Submitted:

01 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

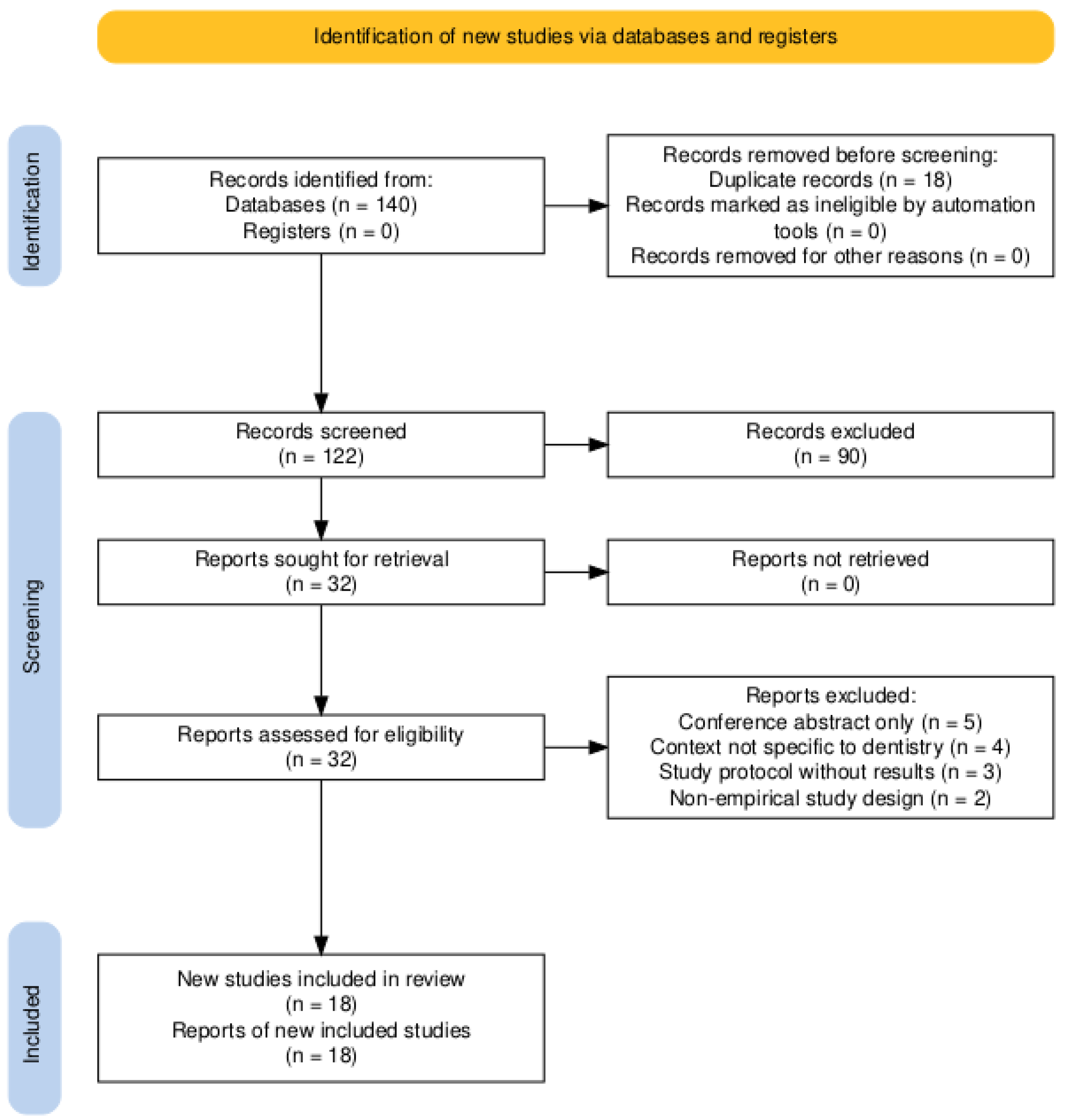

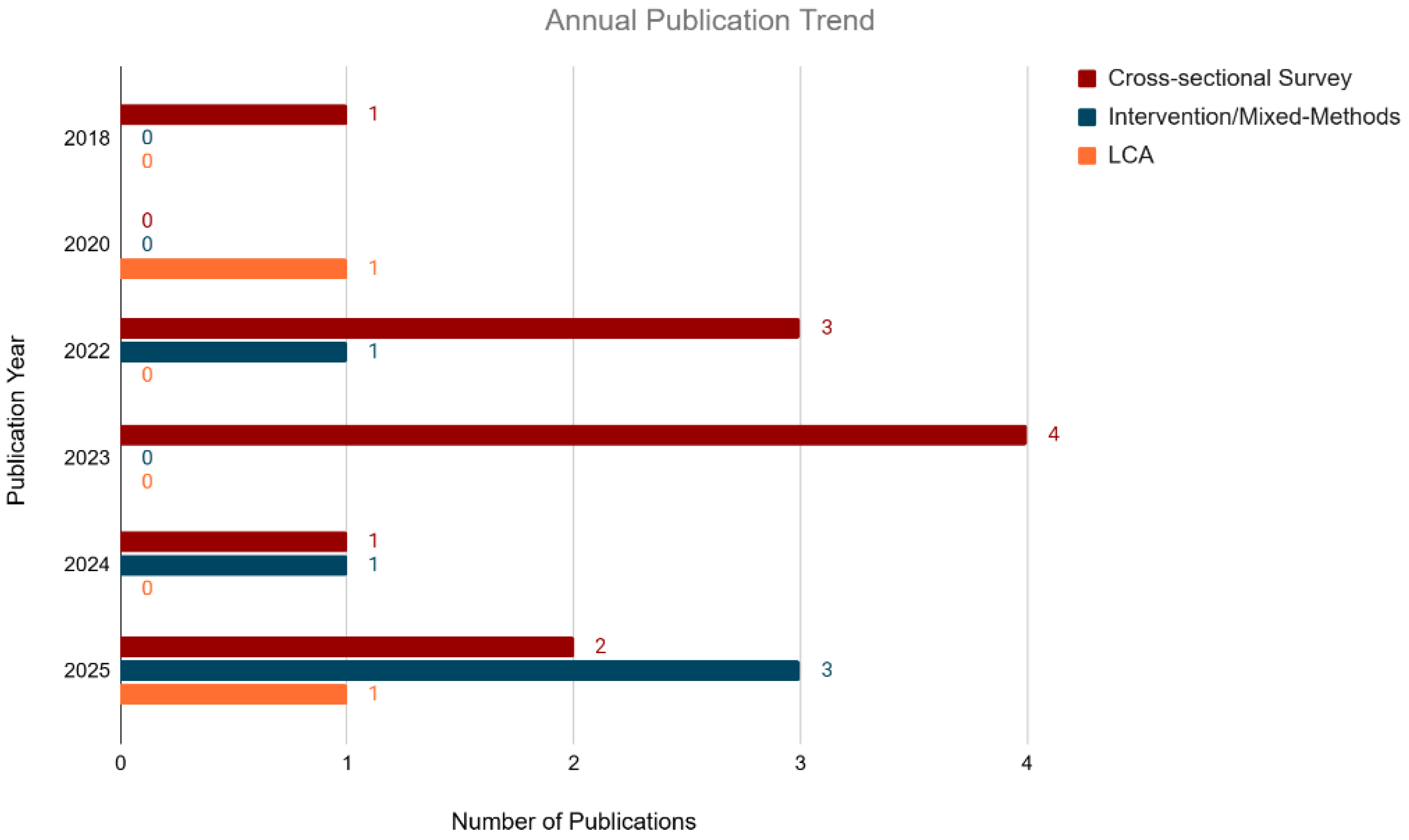

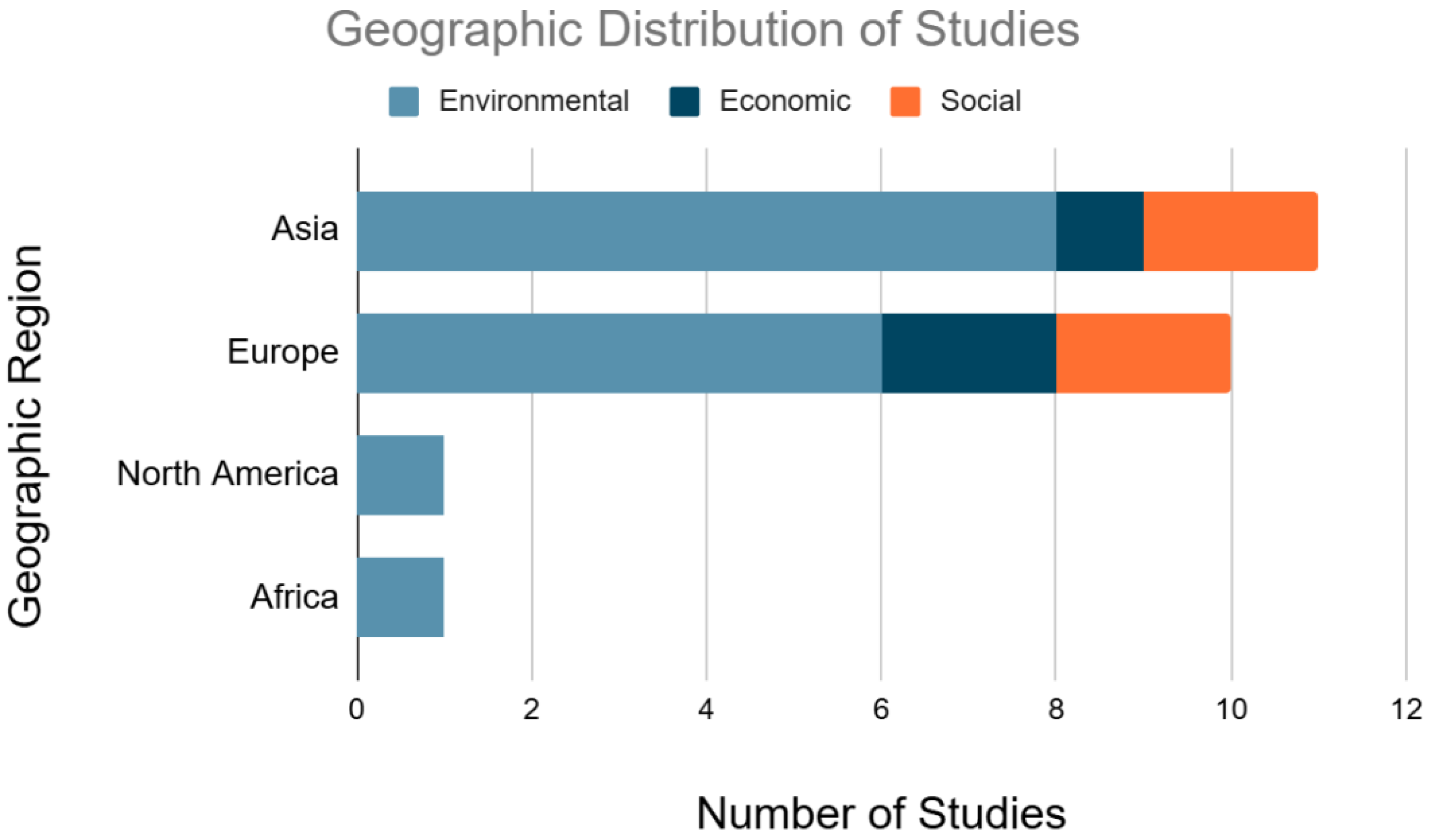

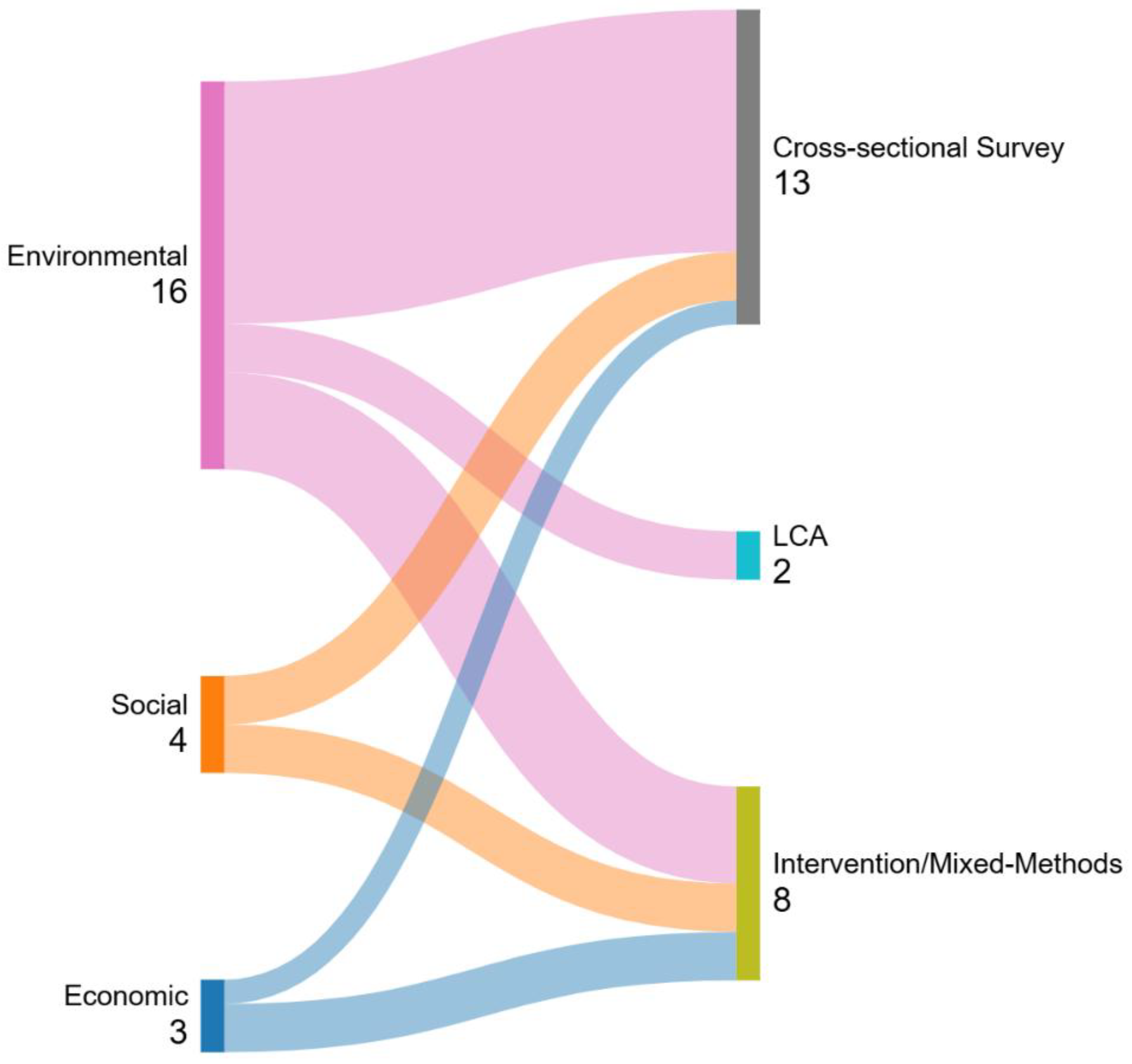

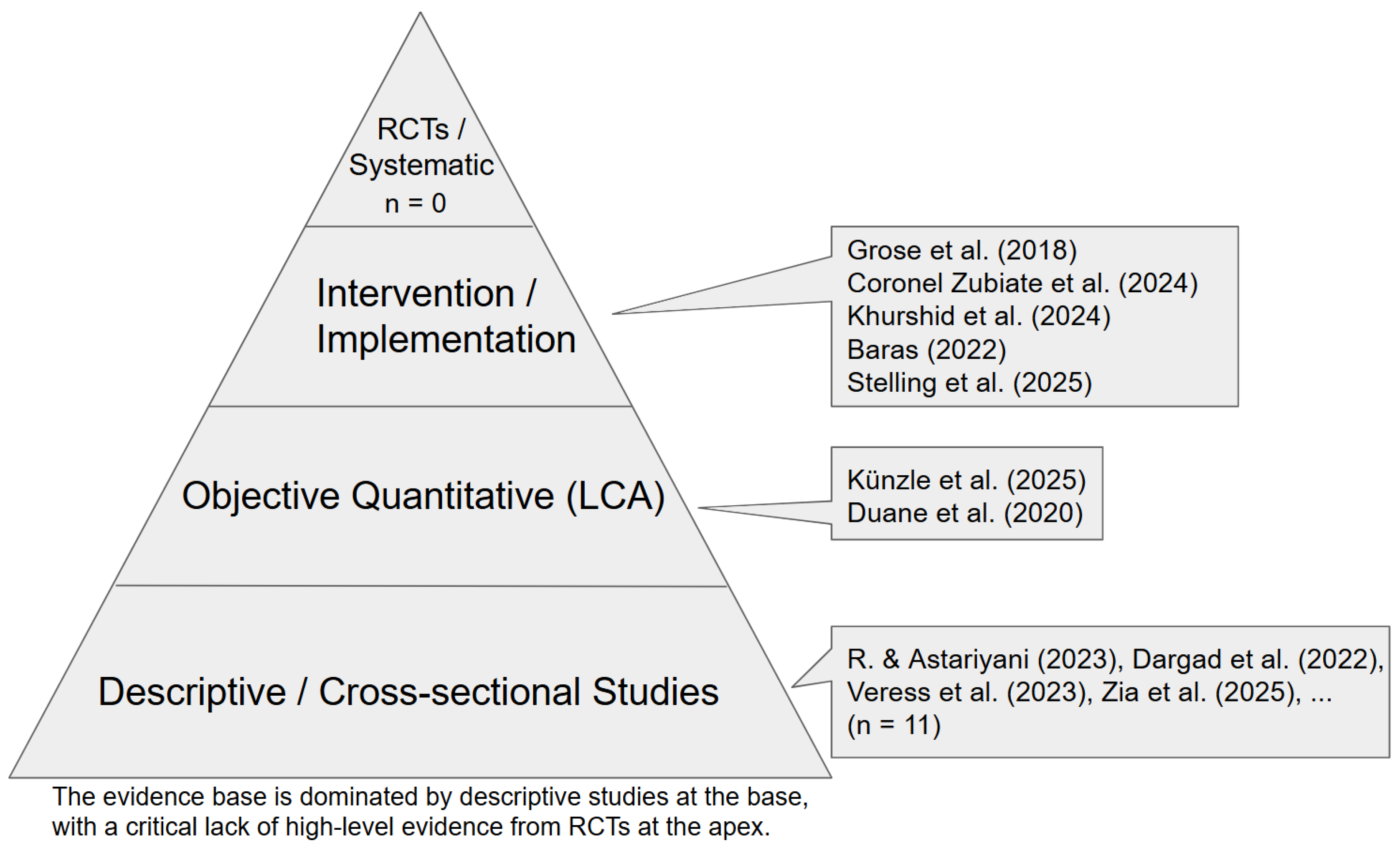

Background: While sustainability is increasingly recognized as a priority in dentistry, it remains unclear what the map of the available empirical evidence to guide this transition looks like in terms of its breadth, depth, and quality. This systematic review provides a critical appraisal of the dental sustainability literature to identify its core characteristics, expose critical research gaps, and propose an evidence-based agenda for the future. Methods: