Submitted:

30 October 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of Blood Samples Using IR Microspectroscopy

2.2. Spectral Preprocessing and Multivariate Data Analysis

2.3. Construction of a Spectral Database for Thalassemia Classification

3. Results

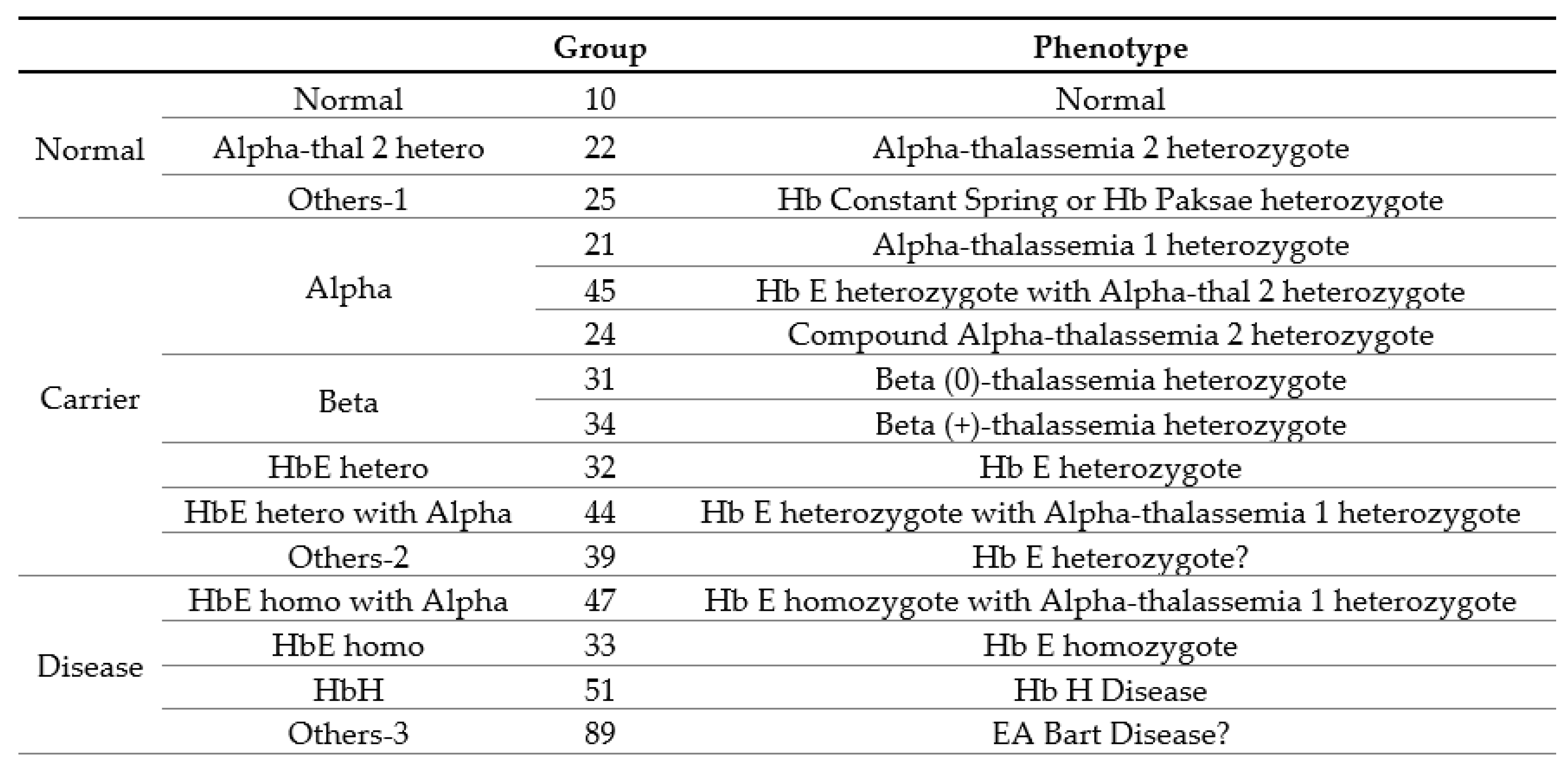

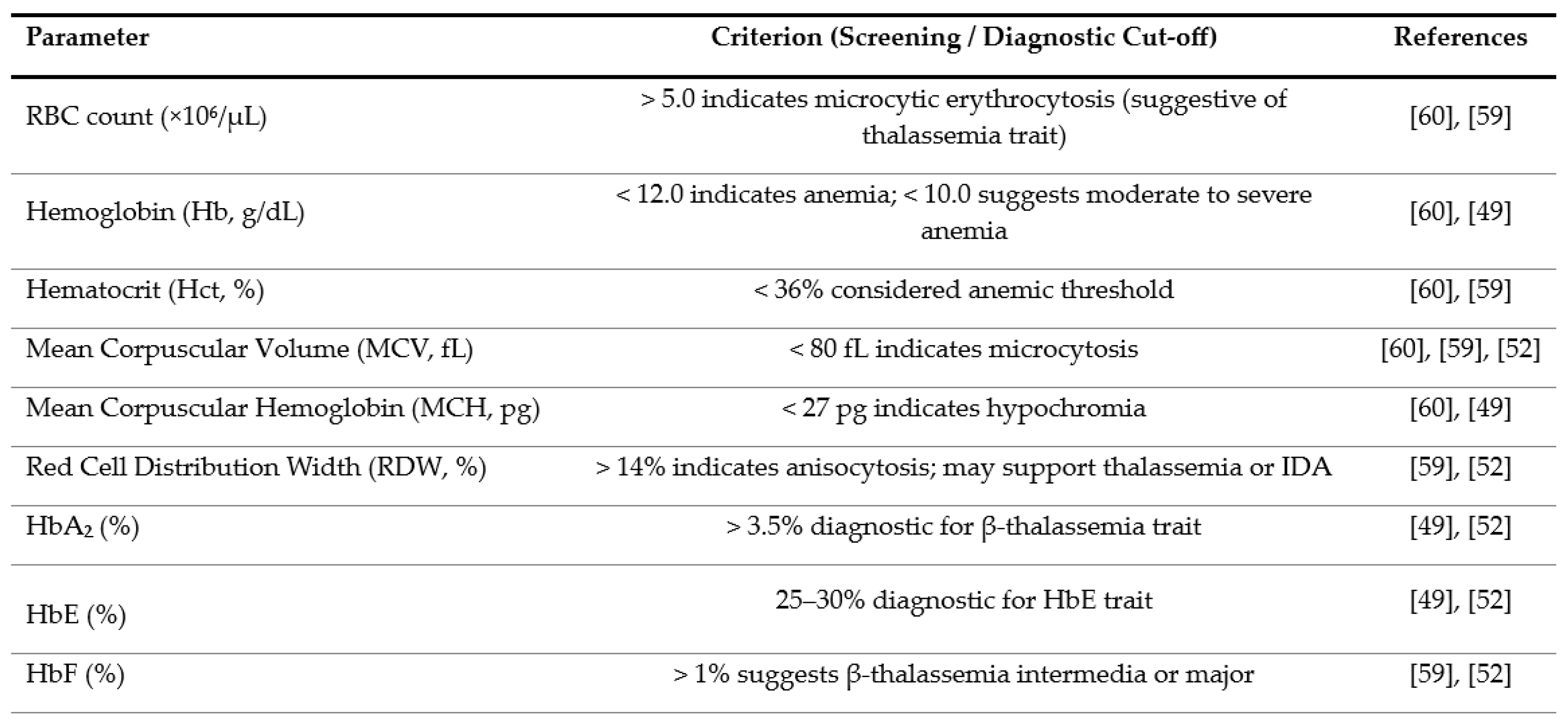

3.1. Clinical and Hematological Data

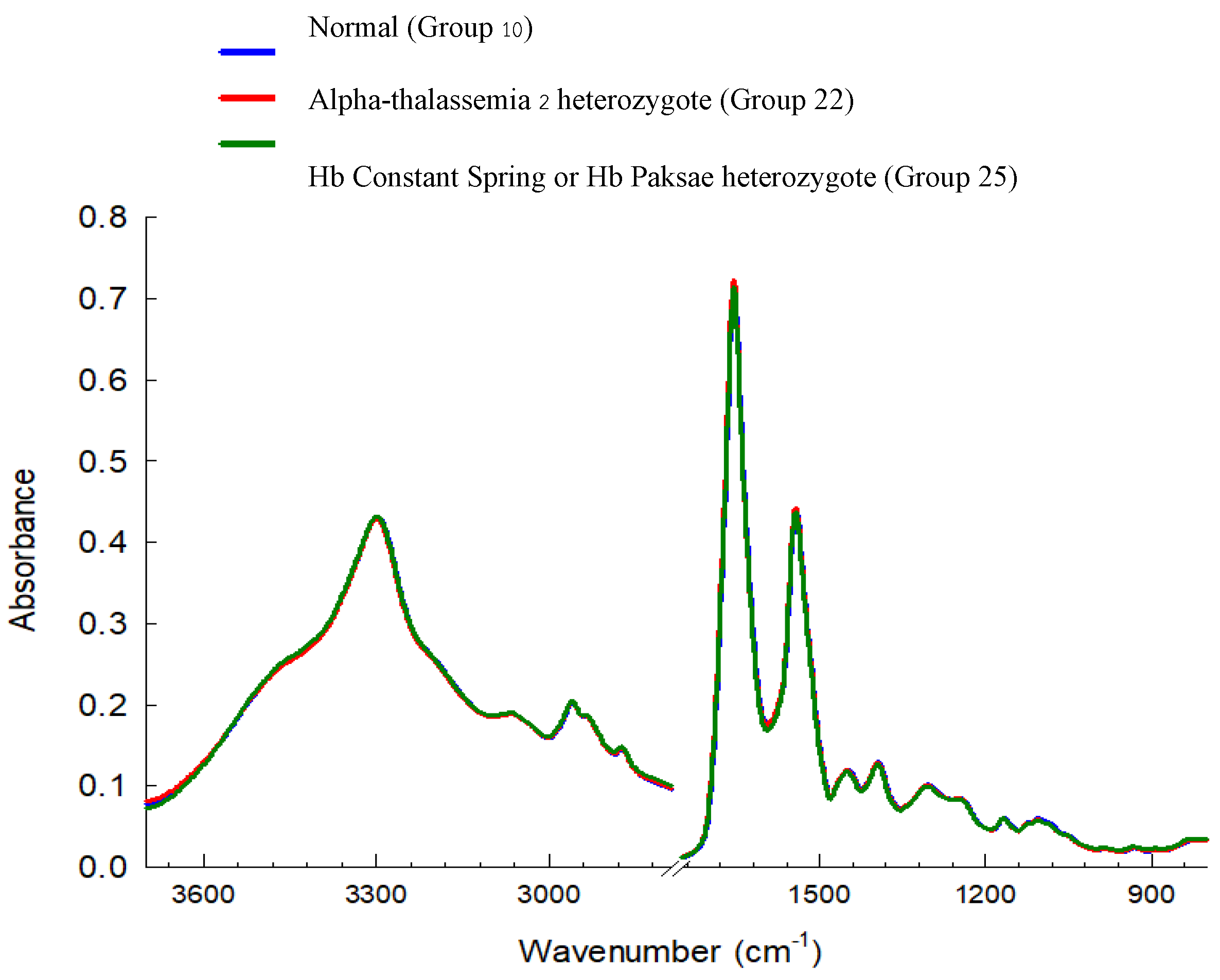

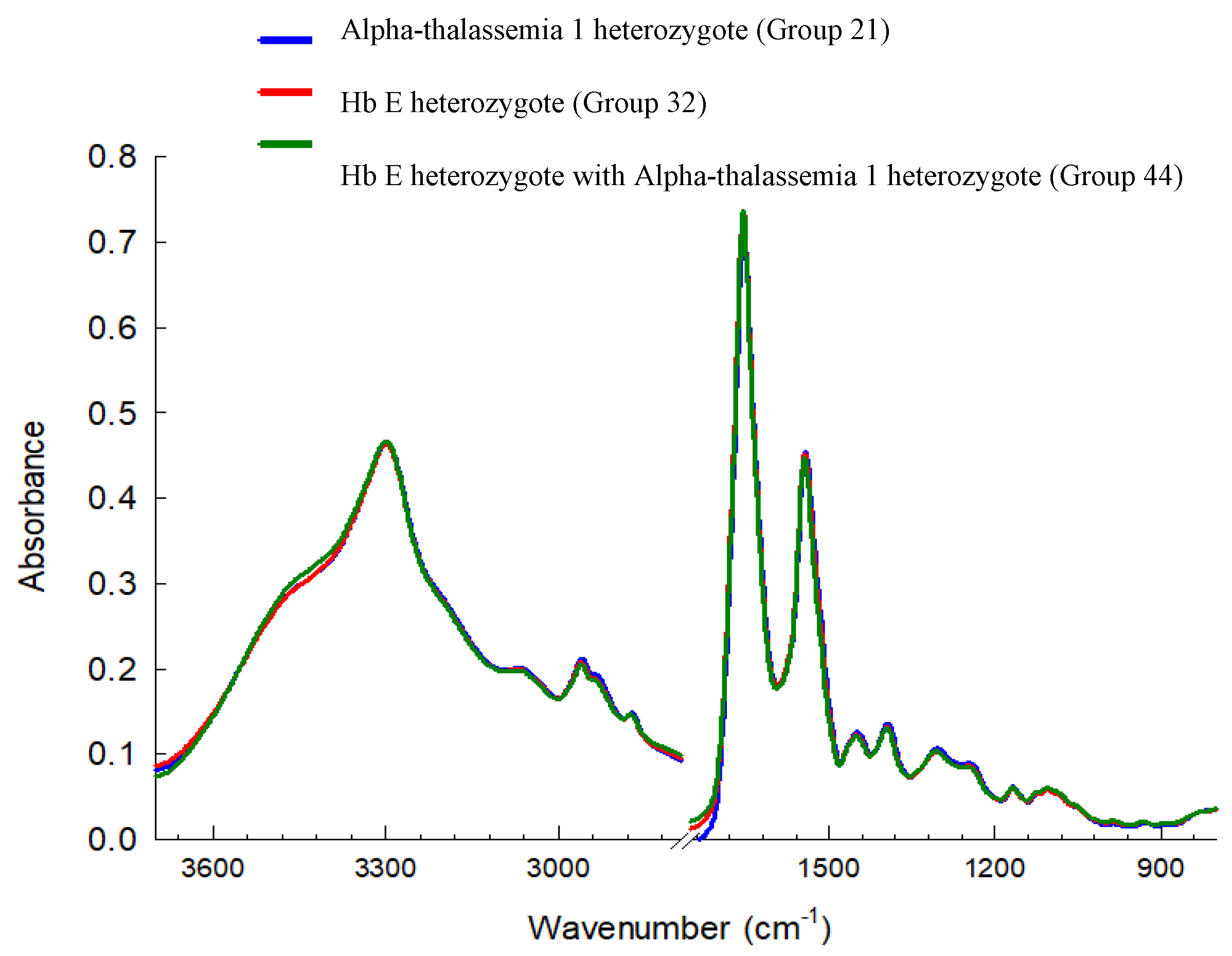

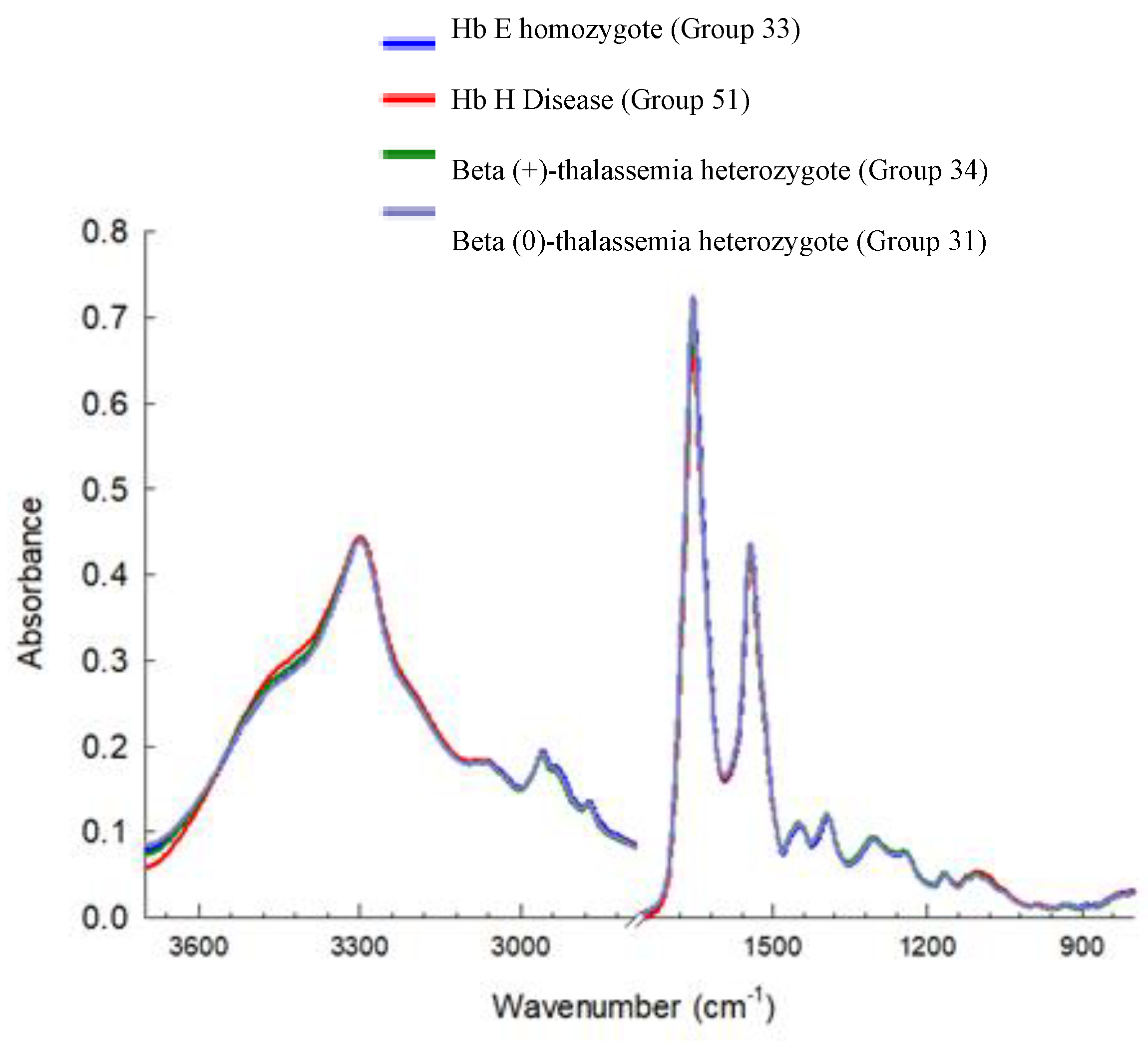

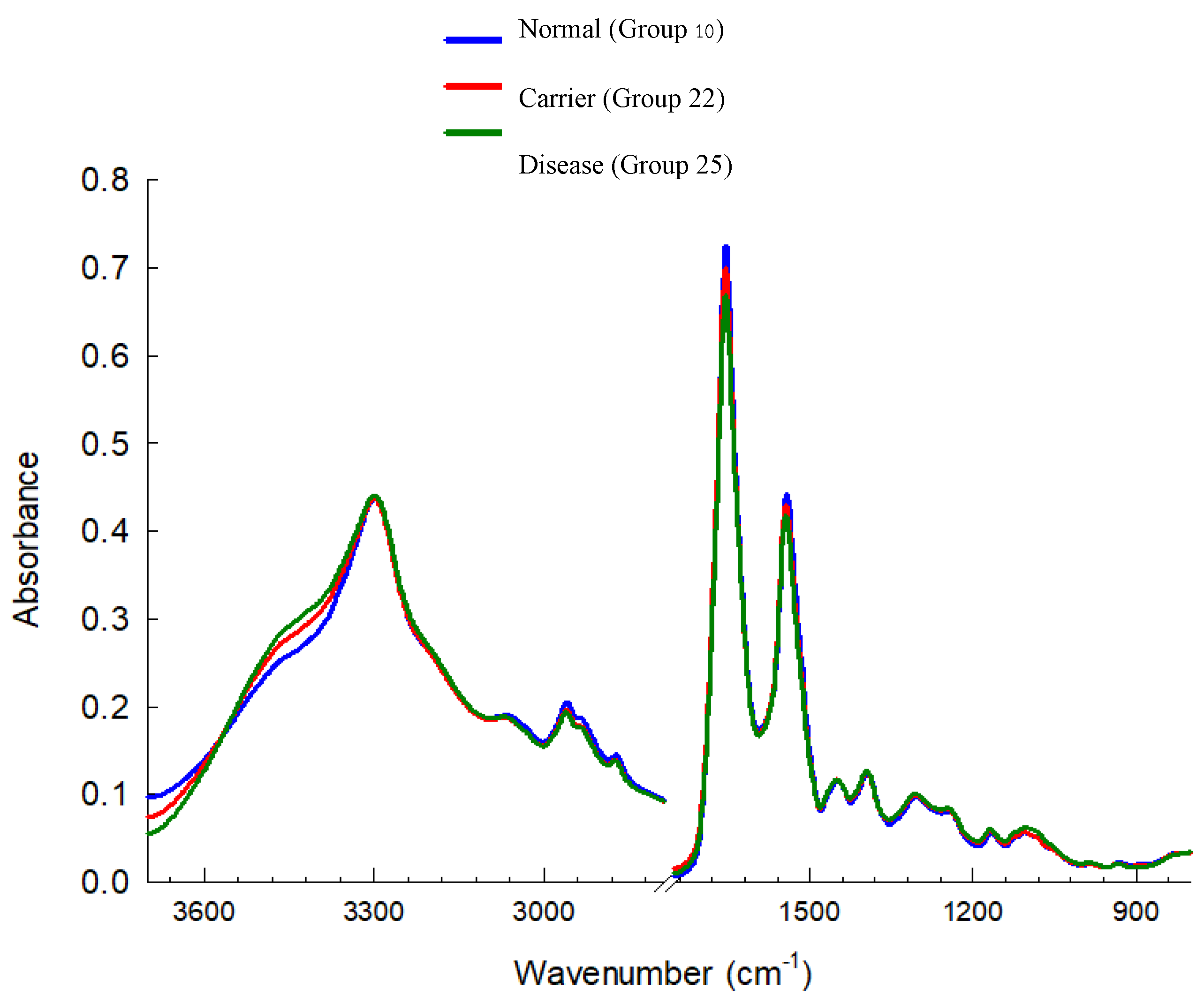

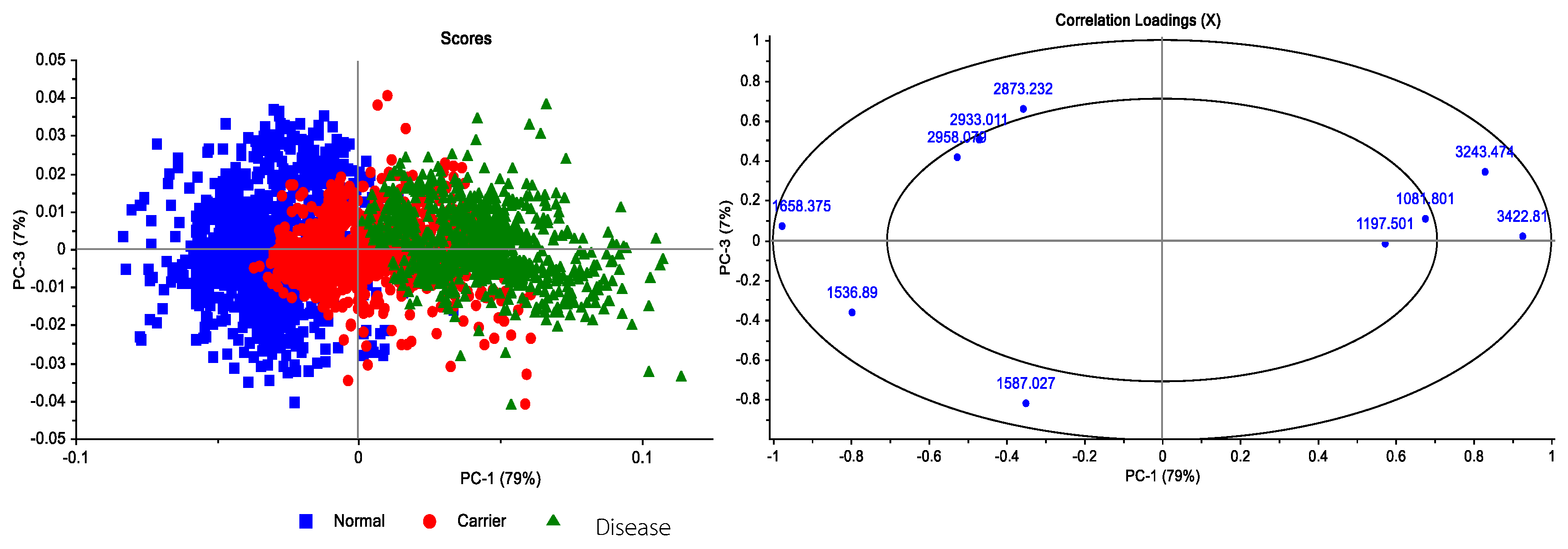

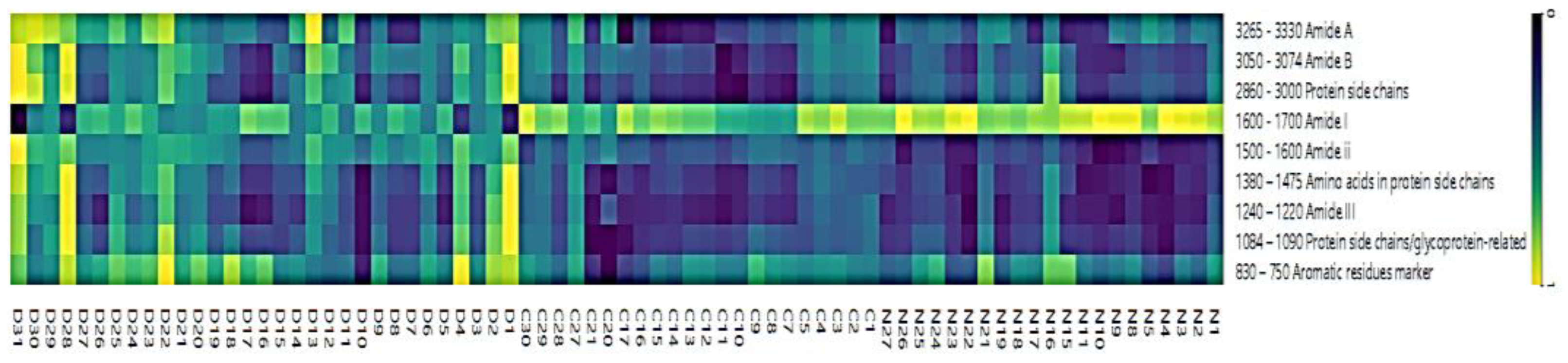

