIV and rotavirus appears to be a factor in their availability challenges.

For PRRS vaccine, it is rated as "somewhat easy" (mean score = 4.1). The main challenges were difficulties with administration and a shortage of storage. For SIV vaccine, it is rated as "neither easy nor difficult" (mean score = 3). The primary limitations were distribution delays and the high cost of customized autogenous vaccines. For rotavirus vaccine, it is rated as "somewhat difficult" (mean score = 2.8). Similar to SIV, its availability was affected by distribution delays and the high cost of customized autogenous vaccines (

Table 4). These findings suggest that the higher use of autogenous vaccines for SIV and rotavirus is directly linked to the reported challenges of distribution delays and cost.

3.4.3. Specific Limitations That Contribute to Challenges on Safety of Vaccines

While participants reported no safety concerns regarding rotavirus vaccines, several issues were raised concerning the safety of vaccines for PRRS and SIV. The primary safety concerns for PRRS vaccines were related to their potential impact on herd productivity and a risk reverting to virulence. 56% of participants expressed concern that the vaccine could cause a temporary reduction in the productivity of their swine herds. 56% of participants, who feared that the weakened live virus in the vaccine could mutate back into a more harmful, disease-causing form. For SIV vaccines, the main safety concern was tied to adverse physical reactions at the injection site. This was the most commonly reported concern, with 33% of participants noting issues such as swelling, redness, or abscesses at the injection site (

Table 5).