Following PRISMA guidelines, a systematic search was conducted across PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar for empirical studies published between 2010 and 2025. Data on study design, geographic origin, sustainability dimensions (environmental, economic, social), and key findings were extracted. A narrative synthesis was performed, focusing on dimensional balance, methodological rigor, and thematic patterns. Results: From 140 initial records, 18 studies were included. The findings reveal a field in its infancy, characterized by three profound imbalances. First, a dimensional imbalance: research is overwhelmingly focused on Environmental sustainability (89% of studies), with scant attention paid to Economic (17%) and Social (22%) dimensions. Second, a methodological imbalance: the evidence base is dominated by low-level descriptive evidence, primarily cross-sectional surveys (61%), with a notable scarcity of intervention studies or objective quantitative research like Life Cycle Assessments (11%). Third, a geographic imbalance: research is concentrated in specific regions, with limited evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Publication trends show a marked increase in interest since 2022. Conclusions: The map of the current empirical evidence for sustainability in dentistry reveals a landscape that is insufficient to guide robust policy or practice change. It lacks the economic analysis, social inquiry, and high-quality methodological approaches necessary for a truly evidence-based transformation. This review presents a detailed research roadmap, prioritizing a shift towards more balanced, methodologically rigorous, and globally representative research to mature the field from a state of describing problems to one of testing solutions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Urgency

1.2. Conceptual Framework

1.3. Knowledge Gaps

1.4. Objectives

- To systematically map and quantify the distribution of empirical research across the environmental, economic, and social dimensions of the Triple Bottom Line framework, thereby providing a clear picture of the field's current focus and identifying any significant imbalances.

