Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

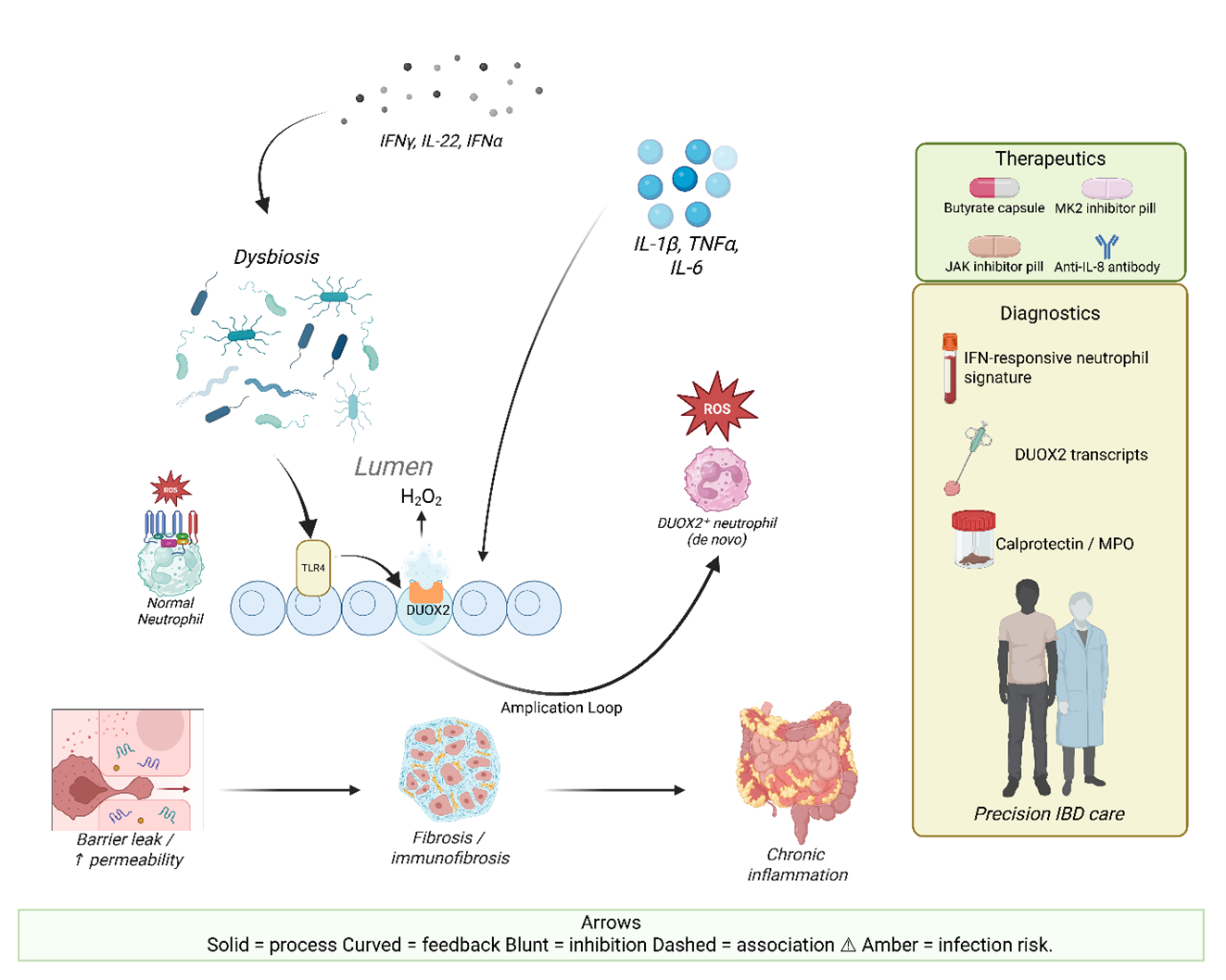

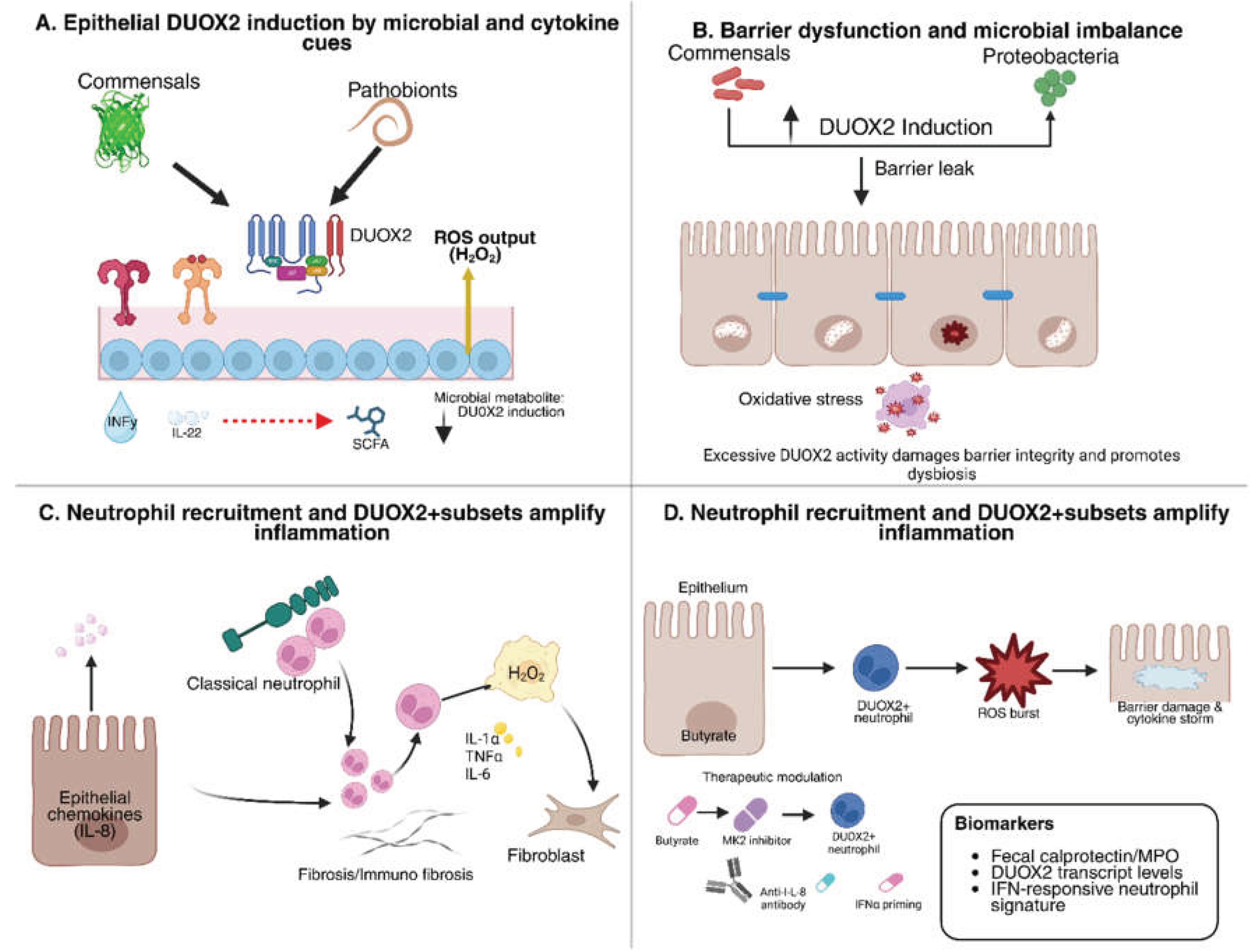

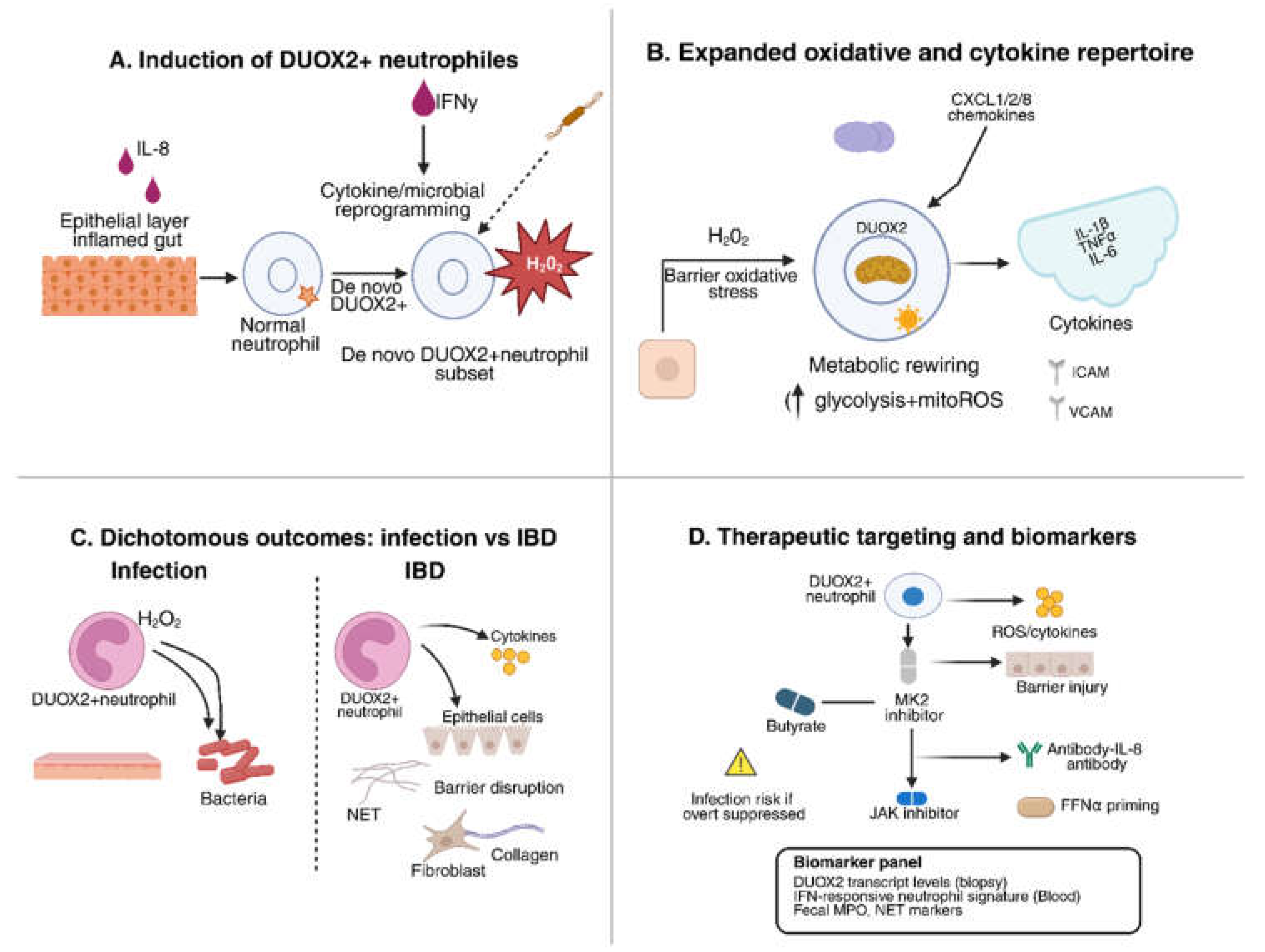

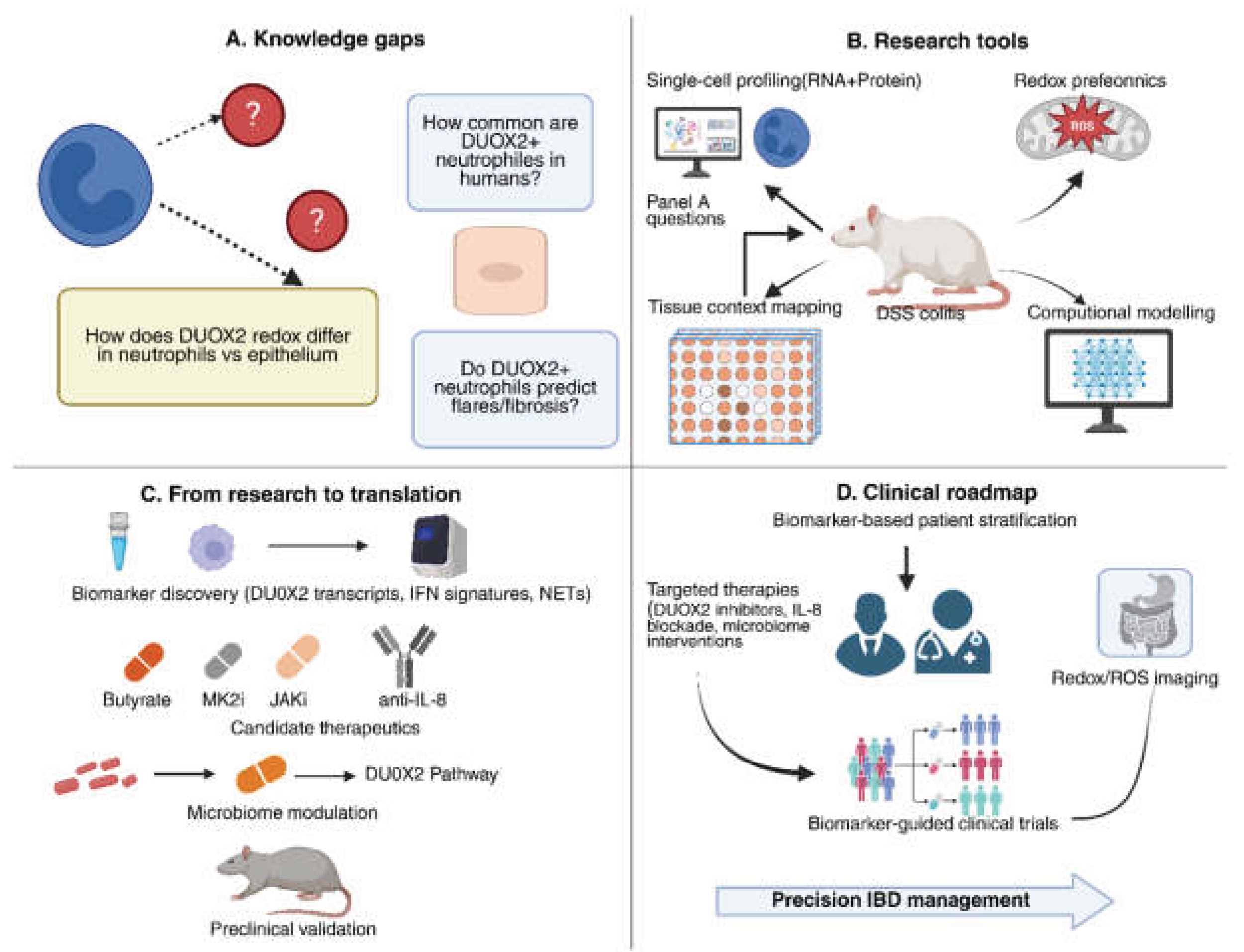

Advances in single-cell and spatial multi-omics technologies have transformed the understanding of neutrophils from short-lived effector cells to highly heterogeneous and transcriptionally plastic immune populations. Within the inflamed intestinal microenvironment, gradients of cytokines, oxygen tension, and microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids dynamically modulate neutrophil differentiation and function, shaping either tissue-protective or tissue-destructive phenotypes. Recent studies highlight the de novo expression of the NADPH oxidase enzyme DUOX2 in intestinal neutrophils as a pivotal mediator of redox signaling. DUOX2-derived reactive oxygen species activate epithelial and immune signaling cascades through NF-κB and p38 MAPK pathways, thereby amplifying inflammation, promoting barrier disruption, and sustaining microbial dysbiosis. Although this oxidative response enhances antimicrobial defense, it concurrently contributes to neutrophil extracellular trap (NET)-driven thrombo-inflammation and chronic tissue injury. Experimental evidence indicates that selective ablation of myeloid DUOX2 attenuates colitis, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic target. Emerging interventions that modulate this axis, including JAK/STAT inhibitors, CXCR2 antagonists, p38/MK2 inhibitors, and butyrate-based metabolic regulators, offer promising avenues to restore neutrophil homeostasis while maintaining host defense. Integrating single-cell transcriptomics, redox proteomics, and advanced imaging approaches will be essential for translating neutrophil plasticity into biomarker-guided and precision-based therapeutic strategies for durable mucosal healing in IBD.

Keywords:

- Neutrophils in IBD exhibit profound transcriptional plasticity driven by cytokines, hypoxia, dysbiosis, and metabolic cues.

- De novo DUOX2 expression equips intestinal neutrophils with extracellular H₂O₂ output that amplifies redox stress and inflammation.

- Epithelial–neutrophil DUOX2 coupling forms a feed-forward oxidative loop driving barrier dysfunction, dysbiosis, and mucosal injury.

- Single-cell and spatial multi-omics reveal disease-specific neutrophil states linked to therapy resistance and fibrotic remodeling in IBD.