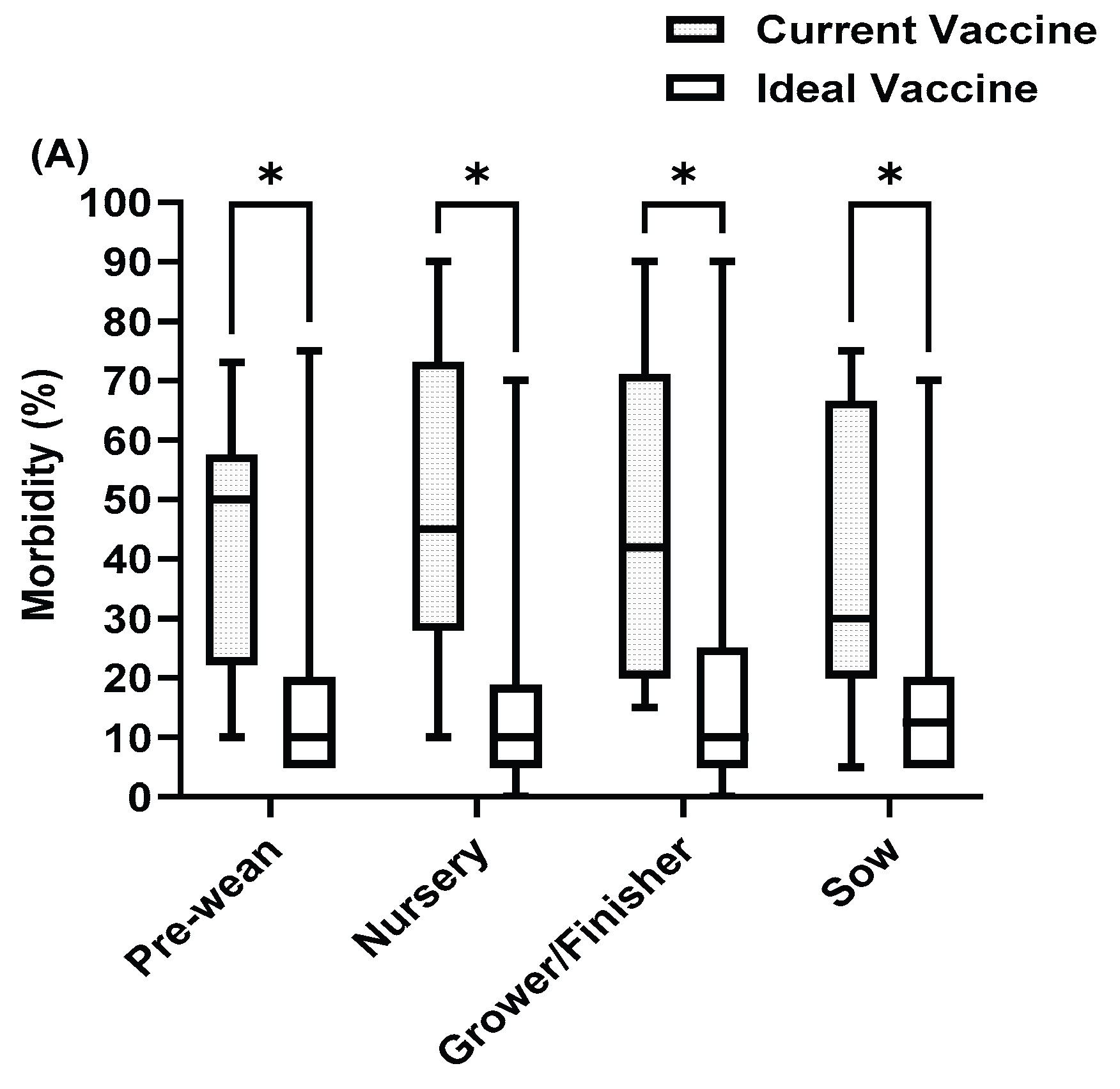

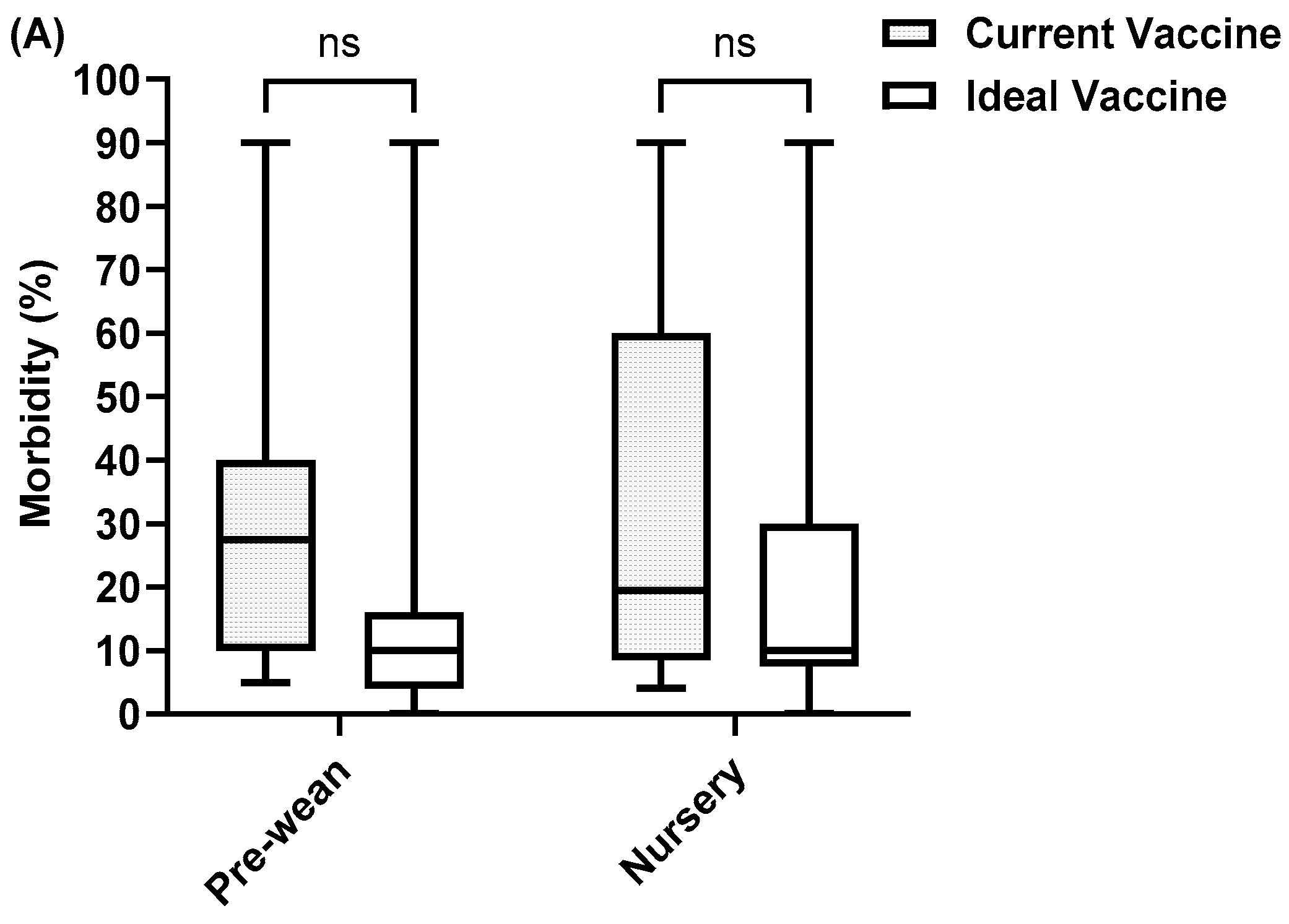

3.5. Future Perspectives and Opportunities for Improved Swine Viral Vaccines

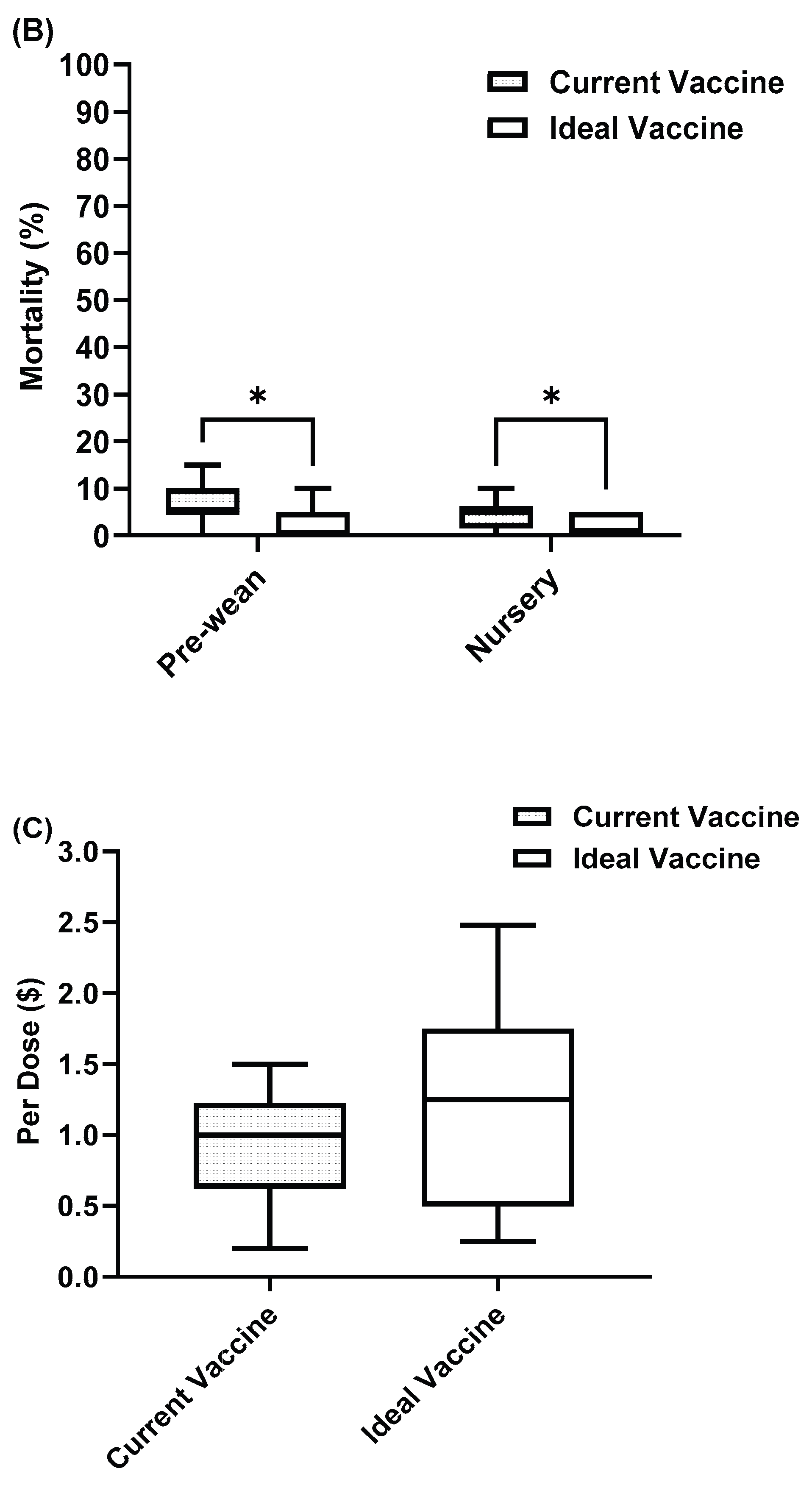

A significant issue shared across all three diseases is a lack of cross-protection. This means the current vaccines don’t provide broad immunity against different strains or types of viruses. As a result, they aren’t as effective as they could be at reducing morbidity and mortality rates (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). To address this, we asked veterinarians to estimate the potential decrease in disease incidence if the main vaccine challenges were overcome. Their responses highlighted a strong belief in the value of improved vaccines and a clear willingness to invest more, despite current economic pressures. Specifically, they would pay 28% more for a better PRRS vaccine, 66.3% more for an improved SIV vaccine, and 35.6% more for a superior rotavirus vaccine. This indicates a strong market demand for more effective and safer swine viral vaccines, even at a higher cost, due to the expected benefits for disease control and overall herd health.

Figure 6.

PRRS current vaccine compared with ideal vaccine in (A) Morbidity (B) Mortality (C) Cost. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

PRRS current vaccine compared with ideal vaccine in (A) Morbidity (B) Mortality (C) Cost. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