- To conduct a critical appraisal of the methodological landscape by categorizing the predominant research designs and assessing the prevalence of validated versus non-validated measurement tools. This will evaluate the overall quality and strength of the existing evidence base.

- To formulate a targeted, evidence-based research agenda based on the synthesis of the identified dimensional, methodological, and measurement gaps, with the aim of guiding future research towards greater rigor, balance, and practical impact.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Guidance

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

- inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. Studies were included if they were original empirical research published in English between 2010-2025, and focused on at least one dimension of sustainability within a dental context. Non-empirical articles, studies without a specific dental focus, and non-English publications were excluded.

- the study selection process was executed. All retrieved records were imported into a reference management software for deduplication. Two reviewers then independently screened titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria. Potentially relevant articles advanced to a full-text screening, which was also conducted independently by both reviewers. Any disagreements at either stage were resolved through discussion and consensus, with a third reviewer available for arbitration if needed.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.5. Quality Assessment (Risk of Bias)

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Publication Trends

3.2. Geographic Distribution of Research

3.3. Thematic and Methodological Landscape

3.3.1. Dimensional Imbalance

3.3.2. Methodological Immaturity

3.4. Key Findings by Study Design and Quality of Evidence

- Descriptive Evidence from Cross-Sectional Surveys (n=11, 61%):

- Objective Quantification from Life Cycle Assessments (n=2, 11%):

- Emerging Evidence from Intervention and Implementation Studies (n=5, 28%):

3.5. Methodological Quality and Limitations

- Predominance of Self-Reported Data: With over 60% of studies relying on surveys, the evidence base is heavily skewed by self-reported data. This introduces a high risk of social desirability bias (participants reporting what they believe is the "correct" or desirable answer) and recall bias. This reliance limits the validity of the findings, as stated attitudes and practices may not reflect real-world behaviors.

- Lack of Standardized and Validated Instruments: A significant weakness identified is the scarcity of standardized measurement tools. Most KAP surveys employed ad-hoc, unvalidated questionnaires. This was explicitly identified as a major research gap [22], whose work focused on the psychometric validation of a KAP tool. Without common, validated instruments, it is nearly impossible to compare findings across studies, conduct meta-analyses, or reliably track progress in the field over time.

- Limited Generalizability: Many studies, particularly the interventional and implementation research, were conducted in single-institution settings (e.g., a single dental school or clinic), as noted in Table 1 for studies like [14,18]. While providing valuable proof-of-concept, the findings from these studies may not be generalizable to different cultural, economic, or healthcare contexts. The field currently lacks the multi-site, large-scale studies needed to generate broadly applicable evidence.

