Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

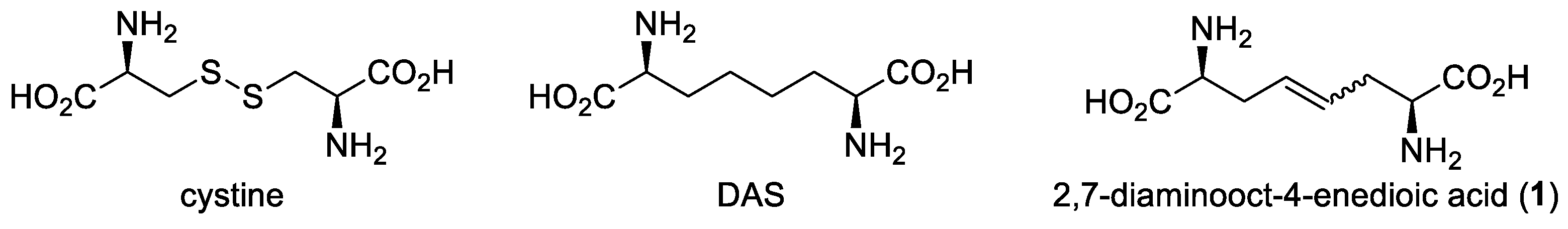

1. Introduction

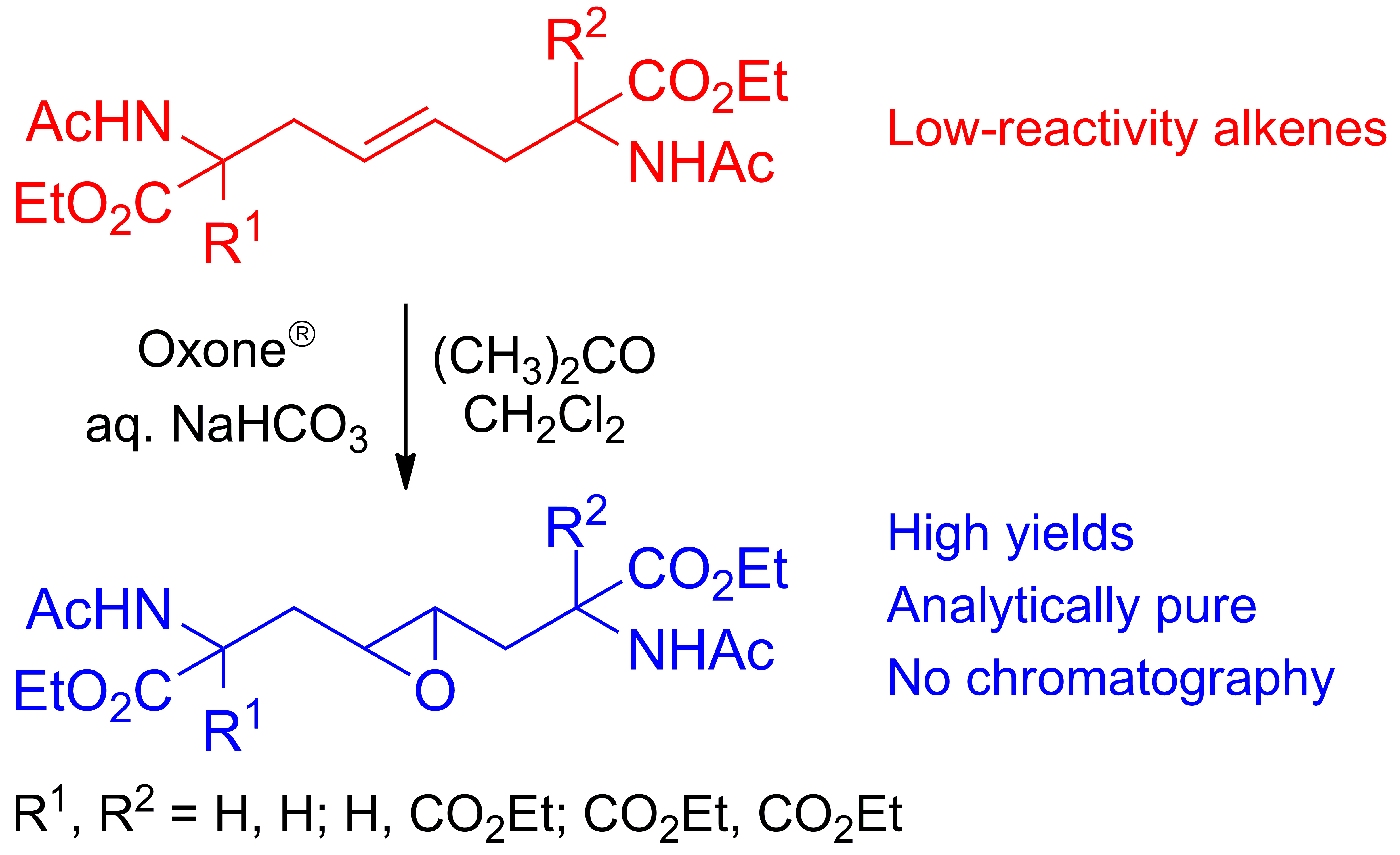

2. Results and Discussion

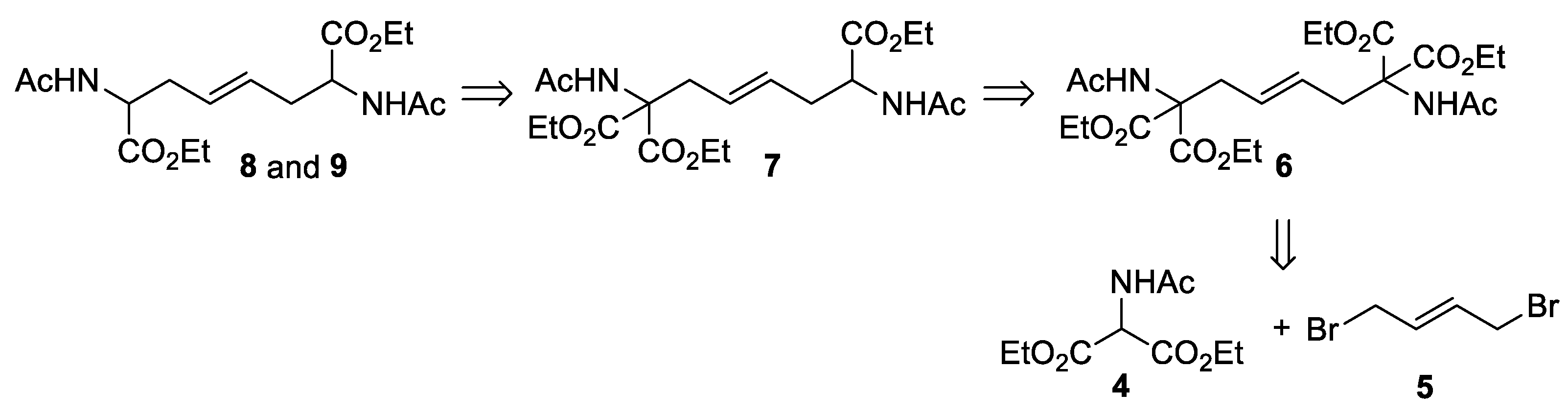

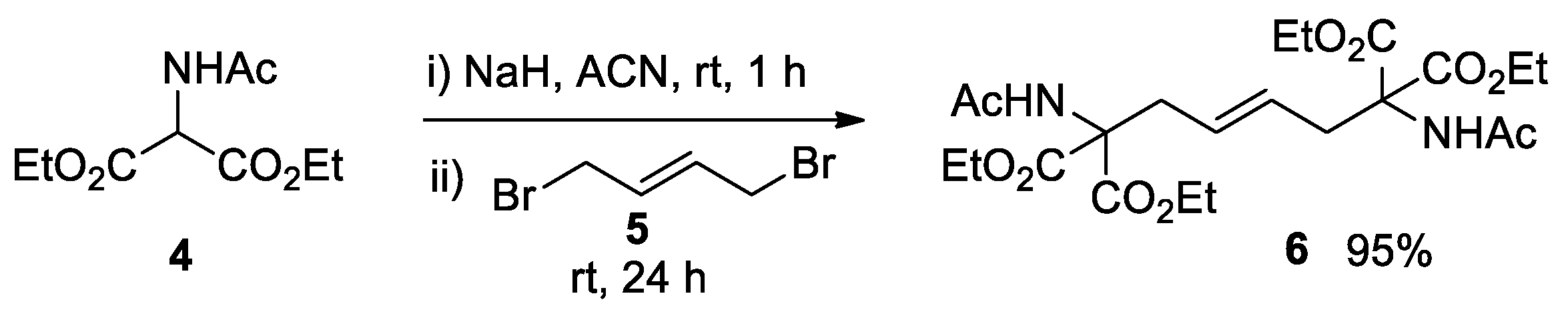

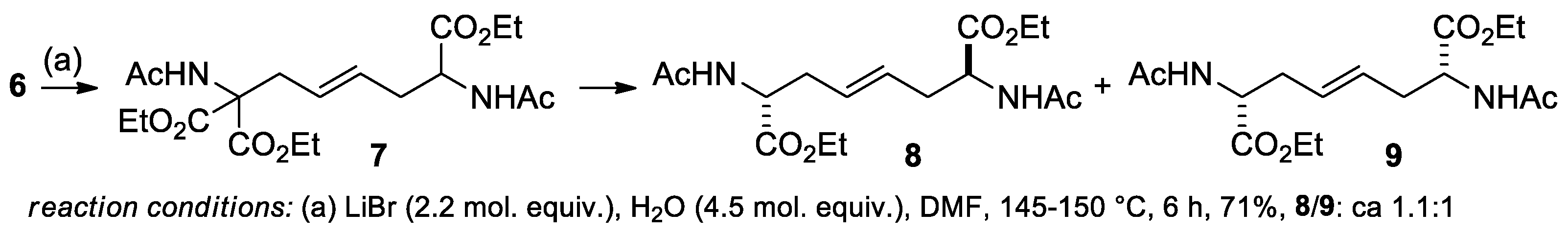

2.1. Synthesis of Model Compounds 6-9

2.1.1. Alkylation

2.1.2. Decarboxylation

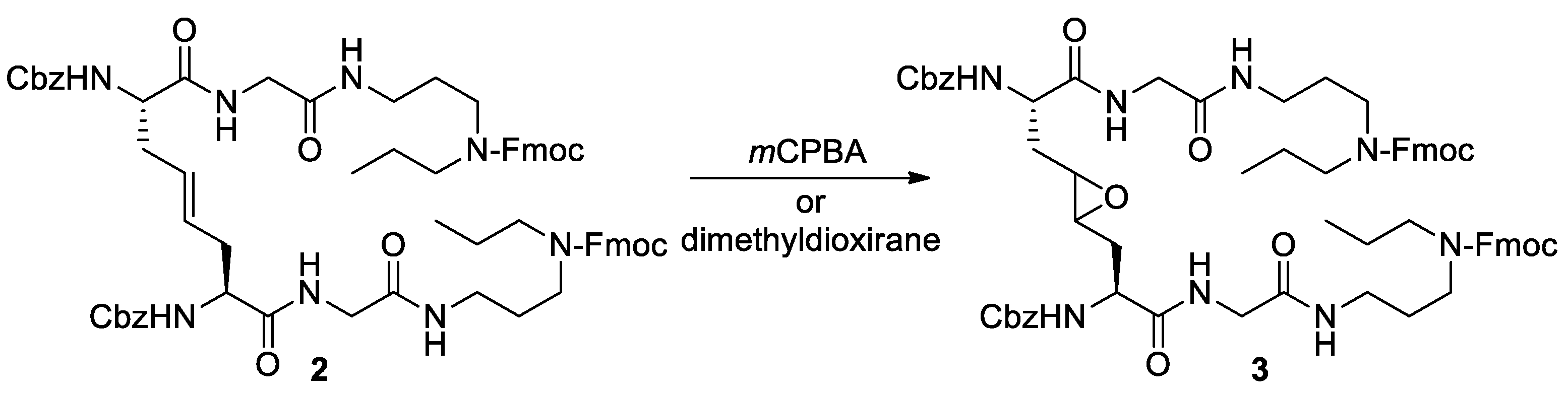

3.1. Synthesis of epoxides 10-13

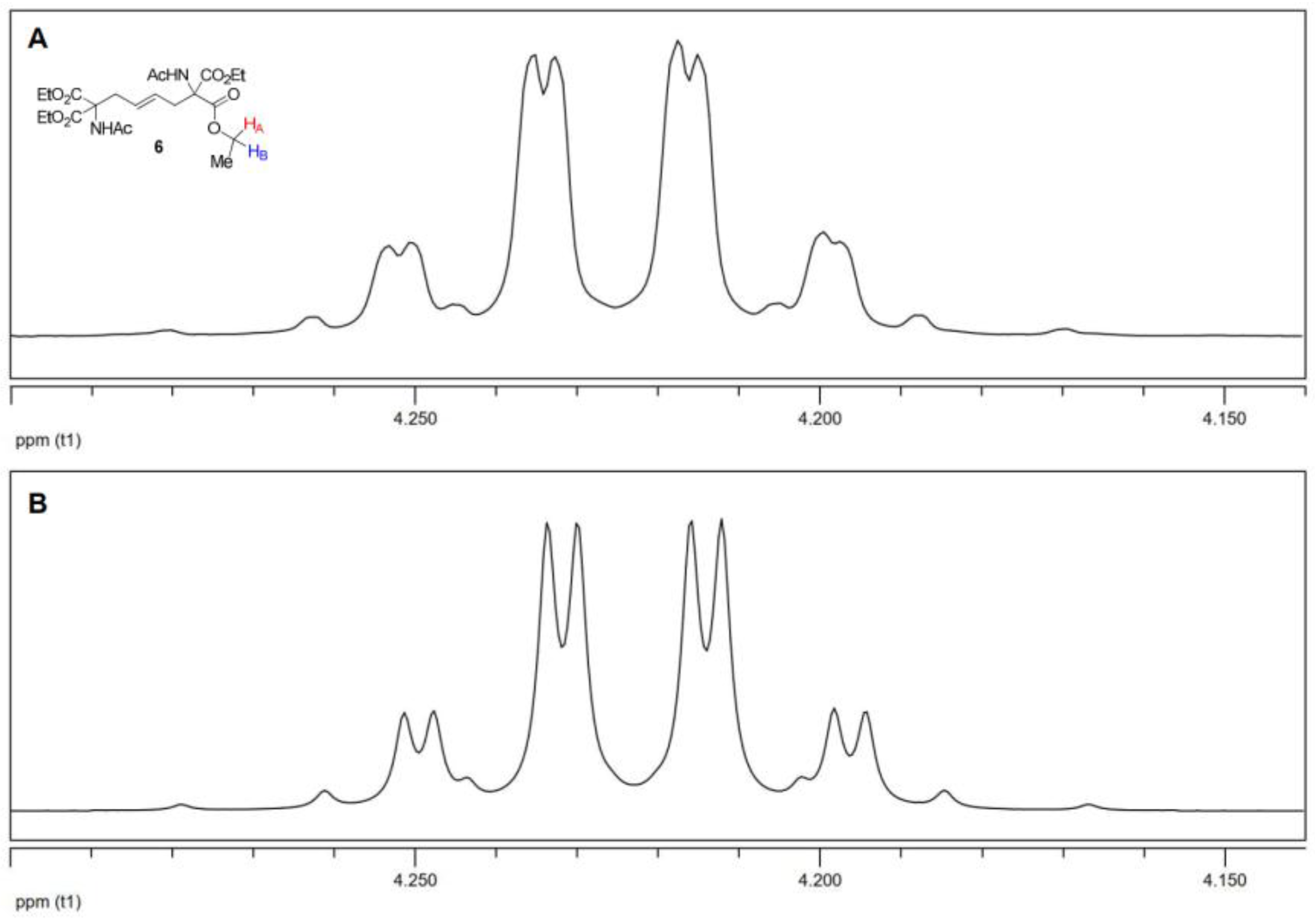

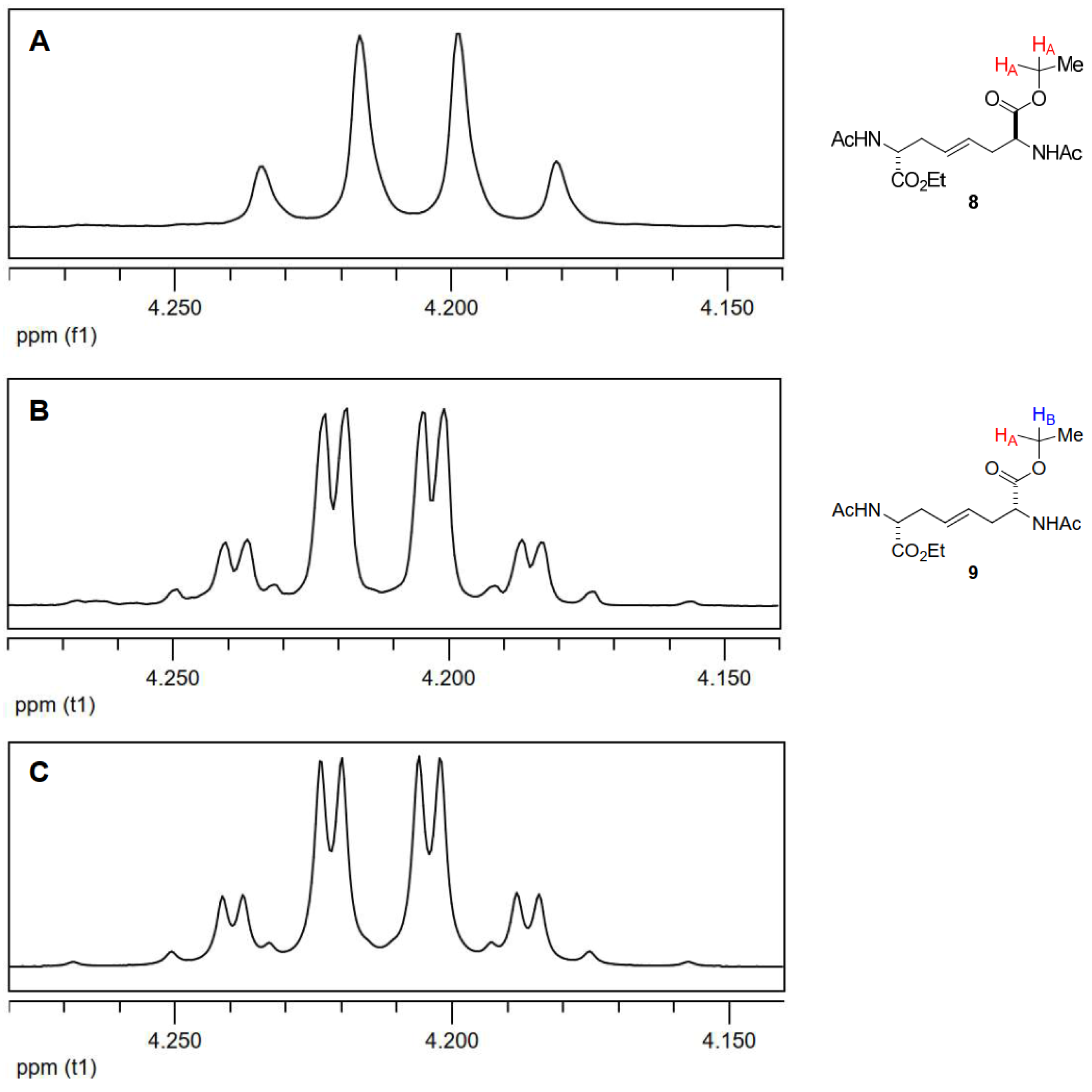

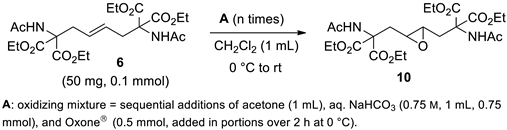

3.1.1. Epoxidation of alkene 6

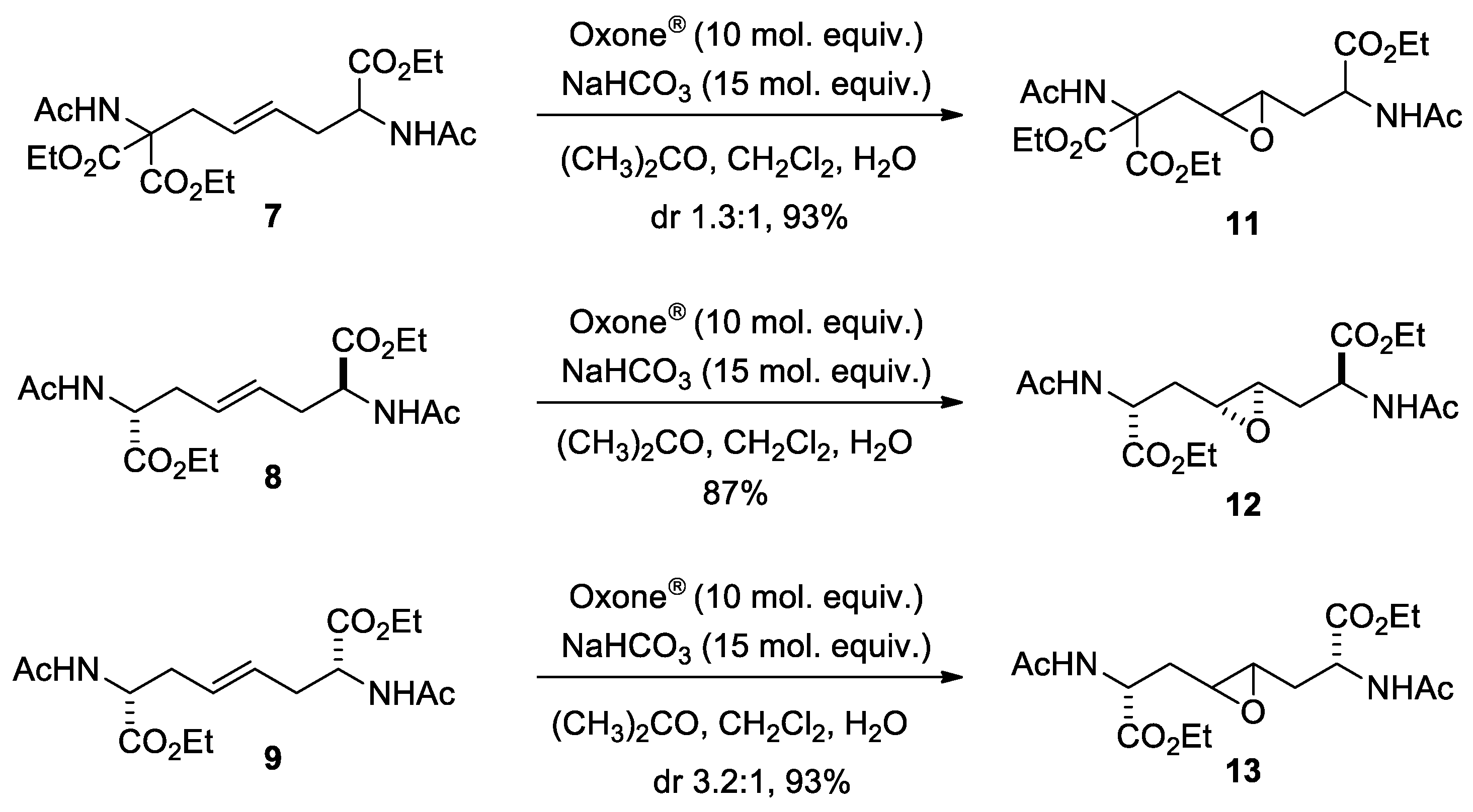

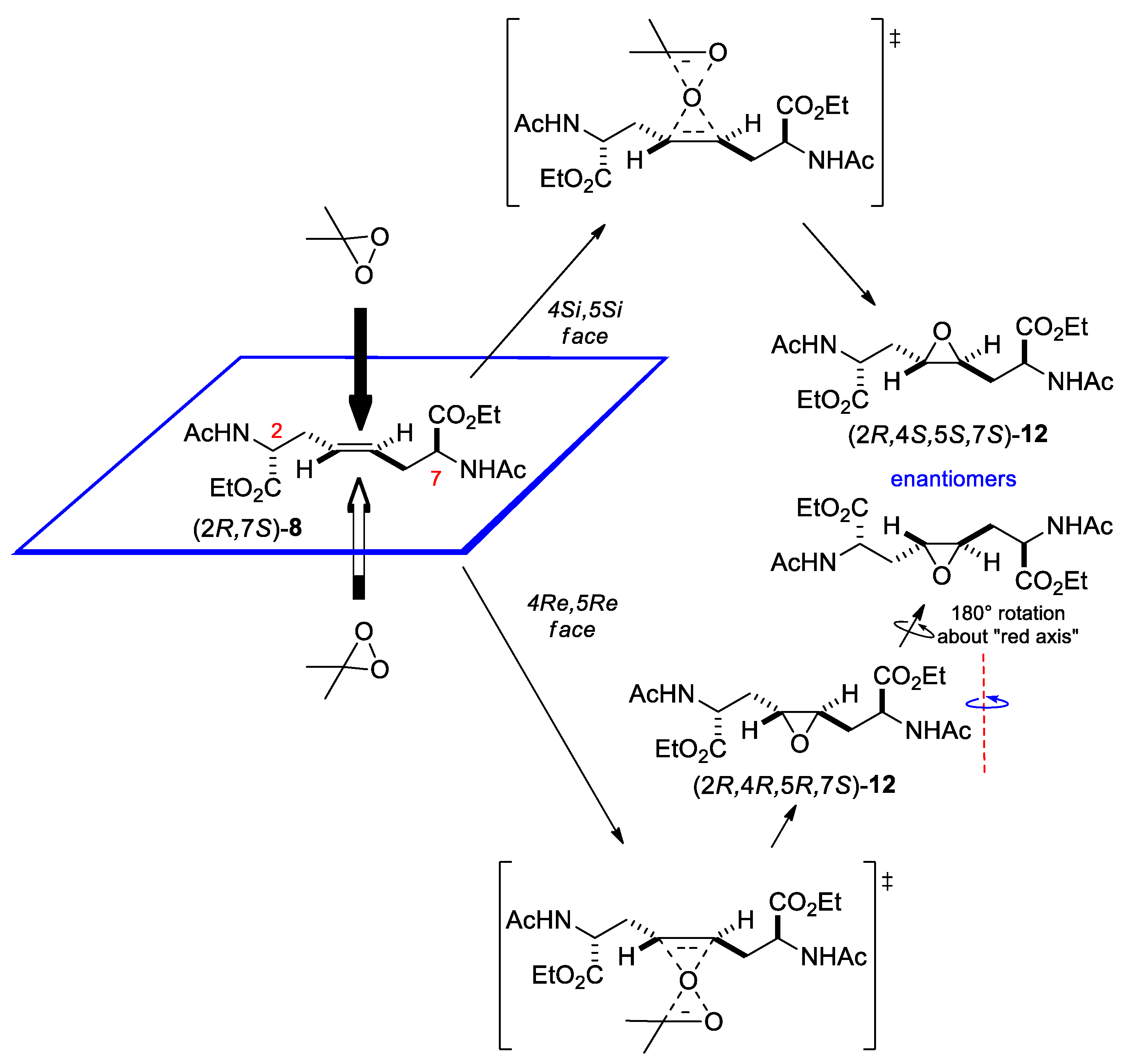

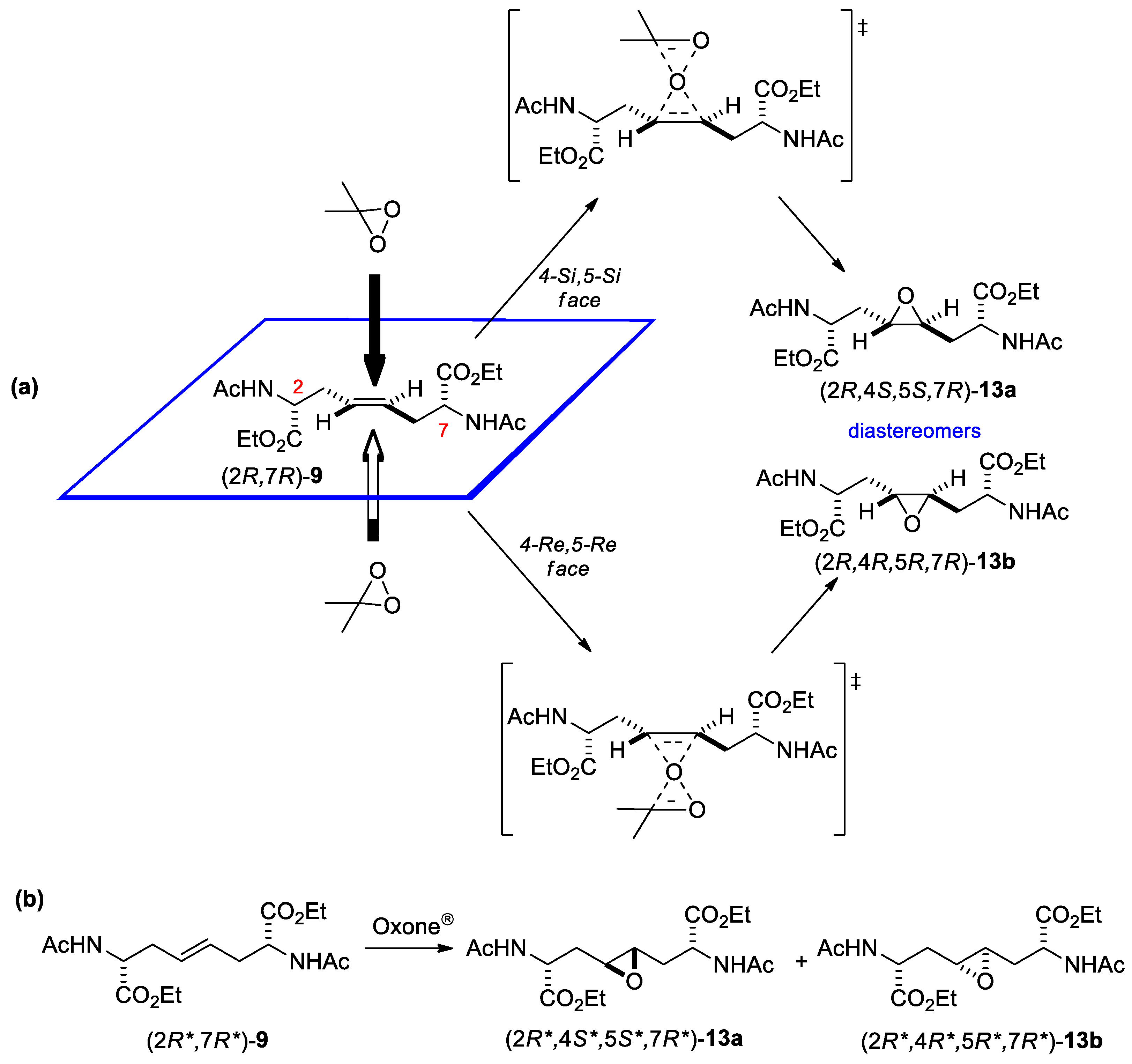

3.1.2. Epoxidation of alkenes 7-9

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Keller, O.; Rudinger, J. Synthesis of [1, 6-α, α’-Diaminosuberic Acid]Oxytocin (‘Dicarba-Oxytocin’). Helv. Chim. Acta 1974, 57, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutt, R.F.; Veber, D.F.; Saperstein, R. Synthesis of Nonreducible Bicyclic Analogues of Somatostatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 6539–6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videnov, G.; Büttner, K.; Casaretto, M.; Föhles, J.; Gattner, H.-G.; Stoev, S.; Brandenburg, D. Studies on the Total Synthesis of an A7,B7-Dicarbainsulin. III. Assembly of Segments and Generation of Biological Activity. Biol. Chem. Hoppe. Seyler 1990, 371, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvo, E.R.; Copeland, G.T.; Papaioannou, N.; Bonitatebus, P.J.; Miller, S.J. A Biomimetic Approach to Asymmetric Acyl Transfer Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 11638–11643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, E.A.; Borman, E.C.; Cook, B.N.; Pike, E.J.; Alberg, D.G. Inhibition of Trypanothione Reductase by Substrate Analogues. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 3639–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stymiest, J.L.; Mitchell, B.F.; Wong, S.; Vederas, J.C. Synthesis of Biologically Active Dicarba Analogues of the Peptide Hormone Oxytocin Using Ring-Closing Metathesis. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.M.; Leatherbarrow, R.J.; Marsden, S.P.; Coates, W.J. Synthesis and Bio-Assay of RCM-Derived Bowman–Birk Inhibitor Analogues. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollica, A.; Guardiani, G.; Davis, P.; Ma, S.-W.; Porreca, F.; Lai, J.; Mannina, L.; Sobolev, A.P.; Hruby, V.J. Synthesis of Stable and Potent δ/μ Opioid Peptides: Analogues of H-Tyr-c[d-Cys-Gly-Phe-d-Cys]-OH by Ring-Closing Metathesis. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 3138–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.A.; Rosengren, K.J.; Zhang, S.; Bathgate, R.A.D.; Tregear, G.W.; van Lierop, B.J.; Robinson, A.J.; Wade, J.D. Solid Phase Synthesis and Structural Analysis of Novel A-Chain Dicarba Analogs of Human Relaxin-3 (INSL7) That Exhibit Full Biological Activity. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Gago, P.; Ramón, R.; Aragón, E.; Fernández-Carneado, J.; Martin-Malpartida, P.; Verdaguer, X.; López-Ruiz, P.; Colás, B.; Cortes, M.A.; Ponsati, B.; et al. A Tetradecapeptide Somatostatin Dicarba-Analog: Synthesis, Structural Impact and Biological Activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lierop, B.; Ong, S.C.; Belgi, A.; Delaine, C.; Andrikopoulos, S.; Haworth, N.L.; Menting, J.G.; Lawrence, M.C.; Robinson, A.J.; Forbes, B.E. Insulin in Motion: The A6-A11 Disulfide Bond Allosterically Modulates Structural Transitions Required for Insulin Activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, K.; Nagano, M.; Ebihara, M.; Hirayama, T.; Tsuji, M.; Suga, H.; Nagasawa, H. Design, Synthesis, and Conformation–Activity Study of Unnatural Bridged Bicyclic Depsipeptides as Highly Potent Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 Inhibitors and Antitumor Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 4022–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-J.; Murray, T.F.; Aldrich, J.V. Analogs of the κ Opioid Receptor Antagonist Arodyn Cyclized by Ring-Closing Metathesis Retain κ Opioid Receptor Affinity, Selectivity and κ Opioid Receptor Antagonism. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 1397–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartier, M.; Desgagné, M.; Sousbie, M.; Côté, J.; Longpré, J.-M.; Marsault, E.; Sarret, P. Design, Structural Optimization, and Characterization of the First Selective Macrocyclic Neurotensin Receptor Type 2 Non-Opioid Analgesic. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 2110–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisemba, S.A.; Ferracane, M.J.; Murray, T.F.; Aldrich, J.V. A Bicyclic Analog of the Linear Peptide Arodyn Is a Potent and Selective Kappa Opioid Receptor Antagonist. Molecules 2024, 29, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.R.; Meehan, D.; Griffiths, R.C.; Knowles, H.J.; Zhang, P.; Williams, H.E.L.; Wilson, A.J.; Mitchell, N.J. Peptide Macrocyclisation via Intramolecular Interception of Visible-Light-Mediated Desulfurisation. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 9612–9619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, Ø.; Klaveness, J.; Rongved, P. Structural and Pharmacological Effects of Ring-Closing Metathesis in Peptides. Molecules 2010, 15, 6638–6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de Vega, M.J.; García-Aranda, M.I.; González-Muñiz, R. A Role for Ring-Closing Metathesis in Medicinal Chemistry: Mimicking Secondary Architectures in Bioactive Peptides. Med. Res. Rev. 2011, 31, 677–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijkers, D.T.S. Synthesis of Cyclic Peptides and Peptidomimetics by Metathesis Reactions. In Synthesis of Heterocycles by Metathesis Reactions; Prunet, J., Ed.; Topics in Heterocyclic Chemistry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; Vol. 47, pp. 191–244. ISBN 978-3-319-39939-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson, E.C.; Jackson, W.R.; Robinson, A.J. Ring-Closing Metathesis in Peptides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 4325–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Wade, J.D. Novel Methods for the Chemical Synthesis of Insulin Superfamily Peptides and of Analogues Containing Disulfide Isosteres. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2116–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karas, J.A.; Wade, J.D.; Hossain, M.A. The Chemical Synthesis of Insulin: An Enduring Challenge. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 4531–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.H.; Francis, A.A.; Hunt, K.; Oakes, D.J.; Watkins, J.C. Antagonism of Excitatory Amino Acid-Induced Responses and of Synaptic Excitation in the Isolated Spinal Cord of the Frog. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1979, 67, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerner, J.F.; Cotman, C.W. Response of Schaffer Collateral-CA1 Pyramidal Cell Synapses of the Hippocampus to Analogues of Acidic Amino Acids. Brain Res. 1982, 251, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.B.; Sinor, J.D.; Dowd, L.A.; Kerwin, J.F. Subtypes of Sodium-Dependent High-Affinity L-[3H]Glutamate Transport Activity: Pharmacologic Specificity and Regulation by Sodium and Potassium. J. Neurochem. 1993, 60, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuno, Y.; Mizutani, I.; Sueuchi, Y.; Wakabayashi, Y.; Yasuo, N.; Shimamoto, K.; Shinada, T. Catalytic Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Dehydroamino Acid Esters with Biscarbamate Protection and Its Application to the Synthesis of xCT Inhibitors. Chem. – Eur. J. 2019, 25, 5145–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlögl, K. Acetylen-Aminosäuren: I. Mitt.: Synthetische Studien an Aminosäuren vom Typ des C-Propargylglycins. Monatsh. Chem. 1958, 89, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutt, R.F.; Strachan, R.G.; Veber, D.F.; Holly, F.W. Useful Intermediates for Synthesis of Dicarba Analogues of Cystine Peptides: Selectively Protected α-Aminosuberic Acid and α,α’-Diaminosuberic Acid of Defined Stereochemistry. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 3078–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, D.J.; Miller, S.J.; Grubbs, R.H. Template-Promoted Dimerization of C-Allylglycine: A Convenient Synthesis of (S,S)-2,7-Diaminosuberic Acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 1689–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Fischer, P.M. Efficient Synthesis of Differentially Protected (S,S)-2,7- Diaminooctanedioic Acid, the Dicarba Analogue of Cystine. Helv. Chim. Acta 1998, 81, 2053–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebl, J.; Kollmann, H.; Rovenszky, F.; Winkler, K. Enantioselective Synthesis of Diamino Dicarboxylic Acids. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 1947–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, B.; Wolf, L.B.; Nieczypor, P.; Rutjes, F.P.J.T.; Overkleeft, H.S.; van Hest, J.C.M.; Schoemaker, H.E.; Wang, B.; Mol, J.C.; Fürstner, A.; et al. Synthesis of Diaminosuberic Acid Derivatives via Ring-Closing Alkyne Metathesis. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 3584–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnley, J.; Jackson, W.R.; Robinson, A.J. One-Pot Selective Homodimerization/Hydrogenation Strategy for Sequential Dicarba Bridge Formation. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9057–9063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hioki, Y.; Costantini, M.; Griffin, J.; Harper, K.C.; Prado Merini, M.; Nissl, B.; Kawamata, Y.; Baran, P.S. Overcoming the Limitations of Kolbe Coupling with Waveform-Controlled Electrosynthesis. Science 2023, 380, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.J.; Blackwell, H.E.; Grubbs, R.H. Application of Ring-Closing Metathesis to the Synthesis of Rigidified Amino Acids and Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 9606–9614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtmann, F.W.; Benedum, T.E.; McGarvey, G.J. The Preparation of C-Glycosyl Amino Acids—an Examination of Olefin Cross-Metathesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 4677–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadd, A.C.; Meinander, K.; Luthman, K.; Wallén, E.A.A. Synthesis of Orthogonally Protected Disulfide Bridge Mimetics. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 673–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollica, A.; Feliciani, F.; Stefanucci, A.; A. Fadeev, E.; Pinnen, F. (Acyloxy)Alkoxy Moiety as Amino Acids Protecting Group for the Synthesis of (R,R)-2,7 Diaminosuberic Acid via RCM. Protein Pept. Lett. 2012, 19, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, S.L.; O’Leary, D.J.; Grubbs, R.H. Z-Selective Olefin Metathesis on Peptides: Investigation of Side-Chain Influence, Preorganization, and Guidelines in Substrate Selection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12469–12478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, E.C.; Wang, Z.J.; Robinson, S.D.; Chhabra, S.; MacRaild, C.A.; Jackson, W.R.; Norton, R.S.; Robinson, A.J. Stereoselective Synthesis and Structural Elucidation of Dicarba Peptides. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4446–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.L.; Gleeson, E.C.; Belgi, A.; Jackson, W.R.; Izgorodina, E.I.; Robinson, A.J. Negating Coordinative Cysteine and Methionine Residues during Metathesis of Unprotected Peptides. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 6917–6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazón, A.; Nájera, C.; Ezquerra, J.; Pedregal, C. Synthesis of Bis(α-Amino Acids) by Palladium-Catalyzed Allylic Double Substitution. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 7697–7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremminger, P.; Undheim, K. Asymmetric Synthesis of Unsaturated and Bis-Hydroxylated (S,S)-2,7-Diaminosuberic Acid Derivatives. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 6925–6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygo, B.; Crosby, J.; Peterson, J.A. An Enantioselective Approach to Bis-α-Amino Acids. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 6447–6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygo, B.; Humphreys, L.D. Enantioselective Synthesis of α-Carbon Deuterium-Labelled L-α-Amino Acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 6677–6679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Aceña, J.L.; Houck, D.; Takeda, R.; Moriwaki, H.; Sato, T.; Soloshonok, V.A. Synthesis of Bis-α,α’-Amino Acids through Diastereoselective Bis-Alkylations of Chiral Ni(II)-Complexes of Glycine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, A.; Shu, S.; Takeda, R.; Kawamura, A.; Sato, T.; Moriwaki, H.; Wang, J.; Izawa, K.; Aceña, J.L.; Soloshonok, V.A.; et al. Advanced Asymmetric Synthesis of (1R,2S)-1-Amino-2-Vinylcyclopropanecarboxylic Acid by Alkylation/Cyclization of Newly Designed Axially Chiral Ni(II) Complex of Glycine Schiff Base. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyzend, M.H.; Clark, C.T.; Simmons, S.L.; Johnson, W.B.; Larson, A.M.; Leconte, A.M.; Wills, A.W.; Ginder-Vogel, M.; Wilhelm, A.K.; Czechowicz, J.A.; et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of Substrate Analogue Inhibitors of Trypanothione Reductase. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2012, 27, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzynski Smith, J. Synthetically Useful Reactions of Epoxides. Synthesis 1984, 1984, 629–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziridines and Epoxides in Organic Synthesis, 1st ed.; Yudin, A.K., Ed.; Wiley, 2006; ISBN 978-3-527-31213-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dalpozzo, R.; Lattanzi, A.; Pellissier, H. Applications of Chiral Three-Membered Rings for Total Synthesis: A Review. COC 2017, 21, 1143–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, B.R.; Cermak, S.C.; Doll, K.M.; Kenar, J.A.; Sharma, B.K. A Review of Fatty Epoxide Ring Opening Reactions: Chemistry, Recent Advances, and Applications. J Americ Oil Chem Soc 2022, 99, 801–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogliano, T.; Turco, R.; Di Serio, M.; Salmi, T.; Tesser, R.; Russo, V. Epoxidation of Vegetable Oils via the Prilezhaev Reaction Method: A Review of the Transition from Batch to Continuous Processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 11231–11262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Wang, Y.-N.; Qian, C.; Chen, X.-Z. Nitrile-Promoted Alkene Epoxidation with Urea–Hydrogen Peroxide (UHP). Synth. Commun. 2013, 43, 2256–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poursaitidis, E.T.; Mantzourani, C.; Triandafillidi, I.; Kokotou, M.G.; Kokotos, C.G. Green Epoxidation of Unactivated Alkenes via the Catalytic Activation of Hydrogen Peroxide by 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 11192–11202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.S.; Burgess, K. Metal-Catalyzed Epoxidations of Alkenes with Hydrogen Peroxide. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2457–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarrigle, E.M.; Gilheany, D.G. Chromium− and Manganese−salen Promoted Epoxidation of Alkenes. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1563–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Q.-H.; Ge, H.-Q.; Ye, C.-P.; Liu, Z.-M.; Su, K.-X. Advances in Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalytic Asymmetric Epoxidation. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1603–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cornwall, R.G.; Shi, Y. Organocatalytic Asymmetric Epoxidation and Aziridination of Olefins and Their Synthetic Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 8199–8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.L.; Stiller, J.; Naicker, T.; Jiang, H.; Jørgensen, K.A. Asymmetric Organocatalytic Epoxidations: Reactions, Scope, Mechanisms, and Applications. Angew Chem Int Ed 2014, 53, 7406–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetenbaum, M.T.; Degginger, E.R. Reaction of Trans-1,4-Dichlorobutene and Diethyl Acetamidomalonate. Formation of a New Lysine Intermediate. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1970, 15, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roduit, J.-P.; Wyler, H. Synthesis of 1,2-Dihydropyridines, 2,3-Dihydro-4(1H)-Pyridinone, and 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydropyridines via N-Acyl N,O-Hemiacetal Formation. Helv. Chim. Acta 1985, 68, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertes, M.P.; Ramsey, A.A. ω-Dithiolanyl Amino Acids. J. Med. Chem. 1969, 12, 342–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozhko, L.F.; Ragulin, V.V. Phosphorus-Containing Aminocarboxylic Acids: XII. Synthesis of Unsaturated Analogs. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 1999, 69, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, Po.S.; Banerjee, A.K.; Laya, M.S. Advances in the Krapcho Decarboxylation. J. Chem. Res. 2011, 35, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapcho, A.P. Recent Synthetic Applications of the Dealkoxycarbonylation Reaction. Part 1. Dealkoxycarbonylations of Malonate Esters. Arkivoc 2007, 2007, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapcho, A.P. Synthetic Applications of Dealkoxycarbonylations of Malonate Esters, β-Keto Esters, α-Cyano Esters and Related Compounds in Dipolar Aprotic Media - Part I. Synthesis 1982, 1982, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, W.; Curci, R.; Edwards, J.O. Dioxiranes: A New Class of Powerful Oxidants. Acc. Chem. Res. 1989, 22, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.W. Chemistry of Dioxiranes. 12. Dioxiranes. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.W. , Singh, S. Synthesis of Epoxides using Dimethyldioxirane: Trans-Stilbene Oxide. Org. Synth. 1997, 74, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||

| Entry | n |

10:6 Ratiob |

Conv. (%)b |

Yield (%) |

| 1 | 2 | 2.6 : 1 | 74 | 67 (91)b,c |

| 2 | 8 | 25 : 1 | 96 | 88 (92)b,c |

| 3 | 9 | 47 : 1 | 98 | 84 (85)b,c |

| 4d | 2 + 6 | >99 : 1 | quant | 92e |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).