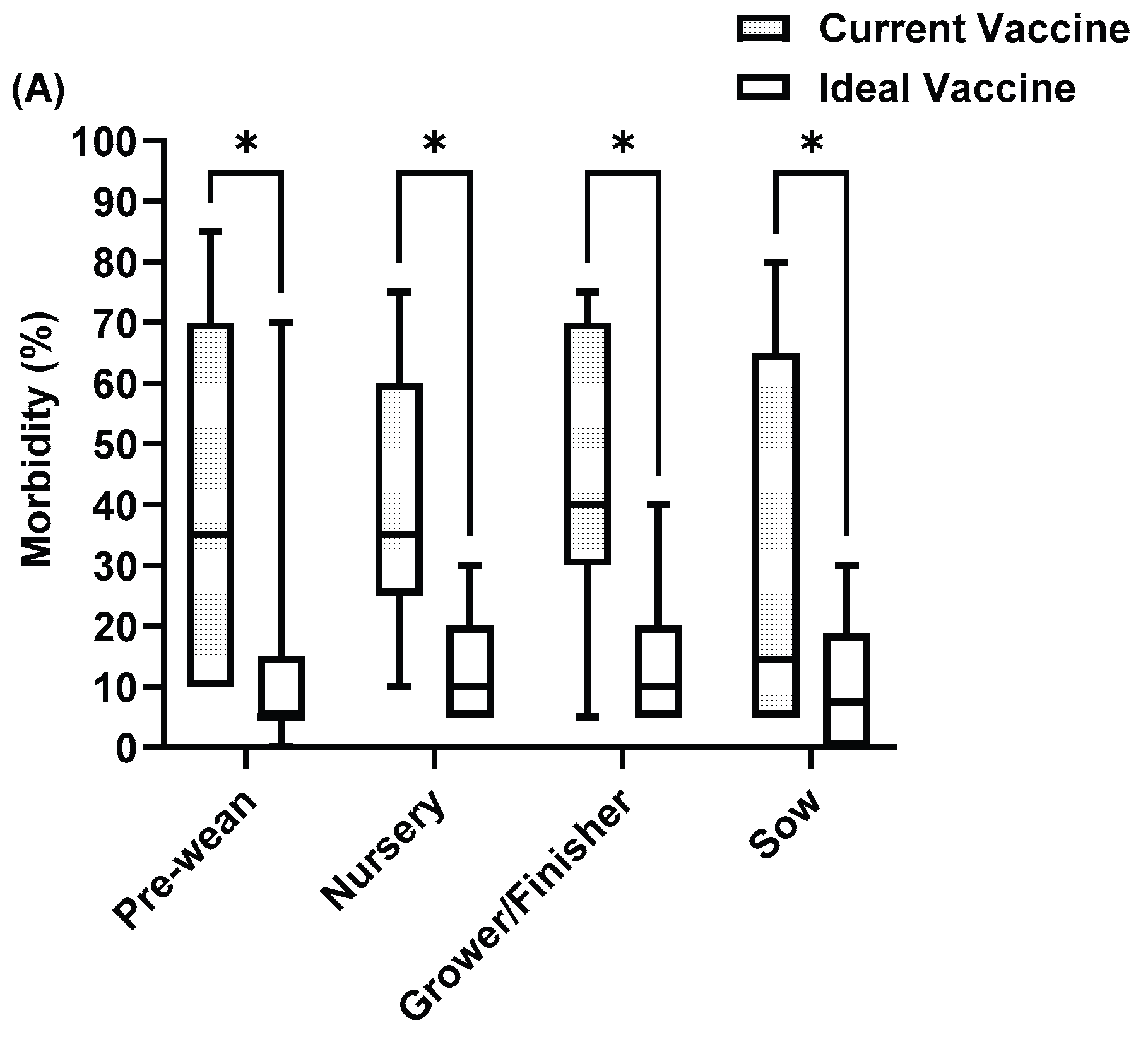

Figure 7.

SIV current vaccine compared with ideal vaccine in (A) Morbidity (B) Mortality (C) Cost. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

SIV current vaccine compared with ideal vaccine in (A) Morbidity (B) Mortality (C) Cost. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

