Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

05 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Preliminaries and Definitions

- (b)

-

It is significant to observe that several functions which are not locally Lipschitz in Euclidean space setting, can be locally Lipschitz in the setting of Hadamard manifolds. For instance, let us consider the set defined as:Consider the real-valued function defined as follows:for every . One can verify that the function is not a locally Lipschitz function on the set in the usual Euclidean sense. However, can be considered as a Hadamard manifold by endowing it with the Riemannian metric given bywhere the symbol denotes the Euclidean inner product on andThen, it can be verified that the function is locally Lipschitz with rank 1 on the set in the setting of manifolds (see, for instance, [12]).

- (a)

- The Clarke subdifferential is a nonempty, convex, compact subset of . Moreover, for , and is upper semicontinuous at y.

- (b)

- For every w in we have

- (c)

- If and are sequences in and the tangent bundle , respectively, such that for every , . Further, let be a weak*-cluster point of . Then, we have .

- (a)

-

The system of inequalities:has a solution ;

- (b)

-

The following equation:has a solution , , , such that , .

3. Constraint Qualifications and Necessary Optimality Criteria for (NMMPEC)

- (b)

- The index set is termed as the degenerate index set at the point . The strict complementarity condition is said to be satisfied at provided that .

- (b)

- One can observe the fact that every index set that is defined above is dependent on the particular choice of . Nevertheless, in the remaining part of the article, we shall not indicate such dependence explicitly when it will be easily perceivable from the context.

- (b)

- In case , then (NMMPEC) reduces to a nonsmooth single-objective optimization problem with equilibrium constraints. Then

- (b)

- If , then Definition 9 generalizes the definition of linearizing cone given by Singh and Mishra [36] from smooth multiobjective (MPEC) to nonsmooth multiobjective (MPEC).

- 2.

- Theorem 2 generalizes Theorem 3.2 of Maeda [27] from smooth multiobjective programming problems to (NMMPEC) and extends it from to the framework of Hadamard manifolds.