- Targeting DUOX2, IL-8/CXCR2, JAK/IFN, NETosis, or metabolic pathways offers precision strategies to restore neutrophil homeostasis.

- What signals and epigenetic programs govern induction, stability, and heterogeneity of DUOX2⁺ neutrophils in human IBD lesions?

- How do DUOX2-derived extracellular ROS reshape epithelial, stromal, microbial, and immune networks across distinct gut niches?

- Can DUOX2⁺ neutrophils or interferon-primed neutrophil states serve as actionable biomarkers for relapse risk or therapy response?

- Which combinations of JAK inhibitors, CXCR2 blockade, NET inhibitors, or metabolic modulators best recalibrate neutrophil plasticity?

- How can DUOX2- or neutrophil-targeted therapies balance suppression of pathogenic inflammation with preserved antimicrobial defense?

1. Introduction

2. Neutrophil Plasticity in IBD and Tissue Contexts

2.1. Evidence for Neutrophil Heterogeneity and Plasticity in IBD

2.2. Microenvironmental Cues that Drive Tissue Reprogramming

2.3. Dichotomous Effector Programs: Protection Versus Pathology

| Effector Mechanism | Protective Role in IBD | Pathogenic Role in IBD | References |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) | Potent bactericidal activity that limits microbial dissemination; essential for early host defense. | Excessive ROS disrupts epithelial tight junctions, damages DNA/proteins, and induces apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells. | [36,37] |

| Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) | Trap and neutralize pathogens extracellularly, preventing microbial spread; can support wound repair and resolution. | Dysregulated NETosis increases gut permeability, induces IEC apoptosis, and destroys tight junctions, perpetuating inflammation. | [38,39] |

| Proteases (MMPs, elastase) | Release of lytic enzymes clears invading microbes and assists in matrix remodeling during repair. | Overproduction degrades epithelial adherens junctions, weakens barrier integrity, and contributes to mucosal injury. | [40,41] |

| Immune Cell Recruitment | Release of chemokines ensures rapid recruitment of immune cells, enabling pathogen clearance and resolution. | Excessive or chronic recruitment drives uncontrolled inflammation, amplifies cytokine cascades, and worsens epithelial damage. | [30,42] |

2.4. Disease-Relevant Subsets in the Gut Niche (Including DUOX2+ and CD177+ States)

3. DUOX2 in IBD Pathogenesis

3.1. Regulation of Epithelial DUOX2 Expression

3.2. DUOX2 as a Driver of Dysbiosis and Barrier Dysfunction

3.3. Crosstalk Between Epithelial DUOX2 and Immune-Mediated Pathology

4. De novo DUOX2 Expression in Neutrophils

4.1. Functional Consequences of Neutrophil DUOX2

4.2. Mechanistic Insights: Redox Diversification

4.3. Therapeutic Implications

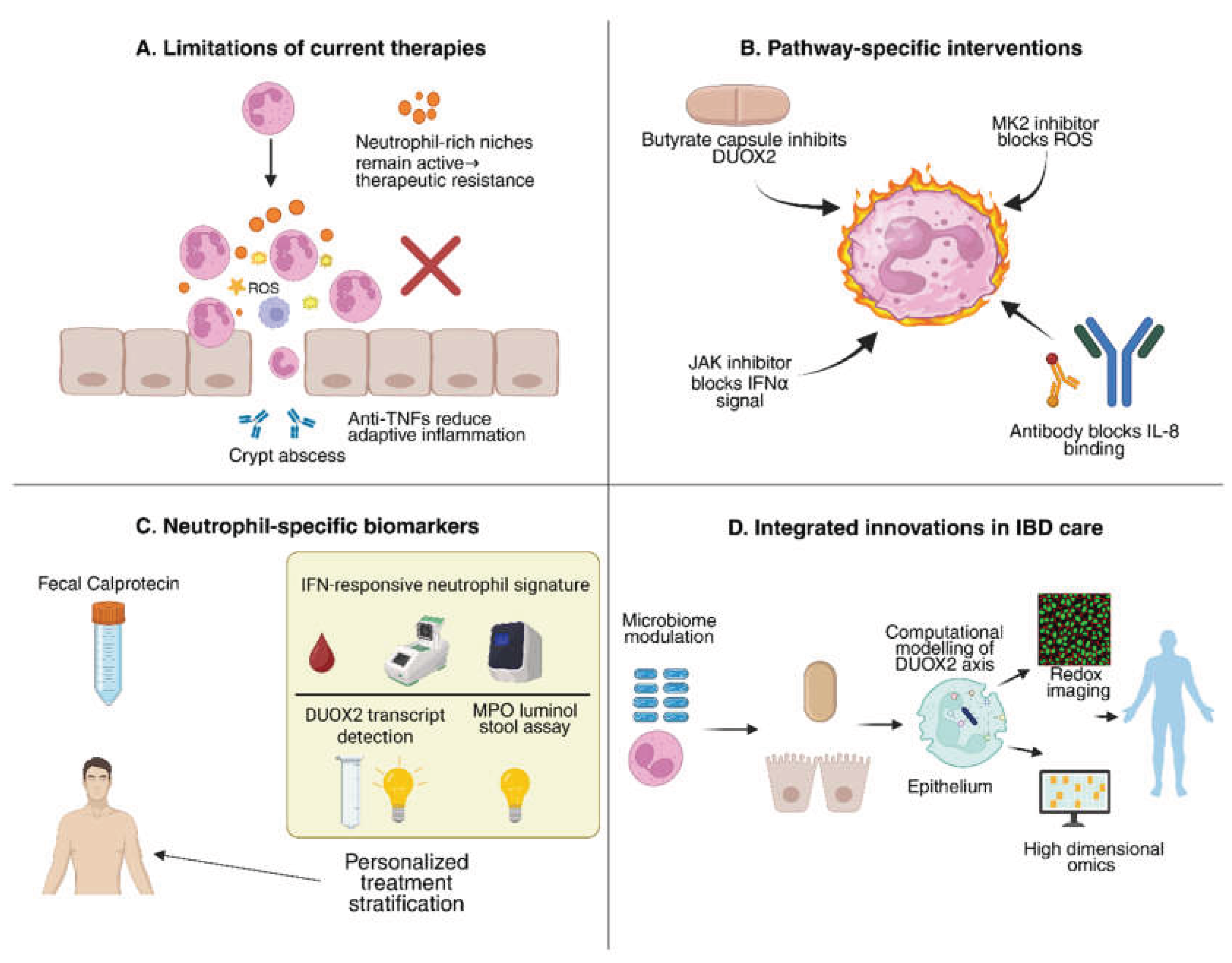

5. Targeting Neutrophils in IBD: Therapeutic and Diagnostic Frontiers

5.1. Why Current Therapies Leave a Neutrophil-Shaped Gap

5.2. Drugging Neutrophil Pathways: From Tractable Targets to Rational Combinations

5.3. Diagnostics and Monitoring: Beyond Calprotectin Toward Functional Neutrophil Readouts

5.4. Translational Roadmap

6. Future Directions and Research Gaps

7. Conclusions

Authorship Contribution Statement

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

Data and Materials Availability

References

- Kaplan, G.G.; Windsor, J.W. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, 18(1), 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F. Targeting immune cell circuits and trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Immunol. 2019, 20(8), 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordás, I.; Eckmann, L.; Talamini, M.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sandborn, W.J. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012, 380(9853), 1606–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Z.; van Sommeren, S.; Huang, H.; Ng, S.C.; Alberts, R.; Takahashi, A.; Ripke, S.; Lee, J.C.; Jostins, L.; Shah, T.; Abedian, S.; Cheon, J.H.; Cho, J.; Dayani, N.E.; Franke, L.; Fuyuno, Y.; Hart, A.; Juyal, R.C.; Juyal, G.; Kim, W.H.; Morris, A.P.; Poustchi, H.; Newman, W.G.; Midha, V.; Orchard, T.R.; Vahedi, H.; Sood, A.; Sung, J.Y.; Malekzadeh, R.; Westra, H.J.; Yamazaki, K.; Yang, S.K. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium International IBDGenetics Consortium Barrett, J.C.; Alizadeh, B.Z.; Parkes, M.; Bk, T.; Daly, M.J.; Kubo, M.; Anderson, C.A.; Weersma, R.K. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet. 2015, 47(9), 979–986. [Google Scholar]