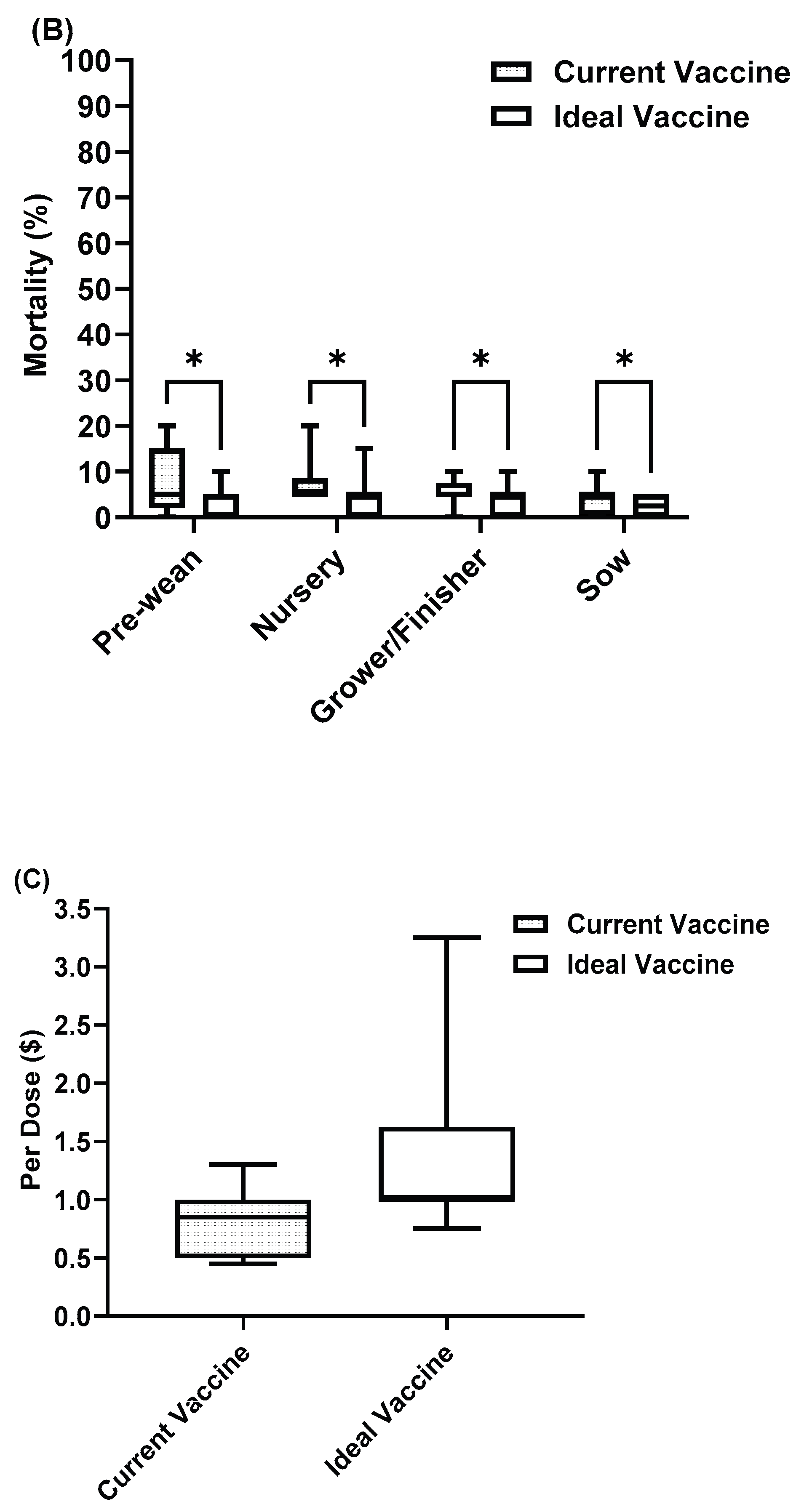

Figure 8.

Rotavirus current vaccine compared with ideal vaccine in (A) Morbidity (B) Mortality (C) Cost. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Rotavirus current vaccine compared with ideal vaccine in (A) Morbidity (B) Mortality (C) Cost. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. Top Swine Viral Diseases and Their Concerns

This study investigated U.S. swine veterinarians’ perspectives on using viral vaccines to reduce or replace antimicrobial use. The survey identified PRRS, SIV, and rotavirus as the top three swine viral diseases most in need of improved vaccines. This finding aligns with recent surveillance from the Swine Health Information Center, which has reported the rapid spread of PRRS virus lineage 1C.5 and an increase in Influenza A virus cases, especially in wean-to-finish facilities [

7]. Rotavirus also remains a leading cause of pre-weaning mortality in Midwest U.S. herds [

8]. These viruses contribute to increased antimicrobial use by suppressing the immune system and damaging physical barriers; for example, PRRS targets immune cells [

9], while SIV and rotavirus compromise respiratory and intestinal barriers, respectively [

10]. These weakened host defenses leave pigs vulnerable to secondary bacterial infections. Our survey respondents confirmed they use more antimicrobials to address these complications, particularly in PRRS-positive herds. This observation is supported by previous studies that noted a 379% increase in antimicrobial use in nursery pigs following PRRS outbreaks [

6].

Veterinarians in our study expressed significant concerns about the limited cross-protection of current vaccines against new viral variants. While many use modified-live virus (MLV) vaccines for PRRS, they often rely on autogenous vaccines for SIV and rotavirus (

Table 3), underscoring a critical gap in commercial product efficacy. Each vaccine type has specific limitations. For PRRS, MLV vaccines pose safety concerns, including temporary drops in productivity and the risk of the vaccine reverting to virulence. They can also cause persistent viremia, which complicates diagnoses and increases the risk of recombination with wild-type strains [

11,

12,

13]. For SIV, all reported commercial vaccines were whole-inactivated virus (WIV) formulations, administered to sows to transfer passive immunity. However, this strategy is limited by maternally derived antibodies (MDA); while homologous MDA protects piglets, heterologous MDA not only fails to confer protection but may also worsen clinical symptoms after post-weaning infection [

14,

15]. For rotavirus, most commercial vaccines target rotavirus A (RVA), even though rotavirus C (RVC) has emerged as a major cause of neonatal diarrhea [

16]. A nationwide study reported RVC in 76.1% of pre-weaning piglets with clinical diarrhea, yet no effective commercial vaccine is available due to the lack of a suitable cell culture system for its development [

17,

18]. These limitations highlight the urgent need for vaccines that induce broader cross-protective immunity.

4.2. Promising Strategies for Vaccine Improvement of the Top Swine Viral Diseases

For PRRS, switching from intramuscular (IM) to intradermal (ID) injection could significantly improve PRRS MLV vaccine safety. ID administration can shorten viremia duration, reduce viral shedding, and limit tissue damage, which are key safety concerns with MLV vaccines [

19,

20,

21,

22]. This method also requires a lower dose and causes less stress and tissue damage in pigs, suggesting reduced inflammatory responses and improved post-vaccination recovery [

23]. However, further research is needed to evaluate its effectiveness in field conditions and assess its practicality for large-scale commercial swine production.