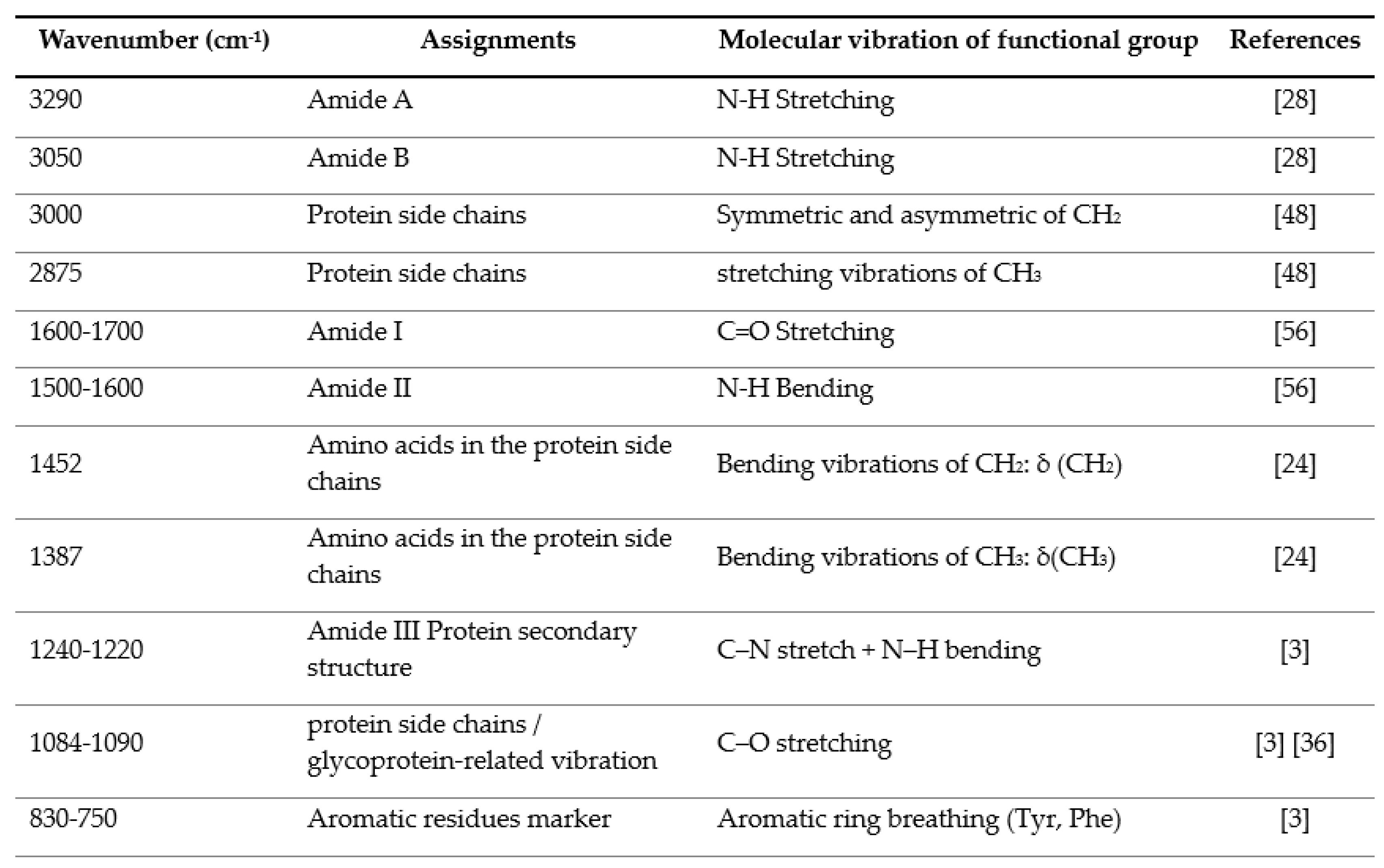

3.2. IR Microspectroscopy and Functional Group Analysis

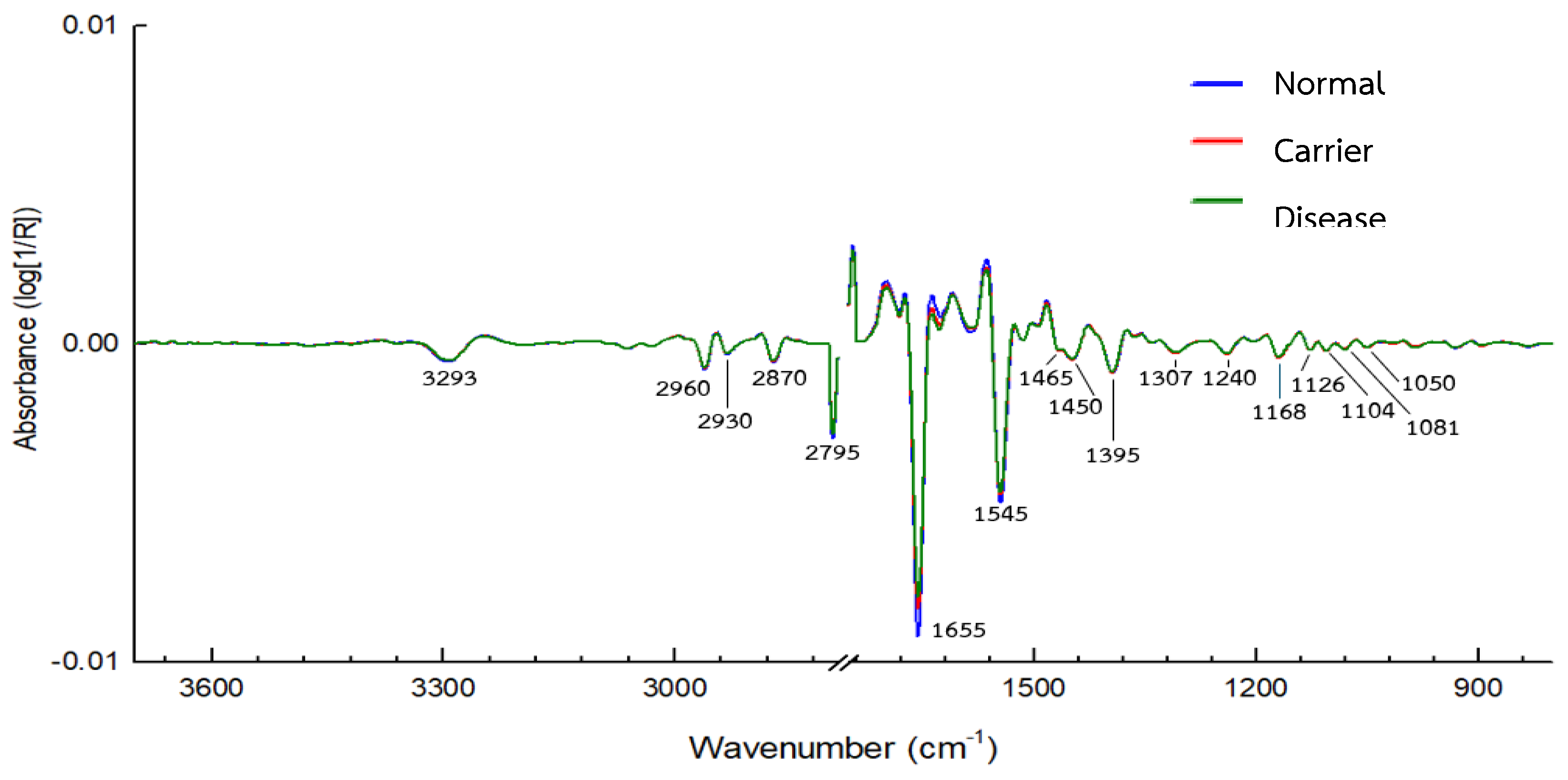

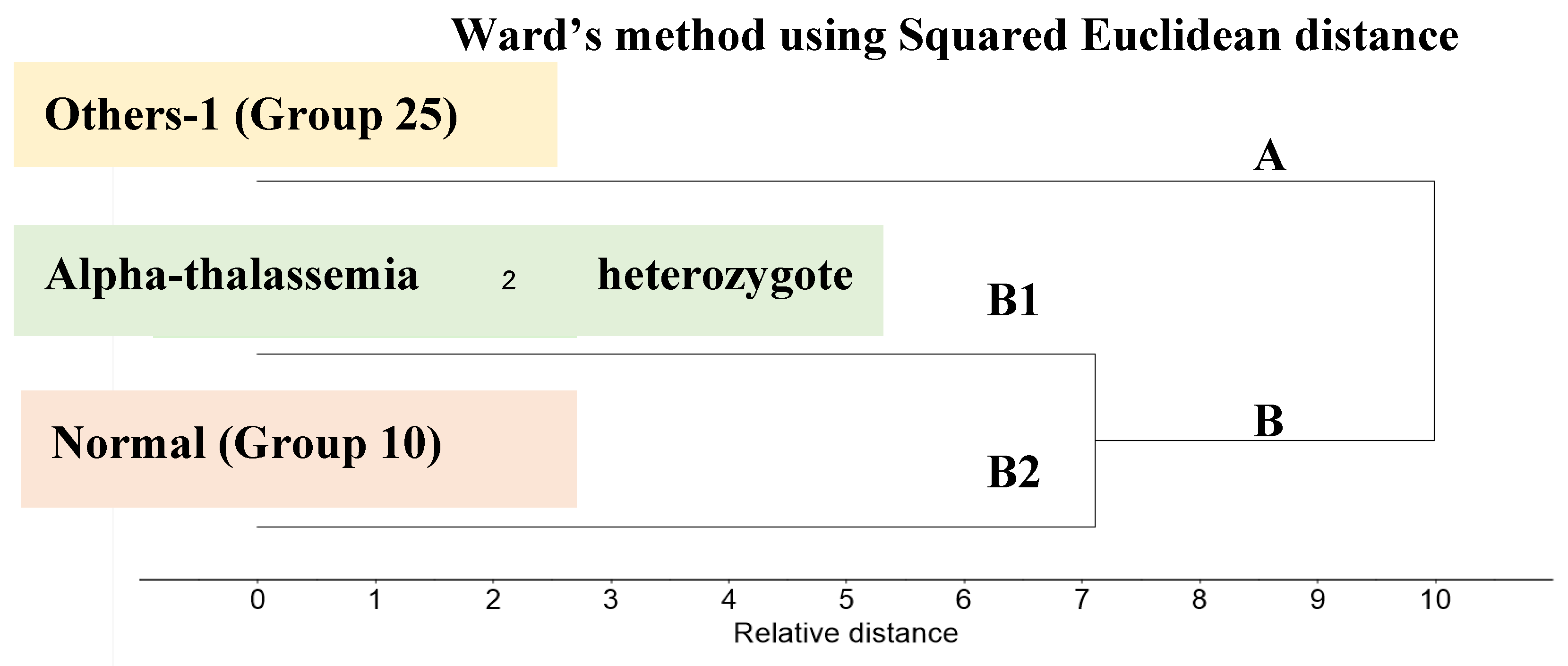

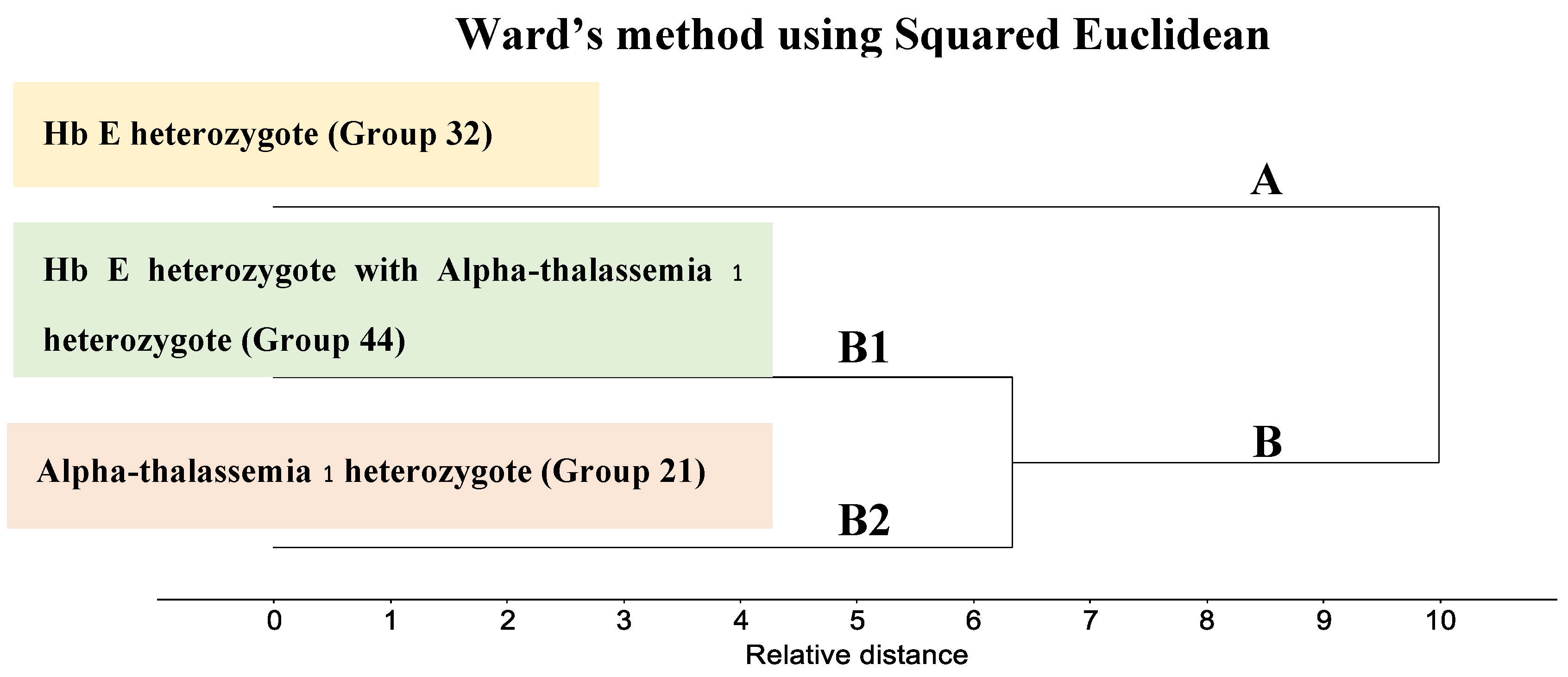

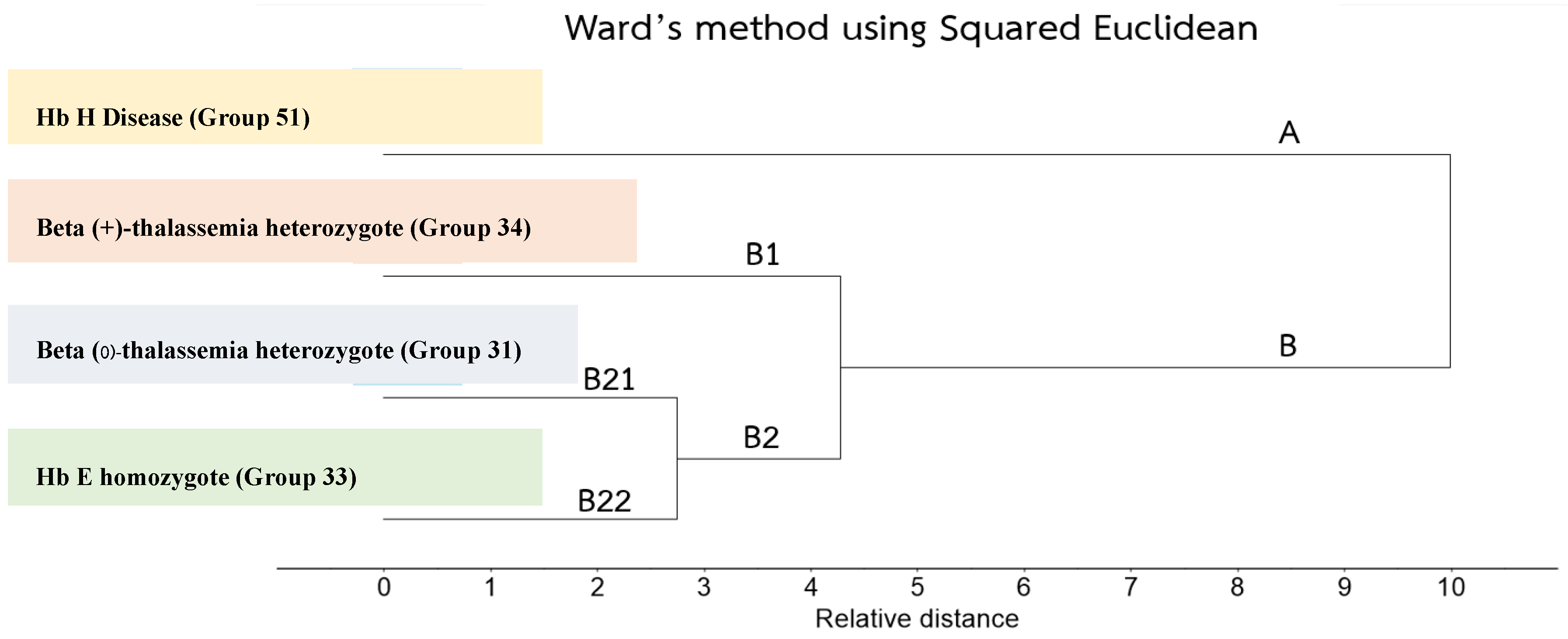

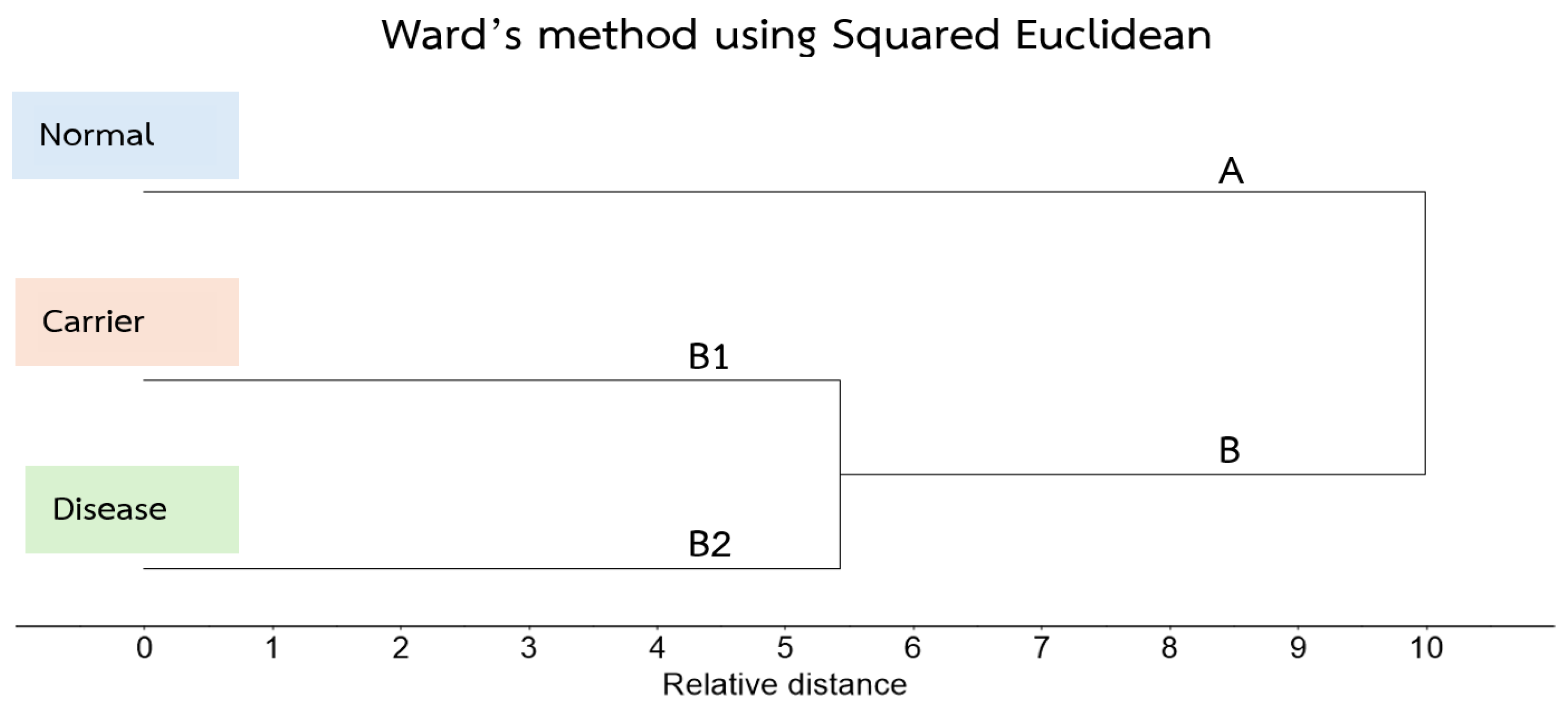

3.3. Cluster Analysis of FTIR Spectra of Hb Lysate

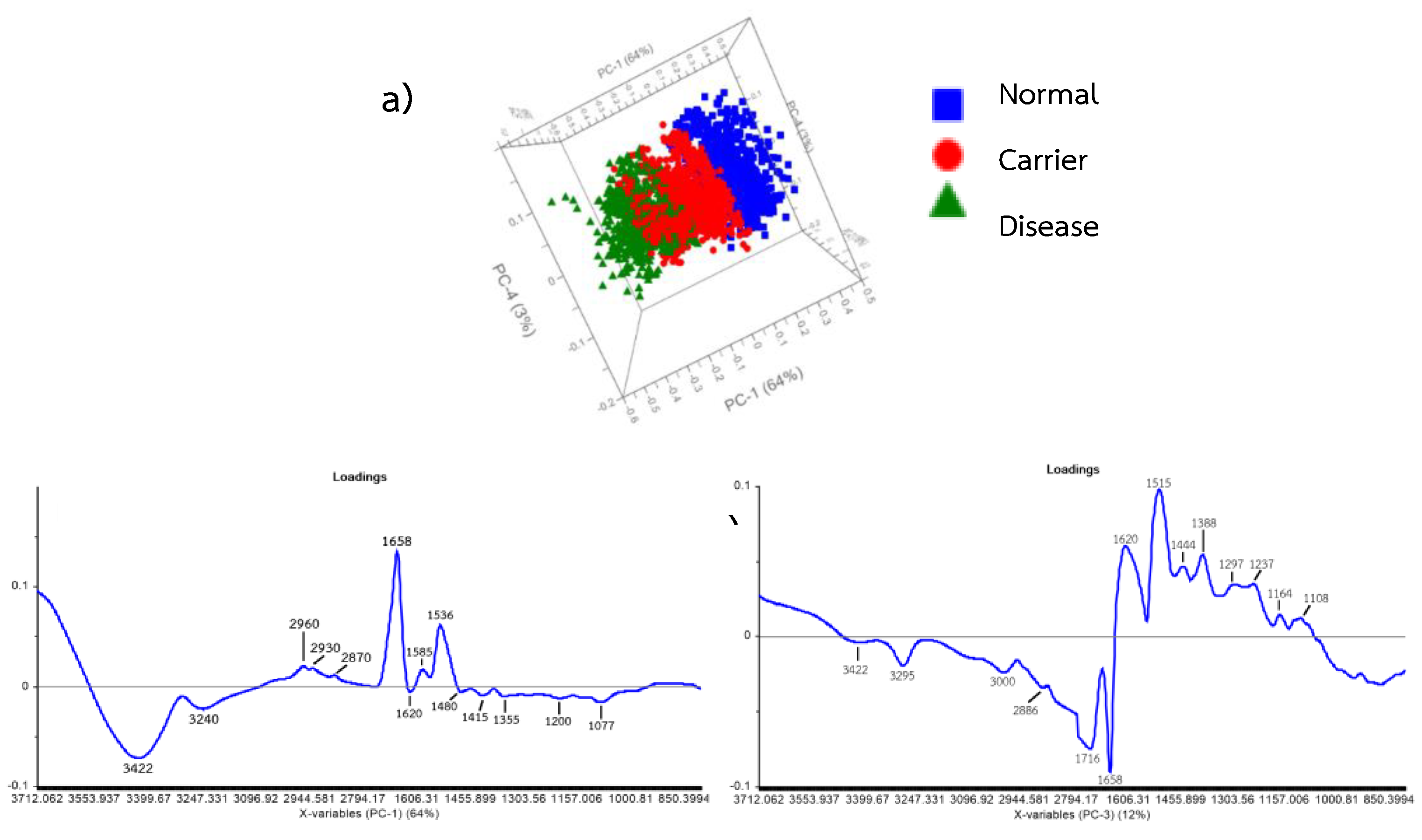

3.4. Principal Component Analysis (Scores and Loadings) of FTIR Spectra of Hb Lysate

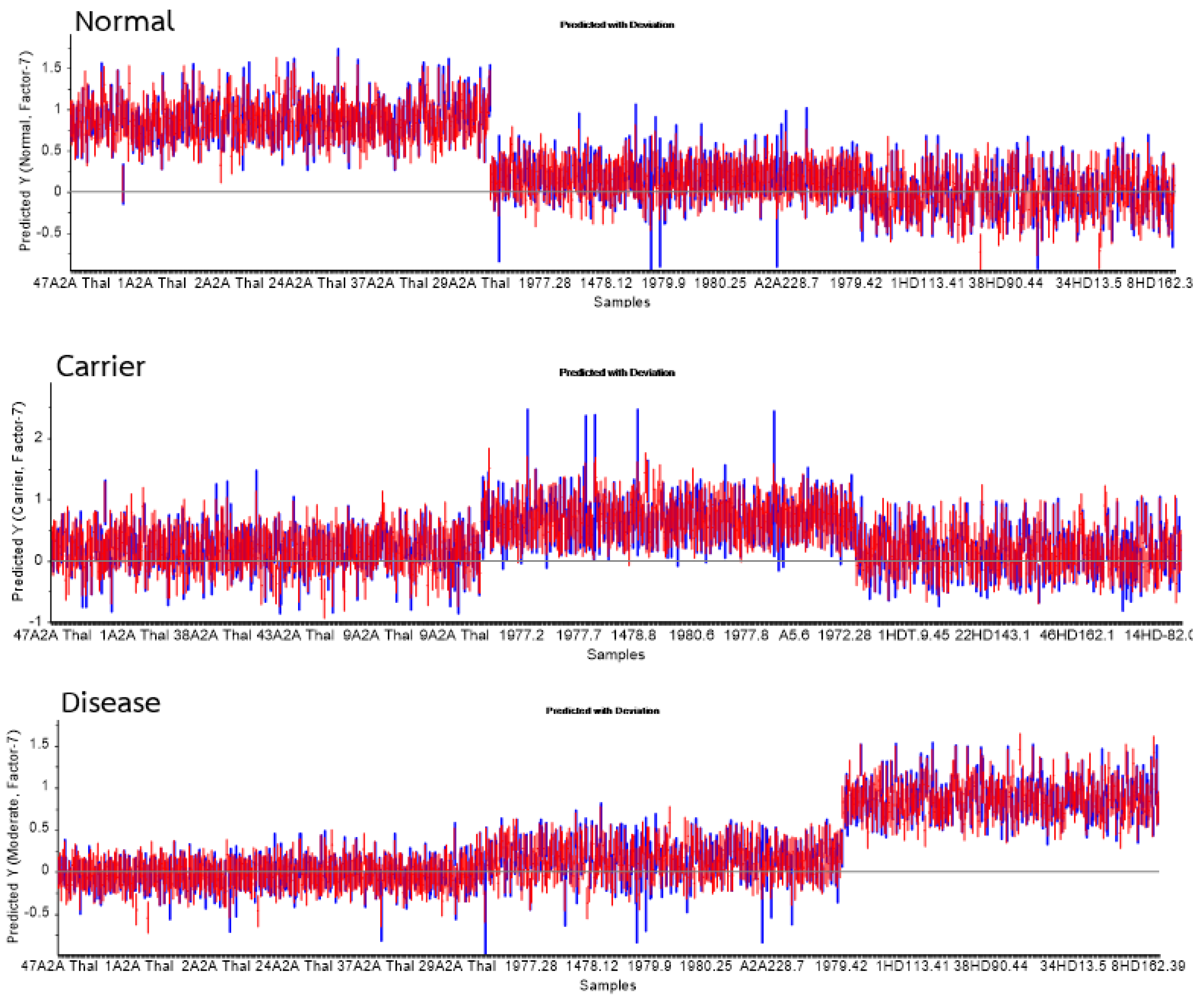

3.5. Correlation Loadings Analysis of PCA from FTIR Spectra of Hb Lysate