4. Discussion

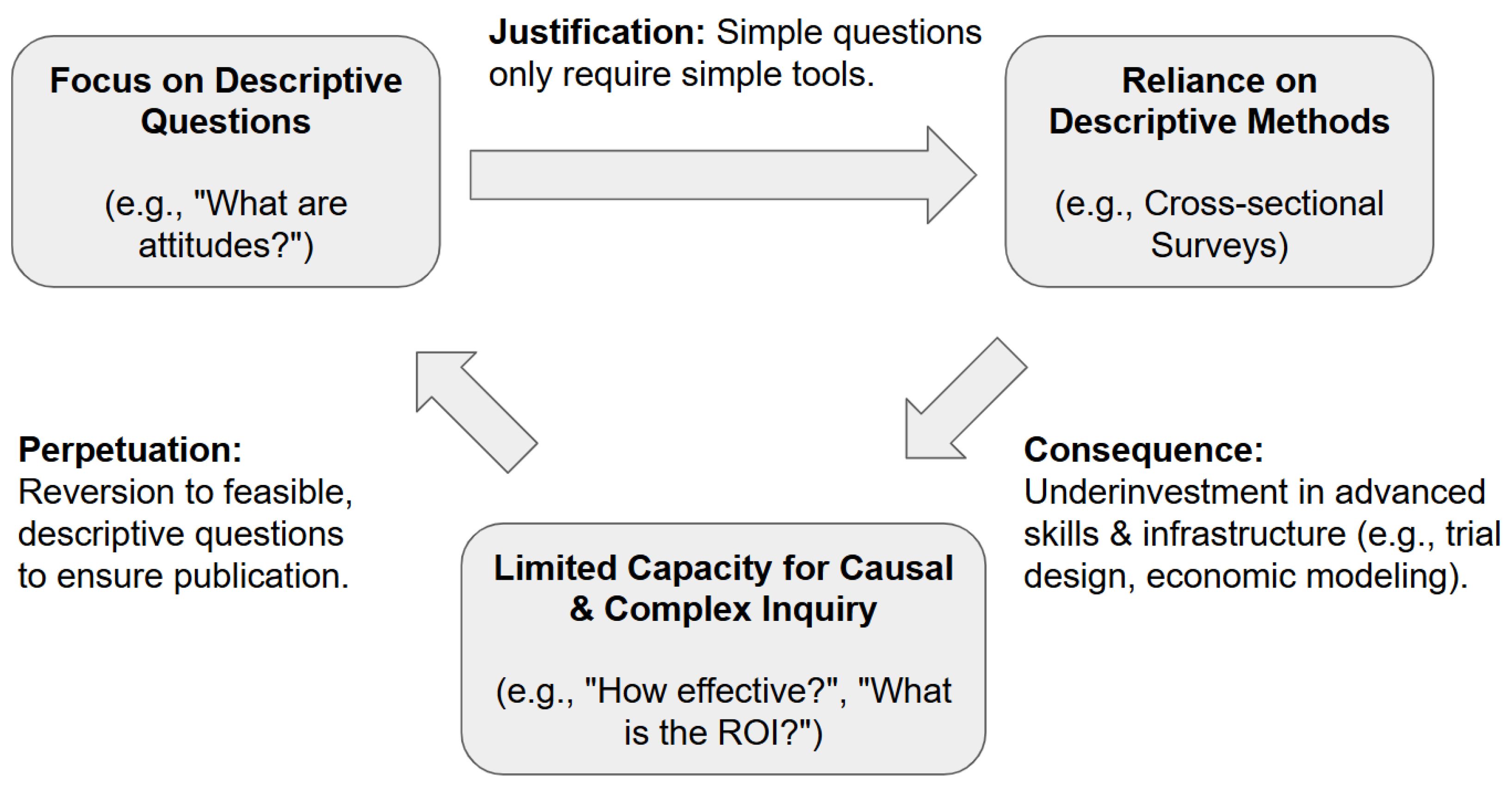

4.1. The Self-Reinforcing Cycle of Low-Level Evidence

4.2. Comparison with Existing Literature and Contribution of This Review

4.3. Implications for Policy, Education, and Practice

- For Practitioners and Clinic Managers: The lack of economic data is a major barrier to adoption. Without clear evidence of return on investment or long-term cost savings, transitioning to sustainable—and often more expensive—materials and equipment remains a financially risky proposition. The findings of this review should caution practitioners against adopting trends without first demanding robust evidence of their environmental, economic, and clinical efficacy.

- For Dental Educators: The documented knowledge gaps among students [19,20], coupled with strong support from both students and faculty for curriculum integration [18], underscore the urgent need for curriculum reform. However, this reform must be evidence-based. It is no longer sufficient to teach "green dentistry" as a set of aspirational principles. Curricula must be developed to teach sustainability as a science, grounded in concepts from LCA, health economics, and implementation science. The development of validated competency assessment tools, building on the work of [22], is a critical first step.

- For Policymakers and Professional Associations: Given that even foundational practices like waste management are not universally optimized [21], this review suggests that the current evidence base is likely insufficient to support strong, specific policy mandates. Policymakers should prioritize funding research that addresses the gaps identified here, particularly multi-site intervention studies and economic analyses, before issuing widespread guidelines.

4.4. A Proposed Research Agenda for the Future

4.5. Strengths and Limitations of This Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBL | Triple Bottom Line |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| KAP | Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

Appendix A

| Database | Search Terms Combination |

|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | ("Dentistry"[MeSH Terms] OR "Oral Health"[MeSH Terms] OR "dental practice"[Title/Abstract]) `AND` `("Sustainability"[Title/Abstract] OR "green dentistry"[Title/Abstract] OR "Environmental Sustainability"[MeSH Terms] OR "Conservation of Natural Resources"[MeSH Terms])` |

| Web of Science | TS=("dentistry" OR "dental" OR "oral health") `AND` `TS=("sustainability" OR "sustainable" OR "green" OR "eco-friendly" OR "environmental impact")` |

References

- Karliner, J.; Slotterback, S.; Boyd, R.; Ashby, B.; Steele, K. Health Care's Climate Footprint: How the Health Sector Contributes to the Global Climate Crisis and Opportunities for Action; Health Care Without Harm: Reston, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Duane, B.; Harford, S.; Steinbach, I.; Stancliffe, R. Environmentally sustainable dentistry: Energy use within the dental practice. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.; Mulligan, S.; Fuzesi, S.; Brookes, Z.; Jamous, I.; Loukaidis, M.; et al. The environmental sustainability of oral healthcare: A position paper by the Sustainable Dentistry Special Interest Group. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 230, 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mulimani, P. Green dentistry: The art and science of sustainable practice. Br. Dent. J. 2017, 222, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, M.E.; Teisberg, E.O. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargad, P.; Shetiya, S.H.; Agarwal, D. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding green dentistry amongst the alumni of a private dental college in Pune, Maharashtra – A questionnaire study. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2022, 28, 021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. ; Astariyani. Awareness, attitude and practice towards green dentistry among the postgraduate dental students of D.J College of Dental Sciences and Research Modinagar. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2023, 5, 1517.