For SIV, current vaccines are mostly WIV formulations, which are susceptible to MDA interference and have been linked to vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease (VAERD) [

14]. As an alternative, adenovirus-vectored vaccines can induce strong, long-lasting humoral and cellular immune responses [

24]. Crucially, these vaccines can bypass MDA interference and reduce viral shedding, addressing major limitations of WIV vaccines [

25]. Given that MDA interference was identified as a major cause of SIV vaccine failure in our study, these findings highlight the potential of adenovirus-vectored platforms as a promising strategy for improving SIV control.

For rotavirus, since piglets are highly susceptible and exposed to rotavirus immediately after birth, a primary strategy is to enhance maternal immunity. While natural planned exposure (NPE) is currently the main method to stimulate passive lactogenic immunity in sows to protect piglets from RVC infection, it carries risks like shedding of RVC and introducing unintended pathogens [

26,

27,

28]. Prescription platform vaccines, like those developed by Medgene Labs and SEQUIVITY from Merck Animal Health, offer a promising alternative. These platforms use a standardized production system with a single vector or expression backbone. By inserting specific genes of interest (GOI) coding for immunogenic proteins of RVC into this system, they can rapidly produce non-replicating vaccines tailored to the prevalent strains in a particular herd or region. This technology can significantly improve immunization efficacy. The current production timeline of 12–16 weeks remains a limitation, but optimizing expression systems could reduce this time and make the approach more feasible for rapid response.

4.3. Barriers and the Role of Veterinarians

The top three viral diseases create a significant economic burden, with losses estimated at

$4.10 per pig for PRRS,

$2.10 for SIV, and

$0.90 for rotavirus. While vaccination is a key tool for mitigating these losses, concerns about cost-effectiveness persist. Our study found the average per-dose cost for commercial PRRS, SIV, and rotavirus vaccines to be

$1.16,

$0.83, and

$0.90, respectively. Despite perceiving these prices as somewhat expensive, veterinarians showed a strong willingness to pay more for improved vaccines, with acceptable price increases of 28% for PRRS (

$1.48), 66.3% for SIV (

$1.38), and 35.6% for rotavirus (

$1.22). This finding demonstrates a clear understanding that the long-term economic benefits of effective disease control outweigh the initial vaccine cost. However, cost remains a significant barrier, especially for small to medium-sized operations with tighter margins. For example, the Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project found that only about 30% of surveyed U.S. sow farms had adopted PRRS vaccination [

29]. Adoption rates could be improved through cost-sharing mechanisms, government subsidies, or more effective vaccines [

30]. Many producers still see antibiotics as a more cost-effective management strategy, often underestimating the long-term financial benefits of vaccination, such as reduced antimicrobial use and improved herd health.

Swine veterinarians play a central role in the veterinarian-client-patient relationship (VCPR) and are at the forefront of disease prevention, control, and biosecurity in swine production [

31]. Maintaining herd health is not a static process; rather, it requires continuous evaluation and adjustment of management strategies. As trusted advisors to producers, veterinarians apply their expertise to provide critical guidance on herd health management, including vaccination protocols and antimicrobial use strategies [

32,

33]. However, the decision-making process regarding disease management is complex and influenced by various factors [

34]. Understanding how veterinarians weigh the use of vaccines versus antimicrobials is crucial to identifying the factors that shape their recommendations. These considerations underscore the importance of veterinarians as the key focus of this study. Despite their significant role, there is a notable lack of research on veterinarians’ perspectives regarding the effectiveness, safety, and economic feasibility of viral vaccines as alternatives to antimicrobials in swine production. This gap limits our understanding of how veterinarians perceive vaccine limitations and their practical application in real-world production settings. By addressing this gap, our study provides valuable insights from their practical experiences and concerns, which can contribute to future vaccine development and policy decisions.

4.4. Limitations of the Study and Future Directions

This study has potential limitations that should be considered. The primary limitation is the small sample size; of the 200 veterinarians invited to participate, only 19 completed more than 80% of the survey. The extensive length of the questionnaire, which covered 13 different pathogens and took an average of over 30 minutes to complete, likely contributed to the low response rate and incomplete responses.