- Jostins, L.; Ripke, S.; Weersma, R.K.; Duerr, R.H.; McGovern, D.P.; Hui, K.Y.; Lee, J.C.; Schumm, L.P.; Sharma, Y.; Anderson, C.A.; Essers, J.; Mitrovic, M.; Ning, K.; Cleynen, I.; Theatre, E.; Spain, S.L.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Goyette, P.; Wei, Z.; Abraham, C.; Achkar, J.P.; Ahmad, T.; Amininejad, L.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Andersen, V.; Andrews, J.M.; Baidoo, L.; Balschun, T.; Bampton, P.A.; Bitton, A.; Boucher, G.; Brand, S.; Büning, C.; Cohain, A.; Cichon, S.; D’Amato, M.; De Jong, D.; Devaney, K.L.; Dubinsky, M.; Edwards, C.; Ellinghaus, D.; Ferguson, L.R.; Franchimont, D.; Fransen, K.; Gearry, R.; Georges, M.; Gieger, C.; Glas, J.; Haritunians, T.; Hart, A.; Hawkey, C.; Hedl, M.; Hu, X.; Karlsen, T.H.; Kupcinskas, L.; Kugathasan, S.; Latiano, A.; Laukens, D.; Lawrance, I.C.; Lees, C.W.; Louis, E.; Mahy, G.; Mansfield, J.; Morgan, A.R.; Mowat, C.; Newman, W.; Palmieri, O.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Potocnik, U.; Prescott, N.J.; Regueiro, M.; Rotter, J.I.; Russell, R.K.; Sanderson, J.D.; Sans, M.; Satsangi, J.; Schreiber, S.; Simms, L.A.; Sventoraityte, J.; Targan, S.R.; Taylor, K.D.; Tremelling, M.; Verspaget, H.W.; De Vos, M.; Wijmenga, C.; Wilson, D.C.; Winkelmann, J.; Xavier, R.J.; Zeissig, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, C.K.; Zhao, H. International IBDGenetics Consortium, (.I.I.B.D.G.C.).; Silverberg, M.S.; Annese, V.; Hakonarson, H.; Brant, S.R.; Radford-Smith, G.; Mathew, C.G.; Rioux, J.D.; Schadt, E.E.; Daly, M.J.; Franke, A.; Parkes, M.; Vermeire, S.; Barrett, J.C.; Cho, J.H. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2012, 491(7422), 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, A.; Inoue, R.; Inatomi, O.; Bamba, S.; Naito, Y.; Andoh, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018, 11(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsialis, V.; Wall, S.; Liu, P.; Ordovas-Montanes, J.; Parmet, T.; Vukovic, M.; Spencer, D.; Field, M.; McCourt, C.; Toothaker, J.; Bousvaros, A. Boston Children’s Hospital Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center Brigham Women’s Hospital Crohn’s Colitis Center Shalek, A.K.; Kean, L.; Horwitz, B.; Goldsmith, J.; Tseng, G.; Snapper, S.B.; Konnikova, L. Single-Cell Analyses of Colon and Blood Reveal Distinct Immune Cell Signatures of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 159(2), 591–608.e10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kolaczkowska, E.; Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013, 13(3), 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidler, M.A.; Leach, S.T.; Day, A.S. Fecal S100A12 and fecal calprotectin as noninvasive markers for inflammatory bowel disease in children. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008, 14(3), 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, N.; Onoue, S.; Takebe, T.; Takahashi, K.; Asai, Y.; Tamura, S.; Matsuura, T.; Yamade, M.; Iwaizumi, M.; Hamaya, Y.; Yamada, T.; Osawa, S.; Sugimoto, K. Fecal Calprotectin as a Biomarker of Crohn’s Disease in Patients With Short Disease Durations: A Prospective, Single-Center, Cross-Sectional Study. Gastroenterology Research and Practice 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Yu, L.; Fang, L.; Yang, W.; Yu, T.; Miao, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, K.; Chen, F.; Cong, Y.; Liu, Z. CD177+ neutrophils as functionally activated neutrophils negatively regulate IBD. Gut. 2018, 67(6), 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Shi, Q.; Wu, P.; Zhang, X.; Kambara, H.; Su, J.; Yu, H.; Park, S.Y.; Guo, R.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, S.; Xu, Y.; Silberstein, L.E.; Cheng, T.; Ma, F.; Li, C.; Luo, H.R. Single-cell transcriptome profiling reveals neutrophil heterogeneity in homeostasis and infection. Nat Immunol. 2020, 21(9), 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smillie, C.S.; Biton, M.; Ordovas-Montanes, J.; Sullivan, K.M.; Burgin, G.; Graham, D.B.; Herbst, R.H.; Rogel, N.; Slyper, M.; Waldman, J.; Sud, M.; Andrews, E.; Velonias, G.; Haber, A.L.; Jagadeesh, K.; Vickovic, S.; Yao, J.; Stevens, C.; Dionne, D.; Nguyen, L.T.; Villani, A.C.; Hofree, M.; Creasey, E.A.; Huang, H.; Rozenblatt-Rosen, O.; Garber, J.J.; Khalili, H.; Desch, A.N.; Daly, M.J.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Shalek, A.K.; Xavier, R.J.; Regev, A. Intra- and Inter-cellular Rewiring of the Human Colon during Ulcerative Colitis. Cell 2019, 178(3), 714–730.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkó, A.; Péterfi, Z.; Sum, A.; Leto, T.; Geiszt, M. Dual oxidases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005, 360(1464), 2301–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasberger, H.; Gao, J.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Kitamoto, S.; Zhang, M.; Kamada, N.; Eaton, K.A.; El-Zaatari, M.; Shreiner, A.B.; Merchant, J.L.; Owyang, C.; Kao, J.Y. Increased Expression of DUOX2 Is an Epithelial Response to Mucosal Dysbiosis Required for Immune Homeostasis in Mouse Intestine. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, E.C.; Santos, L.C.D.; Leonel, A.J.; de Oliveira, J.S.; Santos, E.A.; Navia-Pelaez, J.M.; da Silva, J.F.; Mendes, B.P.; Capettini, L.S.A.; Teixeira, L.G.; Lemos, V.S.; Alvarez-Leite, J.I. Oral butyrate reduces oxidative stress in atherosclerotic lesion sites by a mechanism involving NADPH oxidase down-regulation in endothelial cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2016, 4, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Tang, L.; Zhong, R.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H. Role of Mitophagy in Regulating Intestinal Oxidative Damage. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12(2), 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, P.S.; Kapur, N.; Barrett, T.A.; Theiss, A.L. Mitochondrial function and gastrointestinal diseases. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024, 21(8), 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, J.G. Targeting Neutrophils for Promoting the Resolution of Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 866747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, M.J.; Nakasone, E.S.; Shin, H.E.; Lee, H.; Park, J.C.; Lee, W.; Park, W.; Park, C.G.; Park, J.; Kim, S.N. Advanced Nanoparticle Therapeutics for Targeting Neutrophils in Inflammatory Diseases. Adv Healthc Mater. 2025, e2502092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigerblad, G.; Cao, Q.; Brooks, S.; Naz, F.; Gadkari, M.; Jiang, K.; Gupta, S.; O’Neil, L.; Dell’Orso, S.; Kaplan, M.J.; Franco, L.M. Single-Cell Analysis Reveals the Range of Transcriptional States of Circulating Human Neutrophils. J Immunol. 2022, 209(4), 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Trigo, A.; Corraliza, A.M.; Veny, M.; Dotti, I.; Melón-Ardanaz, E.; Rill, A.; Crowell, H.L.; Corbí, Á.; Gudiño, V.; Esteller, M.; Álvarez-Teubel, I.; Aguilar, D.; Masamunt, M.C.; Killingbeck, E.; Kim, Y.; Leon, M.; Visvanathan, S.; Marchese, D.; Caratù, G.; Martin-Cardona, A.; Esteve, M.; Ordás, I.; Panés, J.; Ricart, E.; Mereu, E.; Heyn, H.; Salas, A. Macrophage and neutrophil heterogeneity at single-cell spatial resolution in human inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Commun. 2023, 14(1), 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, M.; Pohin, M.; Jackson, M.A.; Korsunsky, I.; Bullers, S.J.; Rue-Albrecht, K.; Christoforidou, Z.; Sathananthan, D.; Thomas, T.; Ravindran, R.; Tandon, R.; Peres, R.S.; Sharpe, H.; Wei, K.; Watts, G.F.M.; Mann, E.H.; Geremia, A.; Attar, M. Oxford IBDCohort Investigators Roche Fibroblast Network Consortium McCuaig, S.; Thomas, L.; Collantes, E.; Uhlig, H.H.; Sansom, S.N.; Easton, A.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Travis, S.P.; Powrie, F.M. IL-1-driven stromal-neutrophil interactions define a subset of patients with inflammatory bowel disease that does not respond to therapies. Nat Med. 2021, 27(11), 1970–1981. [Google Scholar]