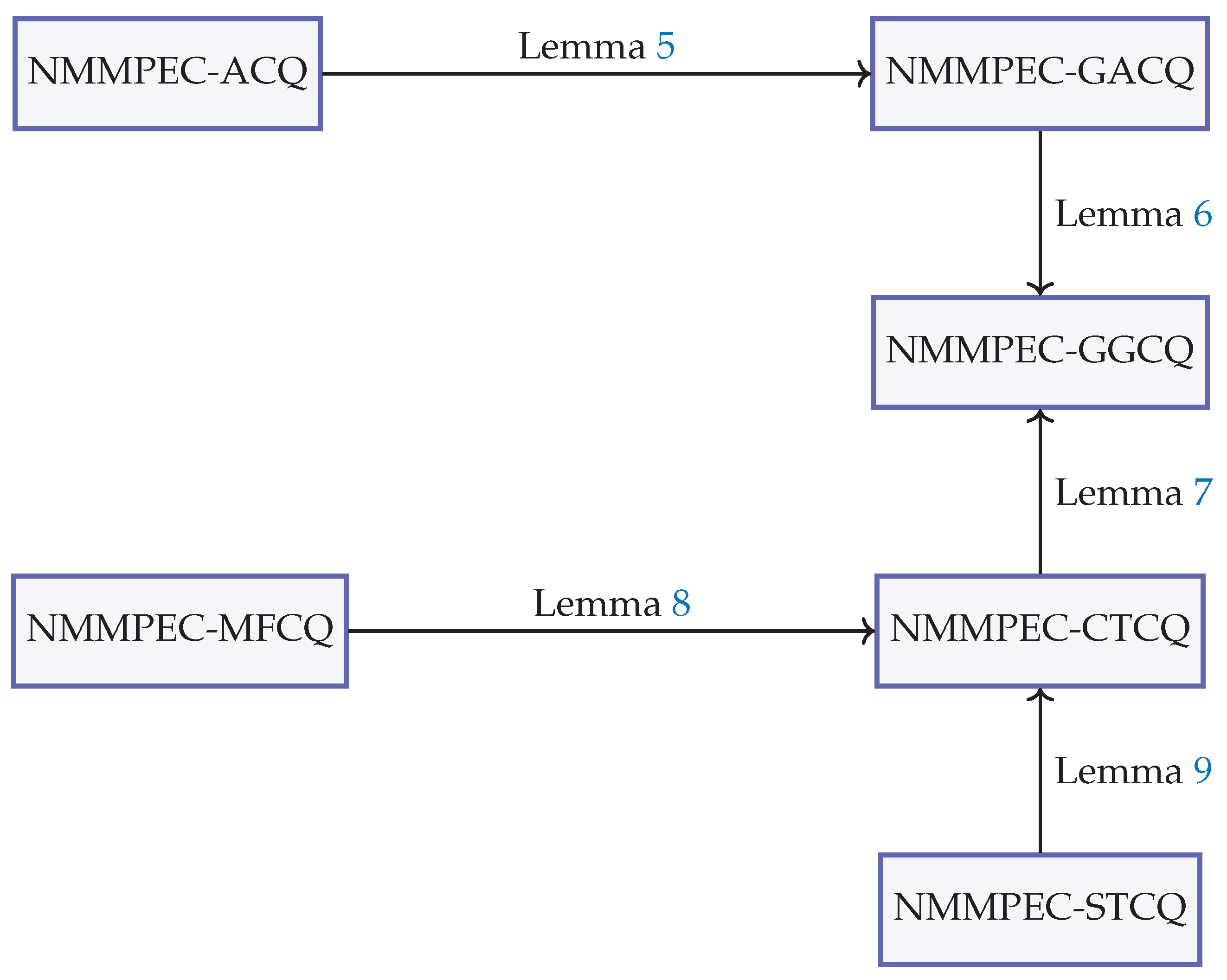

4. Constraint Qualifications for (NMMPEC) in the Setting of Hadamard Manifolds

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Consent for Publication

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmadian, S.; Tang, X.; Malki, H.A.; Han, Z. Modelling cyber attacks on electricity market using mathematical programming with equilibrium constraints. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 27376–27388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardali, A.A.; Movahedian, N.; Nobakhtian, S. Optimality conditions for nonsmooth mathematical programs with equilibrium constraints using convexificators. Optimization 2014, 65, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacák, M.; Bergmann, R.; Steidl, G.; Weinmann, A. A second order nonsmooth variational model for restoring manifold-valued images. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2016, 38, A567–A597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, A. Generalized monotonicity and convexity for locally Lipschitz functions on Hadamard manifolds. Differ. Geom. Dyn. Syst. 2013, 15, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Belkin, M.; Niyogi, P. Semi-supervised learning on Riemannian manifolds. Mach. Learn. 2004, 56, 209–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, R.; Herzog, R. Intrinsic formulation of KKT conditions and constraint qualifications on smooth manifolds. SIAM J. Optim. 2019, 29, 2423–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumal, N.; Mishra, B.; Absil, P.-A.; Sepulchre, R. Manopt: A MATLAB toolbox for optimization on manifolds. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar]

- Britz, W.; Ferris, M.; Kuhn, A. Modeling water allocating institutions based on multiple optimization problems with equilibrium constraints. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 46, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Existence results for vector variational inequality problems on Hadamard manifolds. Optim. Lett. 2020, 14, 2395–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Florian, M. The nonlinear bilevel programming problem: Formulations, regularity and optimality conditions. Optimization 1995, 32, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colao, V.; López, G.; Marino, G.; Martín-Márquez, V. Equilibrium problems in Hadamard manifolds. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2012, 388, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O.P. Proximal subgradient and a characterization of Lipschitz function on Riemannian manifolds. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2006, 313, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O.P.; Louzeiro, M.S.; Prudente, L. Gradient method for optimization on Riemannian manifolds with lower bounded curvature. SIAM J. Optim. 2019, 29, 2517–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, P.T.; Moeller, J.; Phillips, J.M.; Venkatasubramanian, S. Horoball hulls and extents in positive definite space. In Algorithms and Data Structures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 386–398. [Google Scholar]