- Baird, H.M.; Mulligan, S.; Webb, T.L.; Baker, S.R.; Martin, N. Exploring attitudes towards more sustainable dentistry among adults living in the UK. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 233, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, M.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Alqahtani, N.; Alqahtani, A.; Vohra, F.; Abduljabbar, T. Incorporation of recycled PMMA particles into heat-cured denture base materials for improved sustainability. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 943–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veress, S.; Kerekes-Máthé, B.; Szekely, M. Environmentally friendly behavior in dentistry. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2023, 96, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, Z.; Alqurashi, H.; Ashi, H. Advancing environmental sustainability in dentistry and oral health. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2024, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künzle, A.; Frank, M.; Paris, S. Environmental impact of a tooth extraction: Life cycle analysis in a university hospital setting. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2025, 53, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane, B.; Borglin, L.; Pekarski, S.; Saget, S.; Duncan, H.F. Environmental sustainability in endodontics: A life cycle assessment (LCA) of a root canal treatment procedure. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelling, D.; Brown, J.; Burford, B.; Blaylock, Z.; Vance, G. Valuing and retaining the dental workforce: A mixed-methods exploration of workforce sustainability in the North East of England. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 803–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, H.; Marghalani, A.A.; Shinawi, A.M.J.; Gaffar, B. Exploring the perception of dental undergraduate students and faculty on environmental sustainability in dentistry: A cross sectional survey in 26 dental schools in Saudi Arabia. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Țâncu, A.M.C.; Imre, M.; Iosif, L.; Pițuru, S.M.; Pantea, M.; Sfeatcu, R.; et al. Is sustainability part of the drill? Examining knowledge and awareness among dental students in Bucharest, Romania. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Fisal, S.; Rohani, M.M.; Aziz, A.A.; Hussain, N.H.N.; Fuad, M.D.F. Knowledge, awareness, and practices of green dentistry among dental undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study. J. Dent. Educ. 2025, 89, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronel Zubiate, F.T.; Farje-Gallardo, C.A.; Rojas de la Puente, E.E. Environmental impact of waste in dental care: Educational strategies to promote environmental sustainability. Vide. Tehnoloģija. Resursi (Environment. Technology. Resources) 2024, 2, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, N.; Doss, J.G.; Danaee, A.; John, J.; Panezai, J. Psychometric analysis of a KAP questionnaire on green dentistry using PLS-SEM and EFA: A pilot study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 745–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baras, A. Acting for the health of the planet by integrating an eco-responsible approach in dental practices: A French experiment in a dental office. Int. Health Trends Perspect. 2022, 2, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.; Varici, İ. The use of the sustainability balanced scorecard method in performance measurement: An application in the faculty of dentistry. Muhasebe ve vergi uygulamaları dergisi (Journal of Accounting and Tax Applications) 2022, 15, 606. [Google Scholar]

- Grose, J.; Burns, L.; Mukonoweshuro, R.; Richardson, J.; Mills, I.G.; Nasser, M.; Moles, D.R. Developing sustainability in a dental practice through an action research approach. Br. Dent. J. 2018, 225, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, S.; Dhaimade, P.A. Green dentistry: A systematic review of ecological dental practices. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1345–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane, B.; Steinbach, I.; Stancliffe, R.; Al Yazeedi, A.; Lyne, A.; Bashford, J.; et al. Sustainability in dentistry: A multifaceted approach needed. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors, Year | Methods | Sample | Key Findings | Limitations / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. & Astariyani (2023) | Cross-sectional questionnaire study using a 10-item self-structured questionnaire. | n=135 postgraduate dental students at D.J. College of Dental Sciences and Research, India. | •High Awareness: ~80% of students were familiar with the term "green dentistry". •Low Implementation: Despite awareness, most students had not implemented sustainable strategies in their clinical practice. |

Abstract provided insufficient detail to identify specific methodological limitations. |

| Dargad et al. (2022) | Cross-sectional e-survey using a validated questionnaire with pilot testing. | n=310 responses from 900 invited alumni of a private dental college in Pune, India. | •Varied Knowledge: >60% correct on waste/sterilization, but <40% correct on energy efficiency. •High Compliance (Waste): 95.5% were registered with a biomedical waste disposal service. •Attitude-Practice Gap: Positive attitudes towards sustainability significantly exceeded practical implementation. |

Abstract did not report on response rate bias or other potential sampling limitations. |

| Veress et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional online survey with 50 questions across 6 sections. | n=98 dentists recruited via online platforms (location not specified). | •High Willingness: 99% were willing to take steps towards sustainability. •Favorable Attitude: 74.5% were favorable to an environmentally friendly practice, but specific behaviors (e.g., waste sorting) varied. |