- Summers, C.; Rankin, S.M.; Condliffe, A.M.; Singh, N.; Peters, A.M.; Chilvers, E.R. Neutrophil kinetics in health and disease. Trends Immunol. 2010, 31(8), 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhan, M.; Wu, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, F.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. Aberrant expansion of CD177+ neutrophils promotes endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus via neutrophil extracellular traps. J Autoimmun. 2025, 152, 103399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Grieshaber-Bouyer, R.; Wang, J.; Schmider, A.B.; Wilson, Z.S.; Zeng, L.; Halyabar, O.; Godin, M.D.; Nguyen, H.N.; Levescot, A.; Cunin, P.; Lefort, C.T.; Soberman, R.J.; Nigrovic, P.A. CD177 modulates human neutrophil migration through activation-mediated integrin and chemoreceptor regulation. Blood. 2017, 130(19), 2092–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Vietinghoff, S.; Tunnemann, G.; Eulenberg, C.; Wellner, M.; Cristina Cardoso, M.; Luft, F.C.; Kettritz, R. NB1 mediates surface expression of the ANCA antigen proteinase 3 on human neutrophils. Blood. 2007, 109(10), 4487–4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacbarth, E.; Kajdacsy-Balla, A. Low density neutrophils in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and acute rheumatic fever. Arthritis Rheum. 1986, 29(11), 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Camarillo, C.; Alemán, O.R.; Rosales, C. Low-Density Neutrophils in Healthy Individuals Display a Mature Primed Phenotype. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 672520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neutrophils in cancer: Heterogeneous multifaceted | Request, P.D.F. Neutrophils in cancer: Heterogeneous multifaceted | Request, P.D.F. ResearchGate [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 14]. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353047575_Neutrophils_in_cancer_heterogeneous_and_multifaceted.

- Singh, A.K.; Ainciburu, M.; Wynne, K.; Bhat, S.A.; Blanco, A.; Tzani, I.; Akiba, Y.; Lalor, S.J.; Kaunitz, J.; Bourke, B.; Kelly, V.P.; Doherty, G.A.; Zerbe, C.S.; Clarke, C.; Hussey, S.; Knaus, U.G. De novo DUOX2 expression in neutrophil subsets shapes the pathogenesis of intestinal disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025, 122(19), e2421747122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilidis, E.; Divolis, G.; Natsi, A.M.; Kafalis, N.; Kogias, D.; Antoniadou, C.; Synolaki, E.; Pavlos, E.; Koutsi, M.A.; Didaskalou, S.; Papadimitriou, E.; Tsironidou, V.; Gavriil, A.; Papadopoulos, V.; Agelopoulos, M.; Tsilingiris, D.; Koffa, M.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Kouklakis, G.; Ritis, K.; Skendros, P. Neutrophil-fibroblast crosstalk drives immunofibrosis in Crohn’s disease through IFNα pathway. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1447608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Lin, J.; Zhang, C.; Gao, H.; Lu, H.; Gao, X.; Zhu, R.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, Z. Microbiota metabolite butyrate constrains neutrophil functions and ameliorates mucosal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Microbes. 2021, 13(1), 1968257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippo, K.; Rankin, S.M. CXCR4, the master regulator of neutrophil trafficking in homeostasis and disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018, 48 (Suppl 2), e12949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Lv, J.; Leng, Y. The emerging role of neutrophilic extracellular traps in intestinal disease. Gut Pathog. 2022, 14(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, A.W. How neutrophils kill microbes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005, 23, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviello, G.; Knaus, U.G. NADPH oxidases and ROS signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11(4), 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, V.; Reichard, U.; Goosmann, C.; Fauler, B.; Uhlemann, Y.; Weiss, D.S.; Weinrauch, Y.; Zychlinsky, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004, 303(5663), 1532–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.J.; Radic, M. Neutrophil extracellular traps: Double-edged swords of innate immunity. J Immunol. 2012, 189(6), 2689–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, C.T.N. Neutrophil serine proteases: Specific regulators of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006, 6(7), 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabouridis, P.S.; Lasrado, R.; McCallum, S.; Chng, S.H.; Snippert, H.J.; Clevers, H.; Pettersson, S.; Pachnis, V. The gut microbiota keeps enteric glial cells on the move; prospective roles of the gut epithelium and immune system. Gut Microbes. 2015, 6(6), 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik, C.D.; Kim, N.D.; Luster, A.D. Neutrophils cascading their way to inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2011, 32(10), 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Zhu, J.; Mei, Q. Low-density Granulocytes as a Novel Biomarkers of Disease Activity in IBD. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2023, 29(8), e31–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaveris, C.; Wilk, A.; Riley, N.; Stark, J.; Yang, S.; Rogers, A.; Ranganath, T.; Nadeau, K.; Blish, C.; Bertozzi, C. Synthetic Siglec-9 Agonists Inhibit Neutrophil Activation Associated with COVID-19 [Internet]. Chemistry; 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 14]. Available online: https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/60c75305469df463f7f44ca1.

- Sonnenberg, G.F.; Fouser, L.A.; Artis, D. Functional biology of the IL-22-IL-22R pathway in regulating immunity and inflammation at barrier surfaces. Adv Immunol. 2010, 107, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Schroder, K.; Hertzog, P.J.; Ravasi, T.; Hume, D.A. Interferon-gamma: An overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2004, 75(2), 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, E.M.; Oh, C.T.; Bae, Y.S.; Lee, W.J. A direct role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science 2005, 310(5749), 847–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasberger, H.; Magis, A.T.; Sheng, E.; Conomos, M.P.; Zhang, M.; Garzotto, L.S.; Hou, G.; Bishu, S.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; El-Zaatari, M.; Kitamoto, S.; Kamada, N.; Stidham, R.W.; Akiba, Y.; Kaunitz, J.; Haberman, Y.; Kugathasan, S.; Denson, L.A.; Omenn, G.S.; Kao, J.Y. DUOX2 variants associate with preclinical disturbances in microbiota-immune homeostasis and increased inflammatory bowel disease risk. J Clin Invest. 2021, e141676, 141676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.D.; Smythies, L.E.; Shen, R.; Greenwell-Wild, T.; Gliozzi, M.; Wahl, S.M. Intestinal macrophages and response to microbial encroachment. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chalmers, L.; Fu, X.; Zhao, M. A Molecular Link Between Interleukin 22 and Intestinal Mucosal Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2012, 1(6), 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas, B.; Natividad, J.M.; Sokol, H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and intestinal immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11(4), 1024–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, C.L.; Xing, L.; McPhee, J.B.; Law, H.T.; Coombes, B.K. Acute Infectious Gastroenteritis Potentiates a Crohn’s Disease Pathobiont to Fuel Ongoing Inflammation in the Post-Infectious Period. PLOS Pathogens. 2016, 12(10), e1005907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragland, S.A.; Criss, A.K. From bacterial killing to immune modulation: Recent insights into the functions of lysozyme. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13(9), e1006512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bots, S.; Nylund, K.; Löwenberg, M.; Gecse, K.; D’Haens, G. Intestinal Ultrasound to Assess Disease Activity in Ulcerative Colitis: Development of a novel UC-Ultrasound Index. J Crohns Colitis. 2021, 15(8), 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, J.; Ding, M.; Zhou, X. Recent advances in S-palmitoylation and its emerging roles in human diseases. J Hematol Oncol. 2025, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canani, R.B.; Costanzo, M.D.; Leone, L.; Pedata, M.; Meli, R.; Calignano, A. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011, 17(12), 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, J.R. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J Nutr. 2003, 133(7 Suppl), 2485S–2493S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarade, A.; Garcia, Z.; Marie, S.; Demera, A.; Prinz, I.; Bousso, P.; Di Santo, J.P.; Serafini, N. Inflammation triggers ILC3 patrolling of the intestinal barrier. Nat Immunol. 2022, 23(9), 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowski, J.; Dabrowska, M.; Lazowska, I.; Paziewska, A.; Balabas, A.; Kluska, A.; Kulecka, M.; Karczmarski, J.; Ambrozkiewicz, F.; Piatkowska, M.; Goryca, K.; Zeber-Lubecka, N.; Kierkus, J.; Socha, P.; Lodyga, M.; Klopocka, M.; Iwanczak, B.; Bak-Drabik, K.; Walkowiak, J.; Radwan, P.; Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U.; Korczowski, B.; Starzynska, T.; Mikula, M. Redefining the Practical Utility of Blood Transcriptome Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2019, 13(5), 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, A.N.; West, N.R.; Stubbington, M.J.T.; Wendt, E.; Suijker, K.I.M.; Datsi, A.; This, S.; Danne, C.; Campion, S.; Duncan, S.H.; Owens, B.M.J.; Uhlig, H.H.; McMichael, A.; Oxford IBDCohort Investigators Bergthaler, A.; Teichmann, S.A.; Keshav, S.; Powrie, F. Circulating and Tissue-Resident CD4+ T Cells With Reactivity to Intestinal Microbiota Are Abundant in Healthy Individuals and Function Is Altered During Inflammation. Gastroenterology 2017, 153(5), 1320–1337.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Xiao, J.; Gao, M.; Zhou, H.F.; Fan, H.; Sun, F.; Cui, D.D. IRF/Type I IFN signaling serves as a valuable therapeutic target in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. International Immunopharmacology. 2021, 92, 107350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, A.M.; Szakmary, A.; Schiestl, R.H. Mechanisms of intestinal inflammation and development of associated cancers: Lessons learned from mouse models. Mutat Res. 2010, 705(1), 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlato, M.; Charbit-Henrion, F.; Hayes, P.; Tiberti, A.; Aloi, M.; Cucchiara, S.; Bègue, B.; Bras, M.; Pouliet, A.; Rakotobe, S.; Ruemmele, F.; Knaus, U.G.; Cerf-Bensussan, N. First Identification of Biallelic Inherited DUOX2 Inactivating Mutations as a Cause of Very Early Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2017, 153(2), 609–611.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenhöfer, S.; Radermacher, K.A.; Kleikers, P.W.M.; Wingler, K.; Schmidt, H.H.H.W. Evolution of NADPH Oxidase Inhibitors: Selectivity and Mechanisms for Target Engagement. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015, 23(5), 406–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkó, A.; Péterfi, Z.; Sum, A.; Leto, T.; Geiszt, M. Dual oxidases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005, 360(1464), 2301–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiszt, M.; Witta, J.; Baffi, J.; Lekstrom, K.; Leto, T.L. Dual oxidases represent novel hydrogen peroxide sources supporting mucosal surface host defense. FASEB J. 2003, 17(11), 1502–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staicu, I. Neutrophil subsets. Nat Immunol. 2024, 25(4), 583–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DUOX2 activation drives bacterial translocation and subclinical inflammation in IBD-associated dysbiosis | Gut [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 13]. Available online: https://gut.bmj.com/content/74/10/1589.