Future research should build on this foundation with more targeted investigations. Integrating production data from swine farms would complement veterinarians’ perspectives and reduce reliance on recall-based responses. While our study focuses on U.S. swine veterinarians, its findings are highly relevant to the broader swine industry. Further research with larger sample sizes and field-level assessments would strengthen our understanding of vaccine limitations and inform more precise development strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study offers key insights from U.S. swine veterinarians on the challenges and opportunities of using viral vaccines as an alternative to antimicrobials or to reduce antimicrobial use. Our findings highlight an urgent need for improved vaccines for PRRS, SIV, and rotavirus, which cause significant economic losses and increase the need for antimicrobials. Veterinarians identified major challenges with current vaccines, including limited cross-protection, safety concerns, and issues with cost and availability. However, despite these limitations, they expressed strong support for using vaccines to reduce antimicrobial reliance. Addressing these gaps will require future research focused on targeted vaccine development and a better understanding of the factors that influence veterinarians’ decision-making. Ultimately, these efforts will support more effective disease control, reduce antimicrobial use, and protect both animal and public health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W. and J.S.; methodology, D.L., X.Z., M.D.A., J.T.G., B.L., H.K., D.P., R.M., Y.L., N.M., A.C., B.S., L.W., J.S.; software, D.L. and X.Z.; validation, D.L. and X.Z.; formal analysis, D.L. and X.Z.; investigation, D.L., X.Z., M.D.A., J.T.G., B.L., H.K., D.P., R.M., Y.L., N.M., A.C., B.S., L.W., J.S.; resources, M.D.A., J.T.G., L.K., J.F.C., C.B., B.L., H.K., D.P., L.W., J.S.; data curation, D.L. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, M.D.A., J.T.G., L.K., J.F.C., C.B., B.L., H.K., D.P., R.M., Y.L., N.M., A.C., B.S., L.W., J.S.; visualization, D.L. and X.Z.; supervision, M.D.A., J.T.G., B.L., H.K., D.P., L.W., J.S.; funding acquisition, L.W. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by an award from the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility Transition Fund; the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch-Multistate project (grant number: 1021491); the USDA ARS Non-Assistance Cooperative Agreements (grant numbers: 58-8064-8-011, 58-8064-9-007, 58-3020-9-020); the USDA NIFA Subaward #25-6226-0633-002; and the Department of Homeland Security (grant number:70RSAT19CB0000027). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Kansas State University Research Compliance Office (Protocol # IRB-12219, approval date 4 June 2024), and followed all relevant laws and guidelines in its procedures. We maintained the privacy rights of all human subjects involved in the experiments and ensured that informed consent was obtained from each participant before their involvement.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our gratitude to all the veterinarians who took the time to complete our survey. Their valuable insights have been instrumental in advancing our study. We are especially grateful to Dr. Michael Senn and Dr. Tom Petznick for their invaluable suggestions and guidance, which have significantly improved this project.