The abstract does not list explicit methodological limitations beyond the need for general guidance. |

| Jamal et al. (2023) | Multi-institution cross-sectional survey. | Dental undergraduate students and faculty across 26 dental schools in Saudi Arabia. | •Found a strong positive perception and high level of support for integrating sustainability concepts into the dental curriculum among both students and faculty. | Relies on self-reported data; may not reflect actual curriculum content or teaching practices. |

| Baird et al. (2022) | Cross-sectional questionnaire study. | Adults living in the United Kingdom (patient perspective). | •Patients demonstrated positive attitudes and were generally supportive of their dentists adopting more sustainable practices. | Focuses on attitudes, not actual patient behavior (e.g., choosing a "green" dentist). |

| Fisal et al. (2025) | Cross-sectional study. | Dental undergraduate students. | •Revealed moderate levels of knowledge, awareness, and practices regarding green dentistry, indicating a clear gap in current education. | Single-institution study, limiting generalizability. |

| Țâncu et al. (2025) | Cross-sectional questionnaire. | Dental students at a university in Bucharest, Romania. | •Identified significant gaps in student knowledge regarding specific sustainable practices and the environmental impact of dentistry. | Context-specific to a single European country; findings may differ elsewhere. |

| Boukhris et al. (2025) | Survey-based waste analysis. | Dental practices. | •Provided a detailed analysis of dental waste streams and assessed the level of adherence to official waste management and disposal protocols. | Self-reported survey data on waste may differ from objective waste audits. |

| Zia et al. (2025) | Pilot psychometric analysis using PLS-SEM and EFA. | Dental school personnel and students in Karachi, Pakistan. | •Key Gap Addressed: Successfully developed and validated a KAP questionnaire for green dentistry. •Major Finding: Explicitly highlighted the scarcity of standardized and validated measurement instruments in this research field. |

Framed as a pilot study, suggesting findings are preliminary and require larger-scale validation. Sample size not reported in abstract. |

| Künzle et al. (2025) | Life-Cycle Analysis (LCA) based on ISO 14040/14044 guidelines. | A standard tooth extraction procedure performed in a university hospital setting. | •Objective Quantification: A single tooth extraction generates 4.9 kg of CO2-equivalent. •Identified Hotspots: Pinpointed the specific materials, energy consumption, and sterilization processes that are the main drivers of the environmental impact. |

As with all LCA studies, results are sensitive to the defined system boundaries and the quality of underlying data sources. |

| Duane et al. (2020) | Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA). | A standard root canal treatment procedure. | •Quantified the environmental impact of an endodontic procedure. •Identified specific areas (e.g., single-use instruments, energy use) as key environmental hotspots, providing a basis for targeted interventions. |

Study-specific context may limit direct comparison with other procedures or settings. |

| Hijazi et al. (2025) | Laboratory experimental study. | In-vitro setting. | •Feasibility Finding: Demonstrated that incorporating recycled Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) particles into new denture bases is technically feasible without significantly compromising key material properties. | Laboratory findings; clinical performance and long-term durability of recycled materials require further investigation. |

| Stelling et al. (2025) | Mixed-methods study (qualitative and quantitative). | Dental workforce in the North East of England. | •Social Dimension: Revealed a complex interplay of factors affecting workforce sustainability, including professional value, support systems, and working conditions, especially in underserved areas. | Region-specific findings; may not be generalizable to other healthcare systems. |

| Grose et al. (2018) | Mixed-methods action research. | A single dental practice in the UK. | •Implementation Success: Showed that a participatory action research approach is a feasible and effective method for developing and embedding sustainability practices at the clinic level. | Single-site case study, limiting generalizability of the specific interventions but not the approach. |

| Coronel Zubiate et al. (2024) | Mixed longitudinal educational intervention. | Dental students. | •Intervention Effectiveness: An educational program focused on the environmental impact of dental waste successfully improved students' awareness and knowledge over time. | Focuses on awareness, not long-term behavioral change in clinical practice. |

| Khurshid et al. (2024) | Action research implementation. | A dental practice setting. | •Provided a practical case study outlining the successful implementation of various environmental sustainability initiatives in a clinical setting. | Descriptive case study; lacks a control group to measure the impact against. |

| Baras (2022) | Implementation experiment. | A single dental practice in France. | •Successfully integrated an eco-responsible approach into daily clinical operations, demonstrating the real-world feasibility and process of such a transformation. | Single-site study; specific facilitators and barriers may be context-dependent. |

| Aydin & Varici (2022) | Case study applying a theoretical framework. | A university dental faculty. | •Framework Application: Proposed and applied the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard as a comprehensive tool for measuring environmental, economic, and social performance in a dental institution. | Primarily a conceptual application; empirical data on its effectiveness in driving change is not presented. |

| Identified Gap | High-Priority Research Question | Recommended Methodology | Rationale / Expected Impact |

| Economic Gap | What are the cost-effectiveness and ROI of key sustainability interventions (e.g., digital scanners vs. traditional impressions)? | Cost-Effectiveness Analysis; ROI Studies | To provide the "business case" required for practice owners to invest in sustainable technologies. |

| Methodological Gap (Impact) | What is the comparative environmental impact of common dental procedures (e.g., restorations, extractions)? | Standardized Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | To generate objective data for evidence-based prioritization of clinical interventions. |

| Methodological Gap (Effectiveness) | What implementation strategies are most effective for promoting adoption of evidence-based sustainability practices? | Cluster Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) | To move beyond describing the problem to rigorously testing solutions for practice change. |

| Social Gap | How do sustainability-focused changes impact patient satisfaction, clinical outcomes, and health equity? | Mixed-Methods Studies; Equity Analysis | To ensure sustainability enhances, rather than compromises, patient care and equitable access. |

| Measurement Gap | How can sustainability KAP and behaviors be reliably and validly measured across different settings? | Psychometric Validation Studies | To create a foundation of reliable and comparable data for robust synthesis and assessment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).