- Ortega-Zapero, M.; Gomez-Bris, R.; Pascual-Laguna, I.; Saez, A.; Gonzalez-Granado, J.M. Neutrophils and NETs in Pathophysiology and Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26(15), 7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaiatz Bittencourt, V.; Jones, F.; Doherty, G.; Ryan, E.J. Targeting Immune Cell Metabolism in the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021, 27(10), 1684–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taman, H.; Fenton, C.G.; Hensel, I.V.; Anderssen, E.; Florholmen, J.; Paulssen, R.H. Transcriptomic Landscape of Treatment-Naïve Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2018, 12(3), 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak JK, Adams AT, Kalla R, Lindstrøm JC, Vatn S, Bergemalm D, Keita ÅV, Gomollón F, Jahnsen J, Vatn MH, Ricanek P, Ostrowski J, Walkowiak J, Halfvarson J, Satsangi J, IBD Character Consortium. Characterisation of the Circulating Transcriptomic Landscape in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Provides Evidence for Dysregulation of Multiple Transcription Factors Including NFE2, SPI1, CEBPB, and IRF2. J Crohns Colitis. 2022, 16(8), 1255–1268.

- Grasberger, H.; Magis, A.T.; Sheng, E.; Conomos, M.P.; Zhang, M.; Garzotto, L.S.; Hou, G.; Bishu, S.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; El-Zaatari, M.; Kitamoto, S.; Kamada, N.; Stidham, R.W.; Akiba, Y.; Kaunitz, J.; Haberman, Y.; Kugathasan, S.; Denson, L.A.; Omenn, G.S.; Kao, J.Y. DUOX2 variants associate with preclinical disturbances in microbiota-immune homeostasis and increased inflammatory bowel disease risk. J Clin Invest. 2021, e141676, 141676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, S.; Sakuraba, H. Uptake and Advanced Therapy of Butyrate in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Immuno. 2022, 2(4), 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Han, S.; Kwon, J.; Ju, S.; Choi, T.G.; Kang, I.; Kim, S.S. Roles of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients. 2023, 15(20), 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conder, E.; Shay, H.C.; Vekaria, H.; Erinkitola, I.; Bhogoju, S.; Goretsky, T.; Sullivan, P.; Barrett, T.; Kapur, N. BUTYRATE-INDUCED MITOCHONDRIAL FUNCTION IMPROVES BARRIER FUNCTION IN INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE (IBD). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023, 29 (Suppl. 1), S71–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J. Are short-chain fatty acid enemas effective for left-sided ulcerative colitis? Gastroenterology. 1998, 114(1), 218–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Su, C.; Sands, B.E.; D’Haens, G.R.; Vermeire, S.; Schreiber, S.; Danese, S.; Feagan, B.G.; Reinisch, W.; Niezychowski, W.; Friedman, G.; Lawendy, N.; Yu, D.; Woodworth, D.; Mukherjee, A.; Zhang, H.; Healey, P.; Panés, J. OCTAVE Induction 1, OCTAVE Induction 2, and OCTAVE Sustain Investigators. Tofacitinib as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376(18), 1723–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, R.; Kambara, H.; Ma, F.; Luo, H.R. The role of CXCR2 in acute inflammatory responses and its antagonists as anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Curr Opin Hematol. 2019, 26(1), 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitaru, S.; Budke, A.; Bertini, R.; Sperandio, M. Therapeutic inhibition of CXCR1/2: Where do we stand? Intern Emerg Med. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wu, Q.; Nie, Y.; Cheng, N.; Wang, R.; Wang, G.; Zhang, D.; He, H.; Ye, R.D.; Qian, F. A Role for MK2 in Enhancing Neutrophil-Derived ROS Production and Aggravating Liver Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Jiang, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Duan, S.; Sun, L.; Zhao, W.; Qian, F. MK2 Is Required for Neutrophil-Derived ROS Production and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020, 7, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.S.Y.; Coller, J.K.; Hughes, P.A.; Prestidge, C.A.; Bowen, J.M. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) antagonists as potential therapeutics for intestinal inflammation. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2021, 40(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzmich, N.N.; Sivak, K.V.; Chubarev, V.N.; Porozov, Y.B.; Savateeva-Lyubimova, T.N.; Peri, F. TLR4 Signaling Pathway Modulators as Potential Therapeutics in Inflammation and Sepsis. Vaccines (Basel). 2017, 5(4), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaure, C.; Liu, Y. A comparative review of toll-like receptor 4 expression and functionality in different animal species. Front Immunol. 2014, 5, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramsothy, S.; Kamm, M.A.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Walsh, A.J.; van den Bogaerde, J.; Samuel, D.; Leong, R.W.L.; Connor, S.; Ng, W.; Paramsothy, R.; Xuan, W.; Lin, E.; Mitchell, H.M.; Borody, T.J. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017, 389(10075), 1218–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.T.; Green, E.R.; Mecsas, J. Neutrophils to the ROScue: Mechanisms of NADPH Oxidase Activation and Bacterial Resistance. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017, 7, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillón-Betancur, J.C.; López-Agudelo, V.A.; Sommer, N.; Cleeves, S.; Bernardes, J.P.; Weber-Stiehl, S.; Rosenstiel, P.; Sommer, F. Epithelial Dual Oxidase 2 Shapes the Mucosal Microbiome and Contributes to Inflammatory Susceptibility. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12(10), 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, F.; Bäckhed, F. The gut microbiota engages different signaling pathways to induce Duox2 expression in the ileum and colon epithelium. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8(2), 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bento, A.F.; Leite, D.F.P.; Claudino, R.F.; Hara, D.B.; Leal, P.C.; Calixto, J.B. The selective nonpeptide CXCR2 antagonist SB225002 ameliorates acute experimental colitis in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2008, 84(4), 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; He, H.; Fan, L.; Ma, C.; Xu, Z.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, G. Blockade of CXCR2 suppresses proinflammatory activities of neutrophils in ulcerative colitis. Am J Transl Res. 2020, 12(9), 5237–5251. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Kuang, W.; Wang, D.; Yuan, K.; Yang, P. Expanding role of CXCR2 and therapeutic potential of CXCR2 antagonists in inflammatory diseases and cancers. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2023, 250, 115175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Xiao, J.; Gao, M.; Zhou, H.F.; Fan, H.; Sun, F.; Cui, D.D. IRF/Type I IFN signaling serves as a valuable therapeutic target in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. International Immunopharmacology. 2021, 92, 107350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, E.V.; Panés, J.; Lacerda, A.P.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; D’Haens, G.; Panaccione, R.; Reinisch, W.; Louis, E.; Chen, M.; Nakase, H.; Begun, J.; Boland, B.S.; Phillips, C.; Mohamed, M.E.F.; Liu, J.; Geng, Z.; Feng, T.; Dubcenco, E.; Colombel, J.F. Upadacitinib Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388(21), 1966–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AE.; MF.; FP IL-1-mediated remodelling of the stromal-neutrophil landscape is associated with non-response to therapy in a subset of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cell [Internet]. 2020 Jul 3 [cited 2025 Sep 13]. Available online: https://www.oncology.ox.ac.uk/publications/1116098.