| Group | Statistics | No. Vigor | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | True positive | 378 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| False Positive | 6 | |||

| Carrier | True positive | 272 | 0.81 | 0.91 |

| False Positive | 62 | |||

| Disease | True positive | 287 | 0.99 | 1.00 |

| False Positive | 3 |

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aksoy, C.; Uckan, D.; Severcan, F. FTIR spectroscopic imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in beta thalassemia major disease state. Biomedical Spectroscopy and Imaging 2012, 1, 67–78.

- Bajwa, H.; Basit, H. Thalassemia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Bioenergetics 2007, 1767(9), 1073–1101.

- Berzal, F. Redes Neuronales & Deep Learning. 2018.

- Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Machine Learning 1996, 24, 123–140.

- Butler, H. J.; Cameron, J. M.; Jenkins, C. A.; Hithell, G.; Hume, S.; Hunt, N. T.; Baker, M. J. Shining a light on clinical spectroscopy: Translation of diagnostic IR, 2D-IR and Raman spectroscopy towards the clinic. Clinical Spectroscopy 2019, 1, 100003. [CrossRef]

- Chonat, S.; Quinn, C. T. Current standards of care and long-term outcomes for thalassemia and sickle cell disease. In: Malik, P.; Tisdale, J. (Eds.) Gene and Cell Therapies for Beta-Globinopathies. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 2017, 1013.

- Chukiatsiri, S.; Siriwong, S.; Thumanu, K. Pupae protein extracts exert anticancer effects by down-regulating IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α via biomolecular changes in human breast cancer cells. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 128, 110278.

- De Bruyne, S.; Speeckaert, M. M.; Delanghe, J. R. Applications of mid-infrared spectroscopy in the clinical laboratory setting. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 2017. [CrossRef]

- Derczynski, L. Complementarity, F-score, and NLP evaluation. In: Proceedings of LREC 2016 2016, 261–266.

- Devore, J. L. Probability and Statistics for Engineering and the Sciences. Cengage Learning: 2010.

- Dunkhunthod, B.; Chira-atthakit, B.; Chitsomboon, B.; Kiatsongchai, R.; Thumanu, K.; Musika, S.; Sittisart, P. Apoptotic induction of the water fraction of Pseuderanthemum palatiferum ethanol-extract powder in Jurkat cells monitored by FTIR microspectroscopy. ScienceAsia 2021. [CrossRef]

- Dybas, J.; Alcicek, F. C.; Wajda, A.; Kaczmarska, M.; Zimna, A.; Bulat, K.; Marzec, K. M. Trends in biomedical analysis of red blood cells—Raman spectroscopy versus other spectroscopic, microscopic and classical techniques. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2022, 146, 116481. [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Annals of Statistics 1979, 7(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Fadlelmoula, A.; Pinho, D.; Carvalho, V. H.; Catarino, S. O.; Minas, G. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to analyse human blood over the last 20 years: A review towards lab-on-a-chip devices. Micromachines (Basel) 2022, 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters 2006, 27(8), 861–874.