Conflicts of Interest

J.F.C. was employed by Carthage Veterinary Service, LTD., Carthage, IL 62321, USA. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kirchhelle, C. Pharming animals: a global history of antibiotics in food production (1935–2017). Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulchandani, R.; Wang, Y.; Gilbert, M.; Van Boeckel, T. P. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food-producing animals: 2020 to 2030. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023, 3, e0001305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Hollis, A. The effect of antibiotic usage on resistance in humans and food-producing animals: a longitudinal, One Health analysis using European data. Front Public Health. 2023, 11, 1170426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry #213. https://www.fda.gov/media/83488/download. (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration. 2023 Summary report on antimicrobials sold or distributed for use in food-producing animals. https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/antimicrobial-resistance/2023-summary-report-antimicrobials-sold-or-distributed-use-food-producing-animals. (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Machado, I.; Petznick, T.; Poeta Silva, A. P. S.; Wang, C.; Karriker, L.; Linhares, D. C. L.; Silva, G. S. Assessment of changes in antibiotic use in grow-finish pigs after the introduction of PRRSV in a naïve farrow-to-finish system. Prev Vet Med. 2024, 233, 106350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swine Health Information Center. Domestic Swine Disease Monitoring Report. https://www.swinehealth.org/domestic-disease-surveillance-reports/. (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Will, K. J.; Magalhaes, E. S.; Moura, C. A. A.; Trevisan, G.; Silva, G. S.; Mellagi, A. P. G.; Ulguim, R. R.; Bortolozzo, F. P.; Linhares, D. C. L. Risk factors associated with piglet pre-weaning mortality in a Midwestern US swine production system from 2020 to 2022. Prev Vet Med. 2024, 232, 106316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, H.; Liu, M.; Wen, S.; Ren, J. Progress in PRRSV infection and adaptive immune response mechanisms. Viruses. 2023, 15, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janke B., H. Influenza A virus infections in swine: pathogenesis and diagnosis. Vet Pathol. 2014, 51, 410–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charerntantanakul, W. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus vaccines: Immunogenicity, efficacy and safety aspects. World J Virol. 2012, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X. Y.; Xia, D. S.; Luo, L. Z.; An, T. Q. . Recombination of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: features, possible mechanisms, and future directions. Viruses. 2024, 16, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graaf-Rau, A.; Schmies, K.; Breithaupt, A.; Ciminski, K.; Zimmer, G.; Summerfield, A.; Sehl-Ewert, J.; Lillie-Jaschniski, K.; Helmer, C.; Bielenberg, W.; Grosse Beilage, E.; Schwemmle, M.; Beer, M.; Harder, T. Reassortment incompetent live attenuated and replicon influenza vaccines provide improved protection against influenza in piglets. NPJ Vaccines. 2024, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvesen H., A.; Whitelaw C. B., A. Current and prospective control strategies of influenza A virus in swine. Porcine Health Manag. 2021, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petro-Turnquist, E.; Pekarek, M. J.; Weaver, E. A. Swine influenza A virus: challenges and novel vaccine strategies. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1336013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Shepherd, F. K.; Springer, N. L.; Mwangi, W.; Marthaler, D. G. Rotavirus infection in swine: genotypic diversity, immune responses, and role of gut microbiome in rotavirus immunity. Pathogens. 2022, 11, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepngeno, J.; Diaz, A.; Paim, F. C.; Saif, L. J.; Vlasova, A. N. Rotavirus C: prevalence in suckling piglets and development of virus-like particles to assess the influence of maternal immunity on the disease development. Vet Res. 2019, 50, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Raev, S.; Kick, M. K.; Raque, M.; Saif, L. J.; Vlasova, A. N. Rotavirus C replication in porcine intestinal enteroids reveals roles for cellular cholesterol and sialic acids. Viruses. 2022, 14, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chase, C.; Daniels, C.; Garcia, R.; Milward, F. Needle-free injection technology in swine: Progress toward vaccine efficacy and pork quality. Journal of Swine Health and Production, 2008, 16, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madapong, A.; Saeng-Chuto, K.; Tantituvanont, A.; Nilubol, D. Safety of PRRSV-2 MLV vaccines administrated via the intramuscular or intradermal route and evaluation of PRRSV transmission upon needle-free and needle delivery. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 23107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renson, P.; Mahé, S.; Andraud, M.; Le Dimna, M.; Paboeuf, F.; Rose, N.; Bourry, O. Effect of vaccination route (intradermal vs. intramuscular) against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome using a modified live vaccine on systemic and mucosal immune response and virus transmission in pigs. BMC Vet Res. 2024, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, L.; Li, Y.; Baratelli, M.; Martín-Valls, G.; Cortey, M.; Miranda, J.; Martín, M.; Mateu, E. In the presence of non-neutralising maternally derived antibodies, intradermal and intramuscular vaccination with a modified live vaccine against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus 1 (PRRSV-1) induce similar levels of neutralising antibodies or interferon-gamma secreting cells. Porcine Health Manag. 2022, 8, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Maragkakis, G.; Athanasiou, L. V.; Korou, L. M.; Chaintoutis, S. C.; Dovas, C.; Perrea, D. N.; Papakonstantinou, G.; Christodoulopoulos, G.; Maes, D.; Papatsiros, V. G. Angiotensin II Blood Serum Levels in Piglets, after Intra-Dermal or Intra-Muscular Vaccination against PRRSV. Vet Sci. 2022, 9, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petro-Turnquist, E.; Pekarek, M.; Jeanjaquet, N.; Wooledge, C.; Steffen, D.; Vu, H.; Weaver, E. A. Adenoviral-vectored epigraph vaccine elicits robust, durable, and protective immunity against H3 influenza A virus in swine. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1143451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, R. D.; Lager, K. M. Overcoming maternal antibody interference by vaccination with human adenovirus 5 recombinant viruses expressing the hemagglutinin and the nucleoprotein of swine influenza virus. Vet Microbiol, 2006; 118, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Shepherd, F. K.; Springer, N. L.; Mwangi, W.; Marthaler, D. G. Rotavirus infection in swine: genotypic diversity, immune responses, and role of gut microbiome in rotavirus immunity. Pathogens. 2022, 11, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.V.; Shepherd, F.; Dominguez, F.; Pittman, J.; Marthaler, D.; Karriker, L. Evaluating natural planned exposure protocols on rotavirus shedding patterns in gilts and the impact on their suckling pigs. Journal of Swine Health and Production, 2023, 31, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Anderson, A. V.; Pittman, J.; Springer, N. L.; Marthaler, D. G.; Mwangi, W. Antibody response to Rotavirus C pre-farrow natural planned exposure to gilts and their piglets. Viruses. 2022, 14, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuti, M.; Geary, E.; Picasso, C.; Medrano, M.; Vilalta, C.; Corzo, C. Review of MSHMP PRRS Chart 2-Prevalence. Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project. Available online: https://mshmp.umn.edu/reports (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Valdes-Donoso, P.; Jarvis, L. S. Combining epidemiology and economics to assess control of a viral endemic animal disease: Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS). PLoS One, 2022, 17, e0274382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, J. Swine veterinarians-key players in the pork production chain. Can Vet J. 2021, 62, 515–516. [Google Scholar]

- Hockenhull, J.; Turner, A. E.; Reyher, K. K.; Barrett, D. C.; Jones, L.; Hinchliffe, S.; Buller, H. J. Antimicrobial use in food-producing animals: a rapid evidence assessment of stakeholder practices and beliefs. Vet Rec. 2017, 181, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visschers, V. H.; Backhans, A.; Collineau, L.; Iten, D.; Loesken, S.; Postma, M.; Belloc, C.; Dewulf, J.; Emanuelson, U.; Beilage, E. G.; Siegrist, M.; Sjölund, M.; Stärk, K. D. Perceptions of antimicrobial usage, antimicrobial resistance and policy measures to reduce antimicrobial usage in convenient samples of Belgian, French, German, Swedish and Swiss pig farmers. Prev Vet Med. 2015, 119, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, L. A.; Latham, S. M.; Williams, N. J.; Dawson, S.; Donald, I. J.; Pearson, R. B.; Smith, R. F.; Pinchbeck, G. L. Understanding the culture of antimicrobial prescribing in agriculture: a qualitative study of UK pig veterinary surgeons. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016, 71, 3300–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).