- (PDF) IL-1-driven stromal-neutrophil interaction in deep ulcers defines a pathotype of therapy non-responsive inflammatory bowel disease [Internet]. ResearchGate. [cited 2025 Sep 13]. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349100219_IL-1-driven_stromal-neutrophil_interaction_in_deep_ulcers_defines_a_pathotype_of_therapy_non-responsive_inflammatory_bowel_disease.

- Ahmad, G.; Chami, B.; Liu, Y.; Schroder, A.L.; San Gabriel, P.T.; Gao, A.; Fong, G.; Wang, X.; Witting, P.K. The Synthetic Myeloperoxidase Inhibitor AZD3241 Ameliorates Dextran Sodium Sulfate Stimulated Experimental Colitis. Front Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 556020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Hunter, J.; Lee, A.; Ahmad, G.; Witting, P.K.; Ortiz-Cerda, T. The PAD4 inhibitor GSK484 diminishes neutrophil extracellular trap in the colon mucosa but fails to improve inflammatory biomarkers in experimental colitis. Biosci Rep. 2025, 45(6), 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehandru, S.; Colombel, J.F.; Juarez, J.; Bugni, J.; Lindsay, J.O. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of anti-trafficking therapies and their clinical relevance in inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunology. 2023, 16(6), 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, D.; Chapman, T.; Yang, L.L.; Wyant, T.; Egan, R.; Fedyk, E.R. The binding specificity and selective antagonism of vedolizumab, an anti-alpha4beta7 integrin therapeutic antibody in development for inflammatory bowel diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009, 330(3), 864–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosenboom, B.; Lochem EGvan Meijer, J.; Smids, C.; Nierkens, S.; Brand, E.C.; Erp LWvan Kemperman, L.G.J.M.; Groenen, M.J.M.; Horje, C.S.H.T.; Wahab, P.J. Development of Mucosal PNAd+ and MAdCAM-1+ Venules during Disease Course in Ulcerative Colitis. Cells. 2020, 9(4), 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchin, S.; Vitulo, N.; Calgaro, M.; Buda, A.; Romualdi, C.; Pohl, D.; Perini, B.; Lorenzon, G.; Marinelli, C.; D’Incà, R.; Sturniolo, G.C.; Savarino, E.V. Microbiota changes induced by microencapsulated sodium butyrate in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020, 32(10), e13914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, K.; El Abbar, F.; Dobranowski, P.; Manoogian, J.; Butcher, J.; Figeys, D.; Mack, D.; Stintzi, A. Butyrate’s role in human health and the current progress towards its clinical application to treat gastrointestinal disease. Clin Nutr. 2023, 42(2), 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.S. PAD4-dependent neutrophil extracellular traps dagame intestinal barrier integrity through histone protein components. J Immunol. 2023, 210 Suppl. 1, 61.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, F.; Shen, Y.; You, Q.; Lu, S.; Wu, J. The role of protein arginine deiminase 4-dependent neutrophil extracellular traps formation in ulcerative colitis. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1144976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Mao, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y. The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps in ulcerative colitis. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1425251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, M.; Horst, S.; Caldera, F. Applying Biomarkers in Treat-to-target Approach for IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2025, 27(1), 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lee, S.A.; Riordan, S.M.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L. Global Studies of Using Fecal Biomarkers in Predicting Relapse in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020, 7, 580803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, P.; Zhai, X.; Wang, Z.; Miao, X.; Yang, Y.; Wu, J. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce barrier dysfunction in DSS-induced ulcerative colitis via the cGAS-STING pathway. International Immunopharmacology. 2024, 143, 113358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmochowska, N.; Tieu, W.; Keller, M.D.; Wardill, H.R.; Mavrangelos, C.; Campaniello, M.A.; Takhar, P.; Hughes, P.A. Immuno-PET of Innate Immune Markers CD11b and IL-1β Detects Inflammation in Murine Colitis. J Nucl Med. 2019, 60(6), 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettenworth, D.; Reuter, S.; Hermann, S.; Weckesser, M.; Kerstiens, L.; Stratis, A.; Nowacki, T.M.; Ross, M.; Lenze, F.; Edemir, B.; Maaser, C.; Pap, T.; Koschmieder, S.; Heidemann, J.; Schäfers, M.; Lügering, A. Translational 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging to monitor lesion activity in intestinal inflammation. J Nucl Med. 2013, 54(5), 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezazadeh, F.; Kilcline, A.P.; Viola, N.T. Imaging Agents for PET of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. J Nucl Med. 2023, 64(12), 1858–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, J.R.; Wu, Y.; Ta, H.T. VCAM-1 as a common biomarker in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer: Unveiling the dual anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer capacities of anti-VCAM-1 therapies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2025, 44(2), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, K.; Burns, C. Adhesion molecules in lymphocyte trafficking and colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001, 121(4), 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.Y.; Miralda, I.; Armstrong, C.L.; Uriarte, S.M.; Bagaitkar, J. The roles of NADPH oxidase in modulating neutrophil effector responses. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2019, 34(2), 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C.; Kettle, A.J.; Hampton, M.B. Reactive Oxygen Species and Neutrophil Function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016, 85, 765–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luecken, M.D.; Theis, F.J. Current best practices in single-cell RNA-seq analysis: A tutorial. Mol Syst Biol. 2019, 15(6), e8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, M.; Pohin, M.; Powrie, F. Cytokine Networks in the Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Immunity. 2019, 50(4), 992–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.L.; Sundrud, M.S. Cytokine networks and T cell subsets in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016, 22(5), 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennillo, E.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, G.; Rusu, I.; Patel, R.K.; Dorman, L.C.; Flynn, E.; Li, S.; Bain, J.L.; Andersen, C.; Rao, A.; Tamaki, S.; Tsui, J.; Shen, A.; Lotstein, M.L.; Rahim, M.; Naser, M.; Bernard-Vazquez, F.; Eckalbar, W.; Cho, S.J.; Beck, K.; El-Nachef, N.; Lewin, S.; Selvig, D.R.; Terdiman, J.P.; Mahadevan, U.; Oh, D.Y.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Pisco, A.; Combes, A.J.; Kattah, M.G. Single-cell and spatial multi-omics highlight effects of anti-integrin therapy across cellular compartments in ulcerative colitis. Nat Commun. 2024, 15(1), 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lismont, C.; Revenco, I.; Li, H.; Costa, C.F.; Lenaerts, L.; Hussein, M.A.F.; De Bie, J.; Knoops, B.; Van Veldhoven, P.P.; Derua, R.; Fransen, M. Peroxisome-Derived Hydrogen Peroxide Modulates the Sulfenylation Profiles of Key Redox Signaling Proteins in Flp-In T-REx 293 Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022, 10, 888873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, N.J.; Zhang, T.; Gaffrey, M.J.; Zhao, R.; Fillmore, T.L.; Moore, R.J.; Rodney, G.G.; Qian, W.J. A deep redox proteome profiling workflow and its application to skeletal muscle of a Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy model. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2022, 193, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global redox proteome and phosphoproteome analysis reveals redox switch in Akt | Nature Communications [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 4]. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-13114-4.