- Flegel, M.L.; Kanzow, C. Abadie-type constraint qualification for mathematical programs with equilibrium constraints. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2005, 124, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegel, M.L.; Kanzow, C. On the Guignard constraint qualification for mathematical programs with equilibrium constraints. Optimization 2005, 54, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Upadhyay, B.B.; Stancu-Minasian, I.M. Constraint qualifications for multiobjective programming problems on Hadamard manifolds. Aust. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2023, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Upadhyay, B.B.; Stancu-Minasian, I.M. Pareto efficiency criteria and duality for multiobjective fractional programming problems with equilibrium constraints on Hadamard manifolds. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohs, P.; Hosseini, S. ϵ-subgradient algorithms for locally Lipschitz functions on Riemannian manifolds. Adv. Comput. Math. 2016, 42, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker, P.T.; Pang, J.S. Existence of optimal solutions to mathematical programs with equilibrium constraints. Oper. Res. Lett. 1988, 7, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, M.A. On constraint qualifications for multiobjective programming problems with equilibrium constraints. J. Math. Ext. 2018, 12, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.; Huang, W.; Yousefpour, R. Line search algorithms for locally Lipschitz functions on Riemannian manifolds. SIAM J. Optim. 2018, 28, 596–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Pouryayevali, M.R. Generalized gradients and characterization of epi-Lipschitz sets in Riemannian manifolds. Nonlinear Anal. 2011, 74, 3884–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkhaneei, M.M.; Mahdavi-Amiri, N. Nonconvex weak sharp minima on Riemannian manifolds. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2019, 183, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Zhou, L.W.; Huang, N.J. Gap functions and descent methods for equilibrium problems on Hadamard manifolds. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2016, 17, 807–826. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.; Hiai, F.; Lawson, J. Nonhomogeneous Karcher equations with vector fields on positive definite matrices. Eur. J. Math. 2021, 7, 1291–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T. Constraint qualifications in multiobjective optimization problems: Differentiable case. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 1994, 80, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Upadhyay, B.B. Pseudolinear Functions and Optimization; Chapman and Hall/CRC: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Papa Quiroz, E.A.; Quispe, E.M.; Oliveira, P.R. Steepest descent method with a generalized Armijo search for quasiconvex functions on Riemannian manifolds. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2009, 341, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa Quiroz, E.A.; Oliveira, P.R. Full convergence of the proximal point method for quasiconvex functions on Hadamard manifolds. ESAIM Control Optim. Calc. Var. 2012, 18, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa Quiroz, E.A.; Oliveira, P.R. Proximal point methods for quasiconvex and convex functions with Bregman distances on Hadamard manifolds. J. Convex Anal. 2009, 16, 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pennec, X. Manifold-valued image processing with SPD matrices. In Riemannian Geometric Statistics in Medical Image Analysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 75–134. [Google Scholar]

- Ralph, D. Mathematical programs with complementarity constraints in traffic and telecommunications networks. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2008, 366, 1973–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapcsák, T. Smooth Nonlinear Optimization in ; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, O. On constraint qualifications in nonsmooth optimization. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2004, 121, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.V.K.; Mishra, S.K. On multiobjective mathematical programming problems with equilibrium constraints. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2019, 7, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treanţă, S.; Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Nonlaopon, K. Optimality conditions for multiobjective mathematical programming problems with equilibrium constraints on Hadamard manifolds. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, L.T.; Tam, D.H. Optimality conditions and duality for multiobjective semi-infinite programming on Hadamard manifolds. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 2022, 48, 2191–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udrişte, C. Convex Functions and Optimization Methods on Riemannian Manifolds; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A. Optimality conditions and duality for multiobjective semi-infinite optimization problems with switching constraints on Hadamard manifolds. Positivity 2024, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A. On constraint qualifications for mathematical programming problems with vanishing constraints on Hadamard manifolds. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2023, 200, 794–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Kanzi, N. Constraint qualifications and optimality conditions for nonsmooth multiobjective mathematical programming problems with vanishing constraints on Hadamard manifolds via convexificators. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2025, 542, 128873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Kanzi, N.; Soroush, H. Constraint qualifications for nonsmooth multiobjective programming problems with switching constraints on Hadamard manifolds. Bull. Malays. Math. Sci. Soc. 2024, 47, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Mishra, P.; Treanţă, S. Optimality conditions and duality for multiobjective semi-infinite programming problems on Hadamard manifolds using generalized geodesic convexity. RAIRO Oper. Res. 2022, 56, 2037–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Treanţă, S.; Yao, J.-C. Constraint qualifications and optimality conditions for multiobjective mathematical programming problems with vanishing constraints on Hadamard manifolds. Mathematics 2024, 12, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Treanţă, S. Efficiency conditions and duality for multiobjective semi-infinite programming problems on Hadamard manifolds. J. Glob. Optim. 2024, 89, 723–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Stancu-Minasian, I.M. Second-order optimality conditions and duality for multiobjective semi-infinite programming problems on Hadamard manifolds. Asia-Pac. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 41, 2350019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Treanţă, S. Optimality conditions and duality for nonsmooth multiobjective semi-infinite programming problems with vanishing constraints on Hadamard manifolds. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2024, 531, 127785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Treanţă, S. Constraint qualifications and optimality criteria for nonsmooth multiobjective programming problems on Hadamard manifolds. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2024, 200, 794–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, B.B.; Ghosh, A.; Treanţă, S. Optimality conditions and duality for nonsmooth multiobjective semi-infinite programming problems on Hadamard manifolds. Bull. Iran. Math. Soc. 2023, 49, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.J. Necessary and sufficient optimality conditions for mathematical programs with equilibrium constraints. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2005, 307, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Lin, G.H.; Yang, X. Constraint qualifications and proper Pareto optimality conditions for multiobjective problems with equilibrium constraints. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2018, 176, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).