- Ferih, K.; Elsayed, B.; Elshoeibi, A. M.; Elsabagh, A. A.; Elhadary, M.; Soliman, A.; Abdalgayoom, M.; Yassin, M. Applications of artificial intelligence in thalassemia: A comprehensive review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1551. [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, D.; Rinaldi, C.; Baker, M. J. Is infrared spectroscopy ready for the clinic? Analytical Chemistry 2019, 91, 12117–12128. [CrossRef]

- Fucharoen, S.; Winichagoon, P. Haemoglobinopathies in Southeast Asia. Indian Journal of Medical Research 2011, 134(4), 498–506.

- Gareth, J.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning. Springer: 2013.

- Guo, S.; Wei, G.; Chen, W.; Lei, C.; Xu, C.; Guan, Y.; Liu, H. Fast and deep diagnosis using blood-based ATR-FTIR spectroscopy for digestive tract cancers. Biomolecules 2022, 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Harnsajarupant, P. Thalassemia. Jetanin Academic Journal 2023, 10(1). Available from: https://jetanin.com/th.

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning. Springer: 2013.

- Joyce, E. J.; Krimm, S.; Miller, W. G. Infrared spectra and assignments for the amide I band in polypeptides. Biopolymers 1993, 33(12), 1741–1752.

- Kaimuangpak, K.; Tamprasit, K.; Thumanu, K.; Weerapreeyakul, N. Extracellular vesicles derived from microgreens of Raphanus sativus L. var. caudatus Alef contain bioactive macromolecules and inhibit HCT116 cell proliferation. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 15686. [CrossRef]

- Kochan, K.; Bedolla, D. E.; Perez-Guaita, D.; Adegoke, J. A.; Veettil, T. C. P.; Martin, M.; Wood, B. R. Infrared spectroscopy of blood. Applied Spectroscopy 2020, 75(6), 611–646. [CrossRef]

- Kohavi, R. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. In: Proceedings of IJCAI 1995.

- Krimm, S.; Bandekar, J. Vibrational spectroscopy and conformation of peptides, polypeptides, and proteins. Advances in Protein Chemistry 1986, 38, 181–364. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-Z.; Tsang, K.; Li, C.; Shaw, A.; Mantsch, H. Infrared spectroscopic identification of beta-thalassemia. Clinical Chemistry 2003, 49, 1125–1132. [CrossRef]

- Lorthongpanich, C.; Thumanu, K.; Tangkiettrakul, K.; Jiamvoraphong, N.; Laowtammathron, C.; Damkham, N.; Upratya, Y.; Issaragrisil, S. YAP as a key regulator of adipo-osteogenic differentiation in human MSCs. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2019, 10, 402. [CrossRef]

- Luanpitpong, S.; Janan, M.; Thumanu, K.; Poohadsuan, J.; Rodboon, N.; Klaihmon, P.; Issaragrisil, S. Deciphering elevated lipid via CD36 in mantle cell lymphoma with bortezomib resistance using synchrotron-based FTIR spectroscopy of single cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 576. [CrossRef]

- MedlinePlus. Alpha thalassemia. [Online] 2023 [cited 2022 Dec 02]. Available from: https://3billion.io/blog/rare-disease-series-3-thalassemia/.

- Metz, C. E. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine 1978, 8(4), 283–298.

- Mistek-Morabito, E.; Lednev, I. K. FT-IR spectroscopy for identification of biological stains for forensic purposes. Spectroscopy (Santa Monica) 2018, 33, 8–19.

- Mostaço-Guidolin, L. B.; Bachmann, L. Application of FTIR spectroscopy for identification of blood and leukemia biomarkers: A review over the past 15 years. Applied Spectroscopy Reviews 2011, 46(5), 388–404. [CrossRef]

- Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I. U. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of biological tissues. Applied Spectroscopy Reviews 2008, 43(2), 134–179. [CrossRef]

- Peng, L. X.; Wang, G. W.; Yao, H. L.; Huang, S. S.; Wang, Y. B.; Tao, Z. H.; Li, Y. Q. [FTIR-HATR to identify beta-thalassemia and its mechanism study]. Guang Pu Xue Yu Guang Pu Fen Xi 2009, 29(5), 1232–1236.

- Powers, D. M. W. Evaluation: from precision, recall and F-factor to ROC, informedness, markedness & correlation. Journal of Machine Learning Technologies 2007, 2, 37–63.

- Raschka, S. Model evaluation, model selection, and algorithm selection in machine learning. arXiv preprint 2018.

- Remanan, S.; Rajeev, P.; Sukumaran, K.; Savithri, S. Robustness of FTIR-based ultrarapid COVID-19 diagnosis using PLS-DA. ACS Omega 2022, 7(50), 47357–47371.

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot for imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10(3).

- Sammut, C.; Webb, G. I. Encyclopedia of Machine Learning. 2010.

- Sanchaisuriya, K.; Fucharoen, G.; Sae-ung, N.; Sae-ue, N.; Baisungneon, R.; Jetsrisuparb, A.; Fucharoen, S. Molecular and hematological characterization of HbE heterozygote with alpha-thalassemia determinant. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 1997, 28 Suppl. 3, 100–103.

- Sasaki, Y. The Truth of the F-measure. School of Computer Science, University of Manchester: 2007.

- Srisongkram, T.; Weerapreeyakul, N.; Thumanu, K. Evaluation of melanoma (SK-MEL-2) cell growth between 3D and 2D cell cultures with FTIR microspectroscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 4141.

- Spoto, F.; Martimort, P.; Drusch, M. Selecting and interpreting measures of thematic classification accuracy. Remote Sensing of Environment 1997, 62(1), 77–89.

- Sukpong, S.; Thumanu, K.; Saovana, T.; Siriwong, S.; Changlek, S. Application of infrared spectroscopy for classification of thalassemia and hemoglobin E. Suranaree Journal of Science & Technology 2018, 25(2).

- Surewicz, W. K.; Mantsch, H. H.; Chapman, D. Determination of protein secondary structure by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: A critical assessment. Biochemistry 1993, 32(2), 389–394. [CrossRef]

- Tantiworawit, A.; et al. Hematologic parameters and thalassemia diagnosis in Northern Thailand. Hemoglobin 2019.

- Taylor, J. R. An Introduction to Error Analysis. University Science Books: 1997.

- Tharwat, A. Classification assessment methods. Applied Computing and Informatics 2018.

- Thongprasert, S.; et al. Hemoglobin typing and thalassemia carrier screening in Thai population. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 2012.

- Thumanu, K.; Sangrajrang, S.; Khuhaprema, T.; Kalalak, A.; Tanthanuch, W.; Pongpiachan, S.; Heraud, P. Diagnosis of liver cancer from blood sera using FTIR microspectroscopy: A preliminary study. Journal of Biophotonics 2014, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Thumanu, K.; Tanthanuch, W.; Ye, D.; Sangmalee, A.; Lorthongpanich, C.; Heraud, P.; Parnpai, R. Spectroscopic signature of mouse embryonic stem-cell–derived hepatocytes using synchrotron FTIR microspectroscopy. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2011, 16(5), 057005.

- Tian, F.; Rodtong, S.; Thumanu, K.; Hua, Y.; Roytrakul, S.; Yongsawatdigul, J. Molecular insights into antibacterial peptides derived from chicken plasma hydrolysates. Foods 2022, 11, 3564.

- Walton, D. S.; Baker, M. J.; Goodacre, R.; et al. Structural characterization of proteins and their assemblies using FTIR spectroscopy. Nature Protocols 2015, 10(1), 100–118.

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy in oral cancer diagnosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(3), 1206. [CrossRef]

- Wasi, P.; Pootrakul, S.; Pootrakul, P.; Pravatmuang, P.; Initiator, P.; Fucharoen, S. Thalassemia in Thailand. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1980, 344, 352–363. [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, D. J.; Clegg, J. B. The Thalassemia Syndromes, 4th ed.; Blackwell Science: 2001.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Control of Haemoglobin Disorders. Geneva: 2011.

- Xu, Y.; Goodacre, R. On splitting training and validation set: a comparative study of cross-validation, bootstrap and systematic sampling for estimating generalization. n.d. (Preprint/Technical Report). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).