- Li, X.; Gluth, A.; Zhang, T.; Qian, W.J. Thiol redox proteomics: Characterization of thiol-based post-translational modifications. Proteomics 2023, 23(13–14), e2200194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gaffrey, M.J.; Li, X.; Qian, W.J. Characterization of cellular oxidative stress response by stoichiometric redox proteomics. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021, 320(2), C182–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global redox proteome and phosphoproteome analysis reveals redox switch in Akt. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 5486. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Z.; Burchfield, J.G.; Yang, P.; Humphrey, S.J.; Yang, G.; Francis, D.; Yasmin, S.; Shin, S.Y.; Norris, D.M.; Kearney, A.L.; Astore, M.A.; Scavuzzo, J.; Fisher-Wellman, K.H.; Wang, Q.P.; Parker, B.L.; Neely, G.G.; Vafaee, F.; Chiu, J.; Yeo, R.; Hogg, P.J.; Fazakerley, D.J.; Nguyen, L.K.; Kuyucak, S.; James, D.E. Global redox proteome and phosphoproteome analysis reveals redox switch in Akt. Nat Commun. 2019, 10(1), 5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz Castro, P.A.; Yepiskoposyan, H.; Gubian, S.; Calvino-Martin, F.; Kogel, U.; Renggli, K.; Peitsch, M.C.; Hoeng, J.; Talikka, M. Systems biology approach highlights mechanistic differences between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Sci Rep. 2021, 11(1), 11519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasam, V.; Davis, T.; Ghali, M.; Tejcek, D.; RO’Neil, T.; Verley, E.; Griffiths, M.; Campos, M.; Bonney, I.; Bulmer, A.C.; Ramaswamy, Y.; Mitrev, N.; Corte, C.; Witting, P.K.; Chami, B. Myeloperoxidase Luminol Reaction - A Novel Faecal Assay for Predicting Colonoscopy Findings in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Clinical Study. Adv Healthc Mater. 2025, e01825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D’Amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; Schölmerich, J.; Bemelman, W.; Danese, S.; Mary, J.Y.; Rubin, D.; Colombel, J.F.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Dotan, I.; Abreu, M.T.; Dignass, A.; International Organization for the Study of, I.B.D. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021, 160(5), 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheppach, W.; Sommer, H.; Kirchner, T.; Paganelli, G.M.; Bartram, P.; Christl, S.; Richter, F.; Dusel, G.; Kasper, H. Effect of butyrate enemas on the colonic mucosa in distal ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992, 103(1), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breuer, R.I.; Soergel, K.H.; Lashner, B.A.; Christ, M.L.; Hanauer, S.B.; Vanagunas, A.; Harig, J.M.; Keshavarzian, A.; Robinson, M.; Sellin, J.H.; Weinberg, D.; Vidican, D.E.; Flemal, K.L.; Rademaker, A.W. Short chain fatty acid rectal irrigation for left-sided ulcerative colitis: A randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 1997, 40(4), 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luceri, C.; Femia, A.P.; Fazi, M.; Di Martino, C.; Zolfanelli, F.; Dolara, P.; Tonelli, F. Effect of butyrate enemas on gene expression profiles and endoscopic/histopathological scores of diverted colorectal mucosa: A randomized trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2016, 48(1), 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulkina, M.; Rohmer, C.; McAninch, S.; Panganiban, R.P.; Villéger, R.; Portolese, A.; Ciocirlan, J.; Yang, W.; Cohen, C.; Koltun, W.; Valentine, J.F.; Cong, Y.; Yochum, G.; Beswick, E.J.; Pinchuk, I.V. Increased Activity of MAPKAPK2 within Mesenchymal Cells as a Target for Inflammation-Associated Fibrosis in Crohn’s Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2024, 18(7), 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liang, X.Y.; Chang, X.; Nie, Y.Y.; Guo, C.; Jiang, J.H.; Chang, M. MMI-0100 Ameliorates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in Mice through Targeting MK2 Pathway. Molecules. 2019, 24(15), 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeks, E.D. Anifrolumab: First Approval. Drugs. 2021, 81(15), 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Neutrophil Subset | Key Markers / Traits | Context / Location | Functional Roles | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting circulating neutrophils | CD16^+, CD62L^+, CXCR2^+ | Blood (homeostasis) | Baseline antimicrobial defense; short-lived; enter tissues upon chemokine signaling. | [24] |

| CD177^+ neutrophils | CD177^hi, CD66b^+, FcγRIIIb^+ | Inflamed intestinal mucosa in IBD | Enhanced chemotaxis and bactericidal activity; support barrier defense; also release pro-inflammatory mediators; correlate with IBD severity. | [25,26] |

| CD177^- neutrophils | CD177^-; otherwise phenotypically similar to CD177^+ | Blood, IBD mucosa | Lower recruitment compared to CD177^+; may have less effector potency; role still under investigation. | [27] |

| Low-density neutrophils (LDNs) | Low buoyant density; often immature; heterogeneous; markers vary | Autoimmunity, cancer, severe inflammation, IBD flares | Immunosuppressive (MDSC-like) or proinflammatory; can release ROS and NETs; expansion reported in active IBD. | [28,29] |

| Inflammation-primed neutrophils | Upregulated CXCR1/2, CD11b; downregulated CXCR4; increased activation markers | Inflamed tissue niches (gut mucosa in IBD) | Heightened effector functions (ROS, degranulation, NETs); strong recruitment cascades; IFN-priming can drive fibrotic plasticity in Crohn’s. | [30] |

| DUOX2^+ neutrophils | De novo DUOX2 expression (with NOX2); upregulated chemokines (CXCL1/2), cytokines (IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6) | Inflamed intestine (murine colitis, human IBD) | Expanded oxidative capacity; extracellular H₂O₂ production; amplify cytokine loops; sustain chronic mucosal inflammation and fibrosis. | [31] |

| Stimulus / Factor | Target Cell Type | Effect on DUOX2 / H₂O₂ | Pathophysiological Consequence | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN-γ (Th1 cytokine) | Intestinal epithelium | Strong upregulation of DUOX2 and H₂O₂ | Drives epithelial oxidative burst; promotes chronic inflammation in IBD. | [47,48] |

| IL-22 (Type 17 cytokine) | Intestinal epithelium | Increases DUOX2 expression | Enhances epithelial host defense; may aid barrier repair and antimicrobial protection. | [49,50] |

| TLR4 agonists (LPS) | Intestinal epithelium | Upregulates DUOX2 and H₂O₂ | Couples bacterial sensing to ROS output; implicated in colitis-associated tumorigenesis. | [37,51] |

| Adherent-invasive E. coli | Intestinal epithelium | Potently induces DUOX2 | Amplifies H₂O₂ release during dysbiosis; promotes mucosal inflammation. | [52,53] |

| Dysbiotic microbiota | Intestinal epithelium | Broad activation of DUOX2 | Marker of disrupted homeostasis; correlates with early preclinical IBD changes. | [54,55] |

| Short-chain fatty acids (butyrate) | Intestinal epithelium | Downregulates DUOX2 | Restores barrier integrity; dampens inflammation by lowering epithelial H₂O₂ output. | [56] |

| HDAC inhibitors | Intestinal epithelium | Mimic butyrate effect, suppress DUOX2 | Potential therapeutic avenue to control DUOX2-mediated oxidative stress. | [57] |

| Inflammatory milieu (IL-8, TNF, IFNα) | Neutrophils (new finding) | Induces de novo DUOX2 expression | Neutrophils gain extra oxidative capacity; amplify cytokine circuits and tissue inflammation in IBD. | [57,58] |

| Strategy / Target | Mechanism of Action | Expected Effect on IBD | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil DUOX2 inhibition | Genetic silencing (e.g., conditional knockout) or small-molecule inhibition of DUOX2 | Reduces neutrophil H₂O₂ and cytokine output; suppresses mucosal inflammation; improves colitis in models. ⚠ Risk: impaired pathogen defense. | [31,73] |

| Butyrate / SCFA supplementation | Microbial metabolite; inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs) | Downregulates epithelial and neutrophil DUOX2; reduces cytokine release and NETosis; enhances barrier integrity. | [74,75,76] |

| JAK inhibitors (e.g., baricitinib, tofacitinib) | Block IFN-α/γ and other cytokine signaling via JAK–STAT pathway | Prevent IFNα-driven neutrophil–fibroblast immunofibrosis; reduce IL-8–mediated recruitment; established anti-inflammatory effect in IBD. | [77,78] |

| CXCR1/2 antagonists (e.g., reparixin) | Block neutrophil chemokine receptors for IL-8/CXCL1/2 | Reduces neutrophil migration into gut mucosa; may lower neutrophil burden and tissue injury. | [79,80] |

| MK2 (p38 MAPK) inhibitors | Inhibit MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2), required for NADPH oxidase assembly/ROS | Decreases neutrophil-derived ROS and cytokine output; protects against DSS colitis in preclinical studies. | [81,82] |

| TLR4 antagonists (e.g., eritoran) | Block LPS binding to TLR4 on epithelial cells | Prevent LPS-induced DUOX2 overactivation; reduces epithelial oxidative stress and inflammation. | [83,84,85] |

| Probiotics / Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) | Restore commensals and SCFA-producers (e.g., Clostridium clusters) | Reduce dysbiosis-driven DUOX2 activation; increase butyrate production; rebalance immune–microbiota crosstalk. | [86] |

| Antioxidants (e.g., N-acetylcysteine, vitamins C/E) | Scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) | Neutralize excessive H₂O₂ from DUOX2/NOX; may reduce epithelial oxidative injury, but efficacy is inconsistent. | [15,73,87] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).